ABSTRACT

This article explores counter-design as a radical meaning-making practice for community co-design. Radicalism, here, is an ongoing process of complicating and unsettling daily practices to reveal and thus acknowledge socio-political context. Semiotic analysis of ethnographic research with grassroots organisations is taken as the point of departure to understand how communities co-design meaning, and in turn how we might co-design new meanings through countering. Through counter-design in place, we observe small semiotic moments that problematise the rhetoric of horizontal democratic organising amongst the realities of coercion and power asymmetries. These semiotic moments are thus significant for how they reveal the reproduction of meaning and how this constructs, and can subsequently limit, the possible actions for these communities. In this sense, our approach constitutes a design praxis, through which we analyse what it means to employ countering against existing institutional power, both for our participants and for ourselves as designers. Here, we reveal the tenuousness of (designer/ly) intent in relation to and in combination with the artifice of readymade community designs, as these are shaped by work ‘on the ground’ and consider how this might impact the co-creation of democratic communities.

1. Introduction

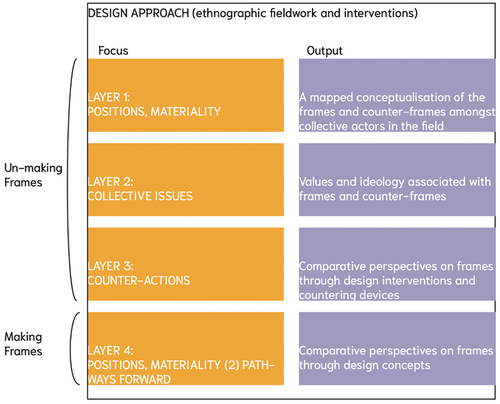

Radicalism is deeply entwined with and reliant on countering (Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022), and so the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)-funded Counter-Framing Design (CFD) research project had to deal with this relationship at the outset. Countering is the action of employing an ensemble of practices that mobilise counter-frames to unsettle institutional frames (Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022), where counter-frames are constructed by communities to oppose, problematise, or displace widely accepted (i.e. institutionalised/normed) frames on social or political issues (Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022). This point of departure was a response to our prior work with grassroots design communities who we observed to adopt or align with socio-political (sustainability) frames (e.g. ‘degrowth’ and ‘community wealth building’) in support of community organising and often against institutionalised frames (e.g. ‘green growth’ and ‘wealth inequality’) (Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022).

While these organising frames are significant in and of themselves, they are always the result of and interwoven with practices within relationships, the complexity of which required a turn towards design anthropology and participatory design methods. We wanted to explore how design practice might be able to deepen our understanding of (counter-)frames with a view to unsettling institutionalised practices by making existing alternatives visible, and how those alternatives come to be obfuscated in a context. In turn, our research question became, how might countering (of but also beyond frames) be rearticulated as a critical (designed) practice in support of community organising? In response, our research thus far has informed a tentative expression of counter-design, co-designed with, and deployed among social-justice oriented organisations. Counter-design, then, is a process of design praxis (in research and application) that seeks to foreground processes of countering (ensembles of practices) that challenge existing systems in the pursuit of alternative meanings and thus possibilities.

In this article, we understand counter-design through the tool of semiotic analysis, to extract the meaning-making processes evidenced through community practices. We focus on how this semiotic process can reinforce and/or disrupt hegemonic structures observable through such frames in small, everyday ways. We explore the reproduction, or rearticulation, of these semiotic processes within the context of our project collaborators: Citizens UK (CUK) is a group that pushes for policy change through community organising campaigns, and Outlandish is a digital cooperative that focuses on technology for social impact. These semiotic moments are significant in that they reveal the reproduction of meaning frames and how this constructs, and may therefore limit, possible actions for these communities. This is consequential for any design practice concerned with democratisation as it reveals the making of consensus or consent, as well as power asymmetries in practice, and therein the possibilities and limits for any critical designerly intentionality, in our case counter-design practice and interventions.

Praxis, taken as the implementation of theory-practice to some transformative ‘end’, is central to this generative approach. Praxis is useful in aiding us to think about and complicate intent, particularly in its relationship to liberation. Since praxis assumes liberatory aims (Freire Citation[1970] 2005, 79), it foregrounds intent and impact, and requires those who employ praxis to contend with and be honest about how their intent does or does not serve said aims, i.e. how it becomes impact. Indeed, it is the recognition that the intent of designers can never ‘perfectly’ and predictably match the use of the design that has influenced design for social justice calls. For instance, principles of design justice include, ‘We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer (Costanza-Chock Citation2020, 6)’. Similarly, in our work, designers can only learn to recognise that consequential semiotic moment, yet cannot expect to perfectly intervene to control that moment.

Praxis, then, is a practice of (designer) solidarity because it requires us to think about intent as an ethical practice whilst not privileging intent over impact. In acknowledging and accounting for the agency of others (users or community members), we attempt to move towards solidarity, as shared feelings, ethics, and actions, based on new skills and knowledge for recognising the making of democratic outcomes. Yet it benefits us to acknowledge critiques of how praxis operates within a Western (and capitalist) structure that prioritises human-specific operativity and intent (Wainwright Citation2022).

