Abstract

Teaching International Relations (IR) today takes place in a challenging context. While the international community appears disoriented in formulating effective answers to the overall destabilization of the world of global affairs, students of IR may feel increasingly lost applying their heavily standardized grids of analysis to a confusing and ever-changing realm. In light of significant global challenges like global warming, opening up the syllabi to new and creative approaches seems overdue. In this paper, I provide in-depth observations of an alternative approach to teaching IR, based on the innovation method Design Thinking. The insights are based on two experimental seminar style courses at the graduate and undergraduate levels. Over the entire duration of the respective course, the students were invited to tackle specific international problems such as migration governance in the Mediterranean, making use of the full creative potential of Design Thinking tools. The hands-on character of the method helped translate complex social or political issues into tangible ones and inspired the students to enlarge their perspective. The positive outcomes in terms of both the quality of resulting work and active student participation show that creative methods, while not in and of themselves able nor sufficient to fully replace more established concepts of teaching IR, can and should play a greater role in encouraging a more hands-on approach to understanding the international context, in which we live.

Introduction: Challenging the status quo of teaching IR

In the early 2020s, teaching International Relations (IR) takes place in a pretty harsh atmosphere. International leaders like Wladimir Putin in Russia or Former US-President Donald Trump have contributed to a climate of insecurity, violence and gloominess. The worldwide Corona pandemic only adds to this discomforting picture, while the international community itself appears disoriented in formulating effective answers to the destabilized state of global affairs (see for example Smith and Hornsby 2021, 3). In this rather dire setting, students of IR may feel increasingly lost applying their heavily standardized lenses of analysis to an ever-changing realm. In light of significant global challenges like global warming, it appears obvious to open up the syllabi to creative approaches. While creativity could be a new core element of doing IRFootnote1, the teaching remains broadly dominated by what Carniel et al. call “pedagogies of convenience” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 9). Deviations from the mainstream are still relatively rare and often viewed with suspicion that they might disrupt the well-established teaching routines. Carniel at al. quote Kacowicz who observes that “the subject of change in IR has been neglected because of an underlying tendency in the discipline to overemphasize stability and the status quo” (Kacowicz Citation1993, 80, quoted in Carniel et al. Citation2023, 4). Against this background, the authors underline that “IR instructors have a responsibility to prepare students to respond to a changing rather than fixed world” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 4, emphasis in the original).

To meet this important requirement, scholars have drawn upon the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning literature to develop what Shulman calls “pedagogies of uncertainty” (Shulman Citation2005, 57). Such methodological openness is even more important for the field of IR, as it is first and foremost a practical form of education: “At the most basic level, and irrespective of theoretical persuasion, IR is animated by the question of ‘how we should act’” (Reus-Smit and Snidal Citation2008, 7). Yet an IR education is, strictly speaking, “neither professional nor vocational in orientation, but introduces students to different theoretical and methodological perspectives with the intent of illuminating global issues that demand action (e.g., promoting peaceful coexistence between nations or addressing transboundary challenges, such as climate change)” (Lüdert Citation2021, 2). To effectively do so, I will argue that designerly approaches such as Design Thinking appear to offer a promising addition to the toolkit available to those teaching IR by making their students engage directly with the international realm.

Design Thinking provides a distinct methodological framework to deal with various wicked problems in and beyond the field of IR, as well as expand the discipline beyond the prioritized interactions between nation-states. Given the slippery characteristics and the complexities of those wicked problems, “we cannot teach students to solve problems with concrete techniques, (…), we can teach them professional habits and mindsets that will best equip them with the necessary resilience and adaptability to grapple with complexity and uncertainty” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 6). Against this background, the Design Thinking toolbox represents a great methodological starting point for IR scholars and students.

Although this approach offers manifold opportunities to include the broader body of IR theory into the Design Thinking process, it seems less appropriate for a rather standardized literature-based introductory course than for thematic or policy-oriented courses touching upon specific areas of IR. For example, the design-driven logic and the focus on prototyping makes Design Thinking a promising tool to inquire into complex issues such as climate diplomacy, international trade or case studies in peace and conflict.

In order to generate practical insight into the application of Design Thinking in the field of IR, I conceived and conducted two Design Thinking-inspired experimental seminar courses at the graduate and undergraduate levels at two North German universities. In the respective courses, the students were asked to develop creative approaches to certain foreign policy problems, such as migration governance in EU-Libyan relations or specific areas of the Middle East conflict.

Before discussing the two experimental cases in-depth, the first section of this article will locate this project within the body of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. The second section will then highlight some general considerations on how the design-driven approach engages with problems in IR and how to translate this process into specific didactic tools. In the third section, I will present the experimental courses and share some of their features. The forth section includes a discussion of the outcomes and observations and addresses specific difficulties, before concluding with a very brief outlook on the potentials of Design Thinking methodology as a valuable asset in the pedagogical toolbox.

Experiential learning and IR pedagogy

The experimental cases draw upon the rich literature on Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, understood here broadly as the systematic reflection of teaching staff on their own teaching experiences and their exchanges with the teaching community (see Huber Citation2014, 21). It is important to note that this kind of classroom research differs from classic educational science research by prioritizing the practical relevance for teaching, qualitative approaches and context validity over methodological rigidity (ibid., 31). In this vein, Huber calls for more qualitative studies on situated experience, defined by a specific teaching context and providing detailed observation. This approach seems to be particularly fitting when it comes to creative settings and experiences of learning-by-doing as proposed by experiential learning.

