ABSTRACT

This article analyses some socio-communicative aspects and implications of the hashtagged movement Fridays For Future on Twitter, which has a capacity for mobilization that extends beyond that of any previous non-governmental organization (NGO). It considers how the movement is organised and also the strategic communication dimension of Twitter activists as key agents. We also explore how social-communicative actions shape the public debate to bring about social change. We analysed a sample of tweets containing the hashtags #fridaysforfuture, #climatestrike and #schoolstrike4climate posted over 5 non-consecutive weeks between January-June 2021. Quantitative, network and qualitative analyses revealed descriptive, network and attribute results indicating ongoing intensive discourse and social interactions. The patterns reflect strategic behaviour that reproduces orderly (dis)organisation, as the interaction around hashtags and action-participation are evidence of strategic communication within a fluid and disruptive organisational form.

Introduction

The excitement around online enabled or enhanced social movements has given rise to a growing body of literature about protests and public mobilizations (Earl & Kimport, Citation2009). Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have inspired many of the emerging social movements and much of the activism. This is because they are the epitome of agents having a role in social communication through the civic exercise of pursuing and seeking the common good and civic relations in the public sphere (Oliveira, Citation2019). The activity of NGOs in the public sphere can also be considered strategic communication, and can be regarded as crucial strategic conversations (Zerfass et al., Citation2018). These micro level conversations influence the meso level and also have visible macro level implications and online components. This article identifies the interplay between meso and macro levels of analysis and discusses the conceptual interdependencies between them. It also draws attention to communication activity within new organisational forms.

Civic activity – beyond NGOs – diverts decision-making away from institutionalised democratic systems and challenges the notion of the public sphere (Brantner et al., Citation2021). Amidst the new entanglement between the institutional systems of democratic states, platformised social media and these social movements, hashtagged actions crystallise social media activity into forms of street action that eventually provoke parliamentary action. Examples of citizen-led communicative activities that have generated a global response include #BlackLivesMatter or #MeToo. This is also the case of the #Fridaysforfuture movement.

The main purpose of this article is to understand the role of the stakeholders that participate in strategic communication (Holtzhausen & Zerfass, Citation2015). It investigates the organisational and socio-communicative features of #Fridaysforfuture, which emerged in 2015 as a result of citizen activity on social media (Twitter) (Fridays For Future, Citationn.d.). It also explores whether these features are strategic communication performed by activists, and if the latter are central agents (Holtzhausen, Citation2008) within the movement’s communications entourage. This involved examining the extent to which stakeholders have multifaceted roles as initiators, drivers and ambassadors or reproducers who manage, activate or communicate; and how the networks of interaction and organisation contribute to the public communication process.

Social media, and Twitter in particular, have historically been regarded as a “platform for protest and a vehicle for voice” and street action (Smith et al., Citation2019, p. 182). Early examples of this extend from the so-called “Arab Spring uprisings” (in late 2010), to #OccupyWallStreet in 2011 (Adi & Moloney, Citation2012), Spanish “Rodea el Congreso” (see, for example, Brantner & Rodríguez-Amat, Citation2016) in 2012, and in 2013, to Turkish activists at the Taksim Square protests who graffitied that “the revolution will not be televised, it will be tweeted” (Tas & Tas, Citation2014). These cases shared impressions about the strategic role of Twitter in enhancing public debates, reconfiguring complex communicative spaces, facilitating media access, and magnifying their strategic socio-communicative dimension through optimised messaging that reaches wider audiences in a shorter time (Gutiérrez-Rubí, Citation2021, pp. 55–56).

Twitter activity within communication for social change can also be researched from a strategic communication perspective. Previous works have explored how social actors and movements use Twitter as a strategic communication tool to grow organisational activism (Ali et al., Citation2022), organise political activists and protest movements, promote transnational debates on issues of social interest (Ferra & Nguyen, Citation2017), or to channel protest efforts into the online sphere (Smith et al., Citation2019). Twitter is seen to facilitate discussion, political engagement, and knowledgeability (Lynn et al., Citation2020) as well as giving non-traditional actors a voice in socio-political debates.

The digital, entangled, politicised, and often polarised online conversational space poses intellectual challenges to the normative vision of the public sphere. This suggests the need for new research examining how smartphones enable access to digital platforms, or how interactions between users and the space generate new conversations. Inevitably, these new spatial constellations multiply the public conversation – which has more participants, listeners, and replies than ever before – and extend it across space and geographies.

Similarly to Branter et al. (Citation2021), this article builds on an understanding of the public sphere a) as a space of (inter)action, b) as a space for integrating new technologies and issues, and c) as a process that rethinks the very conditions of legitimacy. This research addresses these complexities by specifically focusing on Twitter as an ecosystem and as a communicative space in its own right.

The theoretical background of the article draws on four axioms. Each axiom defines a field that guides the literature review and is then applied to the case of Fridays for future. The four axioms are:

- Axiom 1. Strategic communication as conversations of strategic significance;

- Axiom 2. Activism is a global-local conversation with organisational communication patterns;

- Axiom 3. The public sphere is an assemblage that forms an interface for public interaction;

- Axiom 4. Collective actors, communication and organisation: hashtag movements are, perform, and do through their conversational activity.

Based on a literature review that informs the theoretical background, we present the research questions and methodology. The main findings are then shared, followed by a discussion and the conclusion.

Theoretical background

Strategic communication as conversations of strategic significance (axiom 1)

The original definition of strategic communication stresses the proactive and control dimensions of the process. It was instrumental and organisation-centred as it was largely oriented towards the planned managerial intention of the mission (Hallahan et al., Citation2007). The notion was subsequently expanded and linked more closely to the notion of legitimacy by extending to the concept of the public sphere (Holtzhausen & Zerfass, Citation2015). Some authors insist on considering strategic communication to be all the communication acts by any member of an organisation. Winkler and Etter (Citation2018) see the sensemaking process from an organisation’s emergence – how members ‘talk’ organisations into being – as being no different to the act of organising. Other aspects relate to organisational complexity (Heide et al., Citation2018) or even civic relations – acts that seek the common good (Oliveira, Citation2019). In this sense, Zerfass et al. (Citation2018) suggest that strategic communication should be considered as “all the communication that is substantial for the survival and sustained success of an entity” and “the purposeful use of communication by an organisation or other entity to engage in conversations of strategic significance to its goals” (p. 493).

If those early notions of structure-centred understandings of strategic communication were applied to disruptive and fluid activism (such as hashtag movements), the organisational forms of the movement would dissolve once their previously established goals are achieved. However, these movements are constituted through their own socio-communicative process. Their survival does not therefore depend on achieving the goals but on ensuring these internal flows of communication, which create the organisation in a non-linear, ongoing process.

The post-modern approach and the notion of arenas of meaning fit this disruptive fluid activism. The “agile management process” (van Ruler, Citation2018) is not controlled or planned, but rather framed by the mission and the impulse of the “continuous loop” of negotiated meanings. This also includes the use of ritual and rhetoric discursive artefacts in the arenas. Conversations that trigger citizen engagement follow a complex process that connects the strategic dimension of the shared goals with the creation of organisations as collective actors. This means that analysing their interactions and conversations can therefore reveal some features of their strategic communication and the changes and continuities in the roles and positions of communicative actors and stakeholders between an operative and a strategic dimension. An expanded sociological discourse analysis model developed by Ruiz Ruiz (Citation2009) and adapted to strategic communication, can be used to identify these features and it informs the attribute analysis described in the methodology section. This type of analytical model is part of an attempt to respond to the call by Zerfass et al. (Citation2018) to get “back in the game” by identifying robust methods with a distinct academic perspective, but that are rooted in communication theory (van Ruler, Citation2018). In this case, discourse analysis of Twitter conversations helps to connect the content of the communication with its performative dimension by establishing three levels of analysis that we can then apply to the interactions. The three levels focus on utterances, enunciation, and socio-communicative features and are used to examine the contents of the Twitter conversation in terms of features of strategic communication. This research will therefore contribute to understanding the transformation of the nature of the public debate that generates an overspilled public sphere (see Belinskaya, Citation2021).

