ABSTRACT

Organizations realize that their license to operate and the supportive behavior of their stakeholders relate to how they come across. If the identity of an organization is not a single, but multiple it may face unique challenges in strategic communication. The purpose of this study is to identify how the reputation and legitimacy of such a multiple identity organization (MIO) are affected by its performance and communications. Building on organizational identity theory, insights from corporate communication, and stakeholder theory, the potential vulnerabilities are listed through theoretical deduction and are illustrated by the case of Sanquin, the Dutch blood supply foundation. The case assessment relies on interviews with stakeholders and journalists, complemented with an analysis of newspaper headlines. The mismatch between the identities endangers legitimacy because legitimacy is based on the conformity to norms and values, the area where the identities clash. The inherent tension between the ideological and utilitarian identity cannot be avoided completely, but a strategic communication policy that manages the balance between the identities in organizational communication could help a better understanding of MIOs. The case offers insights into how creating this balance might be considered in the development of strategic communication of MIOs.

Introduction

How an organization is perceived and evaluated in terms of its reputation and legitimacy is of utmost importance for its license to operate. Academic literature is ambiguous about the relationship between organizational identity multiplicity and legitimacy. For the foundation of strategic communication, it is important to unravel this relationship, especially since the legitimacy of multiple identity organizations (MIOs) is under public discussion, e.g., blood supply (Vaessen, Citation2018b) and social housing corporations (Blessing, Citation2015), after several scandals and incidents (Geurtsen, Citation2014). An MIO is, in the context of this study, an organization that houses an ideological identity as well as a utilitarian identity. These different types of identity will be explained more thoroughly in the next section. Relying on different methods and data sources, the overall goal of this study is to determine which specific challenges MIOs face to retain favorable perceptions, a sound reputation, and high levels of legitimacy and to provide a richer understanding of the role of organizational identity in strategic communication. Strategic communication is about how an organization functions to advance its mission by all the organization’s communication. The communication is reflexively shaping the organization and its identity (Overton-de Klerk & Verwey, p. 370). We focus on specific challenges that a multiple identity poses to communication strategies of the organization involved. We will elucidate the vulnerability of legitimacy of a MIO by focusing on the Dutch Blood Supply Foundation Sanquin.Footnote1 Guarding legitimacy might be the key challenge for an MIO. The crucial role that the media play as co-constructors of organizational identity in their intermediate position between the organization and its stakeholders will be discussed.

Reputation and legitimacy play a crucial role in private as well as public and semi-public organizations. If there is no congruence between an organization, its activities, its communication, and value systems on the one hand, and the expectations, activities, and value systems of the larger social system in which it operates on the other hand, it is difficult to gain legitimacy. And without legitimacy it is difficult to find resources, active and passive support, and a license to operate (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2019). Frandsen and Johansen illustrate the vulnerability of legitimacy by the severe damage to reputation and legitimacy of Danske Bank when the “culture of greed” at the Danske Bank was brought into the open in a money laundering affair.

Academic literature on multiple identity organizations is scarce (but see for examples Gioia et al., Citation2013; Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000) and the interplay between how such an identity is communicated, and the organization’s public perception, reputation and legitimacy has hardly been investigated.Footnote2 Our contribution is to fill this gap. In this paper we shed light on how identity multiplicity affects an MIO’s reputation and its legitimacy on a theoretical basis and by discussing a casus that serves as an instance of identity multiplicity, as a basis for the organization’s strategic communication and strategic communication management (Zerfass et al., Citation2018). Here, we rely on an empirical evaluation by means of interviews with stakeholders and journalists, complemented with an analysis of newspaper headlines.

Literature review

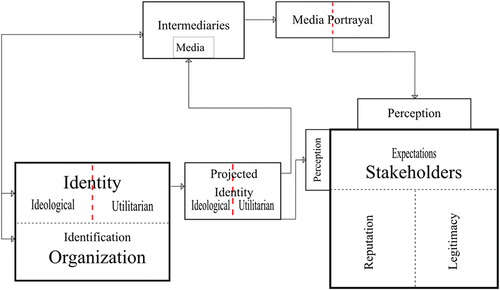

In this section we give a brief overview of relevant notions within three strategic communication underlying academic fields: (1) organizational (multiple) identity, (2) corporate communication (reputation and legitimacy), and (3) stakeholder theory. Applying these three academic disciplines underlines the interdisciplinary character of strategic communication. It is a coherent triplet since organizations act consistent with their self-view (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 180) and, combined with their projection of identity (Argenti, Citation2013, p. 72) where communication comes into play, their behavior impacts the reputation and legitimacy for general audiences and specific stakeholders (Friedman & Miles, 2006). On a societal level, the strategic question for the organization is to what degree the organization is embedded in society, in harmony with prevailing values (Zerfass et al., Citation2018, p. 497). We will first introduce the (multiple) identity concept and then reputation and legitimacy, which can be seen as key outcome variables affected by the identity multiplicity of organizations.

What is identity and what is a multiple identity organization?

As introduced above we focus on how a multiple identity organization (MIO) comes across, since this kind of identity could affect reputation and legitimacy. What is such an organization?

For the theoretical framework of this paper, the basic assumption is that organizational identity is underlying and affecting reputation and legitimacy. The identity of an organization is derived from the categories it is associated with and denotes what the organization is and is not (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 182) and specifies how the organization is both similar to and different from other organizations, a specification that is also key in reputation and legitimacy definitions. Organizational identity consists of a set of core characteristics, traits of the organization that its members find central, enduring, and distinctive features that are typical for their organization (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985, p. 292). These characteristics define the organization, and they give the employees an anchor to identify with. When the answer to the question what the defining core of the organization encompasses is not a single one, but multiple, and especially when those differing answers could be linked to different and even problematically compatible underlying value systems, it is a matter of a multiple or a dual identity organization (e.g., universities, cooperatives; Schultz et al., Citation2009, p. 15). We will use the most frequently used notion “multiple”, although this might sound as an oxymoron, even if there are just two identities.

When each of the multiple identities inherent in the organization is held by all organizational members, we call it a holographic multiple identity. In the case of ideographic multiplicity, there is a lack of consciousness about the existence of the multiple identities and two seemingly opposed value systems within the organization (Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000). The multiple identities are retained by specific subgroups that exist in different parts of the organization (Sillince & Brown, Citation2009). The holographic and ideographic MIO are ideal types. In practice, the organizational identity type can be situated at any point on the “holographic–ideographic scale.” Both the holographic and the ideographic MIO convey characteristics of the multiple identities in its communication. When the communication about the organization is created by third parties like journalists, the balance between the prevalence of the identities may differ from the desired image (Rindova, Citation1997, Heckert et al., Citation2021). Summarizing, the organizational identity is defined internally by its members, the projected identity is the identity communicated by the organization. The external perception-oriented identity is often called organizational image. In particular for MIOs, they can differ substantially and structurally.

