ABSTRACT

Although the role of leadership in school improvement is widely recognized, there is less understanding of what leaders can do to support (and mitigate barriers to) the implementation of mandated educational change. This systematic literature review analyzed findings from 191 relevant primary studies published between 2000 and 2020 and identified four broad themes: developing a reform-ready school climate, comprehensive planning, preparation for implementation, and building capacity. These results offer practical information about malleable school-level factors to which school leaders can attend (before implementing mandated reform) to support the school’s capacity for change.

Introduction

Policymakers worldwide have pressured education systems to improve performance and student outcomes. By-and-large reform efforts have been motivated to ensure access to high-quality education for all (Addonizio & Kearney, Citation2012), develop human capital to advance international competitiveness (e.g., Matsumoto, Citation2019), and improve domestic development and living standards (e.g., Gaziel, Citation2010). In addition, international rankings of educational performance have driven public concerns and policy debates about educational performance and, in some cases, become central to reform efforts (Cheng, Citation2020; Harris & Jones, Citation2017; Niemann, Martens, & Teltemann, Citation2017). Despite noble intentions and the expenditure of vast sums of money, it is widely agreed that, over the last 40 years, most reform efforts have failed (Bryk, Gomez, Grunow, & Lemahieu, Citation2015; Hargreaves, Lieberman, Fullan, & Hopkins, Citation2014; Hickey et al., Citation2022). In some cases, these failures are reflected in aggregated international rankings, which show limited, if not deteriorated, changes (OECD, Citation2019). In others, such as Australia, there are reports of system-wide failures of policy mandates (e.g., Gonski, Citation2019).

The failure of reform efforts across different countries reflects the challenges involved, which usually involves changes across multiple levels within a system. These challenges start at inception, for example, when policies do not recognize what needs to be changed (e.g., Bascia & Hargreaves, Citation2000), treat reform as a recipe for success (Matsumoto, Citation2019), or when policymakers focus on outcomes rather than execution of the idea (Fullan, Citation2010; Murphy, Citation2020). The challenges of reform are compounded by the scale and successive waves of reform (Sahlberg, Citation2018), which, at the school level, are reflected in efforts to implement policies in ways that were not intended (Rigby, Woulfin, & Marz, Citation2016).

Implementation of education reform at the school level is rarely straightforward. For school leaders, the dynamic nature of schools requires leaders to deal with layers of change that can complement or conflict with the reform effort. For example, a single school might introduce a reading program, a school-wide bullying program, a new learning management support platform, and a collaborative inquiry process, all at the same time. The addition of policy demands results in an extra layer of complexity on top of existing change efforts (Hargreaves, Lieberman, Fullan, & Hopkins, Citation2005), daily responsibilities (Pollock & Ryan, Citation2013), and levels of crisis management (Smith & Riley, Citation2012).

The nature of educational change can make policy implementation challenging to navigate. The daily pressures coupled with pressures to implement within a given timeframe can diminish the opportunity for school leaders to consider factors that could enhance the likelihood of success. Therefore, this study examined school-level factors that influence reform success and the concrete actions that school leaders can take to support change efforts before implementation. To achieve this aim, the literature review drew on the rich knowledge base of processes and practices associated with educational change, incorporating the research findings to: 1) examine the attributes (extent and origins) of the research base; and, importantly, 2) analyze the findings related to what school leaders can do to support (and mitigate barriers to) educational change before implementing reform efforts.

Background

This article refers to education reform, educational change, and school improvement. Given that these terms are neither used nor defined consistently in past research, it is worth distinguishing between them. In our review, the term education reform was used to describe system-wide improvement efforts (which included across a district or state) initiated by policymakers, to overcome an issue or challenge (Zajda, Citation2015). Reform efforts are instigated at a macro-level (often political) and involve fundamental changes within the system (Cheng, Citation2020). When talking about reform, we refer to the activities or structural changes often mandated through top-down directives (Fink & Stoll, Citation2005). Although educational change and reform are often used interchangeably, we have distinguished educational change as a process that provides evidence of how reform has impacted, changed, or affected practices or structures.

Finally, we refer to the term school improvement. Arguably, the realization of education reform efforts relies on the successful implementation of policy demands and subsequent [intended] changes (e.g., in practice) at the school level. Therefore, school improvement describes school-level factors and processes that promote school success (e.g., Hopkins, Stringfield, Harris, Stoll, & Mackay, Citation2014; Reynolds et al., Citation2014). School improvement was conceptualized by Jackson (Citation2000) as a “journey” that involves continuous efforts to improve educational performance and student achievement. According to Hallinger and Heck (Citation2011), because schools are at different points in the school improvement journey, they face different challenges.

There has been substantial progress in understanding school improvement. Research has described processes associated with successful change (e.g., Hall & Hord,Citation2020) from various perspectives (Hallinger & Heck, Citation2011). Researchers have identified phases critical to the school improvement process (Hopkins & Reynolds, Citation2001; Hopkins et al., Citation2014) and developed frameworks (Reezigt & Creemers, Citation2005) and models to help explain improved educational performance (Leithwood, Jantzi, & McElheron-Hopkins, Citation2006). Among these models are the effective school improvement model (ESI; Scheerensa & Demeuseb, Citation2005), the dynamic approach to school improvement (DASI; Creemers, Kyriakides, & Antoniou, Citation2013), and the model of school improvement processes (SIP; Leithwood et al., Citation2006). Finally, school improvement research has examined the role of leadership practice (Robinson, Lloyd, & Rowe, Citation2008) and sense-making (Ganon-Shilon & Schechter, Citation2019) during reform implementation.

The pivotal role of school leadership and the complexities school leaders face in implementing the demands of reform is widely acknowledged (e.g., Carrington, Spina, Kimber, Spooner-Lane, & Williams, Citation2022; Ärlestig, Day & Johansson, Citation2016; González-Falcón, García-Rodríguez, Gómez-Hurtado, & Carrasco-Macías, Citation2020; Hallinger & Heck, Citation2011; Hallinger, Citation2018). The introduction of reform requires school leaders to balance internal pressures, such as teachers’ needs (Brezicha, Bergmark, & Mitra, Citation2015) and the reality of the context (Ganon-Shilon & Schechter, Citation2019), with external pressures (e.g., expectations and accountability) while simultaneously making sense of the reform requirements and translating these requirements in school plans and to teachers.

Despite the substantial progress in understanding the processes and principles essential to successful school improvement, implementing mandated reform at the school level remains “messy” (Gavin & Stacy, Citation2022). First, differences between the processes and factors identified in school improvement models (including whether they are included and at what stage of the process) and whether these remain relevant during mandated reform efforts are not always clear. Second, in many cases, the focus on alterable school-level factors that promote change efforts before implementing policy demands remains limited. Therefore, the review reported in this article sought to understand better factors that support or hinder the success of these change efforts that can be addressed by leadership before implementing the change effort.

Our review drew on a change management perspective (Cameron & Green, Citation2004), allowing us to consider factors related to relationships, understandings, and processes. A change management perspective helped us determine factors influenced by leaders that affect the success of reform efforts. Although there are many change management models (Todnem, Citation2005), we recognize that there is no one widely-accepted, clear, and practical approach to change management; therefore, using one model is unlikely to provide a complete picture of the process. Using a change management perspective allowed us to examine more pragmatic factors that support or hinder educational change before implementing policy requirements.

