Abstract

Objectives: This narrative review article provides an overview of current psychotherapeutic approaches specific for adjustment disorders (ADs) and outlines future directions for theoretically-based treatments for this common mental disorder within a framework of stepped care.

Methods: Studies on psychological interventions for ADs were retrieved by using an electronic database search within PubMed and PsycINFO, as well as by scanning the reference lists of relevant articles and previous reviews.

Results: The evidence base for psychotherapies specifically targeting the symptoms of AD is currently rather weak, but is evolving given several ongoing trials. Psychological interventions range from self-help approaches, relaxation techniques, e-mental-health interventions, behavioural activation to talking therapies such as psychodynamic and cognitive behavioural therapy.

Conclusions: The innovations in DSM-5 and upcoming ICD-11, conceptualising AD as a stress-response syndrome, will hopefully stimulate more research in regard to specific psychotherapeutic interventions for AD. Low intensive psychological interventions such as e-mental-health interventions for ADs may be a promising approach to address the high mental health care needs associated with AD and the limited mental health care resources in most countries around the world.

Introduction

Adjustment disorders (ADs), and other mental disorders specifically associated with stress, are among the most often diagnosed psychopathological entities by clinicians worldwide (Reed et al. Citation2011; Evans et al. Citation2013). Despite this, ADs in particular have suffered from major neglect in research efforts (Laugharne et al. Citation2009). Consequently there has been a long-lasting debate around and criticism of the category of ADs. First, researchers expressed their concerns about its validity, given a substantial overlap with other mental disorders as well as with normal stress coping (Maercker et al. Citation2007; Strain and Diefenbacher Citation2008; Baumeister and Kufner Citation2009). Second, ADs are often labelled as ‘waste basket’ diagnoses (i.e. residual diagnosis), referring to the fact that it is a rather unspecific diagnostic category (Maercker et al. Citation2007; Baumeister and Kufner Citation2009). Despite these critics, the clinical utility of ADs as ‘wild card’ diagnosis, when no other disorder seems appropriate, is widely recognised (Casey and Bailey Citation2011). Moreover, the advances of DSM-5, as well as the new proposals for ICD-11, will hopefully lead to further progress in sharpening the category of ADs and consequently to more research efforts towards building an evidence base.

ADs are by definition related to a critical life event or a series of stressful events. It is assumed that stressors related to AD are lower in intensity and gravity than traumatic events preceding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), although there is some evidence that such severe events can also trigger AD (Casey Citation2009, Citation2014). Conceptually, AD lies in the middle ground on a continuum between normal stress responses and pathological reactions (Baumeister et al. Citation2009). The differentiation of a normal response to a stressor and dysfunctional stress coping is based on the severity and the duration of symptoms or impairments, and should take cultural and (inter)personal factors into account (Baumeister and Morar Citation2008; Casey Citation2014). A theory-driven model of AD was proposed by Maercker et al. (Citation2007) by referring to key psychological models of PTSD (Foa and McNally Citation1995; Brewin et al. Citation1996; Horowitz Citation1997; Ehlers and Clark Citation2000). They proposed that AD, as a stress response syndrome, can be operationalised by the same way as the core symptoms of PTSD, namely avoidance, intrusions and failure to adapt (Maercker et al. Citation2007). Intrusive preoccupation with the stressor and inability to adapt are the core symptoms in the current conceptualisation of AD for the upcoming ICD-11 (Maercker et al. Citation2013). Still, however, DSM-5 allows the classification of ADs in a very broad way comprising ADs (1) with depressed mood, (2) with anxiety, (3) with mixed anxiety and depressed mood, (4) with disturbance of conduct, (5) with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct, as well as (6) with a ‘unspecified’ specifier (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013).

Taken together, ADs can be seen to comprise a substantial public health issue given the high prevalence (Mitchell et al. Citation2011; Maercker et al. Citation2012) and the burden associated with ADs (Carta et al. Citation2009; Arends et al. Citation2012). Hence, there is a need for evidence-based interventions for the treatment of ADs and it is timely to provide an overview of psychotherapies for ADs given the current revisions of our classification systems DSM and ICD.

Methods

The present overview is a narrative review on the current literature of psychotherapy for ADs. The electronic databases PubMed and PsycINFO were searched for relevant papers that were published in peer-reviewed journals until October 2016 using the search terms ‘adjustment disorder’ OR ‘adjustment disorders’ for the title function of the databases. After resolving duplicates, the search yielded 349 articles. As we were primarily interested on the diversity of psychological interventions for AD, the only inclusion criterion was that the publication was an empirical study on psychological interventions specific to AD. Relevant papers were retrieved by reading the titles and abstracts of the publications. Second, the reference lists of the included studies and reviews were scanned in order to identify further relevant studies. Thirty-three original studies (17 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 16 pilot/case studies or other designs) on psychological interventions specific for AD were included (see ). Additional relevant studies on psychotherapeutic approaches to mental disorders that share some symptomatic features with AD (such as depression, PTSD or anxiety) were incorporated, in order to expand the scope for evidence-based treatments that might contribute to psychological interventions for AD. The present review should still be read as a narrative review, notwithstanding its systematic literature search on psychological interventions for ADs.

Table 1. Included studies on psychological and psychotherapeutic interventions to AD.

Psychotherapeutic and psychological interventions for ADs

The majority of therapeutic interventions to AD have three broad components in common (Strain and Diefenbacher Citation2008; Casey Citation2009). First, psychological interventions aim to enable the individual to reduce or remove the stressor. For example, the impact of a stressor, such as sudden unemployment, might be alleviated at the moment the patient is able to find a new job. If a stressor is ongoing and not removable (e.g. terminally ill cancer), some measures, such as establishing social support to attenuate the impact of the stressor, may enhance quality of life and re-establish functioning. Second, interventions try to enhance the coping abilities with the stressor and maximise adaptation. For example, cognitive coping strategies might include the identification of negative thoughts and their replacement by more functional thoughts. On a behavioural level, assisting patient activation may facilitate experiences of self-efficacy. Third, symptom reduction and behavioural change is another important goal to reduce distress and improve functioning in the long run. Therapeutic approaches might vary widely in this context, depending on the respective underlying nosological model, as interventions for rather unspecific symptom profiles (e.g. mixed depressive–anxiety symptoms) or a more specific model such as ‘subthreshold PTSD’ require differing treatment attempts.

