ABSTRACT

Culture plays an important role in the development of mental health, especially during childhood and adolescence. However, less is known about how participation in cultural rituals is related to the wellbeing of youth who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and part of the Global Majority. This is crucial amid the COVID-19 pandemic, a global event that has disproportionally affected BIPOC youth and disrupted participation in rituals. The goal of this paper is to promote advances in clinical child and adolescent psychology focused on rituals. We begin by defining culture and rituals and examining their role on development. We illustrate these issues with the Lunar New Year in China, Maya rituals in México, Ramadan in Turkey, and Black graduations and Latinx funerals in the United States. We discuss how the pandemic has affected participation in these rituals and their potential impact on BIPOC children and adolescents’ mental health. We propose future directions and recommendations for research.

Culture plays an important role in the development of mental health, especially during childhood and adolescence (García Coll et al., Citation1996; Spencer, Citation2006). However, less is known about how participation in cultural rituals promotes wellbeing among children and adolescents (henceforth, youth) who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), and part of the Global Majority (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021). This research is pressing given the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on global prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents, whose symptoms of anxiety and depression have significantly exacerbated (Racine et al., Citation2021).

The elevated rates of psychopathology are due, in part, by the fact that the pandemic has increased social isolation and disrupted youth participation in rituals, such as Quinceañeras (15-year-old celebrations), graduations, and funerals. These disruptions, in turn, have compromised how youth deal with stress, get social support, and cope with bereavement. The goal of this paper is to promote advances in clinical child and adolescent psychology focused on rituals and mental health among BIPOC youth. We begin by defining culture and rituals and examining their role on development. We illustrate these issues with the Lunar New Year in China, Maya rituals in México, Ramadan in Turkey, and Black graduations and Latinx funerals in the United States. We discuss how the pandemic has affected participation in these rituals and their potential impact on BIPOC youth’ mental health. We propose future directions and recommendations for research.

The role of rituals on BIPOC youth’ mental health has been explored in some fields before the pandemic. For instance, Africentric rites of passage interventions with African American youths have shown promising results in fostering resilience and wellbeing in the fields of social work (Harvey & Hill, Citation2004; Harvey & Rauch, Citation1997; Washington et al., Citation2017), counseling (West-Olatunji et al., Citation2008), and education (Desai, Citation2020). However, less is known about the role of rituals in clinical child and adolescent psychology, especially since the beginning of the pandemic.

Cultural rituals have recently received increased attention in developmental psychology (Legare & Nielsen, Citation2020). Nevertheless, most emerging work is Eurocentric and not focused on the perspectives or needs of BIPOC youth. Centering on BIPOC youth is crucial because they deal with intersectional experiences of oppression before and during the pandemic that impact their mental health (Del Río-González et al., Citation2021), including racism, racial discrimination (Cheah et al., Citation2021), and historical trauma (John-Henderson & Ginty, Citation2020).

Racism refers to “the exercise of power against a racial group defined as inferior by individuals and institutions with the intentional or unintentional support of the entire culture” (Jones, Citation1972, p. 117). Racial discrimination is the behavioral enactment of racism with the purpose of maintaining a power imbalance between racial groups (Neblett, Citation2019). Ethno-racial or historical trauma refers to “the individual and/or collective psychological distress and fear of danger that results from experiencing or witnessing discrimination, threats of harm, violence, and intimidation directed at ethno-racial minority groups” (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019, p. 49).

BIPOC youth also have unique strengths, resources, and sense of agency that protect them against adversity and help them heal from historical trauma (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021). For instance, Chinese American adolescents’ bicultural identity integration can buffer the impact of racism on internalizing symptoms during the pandemic (Cheah et al., Citation2021). For these reasons, our discussion is grounded in developmental theory and research that challenges deficit perspectives and emphasizes the strengths of BIPOC youth (García Coll et al., Citation1996; Spencer, Citation2006), and centered on the work of Black and Brown scholars (Causadias et al., Citation2022).

Culture, Rituals, and BIPOC Youth Development

Culture has been conceptualized as a dynamic system made of social relationships, environmental influences, community practices, and power asymmetries (Causadias, Citation2020). Cultural resources and practices can protect against adverse experiences and promote wellbeing (Azmitia, Citation2021; Causadias & Cicchetti, Citation2018; Neblett et al., Citation2012). For example, relying on traditional cultural practices can have a positive effect in the development of mental health among Latinxs (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019). Puerto Rican children whose families are involved with Espiritismo and/or Santería were twice more likely to employ mental health services over a period of three years than children whose families do not engage in these cultural practices (Zerrate et al., Citation2022), indicating that these practices may reduce barriers to service utilization.

The concept of cultural ritual (henceforth, rituals) typically refers to a broad group of coherent behaviors that follow an order, are relatively scripted, and have important social and individual meanings that may not be apparent to outgroup members (Kreinath, Citation2018). Rituals are the arranged performance of an intricate sequence of choreographed words and actions in a ceremony that provide meaning and purpose to individuals and groups (Kreinath, Citation2018). We use the terms rites and rituals interchangeably, although we acknowledge there is considerable debate regarding their similarities and differences (Kreinath, Citation2018). We also recognize that there are many terms to refer to different types of rituals. For instance, rites of passage can also be labeled as initiation or transitional rituals (Forth, Citation2018). In this article, we use the term ritual in a broad sense that includes celebrations, ceremonies, festivals, rites, and traditions.

Theory and research in social sciences support two major perspectives on the role of rituals. First, a sociological perspective that emphasizes the function of rituals in maintaining social cohesion, compliance with moral norms, and social standing within a community (Ross & Kohut, Citation2018). Rituals legitimize social hierarchies and reproduce power structures by affirming social roles in everyday life (Bloch, Citation1992). For instance, baptism in many Latin American communities produces Compadrazgo (co-parenthood), a spiritual kinship created between parents and godparents of a child (Alum, Citation2018). Compadrazgo enhances social capital and strengthens previous family, friendship, and social bonds (Alum, Citation2018; Bolin, Citation2006).

Second, a psychological perspective that underlines the importance of rituals in promoting a sense of belonging and identity through socialization processes. Rites of passage or initiation redefine the social status of a person in their community, signaling the journey from one developmental stage to another (La Fontaine, Citation2018), illustrating the power of culture in providing a sense of purpose and meaning to individuals. For instance, La Quinceañera is an important rite of passage for Latina girls at age 15, a celebration of their developmental transition from childhood to maturity that is associated with increased autonomy and changes in mother-daughter relationships (Romo et al., Citation2014). Caregivers play a key role in facilitating children’s participation in rituals by helping them internalize family and cultural values (Cervera, Citation2007; Grusec, Citation2011).

Latinx youth experiencing marginalization have used La Quinceañera to express pride and resistance, as the case of Mexican American girls and families affirming their identity especially in the context of growing hostility toward them in the US during the Trump administration (Verdín & Camacho, Citation2019). Moreover, some transgender Latina girls have used La Quinceañera to challenge traditional gender norms and to celebrate their new place in their community with their mothers, their trans-madrinas (trans-Godmothers), and their friends (Santini, Citation2017). These examples illustrate how youth use rituals as collective action toward healing and liberation (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021; Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019; French et al., Citation2020).

The fact that rituals have both sociological and psychological meanings helps distinguish them from other phenomena, such as idiosyncratic routines, habits, and ritualistic behaviors. For instance, rituals have both collective and personal meaning, while ritualistic behaviors that individuals perform to cope with anxiety or trauma, such as repetitive hand movements, often lack a social dimension (Brooks et al., Citation2016). Rituals are not merely habits that have practical purpose but have a symbolic dimension that transcends utility (Brooks et al., Citation2016).

