Abstract

Food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs) are not a new concept and are being used in many countries to promote healthy eating and the prevention of diet-related chronic diseases. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recommended FBDGs as an approach to prevent malnutrition and promote healthy dietary behaviours in populations, taking into consideration local conditions, traditional dietary practices and socioeconomic and cultural factors whilst at the same time using evidence-based scientific principles. South Africa (SA) currently has two sets of guidelines, namely the paediatric food-based dietary guidelines and the South African FBDGs for the population aged seven years and older. The recognition that elderly malnutrition remains a major public health concern in SA led to the formulation of a specific set of guidelines for this vulnerable population group based on existing nutrition-related health issues, local dietary habits and barriers to food intake experienced by those aged 60 and above. This introductory paper on the development of the elderly food-based dietary guidelines (EFBDGs) will be followed by six technical papers motivating why these guidelines are suited to address nutrition-related issues among the elderly in SA.

Introduction

The world is ageing; it is projected that between the years 2015 and 2050, the population of those aged 60 years and above will rise from 900 million to 2 billion (increase of 10%).Citation1 Southern African countries, such as SA, are actually an exception with a relatively small percentage of the population in the older age groups.Citation2 Currently, 8.2% of the South African population are over the age of 60 and 5.2% are over the age of 65. Although SA has a relatively small percentage of the population in the age range 60+ compared with higher income countries, by 2025 the total population aged over 60 is expected to be over 10.5%. In 2015, South African males 60 years of age had a life expectancy of 73½ years. Women of the same age had a life expectancy of 78 years.Citation3

Ageing is an inevitable, natural process associated with higher prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs contribute to 51% of deaths in SA.Citation4 Good food choices and optimal nutrition are important for the prevention and treatment of NCDs throughout the life span.Citation5 A whole-diet approach is essential for the prevention and treatment of frailty in the elderly as people do not eat single nutrients, but food and meals.Citation6 Furthermore, research has indicated the importance of adequate dietary intakes of energy, protein, clean water and micronutrients in the elderly and the impact thereof on NCDs and frailty. Malnutrition, both under- (for example, micronutrient deficiencies) and over-nutrition (for example, obesity), exacerbates the risk of immobility and frailty.Citation6 Eating difficulties, often observed in the elderly due to loose teeth, ill-fitting dentures, sensory changes, dry mouth and food–drug interactions, may also affect food choices and dietary intakes that can lead to malnutrition and dehydration. In addition, cultural food preferences and dietary intake habits and experiences throughout the lifetime impact on food choices and should be considered when planning interventions for the elderly.Citation7 An important goal during ageing is maintaining health and functional independence. Many of the health problems experienced during old age can be prevented or controlled by healthy lifestyle behaviours such as regular physical exercise and consuming a balanced, healthy diet.Citation8 The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) recommended food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs) as an approach to prevent malnutrition and promote healthy dietary behaviours in populations, taking into consideration local conditions, traditional dietary practices, and socioeconomic and cultural factors whilst at the same time using evidence-based scientific principles.Citation9 The current global COVID-19 pandemic is of huge public health concern and the majority of deaths are occurring in the elderly, specifically those suffering from two or more comorbidities.Citation10 Nutritional deficits are most prevalent in older populations, contributing to the weakening of the immune system and negatively impacting on antibody production, making the elderly susceptible to infections.Citation10 This paper aims to describe the process followed in developing FBDGs for the elderly (EFBDGs). The testing of the developed guidelines has been described in a previous paper by Napier and co-authors.Citation11

Background to food-based dietary guidelines

The International Conference on Nutrition (ICN) convened by the FAO in Rome in 1992 adopted ‘Promoting appropriate diets and healthy lifestyles’ as one of its plans of action. Governments were called upon to provide dietary guidelines to the public. The FAO and the World Health Organization (WHO) in an international consultation recommended the development and implementation of FBDGs by governmentsCitation9 and provided guidelines for the development of the guidelines.

