Abstract

Enhancing customer loyalty is the ultimate goal of relationship marketing. While prior studies have highlighted the significance of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes as key drivers of consumer behavioral loyalty, literature, especially in the service context has left ambiguities regarding: (1) integrative exploration of mechanisms mediating attitudes’ impact on behavioral loyalty; and (2) the specific components and connections between attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, along with their origins. This study introduces a novel integrative model that delves into the distinct effects of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes on components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, shedding more light on understanding the interplay between these components, their relationships, and their functional connections with trust and attitudes. Structural Equation Modeling was applied to the survey results from 1,028 participants, with the results demonstrating how hedonic and utilitarian attitudes differently impact various components of behavioral loyalty through mediation of trust and attitudinal loyalty components. Furthermore, results show that relationships varied across different services. The findings will help service firms to identify important predicting factors and channels of service behavioral loyalty, thus enabling them to optimize the costs of customer-service relationship management.

Introduction

Firms benefit from customer loyalty in numerous ways. For example, a loyal customer base can result in a greater market share, higher relative prices, lower marketing costs, greater trade leverage, improved sales performance, and favorable word of mouth (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Dick & Basu, Citation1994; Gremler et al., Citation2020; Watson et al., Citation2015). In addition, maintaining a loyal customer base is a key competitive advantage for many companies, and it is cheaper than attracting new consumers (Verma et al., Citation2016). From the consumer’s perspective, loyalty also provides relational benefits (Gremler et al., Citation2020), fosters emotional attachment to products and firms, and reinforces consumer identity and relationship satisfaction (Coelho et al., Citation2018; Crosby et al., Citation1990; Fournier, Citation1998). The questions of what loyalty is and how consumers become loyal are critical to both researchers and managers, especially in the current era of declining loyalty (Kumar & Reinartz, Citation2018). Evaluating several research on loyalty shows that traditional cognitive predictors are not enough to maintain consumer loyalty and affective predictors are more important in building loyalty (Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2022). The prevailing economic view posits that improving service quality in utilitarian channels will result in increased product demand, which will, in turn, strengthen behavioral loyalty (e.g., re-purchase intentions and actual purchases). However, this study proposes that behavioral loyalty is determined by various hedonic and utilitarian attitudes via mediation channels such as trust, satisfaction, commitment, and identification; additionally illustrates the importance of other consumer behavioral responses, such as word of mouth and cooperation (rather than just re-purchase intentions), as well as their predicting mechanisms. For instance, although price reduction may stimulate utilitarian attitudes, it does not directly lead to behavioral loyalty. Tim Horton’s serves as a good illustration of this principle. Tim Horton’s has successfully utilized a strategy based on lower prices (i.e., utilitarian channel) and its Canadian identity (i.e., hedonic channel) to foster consumer loyalty in Canada. However, this strategy has been much less successful in the US due to the hedonic channel constraint (e.g., hedonic attitudes, affective commitment, or identification). Thus, obtaining a more robust understanding of the different components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, as well as their functional relationships with hedonic and utilitarian attitudes, is of both theoretical and empirical interest.

Early theorists largely viewed loyalty in behavioral terms (i.e., repurchase actions); however, others have suggested that a comprehensive evaluation of loyalty should include an assessment of consumer beliefs, affect, and attitudes (Oliver, Citation1999). Thus, accepted contemporary definitions of loyalty include both the behavioral (e.g., repurchase actions) and attitudinal (e.g., sensitivity to some unique value associated with a product or brand) aspects of loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999). This research builds on prior conceptualizations of loyalty as a multidimensional construct consisting of both attitudinal and behavioral aspects by providing a more in-depth account of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty and their relationship to one another (Aurier & de Lanauze, Citation2012; Cachero-Martínez & Vázquez-Casielles, Citation2021; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014). Given the limited understanding of behavioral and attitudinal loyalty components, the first objective of this study is to determine their constituent dimensions (RQ1). The second objective of this research is to elucidate the relationship between attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (RQ2); indeed, despite the fact that prior research has empirically shown that attitudinal loyalty influences behavioral loyalty (Bandyopadhyay & Martell, Citation2007; Watson et al., Citation2015; Zietsman et al., Citation2023), little is known about the relationship among components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty.

It has been argued that a consumer’s perception of a product or service is shaped by their experiences with its functional (or rational, utilitarian) and emotional (or affective, hedonic) properties over time (Aaker et al., Citation2004; Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Homer, Citation2008). To explain consumer attitudes, researchers have implemented a two-factor view of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes founded on the fact that consumption is initially driven by hedonic and utilitarian motives (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Batra & Ahtola, Citation1991; Chitturi et al., Citation2008). Hedonic and utilitarian attitudes are important antecedents of consumer behavior (Cronin & Taylor, Citation1992; Voss et al., Citation2003) that can be manifested by behavioral loyalty. Nonetheless, little is known about the relationship between hedonic and utilitarian attitudes and the different dimensions of loyalty. This gap is both practically and theoretically important, as the ultimate goal of relationship marketing strategies is to foster and maintain long-term customer loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Dick & Basu, Citation1994; Watson et al., Citation2015). This research addresses this gap by identifying and assessing various relational factors (e.g., trust, commitment, identification, and relationship satisfaction) that may mediate the relationship between attitudes and loyalty formation (Chatzi et al., Citation2024; Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014; Sirdeshmukh et al., Citation2002; Verma et al., Citation2016). Thus, the third objective of this research is to examine how hedonic and utilitarian attitudes impact attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (RQ3).

Researchers have argued that relational variables such as attitudes, trust, satisfaction, and commitment play a role in predicting loyalty (Ball et al., Citation2004; Chatzi et al., Citation2024; Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Gremler et al., Citation2020; Molinillo et al., Citation2022). Prior findings have shown that the influence of attitude on loyalty is mediated by feelings of trust and commitment (Ball et al., Citation2004; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Sirdeshmukh et al., Citation2002). Although the existence of relational mediators has been well-established in the relationship marketing literature, little is known about how they simultaneously function in connecting attitudes to behavioral loyalty. As such, the fourth objective of this research is to assess how key relational mediators, such as trust and commitment, function in the attitude-loyalty relationship (RQ4).

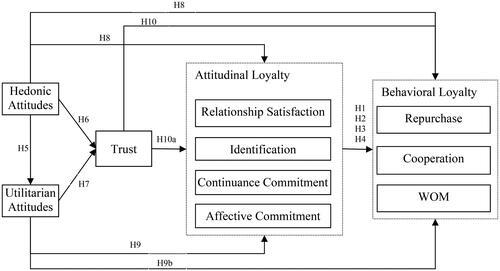

To investigate these four research questions, we identify several dimensions of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty and test them using an integrative model in order to determine how they relate to each other, how they are influenced by various hedonic and utilitarian attitudes, and how trust impacts each component of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. In this study, four components of attitudinal loyalty—relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, affective commitment, and identification—and three components of behavioral loyalty—repurchase intentions, cooperation, and word-of-mouth (WOM)—will be examined. The obtained results confirm the proposed model’s excellent explanatory power, and reveal several important channels of influence that explain the mediation mechanism between attitudes and loyalty.

This study makes significant theoretical contributions by introducing a novel integrative model that delves into the distinct effects of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes on components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, as well as trust, in the realm of service relationship marketing. It explores 90 channels of influence, some underexplored in literature. This research offers a substantial theoretical advancement by integrating these channels into a well-fitted, functional model that elucidates the mediation links from attitudes to behavioral loyalty. Previous literature has often overlooked this integrative approach, leading to inconsistent results or providing an incomplete and ineffective understanding of behavioral loyalty formation. Additionally, the study result demonstrates that the mediation mechanism from attitudes to behavioral loyalty varies across different service contexts.