Activism is a global-local conversation with organizational communication patterns (axiom 2)

The Internet burst onto what appeared to be a global public sphere (Candón-Mena, Citation2011). It connected individual and collective synergies, facilitated the creation of ties of solidarity, and raised awareness of specific issues. The Internet provides “a form of action or organisation” (Luengo, Citation2010) and is a form of social mediation (Robles & Zambrano, Citation2011) and ‘organisational hybridity’ (Chadwick & Chadwick, Citation2007). Researchers reacted enthusiastically to Castells (Citation2000) premonitory vision of the Internet as enabling citizen activism in response to the crisis of traditional structured organisations (political parties, unions, and associations). It also increasingly fostered online shared cultures to articulate social movements and new dialogues between local action and global values. These three pillars – crisis, online culture, and global-local dialogues — seem to link the forms of activism enhanced by social media. Their outcome can be seen in these new forms of movement and they are materialised throughout the above pillars that connect them. The agenda setting of the crisis is propagated in the media, followed by online cultures and global-local dialogues. The last stand for global issues are local groups that also become the hybrid arm of the movement: they self-organise actions on local streets that are aligned with the global movement.

The response to the crisis of traditional structures involves the citizenry and their civic relations (Oliveira, Citation2019). The civic communicative exercise aims to identify a common good that becomes the shared objective. After identifying that common good, the citizenry organises, shapes and supports the development of strategies and tactics. In these forms of ‘activist PR’, public relations become a “persuasive tool for strengthening democracy” (Moloney et al., Citation2013, p. 5). This concept of activist PR can be divided into two subcategories: ‘dissent PR’ and ‘protest PR’. Adi (Citation2018) describes these: “the first (dissent) is punctual, emotional and the second (protest) more strategic and long term (…) with die-ins, sit-ins, occupations, strikes, marches, rallies more likely to be attributed to protest PR, and discussions, fairs, books, debates to dissent PR” (pp. 8–9).

The second pillar, online activism, emerges under multiple names, from generic cyberactivism to pejorative slacktivism (Smith et al., Citation2019). Online activism can be referred as “any strategy that seeks to change the public agenda, the inclusion of a new topic on the agenda of the great social discussion, by disseminating a certain message and spreading it through word of mouth multiplied by the media and personal electronic publication” (Ugarte, Citation2007, p. 85). Criticism of online activism tends to refer to low-profile participation in social media protests in which supporters “confine their outrage to the computer screen” (Bastos et al., Citation2015, p. 322).

The third pillar – global dialogue — materialises in the hashtag movements. The global dynamics of social interaction can be seen as disruptive organisational forms (Fishman & Everson, Citation2016). There is no formal structure or coordination, but they do have a steady impact on the public agenda and seem to aim at (and reach) strategic goals. Global hashtag movements combine hybrid activity: street action with online resources and ad-hoc leaders who manage and coordinate the cells. The global conversation mostly takes place online and uses operational communication management reduced to spontaneous interventions by random citizens. These conversations – discourse-producing exchanges between citizens of messages related to the subject – generate communicative patterns that have an organisational but also a social and political impact. Research into internet cultures and online communities that has explored recent cases such as the #metoo movements (Lindgren, Citation2019) or #blacklivesmatter (Zulli, Citation2020) has also examined these conversations. This raises the question as to whether they are global activist movements or just a cumulative assemblage of single sporadic acts, such as the ad hoc publics around hashtagged cases (Bruns & Burgess, Citation2015).

The public sphere is an assemblage that forms an interface for public interaction (axiom 3)

The concept of the public sphere (Öffentlichkeit), coined by Arendt (Citation1951) and appropriated by Habermas et al. (Citation1974), was defined as “a sphere of our social life in which something like public opinion can be formed. Access is guaranteed to all citizens’’ (Habermas, p. 49). Such “undistorted communication” is (idealised) as being independent of any corporate digital platform and state bureaucratic bodies. This concept has been criticised for its disregard of class distinctions (Negt & Kluge, Citation1973), its rather bourgeois-centred understanding (Garnham, Citation2007), and its disregard of diversity and multiculturalism (Walzer, Citation1999), race (Jacobs, Citation1999) and gender (Fraser, Citation1996). Furthermore, in Castells (Citation2008) questioned the difficulties faced by nation-state public spheres, arguing that new technologies would allow for better civil society organisations. He seemed to ignore the fact that the economic independence of the digital public sphere and the commercialisation of cyberspace have been criticised for 20 years (Sparks, Citation2001; Thomas & Wyatt, Citation1999). Following Habermas (Citation2006), Geiger (Citation2009) argued that computer-mediated communication played “a ‘parasitic’ role in the public sphere, largely because Internet-based discourse communities had fragmented audiences’’ (p. 2). Segmented stakeholders and excessive amounts of information produce “echo chambers” (Colleoni et al., Citation2014) and facilitate the dark side of digital politics (Treré, Citation2016).

The concept of the echo chamber was originally used by Lazarsfeld in political communication research into the concept of ‘selective exposure’. “This refers to a phenomenon whereby people filter out content that challenges their beliefs in favour of information they agree with, resulting in an ‘echo chamber’ effect” (Lazarsfeld et al., Citation1944); see also Haw (Citation2020, p. 40). Because political systems assume that citizens are informed and consider about their opinion, echo chambers are seen as threats to democracy.

Collective actors, communication, and organisation: hashtag movements are, perform, and do through their conversational activity (axiom 4)

Discussion in the public sphere still requires agency and actors who consider the issues. Hashtag movements –– however fluid, spontaneous and disruptive –– are organisational forms or agents that intervene in the public sphere. Giddens’ structuration theory (Citation1984) and its adaptation to NGOs helps us understand these entities and their organisational features (or absence thereof) by bringing agency to the fore. Giddens resolved the gap between structure and action by enabling links between the micro and macro levels. McPhee and Zaug (Citation2000) followed this with the four-flows model, which includes: 1) membership negotiation, 2) self-structuring, 3) institutional positioning, 4) and activity coordination. This helps to define the agency role of hashtag organisations in terms of their triple roles of acting, being, and doing.

Indeed, conversations in the public sphere (online or offline) acquire a performative capacity to become forms of ‘acting’. This aligns with Putnam and Nicotera’s (Citation2009) Communication Constitutes Organisation (CCO) Perspective. These performative conversations also enable hashtag movements as organisations to find their own positions and to consolidate a shared identity or form of “being” (Oliveira, Citation2019) that is both a practice and an outcome. The reason for this is the lack of formal structures or organisational shareholders. This blurs the boundaries between internal and external communication, and between the meso and macro levels, substantiating the conversational practice into organisational patterns. Finally, coordinated global engagement in social media across multiple languages and cultures reveals a collective reflective effort by citizens to organise around clusters that extend their socio-political need to belong to a community, even if only through responding online. This is where hashtag movements also become forms of self-identity. By “doing” they overcome any sense of fragmentation and dispersion and become “communities of social integration and perform reflexive self-regulation of the system” (Oliveira, Citation2019, p. 97).