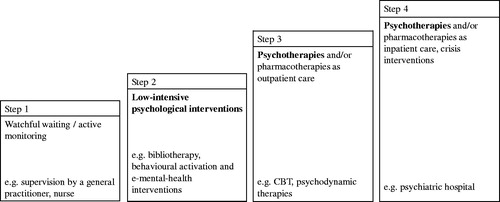

Most researchers in the field of AD share the opinion that the first-line treatment of ADs are brief psychological interventions and psychotherapy (Strain and Diefenbacher Citation2008; Carta et al. Citation2009; Casey Citation2014). This clinical rather than evidence-based recommendation most likely builds on the potentially transient nature of the disorder and risk–benefit considerations for more invasive alternatives for mental disorders, which may resolve over time without any intervention. Accordingly, Bower and Gilbody (Citation2005) suggest a stepped care approach for such subthreshold diagnoses on the continuum between normal stress response and mental disorder. Such an approach might best ensure that patients receive the least restrictive, but adequate, amount of support which is needed to improve distress and impaired functioning.

Given the transient nature of ADs with symptoms defined to dissolve after 6 months once the stressor or its consequences have terminated (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013), watchful waiting should be sufficient for people with AD. Knowing, however, about the complexity of the course of mental disorders, the risk of chronicity and progression once symptoms are present, as well as the fact that stressors and (particularly) their consequences might not terminate completely, the most logical indication of ‘just watching until symptoms resolve’ may fall short and need further steps at hand ().

Figure 1. Stepped care approach for adjustment disorders (psychological intervention parts highlighted).

As a second step, low intensive psychological interventions, such as bibliotherapy, behavioural activation and e-mental-health interventions are suggested (Baumeister Citation2012; van Straten et al. Citation2015; Domhardt et al. Citation2018). Thereby, ‘low intensity’ might refer to both, interventions, necessitating limited health care resources and/or mental health expertise (i.e. limited time from a health care professional necessary; intervention can be provided by trained non-mental health professionals) as well as interventions associated with limited costs (i.e. monetary, time, side effects and adverse events) for patients. Thus, less-intensive treatments are suggested as a second step given their presumed preferable risk–benefit ratio compared to more intensive and more invasive interventions.

The following overview on the evidence of psychological and psychotherapeutic interventions for AD follows the categorisation of these into low and more intensive psychological interventions. The stepped care model described here, builds on prior research on other mental disorders (Bower and Gilbody Citation2005; van Straten et al. Citation2015) and has not been validated for ADs. Moreover, a sophisticated stepped care model would need to provide detailed information on each step, stepping-up-rules and differentiations according to possible target populations and clinical courses. As this is beyond the scope of the present review, the stepped care model should be seen as a heuristic for subdividing psychological approaches for ADs.

Low intensive psychological interventions for ADs

Low intensive psychological interventions offer several advantages. They require limited resources in terms of training and wages for therapists, as they might be provided by less specialist health workers (Richards et al. Citation2016; Baumeister Citation2017). They might be equally effective than the first-line treatment in some cases; for example, behavioural activation, provided by junior mental health workers, was shown to be not inferior to cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in the treatment of depression (Richards et al. Citation2016), and guided internet-based interventions were shown to be comparably effective as face-to-face therapies for depressive and anxiety disorders (Andersson et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, low intensive psychological interventions are attractive, given their potential for scaling-up, which might help to close the gap between treatment demand and the availability of evidence-based psychological interventions. This is especially important in regard to ADs, as in some low-income countries these are the most common mental disorders associated with completed suicide (Manoranjitham et al. Citation2010).

In the following sections, the empirical evidence for several low intensive psychological interventions specifically designed for ADs are outlined ().

Self-help/bibliotherapy

The group of Maercker developed a self-help manual for AD applying a stress-response syndrome model, similar to that outlined in the beta draft of the ICD-11, which can be applied as a bibliotherapeutic (Bachem and Maercker Citation2016) or as an upcoming e-mental-health intervention (Maercker et al. Citation2015). The CBT-oriented self-help manual specifically designed for the group of burglary victims comprises several modules (screening for AD symptoms, psychoeducation, checklist if face-to-face psychotherapy was more appropriate, sense of self, coping, activation and recovery) that consist of proven exercises from therapeutic interventions for PTSD, anxiety disorders and depression (Maercker et al. Citation2015). The components of this stand-alone intervention address symptoms of preoccupation and failure to adapt and are to be worked through in about 4 weeks. The effectiveness of the bibliotherapeutic version of the self-help manual was empirically tested in an RCT in a sample of burglary victims with clinical or subclinical symptoms of AD (Bachem and Maercker Citation2016). The intervention group showed greater improvement in the AD symptoms of preoccupation and in post-traumatic stress symptoms compared to a wait-list control. This study is in line with the evidence on bibliotherapy for other mental disorders (Gregory et al. Citation2004), suggesting their efficacy as a first intervention step for patients with AD.

Support groups

A meta-analysis revealed that the prevalence rate of AD in patients with cancer is 19.4% (Mitchell et al. Citation2011). Benefits of support groups and individual psychotherapy on reducing distress, psychopathology and pain in cancer patients are well established (Spiegel Citation2012). The majority of studies regarding the effects of intensive emotional support on survival rates indicate that there is a positive effect on longevity in a variety of cancers (including malignant melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, leukaemia and gastrointestinal tract cancer), although the results on survival rates of emotional support in studies in patients with breast cancer are mixed (Goodwin Citation2005; Spiegel Citation2012). Currently, the efficacy of a cognitive behavioural therapy group programme for patients with somatic diseases and comorbid depressive or ADs is being evaluated in an RCT (Ruesch et al. Citation2015). Beyond AD, the impact of peer support on patient mental health and well-being is well documented (Davidson et al. Citation2012; Mahlke et al. Citation2014). Similar to behavioural activation and bibliotherapy, peer support approaches might be one possible solution to improve mental health care in regions with restricted health care researches and a lack of trained mental health experts.

