Abstract

Institutional factors such as data standardization, data interoperability, and the ability to include other stakeholders (e.g., civil society) in ecosystems are now understood as crucial considerations in Open Government Data (OGD) implementation. However, most of the current understanding of institutional factors linked to OGD growth has evolved around highly digitalized and developed countries. This study aims to address this gap by investigating open data implementation in Indonesia, a developing country that has been an early advocate of OGD in the "Asia Pacific". In 2014, Indonesia implemented Satu Data Indonesia (One Data Indonesia) as a national initiative to promote OGD objectives. We employ institutional dimensions as the central theoretical lens to unpack the successes and impediments to Satu Data Indonesia’s development. This research dataset is built on 16 expert interviews from government (n = 14) and private (n = 2) organizations that directly contribute to the growth of Satu Data Indonesia, qualitatively triangulated with documentary analysis of key policy and regulatory documents. These new data provide important insights into the complexity and challenges of nationwide OGD implementation and data-sharing. Our findings show that despite its being an early advocate, Indonesia’s OGD initiative is still in the early stages of development, impeded by several policy and administrative bottlenecks.

Introduction

Open Government Data (OGD) initiatives can have a positive impact on governments and society by providing political, social, economic, operational, and technical benefits when implemented successfully (Janssen et al., Citation2012). Existing literature suggests that OGD encourages government transparency, citizen participation, value creation, citizen-centric services, and commercial innovation (Cahlikova & Mabillard, Citation2020; Schrock & Shaffer, Citation2017; Wirtz et al., Citation2018). For example, openly available government data build economic value by creating new business models that use OGD to generate revenue from value-added services (Ahmadi et al., Citation2016). OGD initiatives also have the potential to improve democratic processes and civic participation (Dawes et al., Citation2016). OGD benefit government agencies, citizens, nonprofits, activists, businesses, and research organizations alike. When organized well, OGD may allow realistic, evidence-based, and transparent governance and policymaking and give accessible opportunities for citizens and policymakers to review policy outcomes, increasing the role of organizational leadership in OGD implementation (Safarov, Citation2019). However, implementing OGD is a challenging task for governments.

Realizing OGD benefits requires meeting significant prerequisites; simply publishing data does not guarantee these benefits (Janssen et al., Citation2012). The institutional lens for studying open data and open government is firmly established in public management literature (Altayar, Citation2018; Cahlikova & Mabillard, Citation2020; Janssen et al., Citation2012; Zhao et al., Citation2022). The extant literature argues that the hindrance stems from institutional factors, such as data standardization, data interoperability, and the inability to include other stakeholders (e.g., civil society) in ecosystems (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2023; Kassen, Citation2019; Safarov, Citation2019). Dawes et al. (Citation2016) highlight the importance of developing an ecosystem model of stakeholders, policies, practices, relationships, and influences. Additionally, a linear process model with four components—strategy and planning, implementation, open data transformation, and data utilization impact—is critical for OGD implementation (Jetzek, Citation2016). We focus on five key institutional dimensions crucial to OGD implementation, as proposed by Safarov (Citation2019, Citation2020): policy and strategy, legislative foundations, organizational arrangements, necessary skills and education, and public support and awareness. In this study, we aim to investigate OGD implementation in Indonesia through the lens of institutional dimensions, addressing a gap in research focused mainly on highly digitized and developed countries.

Indonesia is a developing country that has been an early OGD adopter in the “Asia Pacific”, since co-establishing the global OGD advancement initiative Open Government Partnership in 2011 with seven other countries (Tjondronegoro et al., Citation2022). In 2014, Indonesia adopted a national OGD initiative, Satu Data Indonesia (SDI; One Data Indonesia), to advance OGD goals (Indrajit, Citation2018). Despite the early start, Indonesia’s OGD rankings are similar to those of other developing countries (Syarif et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we position our research in the emerging literature on OGD implementation that deals with institutional dimensions (Safarov, Citation2019, Citation2020) and posit the question: How do institutional dimensions impact OGD implementation in Indonesia?

This paper is structured as follows: first, we discuss OGD, OGD implementation, and the theoretical framework of institutional dimensions (Safarov, Citation2019); second, we introduce OGD growth in Indonesia; third, we outline the research design and methods used; and fourth, we present our findings within the context of the five institutional dimensions. In our discussion, we emphasize the importance of a contextual evaluation of the SDI initiative to fully leverage its potential.

Theoretical background of OGD implementation

What is OGD?

Since Barack Obama’s memorandum on transparency and open government in 2009, scientific and public interests have been increased on OGD in developed and developing countries (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2023; Matheus & Janssen, Citation2020). OGD are government data freely available for public use and reuse (Janssen et al., Citation2012; Schrock & Shaffer, Citation2017). OGD implementation is a governmental process that involves many stakeholders, including government agencies, policymakers, and citizens. It involves various activities, from data-sharing decisions to organizational changes and legal framework construction. OGD frameworks encompass technical, policy, organizational, and user perspectives.

Past literature on OGD frameworks has employed various methodologies, focusing on different aspects of open data initiatives (Attard et al., Citation2015). These aspects include technical considerations, such as data accessibility, interoperability, and reusability (Ancarani, Citation2005; Vetrò et al., Citation2016), as well as issues related to information quality like accuracy and user-friendliness (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2023; Vetrò et al., Citation2016). Scholars also explore policy and governance frameworks, assessing how legal, regulatory, and institutional factors impact OGD initiatives (Dawes et al., Citation2016). Effective OGD frameworks require understanding stakeholder engagement and user perspectives, examining how open data usage affects societal domains (Gascó-Hernández et al., Citation2018; Jugend et al., Citation2020; Safarov et al., Citation2017).

An institutional dimensions perspective on OGD implementation

Institutions encompass shared values, rules, norms, and cultures shaping complex social structures and influencing behavior and perceptions (Scott, Citation2013). They provide frameworks that facilitate and constrain these social dynamics. The use of an institutional lens to study open data and open government is well established in public management literature (Altayar, Citation2018; Cahlikova & Mabillard, Citation2020; Janssen et al., Citation2012; Zhao et al., Citation2022). In our study, we specifically focus on a set of institutional dimensions central to public management literature.

Grounded in discursive institutionalism (Schmidt, Citation2008), our argumentation on institutional dimensions embodies five fundamental dimensions proposed in extant literature (Safarov, Citation2019, Citation2020). These dimensions are policy and strategy, legislative foundations, organizational arrangements, relevant skills and educational support, and public support and awareness. Policy and strategy refer to the national and organization-level open data policies that guide strategic actions throughout the process of OGD implementation. Legislative foundations relate to the strong legal and regulatory frameworks that provide clear guidance to implementing OGD initiatives. Organizational arrangements denote the organizational leadership and infrastructure that enable and facilitate OGD implementation. Relevant skills and educational support are essential for developing knowledge in open data management. Public support and awareness involve a feedback loop with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), companies, and civil society to effectively implement OGD. The aforementioned dimensions are not exhaustive nor do they operate in isolation. We view them as interconnected and emergent, given the context-specific nature of OGD implementation. These institutional dimensions foster interactive processes of policy coordination and communication among social agents and government agencies involved in OGD implementation.

