ABSTRACT

This paper examines contemporary food culture in Ireland through the phenomenon of foodism and the habits and traits expressed through the subculture of foodies. Elements and actors of the Irish food scene are also considered. Qualitative research was applied to investigate the five research objectives posed. This featured six in-depth interviews with “key informants” from Ireland’s tourism sector, educational sector, food sector, and a state food agency, conducted during 2020. The study draws insights from the fields of cultural studies and sociology. Thematic analysis was applied as part of the methodology process, from which five themes developed from the data findings. These are: (1) An evolving Irish food culture, (2) Two perceptions of Irish food, (3) A breakdown of hierarchies, (4) Influencing factors, (5) State body remits. The primary research reveals that industry experts and academics concur that Irish food and culture have “evolved” from a more traditional cuisine and culture and that these are dynamic entities. In addition, it establishes that there is a “hunger for food” amongst a small but growing cohort of Ireland’s population, who wish to gain information via food media and to access food experiences such as culinary courses, gastro tours and food festival events.

Introduction

A broad focus of this paper is the concept of foodism, a narrower one was to investigate the foodism phenomenon occurring within Ireland. Food-centered media, such as television shows and cookbooks, gathered momentum when the nation experienced its boom time “Celtic Tiger” years, from the early 1990s to 2008, and showed no sign of waning during the following years of recession. Deleuze (Citation2014, 143) notes, “the interest in food in Ireland is not new, but it seemingly has reached a level never reached before. One could say that Ireland is turning into a foodie nation.” By applying a cultural studies lens, the researcher examines foodism in Ireland, which encompasses the subculture of foodies. Barker establishes that, “the ‘culture’ in subculture has referred to ‘a whole way of life’ or ‘maps of meaning’ which make the world intelligible to its members” (2012, 429). Ethnologist Lucy Long defines food culture as: “The practices, attitudes, and beliefs as well as the networks and institutions surrounding the production, distribution, and consumption of food” (Lexicon of Food, Citationn.d.; Long, Citation2009, xi). She specifies, “food culture is similar to foodways but tends to be larger and more encompassing of the historical forces shaping eating patterns” (Long Citation2015, 3). Coakley (Citation2012, 323) establishes that, “food culture is an ongoing negotiation of likes and dislikes of traditions and new discoveries; it is a constant process of becoming.” Both Coakley (Citation2012) and Barker (Citation2012) reflect culture as a dynamic concept.

The “food exuberance” phenomenon in Ireland deserves examination as there is a gap in published knowledge since Deleuze’s chapter from 2014 titled; A New Craze for Food: Why is Ireland Turning into a Foodie Nation? To date, academics and writers (Cashman & Mac Con Iomaire Citation2011; Doorley Citation2004, Andrews Citation2009; Goldstein Citation2014; Hickey Citation2018; Mac Con Iomaire Citation2018b; McMahon Citation2020; Sexton Citation1998) questioned: What is Irish food? Yet none has concentrated on the phenomenon of foodism in Ireland, bar Deleuze who queried why an interest in food has risen in the country. It is the intention of this study to build on Deleuze’s insightful research particularly since dramatic changes have occurred in Irish food industry, culture, and gastronomy within the last decade. These are, the establishment of an annual international food centered conference, the origination of “food studies” master’s programs in two Irish Universities, an increase in Michelin stars awarded on the island, a rise in gastro-tourism enthusiasm and food festival attendance, and the dramatic growth in the Irish food export market specifically during 2019. Therefore, 2020 was deemed an appropriate time to conduct follow-up research in this area. In this study six “key informants” share their experiences and offer their perspectives on Ireland’s food culture, foodism, and foodie subculture. Deleuze’s (Citation2014) academic research is then used as a sounding board to compare with interviewee responses. Thematic analysis is applied to identify common themes. Examination of these themes provides valuable insight into the country’s contemporary food culture and interprets perceptions of what the modern-day Irish foodie persona represents. This research makes a valuable contribution to the fields of food studies and cultural studies. In addition, it could be used as a marker to compare subsequent years.

Defining the foodism phenomenon

Historically, a letter written to the British Gazetter in 1727 documents: “A new vice of modern society so contagious that it had recently ‘grown to a greater Excess than ever’” (Mandelkern Citation2013, 1). Mandelkern contends that eighteenth-century foodism “opened up a Pandora’s box of new gastronomic possibilities that threatened to destroy the bonds of common culture” (Ibid). Foodism is defined as: “an enthusiasm for and interest in the preparation and consumption of good food” with a focus on minute details or presentation (“Foodism”, Citation2022). More than 30 years ago, Barr and Levy recognized that “foodism crosses all borders and is understood in all languages” (1984, 6). In the twenty-first century, Mandelkern maintains that “the specter [sic] of foodism still haunts us:”

Foodism altered the cultural meaning of food by separating the act of eating from its innate biological purpose of “filling you up” … aestheticizing food however rendered eating into a solipsistic form of distinction, and assertion of the “I” who had little need for the community.

“The current popularity of cooking and food programs around the world indicates that foodism is a global phenomenon propagated by mass media” (De Solier Citation2005, 465). During this decade, the term “foodism” rarely features in everyday vocabulary instead the on-trend buzzword “foodie-ism” has metamorphosized from the historical label; it is a neologism derived from the original term- foodism. To distinguish between these terms, the researcher will apply the historical one. In addition, it is noted that Deleuze (Citation2014, 150) chose to exclude the popular “foodie-ism” appellation. Alternatively, when she discusses the phenomenon which surrounds the growth of farmers markets and Irish food festivals, the rise of food magazine readership figures in the country plus the surge of cooking shows on Irish television; she establishes: “Foodism in Ireland takes many other [varied] forms.” Hence Deleuze asserts that “today, there is an impression of abundance, hedonism and hyper-consumption that pervades all food related areas: Ireland has gone mad about food.”(2014, 143)

Irish Food Revisited – from famine times to food revival

In order to best establish why the populace’s interest in food has increased, the country’s past relationship with food is considered. People worldwide are aware that scarcity of food can prove detrimental for their health. However, this actuality dwells on collective Irish minds whether consciously or subconsciously, due to the numerous famines their ancestors witnessed throughout the nineteenth century. From mid-to-late 1840s, the Great Famine killed nearly one-eighth of Ireland’s entire population, a result of the complete dependency of a large section of the Irish population on the potato crop. What makes this event even more tragic is the realization that there was abundant food available in the country during this period. Montanari (Citation2006, 25) details the power struggle which occurred between the dominant English landowners and the weaker Irish peasant population; “landowners exercised harsh, restrictive control over Irish food supply, channeling to England the valuable produce (meat, wheat, etc.)” … this meant many of this demographic eventually “were reduced to more or less eating only potatoes” or for any who could afford it the only other option was to emigrate (Ibid). As recent as the 2000s, Irish food critic Doorley (Citation2004, 134) believes that Irish people’s attitude to food still comes with undertones of remorse attached to “historical baggage” left over from the famine, “we have a guilt about eating well because we are the descendants of the people who survived the famine … in this context it is no surprise that our attitude to food is rather short on joy and celebration.” Goldstein further develops this sentiment noting that, “Ireland has suffered twice for its famines and food shortages; first due to very real depravations; and second because these depravations present an obstacle to the exploration of Irish food” (Citation2014, xii).

Ireland is a country with long history of emigration which has been well documented. In the post-famine years, “between 1871 and 1961, the average annual net emigration from Ireland consistently exceeded the natural increase in the Irish population, which shrank from 4.4 million in 1861 to 2.8 million in 1961” (Ruhs and Quinn Citation2009). However, during the 60s due to a “change of direction” of economic policy implemented by the Lemass government, this “produced a relatively quick change of fortune” (Kelleher Citation2013). Subsequent to this, Ireland’s economy began to prosper which helped reverse the flow of emigration so that further into the 1970s, “the Irish economy managed an average GDP growth rate of almost 4.5% a year” (Ibid). During these decades also, a cultural “food” shift occurred within the country due to a variety of factors, i.e., changes in travel and transport technology, an increase in food imports, cooking shows featuring more on national television schedules, and Ireland officially becomes a member of the European Economic Community. Even the distant Irish diaspora would have played a role in influencing change to the Irish palate and “approach” to food, as letters home from abroad would have described new cuisines and tastes they experienced firsthand. Duane (Citation2012) documents how in the 1960s and 70s, subsequent changes which occurred in travel and transport impelled an evolution in tastes; cheaper air freight and worldwide refrigerated transport; the introduction of the “package holiday” and the first “low-cost” airlines.

