ABSTRACT

The shift of society toward sustainable food culture requires collectively challenging meat and dairy-based diets and their role in current practices of eating. This study focuses on how discussions in social media can facilitate reconfiguration in eating. Three practice-theoretical perspectives – practices constituting of elements, eating as a compound practice, and communities of practice – afford us with analytical tools to investigate eating and how the constituting elements are negotiated and recrafted in social media discussions across the compound practice. As empirical data, we use altogether 14,250 social media messages on the Finnish Vegan Challenge campaign. By combining qualitative content analysis with topic modeling, we capture the various themes occurring in these discussions and their relation to changes in eating practices. The results show that within these discussions, social learning among peers covered the whole sphere of eating-related practices from production and distribution to purchasing and cooking vegan food, and to sharing stories and experiences of veganism. Our findings illustrate how these discussions can be seen as forming a reconfigurative community of practice, which can potentially support and facilitate social change of eating toward sustainability also outside the Vegan Challenge community.

Introduction

Although veganism is not a new phenomenon as such, in recent years vegan eating has gained heightened visibility in public discussion in many Western countries. The reasons for this include the intensifying discourses on animal rights-related aspects which lie at the heart of veganism (e.g., Janssen et al. Citation2016; Wrenn Citation2019), the environmental and health-related problems caused by animal production and consumption (Steinfeld, Gerber, and Wassenaar et al. Citation2006; Willett, Rockström, and Loken et al. Citation2019), and a new interest in vegan eating as part of sustainable lifestyle political movements (Jallinoja, Vinnari, and Niva Citation2019; Micheletti and Stolle Citation2006). Despite such apparent change in eating-related discourses, meat and dairy continue to form a routinized part of daily patterns of eating in Western societies. Due to the prominent position of animal-based foods in both everyday and festive meals and the many positive cultural meanings ascribed to them (e.g., Fiddes Citation1991; Piazza, Ruby, and Loughnan et al. Citation2015), reducing – let alone giving up – the eating of meat, milk, and eggs has proven challenging, as it requires not only changing the accustomed ways of buying, cooking, eating, and socializing around food, but also breaking the established norms of what is considered “proper food” (Greenebaum Citation2012; Niva et al. Citation2014).

In this study, we start from the notion that no enduring change in eating is possible without reconfigurations in intertwined, differentiated, and interlinked practices that steer both daily consumption and processes of production and policy (Kaljonen et al. Citation2019; Laakso Citation2017; Warde Citation2016). From this practice-theoretical perspective, any durable lessening of animal-based foods in eating requires changes not only in better availability of plant-based products but also in collective know-how of using them and in the social and cultural meanings related to animal-based foods and their alternatives. These requirements are heightened in the case of veganism, which demands a great deal of practical effort of finding suitable alternatives, developing new cooking skills, and, even today, tolerance of social stigma (e.g., Greenebaum Citation2018; Twine Citation2018). Practices also differentiate and diffuse socially, underlining the importance of social interaction and contestations in their reconfiguration. As noted by Neuman (Citation2019, 90), social practice theories give us tools to better understand the dynamics of food-related social change, such as the shift toward more sustainable diets.

Consumption is bound up with everyday social life in specific contexts and communities, making it is necessary to understand why and in what ways people engage in various kinds of consumption activities (Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014, 26). In contemporary societies, social media (by which we in this article mean platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and discussion forums) provides spaces for negotiating practices of eating (Pohjolainen and Jokinen Citation2020; Rödl Citation2019) and building (virtual) communities (Mann Citation2018). These platforms can thus be understood as material-discursive environments for learning about vegan food practices and provide a fruitful context for studying how eating is disrupted, negotiated, and reconfigured.

This study aims to analyze the role of social media in the reconfiguration of food practices. More specifically, we ask in what ways social media discussions introduce new meanings, provide instruction and guidance, and encourage novel engagements with food, and whether they can be conceptualized as forming a reconfigurative community of practice, for changing eating toward veganism via collective learning. As empirical data, we use social media discussions relating to a Finnish Vegan Challenge campaign encouraging people to test vegan diet for one month, which we analyze using topic modeling and qualitative content analysis.

By reconfiguration, we refer to changes in the organization of the practice of eating or in relations between various food-related practices, which “engender long-term transformation in what counts as a normal and acceptable way of life” (Shove Citation2014, 419). Following Laakso et al. (Citation2020), unlike just any kind of change in practices, reconfiguration is a goal-oriented process (toward sustainability, for instance) that includes collective contestation and negotiation within the community of people performing the practice, and in which the changes in social norms and conventions hold a fundamental role. Since reconfigurations commonly involve the articulation of components, which can destabilize the existing practices (Welch Citation2020, 69), a reconfiguration in the context of vegan eating could thus be conceptualized as a problematization of existing practices of eating in the context of everyday life and socio-technical, political and economic change, and consequent development of novel practices.

In the next section, we introduce our theoretical framework and briefly outline how daily practices may be reconfigured. Thereafter, we describe the Vegan Challenge campaign and its efforts to encourage Finns to try out a vegan diet. The subsequent sections present materials, methods, and results. In the concluding section, we provide some insights into the role of social media discussions in reconfiguring everyday eating.

Theoretical framework: social practices and their reconfigurations

Social practice theories have become increasingly popular in understanding and explaining consumption, everyday life, and social change, and are widely applied in the study of food and eating (see, e.g.,, Evans Citation2012; Halkier Citation2009, Citation2017; Maguire Citation2016; Warde Citation2013, Citation2016; see also Neuman Citation2019), including plant-based eating and veganism (e.g., Jallinoja, Niva, and Latvala Citation2016; Twine Citation2018). Three theoretical insights in practice theories are of specific interest in this paper: the composition of practices based on interlinked elements (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012), the understanding of eating as a compound practice (Warde Citation2016), and the social learning provided by communities of practice perspective (Lave and Wenger Citation1991).

Warde et al. (Citation2007, 364) describe a practice as routinized behavior guided by “shared understandings, know-how, and standards of the practice, the internal differentiation of roles and positions within it, and the consequences for people of being positioned relative to others when participating”. Different characterizations and categorizations of the “elements” constituting a practice exist, but probably the most widely used is Shove et al.’s (Citation2012) illustration of practices consisting of interlinked elements of meanings, materials, and competences. In eating, meanings includes social norms, standards, and expectations of what is good and proper eating; materials cover the material environment in which food acquisition and eating take place, such as food items, kitchen appliances, and other material artifacts needed in eating, as well as bodies that incorporate the food; and competences refer to practical understandings and knowledge about food and eating as well as various management skills, such as knowing recipes, shops, and products and being able to manage the food budget.

