Abstract

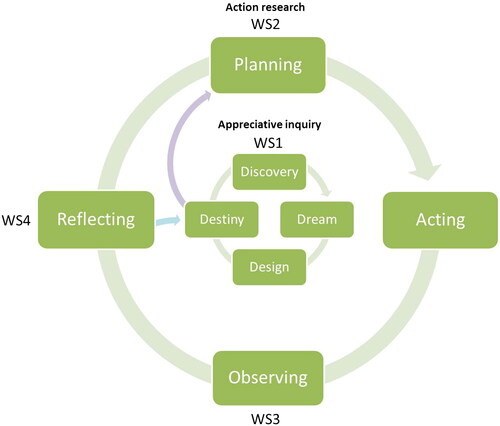

During a project focusing on household waste a collaborative approach was deemed necessary. Researchers and stakeholders went through a series of workshops starting and ending with an appreciative inquiry which directed the ongoing action research process. This article discusses this process and presents a model for this methodology. Envisioning the results from the outset aided the collaborators’ action. Further, the workshop series formed a collaborative forum in which to discuss progress and issues that occurred during the process. Appreciative inquiry aided the collaborators and provided a starting and end point for the action research process.

Introduction

Environmental challenges cross sectoral boundaries and involve a multitude of stakeholders. Collaborative approaches have been suggested as the means to solve such complex issues (Cornell et al., Citation2013; Gray & Stites, Citation2013). In science and technology studies there is a recognized trend towards more stakeholder involvement where knowledge is coproduced close to those who would benefit from it. A number of different theoretical frameworks have been presented with the common basis of collaboration between researchers and stakeholders. For example, this form of knowledge production embedded in society has been discussed in terms of a Mode 2 of science where knowledge is produced in teams for use in practice (Gibbons, Citation1994). In later years the idea of a Mode 3 has been emphasized where this embeddedness is extended, involving participants in a democratic dialog throughout the research process (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2014). Further, this dialog might even be necessary due to the current environmental challenges that are pressing and common to all members of society (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2011).

Different sectors have different ways of working, as well as different organizational values and goals (Adler, Elmquist, & Norrgren, Citation2009; Ruuska & Teigland, Citation2009). The challenges of collaboration between researchers and other sectors have been the target of previous research. Some form of participative decision-making has been shown to make collaboration run more smoothly (Bozeman, Gaughan, Youtie, Slade, & Rimes, Citation2016; Freitas, Geuna, & Rossi, Citation2013), but the actual workings of micro-level collaboration, where individuals from different sectors interact with each other, still need further research (Bjerregaard, Citation2009; Bozeman, Fay, & Slade, Citation2013; Freitas et al., Citation2013). Participatory forms of knowledge creation have been acknowledged as a way to manage collaborative processes (Shirk et al., Citation2012) and participation, reflection, and action have also been acknowledged as important in environmental education to develop action competence (Varela-Losada, Vega-Marcote, Pérez-Rodríguez, & Álvarez-Lires, Citation2016).

This article proposes a methodology where action research is combined with appreciative inquiry to include participants in an environmental research process. Here, appreciative inquiry serves as a framework for the action research process (Stowell, Citation2013). In appreciative inquiry the idea is to start from what is working well, and why, and then move towards a possible ideal situation and possibilities for implementing positive change (Cooperrider, Whitney, & Stavros, Citation2008; Cooperrider & Srivastva, Citation1987; Cooperrider & Whitney, Citation2001). This is done in four phases, starting with the discovery phase where the participants imagine and discuss what is currently working well and why. The point is to start from the current situation and focus on the positives. In the following dream phase the participants look ahead and discuss the best possible situation and what is different from the current situation. In the design phase possible practical solutions are discussed. Lastly, in the destiny phase, participants plan the next steps towards the practical solutions.

The combination of action research and appreciative inquiry formed the methodology for a collaborative dialog between sectors in the present study. The aim of this article is to evaluate this process, providing a description of the methodology and the lessons learned from a case study aiming at increased waste sorting.

Household waste as a collaborative challenge

This article is the result of a collaborative project that addressed conditions for waste management in a dense city center. Researchers and stakeholders collaborated throughout a year-long process based in the dense city center of Kalmar, a city in southeast Sweden with 40,000 inhabitants.

