ABSTRACT

We investigated the development of professional commitment over time and its relation to work experiences of novice nurses. We used a longitudinal mixed-method approach based on weekly reported quantitative commitment scores and qualitative descriptions of experiences. Specifically, we examined turning points in commitment trajectories and analyzed qualitative characteristics of the turning point. To determine a turning point, we firstly computed a smoothed trajectory for each individual and defined each point beyond the 95% interval of this smoothed trajectory as exceptional. Secondly, we explored whether the commitment development changed after an exceptional point with regard to the slope-valence or commitment strength. The sample consisted of 18 novice nurses. Two third of them revealed at least one turning point, thus the professional commitment development of novice nurses was characterized by peaks and dips that were followed by changes in the commitment development. The analysis showed that turning points followed by positive commitment development typically were characterized by positive experiences. These experiences often concerned relatedness or competence. Turning points followed by a negative development were not consistent: they could be positive, negative, or ambiguous experiences. Many of the negative experiences concerned negative organizational issues. We concluded that there is not a simple relation between commitment development and positive or negative characteristics of an experience. The context and underlying meaning of the experiences should be taken into account to interpret the commitment changes.

Introduction

In this study, we focused on the development of professional commitment and its relation to work experiences in novice professionals. Professional commitment refers to the presence of stable goals, values, and beliefs that provide direction, purpose, and meaning to one’s professional life and professional identity. It signifies the individual’s degree of personal investment. In their systematic literature review, Grosemans et al. (Citation2020) state that the development of a professional identity in transition from study to work is challenging and entails balancing between different aspects of life. However, their literature review shows that most research is based on group data, and little is known about the individual trajectories of novice professionals. In this study, we investigated individual trajectories of commitment development, and more specifically the type of experiences that coincides with turning points in the trajectories of commitment development in young professionals. The target group of this study consists of novice nurses. We think this group may be representative for other novice professionals in the public domain, such as teachers and police officers. An important reason to consider novice nurses is the ongoing concerns about the shortage of nurses that may threaten the quality of health care (OECD, Citation2019; WHO, Citation2020) and specifically, the assumption that this is the result of a lack of career or professional commitment (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). However, existing studies frequently focus on organizational commitment and job satisfaction rather than on professional commitment, and moreover, they are based on average group of nurses rather than taking into account the individual differences (e.g., De Gieter et al., Citation2011; Hayes et al., Citation2012; Parry, Citation2008). In the current research, we therefore focus on individual trajectories of commitment development and specifically, on how specific experiences affect the trajectory. The aim is to get more theoretical knowledge about commitment development in novice professionals, and in addition, to apply this knowledge in the guidance of novice nurses.

Professional identity development

The theoretical framework for this study is based on Erikson’s (Citation1968) identity theory. Erikson considered the development of identity as a major developmental task occurring during adolescence (Erikson, Citation1968), although in modern age the timing of this development may have delayed to emerging adulthood (Arnett, Citation2015). We define identity development as the trajectory of an individual’s commitment development. Identity development takes place in different domains (Bosma, Citation1992) but here we focus specifically on the professional domain. Marcia (Citation1966) described in his identity status model how the process of identity development typically begins with the exploration of one’s own possibilities, emotions, values, and preferences, as well as the opportunities and constraints provided by the environment. Through this exploration, individuals develop a sense of what is important to them, what helps them understand their own identity, and what they aspire to do in their careers, ultimately leading to the formation of commitments. In later phases of development, commitments may need adjustment to changing circumstances. This may lead to new phases of exploration, followed by the development of adjusted, refined and more mature commitments. The identity status model was the basis of new models aiming to address the developmental process and the mechanisms of change (see, e.g., Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2001; Crocetti et al., Citation2008; Klimstra, Citation2012; Kroger, Citation2003; Luyckx, Citation2006) in addition to the role of the context in identity development (see, e.g., Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2008; Luyckx, Goossens, & Soenens, Citation2006). One of the most elaborated models is developed by Luyckx and colleagues. In their dual-cycle model of identity development, the concept of commitment is distinguished in two separate processes: making a commitment and identifying with the commitment. They describe a trajectory of identity development in which exploration in breadth is followed by commitment making, after which exploration in depth occurs, leading to a stronger identification with commitment. When commitments become unsatisfactory, they become weaker and a new phase of exploration in breadth may follow. In this study, we focus on these commitment changes or turning points in the development.

