ABSTRACT

Objective

To explore the efficacy and safety of thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) without anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) in ATG-naïve patients with aplastic anemia (AA) in a real-world setting.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated treatment outcomes in 45 consecutive ATG-naïve patients with AA who received TPO-RAs between 2017 and 2021 at our hospital.

Results

ATG ineligibility was due to advanced age (≥ 70 years), n = 22; not recommended under Japanese guidelines due to mild symptoms, n = 13; patient preference, n = 6; uncontrolled heart failure, n = 2; uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, n = 2; chronic renal failure, n = 2; invasive aspergillosis, n = 1. Twenty-eight patients (62%) achieved hematologic response in at least unilineage after 6 months’ treatment, while 38 (84% in unilineage response-eligible patients) and four (25% in trilineage response-eligible patients) patients achieved at least unilineage and trilineage responses, respectively, at any point during the follow-up period. Five patients switched from eltrombopag to romiplostim because of adverse events or lack of efficacy, and two developed hematologic malignancies. Eltrombopag was effective even in elderly ATG-ineligible patients with severe AA. The 2-year overall survival rate was 84.3%, with a median 26.3-month follow-up. Time from diagnosis to eltrombopag treatment initiation tended to affect the response (p = 0.0727), but no factors that significantly predicted hematologic response were identified.

Conclusions

We found eltrombopag to be effective even in elderly ATG-naïve patients with severe AA, indicating that TPO-RA treatment should be considered in patients ineligible for ATG treatment because of age, complications, or severe AA.

Introduction

Aplastic anemia (AA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by pancytopenia and hypoplastic bone marrow [Citation1]. Immunosuppressive treatment with anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) and cyclosporine A (CsA) is the standard therapy for mild to severe AA (SAA) as a first-line treatment for patients ineligible for hematopoietic stem cell-transplantation [Citation1,Citation2].

Recently, thrombopoietin receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) eltrombopag and romiplostim have been shown to promote hematopoiesis not only in refractory AA [Citation3,Citation4], but also in newly diagnosed AA, in combination with ATG and CsA [Citation5]. Most recently, the efficacy of eltrombopag added to standard ATG/CsA immunosuppressive therapy in newly diagnosed severe AA was confirmed in a phase III study [Citation6]. These TPO-RAs activate TPO receptors on megakaryocytes, primitive hematopoietic stem cell and progenitor cells [Citation7]. Based on these findings, recent treatment guidelines suggest that TPO-RAs combined with immunosuppressive therapy should be considered as a standard of care for AA patients [Citation8,Citation9].

However, in real-world clinical practice, ATG treatment is inappropriate for some patients, for reasons including age, comorbid infection, concomitant complications, patient preference, and allergic reaction to ATG. Furthermore, most data on the administration of TPO-RAs in AA patients has been limited to clinical trials, with little evidence reported for TPO-RAs in CsA-refractory ATG-naïve patients [Citation10–13]. Resultingly, the efficacy of TPO-RAs for such patients in the real world remains unclear and is of special interest. Herein, we retrospectively evaluated the outcome of treatment with TPO-RAs, mainly eltrombopag, in patients who did not receive ATG and explored factors potentially predictive of TPO-RA treatment outcome.

Patients and methods

Research participants and study design

We reviewed the medical records of consecutive patients diagnosed with AA between September 2017 and April 2021 at Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital. We retrospectively evaluated 45 ATG-naïve AA patients aged ≥16 years who had been treated with TPO-RAs. We investigated patient characteristics, type and doses of TPO-RA, concomitant therapies during TPO-RA treatment, duration of TPO-RA treatment, hematologic response, adverse events (AEs), time to response, and overall survival (OS).