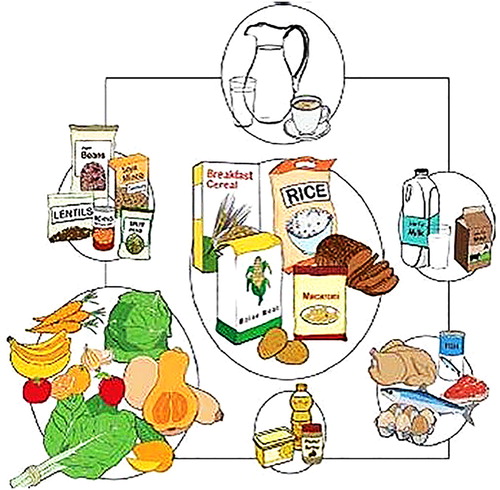

SA agreed to this strategy and the first set of South African FBDGs for South Africans older than five years was completed in 2000 and adopted by the Department of Health in 2003;Citation12 the paediatric food-based dietary guidelines (PFBDGs) were completed and published in 2007.Citation13 The SAFBDGs were further updated in 2012 for intended use by people seven years and older (refer ). Consequent to these FBDGs, the South African Food Guide was developed in 2012 and is illustrated in .Citation13

Figure 1: The South African Food Guide.Citation13

Table 1: First and revised food-based dietary guidelines for South AfricansCitation13

Characteristics of FBDGs

FBDGs are messages that can be used to guide consumers and educators on the best foods and drinks to consume to manage NCD risk.Citation14 Unlike other types of recommendations, FBDGs are framed in terms of the food being consumed and not individual nutrients, making the message easy for the consumer to conceptualise and understand.Citation12

FBDGs are intended to be used in health promotion, nutrition education and dietary guidance for the general public and therefore should be culturally sensitive and take into consideration appropriate customary dietary patterns for various population groups. These guidelines should further address public health concerns (such as those described above) in specific population groupsCitation14 such as the elderly. The key principles for developing food-based dietary guidelines include:

Dietary patterns:

Total diet and food patterns should be reflected rather than nutrients and numerical nutrient goals.

Practicality:

Recommended foods should be affordable, widely available and accessible and these guidelines should be flexible for use by various population and age groups.

Comprehensibility:

Levels of literacy must be considered when developing the guidelines, with good visual presentation, and testing of the guidelines is of importance.

Cultural acceptability:

Foods chosen and colours used in illustrations should be appropriate in terms of culture and religion. Appropriate language should be used with positive messages encouraging the enjoyment of appropriate diets.Citation9,Citation14

Food-based dietary guidelines for the elderly globally

There are several countries with developed FBDGs for the elderly as a tool to address old-age related health challenges. presents the guidelines developed by Australia,Citation15 New Zealand,Citation16 Singapore,Citation17 the United KingdomCitation18 and the United States of America.Citation19 These guidelines were consulted in the development of the EFBDGs.

Table 2: Elderly Food Based Dietary Guidelines (EFBDG) in various countries

Development of food-based dietary guidelines for the elderly in South Africa

Vorster et al.Citation12 recommended the development of FBDGs for vulnerable groups in SA. A working group was assembled in 2012 to develop FBDGs for elderly South Africans. The working group met in the same year to discuss their mandate and it was agreed to develop FBDGs for South African elderly aged 60 years and aboveCitation11 and to use the FAO/WHO consultation guidelines on the development of FBDGs and adapt it for local conditions.Citation14 The decision to develop separate EFBDGs to promote health for SA elderly was based on their specific dietary needs for healthy ageing and specific diet-related public health issues as highlighted earlier in this paper. The EFBDGs developed are based on the current SAFBDGs.Citation11 A recent global review of FBDGs from 90 countries, seven in Africa including SA, indicated that the SAFBDGs adhere to the WHO Healthy Diet Fact Sheet,Citation20 therefore it was prudent to base the EFBDGs on the SA guidelines. The Nutrition Society of South Africa (NSSA) then endorsed the development of the EFBDGs as a NSSA project.

The key objectives of the working group were to:

Find and expand on common dietary health issues based on the public health profiles of the elderly in SA.

Agree on the role of nutrients and dietary patterns in healthy ageing.

Develop appropriate guidelines based on the current SA FBDGs for South Africans seven years and older.

Test the consumer understanding and appropriateness of the guidelines in five of the official SA languages.

Write scientific papers for each guideline in support of its formulation, background and aims.

Develop support educational material for the guidelines for the layperson.

