Abstract

It is no surprise that concern for the future is on the rise. Several catastrophes obscure our future(s) imaginary, such as climate change, a global pandemic, racial inequality, and political polarization. Students are feeling a disconnect between what they learn in classrooms and the futures that populate their media platforms. Futures literacies provides one proposed pedagogical intervention that takes up future(s) possibility as a context for inquiry across the disciplines. Building upon and extending from the discipline of futures studies, which involves inquiry into possible, probable, and preferable futures through social and technological advancements, futures literacies refers to the ways we perceive, sense, enact, envision, and create the future in the present. In this interdisciplinary review, we synthesize research that investigates the ways humans engage with future potentiality, moving toward an expansive model of futures literacies and mapping generative connections between literacy research and other discourses including futures studies scholarship.

Re-imagining the future

While concern for the future is not new, it is not surprising that the future contains a new sense of immediacy. A global pandemic has swept the world, promising any number of reverberating sociocultural consequences. Climate change entangles with human politics to create an array of probable future disasters. Our technologies proliferate at an ever-increasing rate, inspiring for some the hope of a technological utopian solution to all our problems, and for others, the existential despair that technology has become our ultimate problem. The futures that we read in the tea leaves of our present circumstances contain powerful and performative sway in the way things unfold in the future present. As Polak (Citation1961) wrote, “the future lies concealed in today’s images of the future” (p. 8). History, he argued, can be read as “a succession of acts of the imagination, subsequently inspiring social action in the direction of the imagined” (cited in Boulding, Citation1988, p. 116). While we cannot know or predict which “acts of the imagination” will take hold in future reality, nor how these imaginings will be enacted, futures studies scholars assert that we must cultivate our capacity to imagine the future to tip the scales toward preferred future outcomes.

The concept of futures as a literacy has gained increased traction outside of literacy discourses, touted as a necessary capability that may provide a solution to “poverty-of-the-imagination” (Futures Literacy, n.d., UNESCO). When examining the potential educational benefits of a futures literacies pedagogy, it is also important to make transparent the embedded views of what literacy(ies) are and do. Conceptualizations of literacy have shifted over the years from a focus on reading and writing as discrete skills to broader perspectives of literacies as social practices performed by people in their daily lives (e.g., The New London Group, Citation1996), or as affectively saturated (e.g., Truman et al., Citation2021), or as entangled inextricably with the material world (e.g., Burnett & Merchant, Citation2021) and posthuman agencies (e.g., Kuby & Rowsell, Citation2017). Literacy researchers are aware that views of literacy impact how we think about learners, what and how they learn, and how this all might be achieved in terms of pedagogical practices and curriculum design (Perry, Citation2012). Literacy scholars have further identified the politics and historical legacies of Western colonialist literacy education programs (e.g., Wickens & Sandlin, Citation2007), promoting neoliberal definitions of literacy that are tied to the labor force and productivity.

One of the purposes of this review is to create generative pathways between literacy discourses and futures studies. Similar to how futures studies can benefit from integrating progressive understandings of literacy, literacy scholarship might be enriched by the vast futures-oriented research and thinking outside of the discipline. For instance, in their work exploring 21st-century literacies pedagogy, Knobel and Lankshear (Citation2014) articulate the need to anticipate beyond the present to enhance learners’ capacities for meaning-making in the future. However, they refrain from engaging with specific processes of anticipation or how to envisage educational practices for the future. Scholars in the New London Group reminded us that education should prepare students to be “designers of their social future” (Anstey & Bull, Citation2018, p. 16)—regardless of a dearth of explicit practices of how students can become “designers.” Curriculum scholars like Bobbitt (Citation2004) have argued we need “new methods, new materials, new vision” (p. 9) for education as the world continues to hurtle into the future. While the future has been a projected outcome of our literacy practices and schooling more broadly, rarely has it been the focus and context, the process by which we might become over time in doing literacy. This review aims to demonstrate interdisciplinary approaches to centering futures as the productive focal point of literacy practice.

Advocates and critics of Futures

The term futures contains many meanings. It can refer to futures studies as an established discipline with a recognizable knowledge base built upon methods and practices dating back to the early 20th century (Sardar, Citation2010). Futures can simply outline multiple pathways forward, verses a single course of action, and can be considered synonymous with possibility. Augé (Citation2014) referred to the future in singular form but used it in a variegated sense to indicate a time of conjunction—a forging together of temporal and subjective multiplicities. Futures can also signify a bought and sold commodity, enticing big business and corporations (including those in education) who wish to construct and profit from certain narratives of the future over others. In this review, we take up futures in the plural form to indicate an open and undetermined temporal unfolding, a space of possibility. We also acknowledge this “openness” is a deeply contested political and onto-epistemological affair. Possibility is neither universal nor distributed evenly.

Some scholars have, for instance, problematized the concept of futurity as an always and already colonized, Anthropocentric, Westernized, and white-washed imaginary. Antiblackness (e.g., Jackson, Citation2020; Lethabo-King et al., Citation2020), racial realism, and the concept of “fugitivity” and “maroon communities” (e.g., Harney & Moten, Citation2013) all work in different ways toward resisting white futurity and building future difference rooted in Black liberation. These scholars assert that our narratives of humanity (Wynter & McKittrick, Citation2020) are inherently antiblack and cannot be the basis of a just futurity. Afropessimism (e.g., ross, Citation2019) therefore problematizes futures imagining, asserting how “epistemologically impossible” it can be “to imagine an alternative Human world” because “the antagonist of the Black is the Human” (Wilderson, Citation2021, p. 39) and “the future is what happens when one is not Black” (p. 50).

Indigenous Anti-futurists (2020) have identified how global futures are “built upon genocide, enslavement, ecocide, and total ruination” (para. 4). Imagining preferable futures from an historical and extant colonial paradigm reifies an extended future of colonization. Instead, there is a call for ending futurity thereby enabling a “re-emergence of the world of cycles” (para. 25). In No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Edelman (Citation2004) similarly rejects the entire social order emerging from previous concepts of futurity because of their reproductive hegemony via the image of the Child. McRuer (Citation2017) describes a “certain strand of ‘anti-futural’ thinking” (p. 69) in the field of disability studies, which extends upon Edelmen’s argument to include “crip” resistance to “hegemonic, able-bodied notions of futurity” (p. 70). In addition to these refutations of futurity, posthumanism questions the necessary existence of humanity upon a troubled planet. Perhaps, as Colebrook (Citation2016) suggests, there is a future without humans that could also “elicit joy” (p. 206).

With a multiple futures literacies perspective, we wish to foreground a rich multiplicity of both futures and anti-futures thinking—allowing for conflicting and contradictory images of possibility, openness, and hope. The project of futures literacies extends beyond some of the challenges embedded in notions of futurity, particularly those rooted in patriarchal, hetero-normative, and colonialist paradigms, and which serves as a critique and provocation against how conceptual Western educational spaces have been historically used to further marginalize others. We consider how any conception of the future(s) can and should be interrogated and complexified if we are to engage in critical and decolonized futures literacies practices.

