ABSTRACT

Strategic flood risk management of river catchments involves significant increases in the complexity both of the contents (e.g. the aims and measures) of a given strategy and also its social, spatial, and temporal scales. Conceptually, flood risk management research to date has underestimated the importance of time and temporality. This paper, which is based on ‘historical Institutionalism,’ introduces a temporal lens to focus on strategic flood risk management; it highlights issues of duration and timing as well as tempo and change in tempo with respect to the implementation of measures to reduce flood risk at catchment level. The application of a temporal lens is illustrated through empirical research into strategic flood risk management for the medium-sized Aist river catchment in Austria. The paper uses a longitudinal qualitative research design to analyze the changes in strategic flood risk management in the catchment. The analysis shows that strategy efforts in reaction to an extreme flood event in the catchment in August 2002 can be differentiated into three phases. Phase 1 is characterized by the design of ambitious catchment-wide management; Phase 2 by struggles to implement the strategy due to institutional conditions and protests by citizens; and Phase 3 by redesign of the initial strategic plan to make it less ambitious and by changes to the actor constellation supporting the plan. The present paper offers a process-oriented institutional explanation for this pattern of phases, and it highlights issues of timing and tempo. It concludes with general suggestions for enhancing the temporal dimension in flood risk management.

1. Introduction

Flood risk management has changed in recent decades, with the use of new instruments like catchment-wide management plans becoming more prominent. Catchment-wide management plans aim to reduce flood risk while realizing co-benefits, such as restoration of biodiversity, improvement of individual well-being, and provision of carbon storage. As planned measures are often implemented on privately owned land (Thaler et al. Citation2023), the realization of flood management plans at a catchment-wide level requires a strategic perspective; various resources are needed to achieve this, including individual capacity, knowledge, and time. Time and temporality highly influence the design and implementation of plans (e.g. there can be a ‘window of opportunity’ for plans and their implementation). Longitudinal approaches are well suited to analyzing strategic flood risk management with, in, and over time. They are, however, rarely used in flood risk management research.

Against this background, this paper makes two contributions: First, it draws on ‘historical institutionalism’ (Gryzmala-Busse Citation2011, Mahoney Citation2021) to enhance the conceptual analysis of strategic flood risk management with regard to time and temporality. We call this the application of a temporal lens to strategic flood risk management. In conceptual analysis on strategic flood risk management, temporal categories are little used. Of course, some temporal references are often necessary, especially to present empirical results of case study work and quantitative analysis (e.g. temporal references of a specific flood event). Historical institutionalism is especially well suited to providing a temporal lens:(i) because of its research tradition of considering the ideas and interests that drive social action; and (ii) because of its process-as-sequence view of how to empirically describe and explain both stability and changes in social relations (Immergut Citation2006, Fioretos et al. Citation2016, Mahoney Citation2021).

Second, the paper illustrates the application of a temporal lens in case study work based on previous empirical research regarding strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment in Austria. The analysis focuses on issues of duration, timing, and tempo. Addressing issues of duration leads to a phase analysis that distinguishes between three phases over a whole observation interval of 19 years of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment. In Phase 1, after an extreme flood event in August 2002, actors designed an ambitious new catchment-wide flood risk management plan to reduce flood risk. In Phase 2, key actors encountered severe implementation struggles, and in Phase 3 changes were made to the actor constellation, a lower ambition and safety level was set, and the design of measures to reduce flood risk underwent significant change. This paper explains these changes based on ‘historical institutionalism,’ in effect, by applying a temporal lens to strategic flood risk management.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 briefly introduces the concept of strategic flood risk management at catchment level and why this concept is, more or less explicitly, related to a temporal dimension in research and practice. Section 3 argues for the application of a temporal lens to flood risk management research and highlights four selected categories (duration, timing, tempo, and change in tempo). Section 4 presents the case study results. Section 5 specifies the benefits of applying a temporal lens in strategic flood risk management research and practice.

2. The concept of strategic flood risk management at catchment level

The debate regarding how to address flood risk has changed drastically since the 1990s (Seebauer et al. Citation2023, Thaler and Penning-Rowsell Citation2023), and policy changes have been driven by different extreme flood events across the globe, by climate change, and by societal changes. We have observed a change away from flood protection toward flood risk management and from ‘fighting against nature’ toward ‘living with nature’ (Collentine and Futter Citation2018). Change has also been manifest in new strategies to reduce potential risk (Thaler et al. Citation2019). Especially since the 1990s, there has been a shift in terms of the selection of risk reduction measures (Kundzewicz Citation2002, Hutter Citation2007, Johnson and Priest Citation2008, Wiering et al. Citation2017, Citation2018, Rauter et al. Citation2020). The use of technical (or structural) mitigation measures, such as dikes and dams, have come under pressure, as they can no longer cope with prevailing societal needs in the face of extreme and compound weather and climate events, biodiversity losses, climate change mitigation, and improvement of individual well-being (Thaler and Penning-Rowsell Citation2023).