This triple process of acting, being, and doing helps to explain how hashtag movements intervene in the public sphere as conversational agents. Their activity constitutes an identity (being), is performative (acting) and responds to the participants’ need to engage in the political process (doing).

Fridays for Future (FFF): a case study

#FridaysforFuture is a hashtag movement (Haßler et al., Citation2021). It is an organised global climate movement that started in August 2018 when 15-year-old Greta Thunberg began a school strike for climate change. She sat outside the Swedish Parliament every school day to demand urgent action on the climate crisis. She sparked an international movement with students and activists protesting outside local parliaments and city halls. The main activity is online communication and demonstrations that exert pressure on policymakers and force them to listen to scientists in order to reduce global warming and find solutions for climate change. This movement is articulated as an ongoing online conversation and calls-to-action through local strikes. In March 2019, Fridays for Future mobilised 1.6 million people (Wahlström et al., Citation2019).

The movement’s main online site (Fridays For Future, Citationn.d..) geolocates all the strikes in a ‘Map of actions’ that is filled in collaboratively as a form of archival crowdmapping (see Brantner & Rodríguez-Amat, Citation2016). The strategy behind this geolocation reporting is to show the results of civil society organising and that “activism works”. The ‘What we do’ tab is where the movement presents who they are and what their demands are, as well as the outcome of their climate strikes (strike statistics). They also seek to bring the movement’s discourse closer to the digital community with a section on ‘activist speeches’. Here, not only Greta Thunberg’s interventions are shared, but also those of other FFF activists and leaders (including Hilda Flavia Nakabuye, Kallan Benson, and Theo Cullen-Mouze).

The phenomenon of FFF as a global actor has recently begun to be researched from the point of view of its communication activity (Marquardt, Citation2020). But this is only one incipient strand of research. The focus are representation and coverage in news articles, official documents, and speech analysis, complemented by qualitative interviews with the movement’s youth representatives in Germany (Marquardt, Citation2020). In this article we examine the socio-communicative aspects visible on Twitter that reflect the axioms mentioned above (Axiom 1 - strategic communication; Axiom 2 - activism; Axiom 3 - the public sphere, and Axiom 4 - collective actors, communication and organisation). The empirical work is guided by following research questions:

RQ1:

Who are the main stakeholders/actors involved in the communicative process? (A2, A3)

RQ2:

What (if any) are the communication patterns of FFF (during any given week) on Twitter? (A1,A2, A3, A4)

RQ3:

To what extent is this activity (dis)organised? Is there strategic communication? (A1, A3)

RQ4:

Does this (dis)organisation enable inferences about the democratic nature of the activity of FFF? (A2, A3)

Methodology

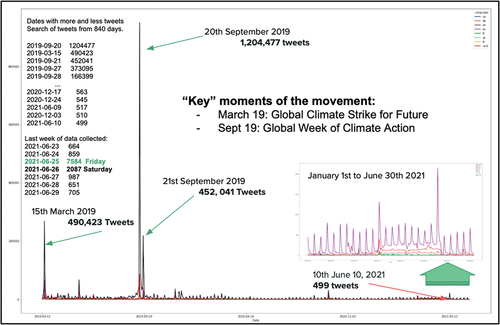

We began the research by using a script adapted from Padilla Molina (Citation2020) to collect 8.4 million tweets posted between March 2019 and June 2021 containing the hashtags #fridaysforfuture, #climatestrike and #schoolstrike4climate (). The project follows the ethical guidelines of AoIR (Franzke et al., Citation2020) and prioritises the protection of the subjects and their work.

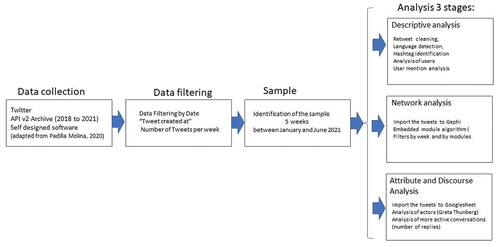

The timeline shows that the distribution of Twitter activity in the early batch (see ) was lower during the first half of 2021, though clearly still peaking on Fridays. We considered a sample of 84,652 tweets (including retweets) distributed over 5 non-consecutive weeks with similar low engagement between January and June 2021 (see Appendix 1). The sample was obtained by comparing the number of tweets (and retweets) posted weekly in 2021, but no other filters were applied at this stage. The criteria for the sampling assumed that any organisational composition (active, passive or silent) would be easier to identify in periods with less Twitter activity. The data was analysed in three independent stages ():

Descriptive analysis: mostly quantitative, to explore the sample and identify patterns of activity to understand the global-local community dynamics.

Network analysis: the findings show the filtering (by date and module) applied to the calculations and analysis done on Gephi. This helped us explore the relational dispersion of user-hashtag tweets and user-mention tweets. Similarly to the work by Himelboim et al. (Citation2017), the modularity of the hashtag networks helped us to identify communities of nodes as clusters of meaning and central and peripheral hashtags.

Attribute and discourse analysis: performed manually after importing the data into a shared spreadsheet. This made it possible to analyse the actors and identify more active conversations (number of replies equal or higher than 40) so as to analyse the discursive patterns of interactions. A total of 34 conversations (8 in sample week (SW) 1, 15 in SW2, 5 in SW3, 2 in SW4, and 4 in SW5) made up the final corpus for the attribute analysis. These conversations included 5413 interventions (replies) and 202,515 interactions (replies, retweets, and likes).

The attribute analysis of these conversations considered three levels: utterance (what is said), enunciation (in what context of interaction it is said), and socio-communicative features (what does the saying do), adapted from Ruiz Ruiz (Citation2009) (see for levels and procedures of analysis). The validity and rigour of the human interpretive processes was ensured by a double operation of reliability and intersubjectivity.

Table 1. Summary of the levels and procedures of analysis.

Findings

Descriptive analysis

Most of the 84,652 tweets sampled were retweets. The cleaning process resulted in 11,264 original tweets posted by 3837 unique users. Their weekly publication pattern clearly shows the Friday peaks, and the sample from March indicates the most activity. This is likely due to its coinciding with the Global FFF Strike (25 March). Nevertheless, the number of tweets on that Friday was lower than on previous Fridays. January 2021 coincided with the start of the online Friday strikes action with hashtag #ClimateStrikeOnline (see Appendix 1).

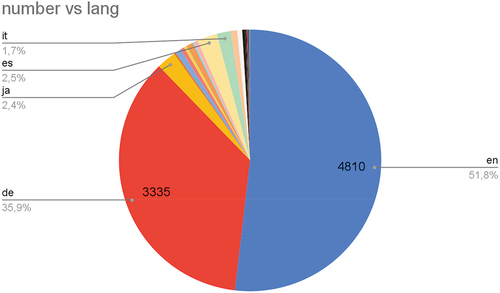

Of all the tweets collected, 2184 were not associated with a specific language. However, the rest included 4810 tweets in English (en) and 3335 in German (de). These two “languages” represent 90% of the tweets (see Appendix 1).