Rituals have profound developmental significance. Rites of passage or initiation may signal and enact the conclusion of childhood and the admission into adulthood (La Fontaine, Citation2018). This is not merely symbolic but involves new social roles and meanings. After participating in rites of passage, youth assume the rights and duties reserved to adults, changing their social and political status (La Fontaine, Citation2018). This is true for graduations, confirmation for Catholics, and Bat Mitzvah and Bar Mitzvah for Jews.

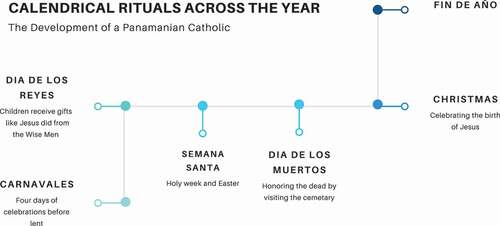

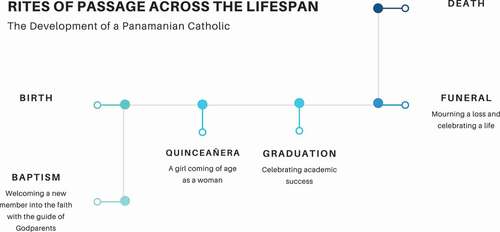

Time is a central dimension of rituals and is useful in distinguishing their nature. Doctrinal rituals often take place weekly, such as participation in religious celebrations such as Friday prayers for Muslims, Sabbath for Jews on Friday evening and Saturday, and Sunday Mass for Catholics. Calendrical rituals can take place once a year and often mark a transition from one season to the next, such as harvest rituals and the Lunar New Year for Chinese people. Rites of passage often take place once in the lifespan and mark developmental transitions, such as baptisms following birth and funerals following death (La Fontaine, Citation2018). See, for an illustration of the development of a person across these types of rituals.

In terms of the clinical relevance of rituals, we acknowledge a rich tradition of Africentric rites of passage interventions with African American youth (Harvey & Hill, Citation2004; Harvey & Rauch, Citation1997; West-Olatunji et al., Citation2008). These interventions are based on the notion that youth of African descent can benefit from participating in traditions centered on African cultures that can help them heal and overcome the legacy of historical trauma resulting from the transatlantic slave trade, the Jim Crow era, and institutionalized racism today, instilling a sense of pride, and self-worth (Washington et al., Citation2017).

These interventions incorporate rites of passage to enable successful and healthy transitions from adolescence to adulthood (Washington et al., Citation2017). For instance, the MAAT Adolescent and Family Rites of Passage Program focuses on developing emotional strengths and learning Africentric values for eight weeks culminating in a ceremony designed to show their growth and learning in the presence of their family, friends, and significant others (Harvey & Hill, Citation2004). While unique and valuable rites of passage are created for the purpose of these programs, in this article we focus on BIPOC youth participation in rituals created by their own communities without professional intervention, especially during the pandemic.

The pandemic has disrupted family dynamics (Eales et al., Citation2021), including the development and maintenance of culture through rituals. These disruptions may be particularly pronounced among BIPOC children and adolescents, with important implications for their mental health. Along these lines, we present important rituals in China, México, Turkey, and the United States. Within these examples, we outline recommendations and questions for research that probes the impacts of these pandemic-related disruptions on child and adolescent mental health.

Lunar New Year in Mainland China: A Time of Family Reunion for Chinese People

Chinese people are the largest ethnic group in the world, originating in the Hua-xia region of central northern China, though there is great within-group heterogeneity (Tseng et al., Citation1995). Several common themes of Chinese culture have been discussed in relevance to mental health, including the strong emphasis on family and collective responsibility, parent-child bond, social relationships and networks (Wu & Tseng, Citation1985), and harmony/harmonization (Li, Citation2006). Chinese culture is an important influence on Chinese youth’s mental health (Wu & Tseng, Citation1985).

The Lunar New Year is a calendrical ritual and one of the most important holidays for Chinese communities in Mainland China and in the diaspora. To celebrate the Lunar New Year, youth and families travel to their hometown to visit their elderly parents, left-behind spouse, children, and/or extended family members. For many children, this is the only time of the year when they can see their parents or grandparents. Starting on the Eve of the Lunar New Year, called Chu-xi, the Chinese light dazzling fireworks to eliminate (Chu) devils of the year (Xi). Although there are variations, the Eve’s dinner menu typically includes fish (same pronunciation as abundance), rice cake (same pronunciation as “high,” meaning success), and dumplings (the shape imitating Chinese ingot, Yuan-bao, used as money in ancient China).

Homes, particularly doors, are decorated with red-colored arts and spring couplets, to express wishes and blessings for the new year. Large-scale New Year Miao-hui (fairs) are held around temples for people to gather, pray, and enjoy fun activities, folk performance, and markets. The Chinese people worship their Gods and ancestors during the holiday by burning incense at temples and burning joss paper money to connect the spirits of their family members who passed away. Although the practices of firework traditions have decreased over time to protect the environment, this ritual still represents an inseparable part of Chinese culture.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly 3 billion domestic trips were made during every Lunar New Year holiday; however, in 2020, the first cluster of COVID-19 cases that emerged in Wuhan preceded the holiday, and only a little over 1.2 billion trips were made because of the intense lockdowns and stringent travel restrictions (Tan, Citation2021). In 2021, the Chinese government implemented more stringent guidelines such that people received various formats of incentives to spend the holiday at where they were (Huang, Citation2021), and if they traveled, there would be (often covert) discrimination or even punishment (e.g., layoffs).

Consequently, the Chinese people sacrificed their personal needs of family reunion and holiday celebration to help their homeland curb the COVID-19 outbreak: people avoided traveling and isolated themselves at home under the enforcement of bans on social gatherings; New Year Eve’s dinner was simplified, due to skyrocketed prices of grocery items and some family members’ absence; children who always received “red pocket” money as New Year’s gifts lost this tradition because paper currency could transmit the virus; left-behind children of urban migrant workers missed seeing their parents; rural-to-urban children could not go home for the holiday; and school-aged children continued to engage in online learning.

There is scarce research on the link between participating in the Lunar New Year and the development of psychopathology, resilience, and personal growth in Chinese youth. This is pressing in light of evidence of elevated mental health problems among Chinese youth during the COVID-19 pandemic, including depression and anxiety (Duan et al., Citation2020), ADHD symptoms (J. Zhang et al., Citation2020a), self-injury, and suicidal behaviors (L. Zhang et al., Citation2020b). Some questions that can advance knowledge on the links between the Lunar New Year participation and mental health are: Do the practices of cultural rituals and symbolic actions during the Lunar New Year serve as sources of family love and support that buffer against the negative impacts of stressful events or adversities on children’s mental health? Do these practices reduce levels of conflict and promote secure attachment and family cohesion, particularly in multigenerational families? During a time when traditional ways of holiday celebration are disrupted, will parents’ intention and actions to create and implement new symbolic rituals be associated with children’s mental health? Answers to these questions will provide important knowledge on the linkages between cultural rituals, family relations, and mental health and contribute to an emerging body of research on the role of culture in development and psychopathology.