These policy changes are related to the introduction of new European directives, such as the implementation of the EU Water Framework Directive in 2000 and the EU Floods Directive in 2007 (EU Citation2000, Citation2007). For example, all technical mitigation measures are deemed to conflict with the goals of the EU Water Framework Directive, by hindering the attainment of a good ecological status for all European water bodies and by changing river geomorphology (Wharton and Gilvear Citation2007). Moreover, technical mitigation measures are in conflict with the aims of the EU Floods Directive (EU Citation2007) in that they have the potential to transfer a flood wave toward downstream communities, thus raising the prospect of larger losses and damages. As technical measures limit adaptation to extreme events and indicate negative consequences for biodiversity, a radical rethink is required to ascertain which strategies might be the most appropriate for reaching these different goals (Seebauer et al. Citation2023, Thaler et al. Citation2023).

One approach would involve moving away from classical technical mitigation measures toward a wide range of different strategies, such as catchment-wide management plans (Eder et al. Citation2022, Löschner et al. Citation2022). Catchment-wide management plans provide a holistic perspective of a catchment, in terms not only of hazard and risk modeling but also of risk management strategies (Thaler et al. Citation2016, Hartmann et al. Citation2022). Catchment-wide management plans have the advantage of implementing risk reduction strategies in places ‘where the rain falls’ (Dadson et al. Citation2017, Collentine and Futter Citation2018, Thaler et al. Citation2023). Catchment-wide risk management strategies foresee the realization of flood storage or natural flood management (NFM), for example, land use change (such as afforestation, creation of buffer strips and hedges, renaturation of rivers, support for wetlands, creation of ponds), changing farming practice (such as no-tillage practice) or controlled flood retention measures (Dadson et al. Citation2017, Lane Citation2017, Thaler et al. Citation2023). Furthermore, catchment-wide management plans can include various societal targets and needs, such as restoring biodiversity, providing spaces for carbon storage, increasing individual well-being, and supporting other ecosystem services, such as cultural ecosystem services (Thaler et al. Citation2023).

To realize catchment-wide management strategies, however, individual leadership quality (or even transformative capacity), innovation in knowledge resources, and sensitivity to issues of time and temporality within the public administration and from policymakers are needed. Some major reasons for this are:

Today’s more intensive and more complex involvement of stakeholders with different interests and power potentials;

Measures being implemented on privately owned land, raising the question as to how such land can be mobilized and secured for flood risk management purposes and if ongoing policy instruments are actually adequate for achieving this goal; and

The need to face the reality of upstream – downstream conflicts between local politicians and citizens; downstream communities would be the main gainers from these measures, while upstream communities would have to provide land and would receive almost no benefits. In particular, the use of privately owned land could have negative consequences for the private land owner, such as loss of income due to more regular flood or maintenance costs, which often are only partially compensated for by the public administration (Thaler et al. Citation2023).

Catchment-wide flood risk management, therefore, calls for strategies to be drawn up with regard to all aspects of risk level, spatial and temporal scales, land uses, geomorphology, and political and individual interests (Thaler et al. Citation2016, Citation2023). Similar to spatial planning strategy for cities and regions (Albrechts Citation2004, Citation2006, Healey Citation2009, Hutter et al. Citation2019), flood risk management at catchment level emphasizes specific activities:

Creation of long-term visions that support incremental improvements;

Mobilization of actors and actions instead of ‘detached’ plan-making;

Combination of formal and informal processes of strategy-making; and

Maintenance of continuous connections between the contents and processes of flood risk management.

Strategic flood risk management in this sense depends on governance arrangements and institutional settings. Institutions play a crucial role in terms of how to engage with nonstate actors and stakeholders within the decision-making process, how to use formal and informal processes, and how to integrate strategy into the public administration logic.

According to Hodgson (Citation2006, p. 2), institutions are ‘the kinds of structures that matter most in the social realm: they make up the stuff of social life.’ In flood risk management, for example, institutions provide the system boundaries and, through institutionalized tasks and responsible actors, organize how flood risk management works in practice. Adapting or changing parts of the institutional framework or institutional design would affect various areas of our daily life, the process of managing flood risk management, and the goals of flood risk management itself (Buitelaar et al. Citation2007, Thaler et al. Citation2023).

Institutional change can occur through innovation (Redmond Citation2003). According to Pollitt and Hupe (Citation2011) innovation has involved long-term agenda-setting with the key goal of improving the current situation. In the context of institutions, the term institutional innovation was introduced against a background of changing institutional settings or creation of new ones (Lindner Citation2003, Redmond Citation2003). Raffaelli and Glynn (Citation2015, p. 1) define institutional innovation as ‘novel, useful and legitimate change that disrupts, to varying degrees, the cognitive, normative, or regulative mainstays of an organizational field.’

In theory, strategic flood risk management at catchment level and institutional innovation co-evolve over time. It is thus still an open question as to whether institutional change in general and institutional innovation in particular occur more often in the form of revolutionary change (as a ‘punctuated equilibrium’) or as gradual institutional change (Mahoney et al. Citation2016, Mahoney Citation2021). Either way, strategic flood risk management and institutional innovation are characterized by complex temporal dimensions. Research on strategic flood risk management often shows these dimensions to be more implicit than explicit. In the following, therefore, we will indicate what it means to apply a specific temporal lens to strategic flood risk management. This is important for understanding if the implementation of measures of strategic flood risk management needs to be improved.

