ABSTRACT

This article reflects on the development of green infrastructure as planning concept and inspects the status of the concept’s implementation under the umbrella of the EU-strategy for the Alpine Region. Qualitative methods, including policy analysis and interviews, were used to evaluate the understanding of the concept among relevant stakeholders from Alpine countries. The results show that there is little agreement with regard to understanding the concept, and that there was a lack of common practice towards its implementation in the 2014–2020 EU budget period. The macro-regional setting consists of the macro regional strategy and the financial support for projects and measures provided via the Alpine Space Programme and The Alpine Region Preparatory Action Fund (ARPAF). The policy analysis reveals that some of the Alpine countries were more pro-active and have either integrated the concept into existing policies (nature protection, planning, environmental policies and so on) or possess GI specific legislation. It was concluded that the existence of various perceptions and views on the concept hinder the successful implementation of the concept and its integration into lower governance levels. Thus, for now, the implementation of GI in the macro-regional context depends upon individual initiatives of the states, regions, or/and local communities.

1. Introduction

In the twenty-first century, countries and regions around the world face environmental problems, such as pollution, climate change, degradation of soils and loss of habitats and biodiversity (MEA, Citation2005; Connop et al., Citation2016; Staccione et al., Citation2022). To manage and solve these problems in spatial planning, green infrastructure (GI) has been suggested as a planning and management concept (e.g. Hoover et al., Citation2021; Mell, Citation2021; Perrin et al., Citation2022). As Lennon (Citation2015) and other authors (Amati & Taylor, Citation2010; Jerome, Citation2017; Lennon et al., Citation2017; Mertens et al., Citation2022) argue, the term has become widely recognised internationally, especially during the last decade. Its aim is to establish more integrative planning and management of green areas, including nature protection sites and cultivated landscapes, as well as urban open spaces, in a singular, comprehensive, and progressive manner (Mell, Citation2016). The GI concept is often considered at a range of diverse local and transnational governance and planning levels, within different sectoral policies, and among various actors from across the public domain (Schubert et al., Citation2018). It has become one of the ‘meta-terms’ by which to combat a wide range of (environmental) challenges, alongside planning concepts such as smart cities, resilience, and sustainability. To realise GI benefits, knowledge of both natural and social systems should be applied within GI planning and a solid integration of the concept should be secured in urban and rural policy making (Willems et al., Citation2021).

In the European Union, the GI concept has gained wider political recognition via the EU Strategy on Green Infrastructure (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 3) which defines GI as

‘a strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. It incorporates green spaces (or blue if aquatic ecosystems are concerned) and other physical features in terrestrial (including coastal) and marine areas. On land, GI is present in rural and urban settings.’

Against this background, this article discusses the implementation of the GI approach in the Alpine macroregional governance setting and to what extent the claim from the previous paragraph has been already fulfilled. It highlights the opportunities and challenges that exist in transferring the GI approach – streamlined by the EU Commission – to a multi-level governance system which combines a range of different actors from various scales and backgrounds. The Alpine region was selected as the case study because it has a well-established territorial governance framework (Teston & Bramanti, Citation2018). Accordingly, the novelty of the article lies in its analysis of the transnational and macro-regional setting as an important European policy instrument; thus, it extends the focus of existent literature that has tended to focus mainly on local and national contexts (e.g. Travaline et al., Citation2015; Schubert et al., Citation2018; Hoover et al., Citation2021; Mell, Citation2021). The key research questions addressed herein are: How is the GI approach translated into the macro-regional governance setting? What kind of multi-governance framework exists and how does it work in relation to GI? In addition, this article also looks at lessons learned from the implementation of GI at the specific Alpine macro-regional context and how these can be applied to territorial governance theory more broadly.

The article is structured in six parts: in part 2 the overview of the green infrastructure theory with the focus on territorial governance and EU macro-regional strategies. In part 3 methodology is presented, while the part 4 provides the results of the study. The article concludes with discussion (part 5) about the research questions and conclusion (part 6).

2. Green infrastructure, territorial governance, and the EU’s macro-regional strategies

2.1. Green infrastructure

Despite its relative novelty, the green infrastructure concept did not emerge ‘out of the blue‘; concept had several predecessors in history (Lennon, Citation2015; Mertens et al., Citation2022), in particular reflecting the negative effects of industrialisation and urbanisation on the quality of both the natural and human environments, some predecessors of the concept can be found: Olmstead’s Emerald Necklace in Boston is among the first attempts of linking urban green areas into urban system, as are Howards’ Garden Cities, and European urban green belt development (e.g. Hayes & Dockerill, Citation2023; Mell, Citation2016). These early concepts and examples focused primarily on providing healthier environments for people, whereas latter applications of the concept have put more emphasis on the natural environment (Gobster, Citation1995) or environmental protection (Zmelik et al., Citation2011).

The first use of the term ‘green infrastructure’ itself, is generally credited to the Florida Greenway Commission’s report of 1994 on land conservation strategies. In this report, GI was presented as a new way of understanding conservation demands (Rouse & Bunster-Ossa, Citation2013). Since then, the concept has expanded geographically and contextually, and is nowadays well-known among spatial and landscape planning practitioners, academics, and policy makers (Monteiro et al., Citation2022; Perrin et al., Citation2022; Grabowski et al., Citation2022). The expansion of the concept has resulted in the development of various interpretations, lending it a ‘fuzzy’ notion (Hansen et al., Citation2021; Mertens et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, overlaps with other terms can also be observed, e.g. ecosystem services, nature-based solutions, ecological connectivity, greenways, and so on (Fabos, Citation2004; Ahern, Citation2007).

