ABSTRACT

Objectives

To analyse the clinical characteristics and therapeutic response of Chinese patients with primary extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma DLBCL (PE-DLBCL).

Methods

We analysed the clinical features and outcomes of 197 patients who were newly diagnosed with PE-DLBCL between January 2015 and December 2020.

Results

The gastrointestinal tract showed the highest rate of involvement (34%), followed by the central nervous system (CNS) and intraocular system (31.5%). The 3-year overall survival (OS) rate was 81% for the entire group and 79% for those with CNS and vitreoretinal involvement. Ann Arbour stage, lactate dehydrogenase level, International Prognostic Index > 2, and complete remission (CR) were significantly related to the survival of patients with PE-DLBCL. The lack of CR was the only independent adverse prognostic factor for OS.

Conclusion

The clinical outcomes of patients with PE-DLBCL at our centre were encouraging, especially for patients with CNS and vitreoretinal involvement.

Introduction

Malignant lymphomas, which represent a diverse group of diseases, may arise in tissues other than lymph nodes. However, the definition of extranodal lymphomas remains controversial, especially when both lymph nodes and extranodal sites are involved. On the basis of previous studies[Citation1–4], lymphoma is defined as primarily extranodal if (1) the dominant lesions are present at extranodal sites, and (2) lymph node involvement is only minor or absent. The prevalence of primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (PE-NHL) varies across countries and ranges from 8.7% to 48%[Citation5–8]. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common (71%−81.3%) pathological subtype of PE-NHL[Citation4, Citation9]. Primary extranodal DLBCL (PE-DLBCL) originates from nearly every extranodal site of the body, especially in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, followed by the nasopharynx and neck, breast, central nervous system (CNS), skin, bone, thyroid, testis, and rarely other sites[Citation4, Citation10, Citation11].

PE-DLBCLs are well-recognised heterogeneous entities. However, relevant research on these entities is extremely limited. Studies by Shi et al. and Shen et al. showed that the prognosis of extranodal DLBCLs is unsatisfactory [Citation12, Citation13]; however, a large proportion of patients in their studies could not afford rituximab. A 13% improvement in 2-year overall survival (OS) has been reported by combining rituximab with the cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP) regimen in elderly patients[Citation14]. In addition, the 5-year OS was 58% in patients who received the rituximab and CHOP (R-CHOP) regimen versus 45% in those who received CHOP alone[Citation15]. We aimed to identify the improvement in the prognosis of patients with PE-DLBCL in an era in which everyone can afford rituximab. Our centre has also made significant efforts to standardize treatment, ensure intensive induction, and strengthen central prevention. Thus, the main objective of this study was to analyse the specific clinical characteristics, treatment response, and survival of patients with PE-DLBCLs in a single centre in China in this new era.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients with incomplete clinical data and those who were diagnosed at our hospital but did not receive treatment were excluded (n = 25). A total of 644 patients who were newly diagnosed with DLBCL between January 2015 and December 2020 at our hospital were included, and 197 patients diagnosed with PE-DLBCL were evaluated. All biopsy specimens were independently classified by three specialized pathologists according to the WHO classification protocol [Citation16].

Baseline data, such as sex, age, Ann Arbour stage, performance status, extranodal sites, complete blood count (CBC) parameters, and biochemical routine indices, including the levels of liver enzymes, creatinine, serum albumin, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), were collected. Essential imaging evaluations, such as positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) and whole-body computed tomography (CT), were performed before and after treatment. Patients with lymphoma were staged using the Ann Arbour classification scheme[Citation17] and evaluated according to the International Prognostic Index (IPI)[Citation18]. PE-DLBCL with CNS or gastrointestinal involvement was evaluated using the IELSG score[Citation19] and Lugano classification[Citation20], respectively.