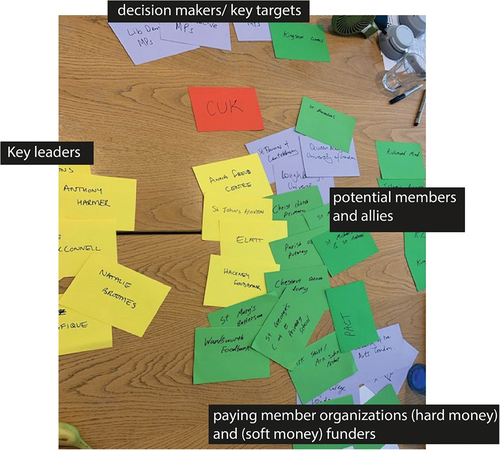

Yet, solidarity is not a consensus and does not preclude broader socio-cultural hierarchies (racial, patriarchal, gendered, academic) of intent or power that are also co-constructed and reproduced within institutions and communities. Solidarity does not assume sameness – only equal existence – between co-participants, since there will always be differences in (inter)actions and intent (Bogost Citation2010; Bryant Citation2011). Thus, while solidarity may indeed cross difference, it can still fall prey to the above socio-cultural hierarchies and be retooled as a basis for uneven power and privilege. In response, we focus on community co-design as an ongoing process of coalition in opposition to the ‘logic of power’ (Lugones Citation2010) by highlighting moments of disruption within similar such hierarchies of intent through the examples of countering we present in sections 3.2 and 3.3. Still, in retracing our steps, we find evidence of our own ‘designerly’ intentionality, i.e. the hope for an interaction that would reproduce a given community structure (see ), even in being open to possibility.

2. Counter-design in the context of radical thought

How then can we understand our conceptualisation of counter-design in a wider radical context? Our project orientation towards praxis is a pursuit of alternative possibilities. Making alternatives visible requires questioning received understandings through an epistemology of co-learning, especially of designer intent. Knowledge is co- and re-created, and enacted in the daily lives of people, and sometimes towards our own liberation.

We thus turned to theorists who have sought to challenge modernist simplifications of social organisation through careful attention to everyday practices and actions. Our work has a lineage in De Certeau’s (Citation1988) tactics as the ’art of the weak’ (37) and Jacobs’s (Citation[1961] 1992) insistence on the significance of informal urban order in everyday practices as a basis for understanding the transgressive manoeuvres available in any social context – moments of destabilisation, by praxis, in an often uneven playing field. These manoeuvres are ‘breaks’ in the sensible that allow for new, or newly perceived, ways of experiencing the world to manifest. Design activity is relevant in seeking to foster such a disarticulation of experience (Murphy Citation2016). By design activity, we refer to the ‘nexus of minds, bodies, things, and the institutional arrangements within which designs are constituted’ the coalescence of which renders design practices as ‘situated’ and ‘contingent’ (Kimbell Citation2009). Illustratively, Isabelle Doucet (Citation2015) emphasises place for understanding the complexity that makes Brussels a living and changing assemblage, co-produced by those who plan and build it, alongside socio-political ideologies, and mundane practices. Of course, the corollary to this is that design activity also plays its part in rendering ‘sensible’ status quo institutional arrangements. Such activity involves cross-disciplinary knowledge which is more complex than disciplinary knowledge, such as Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) or expansive learning, which attempt to bridge the theory-praxis gap by foregrounding relations between actions, activities, and learning, in cultural and historical contexts (Roth and Lee Citation2007). This aligns with how our counter-design framework means to convey the relationship between individual and collective meaning-making, drawn from an initial interest in frames and framing, that disrupts notions of readymade community design (Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022).

Across the project we have accessed these shared and co-(re)produced frames through both material (object) and linguistic sign processes but always aimed towards understanding the various ways everyday practices are scripted by these frames (Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022; Prendeville, Syperek, and Santamaria Citation2022). For example, earlier project activities revealed how frames are ‘thingified’ through words and objects and enacted in daily practices in complex and sometimes contradictory ways, and how they are embedded more widely than immediately obvious practices of (re)producing slogans (see Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022). Design research that centres on radicalism allows us to emphasise the tactical nature of these processes, as they are ‘designed in’.

Revealing this tactical nature also allows for enacting new practices and tactics that redefine institutional arrangements from within, as a process of radical design (Beck Citation2002; Björgvinsson and Keshavarz Citation2020; Huybrechts, Benesch, and Geib Citation2017; Kjærsgaard et al. Citation2016). Nevertheless, the dominant short history of ‘radical design’, as rooted in Italian thought and practice, arguably betrays this pursuit of cross-disciplinarity, perpetuating the perception of an archetypal radicalism or ‘original’ radical design knowledge (Ansari Citation2019). As significant are histories of jugaad (Rai Citation2019), the work of feminist radical collectives such as Matrix (Citation[1984] 2022), Black radical designers (Bonhomme Citation2022), and the transgressive counter-institutional architectural aesthetics of Bolivian ‘cholets’ (Runnels Citation2019) – all of whom non-conformed, challenging gendered and racialised forms of inclusion in design practice. So too have Indigenous Knowledges often foregrounded equal existence, not just within the human-to-human hierarchies mentioned in acts of solidarity, but also with more-than-humans within design praxis (Conway and Singh Citation2011; Escobar Citation2018; Querejazu Citation2021). Calls for a radical paradigm shift involve the recognition of transcultural and more-than-human design, which necessarily develops in conjunction with existing Indigenous Knowledges (Winschiers-Theophilus, Zaman, and Stanley Citation2019). These knowledge practices provide a space to question our received understandings as they upset what disciplinary design has made invisible. Counter-design is thus situated in an interdisciplinary lineage and attuned to making visible existing radicalisms, without assuming that we are designing in any-and-all radicalisms.

