Abstract

Introduction: Previous research shows a dearth of literature relating to the therapeutic experiences of the consensually non-monogamous (CNM) population. Research Question and Aims: We aim to understand the experiences of CNM clients in mental healthcare with a view to improving services. Method: This is an online, questionnaire-based qualitative study. Participants (n = 19) were CNM individuals who had accessed mental healthcare in the UK and disclosed being a part of CNM to their practitioner. They were recruited through social media and internet forums. Some ethical considerations included the vulnerability of this population and concerns over anonymity. Thematic analysis of the data was conducted. Findings: Three main themes were identified, these were ‘stigma’, ‘pathologisation’ and ‘barriers to openness within the therapeutic alliance’. Conclusion: It is theorized that societal mononormativity impacts both clients and practitioners within mental healthcare. For clients this compounds minority stress and results in experiences of fear of disclosure in anticipation of stigma. For practitioners, this mononormativity manifests in stigmatizing assumptions and the pathologisation of CNM in clients. Taken together, this culminates in a lack of openness and damage to the therapeutic alliance. This means care is ineffective and potentially harmful. Ways of mitigating this, including education and the development of meta skills, are explored.

Introduction

What is CNM?

Consensual non-monogamy (CNM) is a relationship orientation encompassing additional emotional connections beyond the dyad, including both sexual and non-sexual, romantic and non-romantic, as well as platonic and non-platonic relationships, all of which are negotiated agreed upon by all parties involved. (Schechinger et al., Citation2018). Some of the main types of CNM are: polyamory, multiple consensual simultaneous relationships; swinging, when couples engage in consensual sexual activity with other individuals or couples; open relationships, when a primary couple consents to relationships outside the partnership; relationship anarchy, a prioritization of individual connections over predefined relationship labels; solo polyamory, individuals engaged in multiple relationships without necessarily pursuing a primary partnership; hierarchical polyamory, maintaining distinct levels of commitment within multiple relationships where usually there is a primary partner and then secondary and tertiary partners (Hardy & Easton, Citation2017). CNM was reported in around 4–5% of the US population (Conley et al., Citation2013), and by more than one in five American adults at some point in their lifetime (Haupert et al., Citation2016). Research indicates that there are also UK based people who are in CNM relationships, as outlined below, but there is a scarcity of specific research into the therapeutic experiences of CNM people engaged in therapy.

There is a dearth of research regarding CNM people in therapy and little in the way of guides for clinical practice within this demographic (Graham, Citation2014; Weitzman, Citation2006; Weitzman, Citation1999). There are a few North American and British publications about considerations of providing mental health support to CNM people (Finn et al., Citation2012; Moors & Schechinger, Citation2014; Zimmerman, Citation2012), but there is still a scarcity of literature that has explicit examples of work with people in CNM relationships (Moors & Schechinger, Citation2014). Much of the existing research is US-based, so this study limited recruitment to UK-based mental health support clients in order to identify and address the specific needs and areas for improvement in the availability, administration, and efficacy of mental health support services for this yet underserved slice of the population in the UK. The limited current literature guiding therapy for individuals in CNM relationships uses small samples and case studies (Bairstow, Citation2017; Girard & Brownlee, Citation2015; Weitzman, Citation2006; Weitzman, Citation1999; Zimmerman, Citation2012).

CNM relationships and individuals have been demonstrated to be non-pathological in and of themselves, with similar attachment styles (Nash et al., Citation2018), levels of psychological well-being and relationship quality (Rubel & Bogaert, Citation2015) to that of monogamous counterparts. However, CNM relationships remain stigmatized as causing negative experiences, from poor relationship quality to higher risks of contracting STIs, and the people who are in CNM relationships are often viewed as less emotionally healthy than those who are in monogamous relationships (Conley et al., Citation2013; Grunt-Mejer & Campbell, Citation2016; Moors, Citation2017; Thompson et al., Citation2018). Generally, the overall negative perceptions and ideas of people engaged in CNM is not surprising, given it breaks many Western cultural norms about romantic relationships, incurring judgements about what is and is not moral (Thompson et al., Citation2018).

A vast majority of therapists are unaware, biased, and yet ill-equipped to serve this growing population (Grunt-Mejer & Łyś, Citation2019). Interestingly, in 2018 the American Psychological Association established the first Consensual Non-Monogamy Task Force, Division 44, in order to advocate for inclusivity in the areas of basic and applied research, creation of education and training resources, psychological practice, and as a public interest initiative (Schechinger et al., Citation2018).

In the UK, the pathway to accessing mental health services often commences with individuals seeking guidance from their General Practitioner (GP), who serves as the primary entry point to the healthcare system. After an initial assessment, individuals may be referred to specialized mental health services provided by the National Health Service (NHS), such as the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program or community mental health teams. However, it’s noteworthy that due to the strain on the NHS, waitlists for these services can sometimes be notably extended. Consequently, many individuals opt for private mental health services to bypass these delays and access timely support. Following comprehensive assessments by mental health professionals, personalized treatment plans are formulated, encompassing therapeutic interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and, where needed, medication management. Throughout the treatment journey, individuals receive ongoing support and follow-up appointments to monitor their progress and adapt interventions as necessary (Chen & Cardinal, Citation2021).

Mental health professionals hold an important role in supporting their clients in the development of self-acceptance and realization of their potential, but without the appropriate training, they may hold stigmatizing attitudes based on their own biases, potentially leading to inappropriate or harmful practices within the therapeutic relationship with CNM clients. A well-equipped psychologist, therapist, or other mental health care support professional should be prepared to work carefully and without prejudice with consensually non-monogamous clients on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the individuality of each client without pathologization or stigmatization coming into play within the therapeutic experience (Herbitter et al., Citation2021). It would be most beneficial for clinicians to have a psychotherapeutic framework that enables them to have an effective, meaningful understanding of the specific perceived or real values and limitations of engaging in CNM. A phenomenological understanding of the clients’ experiences would allow therapists to understand the clients’ experiences, as they are lived and experienced by the client (Spinelli, Citation2005).

