ABSTRACT

Stakeholder participation in European Biosphere Reserves (BRs) has been extensively studied; however, the evolution of participation at different levels and the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have been less explored. A mixed-method approach was used to investigate this evolution, including a literature review, analysis of a European longitudinal survey conducted in 2008 and 2021, case study interviews and a questionnaire to Biosphere Reserve managers. Results indicate that stakeholder participation in BRs has become more important over time, with both an increase in the number and diversity of stakeholders involved at higher levels of participation. This increase was augmented by the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) during the pandemic. However, the increased use of ICTs had its challenges, such as the exclusion of certain types of stakeholders from the participatory process. Solutions, such as creating hybrid meeting arenas, are suggested to address these challenges. We conclude by providing recommendations for further enhancing our knowledge base on new forms of participation based on digital platforms.

1. Introduction

Developing approaches for the conservation of biodiversity has become an increasing focus in both research and policy (Raymond et al., Citation2022). A key instrument will be landscape-scale approaches to conservation that go beyond Protected Areas, accounting for human populations in sustainable ways. UNESCO Biosphere Reserves (BRs) are an example of such an approach, aiming to reconcile nature conservation with human activities by managing natural resources in a sustainable manner.

Increasing stakeholder participation in environmental governance initiatives can improve social-ecological resilience, enhance synergies between conservation, social and economic development, and increase project legitimacy and equitable outcomes (Biggs et al., Citation2012; Schultz et al., Citation2011). The legitimacy of a project is linked to the transparency of the participatory process and the fair inclusion of a diversity of knowledges and opinions from a diversity of stakeholders (Cash et al., Citation2002; Reed, Citation2008). This ‘multi-stakeholder approach’ has been previously used in environmental decision-making and has proven to enhance sustainability; improve learning processes; and prevent conflicts at different stages of a project (Schwilch et al., Citation2012; Thabrew et al., Citation2009). It can be defined as the process in which a diversity of stakeholders interacts to set a project’s objectives and jointly identify challenges and solutions (Hovardas, Citation2021). It can operationalized through platforms (so-called multi-stakeholder platforms; MSPs) where key stakeholders are represented in a ‘decision-making body’ to cooperate around environmental issues in a more inclusive manner for better legitimacy of decisions (Brenner, Citation2019; Warner, Citation2007).

However, navigating diverse stakeholders’ opinions can be challenging, particularly when local stakeholders are not represented in decision-making bodies (D’aquino Citation2002). Arnstein (Citation1969), whose breakthrough work advocated for broader and meaningful participation by community members in public planning processes, discussed that stakeholder participation was related to power distribution, from being informed and being heard to taking control of the decisional power. However, studies show that higher levels of participation are not always directly related to higher levels of legitimacy (Mohedano Roldán et al., Citation2019).

One of the key founding documents of UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, the Seville Strategy, encourages participation as a key aspect of their governance and management approach (UNESCO, Citation1996). Several UNESCO guidelines have since been created for stakeholder participation in BRs; where Bouamrane (Citation2006, Citation2007) gave examples of stakeholder dialogue aiming to reconcile biodiversity and people,. Multiple studies have focused on the implementation of stakeholder participation in BRs, as social-ecological systems for natural resource management and adaptive co-management (Baird et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Bouamrane et al., Citation2016; Plummer, Baird et al., Citation2017; Schultz et al., Citation2011; Schultz et al., Citation2018). In European BRs, participation takes different forms, from consultation of local communities about landscape quality objectives to a multi-stakeholder collaboration in governance (Schliep & Stoll-Kleemann, Citation2010; Sowińska-Świerkosz & Chmielewski, Citation2014). Some studies indicate that disseminating information may have a greater effect on legitimacy of BRs in local communities than other levels of participation (Mohedano Roldán et al., Citation2019).

The right to have access to information is promoted by the United Nations (UN) in SDG 16, target 10 (UN General Assembly, Citation2015); ‘promotes … inclusive societies for sustainable development’, and this underlines that information is important for inclusivity. Digital technologies such as internet and diverse online tools (OTs) are increasingly used to get access to information. The 2030 Agenda (UN General Assembly, Citation2015), recognizes that information and communication technologies (ICTs) can enhance sustainable development through ‘global interconnectedness’ leading to a ‘great potential to accelerate human progress, to bridge the digital divide and to develop knowledge societies’ (ITU, Citation2017). In Europe, many people use ICTs to disseminate information, learn and communicate (Redecker et al., Citation2010). More recently, ICTs have shown their important use when the Covid-19 pandemic started in 2020, particularly in the healthcare sector (Vargo et al., Citation2021). In conservation work, studies of pandemic impacts have been more focused on the public’s increased interest in protected areas (Guedes-Santos et al., Citation2021; Souza et al., Citation2021). In the past, the use of ICTs in governance has been proven to be important for participation at the information level (Cullen-Knox et al., Citation2017). However the legitimacy of ICTs in deliberative participation for environmental assessments has been questioned (Sinclair et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, conservation organizations, use digital tools to communicate and engage stakeholders (Arts et al., Citation2015). However, the impacts and shifts in the use of ICTs during and after the pandemic is still under-studied.