The framework of experiential learning lends itself as a suitable starting point when it comes to rethinking the somewhat orthodox IR teaching practices: “Experiential learning is an engaged learning process whereby students “learn by doing” and by reflecting on the experience” (Boston University Center for Teaching and Learning Citation2023). If they are well-planned, supervised and assessed, “experiential learning programs can stimulate academic inquiry by promoting interdisciplinary learning, civic engagement, career development, cultural awareness, leadership, and other professional and intellectual skills” (ibid.). In order to be considered experiential, learning needs to respond to four main criteria (see ibid.): 1. Reflection, critical analysis and synthesis; 2. Opportunities for students to take initiative, make decisions, and be accountable for the results; 3. Opportunities for students to engage intellectually, creatively, emotionally, socially, or physically; 4. A designed learning experience that includes the possibility to learn from natural consequences, mistakes, and successes. If all those features are fully developed, experiential learning can produce an authentic learning environment that facilitates the understanding of complex international problems.

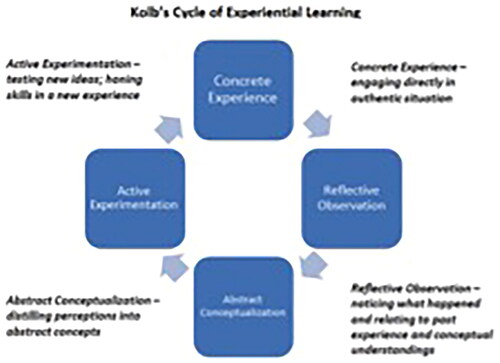

Kolb (Citation1984) exemplifies this approach by proposing a cycle of learning that reflects the experiential character of the process. The cycle highlights how knowledge, defined as “the concepts, facts and information acquired through formal learning and past experience”, activity, defined as “the application of knowledge to a ‘real world’ setting” and reflection, defined as “the analysis and synthesis of knowledge and activity to create new knowledge” (Boston University Center for Teaching and Learning Citation2023) alternate continuously. As I will show in the next section, Kolb’s learning cycle fits remarkably well into the Design Thinking micro cycle (or vice-versa), which underlines this project’s roots in experiential learning.

Motivated to provide authentic learning experiences, many IR scholars have also developed Signature Pedagogies, which include a wide range of didactic approaches ranging from Inquiry-based learning to simulation games, which have the merit to cover some of the most important learning aspects. Simulations are considered a particularly effective way to introduce students to the processes of the international realm “in a safe and controlled environment, while also exciting their continued interest in the discipline” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 12). On the other hand, there are also certain risks involved:

“With their emphasis on applied knowledge, simulations are particularly useful deepening student understanding of theoretical models by enabling them to see their effects in practice. However, what many simulation learning plans can lack is an explicit critical reflection, and one that goes deeply into unpacking the influences on individual and group decision-making processes. As a result, students might emerge from a simulation with a strong understanding of the content and a refinement of practical skills, such as research and communication, but without deeper reflection on the experience may not have attained deep learning goals” (ibid., 13). She highlights this point stating that by prioritizing UN simulation games, “students may develop some hidden assumptions about who are the primary actors in IR and the power dynamics among them. Non-state actors, for example, are not introduced until later iterations of the UN simulation to reduce the complexity of the first simulation” (She Citation2021, 160).

In addition, preparing simulation games requires very high levels of planning and a trained and dedicated teaching staff. As a consequence, it seems difficult “to shape a simulation around specific current events while they are still in motion. Established scenarios may resonate with current events thematically or precipitate them historically, but it is challenging to construct entirely new and up-to-date scenarios focusing on them specifically” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 5). All of this makes simulations a great teaching tool, but one that seems unsuitable to engage with current events and spark interest by connecting to contemporary issues. Design Thinking lends itself as a very promising tool to bridge that gap, inviting the students to explore new roles and to rediscover the world from different perspectives.

Following a Design-driven approach

Starting with the question of how to bring a more hands-on touch to the teaching of IR, Design Thinking appears to be a good point of departure: Tackling international issues from a perspective of design rather than orthodox IR methodology, the students approach the topic by moving “through iterative phases of thinking and doing” (Dalsgaard Citation2014), alternating between the “logic and certainty” (Martin Citation2009, 2) of established knowledge, “raw creativity” (ibid.) and exposure to first-hand experience and observation.

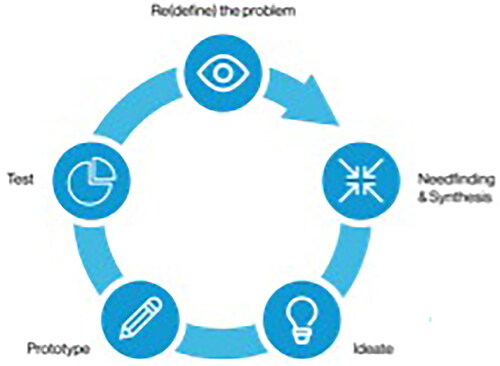

This is reflected in the Design Thinking micro cycle as proposed by Uebernickel et al. (see ). It illustrates the fundamental process of Design Thinking as an iterative practice consisting of the steps of problem definition, need-finding and ideation, as well as prototyping and testing before returning to the problem definition.