3. Applying a temporal lens to the implementation of strategic flood risk management

In empirical research on strategic flood risk management, addressing issues of time and temporality cannot be avoided. Temporal questions like ‘When did this flood happen?’ and ‘How long will it probably take to implement a new strategy?’ are typical questions in strategic flood risk management research. In contrast, on a conceptual level, issues of time and temporality often attract less attention than they deserve. Applying a temporal lens means first and foremost placing temporal categories in the foreground of conceptual analysis (Hutter and Wiechmann Citation2022).

Research on time and temporality in social action offers a wide range of concepts that can be used for applying a temporal lens to strategic flood risk management. For instance, Adam (Citation2004, p. 144) proposed the sociological concept of a ‘timescape’ to consider the contextualized complexities of temporal categories in social action (time frames, process, irreversibility, tempo, timing, time point, time patterns, sequence, time extensions, as well as time past, present, and future).

The present paper follows ‘historical institutionalism’ to consider time and temporality (Gryzmala-Busse Citation2011, Mahoney Citation2021). Temporality is important for understanding the causality of path dependence and, as a contrasting process pattern, gradual institutional change (Mahoney et al. Citation2016, Mahoney Citation2021). Historical institutionalism provides conceptual and theoretical arguments to guide empirical analysis and also in case study work, to facilitate results that are relevant for a wider population of cases.

Gerring (Citation2017, p. 222) labels case study work as a two-level game: ‘Case studies typically partake of two worlds. They are studies of something general, and of something particular … . Part of the study is “idiographic” and another part “nomothetic”.’ A standard historical approach would often emphasize the particular, whereas this paper seeks to move toward a balance between the worlds of the general and the particular.

Overall, there are four selected categories where a temporal lens can be applied to strategic flood risk management. As duration is the most basic concept for understanding time and temporality, it often comes first on the list of temporal categories (e.g. Flaherty Citation2011):

Duration is defined as the temporal length of an event or a process. Historical research shows that processes may have especially complex and ambiguous temporal boundaries. Research on flood risk management, however, can often be grounded with reference to a significant flood event. The event reference and the time that has unfolded until the relevant research commences jointly determine the observation interval for investigation (Poole Citation2004).

Timing is defined as a position on a temporal timeline. Timing refers to at least two processes of different kinds and contexts. For instance, local activities emerge during policy changes at the national and European levels. Events on these three levels intersect and this intersection point determines the timing of local activities (Geels and Schot Citation2007).

Tempo (or speed) refers to the amount of change per unit of time, which can only be determined if the unit of change and time are specified thoroughly. Issues of time and temporality have gained prominence in recent years due to the expectation that significant (i.e. more than incremental) change is urgently needed if the changing context conditions of flood risk management are to be considered, for instance, climate change and urbanization processes that lead to increases in damage potentials in flood-prone areas. Urgency of change and fast action seem to be ‘natural twins.’ There are also scholars that call for the consideration of both fast and slow efforts of urban area planning to take into account climate change mitigation and adaptation (Hutter and Joshi Citation2024).

Acceleration and deceleration are to be understood as changes in tempo. Gryzmala-Busse (Citation2011, pp. 1269–1270) highlights acceleration and defines it as a ‘derivative of velocity with respect to time.’ Acceleration is especially important when one is considering the characteristics of dynamic processes like cascades, panics, and revolutionary change (Gryzmala-Busse Citation2011).

Duration, timing, and tempo are to some extent independent aspects of temporality (Flaherty Citation2011, Mahoney Citation2021). Analyzing the duration of implementing measures does not inform us about the speed of action and how timely this action is. Fast action on a specific institutional level is not always effective, but depends for its effectiveness on processes at other levels. The timing of activities may, in principle, be ‘right,’ but actors may act too slowly to exploit a ‘window of opportunity’. When a temporal lens is applied to strategic flood risk management, multiple temporal categories and the relations between them need to be considered, not just a single one.

The next sections present case study results (i) to illustrate how these four categories help to advance empirical research on flood risk management and (ii) to specify the benefit of a temporal lens in conceptual and empirical research.

4. Strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment in Austria: a longitudinal analysis as illustrative example

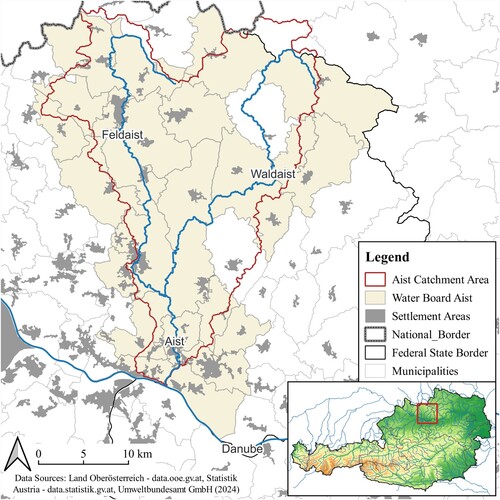

The Aist catchment is located in the Austrian federal state of Upper Austria and includes more than 29 local authorities within a size of 642.5 km² (). The catchment, which has mainly rural characteristics, was heavily affected by a 1-in-300-year flood event in August 2002. This flood event caused estimated direct damage of more than EUR 140 million (Puchinger and Henle Citation2007, Habersack et al. Citation2012). Most damage was recorded in the lower part of the catchment, mainly in the peri-urban local authority of Schwertberg.