3. Community co-design and design anthropology

Situating our work within this wider context helps us grapple with disciplinary histories tied to colonialism’s legacy of upholding academic power (hierarchical intent) over other knowledge systems, precisely because of the de-/anti-colonial paradigm shifts across these disciplines (Abdulla et al. Citation2019; Ansari Citation2019; Freire Citation[1970] 2005; Mareis and Paim Citation2021; Quijano Citation2007; Rivera Cusicanqui Citation2012). Becoming perpetual students of these ontologies is a form of countering of the (academic) self, a question of researcher power and positionality, which we tackle more squarely elsewhere. Whilst we cannot apply the nuance and context to these theories that would prevent homogenisation, we have learned to seek more direct learning and exchange with those with whom we work. For our research, this direct learning occurred through observation of how frames are reproduced and enacted, in turn requiring a pivot towards design anthropology. The use of design anthropology supported our exploration of the relationship between collective and individual behaviours, and how these behaviours reproduce and were reproduced through processes of mean-making, i.e. semiotics as utilised in anthropology. A ‘design anthropology’ methodology allowed us to achieve this, as it transcends the hybridisation of institutional categories and focuses on various skill sets that have emerged within these disciplines and which we deployed (e.g. participatory workshopping and participant observation) and sensitivities to ways of doing (e.g. thinking through designers’ impact on conversation flows, analysing negotiations of power as participants map their organisation’s networks). We aim to think about ways of doing first, which allows us to acknowledge that all communities practice the co-design of themselves (Escobar Citation2018) and thus to be realistic about how our own (disciplinary) backgrounds have shaped (and in shaping, limited) our skills.

3.1. Design research methodology incorporating semiotics

On this basis, we also consider the situatedness of community organising in the UK, beyond participatory fieldwork and co-design workshops deployed with participating organisations (CUK and Outlandish). This context is radical in its anti-capitalism but still operates and negotiates within a shared view of the world ‘as it is’. We begin with a discussion on how CUK members co-design their campaigns. This is evidenced in Anaïs’ participatory research in a Migrant Employability campaign, which she was deeply invested in as the daughter of a migrant parent (from Bolivia to the U.S.) who experienced similar hindrances to employment. We then offer a more detailed analysis of elements of our interactions, drawn from interviews, meetings, and design activities hosted with each organisation.

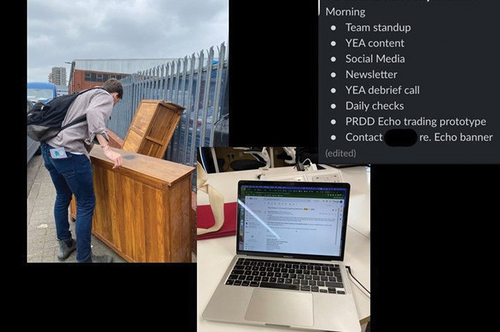

Data gathering involved attendance at in-person partner-facilitated events, in-person informal meetings, and virtual meetings, where more detailed observation notes could be taken, as well as email chains to discuss the goals of the project and participation. The primary workshops analysed here were conceived in response to our counter-design framework, an ensemble of practices that challenge normalised ways of doing/being articulated through frames. This involved pre-workshop design probes to create mini daily photo-journals (), with a prompt to convey a daily practice participants employed for their organisation. This informed the workshop's focus on mapping practices, relationships, and codesigning new practices.

Mapping practices involved free-writing and then sorting organisational networks based on participant criteria (), such as how closely other people and communities aligned with their central values or what their main relationship was (e.g. funders or users of their services).

This was done multiple times to elicit conversations on the practices employed in internal and external relationships (and to complicate this binary frame) and where tensions arose in these practices. From here, some participants stayed with the process of revealing intimacies of values and practices, particularly where they might not align. Others began thinking through new, renewed or new-in-place practices in response to the revealed tensions.

Workshops were evaluated after each deployment and modified for the number of participants and their response to the materials in real time. Throughout all in-person and virtual activities, notes and, when consented to, audio recordings and photographs were taken. Analysis of materials focused on the power dynamics and interactions between participants in the room, including the researchers, as much as the content of the conversations. As such, we chose to focus our analysis on two key instances where concepts (e.g. frames) were re-articulated, contested, or negotiated in ways that evidenced how countering practices were either obscured (winnability as a frame that was not contested in CUK, Section 3.2) or highlighted (manipulation as reframed in Outlandish in Section 3.2). These were identified and selected as points of analysis on account of the significance they appeared to have in relation to the ongoing maintenance of the community structure. These ‘moments’ were chosen as an outcome of iterative analysis of the fieldwork materials and several team-based discussions on potentially salient points. Moments, in this analysis, are defined by the investment of the people present in meaning-making. We focused on the process of semiotic re-creation or contestation, in moments of conversation or in actions, not designated limitations. Significantly, these moments were identified as sites of (potential) expansion, a goal of counter-design, and reckoned with power dynamics in some way that was evident in our analysis (see 3.2 and 3.3).