A previous study (Heckert, Citation2019) found that the two identities often present in an MIO (Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000) – the ideological and utilitarian identity, defined by the organizational members – were clearly present in the casus that serves as an illustrative example in this paper as well, Sanquin.

Ideological and utilitarian identity

The “ideological” system (emphasizing traditions and traditional symbols, internalization of an ideology, and altruism) is like that of a church or family. Identity traits that are associated with the ideological system are characteristics like “human centered” and “social.” These characteristics express an organization’s tendency to foster the human well-being and the common good. The utilitarian system (characterized by economic rationality, maximization of profits, and self-interest) is like that of a business (Albert & Whetten, Citation1985; Foreman & Whetten, Citation2002; Schultz et al., Citation2009). Identity traits that are associated with the utilitarian system are characteristics like “process centered,” “commercial,” and “business-like.” These characteristics reveal themselves in how an organization advances its own profitability and continuity. Here, we want to outline the specific challenges MIOs face concerning public perception, reputation, and legitimacy. We expect these challenges to be complex because of the complex nature of organizational multiple identity. There are indications that only the organization that can balance contradictory logics by establishing a common identity can survive (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010).

In the projection of their identity MIOs tend to over-emphasize their ideological identity (Heckert et al., Citation2020; Taylor & Littleton, Citation2008). This overstressing is not necessarily present in their public appearance, for example, in media coverage. The balance between the identities in the media portrayal can change over time. If the identity balance in a semipublic or other non-profit organization is developing in one direction, it is usually in the direction of the utilitarian identity (Heckert, Citation2019; Citation2021). Also, we identified the antithetical value systems as the potential drawback of an MIO’s credibility. Nevertheless, it seems safe to infer that organizational identity multiplicity does not necessarily affect reputation judgments positively nor negatively. After all, stakeholders’ reputation assessments are based on competence and emotional appeal drivers and not primarily on values (Wæraas & Byrkjeflot, Citation2012). Conformity to norms and values chiefly affects legitimacy evaluations.

What are reputation and legitimacy?

Companies and organizations often worry about how they are perceived by internal and external stakeholders, how their overall media reputation adds company value (Van Den Bogaerd & Aerts, Citation2015, p. 27) and about the impact of these perceptions on their reputation and legitimacy (Gibson et al., Citation2006, p. 15). They realize that their license to operate and the supportive behavior of their stakeholders relates to how they come across. The perceptions and the evaluation of an organization by stakeholders is highly affected by pre-existing thoughts about and expectations they harbor for this organization. Expectations contribute to stakeholders’ assessments and perceptions and can lead to behavioral responses. Expectations act as reference points for future assessments and guide how the organization is perceived, making unmet expectations a potential reputation threat or even an indication of a legitimacy gap (Luoma-Aho et al., Citation2013, p. 248). First, we will describe what is understood by reputation and legitimacy.

Reputation

Reputation can be defined as “the observers’ collective judgments of a corporation based on assessments of the financial, social, and environmental impacts attributed to the corporation over time” by (Barnett et al., Citation2006, p. 34). Reputation is often measured by stakeholders’ scores on standardized reputation dimensions, for instance, RepTrak (Fombrun et al., Citation2015) and TRI*M. The TRI*M index is a commonly used index in stakeholder management, originally designed for the profit sector (O’Gorman & Pirner, Citation2006). It is now also widely applied in the public sector (Sondervan, Citation2008). Reputation indices are generally based on competence drivers (e.g., financial, products, innovation) and emotional appeal (e.g., sympathy, trust, leadership).

Reputation is affected by identity. Although sometimes we could be surprised by the behavior of an organization we know, identity is generally the most reliable predictor of its future conduct. The organization acts consistent with its self-view (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 180). In a reputation judgment, stakeholders’ perceptions and past experiences with the organization are used to identify the unique organizational features and to anticipate the likely future behavior of that organization, including its reliability and honesty. That is why the analysis of past actions of the organization plays a key role in the formation of a reputation judgment (Bitektine, Citation2011, p. 162).

Good organizational reputation among stakeholders is understood as reputational capital that contributes to reduced transaction costs, easier recruitment, added employee loyalty as well as to the legitimacy of the organization (Luoma-Aho, Citation2007, p. 124). Stakeholders use their experiences for identifying, categorizing, and expectations-building. The upshot of these observations will, from an identity point-of-view, be determined by the vigor of the one identity or the other, or the well-balanced combination of the two. The multivocal messages could initially confuse stakeholders. The first research question is:

RQ1: How might organizational identity multiplicity confuse stakeholders in their understanding of the organization?

Legitimacy

Legitimacy is the generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions. Legitimacy is socially constructed: it reflects a congruence between the behaviors of the organization and the shared beliefs of some social group and thereby dependent on a collective audience (Suchman, Citation1995, p. 574). In addition to legitimacy being an evaluative judgment, based on conformity to social norms or values, it also presupposes compliance with legal requirements (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 184), but should not be confused with legality. Having benchmarked the organizational features and performance on a set of relevant dimensions against the prevailing social norms and regulations, the stakeholder renders a legitimacy judgment as to whether the organization, its form, its processes, and its outcomes are socially acceptable, and hence should be encouraged (or at least tolerated), or are unacceptable, and hence the organization should be sanctioned, dismantled, or forced to change the way it operates (Bitektine, Citation2011, p. 162). Organizations that are perceived as legitimate are likely to receive support and resources from constituents and are also more likely to gain the commitment, attachment, and identification of members (Elsbach, Citation2003, p. 301). The dissemination of judgments through discursive means plays a major role in the rise and fall of institutions and organizations (Bitektine, Citation2011, p. 164).

In identity terms, legitimacy is an evaluative statement about the appropriateness of the organization’s central, enduring, and distinctive features, relative to a self-defining set of social requirements (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 179). The potential consequences of organizational identity multiplicity might be more delicate, complex, and far-reaching for legitimacy than they are for the reputation of a firm. A legitimacy judgment is specifically oriented towards compliance with social values and beliefs. The ideological identity, however, is based on completely different values and beliefs than the utilitarian identity and the underlying value systems of the two identities are even antithetical to some extent. When stakeholders evaluate the organization’s performance or communications in the utilitarian domain with a set of values belonging to the ideological domain, their final legitimacy judgment might be negative. And the other way around: utilitarian values are not very well-suited to judge performance and communications in the ideological domain. This unconscious quest for the right criterion leaves the legitimacy judgment in dire straits. Our presupposition is that organizational multiple identity can endanger legitimacy.