Most commitment models (Crocetti et al., Citation2008; Luyckx, Goossens, Soenens, & Beyers, Citation2006) are based on aggregated analysis of group data and do not offer insight in the individual processes that may lead to such changes or turning points. As argued in recent identity development literature, it is necessary to analyze individual time series of data or trajectories of data across a certain period in order to understand the process of commitment development (Kunnen, Citation2019; Van der Gaag, Citation2023). These authors argue that commitment development takes place in daily interactions with the context. Trajectories of commitment development can be seen as chains of such interactions. In the next section, we discuss how we may get insight in the way in which the different steps build up to specific trajectories.

The role of experiences in commitment development

Bosma and Kunnen (Citation2001) developed a process model of identity development in which day-to-day experiences are assumed to affect commitment strength. Experiences that confirm one’s commitment strengthen the commitment, and experiences that challenge the commitment cause emotional conflict and over time may weaken the commitment and lead to accommodation of the commitment, or withdrawal from the commitment. Experiences that challenge the commitment may be for example failures, disappointment, or rejection in situations where the commitment is at stake. Recently, several other authors developed dynamic models describing the mechanisms behind of how commitments emerge from real time interactions (Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2001; Klimstra et al., Citation2010; Van der Gaag, Citation2017). Basically, all models assume that positive experiences support existing and emerging commitment, and negative experiences may challenge the commitments, and lead to a decrease of the strength of existing commitments and eventually change in commitment (Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2001).

However, each individual has many experiences and not all are equally important. An underlying aim of the study is to get insight in the type of experiences that have most impact on identity development. Previous research had focused on the role of highly emotional experiences (Kunnen, Citation2023). Several studies found a relation between specific experiences and the development of commitment. Van der Gaag (Citation2017) stresses the role of emotions in the development of commitment, in addition to the role of exploration. Positive emotional experiences tend to be related to higher commitment, as compared to more neutral experiences (Nogueiras et al., Citation2017). Experiences in which basic needs were fulfilled, are related to higher commitment scores, and experiences with frustrated need fulfillment to a lower commitment level, as compared to neutral experiences (Kunnen, Citation2022). In this study, we analyze the dynamics of the commitment trajectory itself to detect exceptional time points that may be turning points in the developmental trajectory of the professional commitment over time. As a second step, we explore the content of the experiences that “belong” to these specific time points.

In order to get insight into novice nurses’ changes in professional commitment strength, this study aims to give an answer to the following research questions:

(1) Can we identify exceptional experiences that become turning points in the individual commitment trajectories, meaning that they are followed by a significant change in the development of commitment strength?

We expect that specific impactful experiences may change the process of commitment development.

(2) What characterizes these exceptional experiences?

Logically, we expect that negative experiences are followed by a decrease in commitment, and positive experiences by an increase in commitment.

Method

This study analyses individual trajectories of commitment and links this to the work experiences. It employs a mixed-method study design, where qualitative diary data has been used to interpret the quantitative trajectories of commitment (Bryman, Citation2006). Giesbers et al. (Citation2021) recently emphasized the added value of employing a mixed-method study design to reveal a nuanced link between nurse’s feedback, work engagement, and burnout. By using the mixed-method design, we provide a nuanced insight in how trajectories develop and which work experiences lead to an increase or a decrease in the trajectory.

Design

For this study, an explorative mixed-method design was used, based on a diary study combined with a short closed-ended questionnaire. By using the quantitative patterns derived from the closed-ended questionnaire, we defined specific turning points. We used the qualitative data to get insight in the specific characteristics of these turning points (cf. Creswell, Citation2015; Greene et al., Citation1989).

Sample, setting and participants

The sample consisted of 18 novice nurses, with a Bachelor’s degree in nursing and working at a university medical center. All nurses were female with a mean age of 23 years old (SD = 1.4). They had a maximum of 12 months’ work experience in the hospital; eight nurses (44%) had no experience at all. They were recruited at one University Medical Centre in the Netherlands. The inclusion criteria for participation were Bachelor’s degree graduated nurses, age <30 years old, and work experience as a nurse ≤12 months. Managers of different wards supported in the recruitment of the participants. The participants who met the criteria and who expressed by e-mail their willingness to participate were informed during an introductory meeting of the research project about the aims of the study, the expectations from the participants, and the ethical concerns. After they signed an informed consent, they received between September 2013 and September 2014 an invitation with a link to the weekly questionnaire in Qualtrics.

They completed a total of 577 weekly records (range 18–50, on average 32 weekly records per participant). In previous analysis of the same data set, we analyzed qualitative diary data (Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018a) or aggregated quantitative data (Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018b). This study is a reuse of the data to answer a new research question. The current study is the first to address the shapes of the individual trajectories and to combine the qualitative and quantitative data in the study.