To explore further understanding of therapeutic relationships with CNM clients in the UK, this investigation undertook a qualitative study which explored what CNM therapy clients perceive within the relationship with their mental health care support providers and identified some perceived biases, unhelpful practices, and areas for improvement specifically within the service-use experiences of CNM people in the UK.

Minority Stress

The CNM experience converges with other minority experiences such as discrimination, disclosure and visibility concerns (Schechinger et al., Citation2018). As a sexual minority, experiences of the CNM community can be understood through a minority stress framework (Meyer, Citation2003) adapted from the experiences of LGBTQIA + communities. This is especially pertinent given the high levels of CNM in LGBTQIA + communities with 65% of gay men, 28% lesbians and 33% of bisexuals reporting CNM participation (Blumstein & Schwartz, Citation1983; Weitzman, Citation2006). Similarities in experiences associated with minority sexual groups, as well as the high prevalence of CNM within LGBTQIA + communities demonstrates that the use of the minority stress framework could help to illuminate how those who participate in CMN may experience broader society and set the backdrop for how this may further play out within the therapy space.

This framework explains how social stigma from norm violation, here the norm of monogamy called mononormativity (Cassidy & Wong, Citation2018), causes additional stress to accumulate (Fuzaylova et al., Citation2018) negatively impacting mental health. These processes are both internal and external. Internally, the awareness of norm violation within the individual is theorized to create inner conflict and alienation by disrupting the norm-driven process of creating a sense of self (Meyer, Citation2003; Zimmerman, Citation2012). Externally, disproportionate experiences of discrimination, rejection and victimization in society create a hostile environment for sexual minorities (Balsam et al., Citation2005; Conley et al., Citation2013; Meyer, Citation2003). This leads to increased vulnerabilities to mental health issues, mental health burdens and utilization of services (Cochran et al., Citation2003; Schechinger et al., Citation2018). For example, those who engage in CNM may experience an inner sense of ‘wrongness’ due to awareness of difference in how they carry out relationships compared to the common social script of monogamy. They may also experience rejection and discrimination from friends, family members and wider society following disclosure; or feelings of rejection and isolation from society through a lack of accurate representation within media.

While preliminary studies demonstrate stigmatizing attitudes toward CNM in the US (Hutzler et al., Citation2015; Schechinger et al., Citation2018), no studies currently identify the stigma faced by CNM individuals in the UK. Gaining insight into stigmatizing experiences will help assess the vulnerabilities to increased mental health burdens that being a part of CNM carries for UK therapeutic populations. Furthermore, understanding the experiences of CNM clients within the therapeutic space enables practitioners to identify areas in which minority stress is reinforced or can be alleviated within therapy.

Therapeutic Alliance

The therapeutic alliance, here meaning the client-practitioner relationship, is paramount in successful mental healthcare. Research suggests that a negative therapeutic alliance is linked to unsuccessful outcomes and is arguably the most important predictor of therapeutic success (Goldfried, Citation2013; Lambert & Barley, Citation2001).

A mixed methods study by Schechinger et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated that therapist-perpetuated stigma, evident in harmful attitudes, damages the therapeutic alliance and is linked to increased early termination in therapy. In their sample of 249 US CNM-identified clients, 11% of participants terminated therapy prematurely because of negative interactions with their therapist regarding CNM (Schechinger et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, 65% of clients were dissatisfied with their treatment; categorizing it as destructive (11%), unhelpful (15%) or found therapists lacking in knowledge (29%). This aggregate is higher than the 5–20% of dissatisfied clients from a general sample of 380 adult psychiatric outpatients in the US (Urquhart et al., Citation1986).

These harmful attitudes in practitioners create and perpetuate minority stress when accessing mental healthcare and are thus an area of key concern for CNM therapeutic populations. Particularly, clients perceived that therapists often viewed CNM as pathological (see also Brandon, Citation2011; Weitzman, Citation1999), suggesting that it was responsible for their presenting concern. This finding demonstrates the clear need for education and awareness of CNM for practitioners and is corroborated by smaller qualitative studies (Graham, Citation2014; Hutzler et al., Citation2015).

Knowledge and training regarding CNM are important factors in the ability for mental healthcare providers to form a strong therapeutic alliance, but a lack of research and recommendations for providers persists. A content analysis by Brewster et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated that only 2 out of 116 articles on CNM published since 1926 focus on concerns related to training and counseling. In the same study, most articles were found to focus on relationship orientations, stigma and/or LGBTQIA + concerns. While these issues are prevalent, it is vital they can be addressed in such a way that specifically aims to improve therapeutic training and counseling services with regards to the CNM community. This in turn will provide guidance for practitioners on addressing concerns regarding the therapeutic alliance, improving services for CNM clients.

Success in therapy is most likely when practitioners can understand the subjective client experience (Berry & Barker, Citation2014), but also challenge their own assumptions and monogamous bias (Hutzler et al., Citation2015; Jordan, Citation2018; Schechinger et al., Citation2018; Zimmerman, Citation2012). Ultimately our aim is to give evidence-based guidance to practitioners regarding CNM client concerns, particularly where they impact the therapeutic alliance. This study seeks to answer the following research question using a qualitative study of survey responses:

RQ: What are the experiences of mental healthcare for consensually non-monogamous clients?

What kinds of experiences do CNM individuals have in therapy?

In what ways, if at all, can we improve these experiences?

Methods

Design

This study utilizes a survey-based qualitative design. This is similar to comparable studies such as that by Fuzaylova et al. (Citation2018) and Kisler and Lock (Citation2019) which examine the CNM therapeutic experience, as well as work on therapeutic practice by Schechinger et al., Citation2018). Qualitative methods were chosen as they allow for a richer understanding of experience as well as amplifying the voices of the CNM community (Barbour, Citation2014).