From a managerial perspective, understanding the significant predictors of each behavioral loyalty component can facilitate a more efficient allocation of resources to enhance consumer responses. Additionally, companies focusing on loyalty through repurchasing should also prioritize positive word-of-mouth and cooperation. Furthermore, understanding the channels of influence from attitude to loyalty across different services, equips managers to refine customer relationship strategies for maximum cost-effectiveness and stronger customer-firm bonds.

Literature review and conceptual development

Loyalty

Marketing researchers have conceptualized loyalty as consisting of two core components: attitude and behavior (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014; Watson et al., Citation2015). However, conceptualizations of loyalty that emphasize these two components and their related sub-components remain flawed, as they do not adequately describe the positioning of the concept and its components within the service relational exchange process (Gremler et al., Citation2020). Therefore, one important contribution made by this research is to fill this gap by offering a more robust conceptualization of loyalty’s components and how they function within the buyer-seller relationship in a service context.

Behavioral loyalty components

Traditionally, definitions of behavioral loyalty have been strongly tied to the notion of “re-purchase” (e.g., Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999). As such, most prior studies have employed a unidimensional operationalization of behavioral loyalty (Zeithaml et al., Citation1996). However, the fact remains that behavioral loyalty can manifest in multiple ways, for instance, when consumers speak positively about or recommend a brand to others (Sweeney & Swait, Citation2008; Zeithaml et al., Citation1996), or co-create value in the production or delivery of a service (Yim et al., Citation2012). We propose that repurchase intentions, cooperation, and word of mouth (WOM) are the three key dimensions of behavioral loyalty, as loyalty is meaningless, or at least meaningless with respect to consumer behavior, in their absence.

Repurchase intentions

It has been well-established that repurchase intentions are a relevant part of loyalty (Bayus, Citation1992; Dagger & O’Brien, Citation2010; Dick & Basu, Citation1994; Zeithaml et al., Citation1996). For instance, (Bayus, Citation1992) operationalized loyalty as the probability of repurchase, while (Dick & Basu, Citation1994) argued that repeated patronage is a defining feature of loyalty. In addition, Zeithaml et al. (Citation1996) showed that favorable purchase intentions are a key factor in positive long-term consumer-company relationships. Finally, research has also demonstrated that loyal consumers exhibit repurchase behaviors (Dagger & O’Brien, Citation2010).

Cooperation

Cooperation refers to multiple parties working together to achieve shared goals (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). In other words, cooperation is a behavioral outcome of relational exchange (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Palmatier et al., Citation2006). Recently, a similar construct has become prominent in the marketing literature. This concept, known as “co-production” (Auh et al., Citation2007)—or in the service domain, “co-participation” (e.g., Yim et al., Citation2012)—refers to the effort and time consumers spend sharing information, making comments, and engaging in a company’s decision making, which creates value for both the consumer and the company (Auh et al., Citation2007; Yim et al., Citation2012). Since cooperative contribution is foundational to all of the aforementioned constructs (Auh et al., Citation2007), we focus on cooperation instead of co-production and co-participation, as it is a broader term that goes beyond service-related contexts, which are usually the focal point of co-production/participation.

Although prior studies have conceived of cooperation as a distinct relational outcome of loyalty (Palmatier et al., Citation2006) or as a predictor of loyalty (e.g., Auh et al., Citation2007; Yim et al., Citation2012), we propose that cooperation is an aspect of behavioral loyalty for three reasons. Firstly, cooperation is an important behavioral outcome of an exchange relationship (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Palmatier et al., Citation2006). Secondly, both theory and empirical evidence indicate that commitment and trust between exchange partners promote cooperation (Auh et al., Citation2007). Finally, loyalty and cooperation have been linked both theoretically and empirically, as findings have shown that loyal consumers are usually willing to cooperate with the firm (Auh et al., Citation2007). Therefore, cooperation explains the notion of behavioral loyalty, despite being distinctly different from the behavioral construct that traditionally defines loyalty: repurchase intentions.

Word of mouth (WOM)

WOM can have a significant influence on whether a consumer will buy a product or employ a service (Kozinets et al., Citation2010). Consumers who have a strong positive relationship with a brand/product, advocate for and advertise it via WOM (Reynolds & Beatty, Citation1999). Thus, WOM is an important outcome of relational marketing (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002; Palmatier et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, findings have consistently shown that most of the components of attitudinal loyalty exert a positive influence on WOM (Watson et al., Citation2015; Zeithaml et al., Citation1996). Therefore, since loyal consumers usually engage in positive WOM about their preferred brands or services, we propose WOM as an important conceptual component of behavioral loyalty.

Attitudinal loyalty components

Findings suggest that consumers who have developed a relationship with a service provider will be more likely to be loyal to it in the future (Aurier & de Lanauze, Citation2012). Based on prior literature, we propose four dimensions of attitudinal loyalty: (1) relationship satisfaction, (2) continuance commitment, (3) affective commitment, and (4) identification. In the following sub-sections, we detail how these four dimensions cover all facets of attitudinal loyalty.

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction refers to consumers’ “affective or emotional state toward a relationship, usually evaluated cumulatively over the history of the exchange” (Palmatier et al., Citation2006, p. 138) and is a predictor of behavioral loyalty (Crosby et al., Citation1990; Pallas et al., Citation2014; Reynolds & Beatty, Citation1999; Verma et al., Citation2016; Zietsman et al., Citation2023). Since the study emphasizes long-term relational concepts over transactional ones, we included relationship satisfaction, which encapsulates repeated satisfaction with service quality over time (Homburg et al., Citation2005). Prior studies have examined the ability of overall satisfaction to predict repurchase intentions (e.g., Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alema, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014). Studies show that satisfaction is an affective predictor of loyalty (Chatzi et al., Citation2024; Dick & Basu, Citation1994; Hsu & Lin, Citation2023; Molinillo et al., Citation2022). It also helps to retain customers by increasing their purchase intentions—a behavioral aspect of loyalty (Cronin & Taylor, Citation1992; Pallas et al., Citation2014). Researchers have also shown that satisfaction is an attitudinal-based condition that companies cultivate by meeting their customers’ expectations (Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014; Parasuraman & Grewal, Citation2000). Furthermore, (Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014) has argued that satisfaction is an attitudinal-based building block of loyalty. In fact, it is a key part of loyalty, as consumers who are satisfied with their relationship with a firm are usually loyal to that firm (Watson et al., Citation2015). Thus, we conceptualize relationship satisfaction as a component of attitudinal loyalty.

Numerous studies have supported that satisfaction leads to positive WOM (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002; Pallas et al., Citation2014; Reynolds & Beatty, Citation1999; Sakiyama et al., Citation2023). For example, consumers who are satisfied with a product or service are very likely to advocate in favor of the supplying company (Crosby et al., Citation1990). Other studies suggest that highly satisfied consumers will purchase substantially more products or services from a company than less satisfied consumers (Zeithaml et al., Citation1996). We refer to Palmatier et al. (Citation2006) findings, which establish relationship satisfaction as an important relational mediator that leads to positive WOM, cooperation, and loyalty. Therefore, we define relationship satisfaction as a cumulative attitudinal-based aspect of attitudinal loyalty, and, following the mentioned literature, we argue for its role as an antecedent of behavioral loyalty components, such as repurchase intention, WOM, and cooperation.

H1a, b, c: Relationship satisfaction positively influences (a) repurchase intentions, (b) consumer cooperation, and (c) WOM.

Commitment

The relationship marketing literature posits that commitment is an indispensable component of successful long-term relationships (Iglesias et al., Citation2011; Keiningham et al., Citation2015; Palmatier et al., Citation2006; Verma et al., Citation2016). Within a consumer context, businesses work to develop and maintain their customers’ commitment, thus positioning commitment as the central component of all successful relational exchanges (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Although (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) propose that trust and commitment are key mediators in relational marketing, others have argued that commitment alone is the key relational mediator (e.g., Gruen et al., Citation2000).