Over the past 25 years, most GI definitions have centred around two basic interpretations. Early definitions focused on establishing green infrastructure as a physical network of green areas and here, the pioneers of the GI concept, Benedict and McMahon (Citation2002) defined it as ‘an interconnected network of green space that conserves natural ecosystem values and functions and provides associated benefits to human populations’ (p. 12). Understanding nature/green areas as a network or infrastructure illustrated an important development from the previously adopted ‘island approach’ in nature protection (Taylor et al., Citation1993; Dramstad et al., Citation1996). Later, Benedict and McMahon expanded the concept by adding a planning and management aspect to the definition (Rouse & Bunster-Ossa, Citation2013). It now envelopes more active conservation in which green areas are not seen just as ‘development leftovers’, but as a system that should be planned along with other land use categories. The EU Strategy on Green Infrastructure’s definition (European Commission, Citation2013) adopts this approach and emphasizes (a) the need for planning GI strategically, (b) the diversity of its elements, and (c) the functions it provides which benefit both nature and society. This broader interpretation is also the result of the evolution of GI as a concept, and its merging with other aspects, such as considering the possibilities of ‘building’ new GI, instead of just protecting existing areas (Lennon, Citation2015; Mertens et al., Citation2022). As a result, the GI approach has expanded from focussing on physical systems to become an approach for strategic planning. The EU Strategy on Green Infrastructure (p. 2) stresses that: ‘GI is a successfully tested tool for providing ecological, economic and social benefits through natural solutions.’ The EU strategy definition bears a strong resemblance to landscape planning, which is a well-known concept (Crowe, Citation1969; Mertens et al., Citation2022) and reconciliates development needs and conservation demands from various sectors (e.g. water management, nature conservation, etc.) in order to achieve ‘the best possible long-term social and economic benefits for man, as well an ecologically balanced, diversified landscape as a healthy environment for man and other forms of life’ (Žak et al., Citation1971).

Since its introduction in academic discourse, GI has become a part of/or the main focus of European policies and strategies (e.g. The EU Biodiversity strategy, Common Agricultural Policy). Furthermore, it has entered national legislation, including in the UK, Ireland, Spain (LLausàs & Roe, Citation2012; Lennon, Citation2015) and has been implemented at a regional/urban level through several transnational projects, e.g. ESPON Greta, PERFECT, GREEN SURGE. Within these contexts, GI seeks to provide (often very conflicting) goals such as multi-functioning landscapes, as well as environmental, social, and economic benefits. How these aims can be achieved in a multi-level governance setting provided by the EU’s macro-regional strategies is highlighted in the next section by the article first noting the theoretical background of territorial governance, and thereafter introducing the specifics of macro-regional governance in the EU context.

2.2. Territorial governance and the role of macro-regional strategies

Multi-level or territorial governance has been discussed and conceptualised in detail over the last 30 years, starting with the observations of Marks (Citation1993) as to how various layers of government were being nested in territorially overarching, policy networks. These layers formed new patterns of collaboration, both between units of government and between governmental and non-governmental actors and, as a result, it became essential to know how these borders were (and are) drawn, functions allocated, and levels of autonomy defined (Lidström, Citation2007). A range of authors have attempted to gain a better understanding of shifts in territorial governance in the EU with ESPON projects TANGO and COMPASS providing important inputs for the overall picture as well as member state specific data (Faludi, Citation2012; Stephenson, Citation2013; Stead, Citation2014; Cotella, Citation2020). One of the very first policy-related institutions to promote and elaborate on the concept was the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Back in 2001 the organisation (p. 142) defined territorial governance as

‘the manner in which territories of a national state are administered and policies implemented, with particular reference to the distribution of the roles and responsibilities among the different levels of government (supranational, national and subnational) and the underlying processes of negotiation and consensus-building.’

coordinating actions of actors and institutions;

integrating policy sectors;

mobilising stakeholder participation;

being adaptive to context change;

realising place based/territorial specificities and impacts.

In the context of the European Union, macro-regional strategies are initiated and requested by EU and non-EU Member States that are in the same geographical area via the European Council. By definition ‘macro-regional strategy is a policy framework which allows countries located in the same region to jointly tackle and find solutions to problems or to better use the potential they have in common’ (European Commission, Citation2017, p. 1). Subsequently, these strategies were researched concerning, e.g. their impact on governance and policy making. Macro-regional approaches are delineated based on functional or natural territories rather than on administrative boundaries, and therefore tend to function outside of the formal national and European structures of government (see, amongst others, Stead et al., Citation2016; Gänzle, Citation2017). Confirming this, Stocchiero (Citation2015, p. 155) argues that ‘macro-regional strategies contribute to on-going rescaling and increasing complexity of the European polity, while offering the opportunity for a better policy co-ordination at a plurality of geographical scales’.

Authors like Teston and Bramanti (Citation2018) have elaborated specifically about governance in the EUSALP context. Among weaknesses noted, they primarily identified governance characteristics whose origins lay in the quite diverse national governance settings of the Alpine countries, a certain degree of malfunctioning co-operation, the different extents of national involvement, and a lack of accountability. Bramanti and Rosso (Citation2007) predicted that for such co-operation to work, regions need to recognise each other, and uncover unifying elements whilst also counteracting factors that would normally limit or obstruct co-operation. Amongst positives noted were the coexistence of the EUSALP strategy and financial support, together with the history of successful co-operation, and the ability to govern the provision and exploitation of collective goods (Teston & Bramanti, Citation2018).

Although the idea of macro-regional strategies came specifically from the identified governance gap between the EU and national levels (Belloni, Citation2020), setting it up and getting it established in the already complicated vertical governance structure has not proven to be easy (Bianchi, Citation2016; Gløersen et al., Citation2019; Belloni, Citation2020; Solly & Berisha, Citation2021). Various authors have already elaborated on the functioning of macro-regional strategies by analysing issues such as: sustainable tourism projects (Teston & Bramanti, Citation2018), the implementation of smart specialisation policies (Meyer, Citation2020), and stakeholders’ perspectives (Sielker, Citation2016; Plangger, Citation2019). This article adds to this corpus of knowledge by focusing on the question of how helpful EUSALP macro-regional strategy is in supporting and governing GI implementation in the Alpine area.

