Abstract

Public–private partnerships (PPPs) are a popular way to form synergies between public and private partners in order to overcome modern challenges and develop new opportunities. However, recent research suggests that PPPs entail more risks than other projects. In this systematic literature review, we analyze 159 articles published in international journals and identify eight major risk factors in PPPs. We integrate our results into a risk management framework and examine how the risk factors potentially impact PPPs before summarizing risk mitigation strategies. Our findings offer a cross-sectoral perspective and bridge the gap between research and practical implementation. By developing a novel conceptual model we advance the understanding of risks in PPPs and contribute to the theoretical foundations.

Introduction

The cross-sectoral cooperation between private and public institutions has become an important element in facing the increasing demands from society (van Ham & Koppenjan, Citation2001). Today, PPPs enjoy great popularity in developed as well as developing countries. The OECD (Citation2012), for example, reports a value of 645 billion USD for PPPs between 1985 and 2009. In the European Union, 1,184 PPP projects have reached financial close between 2000 and 2015 (Tomasi, Citation2016). PPPs have become an inevitable part in realizing projects in many countries (Warsen et al., Citation2018) and offer several advantages for both public and private partners. They allow public partners to increase effectiveness (Pinz et al., Citation2018), to gain access to private financing, to import management expertise (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Citation2011) or to implement cost-saving mechanisms (Kwak et al., Citation2009). Private partners, in return, can share or shift risks and get access to public projects they could not sustain otherwise (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Citation2011). Nevertheless, PPPs also have their drawbacks. Partners pursue different interests when they engage in PPPs (Pinz et al., Citation2018) and PPPs might have more and a higher degree of risks than other projects (Bloomfield, Citation2006; Carbonara et al., Citation2015; Grimsey & Lewis, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2018).

There already exists a vast body of literature investigating risks in PPPs. There is a large volume of case studies, but also a great number of quantitative and qualitative empirical studies and even some literature reviews. However, these articles have mainly focused on specific cases, sectors, scientific disciplines, factors or countries. For example, Carbonara et al. (Citation2015) focus their review on motorways, Bel et al. (Citation2013), Leruth (Citation2012), and Zimmermann and Eber (Citation2014) concentrate on infrastructure development, construction or transportation, and the reviews of Roehrich et al. (Citation2014), Torchia et al. (Citation2015) or Hellowell (Citation2016) investigate the health-care sector. A recent study by Wang et al. (Citation2018) reviews only articles published in international public administration journals and other studies are restricted to a specific area or country, such as Chou and Pramudawardhani (Citation2015) who focus on Taiwan, Singapore, China, the United Kingdom, and Indonesia. Furthermore, several studies explore particular factors. For example, Warsen et al. (Citation2018) examine relational aspects like trust, Becker and Patterson (Citation2005) concentrate primarily on financial returns and risks as well as the roles of partners, and Sarmento and Renneboog (Citation2016) investigate the structure, financing and renegotiation of PPPs.

Thus, although a vast body of literature is already available, to date there exists no overarching overview that synthesizes risk factors that are relevant to all PPPs regardless of the actual project or sector. Therefore, our article aims to fill this gap by identifying generic risk factors, relating them to elements of current risk management frameworks and establishing a conceptual model. Our study is guided by three core questions: (1) What are the most important risk factors in PPPs?; (2) What impact do those factors have on PPPs?; (3) How can we mitigate those risks in PPPs? In order to answer these questions, we conducted a systematic literature review and investigated 1,331 articles, of which 159 papers formed the basis for our in-depth analysis. Based on a thorough content analysis we identified several risk factors. In the development of these factors, we deliberately refrained from falling back on current theories, their terminology, and their definitions to avoid confounding effects.

This study contributes to research and managerial practice in several ways: first, by presenting a literature review on the risks of PPPs that is not restricted to particular sectors, we provide an overarching, cross-sectoral overview of generic risk factors that can serve as a starting point for future research or for the practical implementation of PPPs, particularly for those cases and sectors where concrete experiences are currently missing. Second, by relating our findings to risk management frameworks our study goes beyond existing review articles and allows the gap to be bridged between theoretical findings in research and the utilization of these findings in the management of PPPs. In that regard, our findings can serve as a strong basis and checklist for practitioners in PPPs during the iterative risk management process. Third, by developing a novel conceptual model we advance the understanding of risks in PPPs and contribute to the theoretical foundations. We furthermore offer valuable suggestions for a future research agenda.

Theoretical background

Types of PPPs

In this article, we define PPPs as cooperative arrangements between public and private partners to share resources, risks, responsibilities and rewards to mutually gain social, economic, or environmental objectives (Kwak et al., Citation2009). However, today there exist several types of PPPs and a multiplicity of different terms. PPPs can be distinguished by their degree of private involvement, such as BOT, DBFO, BOOT, DBFOM, and BOO1 (Kwak et al., Citation2009; Roehrich et al., Citation2014; Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016). We can also observe country-based forms and terms (Barlow et al., Citation2010; Ke et al., Citation2009) such as “private finance initiative” (e.g., especially used in the UK; Shaoul, Citation2005) or “private infrastructure involvement” (e.g., Australia; Wettenhall, Citation2003). And we can even identify sector-specific applications like the “accommodation-only model” for building and managing facilities and services in the health-care sector (Barlow et al., Citation2013). Additionally, the use and definition of these terms have changed over time (Ke et al., Citation2009). Therefore, today’s PPP literature is highly ambiguous when it comes to types and terms and the only constant we have is that most authors acknowledge and label such partnerships between private and public institutions with the overall (umbrella) term “PPP.”

Theoretical foundations related to PPP research

In this study, we wanted to discover new insights about generic risk factors in PPPs exclusively from the data we retrieved. In fact, we explicitly avoided using existing theories and their definitions for the development of our factors and subfactors. Therefore, we will keep this section short and discuss our findings in relation to existing theories in the discussion section. However, several theories are used in recent research to analyze and study PPPs. Wang et al. (Citation2018) identify in their literature review three different types of knowledge backgrounds in PPP research: first, theories with economic backgrounds such as the transaction cost theory, property rights theory or principal-agent theory; second, theories with a public management or policy background, such as network and governance theories, public choice theory, and New Public Management (NPM); and third, theories with an organizational management background such as stakeholder theory or institutional theory. Obviously, researchers from different fields have diverse perspectives on the subject and, similarly to other cross-sector collaborations research, need to bridge these different perspectives to cope with the complex challenges and risks that are inherent to such collaborations (Bryson et al., Citation2006).

Risk management

Some authors assume that PPPs have more and a higher degree of risks than other projects because they involve many stakeholders, entail complex project arrangements, may have special rules regarding financing, documentation and taxation, or lack experienced partners (Bloomfield, Citation2006; Carbonara et al., Citation2015; Grimsey & Lewis, Citation2002; Wang et al., Citation2018). In general, risk is the “effect of uncertainty on objectives”. This rather technical definition is provided by the International Organization for Standardization (Citation2018). In other words, risks are uncertain (expected or unexpected) possibilities, opportunities or threats that might happen (Wang et al., Citation2018). They are inherent to all projects and therefore proper management is required to systematically identify, analyze, and respond to risks throughout the whole project (Wang et al., Citation2004). Risk management is defined as a formal process of “coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk” (International Organization for Standardization, Citation2018) and is considered as an iterative process (Chinyio & Fergusson, Citation2003).

