ABSTRACT

Background

Blood transfusion is essential in the treatment of a wide range of illnesses. There are two sorts of donors in the blood donation system voluntary and replacement donors.

Objectives

In this study, we examined Saudi adults’ knowledge, beliefs, and associated factors towards blood donation in Saudi Arabia.

Methods

A cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted over three months between November 2019 & January 2020 among the general public, using structured self-administered 18-items online questionnaires. A descriptive analysis was performed, a chi-square test was conducted to determine the relationships between the variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

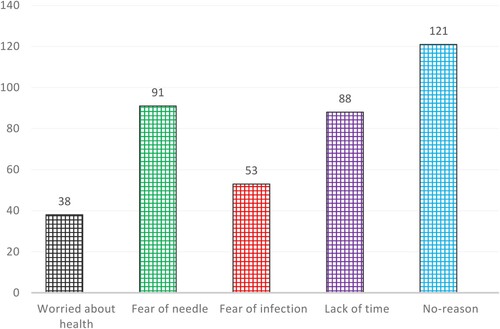

A total of 364 respondents (93.1%) believed that blood donation is an important responsibility of every individual. When asked about the reason for previous donations 261(66.8%) said voluntary while approximately 130 (33.2%) donated for their families and friends. Fear of needles 91 (23.3%), fear of infection 53 (13.6%) a lack of time 88 (22.5%) were common barriers, and 270 (69.1%) agreed that token gifts should be given to donors. In this study, 71.1% (n = 278) were found to have good knowledge, and 96.7% (n = 378) found positive beliefs towards blood donation. The knowledge is significantly associated with being a male gender (p < 0.049), and the educational level of the participants (p < 0.003). positive beliefs were significantly associated with young donors (p < 0.045)

Conclusion

These outcomes indicate that the Saudi public has positive beliefs and acceptable knowledge about blood donation and its importance in the society and health care system. Furthermore, educational programs should be done to increase the level of awareness about blood donation and its significance.

1. Background

Blood is the most essential component of the human body and is important for every activity and regarded as the gift of life [Citation1]. Evidence indicates that there is no substitute for blood, furthermore, scientific reports have revealed that every 3 seconds a blood transfusion is required [Citation1]. Blood transfusion saves someone from premature mortality; however, obtaining blood at the right time is challenging these days [Citation1,Citation2]. A supply of safe blood can be obtained through voluntary unpaid donors, as they are considered healthy individuals and the risk of transmission of infection is less than in paid donors [Citation2–4]. Preliminary studies have reported that the demand for safe blood is increasing in day-to-day life, due to the increased number of chronic diseases related to blood, which includes a variety of surgical procedures, unexpected accidents, pregnancy-related complications, and anemia [Citation5,Citation6].

The estimated global prevalence of blood donation is 112.5 million units and high-income countries are reported to have 50% of all donations compared to lower-income countries [Citation7,Citation8]. Shea and Giles [Citation9] reported that blood donation helps to burn approximately 650 calories per donation, while Kamhieh-Milz et al. in 2016 [Citation10] reported that blood donation also helps in controlling blood pressure. Earlier studies showed that in developed countries voluntary blood donation is the only option [Citation11,Citation12]. In Saudi Arabia evidence suggests that the prevalence of blood donation is 45.8–53.3% [Citation5]. Blood donation is more common in males than in females [Citation13,Citation14]. Previous findings from Saudi Arabia revealed that people have different fears about accepting blood from strangers or donors, and that half of the Saudis surveyed believe blood donation is risky, and that the majority of the Saudis never know whether blood banks require blood or not, implying that a large number of people in Saudi Arabia have a negative perception of blood donation and its importance [Citation15,Citation16]. Previous studies have revealed that donor education is limited in Saudi Arabia and it completely depends on replacement donors which constitute 60% of volunteers in Saudi Arabia [Citation17]. Sufficient knowledge of blood donation is estimated to be 60% in developing countries. However, studies have also revealed that blood donation rates vary depending on country status [Citation3,Citation4]. The rate of blood donation is far less in low-income countries than that in middle- and high-income countries [Citation3,Citation4]. To maintain an adequate safe blood supply at both a national and international level it is essential to understand public opinion and barriers to donation so that health organizations and government bodies know how to achieve an adequate blood supply.