Along with a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of words (how they articulate power directly) we analyse the social context, a contribution of Systemic Function (SF) theory (Ledin and Machin Citation2019, 5). This analysis of the ways in which these concepts are articulated in a particular setting (e.g. the variance between how ‘winnability’ is articulated at a partner-led training vs. our design workshops), between certain people in the room, and with the (design) materials at hand, allowed us to understand the organisation through the design activity, but there was still a gap between talking about practices and enacted/embodied practices. To bridge this, we draw from broader fieldwork insights on the reproduction of practices themselves as sign processes outside of the workshops, in contrast to physical movement, tone, or other qualities in situ. Thus, our approach is broadly semiotic and is concerned with the everyday shaping of ‘realities’ and how we conceive of a design practice that is situated within possibilities for disruption. It is simultaneously ethnographic and participatory by, for example, employing co-design workshops analysed through linguistic anthropology frameworks, aimed at meaning-making in relation to power. Our semiotics begins with the Peircean triadic model of an object, an interpretant, and a sign vehicle or representamen (Peirce Citation1955) ().

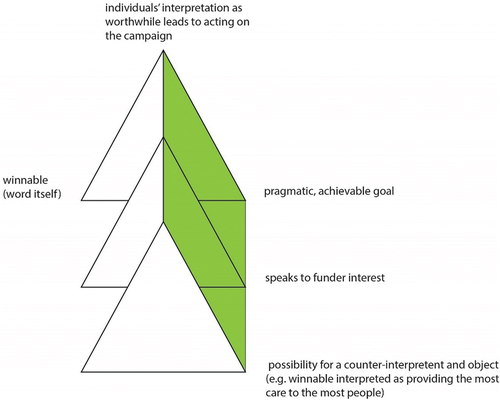

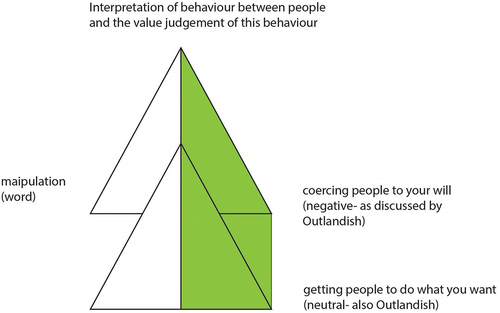

Figure 4. Peircean triad with reference to our focus on how the interpretant and object relationship can contribute to meaning-making (top) followed by a model of ‘winnability’ as the representamen (second) followed by a model of ‘manipulation’ as the representamen (bottom), by authors.

In the Peircean model, the sign vehicle creates and/or reinforces a litany of intertextual meanings that support community ideologies. As Peirce understood from Saussure, signs must be reproduced through habitual use (Saussure Citation[1959] 2011) which allows meaning to be both reproduced and interrupted, also through misunderstandings. The case studies that follow were chosen because they notably (re)articulated signs within the context of negotiations of power. Observable practices of countering were happening in the discourse and spatial context, which related to our broader concerns about how a counter-design might support other organisations. The benefit of semiotic analysis is in understanding the process of (re)creating meaning and the implications for design practice, not simply uncovering the layered meanings behind a particular ‘thing’ (word, object, discourse, practice, and so on).

3.2. Idealised pragmatism: winnability

Our first case study emerged from a consistent talking point across our interactions with the CUK that was a direct articulation of power dynamics – the conceptualisation of ‘winnability’ (). This frame was invoked multiple times within the Migrant Employability and other campaigns, conjuring an idealised pragmatism, ‘a message that’s winnable with enough backing’ (campaigner). This, in turn, determines the worthiness of a project, and ultimately is a stance on whether and how an idea will be championed and is consequential for the ongoing shape of community practices.

Figure 5. Example of where various meanings can be made of ‘winnability’ in the relationship between representamen, interpretant and object (with the shaded interpretant/object as the space of changing meaning), by authors.

This stance is reproduced both linguistically and non-linguistically, throughout CUK’s sign practices, (one-to-one meetings, assembly meetings, campaigns with partner organisations) attended by researchers as part of their ethnographic methodology. Several times meetings began with work already done by CUK leaders and staff to move the campaign along in the most feasible and ‘winnable’ way, often in conjunction with existing CUK networks, speaking to the processes and practices of ‘norming’ entangled within a logic of pragmatic action. This is significant in the context of migration in the UK during the period of observation, when discourse on ‘economic migrants’ supported normative pro-growth capitalist frames and reinforced notions that migrant ‘goodness’ was dependent upon economic value in relation to the state (Prendeville, Carlton-Parada et al. Citation2022). Space for radical approaches, those which might move past economic growth frames and employ a broader meaning of value, exists where these norming processes might be troubled.

Still, the Migrant Employability campaign that Anaïs continues to support was, at least initially, passed during an accountability assembly as a campaign that CUK would take on, suggesting it was deemed ‘winnable’. Yet, this winnability was already foreshadowed at the outset of the assembly through the community’s practices of curating campaigns at their earliest stages with the support of a CUK staff member, including staff suggesting and deciding on possible campaign topics ahead of time based on the desire of funders and/or large swaths of community members who were meant to be represented by the institutions that brought the campaigns forth.