Treatment, response, and follow-up

The first-line treatment for patients with PE-DLBCL, except for PCNS-DLBCLs, was the R-CHOP regimen[Citation14] or the rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide (R-EPOCH) regimen[Citation21] for patients with double-protein expression. The regimen was administered every three weeks over 6–8 cycles. For some patients, methotrexate (MTX; 1 g/m2, four times) was added for CNS prophylaxis in induction therapy[Citation22]. Local and systemic therapies were applied in patients with primary vitreoretinal DLBCL (PVR-DLBCL): intravitreal methotrexate injections for one year (400 µg, total 16 injections) and the R2 regimen, which included six cycles of lenalidomide (25 mg on day 1-21) and rituximab (375 mg/m2 on day 1)[Citation23]. Other cases of PCNS-DLBCL were treated with high-dose methotrexate (3.5 g/m2)-based combined chemotherapies. The regimen was administered every three weeks over 6–8 cycles. In some patients, surgery was performed to confirm the diagnosis and reduce the tumour burden. Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is recommended for relapsed/refractory or high-risk patients.

The response to treatment was assessed according to the International Working Group criteria[Citation24]. Eighteen patients were lost to follow-up by the end of the follow–up period (December 31, 2021).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for inclusion in the study.

Statistical analysis

Outcomes were described as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). PFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to the first disease progression or death for any reason. The OS was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of the last follow-up or death for any reason. GraphPad Prism (version 9.0) was used to perform statistical analysis. Univariate analysis and generation of survival curves were performed using Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests. Variables with a P value < 0.1 were selected for multivariate Cox regression analysis. Differences were evaluated using a two-tailed test; P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Patients newly diagnosed with PE-DLBCL accounted for 30.6% (197/644) of all the DLBCL patients in our study. The median age was 58 years (range, 19-91) years, and 90 patients (45.7%) were men. Patients with CNS, intraocular, bone, and thyroid involvement had worse physical status than those with involvement in other areas. B symptoms were less common in patients with CNS (7/48, 14.6%), nose/nasopharynx (1/14, 7.1%), breast (2/10, 20%), or testis (1/7, 14.3%) involvement.

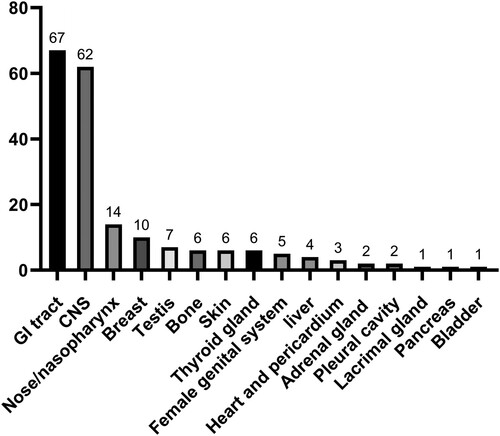

The major sites of involvement in the patients with PE-DLBCL are presented in . The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) was the most common site of PE-DLBCL involvement, accounting for 34% of cases (stomach, 36; duodenum/jejunum, 20; and colon, 11). Patients with CNS and intraocular involvement ranked second (62, 31.5%), followed by those with nose/nasopharynx (14, 7.1%), breast (10, 5.1%), testis (7, 3.6%), bone, skin, thyroid gland (6 patients [3%] each), female genital system (5, 2.5%), and liver (4, 2%) involvement. shows the site distribution of extranodal lymphomas. Subgroups with fewer than five patients were excluded from the subsequent survival analysis.

Table 1. Patient characteristics according to the primary involved site.

Response to treatment and survival

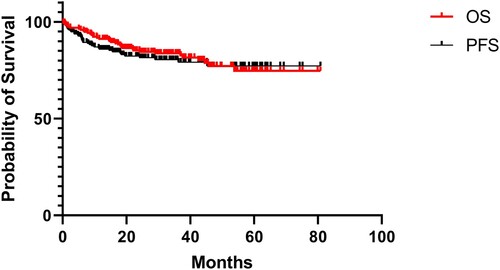

In this study, 9.1% of the patients with PE-DLBCL were lost to follow-up. The median follow-up period was 31.8 months (range, 0.2-80.8 months). At the last follow-up, 35.6% (69/194) of the patients had experienced disease relapse and 19.6% (35/179) had died. The clinical outcomes of PE-DLBCL are presented below (). The 3-year OS rates of the patients with primary GI tract, eye + CNS, nose/nasopharynx, breast, FGS, bone, thyroid gland, testis, and skin involvement were 84%, 79%, 83%, 86%, 100%, 80%, 83%, 100%, and 67%, respectively.