In a precursor project, we found that major challenges for waste sorting among households included lack of space in the waste collection rooms, narrow cobblestone streets and dense traffic that making waste management difficult (Smith, Citation2016). Previous literature also points to several challenges with regard to waste management in dense city centers: The importance of property owners serving as a link between the tenants and the waste collection system and the importance of information and knowledge about the effects of sorting (Avfall Sverige, Citation2017; Ordoñez, Harder, Nikitas, & Rahe, Citation2015). Further, being able to sort waste fractions close to home has also been shown to improve sorting rates (Rousta, Bolton, Lundin, & Dahlén, Citation2015). Most people visit recycling stations by car and combine this visit with other activities. Three quarters visit recycling stations twice a month (Petersen & Berg, Citation2004). Waste sorting behavior has also been shown to be influenced by the distance between property and collection system, type of collected material, residential structure and alternative places for discharge (Dahlén & Lagerkvist, Citation2010).

Another key finding from the precursor project was that the university, as a neutral partner, could facilitate change and collaboration between different sectors (Bergbäck, Sörme, & Bayard, Citation2016; Rosenlund, Citation2017). This article concerns the continuation of the project, with the aim of gathering the local stakeholders in further collaboration with the focus on the challenge of waste management.

The aims of the new project were to 1) gain knowledge about the conditions for collaboration between property owners, waste management organizations and the municipality to find solutions to manage waste fractions and 2) identify, introduce and evaluate solutions that could improve sorting. This article will focus on the first aim by answering the following research question: How can cross-sector collaboration help improve waste sorting?

Methodology

Research on household waste has previously used action research to measure and create change (Fahy & Davies, Citation2007) and this has previously been shown to facilitate change when approaching general environmental issues (Bradbury, Citation2001; Wittmayer & Schäpke, Citation2014). An action research strategy focuses on closing the gap between research and practice, in other words, finding ways for research to contribute to development and change. Action research solves this by means of a democratic dialog between researchers and participants from other sectors and includes these throughout the research process to identify and solve issues. In such a process the participants become co-producers of knowledge (Wigblad & Jonsson, Citation2008). The action research process involves the steps of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting. While an action research process is supportive for the purpose of including stakeholders in the research process, stakeholders want to see solutions and possible futures.

The authors of this article took the roles of action researchers, engaging in the collaborative process, and conducting research at the same time (Greenwood & Levin, Citation2007; Reason & Bradbury, Citation2006). Other stakeholders involved in the project are shown in . The inner circle formed the project group who participated to a larger extent in the workshop cycle.

The overall collaborative approach was to start out from the four phases of appreciative inquiry and then enter the action research phase. Appreciative inquiry benefits from having an extended story about the context from the outset (Bushe & Paranjpey, Citation2015), and in our case this was fulfilled by previous research and dialog within the project group. It was also this story that guided the action research process. The researchers used this story about the current issues the city center faced.

As a project group we went through a series of workshops representing the phases of appreciative inquiry and further to the action research process. Workshops have previously been shown to be a successful format for creating collaborative spaces and crossing boundaries between sectors (Rosenlund & Rosell, Citation2017). Here, the project process could be discussed and if there was a need for certain a competence this space could be used to help each other out using each sectors expertise. This further connected the research agenda with the stakeholder interests. The starting point of the project, defined at the first workshop, was a shared vision of how to approach the problem. This starting point led to collaborative action towards the identified vision (Greenwood & Levin, Citation2007, p. 147).

The data consisted of documentation from these workshops and the correspondence in between. These included minutes, observation notes, pictures, and emails. The data was captured and analyzed throughout the process and afterwards using a qualitative database. Structural narrative analysis was used to analyze the data (Riessman, Citation2005). This data aimed to capture progress and change in a sequence of events as used in process studies of engaged scholarship (Van de Ven, Citation2007). This is presented as a story of events, a narrative including the main actors and the context (Pentland, Citation1999), mainly structured by the workshops. Progressions of events in this case were parallel: the collaboration, testing the sorting system, and the waste sorting room.

Destiny to action and back again

Below we describe the methodology and methods based on the series of workshops and the steps taken between these. This is the process described in , which provides an overview of these workshops and how these were used to merge appreciative inquiry and action research. It shows how appreciative inquiry served as a starting point (WS1) and end point (WS4) for the action research process. These stages are discussed in the following subsections.