3. Methodology

The study builds on two main methodological approaches:

(1) Desk-based research including a literature review of GI, a policy analysis of the EUSALP context, and an analysis of existing GI projects, their scope, and their results.

(2) Interviews with relevant stakeholders who are related to the GI topic but come from different Alpine countries and possess different professional backgrounds and functions.

This methodological approach resembles the approach of Gerlak et al. (Citation2021), who investigated the implementation of the GI concept in urban contexts. Similarly, the policy analysis is based on a structured review of existing policies and studies which focus on GI governance. The starting point was the study of the ESPON GRETA project. This was undertaken in the context of the Alpine Macro-region (ESPON, Citation2018) where the authors reviewed strategic policies and other relevant documents in relation to GI at regional, national, and European levels including: other national sectoral policies, transnational conventions, the Alpine Space operational programme 2014–2020, the action plans of selected EUSALP action groups, relevant legislation, and so on.

An important input of the desk-based research were selected projects on GI planning and governance, as they provided information pertaining to policy analysis, governance models, geographical information, and the GI characteristics of the Alpine area. These projects adopted one of the two following approaches to GI: GI as a strategic planning instrument applied at a macro-scale level in order to connect and unify the management of green areas (e.g. LOS_DAMA!, ALPBIONET, MAGICLandscapes); and GI applied as individual interventions at a micro scale and usually in an urban context (e.g. UrbanGreenBelt and GreenSurge projects).

In the second step, interviews with selected stakeholders were conducted. The list of interviewees included members of the EUSALP Action Groups (especially AG7 with the focus on developing ecological connectivity and thus strengthening, improving and restoring biodiversity, as well as ecosystem services.), as well as other experts on the topic. Interviewees came from different professional backgrounds and types of public institutions: seven were from federal/national/state ministries, two from NGOs, and two regional development agencies, and one each from a city administration, a state nature protection institute, a European transnational programme, and a research institute. Regarding national representations, four persons from Germany, three from both Italy and Slovenia, and one each from Austria, Switzerland, and France were interviewed.

In total, 15 interviews took place via a semi-structured, qualitative questionnaire. The questions focused on aspects such as definitions and understanding of the GI concept, information about the current implementation of GI in the Alpine area and via EUSALP, and national governance settings and policies, as well as relevant actors and their current co-operation levels on the topic of GI (for more details and the full questionnaire see Marot et al., Citation2019). The interviews were conducted in three languages (Slovene, English, German) via telephone between May 13th and June 28th 2019.

For this article, the results from both research steps were analysed to describe and interpret three governance elements which are all equally important for the implementation of GI in the Alpine region (see section 4 presenting the results): the policy framework, the institutional setting, and the funding instruments. Additionally, the research yielded results about the general understanding of the GI concepts that existed between and among the interviewed actors; relevant for reflecting on issues of common understanding.

4. Results

4.1. Policy framework for implementation of GI in the Alps

4.1.1. General setting

Regarding actual policymaking within the Alpine area, three pillars with relevance to GI can be identified. The Alpine Convention (AC, Citation1991) presents the first policy pillar which aims to protect the Alps and their sustainable development (Del Biaggio, Citation2015). The treaty is accompanied by several protocols to the Alpine Convention (AC), with the most relevant regarding GI and ecological connectivity being the ‘Protocol for the implementation of the Alpine Convention in the field of cross-border nature protection and landscape conservation’ (AC, Citation1991). Additionally, consideration of biodiversity and ecosystems as economic assets were sought in the recent Report on the State of the Alps ‘Greening the Economy in the Alpine region’ (Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention, Citation2017).

The second policy pillar in the Alpine region is the EU’s strategy for the Alpine Region (EUSALP); one of the 4 macro-regional strategies of the European Union (Balsiger, Citation2016). Since its establishment in 2015, the EUSALP has developed into a major governance body in the Alpine area with several actors being involved (Teston & Bramanti, Citation2018). Its action groups work on topics relevant to the Alpine region. Here, EUSALP Action Group 7 is responsible for the development of ecological connectivity and the application of the EU Strategy for GI to regional scales in the Alpine region. The action group initiated the ‘Alpine Green Infrastructure joint declaration’ (EUSALP, Citation2017). The document sets out to establish the concept at a macro scale, emphasises the benefits of GI, and provides appropriate funding, as well as cross-territorial and cross-sectoral governance mechanisms. It aims is to inspire the implementation of GI in other mountain areas and other macro-regional strategies in Europe.

As the third policy pillar, the EU’s Alpine Space INTERREG cooperation programme (ASP) offers a flexible funding mechanism for projects that align with EUSALP’s priorities. The programme is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) under the European transnational co-operation instrument. Every seven years, the priority objectives are defined, paving the way for funding projects. Here, the GI concept only gained importance in the second half of the 2014–2020 funding period (3rd programme priority axis), while ecological connectivity was more relevant in the 1st half. In the new programming period (2021–2027), GI projects are funded in the priority axis 1 of the Alpine Space Programme.

4.1.2. Countries’ specific policy frameworks

As noted, the concepts of GI and ecological connectivity are now being directly and indirectly incorporated into numerous policies at both EU and transnational levels (e.g. EUSALP, Citation2017; Marot et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, environmental policies are not tailored to specific areas, and this hampers the transferability of policies across national and regional contexts within the EU (Ghermandi et al., Citation2013; Gløersen et al., Citation2016). Although a specific targeted GI strategy was created at the EU level in 2013 (European Commission, Citation2013), it is important to note that only 11 out of 32 ESPON member states have, thus far, developed GI specific policies at a national level (ESPON, Citation2018). In a majority of cases, GI-related policies and practices are (only) addressed in sectoral policies, such as land use and spatial development planning. Even if policies have been adopted at a national level, adaptation at a regional level has been rather ambiguous (Svadlenak-Gomez et al., Citation2014; Liquete et al., Citation2015; Marot et al., Citation2019).