Develop support material for nutrition educators.Citation11

Members of the working group reviewed international and SA literature to identify public health problems related to nutrition in the elderly and to develop preliminary EFBDGs. Twelve guidelines were developed addressing the main elderly health and wellness concerns and these were closely aligned with the current SA FBDGs.Citation11

In May 2013 the literature reviews and preliminary guidelines were circulated to international and local expert advisers who previously agreed to assist with the review process, for input into the initial/draft motivations and guidelines with the literature reviews as support information. Once the feedback was received from the advisers the working group met again later in 2013 to discuss the feedback and reviewed the EFBDGs considering the input from the expert advisers. Consensus was reached, and the guidelines updated to 13 (see ).Citation11

Table 3: Preliminary and final food-based dietary guidelines for South African elderlyCitation11

The next stage of the development was to test the guidelines in a community setting. This consisted of two phases, with the first phase testing understanding of the English EFBDGs in the various age groups, and phase two testing understanding of the adapted and translated EFBDGs. The detailed development and testing process was published in the South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition in 2017Citation11 and a snapshot of the process is presented below.

Phase 1: testing of English guidelines and various SA language groups

A study population of IsiZulu, Afrikaans, IsiXhosa, English and Sesotho speaking elderly were selected to be included in the focus groups for testing of the English guidelines as these five languages are the most spoken languages in SA.Citation11 The aim of the focus groups, consisting of six to eight women and men in each language category, was to establish whether the guidelines were understood, interpreted correctly and culturally acceptable.

The study population included was made up of elderly individuals aged 60 years and older in Durban, Vereeniging, Pretoria, East London and rural Qwa-Qwa (KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng, Eastern Cape and Free State provinces, respectively).Citation11 From the testing it was evident that three guidelines were not clear and some members of the focus groups found them confusing. These were the guidelines on including legumes, meat, fish and chicken, and whole grains. The confusion, however, was related to the English words used.

Phase 2: translation of guidelines and testing of translated guidelines

Once the results of the first phase focus groups were analysed, the guidelines were again reviewed by the working group and adapted to address language barriers as well as unfamiliar words in the English guidelines. The EFBDGs were then translated into IsiZulu, Afrikaans, IsiXhosa and Sesotho. After translation the guidelines were again tested in focus groups to assess whether the participants understood the guidelines as translated into their home languages.Citation11 The final translated EFBDGs were understood and were accepted as presented in .

Public health concerns in the elderly to be addressed by the EFBDGs

Obesity

Obesity has become a global epidemic in recent years and is now responsible for 2.8 million deaths per year.Citation21 The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (SANHANES-1) indicated that the prevalence of obesity tended to increase with age in both men and women. Older adults usually are less active and thus need to reduce energy intake due to the decrease in basal metabolic rate (BMR). However, this does not always happen and thus body weight increases during old age due to an energy imbalance.Citation22 The proportion of obese women aged 55–64 and 65 years and older were 56.3% and 52.2% respectively in SA.Citation23 According to the South Africa Demographic and Health Survey (SADHS) 2016, the majority of men (54.4%) and women (75.4%) aged 65 years or above were either overweight or obese.Citation24 Moreover, a cohort study among the elderly in Sharpeville showed a consistent prevalence of overweight/obesity of more than 83.7% in women.Citation23 In addition, a study among elderly in Umlazi showed a prevalence of 82.0% overweight/obesity among women.Citation25 Obesity has the potential to increase risk of hypertension, coronary heart diseases (CHDs) and cancer.

Cardiovascular diseases

With increasing age, many older adults have dyslipidaemias, more so than in younger adults. In SA, 13.2% of older adults within the age range of 55–64 years, and 15.5% who were 65 years or above had high blood cholesterol.Citation5 However, in a smaller study conducted among women aged 18–90 years old in the Vaal region, the prevalence of dyslipidaemia was 34.3%.Citation26 In a cohort study among the elderly in Sharpeville, a consistently high prevalence of dyslipidaemia, specifically low high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol (HDL-C) (> 70%) and high triglyceride (> 34%) levels, was observed.Citation27

It has been proposed that pre-menopausal women have a lower risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) compared with men of the same age group, due to the protective effect of the female hormone oestrogen. After menopause, however, post-menopausal women become more prone to CVD, due to the reduced levels of oestrogen.Citation28