Instruments

The nurses received a questionnaire each week. It started with an open question: “Please describe a personal or work-related experience from the past week that really was important to you. What was the experience? In what situation? How did you reflect on this experience and how did it affect your work?” Here, the nurses described in detail their most important work-related experience every week, across one year. After describing their experience, they were asked to complete a short survey measuring their professional commitment. Commitment was measured with a three item-scale (α = .85) derived from the Repeated Exploration and Commitment Scale related to Education (RECS-E; Van der Gaag & Kunnen, Citation2013): “Do you stand by your choice for this particular profession?,” “Do you think that you meet the expectations of your profession?” and “Do you feel confident in your profession?” The questions were answered on a scale from 1 (“not at all”) to 6 (“very much”). See for more information Ten Hoeve et al. (Citation2018a).

Ethical considerations

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Committee Psychology of the University. The participants were provided with oral and written information about the study, and they signed a consent form. Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw without any consequence.

Quantitative data analysis: exceptional points and turning points

The commitment trajectories for each participant are the representation of the series of commitment scores per measurement point. Each commitment score consists of the mean of the three items (range 1–6). Our technique to determine exceptional points is based on Nogueiras et al. (Citation2017). Nogueiras and colleagues defined exceptional points as data points that are outside the 95% confidence interval of the linear regression line through all data points. However, instead of the linear regression line that was used in their approach, we computed a smoothed trajectory of each individual. There is much evidence that commitment development is non-linear (Kunnen, Citation2012). Contrary to linear models, smoothing preserves gradual non-linear changes such as u-shaped and s-shaped trajectories. Following Nogueiras et al., we computed a confidence interval of 95% (+ and − 1.96 SD) of the smoothed trajectory, and we defined exceptional points as points that lie outside this confidence interval. The smoothed trajectory consists of the average of 20 points (the target point and the 19 previous data points). For the first 19 data points, the average is computed for all previous points, including the data point itself. We used Excel for making graphs of the trajectories, and for computing the smoothed trajectories and confidence intervals. For each exceptional point we identified in a trajectory (i.e., outside the range between – and + 1.96 SD), we analyzed whether this point could be identified as a turning point (thus a point where the development of the commitment changed). Again following Nogueiras et al., we defined an exceptional point as a turning point if at least one of two criteria were met. First, we tested for a significant difference in the average commitment scores before and after the exceptional point. Second, we computed the slope before and after the exceptional point, and checked whether a valence shift in the slope existed. Both criteria characterize an enduring change in the course of a trajectory, but depending on the shape of an individual trajectory it may be that only one is present. We excluded exceptional points within the first three and the last three measurement points in each trajectory, because we considered a slope over less than four measurement points to be unreliable.

To test whether the difference between the average scores before and after the exceptional point is significant, we used a Monte Carlo procedure because the observations in the data are nested and dependent, and therefore, the requirement of independent observations for a t-test was violated.Footnote1. For a complete description of the Monte Carlo procedure, we refer to Van Geert, Steenbeek and Kunnen (Citation2012). As a first step in this procedure, we computed the average commitment score before and after the exceptional point and the difference between these averages. The Monte Carlo analysis, based on a probability procedure, tests whether the differences in these average commitment scores are an incidental finding. The Monte Carlo analysis compares the observed data with randomly shuffled data. Hence, we first shuffled all data of the individual trajectories and computed the averages of commitment of these shuffled data before and after the exceptional point, and computed the difference between the two averages of the shuffled data. This is called one run. We repeated this procedure 10.000 times and registered in how many of these 10.000 runs the difference between the average of the shuffled commitment score before and after the exceptional point was larger than the difference in our observed data. If in 10.000 runs, this happens in less than 500 runs (thus in less than 5%) this means that there is less than 5% chance (that is p < .05) that our findings were just an incidental finding.

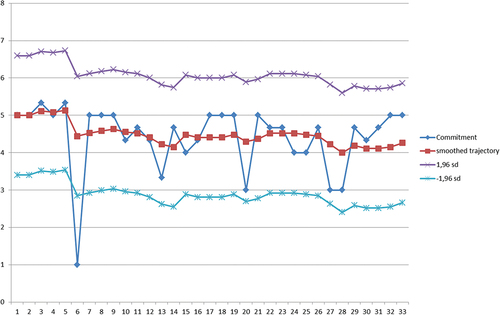

Illustration of the procedure: shows the trajectory of one participant and the smoothed trajectory with a 95%- confidence interval. The x-axis represents all measurement points. We see an exceptional point at measurement 6. The average of the data points before this point (thus measurements 1–5) was 5.1 and the average for data points after point 6, thus 7–33, was 4.42. The difference was found to be significant (p = .02). This means that the first criterion was met, i.e., a significant difference between the average commitment scores before and after the exceptional point. For the second criterion, we tested whether there was a valence shift in the slope. The slope for data points 1–5 was .07, and the slope for the points 7–33 was −.01. So, there is a valence shift in the slope and the second criterion was met as well. This means that we considered this exceptional point to be a turning point for professional commitment in this participant. This procedure was followed for each exceptional point that is more than three points distance of either the beginning or the end of the trajectory.