Eating involves multiple practices, since it entails performances of producing, distributing, purchasing, preparing, and cooking the food, as well as successfully organizing the eating event and managing food waste (Kjærnes, Ekström, and Gronow Citation2001; Laakso Citation2017). Warde draws on the distinction of Schatzki (Citation1996) between dispersed practices, such as following rules, explaining and imagining, and integrative practices, such as farming and cooking practices. According to Warde (Citation2013), on one hand, eating can be seen as a typical integrative practice, but, on the other hand, eating is more than one integrative practice: Warde (Citation2013; see also Warde Citation2016) notes that it takes place at the intersection of at least four practices, which are the supplying of food, cooking, organizing meal occasions, and providing esthetic judgments of taste. This makes eating a compound practice, i.e., “formed from the articulation of different practices” (Warde Citation2016, 86). Consequently, approaching eating as a compound practice makes its systemic nature, from production to waste management more visible, and highlights that the meanings, materialities, and competencies attached to it are linked with wider societal frameworks beyond the daily performance of eating.

Eating practices, especially when they are alternative or innovative, can be approached as a collective or communal form of consumption (see, e.g.,, Noll and Werkheiser Citation2018). The concept of communities of practice (Lave and Wenger Citation1991) has been used to examine and explain behavior and learning in both online and offline communities (Smith, Hayes, and Shea Citation2017). According to Wenger (Citation1999), a community of practice is a community with a shared domain or common focus (i.e., the community is involved in a ’joint enterprise’, which can in the context of the present study be seen as vegan eating), shared activities, which establish norms and expectations (“mutual engagement” in trying out vegan eating), and common practice arising from shared experience, tools and resources (“shared repertoire” of producing meaning and using vegan products) (see also Smith, Hayes, and Shea Citation2017). In this thinking, a difference is made between “learning as doing”, for example, by sharing past experience and knowledge; “learning as belonging”, meaning that the group is at the heart of the activity; and “learning as becoming”, where having a role in the group supports the development of self-identity (Wenger Citation2009).

As policymakers and activists campaigning for more sustainable food consumption know, changes in practices may be slow to take place. Warde (Citation2016) explains that in everyday life, people come to have shared practical and temporal routines, which lead them to repeat activities more or less similarly day by day. Such routines relate, for example, to the interaction between prior experience of activity and the environment, coordination with other activities and with other people toward whom obligations exist or exposure to expert advice encouraging certain types of action (e.g., sequencing and timing of eating events during the day). The routines may also be shaped by social contexts in which other people steer action using encouragement and example, or exercise of social control and restraint (Laakso Citation2017; Warde Citation2016).

While social practices may be difficult to change purposefully, they are not fixed. Enduring and relatively stable practices (and complexes of practices) exist only because they are consistently and faithfully reproduced (Shove and Walker Citation2010) and a change can occur in various ways. First, it can start with changes in practice elements, leading to an altered form of the practice, or, perhaps, the collapse of the practice as it was previously known (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012). However, practice reconfiguration often calls for alterations in all elements – instead of mere consciousness raising or technological innovations, reconfiguration requires that also the tacit, unspoken social rules and values are collectively contested and brought out into the realm of discussion, debate, and argument (see also Wilk Citation2009). Vegan products provide an example of how material change may instigate reconfiguration in eating: the recent rise of vegan foods on the market has opened up opportunities for the development of novel meanings and competencies, enabling changes in everyday performance also among non-vegans (Jallinoja, Vinnari, and Niva Citation2019). Second, in addition to reconfiguration in the elements of a practice, change may also start from “outside” when a transformation in one practice initiates or contributes to a concurrent change in another, adjacent practice. A well-known example of this is the transformation of the social organization of meals in families following the changes in work life and leisure activities in recent decades (Warde Citation2016). Similarly, vegan eating has gained traction as part of both the animal rights movement and a more general trend toward healthy lifestyles (Jallinoja, Vinnari, and Niva Citation2019).

Learning is essential for practice reconfiguration. Learning in communities of practice allows a broad understanding of what it is that needs to be learned (cognitive process), as well as participation in the practice through specific sites of consumption or social contexts, such as peer networks, where norms and values are discussed and debated (practical process) (Lave Citation1991). The key here is to view learning not as an individual experience but as participatory and social (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). In public policies, however, the overall “learning proposition” is often based on a narrow understanding of what is significant to people in their everyday lives, ignoring the specific social practices that make learning meaningful (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). Stories are useful in this respect: as “packages of situated knowledge” they can be shared with newcomers in a community of practice (Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014). Thomas and Epp (Citation2019) suggest the concept of “envisioned practice” to refer to people’s stories for enacting a practice and for translating the cultural script of a practice to everyday performance. While the envisioned practice may not always come true as imagined, the abilities to envision potential relationships between elements to reconfigure the practice of eating are something the social media communities can provide.

Although earlier studies have studied communities of practice and other forms of learning and knowledge sharing on social media platforms (Ahmed et al. Citation2019; Gilbert Citation2016), they have thus far paid little attention to everyday practices and their change. In this study, we are interested in the potential of social media discussions as reconfigurative communities of practices: while, as presented above, communities of practice provide ample possibilities for the reconfiguration of practice, such change does not necessarily happen on its own but requires active work by and within the community. The Vegan Challenge social media community exists because it aims at assisting people in changing their habituated practices. Here, the combination of the three practice-theoretical insights presented above – practices constituting of interlinked elements, eating as a compound practice, and communities of practice perspective – becomes useful: as we show in the following, the Vegan Challenge discussions provide a community of practice for negotiating and recrafting the constituting elements of the compound practice of eating, thus supporting reconfiguration.

Vegan Challenge

Following the example of similar challenge campaigns internationally, the aim of the Vegan Challenge (Vegaanihaaste) campaign is to encourage people to try out vegan eating for one month’s time. The campaign is organized by a Finnish animal rights organization Justice for the Animals (Oikeutta eläimille), a nonprofit organization promoting veganism and campaigning against animal cruelty. The campaign is widely publicized in Finland: it is promoted in the media and, e.g., on outdoor digital screens, and people circulate it on social media and challenge each other to take part. The campaign tries to create a positive and easy-going image around vegan eating by depicting the encouraging stories of well-known Finns who have taken up the challenge, providing practical and accessible information in an optimistic tone and without making people feel guilty about their (non-vegan) choices, and being open to everyone interested in plant-based eating. The Internet front-page of the campaign encourages the readers: “Taste the future – try out vegetarian food for one month in January!” (https://vegaanihaaste.fi/, 24.11.2020).

The campaign has been organized every year since 2013. The main event is during January, but the challenge can be taken any time of the year. Over the years, more than 80,000 people in Finland have taken the challenge (Vegan Challenge Citationn.d.). Anyone can participate in the one-month challenge free of charge by registering on the campaign’s web page. Registered participants receive a daily newsletter via e-mail, including recipes and practical information about vegan eating, and a personal tutor who answers questions via e-mail or social media if needed. This way, the campaign supports experimenting with vegan eating.