Figure 2. Clinical outcomes for patients with PE-DLBCL. Overall survival and progression-free survival for patients with PE-DLBCL.

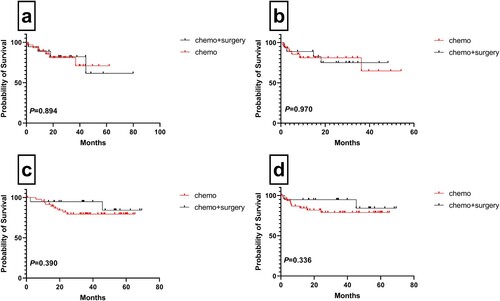

A total of 117 (59.3%) patients achieved CR and 21 (10.6%) achieved partial response (PR), leading to a total response rate (RR) of 70.1%. The RR for patients with PCNS-DLBCL and PVR-DLBCL was 67.8%, while the RR for patients with nose/nasopharynx, thyroid gland, testis, breast, GI tract, bone, skin, liver, and FGS involvement was 92.9%, 83.3%, 75%, 70%, 68.7%, 66.7%, 57.1%, 50%, and 33.3%, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed between the clinical outcomes of both PCNS-DLBCL and primary gastrointestinal (PGI)-DLBCL patients who had not undergone surgery ().

Figure 3. Clinical outcomes for patients with PCNS-DLBCL and PGI-DLBCL. Overall survival (a) and progression-free survival (b) of PCNS-DLBCL patients with and without surgery; Overall survival (c) and progression-free survival (d) of PGI-DLBCL patients with and without surgery.

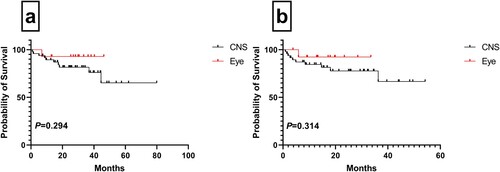

One (9.1%) patient with primary vitreoretinal DLBCL (PVR-DLBCL) died during our study period. Nine of the 11 patients with PVR-DLBCL (64.3%) achieved CR after first-line therapy, and 78.6% (11/14) experienced disease relapse, of which five patients showed CNS relapse. Complete remission, relapse, and mortality rates were 45.8% (22/48), 56.2% (27/48), and 20.8% (10/48), respectively, in patients with PCNS-DLBCL. No statistically significant differences were observed in the clinical outcomes between the two groups of patients (PCNS-DLBCL vs. PVR-DLBCL) ().

Figure 4. Clinical outcomes for patients with central nervous system and vitreoretinal involvement. Overall survival (a) of DLBCL patients with central nervous system and vitreoretinal involvement. Progression-free survival (b) of DLBCL patients with central nervous system and vitreoretinal involvement.

Prognostic factors

The univariate and multivariate analysis results for patients with PE-DLBCL are presented in . On the basis of the univariate results, Ann Arbour stage, LDH level, IPI > 2, not receiving CR, and double hit were significantly associated with survival. However, in the multivariate analysis, failure to achieve CR after first-line therapy was an independent predictor of OS and PFS in patients with PE-DLBCL.

Table 2. Risk factors for survival in patients with PE-DLBCL.

The univariate and multivariate analyses results for PGI-DLBCL are presented in . According to the univariate results, B symptoms, LDH, IPI > 2, Lugano stage, failure to achieve CR, and double hits were significantly related to the survival of patients with PGI-DLBCL. The independent risk factors for PFS included not receiving CR and Lugano stage IV disease in the multivariate analysis. The risk factors for survival in patients with PCNS-DLBCL and PVR-DLBCL are shown in .

Table 3. Risk factors for survival in patients with PGI-DLBCL.

Table 4. Risk factors for survival in patients with PCNS-DLBCL and PVR-DLBCL.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is a cohort of extranodal lymphomas showing fairly good clinical outcomes in the last five years. Thus, the prognosis of PE-DLBCL has improved in the era of rituximab therapy.