In Alpine countries an additional set of policies aimed towards GI have previously been ratified at a transnational level (i.e. ‘Alpine Green Infrastructure Joint Declaration’), but the main GI policies of individual nations have occurred in various forms. The results of this study’s desk-based assessment indicate that most of the policies on GI were strategies (8) and laws (9), which were accompanied by a series of concepts or guidelines. Different policy approaches to GI and the inclusion of specific GI policies are only present in France and Germany, while the other countries have incorporated GI-relevant polices into sectoral polices, such as planning or nature protection. It also transpires that the national level presents the most important policy level, not only developing and translating GI aspects into policies, but also leading their implementation.Footnote1 Only Germany and Switzerland have depicted their respective regional levels of governance as being responsible for implementation.

4.2. Assessment of the institutional setting

In a further research step in the interviews, stakeholders were asked to comment on institutional settings, the efficiency of EUSALP action groups, actors’ co-operation within (in)formal GI networks, and other stakeholders. From this, the importance of individual actors and administrative levels in the governance of GI was identified and evaluated. In accordance with Section 4.1.1, most interviewees identified three core institutions for the implementation of GI in the Alpine area: EUSALP, the Alpine Space Programme, and the Alpine Convention.

The EUSALP action groups were identified as the main organisational structure which supports implementation of GI in the Alpine setting. The following GI aspects within EUSALP are addressed primarily: ecological connectivity (addressed by AG7), natural resources, including water and cultural resources (AG6), climate change and natural risks prevention (AG8), and energy efficiency and renewable energy (AG9). From this, it can be argued that he GI topic is well represented within the priority policy topics of the EUSALP. Nevertheless, the first notion is that the representation of individual countries in the AG7 is not equally balanced with some countries having no representatives at all in certain AGs.

The second notion concerns the engagement and participation of stakeholders in the macro regional setting. Actors can engage and network via the AGs, projects, international associations, networks, and other institutional settings. The predominant opinion of the interviewees was that the level and quality of co-operation vary due to a lack of available time and other workload issues. For example, the Alpine Space Programme representative reported that they co-operated in all AGs and are present in the Alpine convention, but they sought more active and present engagement than participating in one meeting per annum. However, the actors involved agreed that there was good overall GI representation in the EUSALP, the ASP, and the Alpine Convention, especially when compared to other more sectoral orientated networks and organisations.

The third notion relates to the knowledge and competences presented in the given institutional settings. According to the interviewees, the most important competences for GI governance are predominantly related to the spatial planning sector and include knowledge and skills for strategic planning, knowledge of planning documents and instruments, as well as nature protection instruments, and possession of the requisite skills needed for co-operative, participatory, and cross-sectoral work. To grasp the concept, one should be able to comprehensively apprehend the territory and territorial processes. Possession of a multidisciplinary perspective was exposed as the key ‘know-how’ for GI governance.

The fourth notion focuses on the most suitable administrative level for GI governance. The interviewees were unified in their opinion that there is a need for an inter-sectoral approach, and that this should – in general – be steered by federal/national level administration. It was best described by the words ‘there is a cascade of policies on different levels interconnected with each other – from EU to municipal level’ (Marot et al., Citation2019). Mostly persons agreed with the top-down approach in which the federal level and EU are the drivers of GI implementation. However, one German representative stated that municipal level actors need to be involved in decision making, as they are responsible for implementation. In their opinion, the local planning sector should take over the management role of coordinating sectors and establish an integrative planning governance model which is able to set up a strategic framework, and guidelines, as well as objectives.

The fifth notion, finally, is that the interviewees also commented on institutional leadership for GI governance. The EUSALP was recognised as being the best and the most important because of its geographical coverage, its flexible participation, its multifunctional character (via the availability of other AGs), and its ability to perpetrate vertically through multi-level governance systems. Furthermore, it was seen to join stakeholders together not only via their political functions, but also through their interests and initiative. It was also seen as being relatively open to non-governmental actors. However, some weaknesses of the institution were also mentioned: no real decision-making power, only a few concrete actions performed so far, not enough broad inclusion of relevant stakeholders, no significant budget of its own, and its being a new structure when compared to other Alpine organisations.

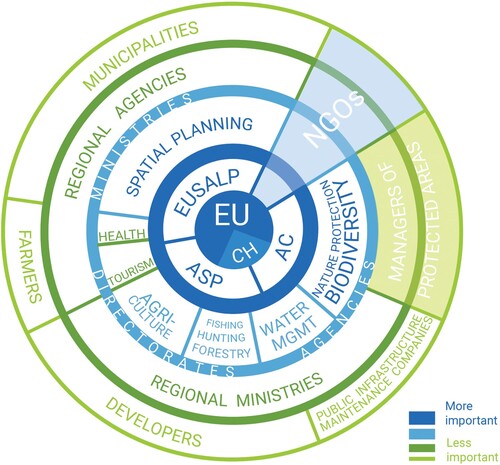

Based on the statements given by the interviewees, an optimised institutional setting depicting the relevant importance of institutions and actors is shown in . Many actors mentioned that close cooperation between the EUSALP (policies) and the ASP (funding) would be the most efficient and suitable governing solution for the future when transnational contexts are considered. Next to the macro-regional level institutional setting, a crucial role for transposing the GI concept should be assigned to national ministries and agencies in the fields of spatial planning, biodiversity, water management, and agriculture. The responsibility for implementing GI-related measures lies mostly within regional and local levels. NGOs, as actors active on the whole governance vertical, can serve as connectors of initiatives across different levels.

4.3. Understanding of the GI concept

With the policy landscape mapped, research then focused on the levels of understanding of the GI concept that existed amongst and between stakeholders. As a result of the interviews, it can be stated that the levels of understanding and interpreting of GI as a concept vary according to individual stakeholder’s countries of origin and their professional backgrounds. For instance, representatives from strategic planning (e.g. geographers, and landscape architects) emphasised the strategic and comprehensive function of the concept first, while persons with natural science backgrounds, such as biology and ecology, underlined its nature-related functions. While the official EU definition of GI was widely known and acknowledged amongst interviewees, understanding and interpretation of the GI concept varied in the following ways:

GI is a strategic planning approach, which focuses on protecting/enhancing and connecting naturally preserved areas for the benefit of society, the environment, and economies,

GI is an integrative, joint approach for addressing complex (cross-sectoral) problems – e.g. flooding,

GI is a strategically planned network, which connects habitats by establishing ecological corridors which enable the whole ecosystem to function and provides ecosystem functions.