Al-Drees in 2008 [Citation15] conducted a study to assess Saudi public beliefs towards blood donation, reported different fears of blood donation and transfusion among the surveyed participants (n = 335) 20% of them refused blood transfusion even if they were in need because of the risk of acquiring an infectious disease, while 49% of them stated that they would accept blood donation only from relatives, about 11.6% claimed to have acquired infectious disease after blood transfusion. Similarly, Abolfotouh et al. [Citation16] reported higher misconceptions, poor knowledge, and unfavorable attitude to donation. There were studies published to assess the knowledge, attitude, and practice of blood donation among health professionals and students in Saudi Arabia [Citation5,Citation13,Citation18], but there is no evidence of studies among the general public to assess the beliefs, knowledge, and opinions of blood donation in the Saudi community. In addition availability of blood donors to supply blood on time is another significant challenge. The research focused on knowledge, beliefs towards blood donation can provide an overall picture of blood donors towards blood donation. Therefore, it is necessary to design and implement research activities in this area. In this study, we examined Saudi adults’ knowledge, beliefs, and associated factors towards blood donation in Saudi Arabia. The findings from this study could help indivduals to comeforward for donating blood, without any hesitation also the findings may helps public health planners and other health sector authorities to promote blood donation effectively.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design, setting, and participants

A cross-sectional web-based survey was conducted over three months between November 2019 & January 2020 among the general public residing in the capital of Saudi Arabia, using structured self-administered online questionnaires. The target population for this study was residents of Riyadh capital of Saudi Arabia, aged 18 years and over. The estimation of the sample size was done by Morgan’s Table [Citation19]. As this was an opinion-based study, we considered the total population size of 10,000, and at 95% CI with a 5% margin of error, the calculated sample size using Morgan’s Table was 384. However, the study received responses from 391 participants.

2.2. Data collection and variables

The survey questionnaire was prepared after an extensive literature review [Citation16,Citation19,Citation20]. An initial draft of a questionnaire was designed in the English language, then translated into Arabic using a forward–backward translation procedure with the help of a certified translator. The questionnaire for this study was composed of three parts with a total of 17-items. The first part of the survey collected the demographics of the respondents with a total of 5-items (gender, age, educational level, marital status, employment status), while the second part asked respondents about their beliefs about blood donation, where three questions were answered with a binary scale (Yes/No). The third part of the survey consisted of knowledge of, blood donation, (how often a healthy person can donate, had you donated blood in the last six months, the acceptance of blood from others) and comprised a total of 6- items with multiple choice and binary answers. The last part of the survey dealt with motivation and consisted of two items, measuring participants’ motivational factors on a three-point scale (agree/disagree /I don’t know). Additionally, there was one item asking participants barriers to blood donation with multiple choice answers. Before using the questionnaire the study instrument was subjected to face and content validity testing by two senior selected faculty members from the pharmacy college of King Saud University to assess its clarity, significance, and acceptability. Modifications and refinements were made as per the comments received to enable a better understanding and to organize the sequence of questions. Survey reliability was tested by a pilot study with ten randomly selected participants. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.73 which indicated that the survey could be used in this study.

The final questionnaire was circulated through social media platforms. Data collection was conducted to reach the required sample size. An invitation was issued using social media (WhatsApp®, Twitter®) and on the most commonly visited internet websites by Saudi citizens to solicit participation in this study. For this purpose, we first targeted our professional and personal networks and informed them about the importance of the study through personal messages on WhatsApp. We encouraged them to complete and forward the study questionnaires to their circle (personal and social). We used a snowball procedure to reach the required sample size for this study. A total of 391 participants were recruited.