Suddenly ordinary Irish working people could afford to sail or fly to foreign countries and eat the local foods … when they came back home, they wanted more of what they’d had while they were abroad … which … was anything but Irish traditional food.

People’s elaborate wants and adventurous palates were soon satisfied by local supermarkets who began to stock their shelves with foodstuffs like pasta, rice, olive oil, and exotic spices. During these decades also, the cooking instruction manual came to life when cooks Monica Sheridan and Denise Sweeney presented cooking shows on national television which provided a one-to-one audio-visual experience to an Irish audience while introducing them to new ingredients and cuisines (Sweeney Citation1981; Sheridan, Citation1963). In 1973, another significant factor which affected food selection and production occurred when Ireland became part of the European Economic Community. This event opened cross-border markets, creating a two-way flow for trading which made it easier to import both International and European foods into the country. In addition (Dorgan Citation2006, 4), notes the State’s “confidence and sense of its own status grew.” Unfortunately, these boom years were not to last as the nation experienced recession times again during the 1980s.

Since the late 80s, Irish food writers and restaurant critics John and Sally McKenna have been on a mission to spread the word of Irish artisan food produce, products, and places. They published The Irish Food Guide in 1989 to much acclaim. In subsequent years, they released their annual McKenna’s Food Guide in conjunction with Bridgestone International (until 2013) and have published this independently in recent times. In an interview from 1995, the critics list that “the most notable change they’ve found on the restaurant front is the increasing number of young and innovative chefs” (McKenna Citation1995). Interestingly, they also add: “in terms of restaurants, there are still a number of black spots throughout the country” but a turnaround should eventually occur if highly trained Irish chefs return from abroad to open their own premises (Ibid).

Celtic tiger consumption

American psychologist A.H. Maslow’s “needs” theory details physiological needs at the base of a pyramid followed by social, esteem and self-actualization (Linehan Citation2008, 46). When Ireland experienced its most recent economic boom from the early 1990s to 2008 (known as “the Celtic Tiger” years), an increase in wealth presented opportunities to a portion of the population to focus on satisfying other needs such as social and ego (not simply physiological ones), thus enabling them to progress further up Maslow’s hierarchical pyramid. Dorgan (Citation2006) accredits the success of these decades to pragmatic investment by the state into the areas of education, foreign investment, taxation and fiscal policies, and the intangible asset of Irish creativity: “These years saw economic growth, rising living standards and employment soar from 1.1 million to 1.9 million” (Ibid). Mac Con Iomaire documents a growth of haute [high] cuisine in Dublin restaurants and an increase in Michelin star rewards during the mid-1990s (Citation2011, 541). Referring to the change in attitudes toward food during the boom years, Boucher-Hayes and Campbell observe:

Food and eating were one of the ways in which we were desperate to redefine ourselves. The spud went out the window. In came prosciutto and sushi…our connection to growing food, and our knowledge of food had completely broken down.

Similarly, economist David McWilliams progresses with the concept that the Irish sought to redefine themselves and further refine their epicurean tastes. He labels a cohort of the population, “Hibernian Cosmopolitans” (HiCos). “For HiCos, food marks you out. It distinguishes the truly educated from the merely rich” (McWilliams Citation2006, 264). These “tongue in cheek” cultural and societal observations by McWilliams are comparable to how (Barr and Levy Citation1984) satirically observed British and American society during the 1980s. Deleuze notes that during this economic upturn, “Ireland entered the age of hyperconsumption”, hence she asserts: “this society of ‘hyperchoice’ is the perfect fertile ground for the emergence of foodies” (Citation2014, 144).

Celtic Food Revival and redefining the Irish Chef

Irish historian and chef Mac Con Iomaire (Citation2018a, 59) believes: “The rebirth of Irish gastronomy coincided with the Celtic Tiger years (1994–2007)” and the recession which followed forced Irish chefs to become frugal with their cuts of meat and forced them to experiment with “non-gourmet ingredients” (Ibid). The “Celtic” gastro revival progressed further due to Irish chefs winning international awards, such as Mark Moriarty, who won the San Pellegrino Young Chef of the Year in 2015 (Mac Con Iomaire Citation2018a, 70). Chef Mark Moriarty describes his cooking style as, “classically based, simple and confident, presenting Irish food in a new way” (Moriarty Citation2018, 34). Furthermore, Mac Con Iomaire notes, the Nordic Food culture movement had a big influence on Ireland’s contemporary food scene which helped Irish chefs re-visualize their own homegrown food culture and traditions (Ibid). Amilien and Notaker (Citation2018, 24) define Nordic cuisine as: “A respect for nature, slow cooking, raw and simple food” which reflects an innovative use of fermentation. Ironically, a visit to Ballymaloe House with Euro-toques and tasting the simple wholesome local food of Myrtle Allen, was one of the inspirations that led Claus Meyer to start the Nordic Food movement (Connolly Citation2023 forthcoming).

Another development within the Irish food scene relates to chef activism. While Irish food revolutionary, Myrtle Allen (of Ballymaloe House) and her successor Darina Allen have both carried the “activist gauntlet” for many years. Other chefs such as Richard Corrigan and Food on The Edge founder, JP McMahon have grasped it, so too have chefs Jess Murphy and Domini Kemp, all of whom are vocal on food matters, have written for the Irish Times and contribute as speakers at food focused festivals. Activism is also evident in the annual Food on the Edge (FOTE) conference (first held in 2015) which focuses on global food topics not just topics specific to Ireland. What began as a collaborative event for chefs and restaurateurs now attracts a wider audience that includes foodies, food writers, bloggers, journalists, and tourism specialists. These collective culinary voices, the Food on the Edge symposium, the impact of internationally renowned chefs via the Chef’s Table television series such as Albert Adria, Massimo Bottura, René Redzepi and Claus Meyer (two chefs at the fore of the New Nordic Food movement), amongst other harmonizing factors have influenced and inspired a new generation of Irish chefs, who in turn, are active in redefining the traditional role of the chef.

What is Irish food Today?

Food choice in Ireland is varied and vast compared to what was on offer to previous generations. From the mid-nineties in the capital city Dublin, an unconventional type of restaurant was introduced in the guise of a more “communal” dining experience inspired by Japanese eateries, these were the Yamamori and Wagamama restaurant chains. Both featured dining rooms where restaurant goers were expected to sit in proximity at large communal bench tables, while menus were designed to act as diner’s placemats. Sage (Citation2010, 95) suggests the Irish were introduced “to an era of dashboard dining from the late 1990s” onwards because of the addition of 24-hr convenience stores, takeaway food courts at petrol stations and greater access to disposable income to spend on eating outside the home (Citation2010, 93). A symbol of this, he points out, was the popularity surrounding the “Jumbo Breakfast Roll.” The food court “Chicken Fillet Roll” and the “Jambon” followed as part of this convenience food trend and gained similar popularity.

The researcher reflects that “during the noughties, an influx of immigrants added to Ireland’s population which in turn saw Polish supermarkets, Nigerian Bars, and Korean, Filipino, Brazilian, and Argentinian restaurants add a diverse food landscape to the capital city” (Reil Citation2013, 2). Within this decade also, the Starbucks corporation opened its American-culture coffee chains on the island. This “to-go-cup” trend and café-focused lifestyle heavily influenced the younger Irish demographic, who were further exposed to it via the popular U.S. television series Friends. Nowadays, traditional dishes like Irish stew, coddle, colcannon, and boxty are presented with a “European twist” on many restaurant menus and cooked less frequently in a home setting, while there is a possibility some of the younger generation may have never tasted them (Ibid), a factor which could diminish connections with past food traditions. As Fischler states, “if one does not know what one is eating, one is liable to lose the awareness or certainty of what one is oneself” (Citation1988, 290). However, passed proprietor of Ballymaloe House, Myrtle Allen maintained:

When we talk about an Irish identity in food, we have such a thing, but we must remember that we belong to a geographical and culinary group with Wales, England and Scotland as all countries share their traditions with their next door neighbour.

