?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The question of what is the right amount of managerial autonomy has been widely debated. The new public management movement argues that increased autonomy will be used by managers to improve organizational performance. Skeptics argue that managers in the public sector are likely to shy away from using increased autonomy. To bring the literature forward we theorize the link between reforms awarding managers increased autonomy and subsequent organizational performance outcomes. We identify four steps in this causal chain, which are easily conflated. We demonstrate empirically the potential of focusing on the intermediary mechanisms of increasing managerial autonomy. A large-scale municipal amalgamation reform in Denmark provides a unique opportunity to study the immediate impacts of changes in managerial autonomy in public schools. The results indicate that granting public managers more freedom has intermediary effects on factors such as hiring patterns and organizational demographics.

Introduction

The role of discretion, or autonomy, for the work of public managers has been debated throughout the history of the public administration discipline. The roots of the debate can be traced back to Max Weber’s (Citation1970 [1922]) work in Europe and the progressive reform movement in the USA in the late 19th century (Knott & Miller, Citation1987). Heated arguments in favor of freedom for public managers have been made by both the scientific management school and the new public management movement. Counter-arguments have been made by scholars emphasizing the distinct characteristics of public management as opposed to private management (Moynihan, Citation2006; Walker & Andrews, Citation2015).

Organizational autonomy is a multifaceted phenomenon. Verhoest et al. (Citation2004) argue that it has six dimensions. Here, we focus on what Verhoest et al. (Citation2004: 105) call ‘managerial autonomy’, i.e. delegation of competences from the center “concerning the choice and use of inputs”. While autonomy has been an object of continuous research attention over the years, even recent studies yield mixed findings. For instance, using data from 20 European countries, Hammerschmid et al. (Citation2019) find no effect of creating autonomous agencies on public service performance, Pollitt and Dan (Citation2013) find mixed results in a review of 519 studies of NPM reforms, and Overman and Van Thiel (Citation2016) find even negative effects of agencification. Overall, we find in a survey of the literature that results concerning outcomes of managerial autonomy are overwhelmingly mixed or inconclusive (e.g. Andrews et al., Citation2011; Boyne, Citation2002; Walker & Andrews, Citation2015). We argue that this state of affairs is primarily due to two challenges, one related to the causal chain and one related to the variation in the independent variable. We label the first challenge the ‘long-causal-chain problem’. Many studies seeking to identify the impact of managerial autonomy focus on some measures of the performance of the manager’s organization, but other focus on outcomes and processes (Pollitt & Dan, Citation2013: 16). We acknowledge that performance may be the ultimately interesting effect variable, however, null findings do not necessarily constitute proof of no effect of managerial autonomy. The chain linking managerial autonomy to performance is long and a lack of an observable ultimate effect may be due to half-hearted implementation of reforms, or the fact that performance is more strongly affected by other factors than managerial behavior. Little research is occupied with the managerial behavior that is likely to be the most immediate outcome of increasing or decreasing autonomy. One exception is George et al. (Citation2019) who, based on data from 18 countries, report a positive relationship between hierarchical level and reported use of ‘organization-oriented tools’. This indicates that greater decision power may be visible in managerial action within the organization. However, hierarchical level is merely a proxy for autonomy, and we need further disaggregation of managerial action to better understand how autonomy is used. In another study, Wynen and Verhoest (Citation2016) find no relation between autonomy and use of performance-based steering mechanisms suggesting that autonomy may be used for different types of organizational initiatives.

The second challenge is limited variation in the independent variable of interest, managerial autonomy. Autonomy of managers is a fundamental aspect of an organization, and although dramatic changes happen, it is rare to see simultaneous changes in different directions for a large number of public managers. For instance, Bjørnholt et al. (Citation2022) show how local regulation affects perceived managerial autonomy, suggesting that external conditions are likely to affect organizations and their managers in similar ways making it difficult for researchers to study scenarios of exogenously imposed variation in managerial autonomy. Such variation in the independent variable is required to better understand the causal link between manager autonomy and organizational dynamics.

To bring the literature forward we argue that it is helpful to study a ‘most-likely’ case of the effect of managerial autonomy. Thus, the contribution of this article is to address the two problems mentioned above. A first step is theorizing the link between reforms awarding managers increased autonomy and subsequent organizational outcomes. We identify four overall steps in this causal chain, which often are conflated in existing research obscuring our understanding of the mechanisms linking managerial autonomy to outcomes. We argue that separating the steps in this process and focusing on the outcomes directly linked to managerial autonomy can help generate new insights.

In the empirical part of the paper, we demonstrate the potential of focusing on the intermediary mechanisms of increasing managerial autonomy. A Danish municipal amalgamation reform provides substantial variation in managerial autonomy in public schools. Before the amalgamations, school managers were subject to delegation rules in their pre-reform municipalities. Following reform, every amalgamated municipality was forced to change the autonomy of school managers within its jurisdiction, to ensure that similar rules apply to its schools. Because the schools came from different pre-reform municipalities, changes in autonomy were large, and in different directions, with some achieving more autonomy, others less. Although we focus on schools, we study two aspects of managerial autonomy relevant to most public institutions, namely autonomy to make financial and personnel resource decisions. The results indicate that granting managerial autonomy has effects on factors like hiring patterns and organizational demographics.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we outline the theoretical debate on the effects of increasing managerial autonomy. Second, we survey the empirical literature and demonstrate that findings are mixed or inconclusive. Third, we discuss why this is the case and argue that the most likely reason has to do with the two challenges presented above. Fourth, we introduce an amalgamation reform of Danish local government and explain why it generated change in autonomy of public-school managers. Fifth, we report the results of our analysis before concluding the paper.

Theory: The role of autonomy for public managers

Verhoest et al. (Citation2004) argue that it is important to distinguish between different forms of organizational autonomy, as the concept has several distinct aspects that do not necessarily correlate with each other. We focus on managerial autonomy, which Verhoest et al. (Citation2004: 105) describe in the following way: “When agencies have some decision-making competencies delegated from the center concerning the choice and use of inputs then they have some degree of managerial autonomy. This implies that agencies are exempted from certain rules and regulations concerning input management which traditionally enhance the legality and economy of governmental transactions and constrain managerial discretion. An agency can have managerial autonomy with respect to financial management (…), human resources management (…) or the management of other production factors (…)”. Importantly, previous research (e.g. Ammons & Roenigk, Citation2020; Bjørnholt et al., Citation2022) has argued that perceived managerial autonomy may be different from actual or formal autonomy. Formal autonomy is the officially recognized independence granted to managers within an organization’s framework indicating the theoretical or legally given rights and freedoms they possess. On the other hand, perceived or actual autonomy involves the real-world application and use of this autonomy by managers in their professional settings. In the method section, we will detail how the complex concept of autonomy is operationalized in our empirical study.