Thematic analysis (TA: Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was used to analyze the data. TA is well suited to analyzing CNM experiences as it involves minimal organization but allows for rich detail. Specifically, Braun and Clarke (Citation2014) identify TA as useful for applied health research in practice arenas, suiting the overall intended outcome of this research in informing practice with CNM individuals.

Sample

Participants were 19 people who self-identified as having been ‘a part of’ CNM at some point. This definition is deliberately imprecise, as the research team wanted to be as inclusive of as many models of CNM as possible to capture a broad variety of participants. Crucially, all participants are similar in that they have disclosed a shared experience CNM to practitioners in the UK.

There was no further demographic information collected from the sample due to ethical considerations about privacy and anonymity. Specifically, over concerns that participants are known to one another due to the small population size and specificity, as well as being recruited via forums where particpants are interlinked. There was therefore concern that participants would be unwilling to complete the study if asked to share further demographic information.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were those who had at some time engaged with CNM, and who had disclosed this to a mental healthcare practitioner. Participants were also required to be over 18, fluent in English and to have received mental healthcare in the UK.

Exclusions included participants who were currently engaged with mental healthcare services. This was to reduce risk of harm during the study, due to the vulnerability of this group and risk of impacting treatment. Factors increasing vulnerability include past treatment for mental health concerns and the high likelihood of LGBTQIA + identity (noted earlier).

Procedures

Sampling and Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to reach our target demographic. This is because of the small size of our population and the highly specific nature of our sample. Participants were thus recruited via Facebook groups, our own social media and online forums (reddit). 19 of 48 respondents were viable participants and responded to all questions, most non-viable participants answered none of the questions asked so no data could be gathered. Participants could not respond to the questions without completing the screening process which outlined exclusion criteria.

Data Collection

An online survey questionnaire with open ended essay style questions was chosen as the suitable method of data collection. This method allowed us to gain access to our geographically dispersed and hard to access population.

Two of the survey questions relate to challenges faced in mental healthcare as someone who is a part of CNM as well as recommendations for practitioners (questions 1 and 4 respectively). Participants were also asked about supportive practices they’d encountered in question 2. This question aimed to provide a counterbalance to the challenges faced and alleviate any bias in questioning. Both question 2 and 4 also fit with the aim of affirmative practice which is detailed above. Question 3 asked about assumptions practitioners made about their clients. This question was asked due to literature which indicates the presence of (negative) practitioner assumptions (Baluck, Citation2020; Hymer & Rubin, Citation1982; Knapp, Citation1975). These include pathologisation and promiscuity (Baluck, Citation2020; Hymer & Rubin, Citation1982; Knapp, Citation1975), which the research team felt important to explore from a client perspective. See Appendix A for the complete list of questions.

Data Analysis

Data was analyzed using Braun and Clark’s (2006) six steps: initial codes were first noted individually to minimize bias. Data was exported from SurveyMonkey directly into a Microsoft Word document stored on a secure drive, where a table was created to allow for coding. Coding was done for as many themes as possible, using the research question as a guide. Themes were again found using the research question as a guide. Candidate themes and sub-themes were compiled into several initial mind maps and tables. Themes were reviewed in discussion with the research team. Candidate themes and codes were found to be similar with mostly structural differences in supra-ordinate and subordinate themes.

As well as integrating these differences, some themes were abandoned or reduced to sub-themes. In particular the theme of ‘fear from client’ was reduced to a sub theme of ‘potential barriers to openness in the therapeutic alliance’. This is because the researchers’ prior experience was influencing the relative importance placed on fear as opposed to its prevalence in the data set. The researchers then met again to finish the recursive process of amassing evidence from the data corpus for the themes, using both the codes and original data as guides.

A table was created of themes and a color code was employed to decide on key quotes within the data, as well as to ensure that evidence was gathered across all participants. Only responses from participant 6 were not present in the final themes, indicating a strong evidential basis for all themes. This was due to their answers not correlating with the questions asked. At the end of this stage, a satisfactory theme map of three overarching themes was agreed upon. Names were written to be descriptive and defined succinctly in relation to the research question. Themes and data extracts were written up to create the report. As per Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) wider literature was brought in to ensure a cohesive narrative.

Reflexivity Statement

The research team comprised two postgraduate students with experience working in the field of mental health along with a research supervisor. The research supervisor is a practitioner psychologist, lecturer and experienced researcher with over 25 years of experience in both clinical and academic settings; this includes publishing research with qualitative and specifically thematic analysis. It is important to note the expertise and makeup of the research team as the personal backgrounds of the researchers play a role in shaping this analysis. While a deductive approach was taken to the analysis, there were times the research team was aware of looking for specific codes in the data. In an effort to ensure that the team was conscious of their own bias, regular meetings were held to explore and discuss the issue of bias. Members of the research team had similar experiences to that of the participants and so they were intent on discussing individual interpretations as a team to help shape a more collective synthesis. As an example, as mentioned in data analysis, members of the research team had their own experiences of personal therapy, thus the collaborative work helped the team understand how their prior experiences inevitably influenced their perspectives and interpretations throughout the research process and how best to let the participants have their own voice.

Ethics

Ethical approval from the University of Edinburgh, School of Health in Social Science Ethics Committee was obtained.

Quality Control

Three types of measures were undertaken to maintain quality. In the first instance, TA was chosen as an analytic method, particularly identifying latent themes and conducting inductive analysis. The inductive or ‘bottom up’ analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) strongly links data to themes and reduces bias by relying more on participant data than personal interpretation. Here, negative cases were also noted, and self-reflexivity integrated to improve accuracy and strengthen analysis. Secondly, codes were cross checked, and themes discussed within the team. This meant that both coding and theming were subject to scrutiny for bias. Thus, codes and themes were edited, added or eliminated in accordance with this.

Member checks, aimed to increase validity by asking participants for feedback on the analysis undertaken, were unable to be carried out due to the anonymous nature of the online survey. Instead agreed themes and codes were discussed with the research team. This process allowed the researchers to confront bias and identify areas where themes were unsupported in the data, and instead identified through emotional connection. Such themes were then eliminated or reduced to subordinate themes (e.g. in the case of ‘fear from client’).