Maya Children’s Participation in Rituals in México: Traditions of Social Support

In México there are 78 distinct Indigenous groups (21.5% of the population) and 68 Indigenous languages (INEGI, Citation2021). Although many of the Indigenous groups identify as Catholics, the majority practice Catolicismo popular (popular Catholicism), a syncretic religion that incorporates elements of pre-Columbian rituals (Bonfil Batalla, Citation1987). This syncretism reflects the strength and resilience of Indigenous people and practices enacted in rituals, with some communities holding over 50 ceremonies in a year (Corona & Zavala, Citation2002; Echeverría, Citation1994).

Through rituals, these communities have resisted imposed ways of organizing, living and learning which are violent and contradictory to their collaborative and relational culture, which connects people to particular places of origin, and their natural surroundings (Cajete, Citation1994). These Indigenous communities have found in their rituals a way to preserve millennial ways of knowing and a unique way to resist colonialism (Bonfil Batalla, Citation1987, Citation1996).

All community members are expected to participate in rituals, including infants and children, and everyone is allowed to contribute (Bolin, Citation2006). Children are present during community rituals, religious ceremonies, as well as political protests and resistance movements. Integrating children is crucial to ensure the cultural reproduction, preservation, and continuity of millenary practices (Corona & Zavala, Citation2002). Participating in rituals also allows children to forge a strong collective relationship with the community.

Maya communities in Yucatán are well known for their calendrical rituals, such as the annual Ch’a chaak ritual, which literally translates to “rain calling” done by milperos to ensure the rain Gods will be benevolent and provide the necessary water to sustain life, as well as Catholic celebrations to honor saints, such as the celebration of La Virgen de Guadalupe (The Virgin of Guadalupe). This is also the time when adults, mostly fathers, return to their community to take part in these rituals. These rituals often last multiple days and are crucial to the social and emotional wellbeing of individuals and serve to maintain the social fabric of the community, create reciprocal relationships, and provide social support or safety net.

Other Maya rituals are important to mark crucial developmental milestones such as the Hetzmek (or the Maya baptism) celebrated at the age of 3 months to signal infants’ developmental transition, as parents and Godparents provide children with the tools and foods aimed to support children’s social responsibilities and intellectual development (Cervera, Citation2007). Among children, Maya rituals foster autonomy, the development of initiative, and promote a sense of personal responsibility to the community (Alcalá et al., Citation2021b).

Social distancing mandates in México during the COVID-19 pandemic prevented many Indigenous communities from organizing rituals. Not being able to participate and enjoy the annual celebrations was reported by Yucatec Maya mothers as one of the most difficult challenges of the pandemic, along with the dire economic conditions and the lack of school resources for their children (Alcalá et al., Citation2021a). Mothers also mentioned that children missed going to church events and other community rituals (Alcalá et al., Citation2021a), showing the importance of rituals in providing social support and a space for collective celebration.

More research is needed to understand the role of participating in rituals and the development of psychopathology among Indigenous children in México. This is necessary in light of evidence that Mexican adolescents are struggling during the pandemic to cope with stress related to school pressures, and changes in their routine and family dynamics (Barcelata-Eguiarte & Bermúdez-Jaimes, Citation2022). Given their unique history, resources, and circumstances, more studies are needed to grasp the implications of these changes for the mental health of Maya children in México.

Some questions that can advance knowledge on the links between Maya children’s participation in rituals and developmental psychopathology are: Do the practices of cultural rituals and the integration of Maya children in all aspects of these events serve as a protective factor against the economic and social violence Mayan communities experience? What are the resources available or needed to support the continuity of rituals in Maya communities? Does engagement in multiple types of rituals predict children’s social and emotional development? Answers to these questions will help us understand the long-term impact of the pandemic on the everyday life and rituals in the Maya communities by illustrating how ritual practices have transformed in ways that might support youth mental health and wellbeing. Findings from future studies will also help us understand how child development is conceptualized and how children are integrated in rituals within Maya communities.

The Month of Ramadan: A Time of Social Cohesion in Turkey

Turkey is a country at the intersection of the Middle East and Europe. Although the overwhelming majority is Muslim, the population is vastly heterogeneous. Along with its diversity, people of Turkey share common values, practices, traditions, and understandings that culminate into what is referred to as the “Turkish culture.” Cultural values such as the importance of family cohesion, interdependence, relatedness, generational hierarchy (e.g., respect for elders) are still very salient despite social change. Research has documented close emotional bonds and strong ties with extended family (Kagitcibasi & Ataca, Citation2005), leading to framing Turkish culture as a “culture of relatedness” (Kagitcibasi, Citation2005).

The Lunar month of Ramadan is an important calendrical ritual, the Holy Month of fasting which includes numerous social and spiritual practices. Revered as the month of the revelation of Quran, the Holy Book of Islam, Ramadan, brings a set of rituals that continues throughout the month such as fasting (from dawn to sunset throughout the month), iftar (breaking the fast at sunset), sahoor (meal before dawn), taraweeh (communal prayers held every night), moqabala (communal recitation of Quran) and bayram (celebration/feast upon the end of the month).

Thus, the month of Ramadan brings with itself a long-established tradition of togetherness that distinguishes it from the rest of the year. Iftar is a special occasion among family, friends, relatives, colleagues, neighbors and even inhabitants of the same street, for the religiously observant as well as those who are not. Taraweehs are held every night at the mosques, where families gather. At the end of the month, bayram is celebrated as an official public holiday. Celebrations take place among family, relatives, neighbors, and friends. Bayram is a very special occasion for most of the population to visit family and relatives, especially the elders. Overall, Ramadan serves as a time of social cohesion and evidence shows a positive impact of Ramadan rituals and practices on mental health in Turkey (Ugur, Citation2018).

With the social distancing measures put in place in Turkey during the pandemic, the month of Ramadan has lost its social aspects almost entirely. Long-established cultural tradition of family visits and social gatherings could not take place. Iftars took the forms of isolated dinners at home. People broke fast solitarily or within nuclear families at best. Taraweeh prayers, once drew large crowds and served as an occasion for socialization, were no longer held in mosques. Among all, the most striking change was observed on the three-day bayram, which has been traditionally a widely celebrated holiday at the conclusion of the month. Family gatherings, reunions with relatives, and friends during bayram were disrupted.

More research on the positive effect of participating in Ramadan on mental health and wellbeing among Turkish Muslim youth is necessary, especially in the context of the pandemic. Recent studies show higher parental stress and increased psychological symptoms among children and adults since the start of the pandemic in Turkey (Büber & Aktaş Terzioğlu, Citation2021; Terzioğlu & Büber, Citation2021). High levels of depression and anxiety were found among Turkish adolescents and college students during the pandemic (Turk et al., Citation2021), with being female and having poor family relationships identified as risk factors (Cam et al., Citation2021).

Some questions that can advance knowledge on the links between the Ramadan participation and developmental psychopathology are: How does the disruption brought by the pandemic impact the way Turkish people celebrate Ramadan in the future and how do these changes affect the development of youth mental health? What types of coping mechanisms and new practices have Turkish communities developed to overcome the disruptions of Ramadan brought by the pandemic? How do children and adolescents learn and embrace these innovations, and create their own? Research on these questions can support evidence-based solutions to the disruptions to everyday life brought up by the pandemic and promote the wellbeing of Turkish youth.

Graduation for Black Youth in the U.S.: Celebrating Black Excellence

Black Americans constitute 13.4% of the United State population (U.S. Census Bureau, Citation2019), and their collective contributions have been foundational to the development of the country (Hannah-Jones, Citation2021). Black is an inclusive term for individuals that self-identify as Black and/or are descendants of individuals from the Caribbean and African diaspora that immigrated to the US (Agyemang et al., Citation2005). The legacy of systemic, structural, and interpersonal racism has led to poorer health, lower socioeconomic status, and worse educational outcomes for Black Americans (Gee & Ford, Citation2011).