Mindfulness, meditation and relaxation

As a generic approach, relaxation techniques combined with psychoeducation offer the advantage to be implemented in various subtypes of AD, although they might be especially helpful in depressive and stress symptoms, as indicated by a recent review (Shah et al. Citation2014). In a mixed-sample study (Bos et al. Citation2014), mindfulness training was associated with an improvement in psychological symptoms, quality of life and mindfulness skills in patients with AD. In an RCT (Sundquist et al. Citation2015), mindfulness-based group therapy was similarly effective as individual-based CBT for primary care patients with depressive, anxiety or stress and ADs. Srivastava et al. (Citation2011) found that yoga meditation techniques were effective in reducing symptoms of AD with anxiety and depression. Most recently, there is a web-based intervention specifically designed for AD that incorporates a module of mindfulness (Skruibis et al. Citation2016). Jojic and Leposavic (Citation2005a, Citation2005b) evaluated the effectiveness of autogenic training in adolescents and adults with AD. In two studies, they found that autogenic training significantly decreased the values of physiological indicators (blood pressure, pulse rate, concentration of cholesterol and cortisol) of AD after the intervention and at a 6-month follow-up in adolescents (Jojic and Leposavic Citation2005a) and adults with AD (Jojic and Leposavic Citation2005b).

E-mental-health interventions

The efficacy of e-mental-health interventions for major mental disorders is established (Andersson et al. Citation2014), their effectiveness in clinical practice proven (Andersson and Hedman Citation2013) and possible advantages regarding their cost-effectiveness as well as high accessibility acknowledged (Andersson and Titov Citation2014). The first e-mental-health intervention specifically addressing AD was developed by Andreu-Mateu et al. (Citation2012) based on the virtual reality programme ‘EMMA`s world’ (Botella et al. Citation2006) in Spanish. In this blended approach, virtual reality components inspired by PTSD therapy and positive psychology are combined with face-to-face therapy. First results from a case study showed its applicability and utility (Andreu-Mateu et al. Citation2012). The same group has extended the possibilities of virtual reality programmes to assist the therapeutic process by offering web-based personalised material for homework assignments specific to AD (Quero et al. Citation2012). Skruibis et al. (Citation2016) designed an internet intervention for AD, defined as a stress-response syndrome according to the proposal for ICD-11, structured in four modules: relaxation, time management, mindfulness and strengthening relationships. This intervention called BADI (Brief Adjustment Disorder Intervention) is currently evaluated in an RCT. The e-health interventions realised so far vary widely in terms of their target population, technical realisations and professional support. Thus, the amount of human support necessary for successfully treating ADs might become a more prominent question in future research. Most conceptualise e-health interventions as self-help interventions without human support (‘unguided self-help’) or with different intensity of human support (‘guided self-help’; Baumeister et al. Citation2016). In a recent systematic review, Baumeister et al. (Citation2014) showed that guided self-help interventions for mental disorders are superior to unguided self-help interventions. However, from an economic and a public health perspective, unguided interventions with their lower intervention costs might be a feasible second-line solution in case of restricted health care resources (Baumeister et al. Citation2014).

Behavioural activation

Behavioural activation has been shown to be an effective treatment for depression (Ekers et al. Citation2014), with a potential advantage regarding its cost-effectiveness compared to CBT (Richards et al. Citation2016). With some symptomatic overlap of AD and depression (Casey Citation2001), behavioural activation might also be a promising treatment approach for AD in order to overcome dysfunctional coping, withdrawal and enhance positive reinforcement from the environment. Indeed, four of nine studies included in a Cochrane Review (Arends et al. Citation2012) on interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with ADs had activating components in their treatment approaches. Van der Klink et al. (Citation2003), for example, successfully integrated an activating approach as well as CBT techniques in their intervention to reduce sickness leave due to AD.

In sum, there is some evidence that low intensive psychological interventions specific for AD are effective. Further research must prove, if the assumed advantages in regard to their cost-effectiveness and potential in improving reach and access for specific treatments for AD, holds true. None of the reported interventions was examined as part of a stepped care approach. Thus, the question of whether these interventions are recommendable as a second step following watchful waiting remains open.

Psychotherapies for ADs

Depending on the specific subtype of AD, the symptomatic patients with AD might differ considerably, and psychotherapeutic approaches might need to be tailored to the respective subtype. In a modular treatment approach, elements of interventions from evidence-based psychotherapies for depression, anxiety or PTSD might be an integral part of the approach (Bengel and Hubert Citation2010), complemented by further more specific stress-related interventions. In AD with depressed mood, therapeutic strategies derived from cognitive behavioural or interpersonal therapy, as recommended by the NICE guidelines for persistent subthreshold depressive symptoms or mild to moderate depression (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Citation2009), might be of significance. For instance, activation, building up of supportive social contact and cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional beliefs are also relevant in AD associated with depressive symptoms. In various anxiety disorders exposure-based (Olatunji et al. Citation2010) and relaxation-based (Manzoni et al. Citation2008) approaches are central and have proven to be efficacious. With the symptomatic overlap, it seems reasonable to integrate CBT-oriented exposure and relaxation techniques as an essential part in the therapeutic approach for AD with anxiety, complemented by further strategies that lead to changes in thinking and behaviour patterns, such as dissolving avoidance. In a conceptualisation of AD as a sub-threshold form of PTSD (Maercker et al. Citation2007; Citation2013), psychotherapeutic treatment approaches should target the core symptoms of intrusive preoccupation with the stressor and inability to adapt. The former symptom might be addressed by imaginative exposure, the latter by tailored interventions for the specific adaptation problem like sleep disturbance, concentration difficulty or reduced self-confidence (Bachem and Maercker Citation2016). In the subtype AD with disturbance of conduct, which is primarily relevant in children and adolescents, parent training and improvement in problem-solving skills might be an important part of the intervention strategy alike the treatment of oppositional defiant disorder in children and adolescents (Kazdin Citation2018).