Methodology

This review explores how futures are being conceptualized, theorized, and empirically studied as a focal point of meaning-making practices, phenomenological experience, and knowledge creation across a variety of disciplines. In drawing together this diverse range of qualitative research and theory toward an expansive vision of what futures literacies might be and do across the curriculum, we employed an integrative review methodology, one that integrates and synthesizes extant frameworks of literature to generate new perspectives (Torraco, Citation2005). We endeavored to reveal emergent possibilities within an assemblage of perspectives, simultaneously acknowledging the researcher as an existing part of the apparatus measuring and analyzing in specific geopolitical circumstances (Murris & Bozalek, Citation2019). We bring our positionalities as settler Canadians and literacy scholars whose interdisciplinary arts-based qualitative research resonates with a futures literacies perspective.

This review took place from June 2020 to July 2021 (and continued to be refined and augmented during the review process). We began with futures literacy as a broad search term utilizing Google Scholar and Summon, our institution’s generalized search engine which has access to almost 1,000 databases as well as the institution’s own collection of resources. This search returned nearly 2,000 peer reviewed publications. We sorted the top results, discarding any study where the terms futures or literacy explored other topical areas. As we became acclimatized to the different descriptions and placements of futures literacies across the disciplines, we began to recognize overlap with other critical literacies, such as technological literacies, 21st-century literacies, and historical literacies. We expanded our search to include terms with analogous counterparts in historical pedagogy, including futures thinking, futures fluency, and futures consciousness. These search terms expanded our results exponentially.

Given the sheer volume of applicable results and the need to continually re-orient ourselves back to a coherent view of the complex dynamics of literacy practices, we developed a taxonomical statement that allowed us to identify and map discrete elements of literacy with an explicit futures focus across a diverse range of settings: literacy practices involve subjectivities in a context who employ meaning-making practices to understand and create texts via media for a reason. The distinction between categories in this taxonomy are obviously problematic and artificial, especially from a posthumanist or new materialist lens, which sees these categories as mutually entangled and co-generative.

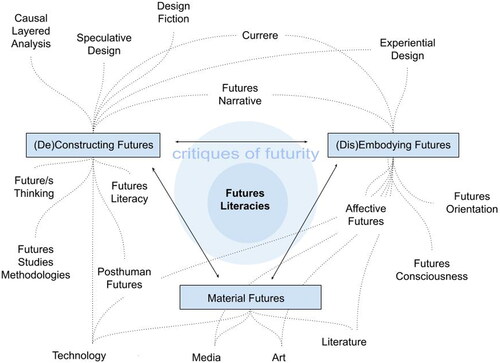

For the purposes of this discussion, we have organized the literature into three sections: (De)Constructing Futures (meaning-making practices) or the “how” of futures literacies; (Dis)Embodying Futures (subjectivities) or the “who” of futures literacies’ and Material Futures (texts and media); or the “what” of futures literacies. We have highlighted pedagogical contexts and reasons for futures literacies throughout the paper and discussion section. (See for a concept map of the organizational structure of the interrelated themes covered in this review). Results included: 31 books, 2 dissertations, 11 online resources, and 69 journal articles, including 24 empirical studies, 43 theoretical papers (including a variety of methodological frameworks, essays, and analysis of the various fields), and 2 comprehensive literature reviews.

(De)Constructing futures: Making meaning with/of/for the future

This section explores research and theorizing on futuring strategies, skills, processes, and methodologies of futures knowledge production. We report on findings that explore the cognitive dynamics of thinking about the future in ways that are pedagogically meaningful, including scholarship and research on Futures Literacy, futures thinking, and futures narrative as a design methodology.

Futures literacy

Anticipation studies, described by Poli (Citation2017) as the third level of futures studies following forecasting and foresight modeling, focuses on future-generating research—shifting the scientific/analytic gaze away from representation and instead aiming to find and create difference. Forecasting and foresight are future-oriented practices that provide a cause-and-effect analysis that seeks to extrapolate from circumstances in the present to engage in informed and methodological reasoning about an unfolding future. These first two levels of futures studies conceptualize future effects as necessary consequences of present causes. Within this ontological lens, futurity is inherently reactive, with the goal to mediate for or capitalize upon the inevitable. This approach to causation, however, can serve to replicate social patterns and systems unintentionally and uncritically from the past into the future. Anticipation studies makes a purposeful shift away from a determinist view of inevitable outcomes based upon current systems, toward a more productive and generative practice of performing and enacting difference.

Over the last 15 years, Miller (Citation2007; Citation2015; Citation2018) has developed an extensive model of Futures Literacy (FL) based upon research in anticipation studies that enumerates human “sensing and making-sense” capacities of anticipation (Miller, Citation2018, p. 95). As head of the Global Futures Literacy Network at UNESCO, Miller and his team have been “pioneering advances in the theory & practice of using the future as a means to improve management & public policy, with a focus on transformational leadership (Miller, Citationn.d.). Miller’s framework takes up futures meaning-making practices with an outcome-based approach that is practical in matters of public policy and organizational studies (Rhisiart et al., Citation2015). Drawing on normative models of literacy, Miller’s (Citation2018) FL describes a set of practices and skills for “using-the-future” toward enumerating and enacting identified future goals.

Miller’s FL framework has been used widely in such contexts as imagining Antarctic futures (Frame, Citation2019), building futures thinking in New Zealand (Pride et al., Citation2010), and increasing dynamic elements of corporate firms (Rhisiart et al., Citation2015). FL has been combined with other futures methodologies, such as Ketonen-Oksi (Citation2018), who incorporated Inayatullah’s (Citation1998) Causal Layered Analysis to examine the collective subjectivity involved in meaning-making and value-creation within “real life business environments” (p. 1). Cagnin (Citation2018) focussed similarly on participatory and collaborative meaning-making in the organizational context, but here she integrated design thinking into FL methodology that allowed for collective discoveries of business models. While Miller’s FL has much to offer learners in a variety of different contexts, particularly in the ambassadorial role of global distribution of futures studies knowledge through UNESCO, this framework and methodology has largely been operationalized in organizational, institutional, governmental, and corporate discourses.

Loosening the close association FL (and futures studies in general) currently has with certain corporate and neoliberal positivist ideologies presents one of the interventions of a multiple futures literacies perspective. Indeed, Urry (Citation2016) warned against becoming corporate futurists—supporting business thinktanks that seek to corporatize the future. FL has been additionally criticized for a narrow view of literacy that relegates all those without the appropriate anticipatory skills as being “futures illiterate.” Facer and Sriprakash (Citation2021) cautioned against the codification of FL thereby ignoring the “specific and abundant variety” of futures literacies already existing in the lives of students (p. 7).