In some of the investigated countries, the concept of ‘ecological connectivity’ was more acknowledged and used in practice. Aberrations of interpretation were described as either: GI and EcoC being synonyms; EcoC being understood as addressing issues on a wider scale, while GI focused only on regional levels or the opposite. Additionally, EcoC was mentioned as being part of GI, and was perceived to focus on naturally preserved areas and environmental issues, whereas GI was seen to also address social and economic issues.

4.4. Financial initiatives

With regards to financial incentives and other funding sources for GI implementation, this study’s analysis shows that implementation of GI mostly relies on EU funds due to there being few financial instruments for this topic available at a national level. Among the most important EU financial resources is the Alpine Space INTERREG programme. In its previous programme (2014–2020) GI-related projects were funded in priority 3 (‘Liveable Alps’). Here two different approaches within GI-related projects were found: strategic planning projects that developed GI governance models in larger territorial units; and urban initiatives that focused on singular GI-related interventions which were mostly carried out in cities. The INTERREG Cross-Border-Cooperation (CBC), co-financed also by ERDF, also enabled cross-border regions to co-operate in finding joint solutions which could be beneficial for the management of nature protected parks or river areas.

The Alpine Region Preparatory Action Fund (ARPAF), as the only financial initiative of the EUSALP, directly secured 2 million Euros from the EC to encourage small-scale projects. In the first call (in 2017), five projects were granted, but none of them covered GI topics. GI projects can also be financed by the LIFE programme, but these are primarily conservation focused rather than planning oriented, or through the LEADER programme, which should motivate Local Action Groups to declare GI as a priority for the rural development of their given area. A downside of this programme is its focus on specific bottom-up designated areas, which limits its applicability to GI projects at a macro level.

5. Discussion

The first outcome of this research is that perceptions of the GI concept are not unified across the Alpine area. This significantly limits the transfer potential of the concept into the macro-regional governance setting. This leads to terminological uncertainty and misunderstandings of the GI concept as highlighted in the interviews. The interviewees did not always understand the GI concept as an overarching planning approach that only partly shares goals with either the ecological connectivity or the ecosystem services approaches – instead, the terms tended to be used interchangeably. An additional difference relates to the geographical delineation of GI. Swiss and Austrian stakeholders put forward nature parks as important elements of GI, whereas German interviewees placed more emphasis on cities and urban areas. These views are well reflected within the nature protection traditions and policy documents related to GI in the respective countries. It was also frequently mentioned in the interviews that GI is a wide and fuzzy concept. In some cases, it was suggested that this has led to scepticism about whether there is really a need to establish or utilise (yet) another term for green, sustainable resource management. In particular, it was stated that the introduction of new terms needs approximately 10 years to be successfully established amongst actors and to be put into practice within existing governance frameworks (Marot et al., Citation2019).

Secondly, and connected to the first observation, GI as a policy tool, is underrepresented in Alpine countries. It is mostly integrated into planning policies (via green areas), nature protection policies (Natura 2000, connectivity), and water protection policy documents. Responsibility is split across various national agencies and actors, with only a few approaches across national bodies being evident. These various sectoral approaches as well as the different nature of legislation between countries hampers the wider implementation of the concept. Additionally, there are only a few policy documents that specifically target GI, such as Germany’s guidelines for implementing GI. This presents a governance dilemma, as GI is presently set in a rather integrative and collaborative approach which involves various sectors and policies. It is unclear if such an approach serves the concept best, or whether a single policy domain, e.g. planning, should take ownership and produce separate policy documents.

Thirdly, the macro-regional level has established clear, multi-stakeholder governance structures, in which GI is well placed; such as the AG7 of the EUSALP. Notwithstanding this, the frequency of co-operation between diverse stakeholders remains ad hoc and limited due to members having too many occupations and functions; they often participate in multiple transnational structures. Despite this, macro-regional institutions have pushed many GI-related policy activities forward, and through so doing have highlighted their capacities to act at least at a conceptual level.

Fourthly, the analysis of the initiatives and good practices showed that there is not enough evidence from practice to see the exact benefits of the concept’s implementation in practice. This may limit more proactive applications of the concept. None of the countries provides financial support for the implementation of the concept in planning practice, so actors need to rely on EU support instead or the individual initiatives of NGOs. Confirming the status quo of reliance on EU funds, in the Biodiversity Strategy 2030 (European Commission, Citation2020), Natura 2000 and green infrastructure are designated as investment priorities and at least €20 billion a year should be unlocked for these priorities. In the Alpine context, we can confirm that the Interreg programme ASP is the major implementation instrument.

6. Conclusion

In the context of GI, this study has shown that the implementation of a new planning concept is never a straightforward process; and especially so if it is implemented in a top-down manner. Although there is a guiding document in place at the EU level, the overall concept remains ambiguous and fuzzy for many actors across the Alpine area. Furthermore, the variety of different agencies which deal with GI within individual national contexts has not helped to streamline GI in policy making. Given the lack of clear governance, as well as the existence of discourses on other, partly overlapping concepts, aims, strategies and expectations about GI are not coherent among stakeholders. In addition, there is also a practice gap and a lack of good practice examples which highlight the benefits of GI-related policies. This leaves the GI concept rather stranded on an abstract level. According to Hansen et al. (Citation2021) we could declare a lack of ‘discursive concept development process’ that would shape the GI concept into ‘something useful and acceptable for diverse stakeholders’ (pp. 274–275) in the context of the Alpine macro-regional strategy.