Different extranodal involvement sites are associated with distinct clinical characteristics. Our centre treated slightly more female patients than male patients with PE-DLBCL [Citation25–27]. Among the patients with PE-DLBCL, 38.1% were in the advanced stage when diagnosed, whereas primary nodal DLBCL was more frequently classified as stage III-IV[Citation25, Citation28, Citation29]. Some patients may show earlier local symptoms due to a tumour mass. In addition, different definitions for primary extranodal lymphoma can also lead to these differences[Citation3, Citation30].

AlShemmari and Lu et al. reported that the gastrointestinal tract is the most common site of extranodal involvement, while involvement of other sites is rare[Citation4, Citation31]. However, patients with CNS and intraocular involvement also accounted for a high proportion of the cases in our study, partly because of the conduct of clinical trials, which will lead to considerable differences in subsequent analyses.

For patients with PCNS-DLBCL, in comparison with the findings of the largest descriptive study in China, the cases treated at our centre showed a better outcome. Surgical excision for intracranial PCNS-DLBCL has been shown to not improve survival[Citation32, Citation33], which is consistent with our results. Systemic chemotherapy combined with intravitreal chemotherapeutic drug injection for patients with primary vitreoretinal DLBCL (PVR-DLBCL) as the initial treatment may achieve a relatively better outcome[Citation23]. Hernandez et al. reported that lenalidomide[Citation34] had a prominent effect on DLBCL, particularly on non-GCB subtypes. Hernandez et al. confirmed that a combination of rituximab and lenalidomide (R2) can lead to a good synergistic effect[Citation35]. The R2 regimen was recently reported to show significant activity in patients with relapsed/refractory PVRL and PCNSL[Citation36]. Our centre began to use the R2-MTX regimen as the first choice for standard induction chemotherapy for newly diagnosed PCNS-DLBCL, and reported an ORR of 100% (NCT 04120350). However, despite advances in initial treatment, more than 1/3 of the patients show disease relapse[Citation37], and there are no uniform treatment guidelines for relapsed and refractory PCNSL (R/R PCNSL). In this study, no statistically significant difference was observed in survival between patients with PVR-DLBCL and PCNS-DLBCL; this may be attributed to the higher relapse rate of PVR-DLBCL, which was mostly associated with central relapse. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor[Citation38] and PD-1 blockade[Citation39] therapies show good antitumour activity in R/R PCNSL. Six patients with R/R PCNSL treated with orelabrutinib plus sintilimab achieved PR/CR in this study and are still under follow-up. Thus, with the ongoing development of newer treatment modalities and monitoring tools, these patients have a more promising future.

In the rituximab era, fewer scholars, such as Wang et al., believe that surgical treatment can achieve a better prognosis than conservative treatment[Citation40]. Most studies have shown that surgical treatment plays an increasingly inconspicuous role in the treatment of PGI-DLBCL and is mostly used for definitive diagnosis or clinical emergencies[Citation41, Citation42]. The data from our study also showed no significant difference in the outcomes of patients receiving chemotherapy alone and those treated with surgery combined with chemotherapy. The value of probable prognostic factors such as sex, LDH levels, B symptoms, and the IPI in patients with PGI-DLBCL remains controversial[Citation43–45]. In this regard, we agree with previously reported studies that the Lugano stage can effectively predict the prognosis of PGI-DLBCL[Citation27, Citation46].

Although univariate analysis showed differences in IPI, LDH, DH, Ann Arbour stage, and achievement of CR following first-line treatment, achievement of CR was identified as a factor leading to better survival in our study, which was different from the finding in our previous retrospective study[Citation13] and research data from other centers[Citation26]. This can be explained by the selection bias for hospitalized patients and the fact that the increasing availability of alternative immuno-targeted therapies has reduced the differences in outcomes associated with different baseline characteristics. The short follow-up period in our study is another factor that cannot be ignored. To achieve CR in first-line treatment, we administered intensive induction therapy to some patients with double-protein expression, which also proved to yield better efficacy. Simultaneously, the findings also indicate the need for a better prognostic integral model for PE-DLBCL in the future[Citation47–49].