Future(s) thinking

The human capacity to think about the future and calibrate behavior accordingly has been widely researched across the field of psychology in connection with indicators like achievement, proactive coping, adaptation, and aging (e.g., Aspinwall, Citation2005). In the discipline of futures studies, scholars like Inayatullah (Citation2008) use futures thinking processes as a methodology for individuals and organizations to enact preferential change. Inayatullah’s pillars of futures thinking provide a methodological framework for deconstructing “the world we think we may want” and identifying more wholistic and beneficial collaborative futures (p. 6). In an educational context, Bengston (Citation2017; Citation2018) outlined how a systematic approach to activating the futures imagination can help learners think productively about the future while also anticipating and preparing for uncertainty. Vidergor (Citation2018) similarly advocated for the uptake of explicit futures thinking in secondary school curriculums across all disciplines. She designed a multidimensional curricular model for integrating futures thinking and literacy in Israeli schools. Futures thinking for Vidergor builds upon neurophysiological and psychological research that considers the ability to engage in mental time travel, make predictions, and perform other future-oriented cognitive processes. Her approach to futures thinking as a literacy combines futures thinking awareness with scientific and creative thinking. The historian Staley (Citation2002; Citation2007) argued that both futures thinking and historical thinking are predicated upon finding patterns in the evidence. Staley suggested techniques of historical thinking can be utilized in exploring the future imaginary. Counterfactual historical thinking, for example, is analogous to building alternative futures scenarios—both techniques explore alternative pathways that stem from contingent events.

Futures narrative

Because narrative captures intrinsically how humans make and find meaning across experiences in time and space, it exists in many futures methodologies. For example, narrative creates purpose, continuity, and causal coherence among and between a series of events (Goodson & Gill, Citation2014), as well as providing opportunities for rewriting possible futures through modes of storytelling in the present (Gladwin, Citation2021). Akin to narrative inquiry (i.e., Clandinin, Citation2007), a methodology used in education and literacy research as a method for understanding the nature of human experience, futures narrative provides a means of exploring the future unknown (Horst, Citation2021). In their literature review, Hofvenschioeld and Khodadadi (Citation2020) highlighted narrative as one of the more dominant discourses in the futures studies literature both in terms of the communication of study results and as a participatory methodology for imagining and enacting futures. In this section, we explore the latter methodological use of narrative as a “future forming” modality (Gergen, Citation2015).

In Facer’s (Citation2019) research on educational futures and social change, she pointed out how encouraging students to create, share, and listen to stories about their imagined futures allows them to articulate their fears, desires, hopes, and dreams while engaging in the complexity of the present. Enciso (Citation2019) studied futures storytelling among immigrant and nonimmigrant children, advocating for a “future-oriented literacy pedagogy” that uses narrative as a means of reclaiming and reframing inequitable world discourses. In curriculum studies, Pinar’s (Citation1994) widely taken up currere methodology guides educators toward deeper understandings of their lifelong educational experience. The second of four stages in the journey outlines an imagined exploration of future intellectual interests, future relationships with students, and how these educational futurities connect with history. In the Analytic stage, Pinar asks the educator, “How is the future present in the past, the past in the future, and the present in both?” (p. 26).

Narrative analysis permeates a widely used futures research methodology known as Causal Layered Analysis (CLA), which Inayatullah (Citation1998) developed to create transformative environments for imagining alternative futures. CLA consists of four layers, including litany, social cause, discourse, and myth/metaphor. The final layer explores “the deep stories” and “collective archetypes” embedded in identified futures-related problems. The aim of CLA is to “undefine” the future and make space for a diversity of future imaginaries (p. 816).

Design and technological innovation are areas that have increasingly drawn upon futures narrative as a methodology. Major multi-national corporations like Ford and Visa, as well as governmental organizations like NATO, hire science fiction writers to create futures contexts and imagine the possible technologies in those narratives (Underwood, Citation2020, para. 2). As Johnson (Citation2011), creator of science fiction prototyping methodology, observed, “now all any of us have to do is imagine it and we can build it” (quoted by Maheshwari, Citation2013, para. 14). Speculative design (Dunne & Raby, Citation2013) is a methodology for dealing with “wicked problems” and provides an imaginative venue for “collectively redefining our relationship to reality” (p. 2). A design futures literacies perspective (Morrison et al., Citation2020; Clèries & Morrison, Citation2020) engages multimodal forms of narrative production with the aim of fostering critical quotidian “thinking and action for, and in, the future” (Morrison & Chisin, Citation2017, p. 110). Other examples of narrative as a futuring methodology are design fiction (Bleecker, Citation2009; Markussen & Knutz, Citation2013), science fiction prototyping (Bell et al., Citation2013; Draudt et al., Citation2015), and experiential futures scenarios (Candy, Citation2010; Candy & Dunagan, Citation2017). These methodologies can be found in various settings, from schools (Lane & Solis, Citation2019) to engaging the public in the future of generative biology (Ahmedien, Citation2020).

In a recent study exploring the role of narrative in developing FL, Liveley et al. (Citation2021) argued that any view of a futures literacy should draw upon the wealth of competencies and skills developed and refined in literacy criticism. The authors highlight the unusual paradox that futures studies scholars often overlook literary genres, such as science fiction, climate fiction, or speculative fiction as methodologies for serious futures exploration, because of the perception of literature as an imagined text disconnected from potential realities. In educational discourses, alternatively, science fiction and speculative fiction genres (see also Material Futures) find pedagogical and curricular alignment (Weaver, Citation2019). Gough (Citation2017) proposed including science fiction literature in science curriculums with the goal of taking a critical stance and generating inquiry questions that challenge the dominant discourses of contemporary science education (p. 790). Elsewhere, Truman (Citation2019) underscores how the speculative fiction of marginalized students confronts the “white space of mainstream speculative worlding” (p. 37). She was particularly interested in how students’ situated knowledge and identities came to shape and inform their creative futures imagining. Burdick (Citation2019) explores narrative-based fiction to explore the subjective and quotidian aspects of human-scaled futurity. Of all the themes covered in this review, futures narrative is perhaps the most difficult to categorize. Whether we define them as literature, art, heuristic, thought experiment, or method, futures narratives provide pathways into and maps of the future unreal. As a methodological tool, futures narratives allow us to imaginatively construct and deconstruct the contours of futures possibility. Experientially—in both the writing (method) and the reading (text)—futures narratives allow us to embody imagined futures (Horst, Citation2021), giving possibility a visceral and immediate place in the present.

Three broad themes emerged from a synthesis of the literature in this section: (1) Kinds of futures concerned with whether we conceive of the future as near or far, circular or linear, knowable or unknowable, possible or impossible; (2) Human agency that considers the impact of humans on the future, as well as the level of hope and optimism that might guide futures thinking (see Subjective Futures below); (3) Types of change exploring narrative and causal reasoning, and how we make sense of a series of events or changes in time. A futures literacies perspective assumes that the consequential ways we think about the future are not fixed—they are malleable, negotiable, and collaboratively generated matters of concern with reverberating consequences in our lives and on the planet.