The marketing literature focuses on two major types of commitment: affective commitment and continuance commitment (or calculative commitment) (Fullerton, Citation2003, Citation2005; Iglesias et al., Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2006). Although several marketing studies have analyzed commitment as a unidimensional construct (e.g., Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994) other studies have treated it as a multidimensional construct (e.g., Bansal, Irving, & Taylor Citation2004; GruenSummers, & Acito 2000; Gustafsson et al., Citation2005; Iglesias et al., Citation2011; Keiningham et al., Citation2015). Ultimately, the results of studies taking a multidimensional view of commitment have proven to be more adept at explaining commitment and its role as a mediator in relational exchange. In the present study, we empirically test and compare both views to confirm the superiority of the multidimensional view, which contradicts the findings of Petzera and Roberts-Lombard (Citation2022).

In the marketing literature, commitment is often presented as a predictor of loyalty (Fullerton, Citation2005; Palmatier et al., Citation2006; Verma et al., Citation2016; Watson et al., Citation2015), particularly behavioral loyalty. (Keiningham et al., Citation2015) summarized all of the studies that analyze the commitment-loyalty relationship, and developed a five-factor model of commitment that explains how it influences repurchase intentions. Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) empirically demonstrated the relationship between a consumer’s level of commitment and indicators of behavioral outcomes such as acquiescence, propensity to leave, and cooperation. In other studies, findings have suggested that brand loyalty is a facet of commitment (Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999), or a construct that is like commitment (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Assael (Citation1984) defines brand loyalty as a "commitment to a certain brand" that is rooted in certain positive attitudes, while (Oliver, Citation1999) defines it as a “deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize”. Chaudhuri and Holbrook (Citation2001) would later add nuance to the brand loyalty literature, arguing for the existence of various levels of commitment in attitudinal brand loyalty. Furthermore, (Park & Kim, Citation2000) empirically applied a three-factor model of commitment to explain several loyalty dimensions. One of the theoretical contributions of this research is that we address the aforementioned inconsistencies regarding the conceptualizations of commitment and loyalty. To achieve this goal, we assert continuance (or calculative) commitment and affective commitment (Fullerton, Citation2003, Citation2005; Iglesias et al., Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2006) as two distinct facets of attitudinal loyalty that predict behavioral loyalty.

Continuance commitment

Continuance commitment is rationality based, as it depends on the relationship benefits that accrue due to a lack of alternatives or the existence of high switching costs such as economic, social, and status costs (Johnson et al., Citation2006). Continuance commitment is also characterized by a sense of moral obligation to a company, and a desire for relationship consistency over time (Gruen et al., Citation2000; Palmatier et al., Citation2006). Findings have shown that continuance commitment positively affects consumer retention (Gustafsson et al., Citation2005) and leads to relational-based participation (Gruen et al., Citation2000). However, findings relating to the commitment-WOM relationship have been mixed. Although some researchers argue that continuance commitment positively influences WOM (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002; Sweeney & Swait, Citation2008), some findings suggest that consumers who feel trapped in a relationship due to high switching costs or lack of alternatives may forego positive WOM, and may actually engage in negative WOM instead (Fullerton, Citation2003; Harrison-Walker, Citation2001).

Affective commitment

Affective commitment refers to a consumer’s attachment or psychological bond to a firm, brand, product, or service based on the perception of favorableness and is more emotional than rational in nature (Gruen et al., Citation2000; Iglesias et al., Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2006). Dick and Basu (Citation1994) have argued that affect is an important factor in loyalty. This is supported by findings that indicate emotional or psychological attachment to a brand is a key factor in developing and maintaining consumer loyalty (Evanschitzky et al., Citation2006). Furthermore, other researchers have demonstrated that affective commitment influences both behavioral loyalty (Fullerton, Citation2003) and attitudinal loyalty (Aurier & de Lanauze, Citation2012). For example, Evanschitzky et al. (Citation2006) found that affective commitment drives behavioral loyalty, while (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alema, Citation2001) demonstrated that emotional and psychological bonds will result in brand loyalty. Furthermore, other studies have shown that affective commitment also predicts cooperation (Auh et al., Citation2007), leads to positive WOM (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002; Sakiyama et al., Citation2023; Sweeney & Swait, Citation2008), and positively affects consumer advocacy intentions (Fullerton, Citation2003). Although these studies employ different terms for affective commitment in different contexts, all of them introduce and examine a construct that is attitudinal and affective in nature, and that predicts long-term behavioral intentions. Thus, we posit affective commitment as a dimension of attitudinal loyalty that predicts various aspects of behavioral loyalty (i.e., repurchase intentions, cooperation, and WOM).

H2a, b, c: Continuance commitment is positively related to (a) repurchase intentions and (b) cooperation, but (c) is negatively related to WOM.

H3a, b, c: Affective commitment positively affects (a) repurchase intentions, (b) cooperation, and (c) WOM.

Identification

Some have argued that identification is the main driver of consumer-company relationships, as it helps fulfill one or more important self-definitional needs, such as a sense of belonging, attachment, membership, and identity (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003). Oliver (Citation1999) has argued that high social support and high individual fortitude lead to the “immersed self-identity” characteristic, which captures the socio-emotional side of loyalty, and goes beyond the cognitive-affective-conative-action sequence. Consumers immerse their self-identities into the social system of which the brand/firm is a part, which in turn supports/reinforces their self-concept. Thus, consumers tend to desire products or services that relate to their social environment (Oliver, Citation1999). In addition, identification (i.e., the social identity that is a main consequence of brand community) has been shown to lead to loyalty, satisfaction, and involvement (Chatzi et al., Citation2024; Coelho et al., Citation2018; Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2010). Identification compels people to mentally attach themselves to companies that can provide them with a social identity. As a result, consumers who strongly identify with a company are more likely to interact positively and cooperatively in relational exchanges, commit to repurchasing the company’s products, and promote the company (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003). Finally, it has been shown that identification positively affects WOM (Tuškej et al., Citation2013). Altogether, the next set of hypotheses posits that identification is positively related to the components of behavioral loyalty.

H4a, b, c: Consumer identification with a brand positively affects (a) repurchase intentions, (b) cooperation, and (c) WOM.

Attitudes

This study integrates the literature on attitudes into the relationship marketing model, as it has been well-established that attitudes lead to a variety of behavioral outcomes, including loyalty. The dominant line of thought on this subject is based on the theory of reasoned action (Azjen & Fishbein, Citation1980) and, to some extent, its revised version, the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation2020). Together, these two theories explain how a consumer performs a certain buying behavior, and they notably introduce attitudes as a predictor of behavioral intentions and, consequently, actual behavior.

Attitudes are enduring associations of an object assessment that are saved in memory. To form enduring attitudes, several transactions may be required, or, in the absence of transactions, attitudes may be shaped by external information or social norms (e.g., a person may have a positive attitude about Mercedes-Benz without ever having owned or driven one). Therefore, the scope of this study includes both clients and non-client consumers. In addition, attitudes are complex and multidimensional (Voss et al., Citation2003). As such, marketing scholars have evaluated the affective and instrumental aspects of attitudes based on the fact that consumption is driven by two basic motives: hedonic (affective) and utilitarian (instrumental) motives (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Batra & Ahtola, Citation1991; Chitturi et al., Citation2008; Homer, Citation2008; Pallas et al., Citation2014). Hedonic motives are linked to the emotional sensation from the experience of using a product (e.g., pleasurable sense of going to Disney world), while utilitarian motives are driven from functions performed by the product itself (the good sense from the function of a banking service). Recently, researchers have found that bi-dimensional (utilitarian/hedonic) conceptualizations of attitudes are better at explaining attitudes’ variances than unidimensional approaches (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Homer, Citation2008; Voss et al., Citation2003).