In research, there is a persistent narrative of Black student underachievement despite evidence suggesting that the educational attainment gap between Black and White students is narrowing. Black excellence is the product of the historic inequalities faced by Black people and represents commitment to community progress, often through education (King, Citation2020). In this context, graduation ceremonies may have a profound cultural meaning for Black communities as they represent the persistence and resistance of both past and present and offer a unique opportunity to celebrate Black excellence.

Graduation is an important rite of passage for secondary (i.e., high school) and post-secondary (i.e., college) students that celebrates completing an academic degree and receiving a diploma. There are common graduation traditions in the United States, including wearing graduation robes, the playing of “Pomp and Circumstance,” and reading of graduates’ names. Graduation marks the transition from one stage of a person’s life, often bringing a new set of responsibilities. Graduation ceremonies are a time of celebration for students and families.

Many Black students attribute their academic success to having supportive communities, including family, the Black Church, and fictive kin who strengthen students’ commitment, hope, and perseverance (Brooks & Allen, Citation2016). Black families send messages to students about their future selves, specifically regarding the importance of “being somebody” and “having a future” that they can be proud of (Carey, Citation2021), which can be accomplished through educational attainment. Moreover, graduation and educational attainment are associated with greater social and economic opportunities, long-term benefits to physical health (Allen et al., Citation2019), and lower depressive symptoms and psychological distress (Assari, Citation2018).

When describing the importance of graduation, Black students often emphasize giving back and focusing on the collective uplift of their communities (McCallum, Citation2017). For many Black students and families, graduation represents attaining what was long denied for their ancestors (McCallum, Citation2017). Familial messages often underscore the importance making oneself and family proud (Carey, Citation2021). Graduation presents Black students with the opportunity to use their knowledge and resources gained in school to make economic, political, and social changes (McCallum, Citation2017).

The pandemic has disrupted graduations for Black students through restrictions on travel and social gatherings, resulting in delays and often cancellations of graduation ceremonies. In addition to being more likely to contract the COVID-19 virus, evidence shows that that BIPOC students in the U.S. were more likely to have their graduations delayed or canceled (Aucejo et al., Citation2020). The disappointment of having canceled ceremonies may confound with pandemic-related stress many BIPOC youth feel about life after graduation, particularly regarding the loss of job offers and expectations of lower wage earnings (Aucejo et al., Citation2020).

More evidence is needed on how graduation ceremonies, or their disruption, are associated with the development of psychopathology among Black youth and their families. Longitudinal research is needed to better understand the mechanisms involved in graduation participation that protect against adversity and promote resilient functioning among Black students and their families. Some questions that can advance knowledge on the links between graduation for Black youth and developmental psychopathology are: How does the delay and cancellation of graduations influence career trajectories, views of educational importance, and sense of belonging among Black students? What types of coping strategies are Black students using following the disruption of graduation ceremonies?

Further, researchers should examine how the disruption of these ceremonies has impacted the support networks of Black students. How does the cancellation of graduation influence how parents socialize their students about academic persistence and educational attainment? There must be unified efforts to develop and provide culturally sensitive health resources to communities as students and their families learn to adapt to isolation, disruptions, and public health guidelines. Graduation ceremonies represent not only the past and present persistence of Black students, but the history of Black excellence, thus, research must investigate how to protect and promote this legacy of resilience.

Latinx Youth in the U.S. Participating in Funerals: “Un Entierro Como Dios Manda”

People of Latin American and Caribbean ancestry living in the U.S. make over 18% of the population and employ different terms to identify themselves, including pan-ethnic labels such as Hispanic, Latino/a, Latine, and Latinoamerino, and/or specific labels related to their countries of origin, such as Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and/or Cuban American (Noe-Bustamante et al., Citation2020). Although they are often considered a monolithic ethnic group, there is considerable variation within Latinx people in terms of skin color, ethnic-racial identity, acculturation, legal status, and migration experience (Cahill et al., Citation2021; Fuentes et al., Citation2021).

Cultural practices and values are critical in shaping Latinx child development (Azmitia, Citation2021; Cahill et al., Citation2021; Stein et al., Citation2014). Latinx children in the United States often have to adapt and negotiate mainstream and heritage cultures; learn different languages, traditions, and expectations; and deal with ethnic, racial, and gender discrimination (Azmitia, Citation2021). Endorsing familism values that emphasize devotion and obligation to the family is important for Latinx youth development (Stein et al., Citation2014), and it is related to positive academic outcomes and higher warmth and support in family interactions, as well as lower internalizing and externalizing behavior problems, and less conflict and negativity in the family (Cahill et al., Citation2021).

Research centered on Latinxs has underscored the cultural significance of rites of passage such as funerals, in helping to cope with bereavement after the death of a loved one (Diaz-Cabello, Citation2004). Rather than the end, death is understood as a continuation of life for many Latinxs, in which the bond with the deceased can be maintained through rituals that can alleviate the pain of loss (Garcini et al., Citation2019). The constellation of mourning rituals among Latinxs include rites of passage such as wakes, funerals, and Novenas (nine successive days or weeks of prayer), calendrical rituals such as Día de los Muertos and the anniversary of the death of the loved one, and doctrinal rituals such as rosaries and Sunday Mass (Garcini et al., Citation2019).

During the pandemic, Latinx youth and families may have missed a crucial opportunity to experience these processes without access to traditional funeral ceremonies and other mourning rituals (Hernández‐Fernández & Meneses‐Falcón, Citation2021). This can increase long-term feelings of guilt, given the obligation to give departed family members a funeral according to cultural scripts and traditions, or “un entierro como Dios manda” (a burial like God commands). This can be challenging for first-generation immigrants living in the diaspora who loose family members back home and are unable to travel and participate in mourning rituals (Garcini et al., Citation2019).

Not being able to participate in rituals can compromise Latinx youth’s ability to cope with bereavement and facilitate grief collectively with their family and community. This is especially harmful because Latinx and other BIPOC youth have higher risk of becoming orphan due to the COVID-19 virus compared to White youth in the US, increasing their risk of developing negative academic and mental health outcomes (Hillis et al., Citation2021). These inequities are compounded with current and previous experiences of racial discrimination and ethno-racial trauma, forced family separation, and xenophobia (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019).

However, less is known of how Latinx youth use their culture to cope with anxiety, deal with bereavement and other traumatic life events, overcome isolation and marginalization, and adapt to academic, peer, and family demands during the pandemic (for an exception, see Cortés-García et al., Citation2021). During the pandemic, youth in general have not been prioritized in attending funeral services, perhaps based on a misguided assumption that it can be traumatizing to them (Johns et al., Citation2020). Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the mental health correlates of Latinx youth participation in funerals and other mourning rituals.

Some questions that can advance knowledge on the links between funeral participation and developmental psychopathology are: How does relationship quality, as well as the nature (death of a parent, grandparent, and/or sibling), and magnitude of the loss (one or several family members) impact Latinx youth bereavement? How variations in type, frequency, and engagement in funeral and mourning practices among unique communities (e.g., Cuban, Mexican, Puerto Rican) shape the development of youth mental health? What is the role of family religiosity, pandemic experiences, and financial resources? How are these processes shaped by youth’s age, gender and racial socialization, and acculturation? Answers to these questions will help us understand how Latinx youth cope with bereavement, and how participation in cultural traditions and practices associated with death impacts their mental health and wellbeing.