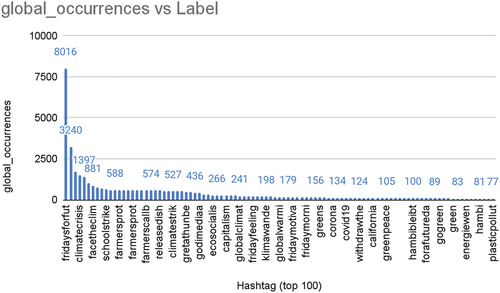

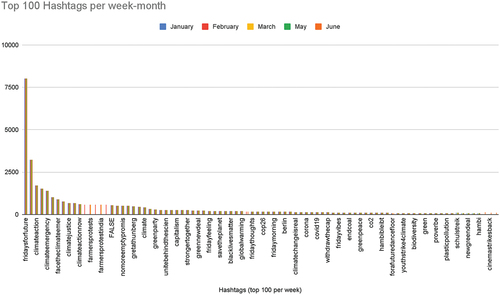

Analysis of the hashtags shows that the 11,264 tweets contained 8183 different hashtags, of which only 707 appeared on more than 10 occasions. This was later filtered further to identify the 100 most popular hashtags overall and by week to show that the main hashtags remained at the top, and there was very little variation across the weeks (see Appendix 1).

The top 5 hashtags used are #Fridaysforfuture (8016 occurrences), #climatestrike (3240), #climateaction (1710), #climatecrisis (1527) and #climateemergency (1397). Except for the name of the movement – which was also the search term – the other hashtags address the issue of climate emergency. The terms ‘strike’ and ‘action’ appeal to citizens’ need to respond; and the terms ‘crisis’ and ‘emergency’ stress the urgency of saving the planet. There is also a direct, clear, and urgent commitment to participation among the digital community. A similar situation is observed in the results for the top hashtags per month, which show almost no differences in the top 100 from week to week.

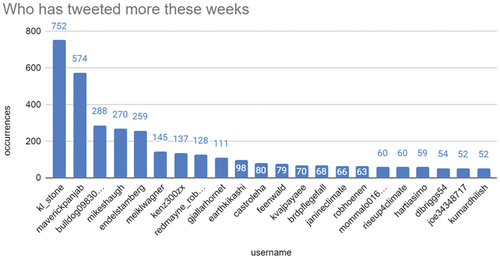

Regarding the users of the FFF community, Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg − 5 million followers) only tweeted 6 times in the five weeks, which shows that the most visible face of the movement had a low profile of activity. She mainly posted about the school strike. The most active Twitter user is a German journalistFootnote1 with 752 tweets. In second place, with 574 tweets, is an Indian activist who posted with a group of relevant hashtags related to strikes, the planet, plastic pollution, and COVID-19 in the context of his country. In third place is an allegedly Hamburg-based anti-climate militant, who displays anti-FFF symbols on their profile, which has very few followers (10). Despite this user’s high level of activity, they have a low significant circle of influence and interactions. The fourth user defines themself as a “London Green Left” climate change activist. At the bottom of the top five is a probably Hamburg-based climate activist who stands for #FightFor1Point5, one of the last FFF statements against political inaction. The German-speaking Twitter community is very active according to the analysis of top users. The data reveals the dynamics of online activism and clearly demonstrates the global-local community dynamics.

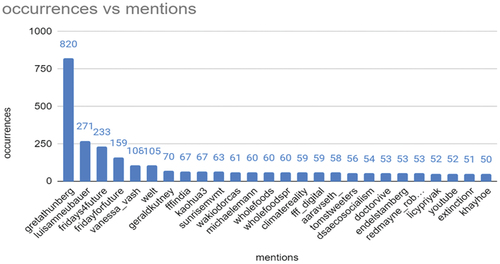

An analysis of the mentions shows that Greta Thunberg was named in 820 tweets during the five weeks (0.96% of the total). Luisa Neubauer (@luisamneubauer − 378 thousand followers) is mentioned 271 times across the five weeks. She is an FFF activist, geography student and writer based in Berlin (Germany). In third and fourth place are different Twitter profiles related to FFF: @fridays4future and @fridaysforfuture. Finally, the fifth most mentioned user is the African climate activist Vanessa Nakate (@Vanessa_vash − 235.9 thousand followers), who is linked to other social movements in Africa (Rise Up Movement @Riseupmovt). The weight of young female activists within the movement is clear from this list as they generate the highest number of interactions and more engagement.

Network analysis

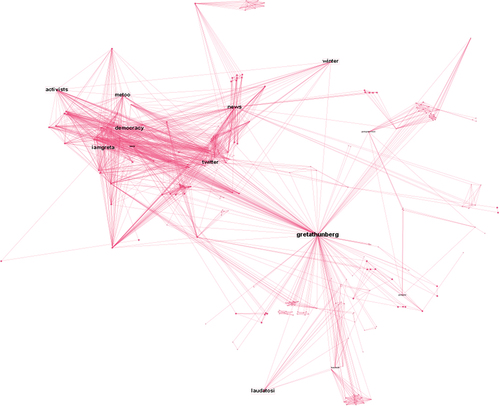

The network built from the connections between hashtags and tweets shows that there is hardly any variation from week to week and that the main modules are similar, with identical patterns across the weeks (see ). These networks are obtained through colouring the most relevant clusters (modules), and by filtering the full network of tweets-hashtags by week-month.

Modules are the result of the statistical operation of modularity, which is a measure of the structure of networks or graphs that detects the strength of the division of a network. Modules are also called groups, clusters, or communities. Networks with high modularity have dense connections between the nodes within modules, but sparse connections between nodes in different modules. In this case, the option was to identify the main and most populated modules. The filtering operations allowed us to show that, while each cloud () is specific and different, the shape of the networks remains very similar. This helps to highlight the strong continuity between independent and non-consecutive weeks.

The hashtags (selecting those with more than 10 iterations) emphasise that continuity and level of cross-week repetition. The most fundamental patterns of hashtag use from week to week are very similar.

The modules that emerge also seem to indicate semantic continuity. This conversation visually represented as a cloud of keywords highlights that the diverse communities share hashtags as forms of identification. displays in colours the network in one week and clusters with more than 10 nodes. The grey networks contain fewer than 200 tweets and show low activity within the communities of discussion.

Figure 4. Module 3b (February) Network (hashtags/users > 10 occurrences with 8183 nodes distributed into 31 modules). Grey modules have fewer than 200 tweets.

The most frequent hashtags are displayed bigger in the network graph. At the centre, slightly to the right, the hashtag #Fridaysforfuture is clearly visible. The breakdown of the main clusters of hashtags are identified and described below ().

Figure 5. Network (hashtags/users > 10 occurrences). 5a. Module 4. 24% (2012 nodes). 5b. Module 14. 16.4% (1343 nodes). 5c. Module 8.14% (1151 nodes).5d. Module 31.8,32% (681 nodes). 5e. Module 11. 4,89% (400 nodes).Climate Strike. Climate Change politics.Fridays for future (only). German climate Twittersphere. Friday (Happy Friday, motivational, etc) Spanish politics and others.

The 5 most prominent modules in the network () can be analysed as conversation clouds. Each of them shows a cluster of hashtags that build a consistent meaning. , in purple, contains a large number of hashtags. The number of nodes in this module represent almost a quarter of the full network (24%). The hashtags in this module relate to political and action content linked to climate change and climate strikes. The second module () contains 16.4% of the nodes and represents the central conversation around the #FridaysforFuture movement. These two clusters of hashtags are already 40.4% of the full network and include the most relevant hashtags (topics) around the movement itself and its political cause. highlights the presence of the German community in the online debate around climate change and includes 14% of the nodes. The weight of the German community in the conversation is noteworthy, as it appears as a community in its own German-climate-Twittersphere. In other languages, such as Spanish, the presence is residual (2.5% of the tweets).

