Abstract

The project k.i.d.Z.21-Austria is aimed at raising climate change literacy among teenagers. As the participating teenagers had different weaknesses regarding climate change literacy before the project, the project evaluation places emphasis on how the project manages to compensate for these conditions by focusing on the specific weaknesses. Therefore, the preconditions were detected by means of a pre-survey (N = 392). Based thereon, a t-test for paired samples tested the teenagers’ development within the project. The results show that the weaknesses were mostly addressed and that focusing on a target group and weakness specification in evaluating environmental education can be beneficial.

Introduction

Climate change is one of the main global environmental challenges facing society (Steffen et al., Citation2015). If society hopes to address this, a profound shift in the values and ways of thinking is required (Gifford, Citation2013; UNESCO, Citation2014) among governments as well as individuals (Moser & Dilling, Citation2011). Being aware of this, many educational programs are aimed at raising individuals’ climate change literacy (Ojala, Citation2015; UNESCO, Citation2015). Thereby teenagers are one of the most important target groups (Moser, Citation2016), as the generation whose lives will be affected by climate change more than any generation before (Corner et al., Citation2015; Ojala, Citation2012) and they will be responsible for dealing with the environmental, economic, and societal consequences of climate change (Corner et al., Citation2015; Ojala & Lakew, Citation2017).

In order to educate young people about climate change and raise their literacy thereof, first it is important to understand their preconditions, as they shape and influence the learning process of an individual (Robottom Citation2004; Krahenbuhl Citation2016). Teenagers start within the climate change education programs with different strengths and weaknesses regarding climate change literacy (Kuthe et al., Accepted). Recent studies show that climate change education has to be adapted with regards to its content, frame and method, to the particular preconditions of the target group (Moser & Dilling, Citation2011; Zaval & Cornwell, Citation2017). This is particularly important, as messages that are not properly framed can be ineffective or even backfire (Lawrence & Estow, Citation2017; Uhl, Jonas, & Klackl, Citation2016). Considering the preconditions in education is also in line the constructivist understanding of a learning process, which assumes that learning usually depends on previous experience and knowledge (Robottom Citation2004, Schuler Citation2010). Nevertheless, to our knowledge, a study trying to identify the teenagers’ preconditions before the program, is still missing. This study identifies various weaknesses of the young people before the project and uses a target group-oriented evaluation to investigate whether these various weaknesses can be compensated in climate change education programs such as k.i.d.Z.21-Austria.

Climate change literacy

The term climate change literacy varies among literature. In our study, climate change literacy comprises the following five aspects:

Attitude: Having a positive attitude towards climate change and towards taking action also influences climate-friendly behavior. A positive attitude comprises, for example, the perception of one’s ability to change one’s behavior (self-efficacy), the willing of someone to change one’s behavior (willingness to act) or the feeling that a change in behavior has a positive impact on the degree of climate change (locus of control) (Ernst, Blood, & Beery, Citation2017; Hines, Hungerford, & Tomera, 1986/Citation1987).

Personal concern: The more the people feel concerned by climate change in their lives the more l ikely they engage in climate-friendly actions (Boyes & Stanisstreet, Citation2012; Metag, Füchslin, & Schafer, Citation2015).

Climate-friendly behavior: Teenagers can change their behavior towards a more climate-friendly manner in their everyday lives and reduce their own carbon footprint (Corner et al., Citation2015; Metag et al., Citation2015).

Multiplicative actions: Additionally, teenagers can be engaged as multipliers for climate change literacy or so-called change agents. They can influence the climate change literacy of their family and friends, when they talk about the project at home or in their free time activities (Hiramatsu, Kurisu, Nakamura, Teraki, & Hanaki, Citation2014).

Knowledge: Knowledge about climate change and its causes and effect is an important basis for all the other components of climate change literacy (Hines et al., Citation1986/1987; Metag et al., Citation2015).