Future Directions for Research

More basic research is needed about the role of participation in rituals on BIPOC youth’ mental health, a critical question that demands more clinical research using a team science approach (De Los Reyes, Citation2021). We offer three main recommendations for future research.

Recommendation 1: Understanding the Mechanisms Linking Rituals and Mental Health

Following recent arguments for clinical research centered on BIPOC youth (Jones & Neblett, Citation2017), we emphasize the importance of focusing on processes and mechanisms underlying the link between participation in rituals during the pandemic and BIPOC youth’ mental health. Attention to these processes is critical during the pandemic because some of the mechanisms that promote BIPOC positive youth development and protect against adversity through participation in rituals, can also explain how the pandemic has increased the risk of developing psychopathology. Although there are several, we argue for more research on three interrelated mechanisms: stress, social support, and grief.

First, rituals play an important role in emotion regulation (Hobson et al., Citation2018). A growing body of theory and research supports the notion that participation in rituals can have positive effects on the development of mental health by providing strategies to cope with stress. For instance, rites of passage take place in the context of stressful life transitions, such as births, graduations, weddings, and deaths (Brooks et al., Citation2016). Rituals may reduce stress by providing structure and a sense of order, offering a sense of purpose that go beyond the self, and working as a form of placebo that alleviate symptoms (Brooks et al., Citation2016).

Considering the role of rituals in coping with stress is crucial during and following a pandemic that has increased stress due to uncertainty about school and fears of getting sick among African American schoolchildren (Bhogal et al., Citation2021). The pandemic has also affected youth mental health indirectly by disrupting family dynamics. Stressed parents can be less effective in promoting emotion regulation strategies at home, which exacerbate children’s psychopathology (Cohodes et al., Citation2021). Research using daily diaries can reveal the way doctrinal and calendrical rituals help BIPOC youth to deal with stress.

Second, rituals play an important role in promoting social connections and support. Participating in rituals can help children develop a sense of belonging and facilitate group cohesion (Wen et al., Citation2016). Participation in weekly doctrinal rituals such as going to church, mosque, and/or synagogue can foster community engagement and consolidate social bonds (Ross & Kohut, Citation2018). Weekly secular rituals, such participating is sports and other extracurricular activities, can also provide BIPOC youth with consistent opportunities for social support.

Understanding the importance of rituals in promoting social support is crucial during a pandemic that has inhibited access to social support through stay-at-home orders, lockdowns, travel bans, and social distancing mandates and guidelines that limit physical interactions (Johns et al., Citation2020). These necessary measures have augmented feelings of loneliness, isolation, and disconnection during the pandemic, which have been linked to increased mental health problems (C. M. Lee et al., Citation2020). Moreover, social support through participation in rituals can help alleviate the stress associated with developmental transitions and guide BIPOC youth on these new roles.

Celebration of calendrical rituals such as Ramadan can serve as a promotive factor for the Turkish people to stay interconnected and receive social support, which in turn significantly reduces stress and promotes mental health (Özer et al., Citation2021). This is critical in the context of the pandemic. Higher anxiety levels among Turkish youth aged 12–18 were associated with feelings of loneliness; and home-quarantine increased both loneliness and anxiety levels (Kılınçel et al., Citation2021). Future studies should examine associations among anxiety, feelings of loneliness, and social support before and after participating in rituals such as Ramadan.

Third, rituals play an important role in facilitating grief after death of a loved one. Funerals, perhaps one of the most researched rituals in connection to mental health and wellbeing, allow the bereaved to experience loss, facilitate the expression of emotions, provide a time and place for collective farewells and storytelling, and mark the transition to a new life without the deceased (Hernández‐Fernández & Meneses‐Falcón, Citation2021). In a way, rituals may function as a bereavement intervention among BIPOC youth, but it has not been studied sufficiently. Funerals and other rituals surrounding death provide a unique opportunity to understand the norms of grief reactions in different cultural groups and advance our understanding of mental health among BIPOC youth (Alvis et al., Citation2022).

Acknowledging the role of rituals such as funerals in facilitating grief and loss is critical during a pandemic that has caused the death of millions of people. Worldwide, over 5.2 million youth have experienced the death of at least one primary caregiver (Unwin et al., Citation2022). Parental bereavement has disproportionally affected Global Majority youth in India, México, Perú, and South Africa (Unwin et al., Citation2022), as well as BIPOC youth in the US, increasing their likelihood of experiencing economic hardship and sexual abuse, and developing mental health problems (Hillis et al., Citation2021).

Finally, the distinction between doctrinal rituals that happen every week, calendrical rituals that happen every year, and rites of passage that often happen once in the lifespan suggest different mechanisms that can play a role in the development of mental health. Doctrinal rituals that are very frequent but lead to low levels of arousal are kept in semantic memory, while rites of passage that are less frequent but lead to high levels of arousal through their emotional impact can forge lasting episodic memories that help strengthen social bonds and provide meaning to developmental transitions (Kavanagh, Citation2018). Research on these mechanisms can provide insights for the design of clinical interventions and improvement of clinical theories.

Recommendation 2: Improving Measurement in the Study of Rituals and Mental Health

Measurement issues play an important role in advancing clinical child and adolescent psychology (De Los Reyes et al., Citation2022; Sanchez et al., Citation2022), and they are also at the heart of research on culture (Causadias et al., Citation2018), healing, and resistance (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021; Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019). Several research studies employ self-reported, retrospective surveys and questionnaires to assess cultural cognitions, while the use of ethnographic and observational methods that examine cultural behaviors that initiate, derail, or maintain trajectories of adaptation and maladaptation are less common (Causadias, Citation2013). Fieldwork on rituals can shed light on the role of rituals on healing BIPOC communities (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021).

To capture the role of rituals in the development of mental health, it is crucial to use a team science approach (De Los Reyes, Citation2021). It is necessary to create research teams that include experts in clinical and counseling psychology, child development, culture, ethnicity, racism, and other fields who can engage in measurement at multiple levels of analysis. Because rituals involve the performance of a sequence of behaviors and ideas related to meanings and symbols (La Fontaine, Citation2018), they require methodologies that capture both behavioral (e.g., video recordings, ethnographies), and cognitive processes (e.g., self-reports, interviews). Collaborative research led by and/or with in-group community members is important to ensure ethical standards and fairness (B. A. Lee et al., Citation2021) and to promote accurate interpretation of data because the meaning of behaviors involved in a ritual may not be apparent to out-group members (Kapitány & Nielsen, Citation2015).

Measurement of rituals centered on BIPOC youth should pay attention to within-group heterogeneity. There is substantial diversity between and within rituals, across communities and over time (Alum, Citation2018), varying in developmental timing and the level of elaboration (La Fontaine, Citation2018). Within the same cultural communities, rituals also vary as a function of gender. Girls and boys often participate in separate rites of passage (La Fontaine, Citation2018), such as Bat Mitzvah and Bar Mitzvah. Gender segregation of rituals is not merely a reflection of cultural norms, but an affirmation of the social meaning of gender and the roles that men and women are expected to take (La Fontaine, Citation2018; Romo et al., Citation2014). In fact, inclusion of women and/or sexual minorities in traditional rituals is the result of their activism and collective action (Prichep, Citation2022; Santini, Citation2017), affirming the importance of rituals in social equity.