Between 2015 and 2018, the campaign administered a Facebook event, which was open for anyone, in addition to a closed Facebook group – intended for the registered participants only – that eventually replaced the event in 2019. The presence of the campaign on other social media platforms, such as Twitter and Instagram, has been increasing especially within the past years. In recent years, the campaign has also had commercial partners offering recipes, products, and competitions, and it has reached celebrities to acquire visibility. Moreover, the campaign has organized tours and participated in events, such as vegan fairs, around Finland.

According to a survey made by the Vegan Challenge organizers, a one-month campaign is an efficient way for a diet change: almost 80% of the participants have continued with a vegan or almost vegan diet, and virtually all others have reduced the share of animal-based food in their diet after the challenge month (Vegan Challenge Citationn.d.). However, there might be some non-response bias, as those who have struggled or given up the challenge might have been less likely to respond. Studies have also shown that the sales of plant-based milk increase significantly every January in Finland (Isotalo et al. Citation2019), and, despite being still rather marginal, the vegan diet has gained popularity in Finland in recent years (Jallinoja Citation2020). However, the more fine-grained reasons for whether, why, and how Vegan Challenge may be conceptualized as a reconfigurative community of practice supporting change remain less studied.

Materials and methods

Social media posts as data

The data used in this study consist of social media posts on Vegan Challenge. We used a dual-strategy of combining distant-reading (Moretti Citation2013) and in-depth qualitative analysis to gain a broad understanding of this online community of practice.

First, an extensive dataset of messages posted on social media platforms was acquired from Futusome, a commercial provider that collects Finnish social media content (see Ojala, Pantti, and Laaksonen Citation2018). Its database was queried for all public messages sent between January 2015 and March 2019 that included the word “vegan challenge” (vegaanihaaste in Finnish) in the message body or headers, yielding a total of 20,731 messages on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, online discussion forums, and blogs. Information on the poster’s identities was removed before analysis, to secure the anonymity of the poster. Besides, after an initial analysis, we ended up removing Instagram and YouTube from the dataset due to their focus on photographs and videos, making the analysis of the text difficult, as well as retweets from the Twitter data.

Second, since Futusome data does not cover Facebook events, we collected the discussions in open Vegan Challenge events between the years 2015 and 2018. This also enabled us to study the interaction between the participants, as Futusome removes the individual posts from their context. This interaction can also be seen as producing the performativity of practices (see Halkier and Jensen Citation2011), despite our social media data being by definition part of the discourses, i.e., sayings, related to veganism. The Facebook events discussions, including altogether 435 posts and 1,435 comments to these posts, were saved in pdf form and were then converted to a text file. In this process, the names of the event participants were removed for anonymity.

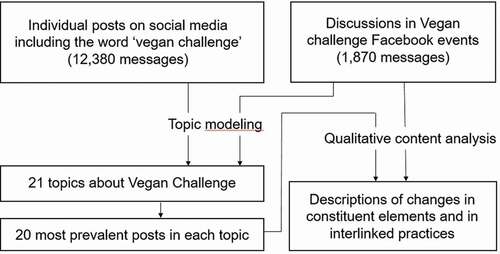

The social media data were pre-processed, lemmatized and a standard set of Finnish stop words (such as and or, if) were removed from the corpus, along with words such as “vegan”, “challenge” and “january” that had defined the data collection and thus appeared in all the documents. provides a summary of the data used in the study.

Table 1. Summary of the data

Topic modeling

Topic modeling is a computational methodology suitable for organizing and analyzing large sets of unstructured documents, such as posts on social media. In topic modeling, the probabilistic algorithm identifies words that frequently appear together and forms a collection of clusters (i.e., topics) from the examined sets of texts (i.e., a corpus). The specific topics thus emerge from the patterns uncovered by the algorithm, instead of being predetermined by the researcher (Mohr and Bogdanow Citation2013). With topic models, researchers can discover new patterns and discourses in the text data and analyze much larger collections than would be possible by hand (see, e.g., Underwood Citation2012). In our mixed-methods process, we clustered our data using topic modeling, as the first step of the analysis. We then validated and interpreted said “topics” – making sure they actually represent a meaningful discussion in the data – and proceeded with theory-driven analysis using these chosen topics.

For the clustering, we used the MALLET toolkit, which is an open-source software package for topic modeling using Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) (Blei, Ng, and Jordan Citation2003; McCallum Citation2002). LDA assumes that there are a set of topics in a collection, where a topic is formally defined as a distribution over a given vocabulary, i.e., all the words that were used in the corpus. Terms that are prominent within a topic are those that tend to occur in documents together more frequently than one would expect by chance. LDA-based approaches have been found to work better in social science research when compared to dictionary-based automatic classifications, but they do require more interpretation (Guo et al. Citation2016).

Topic modeling is an iterative research process in the sense that we needed to find an adequate number of topics to find the best fit with our corpus and our research question. A small number of topics are suitable when the research aims to describe on a general level the different topics of the discussion. In our data, all discussions are already about veganism and the Vegan Challenge, and since our research questions call for recognizing different types of practices and practice elements in the discussions, we needed a higher number of topics. The danger with too many topics is that it might produce topics that are difficult to differentiate and have limited analytical strength. Therefore, we tried models with 5–10, 15, 30, 50, and 100 topics and finally opted for a solution of 50 topics, enabling us to capture the variety of discussions and practices around veganism, while still having large enough clusters for analytical clarity. Defining the number of topics in an iterative manner also has the benefit of increasing the robustness of the analysis – by trying out a different numbers of topics, we were able to make sure that the topics in our model were not spurious.

Following Ylä-Anttila, Eranti, and Kukkonen (Citation2020), for each of the 50 topics, we checked the 20 keywords representing the topic provided by the algorithm, giving them an interpretation (“what is this about?”), which we then validated by reading the posts best representing each topic, also provided by the algorithm. The topics, as well as an assessment of the overall proportion of the corpus assigned to a given topic (Dirichlet parameter), can be found in Appendix A. Of the 50 topics, we chose 21 for further analysis (see Appendix A for the list of topics and their keywords). We excluded from the analysis topics that were not relevant for the analysis of eating practices, such as topics focusing on event advertisements and vegan menus in restaurants. Furthermore, we excluded topics with Dirichlet parameter less than 0.02, since these topics were not as consistent and were consequently more difficult to interpret than the ones representing a more sizable proportion of the data.