Findings

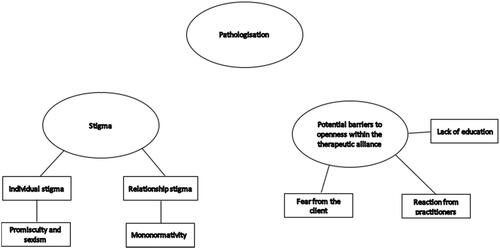

Three key themes and five sub themes were identified from the study. These have been displayed in a thematic map.

Stigma

The experience of stigmatizing assumptions was profound in the study. Of our 19 participants, 14 reported experiencing stigmatizing assumptions from their practitioner. This came to light especially when respondents were asked what kind of assumptions they thought practitioners had made about them. These responses can be subdivided into two kinds: stigma aimed at the individual and stigma aimed at CNM relationships.

Q1P18 My mental health practitioners have almost always responded with stigmatizing assumptions to me talking about my non monogamous practice.

Individual Stigma: Promiscuity and Sexism

One category of stigmatizing assumptions is those leveled against the individual. These assumptions reflected individual practitioner expectations about CNM participants. Some participants faced sexist assumptions on account of their CNM. In addition to facing assumptions that they were “sexually promiscuous”, participants also faced stigma around their choices to be a part of CNM. These choices were viewed by practitioners as less consensual or empowered on account of their sex or gender identity. As well as being inherently sexist and cisnormative, these assumptions also remove agency from the client within their relationships. An example of this is put most succinctly in the following quote:

Q3P7 “There is very much the preconceived notion that it must be the “fault” of the one in possession of a penis and that I must just be hanging on and they can’t shake me, not that I am happy to be there and am the chief architect.” Here the participant demonstrates that their practitioner has assumed that CMN is not an empowered choice of relationship model, and that as a woman this could not be their genuine preference.

Q3P9 I also felt there were sexist assumptions about differences in what men and women want that are not necessarily correct for everyone.

Relationship Stigma: Mononormativity

More broadly, many participants faced mononormative assumptions which were stigmatizing of their relationships. Mononormativity can be seen in multiple ways, through the devaluing of CNM relationships and in privileging monogamy over CNM. This comes across clearly in participants’ experiences. One participant reported that “I think he assumed non monogamy meant lack of care or commitment… Basically all the assumptions that monogamy is better, would be better for me, and must be what I really wanted deep down.”

Participants demonstrated that the treatment room is at times a microcosm for society. One participant in particular highlighted that practitioners are not free from bias and can perpetuate stigma in their interactions with CNM clients.

Q3P3 I hope they are also aware heteronormativity and mononormativity are strong forces in our society and they are not immune to them.

In terms of treatment, stigma in mental healthcare was seen as a barrier to effective treatment and caused unhelpful self-doubt in a place where participants were vulnerable.

Q2P9 This wall of assumptions, in a space where I am supposed to trust to be vulnerable and self-question, led me to doubt myself in ways that weren’t useful because they were coming from somebody else’s agenda and ideas about the world, not my own.

While participants want to be treated normally in mental healthcare, they were clear that pitting CNM against the ‘norm’ of monogamous relationships is unhelpful and unwanted.

Pathologisation

Though pathologisation can also be construed as stigmatizing, this theme was felt to be distinct due to its prominence as over half (12) of our participants experienced it directly. Participants experienced the pathologisation of CNM when practitioners reduced or mistook CNM practice as signifying mental illness. As one participant put it:

Q4P18 Sometimes, people can have mental health issues … AND be non-monogamous, and the two things can be completely unrelated.

Potential Barriers to Openness within the Therapeutic Alliance

This theme describes experiences participants had which impacted on their ability to be open with their mental healthcare practitioners. The therapeutic alliance can be understood as the relationship between the practitioner and client. This theme was identified in 15 participants, making it the most prevalent finding across participants. These experiences have been categorized into three barriers: ‘Fear from the client’, ‘Reactions from the practitioner’ and ‘Lack of education’. These represent the dual origin of barriers, coming from both the client and practitioner within the therapeutic alliance. Participants felt that this lack of openness meant practitioners had an insufficient understanding of their lives, and this impeded their healthcare.

Q4P12 practitioners should be aware how reluctant we are to divulge this, and if we don’t they’re not getting a good picture of our lives.

The Participant Highlights the Importance’s Life

Fear from the Client

Clients reported that they began mental healthcare with preconceived ideas of the kinds of assumptions therapists would make. This led to fear of being open and its consequences. Participants indicated that they were fearful of pathologisation and faced challenges around “fear, probably unfounded, of not being understood or of the therapist believing CNM is the root of all things happening in my life.”

Furthermore, they worried particularly about the possible religious and moral judgements they might face on account of CNM, particularly when “…you’re … aware that there are so many people out there with monastic moralistic views that you can’t be open.” This idea was mirrored in another participant’s response that they struggled with “fear. Fear of how they will react, judgemental, biblical, flipping out.” Further legal consequences, such as children being removed, was also noted by one participant. Participants thus demonstrated worry about the consequences of disclosing their CNM in mental healthcare, even when this was not born out in their experiences following disclosure. This led to self-censorship and an inability to be open about their lives.

Reactions from Practitioners

As well as feared reactions, participants faced potential barriers to openness from the reality of practitioners’ reactions to CNM in treatment. Above, it was noted that experiences of pathologisation and stigmatizing assumptions occurred. However, this sub-theme addresses the potential barriers faced by the ways in which practitioners conveyed themselves.

Clients asked that their practitioners “be familiar with different approaches and relationship models/philosophies… and do not react shocked/horrified/baffled.”

Some participants experienced shock and surprise from their practitioners over their ‘normality’. This is evidenced in particular, with one participant stating that practitioners “might be surprised because I "seem normal". However, others experienced avoidance from their practitioner. Participants noted that practitioners “aren’t comfortable to discuss the subject” of CNM. This was evidenced by “silence and moving on” when the subject is raised. The following quote puts this clearly:

Q1P5 Councillor (sic) did not really address the issue or mention it in context to the therapy.