Hypertension

Several studies done in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) concluded that age is strongly associated with increased prevalence of hypertension, and the prevalence rate of hypertension in adults aged 50 and older was found to be significantly higher than in the rest of the adult population. The SADHS reported that the prevalence of hypertension in adults had doubled from 25% to 46% in women and 23% to 44% in men between 1998 and 2016. However, hypertension was more prevalent among older adults aged 65 and above (84%).Citation24 In a smaller study in SA, the hypertension prevalence among adults above 50 years old was also found to be very high (77%).Citation29,Citation30 Important to note is that many older adults are not aware that they have hypertension as only 38% were aware of their condition.Citation31

Diabetes mellitus

The prevalence of diabetes as reported by the SADHS (2016) was slightly higher in women (13%) than in men (8%). However, the survey found that 64% of women and 66% of men had prediabetes and were therefore at a greater risk for diabetes.Citation24 At present the global age-specific mortality rate for diabetes is the highest in Africa, but very little research has been done among the elderly in SSA.Citation28 Diabetes, especially type 2 diabetes (T2D), which is often a result of lifestyle behaviours, negatively influences the quality of life in older adults in SA. A study found that 9.2% of the older adults had diabetes in SA;Citation32 however, in a recent cohort study among the elderly in Sharpeville, consistently high serum glucose levels were observed in more than 30%.Citation27

Metabolic syndrome

The prevalence of high levels of diabetes, obesity, high cholesterol and low HDL-C in SACitation27 provides a combination of factors that could lead to a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome (MetS). Not much is documented concerning the prevalence rate of MetS in SA and only a few studies have reported MetS prevalence, ranging from an overall 30.2% in rural women (23) to 60.6% among coloured women in Cape Town. These rates indicate a high prevalence of MetS in SA, but limited information regarding the prevalence of MetS in the elderly exists for SA.Citation27

Malnutrition

Data from 12 countries, including SA, showed that nearly 14% of elderly individuals residing in nursing homes and nearly 6% of community-dwelling elderly individuals were malnourished.Citation33 Though the nationwide prevalence of malnutrition amongst the elderly population is currently unknown, SA’s growing elderly population and radically unequal quality of (health) care likely indicate that a sizeable portion of the older adult population faces malnutrition.Citation34,Citation35 Age-specific changes in protein intake, energy expenditure and micronutrient metabolism also play a role in the risk of malnutrition in the elderly.Citation36

Micronutrient deficiencies

Dietary diversity is a proxy indicator for micronutrient adequacy of the diet.Citation37 In fact, inadequate dietary diversity could cause micronutrient deficiencies.Citation22 Nutrient deficiencies not only impact adversely on physical and cognitive development but also contribute to decreased work productivity, increased risk of infection and various diseases as well as premature death.Citation38,Citation39 Several studies indicated that the most common nutrient deficiencies in SA included calcium, iron, zinc, iodine, riboflavin, niacin and folate as well as vitamins A, E, C and B6.Citation40–44 Interestingly, the national anaemia prevalence for elderly men (> 65 years) is the highest (25.9%) compared with the overall national prevalence of 17.5%. Elderly women had an anaemia prevalence of 17%.Citation20 Several studies among the elderly in Sharpeville, Umlazi and other areas in SA showed poor dietary intake of multiple micronutrients. Studies undertaken among the Sharpeville elderly indicated iron-deficiency anaemia, folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies, suboptimum vitamin A and E status and a high prevalence (76.3%) of zinc deficiency, with women having higher prevalence rates than men.Citation27,Citation45,Citation46

Other common problems experienced in the elderly

Gastrointestinal problems

Ageing affects the motor and sensory functions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract resulting in the elderly having a higher susceptibility to GI complications of co-morbid illnesses.Citation47 Specific age-related GI changes affect the oesophagus and colon specifically. These include reduced peristaltic pressure in the oesophagus leading to dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux and reduction in colon motility causing constipation.Citation47 GI problems, such as diarrhoea and constipation, are common among the elderly. Rates of almost 50% for the elderly older than 55 years and 70% for those in nursing homes have been reported. Constipation is mainly caused by medication use, certain diseases such as diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome, blunted thirst mechanisms that may result in too low fluid intakes, less responsive intestinal muscle movement, declining cognitive function that may result in the elderly not recognising the urge to defecate, and low-fibre diets due to chewing problems.Citation48 The GI tract has an important role in maintaining homeostasis of many physiological processes such as ensuring adequate digestion and absorption of nutrients.Citation49 A healthy and well-functioning GI tract is associated with life satisfaction whereas diseases of the digestive system have been associated with a higher symptom burden that negatively affects the general health of elderly people. Furthermore, research has found a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression among those elderly who have GI symptoms.Citation50