The institutional dimensions are studied as both implicit and explicit in broader OGD literature within public management (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2023; Matheus & Janssen, Citation2020; Zhao et al., Citation2022). The adaptability of this framework facilitates the analysis of challenges and opportunities exclusive to developing countries, such as bureaucratic complexities, varying levels of digital literacy, and other resource constraints. presents a summary of scholarly articles addressing institutional dimensions of OGD implementation. We included empirical works that study OGD at the national level (or federal level, but not state or city level), published in academic journals that are listed as Q1 in the Scimago Journal Rank. Accordingly, we could not corroborate some studies in the table (e.g., see Parung et al. (Citation2018) and Purwanto et al. (Citation2020) in the context of Indonesia). We include studies where the institutional perspective is implicitly discussed. Our summary of empirical insights into OGD implementation across countries is not comprehensive. Readers should interpret these insights as context-specific, explicitly or implicitly relating to our central theoretical lens of institutional dimensions. Focusing on institutional dimensions helps pinpoint areas for development and capacity-building, including strategies to boost public engagement. The adaptability of these five dimensions makes them suitable for identifying and addressing the challenges and needs of OGD implementation in developing countries like Indonesia.

Table 1. Empirical insights into Open Government Data (OGD) that relate to the institutional dimensions framework.

The empirical findings underscore the crucial role of institutional dimensions in the effective implementation of OGD initiatives. However, existing literature in public management lacks sufficient insight into these dimensions within the context of developing countries. Thus, our research aims to fill this gap by delving into the specific institutional dynamics within developing nations like Indonesia, seeking a deeper understanding of each dimension to inform effective OGD implementation strategies.

Indonesia country context: OGD and SDI

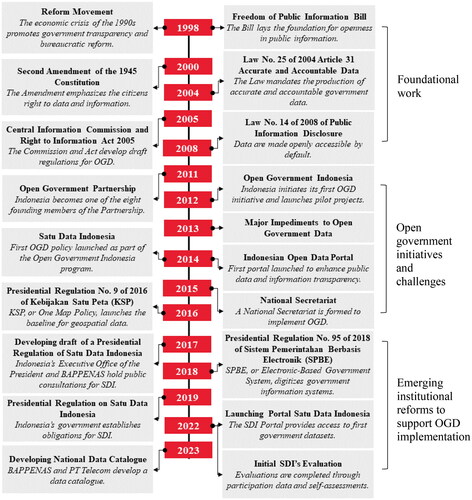

The research context of our study denotes OGD implementation in Indonesia, a developing country. From the beginning (see ), Indonesia’s OGD development involves three stages: foundational work (late 1990s to late 2000s), the first OGD initiatives (early 2010s to mid-2010s), and emerging institutional reforms to support OGD implementation (mid-2010s to the present). We briefly provide insights into Indonesia’s critical OGD developments below.

Indonesia is an original member of the Open Government Partnership, which launched in 2011 to enhance government transparency and accountability through open data and now includes 75 countries. Since joining, Indonesia has initiated regional pilot projects in Central Borneo province, Indragiri Hulu regency, and Ambon city and established the National Secretariat for Open Government. The SDI policy and data service portal data.go.id were introduced in 2014, with the presidential regulation on SDI launched in 2019 after 2 years of drafting and public input. In December 2022, Indonesia launched the SDI portal. Preceding SDI is the Indonesia Electronic-Based Government System (SPBE), or Sistem Pemerintahan Berbasis Elektronik, established under presidential regulation No. 95/2018 to enhance public service quality and governance transparency. SPBE serves as the digital infrastructure upon which SDI builds, now further detailed by presidential regulation No. 132/2022 to streamline implementation across local and central governments nationwide.

Early evaluation research in Indonesia highlights institutional and informational barriers to national OGD implementation. These include conflicts with traditional government bureaucracy, a lack of integrated OGD policies (Jacob et al., Citation2019), issues with open data standardization and publishing in machine-readable formats (Nusapati & Sunindyo, Citation2017; Tundjungsari, Citation2022), and underutilization of more than 400,000 digital applications across local and central government organizations (Maarif, Citation2020). Despite significant investments in digital government services (USD 80 million between 2014 and 2016), utilization rates remain low at about 30%. Additionally, 2,700 government databases are not interoperable, hindering effective data utilization (Directorate General of Information Applications, Citation2021). Technical challenges persist in data standardization and machine-readable publishing (Nusapati & Sunindyo, Citation2017), exacerbated by inadequate regulatory frameworks, unclear priority settings, limited data infrastructure and digital literacy among human resources (Soegiono, Citation2018).

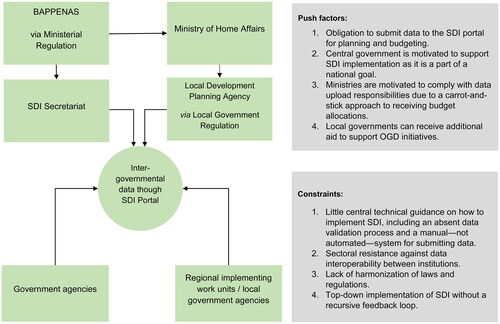

outlines the organizational structure of SDI implementation, which includes a governing board or steering committee, SDI forum, SDI Secretariat, data stewards, custodians, owners, and users. Each entity within the SDI has defined roles, although there is some overlap and redundancy. The SDI Secretariat oversees an SDI forum that horizontally connects key ministries involved in the SDI. Our analysis examines SDI governance at national and sub-national levels, encompassing 34 provinces and 508 local governments (OECD & United Cities and Local Governments, Citation2016). The national government, namely the Office of the President of Indonesia and The Ministry of National Development and Planning, or Badan Perencanaan Pembangunan Nasional (henceforth, BAPPENAS), is the agency responsible for SDI implementation.

Table 2. The formal organizational structure of Open Government Data (OGD) implementation in Indonesia.

Methods and research design

Indonesian settings provide an excellent opportunity to analyze and reveal relevant institutional dimensions that impact SDI implementation in developing countries. Hence, we focus on the implementation of SDI for an in-depth understanding as part of the broader phenomenon of OGD implementation. We posit the following research question: How do institutional dimensions impact OGD implementation in Indonesia?

