ABSTRACT

This article explores a novel way to understand the process of diasporic identity formation by comparing the discursive structure of Italian diasporic newspapers published in the United States with the baseline of public discourse in Italy. It uses as its evidence Italian language newspapers published in the United States from 1898 to 1920 (ChroniclItaly) and the Italian newspaper La Stampa published in Italy between 1867 and 1900. Applying a mixed-method approach of close and distant reading, the study examines how the ideological concept of Italian identity, linguistically represented by the anchor word italianità, “Italianness”, was constructed in these printed media at the turn of the twentieth century. The overarching aim is to explore how differences in the two identity constructions can be explained from their specific historical contexts: the process of ethnic integration and redefinition in the United States as opposed to the need to consolidate national unity in the face of emerging nations and nationalism within Europe.

Introduction

This article explores a novel way to study the process of identity formation within Italian diasporic communities in the United States by comparing the discursive structure of Italian ethnic media with the baseline of public discourse in the home country. Methodologically, the study combines the distant reading lens of digital humanities (DH) methods such as text mining and semantic modeling with the close reading refinement of the discourse-historical approach (DHA – Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001). With this mixed-method approach, we aim to analyze how the ideological concept of Italian identity, linguistically represented by the anchor word italianità, “Italianness”, was constructed in printed media in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century in comparison to the discursive practice in Italy. For the analysis of the two communities’ discursive constructions of Italianness, the study compares a corpus of digitized Italian ethnic newspapers published in the United States between 1898 and 1920 (i.e., ChroniclItaly – Viola, Citation2018) with issues of the newspaper La Stampa printed in Italy between 1867 and 1900 as baseline. This comparative methodology allowed us to triangulate large amounts of linguistic, social, and historical data to address the central question whether the media construction of Italian identity depended on allegedly innate ethnic and cultural features or rather, on pressing social and economic factors surrounding these communities.

By exploring Italian identity as a use case, the study significantly expands on previous work on the transatlantic migration of Italians. A large body of literature discusses the opposing forces of disruptive uprooting (Handlin, Citation1990) and ethnic memory (Orsi, Citation2010; Vecoli, Citation1964), placing the Italian immigrant experience between the forces of longing and assimilation. Italian immigrants are seen as “Atlantians” who were “no longer ‘Italian’ and not yet ‘American’” (Carravetta, Citation2017, p. 136, 2018, p. 143). We especially build on studies that interpreted ethnicity as “a process of construction or invention which incorporates, adapts, and amplifies preexisting communal solidarities, cultural attributes, and historical memories” (Conzen & Gerber, Morawska, Pozzetta & Vecoli, Citation1992). Although the role of ethnic media has been studied from the perspective of Americanization and assimilation (Park, Citation1922), diasporic media have also been described as an umbilical cord that connects immigrant communities with the language and heritage of their homeland (Hickerson & Gustafson, Citation2016). Vellon (2017) delved into the important role played by Italian language newspapers in New York City between 1886 and 1920 in constructing concepts of race, class, and identity with respect to Italians. He concluded that it was the insistence on self-representing Italians as a civilized race in the press that built, shaped, and established an identity as Italian, American, and white (ibid., p. 4). We take this argument a step further by analyzing two narratives in contrast. The innovation this article brings lies in adding a comparative and historical dimension to the investigation of the relationship between identity construction and discursive practices in the media. Moreover, the availability of big data repositories of historical newspapers allows us to obtain a more comprehensive approach to the study of identity formation.

Italian identity, campanilismo, and whiteness

The Italian immigrant experience has to be understood against the context of identity formation in Italy (Lanaro, Citation1988; Gabaccia, Citation2003, pp. 35–57). In the aftermath of the political unification of Italy, the concepts of Italian identity and Italian national character remained vacant abstractions that held little relevance and could mean very different things for the citizens of the new nation (Bollati, Citation2011; Patriarca, Citation2010). When Italy became a unified country in 1861, it remained a deeply divided nation, politically, culturally, economically, and linguistically. Even many years after the unification, Italy struggled to achieve a true sense of national identity and one might argue that this complex fragmentation is in fact yet to be fully bridged (Patriarca, Citation2010; Viola, Citation2019). Profound cultural differences existed not only between North and South, but also from region to region. Even within regions it was not uncommon to find conflicts and cultural schisms. Such deep divisions between and within communities mainly resulted from allegiance to one’s native land. The term campanilismo – after the Italian word for bell tower campanile – is often used to describe such strong attachment to values, traditions, and dialect of the hometown. As typically the highest and most representative building in any town or village, the campanile also came to symbolize Italians’ devotion to a region, city, town, or even a village. Paradoxically, the unification of Italy had exacerbated – rather than resolved – these rivalries. Massimo D’Azeglio, Prime Minister of Sardinia from 1849 to 1852, famously described the challenge of establishing national identity after the Italian unification: “We have made Italy. Now we must make Italians.”Footnote1

During the Risorgimento, the political, ideological, and literary movement that paved the way for the unification of Italy, the unification had been presented as a liberation movement from foreign domination as well as the guarantee for prosperity for everyone (see for instance Forlenza & Thomassen, Citation2017). This was not the case, however. After the unification, the already dramatic economic situation of the South of Italy considerably worsened. This was due to a disproportional tax system imposed to the southern provinces that completely paralyzed their already stagnating economy and enlarged the economic gap between North and South. The rapid impoverishment of the southern regions after unification caused the first mass migration movements to the New World, which in turn further impoverished the South, economically and culturally (Patriarca, Citation2010, p. 67–69).

This “patchwork of Italianness” had consequences for the transatlantic migration since immigrants in this period hardly thought of themselves as Italians but would identify themselves rather in regional, provincial, or even more local terms (Carravetta, Citation2017, Citation2018, p. 134). Furthermore, because many had left Italy as a result of chain migration, they would settle in the vicinity of relatives and friends in the United States, which created self-segregated neighborhoods clustered according to the different hometowns (Macdonald & Macdonald, Citation1964). Also the organizational, social, and religious life of the Italian immigrants in the host country reflected their personal and subnational identifications; in replicating the homeland fragmentation, the concept of being Italian remained contested.

The already uncertain identity of immigrants from southern Italy was further destabilized by the fact that they were considered inferior, not only by Northern Italians who believed them to be savages and barbarians and often marked them as “Turks” or “Africans”, but also by other ethnic groups and Americans. This was partly a result of their darker skin and partly of the economic challenges of southern Italian regions. The common prejudice depicted them as lazy, backward, violent, and inclined to criminal activities (LaGumina, Citation2018; Luconi, Citation2003). This bias was so strong that in 1905 the U.S. government’s classification of Italians based on the Dillingham Commission – the U.S. Congressional commission responsible for investigating immigration – was modified in order to define Italians as two distinct peoples: Northern Italians and Southern Italians, the latter described as a “long-headed, dark, ‘Mediterranean’ race of short stature” (Immigration Commission, 1911, vol. 5, p. 82; Vellon, Citation2018).