Food historian Sexton (Citation1998, 7) recognizes that “many of our foods are simple and peasant in origin. Much the legacy of poverty and harsh economic circumstances.” While Hickey (Citation2018, 14) contends: “A combination of political and historical forces that find no parallel elsewhere in Europe created conditions in Ireland inimical to the proper enjoyment of Irish food and the development of an intricate native cuisine.” In a similar vein, Mac Con Iomaire (Citation2018a, 6) holds, “[what] could also account for the difficulty of creating a ‘national’ cuisine” was how, “during the Celtic revival in the late 19th century, nobody thought of food culture as an element in nation building” (Ibid). In addition, Goldstein (Citation2014, xi) suggests that over the years “too many self-avowed connoisseurs were convinced that Irish food began and ended with cabbage and potatoes- or the lack thereof.” Within the last decade, visible additions to the island’s culinary offerings particularly on many high-end restaurant menus are a variety of the three F’s; these are foraged, fished, and fermented ingredients. Ingredients that harp back to our hunter gatherer ancestors long before the introduction of farming to Ireland. McMahon (Citation2020, 16) suggests that “we can see how so much of what people now call ‘New Irish Cuisine’ took place during the formative years of the habitation of this island.”

A golden year for Irish gastronomy

As mentioned in the introduction, 2019 proved to be a golden year for Irish gastronomy which contrasts greatly with the time of recession discussed by Deleuze (Citation2014). This “golden year” reflects a culmination of growth, particularly in relation to Irish food exports, gastro-tourism, food festivals, and Michelin stars awarded on the island. The Michelin Guide Great Britain & Ireland Citation2020 listed a total of 18 Michelin one-starred restaurants, 3 Michelin two-starred restaurants and 21 Bib Gourmand restaurants for the Republic of Ireland (Irish Times Citation2019). The Irish food board, Bord Bia, in their Industry and Performance Prospects Report 2019–2020 states: “2019 was a record-breaking year for Ireland’s food, drink and horticulture industry as exports reached €13 billion, capping a decade of consistent growth of 67% since 2010” (Bord Bia, Bord Citation2020a, 8). A triad of Irish Tourism Board agencies, Fáilte Ireland, Tourism Ireland, and Tourism Northern Ireland, launched the Taste the Island campaign in Autumn of that year, which gave country-wide gastro-tourism offerings a marketing boost and connected micro-food businesses with prominent tourism networks. Plus, a bonus from this was the emergence of spin-off regional food-centered collectives that formed countrywide, e.g., Taste Waterford, Taste of Limerick, and Taste Cork.

In 2019, it became evident that the Irish embraced the concepts of organic, shopping locally, and supporting producers more. This is backed up by another relevant report carried out by Bord Bia called the Evening Meal Recruitment Survey 2020 which posed the question: “What Ireland Ate Last Night?” to the average Irish adult consumer. The overall survey examined the eating habits and opinions of a percentage of the Irish population throughout the month of October 2019. Specific findings were compared with previous findings from a similar survey the organization conducted, in 2011. Survey findings showed that the average Irish consumer in 2019 placed more significance on food provenance. Data revealed that 6% more consumers choose Irish produce when available and there was a 10% rise in those that believe it is best to pay more for Irish products (Bord Citation2020b, 14). Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Irish food festivals thrived with large attendance numbers for the Galway Oyster and Seafood Festival, West Waterford Food Festival, A Taste of West Cork Festival, and Taste of Dublin. The Taste of Dublin event “[transforms the Iveagh Gardens] into a foodie haven” (Taste Food Festivals, 2019). Attendance figures for the four-day gathering in June 2019 were 32,000 (Falvey Citation2019).

Furthermore, a premier for Ireland and a prominent event for an Irish educational institution, 2019 was the year that saw the first cohort of students graduate with a Master of Arts in “Gastronomy and Food Studies”. This post graduate program offered by Technological University Dublin covers a diverse menu of subjects such as, Irish food history, politics of the global food system, wine and beverage culture, food tourism, and food writing. That same year, University College Cork announced the inclusion of a “Post Graduate Diploma in Irish Food Culture” to their prospectus. On their website, the institute states: “Interest in food and culinary matters is at an all-time high as Ireland develops a more considered relationship with Irish food culture” (University College Cork Citation2019). These combined occurrences further demonstrate a rise in reverence to food in Ireland and also indicates progression of the phenomenon as documented by Deleuze (Citation2014).

Foodies defined

Foodie culture has previously been studied in the United States by sociologists, Johnston and Baumann (Citation2010), cultural theorist Collins (Citation2015) and in Australia by material culture theorist, de Solier (Citation2013). In Great Britain, the subculture was explored and satirized by authors Barr and Levy (Citation1984). Furthermore, Marjorie Deleuze examined whether Ireland has turned into a foodie nation: “The Republic is definitely writing a new page in its culinary history and this new phenomenon cannot go unnoticed” (Citation2014, 143). It is generally agreed that restaurant reviewer Gael Greene first referenced the word “foodie” in a 1980s article for the New York magazine (Deleuze Citation2014; Levy Citation2007; Livingstone Citation2019; Poole Citation2012). However, a more popular belief is that the term was coined in 1982 in the British-style magazine Harpers & Queen, which describes a foodie as, “a ‘cuisine poseur’ who used cultivated culinary consumption as a mode of social distinction” (Woods et al. Citation1982). Authors of The Official Foodie Handbook depict foodies as, “children of the consumer boom [who] consider food to be an art [form]” (Barr and Levy Citation1984, 6). This slang term frequently used in popular culture today defines: “A person keenly interested in food, especially in eating or cooking” (“Foodie”, Citation2022). Furthermore, Barr and Levy (Citation1984, 7) specify that “the gourmet” was “typically a rich male amateur to whom food was a passion [and] foodies are typically an aspiring professional couple to whom food is fashion”. Thus, Livingstone (Citation2019) argues “If Barr and Levy were right in asserting that foodie culture is a late-twentieth-century trend in passion-driven behaviors, then we are now living through the full commercialization of their theory”. Author Sudi Pigott, a self-declared foodie, outlines that her tribes’ food mantras are: “provenance, seasonality, artisanal, and single-estate and we consider such impeccable credentials a necessity not a luxury” (Pigott Citation2006, 19). During the 2010s, Johnston and Baumann (Citation2010, 67) view foodies as learned individuals who, “see themselves as well positioned to talk about and distinguish worthy food from unworthy food”. De Solier adds: “The category of the foodie encompasses both men and women” (Citation2013, 12). She further proposes that foodie identity, “is a product of globalization and transnational flows of food, tastes, media, capital, and people” (Citation2013, 13).

Are foodies a subculture more than mainstream culture?

Theorists such as Parasecoli (Citation2013) and Anderson (Citation2014) hold contradicting views on whether foodies are an established societal subgroup. Barker (Citation2012, 429) who has studied subcultural groupings explains, “the ‘culture’ in subculture has referred to a ‘whole way of life’ or ‘maps of meaning’ which make the world intelligible to its members. The ‘sub’ has connoted notions of distinctiveness and difference from the dominant or mainstream society”. He further points out: “the notion of an authentic subculture depends on its binary opposite e.g., a mass-produced mainstream [popular culture]” (Ibid). Likewise, Parasecoli (Citation2013, 274) concurs that, “specific subgroups in a society may develop their own forms of expression through which they may directly or indirectly criticize and oppose the mainstream [or popular culture]”. He further argues: “foodies are one of the many ‘well established subcultures’, sprouted around food issues”; a subgroup that “deserves greater attention … in terms of lived experiences and the performances of newly built and shifting individual and collective identities” (Ibid). However, Anderson opposes this view arguing that, “gourmets and foodies do not form true subcultures but are still defined by their tastes … much of it is driven by the need of individuals to communicate something special, distinctive, and personal about themselves” (Citation2014, 178). Nonetheless, in line with Parasecoli’s insights the researcher establishes that foodies are indeed a subculture.