Eltrombopag was initially administered, in accordance with the approved indications and guidelines for patients with AA in Japan based on no increase in reticulocyte count (<20×109/L from baseline) within two months after initiation of CsA monotherapy [Citation9,Citation12,Citation14,Citation15]. If eltrombopag was ineffective or resulted in serious AEs, it was changed to romiplostim at the treating physicians’ discretion. Briefly, eltrombopag was orally administered starting at 25 mg/day; after two weeks of administration, dose adjustments in increments of 25 mg/day were considered, up to a maximum dose of 100 mg/day. Romiplostim was subcutaneously injected starting at 10 μg/kg once a week; this was adjusted in increments of 5 μg/kg up to a maximum of 20 μg/kg, according to hematopoietic recovery [Citation16]. After achievement of stable trilineage responses, the TPO-RA dosage was decreased gradually and then discontinued while trilineage hematopoiesis was sustained. TPO-RA treatment was resumed when loss of response was observed, again at the treating physicians’ discretion. Cytogenetic analysis (G-band staining and fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH] for chromosome 7q deletion) was performed every 6–12 months or when loss of hematologic response was observed, using bone marrow or peripheral blood samples.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Definitions

AA and the severity of disease have been defined previously [Citation8]. Platelet, erythroid, and neutrophil responses were defined as described previously [Citation17]. Briefly, platelet response was defined as an increase to 20×109/L above baseline in non-transfused patients, or in transfused patients, stable platelet counts with transfusion independence for at least 8 weeks. Erythroid response was defined as an increase in hemoglobin by 1.5 g/dL in non-transfused patients, or in transfused patients, an absolute reduction of at least 4 units of packed red blood cell transfusions for 8 consecutive weeks, compared with the number of transfusions in the 8 weeks prior to treatment. Neutrophil response was defined as a two-fold increase in absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) from a baseline level of <0.5 × 109/L, or an increase in ANC ≥ 0.5 × 109/L from baseline. In patients with platelet counts ≥100 × 109/L, hemoglobin levels ≥9 g/dL, and ANC ≥ 1.0 × 109/L at enrollment, increases in these parameters were not considered for response assessment. Time to hematologic response was defined as the interval from eltrombopag initiation to any hematologic response. OS was defined as the duration from the first day of eltrombopag administration to death from any cause. AEs during TPO-RA treatment were evaluated in accordance with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria, version 5.0 [Citation18].

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test and t-tests, respectively. Differences with a p-value of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method [Citation19]. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR computer software [Citation20].

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty-five AA patients were treated with eltrombopag during the study period (). The median age was 76.5 years (range: 44–88 years). Four patients had abnormal karyotypes (trisomy 8 [n = 1], 13q deletion [n = 1], loss of Y chromosome [n = 2]) at eltrombopag initiation. The median duration of CsA treatment before eltrombopag initiation was 5.5 months (range: 2.1–16.2). ATG-naivety occurred for several reasons: advanced age (≥70 years), n = 22; not recommended under Japanese guidelines [Citation10], n = 13; patient preference, n = 6; uncontrolled heart failure, n = 2; uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, n = 2; chronic renal failure, n = 2; invasive aspergillosis, n = 1.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics

Clinical outcomes

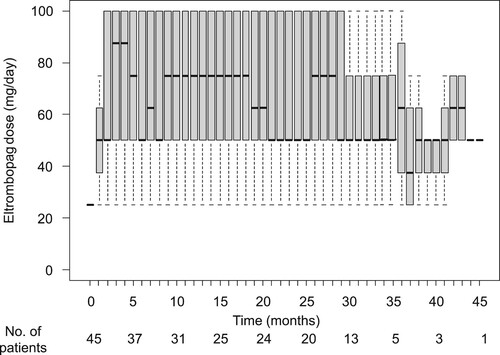

All patients were initially treated with eltrombopag because this drug is orally administered and received earlier approval in Japan than romiplostim. However, five patients switched to romiplostim because of AEs and/or lack of efficacy after median 6.8 months (range: 1.2–13.0) from eltrombopag initiation. After switching, romiplostim was administered for median 18.7 months (range: 6.4–31.2) with no AEs, except for myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in one patient at time of data analysis. CsA was the main concomitant medicine administered to 43 patients, with a median duration of 6.3 months (), followed by metenolone. shows changes in eltrombopag dose over time. Median eltrombopag maintenance doses for responders (in at least unilineage) and non-responders were 75 mg/day (range: 12.5–100) and 50 mg/day (range: 25–100), respectively (p = 0.19). Median eltrombopag administration duration in responders and non-responders was 26.5 months (range: 3.4–45.3) and 4.3 months (range: 2.1–8.4), respectively.