Qualitative content analysis

Topic modeling does not require any a priori interpretations as such, except for the determination of the examined number of topics. Yet, as the methodology does not examine the meanings of the words studied, their interpretation becomes a part of the research task. An important part of the study was thus a qualitative content analysis that complemented the topic modeling by an in-depth reading of the posts. Qualitative content analysis, which refers to the interpretation of the content of text data through the systematic process of coding and identifying themes and patterns (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005), is the most commonly used approach to analyze social media content (Snelson Citation2016).

For our qualitative content analysis, we selected posts that the algorithm had identified as best representing each of the 21 topics (20 per topic). Of these 420 posts, more than four out of five were posted on Facebook or Twitter, representing the high share of posts in these social media platforms in the entire dataset. Two out of three posts were made by private persons despite the active presence of the campaign organizers, other NGOs (such as Friends of the Earth), and businesses, such as restaurants and grocery shops, in social media during the campaign.

We also included, in the analysis, the discussions in Vegan Challenge Facebook events (including 435 posts and 1,435 comments). This allowed us to capture the interaction between the participants when discussing the themes raised in the events by the participants themselves or by the organizers. Of these posts, approximately one-fifth was posted by the campaign organizer. However, the share of the organizer’s posts increased in 2018, which was the last year of the study, and during which much of the Facebook discussion had already moved to a private Facebook group. Other actors, such as businesses, were less present on Facebook events, leaving most of the room for interaction among the participants.

In our analysis, we examined whether similar themes arose with both computational methods and qualitative reading, and the content analysis allowed us to deepen and elaborate on the themes identified via topic modeling. During the deductive coding and categorizing of the data (see Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005), based on our theoretical framework, we looked into (1) the compound nature of eating, i.e., food-related practices that were present in the discussions, how they linked with vegan eating, and what role these practices had in the transition toward vegan eating; (2) the practice elements (materials, meanings, competences) ascribed to eating and their dynamics; and (3) occurrences of learning as part of the community of practice.

illustrates the analysis process. In short, topic modeling provided us an overview of what was discussed in social media related to the Vegan Challenge, whereas qualitative content analysis allowed us to dig deeper into these topics and if and how they are related to reconfiguration in eating practices.

In the following, we have categorized the 21 topics and the discussions they entail into three sets of practices, which together constitute the compound practice of eating. As the practices present in the discussions were related not only to everyday, functional practices of those engaged in the process of habituating veganism (purchasing, preparing, and cooking), and reflections on exhibiting and experiencing veganism but also to the adjacent practices of food provision (producing, selling and catering that play a role in enabling vegan eating), we include these as one realm of the compound practice. We introduce the discussions within each topic and the changes in practice elements these discussions relate to, as well as the processes of learning identified in these discussions (see Appendix A). For anonymity, we are not providing names or the sources of the individual posts but only the topic in which the post is included.

Results: reconfiguration across the compound practice

“Functional” practices: purchasing, preparing, and cooking

The practices of purchasing, preparing, and cooking that were actively focused on in the discussions illustrate the compound nature of eating. The purchasing practices under discussion focused on what to buy from stores, where to find vegan foods, and which restaurants and cafés to visit if you were a vegan, as well as how to make sure that what you buy is actually vegan, representing essential materials and competences of vegan eating (topics 5 and 6 in Appendix A). Discussions related to cooking and baking practices were to a high degree about inquiring and sharing vegan recipes, and practical tips for cooking and making vegan versions of favorite foods and easy, quick everyday meals (topics 12, 16, and 18). These discussions were also about skills related to tuning and modifying the recipes shared by the campaign, to make them more fit for people with intolerances. In terms of Warde (Citation2013), we suggest that such incorporation of veganism into established and “normal” patterns of eating and recipes implies an ongoing process of institutionalization of vegan practices.

Purchasing, preparing, cooking and baking were thus strongly related to skills, competencies, and materialities of vegan eating: how to do things properly withvegan products, which may not always function the same way as animal-based products. In these discussions, the ways to replace meat and dairy products with vegan alternatives was an important focus: what these alternatives are, where to find them, what they are made of, how to prepare them, what they taste like, what they cost and what are the affordable alternatives, and how suitable they are for those with intolerances or allergies. Some examples of practical questions were related to taste and esthetic aspects of food, such as how to make tofu taste good and how to replace eggs in cooking and baking (see also Twine Citation2018):

Does oat milk behave in cooking the same way as normal milk? I could also ask someone knowing these things, if you can replace egg somehow in e.g., soy burgers? :) (Topic 16, forum post, 2016)

Replacement of coffee milk gained substantial attention in discussions about the best substitutes and their usage, such as practical advice about the order in which milk and coffee should be poured into the cup for best results and about how the substitute behaves when heated (topic 14). Such inquiries and tips provided for others illustrate the culturally significant aspects: in Finnish food culture, coffee is important. Another theme in substituting dairy products was the use of items that are not so self-evident to replace, such as sour cream or cheeses (topic 5). The discussants also provided practical advice about what to put on the bread and what kinds and brands of cakes and sweets are vegan (topics 11 and 15).

Holiday seasons were critical, as many traditional holiday specials include meat and dairy: the Christmas ham, Easter lamb, and grilled sausages on midsummer’s eve. In these discussions, many brought up how most of these meals also traditionally include many vegetarian, or even vegan, elements, and there were plenty of options for replacing meat and dairy items. These discussions on meat and dairy substitutes again illustrate that certain meanings and ideas of what is proper can become rather “narrow”, that many animal products possess a significant position in the Finnish cuisine and annual festivities, and that at least in the initial stages of reconfiguration it is important for vegan alternatives to be able to imitate these products for veganism to gain a foothold (see also Fuentes and Fuentes Citation2017).

Crowdsourcing also occurred in the form of some people compiling and sharing tips and weekly or even monthly menus for families with children, to make the everyday vegan living more manageable. People were asking frequently for help from their peers, questions relating to dietary limitations, syndromes, exercise, small children, vitamins and nutrients (especially iron and vitamin B12), and whether to start veganism slowly or quickly (topic 17). These illustrate the need to recognize the coordination with other activities and with other people toward whom obligations exist (Warde Citation2016). Here, people seemed to rather rely on peer support than seeking for this information independently, which underlines the collective aspect of the Vegan Challenge in reconfiguring eating.