Different sites of extranodal involvement are associated with widely varying clinical outcomes[Citation31, Citation50]. Comparative analyses in the largest comprehensive descriptive study in China[Citation12] and the SEER database[Citation51], which includes data for clinical outcomes in relation to the anatomical distribution of DLBCL, showed that the PE-DCLBL patients in our cohort had a better prognosis. However, longer follow-up periods are required to confirm this finding. In our study, primary bone DLBCL and primary thyroid gland DLBCL(PT-DLBCL) were associated with a better prognosis, consistent with previous reports[Citation52–54]. Two-thirds of patients with PT-DLBCL underwent total or subtotal thyroidectomy, which has been proven to be associated with significantly improved survival[Citation55]. In other studies, primary testis DLBCL was related to a higher CNS relapse rate and unfavourable outcomes [Citation56, Citation57]. Of the 4/7 patients in our study who received MTX for CNS prophylaxis, which is still controversial[Citation58, Citation59], only one showed central recurrence, and all had favourable clinical outcomes.

In summary, our study demonstrated that different sites of extranodal involvement in patients were associated with different clinical features and outcomes. The clinical outcome of PE-DLBCL at our centre has been greatly improved through standardized treatment, the addition of immune-targeted drugs such as lenalidomide, the use of local plus systemic treatment for PVR-DLBCL in cooperation with the ophthalmology department, and the application of intravenous MTX prophylaxis for central high-risk groups.

Author contributions

JZ analyzed and interpreted the patient data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. DBZ and ZW conceived and designed the work that led to the submission, acquired data and had an important role in interpreting the results. WZ gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article [and/or] its supplementary materials.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Reference

- Dawson IM, Cornes JS, Morson BC. Primary malignant lymphoid tumours of the intestinal tract. Report of 37 cases with a study of factors influencing prognosis. Br J Surg. 1961 Jul;49:80–89.

- Economopoulos T, Asprou N, Stathakis N, et al. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in adults: clinicopathological and survival characteristics. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996 Mar;21(1-2):131–136.

- d'Amore F, Christensen BE, Brincker H, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognostic factors in extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Danish LYFO Study Group. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27(10):1201–1208.

- AlShemmari SH, Ameen RM, Sajnani KP. Extranodal lymphoma: a comparative study. Hematology. 2008 Jun;13(3):163–169.

- Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, et al. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Part 1: Gastrointestinal, cutaneous and genitourinary lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 1997 Aug;8(8):727–737.

- Zucca E, Roggero E, Bertoni F, et al. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Part 2: Head and neck, central nervous system and other less common sites. Ann Oncol. 1999 Sep;10(9):1023–1033.

- Krol AD, le Cessie S, Snijder S, et al. Primary extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL): the impact of alternative definitions tested in the Comprehensive Cancer Centre West population-based NHL registry. Ann Oncol. 2003 Jan;14(1):131–139.

- Candelaria M, Oñate-Ocaña LF, Corona-Herrera J, et al. CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PRIMARY EXTRANODAL VERSUS NODAL DIFFUSE LARGE B-CELL LYMPHOMA: A RETROSPECTIVE COHORT STUDY IN A CANCER CENTER. Rev Invest Clin. 2019;71(5):349–358.

- Yun J, Kim SJ, Won JH, et al. Clinical features and prognostic relevance of ovarian involvement in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) report. Leuk Res. 2010 Sep;34(9):1175–1179.

- Yun J, Kim SJ, Kim JA, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas involving rare extranodal sites: a single-center experience. Acta Haematol. 2010;123(1):48–54.

- Reddy S, Pellettiere E, Saxena V, et al. Extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. 1980 Nov 1;46(9):1925–1931.

- Shi Y, Han Y, Yang J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma based on nodal or extranodal primary sites of origin: Analysis of 1,085 WHO classified cases in a single institution in China. Chin J Cancer Res. 2019 Feb;31(1):152–161.