Figure 1. Eltrombopag dose over time. Box plot indicating median (internal horizontal line), 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper box limits, respectively) and 5th–95th percentile (bars).

Table 2. Outcome of TPO-RA treatment.

The 2-year OS rate was 84.3% (95% confidence interval: 67.9–92.7%); five deaths were recorded, with a median follow-up period of 26.3 months (range: 2.1–45.3). Deaths were caused by infections (worsening invasive Aspergillus pneumonia [n = 1], pyelonephritis [n = 1], and aspiration pneumonia [n = 1]) and myeloid malignancy (n = 2).

Hematologic response following TPO-RA treatment

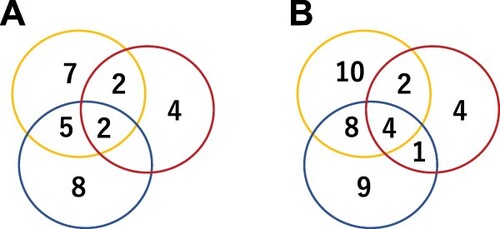

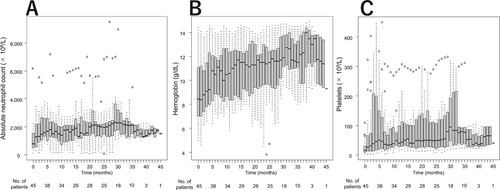

Responses were observed in at least unilineage in 38 cases, with a median time to response of 84 days (range: 6–1027). Trilineage responses were observed in four patients, with a median time to response of 397 days (range: 185–656) ( and , ). shows hematologic response over time. Of 10 transfusion-dependent patients, two became transfusion-independent and the requirement for transfusions was reduced to two. However, one patient became transfusion-dependent after acute myeloid leukemia (AML) onset. At time of analysis, two patients with trilineage responses had TPO-RAs discontinued at 20 and 35 months post-TPO-RA initiation.

Figure 2. Response to TPO-RA by lineage. (A) Number of responders in each lineage at 6 months. (B) Best response during the entire follow-up period. Yellow, platelet; red, erythroid; blue, neutrophil responses.

Figure 3. Response to TPO-RA treatment over time by lineage. (A) neutrophil, (B) erythroid, and (C) platelet responses. Box plots indicate median (internal horizontal line), 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper box limits, respectively) and 5th–95th percentile (bars).

Table 3. Hematologic response to TPO-RAs by lineage.

AEs and myeloid malignancy

AEs were observed in 18 patients (40%; ) during TPO-RA treatment but most were not serious. Regarding serious AEs, grade 2 abdominal pain and grade 3 liver dysfunction developed in a 44-year-old man after two months of eltrombopag initiation. A woman aged 52 developed grade 2 liver dysfunction, grade 2 anorexia and nausea, and grade 1 vomiting after 4 months of eltrombopag initiation. Two further women in their 70s experienced grade 2 anorexia and nausea. In these three female patients, eltrombopag was switched to romiplostim to resolve these AEs. These patients ultimately received the maximum dose of romiplostim, resulting in uni- to trilineage recovery with no further AEs.

Table 4. Adverse events during TPO-RA treatment.

No patient had cytogenetic abnormalities in chromosome 7 detected via FISH during the follow-up period. However, two patients in their 60s with normal karyotypes at eltrombopag initiation developed MDS and AML, respectively. Despite treatment, they eventually died 12 and 20 months post-eltrombopag initiation, respectively.