Public management literature has firmly established a qualitative approach to studying institutional dimensions in OGD implementation (Altayar, Citation2018; Cahlikova & Mabillard, Citation2020; Janssen et al., Citation2012). The qualitative method focuses on in-depth exploration rather than broad coverage, achieved through semi-structured interviews with expert individuals involved in OGD adoption in governmental and critical industry settings (n = 16), along with key policy documents.Footnote1 The semi-structured interviews asked questions based on the five dimensions of the theoretical framework and one open-ended question that allowed for any relevant information beyond the framework to be shared. For the recruitment of interviewees, the study used purposive (direct contact) and snowball sampling (end-of-interview request) techniques. To obtain access and buy-in from Indonesia’s expert government stakeholders and private industry partners—hard-to-reach populations—we recruited a team member who works for a public government research agency in Indonesia. This access meant that we could gather extensive insights from OGD expert practitioners in Indonesia and clarify details of OGD implementation. Purposive sampling allowed us to recruit specialist interviewees directly, while snowball sampling allowed us to connect with hard-to-reach populations based on well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Creswell & Clark, Citation2017). The interviews were conducted face-to-face and online in Bahasa. The de-identified citations in-text are translations of Bahasa interviews into English.

Our recruited interviewees were stakeholders with direct experience of working in government agencies in Indonesia and the ability to influence policy directly related to OGD. The interviewees were, therefore, deemed as experts, having “comprehensive and authoritative knowledge in a particular area not possessed by most people” (Caley et al., Citation2014, p. 232). Experts have honed their abilities to distill the significant characteristics that differentiate them, integrating data, theory, and other sources of information, informed by their experience (Caley et al., Citation2014). The interviewed experts represented a variety of organizations linked to OGD implementation. The 16 interviews, therefore, present 11 different OGD stakeholder organizations, including stakeholders from the central government (n = 10), local governments (n = 4), and the private sector (n = 2). The interviews were carried out in early 2023.

Our data analysis combined theory-driven deductive and data-driven inductive approaches (Skjott Linneberg & Korsgaard, Citation2019). Namely, we inductively code empirical data within a predefined theoretical framework consisting of five institutional dimensions. To construct themes within the theoretical framework of the five institutional dimensions, we used reflexive thematic analysis (RTA; Braun & Clarke, Citation2016, 2019, Citation2021). RTA—one of the most widely used methods in qualitative data analysis—develops themes from codes and deploys analytic and interpretative research work during data analysis (Collins & Stockton, Citation2018; Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). Our data analysis followed a six-step process of initial familiarization of the data by reading and rereading it, generating initial codes, searching for initial themes, naming and defining the themes, and writing a final version of the narrative (Braun & Clarke, Citation2016, Citation2021). While analyzing our empirical data, we iteratively revisited scholarly works on institutional dimensions at the intersection of OGD implementation. Two types of qualitative data—interviews as well as key regulations and laws—helped to qualitatively triangulate the findings further and present them in more depth (Flick, Citation2004). Ethics approval for this study was granted by Griffith University, Ethics Number 2022/184.

Findings

This section provides a detailed description of the development of SDI, including the interplay of the evolution of SDI and its governance. The findings are presented within the five dimensions of institutional frameworks theory: (1) policy and strategy, (2) legislative foundations, (3) organizational arrangements, (4) relevant skills and educational support, and (5) public support and awareness.

Policy and strategy

The findings of this paper show that the SDI governance structure contains several bottlenecks at the policy and strategy levels. While the central government has invested significant effort to create an organizational governance structure, the structure remains top-down without embedded feedback or accountability mechanisms. Our findings offer a bird’s-eye-view perspective of the key policy and strategy bottlenecks and complement existing evaluatory research studies.

First, BAPPENAS has been appointed as the implementor of SDI due to its bureaucratic and organizational capacity to assign budgets and monitor implementation. Although fluent in process dynamics, BAPPENAS’ capacity for data governance was reported to be limited. Based on the budget and task allocation strengths of BAPPENAS, meeting the targets rather than developing a robust concept of SDI has been a priority. SDI’s current focus is on depositing data, which is a common issue in early OGD development (Piotrowski et al., Citation2019).

The current SDI concept is limited to depositing data. The design of the institutional level, data integration, and protocols for data validation could be clearer … BAPPENAS has not determined what data dependency system should be built, its impacts, nor priorities. […] They should plan out the business processes, data, and the applications before developing new systems. (I2)

At the national level, the SDI Secretariat, appointed by the president, oversees the formulation, management, and facilitation of presidential regulations concerning SDI. Its primary goal is to promote data exchange among ministries and government agencies. While it encourages data-sharing, the SDI Secretariat lacks unified standards or guidelines for this process. Instead, it uses budget allocations as incentives for data exchange, employing a “carrot-and-stick” approach. Specifically, Indonesian Ministries can only receive an SDI budget allocation if they can coordinate project budgeting for data exchange in each ministry related to the scope of their responsibilities (I1). While shown to be effective in pushing subnational-level government units toward policy implementation in published literature (Pan & Fan, Citation2023), our findings suggest that this approach has created a vertical hierarchy of command and response but hindered dialogue between national and subnational levels of government.

The need for adherence to standard data is prevalent, with discussions outweighing practical solutions in existing forums. The current reality must meet expectations as challenges persist in establishing data centers, reaching agreements, and populating the website. In contrast, determining priority data still needs to be solved as each institution is tasked with determining it independently. (I8)

Third, findings show that local governments demonstrate advancements in certain areas, such as digital payments, surpassing central government agencies in terms of digitalization in some areas. While the advancement of such digitalization examples speaks to local governments’ initiative in OGD, these examples also imply fragmentation of public services, with local governments pursuing independent digitalization tasks that need to be aligned with the central government. Literature published in other countries supports these findings, affirming that in the absence of clear government regulations, motivations for innovation among local government units tend to vary (Sanina, Citation2024).

The governance gaps have resulted in the private sector’s strong involvement in several areas of SDI implementation. Privatizing SDI goal implementation has been critical for government agencies to meet central government targets on schedule, placing private enterprises in a key position for SDI implementation. A private sector representative frankly commented on the role of private enterprise in SDI involvement:

BAPPENAS appears to be in a state of chaos, and the implementation of SDI is also facing challenges making the situation rather messy. … Various individuals have different perspectives on this matter. As a representative of the private sector, it is our responsibility to play a role in enhancing the country’s progress. If we fail to contribute, it becomes difficult to collectively build a stronger nation. (I12)

Legislative foundations

Indonesia is currently undergoing macro-scale legal harmonization. Harmonizing presidential decrees and laws pertinent to SDI and OGD more broadly is crucial because SDI is currently governed by a presidential decree that does not carry legislative power, thus limiting its legal implementation impetus. Several interviewees stressed the limited powers of a presidential decree in Indonesia when commenting on the legislative foundations of SDI. Although the SDI presidential decree 39/2019 was a powerful catalyst to initiate SDI projects, its legal limitations compared to national laws have restricted its nationwide implementation.