Figure 1. The Design Thinking micro cycle (Uebernickel et al. Citation2015, 25).

For the students, the cycle involves first a phase of problem definition including thorough observation and extensive fieldwork for the purpose of data collection. To understand the problem at hand, different views and expertise must be brought together. Potential solutions should then being rendered visible through rapid prototyping, which facilitates testing and feedback, eliciting preliminary results and encouraging subsequent gradual refinement of the proposed solution in an iterative process. What prototyping and testing may look like in the context of an IR course, will be shown in section “Riding the Dark Horse: Teaching International Relations Design” with examples of student prototypes.

The Design Thinking micro cycle perfectly fits into the logic of Kolb’s cycle of Experiential Learning (see ), where phases of reflective observation (corresponding to need-finding and ideation) alternate with abstract conceptualization (prototyping) and active experimentation and concrete experience (testing).

Figure 2. Kolb’s Cycle of Experiential Learning (Boston University 2023, based on Kolb Citation1984).

At first sight, the focus on innovation and change seems to make Design Thinking incompatible with the realm of international policy making and hence with the content of IR seminars. As Safouane, Fromm, and Khan (Citation2021) have shown in their case study on group asylum, the rigidity of diplomatic traditions and the broad international consensus on appropriate behavior and suitable proceedings in diplomacy make Design Thinking appear to be inapplicable in this field.

However, a closer examination of the Design Thinking approach reveals promising access points for a conceptual translation into the sphere of international politics and the teaching of IR. Thanks to the alternation of theory and practice, as proposed by Kolb and provided by the Design Thinking process through ideation, prototyping and testing, the approach allows for unwanted side-effects to be preempted or addressed, but also with regard to bias, false reasoning or groupthink. Design Thinking might also help raise awareness for the diversity of perspectives and potentially challenge rigid belief systems that risk impeding a sound solution for the problem at hand. Like in Signature Pedagogies such as Inquiry-based learning, “students work collaboratively to develop their own “big” questions, obtain evidence through their own research, develop hypotheses or solutions, discuss and debate these solutions, and then finally—and perhaps most crucially—reflect upon the process and its outcomes” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 8).

The idea of deliberately accepting (and carefully managing) the risks involved in disruptive innovation comes across most clearly in the so-called dark horse prototype. The expression of dark horse usually describes “a horse or a politician who wins a race or competition although no one expected them to” (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/ dictionary/english/dark-horse). While the Design Thinking process is generally marked by a succession of gradually improving, gradually more focalized, realistic and usable prototypes, the dark horse will be “(…) the most creative but also difficult to build solution. Very pricy, risky and difficult to realize. If all these factors are not important what would the solution be (…)” (ibid.)? Introducing this mindset in the teaching of IR potentially helps (re-) discovering international issues from an entirely new perspective.

Thanks to the central role of prototyping and testing, Design Thinking highlights the practical character of the discipline, in line with Nayak and Selbin’s understanding of doing International Relations, which applies to both scholars and practitioners in the field (Nayak and Selbin Citation2010). At the same time, it becomes quite clear that Design Thinking cannot replace the well-established foundations of orthodox and less orthodox theories and methodologies of IR. On the contrary, the student designers are actively encouraged by their fieldwork and observation to follow the cycle of experiential learning and also make use of the state of research in and beyond their discipline in order to come up with sensible and thought-through prototypes. Accordingly, critique and testing also involves assessing the prototypes in light of the mainstream theories to evaluate their applicability and conceptual soundness.

Finally, Design Thinking explicitly calls for an interdisciplinary approach and favors solutions that bring together the available knowledge from different fields of research and policy, allowing for conceptual openness throughout the process. As a consequence, diversity and heterogeneity is considered an invaluable asset rather than an obstacle to work on the problem at hand. This makes Design Thinking a particularly powerful and inspiring tool for teaching IR to and with diverse groups of students, as I will show in the following section.

Riding the dark horse: Teaching international relations design

In the course of two seminars taught at HSU (Helmut Schmidt University)Footnote2 and Leuphana University of Lüneburg respectively, design-driven methods have been tested within the context of teaching in the field of IR. Given the novelty of the approach, the courses were deliberately designed as explorative, that is, research-based learning experiences. With view to research ethics, all students participating in the courses were informed in advance of the atypical procedure and the role they would have to play in itFootnote3. Participants were also asked to give their explicit consent that the course outcomes, including the seminar papers and the prototypes they would have to design, as well as the experiences linked to the process would be used to inform further research on the application of Design Thinking in the field of IR. For both courses, the final papers would follow the format of research diaries, providing critical reflections on the process as well as an in-depth commentary on the different stages of prototyping. Next, I will provide the specific setup for both courses before turning to an analysis and discussion of the outcomes and observations.