Moreover, practices of norming (e.g. semiotic processes) were reinforced through the materiality of PowerPoints, scripts and other tools employed during meetings. Assembly meetings provide a campaign structure. The first assembly is meant to create the possible campaigns. During the second round, delegates assemble to ratify a joint manifesto, including choosing (winnable) campaigns that will be taken forth. In the second meeting, however, each campaign team had to present, adhering to a CUK structure, including a strict time limit, emphasis on testimony from a member of the community, and a pre-written script. These formats were deployed via emails between CUK staff and campaign team members as PowerPoint examples and reiterated within meetings that included a CUK staff member. Thus, ongoing processes of structuring outcomes (via the deployment of artefacts, timing, and insistence on the benefits of testimonials) constrained what was possible through linguistic, physical, and material practices.

The emphasis on testimonies was particularly fraught. They were meant to elicit an emotional response. One CUK staff member emphasised that the entire presentation should be a ‘rousing story’, yet the performances varied. Within our own campaign, we had a team member testify with a firm and determined tone, alongside hand gestures that emphasised need, while a testimony from a migrant was quite even and varied little in tone, suggesting a contested understanding. Moreover, while some team members worked directly with migrants in need of jobs, many migrants had concerns about confidentiality and safety or did not see a tangible benefit in exchange for their time and storytelling, leading to a decline of potential testimonials by the third assembly. The third accountability assembly presented the campaigns to the wider Hackney and Islington communities, including local politicians. Still, a sample script was sent out ahead of time, with testimonies pushed as a central feature along the way and an affiliate institution ran a public speaking workshop for campaign members prior to the third assembly.

While there are practical needs being addressed in the campaign, there is a problem of both discourse and action. In discourse, it is impossible to isolate these employment needs from the broader socio-political discourses pertaining to the ‘migrant question’ and the institution of a new points-based immigration system in the UK off the back of it leaving the EU (Borrelli et al. Citation2022). In action, some who were the potential beneficiaries of the campaign did not see enough tangible support to appease their concerns over safety or be worthy of their time. Indeed, the notion of ‘winnability’, although reiterated throughout the assemblies and meetings, did not seem to address these contextualised concerns.

Indeed, what makes an initiative winnable is obscured amongst the milieu of structuring practices: horizontal at the community organising and outreach level and more vertical among formal CUK employees. In a workshop with CUK staff and their community leaders involved in the Settle our Status campaign for migrants, one participant mentioned:

I think the issue is more about what is it winnable … If it’s not winnable, we don’t go there. If it is winnable, even if it takes a long time, we will stay with it. And we will keep at the politicians … to make sure we get there in the end, because I think the big issue is do we decide in our own minds that this is a winnable thing?

Here, winnability is defined implicitly as something that can be won, but there is a reference to resilience and to seemingly subjective but also group decision-making processes. Indeed, in the context of the CUK, we observed how this discourse of winnability was sustained through decision-making practices that determined who had a voice, which relied on status and leadership whilst ostensibly sustaining a democratic membership model.

If winnability is decided based on the existing power of the organisation, it seems unlikely to be disruptive, since it cannot work outside of existing power structures. Indeed, the notion of winnability as tied to (idealised) pragmatism comes directly from Saul Alinsky’s campaign model, along with CUK’s formulation of power as money and people, and their desire to leave political ideology out of campaigning (Petcoff Citationn.d.). Yet, these are political movements who organise against institutionalised policies through practices such as taking to task racial divisions or building democratic engagement among the community. Moreover, we observe winnability leveraged as a consensual frame, ensuring less radical, often more short-term demands, which are less disruptive to the institutions campaigners demanded from. Thus, the potential benefits associated with a non-partisanship model become watered down, as any discord is pre-emptively closed off through structuring practices, such as those described as part of the assembly processes.

Illustratively, within the Migrant Employability campaign, I (Anaïs) consciously introduced physical notes as semiotic objects and as a countering practice. This was contra CUK’s oral tradition practices, but to benefit campaign members by giving context for absent members, providing references for future work, and inviting edits where note taking was insufficient or incorrect. This was conceived as a simple design intervention based on open documentation, towards fostering different ways of storytelling to deal with the question of ‘voice’ in meetings. However, we settled on a counter to CUK’s oral tradition practice in part because it was attuned to the everyday-ness of practices that we had focused on through an ethnographic methodology. Written notes are rarely if ever used and thus would affect the design of the campaign, via the experiences of my campaign partners with this ‘thing’, simultaneously an emailed document, a way of accounting for, and a resource that might evidence discounted ideas or future possibilities at the behest of those most ‘winnable’. As a campaign co-designer, I (Anaïs) was challenging a somewhat rigid conception of what constitutes a practice of solidarity within the community, by introducing a pattern of doing, whilst dealing with the ethics of this conscious countering. This pattern was reproduced by another team member in my absence, becoming a shared activity, and was eventually replaced by video and audio recordings of the meetings. Thus, while documentation is a simple countering practice, here it helps us evidence those preconditions and processes that sustain a somewhat uncontested frame within this community. However, the campaign did ‘fail’ at delivering on initial ‘wins’ and shifted from focusing on political support, targeting businesses and trade unions, to moving outside its initial bounds of CUK, and being taken forwards by local organisations and employers.