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) ethical committee of the college of medicine at King Saud University Riyadh Saudi Arabia with reference number 20/0202/IRB. This study followed the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) [Citation21]. The questionnaires contained a statement about the objective of the research and its importance, also a statement about participation in the research assuring participants that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any point in time. Participants were also informed that their data would only be used for research purposes and kept confidential. They were also assured that there was no risk associated with participation in this study. Participants’ informed consent was obtained before answering survey questions and they were requested to provide authentic answers. For the beliefs questionnaires, the beliefs score is calculated by assigning a score of 1 for accurate answers and a score of 0 for incorrect answers. In the same way, the knowledge score is calculated. We separated beliefs into two groups: positive beliefs with a score of more than 2 out of 3 and negative beliefs with a score of less than 1 out of 3. Similarly, the knowledge score is separated into two categories: Good knowledge, which received a score of more than 4 out of 6, and Poor knowledge, which received a score of less than 4 out of 6.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data received from the completed forms were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and exported to SPSS version 24.0 for statistical analysis. The results of these analyses are presented in terms of frequencies and percentages. A descriptive analysis was performed, chi-square or Fisher exact test was conducted to determine the relationships between the variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Participants characteristics

A total of 427 participants approached the web-based survey, 391 participants gave their consent to voluntary participation and completed the questionnaire with a response rate of 91.5%. Most participants were male 369 (94.4%), aged between 18–29 years 188 (48.1%), while 117 (29.9%) were between 30–39 years old. Slightly more than half 206 (52.7) % were married while 179 (45.8%) were single. Although the majority 335 (85.7%) had received higher education, only 56 (14.3%) were from below secondary school. The detailed demographic information is presented in .

Table 1. Demographics of the participants (N = 391).

3.2. Participants beliefs towards blood donation

Almost all of the respondents 364 (93.1%) believed that blood donation was an important responsibility of every individual in the community. All of the participants believed that 391 (100%) of blood donations helped others while about 258 (66%) believed that blood donation was a religious duty and 133 (34%) of the participants disagreed with it (). Only 13 (3.3%) of the participants had unfavorable beliefs about blood donation, even though 96.7% (n = 378) of the participants had positive beliefs. Positive views were shown to be significantly related to young donors (p = 0.045). There was no significant relationship between participant’s beliefs about blood donation and employment (p > 0.005), education (p > 0.005), gender (p > 0.005), marital status (p > 0.005). (see ).

Table 2. Participant’s beliefs about blood donation.

Table 3. Association between beliefs, participants’ demographics characters.

3.3. Participants knowledge towards blood donation

When asked about how often a healthy person could donate, 133 (34%) participants agreed that a healthy person could donate once in a year, while 95 (24.3%) said twice a year and 83 (21.2%) said three times a year. Only 27 (6.9%) of them agreed that a healthy person could donate five times a year. The majority of participants had donated blood previously as a volunteer 261 (66.8%) while approximately 130 (33.2%) had donated for their families and friends. Also, the majority had agreed to donate blood at a blood bank 239 (61.1%). Interestingly, in the past 6 months, 322 (82.4%) participants had never refused to donate blood and 343 (87.7%) said they would accept blood from other people. A small percentage of Saudis disagreed with the acceptance of blood from others. Further information about participants’ knowledge and attitudes to blood donation is presented in . A total of 71.1% (n = 278) of the surveyed donors were found to have good knowledge, while 28.6% (n = 112) were reported poor knowledge of blood donation. The knowledge is significantly associated with being a male gender (p = 0.049), and the educational level of the participants (P = 0.003). Furthermore, a detailed explanation of the association between knowledge levels and demographics of the participants was given in .

Table 4. Knowledge towards, blood donation.

Table 5. Association between Knowledge of, participants’ and demographics characters.

3.4. Barriers and motivational factors towards blood donation

The most common barriers to donating blood were fear of the needle 91 (23.3%), fear of infection 53 (13.6%), a lack of time 88(22.5%), and no specific reason 121 (30.9%) (). When we asked participants about motivating factors for donating blood 124 (31.7%) agreed that money should be paid to donors, while 270 (69.1%) participants agreed that gifts should be offered to donors ().

Table 6. Motivational factors for donating blood (n = 391).

4. Discussion

Worldwide the need for a supply of safe blood has become a difficult task these days due to the increasing number of blood disorders. However, the general community is willing to donate blood, but still, voluntary blood donation is lacking and the WHO has issued tight procedures for all countries collecting blood from individual donors. This study was conducted in Saudi Arabia to assess the Saudis beliefs and opinions about blood donation. Positive beliefs about blood donation were overwhelming, with 93.1% believing that blood donation is an important duty of every individual in the community and agreeing that blood donation helps needy patients. These results were similar to a previous study by Abdel Gader et al. that revealed that almost all participants had positive attitudes and beliefs about blood donation [Citation22]. This positivity toward blood donation might be due to the soft nature of Saudis which values helping others and even saving the lives of strangers. This comes from Islamic culture where some scholars have advised that a Muslim has to donate blood to save another’s life [Citation22,Citation23].