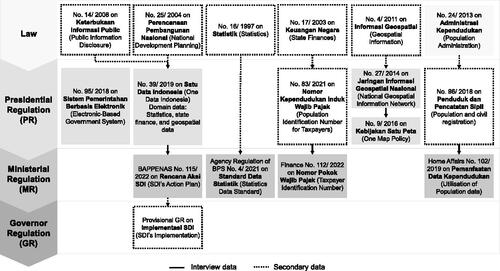

Three types of laws and regulations are relevant to understanding the governance of SDI: national laws, presidential decrees, and ministerial laws/regulations (see ). National laws in Indonesia are established by the legislative branch of the government, which consists of the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat) and the People’s Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat). National laws cover a wide range of topics. They are enacted through a formal legislative process and serve as the primary legal framework for the entire country. Ministerial regulations (Peraturan Menteri) are issued by individual ministers within the Indonesian government. These regulations provide specific guidelines and rules within the respective ministries’ areas of responsibility. Presidential decrees (Keputusan Presiden) are issued by the president of Indonesia, usually to address matters that require immediate attention or have a significant impact on the nation; the SDI implementation is encouraged by a presidential decree.

The regulation most pertinent to SDI implementation is the 39/2019 SDI presidential decree. The Executive Office of the President and BAPPENAS started drafting the presidential decree in 2017 in consultation with more than 100 representatives from the private sector, civil society, and government agencies. The regulation established the obligations of an integrated data management service in 2019 (Riwukore et al., Citation2021). The 2019 presidential regulation formalized the government’s commitment to SDI and its key aim to share data across central and regional government agencies and established clear timelines for such implementation. Presidential decrees carry a lot of importance but their implementation may be contested because they are outside the formal national legislative and implementation frameworks.

Appropriate regulations from the central to the local level are essential. Currently, rules have yet to be formally established through local government decrees. The local government is interested in conducting a comparative study before legally implementing the regulations. (I11)

Research findings indicate that the macro-scale harmonization of laws in Indonesia is currently pending. First, the previously implemented e-government initiative (i.e., SPBE) and the ongoing SDI are governed by presidential decrees that do not carry the weight of a national law. National laws override the governance of SDI, which has sometimes prevented data required for SDI implementation from being accessed. A national government stakeholder illustrated the discrepancy by citing examples from multiple ministries:

The Ministry of Home Affairs uses the Law of Population Data, while SDI uses the Presidential decree which is in a lower position in Indonesia’s regulatory hierarchy. … For example, the Ministry of Home Affairs will not share their citizen data such as names and addresses until SDI requires that by law. (I1)

Concerning SDI, regulations should be harmonized so that they do not cancel each other out. (I3)

New regulations in the government sometimes make it difficult for us as executors. … The data via e-government Indonesia is already available, so why should it also be integrated with SDI, which wastes resources? (I4)

Organizational arrangements

The organizational arrangements of SDI implementation were interlinked with the legal backdrop and the role that BAPPENAS has played as the implementation body of SDI. Strong organizational arrangements, including robust leadership, active stakeholder engagement in the data-opening process, prompt response to societal needs, and fostering an open organizational culture are essential for OGD (Safarov, Citation2019). Indonesia’s organizational arrangements are currently facing several organizational bottlenecks.

The first major bottleneck in SDI organizational arrangements is the SDI Secretariat’s top-down SDI goal-setting. The SDI forum is the link between the national and subnational levels of SDI and is coordinated by a special task force unit in BAPPENAS. The presidential decree recognized BAPPENAS as the national champion for developing SDI and created new requirements for organizational learning. Despite their established experience in policymaking and implementation, the agency needs further expertise in data and systems, including data architecture, administration, and data integration (I1, I2, I15). Additionally, the SDI Secretariat is severely under-resourced, with only one staff member—the director of the SDI Secretariat.

BAPPENAS is only conducting the clearance for planning and evaluation processes. Therefore, BAPPENAS only governs the beginning and end of the SDI development. (I1)

Second, the government organization in Indonesia has unequal hierarchy levels, with the SDI Secretariat serving as a non-echelonFootnote2 task force unit. A non-echelon task force unit is an organizational unit that operates outside the regular hierarchical levels to address a specific task or objective falling outside of the direct government hierarchy. A flexible organizational structure offers advantages but can limit a government unit’s implementation capacity, as identified in the case of the SDI Secretariat. Additionally, the Ministry of Communication and Information also needs more organizational power to incorporate SPBE into SDI, despite being responsible for SPBE. The situation is exacerbated by current challenges in completing SPBE goals being hampered by low budget allocation and shortages of staff with technical skills before integration with SDI is considered:

The current challenge is that SPBE in [city name] has … 900 applications listed … but utilization is only around 30% or 70%, nothing more than that because it has stalled. Therefore, the applications need to be deleted … (I14)

We understand that the intention [behind creating SDI] is good and that government agencies are following their main tasks and functions. … There is, however, no uniformity in operational definitions, sources [of data], data reference codes, or standardized metadata. … These are the main challenges for data sharing. … SPBE is ongoing and was released earlier than SDI. I do not know if it has been designed to be integrated with SDI or if it will be linked later. In the future, there will be integration challenges in the relationship between SPBE and SDI. (I15)

SDI requires government agencies to implement their understanding of government data. At the local level, frustrations arise from several factors: first, the perceived incompetence of the national champion responsible for data management; second, the lack of evaluation regarding the SDI implementation; and third, the burden imposed on local governments by conflicting policies from the central and provincial levels. Central governments prioritize policy execution tied to accessing the central budget, potentially neglecting local governments’ involvement in decision-making. Moreover, local governments require more avenues to advocate for their specific needs and concerns in policymaking.

Relevant skills and educational support

While participants acknowledged that relevant digital skills were important for SDI, there were few programs available to support the development of those skills and the recruitment process of the technical staff was seen as limited by bureaucratic recruitment barriers. The interviewees discussed two types of training: training for public servants working with SDI and technical higher education for graduates entering public administration.

Many interviewees acknowledged that public servants often did not have the required skills to effectively facilitate the implementation and integration of SDI, with some training potentially creating more issues with integrated data implementation:

There is a training program that requires public servants in national agencies to focus on institutional innovation. Most of the participants chose to develop new information systems. … The program has damaged existing ecosystems and created new silos. (I2)

Understanding the concept of digital technology transformation as the key aspect, followed by IT skills, is a necessity for SDI. (T4)

The higher education sector in Indonesia must address the demand for technical skills necessary to support the widespread implementation of SDI at both the national and subnational levels. There is currently an ad hoc approach to ensuring technically prepared staffing. Key skills encompass digital literacy, data management proficiency, data analytics, machine learning, data visualization, and dashboards for decision-making and policymaking. The ethical and responsible application of data and analytics requires integrating social, technical, and ethical perspectives.