The flood event triggered the emergence of new policy entrepreneurs and new ideas regarding the management of flood risk in the Aist river catchment. Event-driven change discussions started with a new holistic management approach in Austrian flood risk management policy. This was mainly driven by a few policy entrepreneurs. According to Thaler et al. (Citation2020, p. 3) policy entrepreneurs are usually individuals ‘who promote specific topics by raising awareness, pressing ideas, bringing solutions to the table and building coalitions’ (Thaler et al. Citation2020, p. 3). Based on the flood event, the policy entrepreneurs sought to implement a strategic catchment-wide approach. Due to this, large time delays were created, especially due to the planned implementation of upstream – downstream risk reduction measures. Over time, the initial strategic management plan was significantly redesigned, one key difference being the exclusion of a wide range of different management options in favor of a more ‘classical’ flood risk management concept.

The application of a temporal lens sheds some new light on this management case:

Duration: The whole observation interval of the analysis is 19 years (2002 until 2021). We argue that this may count as a typical observation interval for understanding strategic flood risk management over time. It is plausible to differentiate the whole observation interval into three phases due to changes in the three management dimensions of context, process, and content (see below).

Timing: Timing analysis focuses on the emergence of new policy entrepreneurs over the whole course of strategic flood risk management. In this case, new policy entrepreneurs emerged in reaction to the flood event in the year 2002 (Phase 1) and again after implementation struggles in the year 2013 and onwards (Phase 3).

Tempo/change in tempo: Strategy efforts are investments to ease and accelerate future processes of decisions and actions. Strategists seek to reduce transaction costs in policy and practice and the actors involved are able to agree on priorities with regard to the contents and processes of strategy-making (Healey Citation1997, Citation2009). However, the case of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment shows that the opposite may also be true (Weick Citation1993): strategy efforts lead to delays and to the deceleration of decisions and actions. The case study below explores in more detail why this was the case.

In the following, comments are made first on the research design and methods of the case study on strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment. Second, some information on the policy background of flood risk management in Austria is given, especially on institutionalized tasks and actors. Third, the case study explores in more detail how a temporal lens can be applied. The conclusion attempts to address the benefits of such an application.

4.1. On research design and methods

Surprisingly, longitudinal research is not commonly used in flood risk management and strategic planning research. A longitudinal research design includes repeated observations over a certain period of time, something which is essential for analyzing and understanding policy dynamics based on various endogenous and exogenous factors (Brody et al. Citation2009, Archer et al. Citation2017, Seebauer and Babcicky Citation2021). One type of longitudinal research is the reanalysis of the same research questions and themes after a certain period of time, such as returning to the same study region a couple of years after the first research activities to revise the results (Archer et al. Citation2017). Our research design corresponds to this specific kind of longitudinal research design. We used a qualitative research design based on the assessment of policy and legal documents and semi-structured interviews. We conducted three waves of interviews with interviewees in the same regional and local geographical locations in the Austrian federal state of Upper Austria within the Aist catchment. We applied the same methods in three selected ‘waves’: 2007, 2012, and 2021. Overall, we interviewed 16 experts and policymakers as well as stakeholders at regional and local level (indicated as i1, i2, i3 … . in the paper).

Interviewees were selected based on their key involvement in creating the catchment-wide management plan for the Aist river. Some interviews were conducted with the same participants between 2007 and 2021 (see Appendix). Overall, we conducted 24 interviews. Some actors related to different local authorities changed over the period, especially local politicians who retired or were deselected after local political elections (local elections were held in 2009 and 2015).

The interview guidance included the same themes of questions. Some elements, however, were added or slightly adapted to changed circumstances. The main themes on the list of questions included: motivation for selecting a catchment-wide management approach; who the key actors are; aspects of responsibility sharing; the barriers to, and drivers of, the design and implementation of measures; changes in the strategy and plan; and learning processes; and endogenous and exogenous influences affecting the realization of the creation and implementation of catchment-wide flood risk management strategies in the selected study area.

Interviews were conducted face-to-face, but during the Sars-CoV-02 pandemic restrictions, they were held online as Zoom meetings. All interviews lasted from 45 minutes up to 2 hours, resulting in 10–15 transcript pages per interview. Interviews were conducted in German. For the analysis, we used a grounded-theory approach and a MAXQDA software package. The first step included deductive coding based on the literature on strategic planning and policy learning; and we then extended our coding tree inductively.

4.2. Tasks and actors in flood risk management in Austria

Austrian flood risk management is organized within a federal system with a large array of different laws, regulations, and strategies at the national, regional, and local levels (i1; i2; i6; i7; i12; i13; i15). As a result, a wide range of different actors and stakeholders with various permissions, roles and responsibilities, funding schemes, and unequal power relationships are involved in the flood risk management system (i2; i6; i7; i13). The involvement of different actors, stakeholders, and citizens at different political levels is dependent on the tasks presented within the flood risk management domain (prevention, defense, mitigation, preparation, or recovery).

Prevention, such as land use planning, is mainly managed by local authorities. However, the regional authority of Upper Austria plays a marginal role in the decision-making process and is more involved in providing information and support in the design of the local land use development plans (i14).

In the case of defense and mitigation, the core actors are the Forest Engineering Service in Torrent and Avalanche Control [Wildbach – und Lawinenverbauung] (WLV) and the Federal Water Authorities [Direktion Umwelt und Wasserwirtschaft] (BWW). The WLV is responsible for the mountain river catchments across Austria and for dealing with torrential floods, avalanches, and rock falls. The BWW manages the main rivers, mainly fluvial floods.