The analysis shows that there is a motivational aspect linked to the semantics of the cause. The network also shows a conversation cloud about #HappyFriday (), an aspect that links FFF to other communities that are not necessarily linked to the environment and climate change but that share users (mainly with the clouds in ). It appears in the graph as something ‘collateral’ to the movement itself and its discourse around ‘Fridays’. An example can be seen in the following tweet (original in German): “Office suit for today … #frivolefriday #FridayFeeling here #FridaysForFuture gets an interesting meaning”.

The conversation around and with Greta Thunberg () is less prominent than one might expect. It shows that she is not the movement itself but is part of FFF and contributes to the conversation, creating a network around the movement itself.

Figure 6. Hashtags about Greta Thunberg and Twitter. Module 5 Network (hashtags/users > 10 occurrences −3,29% 269 nodes).

Considering actor types that interact within these clusters (), the main stakeholders are FFF activists and supporters (34.3%), followed by other social movements (14.3%), such as 350.org, @DemCastUSA and FFF affiliates in other countries. These are followed by the media (11.4%), politicians (8.6%) — such as Justin Trudeau or Elizabeth Warren (US Senator), (8.6%) and the scientific community (5.7%). There is less recurrence (below 5%) of celebrities (e.g. Mark Ruffalo), company CEOs, journalists and communication professionals, unions and NGOs, such as Greenpeace. Many activists have Twitter-verified profiles, which means that they are users who are known in the public sphere (government, news, entertainment), This feature shows the reach and impact of the community.

Attribute analysis

A plurality of voices emerges from the Twitter interactions. The qualitative analysis of these conversations reveals a forum for a multitude of parallel discussions which is similar to any apparently chaotic and disruptive non-moderated assembly.

The topics of conversation also range from FFF issues like strikes, identification, alert, and support, to engagement and meaning of the movement, or to politics and in-depth conversations about climate change. These interactions are stimulated by key messages, images, and videos. There is frequently also content from credible entities, like the Davos World Economic Forum, or established media outlets, as well as underpinned statements, claims, and messages. The topics extend and combine informative content with emotional appeals, but our analysis did not detect an aggressive tone or any threats. The overall style of the conversation gave the impression that freedom of opinion and respect for democratic discussion were never under threat.

The main activity was mostly led by unknown citizen activists. As described in the methodology section, the analysis identified useful conversations showcasing how the first two stages of data analysis (descriptive and network analysis) lead to the third analytical stage: the socio-communicative attributes.

Actors: from Greta Thunberg to Beatrix von Storch

Many actors participate in the movement as stakeholders, i.e., some of them share proposals that contribute to mitigating climate change. Others advocate finding ways of identifying those responsible and making them accountable by taxing them or boycotting their products. Both strategic and operative dimensions coexist here.

Greta Thunberg, as one of the most visible faces of the entire FFF movement, uses Twitter as her main channel. Thunberg’s relatively scarce interventions attract attention but tend to be short messages regarding activism, as well as key information ().

Figure 8. Greta Thunberg Tweet (included in the sample analysis): https://twitter.com/GretaThunberg/status/1398203250394996746.

Greta Thunberg embodies the angry youngster who cannot take it any longer and turns this into motivation for action. Her tweets have an impact on those followers who see them, but are also retweeted and replied to. Most tweets use pictures of her with her handmade poster “Skolstrejk För Klimatet” and the corresponding strike week number, together with different hashtags. She tweets on Fridays.

The sophisticated narrative of her Twitter activity alternates between blame and motivation, often using dry humour: “This is starting to get a bit repetitive…” she states in her 145th strike week. Some of the responses are supportive and applaud the repetitive statements, which underline that seriousness of the problem. One tweet had an infographic warning about the greenhouse effect and global warming. Another tweet uses analogies to illustrate the importance of repetition: “till you get it, like in Karate”. Other tweets encourage the community with positive messages, i.e., that after the lockdown, it will be possible to be on the streets again. These rhetoric artefacts using powerful semiotic elements are normal in conversations. As communication strategies, these messages fulfil constitutive, organisational, and intervention needs.

Greta Thunberg also adopts a messianic role. In one post she shares an interview highlighting the significance of activism for #Fridaysforfuture: “It gives us meaning in life, and meaning in life makes you happy”. Several users point to her as a symbol of activist inspiration and the embodiment of hope. Her style is contagious and can be seen in posts by other prominent local activists who copy her photo, pose, rhetoric and influencing styles. It does not seem to be intentional or managed, but we can point out that the others are local adaptations of her model.

Twitter is a space for disagreement too, and Thunberg’s posts sometimes attract criticism. One user seeks to discredit Greta by questioning her authenticity. Another user associates her messianic tone with the ISIS organisation. Some of the critical stances are more elaborate: one user directly refers to the notion of common goals, and asks when the “success” of the strike will be evident. This user also includes a link to a blog discussion on public and private rights, and their relationship to the success or failure of civilization.

Some of the other actors that participate in the Twitter conversation oppose #Fridaysforfuture. An example is the right wing German politician Beatrix von Storch (AfD), who appropriates a post by @FridaysforFuture on Women’s Day. In a show of democratic values and making an identity claim for the organisation, FFF associated climate justice with feminism: “@FridaysForFuture: Diese Woche gehört diese Account nur Frauen, Inter, nicht-binären, Trans oder Agender Menschen von Fridays for Future, denn der #Weltfrauentag ist auch bei uns feministischer Kampftag! Keine Klimagerechtigkeit ohne Feminismus ✊” (This week this account only belongs to women, inter, non-binary, trans or agender people from Fridays for Future, because #InternationalWomen’sDay is also a feminist day of struggle for us! No climate justice without feminism”). But Beatrix von Storch (AfD) used the post to claim: “They are left-wing extremists. The supposed climate crisis only serves as a cover to collect the naïve rich German citizens. #International Women’s Day”.

However, Twitter is a reactive space and this comment did not go unnoticed. Users discredited the MP’s comments using all sorts of symbols and irony, adding that she is talking nonsense once again and that representing youth as the enemy is a low blow.

Conversations

In one of the most relevant conversations, Mike Hudema, the green economy entrepreneur and public personality (with more than 1 million followers), shares data on the companies that emit the greatest amount of CO2 (in tonnes). It includes the following text: “These 100 companies are responsible for 71% of all CO2 emissions in the world. This is where we need to start. It’s that simple. There is no planet B. There is no time to waste. #ActOnClimate. #ClimateEmergency #ClimateAction #climatecrisis #climatestrike #GreenNewDeal”.Footnote2 The list ranks companies, their base country, and their increase in emissions. Hudema holds these corporations responsible for most of the planet’s emissions and assumes that they are major contributors to global warming.

His tweet is a wake-up call. It places the onus for action on corporate players and increases the sense of urgency by using the pun “no planet B”, as in no alternative (plan B). The tweet ensures its visibility and prominence with a list of relevant hashtags: #ActOnClimate, #ClimateEmergency, #ClimateStrike or #GreenNewDeal, that link it to the FFF movement. The call to action does not mention any actors, but appeals to civil society engagement. This is an example of dissent PR and contributes to FFF generating engagement within the community so that citizens see the need to join and support the movement. The author also performs informative and educational work using data, and his followers disseminate his statements beyond the core community.

Regarding the contextual level of analysis, the interactions emerging from this tweet include several continuations. For instance, users suggest including on the list organisations such as the US army or oil companies, or collateral partners such as personal and agricultural emissions, or finance companies that indirectly fund these polluting corporations. Other users propose solutions including awareness tools, such as a web app to carbohack-track your carbon footprint. Or more corporate-oriented taxation: “make the pollution more expensive than the money they make from it” (several users expressed support for this) or involving the supply chain. Companies like Weare8 also publicly support the post, arguing that companies should assume their responsibilities.