The first teaching experiment: Re-Thinking EU-Libya relations with Design Thinking

The first course based on Design Thinking-inspired explorative learning took place at HSUFootnote4 in the fall trimester 2018. The student group was composed of 20 master-level studentsFootnote5 with majors in different disciplines such as psychology, business science, history or educational sciences. The course was taught as an elective seminar, which HSU students could choose for their compulsory interdisciplinary studies module. It consisted of 40-50 hours of in-classroom training, complemented by take-home assignments and prototyping sessions, and was organized according to the following outline ():

Table 1. Course outline HSU.

In the introductory session, the students were familiarized with the many specificities of the courseFootnote6 and divided into working groups. The first session also served as an opportunity for extensive teambuilding both on the course level and on the subordinate working group level. Prototype development would typically take place within a working group of three to five members whereas prototype testing and, to some extent, exploration would happen in plenary sessions. After administrative proceedings, group formation and teambuilding, e.g. through the choice of a motivating and inspiring group name, was complete, time was also allotted to a first brainstorming: What aspect of the overarching topic of EU-Libya relations the working groups would like to work on and what kind of expertise would be necessary for informed prototyping? Accordingly, the selection of experts who would deliver insights into their respective field of expertise during the upcoming sessions, was only finalized only after collecting and evaluating the outcomes of this first brainstorming session.

The first workshop weekend began with a 4-hour-introduction into the theory and practice of Design Thinking. A Design Thinking professional, trained at the University of St. Gallen (partnering with the prestigious d.school at Stanford) and experienced in moderating workshop groups, accompanied the students during their first steps as designers. On the second day, a reasonable amount of context information and useful background knowledge on the case study (EU-Libya relations) was provided by student presentations. The topics included regional geography, history and state-of-the-art research on Euro-Mediterranean cooperation. In addition, the working groups were busy fine-tuning their problem definitions, deciding upon the specific aspects their prototypes would target later in the process.

The second workshop weekend was dedicated to in-depth exploration. The working groups inquired the context of their respective prototype and started working on first design ideas. The process was enhanced by external expertise made available through several short expert inputs on the most pressing issues such as human trafficking, international law, maritime security or migration studies. Also, the course included attending a public lecture by renowned migration scholar Prof. Jochen Oltmer (IMIS institute at the University of Osnabrück) that took place during the trimester at HSU. The second half of the weekend was dedicated to creative methods and prototyping. The first ideas ranged from policy recommendations and civil society action to software solutions and spatial organization ().

The two workshop weekends were followed by three four-hour long cumulative working sessions that provided an increasingly familiar setup for creative work and brought the students together for prototype discussion and testing in tandem mode (working groups would mutually evaluate their prototypes). In the second of these working sessions, the students were asked to prepare a dark horse prototype, to build their most far-fetched solutions to keep up the potential for disruptive solutions and consequent innovation. The third working session was intended to help consolidate the outcomes and to allow the student teams to prepare their final prototype. The course culminated in a final session taking up the shark tank-format from a US television show with the same name. In the original shark tank, entrepreneurs have to sell their business ideas to investors who consider buying shares of the projects presented to them. For the seminar course on the potential re-design of EU-Libya relations, the course instructor was joined by several experts for the final evaluation of the student prototypes in terms of innovation, feasibility and potential effectiveness.

The second teaching experiment: Design Thinking and the Middle East conflict

The second experimental seminar-course took place at Leuphana during the fall semester 2019/2020. In this case, the student group was composed of 16 undergraduate studentsFootnote7 with highly diverse majors such as economics, business law, digital media, computer sciences or cultural or environmental studies. The course was taught as a complementary social science course within the broad selection of electives, which is a characteristic for Leuphana College. Whereas the first round at HSU (see above) included 40-50 hours of in-class training, thanks to the specific setup of HSU’s interdisciplinary studies modules, the 2019/2020 Leuphana course had to remain within the limits of a regular seminar-course, which reduced the extent to about 25 hours in plenary session, complemented by home work assignments and prototyping on individual or group level ().

Table 2. Course outline Leuphana.

Due to the time restrictions, the introductory session comprised only two hours, packed with teambuilding exercises, brainstorming sessions and preliminary decisions with regard to the specific problems to be investigated during the seminar. Analogous to the preceding HSU course, the students used this first session to situate themselves vis-à-vis the course theme and to discuss within their newly built teams which aspect of the Middle East conflict deserved their attention most. The following workshop weekend also replicated the same structure as the first workshop weekend of the HSU course, that is, an in-depth introduction into Design Thinking by an external expert (this time an experienced trainer and alumna of the School of Design Thinking at Hasso Plattner Institute in Potsdam, Germany) followed by short presentations on crucial aspects linked to the Middle East conflict. Given the lack of time, no external experts could be invited to share their insights. As a consequence, some students benefited from their individual research in preparation for the in-class presentations and established themselves as experts within the group. The second day of the workshop weekend left room for problem definition and exploration. At the end of the day, all teams could be proud of their first prototypes. The following working sessions (two sessions of four hours each) allowed for thorough discussion, mutual testing and steady re-calibration of the student prototypes. The participants were also asked to allot some time to the preparation of a dark horse prototype and to share their interim evaluation of the course, before turning their attention to the final prototype ( and ).