Public support and awareness

Public support and awareness are challenging in both developed and developing countries, as they require a systemic approach to developing education and skills (Safarov, Citation2019). In Indonesia, the broader population remains largely unaware of the advantages offered by OGD. Moreover, public support and awareness regarding SDI are still in the nascent stages of development. There is a pressing need for the government to emphasize efforts related to strengthening this institutional dimension of SDI. None of the interviewees could contribute information about past, current, or planned activities to provide public support and awareness of SDI.

In 2013, researchers discovered that Indonesia’s private sector and the media currently have the greatest need for government data, such as real-time weather and traffic statistics (Alonso et al., Citation2013). The private sector can incorporate correct data into its products and services, and the media can collaborate on data-driven journalism. One government organization reported working with a private stakeholder by employing big data analytics related to regional inflation to support policy- and decision-making (I13). A stakeholder representing a private company commented on the issue of raising social awareness of SDI:

SDI needs a budget to support [OGD awareness], such as digitalization and a campaign. Unfortunately, the budget for municipal government is limited. The Central Government supports it at the Ministerial level … NGOs in Indonesia are still struggling to make a difference in the country. … The government will create guidelines only if the problem goes viral on social media. They will address it only when it becomes a “loud” issue, such as data leaks that netizens are likely to publicize. (I11)

[T]he main problem with the digitalization of government data is that 80% of their data is still manual. … No one takes the lead in fixing data in Indonesia. The actual data exist regionally. (I12)

Social media is rife with various negative news items, including issues related to personal data protection and data leaks. Regardless of the authenticity of these cases, they serve as a driving force for the Ministry to take prompt action and address these matters swiftly. (I11)

Public support and awareness were the weakest institutional dimensions of SDI implementation. More direct efforts should be focused on facilitating SDI implementation to maximize its use, as public engagement with SDI data has been ad hoc and disrupted by the lack of data standardization on the SDI portal. Research shows that if open data consumers find data difficult to access, of poor quality, or challenging to analyze, their motivation to use the available data decreases (Purwanto et al., Citation2020). After addressing legal, administrative, and organizational challenges, prioritizing public support and awareness is crucial for promoting SDI.

Discussion

The findings of this research project offer a comprehensive overview of the institutional dimensions of SDI’s implementation and carry significant implications for OGD implementation in Indonesia and internationally. Below, we present three institutional dimensions currently being developed through SDI implementation: policy and strategy, legislative foundations, and organizational arrangements. SDI implementation is currently focused on resolving macro-level barriers among these three institutional dimensions, including SDI laws, regulations, policies, responsibilities, and leadership. The two remaining institutional dimensions—relevant skills and educational support as well as public support and awareness—have received little attention to date. We then contextualize the findings against the background of other emergent countries.

Institutional dimensions

Policy and strategy

Previous research suggested conflicting processes between Indonesia’s traditional government bureaucracy and the requirements of OGD implementation in terms of shifts in government culture and processes, as well as digital literacy and collaboration requirements (Jacob et al., Citation2019). As Piotrowski et al. (Citation2017) cautioned, continually increasing the amount of information deposited rather than implementing a comprehensive information strategy will not result in OGD growth. Our research has confirmed these findings and has further identified specific areas that need to be addressed for successful SDI implementation in Indonesia. These areas include leadership in policymaking processes to remove overlapping OGD initiatives, allocating additional resources to support the SDI implementation, legal harmonization of OGD laws, sustained technical training programs for higher education and public service sectors, and public awareness activities. Additionally, Indonesia needs to develop institutional policies and strategies for SDI, open data transformation, and data utilization impact measures, which are critical for OGD implementation (Jetzek, Citation2016).

Legislative foundations

SDI implementation was facilitated by the 39/2021 presidential decree. The decree has been a strong catalyst in mobilizing organizational focus to start SDI implementation. Falling outside the scope of national law, however, a decree has limited power to guide the SDI implementation. The Indonesian government is working on harmonizing the SPBE and SDI presidential regulations into a single Digital Transformation Law. This would help resolve legal bottlenecks that currently do not strictly require subnational governments to work toward OGD implementation.

Organizational arrangements

Research comparing OGD implementation in developed countries has shown that a strong central government can play a crucial role in determining the speed of OGD implementation (Safarov, Citation2019). This is especially true if the central government recognizes OGD as a tool for fostering economic growth, transparency, and accountability. In comparison, we show that in Indonesia, central government support is currently limited due to the size of the SDI cabinet that, at the time of this writing, employs only one staff member for the whole country. Limited leadership that would include OGD process feedback from subnational government levels further inhibits OGD development in Indonesia. Our findings show that BAPPENAS uses a top-down carrot-and-stick approach to hasten SDI implementation by setting milestones and key performance indicators for national and subnational government bodies. Furthermore, BAPPENAS’ leadership requires additional technical expertise to lead SDI policy and evaluation.

Comparison with other developing countries

Our findings have implications for other developing countries. Cañares and Shekhar (Citation2016) studied nine developing countries and found that an enabling environment for open data is needed for OGD growth. Indonesia’s experience shows that an enabling environment for open data depends on the interplay of the elements of policy and strategy, organizational arrangements, and legislative foundations. A disconnection between initial discourse and implementation guidelines may appear without a tandem operation of these three institutional dimensions. Srimarga et al.’s (Citation2014) research in Indonesia’s Ministry of Finance confirmed such a disconnect between the initial project goals for budget transparency and implementation guidelines.

Compared with three transition countries—Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine—where external actors and funding played a crucial role in driving capacity building in governmental organizations and NGOs and increasing public awareness (Safarov, Citation2020), Indonesia is currently lacking in focus on public awareness of SDI and digital literacy more broadly. Efforts to improve digital literacy in Indonesia have been described as “voluntary, incidental and sporadic” by researchers who engaged in a digital literacy mapping project in nine cities between 2010 and 2017 (Kurnia & Astuti, Citation2017), further inhibited by issues with data security and citizen trust (Haryanto, Citation2023). This is further confirmed by research studies that map existing digital and statistic literacy capabilities even at the level of agencies implementing SDI (Riwukore et al., Citation2021). OGD implementation in Indonesia further showcases the lack of recursive feedback, where OGD guidelines are top-down, as shown in .