Different preconditions of young people

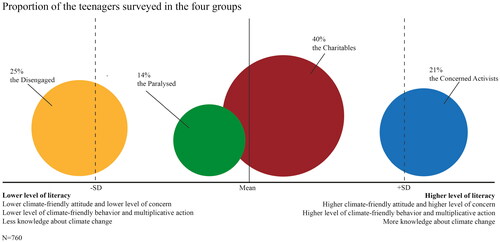

This study is based on a previous study by Kuthe et al. (Accepted). Taking the example of teenagers in Austria and Germany, this previous study has identified four groups that differ in their overall climate change literacy (N = 760) as well as in the five aspects mentioned above (). Therefore a two-step hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted of 760 teenagers participating in k.i.d.Z.21-Austria programs in schools in Austria and Bavaria (Germany) (Kuthe et al., Accepted). For the cluster variables, five factors of climate change literacy were chosen: knowledge, attitude, personal concern, multiplicative actions, and climate-friendly behavior.

The first group is called the disengaged (25%), as its members are not interested in the issue of climate change or in engaging in a societal solution to dealing with it. The second cluster of teenagers forms the paralyzed group (14%), because its members feel concerned by climate change but do not act in a climate-friendly manner. The teenagers of the third group, called the charitables (40%), form the largest group and represent the antipode of the paralyzed, as they do not feel concerned about climate change but demonstrate a high level of climate-friendly behavior. The members of the fourth group, which is called the concerned activists (21%), are the most aware of climate change.

The project “k.i.d.Z.21.-Austria”

Content and core principles

The project” k.i.d.Z.21” started in 2012 with one school in Bavaria and has expanded in recent years. Thus far, over 1,000 young people have taken part in the project in Austria and Bavaria (Germany). The project is aimed at raising climate change literacy among teenagers. The program takes place in phases over the course of one school year. The project starts with a kickoff event at the beginning of the school year. Scientists and other experts are invited to this event and the participants have the first opportunity to deal with the topic. In the next step, the teenagers develop their own small projects in the context of climate change, for example conducting a survey, creating a movie, a song, or an exhibition, or planting a tree in the school garden. Meanwhile, climate change is discussed in regular school lessons across all subjects. At the end of the school year, a one-week excursion is conducted in high mountain regions. In this excursion the teenagers discover and experience climate change at different research stations (for example with the topics of glaciers or tourism).

Each phase of the program incorporates the project’s four core principles. The first principle is the learning approach of moderate constructivism (Bodner, Citation1986). The teenagers’ construction of knowledge, based on their pre-knowledge, interests, and other preconditions, is a central part of the project (Krahenbuhl, Citation2016). Another principle of the project is cooperation between the participating young people and scientists working in the field of climate change (Godemann, Citation2008; McClam & Flores-Scott, Citation2012). As climate change cannot be viewed from just one perspective (UNESCO, Citation2015), the project includes scientific as well as humanistic issues. In order to overcome the temporal and geographical discrepancy of climate change (Myers, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, Akerlof, & Leiserowitz, Citation2013; Wibeck, Citation2014), the young people visit high mountain regions, as these regions are amongst the most vulnerable with regard to climate change (Kohler et al., Citation2010).

k.i.d.Z.21-Austria Addresses the Five Factors of Teenagers’ climate change literacy

The project k.i.d.Z.21-Austria and its different phases addresses all the five factors of teenagers’ climate change literacy. The personal concern of the young people is strengthened, by the interdisciplinary approach of the project, which helps the teenagers to strengthen their understanding of ecological interrelations (McCright, O'Shea, Sweeder, Urquhart, & Zeleke, Citation2013). This understanding can help the teenagers to connect the consequences of climate change to their own life (Myers et al., Citation2013; Shepardson, Niyogi, Roychoudhury, & Hirsch, Citation2012).

The project strengthens various components of the factor “attitude”, such as the internal and external locus of control, interest, and responsibility. The internal and external locus of control is increased as the teenagers develop various opportunities to realize effective action within the project (Stern, Powell, & Hill, Citation2014). The teenagers’ interest in the issue is addressed as they are encouraged to develop and work on their own questions that they are interested in (Krahenbuhl, Citation2016; Tolppanen & Aksela, Citation2018). The issue of responsibility is discussed in various forms and phases in order to sensitize the teenagers to their own responsibility.