While the 2018 HSU course had culminated in a shark-tank-themed final evaluation, the last session at Leuphana favored a less formalized evaluation using an exhibition format. This was due to the shorter duration of the course, which resulted in slightly more premature prototypes compared to the ones at HSU. Accordingly, the focus was more on the ideas than on the technical aspects of their application, which made highly specific expert knowledge dispensable for evaluation. During the two hours-long final session, the students could learn about and test the prototypes of the other working groups and present their own prototypes to their fellow students and to an external group of undergraduate students of political science who were invited to join the session and provide the working groups with individual feedback on their prototypes. As the research diaries show, the unfiltered critical feedback turned out to be particularly valuable and inspired some working groups to continue perfecting their prototype even after the final session of the course.

Observations, outcomes and discussion

The following section serves to organize, analyze and discuss the outcomes and observations made during the two experimental seminar courses with view to student experience and feedback, the involvement of external expertise, the role of the course instructor as well as issues of physical environment, schedules and broader applicability. I will conclude this section with a short critical reflection on the designerly perspective on IR.

Learning by crafting: the prototypes

As has been shown in section “Following a Design-Driven Approach”, the Design Thinking approach encourages and even asks for physical or material solutions to all kinds of (mostly immaterial) problems. The decidedly hands-on character of the method helps translating social or political issues into smaller tangible ones, which tends to operationalize and disentangle situations of protracted conflict and stillstand. For example, Leuphana students drew a lot of inspiration from the aspect of physical organization of spaces to soften or even overcome specific situations of Israeli-Palestinian conflict. One group of students invested many efforts in apprehending and rethinking the contested spacialities of the Temple Mount by introducing technological and logistical expertise to manage the visitor flow and local communities’ access to the site. Other participants focused on the issue of fresh water as a source of conflict, proposing detailed technical installations for the treatment of wastewater and a system of filters to increase the quality and quantity of water available to the inhabitants of the Gaza Strip ( and ).

Such hands-on approaches to the topic of Israeli-Palestinian confrontation help breaking up the ossified and discouraging political and diplomatic concept of the Middle East conflict into more manageable units of analysis and action; Each small issue eludes the larger (geo-)political context. Also, probably an outcome of business and engineering persisting as the main fields of application of Design Thinking tools, working with designerly instruments encourages thinking in terms of commodities, markets, and costumers. At the intersection of regional politics and capitalism, one working group developed a commercial brand and a marketing campaign for a series of politically and ecologically fairly traded products made in the Palestinian Territories.

At the same time, the motivation of designing ingenious products and the fun of tentatively crafting them in a series of prototyping sessions did not lead to a dismissal or a marginalization of the course’s political science content. To the contrary, all students followed an open approach and remained constantly aware of the political and social layers of the issue at hand. One group even explicitly tackled what they identified as a core problem, that is, the dispersion of enemy images nourishing social antagonisms, and developed concrete steps to encourage the inhabitants of the region to reach out to the formerly avoided other in a constructive way. As a thought experiment, the group also proposed a prototype consisting of a reform of the Israeli Military Service and the development of more inclusive schemes of citizen involvement such as intercultural social work (see ). Given Israel’s security imperatives and highly militarized social system, the prototype is to be considered in terms of dark horse thinking, serving as an eye-opener rather than as a blueprint for political decisions.

In fact, the potential irritations caused by an application of Design Thinking in an IR context can result in an immense benefit: The students potentially uncover the social and economic mechanisms at work, while seeing through the layer of political rhetoric that has determined their approach to the topic previously. For example, a working group at HSU has pushed the perspective of commodification in the context of Euro-Mediterranean migration, ending up with a shockingly accurate picture of the economics of irregular migration, where migrants are systematically exploited and used as a source of income or as an instrument of domestic politics. Insights like these might be painful but in terms of teaching, they offer a unique opportunity for discoveries and they highlight the severely needed analytical capacity to change perspective. Also in the evaluations students indicated this as particularly valuable, which leads us to the next point.

Learning experience and student reactions

When asked what they liked most about the course, participants of both seminars almost unanimously mentioned group work and prototyping, in particular working on the dark horse prototype. The response was the same during in-class feedback and debriefing as well as in the written student evaluation. Many students highlighted the change of perspectives, the exposure to new approaches and the opportunities for in-depth analysis as the most valuable aspects of the courses.

Very generally, it was eye-opening to observe the extent to which scholars, students and practitioners in the field of international politics and the academic discipline of IR tend to remain within the contours of mainstream theory when proceeding with analysis. The focus on asking questions rather than on formulating ready-made answers turned out to be an invaluable asset for overcoming these severe limitations by creating awareness for different aspects of the problem at hand and the diverse perspectives held by different stakeholders. The methodology emphasizes the phase of genuine research and data collection before the theoretical concepts of academic disciplines are brought into the process for analysis. As a consequence, prior knowledge in IR theory and methodology would turn out to be a hindrance rather than an advantage for the student participants, because specific knowledge can work as an obstacle to openness and creativity. A diverse student group with different majors and student foci is thus best equipped to meet the challenges and come up with truly innovative solutions.