Pre-phase: A story about the context and early reflection

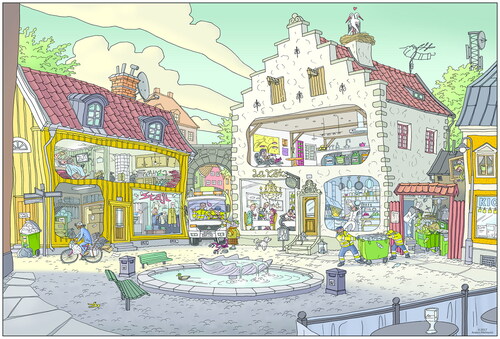

We began the project activities with a pre-meeting with representatives from the waste management association and the property owners’ association. As a project group we also decided to involve students doing their bachelor theses. Further, we saw the importance of including the city center association. The project group further narrowed this down to focus on three challenges: behavioral aspects, the complexity due to the large number of actors involved and the lack of space. We then felt we had a typical case to present and decided to hire an illustrator to present this in an illustration (). Time was one restriction as we had to test this during the spring and thus we could not implement large scale changes.

Appreciative inquiry (workshop 1)

During the first workshop with the project group the goal was to identify solutions that could be tried during the spring. The group included representatives from waste management, property owners, the property owners’ association, the city center association, the municipality and the project group. Following the appreciative inquiry model (), we then formed two groups in which the researchers also participated.

Table 1. Phases of appreciative inquiry.

In the design phase we as researchers presented the groups with an illustration of the city center (). This picture presented many of the previously identified challenges and provided the participants with an object to discuss solutions. Using post-it notes we discussed and wrote down several creative ideas, where the project group finally agreed on two solutions that the group believed were feasible: Colored bags and a shared waste room (a space for sorting shared among several apartments).

In the destiny phase the project group further discussed how the two ideas selected could be introduced and evaluated during the project period. For example, the system with different colored bags for different waste fractions has been introduced in other cities in Sweden (Andersson, Sundqvist, Hultén, & Sandkvist, Citation2018). In Kalmar, green bags are already used for food waste, so the inhabitants are used to the concept. Secondly, the project group discussed the conditions that had to be met for us to have a new type of room or building for waste sorting designed and built.

Action research process (workshop 2–4)

Planning phase (WS 2)

The second workshop was a continuation of the destiny phase where the project group focused on facilitating action on the two identified ways forward. That ended the last phase of the appreciative inquiry approach, and the consensus on destiny served as a guideline for the continued action research cycle of planning, acting, observing and reflecting.

During the planning phase in action research it is important to divide the labor and how things will be done. During workshop 2 we presented the two ideas, together with a preliminary schedule for the project. The project group recognized that the waste room needed more funding than was available in the project but we decided nonetheless to contact a firm of architects and two building design students to develop a concept. The discussion was then focused on the practicalities of testing the colored bags and on communication strategies towards residents that should be invited to participate in that test. The project group settled on two properties comprising a total of 38 apartments that had in common a lack of space for full sorting of recyclable packaging in their waste rooms.

Acting phase (between WS 2 and WS 3)

The acting phase in action research is where plan meets reality and adjustments need to be made accordingly. The week after workshop 2 we as researchers set up two mailboxes with the university logo and delivered information about the project and surveys directly to the residents’ mailboxes. This was to see if there was any interest in taking part in the test. During 1 month prior to the distribution of the colored bags, the waste from the selected properties was weighed to provide pretest data for comparison. After this month, two of the researchers went to the apartments and knocked on doors. We engaged in a dialog with the residents, provided information about the project and delivered Colored bags and baskets (). The package delivered also included a first survey with questions about how the residents perceived their current waste management system. Overall the response was positive, and while a few residents were rather more reluctant to use the system, they agreed to give it a try.

Observation phase (WS 3)

The observation phase of action research is intended for compilation and discussion of early results and data, providing an opportunity to adapt the work and strategies. At this third workshop the project group discussed the process and possible risks of the study. For example, there was the possibility that the residents would throw away everything they already had at home early on. The project group agreed that the waste management association and the property owners should keep a check on the volumes thrown away. At this point the waste management association also emphasized that the project would provide valuable input for the development of the waste management system, partly due to the ongoing process where the government had suggested a transition to a collection of packaging waste close to households.