The Dillingham Commission’s segmentation of Italians shows how the mass migrations to the United States had caused a redefinition of social and racial categories. Categories of distinction such as race, civilization, superiority, and skin color had blended into each other, creating the binary opposition of white/superior vs non-white/inferior (Vellon, 2017, p. 4). The whiteness category itself, however, was far from comprehensive or exclusively based on skin color. Jacobson (Citation1998) for instance, explained how mass immigration in the United States was characterized by a revaluation of a very rigid notion of whiteness; at the turn of the twentieth century, he argues, whiteness became “a system of ‘difference’ by which one might be both white and racially distinct from other whites” (ibid., p. 6). Indeed, during this period, immigrants’ “races” were appraised and privileged differently depending not on how white they were, but rather on how white they were perceived. As Foley put it, “[n]ot all whites […] were equally white (Foley, Citation1997, p. 5). Many other authors have described this unstable racial situation of immigrants in the United States as “conditionally white” (Brodkin, Citation1998), “situationally white” (Roediger, Citation2005), and “inbetweeners” (among others Barrett & Roediger, Citation1997; Guglielmo, Citation2004; Guglielmo & Salerno, Citation2003; Orsi, Citation1992). This was the case for immigrants from Southern Italy whose search for an identity and racial status was problematic in many ways; on the one hand, they were “white enough” to enter the country, but on the other, they were not quite “white enough” to be fully accepted within the American society. For example, in addition to restrictions in employment and housing, Italian immigrants would often be victims of social discrimination, exploitation, physical violence, and even lynching (Connell & Gardaphé, Citation2010; LaGumina, Citation1999, Citation2018).

The process of national identity formation in Italy itself was radically different from the social experience of Italian immigrants in American society; while the former group was going through a process of cultural appropriation of a shared notion of nationhood, the latter was negotiating social inclusion within American shifting categories of citizenship and whiteness. This article uses the lens of discursive practices in public media to understand to what extent such dissimilar external factors influenced the construction of Italian identity, italianità.

The Italian press in the United States, 1880–1920

It is estimated that more than 4 million Italians migrated to the United States between 1880 and 1920. As immigrant communities grew larger and larger, the immigrant press boomed accordingly; 98 Italian newspapers published uninterruptedly during this period in the United States, with an estimated additional 150 to 264 titles that appeared and disappeared at different times (Deschamps, Citation2011, p. 81). Their circulation ranged from few hundreds to many thousands (Vecoli, Citation1998); in 1900, 691,353 Italian newspapers were sold across the United States (Park, Citation1922, p. 304) but in New York alone, the circulation ratio of the Italian daily press was one paper for every 3.3 Italian New Yorkers (Vellon, op. cit., p. 10). Moreover, because illiteracy was still high, newspapers were often read aloud, thus doubling or tripling their reach. Distribution and circulation figures would indicate that the Italian language press exerted an influential role both on the immigrant community and within the wider American context. However, some scholars (e.g., Vecoli, Citation1993, Citation1998) have argued that the influence of the Italian press was in fact limited. According to this view, Italian immigrants’ minds were not some sort of empty container in which the press could impose its definition of social reality; “Rather, they [Italian immigrants] filtered media messages through the sieve of their own experience. Finally, they decided what was reality – and its meaning” (Vecoli, Citation1998, p. 28, emphasis in the original). Either way, it is undisputable that Italian newspapers helped immigrants cope with life in the New World, including easing their transition into American society. Despite their ideological, religious, or commercial motivations, the ethnic press would, for example, provide immigrants with news from their home country as well as issues related to American life, including crimes, practical and social matters such as employment listings, announcements of neighborhood events, dinner dances, meetings, or religious celebrations (Vellon, op. cit., p. 31). Because they were mostly published in Italian, diasporic newspapers also served as powerful tools of language retention and, particularly in the case of mainstream publications, also of national identity construction and preservation. Acting as champions of the rights of the respective immigrant communities, they functioned as their representatives to the larger society (Rhodes, Citation2010, p. 85). Ethnic media are an important source that enables historians to reconstruct the often conflicting worldviews of this “silent crowd of misunderstood and maligned individuals on opposing shores of the Ocean sea called the Atlantic” (Carravetta, Citation2017, p. 139, 2018, p. 145).

The Italian publications of the years 1880–1920 can be divided into two main categories: prominenti and sovversivi. The prominenti were prominent figures of the Italian American community; moderately educated individuals from a low-middle class background and with no journalistic expertise. For this reason, the journalistic quality of the prominenti publications was overall rather low. The editorial format would normally include collages of translated American news, clippings of news imported from Italian newspapers, a considerable number of ads, and columns about social life in the New World, such as festivals, parties, and gossip. Because of their constant commercial struggles, the political allegiance of these newspapers usually mirrored the orientation of their main financial supporters at a given time (Vecoli, Citation1998, p. 21). Low quality and flawed grammar, however, did not matter to a community whose the average members hardly mastered Italian – let alone English. On the contrary, offering information in a language their readership could at least to an extent understand created a bond of trust between the newspapers and the immigrants, thus making the Italian language press an essential element in the many stages of immigrant life (Rhodes, Citation2010, p. 48). Conversely, this educational role within the Italian community empowered the Italian ethnic press to become an organ of social control, defined as “a mechanism through which the community acts” (Park, Citation1922, p. 330).

Like all media, Italian language newspapers performed social control by articulating what was acceptable and not acceptable not only within the Italian immigrant community, but also within the dominant norms and values of the American society. For example, prominenti newspapers often supported nationalistic campaigns such as the erection of statues of influential Italians (e.g., Dante, Garibaldi, Cristoforo Colombo), pleas for convicted Italians, fundraisings for natural disasters in Italy, and voicing protests against mistreatments of Italians. At the same time, they censured any disrespectful behavior by Italians, such as begging or English illiteracy, that could have humiliated the whole community. Scholars have contrasting opinions about the role of the prominenti newspapers. Pozzetta (Citation1973) and Vecoli (Citation1998), for example, agree on the fact that, because they often represented the interests of their owners, these publications in fact damaged Italian immigrants.

These diasporic media also reframed immigrant memories of their home country, thus subtly renegotiating their cultural affiliation. It has been argued (i.e., Deschamps, Citation2011, p. 82), for instance that the Italian immigrant press initially started to fabricate the notion of a unitary identity so that newspapers could reach a larger audience and survive in a very competitive market. Therefore, pure economic reasons may have induced newspapers to exalt Italian values and italianità while fighting against campanilismo. Grillo (Citation1962) and Briggs (Citation1978), whilst admitting that prominenti were exploiting the immigrants’ vulnerability to their own benefit, underlined that Italian ethnic newspapers helped their readers adjust to the new society by encouraging them to aspire to bourgeois status while respecting the United States. Even if the exaltation of a national identity may have not always been sincere, the celebration of italianità facilitated the construction of a shared national identity, helped Italian immigrants overcome cultural divisions, and provided the Italian community with greater visibility. As Vellon put it: “Rather than retard immigrant acculturation, uplifting the race afforded Italians a platform from which to proudly argue for their full inclusion in American society as Italian, American, and white” (op. cit., p. 35).

The sovversivi were radical publications of socialist and anarchic background. Their circulation was overall limited in comparison to the prominenti; because they were mainly financed through fundraising, these newspapers faced constant economic struggles and often lasted only a few issues. Yet, between 1880 and 1920, there were 190 Italian radical publications in the United States, making the sovversivi the second non-English radical newspapers (Russo, Citation1972). The editors of these publications were often political refugees, such as Luigi Galleani, who could keep circulating their ideas through the newspapers, not only in the United States but also back in Italy. Although the sovversivi were grounded in radical theoretical discussions, they were also trying to accomplish the social mission of educating the Italian community by spreading theoretical and scientific works as well as more practical news such as reporting on labor conditions and strikes. In their fight against capitalism, they also passionately opposed the prominenti press for their exaltation of hegemony, Italian patriotism, and American nationalism.