The thread engaged other communities such as the vegan movement, which suggested recording the price of beef. There were some challenging paradoxes, such as questioning how a “waste company” in charge of “recycling” can be so polluting that it is included in this top 100 (other users asked for more data on the subject). The conversation unfolds in multiple ways. For example, when users discuss the role of electric companies, part of the discussion assumes a national dimension, and some people mention country inequalities in infrastructure for renewable energy. The comments call for action, including government regulations and appeal to citizens to act (or to vote), as well as arguing about the usefulness of being a critical consumer.

Climate strikes in schools are a recurring topic. In user interactions, views that are not necessarily favoured are backed using rhetorical strategies. One example is a user who disagrees with demonstrations during school hours and criticises some visible faces of the movement. A reply states that, despite supporting the cause, the person does not agree that students who are not from a wealthy background should stay away from school and mentions the need to take care of the future.

Other conversations are statements of membership and expressions of identity: “today completed 2 years”, followed by a demand “to enact a climate law in the parliament”. The conversation moves on to a discussion of climate justice and expressions of support for activists from the local community: “my thoughts with every Indian climate activist”. It includes a photo with a postcard of the children’s movement for climate change and Greta Thunberg’s serious face with an angry expression.

Another tweet shared another MP’s failed promises: “It’s been almost one year now, Hon’ble MP Mr @ShashiTharoor promised me to bring up my 3 demands in the parliament but he lie [sic] to me. He can’t even fulfil his promises to a 9 years old kid. I trust he will bring it up in this ongoing parliament session. Restore our faith to you!” This tweet tagged the politician and brought him into the conversation by disseminating the discussion. Dissenting voices responded swiftly: “Learn grammar. ’He lie to me‘ is wrong. You should say ‘He lied to me‘”. Others countered this: “if you can’t support or encourage her at least don’t spew venom. Jealousy is not good”. This discussion among Indian MPs does not distract from the views of other users like protesting farmers. Some supportive voices mentioned progress while criticising the school strikes; or tweeted expressions of support for the conversation: “thank you for representing girls around the world”.

The third level of analysis examines these conversations as strategic communication. The conversation flow is omnidirectional and diachronic: replies and mentions spread across a multiplicity of micro-spheres and multi-issue conversations. They represent arenas and detailed analysis shows that there is a continuous and agile process of negotiation of meanings. This contributes to building a collective actor that participates in the public sphere with a significant strategic purpose. Activism is fluid and disruptive as the conversations do not immediately crystallise into a single organisational form. Instead, they emerge almost spontaneously from the hashtag aggregator process. Actors and stakeholders have interchangeable roles within the communication process, both at the strategic and operational levels.

The visibility of the micro-political actions manifested both on Twitter and on the streets extends a conversation that emerges as a set of coordinated actions. These discussions, therefore, mirror performative civic relations that fulfil all the dimensions of the definition. Solutions are discussed and measures presented, and involve a variety of stakeholders, including actors such as the media or other organisations like 350.org. The conversations also influence the public agenda. Firstly, because traditional public sphere actors, like politicians and the media, are also in the discussion. Secondly, because the movement deals with the press coverage of actions such as strikes, or interviews with spokespeople or with local FFF ambassadors. The reproduction of spontaneous leaders shadows Greta Thunberg’s unique communication proposition, including the style of the photo and presentation. Hence, it cannot be seen from the outside if this is intentional management, or rather what can be called purposeful reproduction that adapts to the local contexts of action.

Discussion

The empirical work identified stakeholders/actors (RQ1); communicative patterns (RQ2); communication, organisational, and strategic communication (RQ3); and democratic activity within FFF (RQ4).

RQ1:

Citizens are the main actors in the conversation, but their activity connects with that of other organisations and social movements (like 350.org or Greenpeace). The media and politicians also make fleeting appearances, but they do not monopolise attention or make the movement more profitable. These appearances confirm the social relevance of the movement. The dynamics of the public debate are changing, and the actors involved shape the global conversation around climate change. This is revealed by the ongoing intensive repertoire of discourses and societal processes. The sample identified a marked presence of the German community (.c) and reveals a visibly critical and perhaps very polarised community in which right-wing German politicians link to the FFF movement to criticise communism.

RQ2:

The hashtag analysis revealed clear conversational patterns. The absence of management or moderation of the conversation shows orderly disorganised interactions. The Twitter activity is organic overall, with few clearly differentiated modular communities emerging. Patterns and topic-areas are repeated week after week without much variation (see ). The technical features of Twitter favour this spontaneous structure. Identifying behavioural patterns (in conversations as networked interactions and as attribute enunciations) facilitates an understanding of the FFF movement. A future task will be to explore the specific shapes of the Twitter conversations. For now, they show an agile process of interconnected arenas that flow in multiple directions, negotiating meanings (through hashtags) and building common spaces of shared understanding. These repetitive types of interaction identified by the network analyses also materialise civic relations. They form patterns of strategic communication: a common set of hashtags (as locations to meet), and a discussion aimed at finding solutions. They have a shared motivational drive and set goals and actions which are then compiled into an archive of shared memories (website).

RQ3:

Conversations and interactions on Twitter help to organise and negotiate positions and challenge community members by providing strategic reminders of the main shared goals. These conversations are consistent across the analysed activity and even present similar formulations. In practice, they reproduce the communication strategies used for organisational communication, or that are managed (as in planned and implemented) in order to contribute to achieving goals. And yet, the model devised on Twitter is fluid and disruptive. Users translate actions in the offline sphere (strikes around the world) to the online sphere and vice versa using data visualisations, images, and videos shared through hashtags (i.e. #Fridays4future, #climatestrike) as well as mentions (i.e. @GretaThunberg). All these conversations contribute to move (often local on the ground) private activity into the public sphere, which gives them a relevant strategic role for the whole movement. It is a permanent loop of updating, contagion, and dissemination.

The conversations during the weeks analysed were mostly initiated by citizens, some of whom were clearly acting on behalf of FFF. However, their interventions have transformative capacity and impact (replies, comments, likes) and include evidence of local engagement and action, photos, and videos. This capacity mirrors the role of these conversations in enhancing the sense of belonging to a globally interconnected movement of action and decision structures. All these features point towards the idea that FFF can be considered as an organisation, although one that is fluid and disruptive, as well as providing insight into the role of its communication.

The analysis also revealed the presence of the four flows of communication, as well as categories of dissent and protest PR at work. The movement conducts civic relations in digital arenas as a way of generating discussion in order to reach consensus, without any apparent coordination. This takes the form of demonstrations and street actions that all citizen activists can initiate while acting as curators of the information driven by the constitutive process of sensemaking.

RQ4:

Greta Thunberg is probably the most visible face of the movement, but the data shows that her action on Twitter is not central. Her interventions are few but impactful and include data, generating retweets and replies, and sharing media appearances. Her tweets mainly describe what is happening around the world (fact-based). She launches calls to action because “activism works”, and her tweets can be motivational and messianic for the community. However, she is not the individual protagonist. Instead, it is the Twitter community that amplifies and sustains the conversation. We can conclude that activism rather than clicktivism is important here. Greta Thunberg is part of the movement, but she is not the movement. The absence of a single personalist leader and the presence of contradictory views in the discussion, as well as the absence of formal conversational moderation, show that FFF is a social movement with democratically valued interactions. This is exemplified by the critical interventions, a continuing community (that repeats over the weeks), strong horizontality in the online interactions (without personal or geographic centres in the networks), and an open critical debate oriented towards solutions and allowing discrepancy and disagreement).