Relationship between legitimacy and reputation

The difference between legitimacy and reputation is that legitimacy emphasizes the social acceptance resulting from adherence to social norms and expectations that qualify one to exist, the fit with normative values and beliefs (Rindova et al., Citation2006, p. 54), whereas a reputational assessment of the organization does not focus on “the appropriateness of an organization’s characteristics and conduct, but on the effectiveness of its performance – as a predictor of that organization’s ability to meet future performance-related expectations” (Foreman et al., Citation2012, p. 184) and it is based on comparisons among organizations on various attributes (Deephouse & Carter, Citation2005, p. 350). Summarizing it may be stated that reputation focuses on differentiation whereas legitimacy focuses on homogeneity (Deephouse & Suchman, Citation2008).

The distinction between reputation and legitimacy is not a mere theoretical contrast. There is empirical evidence for the different effects they bring about. In the commercial banking industry for instance, it appeared that higher financial performance increased the reputation but not the legitimacy of a bank (Deephouse & Carter, Citation2005, p. 329). This could be explained by the fact that reputation judgments resemble aspects of the utilitarian performance, whereas legitimacy judgments depend on an organization’s adherence to ideological norms and values. MIOs need to perform in both domains.

For public organizations having legitimacy for what they do is judged more important than a strong reputation (Wæraas & Byrkjeflot, Citation2012, p. 201). This might be the same for semi-public organizations like our case study organization.

Having defined reputation and legitimacy as stakeholder assessments, we present the second research question. This question inquires the potential consequences for an organization housing two identities based on antithetical values systems. In the following section we will delve into stakeholders and their significance.

RQ2: What are potential threats for reputation and legitimacy of an MIO?

Stakeholders and intermediaries

Stakeholders

The oldest definition of stakeholders goes back to 1963. From the fifty-five definitions that Friedman Andrew and Miles (Citation2006) reviewed out of hundreds of different published definitions (Miles, Citation2012, p. 285) we choose the relatively recent definition of Gibson (Citation2000, p. 245): stakeholders are “those groups or individuals with whom the organization interacts or has interdependencies and any individual or group who can affect or is affected by the actions, decisions, policies, practices, or goals of the organization.” An organization’s stakeholders may include governmental bodies, political groups, trade associations, trade unions, communities, financiers, suppliers, employees, and customers (Freeman, Citation2015). The interests of all stakeholders are of intrinsic value (Friedman Andrew & Miles, Citation2006, p. 29).

Media as intermediary actors

The focus of strategic communication researchers is typically on the organization and its stakeholders. But there is a third type of actors: intermediaries. The media are the most salient example. They are embedded in interconnected social networks (Yang & Bentley, Citation2017, p. 276).

Some researchers define them as “influencers” or “stakeholders without stakes.” Other researchers call them “stakeholders by proxy” (Frandsen & Johansen, Citation2015, p. 269). They hold an important position in the interplay between organizations and their (other) stakeholders.

The importance of a favorable media coverage as an asset of the organization (Deephouse, Citation2000, p. 1108) is uncontested and the literature about agenda setting by the media (e.g., McCombs, Citation2014) and shaping the public opinion (e.g., Holtz-Bacha & Strömbäck, Citation2012) is abundant. Also “mediatization,” a concept that indicates the extension of the importance of the media into all spheres of society and spillover effects on organizations and stakeholders, has gained growing attention of scholars (e.g., Fredriksson et al., Citation2015). But, despite frequent references to the role of the media as a source of legitimacy for industries and firms, the media’s role in shaping public perceptions of organizations and firms has relatively long been unexamined and undertheorized (Rindova et al., Citation2006, p. 67). In recent years however evidence is growing for the impact of media coverage on corporates (e.g., Jonkman et al., Citation2020) and public organizations (e.g., Jacobs & Schillemans, Citation2016). The way news pieces are presented can determine how audiences form their opinion about public issues (Soderlund, Citation2007, p. 31). The agenda-setting effects of the news media on people’s attention to comprehension of and opinions about topics in the news can also influence corporate reputations (Carroll & McCombs, Citation2003, p. 36). One way in which journalists can develop the character of a firm is by providing information about the firm’s culture, identity, and leadership, because these organizational attributes reveal values, beliefs, and behaviors that are distinctive characteristics of the organization (Rindova et al., Citation2006, pp. 57–58).

Other intermediary actors, for instance, trade associations, will not be discussed here, since they play no or just a subordinate role for MIOs. The focus is on research question 3.

RQ3: How do legitimacy threatening issues resonate in the media?

shows how the concepts we discussed relate with and affect each other. In our analysis, we will try to find theoretical and empirical support for this interplay. We will refer to this model throughout the analyses below. The focus of this study is on the right side of the model.

The model shows the MIO with its ideological and utilitarian identity, separated by a dotted line. It marks the (permeable) border between the ideological identity and the utilitarian identity. These identities are communicated by the organization itself. Both aspects of the ideological and the utilitarian identity of the organization are conveyed to stakeholders by behavior, communication, and symbols (Cornelissen & Elving, Citation2003): the “Projected Identity” (). The public or specific stakeholders perceive organizational messages (“Perception” in ) with dominantly ideological identity characteristics as well as messages with dominantly utilitarian identity characteristics. This would be natural in an ideographic multiple identity where the identities “house” in different parts of the organization, and the communications could even be originating from these different business units. But in a holographic multiple identity too, both identities will pervade the external communication and the perception by stakeholders, even if there is a dominant coalition that commands all communication channels and prefers to tap into one of the identities (Heckert et al., Citation2020). An organization does not orchestrate all organizational communication. The perception of the projected identity is only part of the input that stakeholders assess for their reputation and legitimacy judgments. Stakeholders construct and articulate expectations and images of the organization based on information, perceptions, and interpretations they develop or receive from both organization-generated and outsider-generated communication, as audiences try to make sense of the organization in an image-filled information field. Media portrayal is an important part of this image formation (Price et al., Citation2008). The media base their portrayal of organizations on their own news gathering. This media portrayal does not only affect external stakeholders, but also the way organizational members define and assess their organization (Dutton & Dukerich, Citation1991), which closes the loop.

The impact of multiple identity case study

In the following section the conceptualization sketched above will be applied to a specific case to answer the research questions. We will introduce the case organization using its own description.

Sanquin was established in 1998 through a merger between the Dutch blood banks and the Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service (CLB). The Foundation is responsible for blood supply on a not-for-profit basis and advanced transfusion medicine as such that it fulfils the highest demands for quality, safety, and efficiency. Sanquin delivers products and services, conducts scientific investigations, and provides education, instruction, in-service training, and refresher courses. On the basis of the Blood Supply Act, Sanquin is the only organisation in the Netherlands authorised to manage our need for blood and blood products. It is also a not-for-profit organisation and thus has no profit motive. Sanquin employs approximately 3,000 workers across the Netherlands. (Sanquin, n.d.)