As a penultimate consideration, there is a need to elaborate on the character of the collaboration within macro-regional strategies and territorial governance. First, this study’s analysis highlights the complex nature of cooperation in transnational settings and proves how difficult it is to translate a ‘top-down’-developed concept in a multi-actor governance setting. Thus, our study confirms the previous findings of both Wright (Citation2011) and Lennon (Citation2015). For governance-theory, the analysis in this article has revealed that the five dimensions of Well and Schmitt (Citation2015) in regard to territorial governance are being well addressed within the Alpine Space. Nevertheless, and with regards to GI within the specified dimensions of Well and Schmitt (Citation2015), namely the dimension (4) being adaptive to context change, and (5) realising place based/territorial specificities and impacts, obvious shortcomings can be detected both in the anchoring of the concept and its implementation. This is a rather sobering result, especially given that the EUSALP stakeholder community has been collaborating in a transnational way for decades – an advantage of timescale that is not shared by other European macro-regional strategies. Given this, one might question whether Roggeri’s (Citation2015, p. 146) statement that ‘the macro-regional approach demands deliberate willingness to achieve results together and openness and readiness for co-operation, i.e. ability to compromise on priorities and modalities’ is sufficient in this instance. In answer, it can be suggested that even with the willingness and openness of actors as vital prerequisites for any macro-regional cooperation, the preparation of a (formally) balanced and inclusive setting of actors within macro-regional settings (as addressed in dimensions 1–3), might not be sufficient. Rather it may be critical for the network to be conceptually adaptive and capable of implementing actions; much harder tasks that would demand constant involvement from stakeholders and enough administrative capacity to successfully implement territorial governance (Boehme et al., Citation2015).

Finally, some practical policy lessons and recommendations on EUSALP can be drawn. Firstly, a common understanding of the concept as well as a shared vision of GI should be established via a policy brief. Secondly, and in order to achieve better practical implementation, clear management roles between the different pillars of governance within the Alpine Area need to be assigned, and overall motivation to act on the topic should be increased. A solution might come from the macro-regional policy arena itself, through addressing the ‘practical’ gap by obtaining more direct funds to use on projects which yield local results and could serve as benchmarks for showing how macro-regional strategies can have practical benefit on the ground. In essence, a ‘learning by doing’ approach. Granting EUSALP and the ARPAF more funds to support initiatives directly would also increase the political legitimacy of the EUSALP (a solution that is relevant for other macro strategies as well). This would motivate stakeholders from lower administrative tiers to invest more of their time into the laborious task of multi-level governance procedures. For the wider public, a promotional campaign on GI should be set up to promote the benefits of the concept for recreation, food production, nature protection, and so on.

While an umbrella policy on EU level could set the direction, a very pro-active approach needs to be applied at lower administrative levels. Although the action groups were established to enable a link to be established and utilised between various actors from both national and regional levels, this study has shown that this approach may not be sufficient to create the desired policy impacts. More incentives regarding both time and resources are needed to develop joint understanding of the term and to create tangible results at a local level, with both elements being pre-conditions for targeted and efficient approaches for the transposition and implementation of the GI concept in multi-level governance settings.

Geolocation information

Europe, Alpine area, Alpine countries: France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Liechtenstein.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naja Marot

Naja Marot is an Associate Professor who holds a PhD in urban and spatial planning. She is employed at the Department of Landscape Architecture at the Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, where she teaches tourism and recreation and regional planning at the MSc study programme of Landscape Architecture. In the field of research, she deals with urban tourism, regional planning, policy analysis and Territorial Impact Assessment. She has been working in the area of Alpine territory for almost 15 years, focusing on topics such as demographic change, policy making, provision of services of general interest, quality of life, and territorial governance.

Barbara Kostanjšek

Barbara Kostanjšek is Researcher and PhD fellow at the Department of Landscape Architecture, Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana. Her fields of work are Landscape Typology, Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA), Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Services of General Interest. In particular, she is focused on Landscape Elements, their function and their capacity for provision of ecosystem services. Voluntarily worked as the President of Slovenian Association of Landscape Architects (2020–2021) and as Delegate for International Association of Landscape Architects (2022–2023).

Nadja Penko Seidl

Nadja Penko Seidl is an Assistant professor who graduated at the University of Ljubljana, Biotechnical Faculty in 2015 with the thesis researching the role of toponymy in defining landscape character and its applicability in planning and management processes. Her teaching at the Department of Landscape Architecture and some other faculties is focused on landscape evaluation, character assessment and management, she also participates in planning theory course. Her research work addresses several aspects of landscape, mainly its character, identity and the impact of policies on its development. Recently, her research work focuses also on strategic levels of ecological connectivity and green infrastructure planning. She is the school’s representative in ECLAS – European Council of Landscape Architecture Schools.

Joern Harfst

Jörn Harfst is a research associate at the Institute of Geography and Regional Science at the University of Graz (Austria) since 2012. He holds a PhD from the University of Hannover (Germany) and has studied both at the Universities of Hamburg (Germany) and Southampton (UK). He has a long professional track-record in project management and European cooperation initiatives, also in his previous employment at the Leibniz-Institute of Ecological Urban and Regional Development (Germany). His research interests are regional development, governance, and European cohesion. In this context, he has published extensively on the topic of structural change in industrial regions of Europe. He is a member of the Regional Studies Association.

Notes

1 Despite the policy typology being versatile, not every country has implemented either new governance measures or new structures. France, for example, has established national and regional committees for GI governance, whereas Italy has implemented a competent regulatory support, while Slovenia and Switzerland rely on state or cantonal governance (CH) or spatial planning instruments (SI).

References

- AC. (1991). CONVENTION on the protection of the Alps (Alpine Convention). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/convention/1996/191/oj (Accessed September 2020).

- Ahern, J. (2007). Green infrastructure for cities: The spatial dimension. In V. Novotny, & P. Brown (Eds.), Cities of the future towards integrated sustainable water and landscape management (pp. 267–283). IWA Publishing.