We aim to investigate the diversity of stakeholders groups at different levels of participation by asking (1) if there is an evolution in how European BRs are implementing stakeholder participation, as recommended in the MAB strategic actions, through a literature review, a longitudinal survey and case-based studies, (2) how participation has been affected during the Covid pandemic, and (3) how this can help us learn more about the use of ICTs for spread of information and dialogue with stakeholders.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Methodological approach and data collection

We used a mixed-methods approach combining quantitative and qualitative methods, following Bazeley (Citation2018), to track the evolution of stakeholder participation in BRs over time. Our study focused on the European part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves under UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Program. We used the following methods: (1) a literature review of the four MAB action plans since the start of the program in 1971 to understand how the importance of stakeholder participation has evolved over time; (2) three European BR case studies for understanding changes in stakeholder participation; (3) a European longitudinal survey; 2008 and 2021, targeting BR managers in order to observe if a change in stakeholder participation has happened over time at different levels of participation; and (4) a follow-up questionnaire to understand how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected stakeholder participation and to grasp how ICTs were viewed by BR managers as tools to tackle the challenges caused by the pandemic.

The three case studies were located in France, Germany and Norway (Supplementary A). To observe a change of strategies in how stakeholder participation is valued in BRs, we chose BRs according to the year of their designation. The oldest was the Vosges du Nord-Pfälzerwald Transboundary BR (VDN-P TBR) located in France and Germany, designated in 1998. The second was Nordhordland BR (NHBR) in Norway designated in 2019. The third was the Moselle Sud BR (MSBR) in France, which was not yet designated at the time of the study in June 2021. We conducted seven semi-structured interviews between April and June 2021 in the three BRs, each interview lasting between one and two hours. We targeted two different categories of stakeholders: BR managers and project leaders. We define Biosphere Reserve manager as ‘main contact person for the Biosphere Reserve, coordinator, communicates with different stakeholders in the BR and manages the territory as a common project with common goals’ (Bioret, Citation2001), and Project leader as ‘professional responsible for a project and who manages a project’. In Biosphere Reserves, leaders are supposed to ‘monitor the groups to ensure that everyone is participating and that the challenges (of the project) have been fully grasped’ (Bouamrane, Citation2006). The interviews questions focused on stakeholder participation in different activities of the BR over time (Supplementary B). Due to the pandemic causing difficulties of traveling, most of the interviews were conducted on-line using the digital tool Zoom.

For the European longitudinal survey of participation in European BRs, we conducted a longitudinal analysis based on surveys in 32 European Biosphere Reserves, representing 13 different countries (Supplementary C). The surveys were conducted in 2008, 2013 (Mohedano Roldán et al., Citation2019; Schultz et al., Citation2011) and 2021 as part of a larger study on management effectiveness in BRs. In this study, we focused on the part of the surveys related to stakeholder participation We only used data from the 2008 and 2021 surveys as this part of the survey from 2013 was not comparable with 2008 and 2021. BR managers were asked to choose which groups of stakeholders (six categories) they thought were involved in different activities in their BRs (, below).

Table 1. Oversight over stakeholder categories and activities surveyed in the longitudinal study.

To investigate the effects of the pandemic on modes of stakeholder participation, especially information flow and how OTs were used, we supplemented the European longitudinal survey with additional interview questions; a follow-up questionnaire. We asked four open-ended questions related to the impact of the pandemic on stakeholder participation and the use of ICTs in a questionnaire targeting BR managers (Supplementary D). Out of the 32 BR managers contacted, 22 responded (69% response rate), through phone calls and a Google form in December 2021.

2.2. Data processing and analysis

We performed the analysis of the European longitudinal survey using the software program Rstudio (R version 4.0.3, 2020). First, we calculated a mean of total participation and standard error of the mean in 2008 and 2021 for the eight activities, by summing up all the different stakeholder categories and applying the mean function on the total of participation for each year (). Then, we classified these activities into three levels of participation: decision-making, implementation, and information. Questions measuring the different levels of participation were added up () and a mean sum calculated for each level of participation per year. Finally, we calculated the diversity indexes, Simpson and Shannon, for the diversity of stakeholders in 2008 and 2021 across all eight activities, using the diversity function in RStudio for the total of participation of the years 2008 and 2021. We performed a linear model or a Kruskal–Wallis test to observe if there was a significant difference between 2008 and 2021 for each studied level of participation. The choice of the test was done after testing their distributions. We considered data distributions normal or not after running a Shapiro test. We applied a linear model test when data had a normal distribution. When not normal, a Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

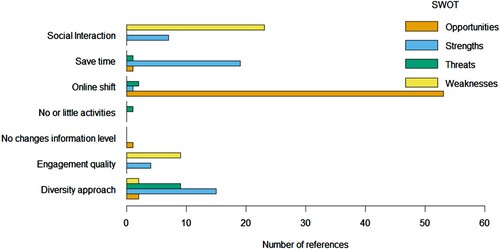

We analyzed all collected text-based data using coding in the software NVivo (12). For the three case studies, we transcribed the seven interviews before coding. We transcribed each interview and questionnaire a number to keep anonymity of respondents. For the follow-up questionnaire, some of the themes resulting from coding were categorized following the SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) method. The SWOT analysis is usually used for strategic planning by pointing out internal and external factors to guide the success of a project (Dealtry, Citation1992). Here we used this tool to underpin the challenges and benefits of ICTs for stakeholder participation in BRs. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Norwegian Center for Research Data (NSD). All audio files will be deleted by the end of the project period. Interviewees and informants gave informed consent before interviews or questionnaires were started.