The struggle between the two camps was put to an end by World War I. Although the radicals were ideologically divided between interventionists and noninterventionists, eventually nationalism prevailed over transnationalism. Moreover, in those years the Italian radical press was firmly suppressed by the American government and most of their editors like Luigi Galleani were arrested and deported (Vecoli, Citation1998). At the same time, the prominenti press became the ideal medium for governmental propaganda, thus reaching its peak of circulation. Although it remains practically impossible to establish to what extent the radical press contributed to the construction of Italian identity in the United States, it is still important to include these publications in any study concerning the Italian immigrants of this period as it is certain that this counter-culture was a substantial component of the Italian community.

Methodology and sources

This study compares how the discursive construction of italianità, Italianness, was shaped by the press in two Italian communities: the Italians in the newly formed Italy and the Italian immigrants in the United States. The analysis combines two approaches: a digital humanities (DH) analysis and a discourse-historical analysis (DHA). The combination of the two approaches will provide a rich picture of the relationship between discourse practices, latent ideologies, and respective fields of action.

Digital humanities analysis

The data are first processed with AntConc 3.5.6 (Anthony, Citation2018) and concordances lists are computed for identified salient words. This allows us to assess the semantic distributions in each corpus. These results are visualized as semantic clouds using the Wordcloud tool (http://wordcloud.cs.arizona.edu). Wordcloud is preferred to other similar tools (e.g., Wordle, Viegas, Wattenberg, & Feinberg, Citation2009) because, by taking into account not only word frequency but also semantic similarities, it can visualize several dimensions of relationships between the words. Using Cosine Similarity, Jaccard Similarity, and Lexical Similarity as the similarity functions (Graeme & St-onge, Citation1998; Guha, Rastogi, & Shim, Citation2000; Xu & Wunsch, Citation2005), Wordcloud calculates a matrix of pairwise similarities in word lists in which related words receive high similarity values. The words are then ranked according to their frequency in the input text, subsequently clustered based on their semantic meaning, and finally identified by different colors (i.e., semantically related groups of words are likely to have the same coloring), as well as distance and size. In this way, the main topics in a text and the relationships between words can be visually and promptly identified. To identify the clusters, Wordcloud employs the modularity-based algorithm (Newman, Citation2006).

The DH analysis is crucial to the main research hypothesis of this study as it is based on the semantic theory of language usage (Harris, Citation1954, p. 156) according to which words that are used and occur in the same contexts tend to purport similar meanings. This distributional hypothesis is still the core of most Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques and has been applied to computational word vector models, as for instance in the word2vec algorithm of Google. If the meaning of a word can be inferred by its context, the opposite is true as well; therefore, if the analyzed keywords are found in different contexts, then they purport different meanings. The results will in this way provide us with insights on the discursive structure of the two data-sets, including linguistic and conceptual differences relevant for the DHA analysis.

Discourse-historical analysis

For the qualitative analysis of the textual data, we use the discourse-historical approach (DHA – Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001). This approach employs a pragmatic perspective to the theory of critical discourse analysis (van Dijk, Citation1993). Rather than offering generic conceptualizations, it advocates a thorough examination of the context of the specific problems investigated. Practically, the method triangulates linguistic, social, and historical data with the aim of understanding language use – as manifested in the different semantic distribution of the salient words analyzed here – in its full socio-historical context and as a reflection of its cultural values and political ideologies. The method is particularly well suited for this study due to the use of historical data. Moreover, the principle of triangulation minimizes the risk of biases when performing the critical analysis (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001, p. 65).

Sources

For the investigation, two digital resources have been used: ChroniclItalyFootnote2 (Viola, Citation2018) and La Stampa (http://www.lastampa.it/archivio-storico/index.jpp). ChroniclItaly collects all front pages of seven Italian language newspapers published between 1898 and 1920 in California, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Vermont, and West Virginia. The corpus, which was extracted from the Chronicling America newspaper collection of the Library of Congress, includes 4,810 issues and for a total of 16,624,571 words. Featuring both prominenti and sovversivi newspapers, ChroniclItaly is a well-balanced resource for the study of the Italian immigrant press of the time. Moreover, because it is entirely digital, this corpus is a powerful tool for conducting text-based searches and analysis, both quantitative and qualitative. The newspapers’ titles are: L’Italia, Cronaca sovversiva, La libera parola, The patriot, La ragione, La rassegna, and La sentinella del West Virginia.

L’Italia was founded in 1886 by a group of Italian prominenti who, under the name of Lega dei Mille (League of the Thousand), formed the Società Editrice Italiana (Italian Publishing Company), purchased two failing papers and fused them into L’Italia. Initially, the newspaper was published bi-weekly, but by 1889, it was published on a daily basis. In 1895, the editor-in-chief of L’Italia was Pio Morbio, co-founder of Il Corriere della Sera, one of the main newspapers in Italy at the time, while in 1897, Ettore Patrizi and Giovanni Almagia became first co-editors, and later owners of the newspaper. For about two decades, under Patrizi’s lead, L’Italia voiced a leftist ideology, close to the Italian labor class, and defended Italians against defamation and discrimination. However, after 1909, Patrizi overtly embraced Mussolini’s ideology and the newspaper’s orientation became ardently nationalistic.

Cronaca sovversiva was founded by the anarchist Luigi Galleani in 1903. He had arrived in the United States a few years before to escape extradition and had settled in Barre, Vermont, where an Italian community of stonemasons was living. Galleani published the anarchist newsletter for fifteen years until the United States government forced him to stop under the Sedition Act of 1918. Each issue of Cronaca Sovversiva typically discussed a variety of radical topics, including arguments against the existence of God and against historical and contemporary establishment. It also often published a list of addresses of reputed “enemies of the people” such as businessmen and opponents of strikes. Several books attributed to Galleani, such as La Fine dell’ anarchismo? (The End of Anarchism?, 1907) include excerpts from essays that first appeared in Cronaca Sovversiva.

La Libera Parola – which was originally called La Voce del Popolo – was founded in 1906 in Philadelphia when the two brothers Arpino and Giovanni Di Silvestro merged Il Popolo and La Voce della Colonia. It was a weekly newspaper which publicized the activities of the Pennsylvania Chapter of the Order of the Sons of Italy and overall echoed the same nationalistic sentiments felt in Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century. The newspaper also later chronicled the involvement of Italy and the United States in World War I and published articles about the 1917 Russian Revolution, as well as the socialist movement in Europe in general. La Libera Parola supported Italy’s participation in the war and criticized Pope Benedict XV for opposing Italy’s involvement in the conflict. The paper also encouraged Italian-Americans to become American citizens, enlist in the military, and buy Liberty Bonds to help finance the Allied war effort. The newspaper had a central role during the presidential election of 1920 when it explicitly encouraged its readers to support the Republican candidate. This was done as a form of revenge against President Woodrow Wilson due to his role in nullifying the Treaty of London agreements at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. According to this agreement, Italy had been promised Dalmatia in exchange for declaring war on Austria-Hungary and Germany. Compared to the votes that Wilson had received in 1916 from the Italian American community of Philadelphia, the Democratic presidential candidate received 10 percent less. La Libera Parola discontinued its publication in 1969.

The Patriot was founded in Indiana, Pennsylvania by Francesco Biamonte in 1914. Biamonte was originally from Calabria but he had graduated from Johnstown’s business college before moving to Indiana to work in a bank. He had founded The Patriot as a politically independent newspaper to inform Italians in the region and to offer immigrants advice on adjusting to American life. The Patriot featured four pages in English followed by four in Italian. In later years, the number of pages in Italian was reduced to one. The newspaper encouraged Italians to become naturalized citizens and it permanently featured a column listing questions probably taken from the citizenship test. The Patriot was liquidated after Biamonte’s death in 1955.