The order to provide blood plasma-derived medicines (“blood products” in the quote above), is received from the Minister of Health. The pharmaceutical products are meant for Dutch patients in the first place but are sold on an international competitive market. This legally based multiple identity makes Sanquin a most likely case of an MIO.

In a previous study, identity issues resulting from this identity multiplicity were identified (Heckert et al., Citation2021). They concentrate on the tension between the identities that are based on an ideological and a utilitarian value system. This tension expressed itself when for instance, the non-remunerated donors were pleading for getting their travel expenses compensated, when the top executives were accused of accepting a too high remuneration, or when a rationalization of blood centers caused compulsory redundancies of staff and lengthening travel distances for donors.

Who are sanquin’s stakeholders?

In an enumeration of the most important stakeholders, (350,000) donors come first. Sanquin is completely dependent on the voluntary donations of blood donors who are recruited from the adult Dutch population. Without new donations the blood supply would be running out within a week. This means that public opinion in general and the attitude towards the organization of donors in particular is paramount. Because of the societal impact of the availability of safe blood, Members of Parliament are also important stakeholders. The Ministry of Health and some of its inspectorates have a legal stake in the organization. The key stakeholders in the utilitarian domain are hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and other life science organizations. The role of the media as intermediary stakeholders for such a “high-reliability organization” (Belasen, Citation2008, p. 19) is evident. Below we will delve into how stakeholders perceive and judge this multiple identity organization.

Method

To answer our research questions, we relied on a variety of research methods and data. First, how stakeholders and journalists contextualize MIOs was examined by interviews. Second, the blood donors’ assessment was derived from a third-party survey and interviews. Finally, an analysis of newspaper headlines served to determine how MI issues resonate in the media. This mixed-method approach was chosen to obtain solid answers to our research questions: the qualitative insights from the interviews are corroborated with quantitative data from surveys as well as findings from a content analysis of news headlines.

In-depth semi-structured interviews were held with ten, well-informed, stakeholders in 2016 and with a dozen of journalists in 2020–21Footnote3, to investigate their understanding (RQ1) and evaluation (RQ2) of an MIO. The interviewed stakeholders have a long-range experience with Sanquin (3–16 years) to base their reflections on, also with hindsight. The data collection ended when saturation was accomplished and no new answers to the research questions were obtained (Saunders et al., Citation2018).

The stakeholders were selected based on having for the case organization’s legitimacy relevant positions in different areas and being familiar with the organization (Appendix 1). The selection mainly focused on key stakeholders with seasoned insights in the organization rather than on blood donors, whose views were covered by external research (see below). The journalists were chosen after a Nexis Uni search for articles about the organization in Dutch news media. The journalists that had been writing about the case organization most were selected (Appendix 2). The interviews took 30 to 60 minutes in a quiet room on their preferred premises with no other people around or in an online conversation if needed for health security reasons. The interview recordings were transcribed manually or automatically (by Amberscript.com) and then corrected. For the process of open coding Atlas.ti software was used, applying procedures derived from qualitative methodological literature (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015; Golden-Biddle & Locke, Citation2007). After close reading of the transcripts twelve codes were added. Then the codes were clustered in reputation and legitimacy statements. Examining the quotes enabled listing data similarity and variation per topic. Revealing quotes were marked. To the interview quotes interviewee numbers were added, corresponding with the list of interviewees (Appendix 2).

Furthermore, a concise text analysis has been performed of news media article headlines and the articles where necessary, to provide additional illustration for some of the insights gained in the interviews. The analysis builds on a previous quantitative content analysis study (Heckert et al., Citation2021). It investigates if reputation or legitimacy threatening issues arising from identity multiplicity resonate in news media (RQ3). The articles were obtained by another Nexis Uni search for the 100 most relevant articles, relevance determined by the Nexis Uni algorithm, about Sanquin in Dutch newspapers, issued between 2008 and 2019.

To corroborate our findings external sources are used as well. A qualitative research exploration provides the insights of blood donors about the two identities of the organization (True Research, Citation2014, RQ1). A quantitative longitudinal survey research, using a representative sample (N = 1,200) of the Dutch population between 18 and 65 years old, supplies us with information about reputation judgments (TNS NIPO,Footnote4 2014, RQ2). Both surveys were executed by trusted third parties (TNS NIPO and True Research) by order of the case organization.

Analysis

Stakeholders’ confusion (RQ1)

When it comes to the exposure to identity characteristics and their public perception, the particular nature of this organization is that about a million people of the ten million counting adult Dutch labor force have had personal experiences with Sanquin, because they are or have been a blood donor. This means that they have directly encountered the behavior, communications, symbols, and other tangible aspects of identity (Argenti, Citation2013, p. 72), at least of the identity of the Blood Bank which represents the organization’s ideological identity (box bottom left, ) best (Heckert, Citation2019). This one-sided exposure is amplified, also for non-blood donors, by the identity projection of the organization (box in the middle) in its external communication (Heckert et al., Citation2020). This means that, referring again to , the perception of the organizational identity (box bottom right) concentrates on, but is not limited to the ideological identity. The transmission of identity characteristics mediated by journalists’ portrayal (box top right) adds some characteristics from the utilitarian domain. Specific stakeholders, like Sanquin’s pharmaceutical or hospital clients, will be exposed more to utilitarian identity traits than others since their relationship with the organization is business-like. The stakeholders are confronted with identity characteristics “that would not normally be expected to go together” (Foreman & Whetten, Citation2002, p. 621) and qualify it as “confusing” (Int. S7). An MP considers producing medicines as “alien.” “It distracts from the main mission and introduces a shady business model” (Int. S3). A hospital official finds it difficult to understand Sanquin: “The organization is constantly in two minds with its non-profit activities in the Netherlands and commercial activities in Belgium and the United States” (Int. S5).

Only well-informed stakeholders seemed to consciously perceive the multiple identity status of the organization. A former high-rank Ministry of Health civil servant came straight to the point at the start of the interview: “The most distinctive is the hybrid character of the organization. At the one hand it is a public service and at the other it is a pharmaceutical company. To secure this hybrid character there should be a balance between the two contradictory faces” (Int. S8).

The first RQ inquired how organizational identity multiplicity might confuse stakeholders in their understanding of the organization. We conclude that stakeholders indeed find the two identities difficult to reconcile.

MIOs, legitimacy threats (RQ2) and the media (RQ3)

Stable reputation

A reputational judgment starts with the identification and categorization of a firm. Most people associate Sanquin with blood donation (TNS NIPO, Citation2014). Production of medicines did not pop up spontaneously as a Sanquin activity. When proposed, 9% of the Dutch adults recognized it. This low figure might be good for the organization’s reputation since the pharmaceutical industry’s reputation is low; not much better than that of the financial sector or tobacco companies (Kessel, Citation2014, p. 983).