3. Results

3.1. The evolution of stakeholder participation as expressed in the MAB strategic documents

The inaugural international congress of BRs held in Minsk, 1983, saw the creation of the first-ever Action Plan for Biosphere Reserves. The three main targets expressed the need to ‘improve and expand the network’, ‘develop knowledge for conserving ecosystems and biodiversity’, and ‘make Biosphere Reserves more effective in linking conservation and development’. Local participation was also discussed (objective 7) (UNESCO, Citation1984). However, the main objectives of the action plan were still very much focused on conservation, research and development of the network. The success of sustainable development in the management of protected areas was discussed in the Seville Strategic Document of 1995 (UNESCO, Citation1996). Here, there was mention of new methods to involve stakeholders not only in consultation processes but also in management planning and decision-making. The term ‘co-operation’ was even cited (UNESCO, Citation1996). In the Madrid Action Plan of 2008, UNESCO reiterated the importance of stakeholder participation in the management of ecosystems. There, stakeholders hold a role in planning an agenda for the management of the BRs (Target 20, UNESCO, Citation2008). The role of civil society was particularly mentioned at this phase of participation. The most recent action plan, the Lima Action Plan of 2015, repeated the same aspects. Participatory processes were addressed several times, especially in some strategic action areas of the action plan (A, B, E, UNESCO, Citation2017). The ‘transdisciplinary nature’ of the program was also detailed (E2.1, UNESCO, Citation2017). The details of this action entailed the need of a representative governance for BRs that would be ‘ensuring participation’.

3.2. Stakeholder participation as experienced in three Biosphere Reserve case studies

An evolution of stakeholder participation was observed at different stages of activities in the case studies (, at the end of Section 3.2). The way stakeholders were involved in each activity strongly depended on the context and governance structure of the BR. The more recently designated BRs used more multi-stakeholder collaboration than the older for the designation process. However, we noticed a trend towards a will to involve a wider range of stakeholders across case studies, even though politicians still played a major role in decision committees: ‘a participation in the governance is done through representatives’ [BR manager]; ‘you have to have decision from the politicians so you can do it [the project]’ [Project leader]. The most notable indication of increasing multi-stakeholder engagement was at the project level as both project leaders and BR managers acknowledged the importance of including a diversity of actors in BR projects ().

Table 2 . Stakeholder participation in the different activities of the three case studies.

3.3. Stakeholder participation in the European longitudinal survey

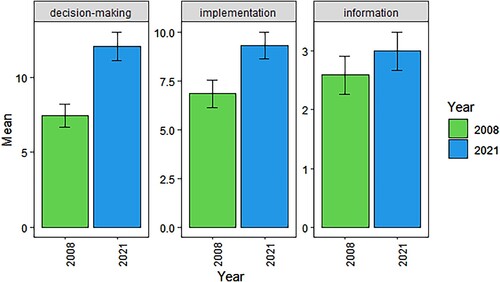

There was a significant increase of mean participation (p < 0.01) between 2008 and 2021 across the eight different activities for 32 European BRs as selected by the BR managers. There was also a significant increase in mean participation when analysing levels of participation separately (). A significant increase of mean participation between 2008 and 2021 was observed at the decision-making (Linear model test, p-value: 0,0003481) and implementation (Linear model test, p-value: 0,01083-06) levels. The mean participation seems to have evolved with a higher mean in 2021 than 2008, meaning more stakeholders participating in decision-making and implementation activities in 2021. However, the information level did not show a significant increase of mean participation between 2008 and 2021 (Kruskal Wallis test, p-value: 0,3824) (, below and Supplementary E).

Figure 1. Barplot of the mean of participation for different levels of participation in 2008 and 2021 of 32 European Biosphere Reserves as selected by Biosphere Reserve managers (significant results for the p-value: p < 0.05).

The analysis of changes in participant stakeholder diversity showed that both the Simpson and Shannon index were significantly higher in 2021 than in 2008 (Kruskal Wallis test for Simpson, p-value:0,003465; Kruskal Wallis test for Shannon, p-value: 0,0007989), demonstrating a higher diversity of stakeholders involved in the eight activities in 2021. Both the Simpson and Shannon index have high values for both years, which show a high representativeness of categories among stakeholders and a diversity and richness of stakeholders for the selected categories.

3.4. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on stakeholder participation in Biosphere Reserve activities

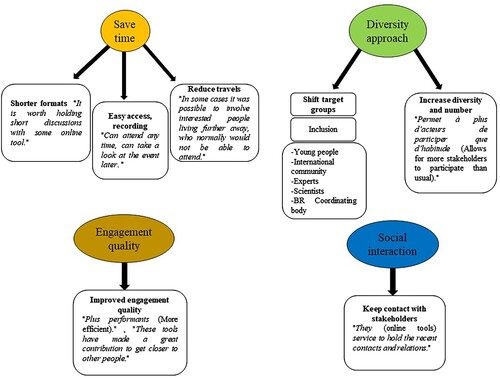

Results from the SWOT analysis helped us identify two main themes related to the impact of the pandemic on participation: Stakeholder participation via online tools and Changes. The second level nodes of Stakeholder participation via online tools were Social interaction, Save time, Diversity approach and Engagement quality (). The second level nodes of Changes were Digital shift, understood as a change towards the increasing use of digital communication channels, and no or little activities and no changes at information level (, below).

Figure 2. Coding references counts of the seven main themes identified and categorized following the SWOT analysis related to the use of ICTs during the pandemic in the 22 European Biosphere Reserves.

3.4.1. Strengths

Stakeholder participation via online tools was the main theme with identified strengths. In the topic Save time, BR managers found OTs were time saving due to their typically shorter time frames, easy access, recording possibilities, and reducing the need for traveling (). This was particularly true for participation to international events and relates to the Diversity approach. Globally, BR managers noticed an increase of the diversity and particularly the number of participants when using OTs. In particular, five groups of stakeholders were mentioned to engage with OTs (), to keep contact despite social distancing during the pandemic. This was developed in Social interaction, where ICTs were seen as essential to pursue collaboration with stakeholders (). Finally, ICTs were identified for their reliability to increase the Engagement quality in some cases, making meetings more efficient (, below).

