Abstract

Can we increase students’ grasp and integration of research methods in political science, and do so in a fun way? We believe the answer is yes. In this article, we introduce the workshop-based narrative framework “The Tale of Folke Folkesson,” where students role-play as the methods expert group Linnaeus Opinion Laboratory (LOL). Through an interactive engagement with the story, students are exposed to the combined utility of various qualitative and quantitative techniques such as content analysis, survey research, experiments, and interviews. This methodological exercise enables students to recognize not only the individual strengths and weaknesses of each method, but also how one method can offset the limitations and/or amplify the benefits of another. Importantly for student learning, it does so in a fun and engaging way. Beyond introducing the narrative framework, we describe how educators can adapt the “Tale of Folke Folkesson” to meet their specific educational needs.

Introduction

Teaching methods in the social sciences is no small feat. Many undergraduate students think of the methods course as both the most challenging (Asal et al. Citation2018) and the most uninteresting course (Adriaensen, Kerremans, and Slootmaeckers Citation2015). We get this: Few are drawn to political science because of their burning passion for ethnographic sensibility, logistic regression models, or mixed methods research epistemology. Irrespective of this lack of enthusiasm, proficiency in methods remains indispensable for aspiring academics and analysts. For teachers, then, the question becomes how we can effectively teach an expanding repertoire of methods, ensure that students grasp the interconnections among them, and make the learning process more enjoyable?

In this article, we provide one example of how to accomplish this. We do so by introducing the “Tale of Folke Folkesson”Footnote1 as an innovative pedagogical approach targeted at undergraduates new to both qualitative and quantitative methods in the social sciences. The “Tale of Folke Folkesson” is a narrative framework built up by practical workshops. During each two-hour workshop, students role-play as methodological advisers to Folke Folkesson, guiding him through the complexities of Swedish public opinion on his journey to create a successful new political party.Footnote2

We argue that this approach has two main advantages. First, it teaches students to practically use methods, which is a critical first step in learning to apply them in actual research outside coursework (Elman, Kapiszewski, and Kirilova Citation2015; Sullivan and De Bruin Citation2022). Placing students in role-play positions as part of a narrative enables us to apply a form of active peer-to-peer learning, where students both apply methods in practice and learn from their peers. Including these elements in a course structure can be particularly important in methods courses, where students may initially see methodological concepts as “dry” and abstract (Fisher and Justwan Citation2018). The inclusion of active learning in scenario-based exercises via role-play also provides an opportunity to incorporate an element of humor, which can help create a relaxed atmosphere that encourages participation in course exercises, ultimately benefitting learning (Garner Citation2006; Nesi Citation2012).

Second, the narrative framework serves as an introduction to mixed methods logic. Although each workshop is structured to focus exclusively on a single method to ensure clarity, the mixed methods logic enters via Folke Folkesson’s continuous quest for knowledge. Following the initial workshop, each subsequent workshop is introduced as required due to the preceding method having been proven to be insufficient, or that Folke Folkesson needs additional input unattainable through the previous method. Essentially, by concentrating on a single phenomenon—the views of the Swedish people—the workshops illustrate key parts of mixed methods logic, such as understanding what methods best can answer which specific research questions, how to effectively combine methods, and in what research sequence which method is most suitable given the objective. Thus, the second key contribution from this article lies in its introduction of a teaching method for mixed method reasoning that can be applied in general political science methods courses at the bachelor level.

The article proceeds as follows: We begin by outlining previous research that we take our departure in and seek to contribute to. We then describe the workshop context and structure along with how we delivered the workshops in practice. Having done so, we present the four integrated workshops, including excerpts from each workshop instruction. We close by briefly explaining how this approach to teaching methods can be adopted in other social sciences, discuss how our approach contributes to the state of the literature, and describe our own experience developing and implementing the “Tale of Folke Folkesson.”

Previous research

The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) and the broader literature on pedagogical innovation in higher education is vast: covering elements such as the theory, practice, and evaluation of various pedagogical techniques. In creating the “Tale of Folke Folkesson,” we have particularly drawn on four areas of this literature: active learning through scenario-based teaching, peer-to-peer learning, humor in pedagogy, and the teaching of mixed methods.