Sanquin’s reputation, measured by a survey (TNS NIPO, Citation2014), was rather strong. The TRI*M indexFootnote5 was 53 (benchmark healthcare: 52, public utilities: 33, public authorities: 30). The general audience thought of Sanquin as an expert and a trustworthy professional. Pressure points in the external assessment bore a close resemblance to the identity traits the employees were worrying about (Heckert, Citation2019): lack of transparency, questions about proper handling of the blood revenues, integrity, sympathy, being a social organization, and worries about the foreign activities. Seventeen percent mentioned the commercial attitude (TNS NIPO, Citation2014). These objections might not have had a huge impact on the reputation level, but they are more likely to put pressure on legitimacy, discussed below.

Reputation and trust were higher among blood donors, but both were decreasing, compared with 2011 (reported in TNS NIPO, Citation2014). A previous study showed that the press coverage often focused on the supposed incompatibility of the identities. The tension between the ideological and the utilitarian identity was discussed in 13% of news articles (1998–2019) about Sanquin (Heckert et al., Citation2021).

This is for instance, substantiated in the newspaper article “The red gold.” “Red” refers to the blood donated by voluntary donors (ideological identity) and “gold” refers to the substantial revenues (utilitarian identity) it brings in. The article explains that the combination of the two is disputable (Volkskrant, Citation2008). This supports a positive answer to our third research question, that identity tension issues would resonate in the media, confirming the quantitative results of a previous study (Heckert et al., Citation2021).

Donors appreciated the not-for-profit status of the organization, but they reported a growing commercial character of the organization (True Research, Citation2014). Note that social and not-for-profit are characteristics of the ideological identity and that commercial is a utilitarian identity trait.

The interviewed stakeholders acknowledged the importance of how an organization is covered by the media (box top right). Investigating how journalists contextualized their role, drawing on our interview data we saw that journalists were aware that they were able to make or break organizations’ reputation: “Representation can be very probing” (Int. J3) and “Media are powerful” (Int. J8). They realized that organizations put a lot of effort in how they come across: “They have entire departments that are working on media exposure all day” (Int. J6), but they generally did not consider their impact when they reported on a firm or organization: “I understand that media messages have their consequences for an organization’s reputation, but it is not our mission to consolidate an organization’s reputation” (Int. J11). Several journalists recognized that a sound reputation can also reinforce itself through media attention. Journalists judge an organization by its reputation to decide “if we find this organization interesting enough to write about” (Int. J14). The trustworthiness of an organization as an oracle also depends on its business model: “a commercial organization is less credible than a non-profit” (Int. J9).

Endangered legitimacy

A legitimacy judgment is based on the conformity to norms and values. The ideological and the utilitarian identity do not share the same values. The potentially uncomfortable position (e.g., Glynn, Citation2000; Pratt & Foreman, Citation2000) of the multiple identity case organization was vocalized in quantitative surveys, qualitative interviews with stakeholders and by news media. Investigating our second research question – about the reputation and legitimacy risks – we identified the following four issues as legitimacy vulnerabilities of an MIO, i.e., Sanquin: lack of transparency and checks and balances, remuneration at the top, monopoly, and failing as a commercial enterprise. These four issues will clearly demonstrate the vulnerability of an MIO’s legitimacy.

Lack of transparency and checks and balances

The stakeholders’ criticism focused on behavior, as discussed below and on transparency. The remarks about transparency sometimes touch on the organization’s integrity, as in the next quote of an executive of the Dutch Health Council:

One always wonders if scientific authority is the source of Sanquin’s scientific claims, or a business model consideration. The organization justifies the product prices with the research costs. That is a shadowy story. And they seem to have an interest in this shadowiness (Int. S1).

Stakeholders emphasized that Sanquin should be transparent about the business model and cost structures: “It is difficult to understand why Sanquin houses all those activities. Producing medicines is foreign to its nature. Still, you must explain why you do these things and how, and what your considerations are” (Int. S3). Most of the interviewees think that the organization is not very successful in explaining its position. A former representative of the Ministry of Health (Int. S8) stated: “Sanquin doesn’t do many unreasonable things, but it neither puts a lot of effort in getting things understood and accepted.” He also worried about appropriate recovery mechanisms (Zeithaml & Bitner, Citation2003): “Checks and balances are of utmost importance. Which mechanisms are put into action when suddenly a Maserati drives up to the front?” Here, a utilitarian symbol par excellence, an executive’s Maserati, was judged with an ideological value: to exercise restraint with public money.

Remuneration at the top

Almost half of the respondents that graded the organization’s reputation unsatisfactory referred to the wages of the Executive Board (general audience, TNS NIPO, Citation2014). They criticized the combination of the non-remunerated gift of blood donors and the remuneration of the Board, thirty percent above “Balkenendenorm,” salary cap for Dutch government and civil service officials equal to the salary of the Prime Minister. This illustrates how multiple identity challenges legitimacy. The remuneration at this level seemed to be associated with the utilitarian identity while being evaluated from the ideological point of view. This was also voiced in some of the newspapers (e.g., “Sanquin’s top gets more,” Van Mersbergen, Citation2011, another underpinning of RQ3) and interviews with stakeholders. A member of parliament (MP) even called the identity multiplicity an identity characteristic and supposed the issue could become the divisive element for the hybrid organization model: “The image of the Blood Bank can become too commercial. It will be hard to recruit voluntary donors. The social basis is under fire” (Int. S2, identity characteristics in italic). The remuneration issue was also covered in news media headlines, for instance, “Donating is useful, but the fun is over” (Veenhof, Citation2009) and two years later: “Blood donors threaten to boycott for executives’ wages” (Efting, Citation2011).

Monopoly

The monopolist position of Sanquin as a blood supplier is part of the hybrid business model that constitutes its multiple identity, imposed by national government. It seems to evoke criticism, about the price level of products and about the appropriate disposition for commerce. In 2012 the price issue made it to the newspapers (e.g., Remmers, Citation2012: “Professor questions continuous price raises”) and in 2014 a medical specialist urged the government to let him buy blood in Belgium, because that would be a lot cheaper (Omroep Brabant, Citation2014).

A civil servant complained about the price level and again, transparency: “The price of a unit of red blood cells is about twice the price in neighboring countries. If you want to have a multiple identity you must accept the consequences. And where do revenues finally go to?” (Int. S8). The subject made it to the newspapers too: “Sanquin’s monopoly raises questions again” (Vaessen, Citation2018b). An MP and a client denounced the organization’s attitude: “Monopolism grows laziness” (MP, Int. S3). “Monopolists don’t listen to costs. Creating stimuli wouldn’t be so bad,” according to a client (Int. S6). These considerations initiate the next and final issue.