Arguably, more than effective change management (e.g., Gurr & Drysdale, Citation2012) is required to implement reform successfully. Therefore, we also drew on the field of policy implementation, which commenced with the work of Pressman and Wildavsky (Citation1973), to help understand factors that support or hinder reform before implementation across an organization. According to Cheng (Citation2020) factors related to implementation have been classified into four system levels (macro, meso, site, and operational levels). Different system levels are seated in contexts with existing values, interests, rules, and structures that shape policy interpretation (Bullock, Lavis, Wilson, Mulvale, & Miatello, Citation2021). According to Honig (Citation2006), implementation is influenced by the interactions of three elements: policy, people, and places across time. The first, policy, is related to the design (e.g., mandates, capacity building, etc.), intended goals, and breadth, depth, and scale of the intent, all of which affect the interpretation and subsequent implementation. The second, people, is related to those responsible for implementation, and who inevitably interpret and shape the reform demands based on the context or situation and their own experience, capacity. The third, places across time, refers to the external and the organizational contexts in which implementation occurs. These three elements work to shape implementation both separately and as they interact with each other.

Our review reports factors that occur at the site (school) level of the system. Given that the focus of our study was to examine factors that school leaders can change, we did not include factors related to policy, which, by and large, are not within the control of school members (Note that a focus on policy is provided in a sister paper, McLure & Aldridge, Citationin press). Therefore, we examined two elements that influence implementation (Honig, Citation2006); people and places across time. Our focus on “people” was related to school leadership, who act “as a catalyst and agent of support” (Hallinger & Heck, Citation2011, p. 4). The actions of school leaders in response to policy are shaped by their own experiences as well as the internal and external context of the school, which, in turn, influences or shapes what the reform looks like in practice (Mehan, Hubbard, & Datnow, Citation2010). Our focus on “place” helped to make sense of the organizational context, culture, or climate and how this shapes the actions of leaders and others as they implement reform (Datnow & Stringfield, Citation2000).

Considering the complex nature of implementing reform requirements, the purpose of our review was to provide a comprehensive and rigorous summary of what researchers have learned over the past 20 years. Although our paper delineates factors (based on our findings) that leaders can address before implementing reform, we acknowledge that implementation is not linear (Datnow & Stringfield, Citation2000).

Past Reviews

This section examines past literature reviews (published since 2000) to provide pertinent background information and clarify our study’s distinctiveness. Specifically, these reviews:

involved studies carried out in a single country.

were related to a specific reform type.

described the type or effectiveness of specific reform or change efforts.

Past reviews of change efforts that include barriers and supports to reform success are limited and have generally focused on efforts in one country or region (e.g., Honig & Rainey, Citation2012; Tang, Lu, & Hallinger, Citation2014), specific contexts (e.g., Datnow, Lasky, Stringfield, & Teddlie, Citation2005; Guhn, Citation2009), or one type of initiative (Honig & Rainey, Citation2012). As described below, the review reported in this paper extended past reviews by drawing on a wide range of research related to different reform types carried out in different countries.

Most past reviews have focused on research related to specific reforms or successive reforms in one country or region (e.g., Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013; Honig & Rainey, Citation2012; Tang et al., Citation2014). For instance, Potter, Reynolds, and Chapman (Citation2002) review examined school improvement initiatives over three waves (15 years) of reform in the United Kingdom (UK). provides an overview of these reviews, including the scope of the study, the key results relevant to the present study, and the areas identified for future work.

Table 1. Analysis of recent reviews of literature related to reform efforts in a single country.

Although valuable in their own right, as suggested by (Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013), the generalizability of the findings to other countries and contexts could be limited. Our review extended these past studies by reviewing the literature on studies carried out worldwide, thereby generating further knowledge about what facilitates reform success.

In other literature reviews, the authors limited the scope to reform initiatives in specific contexts (e.g., Datnow et al., Citation2005; Guhn, Citation2009) or from a particular angle (e.g., Mizala and Schneider’s (Citation2014) review related to reform and teacher pay incentives). In another case, the educational reform and school improvement initiatives were reviewed by Levin (Citation2010) in broad terms rather than specific aspects that hindered or supported educational change efforts. provides an overview of reviews of literature related to a particular initiative in specific contexts.

Table 2. Analysis of recent reviews of literature related to a particular initiative or reform type.

These reviews provide important information for the setting, context, or reform type. However, none focuses on factors that support or hinder change across a broad range of settings. The review reported in this paper extended these past reviews in two ways. First, our review identified factors applicable to the school level and within the control of school leaders. Second, our review expanded past studies by using exclusion/exclusion criteria that ensured that we included studies of different contexts, perspectives, and reform types were considered.

Other reviews have described reform efforts or the results or effectiveness of reform. In some cases, these were more opinion pieces than literature reviews (e.g., Castellano, Stringfield, & Stone, Citation2016; Kim, Citation2005; Lo, Hung, & Liu, Citation2002). In other cases, the review summarized the author’s readings on why changes were problematic (e.g., Goldenberg, Citation2003). Our study departed from these previous reviews by involving the rigor of a systematic literature review.

Examination of past reviews highlights their usefulness and, in some cases, the detail of a particular focus on educational reform. However, our review is distinctive as no other reviews synthesizing findings from countries worldwide that focus on factors that facilitate (or hinder) change efforts before implementation at the school level. Further, to our knowledge, no systematic literature review has been used to review the findings of empirical studies from reform efforts carried out globally. It is also noted that none of these past reviews focused on factors that occur at the school level before implementing reform, that is, factors that school leaders can (and perhaps should) attend to before introducing educational change. Our study helps to fill this gap in the literature.

Methods

Our systematic literature review was focused on studies that reported factors that facilitate or hinder the implementation of mandated education reform efforts. This systematic literature review was carried out using the steps outlined in the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009). The steps and procedures employed to establish eligibility, retrieve and screen the articles, and analyze the data are reported below.

Eligibility Criteria

We were interested in factors that occur at all stages of mandated reform and all system levels (macro, meso, site, and operational levels). The authors decided the inclusion and exclusion criteria collaboratively to ensure a wide range of studies. provides an overview of the criteria used to determine the eligibility of the studies.

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to guide the selection of articles for analyses.

Search Strategy

Potentially-relevant literature was searched using electronic databases between May and October 2020, including ProQuest ERIC, Scopus, Sage Journals, and Web of Science. The search involved keywords (in the title, abstract, or keywords) agreed upon by both authors. The search words were: school change; school reform; school improvement; educational change; or educational improvement as well as factors affect(ing); affect(ing); impact; inhibit; barrier; support; affordance; or effective as well as primary school; secondary school; middle school; or school.

Data Screening and Extraction

Data screening and extraction were carried out in three stages. In the first stage, search results (n=2560) were imported into CovidenceT M (Covidence systematic review software, Citation2019), and the duplicates (267 articles) were removed. The PRISMA flow diagram for study selection is presented in . Both authors then independently checked the titles and abstracts to determine whether they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (outlined above). The authors refined the inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure only articles of interest were retained during this stage. For example, a decision was made to exclude studies that focused on political factors influencing the success of change efforts. In another example, a decision was made to include studies that reported reform efforts mandated at a state or district level as well as at a national level.

In the second stage, the authors independently assessed the eligibility of the screened studies using the full-text version. The authors worked closely to decide whether articles were to be included. In cases where conflicts about exclusion/inclusion arose (approximately 5%), the authors worked together to resolve them by discussing the reasons for exclusion/inclusion against the criteria.

In the final stage, the authors extracted data from the included manuscripts, including names of the authors and institutions, publication date, country and setting of the study, study design, type of data collected, study population, intervention, and barriers and supports for change. The authors also evaluated the quality of the evidence presented. Once again, the authors discussed conflicts that arose. Note that a few articles were returned to the previous stage and excluded based on data quality and inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram in outlines these stages and the number of articles retained at each.

A total of 294 articles published between 2000 and 2020 met the eligibility criteria. The authors extracted data from these studies, entering it into an Excel spreadsheet for thematic analysis.

Data Analysis

As a first step, the authors organized the retained articles’ attributes, and the frequencies associated with these categories were compared. Specifically, we examined: the publication dates, the origins of the studies (geographically); the research designs used; and the setting of the study school (e.g., primary school).