3.3. Intimate power: manipulation

Our engagements with members and collaborators at Outlandish generated similar examples of semiotic co-creation through productive contestation. Take, for example, this conversation that arose during the design workshop.

P1: … the manipulation that lies there between siblings … My sister manipulates me now and again, and I know she’s doing it. And I love her so I can be forgiving about that … but the thing is that I don’t think I would try to manipulate somebody at work, you know? … Did you want to say something? (inaudible) you were like …

P2: Oh, maybe two things. A, I think we all manipulate each other all the time. I think we’re just a bit more aware of doing it with our siblings because it’s more … with your family you’ve got that safety so it’s kind of more okay for it to be on the surface but I actually think we’re all doing it to each other unconsciously, but all the time, and that it’s just we don’t really talk about it because it’s such a scary thing. It seems like such an evil … kind of word … I also wonder if … the fact that we had family in the organisation … created a foundation for quite intimate relationships in the workplace.

In this dialogue, we can observe opposing conceptualisations of manipulation, and tensions between familial and workplace intimacy. Like the CUK’s idealised pragmatism, evidenced through ‘winnability’, these dynamics at Outlandish appear to construct possible practices, particularly those centred on negotiating relationships. Together, and in opposition, the participants have highlighted and problematised the concept and practice of ‘manipulation’ (), simultaneously negotiating their own relationship dynamic in a balance of power that allows for turn-taking, e.g. P1 directly inviting P2 to respond. Presumably P1 read P2’s non-verbal cues and/or acted on some other information where P2 did not request space but had knowledge to contribute, as evidenced by the phrase ‘You were like …’. Regardless, this allowed them to reflect on the foundation of their workplace as substantially intimate and familial, countering false binaries and social structures of family intimacy vs. workplace professionalism. Yet it also evidences how they enact care, both linguistically (e.g. through contested framings of manipulation) and through actions (e.g. P1 inviting P2 to respond). Throughout the workshop, the locus of these ‘personal’ boundaries and the practices of negotiating them were central and fraught.

Figure 6. Example of where various meanings can be made of ‘manipulation’ in the relationship between representamen, interpretant and object (with the shaded interpretant/object as the space of changing meaning), by authors.

Contention over manipulation is also evident in wider fieldwork contexts where manipulative actions are invoked as beneficial tactics to solicit preferred outcomes. The authors make a link to manipulation as a skilful influence, and the ways in which countering as a tactical process was employed by Outlandish members to challenge normalised framings. As P2 from Outlandish noted, while the word manipulation can be ‘scary’, the actions encompassed in the word happen all the time, with everyone. A similar reframing for Outlandish is explored with the notion of conflict. As P1 mentioned, ‘Some of the practices that Outlandish, that we have collectively said we want to use, can provoke conflict and I think that’s fine’, but she also acknowledged moments where co-workers did not address conflict on a project, and how she countered this by explicitly stating that there was a ‘fight’ but that they were working through it.

Our design workshop also elicited references to caretaking practices, professional relationships with parent–child dynamics, gendered roles of the ‘mother’ or ‘bossy b—’, showing emotional upset, love, and sharing personal histories, all of which, in a similar vein, become axes of manipulation. These practices stand in stark contrast to the normalisation of a personal (family) and professional (work) divide that may be reiterated in workplaces while simultaneously ignoring the immense importance of the family in supporting and reproducing capitalist systems of labour, imposing state-sanctioned norms, and harbouring harm, particularly against those already marginalised (Benston, Citation[1969] 2019; Hooks Citation2001; Marx and Engels Citation[1848] 1967).

What is significant here, is that countering normed framings of manipulation (or conflict) reveals the manifold possibilities at play and how these are simultaneously (co)created in discourse and practice. This appears to sit in contrast to how community power is assumed to be democratically distributed via procedure at Outlandish. As a collaborator mentioned:

… having a structure in place which … consciously gives space to everyone and that everyone agrees is a good system to use means that you’re able to kind of take back some of your power … or in fact, you don’t have to take it back. That’s the point, you’re given back your power without you having to stand up and grab it.

Mapping practices with participants led to discussions on extended check-ins, reflective listening, structuring conversations through FONT (feelings, observations, needs, and thoughts), and consent-based decision-making meant to ensure respect, trust, and democratic voicing. Voice is mediated through a language of sociocracy, whereby phrases like ‘I join you’, ‘do you consent to that’ and ‘are you on this journey with me’ convey circumscribed spaces with named practices. Such spaces are ostensibly outside of manipulation, yet should be, and necessarily are, equally open to semiotic disruption. Indeed, P1 directly addressed tensions that arise when practices are brought in and hidden conflicts that can be (sometimes purposely) provoked, as in the examples above. Thus, these intentional practices are also provocative practices, a double pronged approach to open dialogue.

Accordingly, tensions of power dynamics which were ‘internally’ unavoidable were nevertheless understood to be something that could be ‘externally’ manipulated (without ascribing judgement), speaking to both a co-construction and reproduction of practices, and contradictory understandings of where those practices can or cannot be successfully applied, much in the way ‘winnability’ constructed what was possible. This heavy focus on the organisers to construct possibilities and the ways of organising eclipses the possibility that community members might have their own visions for how to organise and campaign.