Reflection phase (WS 4)

Workshop 4 was held after the 4-week trial with colored bags had been completed, and all the weight data had been compiled. In addition, one researcher had interviewed the residents for their perception of the system. The workshop itself focused on presenting results from the project, including the surveys and measuring of waste, as well as the results from the building design students’ waste room concept. By doing this the project group returned to the destiny phase. By evaluating the process the group closed the loop between action research and appreciative inquiry

In this reflection phase of action research, the aim was to discuss changes, results, and other observations from previous phases. Here the project group also looked into the future and ways to see further change. The group agreed that through the process we had reached results that were relevant to their own organizations and the group wished for continuation of the project.

Results and discussion

As we had already identified the issues presented in the illustration (), the discovery phase started out with what was working well. In the dream phase, the project group discussed the future possibilities and where we want to be. Connecting the dream to reality in the design phase, the group settled on two possible solutions that we tried out. In the destiny phase the group took the necessary steps to approach these solutions, and this was the starting point for the action research process.

What followed during the process was a continuous evaluation of the solutions by means of a collaborative approach. No one actor had the necessary knowledge and access to get closer to these solutions; rather, this possibility emerged from the collaboration. The waste management association needed to coordinate the space and logistics with the property owners. The researchers gained access to the waste and to the residents. The architect and the building design students connected with the waste management company to get their numbers right on the blueprints, and so forth.

During the workshop cycle, the group experienced the collaboration as informal, and felt they could contact each other without any problem. This was shown in particular during the last phase of the action research process, when the group connected with the destiny phase once again in workshop 4. This workshop ended with a reflection on the project and the resulting collaboration, as shown by a quote from a representative from the waste management association:

The interdisciplinary approach was important. There were many competences making it easier to solve a problem. It was also a common problem for everyone; a problem for waste management, property owners and the municipality. A common problem where we need a common goal.

This was further emphasized by the architect:

My role is to gather competences. It’s exciting to feel the competence in this room. You get answers, and one plus one becomes three. We meet and respect each other’s knowledge and competence in a process where we don’t know where we will end up […] Everyone owns the process and there are no threats. Without the prestige, you get results

The collaborative approach was important for the project as it gave access to possibilities the stakeholders lacked alone. It also created space where collaboration was made possible between the participating organizations. This space was manifested by the series of workshops. The common dialog during and between these workshops filled in gaps in knowledge for each stakeholder. These were directed by the destiny phase where the group defined the common goal for the project, which we reached collaboratively.

Appreciative inquiry was shown to form a good starting point and end point, serving as a framework for the action research process. In the literature on collaboration this is referred to as a problem-setting phase, after which the stakeholders can commit to the process (Gray, Citation1989). For our research, the phases of appreciative inquiry provided a direction for the collaboration and the action research process.

In a comparison between appreciative inquiry and action research, the former may be more opportunity-centered instead of focusing on problems. It might also be more suitable when envisioning a future to direct the collaborative action (Boyd & Bright, Citation2007). This possible future was envisioned collaboratively within the constraints of a 1-year project. It formed a clear picture of where we wanted to be after the project, and following the workshops we evaluated and adjusted during the process.

Appreciative inquiry recognizes that action research might risk becoming trapped in loops, returning to the original problem without directions for change (Cooperrider & Srivastva, Citation1987). As collaborations in projects are temporary, we could not afford to be stuck in a problem formulation phase. Further, action research might leave the organizational culture intact (Bushe, Citation2007). This might be less problematic in temporary projects as the goal is to temporarily engage different stakeholders and overcome differences.

On the other hand, appreciative inquiry on its own might leave too little room for critical evaluation of the process (Grant & Humphries, Citation2006), something that the action researcher reflects upon constantly. It was also the action research process that provided the research results. In the process, appreciative inquiry took less space chronologically but it set an important direction for the action research process. Situating the solutions at the core of the process and returning to these in the reflection phase provided a beginning and an end for the action research.

Conclusions

As more environmental issues become pressing challenges for society, waste management being one, there is a need for a methodology to solve these. This article concerns a research process typical of a Mode 3 of science or quadruple helix (Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, Citation2014; Miller, McAdam, & McAdam, Citation2016), recognizing the democratization of the research process as an important part of contemporary knowledge production. In practice, this means that researchers alone cannot solve certain issues without the inclusion of larger society, in this article represented by several stakeholders and citizens.