Founded in 1917, La Ragione survived only eight editions between 25 April and 23 August 1917. It was published in Philadelphia and its main aim was to expose corrupted personalities within the Italian community such as prominenti and dishonest bankers. La Rassegna was also a short-lived newspaper published in Philadelphia in 1917. It was written mostly in Italian and focused on issues affecting Italian immigrants in Philadelphia. In addition to editorials and articles, the paper chronicled major historical events such as World War I, the Russian Revolution, the invention of the Zeppelin, the growth of the Socialist Party in Italy, and Italy’s nationalistic claims to Dalmatia. In addition to defending prominenti, La Rassegna highlighted major cultural issues such as women’s rights, and encouraged Italian immigrants to seek naturalization.

La Sentinella del West Virginia was West Virginia’s only Italian periodical. It was founded by Rocco D. Benedetto in 1905 and by 1906, its circulation had peaked at 3,500. Although Benedetto was an active Republican, the newspaper claimed to be politically independent. The publication mainly informed immigrants about Italy, but also about their new homeland. News from the United States mostly dealt with other Italian communities, but the paper also discussed American politics and current events. This newspaper chronicles a thriving community of immigrant laborers and serves as an irreplaceable element of cultural heritage of the flourishing Italian immigrant presence in West Virginia. It ceased in 1920.

ChroniclItaly allows us to study past narratives of migration and migrants and obtain new insights on the Italian migrants’ role in the history of the United States. At the same time, this collection is an excellent research tool to study the dual historical role of the ethnic press in the United States. On the one side, ethnic newspapers functioned as nodes of knowledge transfer between the homeland and the host country’s communities, on the other, they acted as an instrument for their social and cultural integration. ChroniclItaly is available as an open access resource at https://doi.10.24416/UU01-T4YMOW.

The corpus La Stampa that we used here is a sample taken from the online digital archive (https://www.lastampa.it/archivio-storico/index.jpp). Although potentially an extremely powerful research tool, the online archive is limited in the ways it can be accessed, since only basic consultations can be conducted using the in-built search engine. For wide-scale computational analysis, search results can only be downloaded manually as bulk download is not possible. Such restrictions considerably limit the ways in which the resource can be accessed and determined specific methodological decisions. Therefore, a compromise had to be made between the resources available for NLP analysis and the need to build a corpus that could be both representative of the material published in the period of interest and relevant to this investigation. For this purpose, we restricted the download to those pages in which the word italianità appeared in the issues published between 1 January 1867 and 31 December 1900. Once the harvest was completed, our sample of La Stampa totaled up to 2,810,579 words.

The authors acknowledge the imbalance between ChroniclItaly and La Stampa. Future research could consider integrating the resources used in this study with more data, for instance including Il Secolo and Il Corriere della Sera, which, at the time, had the highest circulation in Italy. However, at the moment of writing, the digitization of Il Secolo by Florida State University Libraries has not been completed; the project is still ongoing as new issues are being added to the collection continually. Once the process will be completed, research on the archival material of Il Secolo certainly bears huge potential. Consultation of the digital archive of Il Corriere della Sera is only possible using the provided text search engine. The bulk download of the search results is restricted and therefore the archive cannot be used for computational analysis or distant reading methods. Although La Stampa did not have the highest circulation within the Italian Kingdom (45,000 copies in 1902), the collection remains a valuable source of historical material that allows researchers to access factual information during a crucial time in the history of Italy. We believe that the considerable size of the La Stampa corpus and the combination of the two methodologies largely compensates for the imbalance between the two data-sets.

Analysis and results

This section shows the results of the analysis as described in previous sections; in particular, the first section shows the results of the DH analysis while the second one analyzes excerpts from the two data-sets using DHA.

Digital humanities analysis

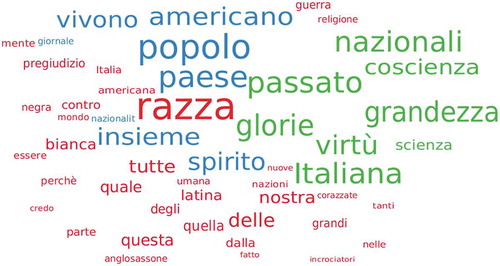

Concordance lists are computed for salient words so as to gain insights on their semantic distributions in each corpus. The identified salient words are italianità, Italia + bianco, and razza. The results are presented as semantic clouds (–); specifically, – show the word clouds from ChroniclItaly while – show the results for La Stampa. In order to normalize unwanted highly ranked words (i.e., semantically meaningless words such as prepositions, articles, conjunctions), words shorter than 4 characters, as well as numbers and other stop words are not computed. The first word cloud has been generated for the 75 most frequent words semantically associated with the term italianità in ChroniclItaly.

shows the concordances results for italianità in ChroniclItaly. The closest related words, both in terms of frequency and proximity, are: difesa (defense), dimostrazione (demonstration), grande manifestazione (great manifestation), affermazione (affirmation), patriottismo (patriotism), pura (pure), bella (beautiful), spirit (essence, soul). The presence of highly ranked words such as difesa and affermazione in relation to italianità is in line with what has been reported in literature about the role played by the Italian immigrant press in empowering the Italian immigrant community. The results show how ethnic newspapers were pushing on narratives such as the need for “defending” and vindicating a “pure” and “beautiful” Italianness, which would then become a synonym for a “pure and beautiful” race deserving to enter the American society. This argument is effectively represented in which displays the word cloud of the concordances results for the 50highest ranking words occurring in the same contexts as Italia (Italy) and bianco in ChroniclItaly.

Based on both frequency of occurrence rates and semantic proximity, bianca (white, f.) and superiore (superior) are, in the ChroniclItaly corpus, the most closely related words to Italia; in the same contexts as Italia, the words negri (negroes), carbone (coal) and razza (race) are also found. It should be noted that bianca is singular and feminine like the words Italia and razza, further highlighting their mutual semantic relation, while italiani (Italians) and superiore are both colored in blue, thus showing their use in similar semantic contexts.

The word cloud suggests a narrative in which images of Italy were constructed around the binary opposition of white/superior vs non-white/inferior, perhaps visible in the use of the word carbone (coal) which may be used in Italian as a derogatory characterization for the adjective “black” (e.g., black as coal). The results show a discursive strategy which distanced Italians from Africa and the black community while self-proclaiming white superiority. Words such as insegnamento (education) and scuola (school) remind to other cardinal concepts that constructed narratives of an Italian heritage of civilization and a glorious past of grandeur, supposedly in opposition with a “savage” Africa (i.e., negros). above illustrates this argument.

The word cloud in shows the contexts of occurrence of the word razza (race) in the ChroniclItaly corpus; the closest related words are americana (American), bianca (white, f.), Italia (Italy) and latina (Latin, f.). At the same time, the words passato (past), glorie (glories), grandezza (grandeur), virtù (virtue(s), coscienza (consciousness) are semantically associated to the word italiana (Italian, f.). By levering on a glorious past of Italian splendors and Latin heritage, the semantic distribution seems to illustrate a narrative of a civilized, white, and therefore superior Italian race. Overall, the strategy of uplifting the Italian race included destroying any connection between Italy and savagery – in those years associated with Africa, and between Italians and inferiority (Vellon, op.cit.). In order to do that, alongside images of Italian grandeurs, the Italian ethnic press often used the glory of Ancient Rome and Latin language as the most representative symbols of Italian civilization.