Taste, distinction, cultural capital, and subcultural capital

Mandelkern (Citation2013, 1) observes, “the anxieties associated with eighteenth-century foodism were very similar to those voiced today … and then just as now, taste and snobbery went hand in hand.” However, Johnston and Baumann argue: “foodie culture is not a simple story of snobbery or cultural liberation but is fundamentally constituted by the tension between a pull of democratic inclusion and the desire to erect boundaries of exclusivity, distinction and social status” (Citation2010, 106). While distinction relates to how a material object is used or absorbed, according to de Solier: “it is the way foodies consume haute cuisine and the way they shop for quality food that makes them a foodie” (2013, 113). Montanari adds that aside from taste being the “sensorial assessment of what is good or bad … it can also mean knowledge” (Citation2006, 63). Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital relates to:

Knowledge that is accumulated through upbringing and education which confers social status. It is the linchpin of a system of distinction in which cultural hierarchies correspond to social ones and people’s tastes are first and foremost a marker of class.

Therefore, “distinctions are never simply statements of equal difference. Rather, they entail claims to authority, authenticity, and the presumed inferiority of others” (Bourdieu Citation1984 in Barker Citation2012, 451). Cultural capital differs from economic capital (wealth) and social capital (whom you know). Bourdieu (Citation1984) indicates that, cultural capital can be held in as high esteem as that of other types of economic capital, for example, owning property or having wealth. Drawing from Bourdieu’s observations, Thornton (Citation2005) developed her theory of “subcultural capital” while studying a subgroup formed within the British Club Culture scene. She posits that, “just as cultural capital is personified in “good” manners and urbane conversation, so subcultural capital is embedded in the form of being ‘in the know” (Thornton Citation2005, 186). A critical difference she points out between subcultural capital and cultural capital (as theorized by Bourdieu) is how, “the media are a primary factor governing the circulation of the former” (Ibid). Hence, Thornton argues, “the difference between being in or out of fashion, high or low culture in subcultural capital correlates in complex ways with degrees of media coverage, creation and exposure” (Citation2005, 187). Furthermore, she concludes that cultural capital is more class-bound than subcultural capital.

Anderson points out that, “foods as class markers are so important that elites have often resorted to ‘sumptuary laws’ to protect themselves from status emulation” (Citation2014, 136). However, Johnston and Baumann (Citation2010) maintain that class may no longer feature as part of the foodie persona. This is difficult to concur with when considering studies carried out by Bourdieu in Distinctions (Citation1984). Here, he examines the tastes and preferences formed by the different class structures in France. Bourdieu’s analysis (Citation1984, 5) was based on a survey questionnaire, carried out in 1963 and repeated in 1967–68, on a sample of 1,217 people. He establishes that “food tastes were far from individual but have their basis in the social relationships between different groups and in particular, social classes” (Bourdieu in Ashley et al. Citation2004, 64). In addition, de Solier’s (Citation2013) findings directly contradict those of Johnston and Baumann (Citation2010). She adds that the majority of her research participants (self-professed foodies) “earned incomes above the national average wage with a substantial majority earning double”. Mennell makes the point that throughout history, “social distinction was expressed not simply through the display of ‘good’ manners but also through the consumption of ‘good’ food” (1996, 56). Montanari (Citation2006), Mennell (Citation1996) reinforces this point, by discussing how spices were a popular choice on the tables of the ruling classes in the Middle Ages but changed during the seventeenth century when the price of spices declined, making them more accessible on the mass market, therefore losing its badge of social distinction. Subsequently, “the elites sought new upscale bases of distinction: butter, pastry, or even fresh garden vegetables [and fruit]” (2006, 73). Hence, he establishes: “The anti-low-cost budgetary trend would thus seem to be an important motor in the process of the formulation of taste in the upper classes” (Ibid) (Italics in text).

In a present-day setting (Collins Citation2015, 271), whose paper highlights the rise of the foodie suggests: “food is still a divided, classist arena with a high dose of aspiration (vs. inspiration as touted by television programmes and hosts) with political, economic, and cultural causes and effects.” However, Deleuze contradicts this arguing that “anyone can be a foodie today, it is no longer exclusively the preserve of the well-off” (2014, 144). While later in her chapter, she surmises: “not everyone [In Ireland] can experience dining-out on a regular basis, not everyone can buy an entry to the “Taste of Dublin” [food festival] … and the farmer’ markets are not really frequented by low-income people (2014, 155). Furthermore, Collins adds that “it is widely known that foodies are a group with particular tastes, interests and a body of knowledge that separates them from those without” (2015, 271). A “common denominator” is an appreciation of food:

A “foodie purist” has a high degree of earnest interest in learning about and, as a result, a knowledge about food that includes, for instance, its historical origins, social history, flavor profiles and ideal wine pairing.

A key trait which continually surfaces within the foodie sub-group is their “quest for knowledge” surrounding food related matters. This is a feature the tribe utilizes as a form of distinction, in place of wealth or social standing and one which demonstrates Thornton’s notion of subcultural capital; the form of “being in the know.”

Research approach

The literature review interprets the foodism phenomenon posed by research objective one: Explain the foodism phenomenon, and it partially answers objectives three and four below. The primary research leads toward answers for the remaining research objectives:

Explain the foodism phenomenon.

Identify what is Ireland’s present discourse around food.

Determine why Irish people’s interest in food has risen.

Establish if foodies are a subculture or a mainstream culture.

Investigate how the main food actors contribute to contemporary food culture.

In relation to this study, a qualitative approach was applied. “Qualitative research … is mainly concerned with the properties, the state and the character (i.e., the nature, of phenomena)” (Labuschagne Citation2003, 100). This method provides a subjective style of research that “works with small samples” … the logic behind this is usually to give a more in-depth understanding” (Hesse-Biber and Leavy Citation2011, 45). Researchers are trying to develop a means to explain the bigger picture (Creswell Citation2009). The primary research was conducted in the form of semi-structured interviews, with an initial plan to further conduct a focus group based around “self-professed” foodies. However, the organization of participants for a focus group proved impossible due to COVID-19 health restrictions enforced during March 2020 and this was unpredictable time too when it came to the interviewing process. In total, six lengthy and in-depth interviews were carried out with individuals involved in the Irish food scene. Interviews took place from March 10 to April 27, 2020, with experts from the gastro-tourism industry, the hospitality industry, food consultancy, education, and a state food agency. Interviewees were purposively selected because they offered a unique perspective on the research topic or held positions which offered access to sought-after information such as state policy or industry insight. These types of interviewees are what Denscombe (Citation2003,189) considers “key informants,” from whom the researcher tries to tap their “learned wisdom.” Interviewee K is a gastro-tour operator and food blogger, and “M” is an academic and a lecturer in Culinary Arts. Interviewee A is a food and drink consultant and a Euro-toques Ireland representative. Participant “J” is a food writer, and a restaurant critic and “P” is a renowned chef and restaurant owner. Finally, Interviewee G works as a consumer insight specialist at Bord Bia. All interviewees where asked a sequence of 12 questions as follows:

Questions 1 to 4 were general introduction-styled questions which varied for each interviewee and related to the specific individual’s experience or the organization they were associated with.

Questions 5 to 12 were common questions asked of all of the interviewees which were directly linked to the specific research objectives (as outlined earlier).

Analytic coding

These recorded interviews were then transcribed, and code named in preparation for analysis. As a way to decompose and segment the data that researcher created a code system of “predetermined and emerging codes” as recommended by Creswell (Citation2009, 187). “Predetermined codes” are those that may have already been raised in the literature (Ibid). The researcher also deduced that by applying color coding, this would help to categorize the greater body of interview transcripts. Color-coded research objectives were matched with the prevalent and specific interview questions. Predetermined codes (PD codes) which were distinguished were numerically named 1 to 9 and then aligned with the significant interviewee answers. From this study, some predetermined codes that arose were – what is Irish food? Cultural capital, and chef activism. “Emerging codes” are any new or unforeseen topics that surface from the interview material, e.g., influence of education, pride and confidence, and two perceptions of Irish food. Themes “should display multiple perspectives from individuals and be supported by diverse quotations and specific evidence” within interviews (Creswell Citation2009, 189).