The k.i.d.Z.21-Austria project is an integral component of the everyday life in the schools involved. Hence, it stimulates the teenagers to talk about the issue with their families and friends (Williams, McEwen, & Quinn, 2017). This addresses the factor “multiplicative behavior”. Some project events take place in the evening and the teenagers’ parents are also invited (Mead et al., Citation2012). This creates opportunities for the teenagers and their families to talk about the issue of climate change (Grønhøj & Thøgersen, Citation2009). The factor “climate-friendly behavior” is strengthened as the teenagers develop various ideas as to distinct options for action in their everyday life and translate them into action during the project (Ojala, Citation2012). In order to increase their “climate knowledge”, the teenagers analyze and respond to different self-chosen issues and present their results. By working together with scientist and experts, the teenagers can access knowledge regarding the current state of research that is relevant to their future.

Aim of the study

The climate change literacy of teenagers is a crucial determining factor with regard to identifying a societal solution for dealing with climate change. Being aware of this, in recent years great effort has been made to strengthen climate change literacy and its factors in several educational programs. Assuming the aim of climate change education is to strengthen climate change literacy in the long term and on a broad scale, the programs should focus on how to address the weaknesses of the respective target group. However, previous studies lacked an evaluation attempting to identify the weaknesses young people had prior to the project.

With the aim of addressing this lack, our study focuses on the following questions:

What are the specific weaknesses of the four target groups of teenagers?

To what extent does k.i.d.Z.21-Austria manage to address the specific weaknesses of the target groups and compensate for them?

Method

Questionnaire

In order to be able to reveal the difference between the level of the five factors at the beginning and at the end of the project, the study was conducted with a pretest–posttest design. Thus, this study used the pretest data (collected in September 2015 and 2016) also used in the cluster analysis (Kuthe et al., Accepted) and matched these data to the post-test data collected in July 2016 and July 2017. In order to compare the posttest data with the pretest data, we conducted the same questionnaire with the same group of teenagers as in the pretest. In addition to demographic items (age, gender, etc.), the questionnaire includes in particular items (six-level and seven-level, likert scale) that capture the five factors:

Attitude: items such as interest in the topic of climate change, willingness to act, internal and external locus of control, and the felt responsibility to act in a climate-friendly manner were used.

Personal concern: three items were used, covering concern in their own lives, of their family, and of people in Europe;

Climate-friendly behavior: eight items were used, concerning different actions aimed at reducing one’s carbon footprint.

Multiplicative action: was measured by four items asking how often the young people talk with family and friends about climate change and climate-friendly behavior.

Knowledge: four different items that capture the teenagers’ factual knowledge about climate change, its causes and effects were used.

Participants

The sample of this study consists of 392 teenagers between 13 and 16 years of age from 14 different schools at different types of schools (grammar school and lower secondary education) in Germany and Austria; 57% of the respondents are female and 43% are male. In the sample, 48 (12%) of the teenagers belong to the Paralyzed group, 186 (47%) belong to the Charitables, while 71 (22%) belong to the Concerned Activists, and 87 (22%) to the Disengaged.

Data analysis

The data was collected by means of an online questionnaire and analyzed using RStudio 1.1453. All variables included in the analysis are arranged in metric scales. First, a z-transformation was used to make the scales comparable. In order to answer question (1) and identify the specific weaknesses of the target groups, we tested each group separately and compared it to its respective reference group, namely the teenagers belonging to the other three groups. We carried out a two-sided t-test for independent samples. In order to assess the equality of the variance, Levene’s test was applied, and for inhomogeneous variations, a correction in accordance with the t-value according to Welch was carried out (Good, Citation2013). To answer question (2), a two-sided t-test for paired samples was carried out to test the significance of the average improvement for each group (Bors, Citation2017; Eid, Gollwitzer, & Schmitt, Citation2015).

Results

What are the specific weaknesses of the four target groups?

shows the descriptive analysis, means, and standard deviation for each group with regard to the five factors considered in this study. We performed a two-sided t test for independent samples to explore whether the groups have a significantly lower mean score than the respective reference group.

Table 1. Comparison of the results of the pre-survey for the four clusters with regard to the five different aspects of climate change literacy (N = 392).