The word clouds (–) have shown the semantic distribution of the words italianità, Italia + bianco, and razza, in ChroniclItaly; the results indicate that these words were used and occurred in the same contexts as superiore, bianco, grande, and glorioso thus supporting the research hypothesis that in the Italian ethnic press, being Italian was constructed by resorting to a racial rhetoric and it was associated with being white, civilized, and superior. The DHA of the excerpts will provide a finer-grained picture of the narratives employed by the Italian ethnic press.

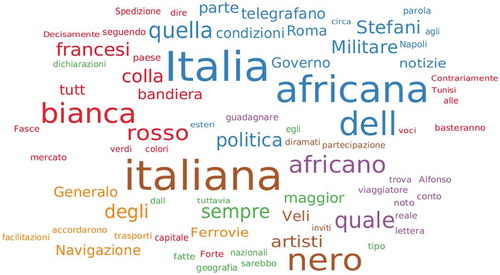

We will now move on to analyze the word clouds of La Stampa for the same keywords (–).

The word cloud in shows the results for italianità in the corpus La Stampa. The closest related words, both in terms of frequency and semantic proximity, are sentimento (feeling, sentiment), nostra (our, f.), carattere (character), spirito (spirit), profondo (profound), and nazionale (national). Words such as dimostrazione (demonstration), and grande manifestazione (great manifestation), which were frequently found in semantic proximity to italianità in ChroniclItaly, are not found in La Stampa. Moreover, difesa (defense), which was the most closely related word to italianità in ChroniclItaly, scores lower in La Stampa. At the same time, similarly to ChroniclItaly, patriottismo (patriotism), patria (homeland), affermare (to affirm), and conservazione (preservation) are retrieved while schietta (honest) is found here as opposed to pura (pure) in ChroniclItaly.

The difference in the semantic distribution of italianità in La Stampa suggests that in the Italian press, the concept of italianità was used more in relation to words like sentimento, carattere, spirito rather than as a synonym for razza superiore (superior race) and that the stress was put more on affirming (affermazione) a communal (nostra) sense (sentimento) of patriotism (patriottismo) and nationalism (nazionale). The results suggest that the Italian press, rather than employing a racial rhetoric, used the concept of italianità to construct a narrative of national unity which was certainly urgently needed in the aftermath of the Unification of Italy. This argument is also effectively represented in which displays the word cloud in La Stampa for the words Italia (Italy) in the same contexts as bianco (white).

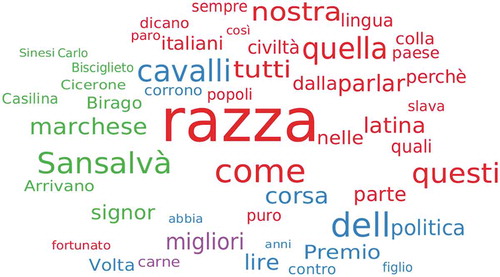

The results are radically different from those found in ChroniclItaly. Based on both frequency of occurrence rates and semantic proximity, the closest words to Italia are Africana (African, f.), Governo (Government), politica (policy), militare (military), and Roma as opposed to bianca (white, f.) and superiore (superior) found in the ChroniclItaly corpus. The word bianca is found here in relation to bandiera (flag), together with other colors (rosso “red”, verdi “green”) as well as the word colori (colors) itself. Words such as negri (negroes), carbone (coal) and razza (race) – which were found in ChroniclItaly – are missing in La Stampa. In this semantic distribution, no evidence is found of the white/superior vs non-white/inferior narrative previously observed in ChroniclItaly (cfr. ) thus revealing substantial differences between the two discursive strategies. In La Stampa, what emerges from the results is an emphasis on typical images of national identity such as the flag (bandiera) and the national colors (rosso, verde, bianco) which would suggest a wider strategy of giving priority to inspiring national cohesion and identity. shows the semantic distribution of the word razza in La Stampa. The word cloud in closest related words are cavalli (horses), corrono (run), corsa (race) and what appear to be horses names (i.e., Birago, Sansalvà, Casilina) revealing a semantic distribution significantly different from ChroniclItaly in which words such as bianca (white, f.), Italia (Italy) and latina (Latin, f.) as well as passato (past), glorie (glories), grandezza (grandeur), and virtù (virtue/s) were found instead. Here the use of the word razza – which in Italian also translates “breed” – seems to refer to horse breed rather than the human race. The semantic cloud, however, includes words such as nostra lingua (our language), civiltà (civilization), and latina (Latin); such collocations will be further analyzed in the next section.

The word clouds in – have shown the semantic distribution of the words italianità, Italia & bianco, and razza in the La Stampa corpus. The results show that these words occurred in the same contexts as sentiment (sentiment), patriottismo (patriotism), Governo (Government), bandiera (flag); such semantic distribution reveals a narrative predominantly constructed around national unity, pushing on artificial concepts such as Italian sentiment, Italian character, and Italian patriotism. The DHA in the next section will offer a finer grained picture of the different narratives in the two repositories.

Discourse-historical analysis

We analyze excerpts from the concordances lists previously generated with AntConc (Anthony, Citation2018). By integrating empirical linguistic data with the close examination of the social, political, and historical context in which the discursive “events” are embedded (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001, p. 65), the aim is to obtain a richer and more nuanced account of the narratives constructed by both the Italian ethnic press and the Italian press. This will allow us to better understand the way in which the press construction of Italianness was shaped by the two different social contexts in which the communities were embedded. The excerpts below show the contexts of occurrence of the word italianità in the two data-sets; Excerpt 1 is taken from ChroniclItaly while Excerpt 2 is taken from La Stampa (emphasis added).

(1) Io denuncio ancora una volta al giudizio degli imparziali la ingiusta campagna di denigrazione iniziata contro l’Ordine Indipendente Figli d’Italia da una schiera di facinorosi in mala fede, i quali calpestando i più santi doveri di fratellanza e d’italianità cercano, in piccole lotte personali, con raggiri e calunnie d’ogni genere, di creare la sfiducia e la diffidenza intorno ad una grande famiglia d’italiani, rispettabile sotto tutti i riguardi, per le persone che la compongono e per gli Ideali che la ispirano. (La Rassegna, 28 April 1917)

I refer once again the unfair campaign of denigration against the Order Sons of Italy in America to an impartial judgment. This campaign has been started by a bunch of rioters in bad faith who, trampling on the most sacred duties of brotherhood and Italianness and through little personal wars, tricks and lies of all sorts, try to create distrust of the great family of Italians, which is respectable in all respects, for the people that are part of it and for the Ideals that inspire it.

The excerpt above shows how the Italian ethnic press pushed forward an agenda for fighting against the negative stereotypes afflicting Italians in American society. The word italianità is used to construct the concept of a trustful, respectable, even “sacred” Italian community that was inspiring in others ideals with a capital “I”. In its plea for “impartial” judgment, the newspaper refers to the Order Sons of Italy in America (OSIA). This was the first and still is the largest Italian American fraternal organization in the United States. It was established in 1905 by Vincenzo Sellaro and five other Italian immigrants with the aim of creating a support system for all Italian immigrants to assist them with becoming U.S. citizens, provide health and death benefits, and educational opportunities, as well as offering assistance with assimilation in America. Over time, the organization became more and more influential and expanded its mission to facilitate the study of Italian language and culture in American schools and universities, preserve Italian American traditions, culture, history, and heritage, and promote closer cultural relations between the United States and Italy. The reference to the Order is significant. In the very same year, OSIA had been received for the first time by President Woodrow Wilson at the White House (Massaro, Citation2003, p. 431), thus illustrating the growing influence of the Order and indicating the institutional legitimization of the Italian immigrant community as white Americans (Vellon, op.cit., p. 31). At the same time, by publicly defending the Order, La Rassegna strategically implemented its own mission devoted to the welfare and advancement of Italians in America.