Thematic analysis

As a result of further COVID-19 restrictions such as the introduction of public health lockdowns, a focus group could not be formed as part of this research study, so it was deemed important to interpret the dataset for further “maps of meaning”. Psychologists Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) are strong advocates of thematic analysis as a process to administer for data analysis. This method is seen by some theorists as: “a key phase of data analysis within interpretative qualitative methodology” (Bird 2005 in, Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 17). “Thematic analysis involves the searching across a data set – be that a number of interviews or focus groups or a range of texts – to find repeated patterns of meaning” (2006, 15). This means that abundant data is examined “to extract core themes that could be distinguished both between and within transcripts” (Bryman Citation2012, 13). Preferably, “the analytic process involves a progression from description … to interpretation … often in relation to previous literature” (Ibid). Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) refer to this approach as the “latent approach” which “would seek to identify the features [the data] gave it [sic] that particular form and meaning” (Ibid). Hence, they note that in latent thematic analysis “the development of the themes themselves involves interpretative work, and the analysis that is produced is not just description but is already theorised” (Ibid). Their “six-step process” is not a linear one but one that is ongoing. The researcher needs to constantly move forwards and back across the whole range of data that is gathered- “the coded extracts of data that you are analysing, and the analysis of the data that you are producing” (2006, 15). This thematic analysis six-phase process entails: 1. familiarization with the data, 2. coding, 3. searching for themes, 4. reviewing themes, 5. defining and naming themes – which “requires the researcher to conduct and write a detailed analysis of each theme, such as ‘what story does this theme tell?’ and ‘how does this theme fit into the overall story about the data?’” (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 35). The process then concludes with phase 6: “writing up” which “involves weaving together the analytic narrative and (vivid) data extracts to tell the reader a coherent and persuasive story about the data and contextualising it in relation to existing literature” (Ibid).

Results and findings

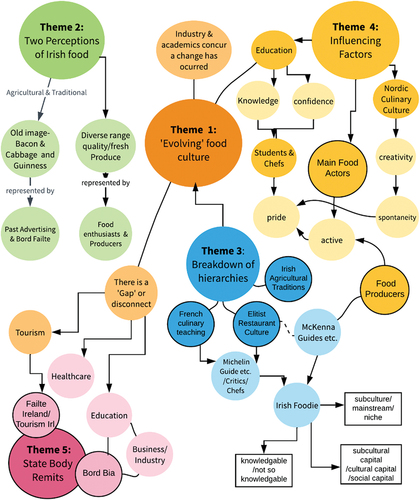

Adhering to phase one of the Thematic Analysis Process, the researcher established an in-depth “familiarization with the data,” each interview was listened to numerous times, transcribed, annotation was applied by highlighting significant sections or quotes, and line numbering was used to easily trace exact comments or topics discussed by interviewees. In the second phase (or step) of thematic analysis, the researcher searched for codes across all the data which included “predetermined” and “emerging” sets of codes as previously outlined. Following steps three and four of Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis process, the researcher devised an initial concept map was called Thematic Map 1 which displayed six potential themes. However, these were in no way finished concepts and required the researcher to further analyze to give a clearer picture of the data. An attempt was made to establish more focused and definite themes. When further broken down, these concepts are then developed into a more advanced concept map, i.e., Thematic Map 2, see . Finally, all five themes are discussed later in this paper and backed up with corresponding interview excerpts while compared and contrasted with the literature (which concludes phases 5 and 6 of the thematic analysis phases).

Figure 1. Thematic map 2 shows map depicting the five final main themes.

Predetermined codes

An example of a “Predetermined Code” is displayed in . This relates to the sub-research objective: identify what is Ireland’s present discourse around food. This objective’s corresponding interview questions were Q.5. What do you think best describes Irish food? (PD Code 1). Q.6. How do you think Ireland is viewed gastronomically? (PD Code 2).

Table 1. Predetermined code 1 with corresponding interview data extracts.

Common codes that emerged from interviewee’s responses for “Irish food” were:

Raw Ingredients (all 6 responded)

Evolving (4 responses)

Local (3 responses)

High/Good Quality (2 responses)

More descriptions were fantastic, spontaneity, inspirational, healthy, tasty, fresh, traditional, simple, accessible, diverse, sustainable, and humble cooking. Finally, produce or products mentioned by respondents relating to Irish food were – Dairy (milk/butter/cheese), Meat (beef/lamb/bacon), Seafood (salmon/oysters/seaweed), and Vegetables (potatoes/herbs/cabbage).

Interviewee’s perceptions of foodism

Sub-research objective 2: To determine why have Irish people’s interest in food risen. This objective’s corresponding interview questions were Q.7. From your experience – can you describe what foodism or foodie-ism is? (PD Code 3). Q.8. Do you think Irish people display an exuberance for food? (PD Code 4). Interviewee’s attitudes in relation to the word foodism were as follows:

People with a ‘high interest in food … or people who are looking for good food … you can call it gastronomic and bon vivant … you can call it foodie-ism it’s all the same. (Interview K, line 147–151)

It is a sort of word or a movement that has appeared really in the last 20 years … and part of it is linked with the idea of the Celtic Tiger in Ireland. (Interview M, line 263–265)

It’s a trend … it’s ‘foodie. It’s something that’s current, it’s trendy, it’s popular to say that you’re a foodie – to go out and eat and to socialize. (Interview A, line 134–136)

It’s not a snob thing in Ireland, it just shows that you’ve got a bit of savvy really. (Interview J, line 373–374)

What it means is that I have an interest in food which is a really good thing. (Interview P, line 107–108)

I think the way you describe it is good [an exuberance for food] but ways of eating … [might be one way to describe it] … ways of eating today. (Interview G, line 153–154)

On further analysis of the data, the researcher notes that the majority of the interviewees seemed initially puzzled by the term “foodism” this may be down to the prevalent use of the term “foodie-ism” within popular culture in modern society. Participant J even commented that he was “intrigued” by the use of the term, but during the interview, it was apparent that he had given the term careful consideration and applied the concept in relation to Ireland also (line 373–374). And respondent G, at first relied on the interviewer’s definition of the word but then suggested it could refer to, “ways of eating today.” It was the consensus among respondents that foodie-ism (not foodism) is broadly the more preferred term that is used nowadays. Generally, the Irish have an exuberance for food which is prominent in a small portion of the population. This foodie cohort may increase over the coming years due to a rise of “gourmet” products in supermarkets which makes them more accessible to the “mainstream” population. Food as a topic is viewed as a valuable way to connect with other people and cultures as it is a common dominator between them.

Interviewee’s perceptions of the modern Irish foodie

Research objective 3: To establish if foodies are a subculture or a mainstream culture? Corresponding questions are, Q 9. What do you consider a foodie to be? (PD Code 5). Q 9.1. Do you see foodies as a subculture or more mainstream? (PD Code 6) and Q 10. Would you call yourself, a foodie? (PD Code 7). From the primary research, the researcher ascertains that many chefs and workers connected to the food industry do not consider themselves to be foodies, even though they may possess foodie traits, see . They believe that “knowledge” and keeping “well informed and interested” is what separates them from the average foodie. Negative comments related by a few interviewees in relation to the word contradict what Deleuze (Citation2014, 143) suggests how “nowadays the term has progressively lost its negative meaning.” Interviewee K (line 147) claims: “Foodie is a word that everyone hates!” and “it has a bad connotation. I think especially with professionals from the food industry. They don’t really like people who call themselves foodies” (line 151–154). Respondent M concurs that it is a derogatory term; “[one] someone should use to describe someone else as opposed to what someone should self-describe themselves” (line 368–370). Participant A believes that “it’s not someone that’s really passionate about authentic or real, it’s more something that’s popular” (line 136–138). “A” points out that, “a prime example” [of foodies] are the Press Up group’s diners and club members in Ireland; whom he insists do not know about food: “Because they all just dine in the Press Up group, and they think that’s amazing” (line 199). Interviewee A states: “I just have the knowledge to know that Press Up is all marketing and it’s not right compared to Chapter One, and I know it’s more valuable” (line 189–190). The researcher notes that a distinct divide appears between the “knowledgeable” or the “well informed” foodie tribe and the “not so knowledgeable” foodie tribe. Similarities of this “knowledge” factor ties in with the literature with what (McWilliams Citation2006) found during the noughties decade, in the form of his Hibernian Cosmopolitan tribe (HiCo’s). He insists that it was education that distinguished this tribe not wealth, who used food knowledge as the signifier which “distinguishes the truly educated from the merely rich” (2006, 264). Today the keen Irish foodie values knowledge and uses it, not just wealth or social status, as a way to establish distinction. Interviewee J adds: “It’s not a snob thing in Ireland, it just shows that you’ve got a bit of savvy really” (line 373–374).