The results of this t-test indicate that the teenagers belonging to the Disengaged had the lowest score in overall climate change literacy (N Dis=87; z-standardized meanDis=–.49; SDDis=.29) and also lower scores than the reference group (teenagers belonging to the other three groups) with regard to all five factors (). The biggest difference compared to the reference group occurs in the factors personal concern and multiplicative behavior. The paralyzed group is the group that had the second lowest overall climate change literacy (N Par=48; z-standardized meanPar=–.12; SDPar=.27). The members are distinguished for having a lower score than the other teenagers as regards attitude and both behavioral scores: multiplicative behavior and climate-friendly behavior. The charitables formed the biggest group, and they were slightly more aware of climate change than the paralyzed (N Char=186; z-standardized M Char=.05; SDChar=.26). The factor personal concern was the only factor showing a significantly lower score for the members of the Paralyzed group compared to the reference group. The concerned activist group had the highest score in climate change literacy (N CoA=71; z-standardized M CoA=.53; SDCoA=.29). The score of the concerned activists never was significantly lower than the score of the reference group. Consequently, the group of the concerned activists did not have any measurable weaknesses.

Table 2. Overview on the weaknesses of the four groups among the five factors of climate change literacy.

In order to sum up, we can say that the disengaged’s weaknesses exist with regard to all five factors of climate changes literacy, so all five factors should be strengthened. Regarding the paralyzed group, their low level of attitude as well as their low level regarding multiplicative behavior and climate-friendly behavior should be strengthened. The teenagers belonging to the charitables group had only one weakness: they evidence a low level of personal concern. The concerned activists had higher scores than the other teenagers with regard to all factors, so they do not have any particular weakness on average.

Based on our starting point that the project is aimed at addressing the weaknesses of the groups in particular, in the next step we focused only on the disengaged, the paralyzed, and the concerned activists and their respective weaknesses.

To what extent does k.i.d.Z.21-Austria manage to respond to the specific weaknesses of the target groups?

In order to identify which weaknesses were addressed in the project, we compared the mean score of the pretest and the mean score of the posttest using a one-sided t-test for paired samples. In , the results of this t-test are summarized, with the weaknesses that were addressed significantly highlighted in dark green (**p < 0.01; *p < 0.05). The weaknesses that were brought closer to the level of the other teenagers, without the posttest score being significantly higher than the pretest score, are highlighted in light green. As shows, all weaknesses were improved, and even a majority of the weaknesses was improved significantly.

Table 3. Overview of the weaknesses of the four groups with regard to the five factors of climate change literacy and how they were addressed in the k.i.d.Z.21-Austria project.

Regarding the factor of the disengaged, the factor personal concern, the mean score in the posttest was significantly higher than the mean score of the pretest (difmean=.51**). In addition, the score for multiplicative behavior rose significantly, i.e., by difmean=.26**.

After the project, the mean score of the Paralyzed in multiplicative behavior was significantly higher than the mean score before the project, i.e., difmean=.45**. Regarding climate-friendly behavior, their posttest score was also significantly higher than their pretest score (difmean=.40**). The level of attitude rose by difmean=.13, but not significantly.

After the project, the mean level of the group the charitables of personal concern was significantly higher than before the project, i.e., difmean=.156**.

Discussion

The aim of the study was (i) to identify the different weaknesses of the teenagers in climate change education and (ii) to answer the question of whether or not these weaknesses were compensated for in the k.i.d.Z.21-Austria project.

These results show that although the project did not address the groups of young people in a target group-specific manner, as many studies claim is necessary (Kuthe et al., Accepted; Pearce, Brown, Nerlich, & Koteyko, Citation2015; Wibeck, Citation2014; Zaval & Cornwell, Citation2017), the project was partly able to address the weaknesses of the target groups. One explanation for this result might be that the project offers different approaches to deal with the issue of climate change, so every group can find the approach that fits it best. The other reason might be that the project was designed according to the principles of moderate constructivism. This approach makes it possible for the teenagers to align their own learning consistently with their preconditions (Bodner, Citation1986; Krahenbuhl, Citation2016; Sterling, Citation2010).