Intersectional theory and methods pioneered by Black female scholars offer a valuable avenue to elucidate the joint impact of interlocking systems of oppression on the mental health of BIPOC youth (Del Río-González et al., Citation2021). An intersectional approach to the development of psychopathology requires going beyond on main and interactive effects to focus on structural factors beyond the individual and demographic level, such as inequities in health insurance coverage and access to mental health services (Del Río-González et al., Citation2021). Intersectional mixed methods research are necessary to prioritize multiply marginalized BIPOC youth, recognize and acknowledge their numerous realities, and to examine identity-related experiences together with systems-related collective variables (Watson-Singleton et al., Citation2021).

Informed by intersectionality, future research should examine to what degree BIPOC youth leverage rituals to affirm with their racial and gender identity in their communities. With rising transphobia in countries like the U.S. before and during the pandemic, La Quinceañera can have a unique significance for transgender Latinx girls who employ this ritual to affirm their gender and ethnic-racial identity (Santini, Citation2017). Clinical studies should elucidate to what degree these cultural experiences shape equifinality and multifinality in the development of psychopathology (Causadias, Citation2013; Causadias & Cicchetti, Citation2018).

Future studies should also investigate variation on how rituals are celebrated by youth within the same BIPOC community across generations, geographies, and migration histories. Each generation can challenge and update how rituals are celebrated, leading to departure from tradition (Prichep, Citation2022; Santini, Citation2017). Even within the same country, group members often create unique rituals. Research with Black adolescent boys using in-depth interviews have documented how they experienced musical processions that are part of funerary rituals in New Orleans, a unique tradition not common elsewhere in the U.S. (Bordere, Citation2009). African, Asian, Indigenous, Pacific, and/or Latinx communities living in diaspora create innovations in rituals that reflect their distinctive reality and may depart from ritual traditions in their homelands.

Although we have adopted a strength-based approach by emphasizing the promotive and protective nature of rituals, cultural experiences and processes can also be a source of risk for psychopathology (Causadias & Cicchetti, Citation2018). Some college students in the United States who drink heavily see alcohol abuse as a rite of passage that is central to their college experience, especially males who are part of a fraternity and drink with friends, increasing their risk of developing alcohol and other substance abuse disorders (Crawford & Novak, Citation2006).

Furthermore, financially expensive rituals can be a burden for socioeconomically disadvantaged BIPOC families, who can incur in debt to afford them. Rites of passage such as weddings may require considerable planning and expense, becoming more taxing to family members in charge of preparing and financing them. This is consistent with evidence that rituals can be costly for some individuals (Legare & Nielsen, Citation2020). Given that income, education, and occupation have unique associations with individual levels of behavior problems (Korous et al., Citation2018), future clinical studies should measure how these indicators of socioeconomic status shape the link between participation in rituals and mental health among BIPOC youth. Moreover, studies should examine to what degree rituals may reinforce traditional gender roles and gender stereotypes that marginalize women and/or sexual minorities.

Recommendation 3: Considering Experiences Before, During, and after the Pandemic

Future research on the clinical implications of rituals for BIPOC youth mental health should be centered on lifespan development by considering experiences before, during, and after the pandemic. This is crucial considering a growing body of evidence showing that greater historical trauma before the pandemic predicted larger increases in psychological distress among American Indians and Alaska Natives (John-Henderson & Ginty, Citation2020). Rituals may have a different meaning and serve a unique developmental purpose for BIPOC youth who have experienced ethno-racial trauma before the pandemic (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019).

Participating in Ramadan brings family members together and can strengthen their bonds, promoting positive youth development among Muslims in the U.S. (Alghafli et al., Citation2019). This is crucial in the context of events that took place before the pandemic, such as rising Islamophobia and anti-immigrant rhetoric in the U.S. that has led to travel bans and growing incidents of racism against Americans of Middle Eastern and North African descent (Awad et al., Citation2019). Ramadan can also take a new meaning for Muslim Syrian refugees living in Turkey who have experienced the trauma of war and are often separated from their extended family (Yaylaci, Citation2018).

The Lunar New Year can take a different meaning for youth in mainland China than for Chinese people in diaspora living in Africa, America, Asia, Oceania, or Europe because of their different experiences before and during the pandemic. With the rise of anti-Asian racism in countries like the U.S., cultural affirmation can protect against adversity and promote resilient functioning among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders (Cheng et al., Citation2021). Moreover, participation in rituals such as Día de los Muertos can play a role in healing and promoting hope among Latinx immigrant communities that have experience ethno-racial trauma due to xenophobic racism (Chavez-Dueñas et al., Citation2019).

One potential avenue for clinical research is using quasi-experimental designs that compare siblings within the same families who participated in the same ritual before, during, or after the pandemic, and examine trajectories of psychopathology. This design has been used to compare Mexican-origin siblings who made the transition out of high school before or during the economic recession of 2007 (Perez-Brena et al., Citation2017). Younger siblings who graduated in 2007 were less likely to attend college and more likely to work in lower wage jobs than older siblings who graduated in 2005 (Perez-Brena et al., Citation2017).

Clinical research during and after the pandemic can greatly benefit from digital methods and telehealth applications, such as smartphone apps, virtual reality, and social media (Torous et al., Citation2021). The use of these methods has increased during the pandemic, helping individuals and families overcome barriers to physical access to mental health services (Torous et al., Citation2021) and multigenerational family support (Gilligan et al., Citation2020). Clinical research using digital methods is a promising future direction because they have also been crucial for participation in rituals among BIPOC youth and families during the pandemic. Māori and Samoan peoples saw their traditional ways of mourning disrupted by social gathering restrictions and travel bans, but digital innovations helped them stay connected, participate in funerals, and facilitate grief (Enari & Rangiwai, Citation2021). Future studies should examine the role of technology in rituals as a tool for promoting collective digital resilience (Enari & Rangiwai, Citation2021).

Conclusion

Emphasizing cultural strengths and challenging deficit perspectives of BIPOC youth is central to culturally informed developmental psychopathology (García Coll et al., Citation1996; Spencer, Citation2006). Rituals mark the passing of time and provide meaning and purpose to developmental transitions. Attention to this important dimension of development is pressing in the context of a pandemic that has disrupted everyday life. For these reasons, understanding how rituals protect against adversity and promote wellbeing is a critical future research direction in clinical child and adolescent psychology centered on BIPOC youth.

Acknowledgments

Authors are listed in alphabetical order following the corresponding author. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Lucía Alcalá acknowledges support from UC MEXUS-CONACYT Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (to L.A., 2015-2016). Kamryn S. Morris acknowledges support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse under 2T32DA039772-06. Na Zhang acknowledges support from the National Institute of Mental Health grant under K01MH122502.