Factors affecting hematologic response after TPO-RA administration in ATG-naïve AA patients

We investigated the following factors that may affect hematologic response at 6 months: age; sex; AA severity; paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria clone positivity; ANC, reticulocyte, and platelet counts at eltrombopag initiation; eltrombopag maintenance dose; time from diagnosis to eltrombopag treatment initiation (). Time from diagnosis to treatment initiation tended to influence hematologic response in at least unilineage, but this was not significant (p = 0.0727; ). Neither univariate nor multivariate analyses revealed any factors predictive of response.

Table 5. Univariate analysis of factors for response to eltrombopag.

Discussion

Herein, we have demonstrated the efficacy of TPA-RAs without ATG in AA patients in a real-world setting. The median age of the cohort was 76.5 years old, which is higher than that in previous prospective studies (32–53 years) [Citation3–5,Citation12,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22], although one retrospective study [Citation10] demonstrated a median age of ATG-naïve patients of 74 years. Our cohort may therefore be more representative of patients who would typically be ATG treatment-naïve in daily clinical practice. Thirty-two patients were ineligible for ATG treatment because of their age (≥70 years) and/or comorbidities, while a further 13 had only mild symptoms and were not indicated for ATG treatment under Japanese guidelines [Citation9]. Hematologic response in at least unilineage was observed in 62% of patients at 6 months from eltrombopag initiation, and a best response was observed in 84% of patients regardless of time. A trilineage response was observed in 25% of eligible patients at some point during the follow-up period. The median time to achieve hematologic response in at least unilineage or trilineage were 84 and 397 days, respectively.

Several prospective and retrospective studies have been published regarding the efficacy and safety of TPO-RA for newly diagnosed and refractory AA [Citation3–5,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22]. Of these, the response rates for in at least unilineage and trilineage hematologic response were 44–84% and 19–36%, respectively. In these studies, most patients had previously received ATG, and one study demonstrated that such patients exhibited faster hematopoietic cell recovery (transfusion independence rate at 3 months: 44% vs 0%) and a slightly better hematologic response rate than ATG-naïve patients (at least unilineage response rate: 74% vs 64%; trilineage response rate: 34% vs 27%) [Citation10]. Despite the small patient numbers and caveats concerning comparisons of independent studies, the hematologic response rates and speed of hematopoietic recovery in our study are similar to the results of previous reports, including those involving younger patients and cases previously treated with ATG.

Our cohort included 10 patients with SAA. Of these, six were over 75 years old, with at least unilineage and trilineage hematologic response rates of 66% and 33%, respectively, in this group. Immunosuppressive therapy is effective regardless of patient age. Moreover, a recent study showed age, per se, is not a limiting factor for use of ATG in AA patients [Citation2]. The combination of ATG plus CsA remains the standard of care for AA even in elderly patients. However, the mortality rate is likely to be higher in older patients than younger individuals, especially in poor performance status and comorbid patients [Citation2,Citation23]. Therefore, clinicians should be cautious when administering ATG to elderly patients. Meanwhile, previous case reports have demonstrated the efficacy of eltrombopag without ATG for treating SAA [Citation24,Citation25]. Our findings are consistent with these reports even in elderly patients, suggesting that TPO-RA may be administered to elderly SAA patients ineligible for ATG.

The safety profile of eltrombopag treatment in this study was similar to that in previous studies [Citation3,Citation5,Citation12]. The most frequent AEs were anorexia and nausea, generally resolving within 2–4 weeks of eltrombopag discontinuation or reduction. Although AEs did not recur in most patients when eltrombopag was reinitiated, three female patients suffered recurrence, prompting the switch to romiplostim. After switching, their symptoms were completely resolved. Most AEs were not serious and less likely associated to age. However, anorexia and nausea were more often observed in female patients, although further study is necessary to confirm these findings because of the small number of patients in this study.