Failing as a commercial enterprise

Being a pharmaceutical company with global aspirations demands a business-like spirit. Some stakeholders consider the ideological legacy a barrier for real entrepreneurship. A representative of a pharmaceutical company denounces the organization’s bureaucratic character: “A new culture and a new set of skills is necessary. That takes time” (Int. S6). “Working for the Ministry of Health, I thought the hybrid organization model was a realistic model. Now I have serious doubts. Running a pharmaceutical company isn’t easy at all and this complexity has not been faced up in time” (Int. S8). Whereas the remuneration issue identified the legitimacy judgment with the “wrong” paradigm, these last quotes show the double-edged sword of multi-identity criticism. Once the utilitarian identity is acknowledged, the MIO’s identity as revealed by its behavior (, bottom box in the middle) can be criticized employing utilitarian standards. This mechanism was also illustrated by the following headline, holding ill-disguised irony: “Conquering America is blood-curdling for Sanquin” (Rengers & De Vrieze, Citation2014). It refers to the difficulties that the organization met in getting the Food and Drugs Administration’s permission to bring its blood-derived medicine on the American market. A few years later a journalist suggested that the organization was seized by panic for the FDA: “Level 1 alert at Sanquin’s Pharma: The FDA comes over” (Vaessen, Citation2018a).

We must realize that in this time and age members of parliament and the media in the Netherlands go over public and semi-public organizations with a fine-tooth comb. Housing corporations for instance, have lost their credibility in the course from 2006 to 2011 by focusing on utilitarian goals at the expense of their public duties (Koolma, Citation2011) and in 2021 the Dutch Tax Service was embroiled in a fine kettle of fish about its misbehavior against citizens (Frederik et al., Citation2021). The ideological–utilitarian tension and the David (the citizen) and Goliath (the institutions) combat provided a credible and consistent master frame (Snow & Benford, Citation1992) with a high chance of success in the public sphere (Koopmans & Muis, Citation2009). This yielded increased attention of the media for public and semipublic high reliability organizations and enabled critical interpretation, as this journalist articulates: “These organizations have brought a high status on themselves and when this is staggering only just a bit, then it’s interesting” (Int. J7).

The second research question investigated the reputation and legitimacy threats for MIOs. A reputation assessment that compares the accomplishments of an MIO with other organizations was found not to suffer much from its identity multiplicity. Conversely, an MIOs legitimacy, presupposing compliance with social norms, definitely appears to be at risk, especially by a lack of transparency of the organization’s communication. Reviewing the legitimacy issues discussed above we can conclude that journalists regularly pick them up for their productions, concentrating on remuneration questions and commercial failures. This answers the third research question.

Discussion and conclusions

The public perception and the evaluation by stakeholders of multiple identity organizations in reputation and legitimacy judgments is undertheorized, and underexamined empirically. This paper tried to fill part of this gap. Legitimacy rather than reputation appeared to be at stake for an MIO due to the, for audiences, incomprehensible combination of ideological and utilitarian values. Making sense of an MIO and rendering legitimacy to an MIO are difficult, and the critical perspective of the press on the supposed incompatibility of the identities poses an additional challenge. Especially when the MIO is publicly criticized, the utilitarian identity characteristics get a stronger emphasis, and the organization loses its position to dominate the identity formation and communication. Strategic communication plays a key role in disentangling uncertainties.

Although the term “strategic communication” suggests the idea of predictability and control (Overton-de Klerk & Verwey, Citation2013), we observed complex, often contradictory, and unintended relationships among the organization, issues, and identities and serious constraints for the organization to manage its communication. This observation informs the discussion within the field of strategic communication, acknowledging its complexity, given the fact that the organization’s environment imposes unwanted associations that distort the original intent of the organization’s identity projection (Murphy, Citation2014).

Discussion

The reputation judgment as a categorization instrument may encounter difficulties when the distinctive characteristics of an MIO come from different “worlds.” More severe judgment complications arise when legitimacy is concerned. A legitimacy judgment sees to the appropriateness of an organization’s behavior within a system of values and beliefs, whereas an MIO holds antithetical values.

The MIO casus of Sanquin showed that audiences perceive communications from both identities but the exposure to the ideological identity through the organization’s behavior and communications is stronger than the utilitarian identity conveyance. The media use characteristics from both identities in their portrayal and sometimes tend to magnify the inherent tensions between the value-driven identities. This seems to be due to their role perception as a “watchdog” of society and the necessity to write newsworthy articles for their demanding readership. The media and other stakeholders judge the multiple identity organization’s actions within the framework of the ideological identity, also if these actions could be seen in the perspective of the business-like domain the organization inhabits as well. The persistent character of the media criticism suggests that “conversations out there” were not recognized by the organization, although they should have been picked up (Zerfass et al., Citation2018, p. 499) and must be acknowledged in the future.

Conclusions

The theoretical considerations as well as the empirical results of this study illustrate the intractable character of an MIO. The multi-method approach allowed us to confirm the qualitative insights on the complexities of an MIO with quantitative data. The model we introduced in the theory section () showed the interrelations between the organization’s identities, the stakeholders’ perception of an MIO, and the stakeholders’ reputation and legitimacy judgments. Our model is by and large confirmed by our case study, but nuance is also added. The most important distinction is the identity multiplicity’s impact on stakeholders’ legitimacy statements rather than on their reputation judgments.

The other nuance is the proportionality of the two identities in the two identity boxes. The model suggests equal sizes, but in reality, the exposure to the ideological identity substantially exceeds the utilitarian identity, especially in the projected identity. The systematic underexposure of the utilitarian identity of an MIO appeared not to be beneficial for stakeholders’ legitimacy judgments. It is perceived as “shadowy” by stakeholders, who urge MIOs in general, including Sanquin, to be transparent about both their ideological and their utilitarian identity, an important demand for the organization’s strategic communication. This might help to interpret and judge the organization’s communications and actions within the right paradigm. For the media communication from the utilitarian domain could come as a surprise. “Surprise” as an important news factor (Boukes & Vliegenthart, Citation2020) generates media coverage that is rather negative than positive in the context of organizational multiple identity. The Holiday Inn slogan “The best surprise is no surprise” would be a useful mantra here (Holiday Inn, Citation1975). An MIO’s (e.g., Sanquin) position as an oracle for its “owned” domain (e.g., blood and blood supply themes) could be capitalized on better in its strategic communication by an equilibrated identity projection.

Generalizations, limitations, and future research

The empirical part of this study draws on a single case. Sanquin is an exemplary case. Our qualitative investigation is theoretically informed and allows analytical generalization (Yin, Citation2013). Many of our findings are likely to be valid for similar organizations. Future studies could focus on another MIO serving as a casus.