Researchers have also suggested that hedonic and utilitarian values and attitudes influence relational elements, such as trust, commitment, and loyalty to a brand, firm, or product (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Liu-Thompkins et al., Citation2022; Voss et al., Citation2003). However, an important theoretical gap remains with respect to how changes in attitudes translate into changes in loyalty. This study aims to determine whether this influence is direct or indirect via a mediating process. Although a number of studies have shown that both hedonic and utilitarian attitudes directly predict behavioral intentions (e.g., Voss et al., Citation2003), this relationship appears to be more complex. Indeed, as several other studies have shown, the relationship between attitudes and behavioral intentions (e.g., loyalty) is influenced by intervening mediators such as trust, commitment, and satisfaction (e.g., Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Harris & Goode, Citation2004). Thus, this mediation process likely occurs through different channels based on the stimulation of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes.

To the best of our knowledge, the marketing literature contains no solid findings confirming the relationship between utilitarian and hedonic attitudes. In fact, studies examining the nature of this relationship have produced conflicting results. For instance, while studies suggest that the two attitude types are independent (Voss et al., Citation2003), other studies depict that utilitarian attitudes are explained, at least in part, by hedonic attitudes. The latter notion is underpinned by the literature referred to as “affect-as-information” (Schwarz, Citation2011; Schwarz & Clore, Citation2007), which affirms hedonic attitudes are a source of utilitarian attitudes (Pham, Citation2004). Studies have shown that consumer evaluations of objects are not strictly rational; rather, such evaluations are also influenced by their feelings and emotions, as people perceive feelings as a valuable source of information when making judgments and decisions (Schwarz, Citation2011). Accordingly, we argue that hedonic attitudes that take the form of emotional evaluations of an object (Alba & Williams, Citation2013) predict utilitarian attitudes in the same way as other cognitive predictors (Schwarz, Citation2011). Thus, we test the following hypothesis:

H5: Hedonic attitudes have a positive and direct effect on utilitarian attitudes.

H6: Hedonic attitudes have a positive and direct effect on trust.

H7: Utilitarian attitudes have a positive and direct effect on trust.

Based on the theory of reasoned action (Azjen & Fishbein, Citation1980) attitudes predict intentions and behaviors. Although, the argument set forth in this study is generally based on the logic of attitudes-behavior theory (Ajzen, Citation2020), there is evidence that utilitarian attitudes (as evoked by quality and service function) influence attitudinal aspects of consumer-firm relationship such as satisfaction (Cronin & Taylor, Citation1992). In addition, prior research has shown that both utilitarian and hedonic attitudes predict purchase intentions (Hepola et al., Citation2020; Voss et al., Citation2003). Thus, we argue that hedonic and utilitarian attitudes directly affect the components of both attitudinal and behavioral loyalty.

H8a: Hedonic attitudes positively influence relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, affective commitment, and identification.

H8b: Hedonic attitudes positively influence repurchase intentions, consumer cooperation, and WOM.

H9a: Utilitarian attitudes positively influence relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, affective commitment, and identification.

H9b: Utilitarian attitudes positively influence repurchase intentions, consumer cooperation, and WOM.

Trust

There is evidence that consumer attitudes influence their levels of trust (Ball et al., Citation2004; Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Homer, Citation2008). Furthermore, trust is related to both behavioral and attitudinal loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). It is undeniable that companies must first gain the trust of consumers before they can secure their commitment and loyalty, as trust is the foundation of highly valued exchange relationships (Fournier, Citation1998; Harris & Goode, Citation2004; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Sirdeshmukh et al., Citation2002). Firms build trust through their behaviors and practices, which in turn leads to consumer loyalty (Aurier & de Lanauze, Citation2012; Watson et al., Citation2015), commitment (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Wong, Citation2023), and behavioral intentions (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Overall, prior research has established trust as a primary mediator in the relational exchange; however, this research aims to further expand on this relationship by showing that trust directly and indirectly influences behavioral loyalty. With regards to the latter claim, we contend that trust indirectly affects behavioral loyalty through the partial mediation of attitudinal loyalty (). Thus, we state two general hypotheses below:

H10a: Consumer trust positively predicts relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, affective commitment, and identification.

H10b: Consumer trust positively predicts repurchase intentions, consumer cooperation, and WOM.

Empirical methodology

A pilot study was conducted using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to test the relationships between the key constructs. In this study, the participants were asked to indicate their views about their primary financial institution. We recruited 177 undergraduate students (94 males, 53%) from a Canadian university through the marketing subject pool. The results of the pilot study demonstrated very good fit indices for both the measurement model (χ2/df = 2.53; CFI = .943; RMSEA = .054; 051 < 90% CI < .057; PCFI = .817; PNFI =.787) and the structural model (χ2/df = 2.600; CFI = .938; RMSEA = .056; 053 < 90% CI < .059; PCFI = .820; PNFI =.790). The findings also showed very good psychometric characteristics for the several measures and their overall structural relations. Furthermore, a separate pretest, using 56 undergraduate students, showed that participants ranked pharmacy and financial service as the most utilitarian, and luxury hotel and restaurant/bar as the most hedonic services among eight tested services.

Measures

To assess attitudes, we utilized Voss et al. (Citation2003) 10-item measure of the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of brand/product attitudes (αHA=.947; αUA=.882). Hedonic attitudes (HA) were measured using the phrase, “I think this service company is,” in conjunction with five items, which were assessed on a 7-point semantic-differential scale using the following polar adjectives: fun, exiting, delightful, thrilling, and enjoyable. Utilitarian attitudes (UA) similarly were measured using the following polar adjectives: effective, helpful, functional, necessary, and practical. The trust measure was adapted from Chaudhuri and Holbrook (Citation2001), and consisted of four items (α=.883) that were intended to assess the reliability of the company/product/brand on a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement: “I trust this …”, “I rely on this…”, “This is an honest … “, and “This … is safe.” To assess satisfaction with the relationship, six items (α=.960) were measured using a 7-point semantic-differential measure, anchored by, “pleased me”, “contented with”, “very satisfied with”, “happy with “, and “frustrating” (Bansal et al., Citation2004; Jones et al., Citation2000; Reynolds & Beatty, Citation1999). Furthermore, identification was assessed using six items (α=.913) adopted from Aaker et al. (Citation2004). These items were measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale to determine the degree of consumers’ “self-connection” with a brand/company. The affective commitment scale (Auh et al., Citation2007; Bansal et al., Citation2004) includes four reversed items (α=.951), which were assessed using a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement. These items measured the participants’ emotional or desire-based attachment to a service provider. The continuance commitment measure was adopted from Bansal’s et al. (Citation2004) work. For this measure, participants were asked to indicate their level of agreement with three items (α=.865)—“It would be very hard for me to leave my financial institution right now, even if I wanted to”, “Too much of my life would be disrupted if I decided I wanted to leave my financial institution now”, and “I feel that I have too few options to consider leaving my financial institution”—using a 7-point Likert-type scale.

Repurchase intentions measures were extracted from the extant research on behavioral intentions (e.g., Jones et al., Citation2000). This measure included four items (α=.938), which were assessed using a 7-point semantic-differential scale. The items were introduced with the phrase, “Please rate the probability that you will continue using your current financial institution in the future,” and were anchored by “likely”, “probable”, “possible”, and “certain”. These items aim to assess the likelihood of repeating consumer purchase from a service company. The four items (α=.922) of the cooperation scale were adopted from Yim et al. (Citation2012) and used in conjunction with a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement to assess levels of participation and involvement in the delivery and process of a service. Finally, positive WOM was measured via a three-item (α=.959) scale adapted from (Sweeney & Swait, Citation2008), and was assessed using a 7-point Likert-type scale of agreement. This scale assesses the extent to which consumers talk positively about, recommend, and encourage others to use a service.