- Shen H, Wei Z, Zhou D, et al. Primary extra-nodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A prognostic analysis of 141 patients. Oncol Lett. 2018 Aug;16(2):1602–1614.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jan 24;346(4):235–242.

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Jun 20;23(18):4117–4126.

- Polyatskin IL, Artemyeva AS, Krivolapov YA. [Revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues, 2017 (4th edition):lymphoid tumors]. Arkh Patol. 2019;81(3):59–65.

- Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, et al. Report of the Committee on Hodgkin's Disease Staging Classification. Cancer Res. 1971 Nov;31(11):1860–1861.

- Shipp MA. A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993 Sep 30;329(14):987–994.

- Ferreri AJ, Blay JY, Reni M, et al. Prognostic scoring system for primary CNS lymphomas: the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 15;21(2):266–272.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Sep 20;32(27):3059–3068.

- Wilson WH, Grossbard ML, Pittaluga S, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH chemotherapy for untreated large B-cell lymphomas: a pharmacodynamic approach with high efficacy. Blood. 2002 Apr 15;99(8):2685–2693.

- Wang W, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Intravenous methotrexate at a dose of 1 g/m(2) incorporated into RCHOP prevented CNS relapse in high-risk DLBCL patients: A prospective, historic controlled study. Am J Hematol. 2020 Apr;95(4):E80–e83.

- Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zou D, et al. Lenalidomide and Rituximab Regimen Combined With Intravitreal Methotrexate Followed by Lenalidomide Maintenance for Primary Vitreoretinal Lymphoma: A Prospective Phase II Study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:701507.

- Cheson BD, Pfistner B, Juweid ME, et al. Revised response criteria for malignant lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Feb 10;25(5):579–586.

- Castillo JJ, Winer ES, Olszewski AJ. Sites of extranodal involvement are prognostic in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Am J Hematol. 2014 Mar;89(3):310–314.

- Lal A, Bhurgri Y, Vaziri I, et al. Extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas–a retrospective review of clinico-pathologic features and outcomes in comparison with nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008 Jul-Sep;9(3):453–458.

- Huang J, Jiang W, Xu R, et al. Primary gastric non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Chinese patients: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. BMC Cancer. 2010 Jul 6;10:358.

- A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood. 1997 Jun 1;89(11):3909–3918.

- Møller MB, Pedersen NT, Christensen BE. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical implications of extranodal versus nodal presentation–a population-based study of 1575 cases. Br J Haematol. 2004 Jan;124(2):151–159.

- Lewin KJ, Ranchod M, Dorfman RF. Lymphomas of the gastrointestinal tract: a study of 117 cases presenting with gastrointestinal disease. Cancer. 1978 Aug;42(2):693–707.

- Lu CS, Chen JH, Huang TC, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: sites of extranodal involvement are a stronger prognostic indicator than number of extranodal sites in the rituximab era. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015 Jul;56(7):2047–2055.

- Ouyang T, Wang L, Zhang N, et al. Clinical Characteristics, Surgical Outcomes, and Prognostic Factors of Intracranial Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma. World Neurosurg. 2020 Jul;139:e508–e516.

- Labak CM, Holdhoff M, Bettegowda C, et al. Surgical Resection for Primary Central Nervous System Lymphoma: A Systematic Review. World Neurosurg. 2019 Jun;126:e1436–e1448.

- Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Deeb G, Zinzani PL, et al. Higher response to lenalidomide in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in nongerminal center B-cell-like than in germinal center B-cell-like phenotype. Cancer. 2011 Nov 15;117(22):5058–5066.

- Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Reddy N, Holkova B, et al. Immunomodulatory drug CC-5013 or CC-4047 and rituximab enhance antitumor activity in a severe combined immunodeficient mouse lymphoma model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005 Aug 15;11(16):5984–5992.

- Ghesquieres H, Chevrier M, Laadhari M, et al. Lenalidomide in combination with intravenous rituximab (REVRI) in relapsed/refractory primary CNS lymphoma or primary intraocular lymphoma: a multicenter prospective ‘proof of concept’ phase II study of the French Oculo-Cerebral lymphoma (LOC) Network and the Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA)†. Ann Oncol. 2019 Apr 1;30(4):621–628.