Conclusions

Twitter perceived as public sphere

The conversations on Twitter include appeals to people to exercise their right to be part of a political community. These statements strengthen democracy, local constitutions, and improve conditions for participation. This supports the idea that Twitter is perceived as a public sphere, with statements that evoke, for example, the right to organize and participate in peaceful gatherings or demonstrations without prior permission. This assumption aligns with efforts to keep the debate clean and the information undistorted. Science-based arguments and content from third party sources are often used. This same liberty, however, includes efforts to discredit or misinform. For example, accusations stating that the movement is only there to express ideas of the extreme left, or that it is a front to engage naive middle-class citizens.

A fluid disruptive organisation

The use of intertextual references and rhetoric figures enriches the discussion and helps to disseminate ideas and increase engagement. The presence of a strong logos with concrete arguments or positions, together with a pathos mirrored by language using comparison, hyperbole and humorous soundbites, lightens up the conversation. It also reinforces the figure of the citizen-activist within the disruptive dynamic of a fluid organisation. Freedom of speech is assumed and does not depend on formal membership or a form of authority or structural legitimation provided by the organisation. Differing from the norm of internal meetings, the conversation is open to observation, ratification, and participation by externals in a mega-arena dynamic. There does not appear to be any kind of behind-the-scenes planning or management of the hashtag movement on Twitter. At the same time, it cannot be stated that the discussion simply occurs spontaneously, though its features seem to shape organisational open source fluid activism.

The full dimension of socio-communicative civic relations and strategic communication at FFF is evident here. The online conversations are not loose and chaotic, but instead appear as omnidirectional and diachronic. And yet, the use of communication to engage in strategic conversations cannot be considered a purposeful or conscient act. Perhaps it would be reasonable to consider such strategic communication as a conditioned non-rational process from an actor with a goal that, in this case, is not organisationally driven, but rather the catalyst of a socio-communicative process in the public sphere.

Practical implications

FFF shows that citizens want to act and are ready to do so. They search for solutions for the ‘planet’ and aim towards a common good. These citizens shape and set the political climate agenda as part of a process taking place through online socio-communicative action. The public sphere dynamics are not linear. Also, the prominence of its online activity means it may not resonate well with the traditional media. For this reason, the movement might not be considered the appropriate intermediary actor for institutional political discussion in a time of crisis. Yet only time will reveal how the movement will develop.

This study shows that #FridaysForFuture is part of an alternative dynamic that disrupts the regular activity of democratic institutions and is a non-linear complex global process. An initial analysis of the organic functioning of the movement has identified communicative patterns and the issues that shape the discussion. It has shown that, for the case in hand, the concept of organisation and its form and functioning are challenged. Hence, strategic communication appears differently than the way it is usually understood, moving from a meso to a macro level. We propose that communication managers at non-profit and other organisations could consider a post-modern approach to facilitating and enabling the organisation or movement to organise the communication process in a strategic and operational dimension, rather than planning and guiding it.

Limitations and future research

The high volume of data analysed is limited to one single digital platform. While this is central to the movement, it is only one aspect of its activity. The specific sample of 5 weeks in 2021 also sets conditions for the analysis, and thus the statements in this article cannot be assumed to extend beyond these frames. Future research could perform a detailed analysis of data from other temporary spaces and social networks of FFF in order to continue to unravel the extent of this global and planetary phenomenon. Another direction could be to explore the non-visible side of the FFF as an organisation to understand what may lie behind it in terms of strategy and management. Similarly, research on other civic movements of a similar nature (e.g. #OccupyWallStreet, #BlackLivesMatters, #MeToo) could offer a contrast with the communicative patterns identified in this article. Future contributions will also aim to, on the one hand, enhance the theoretical possibilities of this initial research and on the other, make recommendations for policy-makers to incorporate these participatory and horizontal practices into their decision-making processes. Only after these features have been unveiled, will it be possible to gain a deeper understanding of the interface between the hashtag movements and the public sphere.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (513.8 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2023.2204299

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Following the ethical recommendations of the Association of Internet Researchers, users with a prominent community in Twitter (of over 15,000 followers) and with profiles verified by the digital platform are mentioned explicitly. These are considered public profiles.

2 Mike Hudema tweet: https://twitter.com/MikeHudema/status/1407001379013545995.

References

- Adi, A. (2018). Protest public relations: Communicating dissent and activism – an introduction. In A. Adi (Ed.), Protest public relations (pp. 1–11). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351173605

- Adi, A., & Moloney, K. (2012). The importance of scale in Occupy movement protests: A case study of a local Occupy protest as a tool of communication through public relations and social media/La importancia de la magnitud de las protestas del movimiento Occupy: el caso de una protesta. Revista Internacional De Relaciones Públicas, 2(4(jul–dic), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.5783/revrrpp.v2i4(jul-dic).105

- Ali, H. M., Saniei, S., O’Leary, P., & Boddy, J. (2022). Activist public relations in developing contexts where rules and norms collide: Insights from two activist organizations against gender-based violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Communication Management, 26(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-09-2021-0101

- Arendt, H. (1951). The origins of totalitarianism. Harcourt.

- Bastos, M. T., Mercea, D., & Charpentier, A. (2015). Tents, tweets, and events: The interplay between ongoing protests and social media. Journal of Communication, 65(2), 320–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.com.12145

- Belinskaya, Y. (2021). The ghosts Navalny met: Russian YouTube-sphere in check. Journalism and Media, 2(4), 674–696. https://doi.org/10.3390/journalmedia2040040

- Brantner, C., & Rodríguez-Amat, J. R. (2016). New “danger zone” in Europe: Representations of place in social media–supported protests. International Journal of Communication, 10(22), 299–320. http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/3788

- Brantner, C., Rodríguez-Amat, J. R., & Belinskaya, Y. (2021). Structures of the public sphere: Contested spaces as assembled interfaces. Media and Communication, 9(3), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i3.3932

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. (2015). Twitter hashtags from ad hoc to calculated publics. In N. Rambukkana (Ed.), Hashtag publics (pp. 13–28). Peter Lang.

- Candón-Mena, J. (2011). Internet en movimiento: nuevos movimientos sociales y nuevos medios en la sociedad de la información. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. https://eprints.ucm.es/12085/

- Castells, M. (2000). La era de la información. La sociedad red (2nd.a ed.). Alianza Editorial.

- Castells, M. (2008). The new Public Sphere: Global civil society, communication networks, and global governance. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 616(1), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311877

- Chadwick, A., & Chadwick. (2007). Digital network repertoires and organizational hybridity. Political Communication, 24(3), 283–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600701471666

- Colleoni, E., Rozza, A., & Arvidsson, A. (2014). Echo chamber or public sphere? Predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in Twitter using big data. Journal of Communication, 64(2), 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12084

- Earl, J., & Kimport, K. (2009). Movement societies and digital protest: Fan activism and other nonpolitical protest online. Sociological Theory, 27(3), 220–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2009.01346.x

- Ferra, I., & Nguyen, D. (2017). #Migrantcrisis: «etiquetando» la crisis migratoria europea en Twitter. Journal of Communication Management, 21(4), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-02-2017-0026

- Fishman, R. M., & Everson, D. W. (2016). Mechanisms of social movement success: Conversation, displacement and disruption. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 74(4), e045. https://doi.org/10.3989/ris.2016.74.4.045

- Franzke, A. S., Bechmann, A., Zimmer, M., Ess, C., & the Association of Internet Researchers. (2020). Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0. https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf

- Fraser, N. (1996). Multiculturalism and gender equity: The US “difference” debates revisited. Constellations, 3(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8675.1996.tb00043.x

- Fridays For Future. (n.d.). Social media. Social movement feed. https://fridaysforfuture.org/take-action/social-media/.