The question of the pros and cons of granting organizational autonomy has been debated throughout the history of the public administration discipline. Max Weber, the German sociologist and founder of the modern study of bureaucracy, saw little room for managerial autonomy. He insisted on strict delimitation by rules partly to secure managerial accountability and loyalty, partly because he was deeply distrustful of bureaucrats and well-aware of “the pure interest of the bureaucracy in power” (Weber, Citation1970 [1922]: 233). In contrast, the progressive reform movement in the USA in the late 19th century wanted to break with public administrations being used as political machines and instruments for political graft and corruption. They therefore pushed for a nonpartisan civil service, more professionalism and, most importantly, a separation of administration from politics (Knott & Miller, Citation1987). For example, Goodnow argued that while the administration was to be clearly subordinate to politics, administrators should at the same time be allowed a certain degree of autonomy: “their general conduct, but not their concrete actions, should be subject to [political] control” (Goodnow, Citation1900: 81). This classic discussion of organizational autonomy is relevant for the modern discussion of managerial autonomy. Theoretically, this discussion draws upon principal-agent theory (Langbein, Citation2000), and thematically, it focusses on the new public management reforms (Pollitt & Dan, Citation2013; Overman & Van Thiel, Citation2016).

The argument from the new public management movement: Let managers manage

The term new public management, which became fashionable in the late 1970s, covers a number of overlapping precepts including hands-on professional management, explicit standards of performance, emphasis on output control, disaggregation, competition, and private-sector styles of management practice (Hood, Citation1991). Central to the new public management movement was to import insights from the private sector. This meant inter alia devolving authority to daily managers (Aucoin, Citation2011). Management in the public sector was seen as separate from politics and much alike management in the private sector. The basic idea is that new public management can increase performance and efficiency in three ways (Pollitt & Dan, Citation2013: 8). First, awarding more authority to managers (or in our terminology managerial autonomy) allows for better decisions because managers have better information about their own organization. Second, accountability in the form of performance measurement, performance pay, or quasi-markets gives managers incentives to use their autonomy to increase performance. Third, user choice will pressure managers to focus on better service.

These views draw on Goodnow’s politics-administration dichotomy. He found that the administration’s work constitutes the “scientific, technical, and so to speak, commercial activities of the government” (1900: 17), and that these activities should “be taken out of politics” (1900: 260). The doctrine of letting managers manage was eloquently argued by Osborne and Gaebler (Citation1992), who advocated that government be driven by mission rather than by rules:

Most public organizations are driven not by their mission, but by their rules and their budget. They have a rule for everything that could conceivably go wrong …Mission-driven organizations turn their employees free to pursue the organization’s mission with the most effective methods they can find (Osborne & Gaebler, Citation1992: 110, 113).

Skeptical counter-arguments: Public management is not like private management

The argument against the new public management ideas of importing management techniques from the private sector has firm roots in the literature on differences between public and private management, which can be traced back to Max Weber. He made a distinction between public-sector “bureaucratic authority” and private-sector “bureaucratic management” (Weber, Citation1970 [1922]: 196). In contrast to the latter, the former is regulated by rules, life-long employment and a continuous power play with politicians.

The literature on public-private differences never amounted to a movement like the new public management literature, but it existed as an insistent voice throughout the latter half of the 20th century (Parker & Subramaniam, Citation1964; Rainey et al., Citation1976). Allison and Second Edition (Citation1987 [1979]), drawing on Sayre et al. (Citation1958), famously summarized their findings in the statement that public and private management are “fundamentally alike in all unimportant respects”. The implication was that there is little point in seeking to draw lessons from management in the private sector. The implications were discussed at length by Wilson (Citation1989) who argued that the unique constraints of public organizations make their managers risk-averse, likely to worry more about processes than results, and to shy away from using increased managerial freedom. Politicians are careful when delegating competence to the administration (Huber & Shipan, Citation2002). If there is a high degree of policy differences between the political and administrative level, autonomy will be limited, or control mechanisms installed. This implies that it is simply not always possible in a public sector to set managers free (Huber & Shipan, Citation2002: 107), or that this freedom is not credible because politicians care about policy outcomes and seek to control them (Miller, Citation1992). Consequently, there are forceful counter arguments about the effects of turning managers free. You may let public managers manage, but it is difficult to make them manage.

Literarature review: What is the evidence about the consequences of managerial autonomy?

We now turn from theoretical propositions to evidence. We begin the review with Pollitt’s book from 1998, where he took stock of the literature. He evaluated the impact of internal management reforms in the public sector. His conclusion was that “managerialism’s empirical foundations are surprisingly flimsy. Compelling evidence for transformations of public sector performances is simply not yet there” (1998: 67; emphasis in original). In a later article, Pollitt and Dan (Citation2013) concluded from a review of 519 studies that findings are mixed, partly because the studies focus on different dependent variables (outcomes, output, and processes). About twenty-five years on we believe that this is still the case. Two recent studies show that management discretion can affect behavior (Andersen and Moynihan (Citation2016) show that discretion leads to more investment in expertise, and Cárdenas and Ramírez de la Cruz (Citation2017) that school principal discretion produces more efficient, but less equitable student distributions), but apart from that we have not been able to locate studies on the effect OF DISCRETION ON management behavior. A few studies explore how country variation in managerial autonomy affects broad public service outcomes (Hammerschmid et al., Citation2019), and how agencification matters for performance (Overman & Van Thiel, Citation2016). The different findings likely reflect differences in institutional traditions and are not set up to understand the organizational-level processes by which managers may or may not utilize autonomy. In addition to this, Pollitt (Citation1998) points out that internal management reforms are invariably but a small part of broader reforms, often undertaken in the name of new public management. These reforms are usually multifaceted. In addition to decentralizing managerial authority they may also reform budgeting systems, change IT systems, create executive agencies, separate purchasers from providers, set performance targets, empower customers, and change many other elements chosen from the new public management menu (Pollitt & Bouckaert, Citation2011; Moynihan, Citation2006). Isolating the effect of internal management reforms from other reform elements is obviously very demanding.

But what if we cast the net wider and look for evidence of the impact of new public management reforms in general – do we then get any wiser? The first observation to make from such an endeavor is that the number of studies explodes. There is simply an overwhelmingly large literature trying to estimate the effects of new public management reforms. So, we try to take stock by consulting survey studies – that is, we survey survey studies.

The result is presented in , where we report the main findings of survey studies. The results are relatively clear and can be summarized in three points. The first is that it has been difficult to find empirical evidence of effects of the public-private distinction within management. The second is that public management may make a difference, but not always. There are obviously important moderators. Whether the autonomy of managers is among them is not clear. Third, many of the authors of the survey studies worry about the methodological quality of the literature. We think that these findings give ground for pause. In the next section we discuss in more detail what could be the reasons for the mixed findings.