Main study

Procedure

As in the pilot study, the main study employed a survey-based (internet) approach and similar measures. After reading the study summary and completing the informed consent form, participants were randomly asked about four services, including two hedonic (restaurant/bar and luxury hotel) and two utilitarian (financial service and pharmacy) services. As in the pilot study, established scaling measures were employed for all variables. Finally, participants were asked to answer several demographic questions related to age, gender, primary language spoken at home, ethnicity, household income, nationality, educational level, and family structure.

Data analysis

Given the properties of the study’s theoretical model, data were analyzed using a combination of factor analysis and path analysis. First, we cleaned the data set and then conducted Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using SPSS to evaluate the factor structure and reliability of measures. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was then implemented to confirm the reliability and validity of the model’s factor structure and measurements. Finally, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was conducted to assess the structural characteristics of the estimation model.

Sample

The main study sample consisted of 1,028 respondents (520 male, 50.6%) recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), with each participants receiving one US dollar in exchanged for completing the survey. Several papers have demonstrated the validity of research using MTurk data (Chandler et al., Citation2014). The participants primarily resided in the United States at the time of data collection, and summary statistics indicated that our sample constituted a balanced representation of the US consumer population. The sample demographics broke down as follows: 90.7% spoke English at home; 74.7% identified as American, 16.6% identified as Indian, and 8.7% identified as “other” or did not specify; 62.3% was White; 99.3% had completed high school or some higher level of education; 37.6% reported being single; median age was 25-34 years; and median household income was $35,000-$49,999. Furthermore, age, income, and education measures in our sample had good distributional characteristics, as the skewness and kurtosis statistics of these factors fell within the acceptable range (-1< skewness< 1, −1< kurtosis< 1).

Post-hoc data cleaning is common procedure to improve the quality of the data obtained from the MTurk panel (Chandler et al., Citation2014). As a result of this procedure, 12.3% of the surveys were excluded due to incomplete and/or unengaged responses. Thus, the final analysis consisted of 902 usable surveys (233 for pharmacy, 245 for financial institution, 237 for restaurant/bar, and 187 for luxury hotel). Additionally, the “mean substitution method” was used to deal with missing value data for all variables aside from the descriptive demographic characteristics. It is worth noting that “items missing value percentages” were less than 0.4% across all constructs in this stage.

Results

As expected, the 10 variables in the model all demonstrated very strong convergent and discriminant validity. All item loadings on related variables were higher than 0.5, and the average loading for each variable was higher than 0.7, thus indicating strong convergent validity. In terms of discriminant validity, there was no cross loading among the variables’ items (within a cutoff point of .3 and higher). Cronbach’s Alphas were higher than 0.7 for each measure, which indicates strong internal reliability.

The unidimensionality of the hedonic and utilitarian attitudes, and the components of behavioral and attitudinal loyalty, were all confirmed via principle component extraction analysis. The analysis identified that two unique factors explained 77.2% of the observed variance in attitudes, four distinct factors explained 81.6% of the observed variance in attitudinal loyalty, and three distinct factors explained 84.7% of the observed variance in behavioral loyalty. The rotation analysis results also confirmed the unidimentionality of the components, showing that all item loadings were higher than 0.6 for the related factors and lower than 0.3 for other factors.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

In order to confirm the measurement model’s (factor structure from the previous section) validity and the goodness of fit, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis via SEM (Amos 20). The measurement model includes 38 items across 10 constructs (see for more detail on construct correlations). We also conducted invariance tests among the four service groups by checking the Z-score of the item loadings. This test was conducted to confirm that the data from the four services could be combined to test our model. The results of the invariance tests showed that continuance commitment was the only construct that differed significantly among the four services, which implies that it is context-specific. Furthermore, the invariance test between hedonic and utilitarian services, as well as between client and non-client status, for each service did not show any significant differences with regards to the model constructs. Thus, the study framework explains the attitude and behavior of consumers in general, and is not limited to user/non-user type.

Table 1. Main study construct correlations.

Given the relatively large sample size (n = 902) and number of constructs, it is not surprising that the χ2 is significant (χ2 = 1738.96, df = 618, p < .001). However, the relative chi-square (χ2/df) is very good (2.81). The measurement model indices were as follows: Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.939; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.055 (0.051 < 90% CI <0.057); Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index (PCFI) =0.851; and Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PNFI) = 0.836. The latter two adjusted indices penalize the complexity of the model, which is why the simple model contains higher parsimonious indices. Altogether the measurement model indices demonstrate very good fit.

Reliability and validity

As shown in , the estimates of each measurement scale (construct reliability) exceeded a value of 0.60, and all average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded a value of 0.50, thus supporting good internal reliability. Construct loadings and AVEs were used to assess convergent validity; all loadings on the hypothesized factors were larger than 0.70 and statistically significant (p < .001), and the AVEs were greater than the suggested cutoff point of 0.6. With regards to discriminant validity, the square roots of the AVEs were greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlations. Furthermore, multicollinearity was not an issue, as all variance inflation factors (VIF) of variables in the same level (e.g., attitudinal and behavioral loyalty components) were less than 3. Finally, procedural remedies of common method bias and common latent factor (CLF) analysis (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003) were used to confirm that there was no common method bias.

Structural equation modeling-SEM (test of hypotheses)

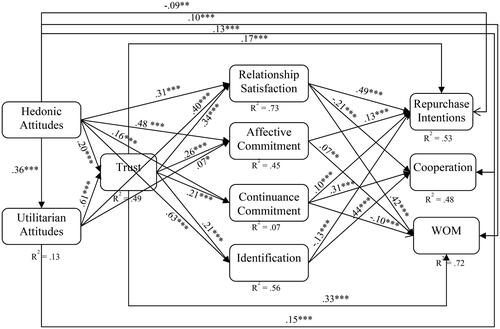

We estimated the fully proposed model using simultaneous path analysis in SEM (). Although the χ2 was significant (χ2 = 1829.55, df = 625, p < .001), the relative chi-square was lower than 3, which meets the acceptable criteria (χ2/df = 2.927). The fit indices were as follows: CFI = 0.966; RMSEA= 0.046, 0.044 < 90% CI < 0.049; PCFI = 0.858; and PNFI = 0.844. Both the RMSEA and CFI indices met the acceptable cutoff criteria for a good fit. These results show that the proposed model has a very good overall fit with the sample data, and that it has strong explanatory power with respect to the observed covariances among the study constructs.

With regards to this study’s second objective (RQ2), the model explains how the components of attitudinal loyalty affect the components of behavioral loyalty, thus addressing Hypotheses 1 through 4. As the results show, relationship satisfaction positively and significantly affected repurchase intentions (β = .49***) and WOM (β = .42***), but negatively affected cooperation (β = −.21*). Therefore, only H1a and H1c are supported. Continuance commitment positively affected repurchase intentions (β = .10***) and cooperation (β = .31***), but negatively affected WOM (β = −.10***), again supporting H2a, H2b, and H2c. Furthermore, affective commitment only had a positive effect on repurchase intentions (β = .13***) and WOM (β = .07**), but not on cooperation, thus only supporting H3a and H3c. Identification had a positive effect on cooperation (β = .44***) and a negative effect on repurchase intentions (β = −.13**), which supports H4b, but not H4a and H4c.

Hedonic attitudes had a positive, direct, and significant effect on cooperation (β = .13***)Footnote1 and WOM (β = .10***), but a negative, direct, and significant effect on repurchase intentions (β = − .09**)Footnote2, which provides partial support for H8b. Conversely, utilitarian attitudes only had a positive, direct, and significant effect on repurchase intentions (β = .15***), but not on cooperation and WOM, which partially supports H9b. This result indicates that favorable opinions about the function of a service directly lead consumers to repurchase that service. On the other hand, hedonic attitudes had a direct and significant effect on utilitarian attitudes (β = .36***); this supports the notion of “affect-as-information,” which holds that hedonic attitudes are source of utilitarian attitudes (Pham, Citation2004; Schwarz & Clore, Citation2007). The low number of beta coefficients in the direct effects of attitudes on behavioral loyalty is further evidence of the existence of indirect effects in the relationship ( and ).