Our analysis involved a multi-stage thematic analysis approach to identify themes (and sub-themes) related to barriers and supports that affect school change efforts (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, Citation2017). During the initial analysis, categories were identified as the findings of the studies were examined. The findings for each study were placed under existing categories, or new categories were developed as needed. Once complete, the authors cross-checked the data and analyzed the categories for themes. This process was iterative in that it involved going back over the categories and related findings to allow the authors to gather related categories into themes and identify sub-themes within them. This process continued until the analysis achieved saturation (that is, no more themes arose (Bryman, Citation2012)).

Given the size of the review, the authors were forced to divide the findings into parts to allow reporting. Four parts were delineated, each of which was aligned with different phases of the reform: initiating educational change (system-level factors); preparation for change (school-level factors); implementing and sustaining reform efforts (school- and system-level factors); and factors related to teachers’ attitudes. This organization is, by-and-large, consistent with Fullan’s (Citation2007) phases of initiation, implementation, and institutionalization.

Given the non-linear nature of reform, the separation of themes was not always clear. For example, factors related to establishing a collaborative environment were influential both as a pre-condition to change and during the implementation of a change effort. In these cases, the authors decided where to report the themes based on where they would benefit the reader and their congruency with other themes in the paper.

This paper reports the supports and barriers at the school level before reform implementation. To be included in this paper, themes were required to describe factors that:

occur at the school level;

can be addressed before the introduction of the reform; and

were in the control of (malleable by) the school leadership.

A total of 191 articles published between 2000 and 2020 met the eligibility criteria. Identification of themes and subthemes was accompanied by a tally of frequencies with which the reviewed studies showed evidence of the factors. Although the statistical limitations of tallying have been reported (see, for example, Card, Citation2012; Cooper, Patall, & Lindsay, Citation2013), this analysis provided a useful descriptive tool within a thematic review of literature, particularly given that meta-analysis was not possible (Rodgers et al., Citation2009).

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

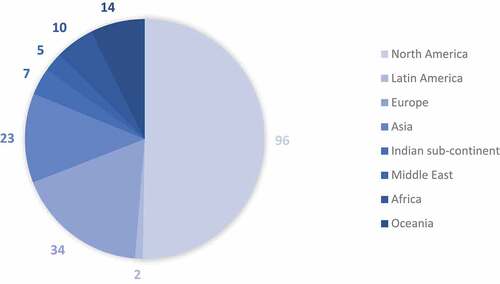

The characteristics of the 191 studies that met the eligibility criteria are presented in . The 191 articles reported studies carried out in more than 43 countries, including four studies that compared two or more countries. Ninety-six (50%) of these were carried out in North America. Most of the existing literature (75%) originated from developed countries, most of which were carried out in the US (45%). provides a breakdown of the number of studies by geographical region.

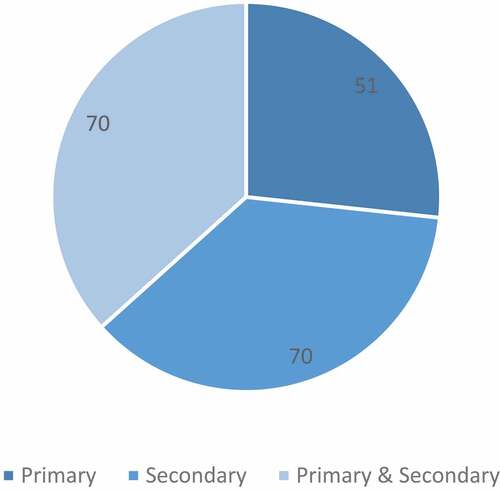

The studies examined reform implementation in both the primary (elementary) and secondary (middle and high school) settings. provides a breakdown of the number of studies by educational level.

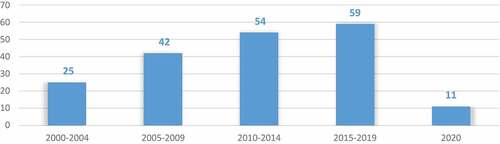

The number of eligible studies increased over the 20 years. In the number of studies is broken by the year of publication.

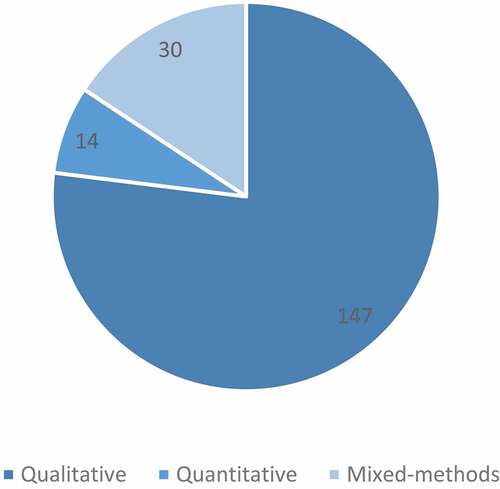

More than 75% of studies reported on qualitative data. See for a breakdown of the number of studies by the research design.

The reforms efforts reported in studies were many and varied and included, whole-school improvement reforms related to No Child Left Behind (NCLB), Comprehensive School Reform (CSR), Science Education reforms, reforms that mandated inclusive practices, small schools reform, system-wide introduction of activity-based learning, English language policy reform and Every Child Matters Reform.

Findings of the Thematic Analysis

Thematic analysis of the findings reported in the studies allowed us to identify factors that facilitate or hinder the reform efforts. We acknowledge that these findings are limited by the level of abstraction required to distil each theme and were cognizant of oversimplifying answers to the “how” question (e.g., Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation1998). However, the findings help to unravel factors that facilitate or hinder this pre-implementation stage as school leaders prepare for change. Analysis of the results of studies reported in 191 articles found themes related to: the school climate (or pre-conditions); planning for change; preparing for change; and capacity building. These themes, and the associated sub-themes, are described below. A full list of the studies associated with each sub-theme is provided in the Appendix.

School Climate

Analysis of the articles indicated that the terms school climate and school culture were not used consistently and were sometimes used interchangeably. In our study, we differentiated between the two. Whereas the culture of an organization was viewed as the pattern of shared assumptions (Schein, Citation2012), the school’s climate was the patterns of stakeholders’ experiences of the organizational culture in terms of perceptions of the quality and character of school life, including the norms, behaviors, and actions (Aldridge & Fraser, Citation2018).

Our findings suggest that reform implementation is supported by four aspects of the school climate: a shared vision; high expectations; positive relationships with high levels of trust; and a collaborative environment. Each of these sub-themes is reported in turn.

Shared Vision

Fourteen studies suggested that when school leaders fail to communicate a shared vision, the school change efforts are compromised (Lee & Lo, Citation2007). These studies indicate that when a shared vision is not communicated effectively, stakeholders lack a clear direction for change and a shared philosophy that underpins the reform.

On the other hand, 39 studies suggested that schools with a clear, shared vision are more likely to succeed with the change effort. These studies indicate that a shared vision leads to greater trust between leadership and staff, more coherence within the reform effort, and more effective implementation (Wetherill & Applefield, Citation2005). Further, when leaders communicated a clear shared vision, they were more likely to generate a commitment to the reform effort and mitigate anti-reform groups (Copland, Citation2003). Furthermore, studies found that when the vision is co-constructed, a successful introduction is more likely in communities with different values or goals (Holmes, Clement, & Albright, Citation2013).

The studies suggest some core features required in a shared vision. First, there needs to be a collective understanding of the vision as well as how the shared philosophy that underpins the vision will supports the reform (Wikeley & Murillo, Citation2005). Second, the vision needs to be clear about the direction of change and fit with reform efforts (Edwards, Citation2012). Finally, the commitment of school leaders to the vision needs to be authentic (Nelson, Fairchild, Grossenbacher, & Landers, Citation2007), and leaders need to be personally involved in sharing it (Causton-Theoharis, Theoharis, Bull, Cosier, & Dempf-Aldrich, Citation2011).