Indonesia’s experience underscores the need for policymakers in developing countries to establish a unified data governance mechanism early in the OGD development process to avoid data silos and underutilization. Such a standard would guide government agencies and external beneficiaries on how to collect, process, use, share, and publish data. Second, policymakers could establish a task force or consortium vested with complete organizational and legal authority to implement OGD, instead of creating a new agency that might lack adequate resources. This approach would streamline bureaucracy and offer flexibility to foster OGD development. The taskforce could comprise multidisciplinary experts from government agencies, research institutes, and civil society. This arrangement could enhance organizational collaboration and OGD interoperability among government agencies at both national and subnational levels.

These findings extend beyond Indonesia, suggesting broader challenges and lessons learned in OGD initiatives in developing countries. It is crucial to emphasize the need for comprehensive OGD planning and consultations before incentivizing extensive data-sharing. Incentives tied to data-sharing may be counterproductive if practices of data governance and internal feedback loops across different levels of government are not in place. Scholarly literature on OGD preparation, implementation, and value generation, like Jetzek’s (Citation2016) process model of open data supply and value creation, could enhance OGD initiatives before nationwide launches.

This study identifies two limitations that present opportunities for future research. First, the theoretical framework focusing on institutional dimensions predominantly addresses nation-level OGD implementation, potentially neglecting nuanced international dynamics. Future studies could explore cross-country comparisons across developed and emerging nations, adopting an international perspective. Researchers may also employ interdisciplinary approaches to investigate the involvement of companies in OGD initiatives. For instance, integrating an international business lens could examine how OGD supports multinational companies in decision-making processes related to expansion, such as location choice and strategy development (Hasan & Ojala, Citation2024). Second, our nation-level analysis prevented detailed examination of interactions within provinces or regions, limiting insights into comparisons at provincial or regional levels.

Conclusion

This study employed institutional dimensions as a central theoretical lens to analyze the development of SDI. Indonesia’s OGD focus centered on the SDI initiative, which was formally initiated through a presidential regulation in 2019 and culminated in the SDI government data portal launch in December 2022. Our in-depth research, however, uncovered structural challenges in SDI implementation. The key institutional dimensions of policy and strategy, organizational arrangements, and legal foundations emerged as crucial elements requiring attention to address gaps between top-down directives and actual implementation. We identified leadership gaps in setting clear policy and strategy guidelines, collaboration in implementation, and acquiring technical expertise for nationwide standards as urgent concerns. Furthermore, the study revealed a significant overlap between organizational arrangements and legal foundations, particularly evident in the limited legal responsibility setting of the presidential decree that initiated SDI. Last, this study highlights the absence of efforts by SDI officials to promote SDI use and emphasizes the need for sustained attention to technical and skills training in SDI implementation.

In addressing regulatory requirements, policymakers are urged to develop a binding framework supporting the activities of task forces responsible for standard data management policies within government agencies. Gradual legislative changes are recommended to align and harmonize existing laws and regulations with emerging standard data management policies. Incremental legislative development is proposed to reduce organizational friction and contradictions, fostering successful OGD implementation and facilitating data-driven value creation. These results go beyond Indonesia, pointing to more general difficulties and lessons discovered in OGD projects in developing countries. It is crucial to ensure extensive OGD planning and consultations before mandating extensive data-sharing.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ausma Bernot

Ausma Bernot is a Lecturer in Criminology at the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Griffith University. Her research focuses on the intersection of technology and crime, with a particular focus on surveillance and technology governance.

Dian Tjondronegoro

Dian Tjondronegoro is a Professor in Business Strategy and Innovation, specializing in AI for eHealth systems and focusing on personalized health promotion, interventions for substance abuse, and chronic pain management. Leading the “live” theme at Griffith Inclusive Future Beacon, his work contributes to inclusive, healthy, and technologically enhanced urban environments. Collaborating with Australia’s health sectors for more than a decade, he leverages AI, mobile-cloud computing, and IoT technologies to advance eHealth systems. Dedicated to the ethical application of AI, Prof. Tjondronegoro advocates for privacy, transparency, and responsible computing practices and leads the “Governing in the Digital Age” course for policymakers from various Asian countries. His expertise spans AI, cloud, and mobile technologies, with more USD 10 million in funding secured and more than 145 peer-reviewed scientific articles authored. Committed to applied research and inclusive development, he is a Fellow of ACS and Senior Member of IEEE and ACM and received the Gold Disrupters award from the Australian Computer Society in 2019.

Bahtiar Rifai

Bahtiar Rifai is the head of a research group for knowledge-based economy at the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) of the Republic of Indonesia. His research focuses on the digital economy, digital MSMEs, digital government, and technology and innovation economics.

Rakibul Hasan

Rakibul Hasan is a Doctoral Researcher in International Business at the University of Vaasa, Finland. Hasan’s research is at the cross-section of space, artificial intelligence, international business, information systems, management, and sustainable development. He obtained his master of science in Business Administration and Economics at Aalborg University, Denmark.

Alan Wee-Chung Liew

Alan Wee-Chung Liew is a Professor of Computer Science, Head of School of ICT, and Deputy Director of the Institute for Integrated and Intelligent Systems at Griffith University. His research interests are predominantly in the field of AI and machine learning, medical informatics, and computer vision. He has published extensively in these areas and is the author of two books and more than 300 journal and conference papers. Prof. Liew has obtained many prestigious nationally competitive research grants from Australia, Hong Kong, China, the United States, and the United Kingdom, with a total funding of more than A$10 million. He has also engaged actively in professional activities, such as on general chair or program chair of many international conferences, on the editorial board of several top-ranked AI journals such as IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems. He is Fellow of ACS, Fellow of Queensland Academy of Arts and Sciences, and senior member of IEEE.

Tom Verhelst

Dr Tom Verhelst is a leader in data analytics, digital technology, and IT management with a mission to democratize data for decision intelligence. As the Director of Griffith Data Trust (GDT) and Relational Insights Data Lab (RIDL) at Griffith University, he aims to establish a nationally relevant information ecosystem. Verhelst focuses on creating data analytics products and commercializing machine learning and AI data solutions, all to enhance decision-making for business and government clients. He helps shape GDT’s and RIDL’s strategic direction as a pivotal resource for storing, managing, and analyzing large, sensitive datasets, crucial for human and environmental development across a wide range of sectors. He offers a platform for data-driven decision-making and initiative evaluation.

Milind Tiwari

Milind Tiwari is a researcher and lecturer in financial crime studies at the Australian Graduate School of Policing and Security, Charles Sturt University. His work focuses on various facets of money laundering, including the role of technology and databases in detecting and deterring it.

