Abstract

The BODE group designed a bubble chart, analogous to the solar system, which depicts the prevalence of each disease and its association with mortality and called it a “comorbidome”. Although this graph was used to represent mortality and, later, the risk of needing hospital admission, it was not applied to visualize the association between a set of comorbidities and the categories of the GOLD 2017 guidelines, neither according to the degree of dyspnea nor to the risk of exacerbation. For the purpose of knowing to which extent each comorbidity associates with each of the two conditions—most symptomatic group (groups B and D) and highest risk of exacerbation (groups C and D)—we performed a analysis based on the comorbidome. 439 patients were included. Cardiovascular comorbidity (especially cardiac and renal disease) is predominantly observed in patients with a higher degree of dyspnea, whereas bronchial asthma and stroke occur more frequently in subjects at higher risk of exacerbation. This is the first time that the comorbidome is presented based on the categories of the GOLD 2017 document, which we hope will serve as a stimulus for scientific debate.

To the Editors:

Recently, our group reported that particularly the cardiovascular and psychiatric comorbidities have a negative impact on health-related quality of life (quantified by the COMCOLD index) in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). They affect even more the symptomatic subjects, as defined by the GOLD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease) 2017 classification (Citation1). Likewise, that article revealed that distinct comorbidities are related in different ways, so that when analyzing the more symptomatic patients, their distribution deviates from that of the patients with a greater risk of exacerbation.

Divo et al. (Citation2) found that lung, esophagus, breast and pancreas cancer, liver cirrhosis, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, diabetic neuropathy, pulmonary fibrosis, congestive heart failure, gastroduodenal ulcer, and anxiety were the pathologies with the greatest impact on the vital prognosis of patients with COPD. Based on these findings, the BODE group designed a bubble chart, analogous to the solar system, which depicts the prevalence of each disease and its association with mortality and called it a "comorbidome". Although this graph was used to represent mortality (Citation2, Citation3) and, later, the risk of needing hospital admission (Citation4), it was not applied to visualize the association between a set of comorbidities and the categories of the GOLD 2017 document, neither according to the degree of dyspnea nor to the risk of exacerbation (Citation5).

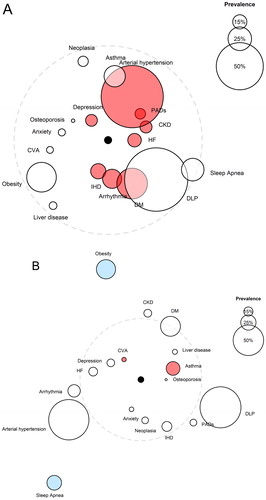

For the purpose of knowing to which extent each comorbidity associates with each of the two conditions—most symptomatic group and highest risk of exacerbation—we performed a sub-analysis based on the comorbidome by Divo et al. (Citation2), where the circle diameter expresses the prevalence of the distinct comorbidities in percent. Distances of the circles to the center stand for the risk of either belonging to the most symptomatic groups, with a degree of dyspnea ≥2, according to the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale (groups B and D), or to the groups at highest risk of exacerbation (Groups C and D), based on the numerical value of the odds ratio (OR) (). The same sample base (Citation1) was used to calculate the ORcrude for each of the diseases both for symptomatic patients and for patients at greater risk of exacerbation (groups C and D). In the original study, ORs had been calculated to determine the risk of having comorbidity, using two variables from the GOLD 2017 document, i.e. dyspnea and the number or severity of exacerbations in the previous year, as independent, predictive values.

Figure 1. The COPD comorbidome in the light of the degree of dyspnea and risk of exacerbation. The comorbidome is a graphic expression of comorbidities with more than 5% prevalence in the entire cohort. The areas inside the circles relate to the disease prevalence. (A) Proximity to the center (black point) expresses the strength of the disease–risk of dyspnea association, evaluated using the mMRC (modified Medical Research Council) scale ≥2 (groups B and D). (B) Proximity to the center (black point) expresses the strength of the disease–risk of exacerbation association (groups C and D). This was scaled from the inverse of the OR. Dashed line: OR = 1; outside dashed line: OR <1. Red circles represent statistically significant associations (OR >1; p <0.05); blue circles represent statistically significant, inversely associated (OR <1; p <0.05). HF: Heart failure; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; IHD: Ischemic heart disease; CVA: Cerebrovascular accidents; DM: Diabetes mellitus; DLP: Dyslipidemia; PAD: Peripheral arterial disease.

The analyzed comorbidities depression, peripheral arterial disease, heart disease, arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic kidney disease exhibited the strongest relation to grade ≥2 dyspnea (groups B and D). Accumulating evidence supports that psychiatric illness as well as heart disease exert a relevant influence on the symptomatology of our patients with COPD (Citation6–9). Data obtained from the ECLIPSE cohort revealed that patients with COPD and cardiovascular disease, arterial hypertension, or diabetes mellitus had a higher score of dyspnea and a decreased walking distance in the 6-minute walk test (Citation9). As to chronic kidney disease, pulmonary edema—as the result of a combination of volume overload, low oncotic pressure, reduced cardiovascular reserve, and coexisting, manifest heart failure—as well as sarcopenia (Citation10, Citation11) are known to potentially affect dyspnea in our patients.