In this study, the most common barriers to donating blood were fear of the needle, fear of infection, a lack of time, and no specific reason. Similar findings were reported by Giri and Phalke [Citation24] who stated that non-consideration, forgetfulness, and a lack of time were the most cited barriers. However, another similar study of the Jordanian population reported that barriers included not receiving blood when needed, the side effects of receiving blood or blood components, having health problems, fear of blood, medical errors, time restraints, lack of required conditions to donate, and the fear of blood-borne infections such as HIV [Citation23]. The reported barriers among the north Indian community studied by Dubey et al. included never getting an opportunity to donate, and their belief that it could be harmful to their health [Citation25]. Alfouzan’s 2014 study of Saudi adults revealed that the most important barriers were blood donation had not crossed their mind, or they had no time for donation, or difficulty accessing a blood donation center [Citation5]. Enawgaw et al. in 2019 evaluated the knowledge and attitudes toward blood donation among the Ethiopian population and reported that fear of pain, medical unfitness to donate, and a lack of information on when, where, and how to donate blood were mentioned as reasons for not donating blood [Citation26]. Some other studies stated that a small number of respondents believed that blood donation was harmful to donors [Citation6,Citation24,Citation27,Citation28]. Similarly, two more studies reported that health concerns, feeling unwell, distance to the blood bank, fear of needles, pain, fear of complications, fear of hospitals, lack of awareness, false beliefs, and religious traditions were common barriers among participants [Citation29,Citation30]. These results provided evidence that a lack of awareness was a problem that prevented the public from donating blood. This could be solved by advertising blood donation health benefits and by disseminating adequate knowledge and awareness of blood donation to eradicate misbeliefs about blood donation. Keeping this topic in the mind of the community is essential.

Several studies have highlighted different motivations for blood donation [Citation5,Citation22,Citation30–32]. The current study revealed that 31.7% of the participants cited money as a motivating factor, while 69.1% agreed that a token gift should be given to donors in return gift for blood donation. These findings were higher than similar findings by Alfouzan in 2014 and Abdel Gader et al. in 2011 [Citation5,Citation22] who reported that money (18.9%), token gifts (31.5%), and the return of blood donation were motivating factors. However, Abdel Gader et al reported that 25% of participants wanted to receive money while 63% agreed to token gifts [Citation22]. However, in the current study, approximately 65% of participants rejected money as an incentive. Meanwhile, an earlier study by Okpara of Nigerians reported that 80% of respondents were prepared to donate freely [Citation33]. Similar results were reported by Bangladesh university students where 93% of participants were opposed to financial incentives [Citation34]. Although earlier research revealed that motivating individuals financially increased the chances of donation, there was a potential risk of attracting infected donors with a need for money rather than offering a safe donation [Citation22].

In this study, 71.1% of Saudi adults found good knowledge, which is similar to a previous study by Alsalmi et al, who reported 60.2% of the participants were knowledgeable [Citation18]. Although a recent study by Samreen et al reported a lower level of knowledge (41.9%) among the general public [Citation20]. The knowledge of the individuals might be different, concerning the design of the study, participants, and the methodology of the study. In this study, 34% of participants agreed that a healthy person could donate blood once a year, while approximately 25% of them said twice a year, 21.2% three times a year, and only 6.9% of them agreed that a healthy person could donate five times a year. An earlier study by Shamebo et al. [Citation35] reported that 47.7% of participants stated that the minimum donation frequency was every three months, 70 (20.2%) every six months, [Citation11] (3.2%) annually, with the remaining 61 (17.6%) not aware of this issue. Another similar study by Abdel Gader et al reported that 34% would donate six times a year, 22%: four times, 21%: three times, 14% twice, and 4% once a year [Citation22]. An earlier report published by the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia revealed that a healthy person could donate once every three months and not more than five times a year [Citation36]. The current study found that participants believed that the frequency of blood donation should be lower than reports published by the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia [Citation36]. This indicated that better knowledge of blood donation was required among our participants. Similar to previous studies, about 65% of the participants believed that blood donation is a religious duty [Citation5,Citation23,Citation36–38]. The majority of them agreed that blood donation helps needy individuals also most of the participants had positive opinions about blood donation. However, creating awareness in society and resolving misconceptions of blood donation could help to ensure the availability of blood when needed. However, this study had certain limitations. Firstly the nature of the sample size, which was limited to small. Furthermore, the findings relied on the self-completion of a questionnaire, which may generate false answers and a possibility of bias. Moreover, the findings are not generalizable to the international level as the findings were derived from a small group and, thus, non-representative. Given these limitations, the study suggests that future research should employ a larger sample size with a greater focus on the opinions, attitudes, and motivations as well as barriers toward blood donation.