- Amati, M., & Taylor, L. (2010). From green belts to green infrastructure. Planning Practice & Research, 25(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697451003740122

- Balsiger, J. (2016). The European Union strategy for the Alpine Region. In S. Gänzle, & K. Kern (Eds.), A ‘macro-regional’ Europe in the making (pp. 189–213). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Belloni, R. (2020). Assessing the rise of macro-regionalism in Europe: the EU Strategy for the Adriatic and Ionian Region (EUSAIR). Journal of International Relations and Development, 23(4), 814–839. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41268-019-00170-y

- Benedict, M., & McMahon, E. (2002). Green infrastructure: Smart conservation for the 21st century. Renewable Resources Journal, 20(3), 12–17.

- Bianchi, D. G. (2016). La governance multilivello delle strategie macro-regionali dell’ue: note critiche. Scienze regionali, 15(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.3280/SCRE2016-001001

- Boehme, K., Zillmer, S., Toptsidou, M., & Holstein, F. (2015). Territorial governance and cohesion policy. Study for directorate-general for internal policies. Brussels, Spatial Foresight, 48.

- Bramanti, A., & Rosso, P. (2007). Co-operation for cross-border competition. Euregio, Facts and Ideas of Cooperation between Adriatic and Danube, 2, 26–42.

- Connop, S., Vandergert, P., Eisenberg, B., Collier, M. J., Nash, C., Clough, J., & Newport, D. (2016). Renaturing cities using a regionally-focused biodiversity-led multifunctional benefits approach to urban green infrastructure. Environmental Science & Policy, 62, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.01.013

- Cotella, G. (2020). How Europe hits home? The impact of European Union policies on territorial governance and spatial planning. Géocarrefour, 94(94/3).

- Crowe, S. (1969). Landscape planning: A policy for an overcrowded world. IUCN. https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/6264.

- Del Biaggio, C. (2015). Investigating regional identities within the pan-Alpine governance system: The presence or absence of identification with a “community of problems” among local political actors. Environmental Science & Policy, 49, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.08.008

- Dramstad, W. E., Olson, J. D., & Forman, R. T. T. (1996). Landscape ecology principles in landscape architecture and land-use planning. Washington, Island press.

- ESPON. (2018). GRETA – “Green infrastructure: Enhancing biodiversity and ecosystem services for territorial development”. Alpine Macroregion. Version 15/11/2018. ESPON.

- European Commission. (2011). Our life insurance, our natural capital: an EU biodiversity strategy to 2020 (COM/2011/0244 final). Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52011DC0244&from=EN (Accessed September 2019).

- European Commission. (2013). Green Infrastructure (GI) — Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital. Brussels. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A52013DC0249 (Accessed May 2019).

- European Commission. (2017). What is an EU macro-regional strategy? Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/cooperate/macro_region_strategy/pdf/mrs_factsheet_en.pdf (Accessed March 2022).

- European Commission. (2020). EU biodiversity strategy for 2030. Bringing nature back into our lives. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1590574123338&uri=CELEX:52020DC0380 (Accessed September 2020).

- EUSALP. (2017). Alpine green infrastructure – Joining forces for nature, people and the economy. Joint Declaration of Alpine States and Regions.

- Fabos, J. G. (2004). Greenway planning in the United States: its origins and recent case studies. Landscape and Urban Planning, 68(2-3), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.07.003

- Faludi, A. (2012). Multi-level (territorial) governance: Three criticisms. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677578

- Gänzle, S. (2017). Macro-regional strategies of the European Union (EU) and experimentalist design of multi-level governance: the case of the EU strategy for the Danube region. Regional & Federal Studies, 27(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2016.1270271

- Gerlak, A. K., Elder, A., Pavao-Zuckerman, M., Zuniga-Teran, A., & Sanderford, A. R. (2021). Environmental justice implications of siting criteria in urban green infrastructure planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 665–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2021.1945916

- Ghermandi, A., Ding, H., & Nunes, P. A. (2013). The social dimension of biodiversity policy in the European Union: Valuing the benefits to vulnerable communities. Environmental Science & Policy, 33, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2013.06.004

- Gløersen, E., Balsiger, J., Cugusi, B., & Debarbieux, B. (2019). The role of environmental issues in the adoption processes of European Union macro-regional strategies. Environmental Science & Policy, 97, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.04.002

- Gløersen, E., Corbineau, C., & Cugusi, B. (2016). Expected benefits of transnational cooperation in macroregions in the environmental field. Archive ouverte UNIGE.

- Gobster, P. H. (1995). Perception and use of a metropolitan greenway system for recreation. Landscape and Urban Planning, 33(1-3), 401–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-2046(94)02031-A

- Grabowski, Z. J., McPhearson, T., Matsler, A. M., Groffman, P., & Pickett, S. T. (2022). What is green infrastructure? A study of definitions in US city planning. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 20(3), 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2445

- Hansen, R., van Lierop, M., Rolf, W., et al. (2021). Using green infrastructure to stimulate discourse with and for planning practice: experiences with fuzzy concepts from a pan-European, a national and a local perspective. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 3(3), 257–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-021-00087-2

- Hayes, S. J., & Dockerill, B. (2023). A park for the people: examining the creation and refurbishment of a public park. Landscape Research, 488–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1832452

- Hoover, F. A., Meerow, S., Grabowski, Z. J., & McPhearson, T. (2021). Environmental justice implications of siting criteria in urban green infrastructure planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 665–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2021.1945916

- Jerome, G. (2017). Defining community-scale green infrastructure. Landscape Research, 42(2), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1229463

- Lennon, M. (2015). Green infrastructure and planning policy: A critical assessment. Local Environment, 20(8), 957–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.880411

- Lennon, M., Scott, M., Collier, M., & Foley, K. (2017). The emergence of green infrastructure as promoting the centralisation of a landscape perspective in spatial planning—The case of Ireland. Landscape Research, 42(2), 146–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1229460

- Lidström, A. (2007). Territorial governance in transition. Regional & Federal Studies, 17(4), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560701691896

- Liquete, C., Kleeschulte, S., Dige, G., Maes, J., Grizzetti, B., Olah, B., & Zulian, G. (2015). Mapping green infrastructure based on ecosystem services and ecological networks: A Pan-European case study. Environmental Science & Policy, 54, 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.07.009

- LLausàs, A., & Roe, M. (2012). Green infrastructure planning: Cross-national analysis between the North East of England (UK) and Catalonia (Spain). European Planning Studies, 20(4), 641–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.665032

- Marks, G. (1993). Structural policy and multilevel governance in the EC. The State of the European Community, 2, 391–410.