Qualitative data analysis: characteristics of turning point experiences

After identifying the turning points, we linked them to the experience. Participants described this experience in the weekly “diary” simultaneously with scoring their commitment. In the previous work, we have explained in detail how we developed a coding system for the reported experiences (Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018a). This coding system includes the following constructs: Professional commitment as organizational context (i.e., complexity of care, work pressure, unrealistic expectations, change of ward/location); Competence (i.e., (lack of) feelings of competence, positive/negative feedback, reflection, constructive feedback, display of competence); Autonomy (i.e., (lack of) control); Relatedness (i.e., negative or positive relationship with patients, colleagues, manager or supervisor, physicians, (good) teamwork, (lack of) belongingness); Development ((lack of) opportunity to learn, ongoing experiences in reference to the opportunities to grow in their profession); Goals (personal and work-related, related to events in the future); Fit (i.e., (mis)fit with ward or profession); Existential experiences (illness, death, suffering, or young patients).

Two authors read and reread the reported work experience related to the turning point (interrater agreement 79%). We used open codes for similar and meaningful elements in the described work-related experiences, and merged into subthemes (see Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018a).

Results

shows the mean, variability, and slope of the individual trajectories.

Table 1. Mean, variability, and slope of the individual trajectories.

shows the characteristics of all points that meet the criteria for an exceptional point. Most nurses (16 out of 18) have one or more exceptional points in commitment strength in their trajectory. Of the 24 exceptional points, 18 turning points were identified in 13 nurses. Most turning points (10) are defined as such on the basis of the slope, five are defined based on the mean, and three turning points met both criteria. Out of 18 turning points, 14 turning points have a low value (below the 95% confidence interval) and four have a high value (above the 95% confidence interval). Ten turning points were followed by a negative change (decrease of mean and/or slope), six were followed by a positive change, and two turning points were followed by ambiguous development, meaning that the slope showed a positive change, and the mean a negative change.

Table 2. Criteria for turning points per nurse per exceptional point.

In order to address the research question what characterizes the workplace experiences that preceded the turning points, we analyzed the reported weekly experiences at the time of the turning points. We distinguished between turning points into a more positive development (increase of mean and/or slope) and turning points into a negative development (decrease of the mean and/or slope). Based on the coding scheme (Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018a) we assigned codes for themes and subthemes to each turning point experience. Positive experiences are characterized by positive codes, negative experiences by negative codes. Ambiguous experiences have both positive and negative codes.

shows an overview of the turning points related to the work experiences. Thirteen out of 18 experiences during a positive or negative turning point could be classified as either positive or negative.

Table 3. Turning points related to themes and subthemes in the reported work experiences.

Positive developmental change coincided five times with positive experiences (nurse 7, points 9 and 24; nurse 9, point 12; nurse 11, point 19; nurse 17, point 19), and once with a negative experience (nurse 11, point 14). Negative developmental change coincided three times with negative experiences (nurse 3, point 16; nurse 9, point 8; nurse 14, point 22), two times with positive experiences (nurse 6, point 6; nurse 15, point 13), three times with ambiguous experiences (nurse 1, point 6; nurse 6, point 14; nurse 10, point 11), and two times with neutral experiences (nurse 5, point 35; nurse 8, point 9). Two turning points were ambiguous itself: they were followed by a positive change in the slope, but a negative change in the mean value of commitment. Both turning points were of the same nurse and directly adjacent (nurse 2, points 12 and 13), and the work-related experiences were negative.

As revealed in terms of themes and subthemes, it turns out that in turning points followed by a decrease in commitment, negative organizational issues are most frequently described (four times; nurse 1, point 6; nurse 9, point 8; nurse 10, point 11; nurse 14, point 22).

When turning points followed by a positive development of professional commitment, positive relatedness was described most often (four times; nurse 7, point 24; nurse 9, point 12; nurse 11, point 19; nurse 17 point 19), followed by positive competence experiences (two times; nurse 7, point 9; nurse 11, point 19).