The following excerpt displays the context of italianità in La Stampa.

(2) Quando Bettino Ricasoli, correndo gli anni 1861 e 1862, nella sua corrispondenza – stupenda per alto sentimento d’italianità e per saviezza politica – con Costantino Nigra, scriveva con catoniana insistenza: «Dica all’imperatore dei francesi che il regno d’Italia è impotente per se o inutile all’Europa senza Roma sua capitale;» il grande statista, che ebbe la ventura di succedere a Camillo Cavour, affermava una solenne verità storica, di cui oggi noi godiamo i benefici effetti. In Roma non solo si è compendiata la storia nazionale, ma altresì si è affermato il nostro diritto, si è consacrata la nostra libertà. (La Stampa, 20 September 1891)

When in the years 1861 and 1862, Bettino Ricasoli in his correspondence with Costantno Nigra – wonderful for its high sentiment of Italianness and political wisdom – was writing with Catonian insistence: “Let the French Emperor know that the Italian Kingdom is powerless for itself or useless to Europe without Rome as its capital;” the great statesman, who had the fortune to succeed to Camillo Cavour, affirmed a solemn historical truth, of which today we enjoy the beneficial effects. Not only was our national history encapsulated in Rome, but also our right was established, our freedom was consecrated.

The excerpt above reveals a significantly different narrative from the one found in ChroniclItaly. Here, the use of the word italianità is strongly politicized as it is associated to Ricasoli’s sentiments of political wisdom in favor of the political unification of Italy. Bettino Ricasoli – who succeeded Cavour as Prime Minister – is described as a wise politician, particularly regarding his agenda in favor of Rome as capital of Italy. Specifically, the journalist is referring to the anniversary of the Capture of Rome on 20 September 1870, when the Papal States were defeated by the Italian army. The annexation of Rome to the Kingdom of Italy completed the unification process. Therefore, the term italianità conveys a message of national union and becomes a synonym for Italy’s rightful and sacred independence (“freedom”). As discussed above, even many years afterwards, many Italians considered the unification as a political imposition. The mainstream press, such as La Stampa, tried to defend the unification against its detractors by insisting on concepts of national unity and collective identity, and by saluting the Risorgimento as a triumphant conquest of Italy.

We will now analyze extracts from the two data-sets of the contexts in which Italia and bianco co-occurred. Excerpt 3 is taken from ChroniclItaly (emphasis added).

(3) Non solo la Compagnia dà delle paghe misere, ma assoggetta i nostri connazionali ad ogni sorta di umiliazioni e di angherie. Gli agenti della Compagna, parlando degli italiani, li denominano col vile titolo di “Dagos” e, peggio ancora, chiamano gli altri lavoratori “bianchi” facendo una flagrante insinuazione mirante ad affermare che gli Italiani, almeno questi poveri, ma buoni lavoratori di McCloud, non appartengono alla razza bianca. (L’Italia, 8 June 1909)

Not only does the Company pay the lowest salaries, but it also subjects our fellow countrymen and women to humiliations and vexations of all sorts. The Company’s agents refer to Italians with the mean insult of “dagos” and, even worse, call the other workers “white” obviously implying that Italians, at least these ones poor but honest McCloud workers, do not belong to the white race.

Excerpt 3 perfectly illustrates the precarious racial situation of Italian immigrants in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. The way the “poor but honest” Italian workers of McCloud, California were discriminated demonstrates their uncertain racial identity as they were called by the same slur used for immigrants of Latin origin. They were purposely not referred to as “white” which also reveals how the social category itself of being white was determined by a complex combination of factors, of which the skin color was just one of the many. The excerpt is also particularly relevant to our analysis of how the ethnic press was reflecting the migratory experience of the Italian community. The episode described in the article refers to the strike undertaken by Italian workers of the McCloud River Lumber Company to protest against low salaries and poor working conditions. By denouncing the racial discrimination suffered by the Italian workers of McCloud, the newspaper L’Italia appealed to other Italians as well as to the wider American society to raise money in support of the workers. In this way, the ethnic newspaper publicized what was not acceptable not only within the Italian immigrant community, but also within the dominant norms and values of the American society. The Italian ethnic identity is clearly associated with being white which demonstrates how the press insisted on constructing images of Italian whiteness to negotiate social integration.

Excerpt 4 shows the context of occurrence of Italia and bianco in La Stampa.

(4) (…) ma comprese ben tosto quale fosse il vero interesse della patria, e seguendo l’esempio di Daniele Manin e di Francesco Crispi, si strinse alla bandiera d’Italia colla croce, bianca e a quella Casa di Savoia che il voto della nazione aveva acclamato, perché simbolo incontaminato di fede, di lealtà, di valore, d’italianità! Ah, se quelli che oggi in Italia scherzano col fuoco venissero qui, comprenderebbero che cosa è costato di lacrime e di martiri l’amare questa nostra patria e che delitto sarebbe il metterne in pericolo con ideali inopportuni c con dottrine dissolventi le sorti a così caro prezzo conquistate. (La Stampa, 4 February 1896)

(…) but he very soon understood what was in Italy’s best interest and, following the examples of Daniele Manin and Francesco Crispi, he stood by the Italian flag with the white cross, and by the House of Savoy, which the nation had voted for so overwhelmingly, as a pure symbol of faith, loyalty, value, and Italianness! Ha! If those who in Italy today play with fire came here, they would understand the tears and tortures this love for our country cost and what a crime would be to jeopardize with false ideals and vain doctrines its fate at such a high price conquered.

The excerpt is taken from an article in La Stampa and it reports on the inauguration of the statue of Nicola Fabrizi in Modena. The journalist remembers the Italian patriot, one of the leaders of the Risorgimento. Here the color white is used in association with the “white cross” symbol of the House of Savoy and the Italian flag, which then together represent “faith”, “loyalty” and “Italianness” as a whole. The narrative constructed by La Stampa is therefore completely different from the one found in ChroniclItaly. While in the Italian American newspapers, these values were used to construct a racial identity of Italian whiteness, here the insistence on national values were aimed at evoking feelings of Italian pride and patriotism in the readership. Thus, being Italian meant being loyal to the values of the Risorgimento, being in favor of the political unification of Italy, and defending its leaders as national heroes.

Excerpt 5 shows the context of occurrence of razza in ChroniclItaly.

(5) “Tutto il mondo va a scuola dai Latini!” – dichiara Tom Watson – il quale afferma perfino che i due più grandi uomini che il mondo ha avuto (i quali secondo lui sarebbero Giulio Cesare e Napoleone I) furono italiani. Queste ed altre belle, giuste e nobilissime cose afferma Tom Watson nel suo Magazine per il mese di giugno. Numero che tutti gl’italiani dovrebbero acquistare e tenerselo sempre in tasca o poterlo al caso sbattere sul muso a chiunque tentasse sparlare degl’italiani e, in generale, della razza latina. Watson è stato anche coraggioso nello scrivere quest’articolo perché purtroppo anche molti dei suoi compatrioti americani assai spesso aggrediscono gl’italiani con offese ingiuste e con asserzioni stolte e bugiarde. (L’Italia, 9 June 1905)

“The whole world learns from the Latins!” – declares Tom Watson – who also affirms that even the two greatest men the world has ever known (Julius Caesar and Napoleon I, according to him) were Italian. These and other beautiful, fair, and very noble things has Tom Watson affirmed in the June issue of his magazine. Every Italian should buy this issue and keep it in their pockets to throw it in the face of whoever dared to badmouth the Italians and, in general, the Latin race. Watson was also very brave to write this article because unfortunately many of his fellow Americans often attack Italians with unfair insults and stupid and false claims.