Cognitive impairments

T2D and MetS are major risk conditions for cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease due to disturbances in insulin signalling that can impair glucose delivery and use by the brain and nerve cells, leading to decreased function. This can result in structural changes in the memory of the hippocampus, leading to cognitive dysfunction and memory impairment. However, research has found hypometabolism of glucose in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease and dementia. Although human studies are limited, a daily diet that includes an optimal balance of whole grain and other macro- and micronutrients, specifically the B-vitamins, is associated with lower risk of cognitive impairments, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease.Citation51

Dementia and depression

Dementia has become a significant economic burden in SSA but, because it is perceived as a normal part of growing old, many people are left undiagnosed. Furthermore, limited research has been undertaken among the elderly with dementia, resulting in a paucity of information.Citation19 However, in a systematic review exploring dementia and cognitive impairment in the elderly in SSA, higher dementia prevalence was observed in women (60–69 years) and men older than 70 years.Citation52 Underweight, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and hypertension are associated with dementia.Citation30 A number of studies conducted in specific areas in SA highlighted the poor nutrition and health status of older adults.Citation11,Citation53 For example, a study with 422 older adults aged 50 years and above showed that 42% of them suffered from depression.Citation53

Osteoporosis

Bone health is a common health issue during ageing, especially for women.Citation54 Elderly people are more vulnerable compared with other-aged population groups in terms of osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is a bone health problem characterised by low bone mass and micro-architectural deterioration, and increases the risk of bone fragility and fracture.Citation55 There are many risk factors, which include both irreversible and modifiable factors, that contribute to low bone density. The risk of osteoporosis has a positive association with increased age, family history, female gender, oestrogen deficiency, amenorrhea, vitamin D deficiency, low intakes of calcium, chronic diseases, leading a sedentary lifestyle, and excessive smoking and alcohol consumption. Among the many factors that affect bone health and healthy ageing, healthy lifestyle behaviours (dietary intake and physical activity) are recognised as modifying factors to improve bone health in the elderly. Calcium intake is low among the elderly in SA.Citation31

The incidence of osteoporosis is more common among white, Asian and mixed-race populations compared with the black populations.Citation56

The way forward

Technical support papers, based on recent and relevant scientific literature, were developed for each of the guidelines underpinning the science behind the guidelines selected and will be published in additional papers. Additional support material targeting the elderly is currently being developed and will address the needs of this group in the five languages. The following factors for the development of effective nutrition education messages will include:

− household food security (the availability, accessibility and affordability of food);

− nutrition-related public health concerns;

− the consumer’s socioeconomic circumstances;

− the consumer’s lifestyle and cultural eating habits;

− the consumer’s understanding of and ability to apply the information, which will be considered during the development process.Citation57,Citation58

The next step will then be for the SA Department of Health to adopt these guidelines and to roll out the support material, which is being designed for the lay public as well as health professionals.

Conclusion

As age increases in the elderly, so does the risk of illness and malnutrition and in turn the prevalence of morbidity.Citation7 Nyberg et al.Citation7 further explains that appetite, smell, taste and eyesight deteriorate with age and are among the risk factors for poor dietary intake, nutritional status and specific drug use in the elderly. Preparing food for oneself is a sign of independence and is strongly associated with well-being and increased self-esteem. Community members need to be empowered and educated in ways to achieve an affordable yet balanced diet given their limited resources, mobility and knowledge. The EFBDGs will be a tool that can be used by healthcare workers to educate and empower the elderly regarding healthy food choices and lifestyle behaviours to prevent disease and improve health.

Author contributions

All authors assiduously contributed to the preparation of this manuscript and gave their respective approvals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- World Health Organization. 10 facts on ageing and health. 2017 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/ageing/en/

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2017 – Highlights. 2017 [cited 2021 May 24] Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2017_Highlights.pdf

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population facts: Sub-Saharan Africa’s growing population of older persons. 2016 [cited on 2018 April 18].

- World Health Organization. Non-communicable diseases country profiles; 2018 [cited 2019 Jun 15]. Available from: https://www.who.int/nmh/countries/zaf_en.pdf?ua=1

- Montagnese C, Santarpia L, Buonifacio M, et al. European food-based dietary guidelines: a comparison and update. Nutrition. 2015;31:908–15.