The workshop is designed based on active learning principles, where students are actively and practically engaged in the learning process as opposed to passively receiving information. Among other things, research has demonstrated how including active learning elements can increase engagement, knowledge retention, and meaning construction (Michael Citation2006; Coffey, Miller, and Feuerstein Citation2011). Our approach to drafting a narrative tale, informed by hypothetical yet realistic scenarios, is particularly informed by the literature that has demonstrated the many potential benefits of scenario-based teaching. For instance, previous research has shown that students engaged in scenario-based and argumentation-based learning had significantly stronger academic achievements compared to those who had regular class-based teaching (Aslan Citation2019); that scenario-based activities increased both classroom readiness and self-efficiency among students in online settings (Bardach et al. Citation2021); and that scenario-based teaching increased academic achievement compared to reflective learning (Hursen and Fasli Citation2017). In the realm of methods teaching, Schrader, Mariappan, and Shih (Citation2004) found that scenario-based teaching led to increased knowledge as well as interest from students.

Moreover, we facilitate peer-to-peer learning by asking the students to work in groups and present the results to each other. While the primary aim of including peer-to-peer learning—through group work, presenting to their peers, and giving feedback on each other’s works—was for students to better grasp the course material, research has shown that peer-to-peer learning has numerous additional benefits (Boud, Cohen, and Sampson Citation2001). For instance, previous research has shown that peer-to-peer learning can improve students’ critical thinking, collaborative, and communicative skills (Stigmar Citation2016), as well as their abilities to manage their education and learning process (Bowden and Morton Citation1998). On a broader institutional level, Gamlath (Citation2022) has suggested that peer-to-peer learning should be an integrated part not only in individual courses but throughout educational settings in undergraduate education in general.

Including active learning via role-play also provides an opportunity to incorporate an element of humor. Beyond the intrinsic value of incorporating humor in higher education—most people find it enjoyable to laugh—previous research has also shown how humor in teaching has instrumental value for various student outcomes. A review of over 40 years of research on humor and education found that the most positive impact concerns the learning environment (Banas et al. Citation2011). Benefits of using humor in teaching include increased participation in the classroom (Wanzer and Frymier Citation1999), improvements in student content retention (Garner Citation2006), and the ability to relieve stress and anxiety among students (Berk Citation1996). Considering that students often perceive methods courses to be particularly challenging, using humor to foster positive attitudes toward learning in a relaxed atmosphere has been found to be particularly beneficial (Berk and Nanda Citation1998; Kher, Molstad and Donahue Citation1999; Garner Citation2006; Nesi Citation2012).

We also draw from the literature on how to effectively teach mixed methods—a methodological practice previous studies have shown is particularly challenging for students to grasp, and for teachers to teach (Hesse-Biber Citation2015; Christ Citation2009). Beyond teaching the fundamentals of each method, mixed method pedagogy faces an additional challenge in teaching how to combine and/or integrate these methods. Although many teachers of mixed methods focus explicitly on this in their teaching (Frels et al. Citation2014), the integration of methods remains one of the most difficult aspects when using mixed methods in real-world research (Zhou and Wu Citation2022).

Pedagogical literature on how to use active learning in teaching mixed methods to overcome the integration/combination and similar issues is a burgeoning field. Researchers have for example advocated for a socio-ecological framework for teaching mixed methods courses (Ivankova and Plano Clark Citation2018); a four-phase model for teaching mixed methods research at the doctoral level (Onwuegbuzie et al. Citation2013); and an open-space activity for learning the synthesis concept in mixed methods research (Johnson, Murphy, and Griffiths Citation2019). While more research is needed to evaluate the specific aspects of each framework, a study examining the effects of using active learning methods for learning mixed methods found that students were actively engaged in the course and achieved the expected learning outcomes (Zhou, Citation2023). Adding to this literature, this study offers a novel contribution by introducing a practical narrative tale that illustrates how incorporating an additional method can offset the limitations and/or amplify the benefits of another. Crucially, this narrative framework can be adopted into general large-scale methods courses at the bachelor level and is not restricted to either specific mixed methods courses or the graduate level.