Notes

1 Law Number 14/2018 about Public Information Disclosure; Presidential Regulations of Republic of Indonesia Number 95/2018 about Electronic-Based Government System (EBGS or SPBE); Presidential Regulations of Republic of Indonesia Number 39/2019 about Satu Data Indonesia (SDI) or One Data Indonesia (ODI); Ministerial Decree of National Development Planning Agency (BAPPENAS) Number EP.115/M.PPN/HK/07/2022 about Establishment of One Data Indonesia Action Plan 2022–2024.

2 Echelons are positions in the organizational structure of Indonesia’s government. According to Government Regulation (PP) No. 13/2002, they consist of echelon I (the highest position at the level of deputy under the minister), echelon II (head of government implementing organization under the deputy), echelon III (at the level of head of field), and echelon IV (at the level of head of subfield or lowest level).

References

- Ahmadi, F., Ojo, A., & Curry, E. (2016). Exploring the economic value of Open Government Data. Government Information Quarterly, 33(3), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.008

- Alexopoulos, C., Saxena, S., Rizun, N., & Shao, D. (2023). A framework of Open Government Data (OGD) e-service quality dimensions with future research agenda. Records Management Journal, 33(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/RMJ-06-2022-0017

- Alonso, J. A., Boyera, S., Grewal, A., Iglesias, C., Pawelka, A. (2013). Open Government Data: Readiness assessment Indonesia. https://webfoundation.org/research/open-government-data-readiness-assessment-indonesia/

- Altayar, M. (2018). Motivations for open data adoption: An institutional theory perspective. Government Information Quarterly, 35(4), 633–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.09.006

- Ancarani, A. (2005). Towards quality e‐service in the public sector: The evolution of web sites in the local public service sector. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 15(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520510575236

- Attard, J., Orlandi, F., Scerri, S., & Auer, S. (2015). A systematic review of Open Government Data initiatives. Government Information Quarterly, 32(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.07.006

- Bates, J. (2014). The strategic importance of information policy for the contemporary neoliberal state: The case of Open Government Data in the United Kingdom. Government Information Quarterly, 31(3), 388–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2014.02.009

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2016). (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 19(6), 739–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1195588

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Cahlikova, T., & Mabillard, V. (2020). Open data and transparency: Opportunities and challenges in the Swiss context. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(3), 662–686. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1657914

- Caley, M. J., O’Leary, R. A., Fisher, R., Low-Choy, S., Johnson, S., & Mengersen, K. (2014). What is an expert? A systems perspective on expertise. Ecology and Evolution, 4(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.926

- Cañares, M. P., & Shekhar, S. (2016). Open data and subnational governments: Lessons from developing countries. The Journal of Community Informatics, 12(2), 99–119. https://doi.org/10.15353/joci.v12i2.3242

- Chatfield, A. T., & Reddick, C. G. (2017). A longitudinal cross-sector analysis of open data portal service capability: The case of Australian local governments. Government Information Quarterly, 34(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2017.02.004

- Cho, J., & Lee, B. (2022). Creating value using public big data: Comparison of driving factors from the provider’s perspective. Information Technology & People, 35(2), 467–493. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-04-2019-0169

- Collins, C. S., & Stockton, C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 160940691879747. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918797475

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Dawes, S. S., Vidiasova, L., & Parkhimovich, O. (2016). Planning and designing Open Government Data programs: An ecosystem approach. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.01.003

- Directorate General of Information Applications. (2021, April 29). SPBE Links 2700 Government Agency Data Centers. https://aptika.kominfo.go.id/2021/04/dirjen-aptika-spbe-satukan-2700-pusat-data-instansi-pemerintah/

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- Flick, U. (2004). Triangulation in qualitative research. In U. Flick, E. von Kardoff, & I. Steinke (Eds.), A companion to qualitative research (pp. 178–182). Sage.

- Gascó-Hernández, M., Martin, E. G., Reggi, L., Pyo, S., & Luna-Reyes, L. F. (2018). Promoting the use of Open Government Data: Cases of training and engagement. Government Information Quarterly, 35(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2018.01.003

- Gonzalez-Zapata, F., & Heeks, R. (2015). The multiple meanings of Open Government Data: Understanding different stakeholders and their perspectives. Government Information Quarterly, 32(4), 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.09.001

- Haryanto, J. (2023). Indonesia: Advancing Southeast Asia’s largest digital economy.” In P. Cheung & T. Xie (Eds.) The ASEAN Digital Economy (pp. 42–75). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003308751

- Hasan, R., & Ojala, A. (2024). Managing artificial intelligence in international business: Toward a research agenda on sustainable production and consumption. Thunderbird International Business Review, 66(2), 151–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.22369

- Hermanto, A., Solimun, S., Fernandes, A. A. R., Wahyono, W., & Zulkarnain, Z. (2018). The importance of Open Government Data for the private sector and NGOs in Indonesia. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 20(4), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPRG-09-2017-0047

- Indrajit, A. (2018). One Data Indonesia to support the implementation of open data in Indonesia. In B. van Loenen, G. Vancauwenberghe, & J. Crompvoets (Eds.), Open data exposed (pp. 247–267). T.M.C. Asser Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6265-261-3_13

- Jacob, D. W., Fudzee, M. F. M., & Salamat, M. A. (2019). Analyzing the barrier to Open Government Data (OGD) in Indonesia. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering, 8(1.3), 136–139. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijatese/2019/2681.32019

- Janssen, M., Charalabidis, Y., & Zuiderwijk, A. (2012). Benefits, adoption barriers and myths of open data and open government. Information Systems Management, 29(4), 258–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530.2012.716740

- Jetzek, T. (2016). Managing complexity across multiple dimensions of liquid open data: The case of the Danish Basic Data Program. Government Information Quarterly, 33(1), 89–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.11.003

- Jugend, D., Fiorini, P. D. C., Armellini, F., & Ferrari, A. G. (2020). Public support for innovation: A systematic review of the literature and implications for open innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 156, 119985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119985

- Kassen, M. (2017). Open data in Kazakhstan: Incentives, implementation and challenges. Information Technology & People, 30(2), 301–323. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-10-2015-0243

- Kassen, M. (2018). Adopting and managing open data: Stakeholder perspectives, challenges and policy recommendations. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 70(5), 518–537. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-11-2017-0250

- Kassen, M. (2019). Open data and e-government? Related or competing ecosystems: A paradox of open government and promise of civic engagement in Estonia. Information Technology for Development, 25(3), 552–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/02681102.2017.1412289

- Kurnia, N., & Astuti, S. I. (2017, September 26). Researchers find Indonesia needs more digital literacy education. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/researchers-find-indonesia-needs-more-digital-literacy-education-84570

- Maail, A. G. (2017). The relational impact of open data intermediation: Experience from Indonesia and the Philippines. In F. v. Schalkwyk, S. G. Verhulst, G. Magalhaes, J. Pane, & J. Walker (Eds.), The social dynamics of open data (pp. 153–166). African Minds. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/28912/1/9781928331568_txt.pdf#page=161