Table 1. A survey of survey studies of the impact of new public management reforms.

Why mixed findings?

The empirical literature provides mixed evidence of the outcomes of managerial autonomy (see also Bjørnholt, Boye and Mikkelsen Citation2022). Some reasons are conceptual, some methodological. We discuss, based on Moynihan (Citation2006), briefly some of the main conceptual reasons. We then examine the methodological reasons more closely. We conclude that the next logical step for the empirical literature is to focus on cases where the conceptual challenges are minimized, and focus on shorter causal chains. In the next section we identify an empirical case that is well-suited to addressing these problems.

Moynihan (Citation2006) discusses the ‘management for results’ doctrine, which involves higher management authority combined with an increased focus on results. This doctrine is a product of the ideas behind new public management: Managers should have clear goals, and they should be held accountable by measurement of results (cf. the focus on results); but authority should also be devolved to agencies (cf. increased management autonomy). Management for results can be seen as an ambitious attempt to implement new public management in the American public sector.

However, Moynihan (Citation2006) argues that this implementation largely failed. Based on survey data of U.S. states, Moynihan (Citation2006: 84) finds that while focus on results increased, managerial autonomy did not. While financial controls were typically formally increased, autonomy was in reality constrained. For example, authority to carry over cost savings across years was, when formally implemented, “usually subject to uncertain ex ante central permission” (2006: 82). Similarly, human resource autonomy remained heavily constrained. Since management for results failed to implement managerial autonomy, public managers lacked leverage to meet the promises of new public management. As Moynihan (Citation2006: 84) puts it: “the potential for performance systems in which managers seek to improve performance and are formally held accountable for results is undermined by the continued existence of financial and personnel control systems that emphasize compliance and error avoidance.”

Hence, an important reason for the mixed empirical findings could be that changes in managerial autonomy are not always fully implemented. An increase in managerial autonomy is merely a first step. It does not in itself produce a change in efficiency. To have such an effect, a reform must be implemented. If this second step is not taken, managerial autonomy is not changed in reality. When duly implemented, the third step is that the increased autonomy affects managers’ decisions or behavior. This is not an automatic process. Managers can choose to ignore increased autonomy, they can fail to understand what possibilities it gives, or they can find themselves constrained by others (such as employees, citizens, or users) in their use of the increased autonomy. Finally, the fourth step is that the change in behavior affects performance. This logic, which involves a chain of throughput, output and outcome, is illustrated in . The point is that the effect of (1) increased managerial autonomy must be mediated by (2) implementation, and then (3) change behavior in order to have an effect on (4) performance. In other words, the causal chain connecting managerial autonomy to performance is long, and the causal effect is indirect.

Studies of type (1) → (4) circumvent the intermediary mechanisms and examine the full causal chain. Positive findings provide evidence of an effect of managerial autonomy on performance. However, null findings may be explained by the lack of implementation or perhaps by a weak effect from change in behavior to performance (this could happen in organizations where performance is affected more strongly by other factors, often a reasonable assumption). An example of this type of study is Hammerschmid et al. (Citation2019) mentioned above. Studies of type (1) → (2) focus on implementation and say little about the substantial effects of managerial autonomy. There are a few examples of type (1) → (3), for instance George et al. (Citation2019) studying the relationship between autonomy and use of management tools. Type (3) → (4) investigate how different managerial strategies affect performance. This is an important research question, but it does not address the question of how structural changes in autonomy work as management behavior can have other antecedents.

In this study we seek to identify an empirical case which allows for a most-likely test of the effect of managerial autonomy. This implies a study of type (2) → (3). By measuring how increases in managerial autonomy are implemented, and how this affects changes in management behavior, we focus on the first condition of such reforms to work. To have a real effect on performance, they must first affect behavior. A positive finding would be evidence that reforms of managerial autonomy matter to real behavior. A null finding would be evidence against the notion that managerial autonomy matters, and it cannot be explained away by potentially broken links in a long, indirect causal chain.

A second problem challenging existing studies is limited variation in managerial autonomy. Autonomy and delegation rules are changed from time to time, but typically only for a few public managers or identical changes for a larger number of managers. This impedes quantitative studies of the effect of changes in autonomy. If changes only apply to a limited number of managers, the statistical power of the study will be low, and if the changes are identical for a large number of managers, it is hard to separate the effect of this change from other concurrent developments. A most-likely study will ideally require large variation in the independent variable of interest. In the next section we discuss how a large-scale amalgamation reform of Danish local government provides exactly this variation.

Reform-induced change in managerial autonomy in Danish elementary schools

In the empirical analysis, we focus on Danish elementary schools for two reasons. First, managerial autonomy has changed substantially for Danish school managers during the last decades. Many of these changes have been sparked by one particular event: The Danish local government amalgamation reform of 2007. We argue below that this reform has generated large variation in management autonomy, allowing for at most-likely study of the effect of this independent variable. Second, the case of Danish elementary schools allows for a study of type 2 → 3 (also as discussed above). Danish schools are, of course, not statistically representative of public schools worldwide, let alone public organizations worldwide. Context should be taken into account, and broader lessons drawn with caution (cf. Heinrich, Citation2012). However, given the opportunity to alleviate the long-causal-chain problem and to study large-scale changes in managerial autonomy, a study of Danish schools allows promising analytical generalization (Yin, Citation1989).

Denmark is a highly decentralized unitary state (Boadway & Shah, Citation2009). Municipalities are governed by elected city councils and mayors elected among local councilors. The municipalities are multipurpose units responsible for a broad range of welfare services, including public schools for primary education, and the municipalities also decide how much autonomy should be granted to school leaders. The amalgamation reform of 2007 changed the municipal landscape in Denmark: 271 municipalities were by law amalgamated into 98. Of the 271 municipalities, 32 were allowed to continue without amalgamation. The remaining 239 municipalities were amalgamated into 66 new units, bringing the total down to 98. The reform was swift (see detailed descriptions in Blom-Hansen et al., Citation2014; Mouritzen, Citation2010). Case studies of individual amalgamation processes suggest that particularly questions of local identity, internal cohesion, the likely party-political composition of the future municipality, homogeneity in service and wealth, and, not least, ambitions of becoming an influential player in the future municipal structure were important determinants (Mouritzen, Citation2006). A quantitative study of potential determinants shows that commuting patterns are the best predictor of amalgamation decisions (Bhatti & Hansen, Citation2011). Importantly, the fit of internal governance mechanisms, such as the amount of managerial autonomy, was not important in explaining mergers meaning that subsequent changes were largely exogenous to the reform.