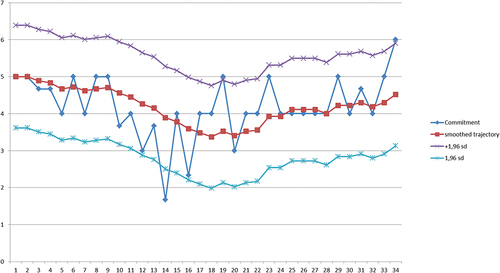

Hereafter, we illustrate some of these nurse’s commitment trajectories and work experiences in more detail. In several trajectories, the ambiguous outcomes can be better understood when we take a closer look at the shape of the trajectories. The ambiguous development (see ) is seen after two adjacent experiences concerning negative relatedness, existential doubt and “feeling overwhelmed” of the same nurse (nurse 2). The ambiguity means that after these experiences we saw a positive slope of commitment, but the mean level of commitment was lower following the experiences than it was before. In the graph () can be seen that the commitment in the first weeks is very high, and shows a strong decrease until the turning point. Afterwards the commitment starts to grow again, but not (as yet?) to the initial level. With some caution, the development could be interpreted as a positive development.

Figure 2. Trajectory of one nurse (N2) and the smoothed trajectory with a 95%- confidence interval.

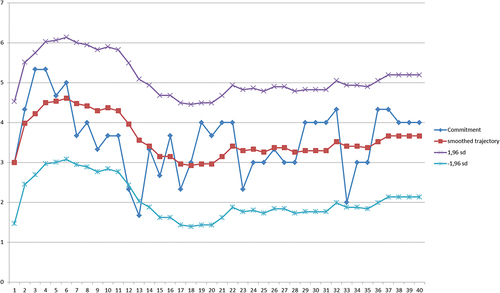

Similar to nurse 2, nurse 11 described in point 14 negative experiences (see ), which were unexpectedly followed by a positive development of the professional commitment trajectory (see ). She described negative private issues and negative work-private balance. In a second turning point (time point 19), she describes how changes in her private life made her feel confident again. Both turning points occurred shortly after each other (time point 14, 19). The first experience may have stimulated her to explore and change her private life, and she succeeded five weeks later. She started with strong commitments at the beginning of the trajectory, and after these turning points, she regained a strong commitment.

Figure 3. Trajectory of one participant (N11) and the smoothed trajectory model with a 95%- confidence interval.

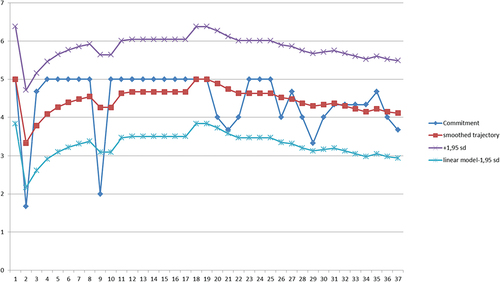

Thus, a closer look at the shape of the trajectory experiences may clarify ambiguous outcomes. Another explanation for ambiguous outcomes could be found in the experiences before and after the turning point. The change may also be initiated by a repetition of small experiences. For example, nurse 8 (see ) described a move from her ward to another location. Although her commitment score was exceptionally low, she described the move in a neutral way. The first weeks after the turning point the previous high level of commitment was regained, but after several weeks a slow but steady decrease in commitment started. A possible explanation is that the move may have been followed by a sequence of not extreme, but still, negative experiences that finally resulted in the negative commitment development.

Figure 4. Trajectory of one participant (N8) and the smoothed trajectory with a 95%- confidence interval.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to get more insight in the role of work-related experiences in the development of professional commitment. We focused on novice nurses as a case study. Using a mixed-methods study design enabled us to integrate the quantitative trajectories of commitment development with qualitative diary descriptions across one year. We identified exceptional points in the individual commitment trajectories and explored whether the development of commitment changed (turning point) after such an exceptional point, either because of a valence change of the slope, or because of a significant change in the mean commitment strength. Two third of the nurses showed at least one turning point. This confirms our first research question: we can identify exceptional experiences that become turning points. Thus, for most nurses, the trajectory of commitment development over one year showed at least one significant change that seemed to be related to an impactful experience. This is in line with our expectation based on the model of Bosma and Kunnen (Citation2001). It is also in line with previous research. For example, Anthis (Citation2002) demonstrated a relation between significant stressful life events and commitment change.

Of the experiences that coincided with the 18 turning points, 13 experiences could be classified as either positive or negative. Our classification of negative and positive experiences is inductively derived from the diaries. Often, the classification is based on explicitly mentioned emotions (sad, proud). Sometimes the descriptions implicitly refer to a positive or negative emotional state, such as: “I feel stronger and receive more positive feedback” (classified as positive experience). This means that the role of emotions, as stressed in the model of Van der Gaag (Citation2017), is often explicit in our findings. Three experiences included both negative and positive elements. Although coded as ambivalent, all three experiences concerned a problematic and challenging organizational situation. The positive part of the experiences referred to a learning experience and/or support from colleagues. Two experiences (N5 and N8) were described in an emotionally neutral way, but referred to situations in which new environments and experiences where encountered. Here, exploration may play a role. The new environments and new experiences may have challenged the existing commitment and triggered the person to reconsider (and lower) her commitments.