Disclosure Statement

Authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Agyemang, C. (2005). Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(12), 1014–1018. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.035964

- Alcalá, L., Gaskins, S., & Richland, L. E. (2021a). A cultural lens on Yucatec Maya families’ COVID‐19 experiences. Child Development, 92(5), e851–e865. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13657

- Alcalá, L., Montejano, M. D. C., & Fernandez, Y. S. (2021b). How Yucatec Maya children learn to help at home. Human Development, 65(4), 191–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000518457

- Alghafli, Z., Hatch, T. G., Rose, A. H., Abo-Zena, M. M., Marks, L. D., & Dollahite, D. C. (2019). A qualitative study of Ramadan: A month of fasting, family, and faith. Religions, 10(2), 123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020123

- Allen, A. M., Thomas, M. D., Michaels, E. K., Reeves, A. N., Okoye, U., Price, M. M., Hasson, R. E., Syme, S. L., & Chae, D. H. (2019). Racial discrimination, educational attainment, and biological dysregulation among midlife African American women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 99, 225–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.09.001

- Alum, R. A. (2018). Compadrazgo. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology (pp. 1–5). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Alvis, L., Zhang, N., Sandler, I. N., & Kaplow, J. B. (2022). Developmental Manifestations of Grief in Children and Adolescents: Caregivers as Key Grief Facilitators. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00435-0

- Assari, S. (2018). Educational attainment better protects African American women than African American men against depressive symptoms and psychological distress. Brain Sciences, 8(10), 182. https:///doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8100182

- Aucejo, E. M., French, J., Araya, M. P. U., & Zafar, B. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on student experiences and expectations: Evidence from a survey. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104271

- Awad, G. H., Kia-Keating, M., & Amer, M. M. (2019). A model of cumulative racial–ethnic trauma among Americans of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent. American Psychologist, 74(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000344

- Azmitia, M. (2021). Latinx adolescents’ assets, risks, and developmental pathways: A decade in review and looking ahead. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 989–1005. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12686

- Barcelata-Eguiarte, B. E., & Bermúdez-Jaimes, M. E. (2022). Psychological responses associated with stress during pandemic by COVID-19 in Colombian and Mexican adolescents. Journal of Stress, Trauma, Anxiety, and Resilience (J-STAR), 1(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.55319/js.v1i1.11

- Bhogal, A., Borg, B., Jovanovic, T., & Marusak, H. A. (2021). Are the kids really alright? Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in a majority Black American sample of schoolchildren. Psychiatry Research, 304, 114146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114146

- Bloch, M. (1992). Prey into hunter: The politics of religious experience. Cambridge University Press.

- Bolin, I. (2006). Growing up in a culture of respect. University of Texas Press.

- Bonfil Batalla, G. (1987). Los pueblos indios, sus culturas y las políticas culturales. Políticas culturales en América Latina, 89–123.

- Bonfil Batalla, G. (1996). México Profundo: Reclaiming a Civilization. University of Texas Press.

- Bordere, T. C. (2009). “To look at death another way”: Black teenage males' perspectives on second-lines and regular funerals in New Orleans. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 58(3), 213–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.58.3.d

- Brooks, A. W., Schroeder, J., Risen, J. L., Gino, F., Galinsky, A. D., Norton, M. I., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2016). Don’t stop believing: Rituals improve performance by decreasing anxiety. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 137, 71–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.07.004

- Brooks, J. E., & Allen, K. R. (2016). The influence of fictive kin relationships and religiosity on the academic persistence of African American college students attending an HBCU. Journal of Family Issues, 37(6), 814–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14540160

- Büber, A., & Aktaş Terzioğlu, M. (2021). Caregiver’s reports of their children’s psychological symptoms after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and caregiver’s perceived stress in Turkey. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2021.1949492

- Cahill, K. M., Updegraff, K. A., Causadias, J. M., & Korous, K. M. (2021). Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 947–985. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000336

- Cajete, G. A. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of Indigenous education (First ed.). Kivaki Press. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED375993

- Cam, H. H., Ustuner Top, F., & Kuzlu Ayyildiz, T. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and health-related quality of life among university students in Turkey. Current Psychology, 41, 1033–1042. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01674-y

- Carey, R. L. (2021). “Whatever you become, just be proud of it.” Uncovering the ways families influence Black and Latino adolescent boys’ postsecondary future selves. Journal of Adolescent Research, 36(2), 154–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/07435584211018450

- Causadias, J. M. (2013). A roadmap for the integration of culture into developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt2), 1375–1398. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000679

- Causadias, J. M., Vitriol, J. A., & Atkin, A. L. (2018). The cultural (mis) attribution bias in developmental psychology in the United States. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 59, 65–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2018.01.003

- Causadias, J. M., & Cicchetti, D. (2018). Cultural development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 30(5), 1549–1555. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001220

- Causadias, J. M. (2020). What is culture? Systems of people, places, and practices. Applied Developmental Science, 24(4), 310–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2020.1789360

- Causadias, J. M., Morris, K. S., Cárcamo, R. A., Neville, H. A., Nóblega, M., Salinas-Quiroz, F., & Silva, J. R. (2022). Attachment research and anti-racism: Learning from Black and Brown scholars. Attachment & Human Development, 24(3), 366–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2021.1976936

- Cervera, M. D. (2007). El hetsmek’ como expresión simbólica de la construcción de los niños mayas yucatecos como personas. Revista Pueblos Y Fronteras Digital, 2(4), 336–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22201/cimsur.18704115e.2007.4.224

- Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Adames, H. Y., Perez-Chavez, J. G., & Salas, S. P. (2019). Healing ethno-racial trauma in Latinx immigrant communities: Cultivating hope, resistance, and action. American Psychologist, 74(1), 49–62. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000289

- Cheah, C. S., Zong, X., Cho, H. S., Ren, H., Wang, S., Xue, X., & Wang, C. (2021). Chinese American adolescents’ experiences of COVID-19 racial discrimination: Risk and protective factors for internalizing difficulties. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(4), 559–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000498

- Cheng, H. L., Kim, H. Y., Tsong, Y., & Joel Wong, Y. (2021). COVID-19 anti-Asian racism: A tripartite model of collective psychosocial resilience. American Psychologist, 76(4), 627–642. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000808

- Cohodes, E. M., McCauley, S., & Gee, D. G. (2021). Parental buffering of stress in the time of COVID-19: Family-level factors may moderate the association between pandemic-related stress and youth symptomatology. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00732-6

- Corona, Y. C., & Zavala, C. P. (2002). Resistencia e identidad como estrategias para la reproducción cultural. Anuario de Investigación, 2, 57.

- Cortés-García, L., Hernández Ortiz, J., Asim, N., Sales, M., Villareal, R., Penner, F., & Sharp, C. (2021). COVID-19 conversations: A qualitative study of majority Hispanic/Latinx youth experiences during early stages of the pandemic. Child & Youth Care Forum, 1, 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09653-x

- Crawford, L. A., & Novak, K. B. (2006). Alcohol abuse as a rite of passage: The effect of beliefs about alcohol and the college experience on undergraduates’ drinking behaviors. Journal of Drug Education, 36(3), 193–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2190/F0X7-H765-6221-G742

- De Los Reyes, A. (2021). (Second) inaugural editorial: How the Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology can nurture team science approaches to addressing burning questions about mental health. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1858839

- De Los Reyes, A., Talbott, E., Power, T., Michel, J., Cook, C. R., Racz, S. J., & Fitzpatrick, O. (2022). The Needs-to-Goals Gap: How informant discrepancies in youth mental health assessments impact service delivery. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, 102114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102114

- Del Río-González, A. M., Holt, S. L., & Bowleg, L. (2021). Powering and structuring intersectionality: Beyond main and interactive associations. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(1), 33–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00720-w

- Desai, S. R. (2020). Remembering and honoring the dead: Día de los Muertos, Black Lives Matter and radical healing. Race Ethnicity and Education, 23(6), 767–783. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2020.1798391

- Diaz-Cabello, N. (2004). The Hispanic way of dying: Three families, three perspectives, three cultures. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 12(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1054137304265757

- Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029

- Eales, L., Ferguson, G. M., Gillespie, S., Smoyer, S., & Carlson, S. M. (2021). Family resilience and psychological distress in the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1563–1581. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001221

- Echeverría, E. (1994). Tepoztlán, ¡Que viva la fiesta!. Dirección General de Culturas Populares. Unidad Regional Morelos.