Local authorities, which contribute up to 20 percent of the total costs (80 percent of the costs are provided by the national and regional authorities), are responsible for the maintenance costs of the technical mitigation measures. In addition, local authorities are the key actors with private land owners in negotiations to use privately owned land for implementing retention basins (i1; i6; i12; i13; i15). Local authorities are also responsible for emergency management in close relationship with the different blue-light organizations (i6; i7; i10).

Finally, in the case of recovery, citizens are largely responsible for the rebuilding phase. The regional authority does, however, provide disaster-aid payments after an event. The level of compensation paid by the public administration is between 20 and 50 percent and is co-administered by the regional and local authorities (i6; i7).

4.3. Three phases of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment

As mentioned, the case analysis has a total observation interval of 19 years of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment. This interval is defined from the present point in time looking retrospectively at the strategy process that began with the flood event in the year 2002. Short – and long-term outcomes of the strategy process differ significantly. Phase analysis of the whole observation interval shows that new policy entrepreneurs reacted to the flood event in the year 2002 with the expectation of implementing a new strategic catchment-wide approach to managing flood risk. In the long term, this initial idea for change did not play out. This can be seen in greater detail by distinguishing between three phases of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment:

Phase 1 is characterized by the emergence of new policy entrepreneurs, the creation of inter-communal cooperation, and a new strategy flood risk management plan for the Aist;

Phase 2 is characterized by an attempt to implement 25 technical retention basins in conformance with the strategic plan,

Phase 3 is characterized by a lowering in the level of ambition of the strategic flood risk management plan and the redesign of the plan.

summarizes the content, process, and context features of the three phases.

Table 1. Three phases of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment.

4.4. Phase 1 (2002– 2007)

Following the extreme flood event in the River Aist catchment area in August 2002, regional and local authorities introduced a new flood risk management strategy for the whole catchment. The idea of implementing a catchment-wide management plan surfaced quite early on after the event. The creation of an inter-communal cooperation exercise (including 27 local authorities) was driven mainly by a number of policy entrepreneurs from the regional authority (particularly the WLV) and various mayors from the lower part of the catchment (e.g. the mayors of Schwertberg and Gutau who later headed up the cooperation) (see interviews i2; i3; i4; i5; i6; i7; i12; i15).

In particular, the policy entrepreneur from the WLV played a crucial role in phases 1 and 2. He was the main architect of the Aist strategic flood risk management plan and persuaded the various mayors to collaborate, thereby encouraging the creation of inter-communal cooperation and the design of the collaboration’s organizational settings (i2; i6; i7; i8; i12; i15).

In our view the WLV policy entrepreneur interpreted the flood event of 2002 as a kind of ‘window of opportunity’ to establish a new catchment-wide strategic flood risk management approach supported by local actors. However, not all local authorities joined the cooperation. Two local authorities refused to collaborate (i6; i7; i8; i15). The duration from developing a strategic perspective to the creation of an upstream – downstream collaboration was thus only six years after the 2002 flood event.

The first Aist strategic flood risk management plan included an ambitious holistic perspective. The plan integrated various topics that needed to be addressed by the public administration. One advantage was that this was the very first integrated perspective to include risk reduction measures dealing with river floods and mountain hazard processes (e.g. torrential flooding, debris flow etc.). Consequently, the new strategy plan encompassed a wide range of measures (i1), as follows:

25 technical retention basins were established across the whole catchment with the aim of using agricultural land in the upper part of the catchment to reduce the risk to residential and nonresidential areas in the lower part of the catchment;

a forest management concept was instituted to reduce the risk of future woody debris flow events,

‘small’ mitigation measures such as property-level flood risk reduction measures and linear dams were undertaken; and

a new early warning system was implemented.

Technical retention basins were planned only on privately owned land – mainly grassland managed by farmers. Private land owners were offered compensation based on the possibility of their land being used for inundation as well as for any damage caused by future events (i1; i2). Local authorities downstream were also expected to largely finance the costs for the realization of the measures (i1). Here, the aspect of timing played a central role in the development of the upstream – downstream collaboration. The use of the 2002 flood event opened a new perspective on how to manage the flood risks within the catchment. To reduce the risk of failure, the policy entrepreneurs changed the tempo in order to integrate the wide range of different actors within the planning process.

4.5. Phase 2 (2008–2012)

Phase 2 is characterized by efforts, on the one hand, to put planned measures into practice, and on the other, to identify barriers to implementation, especially local protests against implementing the 25 new technical retention basins.

The Aist inter-communal cooperation managed to implement the different ‘small’ mitigation measures mentioned above. It did not, however, manage to implement the 25 technical retention basins or to encourage private forest owners to change their stock of trees from spruce to deep-rooting trees (i1; i15). The key barrier was that private land owners often rejected the financial and non-financial incentives offered by the public administration (i6; i7; i10; i11). The reasons were diverse, such as potential income losses, problems with the local mayor or neighbors, uncertainty about how to maintain the measures and the time period needing to be covered, or individual interests (i6; i7; i8; i9; i10; i11; i12; i13; i14; i15). A crucial aspect was the negotiation process, when the head of the inter-communal cooperation was negotiating with private landowners. What is more, the creation of a citizen-led group also encouraged local protests against the implementation of the 25 technical retention basins across the catchment. The change in tempo (caused by the citizen-led group, as well as the negative attitude of private land owners) led to delays in the implementation process. This reduction in tempo caused changes within the planning process, such as the location and size of the retention basins, as well as the focus of the risk reduction strategy. The main focus was the implementation of ‘small’-scale mitigation measures, such as small dams, bank fortifications, or property-level flood risk adaptation (PLFRA) measures in public buildings (i6; i7; i8; i9).