The second research question addressed the characteristics of the turning point experiences to get a better understanding of what kind of experiences may influence the commitment development of novice nurses. The most frequent pattern in our data is that positive development coincides with positive experiences. Strikingly, negative commitment development coincided by different kinds of experiences: six times by negative or ambiguous experiences, twice by positive, and twice by neutral experiences. Thus, the results partly fits with empirical support, for example by Turner (Citation2020), who showed in graduate students that after positive experiences their study commitment increased, whereas after negative experiences their study commitment decreased. However, consistent with theory about identity development (Bosma & Kunnen, Citation2001; Van der Gaag, Citation2017), our data reveal that many experiences are not merely positive or negative but a mixture of both or even neutral. Moreover, the relation of experiences with commitment change is not a simple one-to-one relationship. Van der Gaag (Citation2017) argues how atypical effects of especially negative turning points depend on how individuals interpret their experiences. For example, a nurse may increase her commitment after negative experiences, such as a mistake at work, because she perceives that she has to practice and get more experience, which may increase her (behavioral) commitment to her work. In the same vein, strongly negative experiences probably often result in a negative commitment development, but they can also be triggers to explore and to initiate changes in the working situation and result in positive commitment scores. This is consistent with the model of Bosma and Kunnen (Citation2001). This model elaborates how sequences of negative experiences may initially lower the commitment, but also increase the exploration, and finally result in new commitment development. An example of this may be nurse 9 (time point 8) who describes how she learns from a negative experience. Also, the negative experience of nurse 11 (time point 14) was followed by a positive development. The experience was described in a very negative emotional way and this probably triggered her to change. In a second turning point (19), she reported about these changes, and in the graph a strong growth in commitment is visible afterward. Although our method indicated two turning points, in fact this phase could be interpreted as one period of crisis. It was also relevant that although both the negative experience and the positive change concern her private life, they had strong impact on her work commitment. This stresses the importance of a person centered approach, as conducted in our study by the use of open diaries, in which all relevant lived experiences could be reported.

Regarding the themes and sub themes, it turns out that in turning points followed by a positive development of commitment, experiences concerning competence and relatedness are most frequent. The description of these codes (Ten Hoeve et al., Citation2018a) resembles the definition of the basic needs in the self-determination theory by Ryan and Deci (Citation2000). This finding is also in line with the findings of Kunnen (Citation2022) who showed in interns that experiences related to the basic needs play a crucial role in professional commitment development.

In turning points followed by a decrease in commitment, negative organizational issues are most frequently described. The importance of perceived organizational issues in nurses is also found in other cross-sectional studies (Lee & Jang, Citation2020). We elaborate this in the next section.

Practical implications

Although few studies investigated commitment with longitudinal statistical analysis techniques (Fernet et al., Citation2020), obtaining insight in theoretical and practical implications the link with descriptions of work-related experiences is crucial. Therefore, the combination of the qualitative analysis of work-related experiences in the diaries with the advanced analysis technique of turning points in the trajectories was very appropriate for the purpose of the current study. This study provides a better understanding of the impact of individual work-related experiences on the professional commitment trajectories of novice nurses.

Since our findings suggest that especially negative organizational events are followed by a negative change in the commitment development of the nurses, more attention should be paid to organizational circumstances and supervision of incoming professionals. Following Henderson, Ossenberg and Taylor (Henderson et al., Citation2015), we propose an effective guidance of novice nurses with providing the opportunity to learn within a safe environment and get support from colleagues. Furthermore, getting support from supervisors or mentors in a mentoring program for newly graduated nurses can enhance commitment and contribute to professional identity development. By doing so, it may reduce turnover intentions (Chen et al., Citation2015; Zhang et al., Citation2016). However, we emphasize the importance of taking into account individual perceptions of work-related experiences and the work environment. Based on our variety in the trajectories of commitment and the links with different work-related experiences, we stress that a personalized approach is crucial in the supervision of novice nurses when they enter the workforce. A “one-size-fits-all” approach is inappropriate considering the variety of experiences and the unequivocal relation with commitment, in particular after negative experiences.