High Expections

Shared values and beliefs in a school include high expectations, a lack of which can indicate a diminished school climate. Seventeen studies suggest that teachers’ expectations can hinder reform efforts. For instance, reform efforts are likely to be impeded in schools where teachers’ beliefs about students come from a deficit perspective or lack of faith in students’ ability to achieve (see Galloway, Callin, James, Vimegnon, & McCall, Citation2019). For example, when teachers believe that student behavior will cause problems (e.g., difficulties managing overexcited behavior due to reform implementation) or students’ lack of ability, the reform effort’s success will be limited. Conversely, 11 studies reported that reform efforts are more likely to succeed when there is a culture of high expectations within the school. These studies report that change efforts were more likely to succeed in schools with an expanded view of student success in which teachers talked of capabilities rather than deficits and held beliefs that students can achieve (e.g., Demerath, Citation2018; Hamilton, Citation2014).

Positive, Trusting Relationships

A significant barrier to reform efforts, identified in 24 studies, was the relationship between staff and between leaders and staff. These studies report that the reform efforts were undermined in schools with a lack of respect between staff members or where teachers feel threatened (McDermott, Citation2006; Wettlaufer & Sider, Citation2019). Studies found that negative relationships between leaders and teachers were likely to occur when teachers felt rushed, pressured, or overwhelmed. Further, these negative relationships were more likely to occur in schools with poor communication to build relationships (e.g., Rogers, Citation2007).

Forty-two studies report that building positive, caring relationships with teachers will support reform efforts (e.g., Nguyen & Hunter, Citation2018). Thirty-five studies report that building relational trust (both between staff and between leadership and staff) is important to reform success. Developing a trustful school climate enhances psychological safety, making teachers more willing to engage in behaviors that support school improvement, such as sharing failures and challenges, speaking out, and trying innovative ideas (e.g., Edwards, Citation2012). Further, a relational trust allows leaders to communicate reform ideas more effectively (Datnow & Castellano, Citation2001). Conversely, studies reported that low levels of trust among staff (either of each other or the principal) were significant barriers to reform efforts (Wettlaufer & Sider, Citation2019).

Studies suggest that building trusting relationships involves respect for staff, effective communication (Holmes et al., Citation2013), and opportunities for staff members to experience their peers’ competence, sincerity, and reliability (Kershner & McQuillan, Citation2016). Leadership characteristics helpful in developing positive relationships between teachers and leadership include being empathetic, adopting a non-threatening leadership style, and situating themselves as learners within the school. Notably, building meaningful levels of trust takes time (which, in some studies, was viewed by leaders as problematic), and it requires human skills that enable leaders to effectively lead and work with teachers (Holmes et al., Citation2013).

Although most of the studies focused on the relationships between staff and between staff and leadership, other studies examined the importance of trust between staff and students (Biddle, Citation2017) and between school staff and staff at the district, system, and government levels (e.g., Bashir & Ul-Haq, Citation2019). Overall, the findings suggest that building positive relationships and developing trust between stakeholders within the school are essential ingredients for the success of reform efforts.

A Collaborative Environment

Numerous studies highlight the importance of cultivating a collaborative environment to support the success of reform efforts (52 studies). Collaborative environments supported reform efforts by encouraging teacher autonomy, innovation, and shared decision-making (e.g., García-Martínez, Pedro, Pérez-Ferra, & Ubago-Jiménez, Citation2020; Jorgensen, Agergaard, Stylianou, & Troelsen, Citation2020) and encouraging learning across groups and subsystems (see Gunter et al., Citation2007). Conversely, 18 studies report that a lack of collaboration (between leadership and staff or between staff) was a barrier to successful reform.

Collaborative environments are characterized by high levels of trust, shared values and decision-making, working effectively as a team, and commitment to co-developing teaching practice (see Barakat & Maslin-Ostrowski, Citation2019; Härkki, Vartiainen, Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, & Hakkarainen, Citation2021).Footnote1 Studies reported a range of collaborative activities or approaches that supported reform efforts, including collaborative inquiry (e.g., Geijsel, Krüger, & Sleegers, Citation2010), professional collaborative learning and dialogue (e.g., Johnson, Citation2007), teacher professional communities (e.g., Levine, Citation2011) and, the most widely-reported, professional learning communities (PLC) (e.g., Edwards, Citation2012). Although PLCs are a structure and do not ensure collaborative action, many studies examined the use of PLCs as a tool for capacity building. The findings suggest that, when implemented effectively, they encourage a culture of collegiality that provides a safe space to share ideas and practices (e.g., Saito, Khong, & Tsukui, Citation2012).

Regardless of the method used to develop a collaborative environment, the studies emphasized the importance of peer collaboration to support reform efforts. Further, the advantages of developing a collaborative environment are limited when the participants do not share norms or visions or are forced to participate. Notably, reform efforts are hampered when schools lack a collaborative environment between leadership/coaches and staff or between teachers (e.g., Levine, Citation2011).

Planning for Change

The second overarching theme suggests that successful reform efforts involve the development of a comprehensive plan to guide implementation. Further, studies report that the plans need to be data-informed and include analysis of the context and reflection on the strategies to be implemented.

Comprehensive School Plan

Thirty-three studies reported that developing a comprehensive school plan supported the success of reform efforts. The most effective plans linked the school’s needs and context with strategies and vision (Nunnery, Ross, & Bol, Citation2008). Findings indicate that planning for change needs to include a comprehensive school plan that involves analysis and reflection.

The most effective plans collaboratively engaged stakeholders in their development (Gonzales, Bickmore, & Roberts, Citation2020) and considered accountability alongside a clear understanding of how and who will evaluate the school plan (Hilliard, Citation2009). Notably, the development of the school plan needs to involve systematic self-evaluations to identify weaknesses and professional learning needs that drive clear, realistic short- and long-term goals (e.g., Caputo & Rastelli, Citation2014). Further, positive outcomes were reported when plans had concrete steps and evidence-based strategies. Importantly, plans need to include measures to address gaps in professional development that may hamper reform efforts (Borko, Elliott, & Uchiyama, Citation2002).

Notably, 21 studies found that reform efforts were hampered when plans were superficial or focused on short-term goals or first-order change (e.g., Dueppen & Hughes, Citation2018; Erlichson, Citation2005). Further, change efforts were hampered when leaders planned to implement easy and least disruptive changes (while ignoring deeper ones).

Analysis and Reflection for Planning

Five studies found that when plans lacked analysis or opportunities for considering and reflecting on the strategies to be involved, they limited reform success. For instance, when plans are rushed and solutions are put forward without analyzing the gaps or considering the underlying causes of problems, they are more likely to fail (e.g., Dueppen & Hughes, Citation2018).

Conversely, six studies found that reform efforts were supported when those responsible for the planning took time to consider and analyze the context of the change (Caputo & Rastelli, Citation2014). These studies suggest that successful school plans involve systematically analyzing the school’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats to understand where changes are needed (e.g., Strunk, Marsh, Bush-Mecenas, & Duque, Citation2016). Further, this analysis is strengthened when time is provided for observations and feedback from stakeholders within the school. Some studies indicated that using an evaluation model can be helpful (e.g., Schildkamp & Visscher, Citation2010).

Preparing for Implementation

Ten studies indicated that reform efforts were unlikely to be sustainable if there was insufficient preparation for implementation. In preparing for implementation, studies suggest that several key considerations will support the success of reform efforts. Findings suggest that preparation for a reform effort needs to ensure that the goals of the reform are communicated and the structures of the school are adapted (Evans & Cowell, Citation2013).

Adapting School Structure

Studies suggest that time is needed to consider how the leaders adapt the school routines to provide time for processes supporting implementation. In particular, studies report that school leaders should provide time for collaboration between teachers (Johnson, Citation2007; Marynowski, Mombourquette, & Slomp, Citation2019), regular meetings between teachers (Johnson & Marx, Citation2009), and for leaders to engage in leadership activities (Klar, Huggins, Hammonds, & Buskey, Citation2016).