The excerpt is a perfect example of how the Italian language press in the United States levered on a glorious past of Italian splendors and Latin heritage to push a narrative of a civilized, virtuous and therefore superior Italian race while distancing themselves from the African-American community. In this particular piece, the author refers to an article published by the Watson’s Magazine in response to Booker T. Washington, a dominant leader in the African-American community. During a public speech, Washington had affirmed that the black race was ethnically superior to the white race and that in the thirty years following the end of slavery, it had progressed more rapidly than the Latin race had in a thousand years (Watson, Citation1905, p. 392–398). The strategy of uplifting the Italian race is clearly apparent in this extract: it attempts to destroy any connection between Italy and savagery – in those years associated with the black community – and encourages Italian immigrants to take pride of such proclaimed superiority (to throw it in the face). The claims of the black race being superior to the white race become in this way as “stupid” and “false” as the claims of the Italian race not being white.

We will now analyze the context of occurrence of “race” in an excerpt from La Stampa (Excerpt 6).

(6) In Dalmazia, ove sortirono i natali tanti illustri italiani, ove l’ammirazione ed il culto per la patria nostra fu grande sempre, l’egemonia morale italiana va scomparendo con dolorosa rapidità. La nostra lingua, insegnata un tempo nelle scuole che accolsero giovanetti il Foscolo, il Tommaseo, il Paravia, cede ora il campo ad un povero e rude dialetto slavo; il dolce, artistico sentimento italiano si ritrae di fronte all’irrompere di idee barbare portate da una razza che s’impone pel vigore della propria giovinezza. (La Stampa, 19–20 March 1889)

In Dalmatia, where so many illustrious Italians were born, where there always was great admiration and worship for our country, the Italian hegemony is disappearing, painfully quickly. Our language, once taught in the same schools that hosted the young Foscolo, Tommaseo, and Paravia, now gives in to a poor and rude Slavic dialect; the sweet, artistic Italian sentiment recoils at the invasion of barbaric ideas brought about by a race imposing itself for the strength of its youth.

Though presenting similarities with the narrative adopted by the Italian ethnic press, Excerpt 6 is rather different for both aims and perspectives. The article refers to the pan-Slavism movement, a nineteenth-century movement that advocated the achievement of common cultural and political goals for the peoples of eastern and east central Europe based on a common ethnic background shared by Slavic-speaking peoples. The journalist is using the image of a glorious Italian literary past to contrast the superiority of the Italian language with the “poor” and “rude” Slavic “dialect”. The Italian sentiment is “sweet” and “artistic” as opposed to a barbaric ideology which is imposing itself in virtue of a stronger race. This example shows a slightly different narrative from the Italian American one; although the Italian race is often framed through the victimization lens in both outlets, here the racial perspective is not used to negotiate social inclusion, but to create alarmism toward the “disappearing” of the Italian language and, by extension, heritage. Such alarmism is constructed through the use of images of invading waves, also apparent in the title of the article L’Italia e la marea slava (Italy and the Slavic wave), which are “painfully quickly” taking over Italianness.

Results summary

The results offer a comprehensive view of how the concept of being Italian was constructed by the press in the two Italian communities. In ChroniclItaly, the DH analysis of the semantic distribution of salient words such as italianità, Italia & bianco, and razza revealed an insistence on concepts of Italian racial superiority, purity, Italian whiteness, and a glorious Roman heritage in opposition to images of a dark, obscure, and horrendous Africa. In La Stampa, on the contrary, the emphasis was on concepts of national cohesion with the most frequent words being national Government, patriotism, Risorgimento and Italian sentiment. The combination of text mining and semantic modeling not only facilitated a more immediate identification of the topics, but thanks to the semantic similarity clustering, it also made the relationship between the words more interpretable.

The DHA allowed for the triangulation of linguistic data, the two different social contexts as well as the scrutiny of concurrent socio-historical events. It provided deeper insights into the mechanisms underpinning the narratives in the two data-sets, including the factors shaping them (i.e., different agendas, different socio-cultural contexts), and, ultimately, the two different constructions of italianità. Specifically, it showed that the Italian American press transformed the concept of Italianness into a synonym for American, civilized, and white, thereby using this semantic anchor as a tool to negotiate racial inclusion in the transatlantic context. The press in Italy, on the contrary, used italianità to convey national pride and union, and, although to an extent it made use of a rhetoric of a superior civilization, the concept of italianità was mainly used to fight against the opponents of the Risorgimento, and ultimately, to maintain political stability.

Conclusions

This article offered a new perspective on the process of identity formation of Italian immigrants in the United States by comparing discursive practices in ethnic newspapers with those of the press in their home country. A mixed-method approach of close and distant reading explored how the concept of Italian identity, italianità, was constructed by printed media in Italy and in the United States between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. It showed that while in Italy, italianità became a means to create national belonging and unity following the political unification of Italy, in the United States, Italianness merged into racial narratives becoming a means to assert Italian whiteness and vindicate social inclusion.

Methodologically, the study refined distant text mining with close reading discourse analysis, which proved especially effective at providing a rich picture of the way the press on both sides of the Atlantic articulated concepts of national identity, race, culture, and heritage. Computational methodologies enabled us to base our interpretations of larger quantities of text, representing a broader sample of public discourse, while yielding verifiable and reproducible results. Once the general topic structures of the two datasets were uncovered, DHA allowed us to understand the factors that shaped how the press represented being Italian within the two communities, opening up an interpretation of the way such coverage impacted on public attitudes, political outcomes, and the wider society. A methodological advantage of a mixed-methods approach is that it offers an inductive bottom-up process that generates and identifies topics from within the historical corpus, rather than being deducted from previous findings or conceptual frameworks. For instance, the comparative approach adopted here further advanced our knowledge of the extent to which the media construction of Italian identity historically depended on external social and economic factors, rather than reflecting “innate” ethnic‐cultural features.

Understanding media construction of ethnic identity is vital, especially in our current era characterized by an unprecedented use of media to articulate and incite xenophobia and immigration fears. Moreover, by focussing on one of the most significant periods in the history of migration and one of the largest migrant groups in the United States, the results of this study may be generalized to other diasporic communities. Indeed, so much as countless other immigrant groups, Italians’ journey toward the achievement of full inclusion was all but straightforward; their path toward integration shared much of the adversities with myriad other groups from all over the globe who had to face enormous social challenges before being accepted within the American society. To review past narratives becomes in this way an important tool for analyzing and understanding current attitudes toward specific ethnic identities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. “L’Italia è fatta. Restano da fare gli italiani.” All translations in this article are by the authors. For the attribution of this quote to d’Azeglio, see also Patriarca (Citation2010), p. 51.

2. For a more detailed description of ChroniclItaly, please see Viola and Verheul (Citation2019).

References

- Anthony, L. (2018). AntConc 3.5.6. Retrieved from http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/

- Barrett, J. R., & Roediger, D. (1997). Inbetween Peoples: Race, Nationality and the ‘New Immigrant’ Working Class. Jamerethnhist Journal of American Ethnic History, 16(3), 3–44.

- Bollati, G. (2011). L’italiano: Il carattere nazionale come storia e come invenzione. Torino, Italy: Einaudi.

- Briggs, J. W. (1978). An Italian Passage: Immigrants to Three American Cities, 1890–1930. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Brodkin, K. (1998). How Jews became white folks and what that says about race in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers Univ. Press.