Lack of Education

Participants experienced a profound lack of education on CNM in their practitioners while receiving mental healthcare. More education was a key way that clients felt they could be more supported, and that this would contribute to further openness in the therapeutic alliance.

Q4P4 I definitely think that therapists need to study this more and understand … [CNM is] not accepted in society yet, [there] are very few people that are open about it.

A lack of education was evident in client experience. Firstly, in “having to explain or justify my non-monogamy to the health care professional.” Furthermore, participants had practitioners who were inexperienced with CNM.

Q1P15 The therapist admitting having no experience in handling relationships that might have more than 2 people involved.

It was reported that encountering a lack of education led to excessive time spent educating their practitioners as opposed to engaging with their presenting concern and consequent treatment. This was demonstrated in the following recommendation: “Maybe also to have at least a basic understanding of CNM, to reduce the amount of time necessary for patients to explain from the ground up.” This lack of understanding had a negative impact on the therapeutic alliance as clients cannot be open without first educating their practitioners.

Furthermore, a lack of education impacted client support. One participant stated that they felt supported “when my own feelings about a situation are truly heard.” Crucially this “is impeded when the practitioner lacks understanding about non monogamy and makes judgements based on assumptions.” This demonstrates the impact of education on openness in the therapeutic alliance, as clients feel they cannot be heard and adequately supported when practitioners are uneducated.

Discussion

Findings in Context

This study explored CNM people’s perceptions of the quality and preparedness of mental health professionals’ skills when working with CNM people. The data collected indicates that there is a tremendous opportunity for education and training materials to be developed, as unhelpful experiences were commonly reported. As expected, CNM clients reported dissatisfaction and discouraging experiences when seeking and utilizing mental health support services and many (53%) highlighted the need for exposure and education for therapists to be better able to support CNM clients.

Clinical Implications for Stigma in CNM Clients

As highlighted in the introduction, CNM clients can be understood within a minority stress framework (Meyer, Citation2003). This framework explains how social stigma from norm violation, here the norm of monogamy (Cassidy & Wong, Citation2018), causes additional stress to accumulate (Fuzaylova et al., Citation2018), negatively impacting mental health. This leads to increased vulnerabilities to mental health issues, mental health burdens and utilization of services (Cochran et al., Citation2003; Schechinger et al., Citation2018). Thus, prior to entering treatment, CNM clients already experience complex added stress compared to monogamous counterparts, regardless of presenting concerns.

Practitioners should be aware that this stress is a potential feature of their client’s lives, regardless of presenting concerns which may or may not be CNM related (Davidson, Citation2002; Girard & Brownlee, Citation2015). The added fear and stress that may be experienced within the therapeutic relationship has the potential to impact openness and honesty within the therapeutic relationship. Generally, CNM therapy clients found it helpful when their therapist took an affirming and nonjudgmental stance toward CNM and was either educated or willing to learn about CNM. Sadly, this was the minority experience, with most clients reporting that their therapist either avoided the topic or expressed a lack of knowledge or held a judgemental, pathologizing, or dismissive attitude toward the clients’ CNM.

Importantly, client fear of stigma was identified as a barrier to openness in mental healthcare. Within a minority stress framework, both external experiences of stigma and internal awareness of norm violation are theorized to increase feelings of fear within clients even before entering treatment and induce hesitancy within the therapeutic relationship. Similar findings were identified by Fuzaylova et al. (Citation2018) within disclosure. It is not only a fear of judgment that impacts CNM clients, but also of the reaction from the therapist and potential legal consequences.

In particular, one participant noted that worry over having her children removed caused great fear and caused her to be less open about her CNM. We would thus advise that steps are taken to alleviate client fears and include relationship information on intake forms as well as a statement that the practitioner is CNM-friendly. The latter is a direct recommendation by the participant in question. Asking clients to disclose relationship structure on intake forms is also theorized to have other benefits (Schechinger et al., Citation2018). These include the promotion of in-session disclosure, validating clients’ experience and finally allowing the gathering of data on quality of care for CNM clients, which is recommended by Sparks et al. (Citation2011).

Within ‘stigma’ the research highlights sexist assumptions made by practitioners with regards to CNM. The intersection between CNM and gender identity appears to demonstrate increased risks of oppression and marginalization for CNM clients who are women. Given the evidence of fear, practitioners should be aware that fear in CNM clients who are women is more likely given that stigma is often tied to gender-related judgements (Klesse, Citation2011). Particularly judgements of promiscuity, which tie into negative associations of women’s perceived purity and morality (LeMoncheck, Citation1997; Wolf, Citation1997). We recommend that special attention is paid to this sub-group.

The privileged access that practitioners have to clients in vulnerable moments, which was noted by a participant within ‘stigma’, means close attention must be paid to minority stress. This is because research suggests that being emotionally close to a person, as one is in mental healthcare, can cause feelings of rejection to be the most painful (Kross et al., Citation2011; Schechinger et al., Citation2018), amplifying concerns over the potentially negative consequences of disclosure.

Implications of Mononormativity in Practitioners

Though anti-CNM bias and stigma in practitioners has been a consistent research finding (Hutzler et al., Citation2015), studies on the attitudes of mental health practitioners toward CNM are scarce, with only three studies identified at the time of writing. Two of these surveys, undertaken by Knapp (Citation1975) and Hymer and Rubin (Citation1982) are over 30 years old. Both demonstrate predominantly negative attitudes toward CNM, with swinging perceived as pathological in both studies. A further study, conducted by Baluck (Citation2020) in the US, provides an up-to-date analysis of 127 recent graduate attitudes toward CNM, with similar conclusions.