Fundamentally, the “Tale of Folke Folkesson” both draws on, and seeks to contribute to, prior research. It draws on existing research in the sense that the design and implementation of the workshop were based on pedagogical principles as outlined in previous research on active scenario-based learning, peer-to-peer learning, and humor in order to teach methods in general and mixed methods reasoning in particular. It contributes to the literature by providing a narrative framework in the form of a series of workshops, effectively condensing and applying the aforementioned theoretical concepts into a practical pedagogical instrument.

Workshop context and structure

We introduced the “Tale of Folke Folkesson” as part of a five-week undergraduate research methods course required for obtaining a bachelor’s degree offered by the Department of Political Science at Linnaeus University in Sweden. The course was introductory, whereby we could assume that most of the approximately 90 attending students had little to no prior experience with social science methods. The course was structured around three core educational components: Lectures introducing the foundations of each method, hands-on workshops via “The Tale of Folke Folkesson”, and specific analytical sessions teaching students how to analyze data using various methods. How to best teach both the fundaments of each method and how to apply them analytically has been extensively covered elsewhere (inter alia, Creswell and Plano Clark Citation2017; Pachirat Citation2018; Alasuutari, Bickman, and Brannen Citation2008; Dunning Citation2012; King, Keohane, and Verba Citation1994; Mosley Citation2013). In the remainder of this article, we will therefore focus on how we constructed and delivered the “Tale of Folke Folkesson.”

The narrative framework unfolded through a set sequence combining morning lectures and accompanying workshops in the afternoon. Students were provided instructions on which course materials to read before each lecture. However, having read the material before the lecture was not a pre-condition for being able to take part in the workshops. This was important because, as any educator would know, not all students do the readings before lectures even though they have been recommended to do so. Still, a majority, if not all, who attended the workshops also attended the preceding lectures, and the workshops were therefore based mainly on the materials covered in the lecture.

All four workshops followed a similar structure, iteratively building on their predecessor and thereby enabling students to see how various methodological approaches can complement or counterbalance one another. Students were told they were employees at Linnaeus Opinion Laboratory (LOL) and had been tasked with carrying out various research missions for a fictitious man called “Folke Folkesson.” Folke was presented as a driven man with a seemingly limitless political interest, creating a lightly humoristic atmosphere. For each two-hour workshop, students received clear instructions on the questions Folke Folkesson needed answered, what method they should use to answer them, and particular aspects of the method to focus on. Students then left the classroom to work in small groups of five to seven, asked to return within one hour, meaning they had to make swift decisions and distribute tasks among them. When returning to the classroom, each group’s proposal was placed on the classroom whiteboards using static writing sheets, and the groups took turns presenting and discussing their result. This was followed by a final collective debriefing session led by the workshop teacher, meant to explore the advantages and disadvantages of various methodological decisions.

The entire setup was based on the idea of minimal preparation and technology. This meant students were provided e.g., hand-outs, pens, scissors, glue and paper depending on the workshop assignment requirements, able to get to work straight after receiving instructions. Furthermore, the largely manual process minimized the risk of ChatGPT rather than students completing the assignments and that precious time was not lost for teachers and students due to any technological issue.Footnote3

Beyond the ease of students being able to attend the workshop without much mandatory preparation and start working together quickly, additional efforts were made to encourage participation. Even though the workshops were connected and built upon each other, instructions regarding LOL and Folke Folkesson were briefly reiterated during each workshop. This made it possible for students to miss one or more of the workshops, and still follow along. Importantly, we decided to make the workshop optional and not part of the final course grade, although we underlined that participating would be beneficial when studying for the upcoming final course exam. We wanted to create an environment where students felt comfortable engaging wholeheartedly with the scenarios, daring to make bold choices and experiment without risking a lower grade. Despite the workshop not being part of the official examination, most students participated in the workshops and did so enthusiastically. As the course came to an end, students both verbally and in writing when evaluating the course expressed that making the workshops voluntary and not grading them was essential for creating the necessary atmosphere.