- Jahnke K, Thiel E, Martus P, et al. Relapse of primary central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, outcome and prognostic factors. J Neurooncol. 2006 Nov;80(2):159–165.

- Grommes C, Tang SS, Wolfe J, et al. Phase 1b trial of an ibrutinib-based combination therapy in recurrent/refractory CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2019 Jan 31;133(5):436–445.

- Nayak L, Iwamoto FM, LaCasce A, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed/refractory primary central nervous system and testicular lymphoma. Blood. 2017 Jun 8;129(23):3071–3073.

- Wang YG, Zhao LY, Liu CQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of primary gastric lymphoma: A retrospective study with 165 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Aug;95(31):e4250.

- Lightner AL, Shannon E, Gibbons MM, et al. Primary Gastrointestinal Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma of the Small and Large Intestines: a Systematic Review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016 Apr;20(4):827–839.

- Ge Z, Liu Z, Hu X. Anatomic distribution, clinical features, and survival data of 87 cases primary gastrointestinal lymphoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2016 Mar 18;14:85.

- Ferreri AJ, Montalbán C. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the stomach. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007 Jul;63(1):65–71.

- Mok TS, Steinberg J, Chan AT, et al. Application of the international prognostic index in a study of Chinese patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and a high incidence of primary extranodal lymphoma. Cancer. 1998 Jun 15;82(12):2439–2448.

- d'Amore F, Brincker H, Grønbaek K, et al. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract: a population-based analysis of incidence, geographic distribution, clinicopathologic presentation features, and prognosis. Danish Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1994 Aug;12(8):1673–1684.

- Cortelazzo S, Rossi A, Roggero F, et al. Stage-modified international prognostic index effectively predicts clinical outcome of localized primary gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG). Ann Oncol. 1999 Dec;10(12):1433–1440.

- Gao F, Wang ZF, Tian L, et al. A Prognostic Model of Gastrointestinal Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma. Med Sci Monit. 2021 Aug 27;27:e929898.

- Hwang HS, Yoon DH, Suh C, et al. Intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an evaluation of different staging systems. J Korean Med Sci. 2014 Jan;29(1):53–60.

- Hwang HS, Yoon DH, Suh C, et al. A new extranodal scoring system based on the prognostically relevant extranodal sites in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified treated with chemoimmunotherapy. Ann Hematol. 2016 Aug;95(8):1249–1258.

- Takahashi H, Tomita N, Yokoyama M, et al. Prognostic impact of extranodal involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Cancer. 2012 Sep 1;118(17):4166–4172.

- Yin X, Xu A, Fan F, et al. Incidence and Mortality Trends and Risk Prediction Nomogram for Extranodal Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma: An Analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database. Front Oncol. 2019;9:1198.

- Matikas A, Briasoulis A, Tzannou I, et al. Primary bone lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of 22 patients treated in a single tertiary center. Acta Haematol. 2013;130(4):291–296.

- Huan Y, Qi Y, Zhang W, et al. Primary bone lymphoma of radius and tibia: A case report and review of literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Apr;96(15):e6603.

- Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Frommelt RA, et al. Malignant lymphoma of the thyroid gland: a clinicopathologic study of 108 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000 May;24(5):623–639.

- Vardell Noble V, Ermann DA, Griffin EK, et al. Primary Thyroid Lymphoma: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. Cureus. 2019 Feb 18;11(2):e4088.

- Koukourakis G, Kouloulias V. Lymphoma of the testis as primary location: tumour review. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010 May;12(5):321–325.

- Xu H, Yao F. Primary testicular lymphoma: A SEER analysis of 1,169 cases. Oncol Lett. 2019 Mar;17(3):3113–3124.

- Vitolo U, Chiappella A, Ferreri AJ, et al. First-line treatment for primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with rituximab-CHOP, CNS prophylaxis, and contralateral testis irradiation: final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Jul 10;29(20):2766–2772.

- Kridel R, Dietrich PY. Prevention of CNS relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Dec;12(13):1258–1266.