- Maarif, S. (2020, September 7). Regulation and Integration of Electronic-Based Government Systems. Ministry of Religion of Indonesia. https://archive.md/TqScX

- Matheus, R., & Janssen, M. (2020). A systematic literature study to unravel transparency enabled by Open Government Data: The window theory. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(3), 503–534. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1691025

- Nusapati, C. A., & Sunindyo, W. D. (2017). Semi-automated data publishing tool for advancing the Indonesian Open Government Data maturity level case study: Badan pusat statistik Indonesia [Paper presentation]. 2017 International Conference on Data and Software Engineering (ICoDSE) (pp. 1–6). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICODSE.2017.8285887

- OECD & United Cities and Local Governments. (2016, October). Indonesia: Country profile. https://www.oecd.org/regional/regional-policy/profile-Indonesia.pdf

- Pan, T., & Fan, B. (2023). Institutional pressures, policy attention, and e-government service capability: Evidence from China’s prefecture-level cities. Public Performance & Management Review, 46(2), 445–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2023.2169834

- Parung, G. A., Hidayanto, A. N., Sandhyaduhita, P. I., Ulo, K. L. M., & Phusavat, K. (2018). Barriers and strategies of Open Government Data adoption using fuzzy AHP-TOPSIS: A case of Indonesia. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 12(3/4), 210–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-09-2017-0055

- Piotrowski, S. J. (2017). The “Open Government Reform” movement: The case of the Open Government Partnership and U.S. transparency policies. The American Review of Public Administration, 47(2), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074016676575

- Piotrowski, S., Grimmelikhuijsen, S., & Deat, F. (2019). Numbers over narratives? How government message strategies affect citizens’ attitudes. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(5), 1005–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2017.1400992

- Purwanto, A., Zuiderwijk, A., & Janssen, M. (2020). Citizen engagement with Open Government Data: Lessons learned from Indonesia’s presidential election. Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy, 14(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-06-2019-0051

- Radjawali, I., & Pye, O. (2015). Counter-mapping land grabs with community drones in Indonesia. Proceedings of the Land Grabbing, Conflict and Agrarian—Environmental Transformations: Perspectives from East and Southeast Asia (pp. 5–6), Chiang Mai, Thailand.

- Riwukore, J. R., Marnisah, L., Habaora, F. H. F., & Yustini, T. (2021). Implementation of One Indonesian Data by the Central Statistics Agency of East Nusa Tenggara Province. Jurnal Studi Ilmu Sosial dan Politik, 1(2), 117–128. https://penerbitgoodwood.com/index.php/Jasispol/article/view/1194/264 https://doi.org/10.35912/jasispol.v1i2.1194

- Ruijer, E., Détienne, F., Baker, M., Groff, J., & Meijer, A. (2020). The politics of Open Government Data: Understanding organizational responses to pressure for more transparency. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(3), 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074019888065

- Safarov, I. (2019). Institutional dimensions of Open Government Data implementation: Evidence from the Netherlands, Sweden, and the UK. Public Performance & Management Review, 42(2), 305–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2018.1438296

- Safarov, I. (2020). Institutional dimensions of Open Government Data implementation: Evidence from transition countries. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(6), 1359–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2020.1805336

- Safarov, I., Meijer, A., & Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2017). Utilization of Open Government Data: A systematic literature review of types, conditions, effects and users. Information Polity, 22(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-160012

- Sanina, A. (2024). City managers as digital transformation leaders: Exploratory and explanatory notes. Public Performance & Management Review, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2024.2302059

- Schmidt, V. A. (2008). Discursive institutionalism: The explanatory power of ideas and discourse. Annual Review of Political Science, 11(1), 303–326. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060606.135342

- Schrock, A., & Shaffer, G. (2017). Data ideologies of an interested public: A study of grassroots Open Government Data intermediaries. Big Data & Society, 4(1), 205395171769075. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717690750

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Skjott Linneberg, M., & Korsgaard, S. (2019). Coding qualitative data: A synthesis guiding the novice. Qualitative Research Journal, 19(3), 259–270. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-12-2018-0012

- Soegiono, A. N. (2018). Investigating digital (dis) engagement of open government: Case study of One Data Indonesia. JKAP (Jurnal Kebijakan Dan Administrasi Publik)), 22(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.22146/jkap.31848

- Srimarga, I. C., Suhaemi, M. A., Narhetali, E., Wahyuni, I. N., & Rendra, M. (2014, November). Open Data Initiative of Ministry of Finance on national budget transparency in Indonesia. http://hdl.handle.net/10625/55348

- Syarif, A., Salamat, M. A., & Syafari, R. (2020). A comparative analysis of Open Government Data in several countries: The practices and problems. Proceedings from the Recent Advances on Soft Computing and Data Mining Conference. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36056-6_33

- Tjondronegoro, D., Liew, A. W.-C., Verhelst, T., Green, D., Bernot, A., Hasan, R., & Rifai, B. (2022). The state of open data implementation in Indonesia. https://www.griffith.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/1610393/RO70-Tjondronegoro-et-al-web.pdf

- Tundjungsari, V. (2022). Open health data development for machine learning-based resource sharing: Indonesia case study. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 6(2). https://ijair.id/index.php/ijair/article/view/581

- United Nations. (2020). World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP2020_Annex.pdf

- United Nations Climate Change. (2015). Drones for justice: Inclusive technology for rainforest and promoting social-ecological justice—Indonesia. https://unfccc.int/climate-action/momentum-for-change/activity-database/drones-for-justice-inclusive-technology-for-rainforest-and-promoting-social-ecological-justice

- Vetrò, A., Canova, L., Torchiano, M., Minotas, C. O., Iemma, R., & Morando, F. (2016). Open data quality measurement framework: Definition and application to Open Government Data. Government Information Quarterly, 33(2), 325–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2016.02.001

- Wang, V., & Shepherd, D. (2020). Exploring the extent of openness of Open Government Data—A critique of Open Government Datasets in the UK. Government Information Quarterly, 37(1), 101405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2019.101405

- Wirtz, B. W., Weyerer, J. C., & Rösch, M. (2018). Citizen and open government: An empirical analysis of antecedents of Open Government Data. International Journal of Public Administration, 41(4), 308–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2016.1263659

- Zhang, H., Bi, Y., Kang, F., & Wang, Z. (2022). Incentive mechanisms for government officials’ implementing Open Government Data in China. Online Information Review, 46(2), 224–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/OIR-05-2020-0154

- Zhao, Y., Liang, Y., Yao, C., & Han, X. (2022). Key factors and generation mechanisms of Open Government Data performance: A mixed methods study in the case of China. Government Information Quarterly, 39(4), 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2022.101717