In the literature, Poole (Citation2012) points out that the “foodie has now pretty much everywhere replaced “gourmet.” Interviewee G from Bord Bia (a state food agency) holds that there are lots of different types of foodies present in Irish society. She mainly refers to foodie consumers, which as established earlier, are “active” consumers of gourmet products and media users (see De Solier Citation2013). “G” relays that today’s foodies should be allocated into niches such as, the “gourmet” foodie, the “sporty” foodie, the “health-food foodie” etc. Her concept ties in with Anderson’s (Citation2014) ideas on multi-foodie-personas and connects too with Deleuze (Citation2014, 150) findings on foodism during 2012: “Foodism in Ireland takes many other forms.” Similarly, respondent G adds that sustainability, “clean” food, and environment are an important factor in many Irish people’s lives now. Deleuze (Citation2014, 151) also reflects the outlook about Irish citizens having, “a raised awareness of environmental issues.”

Interviewee K (food tour operator and blogger) was the most prolific when describing the traits and habits of the Irish foodie. The following data extracts from the primary research capture her perceptions:

Well to be honest, your average … foodie in Ireland would be more social economic traits … you know it’s not going to be people living on the minimum wage. (Interview K, line 190–192)

It’s kind of a privileged thing being a foodie. It’s not like food is cheap [in Ireland]. (Interview K, line 191–193)

So, it is people usually female … I can tell from by [my blog] readership … female, living in the city, lots of them. (Interview K, line 193–195)

That fact that respondent K mentions, foodies are usually female links back to the literature where (Livingstone Citation2019) who also perceived the foodie to be female claims that “the foodie is ubiquitous, she has never been harder to define”. This is disputed by (Barr and Levy Citation1984) and (De Solier Citation2013) who believe the contemporary foodie is represented by both the male and female gender. “K” also points out that food in Ireland is relatively expensive and would be inaccessible to someone living on the minimum wage, especially gourmet food. This is further backed up in the literature by Deleuze when she notes “the farmers’ markets are not usually frequented by a low-income clientele” or not everyone can afford to dine out on a frequent basis (2014, 155). Further descriptions detailing the social status and demographics of the Irish Foodie as viewed by participant K are displayed in :

Also displayed in are descriptions of foodie traits as listed and mentioned by all participants during the interview process. Noticeable traits that stand out and are somewhat contradictory are, “there are a percentage of them who never cook” and “a percentage who are not knowledgeable about food”. Two of the interviewees K and A (as a forementioned) express the notion that there is a percentage of the Irish foodie tribe who label themselves as foodies but as K relates: “They’re not so much a foodie because they don’t know so much about food” (line 162).

In relation to whether the foodie cohort should be considered a sub-culture or a mainstream culture, findings from the interviews displayed in showed that half of the interviewees (K, A, and J) considered foodies a mainstream culture. This may be down to a wider proliferation of “gourmet” foodstuffs and the notion that it is a trendy or popular stance or outlook to adopt now in the public domain. A fourth interviewee G relates that she didn’t necessarily think foodies were a mainstream culture but that it may become a factor soon, due to the trend of “gourmet” foods becoming popular and more widespread and to the fact that it is also spread quickly now by “word of mouth.” The remaining interviewees P and M maintain that foodies are a subculture. However, participant P pointed out it is one that is growing all the time. In addition, while respondent M thought that it represented quite a large sub-culture, he believes “there is still a lot of people in the general public who consider food just to be something that they eat as fuel” (M, line 399–400).

Table 2. Interviewee’s views on foodies as a subculture or mainstream culture.

Analysis and discussion of the five main themes

To recapitulate on the thematic analysis approach: “A theme is a coherent and meaningful pattern in the data relevant to the research question” (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 15). An essential requirement of this process is to connect themes back to the literature. The Five Themes that surfaced from the interview data are as follows: (1) An evolving food culture (2) Two perceptions of Irish food (3) A breakdown of hierarchies (4) Influencing factors, and (5) State Body remits.

Theme 1: an evolving Irish food culture

It was established that food culture is a dynamic process (see Coakley Citation2012). From the primary research, it can be ascertained that food industry experts and academics concur that Irish food culture has evolved and is evolving from the more traditional Irish cuisine and culture. Half of the participants used the term “evolving” in their responses; Another interviewee P (who is a chef) mentioned that he cooks Irish food with a “European twist;” “I would do bacon and cabbage risotto, I would take certain ways of cooking, say from Italy or France and put Irish ingredients in there, use the methods but with our ingredients” (line 75–79). In the literature, a similar hybrid cuisine was observed by Reil (Citation2013) (see ‘What is Irish Food today?). Hence, the researcher suggests this can be noted as a cuisine that is changing from a more traditional cuisine. Therefore, this means four of the six interviewees in total, made references to contemporary Irish food as “evolving” in some form, e.g., K (line 101) specifically notes: “Now Irish food is evolving” and how, “it’s improved a lot. People are lucky now even people that are moving here … Oh my god! The food! Fifteen years ago, it was not as good” (line 113–115). In a similar vein, it was discussed that simple ingredients like bread and butter are being revisualized by chefs in Irish restaurants:

That way in which bread and butter has been transformed by the best Irish restaurants- they turn it into an event. It’s a significant aspect of that creativity, to look again at something that you take for granted. It’s very encouraging!

A broader discourse has begun to develop around food in Ireland which no longer just focuses on the famine era or the Celtic Tiger Years. As aforementioned, one reason for this is due to a greater interest in food being studied as a third level academic subject. An Interviewee noted that, “what we have now is people … researching food from so many different angles … using food as a lens [to examine] as opposed to war, or class or using gender, or anything else!” (M, line 129–132). Another observes how in Ireland there is a: “Hunger for food” (P, line 201–216) within a minority group albeit a growing cohort of the population, in relation to access to information through media such as newspapers and cookery books. While interviewees J and P both discuss the rise in interest relating to “food experiences” like culinary courses and festival events. This plus the increase in attendance points to a wider curiosity which has emerged amongst the general public.

Theme 2: two perceptions of Irish food

It was concluded from the primary research that there are two perceptions of Irish food; one is of fresh, good quality, with a diverse range of produce and products; the other is the old image of bacon and cabbage and Guinness which was presented via advertising and tourist boards down through the years (A, line 109–115). Respondent K concurs: “Your average tourist the one that does not partake in food tours, they think that Irish food is going to a pub and getting fish and chips” (line 127). Hence, she adds that there is a divide “between people interested in food, that will search and find quality food and your average tourist that just want “food” (line 143–145). Interviewees (K, M, A, and J) deduced that a gap in the dissemination of the tourism message exists. Furthermore, “A” noted that this “gap” does not only exist in the tourism sector but it has also surfaced in the public, education, and healthcare sectors. He maintains: “Tourism is only an aspect but it’s only a small part of ‘food’. You have public, like schools, education, and healthcare, which are not supporting food, and the social section as well” (A, line 330–334). Another interviewee J pointed out that this stems back to a lack of interest in “food” in the government. Government concentration in relation to food is mainly an agricultural one or as an export industry, not on the artisan aspect. “I would love to see [our main political parties] focused on the artisanal element and they still quite haven’t got there yet” (J, line 377–378). Interviewees (K, M, and J4) think the state agency Bord Bia are efficient at promoting Irish food but K1 believes that Failte Ireland and Tourism Ireland still put “food on the side”. Her view regarding the Taste the Island [initiative] was that it was just for local people, so they are “thinking in a bubble again”- “I don’t think it reached … outside [the country] very well” (line 291–295). Overall, critic “J’s” opinion is that the state agencies can’t differentiate like he can say, i.e., A is better than B regarding the food offering from various cities or counties in Ireland: “They have to put across a more generalized message, but they have woken up to the fact that food is a very, very important thing for Irish visitors” (Interview J, line 498–500).