To avoid the element of surprise, school leaders need to flag the changes with staff and, as reported below, provide staff with a deep understanding of the reform before implementation (Nguyen & Hunter, Citation2018).

Communicating the Goals

Ten studies suggest that part of organizational readiness for reform involves clear communication of the goals. These studies report that such communication requires careful planning to ensure a clear understanding of the goals, garner commitment, and create a shared vision of the reform (Bubb & Earley, Citation2009; Huang & Asghar, Citation2018). Fourteen studies suggest that a lack of clear, reliable communication about the goals of the reform hampered change efforts. In many cases, these studies report that a lack of effective communication led to a limited agreement about common meanings and different interpretations of the reform (e.g., Naicker & Mestry, Citation2016).

Thirty-five studies found that the success of reform efforts was enhanced when school leadership effectively communicated the goals before implementation. The studies identified that this communication needs to relay information about the reform and its implementation. Further, school leaders need to consider how goals will be communicated effectively to all areas of the school and meet the needs of different members of the school community (Hannay, Ben Jafaar, & Earl, Citation2013).

Studies report that communication needs to be purposeful, consistent, and transparent (Hollingworth, Olsen, Asikin-Garmager, & Winn, Citation2018). Importantly, communication should build shared meaning (language around the reform), motivate staff and other stakeholders, and provide a solid moral purpose for its implementation (e.g., Tran, Hallinger, & Truong, Citation2018).

Some studies reported that principals with strong communication skills support the longevity of reform efforts (Finnigan, Citation2011). These leaders are clear about the objectives and goals of the reform and provide teachers with a more holistic understanding of the reform (rather than fragmented).

Building Capacity

The final theme suggests that change efforts are more likely to be successful if leaders ensure that staff members have a deep understanding of the requirements of the reform and build capacity in staff to model practice and mentor others.

Ensuring Understanding of the Reform

Twenty-two studies reported that a significant barrier was a lack of understanding of the reform (on the part of the district administrators/teachers/ principal/ school administrators/ board/new teachers). For instance, in schools with limited guidelines about how the reform should look, reform efforts were likely to fail (e.g., Main, Citation2009). Teachers felt overwhelmed in schools with insufficient understanding of the reform before implementation (e.g., Clement, Citation2014).

Conversely, studies suggest that when leadership, coordinators, and teachers clearly understand the reform, the change effort is more likely to succeed (Lane & Gracia, Citation2005; Lundberg, Citation2019). The studies report the importance of appropriately targeted professional learning, including induction workshops and teacher leadership training (middle leaders) (e.g., Bishop, Berryman, Wearmouth, & Peter, Citation2012; Van Der Voort & Wood, Citation2014). Notably, when the quality of the professional development is inadequate (e.g., does not teach techniques) or does not provide clarity about specifics, reform efforts are hampered (Ham, Citation2020; Ham & Dekkers, Citation2019).

Studies also suggest that the introduction of reform is enhanced when leadership finds ways to support feelings of empowerment in staff (Lee & Lo, Citation2007). The findings indicate that carefully tailored professional learning opportunities (professional growth), such as professional exchange opportunities to share practice within and outside of schools, and empower teachers in the process (e.g., Li, Citation2017).

Building Capacity to Model Practice and Mentor Teachers

Thirteen studies suggest a barrier to reform success is the lack of capacity within and between schools to model practice and mentor teachers. To counter this, studies have found that small-scale pilots within schools help to overcome this.

Small-scale pilots support reform success in two ways. First, the pilot allows schools to build capacity within the staff to model practice and act as mentors. Studies suggest that to implement changes effectively; staff members require explicit teaching or modeling of new practices, access to practical strategies, and simple steps to clarify how the reform is translated into observable practice (Main, Citation2009). Further, when practices related to the reform are already present in the school, the reform effort is more likely to succeed (e.g., Cave, Citation2011). Therefore, small-scale pilots build school capacity by providing teachers who can share and model practice (Li, Citation2017).

Second, small-scale pilots build confidence in the reform by providing positive experiences (including evidence of success). Studies suggest that, even when teachers are committed, the effort is difficult to justify and loses momentum when they lack evidence of success (in terms of improvement (Datnow, Citation2005)). Therefore, using a carefully selected group of enthusiastic staff who care about the reform to pilot implementations of the change before a whole-school effort (Li, Citation2017) can build confidence and buy-in for the reform (Copland, Citation2003). By generating positive experiences with the reform, which teachers present to others, the success of upscaling the implementation is likely to be improved (Li, Citation2017).

Discussion

Between 2000 and 2020, 191 studies reported factors that hinder or support mandated reform efforts before implementing them in schools. The articles reported a wide range of studies with different objectives, methodologies, and theoretical/conceptual frameworks. In this respect, the studies examined reform efforts from various perspectives. In providing this discussion, we acknowledge the complexity of educational change/improvement and the challenges school leaders face in making this a reality. Our intention is not to over-simplify the nature of change and the associated challenges but to provide an overview of the findings in light of past research and practical recommendations.

Analyses of the results reported in the studies found four overarching factors that support success if attended to before implementation: developing reform-ready school climates, planning for change, preparing for and coordinating implementation, and building capacity. The findings for each are discussed below.

School Climate

First, evidence from our review indicates that the school climate or organizational conditions could moderate a school’s capacity to improve. Hallinger (Citation2018) suggests that the context of the school, and the normative ways school members interact, think, and respond to change, will impact not only school improvement but also the actions of school leaders. Therefore, in considering the following discussion, it is important to note that the strategies and actions of school leaders in schools with a positive school climate will differ from those in schools that do not.

Our results suggest that establishing a school climate with a clear, shared vision, high expectations for success (for both student and reform effort), positive, trusting relationships between staff and between staff and leadership, and a collaborative environment will improve the capacity of the school to change. Past reviews also report that positive school climates reduce resistance to change (Potter et al., Citation2002) and improve teachers’ efficacy of the change strategy (Goldenberg, Citation2003). Conversely, when there is a diminished school climate, change efforts are likely to be compromised (James et al., Citation2016).

These findings make sense in light of Lewin’s (Citation1936) psychological field theory, which purports that behavior is the function of a person’s interaction with the environment. Perceptions of the school climate (the prevailing norms, values, and attitudes formed over time) shape school members’ reactions toward and implementing reform (Bridwell-Mitchell, Citation2015). Given that school-level factors are distinctly different for successful and failing schools (Jarl, Andersson, & Blossing, Citation2021) and account for variations in how innovations are implemented (Pesonen et al, Citation2015), these findings support the need to develop an improvement culture (Reezigt & Creemer, Citation2005).

Our finding that school climates support reform implementation (e.g., Bulach & Malone, Citation1994; Fidan & Oztürk, Citation2015; Ramberg, Citation2014) and enhance a school’s capacity for change (Hopkins et al., Citation2014) has important implications. For policymakers, the finding suggests that if variations in school climate are discounted, the risk of failure could be increased. Accordingly, if policymakers understand the mediating effects of school climate on reform success (as suggested by Hopkins et al., Citation2014), policies could be leveraged to include changes in school climate factors. Further, the recognition that developing reform-ready school climates requires social change (Halpin, Citation1967), which occurs at a slow rate, suggests that timeframes for reform need to take this into account (Hopkins et al., Citation2014)

Our finding that change efforts are limited in schools with diminished school climates is consistent with past research (e.g., Day et al., Citation2010; Leithwood et al., Citation2010) and reflected in school improvement models which seek to address school-level factors as part of the process (e.g., DASI; Leithwood et al., Citation2006). If, as Hallinger and Heck (Citation2011) suggest, school improvement is a journey, our findings suggest that developing a positive school climate needs to occur before the journey begins. Accordingly, leaders need to establish a reform-ready school climate to improve the school’s capacity for educational change (as suggested in Hopkins et al.’s (Citation2014) five-phase process).