(Dis)Embodying futures

Futures literacies is predicated upon an expansive view of literacies in which meaning is not only a cognitive matter, but also emerges in a psycho-social-experiential landscape of entangled factors (e.g., Leander & Ehret, Citation2019). In this section, we review critical and empirical research and theory on subjective framings of futures that are relevant to futures literacies, including futures consciousness, future orientation, future time perspective, and futures as embodied phenomenological experience.

Futures consciousness

Futures consciousness can be thought of as a future-facing historical consciousness. Sandahl (Citation2015) described historical consciousness as providing students with a “usable past” that can help orient them toward possible futures (this “use” of the past resembles Miller’s [Citation2018] phrase “using-the-future”). Ercikan and Seixas (Citation2015) conceptualized historical consciousness as awareness of the “web of temporal change” (p. 67) that is ever flowing and in which we are all caught up. Futures consciousness aims not only to observe this temporal change, but also to recognize our agency that allows us to intentionally alter and guide that flow of change.

Ahvenharju et al. (Citation2018) synthesized research that focused on futures consciousness and the related concepts of futures orientation, prospective attitude, anticipation, prospection, projectivity, and futures literacy. They distilled their literature into a conceptual model of futures consciousness that has five dimensions: time perspective, agency beliefs, openness to alternatives, systems perception, and concern for others. Futures literacy, according to their view (citing Miller’s definition), differs as a model from futures consciousness because it focuses more on cognitive and analytical development of futures thinking to the exclusion of other psychological processes. As we have explained above, we adopt a broader view of literacies that is inclusive of both FL and the concepts included in Ahvenharju’s review.

Lombardo (Citation2007) developed a holistic and normative framework of future consciousness within an evolutionary paradigm. He suggested that human beings can engage in purposeful evolution by cultivating heightened futures consciousness to create a better future. Elsewhere, Lombardo and Cornish (Citation2010) maintained that our ability to understand and respond to the future requires a psychological integration of ability, process, and experience. Lombardo’s work builds upon empirical research conducted by the influential peace studies scholar Johan Galtung—who defined future consciousness as an awareness of possible, probable, and desirable futures (quoted in Lombardo, Citation2007)—and Sande (Citation1972), who built upon Galtung’s work in the development of a six-part model of future consciousness that included: time perspective, optimism, level of interest, expectations, influence, and values.

Bateman and Sutherland-Smith (Citation2011) and Bateman (Citation2009) studied the cultivation of intentional futures consciousness among teachers with the goal of disrupting neoliberal and capitalist curricula in schools. Their work revealed that teachers who bring an explicit critical futures consciousness into classrooms can empower students to see the multiple possibilities of their education. The neoliberal curriculum thus becomes one of many educational lenses through which students can re-imagine their futures.

Future orientation

Seginer (Citation2009) documented the evolution of psychological conceptualizations of future orientation, which relates to futures consciousness, but which also contains less normative value-based attributes. Seginer (Citation2008) also argued that futures orientation is the image people consciously represent of their individualized future. Futures orientation, in this way, is analogous to autobiography; it consists of the personal stories of the future that give meaning to one’s life. Highlighting six psychological fields sharing interest in understanding futures orientation (human motivation, self-theories, personality, cognitive processes, neuropsychology, and human development), Seginer further distilled meaning into two groups: athemic, which are structural models, and themeic, which are content and imagery-based models (p. 9). Beal (Citation2011), in contrast, theorized an alternative future orientation based upon data from two large empirical studies. Her model has four elements: extension, detail, domain, and affect. Beal further combined these with four factors that influence behavior: motivation, control, sequence of events, and number of cognitions.

In work examining the impact of teachers’ futures orientation upon their style of teaching, Trommsdorff’s (Citation1983) view of future orientation contained both cognitive and affective qualities. She explored additional empirical evidence of how futures orientation can beneficially impact students’ abstract cognitive processes of things like causality, but also the more affective elements of motivation, optimism, and the alignment of thematic futures with personal outcomes guided by future goals. Damber’s (Citation2009) study indicated that future-oriented pedagogy can have positive impact on students in the development of positive attitudes, increased sense of agency, motivation, and professional aspirations. Hideg and Nováky (Citation2010) looked at changes in future orientation at a more cultural level among a broad population of Hungarians from the years 1995 to 2006. While thinking about the future had increased by 2006, they found the future orientation parameters concerned with uncertainty, risk management, and future-oriented action had decreased. As an intervention, they recommended explicit future orientation in school curriculums. Recent research continues to show important links between positive future orientation and better outcomes for school-aged youth (Shubert et al., Citation2020; Steiger et al., Citation2017; Sulimani-Aidan & Melkman, Citation2021). This research included in this section suggests profound pedagogical and psychological benefits can be gained from an explicit engagement with future orientation in schools. A futures literacies perspective can be a catalyst for conversations about future orientation among educators and their students.

Affective futures

The recent affective turn in literacy research challenges educators and researchers to reexamine subjectivity and the idea of a bounded “self” and to “reimagine the human subject as a more-than-human configuration of entities or force relations” (Dernikos & Thiel, Citation2020, p. 32). Affect theory asks us to “reimagine bodies of all kinds (e.g., literacy, students, texts, utterances)” as “saturated with affect” (Dernikos, Citation2020, p. 429). This perspective places the body within entangled and richly relational assemblages in which “[e]nvironment, objects, body, internal states, story world, and time are coexperienced” (Leander & Boldt, Citation2013, p. 29). Out of this dynamic movement literacy-as-event (Burnett & Merchant, Citation2020) emerges. Dernikos and Thiel (Citation2020) revealed how normative views of literacy and literacy pedagogy contain an inherent promise of upward mobility and career success which can negatively reinforce the gendered, classist, and racialized narratives of meritocracy. They challenged prescriptive orientations to literacy, and instead promoted a view of literacy as a practice of affective time-travelling where we might disrupt restrictive mainstream narratives of normativity that are keeping us “affectively stuck in time(s)” (p. 37). Similarly, Leander and Boldt (Citation2013) critiqued the foundational text “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies” in which the New London Group predicated their work upon a view of futurity, progress, and predefined goals that are then “projected onto students as the trajectory of their activities” (p. 28). Leander and Boldt challenged the inherent grammar of design as being orientated toward the future as a goal to be achieved. Instead, they suggested that equally powerful learning can happen in the absence of a goal, when learners are simply experiencing the moment, motivated by curiosity in what might happen next.

While Bussey (Citation2014, Citation2016) did not site affect theory in his work, he did call for a more embodied and affective perspective on feeling futures. He outlined five futures senses: memory, foresight, voice, optimism, and yearning and took an explicitly cultural approach to futures pedagogy. He encouraged students to examine their own historically informed futures imaginary while considering the possibility of taking up wider and more inclusive perspectives.