A number of authors have established different risk management frameworks in the context of PPPs. Zou et al. (Citation2008), for example, propose a life-cycle risk management framework which emphasizes the dynamic process for allocating and monitoring risks in all stages. Fischer and Porath (Citation2010) developed an integrated risk management system to cover different perspectives of the stakeholders involved. Wang et al. (Citation2004) identified three main stages of risk management: (1) risk identification of relevant and potential risks, (2) risk analysis and evaluation of the potential impact; and (3) risk response in order to formulate suitable risk treatment strategies or mitigation measures. Based on Steele (Citation1992), Chinyio and Fergusson (Citation2003) proposed similar steps in their risk management framework for PPPs:

Risk identification: the first step is to identify the risks facing a project. There are several strategies for risk identification, for example based on personal and corporate experience, intuitive insights, brainstorming, research, interviews and surveys, or through consultation with experts.

Risk evaluation: the next step is to evaluate the consequences if a risk materializes. This task is twofold—it attempts to estimate the probability by which a risk might occur and to assess its impact on the project should it actually happen. There are several strategies how to assess risks. One way is to evaluate every risk via its probability, another is to assess only the main risks and to concentrate on key issues. The impact on PPPs can be financial or could result in other issues, such as delays or decreased quality of output.

Risk mitigation: the last step is about finding solutions to counter those risks. Risk elimination refers to actions taken to avoid risks, risk reduction is about the minimization of risks, risk transfer means transferring risks to insurances or specialists, risk retention is about risks being absorbed by the organization.

In the subsequent sections, we interrelate our findings on risks in PPPs with these three steps.

Method

To answer our research questions, we implemented a systematic literature review and followed the guidelines of Tranfield et al. (Citation2003) and Denyer and Tranfield (Citation2010). The authors highlight key aspects for applying a systematic literature review in the fields of management and organization. The review process includes several steps, which are described below. A visual overview is provided in the Supplemental online material (A).

In the first step, the procedure started with a database search in EBSCO Business Source Premier in January 2017. The time frame for the database search was determined as 2000 to 2016. Our search included only peer-reviewed papers published in English. We used the search terms “public private partner*,” “public-private partner*,” “PPP*,” “private public partner*,” and “private-public partner*” and included papers in which those terms were presented in the title or in keywords. As already discussed in the previous section, there exists a multiplicity of different terms and types of PPPs, which change over the course of time or vary between countries and even sectors. To counteract this ambiguity, we refrained from considering only a selective choice of PPP subtypes and instead used exclusively the widely recognized umbrella term “PPP.” The result of the database search implied 1,839 papers, after eliminating duplicates 1,331. Thereafter, we eliminated papers which referred to other topics like “purchasing power par*” or “public procurement procedur*,” leaving 1,104 papers.

In a second step, we selected and evaluated the literature. We, therefore, developed a set of seven exclusion criteria to allow the assessment of each study. First, we excluded articles from the review in the rare case of the document not being accessible. The second exclusion criterion concerned the scientific approach of the papers—we excluded, for example, book reviews or any kind of nonscientific articles. Third, we eliminated those studies that did not contain PPP as the research topic despite our applied search terms. The fourth and fifth exclusion criteria were whether a paper dealt with developing countries or nonprofit organizations. Recent research suggests that there are considerable differences regarding the requirements and risks of PPPs in developing and developed countries (Osei-Kyei & Chan, Citation2017; Urio, Citation2010). Similarly, research in the field of nonprofit management indicates distinct and substantial differences to profit-oriented organizations. The sixth and seventh exclusion criteria were applied when papers did not include risks or when those risks did not refer to PPPs themselves. As suggested by Tranfield et al. (Citation2003), two reviewers evaluated the studies independently and then compared their findings. After applying the seven exclusion criteria, 159 papers remained and as basis for the in-depth analysis.

In a third step, the reviewers independently used data extraction sheets to analyze all articles identified. The reviewers continually compared their results; in case of disagreement, the opinion of an additional reviewer was decisive. Each data extraction sheet consisted of the following elements: bibliographic data (e.g., author, title, year, journal), method (e.g., quantitative studies, qualitative studies), sector (e.g., infrastructure, health, urban development), country, risk factors. In our analysis, we combined deductive (deductive category application; see Mayring, Citation2000) and inductive methods (inductive category development; see Mayring, Citation2000) to derive our risk factors/subfactors. (For more information about different approaches to qualitative content analysis see also the thorough overview by Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005)). We started with risk factors that have been suggested by other authors, for example, Carbonara et al. (Citation2015), who provide a list of risks in motorway PPPs. We also drew on related literature that refers to other sorts of collaborations—for instance, CitationAnkrah and Al-Tabbaa (2015), who investigated university–industry collaborations. We used this initial list of factors and iteratively adjusted it, adopting, adding, and eliminating individual factors in a process of refinement involving continual discussions between the authors. During the analysis, we developed an interpretation guide, which we used to determine whether a paper’s content could be subsumed under a particular factor. This led to the modification of some factors and to the addition and deletion of others. To increase the readability and enhance the understanding of the nature and substance of the actual factors, we structured them into subfactors. We derived these subfactors via an inductive approach. We started by iteratively clustering similar text passages from our analysis to identify relevant facets and aspects within each risk factor. Then, we renamed the subfactors, ensuring that each term reflected the character of the condensed text passages appropriately.

In a fourth step, we synthesized our findings and combined them with risk management of PPPs. More precisely, we used the synopsis of our quantitative and qualitative analyses to assess the relevance of the respective risk factors and then related the most important factors with the three steps of our risk management framework, namely risk identification, risk evaluation, and risk mitigation. Regarding the identification phase, we provide an overview of the identified generic risk factors, with respect to the evaluation phase, we report potential consequences if these risks materialize and in terms of the mitigation phase, we synthesize risk mitigation strategies.

Results

The analyzed papers were published in 92 different journals; about 60% of the papers were published in journals with an impact factor (IF). In the Supplemental online material (B) we provide an overview of the journals, the number of articles published in these journals and their impact factors. The key publication outlets are International Journal of Project Management (10 articles), Journal of Construction Engineering and Management (9), Public Performance & Management Review (7) and Public Works Management & Policy (7). Most articles investigate PPPs based in the United Kingdom (50), the United States (42), Australia (26), the Netherlands (18), and Canada (11). We assigned an article to a country according to the origin of the PPP. Our results indicate that PPPs are particularly popular in Anglophone countries. Of the 159 investigated articles, 76 articles included case studies, which points to the practical relevance of the topic and the still emerging nature of the field. Lastly, the number of papers rose over the last decades, which indicates the increasing relevance of the investigated topic in recent years. The number of publications per year can be found in the Supplemental online material (C).

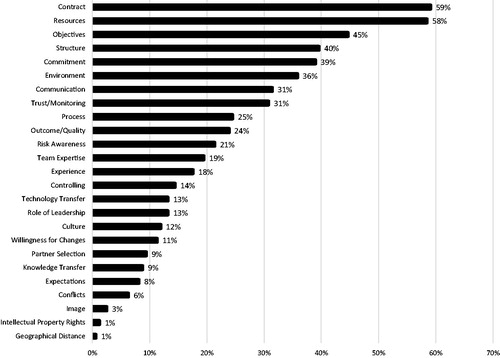

depicts how many studies named each of the factors as relevant, which does not necessarily mean that this factor was the actual focus of the respective study. The most often named factors are contract (59%), resources (58%), objectives (45%), structure (40%), commitment (39%), environment (36%), communication (31%), and trust (31%). Below, we report these eight factors and relate them with risk identification, evaluation, and mitigation.

Contract

Contracts are binding agreements between cooperating partners and are an essential component of any project (Soliño & de Santos, Citation2010). The examined studies show that issues regarding contracts represent one of the greatest challenges in PPPs. Our analysis reveals three main contractual risks, namely negotiation, incompleteness, and contractual design.