Comprehensive therapeutic strategies that might be relevant in the psychotherapy of AD, regardless of the specific subtype, are the reduction of suicidality and self-harm behaviours, the mobilisation of resources as well as the acquisition of problem solving techniques and emotion-regulation skills (Strain and Diefenbacher Citation2008; Casey Citation2009; Bengel and Hubert Citation2010). Furthermore, in all idiosyncratic manifestations of AD, the removal or (if not feasible) reduction of the eliciting stressor should be a central part of psychotherapy. As stressors related to AD range from traumatic experiences (Casey Citation2009, Citation2014) to critical life events of a lesser magnitude, specific therapeutic interventions addressing the stressor should differ accordingly. In addition, the patients` subjective appraisal of the stressor might be a vital part in the psychotherapeutic treatment, especially in permanent and persistent stressors such chronic somatic diseases.

In the following sections the empirical evidence for psychotherapies for ADs are summarised. Specifically, these are cognitive behavioural therapy, psychodynamic therapies, interpersonal therapy, client-centred therapy, eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing, as well as some other examined treatment approaches for ADs ().

CBT

CBT has the overarching treatment goal of improving functioning and achieving symptom reduction, and relies on a range of different cognitive, behavioural and emotion-focussed techniques that eventually will help the patient to modify dysfunctional cognitions and to change maladaptive behavioural patterns (Hofmann et al. Citation2012). At present, CBT interventions specific for AD effectively target a range of different stressors like cancer (Schuyler Citation2004; Cluver et al. Citation2005) or burglary (Bachem and Maercker Citation2016). CBT techniques are successfully applied in diverse populations, such as military recruits (Nardi et al. Citation1994) or elderly patients (Frankel Citation2001). The modular design of some CBT manuals specifically designed for AD allows a similar implementation on individual and group level (e.g. Reschke Citation2011).

In a systematic Cochrane review by Arends et al. (Citation2012), evaluating the effectiveness of interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with ADs, nine RCTs (van der Klink et al. Citation2003; Blonk et al. Citation2006; Brouwers et al. Citation2006; Bakker et al. Citation2007; Vente et al. Citation2008; Rebergen et al. Citation2009; Stenlund et al. Citation2009; van Oostrom et al. Citation2010; Willert et al. Citation2011) were included. The review focussed on psychological interventions, as no RCTs were found for pharmacological interventions, exercise programmes or employee assistance programmes at the time. The authors concluded that CBT interventions did not significantly reduce time until partial return to work and did not significantly reduce time to full return to work compared with no treatment (Arends et al. Citation2012). In contrast, problem-solving therapy significantly enhanced partial return to work at 1-year follow-up compared to non-guideline-based care, but did not significantly enhance time to full return to work at 1-year follow-up (Arends et al. Citation2012). Three operationalisations of the problem-solving therapies included in the Cochrane Review were augmented by activating approaches (van der Klink et al. Citation2003; Brouwers et al. Citation2006; Rebergen et al. Citation2009), and one guideline-based intervention was further supplemented by CBT components (Rebergen et al. Citation2009), so that it seems justified to place problem-solving therapy in this case together with CBT as a more intensive psychological intervention for AD. Nevertheless, problem solving as a stand-alone approach is usually considered as a low-intensive intervention (van Straten et al. Citation2015).

Currently, the evidence-base for the efficacy and effectiveness of CBT for AD cannot keep up with the strong empirical support of CBT for other common mental disorders (e.g. Hofmann et al. Citation2012). Two ongoing RCTs and one pilot study, however, might further substantiate the evidence for various CBT-approaches specifically designed for AD (Maercker et al. Citation2015; Ruesch et al. Citation2015; Skruibis et al. Citation2016).

Psychodynamic psychotherapies

Psychodynamic therapies operate on an interpretive-supportive continuum and comprise a range of different manualised psychotherapies, and, thus, are intended to increase insight into wishes, affects, object relations or defence mechanisms (Leichsenring et al. Citation2015). Supportive interventions are deployed in order to advance the therapeutic alliance, to set goals or to consolidate psychosocial capacities such as reality testing or impulse control (Leichsenring et al. Citation2015).

Short-term dynamic psychotherapy (STDP) effectively reduced symptomatology in two studies with samples with primarily AD (with depressed mood or anxiety) via the mechanisms of overall defensive functioning (Kramer et al. Citation2010) and emotional processing (Kramer et al. Citation2015). In a RCT, brief dynamic psychotherapy (BDT) was superior over a wait list condition and was similar effective as brief supportive psychotherapy in reducing symptoms of minor depressive disorders and AD with depressed mood (Maina et al. Citation2005). The six-months-follow-up evaluation suggested that BDT was more effective than supportive psychotherapy in improving the long-term outcome in patients with minor depression and AD with depressed mood. Additionally, Ben-Itzhak et al. (Citation2012) found that a brief psychodynamic psychotherapy (twelve sessions in about three months) is equally effective as an intermediate term psychodynamic psychotherapy (twelve months) at the end of treatment, as well as at a nine-months-follow-up.

Interpersonal psychotherapy

In a pilot-study, Markowitz et al. (Citation1992) tested interpersonal psychotherapy in a sample with 23 depressed patients infected with HIV. Results indicate that the majority of the sample (20 patients) recovered from depression after an average of sixteen sessions of therapy.