5. Conclusion

These outcomes indicate that the Saudi public has positive beliefs and acceptable knowledge about blood donation and its importance in the society and health care system. Furthermore need for additional educational and awareness programs specific to blood donation in the Saudi community are needed. In addition, the study suggests that increased knowledge of blood donation through education and campaigns may encourage and motivate the general community and subsequently establish a sufficient supply of viable blood based on voluntarism, which is essential for healthcare.

Author contributions

WS, AS, MBR, NS conceived of this study and its design. WS, AS, MBR, NS conducted the data collection. WS, AS, MBR, NS reviewed and edited NS performed the screening process. WS, AS, MBR, NS performed the content analysis and coding. WS, AS, MBR, NS were involved in interpreting the results. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the research ethics committee college of medicine king Saud university Riyadh Saudi Arabia with the following Approval of Research Project No. E-20-4651.

Paper context

The most fundamental component of the human body, blood is required for all activities and is recognized as the gift of life. There is an increasing demand for safe and appropriate blood supplies promptly throughout the world.

Acknowledgement

The authors of this study extend their appreciation to the Researcher Supporting Project (RSP-2021/378), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for supporting and funding this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Action Plan for blood safety. Government of India, New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2007. Available from http://www.naco.gov.in/sites/default/files/An%20Action%20Plan%20for%20blood%20safety_2.pdf.

- Beyene GA. Voluntary blood donation knowledge, attitudes, and practices in central Ethiopia. Int J Gen Med. 2020;13:67–76.

- Gibbs WN, Corcoran P. Blood safety in developing countries. Vox Sang. 1994;67(4):377–381.

- Dhingra N, Lloyd SE, Fordham J, et al. Challenges in global blood safety. World Hosp Health Serv. 2003;40(1):45–49.

- Alfouzan N. Knowledge, attitudes, and motivations towards blood donation among King Abdulaziz medical city population. Int J Family Med. 2014;2014:539670.

- Javadzadeh Shahshahani H, Yavari M, Attar M, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice study about blood donation in the urban population of Yazd, Iran, 2004. Transfus Med. 2006;16(6):403–409. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2006.00699.x.

- World Health Organization. Blood safety and availability 2017. Available online http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets /detail/blood-safety-and-availability. Accessed on 21 February 2020.

- World Health Organization. Global Consultation: 100% Voluntary Non–Remunerated Donation of Blood and Blood Components. Melbourne, Australia; 2009. Available online https://www.who.int/ bloodsafety/ReportGlobalConsultation2009onVNRBD.pdf?ua=1. (Accessed on Day Month Year).

- Shea S, Giles S. Holiday reading: an intercultural and semi-confessional reflection on blood donation. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):2008–2009. doi:10.1503/cmaj.101448.

- Kamhieh-Milz S, Kamhieh-Milz J, Tauchmann Y, et al. Regular blood donation may help in the management of hypertension: an observational study on 292 blood donors. Transfusion. 2016;56(3):637–644.

- Directorate General for Communication. Blood donation and blood transfusions. Brussels: European Commission, Special Eurobarometer 333b; 2009.

- Mascaretti L, James V, Barbara J, et al. Comparative analysis of national regulations concerning blood safety across Europe. Transfus Med. 2004;14:105–111.

- Abolfotouh MA, Al-Assiri MH, Al-Omani M, et al. Public awareness of blood donation in Central Saudi Arabia. Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:401.