Identification: Potential issues in the context of negotiations refer to the duration of negotiations (Zervos & Siegel, Citation2008; Zhang, Citation2005b), insufficient processes for getting a contractual agreement (Chung, Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2005b), asymmetric information flow and imperfect information (Parker & Hartley, Citation2003; Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016). Incompleteness poses another major challenge regarding contracts in PPPs (for example, Alam et al., Citation2014; Landow & Ebdon, Citation2012; Soliño & de Santos, Citation2010). In long-term partnerships, contractual arrangements need to cover a long period and it is not possible to define a “complete” contract considering all relevant aspects and future incidents (for example, Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016; Siemiatycki & Farooqi, Citation2012; Wang, Citation2015). Contractual design is the third critical aspect of PPP contracts (Marques & Berg, Citation2011; Nisar, Citation2007b) and includes contractual ambiguities (Byoun & Xu, Citation2014), an absence of flexibility to allow changes (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006), lacking details (Soomro & Zhang, Citation2016) or missing transparency of contractual contents (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006).

Evaluation: In sum, 94 of the 159 analyzed papers dealt with the risk factor contract. The probability that issues arise in this context seems high. Which impacts are discussed in literature? Negotiations and, at a later stage, renegotiations are time-consuming and result in high costs (Ahadzi & Bowles, Citation2004; Siemiatycki & Farooqi, Citation2012), delays within the project and conflicts between partners (Zervos & Siegel, Citation2008). Vague or incomplete contracts lead to unclear distribution of tasks and responsibilities (Soomro & Zhang, Citation2016), endanger the financial commitment (Bettignies & Ross, Citation2009) and often cause renegotiations between partners (Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016). However, complex and detailed agreements have their drawbacks too and result in immense contractual conditions with disorganized and confusing information (Leruth, Citation2012).

Mitigation: In order to mitigate contractual risks, we found several strategies in the investigated literature. A planned and staged negotiation procedure can assist in finding suitable partners, identifying and managing risks, and finalizing an agreement on time (Forrer et al., Citation2010). Similarly, a renegotiation procedure for contract extensions or adjustments is advisable (Xiong & Zhang, Citation2014). One mitigation strategy to cope with incompleteness and to deal with changing circumstances is contractual flexibility (Domingues & Zlatkovic, Citation2015). In this regard, Zheng et al. (Citation2008) suggest establishing yearly contractual changes because planning too far ahead is time-consuming. To prevent failure in contract design, the development of guidelines with formal components for contracts is another mitigation strategy (for example, Abdel & Ahmed, Citation2007; Fourie & Burger, Citation2000). For instance, the case of a M4 motorway PPP in Australia has demonstrated that the nonexistence of formal guidance was challenging for the conclusion of the contract and led to contract ambiguities (Chung, Citation2016). Furthermore, the design of contracts requires detailed information regarding the expectations of partners (Forrer et al., Citation2010), clarified responsibilities (Landow & Ebdon, Citation2012), space for flexibility (Forrer et al., Citation2010; Parker & Hartley, Citation2003), clear lines of communication between partners (Liu & Wilkinson, Citation2014), cost transparency and risk allocation (Nisar, Citation2007b; Zhang, Citation2005a), renegotiation clauses (Domingues & Zlatkovic, Citation2015), and procedures for conflicting situations as well as exit strategies (Parker & Hartley, Citation2003).

Resources

Resources in PPPs are assets that are essential for cooperation in forming synergies between partners to overcome challenges and develop new opportunities that neither of them could create alone (Alam et al., Citation2014; Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Citation2011). In our analysis, we identified three main resource-based risks, namely finance, staff and time issues.

Identification: According to financial issues, cost overrun due to poor initial cost estimates is one of the main challenges (for example, Nisar, Citation2007a; Roumboutsos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2008; Zhang & Soomro, Citation2016). Potential reasons might lie in the financial complexity of PPPs (Zhang, Citation2005b). The availability of resources is another challenging point due to the fact that private partners are often left alone to deal with the capital procurement and other resource acquisitions (Wang, Citation2015). Regarding staff, the quality and availability of staff is an important risk for PPPs (for example, Roumboutsos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2008; Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Trojanowski, Citation2013). Staff without experience of a certain type of work or of working together as a team can harm a project (Waring et al., Citation2013). With regard to time, public and private partners’ different time horizons can create problems in PPPs (Ruuska & Teigland, Citation2009; van Ham & Koppenjan, Citation2001), e.g., private partners often focus on short-term perspectives with profit maximization, whereas public partners are more interested in long-term investments rather than fast cash creation (van Ham & Koppenjan, Citation2001).

Evaluation: In our analysis, 93 of 159 articles dealt with the risk factor resources and its sub facets. This result indicates that incidents regarding resources are likely to occur. Insufficient cost estimates, for example, endanger those parties who provide financial resources when the predicted revenues do not materialize (Grimsey & Lewis, Citation2002). Control mechanisms to monitor the allocation of resources restrict the freedom and autonomy of partners in managing their own assets (Kakabadse et al., Citation2007). Unqualified staff can induce poor-quality outcomes and may lead to staff crises (Bing et al., Citation2005). Different time horizons perhaps result in delays due to complex planning and negotiation processes (Nisar, Citation2013).

Mitigation: We identified different mitigation strategies for resource risks. Regarding financial issues, it is important to pay attention to the early stages of a partnership, where financial analysis and administration are discussed in detail (Kakabadse et al., Citation2007). A regular control according to the standards of the OECD and other organizations for economic collaboration ensures the reliability and transparency of resource management in PPPs (Biginas & Sindakis, Citation2015). In this vein, Vining and Boardman (Citation2008) claim that only clear and consistent budget reporting can increase transparency concerning financial resources. With regard to staff, partners can support each other in terms of recruiting, keeping the right people, consulting internal experts or referring to external advisors (Liu & Wilkinson, Citation2014), as well as through regular and individualized workforce training and permanent education (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006). Concerning time delays and different time horizons, a detailed time schedule, milestones, and fixed deadlines help to stay on schedule. Some PPPs typically determine penalties for late project completion or provide incentives for on-time delivery (Davis, Citation2005). The relevance of the identified strategies also can be seen in the case of a PPP school-based learning opportunities project, in which partners continuously neglected plans and underestimated the time required, which led to delays of the whole project (Nisar, Citation2013).

Objectives

Objectives refer to the strategies, visions, goals or plans of the PPPs and their expectations about the quality of the project outcome. We identified conflicting goals, problems with strategy and a lack of clarity as important risks in terms of objectives.

Identification: Several studies (for example, Páez-Pérez & Sánchez-Silva, Citation2016; Rangel & Manuel Vassallo, Citation2015) claim that conflicting goals are main risks of PPPs. The private sector aims to maximize profit, create short-term revenues, and decrease costs for firms and individual shareholders, while the public sector aims to create jobs and increase public services from a long-term perspective (Ruuska & Teigland, Citation2009). A second stream of risks refers to the strategy of public and private partners. Due to partners’ different perspectives on attaining their individual goals, the approach to reaching mutual goals is diverse (for example, Tunčikienė et al., Citation2014). The partners’ heterogeneous background makes it often challenging to achieve a good balance of interests (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Citation2011). Another problem concerning objectives is the lack of clarity about goals and strategies (Weihe, Citation2008). This aspect refers to the uncertainty about the expected outcome (Cruz & Marques, Citation2013), unclear goal setting (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006) or unclear policies (Sarmento & Renneboog, Citation2016).

Evaluation: In our systematic literature review, 71 out of 159 papers dealt with the risk factor objectives. Different and diverging goals can lead to conflicts between partners, misinterpretations, asymmetric flows of information and a lack of commitment (Robinson & Scott, Citation2009; Vining & Boardman, Citation2008). PPPs may face a standstill or even fail when project goals are not mutually agreed upon or partners have a different prioritization of objectives (Koppenjan, Citation2005; Meidutē & Paliulis, Citation2011). Different mindsets, perspectives, and cultures of the collaborating partners (Liu & Wilkinson, Citation2014) lead to conflicts and result in partners following their own strategy (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006).