Like affect theory, applications of posthumanism (e.g., Braidotti, Citation2019; Hayles, Citation1999) are rooted in relational models that extend beyond the boundaries of the body and have resulted in profound effects upon contemporary literacy scholarship. Posthumanism asks us to question the binary distinctions humanism draws between entities, especially the human and the other-than-human, and to extend our ethical commitment toward nonhuman agencies beyond our understanding. As Kuby and Rowsell (Citation2017) wrote, “we (humans, nonhumans and more-than-humans) are all always already entangled with each other in becoming, in making, in creating realities (the world)” (p. 288). Wargo (Citation2019) observed that time and temporality in traditional literacy research has been a mere backdrop to the observed phenomenon. Building upon Barad’s (Citation2013) “spacetimemattering” and their provocation of new materialism as a way to engage in new “imaginaries of time” (para. 6), Wargo viewed temporality as a “material/discursive/contextual dimension” of human experience (p. 132). These interdisciplinary approaches to the affective experience of temporality and futurity have much to offer our view of futures literacies because they make room for conceptualizing and experiencing time beyond a linear and anthropocentric model.

Material futures

A futures literacies perspective involves critical evaluation of the technologies we incorporate into our lives and bodies, the stories we write and consume, and the images we hold both personally and culturally of the vast future imaginary. Walsh (Citation1993) showed how future images can have a spectrum of positive and negative impacts upon psychological well-being. In her research on the conflicted future images held by young people and educators in different contexts, Rubin (Citation2013) revealed the powerful impact these images have upon motivation. Once identified, she observed these images can be more intentionally “shared, developed, adopted, crushed, and changed” (p. S40).

Burnett and Merchant (Citation2020) examined the evolving technologies of our media-saturated environment and the changing ways that texts operate in our lives. They argued that textual representations are becoming increasingly interwoven with human behavior, creating new forms of meaning that can be both empowering and harmful. Artificial Intelligence, social media, and surveillance capitalism all contribute to an evolving textual politics that shape the future by effecting certain outcomes over others. Critical media scholars like Kellner et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated how media construct and impose meanings on audiences. In this way, all media has a performative futuring potential. Having evolved out of the historical future imaginary (Dourish & Bell, Citation2014), contemporary technologies like the laptop and the cellphone contain their own futuring potential when entangled with literacy practices that form our current and future identities (Leander & Burriss, Citation2020).

The arts and humanities provide rich avenues for performing socially and ecologically just futures. Climate fiction (cli-fi) considers past, present, and future environmental outcomes—that is, possible human and/or other-than-human extinction and the challenges of living through and adapting to existential outcomes (Gladwin, Citation2018; Waldman, Citation2018, para. 1). A proliferation of intersectional, boundary defying literary genres have become popular forms of entertainment, cultural interventions, and scathing critique of the hegemonic and colonized futurity offered up in mainstream colonized spaces. We cannot possibly name or adequately cite the vast amount of literature, or the bodies of scholarship dedicated to the many identity-based speculative genres that have proliferated. Via music, film, art, literature, and cultural criticism, genres like Afrofuturism (e.g., Campbell & Hall, Citation2013; Eshun, Citation2003; Syms, Citation2013), Indigenous Futurity (e.g., Lempert, Citation2018; Taylor, Citation2021; “Initiative for Indigenous Futures,” n.d.), and Queer Futures (e.g., Lothian, Citation2018; “The Queer Futures Collective,” n.d.) imaginatively re-story past, present, and futures via subordinated cultural lens and foregrounding minority experience. By reclaiming oppressive narratives and upending the colonized futures within them, these genres endorse radical empowerment via imaginative engagement with possibility. Taking up intersectional futurities in classrooms with students has profound pedagogical potential. Wozolek (Citation2018) and Truman (Citation2019), for example, investigated how intersectional futures narratives can promote important conversations about what a decolonized future of education might look like. Ultimately, the diverse genres briefly discussed in this section explore the politics and power inherent in future imagining with the goal of decolonizing and diversifying future-forming practices (O’Brien & Lousley, Citation2017) and therefore have an important role to play in a futures literacies perspective.

Discussion

In this review we have sketched an expansive model that includes diverse methods for (de)constructing futures in the present moment, the different ways we subjectively (dis)embody futurity as beings in time, and the material futures we collaboratively dream, weave, write, code, and dance that inform who we are becoming in the present moment. We further suggest that a futures literacies pedagogy might support educators in the following ways:

Honor and celebrate the diverse futures literacies already existing among learners across various disciplines and cultures.

Invite learners to actively participate in articulating and asserting their creative agency in storying as possibility.

Create opportunities for students to investigate the contingency of dominant disciplinary narratives by which we structure our lives and knowledge systems.

Encourage students to imagine different temporal perspectives and other-than-human futures beyond normative anthropocentric perspectives.

Provide students with established methodologies and frameworks for imagining the future and examining their own orientation toward the future.

Engage students in interdisciplinary conversations about the worlds we are creating through both our actions and inactions.

Futures literacies can be applied variously across the curriculum. For example, in math students might examine the historical development of mathematical theory and the ways math continues to change with advances in technology (Shapiro, Citation2014). In science and technology classes, students might combine makerspace learning with speculative storytelling. Futures storytelling can, for example, become a productive way for learners to metabolize computational thinking concepts, while considering the future lives made artifacts might take on beyond their makers’ intensions (Horst, Citation2020). Students in history class might analyze historical visions of the future (“Visions of the future,” n.d.), and investigate what the images tell us about the culture they emerged from as well as the culture they contributed to. Art syllabi might include multimodal futures texts as exemplars for critical and esthetic analysis, such as the dystopic futures novel The Marrow Thieves by Métis author Cherie Dimaline, or The Futuristic Sounds of Sun Ra by experimental musician, poet, and Afrofuturist Sun Ra. An expansive and interdisciplinary framing of futures literacies has the potential of opening productive dialogue and knowledge sharing across the disciplines.

Conclusion: A future for futures literacies

It is no surprise that students today are feeling anxious about the future. In a study exploring how teachers do or do not make connections between their subject-matter teaching and a futures dimension, den Heyer (Citation2017) reported that failing to discuss the future ultimately increases a greater sense of stress in the present. Without explicit discussion of the possible futures inherent in current events, futurity can, he argued, feel like a foregone conclusion. History educators Andrews and Burke (Citation2007) also found student apathy can be counteracted by foregrounding the contingency of the past and helping students see that the future is open and “up for grabs” and that we all must take responsibility for shaping the world we wish to live in. We contend that a futures literacies perspective can make explicit the performative and political nature of meaning-making and develop diverse and inclusive modes and images of worlds as-of-yet unimagined. Put simply, futures literacies can facilitate the co-creation of possible futures rather than envisioning a singular future rooted in the past or present.