Comprehensive School Planning

Second, evidence from our review suggests that comprehensive school planning supports reform success. This finding might appear tautological; however, when plans lack self-evaluation and analysis (to inform decisions) or include superficial or first-order solutions, they hinder change efforts, and the finding becomes important. Studies of reforms introduced in China (Tang et al., Citation2014) and the UK (Potter et al., Citation2002) noted superficial changes being made to give the appearance of change or official adoption of strategies that were never actually implemented.

The need for comprehensive school planning is consistent with goal-setting theory, which suggests that goals affect action (Ryan, Citation1970). The need for comprehensive school plans supports existing models of school improvement (e.g., DASI; Creemers et al., Citation2013; Leithwood et al., Citation2006), in particular those that promote evidence-based planning as a critical step in the process (e.g., the synoptic planning stage of Sheerens and Demeuse’s model for school improvement). Our findings, related to elements of an effective plan (such as self-evaluation), are consistent with past research (e.g., Fernandez, Citation2011). Further, they are reflected in school improvement processes that include a framework for action that involves an audit, goal or priority setting, timing, responsibilities for actions, and considerations for evaluation of success (e.g., Leithwood et al., Citation2006). Formulating improvement plans are not new to schools; however, our findings suggest that developing effective school improvement plans is still a challenge that needs to be addressed (e.g., Day et al., Citation2010; Hallinger & Heck, Citation2011).

Preparation Prior to Implementation

Third, evidence from our review suggests that to enhance reform success, leaders need to consider how they will communicate clear goals and a shared vision for change and establish structural features.

First, reform efforts are more successful if clear goals and a shared vision for change are established before implementation. This finding is consistent with collective sense-making, which is based on shared beliefs, values, and assumptions that operate at a subconscious level. The shared beliefs generated through clear goals and shared vision influence how individuals behave and evaluate their actions (Marz & Kelchtermans, Citation2013). This finding is important given that, when confronted with change, teachers’ are sometimes forced to question their professional identity (Kelchtermans, Citation2005), which can make their reactions emotional (Day & Lee, Citation2011). This result also supports the significance of a positive school climate which could interact and influence the extent to which leaders can accomplish this task. Finally, this finding suggests that improving pedagogical knowledge alone may not have the desired effect if leaders do not build a compelling case for change and consider teachers’ attitudes, feelings and beliefs. Our findings suggest that communicating clear goals and a shared vision will influence how school members react to, shape, and make sense of reform.

Second, our findings suggest that reform efforts are more likely to be successful when leaders establish the necessary structural features (including routines and scheduling). These findings have significance when viewed through an organizational learning lens that highlights the need for a collective endeavor involving shared interactions (Hanson, Citation2001). Through this lens, the findings suggest that structural features, such as schedules and routines, promote collective learning (Argyris & Schon, Citation1996) by providing opportunities for meetings, collaboration or peer observations, or interdependent teaching roles (Spillane & Louis, Citation2002), such as co-teaching, or peer coaching. Conversely, when leaders fail to change routines or fall back on existing routines that may have worked in the past, “they become forces for stability rather than change” (Hanson, Citation2001, p. 648) that can disrupt educational change. These findings suggest that structural features of the school (routines, schedules, meetings), alongside a positive school climate, are important pre-conditions of reform-ready schools (Spillane & Louis, Citation2002).

Building Capacity

Finally, our review suggests that reform implementation is hindered when school staff lack understanding or experience in the reform or there is a lack of capacity within (and across schools) to model practices and mentor teachers. First, our findings suggest that when teachers have a deep understanding of the reform, the success of implementation is enhanced. Given that failure of mandated reform efforts has been attributed, in part at least, to a lack of fidelity in implementation, it makes sense that successful implementation requires that leaders and teaching staff need a deep understanding of the reform requirements The task of interpreting, translating and enacting the requirements of policies, is influenced by an individual’s personal system which acts as a lens or filter through which meaning is made of the reform requirements. According to Kelchtermans (Citation2009) personal interpretative framework, personal systems are made up of knowledge, beliefs, and perceptions (including motivations and feelings) of their work. These findings suggest that understanding reform requirements are far from straightforward (Fullan, Citation2001b) and involves considerations about how best to change beliefs and practices.

Our findings suggest that small-scale pilots of a change effort generate enthusiasm and build the capacity required for staff to mentor others and model and share practice. Of note is that the use of small-scale pilots is reflected in improvement models that emphasize cyclical improvement processes (such as ESI, Scheerens & Demeuse) and disciplined inquiry (Bryk et al., Citation2015). Further, these findings are consistent with work related to organizational development (Aikin, Citation1942), which focuses on adaptability to change (e.g., Sarason, Citation1982; Senge, Citation2014) and organizational learning, such as Argyris and Schon’s (Citation1978) double-loop model. The use of small-scale pilots provides opportunities for schools to learn from the experience of implementation and adapt processes before expanding. Importantly, our findings suggest that small-scale pilots provide valuable learning opportunities, build capacity within (and across) schools, and generate enthusiasm.

Our findings generally support the means to developing schools as learning organizations. Our findings support early research in which individual learning is emphasized as “agents” for organizations to learn (Argyris & Schon, Citation1978). However, our findings also support that organizational learning is more than the sum of individual learning. In particular, our findings related to school climate support shifting from individual learning to collective learning (e.g., double-loop learning as described by Argyris and Schon, Citation1978), which relies on relationships and interactions between individuals. Our findings also support a systems view of organizational learning (Argyris & Schon, Citation1978; Senge, Citation1990), which considers the context, and the values and behaviors of stakeholders within a school. These views help individuals make sense of unfamiliar ideas or events and predict how they will react. Finally, our findings suggest that beliefs about teaching practices that have produced reasonable results are unlikely to be abandoned by teachers. Therefore, successful reform efforts could be as much about unlearning as they are about learning (Wang & Ahmed, Citation2003).

Although beyond the scope of this study, the findings imply the need for leaders to understand individual learning and examine what constitutes professional learning and the effectiveness of different types of professional learning. Of note, is that models of professional development (e.g., Clarke & Hollingsworth’s, Citation2002; Desimone, Citation2009; Guskey, Citation2002), school reform (Creemers & Kyriakides, Citation2008); and leadership and school improvement (Louis, Leithwood, Wahlstrom, & Anderson, Citation2010), are available. However, future research might consider building on insights provided in these models to develop a framework to guide professional learning, organizational learning, and reform.

Our systematic literature review supports arguments that the failure of education reform is more complex than mere mismanagement (e.g., Bascia & Hargreaves, Citation2013). As such, it contributes to the existing literature by highlighting factors that leadership can address before implementing a mandated reform effort. As such, our findings provide important implications for system and school leaders, which are outlined here and addressed below. From a system-level perspective, our review supports that schools face different challenges depending on their point in the school improvement journey (Hallinger & Heck, Citation2011). Therefore, policymakers may need to alter their stance and view mandated reform efforts as a process rather than treating them as events (e.g., Hall & Hord, Citation2015). Finally, this finding suggests that policymakers need to consider the timeframes required for educational changes when they are not aligned with existing beliefs and practices. Importantly, these findings highlight the need for school leaders who have the capacity to drive processes that facilitate change (Leithwood, Harris, & Hopkins, Citation2008), including the ability to: establish a positive school climate (e.g., Bysik et al., Citation2015; Leithwood et al., Citation2008), communicate effectively, and establish values and shared understandings (McIntyre & Kyle, Citation2006).

Our findings offer practical information to school leaders, described below, about factors that affect a school’s capacity for improvement (Hallinger & Heck, Citation2010; Heck & Hallinger, Citation2010; Leithwood et al., Citation2008). Arguably, these findings have the potential to enhance the success of change efforts.