Mitigation: We observed three main mitigation strategies. One of the most frequently mentioned is simply to be aware of conflicting goals and to understand that different goals, interests, and perspectives may arise (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006; Vining & Boardman, Citation2008). In this regard, it is important to understand the individual goals of each partner by “forcing” them to clearly communicate their goals (Ruuska & Teigland, Citation2009). A second mitigation strategy is to avoid strategy conflicts by making sure that a common vision is communicated and maintained by the partners and by setting milestones and assuring regular negotiations (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006). A strategic development model supports setting up an agreement of all goals, values, assets and management activities (Grossman, Citation2010). This leads us to the third mitigation strategy. Contracts play an important role in mitigating problems regarding objectives and their clarity. A proper contractual agreement, in which all goals and the strategy on how to achieve these goals are clearly stated, helps to prevent conflicts (Domingues & Zlatkovic, Citation2015; Rangel & Manuel Vassallo, Citation2015).

Structure

Structural aspects refer to the question of how PPPs are organized and built and how partners work together in an efficient way. Regarding structure, we identified three main risks: roles and responsibilities, decision-making, and coordination.

Identification: Unclear or insufficient allocation of roles and responsibilities between cooperating partners is a major risk for PPPs (for example, Chou & Pramudawardhani, Citation2015; Dubini et al., Citation2012; Jacobson & Choi, Citation2008). Project partners have to carry out different roles and responsibilities at the same time, which can create difficulties (van Ham & Koppenjan, Citation2001), especially when some of those roles are not clearly defined (Anderson et al., Citation2012; Becker & Patterson, Citation2005). Several authors emphasize that decision-making in PPPs is a problematic issue (Chou & Pramudawardhani, Citation2015; Klijn & Teisman, Citation2003; Torchia et al., Citation2015). This includes the complexity or insufficient advancement of decision-making processes (Roumboutsos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2008), different strategies or divergent expectations of partners, the lack of a harmonized process (Petersen, Citation2011) and the inadequate integration of project members in these processes (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006). Coordination risks refer to poor coordination of partners (Zhang, Citation2005b), a lack of coordination (Zhang & Soomro, Citation2016), a lack of transparent structures (Bloomfield, Citation2006), and to issues caused by the differences regarding the organizational and managerial structures (Steijn et al., Citation2011).

Evaluation: Our results show that 63 out of the 159 analyzed papers dealt with the risk factor structure. Unclear roles and responsibilities induce unfair distribution of power, which negatively affects the implementation and vision of a partnership (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006). Moreover, when there is a lack of clear lines of authority or when there is no clear allocation of tasks and responsibilities, no one feels responsible for deadlines or budgets (Little, Citation2011; Roumboutsos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2008). Furthermore, a lack of coordination negatively influences the progress of PPPs (Soomro & Zhang, Citation2016) and causes inefficiently used or wasted resources (Zhang, Citation2005a).

Mitigation: To mitigate structural issues, the following strategies are recommended in the investigated literature. One mitigation strategy refers to clearly defining roles and responsibilities within the PPP, ideally right at the beginning of the partnership (for example, Alam et al., Citation2014; Anderson et al., Citation2012; Dubini et al., Citation2012). An important aspect is that the allocation of responsibilities has to involve all hierarchical levels (O’Hara et al., Citation2014). In this context, the analysis of three community PPP projects showed that the focus on democratic and participative approaches helped to enable more open discussions and to build trust (Nisar, Citation2013). Furthermore, clear regulation will help to specify each other’s roles and responsibilities (Chung & Hensher, Citation2015). Another mitigation strategy is the development and implementation of appropriate decision-making structures (Currie & Teague, Citation2015). Here, central authorities can assist in the development of a common vision of the cooperation, to define and regulate milestones and to facilitate regular negotiations and decision-making mechanisms (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006). Furthermore, a clear framework including milestones, targets, and rules that increase the transparency of a project can mitigate the risks (Meidutē & Paliulis, Citation2011). However, partners must plan the defined elements to be as realistic as possible and need to monitor and evaluate them constantly (Nisar, Citation2013).

Commitment

Commitment refers to the question of how much individuals identify with the PPP and its goals, how loyal these individuals are to the PPP and whether they are willing to put sufficient effort into it. In our analysis we recognized risk factors concerning the identification with the project and regarding the engagement of the partners.

Identification: When partners do not identify themselves with the PPP, major challenges can arise and a negative attitude or pessimistic behavior might be the consequence (Soomro & Zhang, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2015; Weihe, Citation2008). Fourie and Burger (Citation2000) also argue, partners may have an incentive to run a PPP only to serve their own interests before meeting the stated mutual objectives. Our second subfactor refers to the engagement of the partners. Risks regarding this aspect are, for example, a lack of motivation (Parker & Hartley, Citation2003), an unwillingness to collaborate (Monios & Lambert, Citation2013; Zhang, Citation2005b), or a reluctance to take risks or to invest (Monios & Lambert, Citation2013). The involvement and participation in the strategic process and during the whole project are important in this context (Koppenjan, Citation2005) and a lack of commitment will have an immense negative influence on the whole project.

Evaluation: In sum, the risk factor commitment is discussed by 62 out of 159 papers. Even when both partners are committed to the PPP at the beginning, they may feel distant after a while and unwilling to collaborate further (Klijn & Teisman, Citation2003). During the course of the project, motivation can decrease if partners use benefits only for their own purposes (Wang, Citation2015). A lack of trust and commitment in a PPP can also impede knowledge transfer, innovation, or the development of new skills (Fischbacher & Beaumont, Citation2003). Furthermore, partners tend to follow their own strategies and pay less or no attention to the other partners’ business if they are not in some way involved (Edelenbos & Klijn, Citation2007). Another impact of missing commitment is uncertainty about the partners interests and preferences (Ni, Citation2012).

Mitigation: To mitigate commitment issues in a PPP, partners should establish stable framework conditions that offer enough freedom for both partners and determine incentives and rules for collaboration (Brinkerhoff & Brinkerhoff, Citation2011; Weiermair et al., Citation2008). A high willingness to compromise and to collaborate is essential to enhance commitment and should be guaranteed through shared values and goals along with open communication (Jacobson & Choi, Citation2008). Within the contract, rewards and even penalties can be appropriate and function as incentives for services to be delivered on time (Nisar, Citation2013). Additionally, given the complex nature of a PPP, managers have to work together collaboratively, especially when certain circumstances change (Heurkens & Hobma, Citation2014).

Environment

The definition of environment in our analysis is based on factors externally influencing PPPs. These risks cannot—or can only partially—be influenced by the PPP partners. We identified the following environmental risks: political risks, demand/revenue risks, risks related to a competitive environment and unpredictable incidents.

Identification: Regarding political risks, unstable governments (for example, Currie & Teague, Citation2015; Little, Citation2011), legal risks (for example, Oblak et al., Citation2013), political uncertainty (Durand et al., Citation2015; Wang, Citation2015), lack of political support (Jacobson & Choi, Citation2008; Zhang, Citation2005b), a poor regulatory framework or governmental restrictions (Zhang, Citation2005b) are mentioned in the analyzed literature. Another environmental risk refers to demand or revenues. Researchers report low ridership, a decreasing number of students attending schools or universities, or the unsatisfying actual use of a certain infrastructure project (Leruth, Citation2012; Reeves, Citation2003; Siemiatycki & Friedman, Citation2012). An additional environmental risk is the competitive environment. For example, problems can arise in the PPP when (private) competitors get too strong and the capital market is weak (Zhang, Citation2005b). Further issues that can occur in PPPs are unpredictable incidents such as geotechnical conditions (Roumboutsos & Anagnostopoulos, Citation2008), extreme weather conditions (Little, Citation2011), natural and unavoidable catastrophes (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Trojanowski, Citation2013), terrorism and war (Little, Citation2011) or force majeure (Clifton & Duffield, Citation2006).