- Carravetta, P. (2017). After identity: Migration, critique, Italian American culture. New York, NY: Bordighera Press.

- Carravetta, P. (2018). The silence of the Atlantians: Contact, conflict, consolidation, 1880–1913. In W. J. Connell & S. G. Pugliese (Eds.), The Routledge history of Italian Americans (pp. 132–151). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Connell, W. J., & Gardaphé, F. L. (Eds.). (2010). Anti-Italianism: Essays on a prejudice. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Conzen, K. N., & Gerber, D. A., Morawska, E., Pozzetta, G. E., & Vecoli, R. T. (1992). The invention of ethnicity: A perspective from the U.S.A. Journal of American ethnic history, 12(1), 3–41.

- Deschamps, B. (2011). The Italian ethnic press in a global perspective. In G. Parati & A. J. Tamburri (Eds.), The cultures of Italian migration: Diverse trajectories and discrete perspectives (pp. 75–94). Madison [N.J.]; Lanham, Md.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press; Rowman & Littlefield.

- Foley, N. (1997). The white scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and poor whites in Texas cotton culture. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press.

- Forlenza, R., & Thomassen, B. (2017). Resurrections and rebirths: How the Risorgimento shaped modern Italian politics. Journal of modern Italian studies, 23(2), 291–313. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2017.1321931

- Gabaccia, D. R. (2003). Italy’s many diasporas. Retrieved from http://librarytitles.ebrary.com/id/10783063

- Graeme, H., & St-onge, D. (1998). Lexical chains as representations of context for the detection and correction of malapropisms. In C. Fellbaum (Ed.), WordNet: An electronic lexical database (pp. 305–332). Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Grillo, G. (1962). Cronaca che non è un epitaffio. I 65 anni della Gazzetta. Boston, MA: La Gazzetta del Massachusetts.

- Guglielmo, J., & Salerno, S. (Eds.). (2003). Are Italians white? how race is made in America. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Guglielmo, T. A. (2004). White on arrival: Italians, race, color, and power in Chicago, 1890–1945. Retrieved from https://apps.uqo.ca/LoginSigparb/LoginPourRessources.aspx?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&AN=92704

- Guha, S., Rastogi, R., & Shim, K. (2000). Rock: A robust clustering algorithm for categorical attributes. Information systems, 25(5), 345–366. doi:10.1016/S0306-4379(00)00022-3

- Handlin, O. (1990). The uprooted: The Epic Story of the Great Migrations That Made the American People (2nd ed.). Boston, Pennsylvania: Little, Brown.

- Harris, Z. S. (1954). Distributional structure. Word. Journal of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 10(2–3), 146–162.

- Hickerson, A., & Gustafson, K. L. (2016). Revisiting the immigrant press. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 17(8), 943–960. doi:10.1177/1464884914542742

- Jacobson, M. F. (1998). Whiteness of a different color. European immigrants and the alchemy of race. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- LaGumina, S. J. (1999). WOP! a documentary history of anti-Italian discrimination in the United States. Toronto, Canada: Guernica.

- LaGumina, S. J. (2018). Discrimination, prejudice and Italian American history. In W. J. Connell & S. G. Pugliese (Eds.), The Routledge history of Italian Americans (pp. 223–238). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Lanaro, S. (1988). L’Italia nuova: Identità e sviluppo, 1861–1988. Torino, Italy: G. Einaudi.

- Luconi, S. (2003). Frank L. Rizzo and the whitening of Italian Americans in Philadelphia. In J. Guglielmo & S. Salvatore (Eds.), Are Italians White? How Race is made in America (pp. 177–191). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Macdonald, J. S., & Macdonald, L. D. (1964). Chain migration, ethnic neighborhood formation and social networks. New York, NY: Milbank Memorial Fund.

- Massaro, D. R. (2003). Order Sons of Italy in America. In S. J. La Gumina, F. J. Cavaioli, S. Primeggia, & J. A. Varacalli (Eds.), The Italian American Experience: An Encyclopedia (pp. 430–433). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Newman, M. E. J. (2006). Modularity and community structure in networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(23), 8577–8582. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601602103

- Orsi, R. (1992). The Religious Boundaries of an Inbetween People: Street Feste and the Problem of the Dark-Skinned Other in Italian Harlem, 1920–1990. Amerquar American Quarterly, 44(3), 313–347. doi:10.2307/2712980

- Orsi, R. A. (2010). The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950 (3rd ed.). New Haven, Conn.; London: Yale University Press.

- Park, R. E. (1922). The immigrant press and its control. Harper & Brothers: New York, NY: London.

- Patriarca, S. (2010). Italian vices: Nation and character from the Risorgimento to the republic. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Pozzetta, G. E. (1973). The Italian immigrant press of New York City; the early years, 1880–1915. Journal of Ethnic Studies, 1, 32–46.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). The discourse-historical approach. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis (pp. 63–94). London, UK: Sage.

- Rhodes, L. (2010). The ethnic press: Shaping the American dream. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Roediger, D. R. (2005). Working toward whiteness: How America’s immigrants became white : The strange journey from Ellis Island to the suburbs. New York, NY: BasicBooks.

- Russo, P. (1972). La stampa periodica italo-americana. In R. J. Vecoli (Ed.), Gli italiani negli Stati Uniti. L’emigrazione e l’opera degli italiani negli stati Uniti d’America (pp. 493–546). Florence, Italy: Istituto di studi americani.

- van Dijk, T. A. (1993). Principles of Critical Discourse Analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249–283. doi:10.1177/0957926593004002006

- Vecoli, R. J. (1964). Contadini in Chicago: A Critique of The Uprooted. The Journal of American History, 51(3), 404. doi:10.2307/1894893

- Vecoli, R. J. (1993). Italian immigrants and working class movements in the United States. A personal reflection on class and ethnicity. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 4, 293–305. doi:10.7202/031067ar

- Vecoli, R. J. (1998). The Italian immigrant press and the construction of social reality. In J. P. Danky & W. A. Wiegand (Eds.), Print culture in a diverse America (pp. 17–33). Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois.

- Vellon, P. G. (2018). Italian American and Race during the era of mass immigration. In W. J. Connell & S. G. Pugliese (Eds.), The Routledge history of Italian Americans (pp. 212–222). New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Viegas, F. B., Wattenberg, M., & Feinberg, J. (2009). Participatory visualization with wordle. IEEE Trans Visual Comput Graphics IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 15(6), 1137–1144. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2009.171

- Viola, L. (2018). ChroniclItaly: A corpus of Italian American newspapers from 1898 to 1920. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht University. doi:10.24416/UU01-T4YMOW

- Viola, L. (2019). Polentone vs terrone: A discourse-historical analysis of media representation of Italian internal migration. In L. Viola & A. Musolff (Eds.), Migration and Media: Discourses about identities in crisis (pp. 45–62). Amsterdam/Philadelphia, The Netherlands: John Benjamins. doi:10.1075/dapsac.81.03vio

- Viola, L., & Verheul, J. (2019). Mining ethnicity: Discourse-driven topic modelling of immigrant discourses in the USA, 1898–1920. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. doi:10.1093/llc/fqz068

- Watson, T. E. (1905). “Is the black man superior to the white?”. Tom Watson’s Magazine, June 1905, vol. I, No 4, 392–398. Retrieved from https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b3058085;view=1up;seq=413)

- Xu, R., & Wunsch, D. (2005). Survey of clustering algorithms. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 16(3), 645–678. doi:10.1109/TNN.2005.845141