In both teaching experiments, student groups have taken their role very seriously and have invested considerably in research, reading and data collection, which triggered an intrinsically motivated and self-structured process of acquiring relevant and robust context knowledge. By definition, this process is not pre-organized or structured by the instructor because every group needs to find out by itself what it needs to know in order to develop their prototype solution to the problem. Some groups felt empowered and motivated by the freedom and flexibility, other groups were more reluctant and asked for more guidance in the process. In many occasions though, this guidance could also take the form of regular student cross-evaluation, the presentation and discussion of the prototypes between the working groups of the course.

Of course, the application of a design-driven methodology to a field determined by international traditions and regulations, ossified processes and stable political convictions, does not go without difficulties, specifically when it comes to building and physically testing the prototypes (instead of simply writing a paper). But the challenge was accepted by the participating students and approached with creativity and determination, which led to impressive outcomes: Students came up with fictional characters to test their ideas, got in touch with international experts or evaluated their concepts from diverging perspectives. Not everybody falls in love with such a loose, creative approach and progress came at times in an erratic, not foreseeable way. But with time, all groups succeeded in building tangible prototypes to present at the end of the course.

Involvement of experts and Design Thinking specialists

When it comes to evaluating the role of the technical experts in helping develop student research over the course, it is difficult to draw a clear picture. Mixed feedback from student evaluations underlines this ambiguity: Many students found the talks interesting, but not targeted enough to be useful for their prototyping. The initial intent to assure a certain basic knowledge through expert talks apparently distracted some of the teams from doing their own research. If time is not an issue, it seems preferable to encourage the students to broaden their own research through reading and fieldwork. They might be given the opportunity to identify their own experts relevant to their specific project and collect the information in a decentralized way and finally share the most important findings with the seminar group. In general, organizing input through student presentations worked rather well and helped close the gap between academic research and practical application.

While the role of technical experts remains questionable, a professional introduction into the designerly process is paramount for the learning experience: In order to help the creative processes, the presence of a design thinking specialist or professional turned out to be very important when it comes to translating observations into prototypes and to remind the participants of the designerly process’s central principles. In general, access to local experts and training material can be arranged easily via networks and institutions such as the d.school at StanfordFootnote8 or its international partners. Many institutions in higher education are currently building up their own expertise and there might be a dedicated center that can provide help – pro bono or for a reasonable rate – literally next door.

With such professional input, the process also tends to gain stringency, stability and resilience toward the professional reflexes of the student participants, trained to rely on pre-defined theories rather than to keep asking questions and engage in handicrafts to visualize their outcomes. In both courses, the groups benefited a lot from the time allotted to creativity workshops and training. Familiarity with creativity methods and the Design Thinking process appears even more important when the students dispose of considerable prior knowledge in IR.

Since the (external) design thinking specialist is usually limited to a more or less intense introductory workshop and cannot accompany the course throughout the entire process for the length of the academic year due to lack of resources, it is of utmost importance to maintain the openness of the process by establishing regular feedback loops to help the students keeping track and recalibrate their work if needed. A certain degree of familiarity with Design Thinking and some preliminary self-teaching should be considered helpful for instructors to convincingly play this role throughout the course. It is recommended to participate in some kind of Design Thinking workshop or experience before the teaching starts.

The role of the lecturer and the importance of the physical setting

The crucial challenge for lecturers of a Design Thinking inspired course “refers to the management of the interplay between past and present, ensuring that students are provided with both the foundations of the discipline and the confidence to operate in unfamiliar territory” (Carniel et al. Citation2023, 4). This requires a high attention to supporting the learners and to provide them with helpful resources with regards to both methodological and knowledge issues, in order to “encourage spontaneous opportunities for learning” (Boston University Center for Teaching and Learning Citation2023).

As Lüdert observed, these tasks “shift our roles away from all-knowing lecturers to facilitators of learning. The benefits of this shift in our role are wide-ranging. They provide space to walk around the class, answer individual questions, listen carefully to group discussions, and gain an overall better understanding of students’ comprehension and comfort with the material” (Lüdert Citation2021, 8). With view to the instructor’s diverging role, it is crucial to maintain full transparency of the process and provide clear outlines and schedules to all participants in order to provide boundaries and orientation in such an open creative space.

The physical setting also played a decisive role during both of the seminar courses, because the environment and atmosphere had a big impact on the creativity of the teams. Even architectural details such as the amount and size of the windows or the color of the floors in the classroom would discretely impact the process. This factor could best be observed in the Leuphana course: Due to logistical issues, a room change occurred in the course of the seminar. For the workshop weekend, the course was assigned a cathedral-like workroom particularly prone to produce a productive and inspiring atmosphere. The special room underlined the special character of the course and the organization of the workshop weekend as a fun event rather than a tiresome curricular obligation. At the HSU, the course took place in a large open space, which could be portioned into different working areas and upgraded for the weekend sessions and hence also allowed creativity to flow.

Schedule and time

Even more important than the physical surroundings is the factor of time: For a designerly process to unfold its full potential, one needs a significant amount of time for creative work. In my observation, more generous timeslots worked a lot better then the standard 90-minutes sessions, the only limitation being the participants’ attention span. 4 to 6 hours per day turned out to be a good format. Given the tight schedules and shortage of seminar rooms during regular teaching hours, the Design Thinking courses partly had to take place on weekends, which caused organizational issues for some of the participants.