The project of building a more just and decolonized world is directly tied to education through participation in futures-imagining and the cultivation of skills that expand future-oriented civic responsibility (Battiste, Citation2013; Kellner et al., Citation2019). The many ways we envision and enact the future are fixed and determined only if they remain unexamined and uncriticized. We suggest that a futures literacies pedagogy must be inherently critical with a focus on democratizing futures, dislodging normative colonial narratives, and increasing people’s agency and empowerment. In exploring the possibilities of futures literacies as a label and a concept, we aim to provoke a plurality of interdisciplinary perspectives not only in futures-orientated literacy practices, but also in literacies that enact different foci of futures thinking (e.g., environment futures, energy futures, posthuman futures, and digital futures) (Gladwin et al., Citation2022). Futures literacies, as outlined in this review, is a complex assemblage of pathways to understand, perform, celebrate, and diversify the future unknown.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Ahmedien, D. A. M. (2020). New-media arts–based public engagement projects could reshape the future of the generative biology. Medical Humanities 47(3), 283–291. 10.1136/medhum-2020-011862

- Ahvenharju, S., Minkkinen, M., & Lalot, F. (2018). The five dimensions of futures consciousness. Futures: The Futures, 104, 1–13. 10.1016/j.futures.2018.06.010 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.06.010

- Andrews, T., & Burke, F. (2007, (January 1). What does it mean to think historically? Perspectives on history. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2007/what-does-it-mean-to-think-historically

- Anstey, M., & Bull, G. (2018). Foundations of multiliteracies: Reading, writing and talking in the 21st century. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315114194

- Aspinwall, L. G. (2005). The psychology of future-oriented thinking: From achievement to proactive coping, adaptation, and aging. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4), 203–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-006-9013-1

- Augé, M. (2014). The Future (J. Howe, Trans.). Verso.

- Barad, K. (2013). Ma(r)king time: Material entanglements and rememberings: Cutting together-apart. In P. R. Carlile, D. Nicolini, A. Langley, & H. Tsoukas (Eds.), How matter matters: Objects, artifacts, and materiality in organization studies (pp. 16–31). Oxford University Press.

- Bateman, D. (2009). Transforming teachers’ temporalities: Futures in curriculum practices. [Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation]. Australian Catholic University.

- Bateman, D., & Sutherland-Smith, W. (2011). Neoliberalising learning: Generating alternate futures consciousness. Social Alternatives, 30(4), 32–37. http://dro.deakin.edu.au/view/DU:30041180

- Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. Purich Publishing.

- Beal, S. J. (2011). The development of future orientation: Underpinnings and related constructs. [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of Nebraska, ProQuest Dissertation Publishing.

- Bell, F., Fletcher, G., Greenhill, A., Griffiths, M., & McLean, R. (2013). Science fiction prototypes: Visionary technology narratives between futures. Futures, 50, 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2013.04.004

- Bengston, D. N. (2017). Ten principles for thinking about the future: A primer for environmental professionals. Forest Service Northern Research Station General Technical Report NRS-175,19 Retrieved from: https://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/gtr/gtr_nrs175.pdf.

- Bengston, D. N. (2018). Principles for thinking about the future and foresight education. World Futures Review, 10(3), 193–202. 10.1177/1946756718777252 https://doi.org/10.1177/1946756718777252

- Bleecker, J. (2009). Design Fiction: A short essay on design, science, fact and fiction. Near Future Laboratory, 29, 1–97. https://drbfw5wfjlxon.cloudfront.net/writing/DesignFiction_WebEdition.pdf

- Bobbitt, F. (2004). Scientific method in curriculum-making. In D. J. Flinders, & S. J. Thornton, S. (Eds.), The curriculum studies reader (2nd ed., pp. 9–16). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203017609

- Boulding, E. (1988). Building a global civic culture: Education for an interdependent world. Teachers College Press.

- Braidotti, R. (2019). A theoretical framework for the critical posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society, 36(6), 31–61. 10.1177/0263276418771486 https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276418771486

- Burdick, A. (2019). Designing futures from the inside. Journal of Futures Studies, 23(3), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0006

- Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2020). Undoing the digital: Sociomaterialism and literacy education. Routledge.

- Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2021). Returning to text: Affect, meaning making, and literacies. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(2), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.303

- Bussey, M. (2014). Intimate futures: Bringing the body into futures work. European Journal of Futures Research, 2(1) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40309-014-0053-6

- Bussey, M. (2016). The hidden curriculum of futures studies: Introducing the futures senses. World Futures Review, 8(1), 39–45. 10.1177/1946756715627433 https://doi.org/10.1177/1946756715627433

- Cagnin, C. (2018). Developing a transformative business strategy through the combination of design thinking and futures literacy. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 30(5), 524–539. 10.1080/09537325.2017.1340638 https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2017.1340638

- Campbell, B., & Hall, E. A. (2013). Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and beyond. Rosarium Publishing.

- Canada and the United Nations Educational. (n.d.). Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/unesco/index.aspx?lang=eng

- Candy, S. (2010). The futures of everyday life: Politics and the design of experiential scenarios. [Doctoral dissertation], University of Hawai’i at Manoa. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305280378_The_Futures_of_Everyday_Life_Politics_and_the_Design_of_Experiential_Scenarios

- Candy, S., & Dunagan, J. (2017). Designing an experiential scenario: The people who vanished. Futures, 86, 136–153. 10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.006 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.05.006

- Clandinin, D. J. (2007). Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology. Sage Publications.

- Clèries, L., & Morrison, A. (2020). Design futures now: Literacies & making. Temes de Disseny, (36), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.46467/TdD36.2020.8-15

- Colebrook, C. (2016). Futures. In B. Clarke & M. Rossini (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to literature and the posthuman (pp. 196–208). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316091227.01

- Damber, U. (2009). Reading, schooling, and future time perspective: A small-scale study of five academically successful young swedes. The International Journal of Learning: Annual Review, 16(1), 235–248. 10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i01/58707 https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9494/CGP/v16i01/58707

- den Heyer, K. (2017). Doing better than just falling forward: Linking subject matter with explicit futures thinking. One World in Dialogue, 4(1), 5–10. https://ssc.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/OneWorldInDialogue/OneWorldinDialogue_2016Vol4No1/den%20Heyer.pdf

- Dernikos, B. P. (2020). Tuning into rebellious matter: Affective literacies as more-than-human sonic bodies. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 19(4), 417–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-11-2019-0155

- Dernikos, B. P., & Thiel, J. J. (2020). Literacy learning as cruelly optimistic: Recovering possible lost futures through transmedial storytelling. Literacy (Oxford, England), 54(2), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12207

- Dourish, P., & Bell, G. (2014). Resistance is futile: Reading science fiction alongside ubiquitous computing. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 18(4), 769–778. 10.1007/s00779-013-0678-7 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-013-0678-7

- Draudt, A., Hadley, J., Hogan, R., Murray, L., Stock, G., & West, J. R. (2015). Six insights about science fiction prototyping. Computer (Long Beach, Calif.), 48(5), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.2015.142

- Dunne, A., Raby, F. (2013). Speculative everything: Design, fiction, and social dreaming. The MIT Press.

- Edelman, L. (2004). No future: Queer theory and the death drive. Duke University Press.