Evaluation: According to our analysis, 57 out of 159 papers dealt with the risk factor environment. For some PPPs, the political risk is most important, because the project stands and falls with changes in law affecting PPPs (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Trojanowski, Citation2013). This political risk often results in a reestablishment of conditions and agreements in the PPP contract (Byoun & Xu, Citation2014; Heurkens & Hobma, Citation2014). Unrealistic demand forecasts can lead to tension between partners and to legal conflicts (Siemiatycki & Friedman, Citation2012), and sometimes demand risks require additional negotiation efforts between partners (Carbonara et al., Citation2015). Some PPPs might fail due to a monopolistic situation or the nature of the private sectors’ competitive environment (Zervos & Siegel, Citation2008).

Mitigation: The success of PPPs strongly depends on the environment in which the projects operate, and often certain circumstances cannot be influenced by the partners but by the government. Government authorities can support PPPs by developing an adequate legal framework for them and by attracting private investors with good social and economic conditions (Zhang, Citation2005b). The government furthermore needs to guarantee that the legal status of the PPP is consistent during the project duration. Hence, one mitigation strategy is to gain support and commitment from stakeholders and the government through committee meetings, detailed reports or tours for council members, and external communication with stakeholders (Jacobson & Choi, Citation2008). Risks regarding the competitive environment and demand can be minimized by looking for private enterprises or partners with experience in given market (Weiermair et al., Citation2008). Unpredictable risks can be mitigated through proper calculations and advance analysis that include the economic, financial, legal and political complexities of such events (Caselli et al., Citation2009). Nevertheless, partners will never foresee all possible situations and stakeholder actions.

Communication

Communication is the act of transmitting the right information to the right person at the right time. We identified three main risks regarding communication, namely the interaction between partners, shared information, and communication at the right time.

Identification: Interaction barriers include the lack of communication (Anderson et al., Citation2012; Koppenjan, Citation2005), the intensity of interaction (Weihe, Citation2008), the complexity of communication processes (Páez-Pérez & Sánchez-Silva, Citation2016) and the lack of interpersonal communication (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006). Risks regarding shared information refer to information asymmetry (Ni, Citation2012), the handling of confidential information (Vonortas & Spivack, Citation2006) and the quality of information flow (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Trojanowski, Citation2013; Zheng et al., Citation2008). Moreover, differences in language, culture or power may pose the risk of the right information not being at the right place for the right person (Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006). Risks concerning communication at the right time often refer to the initial phase of a PPP. Especially at the beginning, before the contracts are signed and the working phase starts, partners might not focus sufficiently on communication (Murphy et al., Citation2016).

Evaluation: Of the analyzed papers, 50 of 159 articles referred to communication as a risk factor. Communication risks have several negative impacts. A lack of communication and close interaction with strong links between the partners can impede knowledge sharing (Nissen et al., Citation2014). If there is no open communication between the partners, difficulties in understanding each other and problems in reaching a satisfying agreement may arise (Jacobson & Choi, Citation2008). If communication rules are not embedded in the organizational structure, the consequences can be unstructured information with conflicting ideas and expectations (Koppenjan, Citation2005). Moreover, poor communication can negatively influence trust (Fischbacher & Beaumont, Citation2003), hinder the ability to react adequately to unforeseen situations or impact the commitment to the PPP (Domingues & Zlatkovic, Citation2015).

Mitigation: One mitigation strategy to foster the sharing of information and the interaction between partners is to establish frequent communication, for example, through weekly meetings or regular exchange (Monios & Lambert, Citation2013; Nisar, Citation2007b). In the early stage of a partnership, the goals of a project are usually not clearly defined; therefore extensive interaction is required before partners reach a contract agreement (Murphy et al., Citation2016). In addition, there is also a need for communication through different channels, such as personal communication, meetings or e-mails (Forrer et al., Citation2010). Moreover, project partners have to establish an open and transparent communication (e.g., Ahadzi & Bowles, Citation2004; Li et al., Citation2005; Trafford & Proctor, Citation2006). In this context, trust can foster open communication (Fischbacher & Beaumont, Citation2003; Forrer et al., Citation2010), but building trust takes a long time and has to be continuously developed (Forrer et al., Citation2010). A mitigation strategy to handle information risks is the implementation of a regulatory framework to foster information exchange or information sharing between partners (Garcia Martinez et al., Citation2013). However, good communication among partners requires appropriate communication skills (Ni, Citation2012). Each partner has to know how best to communicate (Currie & Teague, Citation2015) and has to understand and promote their ambitions and interests (Fischbacher & Beaumont, Citation2003).

Trust

Trust is of particular interest to organizations because it can influence the business performance between partners (Lane & Bachmann, Citation1998). It is defined as an expectation by one partner of the acceptable behavior of the other partner (e.g., neither party will be exploited; Lane & Bachmann, Citation1998). In this analysis, three main risks related to trust could be found, namely monitoring, trust building and transparency.

Identification: We identified monitoring respectively control mechanisms as one of the most discussed issues regarding trust in PPPs (for example, Boyer, Citation2016; Chung, Citation2016; Fourie & Burger, Citation2000; Nisar, Citation2007a; Reynaers & Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2015; Robinson & Scott, Citation2009; Soomro & Zhang, Citation2016). In this context, some authors claim that the public sector does not always have enough monitoring capacity to ensure the right quality output (Nisar, Citation2007a). Another important issue refers to trust building. Trust building between public and private partners needs to be carefully implemented over time and is a long-developing process (Dubini et al., Citation2012; Kakabadse et al., Citation2007). However, too much trust can also be critical for the partnership if the relaxed attitude of partners is predominant and leads to situations in which trust turns into distrust (Edelenbos & Klijn, Citation2007). The third issue refers to a lack of transparency. Loosemore and Cheung (Citation2015), for example, state that if there is no trust established in a PPP project, confidential information exchange is not going to happen and therefore holistic thinking is absent (Loosemore & Cheung, Citation2015).

Evaluation: Our results show that 49 out of 159 papers covered the risk factor trust. Too much monitoring can erode trust and therefore put the whole project in danger (Grossman, Citation2012). As reported in a case by Siemonsma et al. (Citation2012), the monitoring process became an unnecessary burden and enforced penalties and bonus regimes that challenged the whole project. Furthermore, Weihe (Citation2008) notes that if the trust level decreases, the cooperation will become ineffective. That means, if trust cannot be built over time, information will not be shared sufficiently during the lifecycle of the project and the development of an effective cooperation is in danger (Zheng et al., Citation2008). A lack of transparency can impact the whole project and even if the partners force transparency in the PPP, the complexity causes uncertainty regarding several parameters especially if the responsible persons leave after contract closure (Reynaers & Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2015).

Mitigation: Trust building can be supported by supervising and careful auditing (Marques & Berg, Citation2011). In a case reported by Alam et al. (Citation2014), the sharing of information, a mutual understanding and formal and informal meetings supported the establishment of trust and an intangible network among the partners. Furthermore, mutual trust can reduce potential conflicts in PPPs (Alam et al., Citation2014). Another example of trust building is mentioned by Binza (Citation2008), where partners had to act with as much reliability as possible to ensure the project’s success. To support a transparent collaboration, open and honest communication as well as clear roles and responsibilities for all partners involved in the PPP are crucial (Forrer et al., Citation2010; O’Hara et al., Citation2014). In the case of Kakabadse et al. (Citation2007), the informal approach and honesty between the partners were important to successfully working together.

Based on our review, we identified the most important risk factors in PPPs and related those findings to risk identification, risk evaluation, and risk mitigation. A summary of our results is provided in . In the next section, we reflect on some results of our in-depth analysis and develop a conceptual model.