- Marot, N., Penko Seidl, N., Kostanjšek, B., & Harfst, J. (2019 – unpublished). Study on the green infrastructure and ecological connectivity governance in the EUSALP area. Biotechnical Faculty.

- MEA (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Current state and trends, Vol. 1. Island Press.

- Mell, I. (2016). Global green infrastructure: Lessons for successful policy-making, investment and management. Routledge.

- Mell, I. (2021). ‘But who’s going to pay for it?’ Contemporary approaches to green infrastructure financing, development and governance in London, UK. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 628–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908x.2021.1931064

- Mertens, E., Stiles, R., & Karadeniz, N. (2022). Green may be nice, but infrastructure is necessary. Land, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11010089

- Meyer, C. (2020). Reinforcing comparative monitoring of Smart Specialisation performance across European regions: Transnational RIS3 observatory model as a tool for Smart Specialisation governance. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 8(2), 1386.

- Monteiro, R., Ferreira, J. C., & Antunes, P. (2022). Green infrastructure planning principles: Identification of priorities using analytic hierarchy process. Sustainability, 14), https://doi.org/10.3390/su14095170

- OECD. (2001). OECD Territorial Outlook (2001 Edition).

- Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention. (2017). Greening the economy in the alpine region: Report on the state of the Alps. Permanent Secretariat of the Alpine Convention.

- Perrin, M., Bertrand, N., & Vanpeene, S. (2022). Ecological connectivity in spatial planning: From the EU framework to its territorial implementation in the French context. Environmental Science & Policy, 129, 118–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.12.011

- Plangger, M. (2019). Exploring the role of territorial actors in cross-border regions. Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(2), 156–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1336938

- Roggeri, A. (2015). Could macro-regional strategies be more successful? European Structural & Investment Funds Journal, 3(3), 1–11.

- Rouse, D. C., & Bunster-Ossa, F. (2013). Green infrastructure: A landscape approach. Chicago, American Planning Association.

- Schubert, P., Nils, G. A., Ekelund, N. G. A., Beery, T. H., Wamsler, C., Jönsson, K. I., Roth, A., Stålhammar, S., Bramryd, T., Johansson, M., & Palo, T. (2018). Implementation of the ecosystem services approach in Swedish municipal planning. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 20(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2017.1396206

- Sielker, F. (2016). New approaches in European governance? Perspectives of stakeholders in the Danube macro-region. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1116957

- Solly, A., & Berisha, E. (2021). Towards the territorialisation of EU Cohesion Policy? The case of EUSAIR. In Governing territorial development in the Western Balkans: Challenges and prospects of regional cooperation (pp. 333–355). Springer International Publishing.

- Staccione, A., Candiago, S., & Mysiak, J. (2022). Mapping a green infrastructure network: A framework for spatial connectivity applied in Northern Italy. Environmental Science & Policy, 131, 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.01.017

- Stead, D. (2014). The rise of territorial governance in European policy. European Planning Studies, 22(7), 1368–1383. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.786684

- Stead, D., Sielker, F., & Chilla, T. (2016). Macro-regional strategies: Agents of Europeanization and rescaling? In S. Gänzle, & K. Kern (Eds.), A ‘macro-regional’ Europe in the making. Palgrave studies in European Union Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stephenson, P. (2013). Twenty years of multi-level governance: ‘Where does it come from? What is it? Where is it going?’. Journal of European Public Policy, 20(6), 817–837. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781818

- Stocchiero, A. (2015). Macro-regional strategies and the rescaling of the EU external geopolitics. In Neighbourhood policy and the construction of the European external borders (pp. 155–177). Springer.

- Svadlenak-Gomez, S. F., Gerritsmann, H., Badura, M., & Walzer, C. (2014). The EU biodiversity policy landscape. Existing policies and their perceived relevance and impact in key sectors in the Alpine Region. greenAlps project.

- Taylor, P. D., Fahrig, L., Henein, K., & Merriam, G. (1993). Connectivity is a vital element of landscape structure. Oikos, 68(3), 571–573. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544927

- Teston, F., & Bramanti, A. (2018). EUSALP and the challenge of multi-level governance policies in the Alps. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 10(2), 140–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-12-2017-0079

- Travaline, K., Montalto, F., & Hunold, C. (2015). Deliberative policy analysis and policy-making in urban stormwater management. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 17(5), 691–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1026593

- Well, L. V., & Schmitt, P. (2015). Understanding territorial governance: Conceptual and practical implications. Europa Regional, 21(4), 209–221.

- Willems, J. J., Kenyon, A. V., Sharp, L., & Molenveld, A. (2021). How actors are (dis)integrating policy agendas for multi-functional blue and green infrastructure projects on the ground. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 23(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2020.1798750

- Wright, H. (2011). Understanding green infrastructure: The development of a contested concept in England. Local Environment, 16(10), 1003–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.631993

- Zmelik, K., Schindler, S., & Wrbka, T. (2011). The European Green Belt: International collaboration in biodiversity research and nature conservation along the former Iron Curtain. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 24(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2011.592075

- Žak, J., Vaniček, V., & Elliot, H. F. I. (1971). Landscape planning. Papers presented at the international symposium on the relationship between engineering and biology in improving cultural landscape (Let. 1971). IUCN and Brno University of agriculture. https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/NS-SP-030.pdf.