Since much of the findings are related to the interpretation of value systems by general audiences and stakeholders and by the role perception of journalists, we acknowledge that for generalizability beyond Western European countries, with comparable social values systems and journalistic mores, more case studies situated in another hemisphere need to be done. Another avenue for future research would be to expand the focus beyond non-profits and public and semipublic organizations. Social pressure has grown on commercial companies to not only exercise their profit-generating activities but also take their social responsibility (Bian et al., Citation2021). This would garnish their utilitarian identity with an ideological identity. Would the same mechanisms and vulnerabilities occur as identified here for the “traditional” MIOs?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 “Sanquin is responsible for safe and efficient blood supply in the Netherlands on a not-for-profit basis. Sanquin also develops and produces pharmaceutical products, conducts high-quality scientific research, and develops and performs a multitude of diagnostic services (Sanquin, n.d.).”

2 Wæraas (Citation2008) studied this for public organizations.

3 The Ethics Review Board of the University approved the research project. The interviewees signed an informed consent form and were provided with the university’s Ethics Review Board address.

4 TNS NIPO is a large and well thought-of research bureau, now rebranded as Kantar TNS

5 A TRI*M index between 45 and 70 is considered to indicate a strong reputation.

References

- Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior, 7, 263–295.

- Argenti, P. A. (2013). Corporate communication (6. ed. ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Barnett, M., Jermier, J., & Lafferrty, B. (2006). Corporate reputation: The definitional landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 9(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550012

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Belasen, A. T. (2008). The theory and practice of corporate communication: A competing values perspective. SAGE.

- Bian, J., Liao, Y., Wang, Y., & Tao, F. (2021). Analysis of firm CSR strategies. European Journal of Operational Research, 290(3), 914–926. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2020.03.046

- Bitektine, A. (2011). Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 151–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0382

- Blessing, A. (2015). Public, private, or in-between? the legitimacy of social enterprises in the housing market. Voluntas (Manchester, England), 26(1), 198–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-013-9422-1

- Boukes, M., & Vliegenthart, R. (2020). A general pattern in the construction of economic newsworthiness? Analyzing news factors in popular, quality, regional, and financial newspapers. Journalism, 21(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725989

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE.

- Carroll, C. E., & McCombs, M. (2003). Agenda-setting effects of business news on the public’s images and opinions about major corporations. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540188

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. L. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. SAGE.

- Cornelissen, J. P., & Elving, W. J. L. (2003). Managing corporate identity: An integrative framework of dimensions and determinants. Corporate Communications, 8(2), 114–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/1356328031047553

- Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00075-1

- Deephouse, D. L., & Carter, S. M. (2005). An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. Journal of Management Studies, 42(2), 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00499.x

- Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, M. (2008). Legitimacy in organizational institutionalism. The Sage Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism, 49, 77.

- Dutton, J. E., & Dukerich, J. M. (1991). Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 517–554.

- Efting, M. (2011). Boeddonoren dreigen met boycot om loon bestuurders. [Blood donors threaten to boycott for executives’ wages]. De Volkskrant.

- Elsbach, K. D. (2003). Organizational perception management. Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 297–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25007-3

- Fombrun, C. J., Ponzi, L. J., & Newburry, W. (2015). Stakeholder tracking and analysis: The RepTrak® system for measuring corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 18(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2014.21

- Foreman, P., & Whetten, D. A. (2002). Members’ identification with multiple-identity organizations. Organization Science, 13(6), 618–635. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.6.618.493

- Foreman, P. O., Whetten, D. A., & Mackey, A. (2012). An identity-based view of reputation, image, and legitimacy: Clarifications and distinctions among related constructs. In T. Pollock, & M. Barnett (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate reputation (pp. 179–200). Oxford University Press.

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2015). Organizations, stakeholders, and intermediaries: Towards a general theory. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 9(4), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2015.1064125

- Frandsen, F., & Johansen, W. (2019). Crisis communication and organizational legitimacy. In J. Rendtorff (Ed.), Handbook of business legitimacy (pp. 1–20). Springer Cham.

- Frederik, J., Medendorp, H., & Jonkers, A. (2021). Zo hadden we het niet bedoeld: De tragedie achter de toeslagenaffaire [We didn’t mean it like that: The tragedy behind the Social Security Supplements mess (2021st ed.). De Correspondent.

- Fredriksson, M., Schillemans, T., & Pallas, J. (2015). Determinants of organizational mediatization: An analysis of the adaptation of Swedish government agencies to news media. Public Administration, 93(4), 1049–1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12184

- Freeman, R. E. (2015). Stakeholder theory. Wiley Encyclopaedia of Management, (1), 1–6.

- Friedman Andrew, L., & Miles, S. (2006). Stakeholders. theory and practice (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Geurtsen, A. (2014). Accountability standards and legitimacy of not-for-profit organizations in the Netherlands. International Review of Public Administration, 19(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/12294659.2014.912451

- Gibson, K. (2000). The moral basis of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006110106408

- Gibson, D., Gonzales, J. L., & Castanon, J. (2006). The importance of reputation and the role of public relations. Public Relations Quarterly, 51(3), 15–18.

- Gioia, D. A., Patvardhan, S. D., Hamilton, A. L., & Corley, K. G. (2013). Organizational identity formation and change. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 123–192. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.762225

- Glynn, M. A. (2000). When cymbals become symbols: Conflict over organizational identity within a symphony orchestra. Organization Science, 11(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.11.3.285.12496

- Golden-Biddle, K., & Locke, K. (2007). Composing qualitative research (Second Edition ed.). Sage Publications.

- Heckert, R. (2019). Challenges for a multiple identity organization: A case study of the Dutch blood supply foundation. Corporate Reputation Review, 22(3), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-019-00065-1

- Heckert, R., Boumans, J., & Vliegenthart, R. (2020). How to nail the multiple identities of an organization? a content analysis of projected identity. Voluntas (Manchester, 31(1), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00157-w

- Heckert, R., Boumans, J., & Vliegenthart, R. (2021). How do media portray multiple identity organizations?. International Journal of Communication (Online), 15, 22.

- Holtz-Bacha, C., & Strömbäck, J. (2012). Opinion polls and the media: Reflecting and shaping public opinion. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Inn, H. (1975). Holiday inn ‘Surprise!’ commercial. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiR5HrmKTyAhVNm6QKHdg0CdQQtwJ6BAgCEAM&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DWNh5uY1ePcA&usg=AOvVaw1LI2Jw4t0klTV2MDuLTwJ9

- Jacobs, S., & Schillemans, T. (2016). Media and public accountability: Typology and exploration. Policy & Politics, 44(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14431855320366

- Jonkman, J. G., Boukes, M., Vliegenthart, R., & Verhoeven, P. (2020). Buffering negative news: Individual-level effects of company visibility, tone, and pre-existing attitudes on corporate reputation. Mass Communication and Society, 23(2), 272–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2019.1694155

- Kessel, M. (2014). Restoring the pharmaceutical industry’s reputation. Nature Biotechnology, 32(10), 983–990. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3036

- Koolma, H. M. (2011). The rise and fall of credibility. Paper presented at the NIG Working Conference, Amsterdam.