Client-centred psychotherapy

Altenhöfer et al. (Citation2007) evaluated the effectiveness of an outpatient short-term client-centred psychotherapeutic intervention (limited to twelve sessions) compared to a wait list control in a sample of 50 patients with AD, triggered either by the loss of a significant person or a severe negative experience at work or university. Results of this non-randomised trial indicate significant improvements in symptoms, distress and functioning at post-treatment as well as at a three-month- (Altenhöfer et al. Citation2007) and two-year-follow-up (Gorschenek et al. Citation2008).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR)

Owing to the conceptualisation of AD as a stress response syndrome, it seems a viable way to target AD symptomatology (especially the dimensions of preoccupation with the stressor) in a similar way than PTSD (Novo Navarro et al. Citation2018) e.g. by means of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR). Mihelich (Citation2000) examined in a serial case study design the effects of two sessions of EMDR compared to two sessions of exposure in nine patients with AD. Patients with AD with anxiety or mixed anxiety and depressed mood showed a clinically significant improvement at follow-up, whereas participants with AD with depressed mood and persistent stressors did not benefit from EMDR treatment (Mihelich Citation2000). In a methodologically more rigorous RCT on 90 students without any mental disorder, Cvetek (Citation2008) found, that three hours of EMDR lead to significantly lower scores on the Impact of Event Scale compared to the active control and wait list control condition. Additionally, participants in the EMDR condition showed a significantly smaller increase in state anxiety at memory recall.

Other psychotherapeutic approaches

AD occurs frequently in patients with somatic disorders (Mitchell et al. Citation2011). Treatment approaches that aim to remedy the somatic disorders or alleviate their symptoms, and thus reduce or solve the core stressor essentially responsible for the AD, might also influence the symptomatology of AD positively. González-Jaimes and Turnbull-Plaza (Citation2003) for example evaluated a specifically designed emotional treatment for patients with AD with depressed mood as a consequence of acute myocardial infarction called ‘mirror therapy’. At post-test evaluation, patients in the mirror psychotherapy group showed significantly less AD symptoms compared to three different control groups (Gestalt psychotherapy, medical conversation and no treatment). At a sixth-month-follow-up, mirror therapy was more effective in reducing AD symptoms than the wait list control condition, but no more superior than the two other active control conditions.

Body-mind-spirit (BMS) therapy was developed by Chan (2001) and integrates concepts and practices from Western medicine (e.g. positive psychology and forgiveness therapy) and traditional Chinese medicine and Eastern philosophies (e.g. Buddhism and Confucianism). In a study by Hsiao et al. (Citation2014) BMS lead to changes in diurnal cortisol patterns and decreases in the occurrence of suicidal ideation in patients with AD with depressed mood.

Overall, compared to the knowledge of other major mental disorders (e.g. Hofmann et al. Citation2012; Fonagy Citation2015), the evidence-base for psychological and psychotherapeutic interventions for AD is rather limited. The best empirical support so far is found for cognitive behavioural therapies, problem-solving, relaxation techniques and psychodynamic therapies. EMDR and body-mind-spirit therapy are each supported with one RCT.

Several of the included studies have methodological limitations which may distort the conclusions made in regard to psychological interventions specific for AD. First, some studies relied on heterogeneous samples in which patients with AD are aligned with patients with a range of other mental disorders. So it is not clear in these studies if the therapeutic approaches tested are beneficial specifically in AD or may primarily be effective in related disorders such as depression or anxiety. Nevertheless, some commonalities in symptomatology and impairments suggest that these interventions are similarly effective in AD (Casey Citation2001). Second, almost half of the included studies did not conduct any randomisation to intervention and control condition, thereby limiting conclusions in regard to causality. Third, a considerable number of studies have relied on small sample sizes and thus, effect sizes should be interpreted with caution. At present, little knowledge exists of the magnitude of the positive effects of the various interventions included in this review, as a considerable number of articles did not report effect sizes and methodological standards of some included studies are restricted, limiting the interpretability of findings. After all, the present overview on psychotherapies of ADs itself might have some limitations inherent in narrative reviews (Cipriani and Geddes Citation2003; Pae Citation2015), as it remains possible that we oversaw relevant studies, despite the systematic literature search.

Future directions

Given the limited empirical evidence for psychological treatments of AD in general, there is a need for further studies and replication studies evaluating the efficacy of the specific interventions in pure cohorts of patients with AD. Although AD is an even more prevalent disorder in children and adolescents than in adults (Casey and Bailey Citation2011), only one study evaluated an intervention for adolescents with AD so far (Jojic and Leposavic Citation2005a). Therefore, efficacy studies on psychological interventions addressing symptoms of AD in this younger age group are urgently needed. Longitudinal designs would allow to identify patterns of change in regard to specific stressors, resilience and remission rates over the course of time and evolution to other disorders (Domhardt et al. Citation2015), as ADs are a known risk factor for the development of other mental disorders, especially in children and adolescents (Andreasen and Hoenk Citation1982).

Psychotherapy research in the field of AD, as a transient category, is particularly difficult, as the benefits observed in trials without a no-treatment control group might be in part due to spontaneous remission or depict merely an expectable course, since the stressor is eliminated. Thus, more research in regard to the mechanisms of change, and that establishes a direct and timely link of the therapeutic agent of the intervention to positive outcome is needed, as a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying psychotherapeutic change is crucial for optimising future treatment approaches (Kazdin Citation2007). The only two studies that focussed on mechanisms of change in psychotherapeutic interventions in ADs to this point, were the studies of Kramer et al. (Citation2010; Citation2015), which found that the positive effect of STDP is associated with changes in overall defensive functioning and emotional processing respectively.

Research in the field of AD has long suffered from a lack of a concise model of AD and corresponding specific diagnostic instruments. The conceptualisation of AD of the ICD-11 working group will lead to a higher discriminant validity of the category, especially in regard to depression (Maercker et al. Citation2015). Novel diagnostic instruments for AD like the self-report ‘Adjustment Disorder-New Module’ (ADNM; Einsle et al. Citation2010; Lorenz et al. Citation2016) and the absence of specific diagnostic instruments for AD and will allow future research efforts to create more homogenous samples of patients with AD and will make epidemiological studies more reliable (Baumeister et al. Citation2009).