- Goisser S, Guyinnet S, Volkert D. The role of nutrition in frailty: an overview. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(2):74–7.

- Nyberg M, Olsson V, Pajalic Z, et al. Eating difficulties, nutrition, meal preferences and experiences among elderly, a literature overview from a Scandinavian context. J Food Res. 2014;4(1):22–37.

- Boyle MA. Community nutrition in action: an entrepreneurial approach. 7th ed. Boston (MA): Cengage Learning; 2017.

- Clay WD. Preparation and use of food-based dietary guidelines. FAO information division; 1997.

- Bencivenga L, Rengo G, Varricchi G. Elderly at time of Corona Virus disease 2019 (COVID-19): possible role of immunosenescence and malnutrition. GeroScience. 2020;42:1089–92.

- Napier CE, Oldewage-Theron WH, Grobbelaar HH. Testing of developed Food Based Dietary Guidelines for the elderly in South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2017;1(1):1–7.

- Vorster HH, Love P, Brown C. Development of food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa – the process. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2001;14(3):S3–S6.

- Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2013;26(3):S5–S12.

- FAO/WHO Consultation. Preparation and use of food-based dietary guidelines. Nutrition Programme WHO/NUT 96.6. Geneva: WHO; 1996, p. 1–9.

- Australian Government Department of Health. Healthy eating when you’re older: eat for health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/eating-well/healthy-eating-throughout-all-life/healthy-eating-when-you’re-older

- Ministry of Health. Food and nutrition guidelines for healthy older people. A background paper [Internet]. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2013. Available from: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/food-nutritionguidelines-healthy-older-people-background-paper-v2.pdf

- Ministry of Health Singapore. Dietary guidelines for elderly [Internet]. HealthHub. 2019 [cited 2019 Jan 14]. Available from: https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/456/Dietary Guidelines for Older Adults

- UK Government. Healthy eating for older adults [Internet]. NIDirect Government services. 2018 [cited 2019 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.nidirect.gov.uk/articles/healthy-eating-older-adults#toc-9

- USDA. 2015 dietary guidelines for Americans – my plate for older adults [Internet]. Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. 2015 [cited 2019 Jan 14]. Available from: https://hnrca.tufts.edu/myplate/tips-extra-info/2015-dietary-guidelines-for-americans/

- Herforth A, Arimond M, Alvarez-Sanchez C, et al. A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:590–605.

- Brewer D, Dickens E, Humphrey A, et al. Increased fruit and vegetable intake among older adults participating in Kentucky’s congregate meal site program. Edu Gerontol. 2016;42(11):771–84.

- Shisana O, Labadarios D, Rehle T, et al. The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2012: SANHANES-1: the health and nutritional status of the nation. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2013. c2019. Available from http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-outputs/view/6493

- Oldewage-Theron W, Kruger L. Food variety and dietary diversity as indicators of the dietary adequacy and health status of an elderly population in Sharpeville, South Africa. J Nutr Elder. 2008;27(1-2):101–33. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/01639360802060140

- National Department of Health (NDoH), Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) and ICF. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016: key indicators.

- Mkhize X, Napier C, Oldewage-Theron W. The nutrition situation of free-living elderly in Umlazi township, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid. 2013;18(1):1–8. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v18i1.656

- Oldewage-Theron WH, Egal AA. Prevalence of and contributing factors to dyslipidaemia in low-income women aged 18-90 years in the peri-urban Vaal region. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2013;26(1):23–9.

- Oldewage-Theron WH, Egal AA, Grobler C. Metabolic syndrome of free-living elderly from Sharpeville, South Africa: a prospect cohort study with 10-year follow up. J Ageing Res Clin Practice. 2018;7:100–6.

- Yang XP, Reckelhoff JF. Estrogen, hormonal replacement therapy and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20(2):133–8.

- Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Depression and associated factors in older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1):18871.

- Lloyd-Sherlock P, Beard J, Minicuci N, et al. Hypertension among older adults in low-and middle-income countries: prevalence, awareness and control. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):116–28.

- Audain K, Carr M, Dikmen D, et al. Exploring the health status of older persons in Sub-Saharan Africa. Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;76(4):574–9.

- Peltzer K, Phaswana-Mafuya N. Fruit and vegetable intake and associated factors in older adults in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2012;5(1):18668.