The use of appreciative inquiry helped the researchers and participants to start from solutions to an issue. It enhanced the action research process which helped to structure the actual testing in this case. This aided us in moving the process forward, and not becoming stuck in a problem formulation phase. It also served a function by facilitating the collaborative process, where we got to know each other and dropped our prestige. Other important lessons for future appreciative inquiries include the importance of an established network and to take the planning in the destiny phase seriously.

This process also led to more knowledge about waste sorting. The introduction of colored bags decreased residual waste by 15% and increased sorted food waste by 33%. Further, two thirds of participants were satisfied with the proposed system (Sörme et al., forthcoming). These results show that we reached the outset goals by means of collaboration, in other words reaching the destiny phase. Future research processes where problems need to be addressed collaboratively can learn from the experiences presented in this article. The method described can be used in similar processes with a multitude of stakeholders who need to work towards a common vision.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all participants and residents for their commitment. Our thanks also go to Lars Lindkvist for reading the draft of this article.

References

- Adler, N. , Elmquist, M. , & Norrgren, F . (2009). The challenge of managing boundary-spanning research activities: Experiences from the Swedish context. Research Policy , 38 (7), 1136–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2009.05.001

- Andersson, T. , Sundqvist, J. O. , Hultén, J. , & Sandkvist, F . (2018). Ekonomisk Jämförelse av Två System För Fastighetsnära Insamling av Avfall. Stockholm: IVL.

- Avfall Sverige (2017). Beteendeförändring i Mångfaldsområden . Malmö: Avfall Sverige.

- Bergbäck, B. , Sörme, L. , & Bayard, A.-C . (2016). Samhällets restprodukter-framtidens resurser . Kalmar, Sweden: Linnaeus University.

- Bjerregaard, T . (2009). Universities-industry collaboration strategies: A micro-level perspective. European Journal of Innovation Management , 12 (2), 161–176. doi: 10.1108/14601060910953951

- Boyd, N. M. , & Bright, D. S . (2007). Appreciative inquiry as a mode of action research for community psychology. Journal of Community Psychology , 35 (8), 1019–1036. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20208

- Bozeman, B. , Fay, D. , & Slade, C. P . (2013). Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: The-state-of-the-art. The Journal of Technology Transfer , 38 (1), 1–67. doi: 10.1007/s10961-012-9281-8

- Bozeman, B. , Gaughan, M. , Youtie, J. , Slade, C. P. , & Rimes, H . (2016). Research collaboration experiences, good and bad: Dispatches from the front lines. Science and Public Policy , 43 (2), 226–244. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scv035

- Bradbury, H . (2001). Learning with the natural step: Action research to promote conversations for sustainable development. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The handbook of action research (pp. 236–242). London: Sage.

- Bushe, G . (2007). Appreciative inquiry is not about the positive. OD Practitioner , 39 (4), 33–38.

- Bushe, G. R. , & Paranjpey, N . (2015). Comparing the generativity of problem solving and appreciative inquiry: A field experiment. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science , 51 (3), 309–335. doi: 10.1177/0021886314562001

- Carayannis, E. G. , & Campbell, D. F . (2014). Developed democracies versus emerging autocracies: Arts, democracy, and innovation in quadruple helix innovation systems. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship , 3 (1), 1–23.

- Carayannis, E. G. , & Campbell, D. F. J . (2011). Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems. In S. I. Business (Ed.), Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems (Vol. 7). New York, NY: Springer.

- Carayannis, E. G. , & Rakhmatullin, R . (2014). The quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. Journal of the Knowledge Economy , 5 (2), 212–239. doi: 10.1007/s13132-014-0185-8

- Cooperrider, D. , Whitney, D. D. , & Stavros, J. M . (2008). The appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change . Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

- Cooperrider, D. L. , & Srivastva, S . (1987). Appreciative inquiry in organizational life. Research in Organizational Change and Development , 1 (1), 129–169.

- Cooperrider, D. L. , & Whitney, D . (2001). A positive revolution in change: Appreciative inquiry. Public Administration and Public Policy , 87 , 611–630.