With regard to the current clinical practice of treating ADs, health care services data are needed to examine the under-, over- and mis-provision of mental health care services for patients with AD. In this context, some question the frequent prescription of psychotropic drug as first-line approach for patients with subthreshold to mild mental disorders such as minor depression (Baumeister Citation2012). With 37% of patients with AD receiving a psychotropic drug prescribed by a general practitioner, Fernandez et al. (Citation2012) showed that this question might also apply in the context of AD. However, a more important and pressing global mental health issue is the provision of any evidence-based intervention, given the restricted availability and accessibility of respective treatments in most countries around the world. Low intensity, scalable psychological interventions, such as bibliotherapy or e-mental-health interventions, may provide the necessary means to minimise the current treatment gap.

In conclusion, although current psychological interventions for AD offer a range of different therapeutic approaches, their empirical evidence is rather limited. The innovations in the forthcoming ICD-11 will hopefully inspire more research in regard to specific therapeutic interventions for AD. Given the high global prevalence rates and the often rather mild symptomatology associated with ADs, future studies should examine stepped care models, scalable intervention approaches suitable to improve the burden associated with AD on a public health level, and psychological interventions taking culture and ethnicity specific aspects into account.

Statement of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altenhöfer A, Schulz W, Schwab R, Eckert J. 2007. Psychotherapie von Anpassungsstörungen. Psychotherapeut. 52:24–34.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Association.

- Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Riper H, Hedman E. 2014. Guided internet-based vs face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry. 13:288–295.

- Andersson G, Hedman E. 2013. Effectiveness of guided internet-based cognitive behavior therapy in regular clinical settings. Verhaltenstherapie. 23:140–148.

- Andersson G, Titov N. 2014. Advantages and limitations of internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 13:4–11.

- Andreasen NC, Hoenk PR. 1982. The predictive value of adjustment disorders: a follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 139:584–590.

- Andreu-Mateu S, Botella C, Quero S, Guillén V, Baños RM. 2012. La utilización de la realidad virtual y estrategias de psicología positiva en el tratamiento de los trastornos adaptativos. Behav Psychol. 20:323–348.

- Arends I, Bruinvels DJ, Rebergen DS, Nieuwenhuijsen K, Madan I, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Bultmann U, Verbeek JH. 2012. Interventions to facilitate return to work in adults with adjustment disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12:CD006389.

- Bachem R, Maercker A. 2016. Self-help interventions for adjustment disorder problems: a randomized waiting-list controlled study in a sample of burglary victims. Cogn Behav Ther. 45:397–413.

- Bakker IM, Terluin B, van Marwijk HWJ, van der Windt DAWM, Rijmen F, van Mechelen W, Stalman WAB. 2007. A cluster-randomised trial evaluating an intervention for patients with stress-related mental disorders and sick leave in primary care. PLoS Clin Trial. 2:e26.

- Baumeister H. 2012. Inappropriate prescriptions of antidepressant drugs in patients with subthreshold to mild depression: time for the evidence to become practice. J Affect Disord. 139:240–243.

- Baumeister H. 2017. Behavioural activation training for depression. Lancet. 389:366–367.

- Baumeister H, Kufner K. 2009. It is time to adjust the adjustment disorder category. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 22:409–412.

- Baumeister H, Maercker A, Casey P. 2009. Adjustment disorder with depressed mood: a critique of its DSM-IV and ICD-10 conceptualisations and recommendations for the future. Psychopathology. 42:139–147.

- Baumeister H, Morar V. 2008. The impact of clinical significance criteria on subthreshold depression prevalence rates. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 118:443–450.

- Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. 2014. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interv. 1:205–215.

- Baumeister H, Terhorst Y, Lin J. 2016. The Internet and Mobile technology: a platform for behavior change and intervention in depression and CVDs. In: Baune BT, Tully PJ, editors. Cardiovascular diseases and depression: treatment and prevention in Psychocardiology = Treatment and prevention in psychocardiology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 395–410.

- Bengel J, Hubert S. 2010. Anpassungsstörung und Akute Belastungsreaktion. Göttingen: Hogrefe; p. 113 (Fortschritte der Psychotherapie; vol. 39). ISBN: 9783801716226.

- Ben-Itzhak S, Bluvstein I, Schreiber S, Aharonov-Zaig I, Maor M, Lipnik R, Bloch M. 2012. The effectiveness of brief versus intermediate duration psychodynamic psychotherapy in the treatment of adjustment disorder. J Contemp Psychother. 42:249–256.

- Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. 2006. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work Stress. 20:129–144.

- Bos EH, Merea R, van den Brink E, Sanderman R, Bartels-Velthuis AA. 2014. Mindfulness training in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample: outcome evaluation and comparison of different diagnostic groups. J Clin Psychol. 70:60–71.

- Botella C, Baños R, Rey B, Alcañiz M, Guillen V, Quero S, García-Palacios A. 2006. Using an adaptive display for the treatment of emotional disorders. Extended Abstracts Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI 2006; April 22–27; Montréal, Québec, Canada: ACM.

- Bower P, Gilbody S. 2005. Stepped care in psychological therapies: access, effectiveness and efficiency. Narrative literature review. Br J Psychiatry. 186:11–17.

- Brewin CR, Dalgleish T, Joseph S. 1996. A dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rev. 103:670–686.

- Brouwers EPM, Tiemens BG, Terluin B, Verhaak PFM. 2006. Effectiveness of an intervention to reduce sickness absence in patients with emotional distress or minor mental disorders: a randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 28:223–229.

- Carta MG, Balestrieri M, Murru A, Hardoy MC. 2009. Adjustment disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 5:15.

- Casey P. 2001. Adjustment disorders: fault line in the psychiatric glossary. Br J Psychiatry. 179:479–481.