The four workshops in the “Tale of Folke Folkesson”

The section below presents the basic idea behind each workshop along with an excerpt of the workshop instructions. We also discuss the benefits of each workshop in terms of the methodological aspects raised with students and how the workshops build on each other.

The content analysis workshop

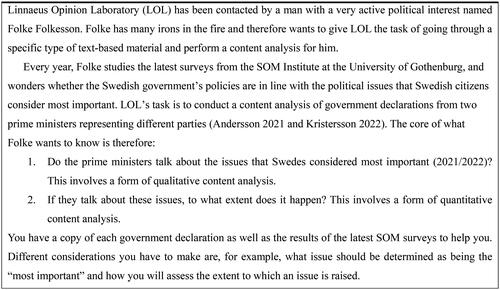

Until the first workshop, students are completely unaware of the narrative framework of the workshops. Now is thus when they are introduced to Folke Folkesson and addressed as employees of LOL for the first time (see ). This moment is one of giggles and smiles, but it swiftly turns into a sense of seriousness once it is clear to the students that they have a task to complete within an hour.

Before analyzing these authentic political speeches students quickly have to find the information they need from a hand-out of the results of a national survey, presented in tables. They also need to define how to apply an issue the Swedish people have ranked as important, such as “law & order”, in their analysis of speeches. Groups that choose a qualitative approach have to agree on how to draw qualitative conclusions based on how certain policies or themes are discussed in the speeches, and groups that choose a quantitative approach have to determine what the unit of analysis should be, such as mentions of certain words or phrases.

As the launch of the first workshop throws students into having to quickly complete a practical assignment, we place some effort on selling the story. This does not require dramatic skills nor comedic genius. Instead, in our experience, it is sufficient to relay a matter-of-fact introduction of the students’ fictitious new roles and the needs expressed by their ambitious new client. Students are also ensured that any results will be interesting to Folke, meaning that during the debriefing session together with the teacher, no group risks feeling as if they have done something “wrong.” This also allows students to consider what went well and where they might have gone wrong while also seeing the benefits and weaknesses of both main approaches to content analysis.

The survey workshop

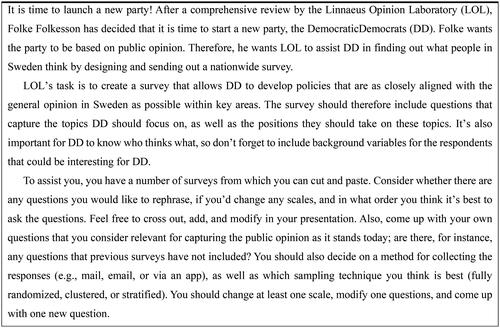

In the previous workshop, students assessed whether existing political parties addressed the public’s concerns. Finding that politicians do not seem to speak about what the people think are the most important issues, Folke decides to create a new party, the DemocraticDemocrats, based solely on public opinion. Consequentially, LOL is tasked with conducting a nationwide survey to capture the public opinion (see ).

The workshop aims to teach students the basics of survey design. They must make crucial decisions such as selecting questions that capture public opinion on key topics, determining question order, choosing the measurement scale, identifying relevant background variables, and selecting data collection methods. Although the task may seem daunting for undergraduates without prior experience, it is made easier by the preceding lecture that covered these topics and the availability of existing surveys to borrow from. The cut and paste were part of the analog structure of the workshops, and it also made the exercise more fun—more than one student mentioned that using glue brought back fond kindergarten memories. During the debriefing, students presented and justified their survey designs, thus gaining practical knowledge in both presenting their work and learning from their peers. The workshop relates to the previous workshop by illustrating how one method’s outcomes can lead to the adoption of a different method, emphasizing the iterative development of research and how it can evolve in distinct phases.