The study also shows differences in how k.i.d.Z.21-Austria succeeds in addressing the five factors. While the level of the factors personal concern and multiplicative behavior increased significantly in all relevant groups, the scores for climate-friendly behavior increased significantly only for the Paralyzed group. Contrary to our expectations and the results of others studies (Karpudewan, Roth, & Abdullah, Citation2015; Rodriguez et al., Citation2011), which were able to increase the knowledge of the teenagers, it was not possible to significantly increase the score for climate knowledge in the group of the Disengaged in this study. One reason might be the construction of the items capturing the knowledge about climate change and its causes and effects. Perhaps the items were not sufficiently valid or selective to make the change evident. Furthermore, the items used in the survey might not fit the knowledge the teenagers gained within the project, as this knowledge is too specific and varied, while the items cover more basic knowledge.

In addition, it should be noted that the factor attitude was not strengthened in any of the groups. This is in line with recent studies (Duarte, Escario, & Sanagustín, Citation2017; Ernst et al., Citation2017) that show that attitudes result from a complex interplay of many factors and as a result are difficult to change by means of an educational setting. Nevertheless, this is an important finding of the project, which should be reflected in the project development, as attitudes are important influencing factors when it comes to the engagement of teenagers (Levine & Strube, Citation2012; Wolf & Moser, Citation2011)

Our results also indicate a different reaction of the different groups to the same intervention. This becomes especially obvious when analyzing the Disengaged and the Paralyzed. While the climate-friendly behavior score of the Disengaged rose significantly in the course of the project, the score of the Paralyzed also rose, but not significantly. Thus, the results of this research appear to confirm the importance of target group-specific messages, because the different groups’ deficits need different messages in order to reach them in climate change education (Arpan, Opel, & Lu, Citation2013; Moser, Citation2016; Pearce et al., Citation2015; Zaval & Cornwell, Citation2017).

Based on the results of the study, we recommend climate change education programs to evaluate the pre-program conditions of young people, as they influence the learning outcome in the program enormously. Therefore, identifying the preconditions of the young people beforehand can help to be able to build on them during the program. Of course, questionnaires can be used to do this, but even small exercises to assess prior knowledge and attitude or short discussions can help to identify strengths and weaknesses of the group. The results also underline the importance of a moderate constructivist approach, as it highlights the individual preconditions of the learners in the learning process. In addition, as the groups and their development within the project differ, future evaluation studies should consider applying a target group-oriented evaluation, as it could provide useful additional information.

Limitations and future research

As with all research, there are some limitations to the presented study. The first potential limitation of this study concerns the student sample. This study was conducted among teenagers only from Austria and Germany, so these results should be confirmed in future studies with regard to young people from other countries or of different ages. In order to strengthen the validity of the study, a control group would be useful. Furthermore, given that all the data collected by means of the questionnaire are based on the self-assessment of the teenagers, especially regarding the constructs attitude and behavior, distortion has to be considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arpan, L. M. , Opel, A. R. , & Lu, J . (2013). Motivating the skeptical and unconcerned: Considering values, worldviews, and norms when planning messages encouraging energy conservation and efficiency behaviors. Applied Environmental Education & Communication , 12 (3), 207–219. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2013.838875

- Bodner, G. M . (1986). Constructivism: A theory of knowledge. Journal of Chemical Education , 63 (10), 873–878. doi: 10.1021/ed063p873

- Bors, D . (2017). Data analysis for the social sciences: Integrating theory and practice. London: Sage Publishing.

- Boyes, E. , & Stanisstreet, M. (2012). Environmental Education for Behaviour Change: Which actions should be targeted?. International Journal of Science Education , 34 (10), 1591–1614. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2011.584079

- Corner, A. , Roberts, O. , Chiari, S. , Völler, S. , Mayrhuber, E. , Mandl, S. , & Monson, K . (2015). How do young people engage with climate change? The role of knowledge, values, message framing, and trusted communicators. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change , 6 (5), 523–534. doi: 10.1002/wcc.353

- Duarte, R. , Escario, J.-J. , & Sanagustín, M.-V . (2017). The influence of the family, the school, and the group on the environmental attitudes of European students. Environmental Education Research , 23 (1), 23–42. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1074660

- Eid, M. , Gollwitzer, M. , & Schmitt, M . (2015). Statistik und Forschungsmethoden (4., überarb. und erw. Aufl .). Weinheim: Beltz.