- Casey P. 2009. Adjustment disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. CNS Drugs 23:927–938.

- Casey P. 2014. Adjustment disorder: new developments. Curr Psychiatry Rep16:451.

- Casey P, Bailey S. 2011. Adjustment disorders: the state of the art. World Psychiatry. 10:11–18.

- Cipriani A, Geddes J. 2003. Comparison of systematic and narrative reviews: the example of the atypical antipsychotics. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 12:146–153.

- Cluver JS, Schuyler D, Frueh BC, Brescia F, Arana GW. 2005. Remote psychotherapy for terminally ill cancer patients. J Telemed Telecare. 11:157–159.

- Cvetek R. 2008. EMDR treatment of distressful experiences that fail to meet the criteria for PTSD. J EMDR Prac Res. 2:2–14.

- Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R. 2012. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 11:123–128.

- Domhardt M, Münzer A, Fegert JM, Goldbeck L. 2015. Resilience in survivors of child sexual abuse: a systematic review of the literature. Trauma Violence Abuse. 16:476–493.

- Domhardt M, Ebert DD, Baumeister H. 2018. Internet- und mobile-basierte Interventionen. In: Kohlmann C-W, Salewski C, Wirtz MA, editors. Psychologie in der Gesundheitsförderung. Bern: Hogrefe; p. 397–410.

- Ehlers A, Clark DM. 2000. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther.38:319–345.

- Einsle F, Kollner V, Dannemann S, Maercker A. 2010. Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychol Health Med. 15:584–595.

- Ekers D, Webster L, van Straten A, Cuijpers P, Richards D, Gilbody S. 2014. Behavioural activation for depression; an update of meta-analysis of effectiveness and sub group analysis. PLoS One. 9:e100100.

- Evans SC, Reed GM, Roberts MC, Esparza P, Watts AD, Correia JM, Ritchie P, Maj M, Saxena S. 2013. Psychologists' perspectives on the diagnostic classification of mental disorders: results from the WHO-IUPsyS Global Survey. Int J Psychol. 48:177–193.

- Fernandez A, Mendive JM, Salvador-Carulla L, Rubio-Valera M, Luciano JV, Pinto-Meza A, Haro JM, Palao DJ, Bellon JA, Serrano-Blanco A. 2012. Adjustment disorders in primary care: prevalence, recognition and use of services. Br J Psychiatry. 201:137–142.

- Foa E, McNally R. 1995. In: Rapee RM, editor. Current controversies in the anxiety disorders. New York (NY): Guilford Press; p. 329–343.

- Fonagy P. 2015. The effectiveness of psychodynamic psychotherapies: an update. World Psychiatry. 14:137–150.

- Frankel M. 2001. Ego enhancing treatment of adjustment disorders of later life. J Geriatr Psychiatry. 34:221–223.

- González-Jaimes EI, Turnbull-Plaza B. 2003. Selection of psychotherapeutic treatment for adjustment disorder with depressive mood due to acute myocardial infarction. Arch Med Res. 34:298–304.

- Goodwin PJ. 2005. Support groups in advanced breast cancer. Cancer. 104:2596–2601.

- Gorschenek N, Schwab R, Eckert J. 2008. Psychotherapy of adjustment disorders. Psychother Psych Med. 58:200–207.

- Gregory RJ, Schwer Canning S, Lee TW, Wise JC. 2004. Cognitive bibliotherapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 35:275–280.

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. 2012. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cogn Ther Res. 36:427–440.

- Horowitz MJ. 1997. Stress response syndromes: PTSD, grief, and adjustment disorders. 3rd ed. Northvale (NJ): Aronson; p. 358. ISBN: 0765700255.

- Hsiao F-H, Lai Y-M, Chen Y-T, Yang T-T, Liao S-C, Ho RTH, Ng S-M, Chan CLW, Jow G-M. 2014. Efficacy of psychotherapy on diurnal cortisol patterns and suicidal ideation in adjustment disorder with depressed mood. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 36:214–219.

- Jojic BR, Leposavic LM. 2005a. Autogenic training as a therapy for adjustment disorder in adolescents. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 133:424–428.

- Jojic BR, Leposavic LM. 2005b. Autogenic training as a therapy for adjustment disorder in adults. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 133:505–509.

- Kazdin AE. 2007. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 3:1–27.

- Kazdin AE. 2018. Implementation and evaluation of treatments for children and adolescents with conduct problems: findings, challenges, and future directions. Psychother Res. 28:3–17.

- Kramer U, Despland J-N, Michel L, Drapeau M, de Roten Y. 2010. Change in defense mechanisms and coping over the course of short-term dynamic psychotherapy for adjustment disorder. J Clin Psychol. 66:1232–1241.

- Kramer U, Pascual-Leone A, Despland J-N, de Roten Y. 2015. One minute of grief: emotional processing in short-term dynamic psychotherapy for adjustment disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 83:187–198.

- Laugharne J, van der Watt G, Janca A. 2009. It is too early for adjusting the adjustment disorder category. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 22:50–54.

- Leichsenring F, Luyten P, Hilsenroth MJ, Abbass A, Barber JP, Keefe JR, Leweke F, Rabung S, Steinert C. 2015. Psychodynamic therapy meets evidence-based medicine: a systematic review using updated criteria. Lancet Psychiatry. 2:648–660.

- Lorenz L, Bachem RC, Maercker A. 2016. The adjustment disorder–new module 20 as a screening instrument: cluster analysis and cut-off values. Int J Occup Environ Med. 7:215–220.

- Maercker A, Bachem RC, Lorenz L, Moser CT, Berger T. 2015. Adjustment disorders are uniquely suited for ehealth interventions: concept and case study. JMIR Ment Health. 2:e15.

- Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, Cloitre M, Reed GM, van Ommeren M, Humayun A, Jones LM, Kagee A, Llosa AE, et al. 2013. Proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the international classification of Diseases-11. Lancet. 381:1683–1685.