Adjacent practices: production and distribution of food

In addition to discussions related to day-to-day performances of purchasing, preparing, and cooking, also more distant practices of production and distribution of food and related policies were discussed. These discussions focused for a large part on the ethical and environmental problems of animal production, the domesticity of production, and food safety (topics 7–10). Not surprisingly, meanings related to ethical and environmental issues were prevalent in discussions on the benefits and justifications of veganism:

There is no returning to old habits – at least a lot needs to happen in the circumstances of piggeries and hen houses, for me to allow myself to [eat meat] (…) I recommend [Vegan Challenge] for everyone who likes this planet. (Topic 7, Facebook post, 2016)

Production and distribution-related topics also included discussions on the complexities of “borderline” food items such as soy, avocados, or almonds (because of the ecological problems caused by their farming) or honey (because of the exploitation of bees). There was disagreement on whether organic meat production is any better in terms of animal rights or environmental sustainability compared to non-organic meat, and the environmental impacts and ethics of domestic animal production and import of vegan foods were debated (topic 9). These themes illustrate how the meanings related to sustainability reach across the practices that form the compound practice of eating, and how the ecological, ethical, and social aspects of sustainability were deliberated upon and learned about as part of the reconfiguration process.

As Warde (Citation2016) has noted, exposure to expert advice can support practice change in eating: the posts relating to production and distribution indeed focused on providing and sharing information, e.g., giving up-to-date and research-based information about the environmental impacts of food production, and they often resorted to expert knowledge and scientific research (topic 19) as codifications of issues that need to be paid attention to in proper eating. Environmental and ethical questions were also the themes in which the campaign organizers had made a significant share of the posts, which illustrates their role in information provision and diffusion of knowledge related to veganism. However, expert knowledge was also utilized the other way around, by utilizing the everyday expertise and experiences of the Vegan Challenge participants (topic 19), as restaurants and food manufacturers asked for their feedback. This illustrates how vegan products can be co-designed by bringing producers and consumers on the same platform.

The discussions on adjacent practices were thus to a high degree related to gaining knowledge about the different impacts of food production and of various food items, food-related policies, and the role of institutional practices, as well as nurturing meanings related to sustainability. These discussions also illustrate how people seek ways to defend their decisions. Moreover, the discussions showed some self-criticism about veganism not necessarily being “the best diet in the world, nor healthiest”. As described in one post on Facebook, as long as soy is produced unsustainably and vegan food is not automatically healthy, it is “of mental laziness” to think that a vegan diet beats other diets in all respects. These discussions also led to arguments about the pros and cons of different alternatives, such as freeganism, and their definitions: are you vegan if you sometimes eat leftover meat? Such reflections, in turn, also led to participants gaining new knowledge, competencies, and justification for changing their eating practices, and show that reconfiguration processes involve reflexive deliberation about both established and novel practices.

Other adjacent practices, such as policy practices related to agriculture and food prices, as well as to what kinds of foods are being served, for example, in schools, were also discussed. However, these topics were left outside the in-depth analysis due to their Dirichlet parameter being less than 0.02. However, and based on our findings, the reconfiguration of practice requires not only changes in everyday performance but addressing the sustainability concerns throughout the compound practice.

Experiential practices: “exhibiting” and deliberating veganism

Organizing a successful, or pleasant, eating event, one of the key compounds in the practice of eating, was also actively discussed and reflected upon. These topics related to competencies of explaining veganism to others, finding one’s own “vegan identity” and sharing expectations and experiences related to diet change, and were the most prevalent topics in the whole corpus (see Appendix A).

In these discussions, people were seeking peer support “to be vegan in a non-vegan world” (Greenebaum Citation2012, 137) – to challenge the prevailing meanings, norms, standards, and unspoken rules of the dominant animal-based eating, such as the “physical need to eat meat”, and ways to respond to people with doubts toward veganism (topics 13 and 17). In these discussions, stories were important. For instance, one topic focused specifically on examples from top athletes who are vegan, providing “iconic” and extreme examples of how it is possible to be vegan and foiling the assumptions about vegan diet not being enough if you need a lot of energy (topic 20). Another set of topics focused on experiences of the participants: a reflection on what it is like to be vegan, on the pleasurable experiences related to giving up meat (such as feeling light and well), on the potential difficulties, as well as sharing tips on “how to survive” (topics 1 and 3). Many of these posts were very personal, describing successes and obstacles faced and encouraging peers:

After becoming a vegan myself, I must admit how ridiculous it now feels how I have pulled back myself before, as this is not that special. Vegan Challenge is about doing things together, as a group. (Topic 1, forum post, 2016)

These kinds of stories and related discussions are important for goal-oriented practice reconfiguration, as they can be seen as means of encouragement and example-setting (Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014; Warde Citation2016). Indeed, several studies have found that vegans need to develop ways to beat the vegan stigma and have the skills to respond to the questioning of their lifestyle and commitment by friends and families (Twine Citation2014; Niva, Vainio, and Jallinoja Citation2019), and it appears that the same challenges were faced by also people who are not necessarily committing to veganism for the rest of their lives but for a short trial period.

Lastly, one set of topics covered envisioning practices related to a vegan lifestyle (see Thomas and Epp Citation2019), as the participants were sharing their excitement, enthusiasm, and hope for, or a commitment to, “a turn” toward healthier and more sustainable and ethical lifestyles as part of the New Year’s promises (topics 2 and 21). These ideas represent the aims to embed environmental and ethical justifications in everyday practices, of which eating is one. However, promises of these kinds of lifestyle changes are also expected at the beginning of New Year, which allows some momentum – or even pressure – for the campaigns such as Vegan Challenge to attract people to join and announce their participation to others in social media. However, there was also a merciful tone in the discussions: one of the topics included posts about not being “100% vegan” – and how it is acceptable. As described by one participant on Facebook, “small steps are enough” and joining Vegan Challenge can support reductions of meat and dairy products in the diet, instead of the challenge having to be “a total everything away change” (topic 4). This is an interesting feature that illustrates the open and inviting nature of the challenge community, encouraging people to join and learn new practices without demanding full and outright commitment to veganism.

Discussion: Vegan Challenge as a reconfigurative community of practice

The Vegan Challenge social media campaign provided the participants (both registered and not registered, but nevertheless taking part in social media discussions) a community for interaction focusing on a variety of elements significant in practice change: in addition to reciprocally teaching and learning skills and competencies related to buying, preparing and cooking vegan foods, the discussions offered science-based knowledge and tools to respond to popular and sometimes unfounded beliefs related to environmental, ethical or nutritional aspects of vegan diets. However, such information provided by the campaign organizers or peers was not always accepted at face value, but it was contested, and justifications and evidence were asked for. Moreover, the discussions covered difficult themes related to being marginalized or belittled among friends or relatives, having few vegan options due to poor supply in stores (e.g., in rural areas), or difficulties in engaging in vegan eating with low income (cf., Twine Citation2014; De Backer et al. Citation2019). People nevertheless also shared encouraging success-stories about parents or partners becoming vegan and veganism being – after all – easy and convenient, as well as, for example, simple, inspiring food pictures (on fresh vegetables and fruits and colorful, tasty, light, and wholesome dishes). Unlike in previous studies, the discussions thus covered not only the cooking event but variety aspects of the compound practice, illustrating that the challenges for meat reduction lie not only in knowing how to prepare vegan food but in many meanings, materials, and competences holding the compound practice together (cf. Pohjolainen and Jokinen Citation2020).