Ten years of primary education is compulsory in Denmark. Parents can choose between public or private schools (home teaching is also an option, but rarely used). About 80 per cent of all children are enrolled in public schools. These schools are regulated by laws stipulating what subjects to be taught, exams and other assessments, but they are governed by the municipalities, which are responsible for supervision, quality and availability, and division of the municipality into administrative school districts, including the number of public schools. The municipalities fund the public schools from local income taxes (OECD, Citation2011: 25). In 2019, Denmark has almost 1,100 public schools, and the average school size is just below 500 pupils. The average annual cost per pupil is among the highest in OECD (OECD, Citation2013: 162-164) and amounts to approximately DKK 60,000, at that time corresponding to about USD 11,000.

The role and competences of school leaders is defined in the Danish Public School Law. For instance, according to this law, the school leader has the competence to direct and distribute the work among teachers and other employees at the school, and to make specific decisions regarding pupils. These decisions cannot, if they are legal and within the general rules specified by the municipality, be challenged or changed by the municipality. In contrast to the United States, schools do not belong to independent school districts. Each school reports independently to the elected municipal council, which has the legal prerogative to delegate further competencies to individual schools. Consequently, school leaders have a position akin to agency managers with considerable responsibility for school operations. Depending on the level of autonomy delegated, school managers, outside pedagogical responsibility, have a range of traditional POSDCORB responsibilities (Gulick, Citation1937), including notably budgeting, staffing, and planning. As such, it is a setting where managers have a real opportunity to react to increased autonomy as noted in previous research (Bjørnholt et al., Citation2022). As we explain below, we will study outcomes closely related to the POSDCORB responsibilities to assess consequences of increased autonomy.

We focus on autonomy in financial and staffing decisions as shown in . These elements of managerial autonomy are important to the schools as they are to most organizations. In a previous study of autonomy in Danish schools (Bjørnholt et al., Citation2022), a similar approach was used, however the present study puts more weight on economic authority to transfer surplus or deficits, where Bjørnholt and colleagues put emphasis on organization of teaching. Further our measure resembles previous research (e.g. Boon and Wynen Citation2017; Krause and van Thiel 2019). Consistent with the definition provided earlier, our indicators are meaningful elements of autonomy as they concern the allocation of responsibility between schools and their political and administrative principals.

Table 2. Elements of managerial autonomy.

Public schools within a given municipality are - except in rare cases - subject to the same rules about delegation of management autonomy. For example, if a municipality decides to allow schools to transfer unused funds from one budget year to the next, they do so for all schools. If a municipality does not allow a school leader to hire a new teacher without approval, all schools within the municipality will be subject to this rule. In other words, when managerial autonomy changes, it changes for all schools within a municipality. While actual and perceived autonomy rarely will be perfectly correlated, our survey measure reports managers’ perception of the formal autonomy they are granted on different areas of importance to their work, which we argue is most relevant to understanding managerial outcomes.

Research design

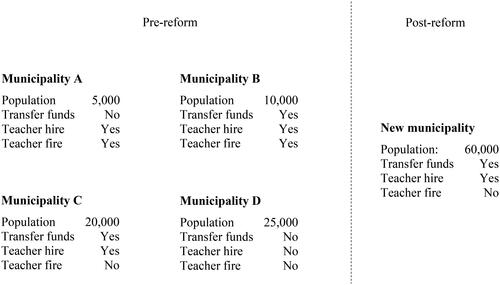

Our focus is schools in the 239 municipalities that were amalgamated in the municipal reform and forced to revise their rules on the extent of managerial autonomy. This generated large variation in changes in managerial autonomy, which we utilize in this study. Consider which illustrates the situation in a new post-reform municipality formed of four pre-reform municipalities. In this example, the pre-reform municipalities were organized differently. Municipality B and C allowed school leaders to transfer funds between budget years, A and D did not. All municipalities expect D allow leaders to hire teachers. A and B also allowed leaders to fire teachers, C and D did not. The new municipality, formed from A, B, C, and D, adopted the practice from municipality C and conferred substantial competences to its school leaders.

The strength of the research design lies in the fact that the reform forced the municipalities to make changes in managerial autonomy. The new municipality was forced to settle on particular rules for all the schools within the newly formed municipality. This requires that rules are harmonized, which again requires different changes for schools located in different pre-reform municipalities. Notably, the design is further fueled by the opportunity to compare schools within the same new municipality experiencing different changes to their autonomy as a result of the amalgamation (e.g. comparing schools from municipality B and D in the example above experiencing very different degrees of change to their management autonomy). This means that contextual factors such as geography, local labor market dynamics, and political leadership are effectively controlled in estimations.

Data and methods

The Danish reform generated large change in managerial autonomy in schools. The availability of fine-grained register data makes it possible to also handle the problem of long causal chains. Instead of focusing on the ultimate effect on performance, we study immediate effects, namely the impact on management behavior. As we argue above, this constitutes a most-likely test of the effect of managerial autonomy.

Data

We build a dataset based on two sources. First, we use register data from the Integrated Database for Labor Market Research (IDA) hosted by Statistics Denmark. IDA consists of matched employer-employee data gathered by Statistics Denmark based on different public registers. It provides highly reliable data on actors in the Danish labor market as well their workplaces with annual observation ranging back to 1980 (Timmermans Citation2010). The database is perfectly suited for our purpose as it allows us to estimate a variety of labor market outcomes at the school level. We will explain our variables in detail below. Second, to capture changes in autonomy, we use unique survey data to measure our independent variable as described below. Our units of analysis are public schools in municipalities involved in amalgamations in the reform in 2007. In total, our sample consists of 694 schools, which can be linked to their before and after reform municipality of location (Supplementary Appendix 1 describes how schools are identified in the register data).

Independent variable

In order to assess the degree of managerial autonomy implemented in a given municipality before and after the reform, we collected retrospective data in 2014. Based on expert interviews, we focused on three dimensions of autonomy (cf. ): i) The right to transfer surplus between years, ii) the right to transfer deficits between years, and iii) the discretion to hire and fire employees. To identify the spectrum between low and high degrees of autonomy, we identified the most common models in use for these three dimensions (see Supplementary Appendix 2). An example is the right to transfer budget surplus where we use four options ranging from “No surplus can be transferred” to “surplus can be transferred with no limitations”.

To minimize recall bias, we contacted three key informants from each municipality (Kumar et al., Citation1993), and asked about relatively overall principles, which were very salient for the managers at the time. Because the reform was so comprehensive, it provides a clear cognitive demarcation between “before” and “after”. We included an option to answer “do not remember” but very few used this option reinforcing confidence in the validity of the data.