4. Countering as radicalism

This paper presents a framework for counter-design that draws on semiotic analysis of community co-design. In this case, the communities are grassroots organisations, who constantly negotiate pragmatism, idealism, intimacy, power and a multitude of on-the-ground challenges that shape how they ‘construct the possible’. These semiotic communities rely on shared signs to create cultural meaning, where these signs exist as both linguistic framings and enacted practices. Countering here is exemplified by the ways in which ensembles of practices are shown to both obscure uncontested frames (e.g. ‘winnable’) and highlight rearticulated frames (e.g. ‘manipulative’). We have illuminated where and how dissensus emerges where these signs are not shared or become contested. Thus, counter-design provides a framework for fostering this knowledge through community codesign involving mapping frames and practices in situ, to make assumptions and norms explicit and create space for new possibilities for alternative ensembles of practices to take shape. Yet it is not always a practice to be applied. Our interest in moving towards a radical approach via counter-design stems from the desire to continuously complicate and reveal these existing community sign-practices and understand their relation to more interventionist design approaches. As we set out from the beginning, theory-practice (towards praxis) relies on this active learning in context.

Whilst, participants often pointed to readymade organisational designs, deeper exploration into practices and observations point to a multifariousness at their core. ’Winnability’, in the CUK context, constructs what is possible, and makes other things ‘impossible’ through lack of pursuit, while the Outlandish discussion on manipulation challenges the possibilities of relationship expectations, (re)framing these communities into socio-political ontologies. ‘Construction of the possible’ allows us to see how and why moves towards radicalism can become tempered in their application and the implications for design practice. The maintenance required for stability (of process, of practice, of institutions) exists because it has something to work against, and this is the space where countering works, by design. We must account for the mercurial possibilities of intent embedded in designing against intention (praxis).

Design theory has long perpetuated ideas that imply intent is unequivocally realisable and invoked in a deterministic way (Escobar Citation2018). Yet, the doubleness at the heart of our analysis is that the signification that sustains communities also reveals instances of interruption or dissolution. Recognising this demands that we accept that these interruptions are often outside of the purview of designer/ly intent. This understanding is necessary for design practices concerned with ontological redirection (Fry Citation2017); there is no fixed meaning, only the illusion of fixedness that is maintained by the interpretant(s), within relationships and everyday moments. Our work here also illuminates how design tasks we were requested to undertake by collaborators earlier in the project would have benefited from knowledge of how significantly such discourses frame these communities, such as a design for policy workshop to inform a potential set of migrant policy tasks. At the same time, counter-design supported by semiotics affords us a toolbox to understand meaning-making in design activity and context as much more complex than so far taken, in turn asking challenging questions of co-researcher solidarities.

We should then be cautious of how our claims of complicating might wrongly imply that the issues affecting the communities with whom we worked are solely a matter of critical practice or critical interpretation, or to be misconstrued as apologists for the realities of capitalist exploitation. Such relativist interpretations can be leveraged as dismissals only to hinder a serious consideration of alternatives or indeed to obfuscate un-intentional outcomes of design and their detrimental effects on the web of life.

Still, co-design may be a site of confluence for discussing the intersections of these approach attributes: a focus on relationships and practices of countering for radicalism, analysed and revealed through contextualised, specific moments of semiosis. Radicality is necessarily an amorphous concept, a praxis broadly defined according to the desire of its practitioners, based on an ethical questioning of norms. The true complexity of radical thinker-doers works within and beyond existing organisational structures and is a concept those outside of academic institutions have long upheld (Red Wing Citation2018, Rivera Cusicanqui Citation2012). Yet, radicality also perhaps suffers from attempts to deconstruct its elements, rather than understanding and feeling how it works in place as a constant re-construction of possibilities, where those might have been erstwhile invisible. This, again, requires attention to small meaning-making moments, which our tentative countering approach seeks to do.

Ethics

Ethics approval for research with human subjects was granted by the Loughborough Ethics Online (LEON) Committee, number 2021–4335–3025.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdulla, D., A. Ansari, E. Canli, M. Keshavarz, M. Kiem, P. Oliveira, and T. Schultz. 2019. “A Manifesto for Decolonising Design.” Journal of Future Studies 23 (3): 129–132. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.201903_23(3).0012.

- Ansari, A. 2019. “Decolonizing Design Through the Perspectives of Cosmological Others: Arguing for an Ontological Turn in Design Research and Practice.” XRDS: Crossroads, the ACM Magazine for Students 26 (2): 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1145/3368048.

- Beck, E. E. 2002. “P for Political: Participation is Not Enough.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 14 (1): 77–92. https://aisel.aisnet.org/sjis/vol14/iss1/1.

- Benston, M. (1969) 2019. “The Political Economy of Women’s Liberation.” Monthly Review 41 (7): 31–44.

- Björgvinsson, E., and M. Keshavarz. 2020. “Partitioning Vulnerabilities: On the Paradoxes of Participatory Design in the City of Malmö.” In Vulnerability in Scandinavian Art and Culture, edited by A. M. Dancus, M, Hyvönen, and M. Karlsson, 247–266. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bogost, I. 2010. Materialisms: The Stuff of Things is Many. Ian Bogost, blog. http://bogost.com/blog/materialisms/.