3.4.2. Weaknesses

Weaknesses were identified under the theme Stakeholder participation via online tools. The first was Social interaction. BR managers deplored the lack of ‘human contact’ and social arenas provided by in-person meetings. Moreover, cooperation and networking with partners seemed to be negatively affected when using ICTs. They also found it difficult to reach agreements with stakeholders as in-person meetings appeared to be important for building ‘good relations’ with stakeholders. Engagement quality was also an identified weakness. BR managers perceived a lack of attention and engagement from stakeholders through online events. Furthermore, deliberation outcomes were considered impoverished by the lack of informal communication occurring during in-person meetings. This was particularly important for the Diversity approach, as ‘large (online) meetings do not allow the exhaustive participation of all members’, one BR manager mentioned. Therefore, in some cases, the number of participants did not increase when using OTs.

3.4.3. Opportunities

Changes was the other main theme identified. In some cases, the pandemic did not affect the way BRs informed stakeholders. Indeed, 7 out of the 22 BR managers said that no changes at the information level were applied during the pandemic. BRs used the same tools as before the pandemic to inform stakeholders (e.g. newsletter, magazine, homepage, E-mails, social media). However, the remaining 15 BR managers reported a Digital shift for communication, related to an increasing number of OTs used in BRs during the pandemic (Supplementary F). This increase gives the opportunity to communicate via different sources with stakeholders. An improvement in the utilization of these tools by BR staff during the pandemic was also observed. Potential for stakeholder training on how to use ICTs was therefore brought up. Finally, new methods such as the hybrid method, the possibility to attend online or in-person, was suggested as a new approach for BRs to engage with stakeholders. In this context, ICTs were seen as a ‘very good supplementary instrument’ to in-person meetings, as it introduced an element of choice.

3.4.4. Threats

The first threat identified was the Diversity approach linked to the theme Stakeholder participation via online tools. The use of OTs to communicate may exclude some stakeholders as not everyone wants to raise their voice in an online setting or possess the skills and resources to use ICTs. More specifically, it seemed that some groups of stakeholders such as older people and farmers were harder to engage with online platforms. No or little activities in Changes was the other threat related to the consequences of the pandemic on participation in BRs as interactions with stakeholders during the pandemic were limited.

4. Discussion

4.1. An evolution towards a diversity approach at different levels of Biosphere Reserve activities

4.1.1. Decision-making in governance and in project execution

The evolution of stakeholder participation in the MAB program strategic documents shows an intention towards a wider participation at higher levels. The multi-stakeholder approach is known to be an efficient method to improve knowledge in governance processes (Tengö et al., Citation2014). Participation in governance enables empowerment and greater responsibility towards stakeholders (Leitch et al., Citation2015). Using a multi-stakeholder approach for participation is also recognized as crucial for positive perception of environmental outcomes by stakeholders, especially when they can engage in activities and learn from them (Plummer, Dzyundzyak et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the MAB guidelines advise to include a wide range of stakeholders in the governance of BRs to improve knowledge sharing and common management of BRs.

Our results showed that European BR managers surveyed are aware of benefits in including a diversity of stakeholders, and tend to involve, on average, a higher diversity of stakeholders in planning the objectives for the BRs and in the steering and management committees in 2021 than in 2008. The survey also showed that more stakeholders participate in decision-making in 2021 than in 2008, demonstrating a will to increase participation. Moreover, we noticed new categories of key stakeholders involved in the governance of BRs in one of our case studies, with an increase of young stakeholders participation, as reported in other research (Donnellan-Barraclough et al., Citation2021).

Case studies showed that stakeholder participation in different activities of BRs is dependent on the inner context of BRs and their institutional organization. This differs between nations, political culture, socio-economic development, and agreements between stakeholders about the strategies set for the BRs (Schliep & Stoll-Kleemann, Citation2010). Nevertheless, a study on BR institutional governance showed that it is possible to find cases of both participation by experts who ensure BR goals are met and also a diversity of stakeholders who advise on decisions (George & Reed, Citation2016). Our work showed a clear intention from BRs to create platforms for discussion with a wide range of stakeholders in decision-making and evaluation of BRs objectives. Periodic reviews of BRs are a good way to evaluate success of these objectives (Van Cuong et al., Citation2017). Since stakeholders can have different visions of what success is, meetings to prepare for the periodic review are important to reach a consensus (Barclay & Osei-Bryson, Citation2010). Our results showed that these meetings are also important to remind a diversity of stakeholders what BR objectives were when being set and reminding them why BRs exist.

In specific BR projects, participation, when related to decision-making, enables better quality of decisions, taking a diversity of variables into account (Reed, Citation2008). In our research, the multi-stakeholder approach was also used when designing projects, as demonstrated both in the case studies and in the global survey. This aligns with findings in the study of Stoll-Kleemann et al. (Citation2010), where BR managers noted a will of the local communities to be more included in BR design and management.

4.1.2. Implementation and information

We showed an increase in involvement of the local community in BRs’ management over time (from 2008 to 2021). Other researchers have shown that the legitimacy of BRs in local communities is more related to practice-based participation and information than to representation in governance (Mohedano Roldán et al., Citation2019). However, the longitudinal survey did not show a significant increase of participation at the information level in European BRs included in this study. This aligns with results from the follow-up questionnaire where some BR managers did not observe changes in the way BR staff inform stakeholders about events of the BR. Nonetheless, it is important to note the limitation of the survey analysis, where the same categories of stakeholders were studied between 2008 and 2021. Therefore, there might be some changes targeting stakeholders that were not in the list of the survey in 2008, although it is difficult to know which ones.