- Maercker A, Einsle F, Kollner V. 2007. Adjustment disorders as stress response syndromes: a new diagnostic concept and its exploration in a medical sample. Psychopathology. 40:135–146.

- Maercker A, Forstmeier S, Pielmaier L, Spangenberg L, Brahler E, Glaesmer H. 2012. Adjustment disorders: prevalence in a representative nationwide survey in Germany. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 47:1745–1752.

- Mahlke CI, Kramer UM, Becker T, Bock T. 2014. Peer support in mental health services. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 27:276–281.

- Maina G, Forner F, Bogetto F. 2005. Randomized controlled trial comparing brief dynamic and supportive therapy with waiting list condition in minor depressive disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 74:43–50.

- Manoranjitham SD, Rajkumar AP, Thangadurai P, Prasad J, Jayakaran R, Jacob KS. 2010. Risk factors for suicide in rural south India. Br J Psychiatry. 196:26–30.

- Manzoni GM, Pagnini F, Castelnuovo G, Molinari E. 2008. Relaxation training for anxiety: a ten-years systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 8:41.

- Markowitz JC, Klerman GL, Perry SW. 1992. Interpersonal psychotherapy of depressed HIV-positive outpatients. Hosp Comm Psychiatry. 43:885–890.

- Mihelich ML. 2000. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing treatment of AD. Dissertation Abstracts International 61:1091.

- Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. 2011. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. The Lancet Oncol. 12:160–174.

- Nardi C, Lichtenberg P, Kaplan Z. 1994. Adjustment disorder of conscripts as a military phobia. Mil Med. 159:612–616.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2009. Depression in Adults. The treatment and management of depression in adults. NICE clinical guideline 90. London (UK): NICE.

- Novo Navarro P, Landin-Romero R, Guardiola-Wanden-Berghe R, Moreno-Alcazar A, Valiente-Gomez A, Lupo W, Garcia F, Fernandez I, Perez V, Amann BL. 2018. 25 years of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): the EMDR therapy protocol, hypotheses of its mechanism of action and a systematic review of its efficacy in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 11(2):101–114.

- Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Deacon BJ. 2010. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 33:557–577.

- Pae C-U. 2015. Why systematic review rather than narrative review?. Psychiatry Investig. 12:417–419.

- Quero S, Moles M, Perez-Ara MA, Botella C, Banos RM. 2012. An online emotional regulation system to deliver homework assignments for treating adjustment disorders. Stud Health Technol Inform. 181:273–277.

- Rebergen DS, Bruinvels DJ, Bezemer PD, van der Beek AJ, van Mechelen W. 2009. Guideline-based care of common mental disorders by occupational physicians (CO-OP study): a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Environ Med. 51:305–312.

- Reed GM, Correia JM, Esparza P, Saxena S, Maj M. 2011. The WPA-WHO global survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes towards mental disorders classification. World Psychiatry. 10:118–131.

- Reschke K. 2011. TAPS Therapieprogramm für Anpassungsstörungen: Ein Programm für kognitiv-behaviorale Intervention bei Anpassungsstörungen und nach kritischen Lebensereignissen. Aachen: Shaker; p. 229. ISBN: 978-3-8440-0217-1.

- Richards DA, Ekers D, McMillan D, Taylor RS, Byford S, Warren FC, Barrett B, Farrand PA, Gilbody S, Kuyken W, et al. 2016. Cost and outcome of behavioural activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 388:871–880.

- Ruesch M, Helmes AW, Bengel J. 2015. Immediate help through group therapy for patients with somatic diseases and depressive or adjustment disorders in outpatient care: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 16:287.

- Schuyler D. 2004. Cognitive therapy for adjustment disorder in cancer patients. Psychiatry. 1:20–23.

- Shah LBI, Klainin-Yobas P, Torres S, Kannusamy P. 2014. Efficacy of psychoeducation and relaxation interventions on stress-related variables in people with mental disorders: a literature review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 28:94–101.

- Skruibis P, Eimontas J, Dovydaitiene M, Mazulyte E, Zelviene P, Kazlauskas E. 2016. Internet-based modular program BADI for adjustment disorder: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 16:264.

- Spiegel D. 2012. Mind matters in cancer survival. Psychooncology. 21:588–593.

- Srivastava M, Talukdar U, Lahan V. 2011. Meditation for the management of adjustment disorder anxiety and depression. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 17:241–245.

- Stenlund T, Ahlgren C, Lindahl B, Burell G, Steinholtz K, Edlund C, Nilsson L, Knutsson A, Birgander LS. 2009. Cognitively oriented behavioral rehabilitation in combination with Qigong for patients on long-term sick leave because of burnout: REST–a randomized clinical trial. Intj Behav Med. 16:294–303.

- Strain JJ, Diefenbacher A. 2008. The adjustment disorders: the conundrums of the diagnoses. Compr Psychiatry. 49:121–130.

- Sundquist J, Lilja A, Palmer K, Memon AA, Wang X, Johansson LM, Sundquist K. 2015. Mindfulness group therapy in primary care patients with depression, anxiety and stress and adjustment disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 206:128–135.

- van der Klink JJL, Blonk RWB, Schene AH, van DFJH. 2003. Reducing long term sickness absence by an activating intervention in adjustment disorders: a cluster randomised controlled design. Occup Environ Med. 60:429–437.

- van Oostrom SH, van Mechelen W, Terluin B, Vet HCW, de Knol DL, Anema JR. 2010. A workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with distress: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 67:596–602.

- van Straten A, Hill J, Richards DA, Cuijpers P. 2015. Stepped care treatment delivery for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 45:231–246.

- Vente W, de Kamphuis JH, Emmelkamp PMG, Blonk RWB. 2008. Individual and group cognitive-behavioral treatment for work-related stress complaints and sickness absence: a randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health Psychol. 13:214–231.

- Willert MV, Thulstrup AM, Bonde JP. 2011. Effects of a stress management intervention on absenteeism and return to work–results from a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health. 37:186–195.