- Ernst, J. , Blood, N. , & Beery, T . (2017). Environmental action and student environmental leaders: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, locus of control, and sense of personal responsibility. Environmental Education Research , 23 (2), 149–175. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1068278

- Gifford, R . (2013). Dragons, mules, and honeybees: Barriers, carriers, and unwitting enablers of climate change action. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , 69 (4), 41–48. doi: 10.1177/0096340213493258

- Godemann, J . (2008). Knowledge integration: A key challenge for transdisciplinary cooperation. Environmental Education Research , 14 (6), 625–641. doi: 10.1080/13504620802469188

- Good, P. I . (2013). Introduction to statistics through resampling methods and R (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Grønhøj, A. , & Thøgersen, J . (2009). Like father, like son? Intergenerational transmission of values, attitudes, and behaviours in the environmental domain. Journal of Environmental Psychology , 29 (4), 414–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.05.002

- Hines, J. M ., Hungerford, H. R ., & Tomera, A. N. (1986/1987). Analysis and Synthesis of Research on Responsible Environmental Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Environmental Education , 18 (2), 1–8. doi: 10.1080/00958964.1987.9943482

- Hiramatsu, A. , Kurisu, K. , Nakamura, H. , Teraki, S. , & Hanaki, K . (2014). Spillover effect on families derived from environmental education for children. Low Carbon Economy , 05 (02), 40–50. doi: 10.4236/lce.2014.52005

- Karpudewan, M. , Roth, W.-M. , & Abdullah, M. N. S. B . (2015). Enhancing primary school students’ knowledge about global warming and environmental attitude using climate change activities. International Journal of Science Education , 37 (1), 31–54. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2014.958600

- Kohler, T. , Giger, M. , Hurni, H. , Ott, C. , Wiesmann, U. , Wymann von Dach, S. , & Maselli, D . (2010). Mountains and climate change: A global concern. Mountain Research & Development , 30 (1), 53–55. doi: 10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-09-00086.1

- Krahenbuhl, K. S . (2016). Student-centered education and constructivism: Challenges, concerns, and clarity for teachers. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues & Ideas , 89 (3), 97–105. doi: 10.1080/00098655.2016.1191311

- Kuthe, A. , Keller, L. , Körfgen, A. , Johann, S. , Oberrauch, A. , & Höferl, K.-M . (Accepted). How many young generations are there? A typology of teenagers’ climate change awareness in Germany and Austria. Journal of Environmental Education .

- Lawrence, E. K ., & Estow, S. (2017). Responding to misinformation about climate change. Applied Environmental Education & Communication , 16 (2), 117–128. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2017.1305920

- Levine, D. S. , & Strube, M. J . (2012). Environmental attitudes, knowledge, intentions and behaviors among college students. The Journal of Social Psychology , 152 (3), 308–326. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.604363

- McClam, S. , & Flores-Scott, E. M . (2012). Transdisciplinary teaching and research: What is possible in higher education? Teaching in Higher Education , 17 (3), 231–243. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.611866

- McCright, A. M. , O'Shea, B. W. , Sweeder, R. D. , Urquhart, G. R. , & Zeleke, A . (2013). Promoting interdisciplinarity through climate change education. Nature Climate Change , 3 (8), 713–716. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1844

- Mead, E. , Roser-Renouf, C. , Rimal, R. N. , Flora, J. A. , Maibach, E. W. , & Leiserowitz, A . (2012). Information seeking about global climate change among adolescents: the role of risk perceptions, efficacy beliefs and parental influences. Atlantic Journal of Communication , 20 (1), 31–52. doi: 10.1080/15456870.2012.637027

- Metag, J ., Füchslin, T ., & Schafer, M. (2015). GlobalWarming's Five Germanys: A Typology of Germans' Views on Climate Change Andpatterns of Media Use and Information. doi: 10.1177/0963662515592558

- Moser, S. C . (2016). Reflections on climate change communication research and practice in the second decade of the 21st century: What more is there to say? WIREs Climate Change 7(3), 345–369. doi: 10.1002/wcc.403

- Moser, S. C. , & Dilling, L . (2011). Communicating climate change: Closing the science-action gap. In: J. S. Dryzek , R. Norgaard , & D. Schlosberg (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of climate change and society (pp. 161–174). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Myers, T. A. , Maibach, E. W. , Roser-Renouf, C. , Akerlof, K. , & Leiserowitz, A. A . (2013). The relationship between personal experience and belief in the reality of global warming. Nature Climate Change , 3 (4), 343–347. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1754