4.2. The digital shift and participation via information and communication tools

We observed a digital shift catalyzed by the pandemic, with an increased use of ICT media to communicate with stakeholders in European BRs. The use of ICTs has also been rising in the environmental conservation and sustainability fields for various purposes such as workshops, group model building (Wilkerson et al., Citation2020), biodiversity monitoring (Dwivedi, Citation2021), economic developments (e-markets) (Måren et al., Citation2022) and education (Mammadova et al., Citation2022) around the world.

These new online possibilities shaped BRs’ stakeholder participation in many ways during the pandemic. First, it led to a change in the stakeholder groups participating in BR’s life from before the pandemic to during the pandemic. Consequently, a greater number and diversity of stakeholders were observed participating in BRs meetings with the use of ICTs. Therefore, ICTs can create possibilities to extend inclusiveness, as Pantić et al. (Citation2021) mentioned in their study on public participation in urban planning during the pandemic. Furthermore, digital tools were praised for the role they played for global sustainability as virtual conferences allow for carbon footprint reduction (Fraser et al., Citation2017). In our study, BR managers also discussed the benefits of reducing travels inside the BR as it allowed for participation of stakeholders who would usually not have the time to travel to organized meetings. Moreover, stakeholders who were unable to participate in an event could still be informed by watching the recording later. Therefore, despite no increase of mean participation at the information level between 2008 and 2021, overall it appears that the sources used to inform stakeholders have increased. Finally, in the context of a pandemic, these tools were useful to keep contact with stakeholders. It was particularly important to maintain relationships for mental health, and to facilitate remote collaboration in order to pursue running projects or design new strategies (Ospina & Heeks, Citation2011; Yang et al., Citation2020).

However, we should not expect ICTs to wholly replace in-person meetings. Indeed, while social interactions were preserved during the pandemic, in most cases thanks to the use of ICTs, they were also impoverished by it. First, moving life to a virtual space can also have unwanted consequences on mental health (Richter et al., Citation2021). For instance, frequent users of social media such as young people still felt the repercussions of being isolated during the pandemic (Bonsaksen et al., Citation2021). Our results showed that stakeholders in BRs longed for human contact. BR managers also expressed concern over the lack of informal discussions often happening during meeting breaks, which can give more opportunities to stakeholders who did not express their opinions during the meetings. We showed that online meetings can be efficient as they can sometimes cut ‘side discussions’. However, informal discussions are necessary to create a sense of community in the participatory process and, by doing so, a stronger network (Moss et al., Citation2021). Informal discussions might also foster the attention span that is affected by long online meetings, impacting the level of engagement amongst stakeholders.

Finally, this study points out the enhanced risk of exclusion of some stakeholders by the use of ICTs. In their paper, Moss et al. (Citation2021) mention four key themes related to collaboration in virtual setting future: accessibility, inclusivity, sustainability, and technology. Here, we acknowledge that these themes are connected. Our work showed that accessibility and technology were barriers to the inclusion of some age groups and stakeholders living in rural areas, due to lack of resources, access or skills. Older adults are often excluded in a virtual setting for the reasons cited above, which can lead to an intergenerational gap and reduce social interactions (Taipale et al., Citation2018). As for the rural areas, limited internet connectivity and services are often obstacles to the inclusion of stakeholders in an online event (Lai & Widmar, Citation2021). From a sustainable development perspective, these barriers can prevent stakeholders from accessing social and economic opportunities generated by the use of ICTs (Esteban-Navarro et al., Citation2020). In addition to being a challenge between different social groups inside countries, this digital divide is also present between BRs in Europe. Indeed, the lack of skills, resources and connectivity were described by some BR managers, leading to no interaction with stakeholders during lockdowns, while other BRs managed to keep contact via the use of ICTs.

4.3. Potential methods to bridge the digital divide in Biosphere Reserves

The digital divide within and across BRs is problematic for the diversity approach at all levels of participation. Therefore, solutions have been discussed in the literature and by BR managers to bridge this divide. Digital trainings were seen as an option to educate stakeholders on the use of ICTs. In the case of older adults, younger people could teach them to use ICTs, which might close the intergenerational gap and enhance solidarity in BRs. Social connections might motivate stakeholders who are reluctant to receive training (Esteban-Navarro et al., Citation2020; Taipale et a., Citation2018). Enabling digital inclusion also raises the need to implement local policies to improve digital access for everyone (Esteban-Navarro et al., Citation2020; Lopez-Ercilla et al., Citation2021). The final point raised by BR managers to bridge this divide was the use of hybrid events for stakeholder participation. Virtual services are seen as a good model to supplement in-person meetings while ‘reducing economic, social, and environmental barriers’ (Fraser et al., Citation2017; Raby & Madden, Citation2021). However, Kangas and Store (Citation2003) alerted on their uses, stating that they should not ‘replace’ direct participation but only complement it. Hybrid methods have the potential to include a large diversity and number of stakeholders. Nevertheless, even this model has its challenges. Organizing such events requires tremendous effort and adds complexity to the collaborative process (Moss et al., Citation2021). In addition to the difficulty of facilitating a hybrid event, inequalities and power dynamics between stakeholders, which a diversity and co-production approach typically addresses, require even greater attention to prevent conflicts and exclusion (Turnhout et al., Citation2020; Wilkerson et al., Citation2020). These difficulties could be prevented with training and preparation before the participatory process, clarification of the goals and expectations of the process and the presence of an expert with facilitating skills (Holzer et al., Citation2023; Leitch et al., Citation2015).