Table 1. Summary of the Main Results.

Discussion and conclusion

Connection to existing theories

Although this study is not built upon specific theories and terminologies, it is necessary to embed the results in the extant body of literature and relate the identified factors to existing theories.

In our study, we identified “contracts” as one of the most important risk factors. In this context, the contract theory introduced by Holmström and Hart (Citation1987) is particularly relevant. It refers to the optimal design of contracts and the behavior of the parties involved. This theory addresses the issue that individuals tend to satisfy their own needs rather than to contribute to mutually beneficial outcomes (opportunism). Our findings on the risks in contractual design, more precisely on missing transparency and inadequate risk distribution, provide additional evidence of this theory. As in Pandey et al. (Citation2018), the theoretical framework on social impact bond contracts draws upon Spiller’s transaction cost theory of regulation (TCR) (Spiller, Citation2010). This framework illustrates that in addition to moral hazards and adverse selection, public-private contracts also deal with governmental and third-party opportunism. In Pandey et al. (Citation2018) the illustration of standard opportunistic behavior, governmental opportunism and third-party opportunism is very instructive and shows overlaps with our results concerning contracts. In particular, our results on the incompleteness of contracts (e.g., because future conditions can change and are not entirely predictable) are related to this theoretical framework. Another standard opportunistic behavior, also mentioned in Pandey et al. (Citation2018), is transaction cost theory which focuses on the distribution of rights (Brousseau & Glachant, Citation2002). Our results on contracts show an interesting overlap with this theory because contract ambiguities and insufficient distribution of roles and rights are similarly indicated in our results. Concerning contract negotiation, the identified issue of insufficient process agreement seems strongly connected with the transaction cost economics theory (TCE). TCE refers to the inefficiency of contracts due to transaction costs (Williamson, Citation1989). Additionally, the problem of opportunism is still present and therefore transaction costs due to issues such as delays, fraud or asymmetric information flow can arise (Williamson, Citation1991). Another relevant theory concerning negotiation is the principal-agent theory which addresses the issue of information asymmetry between partners. This issue must be carefully considered when working together and setting up contracts, for example, by offering appropriate incentives and monitoring the agent according to their performance (Brown et al., Citation2006).

Concerning our risk factor “resources,” we see an overlap with the resource dependence theory. Pfeffer and Salancik (Citation1978) work on resource dependence theory, describes the influence of external resources on strategy and organizational behavior. The authority over particular resources can increase the power of one partner over the other but also reduce uncertainty and dependency (Hillman et al., Citation2009). We found several pieces of evidence in the analyzed studies to support the resource dependence theory.

The stakeholder theory introduced by Freeman (Citation1983) addresses the necessity to meet the needs of the organizations’ stakeholders and to respond to the challenges of the external environment. According to Freeman, this environment includes all groups and individuals that can affect or are affected by the organization. When comparing this with our analysis, we find an overlap with the risk factor “environment.” For example, an unstable government, a lack of political support, demand shortfalls and a strong competitive environment can lead to major problems within a PPP.

Interrelation between risk factors

Our analysis also reveals multiple interrelations between different risk factors. For example, it immediately becomes apparent that the risk factor “contract” plays a central role in PPPs. Interestingly, contracts are not only the most discussed risk factor in PPPs, but they are also often part of the solution. Contracts are a mitigation strategy for almost every other risk factor. Partners can determine the financial administration of the project, regular budget reporting, staff training, detailed time schedules, milestones or deadlines in their contracts, thus mitigating the risks. They can agree on the goals of a project and fix a strategy to achieve those goals. They can define decision-making structures or designate superordinate authorities. Even “soft” factors can be influenced by contracts. Partners, for example, can set regular meetings, define different communication channels or establish incentives for participation within the projects.

However, some researchers have recently doubted the importance of contract characteristics in the success of PPPs and emphasize the relevance of other, for example, relational characteristics (for example, Klijn & Koppenjan, Citation2016; Warsen et al., Citation2018). In fact, our study also provides strong support in that regard since we identified a vast body of literature referring to communication and trust with several interrelations to other factors. Based on our in-depth analysis, we conclude that it is because of that intense interrelation with other factors that such great importance is ascribed to contracts on the one hand and relationship factors on the other. These multiple interrelations can be explained by recent results that suggest that both contracts and relationships serve as coordination between partners (Caldwell et al., Citation2017). Interestingly, especially in long-term projects or projects with uncertainties, the relational coordination becomes an important complement to contractual safeguards (Caldwell et al., Citation2017).

Dynamics of risk factors

We also found some evidence that certain risks are more likely at the beginning of PPPs, while others might occur over the course of time. As partners often work together over a long time period, risks can change. Not without good reason, risk management is defined as a continuous and iterative process (Chinyio & Fergusson, Citation2003). Although there are already risk management frameworks that consider dynamic processes over the whole project (for example, Zou et al., Citation2008), little is known about differences regarding the actual impact and adequate mitigation strategies on the level of individual risks. Statements like “the startup phase appears critical” (Caldwell et al., Citation2009) point toward differences regarding the progress of a PPP and there are logical reasons for an approach that additionally considers different phases. During our analysis, we exploratively located the identified (sub) factors on a timeline. For example, risks regarding the contractual design naturally occur at the beginning (planning phase) of the collaboration, time delays or the acquiring of highly qualified human resources might be important during the actual process of collaboration (realization phase), and revenue risks become effective at the end (operation phase). However, for most risk factors it remains unclear to what extent their impact varies over the course of time. Therefore, future research should investigate the relationship between different factors and different phases of PPPs. Risk management will become more effective when the partners better understand what they should keep their eye on during the project.

Conceptual model

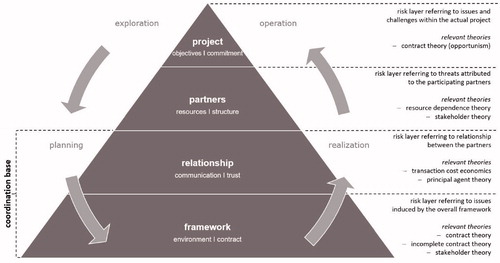

Based on the above-mentioned considerations, we derived a conceptual model to enhance the understanding of risks in PPPs (please see ). In the development of this model, we first identified the main foci of all risk factors and then depicted the interrelations between and dynamics of different risk factors to obtain a more sophisticated understanding about the scope, links and temporal relevance of each factor. In a second step, we strived to abstract and generalize our findings to allow a more holistic perspective as stated by the research goals. This model considers the following elements:

Firstly, we introduce so-called risk layers in our framework. This idea is based on our analysis, in which we repeatedly noted that the identified factors refer to different aspects within a PPP. Some of the factors mainly refer to issues and challenges within the actual project (e.g., objectives or commitment), while others relate to threats attributed to the participating partners (e.g., structure or resources). Further factors concern the relationship between the partners (e.g., communication or trust) and yet others refer to issues induced by the overall framework in which a PPP takes place (e.g., contracts or environment).

Secondly, building on our assumption that the importance of factors may vary over time, we suggest a top-down approach regarding these layers when identifying, evaluating or mitigating risks in the earlier stages of a PPP such as exploration and planning. Here, management is mainly guided by the objectives to be achieved. For example, based on certain objectives (risk layer: project), partners with the required resources are sought (risk layer: partners), initial communication channels are established (risk layer: relationship) in order to finally agree on a contract (risk layer: framework). Conversely, in the later stages of a PPP, such as realization and operationalization, we suggest a bottom-up approach. In these stages, management is mainly focused on the contract the partners have agreed on. For example, based on a certain contract (risk layer: framework), formal and informal communication takes place (risk layer: relationship), which positively or negatively influences the willingness to share certain resources (risk layer: partners) to eventually achieve contractually defined objectives (risk layer: project).