Both interviewees A and M suggest that the way to bridge “the gap” in perceptions is through education, not by continually referring to the quality of Irish food. Hence, this concept relates to how respondent K spoke about how her perception of Irish food changed due to living in the country for 15 years (so much so that she presently promotes it to tourists via food tours): “When I moved here … I didn’t think Ireland had great food to be honest. It has changed a lot for me. You have so much choice now … in the countryside and in Dublin … it’s improved a lot” (Interview K, line 110–113).

Theme 3: a breakdown of hierarchies

Theme three recognizes a shift within Ireland’s food culture which demonstrates how two established societal hierarchies, have collapsed. These are a French culinary doctrine and an elitist restaurant culture (both strains of societal hierarchies also visible across Europe).

a) French Culinary Teaching

Half of the interviewees discuss a turnabout in culinary training in Ireland; a move from the repetitive, traditional French training to a freer teaching approach where students are taught instead to think critically and reflectively. “It’s not about mastering your technique as it was years ago. The chefs before they were just told to, ‘do this’!” (A, line 27–28). Educator M explains that this change from a more traditional teaching doctrine is evident in the Dublin University where he teaches. He reflects that over the years there was, “a change of knowledge … in the past, it was an empty head that was being filled and trained in a very classical way but was not asked to think outside of that box or to look at any other cultures” (M, line 325–328). Similarly, Interviewee A observes, “in terms of a French classical kitchen, chefs just had one role and then they moved into another role but now they need to be aware of everyone’s roles” (line 20–24). As a result, this novel teaching practice has impacted on the recent generation of chefs in Ireland in regard to how they approach and prepare food which in turn has boosted their confidence and bestowed a freedom to their level of creativeness.

In the literature, the Nordic Food Movement is noted as having been instrumental in introducing an alternative to or change from the traditional French culinary style of teaching. Interviewee J maintains, “[Irish Chefs] pull ideas from everywhere, they refine them … they are not just simply churning out the same dish … I think it’s one of the reasons why that French cooking has lost its sheen; is that it suddenly became repetitive” (line 147–152). It is important to note, the Nordic kitchen ethos is also modeled on a non-hierarchal framework, similar to the business model which is practiced at The Fumbally café in Dublin and the approach adopted by the Gather & Gather team at Airfield Estate, Co. Dublin.

b) an Exclusive Restaurant Culture and Two Levels of Food Media

The researcher finds that a distinctive element emerges from the interviews given by M and J, one which signifies a clash of viewpoints formed around Ireland’s restaurant culture, food media, and food guide offerings. Respondent M describes two levels of food media in Ireland; one level directed at “mainstream” food lovers from the general public, while the other is directed at “esoteric” foodies. He explains the concept further:

Everyday people who are also interested in food but maybe get their information from mainstream radio, telly [television] etc. Which is sort of the Neven Maguire side as opposed to the more … esoteric, in the terms of the like…[of] JP [McMahon]

Furthermore, he points out how: “There were two schools of thought in France amongst the critics and the guides. You had the Michelin Guides on one level and then on the other you had the Gault and Millau Guide” (M, line 462–464). These two schools of thought are represented and can be applied to Ireland: designating the two separate levels into, the Guide Michelin (as serving an esoteric audience) and the McKenna’s Guide (as serving a mainstream audience), respectively. This concept is backed up by “M” and “J” in the research as follows; M contends:

Gault and Millau were always seen to be championing new ideas and innovation. Whereas I always felt that the McKenna’s were the Gault and Millau of Ireland, as opposed to Michelin. They were nearly anti-Michelin in a way.

While food writer interviewee J and author of the McKenna’s Guide also addresses this topic (unaware that another interviewee has discussed it). He maintains:

Michelin has always had a big hierarchal system, we [McKenna’s Guides] don’t rate our restaurants in hierarchy, there might be some of them that we stress are particularly dynamic and creative.

In addition, he states that “Michelin for example, and … Gault Millau is another one that are really just writing about a restaurant culture, and we try to write about a food culture” (J, line 55–57). Hence, it is at this point, the researcher discovers a shift occurred in the last 30 years within Ireland’s food culture which resulted in a fracturing away from an elite restaurant culture. The researcher believes the formation of the McKenna’s Guide as an alternative media source was a key factor and may even have been a fundamental cause for the occurrence. Going back to the literature again:

The McKenna’s stated remit [in 1995] was to expose and celebrate not just the wonderful organically produced foods which they discovered throughout the country but also the men and women behind the previously unchartered gastronomic subculture.

The researcher contends that it is during this time that the focus is shifted from a conventional and somewhat “exclusive dining” experience and instead refocuses on the “eating” experience, which relates to the “provenance of the food” or the “food produce and producer” that restaurants select, and diners choose to eat. It is also imperative to recognize a restaurant that may have initiated this and one which has been connecting to local food producers, celebrating food provenance and already offering the “farm to table” style of dining or what is now known as “farm to fork,” was Ballymaloe House (a concept also practiced in the U.S. by Alice Waters). This Cork based Country House restaurant was established during the mid-60s by Myrtle Allen who subsequently received her first Michelin star in 1975. Myrtle Allen is viewed as a prominent figure in Irish gastronomy and a revolutionary figure of Irish food culture. It is quite possible that she was a major influence on the McKenna’s outlook, as in the primary research, respondent J reveals:

Myrtle Allen so unique in Ballymaloe; she connected directly to the artisan. But a lot of people in Dublin, they were completely indifferent to that. When I think back to ’89 when we first started, you know there was a subterranean subculture but there was very little quality in the restaurant culture because restauranteurs hadn’t connected to the artisan.

From the primary research, it has become apparent that the food media offering changed during the nineties in Ireland when an alternative appeared in the guise of McKenna Guides and another independent Irish food guide which followed later, i.e., the Georgina Campbell Guides. Both of these celebrated a renewed sense of worth surrounding Irish cuisine and produce. As a result, these local food guides loosened the reliance Irish food lovers had on established French Food Guides as taste setters or what Bourdieu (Citation1984) recognizes as “tastemakers” in society, but not entirely.

Theme 4: influencing factors

This theme links back to the sub-research objective five: Investigate how the main food actors contribute to contemporary food culture. Its corresponding, interview question 11 (PD Code 8) queried: Who do you consider the main food actors to be? The theme reflects any influencing factor which has impelled change in Irish food culture, or which could impel change in the future such as individual actors or another country’s culinary culture, e.g., French food culture (in the past) and Nordic food culture (in present times); both of which were referred to earlier. From the primary research, the most prominent Irish “food actors” to surface were, JP McMahon (FOTE organizer & chef), Darina Allen (Ballymaloe House), Irish Food Producers (in general), and the Bord Bia (the state food agency). JP McMahon stood out as a most prominent food actor in Irish food culture since all of the interviewees considered him to be a main actor while other Irish chefs were listed too, particularly the young chef cohort recently emerged on the food scene (which includes Mark Moriarty). “The major change now is the locals actually believe in [Irish food] more than they did in the past … there are lots of chefs now that are prouder, they are shouting about it” (K, line 103–105). Interviewee J stated, “Darina is a major player” (line 436). Darina Allen, a zealous supporter of Irish food, trained as a chef and worked alongside Myrtle Allen in Ballymaloe House hotel. In the 1980s, she developed and managed their renowned cookery school. She is an active voice on food matters in Ireland and in recent years has campaigned for the need to introduce cooking skills as part of the school curriculum. Furthermore, it emerged from the interviews that the “knowledge” gained through education from third-level colleges and cookery schools like Ballymaloe House has played an important role in building “confidence”, “pride”, and “creativity” in their pupil cohort. As a result, this “pride” has trickled down to other food enthusiasts.