Limitations

While this review aimed to synthesize relevant findings from a wide range of literature, we acknowledge the following limitations. First, our search criteria included only studies published after 2000, making possible the exclusion of important studies published before this date. Second, we limited our search to articles published in English, which may have led to bias against publications in other languages, thereby constraining the generalizability of our conclusions. Third, we acknowledge that the keywords, databases used, and our limit to peer-reviewed journals may have restricted the identification of relevant studies in our initial search. Further, important studies may have been missed since the research was required to be part of a mandated reform effort (excluding studies related to improvement efforts in a single school or classroom). Fourth, the 2293 articles identified in our initial search were culled substantially during our screening, quality, and relevance appraisal processes. Given our interest in studies that were part of a larger reform effort, we tended to include studies that did not explicitly state the change effort involved rather than omitting relevant studies. Notably, identifying relevant studies was undertaken collaboratively to enhance reliability. Fifth, although both authors carried out the quality assessment to increase accuracy, the somewhat subjective nature of the bias criteria check, mainly when applied to qualitative studies, proved difficult. Finally, although eligible articles were summarized and analyzed during thematic analysis, it is possible that relevant findings were missed.

Implications for Practice

Despite the limitations of our systematic literature review, the studies suggest factors that, if left unaddressed, will impact the success of reform efforts. Given that reform is not linear and is shaped by stakeholders at different levels of the system (Mehan et al., Citation2010), future research would benefit from examining how factors that occur at different stages of the change process interact and influence each other, and how these can be leveraged to enhance success.

Given the nature of schools, composed of stakeholders with competing agendas and the complexity of change, the need for strong, capable leaders is paramount. An important implication of our study is the need to build school leadership capacity to manage and lead reform. Note that this support (building leadership capacity) is reviewed in another part of our review (related to initiating educational change at the system-level factors).

Our findings suggest that reform success, even at the pre-implementation stage, relies on having leaders with skills to manage change (Robinson, Bendikson, McNaughton, Wilson, & Zhu, Citation2017), such as goal setting, defining core values and beliefs, and articulating the school’s needs. Leaders need a sound knowledge of the complexities of managing reform to ensure a coordinated approach (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, Citation2001), as well as skills related to data literacy, problem-solving, and evaluating school performance (Geijsel et al., Citation2010).

Our findings suggest that school leaders must lead (not only manage) change. Positive benefits were found when leadership teams had skills related to a wide range of interpersonal skills (Finnigan, Citation2011), such as collaborative skills, the ability to promote relationship building, and the development of social trust (Spillane & Louis, Citation2002). Further, the findings suggest that building leaders’ capacity to communicate effectively and resolve conflicts also will support reform efforts (Nguyen & Hunter, Citation2018).

Finally, the findings imply that leaders need to clearly understand the requirements of the change effort to enhance success. Time spent in the preliminary stages to help leaders gain definitional clarity and better understand the required skills and strategies will facilitate the reform’s introduction.

In light of our review, it is recommended that leadership preparation programs (for emerging leaders) and capacity-building programs for existing leaders (supported at the district- or system-level) examine ways to ensure they have the following:

Analytical skills to be able to:

Evaluate and reflect on the school’s needs.

Use data to make informed decisions about the school’s needs.

Knowledge and skills needed to design implementation plans linked to strategic goals.

Knowledge, skills, and dispositions to lead and manage school change processes.

An important finding in our review is that the school climate can support or hinder change efforts. Although it is widely acknowledged that a school’s context will impact the school leaders’ actions (e.g., Brauckmann, Pashiardis, & Ärlestig, Citation2020; Hallinger, Citation2018), information about the impact of the school context on educational change efforts (see, for example, Gericke & Torbjörnsson, Citation2022) is less widely reported. Therefore our findings help to advance this gap. Our findings suggest that developing a positive school climate will enhance reform success. However, given that changing the school climate involves a cultural shift, policymakers and school leaders must consider that this endeavor takes time. Further, given that schools are likely to have different school climates, our findings suggest that differentiated support to ensure reform-ready school climates across all schools would be worthwhile.

Although this review helps to address factors important to supporting reform (before implementation), the findings also lay bare future challenges for researchers and policymakers. More research is needed to examine factors that disrupt successful reform efforts and how these disruptions affect school climate, teachers, and the reform effort. Further research is required to investigate critical factors that promote the sustainability of successful implementation.

Although our literature review included studies carried out worldwide, most of the research was carried out in Western contexts; a challenge for future research is to examine the relevance of these factors that hinder and support reform efforts in non-Western contexts.

Conclusion

Much evidence suggests that mandate reforms and demanding educational change is an ever-present factor that affects schools. Educational change management can be reactive, discontinuous, and ad hoc, which, coupled with the variable success of reform efforts, makes it essential to make educational change a reality. Our literature review helps to better understand universal, evidence-based practices that can help guide school leadership as they navigate the complexities of reform before implementation. Understanding contextual and cultural nuances within the school will allow these practices to be tailored to address the unique needs of schools and their communities.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (376.4 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2023.2171439

Notes

1. Note that we accepted epublications (articles accepted by awaiting publication. This article has since been published).

References

- Addonizio, M. F., & Kearney, C. P. (2012). Education reform and the limits of policy: Lessons from Michigan. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research. doi:10.17848/9780880993951

- Aikin, W. M. (1942). The story of the eight-year study. New York, NY: Harper.

- Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2018). Teachers’ perceptions of the organisational climate: A tool for promoting instructional improvement. School Leadership and Management, 38(3), 323–344. doi:10.1080/13632434.2017.1411899

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organisational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass: Addison Wesley.

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1996). Organizational learning II: Theory, method, and practice. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Ärlestig, H., Day, C., & Johansson, O. (2016). A decade of research on school principals. Studies in Educational Leadership.

- Barakat, M., & Maslin-Ostrowski, P. (2019). Ripples of hope: Leading educational change for equity in Egypt’s public schools. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(3), 367–391. doi:10.1080/13603124.2019.1690706

- Bascia, N., & Hargreaves, A. (2013). The sharp edge of educational change. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bascia, N., & Hargreaves, A. (2013). The sharp edge of educational change. London: Routledge.

- Bashir, M., & Ul-Haq, S. (2019). Why madrassah education reforms don’t work in Pakistan. Third World Quarterly, 40(3), 595–611. doi:10.1080/01436597.2019.1570820

- Biddle, C. (2017). Trust formation when youth and adults partner to lead school reform: A case study of supportive structures and challenges. Journal of Organizational and Educational Leadership, 2(2), 1–30.

- Bishop, A. R., Berryman, M. A., Wearmouth, J. B., & Peter, M. (2012). Developing an effective education reform model for indigenous and other minoritized students. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(1), 49–70. doi:10.1080/09243453.2011.647921

- Borko, H., Elliott, R., & Uchiyama, K. (2002). Professional development: A key to Kentucky’s educational reform effort. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 969–987. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00054-9

- Brauckmann, S., Pashiardis, P., & Ärlestig, H. (2020). Bringing context and educational leadership together: Fostering the professional development of school principals. Professional Development in Education. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1747105

- Brezicha, K., Bergmark, U., & Mitra, D. L. (2015). One size does not fit all: Differentiating leadership to support teachers in school reform. Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(1), 96–132. doi:10.1177/0013161X14521632

- Bridwell-Mitchell, E. N. (2015). Theorizing teacher agency and reform: How institutionalized instructional practices change and persist. Sociology of Education, 88(2), 140–159. doi:10.1177/0038040715575559

- Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & Lemahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. 120.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Bubb, S., & Earley, P. (2009) Leading staff development for school improvement [Review]. School Leadership and Management, 29(1), 23–37. doi:10.1080/13632430802646370

- Bulach, C., & Malone, B. (1994) The relationship of school climate to the implementation of school reform. Ers Spectrum, 12(4), 3–8.