Figure 2. Main study full model coefficients.

Note: Only significant relationships are shown in the model; “*” represents p < .1, “**” represents p < .05, and “***” represents p < .01.

With respect to mediators, hedonic attitudes had a significant and direct effect on both utilitarian attitudes (β = .36***) and trust (β = .20***). Utilitarian attitudes also had a significant and direct effect on trust (β = .61***). These significant effects provide evidence that utilitarian attitudes partially mediate the relationship between hedonic attitudes and trust. Thus, favorable opinions about the utility value of a service play an important role in building consumer trust and mediate the effects of favorable emotions on trust, thus supporting H5, H6, and H7. Furthermore, hedonic and utilitarian attitudes explain 49% of the variance in trust (R2 = .49). The higher beta coefficient of the relationship between utilitarian attitudes (vs. hedonic attitudes) and trust implies that utilitarian attitudes explain more of the variance in trust than do hedonic attitudes. Utilitarian attitudes do not affect continuance commitment and identification, but they do affect relationship satisfaction and affective commitment; in contrast, hedonic attitudes affect all components of attitudinal loyalty.

The fourth objective of the study (RQ4) concerns the role of trust and its effects on the components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. Trust had a positive and significant effect on all components of attitudinal loyalty, including relationship satisfaction (β = .34***), affective commitment (β = .26***), identification (β = .21***), and continuance commitment (β = .21**), thus supporting H10a. However, the results only provide partial support for H10b, as trust had a positive, significant, and direct effect on repurchase intentions (β = .17***) and WOM (β = .33***), but not on cooperation. These results conform to those of prior research examining trust’s influence on the components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994).

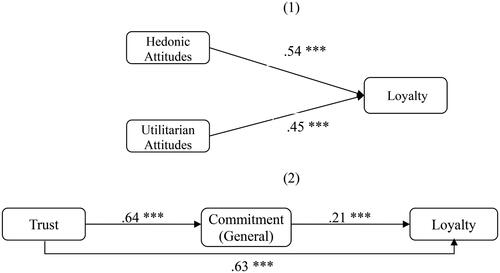

Alternative models

Model comparison is a key part of the methodology employed in this study. Therefore, to empirically confirm our model’s superior explanatory power, we tested its performance against two alternative models. The first alternative model (), which will be referred to as the “naïve” model, is aligned with the theory of reasoned action (Azjen & Fishbein, Citation1980), and is based on the common notion that a direct relationship exists between consumer attitudes and loyalty. From an operationalization point of view, the naïve model is based on the marketing literature that conceives of loyalty as a unidimensional construct (Zeithaml et al., Citation1996). However, this model has two key limitations: first, it does not clarify the mediation structure of the relationship between consumer attitudes and loyalty; and second, it does not account for all aspects of loyalty, which means that it is unable to explain all variation in the loyalty construct.

The second alternative model () is based on traditional theory that has been developed along the trust-commitment-loyalty linkage (Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Palmatier et al., Citation2006; Verma et al., Citation2016). This model is operationalized using Morgan and Hunt’s (1999) traditional measure of relationship commitment, which includes three items that assess a consumer’s degree of intention, effort, and commitment to maintaining the relationship. Loyalty is measured using the traditional 6-item scales (Zeithaml et al., Citation1996) that focus on word of mouth and continuity of business. The SEM results support the functional relationship in the model () and confirm the theory of trust-commitment. However, this model is limited in its ability to explain the different aspects of commitment and loyalty, and their relationship with other constructs. The fit indices for the three models were: study full model χ2 = 1829.55, df = 625, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.927, CFI = 0.966, RMSEA = 0.046 (.044 < 90% CI < .049), PCFI = 0.858, PNFI = 0.844; alternative model 1 χ2 = 1451.21, df = 102, p < .001, χ2/df = 14.23, CFI = 0.894, RMSEA = 0.121, 90% CI < .127, PCFI = 0.671, PNFI = 0.666; and alternative model 2 χ2 = 642.82, df = 62, p < .001, χ2/df = 10.37, CFI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.102, 90% CI < .123, PCFI = 0.637, PNFI = 0.632. As can be seen, the proposed full model had the highest CFI and the best relative Chi-square (χ2/df). Furthermore, alternative models were unable meet the acceptable criteria of the badness of fit indicator (i.e., their RMSEA > .1). Finally, the parsimony indices (PCFI and PNFI) of the alternative models indicated poorer parsimony than those of the full model. Taken together, these results confirm that the full model has a better fit with the data, is more parsimonious, and provides a more thorough explanation of the main constructs and their relationships.

The advantage of the proposed full model is its stronger explanatory and predictive power. Although prior research has established the importance of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes in predicting consumption behavior (Alba & Williams, Citation2013; Homer, Citation2008; Pallas et al., Citation2014; Voss et al., Citation2003), the proposed full model is able to provide a more detailed explanation of the functional linkage between hedonic and utilitarian attitudes, trust, and the components of loyalty. This explanation sheds light not only on the different mediation channels that connect attitudes to behavioral loyalty, but also on the functional relationships between the components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty.

Additional analysis

We conducted an additional multi-group analysis to enhance the depth of understanding of the attitude-loyalty relationship across different services, even though we did not have a hypothesis about it. The multiple-group analysis using SEM provided deep insights into how the model relationships differed across four major service groups - financial institutions, pharmacies (utilitarian services), restaurants/bars, and luxury hotels (hedonic services). Comparing utilitarian and hedonic contexts revealed some key differences. For utilitarian services like banks and pharmacies, utilitarian attitudes were much stronger predictors of trust (financial institution: βUA→T = .727***, pharmacy: βUA→T = .596***) compared to hedonic attitudes (financial institution: βHA→T = .159***, pharmacy: βHA→T = .189***). However, for hedonic services like restaurants (βHA→T = .325***, βUA→T = .385***) and luxury hotels (βHA→T = .429***, βUA→T = .403***), both attitude types similarly influenced trust levels. Moreover, the trust then strongly predicted both affective commitment (restaurant: βT→AC = .382***, luxury hotel: βT→AC = .251**) and continuance commitment (restaurant: βT→CC = .137 NS, luxury hotel: βT→CC = .300**) for hedonic services. But for utilitarian services, trust did not significantly impact commitment (financial institution: βT→AC = .148 NS, βT→CC = −.038 NS; pharmacy: βT→AC = .096 NS, βT→CC = .168*), calling into question whether the classic "trust-commitment" theory fully applies in utilitarian contexts. Instead, for utilitarian services, utilitarian attitudes directly drove affective commitment (pharmacy: βUA→AC = .163***, financial institution: βUA→AC = .164***).

The impact of continuance commitment on behavioral loyalty outcomes also diverged. It predicted repurchase intention for pharmacies (βCC→RI = .162**) and luxury hotels (βCC→RI = .131**), but negatively affected word-of-mouth (WOM) for most services (pharmacy: βCC→WOM = −.101**, restaurant: βCC→WOM = −.174***, luxury hotel: βCC→WOM = −.137**) except financial institutions (βCC→WOM = .44 NS). Relationship satisfaction was a key driver of WOM across most sectors (financial institution: βRS→WOM = .547***, pharmacy: βRS→WOM = .365***, restaurant: βRS→WOM = .319***) apart from luxury hotels (βRS→WOM = .086 NS). Notably, attitudes did not directly influence behavioral loyalty components in hedonic luxury hotel services. Instead, their effects were fully mediated through relational factors like trust, affective commitment (βAC→RI = .263***, βAC→CO = .171**), and identification.