- Enciso, P. (2019). Stories of becoming: Implications of future-oriented theories for a vital literacy education. Literacy (Oxford, England), 53(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12175

- Ercikan, K., & Seixas, P. (Eds.). (2015). New directions in assessing historical thinking. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315779539

- Eshun, K. (2003). Further considerations of Afrofuturism. CR (East Lansing, Mich.), 3(2), 287–302. 10.1353/ncr.2003.0021 https://doi.org/10.1353/ncr.2003.0021

- Facer, K. (2019). Storytelling in troubled times: What is the role for educators in the deep crises of the 21st century? Literacy (Oxford, England), 53(1), 3–13. 10.1111/lit.12176 https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12176

- Facer, K., & Sriprakash, A. (2021). Provincialising futures literacy: A caution against codification. Futures: The Journal of Policy, Planning and Futures Studies, 133, 102807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2021.102807

- Frame, B. (2019). A typology for Antarctic futures. The Polar Journal, 9(1), 236–246. 10.1080/2154896x.2018.1559015 https://doi.org/10.1080/2154896X.2018.1559015

- Futures Literacy. (n.d.). Futures literacy: A skill for the 21st century. UNESCO. https://en.unesco.org/themes/futures-literacy

- Gergen, K. J. (2015). From mirroring to world-making: Research as future forming. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 45(3), 287–310. 10.1111/jtsb.12075 https://doi.org/10.1111/jtsb.12075

- Gladwin, D. (2018). Ecological exile: Spatial injustice and environmental humanities. Routledge.

- Gladwin, D. (2021). Rewriting our stories: Education, empowerment, and well-being. Cork University Press.

- Gladwin, D., Horst, R., James, K., Sameshima, P. (2022). Imagining futures literacies: A collaborative practice. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 22(7), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v22i7.5246

- Goodson, I., & Gill, S. (2014). Critical narrative as pedagogy. Bloomsbury.

- Gough, N. (2017). Specifying a curriculum for biopolitical critical literacy in science teacher education: Exploring roles for science fiction. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 12(4), 769–794. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-017-9834-0

- Harney, S., & Moten, F. (2013). The undercommons: Fugitive planning & black study. Minor Compositions.

- Hayles, N. K. (1999). How we became posthuman: Virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. University of Chicago Press.

- Hideg, É., & Nováky, E. (2010). Changing attitudes to the future in Hungary. Futures, 42(3), 230–236. 10.1016/j.futures.2009.11.008 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2009.11.008

- Hofvenschioeld, E., & Khodadadi, M. (2020). Communication in futures studies: A discursive analysis of the literature. Futures, 115, 102493. 10.1016/j.futures.2019.102493 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.102493

- Horst, R., James, K., Takeda, Y., & Rowluck, W. (2020). From play to creative extrapolation: Fostering emergent computational thinking in the makerspace. Journal of Strategic Innovation and Sustainability, 15(5), 40–54.

- Horst, R. (2021). Narrative futuring: An experimental writing inquiry into the future imaginaries. Art/Research International, 6(1), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.18432/ari29554

- Inayatullah, S. (1998). Causal layered analysis: Poststructuralism as method. Futures, 30(8), 815–829. 10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-3287(98)00086-X

- Inayatullah, S. (2008). Six pillars: Futures thinking for transforming. Foresight (Cambridge), 10(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636680810855991

- Initiative for Indigenous futures. (n.d.). https://indigenousfutures.net/

- Jackson, Z. I. (2020). Becoming human: Matter and meaning in an antiblack world. New York University Press.

- Johnson, B. D. (2011). Science fiction prototyping: Designing the future with science fiction. Synthesis Lectures on Computer Science, 3(1), 1–190. 10.2200/S00336ED1V01Y201102CSL003 https://doi.org/10.2200/S00336ED1V01Y201102CSL003

- Kellner, D., Share, J., & Luke, A. (2019). The critical media literacy guide: Engaging media and transforming education. Brill Sense.

- Ketonen-Oksi, S. (2018). Creating a shared narrative: The use of causal layered analysis to explore value co-creation in a novel service ecosystem. European Journal of Futures Research, 6(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s40309-018-0135-y https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309-018-0135-y

- Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2014). Studying new literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58(2), 97–101. 10.1002/jaal.314 https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.314

- Kuby, C. R., & Rowsell, J. (2017). Early literacy and the posthuman: Pedagogies and methodologies. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 17(3), 285–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798417715720

- Lane, C., & Solis, J. (2019). A study of digital science fiction prototyping in an elementary school setting. In A. Reyes-Munoz, P. Zheng, D. Crawford, V. Callaghan (Eds.). EAI international conference on technology, innovation, entrepreneurship and education. TIE 2017. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, Vol. 532. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02242-6_28

- Leander, K., & Boldt, G. (2013). Rereading “A pedagogy of multiliteracies”: Bodies, texts, and emergence. Journal of Literacy Research, 45(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X12468587

- Leander, K. M., & Ehret, C. (2019). Affect in literacy learning and teaching: Pedagogies, politics and coming to know. Routledge. 10.4324/9781351256766

- Leander, K. M., & Burriss, S. K. (2020). Critical literacy for a posthuman world: When people read, and become, with machines. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1262–1276. 10.1111/bjet.12924 https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12924

- Lethabo-King, T. L., Navarro, J., & Smith, A. (2020). Otherwise worlds: Against settler colonialism and anti-blackness. Duke University Press.

- Lempert, W. (2018). Indigenous media futures: An introduction. Cultural Anthropology, 33(2), 173–179. 10.14506/ca33.2.01 https://doi.org/10.14506/ca33.2.01

- Liveley, G., Slocombe, W., & Spiers, E. (2021). Futures literacy through narrative. Futures, 125, 102663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102663

- Lothian, A. (2018). Old futures: Speculative fiction and queer possibility. New York University Press.

- Lombardo, T. (2007). The evolution and psychology of future consciousness. Journal of Futures Studies, 12(1) 1–23.

- Lombardo, T., & Cornish, E. (2010). Wisdom facing forward: What it means to have heightened future consciousness. The Futurist, 44(5), 34.

- Maheshwari, S. (2013, August 5). What it’s like to be a corporate “Futurist.” BuzzFeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/sapna/there-are-corporate-jobs-where-you-can-be-a-futurist-and-go

- Markussen, T., & Knutz, E. (2013, September). The poetics of design fiction. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces (pp. 231–240). https://doi.org/10.1145/2513506.2513531

- McRuer, R. (2017). No future for crips: Disorderly conduct in the new world order; or, disability studies on the verge of a nervous breakdown. In Anne. Waldschmidt, Hanjo Berressem & Moritz Ingwersen (Eds.), Culture – Theory – Disability: Encounters between disability studies and cultural studies (1. Aufl. ed.). transcript-Verlag. (pp. 63–77).