In each old municipality, we identified three school managers as key informants and surveyed them about municipal control of schools before the reform. In the same way, we identified informants in the new municipalities to gather information about managerial autonomy after reform. If a manager from an old municipality proceeded to a managerial position in a new municipality, he/she informed about both. In total, we received 448 responses to our survey. With these responses, we were able to cover 210 of the pre-reform municipalities (88% of the total). While we took great care in reaching respondents in all municipalities, we were unable to obtain data from a few. The main causes of nonparticipation were inability to identify relevant respondents and unwillingness to participate. We covered all 66 post-reform municipalities formed as a result of amalgamations. On average, we received 1.94 answers per municipality (range 1-3). In 61.6 percent of municipalities (new and old) all respondents fully agreed on their answers to our questions. In further 26,2 percent of the cases there was only a single scale-point difference between respondents. Given the retrospective nature of the data, we interpret this to indicate an acceptable level of inter-rater reliability.

In order to create a variable indicating change in autonomy, we followed three steps to create a formative index. First, for each municipality (new and old) we constructed an aggregate score on each variable as a simple average of the expert informants surveyed. Second, we created a measure of change by subtracting the pre-reform (old municipality) score from the post-reform (new municipality) score. Finally, we constructed an index of change in autonomy, labeled Managerial Autonomy Change Index, by standardizing the scores and then adding them together.

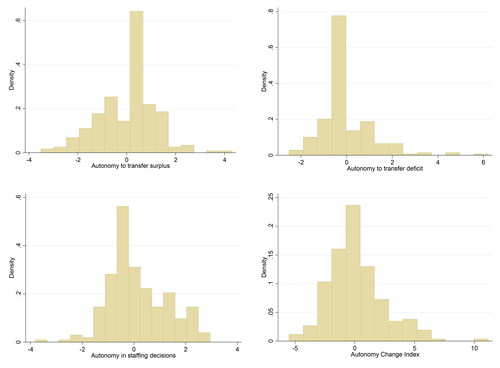

For a formative index the objective is to identify indicators that best represent the target topic (Blotenberg et al., Citation2022). These indicators may, but need not, be correlated. For our three indicators we observe correlations between 0.12 and 0.22. In , histograms show the dimensions in the index as well as final index. Positive values indicate a higher degree of autonomy following the reform.

It can be seen that most municipalities implemented changes in autonomy following the reform. As we expected this involved increased autonomy some places and decreased autonomy other places. When aggregated into the Managerial Autonomy Change Index, we observe a relatively broad distribution of change to autonomy (mean = 0.11; min = −5.50; max = 11.18).

While each of the dimensions in the index are in themselves important, we contend that they are only indicators of the degree of autonomy implemented in a municipality. If a manager is awarded more autonomy on these dimensions, it is likely accompanied by other factors and a distinct, possibly unobservable, value-based managerial culture in the municipality. Therefore, we proceed to use the aggregated Managerial Autonomy Change Index in the analyses.

Dependent variables

Measuring managerial behavior is a challenging task. We take point of departure in the POSDCORB responsibilities to include managerial decisions related to key organizational processes. Thus, we focus on three core elements of management behavior as dependent variables in the present study: 1) Staffing patterns, 2) Employment conditions, and 3) Organizational demography. All variables are based on the IDA register data.

Staffing is a key responsibility of managers. With more autonomy, managers can prioritize resources between salary and other activities such as staff development or purchase of new teaching materials. This means that autonomy cannot only affect the rate at which an organization grows (or shrinks) but also the composition of staff. In schools, a manager can choose how many teachers to recruit (as opposed to other personnel groups or non-educated teaching staff). They can also decide on the use of part-time staff, which may be cheaper but contribute less to the work climate and professional development (see Coggburn, Citation2000).

Employment conditions in workplaces are difficult to observe directly. We focus on employee turnover, which is related to the balance between continuity and getting fresh insights from outside (March 1991). Further, while salaries in public workplaces, like schools, in Denmark are rather fixed, a manager will still have some involvement in compensation. This involves not only how salary supplements are awarded but also maintaining the balance between more experienced staff higher on the salary ladder, and less experienced staff at lower levels. With more autonomy, a manager’s effect on such processes may increase.

Finally, autonomy may affect the demographic composition of employees. We focus on two key demographic characteristics, gender and age (measured as the proportion of women and the mean and spread of age). reports a summary of the dependent variables.

We use school-level data from the IDA registers of Statistics Denmark to calculate all the dependent variables. Each variable is defined for each school in each year of the study period. To avoid the influence of some extreme values, we winsorize the variables at the 1st and 99th percentile. Descriptive statistics are reported in Supplementary Appendix 3. While the eight dependent variables reflect different aspects of managerial work, they are only modestly correlated internally and constitute different outcomes of managerial behavior.

Estimation

While the reform provides a potentially valuable opportunity to explore managerial autonomy, it is important to note that a host of community factors may affect not only how much autonomy is granted school leaders but also how formal autonomy is translated into actual autonomy. In order to address this challenge, we utilize the clustered nature of the reform where different old municipalities are merged into the same new. In essence, the objective is to compare schools within the same new municipality that were subject to different degrees of change in the reform because they came from different old municipalities. To do this, we use fixed-effects for the new municipalities of every school. Thus, while holding constant factors such as geography, socio-economic demographics of local citizens, we utilize differences in the degree of change happening between schools located in different old municipalities becoming part of the same new municipalities.

Specifically, we employ a difference-in-difference design comparing schools before and after the reform and for different levels of change. While we do not claim that the reform is a perfectly exogenous shock to managerial autonomy, we argue that it is useful and effectively addresses many of the issues faced by previous studies of outcomes of managerial autonomy. In Supplementary Appendix 4, we explore the parallel trends assumption of DID. It can be seen that schools with low and high levels of changes to autonomy appear to have roughly parallel trends for the dependent variables before the reform, whereas we see more divergent patterns after the reform, which we further explore in regressions below. We interpret this to support the validity of our data and research design.

For each of the eight outcome variables, we estimate the following regression:

where Y is the outcome of interest, time is an indicator before or after the reform. Note that

is a vector of new municipality dummies (fixed-effects) that specifies the model to compare within new municipality differences between schools coming from different old municipalities (and, hence, have different values on the Managerial Autonomy Change Index). School size varies substantially and may in itself affect the type of changes, which are made as well as outcomes. We include it in the model. We present two specifications of the time operator: a) a dummy variable denoting before or after reform, and b) time indicated as a series of time dummies that allow us to observe whether reform effects are delayed or in-/decrease in strength over time (Wang & Yeung, Citation2019). We include data from 2002 – 2010 allowing a five-year window before the reform and a three-year observation window.

Table 3. Outcome variables in the study.

We estimate the models using OLS regression to preserve comparability between the models. As robustness tests, we also estimated count outcomes using Poisson models and percentage scale outcomes using fractional regression analyses (Villadsen & Wulff, Citation2021).