- Cornell, S. , Berkhout, F. , Tuinstra, W. , Tàbara, J. D. , Jäger, J. , Chabay, I. , … van Kerkhoff, L . (2013). Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environmental Science & Policy , 28 , 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.008

- Dahlén, L. , & Lagerkvist, A . (2010). Evaluation of recycling programmes in household waste collection systems. Waste Management & Research , 28 (7), 577–586. doi: 10.1177/0734242X09341193

- Fahy, F. , & Davies, A . (2007). Home improvements: Household waste minimisation and action research. Resources, Conservation and Recycling , 52 (1), 13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2007.01.006

- Freitas, I. M. B. , Geuna, A. , & Rossi, F . (2013). Finding the right partners: Institutional and personal modes of governance of university-industry interactions. Research Policy , 42 (1), 50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2012.06.007

- Gibbons, M . (1994). The new production of knowledge: The dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies. London: Sage.

- Grant, S. , & Humphries, M . (2006). Critical evaluation of appreciative inquiry: Bridging an apparent paradox. Action Research , 4 (4), 401–418. doi: 10.1177/1476750306070103

- Gray, B . (1989). Collaborating: Finding common ground for multiparty problems. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Gray, B. , & Stites, J. P . (2013). Sustainability through partnerships . London, Ontario: Network for Business Sustainability.

- Greenwood, D. J. , & Levin, M . (2007). Introduction to action research. London: Sage.

- Miller, K. , McAdam, R. , & McAdam, M . (2016). A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: Toward a research agenda. R&D Management , 48 (1), 7–24.

- Ordoñez, I. , Harder, R. , Nikitas, A. , & Rahe, U . (2015). Waste sorting in apartments: Integrating the perspective of the user. Journal of Cleaner Production , 106 , 669–679. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.09.100

- Pentland, B. T . (1999). Building process theory with narrative: From description to explanation. Academy of Management Review , 24 (4), 711–724. doi: 10.5465/amr.1999.2553249

- Petersen, C. H. M. , & Berg, P. E . (2004). Use of recycling stations in Borlänge, Sweden–volume weights and attitudes. Waste Management , 24 (9), 911–918. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2004.04.002

- Reason, P. , & Bradbury, H . (Eds.). (2006). The handbook of action research . London: Sage.

- Riessman, C. K . (2005). Narrative analysis narrative, memory & everyday life (pp. 1–7). Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield.

- Rosenlund, J . (2017). Improving regional waste management using the circular economy as an epistemic object. Environmental Sociology , 3 (3), 297–307. doi: 10.1080/23251042.2017.1323154

- Rosenlund, J. , & Rosell, E . (2017). Using dialogue arenas to manage boundaries between sectors and disciplines in environmental research projects. International Journal of Action Research , 13 (1), 24–38. doi: 10.3224/ijar.v13i1.03

- Rousta, K. , Bolton, K. , Lundin, M. , & Dahlén, L . (2015). Quantitative assessment of distance to collection point and improved sorting information on source separation of household waste. Waste Management , 40 , 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.03.005

- Ruuska, I. , & Teigland, R . (2009). Ensuring project success through collective competence and creative conflict in public–private partnerships – A case study of Bygga Villa, a Swedish triple helix e-government initiative. International Journal of Project Management , 27 (4), 323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.02.007

- Shirk, J. L. , Ballard, H. L. , Wilderman, C. C. , Phillips, T. , Wiggins, A. , Jordan, R. , … Krasny, M. E . (2012). Public participation in scientific research: A framework for deliberate design. Ecology and Society , 17 (2), 29–48.

- Smith, E . (2016). Avfallshantering i trånga stadsutrymmen . Kalmar, Sweden: Exemplet Kvarnholmen.

- Stowell, F . (2013). The appreciative inquiry method-A suitable candidate for action research? Systems Research and Behavioral Science , 30 (1), 15–30. doi: 10.1002/sres.2117

- Van de Ven, A. H . (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Varela-Losada, M. , Vega-Marcote, P. , Pérez-Rodríguez, U. , & Álvarez-Lires, M . (2016). Going to action? A literature review on educational proposals in formal environmental education. Environmental Education Research , 22 (3), 390–421. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1101751

- Wigblad, R. , & Jonsson, S . (2008). "Praktikdriven teori" - mot en ny interaktiv forskningsstrategi. In B. Johannisson , E. Gunnarsson , & T. Stjernberg (Eds.), Gemensamt kunskapande - den interaktiva forskningens praktik. Växjö, Sweden: Växjö University Press.

- Wittmayer, J. M. , & Schäpke, N . (2014). Action, research and participation: roles of researchers in sustainability transitions. Sustainability Science , 9 (4), 483–496. doi: 10.1007/s11625-014-0258-4