Based on these findings, Vegan Challenge can be understood as a community of practice, in which people join to experiment with and learn about various combinations of elements related to a new practice of vegan eating. The vast expertise in the campaign and of peers sharing their knowledge and experiences, and the opportunity to participate in the practice by being “challenged” to test veganism can be seen as the two steps of the social learning process identified by Lave (Citation1991). Based on our data, learning in the campaign was indeed participatory and social, as some participants relied to a high degree on the peer expertise and support in social media, and these peer networks provided a platform for discussing and debating norms and values previously unspoken and uncontested (Sahakian and Wilhite Citation2014). The participants also demonstrated various ways of performing practices related to veganism, supporting changes in different elements of these practices and potentially helping build both the envisioned and enacted practice in the light of how others do things (Thomas and Epp Citation2019; Warde Citation2016). As the discussions covered not only the success stories and having fun but also challenges and sensitive themes, they offered participants many means to build new social ties, collective identities, and a sense of belonging (see also Greenebaum Citation2012). Following Anderson (Citation1983), Niva and Jallinoja (Citation2018) call these “imagined communities” that can support the shift toward more sustainable consumption patterns in the age of individualization and erosion of traditional communities. If, as Twine (Citation2014) and De Backer et al. (Citation2019) argue, in vegan transition social relationships in a largely non-vegan world form the most difficult obstacle to resolve, communities such as Vegan Challenge with strong social media presence and participative features can help potential practitioners to get started with engaging in vegan eating.

The fact that the community is built around a “challenge”, and explicitly aims at change in practices toward sustainability, makes it reconfigurative – in comparison with social media communities of practice that are more explicitly aimed at, for example, professional development (see Ahmed et al. Citation2019). Social media was used to discuss vegan eating in a wider context of ecological and social sustainability, ethics, and health issues, among more practical concerns related to buying and preparing vegan foods. The discussions illustrate how people collectively challenge the prevailing norms and expectations, and seek justification and resonance for veganism as well as ways to defend their decisions. These justifications, along with the expert advice and skills to communicate about veganism, can be used also outside the social media community. Vegan products and recipes were co-designed by bringing supply and demand on the same platform, also facilitating the shifts in materials, meanings, and competencies outside the community and the sphere of everyday eating. With the support of experienced campaigners and other means utilized in the campaign, the discussions challenging the present practices of eating can effectively create hype and make veganism seem more interesting, trendy, and non-marginal phenomenon, as exemplified in the recent rise of the popularity of vegan products also among omnivores and flexitarians (Jallinoja, Vinnari, and Niva Citation2019). These kinds of reconfigurative communities of practice can thus support a wider change of everyday eating toward sustainability also outside the Vegan Challenge community.

Conclusions

This study aimed to analyze the role of social media in the reconfiguration of food practices. More specifically, we asked if social media discussions can be conceptualized as a reconfigurative community of practice, for shifting eating toward veganism via collective learning. In the following, we finish the article by specifying what conclusion can be made based on our results and how our study contributes to discussions of sustainable eating.

Given that everyone can post on social media about Vegan Challenge, the community formed around these discussions is anything but closed. However, it could still be seen as a community of practice, allowing a broad understanding of what it is that needs to be learned, as well as participation in different sub-practices that constitute the compound practice of eating. The Vegan Challenge thus supports a combination of participatory learning opportunities across the practice (see Lave Citation1991; Lave and Wenger Citation1991). What makes this community reconfigurative by nature and differentiates it from those typical in analyses of communities of practice focusing on professional development, is the general aim of Vegan Challenge to contribute to a wider social change toward sustainable eating practices.

Our study shows that the Vegan Challenge discussions supported the change in elements across the compound practice: people were seeking practical advice related to competences and skills of buying, cooking, and eating vegan food, as well as looking for, validating and reinforcing the meanings associated with vegan food and veganism, while questioning and challenging those related to their previous, animal-based diets. What is significant is that the discussions did not focus only on day-to-day activities of cooking or eating vegan food, but the practices covered in the discussions reached the whole sphere from sustainability aspects of production and distribution to communicating about veganism to others and reflecting on the participants’ feelings and experiences. The discussions thus covered not only the practices “in action”, such as those of preparing, cooking, eating, and socializing but also adjacent practices related to food production and distribution and what we call experiential practices of sharing stories related to veganism. The discussions provided an affective community for the participants, which helped them build social and emotional competencies to also deal with their non-vegan social circles (Twine Citation2014). Approaching eating as a compound practice covering the variety of practices thus enabled us to capture the multitude of elements and practices changing in the reconfiguration process, highlighting the importance of changes in all practices, not just individual elements such as meat or dairy substitutes and their availability, for practice reconfiguration.

Moreover, sustainability as a cross-cutting theme, present in all practices mentioned above, was critical for practice reconfiguration, and many aspects of sustainability were actively deliberated upon in the discussions. This underlines the importance of the community in solving conflicts, facilitating learning, and supporting the change of all the elements toward sustainability transition, as well as the notion that practice reconfiguration is a goal-oriented and collective process.

Our results also point that the collective process of reconfiguration is not possible without all actors in the food system being active. For practices to change, all elements, including the materiality of the food itself, need to change, and in this process, policymakers, producers, and distributors are essential. The ongoing reconfiguration is partly made possible by the material transformations and technological developments in the use of plant-based ingredients in food products. Here, further, integrative and coherent policy frameworks are needed to secure the ongoing process toward more sustainable and less animal-based food systems (see, e.g., Reisch, Eberle, and Lorek Citation2013).

This study has provided a novel way of approaching a practice change in a community, as people describe it in their social media presence, and of the ways the practice change is collectively deliberated within the social media discussions. The use of topic modeling as a method enabled us to identify the themes arising from social media discussions on Vegan Challenge on a bigger data set compared to only relying on qualitative analysis. The algorithm in topic modeling provides a pre-defined number of topics, and it is important to acknowledge that the number of topics influences their constitution. However, the fact that we could find similar themes arising from both topic modeling and our qualitative content analysis allows us to suggest that these topics are relevant in discussions about Vegan Challenge and veganism more generally.