Strengths, limitations and further research

The strength of this study is that it is an intensive longitudinal study with many data points across one year and rich qualitative and quantitative outcomes. We used a new advanced way to get more insight in the ups and downs of individual commitment development and the relation with concrete work-related experiences. Another strength concerns the focus on individual trajectories. We found that negative experiences are often followed by a decrease in commitment, but not always. If we would have used means and aggregated data, this would not have been visible. Despite the fact that our findings show the importance of investigating individual trajectories of commitment in the light of work-related experience, we need to consider a few limitations. First, the unavoidable limitation of such an intensive analysis is that the number of participants is low. Therefore, we need to be cautious with making strong claims based on the findings despite the large number of within-person measurements. The results are promising and point to specific directions, but research with more participants is needed. We need also research in other groups (for example senior nurses or other professionals) and institutions to see whether similar patterns are found. There are also some methodological limitations. We did not take into account the size of the slopes in determining valence shifts. We choose this approach because it is not easy to determine what change in slope would be relevant, but it may result in a slight overrepresentation of meaningful slope changes. In addition, we focused on the experience during the turning point itself. Bosma and Kunnen (Citation2001) assume that also accumulation of negative experiences may trigger decrease of commitments. It is plausible that in some cases, chains of experiences may have resulted in the observed change. Future research may focus on the chains of experiences in order to find out whether accumulation of negative or positive experiences may result in changes in commitment development. Finally, we used two criteria to determine a turning point. However, several figures (for example for nurse 2) show that due to the irregular shapes of a trajectory these criteria may not be met, despite the fact that on face value, there is a turning point. It demonstrates that commitment development is not only non-linear but also irregular. On the one hand, we think that using quantitative criteria may help to decide in an objective way whether there is a turning point, on the other hand we need to be aware that by using these criteria we may miss turning points.

Conclusion

The professional commitment development of novice nurses is not a stable and gradual process but is characterized by peaks and dips. These so-called exceptional points are followed frequently by changes in the commitment development and hence in professional identity development. Our results provide some evidence for the general model of Bosma and Kunnen (Citation2001): positive relational experiences are frequent game changers for the better, while negative organizational experiences more often result in a decline of commitment development, but not always. Basic needs related experiences were most frequently associated with positive turning points, whereas negative organizational issues were the most frequently experienced in negative turning points. The study showed a complex relationship between individual trajectories and work-related experiences. We concluded that there is no simple one-to-one relation between commitment development and positive or negative experiences. Therefore, the context, the perceived experiences and underlying meaning of experiences should be taken into account to understand commitment changes and professional identity development. Practical implications are that personalized support is important for novice nurse’s professional commitment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We used Excel “Macro DSTfunctions,” developed by Steinkrauss (Citation2016).

References

- Anthis, K. S. (2002). On the calamity theory of growth: The relationship between stressful life events and changes in identity over time. Identity, 2(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XID0203_03

- Arnett, J. J. (2015). Emerging adulthood : The winding road from the late teens through the twenties (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Bosma, H. A. (1992). Identity in adolescence : Managing commitments. In R. Adams, G. R. Guilotta, & T. P. Montemayor (Eds.), Adolescent identity formation (Vol. 4, pp. 91–121). Sage.

- Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2001). Determinants and mechanisms in ego identity development: A review and synthesis. Developmental Review, 21(1), 39–66. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2000.0514

- Bosma, H. A., & Kunnen, E. S. (2008). Identity-in-context is not yet identity development-in-context. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.03.001

- Bryman, A. (2006). Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research, 6(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058877

- Chen, F., Yang, M., Gao, W., Liu, Y., & De, G. S. (2015). Impact of satisfactions with psychological reward and pay on chinese nurses’ work attitudes. Applied Nursing Research: Anr, 28(4), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2015.03.002

- Creswell, J. W. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., & Meeus, W. (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.002

- De Gieter, S., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2011). Revisiting the impact of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on nurse turnover intention: An individual differences analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(12), 1562–1569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.06.007

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton.

- Fernet, C., Morin, A. J. S., Stéphanie, A., Marylène, G., Litalien, D., Mélanie, L.-T., & Forest, J. (2020). Self-determination trajectories at work: A growth mixture analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 121, 103473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103473

- Giesbers, G. A. P. M., Schouteten, R. L. J., Poutsma, E., van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., & van Achterberg, T. (2021). Towards a better understanding of the relationship between feedback and nurses’ work engagement and burnout: A convergent mixed-methods study on nurses’ attributions about the ‘why’ of feedback. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 117, 103889–103889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103889

- Greene, J. C., Caracelli, V. J., & Graham, W. F. (1989). Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 11(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737011003255

- Grosemans, I., Hannes, K., Neyens, J., & Kyndt, E. (2020). Emerging adults embarking on their careers: Job and identity explorations in the transition to work. Youth & Society, 52(5), 795–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X18772695

- Hayes, L. J., O’Brien-Pallas, L., Duffield, C., Shamian, J., Buchan, J., Hughes, F., North Jones, N., Laschinger, H., North, N. (2012). Nurse turnover: A literature review – An update. International Journal, 49(7), 887–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.001