5. Conclusions

We document the evolution of stakeholder involvement in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves since the MAB program started over 50 years ago. This study demonstrates through a diversity of data sources that stakeholder participation has become more prevalent in European Biosphere Reserves over time.

The literature review of MAB strategic documents indicated an evolution in the importance of stakeholder participation in all activities of Biosphere Reserves over time. Case studies showed that this increased importance also happened in Biosphere Reserves across Europe.

Results from the European longitudinal survey and Biosphere Reserve case studies showed a significant increase of participation and in the diversity of stakeholders involved in decision-making and management of Biosphere Reserves.

Even though no significant increase was observed at the information level, the means to dialogue with a diversity of stakeholders have increased since the pandemic started, with the increased use of Information and Communication Tools.

Our follow-up questionnaire pointed out a higher diversity and number of stakeholders involved when using online tools. However, the SWOT analysis showed both opportunities and challenges regarding using Information and Communication Tools for participation in Biosphere Reserves.

Hybrid methods (in-person and online participation) seem to be new participatory tools Biosphere Reserve managers are willing to try to overcome the challenges encountered in pure online settings.

Hence, more studies of the hybrid method and its influence on the diversity of stakeholders participating in Biosphere Reserve activities are needed due to concerns on potential challenges and power dynamics at play in a hybrid format. In particular, it would be interesting to interview other stakeholder groups to get a wider set of perspectives on stakeholder participation in BRs, following the work of Schultz et al. (Citation2018) on the meaning of BRs, but related to the use of online tools.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (262.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Lisen Schultz for allowing us to use her data from 2008 for the analysis of the European Longitudinal Survey. Marie Curtet thanks her supervisors at the Master’s program Man and Biosphere at the University Toulouse III-Paul Sabatier in France for their support during the first steps of this research. We thank all the interviewees for their time and the valuable insights they provided through participating in interviews and answering the questionnaire and surveys. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Arts, K., van der Wal, R., & Adams, W. M. (2015). Digital technology and the conservation of nature. Ambio, 44(S4), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-015-0705-1

- Baird, J., Plummer, R., Schultz, L., Armitage, D., & Bodin, Ö. (2018). Integrating conservation and sustainable development through adaptive co-management in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Conservation and Society, 16(4), 409–419. https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_17_58

- Baird, J., Plummer, R., Schultz, L., Armitage, D., & Bodin, Ö. (2019). How does socio-institutional diversity affect collaborative governance of social–ecological systems in practice? Environmental Management, 63(1), 16–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-018-1105-7

- Barclay, C., & Osei-Bryson, K. M. (2010). Project performance development framework: An approach for developing performance criteria & measures for information systems (IS) projects. International Journal of Production Economics, 124(1), 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2009.11.025

- Bazeley, P. (2018). A foundation for integrated analysis. In P. Bazeley (Ed.), Integrating analyses in mixed methods research (pp. 1–2). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Biggs, R., Schlüter, M., Biggs, D., Bohensky, E. L., Burnsilver, S., Cundill, G., Dakos, V., Daw, T. M., Evans, L. S., Kotschy, K., Leitch, A. M., Meek, C., Quinlan, A., Raudsepp-Hearne, C., Robards, M. D., Schoon, M. L., Schultz, L., & West, P. C. (2012). Toward principles for enhancing the resilience of ecosystem services. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 37(1), 421–448. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-051211-123836

- Bioret, F. (2001). Biosphere reserve manager or coordinator? Parks, 11(1), 26–29.

- Bonsaksen, T., Ruffolo, M., Leung, J., Price, D., Thygesen, H., Schoultz, M., & Geirdal, AØ. (2021). Loneliness and its association with social media use during the COVID-19 outbreak. Social Media and Society, 7(3), 1–10.

- Bouamrane, M. (Ed). (2006). Biodiversity and stakeholders: Concertation itineraries. Biosphere Reserves – Technical notes 1 (pp. 1–84). UNESCO.

- Bouamrane, M. (Ed.). (2007). Dialogue in biosphere reserves: References, practices and experiences. Biosphere Reserves – Technical notes 2 (pp. 1–81). UNESCO.

- Bouamrane, M., Spierenburg, M., Agrawal, A., Boureima, A., Cormier-Salem, M. C., Etienne, M., Le Page, C., Levrel, H., & Mathevet, R. (2016). Stakeholder engagement and biodiversity conservation challenges in socialecological systems: Some insights from biosphere reserves in Western Africa and France. Ecology and Society, 21(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08812-210425

- Brenner, L. (2019). Multi-stakeholder platforms and protected area management: Evidence from El vizcaíno biosphere reserve, Mexico. Conservation and Society, 17(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.4103/cs.cs_18_63

- Cash, D., Clark, W. C., Alcock, F., Dickson, N. M., Eckley, N., & Jäger, J. (2002). Salience, credibility, legitimacy and boundaries: Linking research, assessment and decision making. Assessment and Decision Making (November 2002).

- Cullen-Knox, C., Eccleston, R., Haward, M., Lester, E., & Vince, J. (2017). Contemporary challenges in environmental governance: Technology, governance and the social licence. Environmental Policy and Governance, 27(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1743

- D'Aquino, P. (2002). Accompagner une maîtrise ascendante des territoires, prémices d'une géographie de l'action territoriale. Mémoire d’habilitation à diriger les recherches. Université de Provence Aix Marseille 1, Aix en Provence (pp. 1–31).