- Garnham, N. (2007). Habermas and the public sphere. Global Media and Communication, 3(2), 201–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742766507078417

- Geiger, R. S. (2009). Does Habermas understand the Internet? The algorithmic construction of the blogo/public sphere. Gnovis: A Journal of Communication, Culture, and Technology, 10(1), 1–29. http://stuartgeiger.com/papers/gnovis-habermas-blogopublic-sphere.pdf

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

- Gutiérrez-Rubí, A. (2021). Artivismo: el poder de los lenguajes artísticos para la comunicación política y el activismo. Editorial UOC.

- Habermas, J. (2006). Political communication in media society: Does democracy still enjoy an epistemic dimension? The impact of normative theory on empirical research. Communication Theory, 16(4), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00280.x

- Habermas, J., Lennox, S., & Lennox, F. (1974). The public sphere: An encyclopedia article (1964). New German Critique, 3(3), 4–55. https://doi.org/10.2307/487737

- Hallahan, K., Holtzhausen, D., van Ruler, B., Verčič, D., & Sriramesh, K. (2007). Defining Strategic Communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 1(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/15531180701285244

- Haßler, J., Wurst, A. K., Jungblut, M., & Schlosser, K. (2021). Influence of the pandemic lockdown on Fridays for Future’s hashtag activism. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211026575

- Haw, A. L. H. (2020). What drives political news engagement in digital spaces? Reimagining ‘echo chambers’ in a polarised and hybridised media ecology. Communication Research and Practice, 6(1), 38–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/22041451.2020.1732002/

- Heide, M., von Platen, S., Simonsson, C., & Falkheimer, J. (2018). Expanding the scope of strategic communication: Towards a holistic understanding of organizational complexity. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 452–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1456434

- Himelboim, I., Smith, M. A., Rainie, L., Shneiderman, B., & Espina, C. (2017). Classifying Twitter topic-networks using social network analysis. Social Media + Society, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691545

- Holtzhausen, D. R. (2008). Strategic communication. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Communication (pp. 48–55). Wiley‐Blackwell.

- Holtzhausen, D., & Zerfass, A. (2015). Strategic communication: Opportunities and challenges of the research area. In D. Holtzhausen & A. Zerfass (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of strategic communication (pp. 3–17). Routledge.

- Jacobs, R. N. (1999). Race, media and civil society. International Sociology, 14(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580999014003008

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1944). The People's Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

- Lindgren, S. (2019). Movement mobilization in the age of hashtag activism: Examining the challenge of noise, hate, and disengagement in the # MeToo campaign. Policy & Internet, 11(4), 418–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.212

- Luengo, G. (2010). Crisis analógica, futuro digital. Proceedings IV Congreso Online del Observatorio para la Cibersociedad, pp. 12–29, Nov. 2009, Cornellá, España. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=429442

- Lynn, T., Rosati, P., & Nair, B. (2020). Calculated vs. ad hoc publics in the #Brexit discourse on Twitter and the role of business actors. Information, 11(9), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11090435

- Marquardt, J. (2020). Fridays for Future’s disruptive potential: An inconvenient youth between moderate and radical ideas. Frontiers in Communication, 5(48). https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00048

- McPhee, R. D., & Zaug, P. (2000). The communicative constitution of organizations: A framework for explanation. Electronic Journal of Communication/La Revue Electronique de Communication, 10(1–2). http://www.cios.org/getfile/MCPHEE_V10N1200

- Moloney, K., McQueen, D., Surowiec, P., & Yaxley, H. (2013). Dissent and protest public relations. Public Relations Research Group (The Media School, Bournemouth University). https://research.bournemouth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Dissent-and-public-relations-Bournemouth-University.pdf

- Negt, O., & Kluge, A. (1973). Öffentlichkeit und Erfahrung: Zur Organisationsanalyse von bürgerlicher und proletarischer Öffentlichkeit [Public sphere and experience: Toward an analysis of the bourgeois and proletarian public sphere]. Suhrkamp.

- Oliveira, E. (2019). The instigatory theory of NGO communication: Strategic communication in civil society organisations. Springer VS.

- Padilla Molina, A. (2020). twitter_full_archive_DB/[Software]. Available at: https://github.com/AdriaPadilla/Twitter-API-V2-full-archive-Search-academics/tree/main/twitter_full_archive_DB Retrieved online October , 2021

- Putnam, L., & Nicotera, A. M.(Eds.). (2009). Building theories of organization: The constitutive role of communication Routledge.

- Robles, C. S., & Zambrano, R. E. (2011). Relaciones públicas 2.0 (y Educomunicación) ¿De qué hablamos realmente? Un acercamiento conceptual y estratégico. Fonseca, Journal of Communication, 3, 72–96. https://revistas.usal.es/index.php/2172-9077/article/view/11919

- Ruiz Ruiz, J. (2009). Sociological discourse analysis: Methods and logic. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-10.2.1298

- Smith, B. G., Krishna, A., & Al-Sinan, R. (2019). Beyond slacktivism: Examining the entanglement between social media engagement, empowerment, and participation in activism. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13(3), 182–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2019.1621870

- Sparks, C. (2001). The Internet and the global public sphere. Cambridge University Press.

- Tas, T., & Tas, O. (2014). Resistance on the walls, reclaiming public space: Street art in times of political turmoil in Turkey. Interactions: Studies in Communication & Culture, 5(3), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1386/iscc.5.3.327_1

- Thomas, G., & Wyatt, S. (1999). Shaping cyberspace: Interpreting and transforming the Internet. Research Policy, 28(7), 681–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00016-5

- Treré, E. (2016). The dark side of digital politics: Understanding the algorithmic manufacturing of consent and the hindering of online dissidence. IDS bulletin, 41(1), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2016.111

- Ugarte, D. (2007). El poder de las redes. Manual para personas, colectivos y empresas abocadas al ciberperiodismo. Ediciones El Cobre. http://www.pensamientocritico.org/davuga0313.pdf.

- Van Ruler, B. (2018). Communication theory: An underrated pillar on which strategic communication rests. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1452240

- Wahlström, M., Kocyba, P., de Vydt, M., de Moor, J., Adman, P., Balsiger, P., & Zamponi, L. (2019). Fridays for Future: Surveys of climate protests on 15 March 2019 in 13 European cities. Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/xcnzh/

- Walzer, M. (1999). On toleration. Yale University Press.

- Winkler, P., & Etter, M. (2018). Strategic communication and emergence: A dual narrative framework. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 382–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1452241

- Zerfass, A., Verčič, D., Nothhaft, H., & Werder, K. P. (2018). Strategic communication: Defining the field and its contribution to research and practice. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 12(4), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/1553118X.2018.1493485

- Zulli, D. (2020). Evaluating hashtag activism: Examining the theoretical challenges and opportunities of# BlackLivesMatter. Participations, 17(1), 197–215. https://participations.org/Volume%2017/Issue%201/12.pdf

Appendix

Weeks sampling (one per month, except for April) with similarly low Twitter activity oscillating between 15565 and 17486 tweets and retweets). The final sample was filtered again to eliminate retweets.

Table 1. Sample of 5 non-consecutive weeks with similar amounts of tweets.