- Bullock, H. L., Lavis, J. N., Wilson, M. G., Mulvale, G., & Miatello, A. (2021). Understanding the implementation of evidence-informed policies and practices from a policy perspective: A critical interpretive synthesis. Implementation Science, 16(1), 18. doi:10.1186/s13012-021-01082-7

- Bysik, N., Evstigneeva, N., Isaeva, N., Kukso, K., Harris, A., & Jones, M. (2015). A missing link? Contemporary insights into principal preparation and training in Russia. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 35(3), 331–341. doi:10.1080/02188791.2015.1056588

- Cameron, E., & Green, M. (2004). Making sense of change management. A complete guide to the models, tools & techniques of organizational change. London, UK: Kogan Page.

- Caputo, A., & Rastelli, V. (2014). School improvement plans and student achievement: Preliminary evidence from the quality and merit project in Italy. Improving Schools, 17(1), 72–98. doi:10.1177/1365480213515800

- Card, N. A. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Carrington, S., Spina, N., Kimber, M., Spooner-Lane, R., & Williams, K. E. (2022). Leadership attributes that support school improvement: A realist approach. School Leadership & Management, 42(2), 151–169. doi:10.1080/13632434.2021.2016686

- Castellano, M., Stringfield, S., & Stone, J. R. (2016). Secondary career and technical education and comprehensive school reform: Implications for research and practice. Review of Educational Research, 73(2), 231–272. doi:10.3102/00346543073002231

- Causton-Theoharis, J., Theoharis, G., Bull, T., Cosier, M., & Dempf-Aldrich, K. (2011). Schools of promise: A school district-university partnership centered on inclusive school reform. Remedial and Special Education, 32(3), 192–205. doi:10.1177/0741932510366163

- Cave, P. (2011). Explaining the impact of Japan’s educational reform: Or, why are junior high schools so different from elementary schools?. Social Science Japan Journal, 14(2), 145–163. doi:10.1093/ssjj/jyr002

- Cheng, Y. C. (2020). Education reform phenomenon: A typology of multiple dilemmas. In G. Fan & T. Popkewitz (Eds.), Handbook of education policy studies Midtown Manhattan, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8347-2_5

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7

- Clement, J. (2014). Managing mandated educational change. School Leadership and Management, 34(1), 39–51. doi:10.1080/13632434.2013.813460

- Cooper, H. M., Patall, E. A., & Lindsay, J. J. (2013). Research synthesis and meta-analysis. In L. Bickman & D. J. Rog (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of applied social research methods. London, UK: Sage.

- Copland, M. A. (2003). Leadership of inquiry: Building and sustaining capacity for school improvement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(4), 375–395. doi:10.3102/01623737025004375

- Covidence systematic review software (2019). Veritas health innovation. Retrieved from www.covidence.org

- Creemers, B., & Kyriakides, L. (2008). The dynamics of educational effectiveness: A contribution to policy, practice, and theory in contemporary schools. London, UK: Routledge.

- Creemers, B. P. M., Kyriakides, L., & Antoniou, P. (2013). A dynamic approach to school improvement: Main features and impact. School Leadership & Management, 33(2), 114–132. doi:10.1080/13632434.2013.773883

- Datnow, A. (2005). The sustainability of comprehensive school reform models in changing district and state contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 41(1), 121–153. doi:10.1177/0013161X04269578

- Datnow, A., & Castellano, M. E. (2001). Managing and guiding school reform: Leadership in success for all schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 37(2), 219–249. doi:10.1177/00131610121969307

- Datnow, A., Lasky, S. G., Stringfield, S. C., & Teddlie, C. (2005). Systemic integration for educational reform in racially and linguistically diverse contexts: A summary of the evidence. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 10(4), 445–457. doi:10.1207/s15327671espr1004_6

- Datnow, A., & Stringfield, S. (2000). Working together for reliable school reform. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 5(1–2), 183–204.

- Day, C., & Lee, J. C.-K. (Eds.) (2011). New understandings of teacher’s work: Emotions and educational change. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Leithwood, K., Hopkins, D., Harris, A., Gu, Q., & Brown, E. (2010). Ten strong claims about successful school leadership. Watford, UK: The National College for School Leadership.

- Demerath, P. (2018). The emotional ecology of school improvement culture. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(5), 488–503. doi:10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0014

- Desimone, L. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Towards better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140

- Dueppen, E., & Hughes, T. (2018). Sustaining system-wide school reform: Implications of perceived purpose and efficacy in team members. Education Leadership Review of Doctoral Research, 6, 17–35.

- Edwards, F. (2012). Learning communities for curriculum change: Key factors in an educational change process in New Zealand. Professional Development in Education, 38(1), 25–47. doi:10.1080/19415257.2011.592077

- Erlichson, B. A. (2005). Comprehensive school reform in New Jersey: Waxing and waning support for model implementation. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 10(1), 11–32. doi:10.1207/s15327671espr1001_2

- Evans, M. J., & Cowell, N. (2013). Real school improvement: Is it in the eye of the beholder?. Educational Psychology in Practice, 29(3), 219–242. doi:10.1080/02667363.2013.798720

- Fernandez, K. E. (2011). Evaluating school improvement plans and their affect on academic performance. Educational Policy, 25(2), 338–367. doi:10.1177/0895904809351693

- Fidan, T., & Oztürk, I. (2015). The relationship of the creativity of public and private school teachers to their intrinsic motivation and the school climate for innovation. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 905–914. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.370

- Fink, D., & Stoll, L. (2005). Extending educational change. In A. Hargreaves (Ed.), International handbook of educational change (pp. 17–41). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Finnigan, K. S. (2011). Principal leadership in low-performing schools: A closer look through the eyes of teachers. Education and Urban Society, 44(2), 183–202. doi:10.1177/0013124511431570

- Fullan, M. (2001a). The new meaning of educational change. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Fullan, M. (2001b). The new meaning of educational change. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Fullan, M. (2007). The new meaning of educational change (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Fullan, M. (2010). All systems go: The change imperative for whole system reform. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Galloway, M. K., Callin, P., James, S., Vimegnon, H., & McCall, L. (2019). Culturally responsive, antiracist, or anti-oppressive? How language matters for school change efforts. Equity and Excellence in Education, 52(4), 485–501. doi:10.1080/10665684.2019.1691959

- Ganon-Shilon, S., & Schechter, C. (2019) School principals’ sense-making of their leadership role during reform implementation. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 22(3), 279–300. doi:10.1080/13603124.2018.1450996

- García-Martínez, I., Pedro, J. A. T., Pérez-Ferra, M., & Ubago-Jiménez, J. L. (2020). Building a common project by promoting pedagogical coordination and educational leadership for school improvement: A structural equation model. Social Sciences, 9(4), 52. doi:10.3390/socsci9040052

- Gavin, M., & Stacey, M. (2022). Enacting autonomy reform in schools: The re-shaping of roles and relationships under Local Schools, Local Decisions. Journal of Educational Change. doi:10.1007/s10833-022-09455-5

- Gaziel, H. H. (2010). Why educational reforms fail: The emergence and failure of an educational reform: A case study from Israel. In J. Zajda (Ed.), Globalisation, ideology and education policy reforms. Globalisation, comparative education and policy research (pp. 11). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-3524-0_4

- Geijsel, F. P., Krüger, M. L., & Sleegers, P. J. (2010). Data feedback for school improvement: The role of researchers and school leaders. The Australian Educational Researcher, 37(2), 59–75. doi:10.1007/BF03216922

- Gericke, N., & Torbjörnsson, T. (2022). Supporting local school reform toward education for sustainable development: The need for creating and continuously negotiating a shared vision and building trust. The Journal of Environmental Education, 53(4), 231–249. doi:10.1080/00958964.2022.2102565

- Goldenberg, C. (2003). Settings for school improvement. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 50(1), 7–16. doi:10.1080/1034912032000053304