- Uma S, Arun R, Arumugam P. The knowledge, attitude and practice towards blood donation among voluntary blood donors in Chennai, India. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR. 2013;7(6):1043.

- Al-Drees AM. Attitude, belief and knowledge about blood donation and transfusion in Saudi population. Pak J Med Sci. 2008 Jan 1;24(1):74.

- Abolfotouh MA, Al-Assiri MH, Al-Omani M, et al. Public awareness of blood donation in Central Saudi Arabia. Int J Gen Med. 2014;7:401.

- ARAB NEWS. Efforts on to change attitude toward blood donation in Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.arabnews.com/node/1718146/saudi-arabia. (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Alsalmi MA, Almalki HM, Alghamdi AA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practice of blood donation among health professions students in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(7):2322.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30(3):607–610.

- Samreen S, Sales I, Bawazeer G, et al. Assessment of beliefs, behaviors, and opinions about blood donation in Telangana, India-A cross sectional community-based study. Front Public Health. 2021 Dec 9;9:785568. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.785568. PMID: 34957036; PMCID: PMC8695873.

- Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting re-sults of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi:10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34.

- Abdel Gader AG, Osman AM, Al Gahtani FH, et al. Attitude to blood donation in Saudi Arabia. Asian J Transfus Sci. 2011;5(2):121–126. doi:10.4103/0973-6247.83235.

- Abderrahman BH, Saleh MY. Investigating knowledge and attitudes of blood donors and barriers concerning blood donation in Jordan. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014;116:2146–2154.

- Giri PA, Phalke DB. Knowledge and attitude about blood donation amongst undergraduate students of Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences Deemed University of Central India. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2012;5(6):569.

- Dubey A, Sonker A, Chaurasia R, et al. Knowledge, attitude and beliefs of people in North India regarding blood donation. Blood Transfus. 2014;12(Suppl 1):s21–s27. doi:10.2450/2012.0058-12.

- Enawgaw B, Yalew A, Shiferaw E. Blood donors’ knowledge and attitude towards blood donation at North Gondar district blood bank, Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):729. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4776-0.

- Olaiya MA, Ajala A, Olatunji RO. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and motivations towards blood donations among blood donors in Lagos, Nigeria. Transfus Med. 2004;14:13–17.

- Sharma UK, Schreiber GB, Glynn SA, et al. Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. Knowledge of HIV/AIDS transmission and screening in United States blood donors. Transfusion. 2001;41:1341–1350.

- Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Ness PM, et al. The contribution of sociodemographic, medical, and attitudinal factors to blood donation among the general public. Transfusion. 2002;42:669–678.

- Glynn SA, Williams AE, Nass CC, et al. Attitudes toward blood donation incentives in the United States: implications for donor recruitment. Transfusion. 2003;43:7–16.

- Jacobs B, Berege ZA. Attitudes and beliefs about blood donation among adults in Mwanza Region, Tanzania. East Afr Med J. 1995;72:345–348.

- Rugege-Hakiza SE, Glynn SA, Hutching ST, et al. Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. Do blood donors read and understand screening educational materials? Transfusion. 2003;43:1075–1083.

- Okpara RA. Attitudes of Nigerians towards blood donation and blood transfusion. Trop Geogr Med. 1989;41:89–93.

- Hosain GM, Anisuzzaman M, Begum A. Knowledge and attitude towards voluntary blood donation among Dhaka University students in Bangladesh. East Afr Med J. 1997;74:549–553.

- Shamebo T, Gedebo C, Damtew M, et al. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of voluntary blood donation among undergraduate students in Awada Campus, Hawassa University, Southern Ethiopia. J Blood Disord Transfus. 2020;10:431. doi:10.35248/2155-9864.20.11.431.

- Ministry of health kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Hematology. Blood donation. Available from: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/HealthAwareness/EducationalContent/Diseases/Hematology/Pages/007.aspx#:~:text=A%20healthy%20adult%20can%20donate,to%20refrain%20from%20donating%20blood. (Accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Baseer S, Maha Ejaz S, Noori M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, perceptions of university students towards blood donation: an assessment of motivation and barriers. Isra Med J. 2017;9:406–410.

- Alam M, MasalmehBel D. Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding blood donation among the Saudi population. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:318–321.