The implications of stigmatizing and mononormative assumptions from practitioners are seen keenly within the pathologisation of CNM. Deeply embedded assumptions that privilege monogamy cause the belief that monogamy is the only healthy relationship orientation, therefore pathologizing CNM (Henrich & Trawinski, 2016; Knapp, Citation1975). It has been recommended by several researchers that practitioners are careful not to pathologise CNM (Henrich & Trawinski, Citation2016; Kisler & Lock, Citation2019; Schechinger et al., Citation2018), a recommendation emphasized by the high levels of pathologisation in our findings. As many CNM clients seek treatment for similar reasons as monogamous clients, (Girard & Brownlee, Citation2015) CNM must not be assumed to be a presenting concern (Davidson, Citation2002; Henrich & Trawinski, Citation2016). Pathologisation was found to be an unhelpful practice by Schechinger et al., Citation2018), negatively impacting treatment outcomes (Schechinger et al., Citation2018) and reinforcing mononormative stigma in assessment and treatment (Weitzman, Citation1999) and is theorized to perpetuate minority stress.

Some nuance is required however, as there was an interesting dichotomy of responses regarding discussion of CMN in the therapeutic space. While participants were clear that pathologisation was not desired, one participant perceived the lack of discussion of CNM as avoidance. It may be beneficial for practitioners not to avoid discussion of CNM and how it impacts the client through fear of pathologisation.

Alongside assumptions themselves, we also found the way assumptions were conveyed in practitioners’ emotional reactions as a key experience in CNM client’s mental healthcare. Negative reactions are corroborated in multiple studies (Fuzaylova et al., Citation2018; Henrich & Trawinski, Citation2016; Schechinger et al., Citation2018). Clients were likely to select therapists based on their reactions to CNM disclosure (Fuzaylova et al., Citation2018) and terminate the relationship in response to negative reactions (Fuzaylova et al., Citation2018; Schechinger et al., Citation2018). This demonstrates a breakdown in the therapeutic alliance.

Therapeutic Alliance

Generally, CNM clients found it helpful when their therapist took an affirming and nonjudgmental stance toward CNM and was either educated or willing to learn about CNM. Sadly, this was the minority experience, with most clients reporting that their therapist either avoided the topic or expressed a lack of knowledge or held a judgemental, pathologizing, or dismissive attitude toward the clients’ CNM.

Subjecting clients to stigma and discrimination based on CNM damages the therapeutic relationship and jeopardizes its longevity, which is known to correlate with poor mental health outcomes (Martin et al., Citation2000).

The therapeutic alliance, as previously noted, is of paramount importance to the success of mental healthcare (Goldfried, Citation2013; Lambert & Barley, Citation2001). And, given minority stress in CNM clients, is particularly important for this population.

Razzaque et al. (Citation2015) found that increased openness to experiences and nonjudgmental acceptance were significant indicators in practitioners of the strength of the therapeutic alliance. Negative emotional reactions, recorded in our study, demonstrate judgment and a lack of openness in clients. In particular, this increased clients’ feelings of shame and distress (Henrich & Trawinski, Citation2016), perpetuating minority stress. Thus, a lack of openness is hypothesized to damage the therapeutic alliance.

One novel finding within ‘reactions from practitioners’ was avoidance and discomfort over the topic of CNM. This alienated clients and impacted on openness within the therapeutic alliance. This finding could be due a lack of screening in UK clients, who are given less control over mental healthcare providers within the NHS. This may impact on their ability to find practitioners who are culturally competent and thus result in an increase in the variety of negative reactions recorded.

Practitioner stigma also damages the therapeutic alliance and results in early termination of therapy (Schechinger et al., Citation2018), both of which are correlated significantly with poor mental health outcomes (Martin et al., Citation2000). In line with a study by Sullivan et al. (Citation2017) on therapist attitudes toward polyamory, Baluck (Citation2020) found that knowledge of CNM was positively correlated with positive attitudes. Thus, increased education and awareness of CNM should be a key focus for improvement of services.

Education

The data collected indicates that there is a tremendous opportunity for education and training materials to be developed. The most commonly reported experience in therapy for CNM clients, the lack of education, is an indicator of generally unhelpful and potentially harmful therapeutic practice and experiences. The inclusion of CNM orientations and variations thereof, terminology, and dynamics in continuing education and training for therapists would serve to increase awareness, identify inherent biases and provide helpful information necessary in supporting CNM clients. This would decrease the discomfort and increase the efficacy of therapy for this population. In particular, our participants wished their therapists understood both basic concepts as well as the breadth of ways CNM can be manifested. There lacked a strong positive response to Q2 regarding what was particularly helpful or effective, as participants expressed mostly perceived shortcomings in their reports of their experiences in therapy. Other notable findings included the suggestion that therapists broaden their understanding of how concepts such as jealousy, cheating, and compersion differ from common understandings in monogamy, as was recommended by one participant. Compersion is a term used in CNM to describe positive and empathic feelings that some individuals may experience when their partner(s) engage in platonic or romantic connections with others. It is essentially the opposite of jealousy - instead of feeling threatened or envious, a person experiencing compersion feels joy, happiness, and/or satisfaction for their partner’s enjoyment and connection with others (Jordan, Citation2018). Increased knowledge of CNM may also serve clients who are struggling to find CNM resources (Bairstow, Citation2017).

While this should reduce some stigmatizing assumptions, practitioners should take steps to address their judgment and also model openness within mental healthcare dynamics. The dichotomy between pathologisation and avoidant reactions bares exploration, particpants both evidenced a desire for their therapists to be comfortable discussing CNM aspects of their lives whilst not unnecessarily bringing in CNM as inherently pathological. It could be theorized that a lack of education in practitioners may be causing them to avoid discussion of the topic due to feeling ill equipped, it may also underpin stigmatizing and false assumptions about CNM as inherently pathological. It is possible also that minority stress, particularly an internal awareness of norm-violation in clients may impact the way in which lack of acknowledgement of CNM is perceived (as avoidance rather than acceptance) in the therapeutic space. It is important, therefore, that practitioners are aware of their reactions to CNM and how these are interpreted by clients. The respondents in the present study whose therapists were willing to listen and educate themselves about CNM found this helped them to become comfortable and feel heard when talking about their personal lives. Therapists would also then be able to help current CNM clients to process prior negative therapy experiences.