In addition, food agencies like Bord Bia were mentioned as being valued and were considered a major food actor by some of the interview respondents. Other “food actors” that emerged from the research were “Irish food producers”. Prominent words that arose around these actors were “proud”, “active”, and “enthusiastic”. Interviewees stated that Irish producers are very “active” food culture players and are becoming well connected in regional areas. “You have these food communities and people shouting more and connecting and more events” (K, line 328–329). This would also suggest that Irish food producers can now be considered to have some, if not all, of these traits. In conclusion, producers, prominent food actors, e.g., JP Mc Mahon and Darina Allen and the state food board could prove a valuable link in the promotion of Irish food and in improving or bridging the gap between the two perceptions that have developed around it, as aforementioned.

Theme 5: state body remits

Regarding government remits, Food Guide writer J4 remarks, “the one area where foodism/food appreciation hasn’t hit home is in the government which is kind of disappointing” (J4, line 357–358). He adds: “They are focused on the agricultural element” not the artisanal (line 375–376). During the interviews, it was relayed that the way to switch visitor’s perceptions from the “old” food perception was by educating people of the diverse-ness of Ireland’s larder (produce, products, and producers). In relation to Bord Bia performance reports of food exports, consultant “A” shares another lens through which this can be viewed: “It’s down to our exports and how our economy runs. Bord Bia it’s all about export, 90% of our food in Ireland is exported and the import; we need to split that” (A, line 302–304). Furthermore, he argues, “we need to reduce our imports and our exports and keep more produce here” (line, 304–305). His underlying reason for this is expressed in the fact that, there are numerous countries around the world with access to quality Irish food:

Like seafood you can get great Irish seafood in China or Japan, and they do very little with it. Compared to Ireland, we don’t get access to it at all … it’s the same with the beef, our beef is amazing but we’re getting the second-grade beef in Ireland. The best gets exported all the time.

Bord Bia contend that by bringing, “Ireland’s outstanding food, drink and horticulture to the world, [they are] thus enabling growth and sustainability of producers” (Bord Citation2020a). In the interview, “G” explains that “there are two pillars within [Bord Bia] that we developed: Origin Green and Food Brand Ireland more recently” (G, line 44–46). Both are useful resources for producers.

However, Ireland should continue to export vast amounts of food and to import substantial amounts, and this raises a question of food security for the future, particularly, if extreme circumstances occur such as the event of another World War, harvest loss or crop devastation from diseases or indeed famine. As a country, lessons may not have been learned from the past about how to create stability and security surrounding food sourcing.

Conclusions & recommendations

This study aimed to examine contemporary culture in Ireland through the lens of the foodism phenomenon and the habits and traits evident in foodie subculture. It determines the major shifts that occurred over the last 60 years were, an evolution of Irish cuisine, an increase and diversity in food media, the collapse of a traditional teaching doctrine, a change in restaurant culture, and a rise in the availability of artisan food. The artisan food movement was given a giant lift by Myrtle Allen during the 60s which in turn influenced and led the McKenna’s and other food guide writers to further proliferate the message in later years. It is apparent from the research, that there is a visible disconnection with how the state relates to homegrown/home-produced food and drink produce compared to the average consumer in Ireland (particularly as large percentages are still sent abroad). At government level, if the shift is made to revalue Ireland’s producers and farmers, this could be the switch that trips the light of change. Presently, more government backing is needed for producers and farmers alike, to enable them to tackle environmental, or biological problems that may arise or even mundane issues such as annual rising costs or extortionate energy bills. It would be a valuable asset to also have a prominent food enthusiast/actor/voice as an advisory to the government or elected as an official to a corresponding state department.

A subculture or a Mainstream Culture

It was established from the literature, due to a rise of wealth experienced by a fraction of the population during the Celtic Tiger years, some began to dine out more frequently. There was an increase in both haute cuisine in Dublin restaurants and in the number of Michelin stars rewarded (Mac Con Iomaire Citation2011, 547). During this time, the Irish were “desperate to redefine” themselves via more sophisticated types of food and forms of eating (Boucher-Hayes and Campbell Citation2009, x). In addition, “Hibernian Cosmopolitans” from this boom period as described by (McWilliams Citation2006, 222) resemble Barr and Levy’s 1980s foodie persona. During this economic upturn Deleuze asserts, “Ireland entered the age of hyperconsumption,” hence: “this society of ‘hyperchoice’ is perfectly suited for the emergence of foodies” (2014, 144).

According to the research, half of the interview respondents believe the foodie tribe is mainstream due to the proliferation of gourmet foodstuffs in supermarkets and also, to do with the attraction of foodism to follow, as a trend. The other interviewees stated that foodies are still a sub-culture which is constantly expanding, and one of them noted, this is due to the range of foodstuffs available and “word of mouth.” Furthermore, it surfaced from the interviews that foodie culture in Ireland is split into two tribes, “mainstream” and “esoteric.” This concept supports Barker’s definition in the literature relating to societal sub-groups: “The notion of an authentic subculture depends on its binary opposite e.g., a mass-produced mainstream” (Barker Citation2012, 429). What distinguishes these two groups is the type of media they consume and also whether they are “knowledgeable” or “not so knowledgeable” when it comes to educating themselves about food matters.

Feeding foodie philosophy?

In the literature, Pigott (Citation2006, 19) listed her food tribes’ traits are: “provenance, seasonality, artisanal, and single-estate”. While the practice of foodism in (Ireland Citation2019) does indeed still feed foodie subculture philosophy, it has become apparent from the primary research that over the last few years, the subgroup’s doctrines are albeit slowly trickling into the mainstream. Irish consumers have become more “food savvy” and are embracing the concepts of organic, shopping locally, and supporting artisanal producers more as concluded by the Bord Bia Report (2020b). However, another factor may also be down to them becoming more environmentally conscious and aware. Johnston and Baumann (Citation2010) mention the turmoil that exists within the foodie persona regarding their desire for democracy and distinction in society. This has shifted proportionally within the mind-set of the contemporary Irish foodie with a greater pull in the democratic direction to further feed their hunger for knowledge and self-improvement and to instead use this as a mark of distinction. In the literature (Thornton Citation2005, 187) surmises that, “subcultural capital is not as class-bound as cultural capital”. The researcher concludes that academics remain divided on whether class is still a specific characteristic that defines the foodie tribe.

Contemporary Irish food culture is not just restaurant culture

The research demonstrates that a fracturing of an elite restaurant culture occurred within Irish society. During the mid-nineties, an unconventional type of restaurant was introduced in the guise of a more “communal” dining experience; then American-styled coffee culture businesses arrived mid-2000s. These and other factors within the restaurant industry consequently influenced a more democratic restaurant culture which has allowed space particularly in the capital city, for food lovers to sample every variety of eatery from; esoteric Michelin restaurants to The Fumbally’s egalitarian establishment, and hip weekend hangouts such as 777 to food trucks; from bohemian food markets to doughnut shops, and ice-cream parlors to artisan pizza places; venues which blend from back alleys to main streets. It is apparent, that the Michelin Guide recognized this societal shift occurred within other European countries’ “casual dining” scenes, as it cast a more democratic awarding system net by introducing the Bib Gourmand rating from 1995, which “is a separate category for restaurants that serve great food at reasonable prices” (Dixon Citation2008). During 2020, Ireland was awarded 21 Bib Gourmands by the French restaurant guide.

In contemporary Ireland (for those of us who have the luxury of knowing where their next meal will come from), it is important to consider and question what is Irish food? In relation to, our identity and national pride. However, it is also crucial that we can distinguish restaurant culture from that of food culture (the lines of which became somewhat blurred in Ireland during the pandemic years) to avert becoming too focused on or dazzled by Michelin stars. Education is a valuable element to use to change perceptions as it provides people with the power to critically evaluate for themselves, to not rely entirely on the advice or recommendations of societal “taste setters”. After all, taste is subjective. Hence, Irish food culture is not solely represented by “restaurant” culture, nor does it encompass the tradition of agriculture or the commerce of industry in its totality. It is comprised of attitudes, tastes, tools, traditions, and actors from the past and present.