The survey experiment workshop

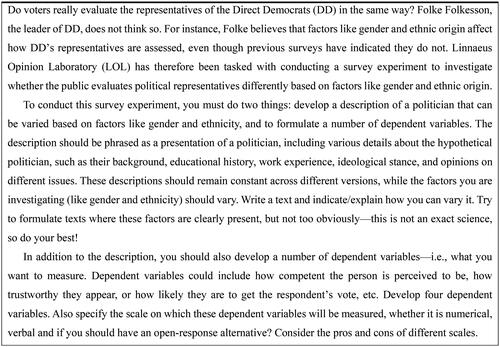

Despite the previous survey’s conclusion that attributes like gender and ethnicity are irrelevant to evaluations of politicians, Folke Folkesson remains skeptical, as everyday experiences suggest otherwise. LOL is tasked with exploring his suspicion, prompting the need for an experimental method (see ).

The workshop aims to teach students how to craft their own survey experiments, focusing on aspects such as designing vignettes, selecting variables, and determining the measurement scales for dependent variables. In the debriefing session, we particularly focus on the merits and drawbacks of various vignette designs, compared different scales—as was also done in the survey workshop—and explore the primary differences in analyzing these scales. The workshop relates to the previous workshop by illustrating how one method can mitigate the shortcomings of another and serve as a complementary methodological approach. Specifically, it shows how survey experiments can mitigate the biases inherent in traditional surveys and how content analysis—used in the first workshop—can be used to gain additional insights from a survey experiment if an open-ended response alternative is included.

The interview workshop

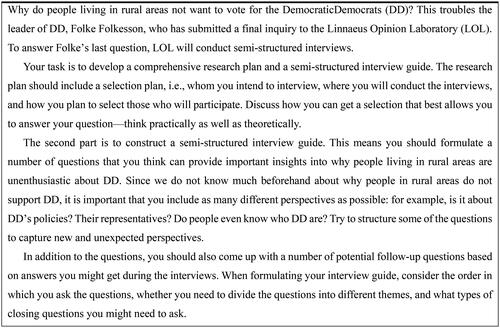

Despite LOL’s use of both a survey and a survey experiment, Folke Folkesson still faces unanswered questions. Specifically, it seems that people in rural areas are hesitant to vote for the DemocraticDemocrats. To explore why, LOL is tasked with drafting a plan for conducting semi-structured interviews (see ).

The workshop’s objective is to teach students how to leverage the strengths of interviews in exploring rationales behind decisions. Although a range of interview and ethnographic methods could be used for this workshop, we decided to focus on semi-structured interviews, as this is the most commonly used interview technique among undergraduates at our university for their thesis project. The workshop has two main parts: the initial part is devoted to planning aspects like interviewee and location selection. The subsequent part centers on developing an interview guide, particularly aiming to design flexible questionnaires that can adapt to respondents’ responses. The last part is essential, as a common pitfall in our experience is students adhering too rigidly to their semi-structured interview plans rather than allowing interviewee responses to inform the interview. The workshop relates to the previous ones by showing how interviews can complement previously used methods, such as uncovering the rationale underlying the survey results. During the debriefing session, we stress how insights gained from exploratory interviews can also inform the development of subsequent surveys or survey experiments, thus underscoring the iterative nature of research.

Discussion & conclusions

Learning methods is difficult, and teaching it is demanding. Through this interactive and playful narrative framework, we have introduced a way to make it a little less difficult, and a lot more fun. Having piloted this narrative tale—consisting of workshops in content analysis, surveys, survey experiments, and interviews—in an introductory methods course, our experience is that most students find them fun, engaging, and enriching. As discussed below, we come to this conclusion based on verbal and written feedback and our own impressions from a pedagogical perspective.

In order to involve students in further developing the workshops and learn from their experiences, we devoted time during the final lecture to highlight that since the series of workshops they had participated in was a new addition to the methods course we very much appreciated their feedback. Students commented on how the workshops tied the course together and emphasized the social and non-mandatory aspects. With some additional time to contemplate the course upon its completion, students followed up their feedback in the course evaluation, highlighting the benefits of applying knowledge provided in a lecture immediately in a workshop, which was said to have provided a new dimension to their learning. Additionally, students reiterated how the workshops provided an opportunity to work with and get to know other students better, and how the framework created a sense of cohesion during the course, which is typically difficult if the research methods course consists primarily of introducing one method after another. Overall, compared to previous semesters, students gave the course higher scores when it came to outcomes like being stimulated to critical thinking and experiencing an ‘aha’ moment.