The schedule allowed students to freely move through the process and encouraged them to rethink and refine their solutions instead of clinging to the first tangible outcomes. This holds particularly true for the first steps in the Design Thinking process that involve problem definition: It is crucial for the students to take their time in order to revisit, question and challenge their assumptions (and those of their peers) and evaluate underlying problems with a sound change of perspective and an openness toward the complexities involved. Even though weekend-sessions can be long and tiring, short presentations, different forms of (expert) input using different media, short games and the huge diversity of Design Thinking methods themselves made both of the courses varied and enjoyable to most participants. While classroom teaching appears indispensable for student interaction and creative processes, some of the work could potentially be organized online (e.g. input and student presentations, group work and – to some extent – testing).

When it comes to the configuration of the final session, both formats - the shark tank at HSU and the student exhibit at Leuphana - have their merits and their mostly logistic difficulties. Both responded to the need to make the outcomes tangible and hence easily testable which produced a series of beautifully crafted prototypes. While the element of prototype testing is very prominent in both formats, the shark tank expert evaluation went more into detail and is therefore particularly interesting when it comes to discussing in more detail a limited number of relatively advanced prototypes. The exhibit format is of course less directed and leaves more freedom to the teams on how they would like to put into focus their prototype to impress the public. While the choice of the format for the final session may need to respond to a set of requirements and can hence be challenging, it seemed indispensable to allow for a somewhat public course finale, when the more or less final prototypes get confronted to the real world. This is the moment the entire course has been working toward and it is important to provide for a space where the prototypes can shine – and be scrutinized.

Critical reflection

One main point of critique toward following down a designerly path to deal with international politics is its inherent (un)ethical neutrality. In other words, the process makes no difference between legitimate and illegitimate interests and deeds. Rather than automatically prioritizing liberal-democratic values, Design Thinking methods encourage to frame the problem in a rationalized apolitical way in order to overcome deadlocks and mismanagement. However, can there be an apolitical solution to the devastating status quo of migration in the Mediterranean Sea? Don’t we have to pick our side when formulating recommendations? In the worst case, this inherent risk may lead to prototyping that either fails to address the complexities at hand or gets unproductive because of its being overcomplex. On the other hand, there is also a considerable learning effect within this problematic feature, because it forces the students to position themselves within a complex realm and to choose the right level of abstraction and compromise with their positioning when working on their topic.

The more radical and creative the prototyping gets, the more important it seems to keep the participants from slipping back into their usual set of beliefs and into today’s predominant logics of securitization and hard power or – when socialized in the world of social sciences – postcolonial critique. Giving up the familiar thinking in favor of radical openness and empathy can translate into quite a challenge, especially for more advanced scholars or individuals with relevant expertise. Context knowledge is only relevant as far as it directly responds to the designerly process, and tutor supervision can be helpful to make sure that no team builds a prototype too close to their comfort zone. To some extent, one can also count on the Design Thinking process itself to make the shortcomings visible. Prototype testing and mutual evaluations make sure that one key experience will be with every participant: IR can look very different from what today’s leading scholars and practitioners produce, but it remains a very complicated business.

Concluding remarks

The amount of significant context factors and the need for a special course setup, which includes bringing a Design Thinking expert on board to brief the student, makes Design Thinking a quite demanding option when it comes to choosing the teaching methods for an IR course. It does not lend itself as a default option and should therefore not be considered as an alternative but as an add-on to more orthodox approaches. Creative methods take away a lot of the time allotted and should be carefully integrated into the curriculum, but when they are, they have the potential to work as an eye-opener and as a key moment in the students’ learning curve. The focus on the process rather than the outcome encourages the students to ask questions and to scrutinize the answers they will get, making them aware of the manifold perspectives on and complexities of the issue at hand. Within the complex realm of political processes, what elements do define the problem and which approaches might be suited best to address them? Creative methods such as this open a space for reflection, which may be the most important effect that has also been highlighted very positively in the student evaluations. All students had to leave their academic comfort zone and open up to new thoughts and ideas, which clearly justifies the application of designerly tools.

This effect shines through most visibly in the process of building a dark horse prototype, which frees the students from the weight of political reality and makes them discover new routes away from the beaten pathways predefined by mainstream theory and practice. Even though the designed innovations might turn out to be unrealizable for good reasons, the process makes the students more aware of their knowledge and methodological toolbox, inspires them to trust their own reasoning and to engage in experiments or research. At this point it should be clear, that Design Thinking is no alternative to the more orthodox approaches, but it might help (re-) organizing knowledge according to the needs of a specific issue and the principles of experiential learning.

Maybe most importantly, the students got to widen their horizon and genuinely discover new perspectives, facts and aspects and, doing so, develop a more accurate picture of what truly is a political problem and to whom. This elucidating feature also implies keeping an open eye for potential solutions, be them partly or imperfect, and hence a more informed stance on international politics. For Lüdert, these aspects are paramount for IR teaching today: “By making IR’s foundational concepts tangible for students through exploring substantive problems, key issues and exemplary case studies in original, creative ways, drawing on various theoretical traditions and eclectic scholarship (…) we ultimately help students to emerge as critical thinkers, future practitioners, or scholars. This is different from structuring IR courses as a set of competing and segmented theories—a classical pedagogic approach risking excessive compartmentalization with students—instead of building their knowledge base” (Lüdert Citation2021, 11).