- Bonhomme, E. 2022. “Black Radical Design: Bringing a Vital Legacy of Visual Culture to Technology Worlds.” Interactions 29 (1): 20–22.

- Borrelli, L., P. Pinkerton, H. Safouane, A. Jünemann, S. Göttsche, S. Scheel, and C. Oelgemöller. 2022. “Agency within Mobility: Conceptualising the Geopolitics of Migration Management.” Geopolitics 27 (4): 1140–1167. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2021.1973733.

- Bryant, L. R. 2011. The Democracy of Objects. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Conway, J., and J. Singh. 2011. “Radical Democracy in Global Perspective: Notes from the Pluriverse.” Third World Quarterly 32 (4): 689–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2011.570029.

- Costanza-Chock, S. 2020. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- De Certeau, M. 1988. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Doucet, I. 2015. The Practice Turn in Architecture: Brussels After 1968. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Escobar, A. 2018. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Freire, P. (1970) 2005. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Reprint, London, England: Penguin Classics.

- Fry, T. 2017. “Designs For/By the Global South.” Design Philosophy Papers 15 (1): 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/14487136.2017.1303242.

- Hooks, B. 2001. All About Love. New York: Harper Collins.

- Huybrechts, L., H. Benesch, and J. Geib. 2017. “Institutioning: Participatory Design, Co-Design and the Public Realm.” CoDesign 13 (3): 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2017.1355006.

- Jacobs, J. (1961) 1992. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. NewYork: Vintage Books.

- Kimbell, L. 2009. “Design Practices in Design Thinking.” European Academy of Management, Liverpool, 1–24.

- Kjærsgaard, M. G., H. Joachim, C. S. Rachel, T. V. Kasper, B. Thomas, and O. Ton. 2016. “Introduction: Design Anthropological Futures.” In Design Anthropological Futures, edited by V. K. T. Rachel Charlotte Smith, M. G. Kjærsgaard, T. Otto, J. Halse, and T. Binder, 1–16. London: Bloomsbury Academic .

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2019. “Doing Critical Discourse Studies with Multimodality: From Metafunctions to Materiality.” Critical Discourse Studies 6 (5): 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1556173.

- Lugones, M. 2010. “Toward a Decolonial Feminism.” Hypatia 25 (4): 742–759. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40928654.

- Mareis, C., and N. Paim. 2021. Design Struggles: Intersecting Histories, Pedagogies, Perspectives. Amsterdam: Valiz.

- Marx, K., and F. Engels. (1848) 1967. “The Communist Manifesto.” Trans. Samuel Moore. London: Penguin 15 (10): 9780822392583–049. 1215.

- Matrix. (1984) 2022. Making Space: Women and the Man-Made Environment. London: Verso.

- Murphy, K. M. 2016. “The Aesthetics of Governance: Thoughts on Designing (And) Politics.” Journal of Design Strategies 8 (1): 23–28.

- Peirce, C. S. 1955. Philosophical Writings of Peirce. New York: Jutus Buchler.

- Petcoff, A. n.d. “The Problem with Saul Alinsky.” Jacobin. Accessed May, 2017. https://jacobin.com/2017/05/saul-alinsky-alinskyism-organizing-methods-cesar-chavez-ufw.

- Prendeville, S., A. Carlton-Parada, V. Gerrard, and P. Syperek. 2022. “From Publics to Counter-Publics- Design Politics of Participation.” In Participatory Design Conference 2022, Vol. 1, pp. 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1145/3536169.3537795.

- Prendeville, S., P. Syperek, and L. Santamaria. 2022. “On the Politics of Design Framing Practices.” Design Issues 38 (3): 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1162/desi_a_00692.

- Querejazu, A. 2021. “Cosmopraxis: Relational Methods for a Pluriversal IR.” Review of International Studies 48 (5): 875–890. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210521000450.

- Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies 21 (2–3): 168–178.

- Rai, A. S. 2019. Jugaad Time: Ecologies of Everyday Hacking in India. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Red Wing, S. 2018. “Keynote Debate 3: Whose Design?” Design Research Society Conference, 25-28 June. [video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wuf91I247b8.

- Rivera Cusicanqui, S. 2012. “Ch’ixinakax Utxiwa: A Reflection on the Practices and Discourses of Decolonization.” The South Atlantic Quarterly 111 (1): 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-1472612.

- Roth, W.-M., and Y.-J. Lee. 2007. “Vygotsky’s Neglected legacy”: Cultural-Historical Activity Theory.” Review of Educational Research 77 (2): 186–232. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654306298273.

- Runnels, D. 2019. “Cholo Aesthetics and Mestizaje: Architecture in El Alto, Bolivia.” Latin American & Caribbean Ethnic Studies 14 (2): 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2019.1630059.

- Saussure, F. M. (1959) 2011. Course in General Linguistics. Translated by Wade Baskin. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wainwright, J. 2022. “Praxis.” Rethinking Marxism 34 (1): 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08935696.2022.2026749.

- Winschiers-Theophilus, H., T. Zaman, and C. Stanley. 2019. “A Classification of Cultural Engagements in Community Technology Design: Introducing a Transcultural Approach.” AI & SOCIETY 34:419–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-017-0739-y.