- Dealtry, T. R. (1992). Dynamic SWOT analysis. Developer’s guide (pp 1–103). Dynamic SWOT Associates.

- Donnellan-Barraclough, A., Schultz, L., & Måren, I. E. (2021). Voices of young biosphere stewards on the strengths, weaknesses, and ways forward for 74 UNESCO biosphere reserves across 83 countries. Global Environmental Change, 68, 102273, 1–10.

- Dwivedi, A. K. (2021). Role of digital technology in freshwater biodiversity monitoring through citizen science during COVID-19 pandemic. River Research and Applications, 37(7), 1025–1031. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3820

- Esteban-Navarro, MÁ, García-Madurga, MÁ, Morte-Nadal, T., & Nogales-Bocio, A. I. (2020). The rural digital divide in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe—Recommendations from a scoping review. Informatics, 7(4), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/informatics7040054

- Fraser, H., Soanes, K., Jones, S. A., Jones, C. S., & Malishev, M. (2017). The value of virtual conferencing for ecology and conservation. Conservation Biology, 31(3), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12837

- George, C., & Reed, M. G. (2016). Building institutional capacity for environmental governance through social entrepreneurship: Lessons from Canadian biosphere reserves. Ecology and Society, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08229-210118

- Guedes-Santos, J., Correia, R. A., Jepson, P., & Ladle, R. J. (2021). Evaluating public interest in protected areas using Wikipedia page views. Journal for Nature Conservation, 63, 126040, 1–7.

- Holzer, J. M., Baird, J., & Hickey, G. M. (2023). The who, what, and how of virtual participation in environmental research. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 5(4), 1-7.

- Hovardas, T. (2021). Social sustainability as social learning: Insights from multi-stakeholder environmental governance. Sustainability, 13(14), 7744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147744

- ITU. (2017). ITU Council Contribution to the high-level political forum on sustainable development (HLPF), Council Working Group on the World Summit on the Information Society, 30th meeting, Geneva (pp. 1-15).

- Kangas, J., & Store, R. (2003). Internet and teledemocracy in participatory planning of natural resources management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 62(2), 89–101.

- Lai, J., & Widmar, N. O. (2021). Revisiting the digital divide in the COVID-19 era. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1002/aepp.13104

- Leitch, A. M., Cundill, G., Schultz, L., & Meek, C. L. (2015). Principle 6-broaden participation. In R. Biggs, M. Schlüter, & M. L. Schoon (Eds.), Principles for building resilience: Sustaining ecosystem services in social-ecological systems (pp. 201–225). Cambridge University Press.

- Lopez-Ercilla, I., Espinosa-Romero, M. J., Fernandez Rivera-Melo, F. J., Fulton, S., Fernández, R., Torre, J., Acevedo-Rosas, A., Hernández-Velasco, A. J., & Amador, I. (2021). The voice of Mexican small-scale fishers in times of COVID-19: Impacts, responses, and digital divide. Marine Policy, 131, 104606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104606

- Mammadova, A., Ali, N., & Chaiyasarn, K. (2022). Can online learning about UNESCO Biosphere Reserves change the perception on SDGs and different aspects of sustainability between Japanese and international students? Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(13), 1–14.

- Måren, I. E., Wiig, H., Mcneal, K., Wang, S., Zu, S., Cao, R., Fürst, K., & Marsh, R. (2022). Diversified farming systems: Impacts and adaptive responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Norway and China. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 6, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.887707

- Mohedano Roldán, A., Duit, A., & Schultz, L. (2019). Does stakeholder participation increase the legitimacy of nature reserves in local communities? Evidence from 92 Biosphere Reserves in 36 countries. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(2), 188–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2019.1566058

- Moss, V. A., Adcock, M., Hotan, A. W., Kobayashi, R., Rees, G. A., Siégel, C., Tremblay, C. D., & Trenham, C. E. (2021). Forging a path to a better normal for conferences and collaboration. Nature Astronomy, 5(3), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-021-01325-z

- Ospina, A. V., & Heeks, R. (2011). ICTs and climate change adaptation: Enabling innovative strategies. Strategy brief-1. In A. V. Ospina & R. Heeks (Eds.), Climate change, innovation & ICTs project (pp. 1–9). Centre for Development Informatics of the University of Manchester, UK.

- Pantić, M., Cilliers, J., Cimadomo, G., Montaño, F., Olufemi, O., Mallma, S. T., & van den Berg, J. (2021). Challenges and opportunities for public participation in urban and regional planning during the COVID-19 pandemic—Lessons learned for the future. Land, 10(12), 1379–. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121379

- Plummer, R., Baird, J., Armitage, D., Bodin, Ö, & Schultz, L. (2017). Diagnosing adaptive co-management across multiple cases. Ecology and Society, 22(3), 19. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09436-220319

- Plummer, R., Dzyundzyak, A., Baird, J., Bodin, Ö, Armitage, D., & Schultz, L. (2017). How do environmental governance processes shape evaluation of outcomes by stakeholders? A causal pathways approach. PLoS One, 12(9), e0185375. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185375

- Raby, C. L., & Madden, J. R. (2021). Moving academic conferences online: Aids and barriers to delegate participation. Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 3646–3655. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7376

- Raymond, C. M., Cebrián-Piqueras, M. A., Andersson, E., Andrade, R., Schnell, A. A., Battioni Romanelli, B., Filyushkina, A., Goodson, D. J., Horcea-Milcu, A., Johnson, D. N., Keller, R., Kuiper, J. J., Lo, V., López-Rodríguez, M. D., March, H., Metzger, M., Oteros-Rozas, E., Salcido, E., Sellberg, M., … Wiedermann, M. M. (2022). Inclusive conservation and the post-2020 global biodiversity framework: Tensions and prospects. One Earth, 5(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2022.02.008

- Redecker, C., Ala-Mutka, K., & Punie, Y. (2010). Learning 2.0: The impact of social media on learning in Europe. Policy Brief, Report number:JRC56958 Affiliation (pp. 1–17). European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Prospective Technological Studies.