In light of the high incidence of fear faced by CNM clients surrounding the safety of their children and other critical family-wellbeing issues, it is imperative to consider the inclusion of relationship structure in the demographic section of mental health service intake forms. This would also increase the visibility of CNM populations. One way that accessibility might be improved would be for therapists who are knowledgeable and affirming of CNM to indicate that CNM clients are a population in which they specialize when listing their practices on therapist locator websites.

Future Research

Given the findings of the study, there are several avenues of further exploration available. Replication with high powered longitudinal designs on active treatment would more robustly confirm findings and inform care. Wider varieties of data collection, such as semi-structured interviews, would also be beneficial. Furthermore, studies should expand in their diversity and specificity.

Additionally, future research might gather more specific data on demographics, such as marital status, nationality, and race, as well as specific type of CNM, from survey participants would offer valuable insights into the diverse characteristics and preferences within the CNM community. Addressing these unknowns would deepen understanding of the nuanced needs and experiences of this population. To protect participant identities, researchers could employ methods such as aggregating data to ensure anonymity in reporting and utilizing broader demographic categories while focusing on relevant CNM-specific variables.

With the aforementioned dearth in CNM literature generally, and particularly within the UK specifically (only Finn et al., Citation2012 exists currently), further UK-based studies would serve to confirm our findings.

Limitations

The study design constrains the generalizability of this research. As we only accessed a small sample and have a lack of demographic information regarding gender, race and type of mental health care accessed, so generalization should be minimal. In addition to this, there is a need within research to hear and understand a wide variety of diverse voices. The lack of demographic data limits a contextual understanding of the findings, obscuring whether research represents marginalized or privileged voices within the CNM community. Further collection of demographic data would have served to contextualize the study and provide clarity on the diversity of the sample. This study provides important exploratory work into the direct experiences of CNM clients in the UK, which until now was unaddressed in the literature. It identifies key themes such as openness in the therapeutic alliance and demonstrates a clear need for education and tackling stigma when treating this population.

Conclusion

Given that this study is the first to look directly at clinical CNM populations, it has important ramifications for mental healthcare. It has brought to attention one unexplored area and several lesser explored areas in CNM research generally, including the importance and impact of mononormativity on openness within the therapeutic alliance and the intersectionality of gender identity and CNM stigma. By amplifying the voices of those who are a part of CNM in mental healthcare, it shows the clear need for education in training and self-assessment of stigma within practitioners.

As awareness is raised about these different relationship orientations, there will hopefully be more inclusivity and understanding in the therapeutic field and in health care organizations and governing bodies about CNM as a legitimate relationship orientation that autonomous adults can choose.

Ethical Approval

Research did involve human participants, all of whom have given their informed consent and all ethical procedures were followed under the guidance and approval of the University of Edinburgh Ethics Committee.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article, therefore the authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Bairstow, A. (2017). Couples exploring nonmonogamy: Guidelines for therapists. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1164782

- Balsam, K. F., Rothblum, E. D., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2005). Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.73.3.477

- Baluck, T. (2020). [Assessing therapists’ attitudes toward consensually non-monogamous clients]. [Doctoral dissertation, Eastern Michigan University]. https://commons.emich.edu/theses/1025

- Barbour, R. (2014). Introducing qualitative research: A student’s guide. (2nd ed). SAGE publications.

- Berry, M. D., & Barker, M. (2014). Extraordinary interventions for extraordinary clients: Existential sex therapy and open non-monogamy. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2013.866642

- Blumstein, P., & Schwartz, P. (1983). American couples: Money, work, sex. William Morrow.

- Brandon, M. (2011). The challenge of monogamy: Bringing it out of the closet and into the treatment room. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2011.574114

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Brewster, M. E., Soderstrom, B., Esposito, J., Breslow, A., Sawyer, J., Geiger, E., Morshedian, N., Arango, S., Caso, T., Foster, A., Sandil, R., & Cheng, J. (2017). A content analysis of scholarship on consensual nonmonogamies: Methodological roadmaps, current themes, and directions for future research. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 6(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000074

- Cassidy, T., & Wong, G. (2018). Consensually nonmonogamous clients and the impact of mononormativity in therapy/Les clients non monogames consensuels et l’impact de la mononormativite en therapie. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 52(2), 119–139. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/article/view/61124

- Chen, S., & Cardinal, R. N. (2021). Accessibility and efficiency of mental health services, United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(9), 674–679. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.273383

- Cochran, S. D., Sullivan, J. G., & Mays, V. M. (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.71.1.53

- Conley, T. D., Moors, A. C., Matsick, J. L., & Ziegler, A. (2013). The fewer the merrier? Assessing stigma surrounding consensually non-monogamous romantic relationships. Deep Blue (University of Michigan). http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/102091

- Davidson, J., 5. (2002). Working with polyamorous clients in the clinical setting. Electronic Journal of Human Sexuality, 5(8), 465.

- Finn, M. D., Tunariu, A. D., & Lee, K. C. (2012). A critical analysis of affirmative therapeutic engagements with consensual non-monogamy. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 27(3), 205–216. K. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2012.702893

- Fuzaylova, V., Borden, K., Hammer, D., & Whitaker, C. (2018). Nonmonogamous clients’ experiences of identity disclosure in therapy, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses 413. https://aura.antioch.edu.etds.413

- Girard, A., & Brownlee, A. (2015). Assessment guidelines and clinical implications for therapists working with couples in sexually open marriages. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2015.1028352

- Goldfried, M. R. (2013). What should we expect from psychotherapy? Clinical Psychology Review, 33(7), 862–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.003

- Graham, N. (2014). Polyamory: A call for increased mental health professional awareness. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(6), 1031–1034. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0321-3

- Grunt-Mejer, K., & Campbell, C. (2016). Around consensual nonmonogamies: Assessing attitudes toward nonexclusive relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(1), 45–53. 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1010193.