- Ojala, M . (2012). How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology , 32 (3), 225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.02.004

- Ojala, M . (2015). Climate change skepticism among adolescents. Journal of Youth Studies , 18 (9), 1135–1153. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1020927

- Ojala, M. , & Lakew, Y . (2017). Young People and climate change communication: Oxford research encyclopedia of climate science . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pearce, W. , Brown, B. , Nerlich, B. , & Koteyko, N . (2015). Communicating climate change: Conduits, content, and consensus. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change , 6 (6), 613–626. doi: 10.1002/wcc.366

- Robottom, I . (2004). Constructivism in environmental education: Beyond conceptual change theory. Australian Journal of Environmental Education , 20 (02), 93–101. doi: 10.1017/S0814062600002238

- Rodriguez, M. , Boyes, E. , Stanisstreet, M. , Skamp, K. R. , Malandrakis, G. , Fortner, R. , … Kim, M . (2011). Can science education help to reduce global warming? an international study of the links between students’ beliefs and their willingness to act. International. Journal of Science in Society , 2 , 89–100. doi: 10.18848/1836-6236/CGP/v02i03/51256

- Schuler, S . (2010). Wie entstehen Schülervorstellungen? Erklärungsansätze und didaktische Konsequenzen am Beispiel des globalen Klimawandels. In S. Reinfried (Ed.), Schülervorstellungen und geographisches Lernen. Aktuelle Conceptual-Change-Forschung und Stand der theoretischen Diskussion (pp. 157–188). Berlin: Logos Verlag.

- Shepardson, D. P. , Niyogi, D. , Roychoudhury, A. , & Hirsch, A . (2012). Conceptualizing climate change in the context of a climate system: Implications for climate and environmental education. Environmental Education Research , 18 (3), 323–352. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2011.622839

- Steffen, W. , Richardson, K. , Rockstrom, J. , Cornell, S. E. , Fetzer, I. , Bennett, E. M. , … Sorlin, S . (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science , 347 (6223), 1259855. doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

- Sterling, S . (2010). Learning for resilience, or the resilient learner? Towards a necessary reconciliation in a paradigm of sustainable education. Environmental Education Research , 16 (5–6), 511–528. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2010.505427

- Stern, M. J. , Powell, R. B. , & Hill, D . (2014). Environmental education program evaluation in the new millennium: What do we measure and what have we learned? Environmental Education Research , 20 (5), 581–611. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2013.838749

- The UNESCO Climate Change Initiative (2010). Climate change education for sustainable development. ED.2010/WS/41, ED.2011/WS/3

- Tolppanen, S. , & Aksela, M . (2018). Identifying and addressing students’ questions on climate change. The Journal of Environmental Education , 47 (2), 1–15.

- Uhl, A ., Jonas, E ., & Kackl, J. (2016). When climatechange information causes undesirable side effects: The influence ofenvironmental self-identity and biospheric values on threat responses / Cuandola información sobre el cambio climático tiene efectos indeseados: lainfluencia de la identidad ambiental y de los valores biosféricos en larespuesta ante una amenaza. Psyecology , 7, 307–334. doi: 0.1080/21711976.2016.1242228

- UNESCO . (2014). Roadmap for implementing the global action programme on education for sustainable development . https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230514

- UNESCO . (2015). Not just hot air: Putting climate change education into practice. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000233083

- Wibeck, V . (2014). Enhancing learning, communication and public engagement about climate change: Some lessons from recent literature. Environmental Education Research , 20 (3), 387–411. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2013.812720

- Williams, S. , McEwen, L. J. , & Quinn, N . (2017). As the climate changes: Intergenerational action-based learning in relation to flood education. The Journal of Environmental Education , 48 (3), 154–171. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2016.1256261

- Wolf, J. , & Moser, S. C . (2011). Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change , 2 (4), 547–569. doi: 10.1002/wcc.120

- Zaval, L. , & Cornwell, J. F. M . (2017). Effective education and communication strategies to promote environmental engagement. European Journal of Education , 52 (4), 477–486. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12252