- Enari, D., & Rangiwai, B. W. (2021). Digital innovation and funeral practices: Māori and Samoan perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(2), 346–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801211015568

- Forth, G. (2018). Rites of passage. In H. Callan (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of anthropology (pp. 1–7). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- French, B. H., Lewis, J. A., Mosley, D. V., Adames, H. Y., Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Chen, G. A., & Neville, H. A. (2020). Toward a psychological framework of radical healing in communities of color. The Counseling Psychologist, 48(1), 14–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000019843506

- Fuentes, M. A., Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Tineo, P., Gonzalez, K., & Butt, M. (2021). Skin color matters in the Latinx community: A call for action in research, training, and practice. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 0739986321995910. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/073998.63219.95910

- García Coll, C., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., McAdoo, H. P., Crnic, K., Wasik, B., & García, H. V. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1131600

- Garcini, L. M., Brown, R. L., Chen, M. A., Saucedo, L., Fite, A. M., Ye, P., Ziauddin, K., & Fagundes, C. P. (2019). Bereavement among widowed Latinos in the United States: A systematic review of methodology and findings. Death Studies, 45(5), 342–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1648328

- Gee, G. C., & Ford, C. L. (2011). Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 8(1), 115–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X11000130

- Gilligan, M., Suitor, J. J., Rurka, M., & Silverstein, M. (2020). Multigenerational social support in the face of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(4), 431–447. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12397

- Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family: Social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 243–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131650

- Hannah-Jones, N. (2021). The 1619 project: A new origin story. One World.

- Harvey, A. R., & Rauch, J. B. (1997). A comprehensive Afrocentric rites of passage program for black male adolescents. Health & Social Work, 22(1), 30–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/22.1.30

- Harvey, A. R., & Hill, R. B. (2004). Africentric youth and family rites of passage program: Promoting resilience among at-risk African American youths. Social Work, 49(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/49.1.65

- Hernández‐Fernández, C., & Meneses‐Falcón, C. (2021). I can’t believe they are dead. Death and mourning in the absence of goodbyes during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Health & Social Care in the Community. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13530

- Hillis, S. D., Blenkinsop, A., Villaveces, A., Annor, F. B., Liburd, L., Massetti, G. M., …Unwin, H. J. T. (2021). COVID-19–associated orphanhood and caregiver death in the United States. Pediatrics, 148(6). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053760

- Hobson, N. M., Schroeder, J., Risen, J. L., Xygalatas, D., & Inzlicht, M. (2018). The psychology of rituals: An integrative review and process-based framework. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(3), 260–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/10888.68317.734944

- Huang, K. (2021). China’s stay-at-home Lunar New Year a welcome break from tradition for many. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3121239/chinas-stay-home-lunar-new-year-welcome-break-tradition-many

- INEGI. (2021). Estadísticas a Propósito del día internacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (9 De Agosto). https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/aproposito/2020/indigenas2020.pdf

- John-Henderson, N. A., & Ginty, A. T. (2020). Historical trauma and social support as predictors of psychological stress responses in American Indian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 139, 110263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110263

- Johns, L., Blackburn, P., & McAuliffe, D. (2020). COVID-19, prolonged grief disorder and the role of social work. International Social Work, 63(5), 660–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820941032

- Jones, J. (1972). Prejudice and racism. Addison Wesley.

- Jones, S. C., & Neblett, E. W. (2017). Future directions in research on racism-related stress and racial-ethnic protective factors for Black youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(5), 754–766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1146991

- Kagitcibasi, C. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in cultural context: Implications for self and family. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36(4), 403–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275959

- Kagitcibasi, C., & Ataca, B. (2005). Value of Children and Family Change: A Three-Decade Portrait From Turkey. Applied Psychology, 54(3), 317–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00213.x

- Kapitány, R., & Nielsen, M. (2015). Adopting the ritual stance: The role of opacity and context in ritual and everyday actions. Cognition, 145, 13–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.08.002

- Kavanagh, C. (2018). Ritual and cognition. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology (pp. 1–7). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Kılınçel, Ş., Kılınçel, O., Muratdağı, G., Aydın, A., & Usta, M. B. (2021). Factors affecting the anxiety levels of adolescents in home-quarantine during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 13(2), e12406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12406

- King, M. B. (2020). Black student excellence springs from historic inequalities. Racism: An Educational Series. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/black-history/9/

- Korous, K. M., Causadias, J. M., Bradley, R. H., & Luthar, S. S. (2018). Unpacking the link between socioeconomic status and behavior problems: A second-order meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 30(5), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579418001141

- Kreinath, J. (2018). Ritual. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- La Fontaine, J. S. (2018). Initiation. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Lee, C. M., Cadigan, J. M., & Rhew, I. C. (2020). Increases in loneliness among young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic and association with increases in mental health problems. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 714–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.009

- Lee, B. A., Ogunfemi, N., Neville, H. A., & Tettegah, S. (2021). Resistance and restoration: Healing research methodologies for the global majority. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000394

- Legare, C. H., & Nielsen, M. (2020). Ritual explained: Interdisciplinary answers to Tinbergen’s four questions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375(1805), 20190419. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0419

- Li, C. (2006). The Confucian Ideal of Harmony. Philosophy East and West, 56(4), 583–603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/pew.2006.0055

- McCallum, C. (2017). Giving back to the community: How African Americans envision utilizing their PhD. The Journal of Negro Education, 86(2), 138–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.86.2.0138

- Neblett, E. W., Jr, Rivas‐Drake, D., & Umaña‐Taylor, A. J. (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x

- Neblett, E. W., Jr. (2019). Racism and health: Challenges and future directions in behavioral and psychological research. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000253

- Noe-Bustamante, L., Mora, L., & Lopez, M. H. (2020). About one-in-four US Hispanics have heard of Latinx, but just 3% use it. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it/

- Özer, Ö., Özkan, O., Budak, F., & Özmen, S. (2021). Does social support affect perceived stress? A research during the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 31(1–4), 134–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2020.1854141

- Perez-Brena, N. J., Wheeler, L. A., De Jesús, S. A. R., Updegraff, K. A., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2017). The educational and career adjustment of Mexican-origin youth in the context of the 2007/2008 economic recession. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 100, 149–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.02.006

- Prichep, D. (2022). The Bat Mitzvah turns 100. It marks more than a coming-of-age for Jewish girls. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/03/17/1086733010/bat-mitzvah-turns-100-coming-of-age-jewish-girls

- Racine, N., McArthur, B. A., Cooke, J. E., Eirich, R., Zhu, J., & Madigan, S. (2021). Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(11), 1142–1150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482

- Romo, L. F., Mireles-Rios, R., & Lopez-Tello, G. (2014). Latina mothers’ and daughters’ expectations for autonomy at age 15 (La Quinceañera). Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(2), 271–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558413477199

- Ross, N., & Kohut, M. (2018). Evolution of ritual and religion. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sanchez, A. L., Jent, J., Aggarwal, N. K., Chavira, D., Coxe, S., Garcia, D., La Roche, M., & Comer, J. S. (2022). Person-centered cultural assessment can improve child mental health service engagement and outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2021.1981340

- Santini, O. (2017). Five Quinceañeras shine in new HBO series ‘15: A Quinceañera Story.’ NBC news. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/five-quincea-eras-shine-new-hbo-series-15-quincea-era-n831336

- Spencer, M. B. (2006). Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Editors-in-Chief), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed, pp. 829–893). Wiley. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0115

- Stein, G. L., Cupito, A. M., Mendez, J. L., Prandoni, J., Huq, N., & Westerberg, D. (2014). Familism through a developmental lens. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(4), 224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000025

- Tan, Y. (2021). Chinese New Year: Clamping down on going home for the holidays BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-55791858