- Koopmans, R., & Muis, J. (2009). The rise of right-wing populist Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands: A discursive opportunity approach. European Journal of Political Research, 48(5), 642–664. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2009.00846.x

- Luoma-Aho, V. (2007). Neutral reputation and public sector organizations. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(2), 124. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550043

- Luoma-Aho, V., Olkkonen, L., & Lähteenmäki, M. (2013). Expectation management for public sector organizations. Public Relations Review, 39(3), 248–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2013.02.006

- McCombs, M. E. (2014). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Polity Press.

- Miles, S. (2012). Stakeholder: Essentially contested or just confused?. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(3), 285–298.

- Murphy, P. (2014). Contextual distortion: Strategic communication versus the networked nature of nearly everything. In D. Holtzhausen, & A. Zerfass (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of strategic communication (pp. 137–150). Routledge.

- O’Gorman, S., & Pirner, P. (2006). Measuring and monitoring stakeholder relationships: Using TRI* M as an innovative tool for corporate communication. In Customising stakeholder management strategies (pp. 89–100). Springer.

- Omroep Brabant. (2014). Belgenbloed kopen zou Amphia ziekenhuis Breda miljoen euro per jaar besparen [Bying Belgian blood would save a million euros a year for Amphia hospital Breda]. https://www.omroepbrabant.nl/nieuws/1860001/belgenbloed-kopen-zou-amphia-ziekenhuis-breda-miljoen-euro-per-jaar-besparen

- Overton-de Klerk, N., & Verwey, S. (2013). Towards an emerging paradigm of strategic communication: Core driving forces. Communicatio, 39(3), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500167.2013.837626

- Pratt, M. G., & Foreman, P. O. (2000). Classifying managerial responses to multiple organizational identities. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 18–42. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791601

- Price, K. N., Gioia, D. A., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Reconciling scattered images: Managing disparate organizational expressions and impressions. Journal of Management Inquiry, 17(3), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492608314991

- Remmers, F. (2012). Hoogleraar zet vraagtekens bij voortdurende prijsstijgingen [Professor questions continuous price raises]. Brabants Dagblad.

- Rengers, M., & De Vrieze, J. (2014, 2014, November 14). Verovering van Amerika is bloedstollend voor Sanquin. [Conquering America is blood-curdling for Sanquin] . De Volkskrant.

- Rindova, V. P. (1997). Part VII: Managing reputation: Pursuing everyday excellence: The image cascade and the formation of corporate reputations. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(2), 188–194.

- Rindova, V. P., Pollock, T. G., & Hayward, M. L. A. (2006). Celebrity firms: The social construction of market popularity. Amr, 31(1), 50–71. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379624

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Schultz, M., Hatch, M. J., & Holten Larsen, M. (2009). The expressive organization linking identity, reputation, and the corporate brand. Oxford University Press, http://www.myilibrary.com?id=81949;

- Sillince, J. A., & Brown, A. D. (2009). Multiple organizational identities and legitimacy: The rhetoric of police websites. Human Relations, 62(12), 1829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709336626

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1992). Master frames and cycles of protest. Frontiers in Social Movement Theory, 133, 155.

- Soderlund, M. (2007). The role of news media in shaping and transforming the public perception of Mexican immigration and the laws involved. Law & Psychol.Rev, 31, 167.

- Sondervan, E. (2008). The TRI* M principle-applying it in the public sector. In M. Huber, & S. O’Gorman (Eds.), From customer retention to a holistic stakeholder management system (pp. 31–49). Springer.

- Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610. https://doi.org/10.2307/258788

- Taylor, S., & Littleton, K. (2008). Artwork or money: Conflicts in the construction of a creative identity. Sociological Review, 56(2), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00788.x

- TNS NIPO. (2014). Sanquin op koers voor 2016? Unpublished manuscript.

- True Research. (2014). Onderzoek mogelijke positionering Sanquin. Unpublished manuscript.

- Vaessen, T. (2018a). Alarmfase 1 bij farmaconcern van Sanquin: De FDA komt langs. [Level 1 alert at Sanquin’s pharma: The FDA comes over]. Financieele Dagblad.

- Vaessen, T. (2018b). Monopolie sanquin roept opnieuw vragen op. [Sanquin’s monopoly raises questions again]. Financieele Dagblad.

- Van Den Bogaerd, M., & Aerts, W. (2015). Does media reputation affect properties of accounts payable? European Management Journal, 33(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.05.002

- Van Mersbergen, S. (2011). Top van Sanquin krijgt meer. [Sanquin’s top gets more]. Stentor.

- Veenhof, H. (2009). Geven is nuttig, mar de lol is er af. [Donating is useful, but no fun any longer]. Nederlands Dagblad.

- Volkskrant, D. (2008). Het rode goud. [The red gold]. Volkskrant.

- Wæraas, A. (2008). Can public sector organizations be coherent corporate brands? Marketing Theory, 8(2), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593108093325

- Wæraas, A., & Byrkjeflot, H. (2012). Public sector organizations and reputation management: Five problems. International Public Management Journal, 15(2), 186–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2012.702590

- Yang, A., & Bentley, J. (2017). A balance theory approach to stakeholder network and apology strategy. Public Relations Review, 43(2), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2017.02.012

- Yin, R. K. (2013). Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation, 19(3), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013497081

- Zeithaml, V. A., & Bitner, M. J. (2003). Services marketing: Integrating customer focus across the firm (3rd). McGraw-Hill/Irwin. Retrieved from Table of contents. http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/toc/mh021/2002025544.html;

- Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485

Appendices

Stakeholders (interviewees)

S1Executive Health Council of the Netherlands (Gezondheidsraad)

S2Member of Parliament, Netherlands, socialist

S3Member of Parliament, Netherlands, liberal

S4Professor Philosophy, Wageningen University and Research

Member Health Council of the Netherlands

Promotor Sanquin PhD

Chairperson Unilever Central Research Ethics Advisory Group

S5Managing Director Hospital Group

S6Associate Director large pharmaceutical enterprise

S7Media expert

S8Executive Director Medicines Evaluation Board (CBG), Netherlands

Former executive Pharmaceutical Affairs and Medical Technology, Ministry of Health (VWS), Netherlands

S9Blood donor, long experience

S10Blood donor, short experience

Appendix 2

Journalists (interviewees)