Thirdly, based on our finding that the factor contract as well as the relationship factors are strongly interrelated to all other factors, we assume that this is because they play an important role in the coordination of the project (Caldwell et al., Citation2017). Therefore, we determine the framework layer and the relationship layer as the base of our model, where the coordination between partners takes place and other layers build upon it. In fact, it is one of the most important tasks for all participating parties to ensure the functionality of this coordination base as issues here can impact the whole project and all other factors.

Finally, we assign some of the most relevant theories to the particular risk layers. In this context, it is important to acknowledge that each layer and each factor might have a different theoretical background as discussed in the previous section on the connection between our findings and the existing theories.

Summing up, our model provides a compact overview about the identified risk factors, assigns them to risk layers with different foci and relates them to relevant theories. Furthermore, we indicate the varying importance of certain risk factors over the cycle of a project and point out those layers with a coordinative background. This model is a clear representation of main aspects we derived from our literature review and can serve as a guide within the development and realization of PPPs.

Further research suggestions and limitations

We now suggest some issues that could be further discussed in PPP research. First, besides the reported risk factors, we identified several other risk factors, such as different cultures, partner selection, role of leadership or knowledge and technology transfer. Analyzing these factors in detail could provide helpful information for practitioners in PPP projects. Second, the current literature does not differentiate much regarding the size of the participating partners. However, we assume that the size of companies or public institutions will also influence the occurrence of risks and the availability of appropriate mitigation strategies. Future research should examine this question to allow organizations to focus on certain risk management strategies according to their size. Third, risks and challenges in developing countries may well be a lot different to those of developed countries (for example, political risks) and the approach to risk management might differ in those countries too. Further research is needed to understand the differences between developed and developing countries with regard to risks and risk management in PPPs.

Methodological choices always result from a weighing of advantages and drawbacks. First, the process of literature selection encompasses certain limitations. Some relevant articles might be excluded due to the formulated definitions of the exclusion criteria, others remain undiscovered due to the selection of our search terms, and still others were not included because of the determined time frame. Second, although we conducted a systematic review to minimize any bias and ensure the replicability of the investigation, a certain degree of professional judgment cannot be eliminated within a review of social science literature (Denyer & Tranfield, Citation2010). The definition of the factors, the choice of the risk management framework or the assessment of the importance of certain factors is subject to fundamental decisions. Although, our decisions were guided by methodological considerations and recommendations of previous research or by the synopsis of our quantitative and qualitative syntheses, we still have to acknowledge that other judges might have drawn different conclusions or might have rated some aspects differently (inter-rater reliability).

Conclusions

Although a vast body of literature is already available, to date there exists no overarching overview that synthesizes risk factors that are relevant to all PPPs regardless of the actual project or sector. The findings of our study contribute to the existing literature by providing a cross-sectoral understanding of risks in PPPs and relating our insights to elements of current risk management frameworks. Practitioners can use our results as an aid to build awareness and to identify, evaluate and mitigate actual risks when implementing a PPP. The conceptual model we developed shows different risk layers and suggests that the importance of risks might vary over time. We recommend that future research investigates the relationship between different factors and different phases of PPPs. Risk management will become more effective when partners better understand what they need to keep their eye on during the PPP.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (128.7 KB)Note

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Rybnicek

Robert Rybnicek is associate professor at the Department of Corporate Leadership and Entrepreneurship at the University of Graz, Austria. He specialized in public and strategic management. Recent research includes collaboration management and leadership.

Julia Plakolm

Julia Plakolm is a research assistant at the Department of Corporate Leadership and Entrepreneurship at the University of Graz, Austria. Her research interests include public management and cross sector collaboration, entrepreneurship and leadership.

Lisa Baumgartner

Lisa Baumgartner is a former research assistant at the Department of Corporate Leadership and Entrepreneurship at the University of Graz, Austria. Her research interests include public management and leadership development.

Notes

1 BTO—build, operate and transfer; DBFO—design, build, finance and operate; BOOT—build, own, operate and transfer; DBFOM—design, build, finance, operate and manage; BOO—build, own, operate.

References

- Abdel, A., & Ahmed, M. (2007). Successful delivery of public-private partnerships for infrastructure development. Journal of Construction Engineering & Management, 133(12), 918–931.

- Ahadzi, M., & Bowles, G. (2004). Public-private partnerships and contract negotiations: An empirical study. Construction Management and Economics, 22(9), 967–978.

- Alam, Q., Kabir, M. H., & Chaudhri, V. (2014). Managing infrastructure projects in Australia: A shift from a contractual to a collaborative public management strategy. Administration & Society, 46(4), 422–449.

- Anderson, T. S., Michael, E. K., & Peirce, J. J. (2012). Innovative approaches for managing public-private academic partnerships in big science and engineering. Public Organization Review, 12(1), 1–22.

- Ankrah, S., & Al-Tabbaa, O. (2015). Universities–industry collaboration: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31(3), 387–408.

- Barlow, J., Roehrich, J. K., & Wright, S. (2010). De facto privatization or a renewed role for the EU?: Paying for Europe’s healthcare infrastructure in a recession. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 103(2), 51–55.

- Barlow, J., Roehrich, J. K., & Wright, S. (2013). Europe sees mixed results from public-private partnerships for building and managing health care facilities and services. Health Affairs, 32(1), 146–154.

- Becker, F., & Patterson, V. (2005). Public- private partnerships: Balancing financial returns, risks, and roles of the partners. Public Performance & Management Review, 29(2), 125–144.

- Bel, G., Brown, T., & Marques, R. C. (2013). Public–private partnerships: Infrastructure, transportation and local services. Local Government Studies, 39(3), 303–311.

- Bettignies, J. E. D., & Ross, T. W. (2009). Public–private partnerships and the privatization of financing: An incomplete contracts approach. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 27(3), 358–368.

- Biginas, K., & Sindakis, S. (2015). Innovation through public-private partnerships in the Greek healthcare sector: How is it achieved and what is the current situation in Greece?. Innovation Journal, 20(1), 1–11.

- Bing, L., Akintoye, A., Edwards, P. J., & Hardcastle, C. (2005). The allocation of risk in PPP/PFI construction projects in the UK. International Journal of Project Management, 23(1), 25–35.

- Binza, S. M. (2008). Public-private partnerships in metropolitan government: Perspectives on governance, value for money and the roles of selected stakeholders. Development Southern Africa, 25(3), 297–315.

- Bloomfield, P. (2006). The challenging business of long-term public–private partnerships: Reflections on local experience. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 400–411.

- Boyer, E. J. (2016). Identifying a knowledge management approach for public-private partnerships. Public Performance & Management Review, 40(1), 158–180.

- Brinkerhoff, D. W., & Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2011). Public-private partnerships: Perspectives on purposes, publicness, and good governance. Public Administration and Development, 31(1), 2–14.

- Brousseau, E., & Glachant, J.-M. (Eds.). (2002). The economics of contracts: Theories and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, T. L., Potoski, M., & van Slyke, D. M. (2006). Managing public service contracts: Aligning values, institutions, and markets. Public Administration Review, 66(3), 323–331.

- Bryson, J. M., Crosby, B. C., & Stone, M. M. (2006). The design and implementation of cross-sector collaborations: Propositions from the literature. Public Administration Review, 66(s1), 44–55.

- Byoun, S., & Xu, Z. (2014). Contracts, governance, and country risk in project finance: Theory and evidence. Journal of Corporate Finance, 26, 124–144.

- Caldwell, N. D., Roehrich, J. K., & Davies, A. C. (2009). Procuring complex performance in construction: London Heathrow terminal 5 and a private finance initiative hospital. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 15(3), 178–186.

- Caldwell, N. D., Roehrich, J. K., & George, G. (2017). Social value creation and relational coordination in public-private collaborations. Journal of Management Studies, 54(6), 906–928.