- Reed, M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation, 141(10), 2417–2431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

- Richter, I., Avillanosa, A., Cheung, V., Goh, H. C., Johari, S., Kay, S., Maharja, C., Nguyễn, T. H. à., Pahl, S., Sugardjito, J., Sumeldan, J., van Nguyen, Q., Vu, H. T., Wan Mohamad Ariffin, W. N. S., & Austen, M. C. (2021). Looking through the COVID-19 window of opportunity: Future scenarios arising from the COVID-19 pandemic across five case study sites. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(July), 1–12.

- Schliep, R., & Stoll-Kleemann, S. (2010). Assessing governance of biosphere reserves in Central Europe. Land Use Policy, 27(3), 917–927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.12.005

- Schultz, L., Duit, A., & Folke, C. (2011). Participation, adaptive co-management, and management performance in the world network of Biosphere Reserves. World Development, 39(4), 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.09.014

- Schultz, L., West, S., Juaréz Bourke, A., d’Armengol, L., Torrents, P., Hardardottir, H., Jansson, A., & Mohedano Roldán, A. (2018). Learning to live with social-ecological complexity: An interpretive analysis of learning in 11 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves. Global Environmental Change, 50, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.03.001

- Schwilch, G., Bachmann, F., Valente, S., Coelho, C., Moreira, J., Laouina, A., Chaker, M., Aderghal, M., Santos, P., & Reed, M. S. (2012). A structured multi-stakeholder learning process for sustainable land management. Journal of Environmental Management, 107, 52–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.04.023

- Sinclair, A. J., Peirson-Smith, T. J., & Boerchers, M. (2017). Environmental assessments in the internet age: The role of e-governance and social media in creating platforms for meaningful participation. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 35(2), 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2016.1251697

- Souza, C. N., Rodrigues, A. C., Correia, R. A., Normande, I. C., Costa, H. C. M., Guedes-Santos, J., Malhado, A. C. M., Carvalho, A. R., & Ladle, R. J. (2021). No visit, no interest: How COVID-19 has affected public interest in world’s national parks. Biological Conservation, 256, 109015. 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.109015

- Sowińska-Świerkosz, B., & Chmielewski, T. J. (2014). Comparative assessment of public opinion on the landscape quality of two biosphere reserves in Europe. Environmental Management, 54(3), 531–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-014-0316-9

- Stoll-Kleemann, S., De La Vega-Leinert, A. C., & Schultz, L. (2010). The role of community participation in the effectiveness of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve management: Evidence and reflections from two parallel global surveys. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S037689291000038X

- Taipale, S., Petrovcic, A., & Dolnicar, V. (2018). Intergenerational solidarity and ICT usage: Empirical insights from Finnish and Slovenian families. In S. Taipale, T.-A. Wilska, & C. Gilleard (Eds.), Digital technologies and generational identity: ICT usage across the life course (pp. 69–86). Routledge. Routledge Key Themes in Health and Society.

- Tengö, M., Brondizio, E. S., Elmqvist, T., Malmer, P., & Spierenburg, M. (2014). Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: The multiple evidence base approach. Ambio, 43(5), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-014-0501-3

- Thabrew, L., Wiek, A., & Ries, R. (2009). Environmental decision making in multi-stakeholder contexts: Applicability of life cycle thinking in development planning and implementation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.03.008

- Turnhout, E., Metze, T., Wyborn, C., Klenk, N., & Louder, E. (2020). The politics of co-production: Participation, power, and transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 42(2018), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009

- UNESCO. (1984, December). Action plan for biosphere reserves. Nature and Resources, XX(4), 1–16.

- UNESCO. (1996). Biosphere reserves: The Seville strategy and the statutory framework of the world network (pp. 1–21).

- UNESCO. (2008). Madrid action plan for Biosphere Reserves (2008-2013) (pp. 1–33). UNESCO.

- UNESCO. (2017). A new roadmap for the man and the biosphere (MAB) programme and its world network of Biosphere Reserves (pp. 1–47). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- UN General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1, 1–35.

- Van Cuong, C., Dart, P., & Hockings, M. (2017). Biosphere reserves: Attributes for success. Journal of Environmental Management, 188, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.11.069

- Vargo, D., Zhu, L., Benwell, B., & Yan, Z. (2021). Digital technology use during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 3(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.242

- Warner, J. F. (2007). The beauty of the beast: Multi-stakeholder participation for integrated catchment management. In J. F. Warner (Ed.), Multi-stakeholder platforms for integrated water management (pp. 1–20). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Wilkerson, B., Aguiar, A., Gkini, C., Czermainski de Oliveira, I., Lunde Trellevik, L. K., & Kopainsky, B. (2020). Reflections on adapting group model building scripts into online workshops. System Dynamics Review, 36(3), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1662

- Yang, S., Fichman, P., Zhu, X., Sanfilippo, M., Li, S., & Fleischmann, K. R. (2020). The use of ICT during COVID -19. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 57(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.297