At time of data analysis, five patients had switched from eltrombopag to romiplostim due to inefficacy and/or AE. After drug switching, hematologic response was improved in four patients with but not in one, who suffered onset of MDS. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have shown that TPO-RA switching is effective in clinical practice [Citation11]. In this study, eltrombopag dosage tended to affect hematologic response. An adequate TPO-RA dosage appears to be necessary for hematological recovery, indicating that switching to another TPO-RA should be considered if the first TPO-RA fails because an adequate dosage cannot be provided.

Our study cohort included two patients who developed hematological malignancy. These patients eventually died due to AML and MDS. Previously, clonal evolution and AML have been observed at an incidence of 0%–19% and 0%–4%, respectively, during TPO-RA treatment of AA [Citation3–5,Citation10,Citation12,Citation13,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22,Citation26]. However, secondary MDS or AML occurs in 15%–20% of AA patients regardless of TPO-RA use [Citation27]. TPO-RAs can stimulate expansion of hematopoietic stem cell via the c-MPL signaling pathway [Citation7], which could potentially affect the emergence of abnormal clones. Therefore, long-term follow-up and close surveillance of TPO-RA-treated patients are essential.

We did not find any factors that significantly predicted hematologic response to eltrombopag treatment. A short period from AA diagnosis to treatment initiation was likely to predict hematologic response but was not significant. Previous studies have shown that high reticulocyte counts and short intervals from first immunosuppressive therapy to eltrombopag initiation were likely to predict hematologic response to eltrombopag [Citation3,Citation26]. While sufficient hematopoietic stem cells remain in the bone marrow, introduction of TPO-RAs may effectively stimulate hematologic response.

Limitations of this study include the retrospective observational nature of the study, with a small number of patients treated at one institution; the impact of CsA on outcome in this study was not completely eliminated. Previous study has indicated that the response rate to CsA monotherapy in patients with no increase in the reticulocyte count within two months of CsA monotherapy is low [Citation15]. Therefore, if the reticulocyte count does not increase after two months of CsA monotherapy, Japanese guidelines recommend the addition of eltrombopag to CsA [Citation9]. Although eltrombopag was initially developed as a single agent in refractory AA [Citation3], its combination with CsA is common in the real world [Citation28]. Because of the good tolerability and different modes of action in these agents, it is rational to use this combination with the expectation of complementary or synergistic action. However, the benefit of this combination in the refractory setting has not yet been established, nor we can exclude the effect of CsA on the treatment response over the entire study period. The decisions to switch from pretreatment to TPO-RA and from eltrombopag to romiplostim were left to the treating physicians’ discretion; clonal evolution was not evaluated systematically, therefore may occur more frequently than was documented here.

In conclusion, we investigated the efficacy of TPO-RAs in ATG-naïve AA patients. Our findings reflect real-world TPO-RA treatment in patients with AA and suggest that TPO-RAs should be considered in refractory AA, SAA or ATG-ineligible cases. Further studies may identify factors that predict hematologic response. Better understanding of TPO-RA action in AA and optimized use of TPO-RA in AA patients could improve treatment strategies, leading to successful long-term treatment of ATG-naïve AA patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank Gillian Campbell, PhD, from Edanz (https://www.jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Young NS. Aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1643–1656.

- Contejean A, Resche-Rigon M, Tamburini J, et al. Aplastic anemia in the elderly: a nationwide survey on behalf of the French Reference Center for Aplastic Anemia. Haematologica. 2019;104(2):256–262.

- Olnes MJ, Scheinberg P, Calvo KR, et al. Eltrombopag and improved hematopoiesis in refractory aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(1):11–19.

- Lee JW, Lee S, Jung CW, et al. Romiplostim in patients with refractory aplastic anaemia previously treated with immunosuppressive therapy: a dose-finding and long-term treatment phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(11):e562–e572.