Results

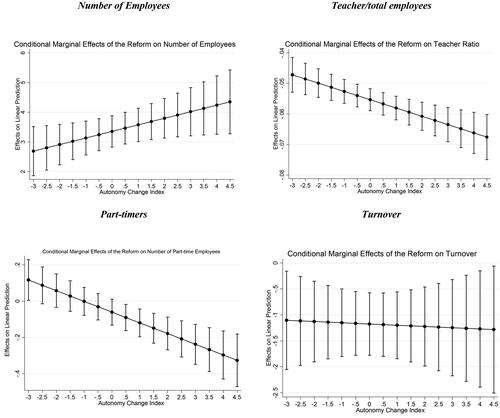

In a total of 16 models are presented. focuses on hiring patterns. Models 1 and 2 focus on staff growth indicated by the number of employees. In model 1, the interaction indicates that following the reform, schools with larger increases in autonomy appear to grow at a higher rate. This effect is graphically illustrated in . A school experiencing one standard deviation (2.51) positive change in autonomy is predicted to grow by around 0.5 positions after reform. For schools of most sizes this is a meaningful change. In model 2 it is suggested that this is a delayed effect as the interaction is not significant until 2010.

Figure 4. (a) Marginal effects of Managerial Autonomy Change Index.

Table 4. Difference-in-difference regressions predicting hiring patterns.

Table 5. Difference-in-difference regressions predicting employment conditions.

Table 6. Difference-in-difference regressions predicting demographic composition.

The interaction in model 3 suggests that increases in managerial autonomy is associated with the ratio of teachers decreasing. indicates that the teacher ratio is decreasing generally after reform, but more pronounced in schools with more managerial autonomy. Also, this effect appears not to be present until a few years after the reform.

Model 5 and 6 show that the use of part-timers is smaller in schools that experience increases in autonomy. This could suggest that more autonomous managers may focus on building a more coherent team and may be better able to effectively use the permanent staff. This effect is present immediately after the reform. indicates that schools experiencing no change in autonomy are predicted not to change the number of part-timers whereas a standard deviation (2.51) higher change index is associated with a decrease of almost two part-time employees. Together these results could suggest that managers experiencing higher degrees of change in autonomy utilize the opportunity to mix the number and types of employees in the school.

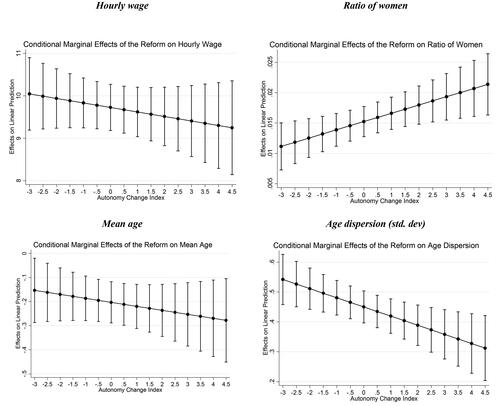

Turning to and employment conditions, the models suggest that turnover levels appear to be unaffected by changes in autonomy. This may reflect that schools in Denmark are not aggressive in recruiting staff from other schools. Similarly, we observe no indication that salary levels are different. Also, this may be explained by structural characteristics of the setting as school managers only have limited possibilities to affect wages (and not downwards). Both these effects are illustrated as flat curves in .

Finally, explores the demographic composition of school employees. Note that these outcomes can be affected both when new employees are hired and when existing ones leave. Models 11 and 12 explores the ratio of women. Schools are already female-dominated workplaces and this tendency appear to increase when managers gain more autonomy. The graphical illustration indicates that the proportion of women in general is increasing, and more so in schools where managerial autonomy is increasing.

Turning to age, the models show no significant effects for the average age of employees, however, in model 15 and 16 it is indicated that the age spread narrows when managerial autonomy increases. This effect appears to be delayed and is only significant in 2010, three years after the reform. Taken together, these results could be interpreted to mean that managers with increased autonomy seek to build more homogenous workplaces with less gender diversity and smaller age spread.

presents graphical depictions of the results. Focus is on the model with the before/after indicator for time. The graphs show the marginal effect of this variable for different values of the change index. That is, the Y-axis indicates the predicted change caused by changes in autonomy.

As noted above, we re-ran some of the models using alternative specifications (results not reported – available from authors). As the number of employees and part-timers are count variables, we used a Poisson model as an alternative specification. All results remain substantively similar with slightly lower p-values in the Poisson specifications. For the proportion of teachers, turnover, and the proportion women, we used fractional regressions as alternative models. For the teacher ratio and turnover, the results are substantively similar though p-values are slightly larger in the alternative specification. For the ratio of women, the p-value of the DID estimator in model 11 increases to 0.09 and there are similarly increases for the estimators in model 12.

Discussion and conclusion

Exactly how autonomous public managers should be from their political masters is a recurrent question in the public administration literature. Our literature survey shows that findings are typically mixed or inconclusive. We argue that there are substantial as well as methodological reasons for this state of affairs. Substantially, researchers often face the problem that the autonomy-changing reforms they study are implemented in a half-hearted fashion. This leaves open the question of how much change has really occurred. Methodologically, researchers face problems of, first, long causal chains – the fact that the chain from autonomy to performance is long and goes via managerial behavior – and, second, limited variation in management autonomy, the independent variable of interest.

Our study provides improved leverage over these substantial and methodological challenges. We measure changes in managerial autonomy directly at the implementation stage by asking the involved managers how large a change they have experienced in their autonomy in financial and staffing decisions. This reduces the substantial problem of whether reforms have been fully implemented. Methodologically, we avoid the long-causal-chain problem by zooming in on the link between managerial autonomy and managerial behavior. The ultimately interesting dependent variable may be performance, but performance will only be impacted if changes in managerial autonomy have an effect on their behavior. By studying Danish elementary schools during the time of municipal amalgamation reform, we obtain large variation in changes in management autonomy. Danish schools are, of course, not statistically representative of public schools or public organizations globally, but the findings of our study are generalizable in an analytical sense.

Our study shows that public managers do in fact react, when managerial autonomy changes. We studied three areas in which managers may hold varying degrees of autonomy: Recruitment, employment conditions, and organizational demographics. We developed eight indicators of different aspects of these areas where managerial autonomy might make a difference. In five out of these eight cases we identified an effect of changed managerial autonomy.

These findings hold lessons for theoretical debates about managerial autonomy. Opposing views are offered by the new public management movement and the literature on the differences between public and private management. Our findings are difficult to reconcile with the arguments of the latter, which argues that letting managers manage will produce no effects. However, our results show that public managers do, in fact, not shy away from using increased freedom. In other words, as claimed by the new public management movement, it seems to be possible to make managers manage by letting them manage.