Discussion and theoretical implications

Dimensions of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty

Firstly, this research extends the loyalty literature by providing deeper insight into various components of loyalty. Although loyalty has traditionally been conceptualized and measured in relation to its attitudinal and behavioral aspects (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001; Oliver, Citation1999, Citation2014), this study demonstrates that this approach is not sufficient. As we have shown, there are four distinct aspects of attitudinal loyalty—namely, relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, affective commitment, and identification—and three distinct aspects of behavioral loyalty—namely, repurchase intentions, cooperation, and WOM—which each express separate constructs. Through empirical testing, we confirmed the importance and roles of these components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. In light of these findings, academics and managers should consider the differences and relationships between, as well as the nature of, these components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty in their research programs and business decisions.

Effect of attitudinal loyalty on behavioral loyalty

Secondly, addressing the second research question (RQ2), the results confirm the proposed model’s ability to explain the relationship between the components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. Although our findings generally conform to those of prior research on the predictive effects of attitudinal loyalty on behavioral loyalty (Watson et al., Citation2015; Zietsman et al., Citation2023), they contribute by adding nuance and detail to the existing understanding of this relationship. Our results affirm that relationship satisfaction is the main predictor of repurchase intentions and WOM. In addition, while prior research has shown that satisfaction positively influences behavioral loyalty (Chatzi et al., Citation2024; Dick & Basu, Citation1994; Pallas et al., Citation2014; Zietsman et al., Citation2023) our findings show that it does not have the same effect on cooperation. Thus, it can be inferred that consumers who are highly satisfied in their relationship with a service provider will not cooperate in producing and delivering that service. Furthermore, continuance commitment significantly affected all components of behavioral loyalty. Moreover, identification only predicted repurchase intentions. Finally, cooperation is mainly predicted by relationship satisfaction, identification, and continuance commitment, but not by affective commitment.

Channels of influence from attitudes to behavioral loyalty

The third contribution made by this research is its empirical analysis of the ways in which hedonic and utilitarian attitudes impact attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. In embracing the theory of reasoned action (Azjen & Fishbein, Citation1980), this study was able to explain the neglected attitudes-loyalty relationship by implementing a two-factor conception of attitudes, which was adapted from relationship marketing models in the consumer behavior literature. Although Oliver (Citation1999) argued for the centrality of consumer attitudes in his classic model of loyalty, the attitudes-loyalty relationship requires more nuance and empirical testing to resolve the inconsistencies and shortcomings that are endemic to existing theories. Furthermore, Homer (Citation2008) shows that consumer attitude formation is more complex than proposed in prior literature. Thus, this research is an endeavor to apply Homer’s explanation of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes to the loyalty formation process.

Our findings show that utilitarian attitudes may not be adequate for maintaining long-term relationships because alternative service brands may poach utilitarian-loyal consumers by implementing marketing utilitarian initiatives and/or overcoming switching cost barriers. In this case, emotional attachment and affective relationship channels do prevent loyal customers from switching to other companies. Thus, stimulating hedonic attitudes is another useful strategy for developing and maintaining long-term relationships. In particular, hedonic attitudes are especially salient in predicting the components of attitudinal loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, Citation2001). Indeed, our findings confirm that the direct effects of hedonic attitudes on components of attitudinal loyalty are stronger than those of either utilitarian attitudes or trust. Given these results, service companies should strive to keep consumers emotionally engaged.

Moreover, the findings of this research show that the direct effect of hedonic and utilitarian attitudes on behavioral loyalty is neither strong nor significant. This result serves as evidence of an indirect effect through a mediation structure. One interesting insight from the attitude-loyalty analysis was that the two types of attitudes differently affect not only components of behavioral loyalty but also relational marketing mediators, including trust and components of attitudinal loyalty. This result confirms the existence of different channels of mediation, which vary in terms of strength and nature with respect to affective-cognitive linkages. Altogether, the proposed model introduces 90 possible channels connecting attitudes to the components of behavioral loyalty. In the following sub-sections, we discuss several important channels of influence based on the research findings.

Hedonic attitudes-utilitarian attitudes-trust

Our findings indicate that, in addition to a direct effect of hedonic attitudes on trust, a strong indirect effect exists as mediated by utilitarian attitudes. It is commonly believed that improving the functional aspects of a service—for example, service quality, performance, or rates/price—is an excellent way to enhance utilitarian attitudes, trust, and, consequently, long-term relationships. However, our findings indicate that it is just as important for companies to increase favorable affective (hedonic) attitudes among consumers, which is consistent with the theory of “affect-as-information” (Pham, Citation2004; Schwarz, Citation2011). A recent study by Akhgari et al. (Citation2018) shows that hedonic attitudes are not directly important antecedents of trust; rather, they indirectly affect trust and loyalty through their effect on utilitarian attitudes (Akhgari et al., Citation2018; Ball et al., Citation2004; Garbarino & Johnson, Citation1999; Schwarz, Citation2011).

Attitudes-identification-cooperation/WOM

Although prior studies have suggested the existence of an attitudes-identification-cooperation/WOM channel of influence (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Tuškej et al., Citation2013; Wu & Tsai, Citation2007), our findings show that the effect of identification on WOM is non-significant. This result may be due to the tendency of consumers to avoid talking about or advocating for a company that they highly identify with; instead, they try to protect their identity through positive cooperation with the service provider (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Wu & Tsai, Citation2007). Furthermore, the results of our empirical analysis emphasize the important role of identification in improving cooperation within service contexts. Cooperative consumers provide valuable information for a service company, which can then be used to enhance service creation and delivery. For instance, restaurants/bars may obtain new recipes from cooperative consumers, financial institutions may use valuable information about their customers’ financial status in their critical decision making, and luxury hotels may use valuable information about the preferences of their loyal consumers to improve the customer relationship management (CRM) systems.

In addition, our findings show that, compared to utilitarian attitudes, hedonic attitudes have a direct, strong (in terms of their beta coefficient), and significant effect on identification, which in turn has a significant effect on cooperation across all of the service contexts addressed in this study. This means that efforts to enhance affective (hedonic) attitudes can play an important role in improving consumer-company identification and, consequently, cooperation for creating and delivering a service (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Oliver, Citation1999; Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2010).

Utilitarian attitudes-trust-relationship satisfaction-WOM

This channel of influence is important for creating positive WOM, as our findings revealed that WOM is mainly predicted by relationship satisfaction and trust. To our knowledge, there is a lack of empirical testing with respect to the trust-relationship satisfaction-WOM relationship, though some studies have evaluated the satisfaction-WOM relationship (e.g., Pallas et al., Citation2014; Sakiyama et al., Citation2023). Relationship satisfaction’s role as a partial mediator in the trust-WOM relationship is noteworthy, as it indicates that consumers who advocate for a company (i.e., WOM) implicitly trust the company, which, as discussed earlier, is predicated on the existence of favorable attitudes.

Functions of the key mediators (trust and commitment)

The fourth contribution of this research addresses RQ4. Our results affirm that trust is the most important bridge between consumer perceptions (i.e., favorable attitudes) and intentions/actions (attitudinal and behavioral loyalty components). The study extends relationship marketing theories by introducing a robust mediation structure in the trust-loyalty relationship. Unlike the traditional trust-commitment mediation approach (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Wong, Citation2023), the proposed model demonstrates that commitment alone is insufficient to explain the trust-loyalty relationship. Instead, multiple mediators (identification, relationship satisfaction, continuance commitment, and affective commitment) collectively shape attitudinal loyalty, which then influences behavioral loyalty. Moreover, this model accounts for the role of identification, which was a shortcoming of Oliver’s (Citation1999, 2010) conceptualization of loyalty. Furthermore, this research established and tested the role of relationship satisfaction and identification in relationship marketing linkages. This mediation structure offers a more nuanced explanation of the relationship exchange process. Finally, the research clarifies the distinct roles of commitment factors as facets of attitudinal loyalty that predict, but are not part of, behavioral loyalty. It addresses conceptual overlaps in prior literature by precisely conceptualizing and operationalizing commitment, trust, and loyalty as distinct constructs within an integrated model, empirically validated against alternative models.