- Townsley DM, Scheinberg P, Winkler T, et al. Eltrombopag added to standard immunosuppression for aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1540–1550.

- Peffault de Latour R, Kulasekararaj A, Iacobelli S, et al. Eltrombopag added to immunosuppression in severe aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(1):11–23.

- Zeigler BFC, de Sauvage F, Widmer HR, et al. In vitro megakaryocytopoietic and thrombopoietic activity of c-mpl ligand (TPO) on purified murine hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 1994;84(12):4045-4052.

- Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172(2):187–207.

- Nakao S, Hama M, Ohashi H, et al. Reference guide for the treatment of aplastic anemia. 2019 revised version. [cited 2021 September 26]. http://zoketsushogaihan.umin.jp/file/2020/02.pdf.

- Lengline E, Drenou B, Peterlin P, et al. Nationwide survey on the use of eltrombopag in patients with severe aplastic anemia: A report on behalf of the French Reference Center for Aplastic Anemia. Haematologica. 2018;103(2):212–220.

- Ise M, Iizuka H, Kamoda Y, et al. Romiplostim is effective for eltrombopag-refractory aplastic anemia: results of a retrospective study. Int J Hematol. 2020;112(6):787–794.

- Yamazaki H, Ohta K, Iida H, et al. Hematologic recovery induced by eltrombopag in Japanese patients with aplastic anemia refractory or intolerant to immunosuppressive therapy. Int J Hematol. 2019;110(2):187–196.

- Hwang YY, Gill H, Chan TSY, et al. Eltrombopag in the management of aplastic anemia: real-world experience in a non-trial setting. Hematology. 2018;23(7):399–404.

- REVOLADE Tablets prescribing information. (2018). [cited 2021 September 26]. https://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack/3999028F1025_2_05/?view=frame&style=SGML&lang=ja.

- Yamazaki H, Sugimori C, Chuhjo T, et al. Cyclosporine therapy for acquired aplastic anemia: predictive factors for the response and long-term prognosis. Int J Hematol. 2007;85(3):186–190.

- Romiplate for S.C. Injection prescribing information. . (2020). [cited 2021 September 26]. https://www.info.pmda.go.jp/go/pack/3999430D1024_1_07/?view=frame&style=XML&lang=ja.

- Desmond R, Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, et al. Eltrombopag restores trilineage hematopoiesis in refractory severe aplastic anemia that can be sustained on discontinuation of drug. Blood. 2014;123(12):1818–1825.

- Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0. [cited 2021 September 26]. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5(11.pdf.

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. Source J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457–481.

- Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48(3):452–458.

- Fan X, Desmond R, Winkler T, et al. Eltrombopag for patients with moderate aplastic anemia or uni-lineage cytopenias. Blood Adv. 2020;4(8):1700–1710.

- Jang JH, Tomiyama Y, Miyazaki K, et al. Efficacy and safety of romiplostim in refractory aplastic anaemia: a Phase II/III, multicentre, open-label study. Br J Haematol. 2021;192(1):190–199.

- Tichelli A, Socié G, Henry-Amar M, et al. Effectiveness of immunosuppressive therapy in older patients with aplastic anemia. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(3):193–201.

- Rodgers GM, Gilreath JA. Eltrombopag as initial monotherapy for severe aplastic anemia - a case report. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(8):1517–1518.

- Cheng H, Wang X, Zhou D, et al. Eltrombopag combined with cyclosporine may have an effective on very severe aplastic anemia. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(8):2009–2011.

- Winkler T, Fan X, Cooper J, et al. Treatment optimization and genomic outcomes in refractory severe aplastic anemia treated with eltrombopag. Blood. 2019;133(24):2575–2585.

- Sun L, Babushok DV. Secondary myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia in acquired aplastic anemia and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. Blood. 2020;136(1):36–49.

- Ecsedi M, Lengline E, Knol-Bout C, et al. Use of eltrombopag in aplastic anemia in Europe. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(6):1341–1350.