In terms of being able to conclude that our playful addition to the course, it is worth noting that while we did not doubt that it could be implemented, it was nevertheless highly dependent on our success in convincing the students to participate in a non-mandatory part of the course and, in a sense, play along with our narrative. Specifically, incorporating humor has many benefits, as presented in a previous section, but there is still the risk that it simply lands wrong (Nesi Citation2012), and students feel discouraged from participating. To our relief, we received no indications from students that the humorous elements in combination with role-playing felt artificial, contrived or somehow not believable enough to merit involvement. We believe that the matter-of-fact approach to how we introduced the workshops, as illustrated in our abbreviated workshop instructions above, helped maintain the humor element at an appropriate level, appealing to both students who are very receptive to a range of pedagogical styles and those who prefer emphasis on explicitly academic challenges posed by teachers.

Moreover, we argue that these results can contribute to the practical development of active learning based methods for teaching methods in general and for teaching mixed methods in particular. Given that different teachers face different challenges—be they institutional, pedagogical, or otherwise—we believe the application can be of the spirit rather than the letter of the “Tale of Folke Folkesson.” For instance, the tale can be broadened in scope with an additional workshop on critical discourse analysis in the beginning, one about case studies in the middle, and be concluded with a normative analysis in the end. To underline the different elements and kinds of mixed methods research designs—such as fully mixed, partially mixed, and concurrent/sequential designs (Leech and Onwuegbuzie Citation2007)—one can also change the order of the workshop or conduct them in parallel. The tale’s content can also be adjusted to fit the regional context (although we recommend keeping the LOL acronym).

The narrative framework can also be enriched by adding a component where students actively gather and analyze data, independently deciding what additional method to use in order to offset the limitations and/or amplify the benefits of another. This part can either be integrated as a part of the narrative framework itself (with multiple potential follow-up workshops) or assigned as independent tasks, thereby strengthening the practical application of methods and placing a stronger focus on the mixed methods aspects of the exercise.Footnote4 The current structure’s main advantage lies in its time-efficient and engaging nature, allowing students to grasp the basics of each individual method while simultaneously being introduced to mixed methods reasoning and the integration of methods. Thus, while we see the potential advantages in expanding the narrative framework with additional workshops, incorporating new elements, and integrating the framework even further in mixed methods reasoning, we maintain that this approach is suitable at the bachelor level in a large classroom with approximately 90 students. We are, however, vary of too broad generalizations with a limited sample: more cases are needed to determine under what conditions other teachers and students share our positive experience working with the framework. This is something we hope will follow from this article.

Fundamentally, the framework’s value lies in providing an enjoyable narrative in which students with little prior methodological knowledge can grasp the fundamentals of methods in political science through the guidance of instructors and their peers. By introducing the “Tale of Folke Folkesson” in this article, we hope to stimulate the use of scenario-based teaching in general and the development of the narrative tale in particular. We believe this could lead to students grasping more methods, yield better student researchers, and, by extension, better political scientists. We think Folke would like that.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Staffan Andersson at Linnaeus University and the two anonymous reviewers, whose comments were instrumental in the development of this article.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joel Martinsson

Joel Martinsson is a Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at Linnaeus University in Växjö, Sweden. His teaching and research focus on political theory, mixed methods, and the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.

Emma Ricknell

Emma Ricknell is a Senior Lecturer of Political Science at Linnaeus University in Växjö, Sweden. Her research interests include media and politics, state legislative politics, and pedagogy in higher education.

Notes

1 Translation note: The name “Folke Folkesson” serves as a political science pun. “Folke” is a Swedish name that echoes “folk,” which means “people” in English, highlighting his quest to understand the political perspectives of the Swedish populace at large.