- Carbonara, N., Costantino, N., Gunnigan, L., & Pellegrino, R. (2015). Risk management in motorway PPP projects: Empirical-based guidelines. Transport Reviews, 35(2), 162–182.

- Caselli, S., Gatti, S., & Marciante, A. (2009). Pricing final indemnification payments to private sponsors in project-financed public-private partnerships: An application of real options valuation. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 21(3), 95–106.

- Chinyio, E., & Fergusson, A. (2003). A construction perspective on risk management in public‐private partnership. In A. Akintoye, M. Beck, & C. Hardcastle (Eds.), Public-private partnerships: Managing risks and opportunities (pp. 93–126). John Wiley & Sons.

- Chou, J. S., & Pramudawardhani, D. (2015). Cross-country comparisons of key drivers, critical success factors and risk allocation for public-private partnership projects. International Journal of Project Management, 33(5), 1136–1150.

- Chung, D. (2016). Risks, challenges and value for money of public-private partnerships. Financial Accountability & Management, 32(4), 448–468.

- Chung, D., & Hensher, D. A. (2015). Risk Management in public-private partnerships. Australian Accounting Review, 25(1), 13–27.

- Clifton, C., & Duffield, C. F. (2006). Improved PFI/PPP service outcomes through the integration of alliance principles. International Journal of Project Management, 24(7), 573–586.

- Cruz, C. O., & Marques, R. C. (2013). Flexible contracts to cope with uncertainty in public–private partnerships. International Journal of Project Management, 31(3), 473–483.

- Currie, D., & Teague, P. (2015). Conflict management in public-private partnerships: The case of the London underground. Negotiation Journal, 31(3), 237–266.

- Davis, K. (2005). PPPs and infrastructure investment. The Australian Economic Review, 38(4), 439–444.

- Denyer, D., & Tranfield, D. (2010). Producing a systematic review. In D. A. Buchanan & A. Bryman (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational research methods (pp. 671–689). Sage Publications Inc. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Denyer-Tranfield-Producing-a-Systematic-Review.pdf

- Domingues, S., & Zlatkovic, D. (2015). Renegotiating PPP contracts: Reinforcing the ‘P’ in partnership. Transport Reviews, 35(2), 204–225.

- Dubini, P., Leone, L., & Forti, L. (2012). Role distribution in public-private partnerships: The case of heritage management in Italy. International Studies of Management & Organization, 42(2), 57–75.

- Durand, M. A., Petticrew, M., Goulding, L., Eastmure, E., Knai, C., & Mays, N. (2015). An evaluation of the public health responsibility deal: Informants’ experiences and views of the development, implementation and achievements of a pledge-based, public-private partnership to improve population health in England. Health Policy, 119(11), 1506–1514.

- Edelenbos, J., & Klijn, E. H. (2007). Trust in complex decision-networks: A theoretical and empirical exploration. Administration & Policy, 39(1), 25–50.

- Fischbacher, M., & Beaumont, P. B. (2003). PFI, public-private partnerships and the neglected importance of process: Stakeholders and the employment dimension. Public Money & Management, 23(3), 171–176.

- Fischer, C., & Porath, D. (2010). A reappraisal of the evidence on PPP: A systematic investigation into MA roots in panel unit root tests and their implications. Empirical Economics, 39(3), 767–792. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-009-0321-7

- Forrer, J., Kee, J. E., Newcomer, K. E., & Boyer, E. J. (2010). Public–private partnerships and the public accountability question. Public Administration Review, 70(3), 475–484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02161.x

- Fourie, F. C., & Burger, P. (2000). An economic analysis and assessment of public-private partnerships (PPPs). The South African Journal of Economics, 68(4), 305–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2000.tb01274.x

- Freeman, E. R. (1983). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Advances in Strategic Management, 1(1), 31–60.

- Garcia Martinez, M., Verbruggen, P., & Fearne, A. (2013). Risk-based approaches to food safety regulation: What role for co-regulation? Journal of Risk Research, 16(9), 1101–1121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2012.743157

- Grimsey, D., & Lewis, M. K. (2002). Evaluating the risks of public private partnerships for infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management, 20(2), 107–118.

- Grossman, S. A. (2010). Reconceptualizing the public management and performance of business improvement districts. Public Performance & Management Review, 33(3), 361–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576330304

- Grossman, S. A. (2012). The management and measurement of public-private partnerships. Public Performance & Management Review, 35(4), 595–616. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576350402

- Hellowell, M. (2016). The price of certainty: Benefits and costs of public-private partnerships for healthcare infrastructure and related services. Health Services Management Research, 29(1-2), 35–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0951484816639742

- Heurkens, E., & Hobma, F. (2014). Private sector-led urban development projects: Comparative insights from planning practices in the Netherlands and the UK. Planning Practice & Research, 29(4), 350–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2014.932196

- Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427.

- Holmström, B., & Hart, O. (1987). The theory of contracts. In T. F. Bewley (Ed.), Advances in economic theory (pp. 71–156). Cambridge University Press.

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- International Organization for Standardization. (2018). ISO 31000: Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en

- Jacobson, C., & Choi, S. O. (2008). Success factors: Public works and public-private partnerships. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 21(6), 637–657.

- Kakabadse, N. K., Kakabadse, A. P., & Summers, N. (2007). Effectiveness of private finance initiatives (PFI): Study of private financing for the provision of capital assets for schools. Public Administration and Development, 27(1), 49–61.

- Ke, Y., Wang, S., Chan, A. P. C., & Cheung, E. (2009). Research trend of public-private partnership in construction journals. Journal of Construction Engineering & Management, 135(10), 1076–1086.

- Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. (2016). The impact of contract characteristics on the performance of public–private partnerships (PPPs). Public Money & Management, 36(6), 455–462.

- Klijn, E. H., & Teisman, G. R. (2003). Institutional and strategic barriers to public-private partnership: An analysis of Dutch cases. Public Money and Management, 23(3), 137–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9302.00361

- Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2005). The formation of public-private partnerships: Lessons from nine transport infrastructure projects in the Netherlands. Public Administration, 83(1), 135–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-3298.2005.00441.x

- Kwak, Y. H., Chih, Y., & Ibbs, C. W. (2009). Towards a comprehensive understanding of public private partnerships for infrastructure development. California Management Review, 51(2), 51–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41166480

- Landow, P., & Ebdon, C. (2012). Public-private partnerships, public authorities, and democratic governance. Public Performance & Management Review, 35(4), 727–752. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576350408

- Lane, C., & Bachmann, R. (Eds.). (1998). Trust within and between organizations: Conceptual issues and empirical applications. Oxford University Press.

- Leruth, L. (2012). Public-private cooperation in infrastructure development: A principal-agent story of contingent liabilities, fiscal risks, and other (un)pleasant surprises. Networks and Spatial Economics, 12(2), 223–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-009-9112-0

- Li, B., Akintoye, A., Edwards, P. J., & Hardcastle, C. (2005). Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 23(5), 459–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190500041537

- Little, R. G. (2011). The emerging role of public-private partnerships in megaproject delivery. Public Works Management & Policy, 16(3), 240–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X11409244

- Liu, T., & Wilkinson, S. (2014). Using public-private partnerships for the building and management of school assets and services. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 21(2), 206–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-10-2012-0102

- Loosemore, M., & Cheung, E. (2015). Implementing systems thinking to manage risk in public private partnership projects. International Journal of Project Management, 33(6), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.02.005

- Marques, R. C., & Berg, S. (2011). Public-private partnership contracts: A tale of two cities with differnet contractual arrangements. Public Administration, 89(4), 1585–1603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.01944.x

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), Article Number 20.

- Meidutē, I., & Paliulis, N. K. (2011). Feasibility study of public-private partnership. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 15(3), 257–274. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3846/1648715X.2011.617860