- Henderson, A., Ossenberg, C., & Tyler, S. (2015). ‘What matters to graduates’: An evaluation of a structured clinical support program for newly graduated nurses. Nurse Education in Practice, 15(3), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2015.01.009

- Kim, H., & Kim, E. G. (2021). A meta‐analysis on predictors of turnover intention of hospital nurses in South Korea (2000–2020). Nursing Open, 8(5), 2406–2418. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.872

- Klimstra, T. A. (2012). The dynamics of personality and identity in adolescence. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.673266

- Klimstra, T. A., Luyckx, K., Hale, W. A., Frijns, T., van Lier, P. A. C., & Meeus, W. J. (2010). Short-term fluctuations in identity: Introducing a micro-level approach to identity formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(1), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019584

- Kroger, J. (2003). What transits in an identity status transition? Identity, 3(3), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532706XID0303_02

- Kunnen, E. S. (2012). A dynamic systems approach to adolescent development. A dynamic systems approach to adolescent development. London: Routledge Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203147641

- Kunnen, E. S. (2019). Identity development from a dynamic systems perspective. In E. S. Kunnen, N. M. P. de Ruiter, B. F. Jeronimus, & M. A. E. van der Gaag (Eds.), Psychosocial development in adolescence: Insights from the dynamic systems approach (pp. pp146–159). Routledge.

- Kunnen, E. S. (2022). The relation between vocational commitment and need fulfillment in real time experiences in clinical internships. Identity, 22(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1932899

- Kunnen, E. S. (2023). The role of emotional experiences in commitment development in internship students. Identity, 23(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2023.2235392

- Lee, E., & Jang, I. (2020). Nurses’ fatigue, job stress, organizational culture, and turnover intention: a culture-work-health model. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945919839189

- Luyckx, K. (2006). Identity formation in emerging adulthood. Developmental trajectories, antecedents, and consequences. Catholic University of Leuven.

- Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., & Soenens, B. (2006). A developmental contextual perspective on identity construction in emerging adulthood: Change dynamics in commitment formation and commitment evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.366

- Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2006). Unpacking commitment and exploration: Preliminary validation of an integrative model of late adolescent identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 29(3), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.03.008

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 118–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

- Nogueiras, G., Kunnen, E. S., & Iborra, A. (2017). Managing contextual complexity in an experiential learning course: A dynamic systems approach through the identification of turning points in students’ emotional trajectories. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00667

- OECD. (2019). Health at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. Derived fromhttps://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en

- Parry, J. (2008). Intention to leave the profession: Antecedents and role in nurse turnover. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04771.x

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Steinkrauss, R. (2016). DST functions: Excel add-in for sampling and Monte Carlo functions. http://www.let.rug.nl/sldmethods/

- Ten Hoeve, Y. Brouwer, J., Roodbol, P. F., & Kunnen, S. (2018b). The importance of contextual, relational and cognitive factors for novice nurses’ emotional state and affective commitment to the profession. A multilevel study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(9), 2082–2093. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13709

- Ten Hoeve, Y., Kunnen, E., Brouwer, J., & Roodbol, P. (2018a). The voice of nurses: Novice nurses’ first experiences in a clinical setting. A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7–8), e1612–e1626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14307

- Turner, C. O. (2020). Stress over the life course: A qualitative analysis of graduate students’ stress and commitment during the graduate career [ doctoral dissertation]. Indiana University. Derived from https://www.proquest.com/openview/a2039d1ba156237962b58ed7f6a0d859/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=44156

- Van der Gaag, M. A. E. (2017). Understanding processes of identity development and career transitions [ doctoral dissertation]. University of Groningen.

- Van der Gaag, M. A. E. (2023). A person-centered approach in developmental science: Why this is the future and how to get there. Infant and Child Development, September, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2478

- Van der Gaag, M. A. E., & Kunnen, E. S. (2013). RECS-E: Repeated Exploration and Commitment Scale in the Domain of Education. Unpublished research instrument. Available on request to authors.

- Van Geert, P. L. C., Steenbeek, H. W., & Kunnen, E. S. (2012). Monte Carlo techniques: Statistical simulation for developmental data. In E. S. Kunnen (Ed.), A dynamic systems approach to adolescent development (pp. 43–51). Routledge.

- WHO. (2020). State of the world’s nursing 2020: Investing in education, jobs and leadership. World Health Organization. Derived from. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

- Zhang, Y., Qian, Y., Wu, J., Wen, F., & Zhang, Y. (2016). The effectiveness and implementation of mentoring program for newly graduated nurses: A systematic review. Nurse Education Today, 37, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.11.027