In terms of key actors, Phase 2 is characterized by three main actors (two civil servants and one policymaker): the WLV policy entrepreneur, the head of water authorities responsible for flooding, and the mayor of Gutau (i6). Given the conflicts and barriers characteristic of the second phase, the BWW encouraged a broader participation process, a Flussdialog (river dialogue) intended to lead to a reevaluation of the new management plan developed in Phase 1 (i6; i12; i15). Actors included in the Flussdialog agreed to redesign the first Aist strategic flood risk management plan.

4.6. Phase 3 (2013–2021)

Phase 3 refers to the time after the conclusion of the Flussdialog in 2012. Here, the timing of the dialogue played an important role. In this phase, some policy entrepreneurs lost their political ‘voice’ and role in the decision-making process (i6; i12; i15). There were significant changes to the role of the WLV and its policy entrepreneur (i6; i15). The WLV was mainly excluded from redesigning the Aist flood risk management plan (i15). The implementation of measures was planned for the years 2024–2025 (i6). With regard to the contents of the plan, the main result of the Flussdialog was the redesign of the original Aist strategic flood risk management. The new plan foresees the implementation of further property-level flood risk adaptation measures. Most controversial was the reduction of the technical retention basins from 25 to seven. The lower number of retention basins consequently led to a lower level of planned risk reduction (a 1-in-100-year event instead of a 1-in-300-year flood).

The lower number of technical retention basins led, first, to a lower number of affected private landowners and, second, to the overall costs for flood risk management being reduced (i6; i12). Actors agreed to refrain from integrating flood and mountain hazards, which is in the line with the Austrian funding scheme in flood risk management (i6; i7; i10; i11; i12; i15). The BWW mainly funds projects up to a design level of only 1:100. Additionally, the new flood risk management plan largely excluded the forest management concept (i6; i15; i16).

In terms of key actors, the third phase included two main actors (one civil servant and one policymaker): the head of the water authorities responsible for flooding and the head of the inter-communal cooperation (i6).

We propose that timing effects are important for understanding the third phase. Key actors interpreted the third phase (against the background of implementation struggles in the second phase) as the ‘right time’ to adopt a more focused, ‘classical,’ and more acceptable approach toward managing flood risk of the Aist river catchment.

4.7. Phases 1–3: Moving toward a process-oriented institutional explanation

The whole strategy process for the Aist river catchment probably does not correspond to the concept of path dependence in which event-triggered decisions during a relatively short time interval are confirmed and reconfirmed in subsequent processes of longer duration to implement a new strategy of flood risk management. Hence, in future work on a strategy process for this case, it would be plausible to analyze the temporality of change in flood risk management as a gradual change process (Mahoney et al. Citation2016).

This leads to the suggestion that cases of event-driven change in flood risk management in medium-sized river catchments could be characterized primarily either by processes of path dependence or gradual change, perhaps gradual transformative change (Mahoney et al. Citation2016, Mahoney Citation2021). Use of historical institutionalism to grasp temporal processes would serve as an important framework for generalizing from a range of case studies so as to elicit an institutional explanation.

In the case of strategic flood risk management for the Aist river catchment, the initial catchment-wide management plan (designed in the first phase) included a strategic perspective of broadly managing the river with due consideration to a wide range of measures to reduce the potential losses of future flood events. The first strategic plan also foresaw the realization of a wide range of further societal goals.

Over the years, the initial new Aist catchment-wide management plan led to various delays, conflicts, and redesign processes. As a result, most of the initial ideas were rejected. Over time, a transformative new strategic flood risk management process instituted directly after the extreme flood event in the year 2002 turned into a management process characterized mainly by incremental improvements.

We propose that the main reason for the ‘destiny’ of this initial strategic flood risk management plan was due to the ‘misfit’ between strategy and institutions: first, the institutionally grounded refusal of private land owners and protest groups to support and implement measures and, second, the institutional framework of how flood risk management funding is organized within Austria.

In particular, the lack of flexibility within the current institutional framework more likely hinders a more radical approach toward strategic flood risk management at catchment-level. This leads to the general suggestion (Granqvist and Mäntysalo Citation2020) that strategy efforts that do not fit important institutional conditions of limited flexibility decelerate instead of accelerate actions to manage the flood risk of small – to medium-sized river catchments.

5. Conclusion

Understanding how strategies and institutions change is an important means of understanding specific cases of flood risk management as well as for designing and implementing planned change in anticipation of increasing future flood risk or in reaction to specific events like the extreme flood of the Aist river in August 2002. Analyzing change and implementing planned change necessarily involves consideration of time and temporality. However, conceptual analysis with regard to time and temporality has been rather limited in flood risk management research to date. This has ‘downstream consequences’ for empirical analysis of specific cases of strategic flood risk management. We conclude that ignorance of the complex issues of time and temporality in strategic flood risk management research will leave important research potential underused and will probably, in practice, contribute to implementation delays and even implementation failure.