2 Following the typologies from Rao and Stupans (Citation2012), in this article we use role-play in a “role-acting” sense, meaning that students acted as real-life professionals.

3 While we recognize the potential value of using AI-based tools such as ChatGPT for pedagogical innovation more broadly, integrating them in this particular exercise would not have benefitted our efforts to facilitate active participation and verbally based interaction.

4 We are grateful to the reviewer who pointed this out.

References

- Adriaensen, Johan, Bart Kerremans, and Koen Slootmaeckers. 2015. “Editors’ Introduction to the Thematic Issue: Mad about Methods? Teaching Research Methods in Political Science.” Journal of Political Science Education 11 (1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2014.985017.

- Alasuutari, Pertti, Leonard Bickman, and Julia Brannen. 2008. The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Asal, Victor, Nakissa Jahanbani, Donnett Lee, and Jiacheng Ren. 2018. “Mini-Games for Teaching Political Science Methodology.” PS: Political Science & Politics 51 (4):838–41. doi: 10.1017/S1049096518000902.

- Aslan, Serkan. 2019. “The Impact of Argumentation-Based Teaching and Scenario-Based Learning Method on the Students’ Academic Achievement.” Journal of Baltic Science Education 18 (2):171–83. doi: 10.33225/jbse/19.18.171.

- Banas, John A., Norah Dunbar, Dariela Rodriguez, and Shr-Jie Liu. 2011. “A Review of Humor in Educational Settings: Four Decades of Research.” Communication Education 60 (1):115–44. doi: 10.1080/03634523.2010.496867.

- Bardach, Lisa, Robert M. Klassen, Tracy L. Durksen, Jade V. Rushby, Keiko C. P. Bostwick, and Lynn Sheridan. 2021. “The Power of Feedback and Reflection: Testing an Online Scenario-Based Learning Intervention for Student Teachers.” Computers & Education 169 (August):104194. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104194.

- Berk, Ronald A. 1996. “Student Ratings of 10 Strategies for Using Humor in College Teaching.” Journal on Excellence in College Teaching 7 (3):71–92.

- Berk, Ronald A., and Joy P. Nanda. 1998. “Effects of Jocular Instructional Methods on Attitudes, Anxiety, and Achievement in Statistics Courses.” Humor 11 (4):383–409.

- Boud, David, Ruth Cohen, and Jane Sampson, eds. 2001. Peer Learning in Higher Education: Learning from & with Each Other. London, UK: Kogan Page

- Bowden, John, and Ference Morton. 1998. The University of Learning: Beyond Quality and Competence in Higher Education. 1st ed. London: Kogan Page.

- Christ, Thomas W. 2009. “Designing, Teaching, and Evaluating Two Complementary Mixed Methods Research Courses.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 3 (4):292–325. doi: 10.1177/1558689809341796.

- Coffey, Daniel J., William J. Miller, and Derek Feuerstein. 2011. “Classroom as Reality: Demonstrating Campaign Effects through Live Simulation.” Journal of Political Science Education 7 (1):14–33. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2011.539906.

- Creswell, John W., and Vicki L. Plano Clark. 2017. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Dunning, Thad. 2012. Natural Experiments in the Social Sciences: A Design-Based Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139084444.

- Elman, Colin, Diana Kapiszewski, and Dessislava Kirilova. 2015. “Learning through Research: Using Data to Train Undergraduates in Qualitative Methods.” PS: Political Science & Politics 48 (01):39–43. doi: 10.1017/S1049096514001577.

- Fisher, Sarah, and Florian Justwan. 2018. “Scaffolding Assignments and Activities for Undergraduate Research Methods.” Journal of Political Science Education 14 (1):63–71. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2017.1367301.

- Frels, Rebecca K., Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie, Nancy L. Leech, and Kathleen M. T. Collins. 2014. “Pedagogical Strategies Used by Selected Leading Mixed Methodologists in Mixed Research Courses.” Journal of Effective Teaching 14 (2):5–34.

- Gamlath, Sharmila. 2022. “Peer Learning and the Undergraduate Journey: A Framework for Student Success.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (3):699–713. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1877625.