- Robb L, Walsh CM, Nel M, et al. Malnutrition in the elderly residing in long-term care facilities: a cross-sectional survey using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA®) screening tool. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2017;30(2):34–40. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/16070658.2016.1248062

- Statistics South Africa. Census 2011: profile of older persons in South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 2014. 137 p. Report No.: 03-01-60.

- Gaspareto N, Previdelli AN, Aquino R. Factors associated with protein consumption in elderly. Rev Nutri. 2017;30(6):805–16. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1590/1678-98652017000600012

- Boire Y, Morio B, Caumon E, et al. Nutrition and protein energy homeostasis in elderly. Mech Ageing Dev. 2014;136-137:76–84. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2014.01.008

- Steyn NP, Nel JH, Nantel G, et al. Food variety and dietary diversity scores in children: are they good indicators of dietary adequacy? Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(5):644–50. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1079/PHN2005912

- World Health Organization. Micronutrient deficiencies. [Homepage on the Internet]. 2019. Available from https://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/ida/en/

- Shenkin A. Micronutrients in health and disease. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(971):559–67. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.047670

- Directorate of Nutrition, Department of Health. Executive summary of the National Food Consumption Survey Fortification Baseline (NFCS-FB-I) South Africa [homepage on the Internet]. 2015. Available from http://www.sajcn.co.za/index.php/SAJCN/article/view/286/281

- Ingram CF, Fleming AF, Patel M, et al. Pregnancy- and lactation-related folate deficiency in South Africa: a case for folate food fortification. S Afr Med J. 1999;89(12):1279–84.

- Ubbink JB, Christianson A, Bester MJ, et al. Folate status, homocysteine metabolism and methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase genotype in rural South African blacks with a history of pregnancy complicated by neural tube defects. Metabolism. 1999;48(2):269–74. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1016/S0026-0495(99)90046-X

- Steyn NP, Wolmarans P, Nel JH, et al. National fortification of staple foods can make a significant contribution to micronutrient intake of South African adults. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(3):307–13. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1017/S136898000700033X

- Labadarios D, Steyn N, Maunder E, et al. The National Food Consumption Survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(5):533–43.

- Oldewage-Theron WH, Samuel FO, Djoulde RD. Serum concentration and dietary intakes of vitamins A and E in low-income South African elderly. Clin Nutr. 2010;29(1):119–23. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2009.08.001

- Oldewage-Theron WH, Samuel FO, Venter CS. Zinc deficiency among the elderly attending a care centre in Sharpeville, South Africa. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2008;21(6):566–74. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2008.00914.x

- Clements SJ, Carding SR. Diet, the intestinal microbiota, and immune health in aging. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58(4):651–61. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2016.1211086

- Sayhoun NR. Nutrition and older adults. In: Brown J, editor. Nutrition through the life cycle. 6th ed. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2016. p. 449–510.

- An R, Wilms E, Masclee AAM, et al. Age-dependent changes in GI physiology and microbiota: time to reconsider? Gut. 2018;67:2213–22. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315542

- Ganda Mall JP, Löfvendahl L, Lindqvist CM, et al. Differential effects of dietary fibres on colonic barrier function in elderly individuals with gastrointestinal symptoms. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13404. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31492-5

- Jones JM, Korczak R, Pena RJ, et al. Carbohydrates and vitamins from grains and their relationship to mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease. Cereal Foods World. 2017;62(2):65–75.

- Mavrodaris A, Powell J, Thorogood M. Prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment among older people in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:773–83.

- Nyirenda M, Chatterji S, Rochat T, et al. Prevalence and correlates of depression among HIV-infected and -affected older people in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):31–8.

- Plawecki K, Chapman-Novakofski K. Bone health nutrition issues in aging. Nutrients. 2010;2(11):1086–105.

- Prentice A. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of osteoporosis. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(1a):227–43.

- International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF). South Africa. 2018. Available from: https://www.iofbonehealth.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/Audit%20Middle%20East_Africa/ME_Audit-South_Africa.pdf

- Gibney MJ, Wolever TMS. Periodicity of eating and human health: present perspective and future directions. Br J Nutr. 1997;77:S3–S5.

- Gillespie S. Development of a framework and identification of indicators for evaluation. Food Nutr Bull. 1990;12(2):1–4.