However, this does not necessarily mean that the new public management movement is right. A reasonable question is how much support our findings offer to their arguments. Three limitations of our study speak against drawing too firm conclusions here. First, one objection is that our managers may well react to changes in their autonomy, but is the reaction strong enough in a substantial sense to refute the arguments of the literature on the differences between public and private management? This question cannot be finally answered on the basis of our data. It would require data on the problems confronting our managers and evaluation of the magnitude of their reactions in light of the seriousness of the problems. In other words, addressing this type of objection demands a much more detailed study of the individual institutions in which the managers operate.

Second, one might also object that we find areas where managerial autonomy does not seem to make a difference. In particular, we do not find any effects on our two indicators of employment conditions, – turnover and salary. Is this not evidence in favor of the literature on the differences between public and private management? We hesitate to draw this conclusion. The reason is that there are limits to how wide-ranging managerial autonomy in the institutions that we study – Danish public schools – can be in relation to salary and turnover. Even high managerial autonomy can only influence salary levels at the margin, and influencing turnover is demanding since it requires laying off teachers which is a drastic measure in the Danish context. So, while these indicators are, in principle, possible to be affected by autonomous managers, they have a least-likely character. We therefore think that future studies might well develop other indicators of employment conditions before firm conclusions are drawn. We also note that we are only able to use a perceptual measure of managerial autonomy. As such, our conclusions are also limited by an inability to contrast formal and actual autonomy (Ammons & Roenigk, Citation2020).

Finally, our results provide food for thought about the link between managerial autonomy and the ultimately interesting dependent variable, performance. For methodological reasons, we designed our study to focus on the link between managerial autonomy and managerial behavior, not organizational performance. But our results may still be instructive for the relationship between managerial autonomy and performance. Our findings in the area of organizational demographics suggest that autonomous managers in Danish public schools use their freedom to hire more female teachers in the already female-dominated schools, and that they seek to narrow the teachers’ age spread. In other words, they may seek to create more homogeneous workplaces. This may make sense from a local perspective. But it may also have effects on performance. Diversity, based on gender, age or other demographic categories, may have positive as well as negative effects (DiTomaso et al., Citation2007: 488), and empirical studies show that diversity has effects on factors such as engagement, creativity, conflict and absenteeism (Nielsen & Madsen, Citation2017). However, context is important. Evidence from Danish schools suggest that managers are more reluctant to hire teachers with minority background in times of crisis (Guul et al., Citation2019). Coming out of a reform, managers similarly may have preferred a homogenous staff composition. More research is obviously needed here, but our findings may indicate that managers, at least sometimes, use autonomy to respond to local constraints and situational imperatives rather than to increase organizational performance. The new public management movement expects increased managerial freedom to lead to increased efficiency, effectiveness, and innovation. Our study suggests that this need not always be the case (see also Cardenas and Ramirez de la Cruz 2017). Managers may sometimes prefer to use their freedom to address more pressing local concerns that have no effect on performance – e.g. bureaushaping (Dunleavy, Citation1991) – or even negative effects.

final-20240624 appendix_final.docx

Download MS Word (420 KB)Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jens Blom-Hansen

Jens Blom-Hansen is a professor in Political Science at the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University, Denmark. His research interests include municipal politics, central-local government relations, and EU politics. His work has been published by Oxford University Press, American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics, and Journal of European Public Policy.

Søren Serritzlew

Søren Serritzlew is a professor in Political Science at the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University. His research interests currently focus on fiscal federalism, local government, and public policy decision making. His work has been published in journals such as American Political Science Review, American Journal of Political Science, and Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory.

Anders Ryom Villadsen

Anders Ryom Villadsen is a professor in the Department of Management at Aarhus University. His research interests include public management and leadership and employee and team diversity. His work has been published in journals such as Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Public Administration Review, and Academy of Management Discoveries.

References

- Allison, G. T, Second Edition (1987). [1979]. Public and private management: Are they fundamentally alike in all unimportant respects?. Proceedings for the Public Management Research Conference, November 19-20, 1979. Reprinted in Jay M. Shafritz and Albert C. Hyde (eds.). Classics of Public Administration. : Dorsey Press (pp. 510–529).

- Ammons, D. N., & Roenigk, D. J. (2020). Exploring devolved decision authority in Performance management regimes: The relevance of perceived and actual decision authority as elements of performance management success. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(1), 28–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2019.1657918

- Andersen, S. C., D. P. & Moynihan, (2016). Bureaucratic investments in expertise: Evidence from a randomized controlled field trial. The Journal of Politics, 78(4), 1032–1044. https://doi.org/10.1086/686029]

- Andrews, R. (2011). NPM and the search for efficiency. In T. Christensen and P. Lægreid (Eds.), The ashgate research companion to new public management (pp. 281–294). Ashgate.

- Andrews, R., Boyne, G. A., & Walker, R. M. (2011). Dimensions of publicness and organizational performance: A review of the evidence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(Supplement 3), i301–i319. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur026

- Aucoin, P. (2011). The political-administrative design of NPM. In T. Christensen and P. Lægreid (Eds.), The ashgate research companion to new public management (pp. 33–46). Ashgate.

- Bhatti, Y., & Hansen, K. M. (2011). “Who marries whom? The influence of societal connectedness, economic and political homogeneity, and population size on jurisdictional consolidations. European Journal of Political Research, 50(2), 212–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01928.x

- Bjørnholt, B., Boye, S., & Falk Mikkelsen, M. (2022). Balancing managerialism and autonomy: A panel study of the link between managerial autonomy, performance goals, and organizational performance. Public Performance & Management Review, 45(6), 1258–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2022.2048399

- Bjørnholt, B., Boye, S., & Hansen, N. W. (2022). The influence of regulative contents, stakeholders, and formalization on managerial autonomy perceived at the front line. Public Management Review, 24(10), 1569–1590. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1912818

- Blom-Hansen, J., Houlberg, K., & Serritzlew, S. (2014). Size, democracy, and the economic costs of running the political system. American Journal of Political Science, 58(4), 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12096

- Blotenberg, I., Schang, L., & Boywitt, D. (2022). Should indicators be correlated? Formative indicators for healthcare quality measurement. BMJ Open Quality, 11(2), e001791. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2021-001791

- Boadway, R., & Shah, A. (2009). Fiscal federalism. Cambridge University Press.

- Boon, J., & Wynen, J. (2017). On the bureaucracy of bureaucracies: Analysing the size and organization of overhead in public organizations. Public Administration, 95(1), 214–231.