- Miller, R. (2007). Futures literacy: A hybrid strategic scenario method. Futures, 39(4), 341–362. 10.1016/j.futures.2006.12.001 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2006.12.001

- Miller, R. (2015). Learning, the future, and complexity: An essay on the emergence of futures literacy. European Journal of Education, 50(4), 513–523. 10.1111/ejed.12157 https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12157

- Miller, R. (Ed.). (2018). Transforming the future: Anticipation in the 21st century. Routledge. 10.4324/9781351048002

- Miller, R. (n.d.) About. Research Gate. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Riel_Miller2

- Morrison, A., Bjørnstad, N., Martinussen, E. S., Johansen, B., Kerspern, B., & Dudani, P. (2020). Lexicons, literacies and design futures. Temes De Disseny, 36, 114–149. https://www.raco.cat/index.php/Temes/article/view/373847

- Morrison, A., & Chisin, A. (2017). Design fiction, culture and climate change: Weaving together personas, collaboration and fabulous futures. The Design Journal, 20(sup1), S146–S159. 10.1080/14606925.2017.1352704 https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2017.1352704

- Murris, K., & Bozalek, V. (2019). Diffracting diffractive readings of texts as methodology: Some propositions. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 51(14), 1504–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1570843

- O’Brien, S., & Lousley, C. (2017). A history of environmental futurity: Special issue introduction. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, 4(2–3), 1–20. 10.5250/resilience.4.2-3.0001

- Perry, K. H. (2012). What is literacy?–A critical overview of sociocultural perspectives. Journal of Language & Literacy Education, 8(1), 50.

- Pinar, W. F. (1994). The method of “Currere” (1975). Counterpoints, 2, 19–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42975620

- Polak, F. (1961). The image of the future. (E. Boulding, Trans.). Elsevier Scientific.

- Poli, R. (2017). Introduction to anticipation studies. Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-63023-6

- Pride, S., Frame, B., & Gill, D. (2010). Futures literacy in New Zealand. Journal of Futures Studies, 15(1), 135–143.

- Rhisiart, M., Miller, R., & Brooks, S. (2015). Learning to use the future: Developing foresight capabilities through scenario processes. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 101, 124–133. 10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.015 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.10.015

- ross, k m. (2019). On Black education: Anti-blackness, refusal, and resistance. In C. A. Grant, A. Woodson, & M. Dumas (Eds.). The future is black: Afropessimism, fugitivity, and radical hope in education. Routledge.

- Rubin, A. (2013). Hidden, inconsistent, and influential: Images of the future in changing times. Futures, 45, S38–S44. 10.1016/j.futures.2012.11.011 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2012.11.011

- Sandahl, J. (2015). Civic consciousness: A viable concept for advancing students’ ability to orient themselves to possible futures? Historical Encounters, 2(1), 1–15.

- Sande, Ö. (1972). Future consciousness. Journal of Peace Research, 9(3), 271–278. 10.1177/002234337200900307 https://doi.org/10.1177/002234337200900307

- Sardar, Z. (2010). The namesake: Futures; futures studies; futurology; futuristic; foresight—What’s in a name? Futures, 42(3), 177–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2009.11.001

- Seginer, R. (2009). Future orientation: Developmental and ecological perspectives. Springer.

- Seginer, R. (2008). Future orientation in times of threat and challenge: How resilient adolescents construct their future. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32(4), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408090970

- Shapiro, J. (2014, July 24). 5 things you need to know about the future of math. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jordanshapiro/2014/07/24/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-the-future-of-math/?sh=318a64b3590e

- Shubert, J., Wray-Lake, L., & McKay, B. (2020). Looking ahead and working hard: How school experiences foster adolescents’ future orientation and perseverance. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(4), 989–1007. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12575

- Staley, D. J. (2002). A history of the future. History and Theory, 41(4), 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2303.00221

- Staley, D. J. (2007). History and future: Using historical thinking to imagine the future. Lexington Books.

- Steiger, R. M., Stoddard, S. A., & Pierce, J. (2017). Adolescents’ future orientation and nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 269–274.

- Sulimani-Aidan, Y., & Melkman, E. (2021). Future orientation among at-risk youth in Israel. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(4), 1483–1491. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13478

- Syms, M. (2013, December 17). The mundane Afrofuturist manifesto. Rhizome. https://rhizome.org/editorial/2013/dec/17/mundane-afrofuturist-manifesto/

- Taylor, D. H. (2021). Me tomorrow: Indigenous views on the future. Douglas & McIntyre.

- The New London Group. (1996). A pedagogy of multiliteracies designing social futures. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Lit learning (pp. 19–46). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203979402-6

- The queer futures collective. (n.d.). https://www.queerfutures.com/

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305278283

- Trommsdorff, G. (1983). Future orientation and socialization. International Journal of Psychology, 18(1-4), 381–406. 10.1080/00207598308247489 https://doi.org/10.1080/00207598308247489

- Truman, S. E. (2019). SF! Haraway’s situated feminisms and speculative fabulations in english class. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9632-5

- Truman, S. E., Hackett, A., Pahl, K., McLean Davies, L., & Escott, H. (2021). The capaciousness of no: Affective refusals as literacy practices. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(2), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.306

- Underwood, K. (2020, February 27). Why companies are hiring sci-fi writers to imagine the future. Pivot Magazine. https://www.cpacanada.ca/en/news/pivot-magazine/2020-02-27-sci-fi-prototyping

- Urry, J. (2016). What is the future? Polity.

- Vidergor, H. E. (2018). Multidimensional curriculum enhancing future thinking literacy: Teaching learners to take control of their future. Brill Sense.

- Visions of the future. (n.d.). Lessons from history. https://www.lessons-from-history.com/page/visions-future

- Waldman, K. (2018, November 9). How climate-change fiction, or "cli-fi," forces us to confront the incipient death of the planet. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/how-climate-change-fiction-or-cli-fi-forces-us-to-confront-the-incipient-death-of-the-planet

- Walsh, S. M. (1993). Future images: An art intervention with suicidal adolescents. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 6(3), 111–118. 10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80171-5 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80171-5

- Wargo, J. M. (2019). Lives, lines, and spacetimemattering: An intra-active analysis of a ‘Once OK’ adult writer. In C. R. Kuby, K. Spector, & J. J. Thiel (Eds.), Posthumanism and literacy education (1st ed., pp. 130–141). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315106083-14

- Weaver, J. (2019). Curriculum SF (speculative fiction): Reflections on the future past of curriculum studies and science fiction. Journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Curriculum Studies, 13(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.14288/jaaacs.v13i2.191108

- Wilderson, F. (2021). Afropessimism and the ruse of analogy: Violence, freedom struggles, and the death of black desire. In M.-K. Jung & J. Costa Vargas (Eds.), Antiblackness (pp. 37–59). Duke University Press.

- Wickens, C. M., & Sandlin, J. A. (2007). Literacy for what? Literacy for whom? The politics of literacy education and neocolonialism in UNESCO-and World Bank–sponsored literacy programs. Adult Education Quarterly, 57(4), 275–292.

- Wozolek, B. (2018). The mothership connection: Utopian funk from bethune and beyond. The Urban Review, 50(5), 836–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0476-7

- Wynter, S., & McKittrick, K. (2020). Unparalleled catastrophe for our species? or, to give humanness a different future: Conversations. In K. McKittrick (Ed.), Sylvia Wynter: On being human as praxis (pp. 9–89). Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822375852-003