For young scholars, the right course design can hence be an invaluable asset, because they are made aware of the complexities of the international realm and given the tools to navigate their way in the rough waters of today’s International Relations.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nicolas Fromm

Nicolas Fromm is an Associated Researcher at the Institute of International Relations at Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg. He holds a PhD in International Relations from Helmut Schmidt University. In 2018/2019, Nicolas Fromm was a Visiting Professor for International Relations at Leuphana University Lüneburg.

Notes

1 In their work on ‘Decentering International Relations’, Nayak and Selbin (Citation2010) underline the importance of the practical dimension of doing instead of passively studying the discipline. This logic also strongly applies to the active role of the students within the experimental seminar courses as depicted in the third section of this text.

2 Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces in Hamburg is mainly dedicated to the academic formation of (future) Army officers. While research and teaching is organized according to the standards of civilian universities, most students have a strong military background.

3 As in the case of other German universities, no formalized procedures were in place to assure the conformity with certain ethical considerations. In lack of a standardized process or a specific board, I presented the research project to the dean’s office and discussed all matters with the heads of program. Upon receiving a green light from both offices, I obtained legal help for drafting a student consent form and an information sheet to explain the particularities of the courses. Also, both courses were taught as electives to assure that student participation in both courses was voluntary and that other course options with a more conventional setting were available to the students.

4 I am very grateful to my fellow colleagues at HSU, namely Sandra Göttsche, Hamza Safouane, Yaiza Rojas-Matas and Robert Menzies, for their precious support and their willingness to contribute their expert knowledge.

5 I would like to thank all students for their openness to actively participate in this teaching experiment at HSU during the fall trimester 2018. I am very grateful for the rich material for reflexion that has been provided by the course.

6 This concerns not only the application of innovative methods in the setting of explorative teaching, but also the administrative aspects of assuring the seminar’s compliance with all rules and regulations as required by the relevant module manual, covering for instance the exam mode or the students’ obligation to attend.

7 I would like to thank all students for their openness to actively participate in this teaching experiment at Leuphana during the fall semester 2019/2020. I am very grateful for the inspiring experience teaching this course.

8 The d.school at Stanford University is a particularly rich source of inspiration. Some of the material and ideas used for this project has been drawn from the resources available online: https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources.

References

- Boston University Center for Teaching and Learning. 2023. Experiential Learning, November 11. https://www.bu.edu/ctl/guides/experiential-learning/

- Carniel, Jessica, Mark Emmerson, and Richard Gehrmann. 2023. “Inquiry-Based Learning as an Adaptive Signature Pedagogy in International Relations.” International Studies Perspectives 2023:1–17. doi: 10.1093/isp/ekad015.

- Dalsgaard, Peter. 2014. “Pragmatism and Design Thinking.” International Journal of Design 8 (1):143–55.

- Huber, Ludwig. 2014. “Scholarship of Teaching and Learning. Konzept, Geschichte, Formen, Entwicklungsaufgaben.” In Forschendes Lehren im eigenen Fach. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Beispielen, eds. Ludwig Huber, Arne Pilniok, Rolf Sethe, Birgit Szczyrba, and Michael Vogel. Bielefeld: Berlesmann, 19–36.

- Kacowicz, Arie. 1993. “Teaching International Relations in a Changing World: Four Approaches.” PS: Political Science & Politics 26 (1):76–80.

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Lüdert, Jan. 2021. “Signature Pedagogies in International Relations.” In Signature Pedagogies in International Relations, ed. Jan Lüdert. Bristol: E-International Relations, 1–14.

- Martin, Roger. 2009. The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage. Cambridge: Harvard Business Press.

- Nayak, Meghana, and Eric Selbin. 2010. Decentering International Relations. London: Zed Books.

- Reus-Smit, Christian, and Duncan Snidal. 2008. The Oxford Handbook of International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Safouane, Hamza, Nicolas Fromm, and Sabith Khan. 2021. “A Case for Dark Horse Thinking? Re-Imagining Group Asylum.” In Power in Vulnerability: A Multi-Dimensional Review of Migrants’ Vulnerabilities, eds. Nicolas Fromm, Annette Jünemann, and Hamza Safouane. Heidelberg: Springer, 251–73.

- She, Xiaoye. 2021. “Teaching IR through Short Iterated Simulations: A Sequenced Approach for IR Courses.” In Signature Pedagogies in International Relations, ed. Jan Lüdert. Bristol: E-International Relations, 147–65.

- Shulman, Lee. 2005. “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions.” Daedalus 134 (3):52–9. doi: 10.1162/0011526054622015.

- Smith Heather, A., and David J. Hornsby. 2021. “Introduction: Teaching International Relations in a Time of Disruption and Pandemic.” In Teaching International Relations in a Time of Disruption, eds. Heather A. Smith and David J. Hornsby. Cham: Springer, 1–7

- Uebernickel, Falk, Walter Brenner, Therese Naef, Britta Pukall, and Bernhard Schindlholzer. 2015. Design Thinking: Das Handbuch. Frankfurt: Frankfurter Allgemeine Buch.