More specifically, some benefits of applying a temporal lens to strategic flood risk management at catchment level are as follows: first, time and temporality are often treated as a more implicit dimension in case study work on strategic flood risk management. We conclude that making the implicit explicit provides opportunities for strategic choices able to focus research on important issues like the expected and actual duration of designing and implementing measures, the timing of change and change agents, and conditions of acceleration as well as deceleration of decisions and actions to manage flood risk of river catchments. Temporally sensitive and ‘truly’ process-oriented longitudinal studies are necessary to gain a ‘realistic’ pictures of how the implementation of strategies for reducing flood risk unfolds in the ‘real world.’

Second, historical institutionalism argues that process-oriented institutional explanations provide important knowledge to identify why in some cases strategy and institutional processes lead to different outcomes than in others. For instance, in the case of strategic risk management for the Aist river catchment in Austria it would be interesting to know the conditions under which the initial strategy effort in Phase 1 could have led to a flood risk management process at catchment level that would have supported the initial highly ambitious and integrative new strategy approach. Perhaps less ambition with similar measures would have been successful; perhaps a different choice of measures right from the beginning would have induced a different process of flood risk management at catchment level. Comparative research on cases with similar starting conditions and different outcomes in the ‘real world’ could lead to important new insights into the implementation of more than simply incremental changes in flood risk management. Such comparative research necessarily involves some systematic treatment of time and temporality in strategies and institutions. It is thus hoped that this paper contributes to future comparative research on strategic flood risk management around the globe.

Reflecting the challenge of following a comprehensive strategic perspective within flood risk management, the paper observes a wide range of different challenges. On the one side, there is a strong push to reach a more comprehensive perspective of flood risk management. In particular, different policy strategies encourage a catchment-wide risk management perspective to implement the most effective and efficient risk reduction measures. On the other side, the Aist case shows a number of barriers that bring about failure to implement the idea of a comprehensive flood risk management perspective. These barriers show how ‘great ideas’ fail over time based on the different barriers that have also evolved over the same time period.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (14.8 KB)Acknowledgments

This paper was realized within the project ‘Pathways – Strategic decision-making in climate risk management: designing local adaptation pathways’ funded by the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund and was carried out within the Austrian Climate Research Program, grant number B960201.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam, B., 2004. Time. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Albrechts, L., 2004. Strategic (spatial) planning reexamined. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31, 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3065.

- Albrechts, L., 2006. Shifts in strategic spatial planning? Some evidence from Europe and Australia. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38, 1149–1170. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37304.

- Archer, L., et al., 2017. Longitudinal assessment of climate vulnerability: a case study from the Canadian Arctic. Sustainability Science, 12, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0401-5.

- Brody, S.D., et al., 2009. Policy learning for flood mitigation: a longitudinal assessment of the community rating system in Florida. Risk Analysis, 29, 912–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01210.x.

- Buitelaar, E., Lagendijk, A., and Jacobs, W., 2007. A theory of institutional change: illustrated by Dutch City-Provinces and dutch land policy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39, 891–908. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38191.

- Collentine, D., and Futter, N.N., 2018. Realising the potential of natural water retention measures in catchment flood management: trade-offs and matching interests. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11, 76–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12269.

- Dadson, S.J., et al., 2017. A restatement of the natural science evidence concerning catchment-based ‘natural’ flood management in the UK. Proceedings of the Royal Society A – Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 473, 20160706. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2016.0706.

- Eder, M., et al., 2022. RegioFEM — applying a floodplain evaluation method to support a future-oriented flood risk management (Part II). Journal of Flood Risk Management, 15, e12758. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12758.

- EU, 2000. Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2000/60/oj [Accessed 15 September 2023].

- EU, 2007. Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the assessment and management of flood risks. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32007L0060&qid=1694786938445 [Accessed 15 September 2023].

- Fioretos, O., Falleti, T. G., and Sheingate, A. 2016. Historical institutionalism in political science. In: O. Fioretos, T.G. Falleti, and A. Sheingate, eds. Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–28.

- Flaherty, M.G., 2011. The textures of time. Agency and temporal experience. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Geels, F.W., and Schot, J., 2007. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy, 36, 399–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003.

- Gerring, J., 2017. Case study research. Principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Granqvist, K., and Mäntysalo, R. 2020. Strategic turn in planning and the role of institutional innovation. In: A. Hagen, and U. Higdem, eds. Innovation in public planning. Calculate, communicate and innovate. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 73–90.

- Gryzmala-Busse, A., 2011. Time will tell? Temporality and the analysis of causal mechanisms and processes. Comparative Political Studies, 44, 1267–1297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010390653.

- Habersack, H., Kristelly, C., and Hauer, C., 2012. Analyse von geplanten Hochwasserschutzmaßnahmen an der Aist in Oberösterreich. Gutau: Hochwasserschutzverband Aist. http://www.hws-aist.at/media/dokumente/121203_GutachtenHabersack.pdf.

- Hartmann, T., Slavikova, L., and Wilkinson, M., eds. 2022. Spatial flood risk management. Implementing catchment-based retention and resilience on private land. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Healey, P. 1997. The revival of strategic spatial planning in Europe. In: P. Healey et al., eds. Making strategic spatial plans. Innovation in Europe. London: UCL Press, 3-19.