By relying solely on the textual presentation of practice, we cannot grasp the “doings” of the practice in a similar depth as by, for example, observations, which is an obvious limitation of the study. However, as discussed by Halkier and Jensen (Citation2011), and Rinkinen (Citation2015), diaries, blogs – or social media discussions – can be seen as expressions of social action, only performed in different social spaces. The focus on social media allowed us to gain research material people had been producing themselves about the enactments of veganism in everyday performances, voluntarily and without any filters or censorships. This provides a unique database of thousands of thoughts, fears, doubts, expectations, and devotions linked with eating and veganism. We hope that our study inspires further research on social media and its role in reconfiguring daily practices toward sustainability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Josephine Mylan, Carol Morris and Minna Kaljonen, as well as the anonymous reviewers, for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Senja Laakso

Senja Laakso is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Helsinki. Her research interests relate to sustainable consumption, everyday life, social practices, and transformation of routines. Her current research projects focus on sufficiency in everyday practices.

Mari Niva

Mari Niva is professor of consumer studies at the University of Helsinki. Her field of expertise lies in the study of practices and the social and cultural aspects of consumption and eating. Currently her research focuses on veganism, meat eating, political consumption, and sustainability transitions in food.

Veikko Eranti

Veikko Eranti is an assistant professor of urban sociology at the University of Helsinki. His research focuses on social media, urban democracy and participation, social theory, and computational methods.

Fanny Aapio

Fanny Aapio is a Master of Science in Environmental Change and Global Sustainability at the University of Helsinki and a project officer at WWF Finland. Her Master’s thesis focused on food literacy of upper secondary school students.

References

- Ahmed, Y. A., M. N. Ahmad, N. Ahmad, and N. H. Zakaria. 2019. “Social Media for Knowledge-sharing: A Systematic Literature Review.” Telematics and Informatics 37: 72–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.01.015.

- Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Editions and NLB.

- Blei, D., A. Ng, and M. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlet Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993–1022.

- De Backer, C., M. Fisher, J. Dare, and L. Costello, eds. 2019. To Eat or Not to Eat Meat. How Vegetarian Dietary Choices Influence Our Social Lives. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Evans, D. 2012. “Beyond the Throwaway Society: Ordinary Domestic Practice and a Sociological Approach to Household Food Waste.” Sociology 46 (1): 41–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416150.

- Fiddes, N. 1991. Meat. A Natural Symbol. London: Routledge.

- Fuentes, C., and M. Fuentes. 2017. “Making a Market for Alternatives: Marketing Devices and the Qualification of a Vegan Milk Substitute.” Journal of Marketing Management 33 (7–8): 529–555. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1328456.

- Gilbert, S. 2016. “Learning in a Twitter-based Community of Practice: An Exploration of Knowledge Exchange as a Motivation for Participation in #hcsmca.” Information, Communication and Society 19 (9): 1214–1232. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1186715.

- Greenebaum, J. 2012. “Veganism, Identity and the Quest for Authenticity.” Food, Culture & Society 15 (1): 129–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175174412X13190510222101.

- Greenebaum, J. 2018. “Vegans of Color: Managing Visible and Invisible Stigmas.” Food, Culture & Society 21 (5): 680–697. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1512285.

- Guo, L., C. J. Vargo, Z. Pan, W. Ding, and P. Ishwar. 2016. “Big Social Data Analytics in Journalism and Mass Communication: Comparing Dictionary-based Text Analysis and Unsupervised Topic Modeling.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 93 (2): 332–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016639231.

- Halkier, B. 2009. “A Practice Theoretical Perspective on Everyday Dealings with Environmental Challenges of Food Consumption.” Anthropology of Food S5: 1–16.

- Halkier, B. 2017. “Normalising Convenience Food?” Food, Culture & Society 20 (1): 133–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2016.1243768.

- Halkier, B., and I. Jensen. 2011. “Methodological Challenges in Using Practice Theory in Consumption Research. Examples from a Study on Handling Nutritional Contestations of Food Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 11 (1): 101–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540510391365.

- Hsieh, H., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Isotalo, V., S.-M. Laaksonen, E. Pöyry, and P. Jallinoja. 2019. “Sosiaalisen Median Ennustekyky Kaupan Myynnissä – Esimerkkinä Veganismi Ja Vegaaniset Ruuat.” Kansantaloudellinen Aikakauskirja 115 (1): 91–112.

- Jallinoja, P., M. Vinnari, and M. Niva. 2019. “Veganism and Plant-based Eating: Analysis of Interplay between Discursive Strategies and Lifestyle Political Consumerism.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Consumerism, edited by M. Boström, M. Micheletti, and P. Oosterveer, 157–179. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jallinoja, P. 2020. “What Do Surveys Reveal about the Popularity of Vegetarian Diets in Finland?” Online. Accessed 1 May 2020. https://www.versuslehti.fi/kriittinen-tila/what-do-surveys-reveal-about-the-popularity-of-vegetarian-diets-in-finland/

- Jallinoja, P., M. Niva, and T. Latvala. 2016. “Future of Sustainable Eating? Examining the Potential for Expanding Bean Eating in a Meat-eating Culture.” Futures 83: 4–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.03.006.

- Janssen, M., C. Busch, M. Rödiger, and U. Hamm. 2016. “Motives of Consumers following a Vegan Diet and Their Attitudes Towards Animal Agriculture.” Appetite 105: 643–651. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.06.039.

- Kaljonen, M., T. Peltola, M. Salo, and E. Furman. 2019. “Attentive, Speculative Experimental Research for Sustainability Transitions: An Exploration in Sustainable Eating.” Journal of Cleaner Production 206: 365–373. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.09.206.

- Kjærnes, U., M. P. Ekström, and J. Gronow. 2001. “Eating Patterns. A Day in the Lives of Nordic Peoples.” In Eating Patterns. A Day in the Lives of Nordic Peoples, edited by U. Kjærne, 25–64. Lysaker, Norway: National Institute for Consumer Research.

- Laakso, S. 2017. “Creating New Food Practices: A Case Study on Leftover Lunch Service.” Food, Culture and Society 20 (4): 631–650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2017.1324655.

- Laakso, S., R. Aro, E. Heiskanen, and M. Kaljonen. 2020. “Reconfigurations in Sustainability Transitions: Systematic and Critical Review.” Sustainability: Science, Policy and Practice17(1): 15–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1836921.

- Lave, J. 1991. “Situating learning in communities of practice.” In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, edited by L. Resnick, J. M. Levine, and S. Teasley, 63–82. Washington, DC: American Psychology Association.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maguire, J. S. 2016. “Introduction: Looking at Food Practices and Taste across the Class Divide.” Food, Culture and Society 19 (1): 11–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2016.1144995.

- Mann, A. 2018. “Hashtag Activism and the Right to Food in Australia.” In Digital Food Activism, edited by T. Schneider, K. Eli, C. Dolan and S. Ulijaszek, 168–184.Oxon/ New York: Routledge.

- McCallum, A. K. 2002. “MALLET: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit.” Online. http://mallet.cs.umass.edu

- Micheletti, M., and D. Stolle. 2006. “Vegetarianism – A Lifestyle Politics?” In Participation. Responsibility-taking in the Political World, edited by M. Micheletti and A. McFarland, 125–145. Boulder & London: Paradigm Publishers.