- Boyne, G. A. (2002). Public and private management: What’s the difference? Journal of Management Studies, 39(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00284

- Boyne, G. A. (2003). Sources of public service improvement: A critical review and research agenda. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 13(3), 367–394. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mug027

- Bryson, J. M., Berry, F. S., & Yang, K. (2010). The state of public strategic management research: A selective literature review and set of future directions. The American Review of Public Administration, 40(5), 495–521. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074010370361

- Cárdenas, S. E. E., & Ramírez de la Cruz, (2017). Controlling administrative discretion promotes social equity? Evidence from a natural experiment. Public Administration Review, 77(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12590

- Coggburn, J. D. (2000). The effects of deregulation on state government personnel administration. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 20(4), 24–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X0002000404

- Dan, S., & Pollitt, C. (2015). NPM can work: An optimistic review of the impact of new public management reforms in central and eastern Europe. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1305–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.908662

- DiTomaso, N., Post, C., & Parks-Yancy, R. (2007). Workforce diversity and inequality: Power, status, and numbers. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1), 473–501. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131805

- Dunleavy, P. (1991). Democracy, bureaucracy, and public choice. Economic explanations in political science. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- George, B., Van de Walle, S., & Hammerschmid, G. (2019). Institutions or contingencies? A cross country analysis of management tool use by public sector executives. Public Administration Review, 79(3), 330–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13018

- George, B., Walker, R. M., & Monster, J. (2019). Does strategic planning improve organizational performance? A meta–analysis. Public Administration Review, 79(6), 810–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13104

- Gerrish, E. (2016). The impact of performance management on performance in public organizations: A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review, 76(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12433

- Goodnow, F. J. (1900). Politics and administration. A study in government. Macmillan.

- Gulick, L. (1937). Notes on the theory of organization. In L. Gulick and L. Urwick (Eds.), Papers on the science of administration (pp. 1–46). Institute of Public Administration.

- Guul, T. S., Villadsen, A. R., & Wulff, J. N. (2019). Does good performance reduce bad behavior? Antecedents of ethnic employment discrimination in public organizations. Public Administration Review, 79(5), 666–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13094

- Hammerschmid, G., Van de Walle, S., Andrews, R., & Mostafa, A. M. S. (2019). New public management reforms in Europe and their effects: Findings from a 20-country top executive survey. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 85(3), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852317751632

- Heinrich, C. J. (2012). Measuring public sector performance and effectiveness. In B. Guy Peters and Jon Pierre (Eds.), The Sage handbook of public administration (pp. 32–50). Sage.

- Hood, C. (1991). A public management for all seasons? Public Administration, 69(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x

- Huber, J. D., & Shipan, C. R. (2002). Deliberate discretion? The institutional foundations of bureaucratic autonomy. Cambridge University Press.

- Knott, J. H., & Miller, G. J. (1987). Reforming bureaucracy. The politics of institutional choice. Prentice-Hall.

- Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting interorganizational research using key informants. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1633–1651. https://doi.org/10.2307/256824

- Langbein, L. I. (2000). Ownership, empowerment, and productivity: Some empirical evidence on the causes and consequences of employee discretion. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 19(3), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6688(200022)19:3<427::AID-PAM4>3.0.CO;2-2

- Meier, K. J., & O’Toole, L. J.Jr,. (2008). The proverbs of new public management: Lessons form an evidence-based research agenda. The American Review of Public Administration, 39(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008326312

- Miller, G. J. (1992). Managerial dilemmas: The political economy of hierarchy. Cambridge University Press.

- Mouritzen, P. E. (2010). The Danish revolution in local government: How and why?. In H. Baldersheim and L. E. Rose (Eds.), Territorial choice. The politics of boundaries and borders (pp. 21–41). Palgrave.

- Mouritzen, Poul Erik (Ed.) (2006). Stort er godt. Otte fortællinger om tilblivelsen af de nye kommuner. Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

- Moynihan, D. P. (2006). Managing for results in state government: Evaluating a decade of reform. Public Administration Review, 66(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00557.x

- Nielsen, V. L., M. B. & Madsen, (2017). Does gender diversity in the workplace affect job satisfaction and turnover intentions? International Public Management Review, 18(1), 77–113.

- OECD. (2011). OECD reviews of evaluation and assessment in education. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2013). Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing.

- Osborne, D., & Gaebler, T. (1992). Reinventing government. How the entrepreneurial spirit is transforming the public sector. Addison-Wesley.

- Overman, S., & Van Thiel, S. (2016). Agencification and public sector performance: A systematic comparison in 20 countries. Public Management Review, 18(4), 611–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2015.1028973

- Parker, R. S., & Subramaniam, V. (1964). ‘Public’ and ‘Private’ Administration. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 30(4), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/002085236403000403

- Poister, T. H., Pitts, D. W., & Edwards, L. H. (2010). Strategic management research in the public sector: A review, synthesis, and future directions. The American Review of Public Administration, 40(5), 522–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074010370617

- Pollitt, C. (1998). Managerialism revisited. In B. Guy Peters and Donald J. Savoie (Eds.), Taking stock: Assessing public sector reforms (pp. 45–77). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Pollitt, C., & Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Pollitt, C., & Dan, S. (2013). Searching for impacts in performance-oriented management reform: A review of the European literature. Public Performance & Management Review, 37(1), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576370101

- Rainey, H. G., Backoff, R. W., & Levine, C. H. (1976). Comparing public and private organizations. Public Administration Review, 36(2), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.2307/975145

- Sayre, W. S., Parkinson, C. N., Argyris, C., & Whyte, W. H. (1958). The unhappy bureaucrats: Views ironic, hopeful, indignant. Public Administration Review, 18(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/10.2307/973438

- Timmermans, B. (2010). The Danish integrated database for labor market research: Towards demystification for the English speaking audience. DRUID Working Paper, 10–16.

- Verhoest, K., Peters, B. G., Bouckaert, G., & Verschuere, B. (2004). The study of organisational autonomy: A conceptual review. Public Administration and Development, 24(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.316

- Villadsen, A. R., & Wulff, J. N. (2021). Are you 110% sure? modeling of fractions and proportions in strategy and management research. Strategic Organization, 19(2), 312–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127019854966

- Vogel, R., & Werkmeister, L. (2020). What is public about public leadership? Exploring implicit public leadership theories. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 31(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa024

- Walker, R. M., & Andrews, R. (2015). Local government management and performance: A review of evidence. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(1), 101–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mut038

- Wang, W., & Yeung, R. (2019). Testing the effectiveness of “managing for results”: Evidence from an education policy innovation in New York City. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 29(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muy043

- Weber, M. (1970). [1922]) Bureaucracy. In H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (Eds.), From Max weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 196–244). Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Wilson, J. Q. (1989). Bureaucracy. What government agencies do and why they do it. Basic Books.

- Wynen, J., & Verhoest, K. (2016). Internal performance-based steering in public sector organizations: Examining the effect of organizational autonomy and external result control. Public Performance & Management Review, 39(3), 535–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/15309576.2015.1137769

- Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research. design and methods. Sage.