Negative relationships

Fifth, the emergence of negative relationships in the study results contributes significantly to theoretical insights. Continuance commitment has a considerable negative effect on WOM. This result likely stems from the feeling expressed by consumers of being trapped in the relationship (Fullerton, Citation2003; Harrison-Walker, Citation2001). Moreover, the findings confirm that relationship satisfaction negatively affects cooperation. Higher relationship satisfaction leading to reduced consumer cooperation may stem from consumers’ heightened confidence in the service received, diminishing their perceived need to cooperate for service enhancements. This aligns with existing research indicating that satisfaction negatively affects consumer participation (Bettencourt, Citation1997). Furthermore, our results revealed a negative relationship between identification and repurchase intentions. This finding, which may be explained by the existence of specific moderators, such as identity embeddedness and identity salience (Bhattacharya & Sen, Citation2003; Wu & Tsai, Citation2007), calls for additional research to determine their significance.

Variations across different service contexts

Finally, the multiple-group analysis uncovered intriguing differences in how the attitudes-loyalty mechanism operates across service contexts. The trust-commitment theory aligns well with hedonic services, where trust strongly predicts commitment. However, its applicability to utilitarian services is questionable, as utilitarian attitudes, not trust, drove affective commitment. Continuance commitment’s varying effects on outcomes, such as repurchasing and recommendations, also signify differences in the nature of consumer-firm relationships across services. Critically, for hedonic services, attitudes did not directly impact behavioral loyalty; instead, effects were fully transmitted through relational mediators. This highlights the pivotal role of fostering strong customer relationships to drive loyalty in hedonic, experiential service industries.

Managerial implications

From a managerial point of view, it would be highly useful for companies to know the significant predictors of each component of behavioral loyalty, as it would allow managers to efficiently allocate budgetary resources to improve consumer behavioral response. For instance, the results of this research indicate that continuance commitment and identification are important direct predictors of cooperation. As an empirical example, financial service companies would do well to work to strengthen identification and continuance commitment among their clients, as this would increase their levels of cooperation, which is important because financial companies need their client’s cooperation (e.g., sharing updated personal information and income profiles). One strategy to improve identification is the creation of brand communities, which serve to make consumers feel they are a part of the service brand family. In addition, to increase continuance commitment, financial companies can create impediments to switching to other service providers, such as penalties for withdrawing from mortgage contracts.

In addition, since hedonic attitudes mainly predict identification, and consequently cooperation, services for which cooperation is an important behavioral aspect of loyalty should strive to enhance the experiential aspects of their offerings, such as pleasure, delight, excitement, and enjoyment. For example, loyalty programs are one way that luxury hotels might enhance their patrons’ experiences, as such programs may reward members with exclusive entertainment and food offerings. Such programs consolidate hedonic attitudes by making members feel that they are well-treated guests, which in turn makes them more likely to cooperate, for example, by providing valuable feedback that can be used to improve the hotel’s service offerings.

A second interesting managerial implication of this research is that it demonstrates how companies that exclusively rely on the repurchasing aspects of loyalty must also account for the importance of positive WOM and cooperation. For instance, imagine a local Asian restaurant that has little competition in the area, and that relies heavily on building consumer repurchase intentions. This restaurant may experience economic losses due to not promoting positive conversations (i.e., WOM) about itself on social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Tripadvisor, which may also negatively affect its ratings. Moreover, this restaurant may neglect cooperation and fail to implement customer feedback.

With regards to building a positive WOM, managers should be careful about relying exclusively on continuance commitment due to its detrimental effect on consumer advocacy (WOM). Instead, companies should focus on enhancing continuance commitment that is based on consumers’ genuine desire to more closely identify with them, and not on a lack of alternatives or high switching costs. This source of continuance commitment reduces the likelihood of negative WOM, and may even result in consumers advocating in favor of the company in question (Hennig-Thurau et al., Citation2002).

The third managerial implication is that this study provides a better understanding of hedonic and utilitarian predictors and the different channels of loyalty formation for managers who are seeking to increase the cost effectiveness of customer-firm relationship management. Specifically, the results of this research will enable managers to choose the most effective and suitable relational channel for each target market, such as using hedonic channels when consumers are more sensitive to hedonic predictors, or using utilitarian channels when consumers are more sensitive to utilitarian predictors. For example, RBC has attitudinally loyal customers because its identity speaks to its customers’ desire for safety, security, and stability. In addition, RBC also has behaviorally loyal customers because it offer competitive rates and ancillary services that enhance the economic value received by its customers. This work pinpoints specific attitudes that impact specific types of loyalty, as well as trust.

The forth benefit for managers is that this research provides an understanding of the direct and strong effect of attitudes on relationship satisfaction. This finding implies that a first step in developing consumer relationships is to create positive hedonic and utilitarian attitudes. For example, a consumer who has an unfavorable attitude toward Delta hotels is unlikely to be satisfied with the relationship, even if they have a favorable transactional experience. This example demonstrates relationship satisfaction and its antecedents differ in nature from transactional satisfaction. While good service is a strong predictor of transactional satisfaction, other important predictors of relationship satisfaction include favorable hedonic and utilitarian attitudes, which stem from both attribute and non-attribute aspects of a service (see Homer, Citation2008).

Finally, the multiple-group analysis findings suggest fundamental discrepancies in how attitudes influence loyalty for hedonic versus utilitarian services, necessitating context-specific relationship management strategies across diverse service sectors for optimal outcomes. For instance, while nurturing trust and commitment is crucial for loyalty in hedonic service industries, utilitarian service providers may need to focus more on shaping favorable utilitarian attitudes to drive affective commitment and loyalty directly. Managers in hedonic services, like luxury hotels, should focus on affective commitment to inspire behavioral loyalty while also boosting word-of-mouth through strategic investments in key predictors that drive trust and hedonic attitudes. Furthermore, continuance commitment’s differential impacts imply that strategies to enhance switching costs or dependence may promote repurchasing for some services but backfire for others by negatively affecting word-of-mouth. Therefore, tailoring loyalty programs and relationship management tactics to the specific service context is vital for maximizing their effectiveness.

Conclusion, limitations, and future research

This study sheds more light on how attitudes (hedonic and utilitarian) affect the components of loyalty (attitudinal and behavioral) through different channels, with trust serving as a key mediator. Furthermore, this research also investigated the different components of attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, and their relationships to one another. Findings demonstrate several channels of influence from attitudes to loyalty. These channels help to understand mediation mechanism and the positioning of key relational mediators such as trust and commitment specially in service marketing context. Furthermore, managers can identify important predicting factors and channels of service behavioral loyalty, thus enabling them to optimize the costs of customer-service relationship management.

This research has several limitations that can motivate future research. The first limitation relates to the generalizability of findings, which are restricted to four service contexts. Based on the results of our pretests and the pilot study, we selected services with varying degrees of hedonic and utilitarian characteristics, as this enabled us to test our model across different types of service contexts. Although this approach improved the external validity of the results, it is possible that our findings may be service-context-specific. Thus, future research could test different types of services to determine whether our results are transferrable to other contexts.

A second limitation is one commonly encountered when working with cross-sectional data that provides a snapshot of a single point of time. While this approach to data gathering is the most commonly used method in relationship marketing due to its low cost and ease of access, cross-sectional data cannot be used to establish causality. Our model is underpinned by strong theories that support the testing of casual relationships; however, the best method for investigating causality is the use of longitudinal data, which is costly in terms of both time and money. Unfortunately, the time and money required to acquire such longitudinal data were beyond the scope and capabilities of this research.