- Garner, R. L. 2006. “Humor in Pedagogy: How Ha-Ha Can Lead to Aha!.” College Teaching 54 (1):177–80. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.54.1.177-180.

- Hesse-Biber, Sharlene. 2015. “The Problems and Prospects in the Teaching of Mixed Methods Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18 (5):463–77. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2015.1062622.

- Hursen, Cigdem, and Funda Gezer Fasli. 2017. “Investigating the Efficiency of Scenario Based Learning and Reflective Learning Approaches in Teacher Education.” European Journal of Contemporary Education 6 (2):264–79. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2017.2.264.

- Ivankova, N. V., and V. L. Plano Clark. 2018. “Teaching Mixed Methods Research: Using a Socio-Ecological Framework as a Pedagogical Approach for Addressing the Complexity of the Field.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21 (4):409–24. doi: 10.1080/13645579.2018.1427604.

- Johnson, Rebecca E., Marie Murphy, and Frances Griffiths. 2019. “Conveying Troublesome Concepts: Using an Open-Space Learning Activity to Teach Mixed-Methods Research in the Health Sciences.” Methodological Innovations 12 (2):205979911986327. doi: 10.1177/2059799119863279.

- Kher, Neelam, Susan Molstad, and Roberta Donahue. 1999. “Using Humor in the College Classroom to Enhance Teaching-Effectiveness in Dread Courses.” College Student Journal 33 (3):400–6.

- King, Gary, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Leech, Nancy L., and Anthony J. Onwuegbuzie. 2007. “A Typology of Mixed Methods Research Designs.” Quality & Quantity 43 (2):265–75. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3.

- Michael, Joel. 2006. “Where’s the Evidence That Active Learning Works?” Advances in Physiology Education 30 (4):159–67. doi: 10.1152/advan.00053.2006.

- Mosley, Layna, ed. 2013. Interview Research in Political Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Nesi, Hilary. 2012. “Laughter in University Lectures.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 11 (2):79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2011.12.003.

- Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J., Rebecca K. Frels, Kathleen M. T. Collins, and Nancy L. Leech. 2013. “Conclusion: A Four-Phase Model for Teaching and Learning Mixed Research.” International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches 7 (1):133–56. doi: 10.5172/mra.2013.7.1.133.

- Pachirat, Timothy. 2018. Among Wolves – Ethnography and the Immersive Study of Power. Routledge Series on Interpretive Methods. New York: Routledge.

- Rao, Deepa, and Ieva Stupans. 2012. “Exploring the Potential of Role Play in Higher Education: Development of a Typology and Teacher Guidelines.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 49 (4):427–36. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2012.728879.

- Schrader, Peter, Jawa Mariappan, and Angela Shih. 2004. “Scenario Based Learning Approach in Teaching Statics.” Paper presented at the 2004 Annual Conference Proceedings, Salt Lake City, Utah, ASEE Conferences, 9.1083.1–9.1083.7. doi: 10.18260/1-2–13347.

- Stigmar, Martin. 2016. “Peer-to-Peer Teaching in Higher Education: A Critical Literature Review.” Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 24 (2):124–36. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2016.1178963.

- Sullivan, Heather, and Erica De Bruin. 2022. “Teaching Undergraduates Research Methods: A ‘Methods Lab’ Approach.” PS: Political Science & Politics 56 (2):309–14. doi: 10.1017/S1049096522001366.

- Wanzer, Melissa B., and Ann B. Frymier. 1999. “The Relationship between Student Perceptions of Instructor Humor and Students’ Reports of Learning.” Communication Education 48 (1):48–62. doi: 10.1080/03634529909379152.

- Zhou, Yuchun. 2023. “Teaching Mixed Methods Using Active Learning Approaches.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 17 (4):396–418. doi: 10.1177/15586898221120566.

- Zhou, Yuchun, and Min Lun Wu. 2022. “Reported Methodological Challenges in Empirical Mixed Methods Articles: A Review on JMMR and IJMRA.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 16 (1):47–63. doi: 10.1177/1558689820980212.