- Healey, P., 2009. In search of the “strategic” in spatial strategy making. Planning Theory & Practice, 10, 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903417191.

- Hodgson, G.M., 2006. What are institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, 40, 1–25.

- Hutter, G., 2007. Strategic planning for long-term flood risk management: some suggestions for learning how to make strategy at regional and local level. International Planning Studies, 12, 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563470701640168.

- Hutter, G., and Joshi, N., 2024. Duration and speed of change – applying a temporal lens to just transitions of urban energy systems. Dresden: IOER (Paper under review).

- Hutter, G., and Wiechmann, T., 2022. Time, temporality, and planning – comments on the state of art in strategic spatial planning research. Planning Theory & Practice, 23, 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.2008172.

- Hutter, G., Wiechmann, T., and Krüger, T. 2019. Strategische Planung. In: T. Wiechmann, ed. ARL reader Planungstheorie. Band 2: Strategische Planung – Planungskultur. Berlin: Springer, 13–25.

- Immergut, E.M. 2006. Historical-institutionalism in political science and the problem of change. In: A. Wimmer, and R. Kössler, eds. Understanding change. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 237–259.

- Johnson, C., and Priest, S.J., 2008. Flood risk management in England: a changing landscape of risk responsibility? International Journal of Water Resources Development, 24, 513–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900620801923146.

- Kundzewicz, Z.W., 2002. Non-structural flood protection and sustainability. Water International, 27, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060208686972.

- Lane, S.N., 2017. Natural flood management. WIREs Water, 4, e1211. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1211.

- Lindner, J., 2003. Institutional stability and change: two sides of the same coin. Journal of European Public Policy, 10, 912–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000148360.

- Löschner, L., et al., 2022. RegioFEM – informing future-oriented flood risk management at the regional scale (Part I). Journal of Flood Risk Management, 15, e12754. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12754.

- Mahoney, J., 2021. The logic of social science. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Mahoney, J., Mohamedali, K., and Nguyen, C. 2016. Causality and time in historical institutionalism. In: O. Fioretos, T.G. Falleti, and A. Sheingate, eds. Oxford handbook of historical institutionalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 71–88.

- Pollitt, C., and Hupe, P., 2011. Talking about government: the role of magic concepts. Public Management Review, 13, 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.532963.

- Poole, M.S. 2004. Central issues in the study of change and innovation. In: M.S. Poole, and A.H. Van de Ven, eds. Handbook of organizational change and innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 3–31.

- Puchinger, F., and Henle, A., 2007. Regionalplanungen—ein Instrument zur Umsetzung nachhaltiger Schutzkonzepte. Wildbach- und Lawinenverbauu, 71, 90–99.

- Raffaelli, R., and Glynn, M.A. 2015. Institutional innovation: novel, useful and legitimate. In: C.E. Shalley, M.A. Hitt, and J. Zhou, eds. The Oxford handbook of creativity, innovation and entrepreneurship. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 407–420.

- Rauter, M., et al., 2020. Flood risk management in Austria: analysing the shift in responsibility-sharing between public and private actors from a public stakeholder's perspective. Land Use Policy, 99, 105017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.105017.

- Redmond, W.H., 2003. Innovation, diffusion, and institutional change. Journal of Economic Issues, 37, 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2003.11506608.

- Seebauer, S., et al., 2023. How path dependency manifests in flood risk management: observations from four decades in the Ennstal and Aist catchments in Austria. Regional Environmental Change, 23, 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02029-y.

- Seebauer, S., and Babcicky, P., 2021. (Almost) all quiet over one and a half years: a longitudinal study on causality between key determinants of private flood mitigation. Risk Analysis, 41, 958–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.13598.

- Thaler, T., et al., 2019. Drivers and barriers of adaptation initiatives – how societal transformation affects natural hazard management and risk mitigation in Europe. Science of the Total Environment, 650, 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.08.306.

- Thaler, T., et al., 2023. Natural flood management: opportunities to implement nature-based solutions on privately owned land. WIREs Water, 10, e1637. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1637.

- Thaler, T., and Penning-Rowsell, E.C., 2023. Policy experimentation within flood risk management: transition pathways in Austria. The Geographical Journal, https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12528.

- Thaler, T., Priest, S.J., and Fuchs, S., 2016. Evolving inter-regional cooperation in flood risk management: distances and types of partnership approaches in Austria. Regional Environmental Change, 16, 841–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0796-z.

- Thaler, T., Seebauer, S., and Schindelegger, A., 2020. Patience, persistence and pre-signals: policy dynamics of planned relocation in Austria. Global Environmental Change, 63, 102122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102122.

- Weick, K.E., 1993. The collapse of sensemaking in organizations. The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 628–652. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393339.

- Wharton, G., and Gilvear, D.J., 2007. River restoration in the UK: meeting the dual needs of the European union water framework directive and flood defence? International Journal of River Basin Management, 5, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2007.9635314.

- Wiering, M.A., et al., 2017. Varieties of flood risk governance in Europe: How do countries respond to driving forces and what explains institutional change? Global Environmental Change, 44, 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2017.02.006.

- Wiering, M., Liefferink, D., and Crabbé, A., 2018. Stability and change in flood risk governance: on path dependencies and change agents. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 11, 230–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12295.