The increased risk of exacerbation (in groups C and D) was mostly associated with the comorbidities cerebrovascular accidents and bronchial asthma. In agreement with our findings, Kim et al. (Citation12) reported recently that patients with asthma–chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap (ACO) had more visits to the emergency room and hospital admissions than patients with COPD without concomitant asthma. Moreover, various studies have described that patients with COPD show a higher incidence of cerebrovascular accidents (Citation13–15), particularly those who suffer frequent exacerbations (Citation16). Conversely, we have detected that the comorbidities obesity and sleep apnea reduced the risk of exacerbation. Although a low body mass index is associated with an increased risk of hospitalization in patients with COPD (Citation17), assessment of the impact of obesity on the risk of exacerbation leads to disparate results (Citation18, Citation19). Marín et al. (Citation20) described that patients with overlap syndrome of sleep apnea and COPD, without continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment, had an increased risk of exacerbation requiring hospital admission, a phenomenon that was corrected upon starting CPAP treatment. The effect observed in our sample may stems from the large number of patients treated with this device, which in turn may have influenced the data obtained in relation to obesity, given the strong association between the two entities (Citation21).

The current work coincides in its limitations with those of the original article (Citation1). Our analysis shows that the comorbidities interfere differentially in both groups, resulting in case-dependent, distinct scenarios. Cardiovascular comorbidity (especially cardiac and renal disease) is predominantly observed in patients with a higher degree of dyspnea, whereas bronchial asthma and stroke occur more frequently in subjects at higher risk of exacerbation. This is the first time that the comorbidome is presented based on the categories of the GOLD 2017 document, which we hope will serve as a stimulus for scientific debate.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Figueira Gonçalves JM, Martín Martínez MD, Pérez Méndez LI, García Bello MA, Garcia-Talavera I, Hernández SG, et al. Health status in patients with COPD according to GOLD 2017 classification: use of the COMCOLD Score in routine clinical practice. COPD. 2018:15;326–33.

- Divo M, Cote C, de Torres JP, Casanova C, Marin JM, Pinto-Plata V, Zulueta J, Cabrera C, Zagaceta J, Hunninghake G, et al. Comorbidities and risk of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:155–61

- Almagro P, Cabrera FJ, Diez J, Boixeda R, Alonso Ortiz MB, Murio C, Soriano JB. Comorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: The EPOC En Servicios de Medicina Interna (ESMI) study. Chest. 2012;142:1126–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2413.

- van Boven JF, Román-Rodríguez M, Palmer JF, Toledo-Pons N, Cosío BG, Soriano JB. Comorbidome, pattern, and impact of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome in real life. Chest. 2016;149:1011–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.002.

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD); 2017. http://www.goldcopd.org.

- Ng TP, Niti M, Tan WC, Cao Z, Ong KC, Eng P. Depressive symptoms and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: effect on mortality, hospital readmission, symptom burden, functional status, and quality of life. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:60e7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.1.60.

- Patel ARC, Donaldson GC, Mackay AJ, Wedzicha JA, Hurst JR. The impact of ischemic heart disease on symptoms, health status, and exacerbations inpatients with COPD. Chest. 2012;141:851–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0853.

- Kahnert K, Alter P, Young D, Lucke T, Heinrich J, Huber RM, Behr J, Wacker M, Biertz F, Watz H, et al. The revised GOLD 2017 COPD categorization in relation to comorbidities. Respir Med. 2018;134:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.12.003.

- Miller J, Edwards LD, Agustí A, Bakke P, Calverley PM, Celli B, Coxson HO, Crim C, Lomas DA, Miller BE, et al. Comorbidity, systemic inflammation and outcomes in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Med. 2013;107:1376–84. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.05.001.

- Ting SM, Hamborg T, McGregor G, Oxborough D, Lim K, Koganti S, Aldridge N, Imray C, Bland R, Fletcher S, et al. Reduced cardiovascular Reserve in Chronic Kidney Failure: a matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:274–84. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.02.335.

- Vanfleteren LE, Spruit MA, Groenen M, Gaffron S, van Empel VP, Bruijnzeel PL, Rutten EP, Op 't Roodt J, Wouters EF, Franssen FM. Clusters of comorbidities based on validated objective measurements and systemic inflammation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:728–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1665OC.

- Kim M, Tillis W, Patel P, Davis RM, Asche CV. Association between asthma-COPD overlap syndrome and healthcare utilizations among US adult population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019: 1–6.

- Söderholm M, Inghammar M, Hedblad B, Egesten A, Engström G. Incidence of stroke and stroke subtypes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:159–68. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0113-7.

- Portegies ML, Lahousse L, Joos GF, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Stricker BH, Brusselle GG, Ikram MA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of stroke. The Rotterdam Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:251–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0962OC.

- Kim YR, Hwang IC, Lee YJ, Ham EB, Park DK, Kim S. Stroke risk among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e177.

- Lin CS, Shih CC, Yeh CC, Hu CJ, Chung CL, Chen TL, Liao CC. Risk of Stroke and Post-Stroke Adverse Events in Patients with Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169429.

- Çolak Y, Afzal S, Lange P, Nordestgaard BG. High body mass index and risk of exacerbations and pneumonias in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: observational and genetic risk estimates from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45:1551–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw051.

- Jo YS, Kim YH, Lee JY, Kim K, Jung KS, Yoo KH, Rhee CK. Impact of BMI on exacerbation and medical care expenses in subjects with mild to moderate airflow obstruction. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2018;13:2261–9. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S163000.

- Lambert AA, Putcha N, Drummond MB, Boriek AM, Hanania NA, Kim V, Kinney GL, McDonald MN, Brigham EP, Wise RA, et al. Obesity is associated with increased morbidity in moderate to severe COPD. Chest. 2017;151:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1432.

- Marin JM, Soriano JB, Carrizo SJ, Boldova A, Celli BR. Outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obstructive sleep apnea: the overlap syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:325–31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1869OC.

- Steveling EH, Clarenbach CF, Miedinger D, Enz C, Dürr S, Maier S, Sievi N, Zogg S, Leuppi JD, Kohler M. Predictors of the overlap syndrome and its association with comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration.2014;88:451–7. doi: 10.1159/000368615.