- Mohr, J. W., and P. Bogdanov. 2013. “Introduction-Topic Models: What They are and Why They Matter.” Poetics 41 (6): 545–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2013.10.001.

- Moretti, F. 2013. Distant Reading. London: Verso.

- Neuman, N. 2019. “On the Engagement with Social Theory in Food Studies: Cultural Symbols and Social Practices.” Food, Culture and Society 22 (1): 78–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15528014.2018.1547069.

- Niva, M., A. Vainio, and P. Jallinoja. 2019. “The Unselfish Vegan.” In To Eat or Not to Eat Meat. How Vegetarian Dietary Choices Influence Our Social Lives, edited by C. De Backer, M. L. Fisher, J. Dare and L. Costello, 91–101. London: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Niva, M., J. Mäkelä, N. Kahma, and U. Kjærnes. 2014. “Eating Sustainably? Practices and Background Factors of Ecological Food Consumption in Four Nordic Countries.” Journal of Consumer Policy 37: 465–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-014-9270-4.

- Niva, M., and P. Jallinoja. 2018. “Taking a Stand through Food Choices? Characteristics of Political Food Consumption and Consumers in Finland.” Ecological Economics 154: 349–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.08.013.

- Noll, S., and I. Werkheiser. 2018. “Local Food Movements: Differing Conceptions of Food, People, and Change.” In The Oxford Handbook of Food Ethics, edited by A. Barnhill, M. Budolfson, and T. Doggett, 112–138.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ojala, M., M. Pantti, and S.-M. Laaksonen. 2018. “Networked Publics as Agents of Accountability: Online Interactions between Citizens, the Media, and Immigration Officials during the European Refugee Crisis.” New Media and Society,21 (2): 279–297. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818794592.

- Piazza, J., M. B. Ruby, S. Loughnan, M. Luong, J. Kulik, H. M. Watkins, and M. Seigerman.2015. “Rationalizing Meat Consumption.” Appetite 92: 114–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.04.011.

- Pohjolainen, P., and P. Jokinen. 2020. “Meat Reduction Practices in the Context of a Social Media Grassroots Experiment Campaign.” Sustainability 12 (3822). doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093822.

- Reisch, L., U. Eberle, and S. Lorek. 2013. “Sustainable Food Consumption: An Overview of Contemporary Issues and Policies.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 9 (2): 7–25.

- Rinkinen, J. 2015. “Demanding Energy in Everyday Life: Insights from Wood Heating into Theories of Social Practice.” PhD Thesis, Aalto University.

- Rödl, M. B. 2019. “Categorising Meat Alternatives: How Dominant Meat Culture Is Reproduced and Challenged through the Making and Eating of Meat Alternatives.” PhD Thesis, University of Manchester.

- Sahakian, M., and H. Wilhite. 2014. “Making Practice Theory Practicable: Towards More Sustainable Forms of Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 14 (1): 25–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540513505607.

- Schatzki, T. 1996. Social Practices – A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shove, E. 2014. “Putting Practice into Policy: Reconfiguring Questions of Consumption and Climate Change.” Contemporary Social Science 9 (4): 415–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2012.692484.

- Shove, E., and G. Walker. 2010. “Governing Transitions in the Sustainability of Everyday Life.” Research Policy 39 (4): 471–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.01.019.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. London: Sage Publications.

- Smith, S. U., S. Hayes, and P. Shea. 2017. “A Critical Review of the Use of Wenger’s Community of Practice (Cop) Theoretical Framework in Online and Blended Learning Research, 2000-2014.” Online Learning 21 (1): 209–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v21i1.963.

- Snelson, C. L. 2016. “Qualitative and Mixed Methods Social Media Research: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 15 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915624574.

- Steinfeld, H., P. Gerber, T. Wassenaar, V. Castel, M. Rosales, and C. de Haan.2006. Livestock’s Long Shadow. Washington: Center for Science in the Public Interest.

- Thomas, T. C., and A. M. Epp. 2019. “The Best Laid Plans: Why New Parents Fail to Habituate Practices.” Journal of Consumer Research 46 (3): 564–589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz003.

- Twine, R. 2014. “Vegan Killjoys at the Table – Contesting Happiness and Negotiating Relationships with Food Practices.” Societies 4: 623–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/soc4040623.

- Twine, R. 2018. “Materially Constituting a Sustainable Food Transition: The Case of Vegan Eating Practice.” Sociology 52 (1): 166–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517726647.

- Underwood, T. 2012. “Topic Modeling Made Just Simple Enough.” The Stone and Shell blog, April 7. Online. Accessed 1 May 2020. http://tedunderwood.wordpress.com/2012/04/07/topic-modeling-made-just-simple-enough

- Vegan Challenge. n.d. “Keitä me olemme.” [ Who We are] Online. Accessed 1 April 2020. https://vegaanihaaste.fi/keita-me-olemme

- Warde, A. 2013. “What Sort of Practice if Eating?” In Sustainable Practices. Social Theory and Climate Change, edited by E. Shove and N. Spurling, 17–30. London/ New York: Routledge.

- Warde, A. 2016. The Practice of Eating. Cambridge: Polity.

- Warde, A., S.-L. Cheng, W. Olsen, and D. Southerton. 2007. “Changes in the Practice of Eating: A Comparative Analysis of Time-Use.” Acta sociologica 50 (4): 363–385. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699307083978.

- Welch, D. 2020. “Consumption and teleoaffective formations: Consumer culture and commercial communications.” Journal of Consumer Culture 20(1): 61–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517729008.

- Wenger, E. 1999. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. 2009. “A Social Theory of Learning.” In Contemporary Theories of Learning, edited by K. Illeris, 209–218. New York: Routledge.

- Wilk, R. 2009. “The Edge of Agency: Routines, Habits and Volition.” In Time, Consumption and Everyday Life. Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, 143–154. Oxford/ New York: Berg.

- Willett, W., J. Rockström, B. Loken, M. Springmann, T. Lang, S.Vermeulen, T. Garnett, and S. Fan.2019. “Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems.” The Lancet 393 (10170): 447–492.

- Wrenn, C. L. 2019. “The Vegan Society and Social Movement Professionalization, 1944–2017.” Food & Foodways 27 (3): 190–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2019.1646484.

- Ylä-Anttila, T., V. Eranti, and A. Kukkonen. 2020. “Topic Modeling for Frame Analysis: A Study of Media Debates on Climate Change in India and the USA.” https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/dgc38

Appendix A.

The topics extracted by MALLET from the corpus, indicating a descriptive label, Dirichlet parameter (DP), and the associated keywords. All translations by the authors.