- Grunt-Mejer, K., & Łyś, A. (2019). They must be sick: Consensual nonmonogamy through the eyes of psychotherapists. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 37(1), 58–81. 24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2019.1670787.

- Hardy, J. W., & Easton, D. (2017). The ethical slut: A practical guide to polyamory, open relationships and other freedoms in sex and love. Clarkson Potter/Ten Speed.

- Haupert, M., Gesselman, A., Moors, A., Fisher, H., & Garcia, J. (2016). Prevalence of experiences with consensual nonmonogamous relationships: Findings from two national samples of single americans. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(5), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2016.1178675

- Henrich, R., & Trawinski, C. (2016). Social and therapeutic challenges facing polyamorous clients. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 31(3), 376–390.

- Herbitter, C., Vaughan, M. D., & Pantalone, D. W. (2021). Mental health provider bias and clinical competence in addressing asexuality, consensual non-monogamy, and BDSM: A narrative review. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.1969547

- Hutzler, K. T., Giuliano, T. A., Herselman, J. R., & Johnson, S. M. (2015). Three’s a crowd: Public awareness and (mis)perceptions of polyamory. Psychology & Sexuality, 7(2), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2015.1004102

- Hymer, S. M., & Rubin, A. M. (1982). Alternative lifestyle clients: Therapists’ attitudes and clinical experiences. Small Group Behavior, 13(4), 532–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/104649648201300408

- Jordan, S. (2018). “My mind kept creeping back… this relationship can’t last”: Developing self-awareness of monogamous bias. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 30(2), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2018.1430459

- Kisler, T. S., & Lock, L. (2019). Honoring the voices of polyamorous clients: Recommendations for couple and family therapists. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 31(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2018.1561017

- Klesse, C. (2011). Notions of love in polyamory- Elements in a discourse on multiple loving. Laboratorium, 3, 4–25. Retrieved from https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/notions-of-love-in-polyamory-elements-in-a-discourse-on-multiple-loving/pdf

- Knapp, J. J. (1975). Some non-monogamous marriage styles and related attitudes and practices of marriage counselors. The Family Coordinator, 24(4), 505–514. https://doi.org/10.2307/583034

- Kross, E., Berman, M. G., Mischel, W., Smith, E. E., & Wager, T. D. (2011). Social rejection shares somatosensory representations with physical pain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(15), 6270–6275. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1102693108

- Lambert, M. J., & Barley, D. E. (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357

- LeMoncheck, L. (1997). Loose women, lecherous men: A feminist philosophy of sex. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780195105568.001.0001

- Martin, D. J., Garske, J. P., & Davis, M. K. (2000). Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 438–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Moors, A. C. (2017). Has the American public’s interest in information related to relationships beyond "the couple" increased over time? Journal of Sex Research, 54(6), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1178208

- Moors, A. C., & Schechinger, H. (2014). Understanding sexuality: Implications of Rubin for relationship research and clinical practice. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 29(4), 476–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2014.941347

- Nash, C., Beals, K., Peissig, J., & Trevino, C. (2018). Monogamists and consensual nonmonogamists: Comparing attachment styles, use of relationship therapy, satisfaction with therapeutic services, and overall relationship satisfaction. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. 10977641

- Razzaque, R., Okoro, E., & Wood, L. (2015). Mindfulness in clinician therapeutic relationships. Mindfulness, 6(2), 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0241-7

- Rubel, A. N., & Bogaert, A. F. (2015). Consensual nonmonogamy: Psychological well-being and relationship quality correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 52(9), 961–982. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.942722

- Schechinger, H. A., Sakaluk, J. K., & Moors, A. C. (2018). Harmful and helpful therapy practices with consensually non-monogamous clients: Toward an inclusive framework. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(11), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000349

- Sparks, J. A., Kisler, T. S., Adams, J. F., & Blumen, D. G. (2011). Teaching accountability: Using client feedback to train effective therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(4), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00224.x

- Spinelli, E. (2005). The interpreted world (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/861727/the-interpreted-world-an-introduction-to-phenomenological-psychology-pdf (Original work published 2005)

- Sullivan, S., Nalbone, D., Angera, J., & Wetchler, J. (2017). Marriage and family therapists’ attitudes and perceptions of polyamorous relationships, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Retrieved from: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/dissertations/AAI10681157/

- Thompson, A., Bagley, A., & Moore, E. (2018). Young men and women’s implicit attitudes towards consensually nonmonogamous relationships. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1435560

- Urquhart, B., Bulow, B., Sweeney, J., Shear, M. K., & Frances, A. (1986). Increased specificity in measuring satisfaction. The Psychiatric Quarterly, 58(2), 128–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01064054

- Weitzman, G. (2006). Therapy with clients who are bisexual and polyamorous. Journal of Bisexuality, 6(1-2), 137–164. https://doi.org/10.1300/J159v06n01_08

- Weitzman, G. D. (1999). What psychology professionals should know about polyamory: The lifestyles and mental health concerns of polyamorous individuals [Paper presentation]. Paper presented at The 8th Annual Diversity Conference, Albany, NY. Retrieved from http://www.polyamory.org/∼joe/polypaper.htm

- Wolf, N. (1997). Promiscuities: The secret struggle for womanhood. Choice Reviews Online, 35(04), 35–2433. https://doi.org/10.5860/choice.35-2433

- Zimmerman, K. J. (2012). Clients in sexually open relationships: Considerations for therapists. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 24(3), 272–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2012.648143

Appendix A.

Interview Schedule

Consensual Non-Monogamy Experiences Survey

What special challenges have you faced when receiving mental healthcare as someone who is a part of consensual non-monogamy?

In what ways have you felt supported regarding being a part of consensual non-monogamy by mental healthcare practitioners?

What assumptions do you think mental healthcare practitioners made about you, given that you are a part of consensual non-monogamy?

What information would be helpful for mental healthcare practitioners to help them understand, and potentially improve the therapeutic experience for people who are a part of consensual non-monogamy who seek services?