ABSTRACT

Introduction

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are the most frequently recognized entities among lymphoproliferative syndromes and rank fifth among neoplasms not associated with gender. There is scarce information on the clinical characteristics of the most frequent NHL, and no data on treatment regimens and their outcomes in Latin America. Although many factors affect a patient’s possibilities of receiving treatment, the annual income per person/country is pivotal in Latin America.

Aim

We present the clinical characteristics, risk groups, and treatment regimens of the three most frequent lymphoma subtypes in Latin America [diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), and peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL)], based on the data collected by the largest study group of lymphoproliferative diseases in Latin America: The Latin American Study Group of Lymphoproliferative Disease [Grupo de Estudio de Linfoproliferativos de Latino America (GELL)].

Outcomes

The most frequent treatment regimen for B-cell lymphomas is immunochemotherapy (R-CHOP ≥70%), and CHOP for PTCL. Survival is similar to that reported by industrialized nations. We have no solid data on the results of treatment with salvage regimens nor stem cell transplantation in refractory/ relapsed NHL.

Conclusion

In Latin America, the same treatment regimens are used as in highly developed countries, although we lack the necessary technology to apply CAR T-cell therapies or a network of trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry.

Introduction

Lymphomas are divided into non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) and Hodgkin lymphomas (HL). They place fifth and sixteenth, respectively, in the ranking of non-gender associated neoplasms [Citation1]. The incidence and prevalence of lymphoproliferative entities vary by continent, country, and even individual communities and their respective lifestyles in a specific nation. An interesting example is reflected in Japanese individuals who move to another country, i.e. the United States, and the incidence of lymphoma appears to change after these individuals’ migration (Westernization phenomenon) [Citation2]. We have analyzed and submitted original information on the most frequent type of NHLs in Latin America.

On behalf of the International Lymphoma Project, Perry et al. evaluated 8 world regions (North America, Western Europe, Southeastern Europe, Central, and South America, North Africa, the Middle East, Southern Africa, and East Asia), and reported that B-cell NHLs are more common than PTCL [Citation3]. They also found that indolent NHL was more common in high-income countries than in low- and middle-income nations. Aggressive B-cell NHL, PTCL, and T/NK NHL were also more prevalent in low- and middle-income countries [Citation3].

To clearly define the economic characteristics of low-, low-middle, upper-middle, and high-income countries, their annual income must be known by the end of every fiscal year [Citation4]. Low-income economies refer to those with a per capita gross national income (GNI), calculated with the World Bank Atlas method, of $1045USD or less in 2020; lower-middle-income economies have a per capita GNI between $1046USD and $4095USD, upper-middle income economies report a per capita GNI between $4096USD and $12,695USD, and high-income economies have a per capita GNI of $12,696USD or above [Citation4]. The distribution of countries in the American continent according to their GNI and income level is shown in . Interestingly, most of the countries in the Americas are classified in the low-income bracket; only two countries (Belize and El Salvador) are considered low-middle income economies, while some Caribbean islands, the United States, Canada and, representing Latin America (LATAM), Chile and Uruguay are classified as high-income nations ().

Table 1. Countries distributed according to their annual income per person.

The importance of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the Americas

In 2020, the estimated incidence of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in the American continent was 525,425 new cases in patients over 15 years of age [Citation1]. It was more prevalent in males (55.65%) with a 5.6% difference in comparison with women (44.4%) [Citation1]. Notoriously, new NHL cases vary by income level. In (a), the highest incidence (∼45%) is observed in high- and upper-middle-income populations (∼35%) in comparison with low-middle (∼15%) and low-income (∼ 3%) nations. No significant differences between genders were observed. The 5-year prevalence of NHL cases in the Americas was 1,498,914 [Citation1]. As shown in (b), its prevalence was similar to that of nations in which high- and upper-middle-income groups predominate. The importance of evaluating the disease prevalence and incidence of NHL by income level hinges on the variable ability of each country to cover the expenses incurred by their NHL patients.

Figure 1. (a) Age-standardized rate of non-Hodgkin lymphoma incidence in 2020 according to annual income per person/country. (b) Age-standardized rate of non-Hodgkin lymphoma prevalence in 2020, according to annual income per person/country. Age range: ≥ 15 years in both (incidence and prevalence). Data Source: Globocan [Citation1] http://gco.iarc.fr/today.

![Figure 1. (a) Age-standardized rate of non-Hodgkin lymphoma incidence in 2020 according to annual income per person/country. (b) Age-standardized rate of non-Hodgkin lymphoma prevalence in 2020, according to annual income per person/country. Age range: ≥ 15 years in both (incidence and prevalence). Data Source: Globocan [Citation1] http://gco.iarc.fr/today.](/cms/asset/3340e5b8-6129-482a-9a2b-65ceb4b33fa2/yhem_a_2141960_f0001_ob.jpg)

The Hemato-Oncology Latin American (HOLA) study evaluated 5140 patients: 2967 (57.7%) had NHL, 1518 (29.5%) had multiple myeloma (MM), and 655 (12.7%) had chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) [Citation5]. Seven countries participated in this observational study: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Panama, and Guatemala [Citation5]. When we analyzed the NHL cases reported in this study, we observed that the most frequent subtypes were Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL, 49.1%), Follicular Lymphoma (FL, 19.5%), Mantle Lymphoma (MCL, 6.1%), and Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma (MALT, 2.8%) [Citation5]. Unfortunately, the authors did not report other types of incident lymphomas that are considered frequent in LATAM, such as PTCL, T/NK Lymphoma, and others. The epidemiological data is therefore biased given the absent NHL cases.

There is another report on the epidemiology of the types of NHL in Central and South America, in which Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Guatemala, and Peru participated [Citation6]. Laurini et al. reported that DLBCL (40%), FL (20.4%), MALT (6.9%), PTCL (6.8%), and T/NK-lymphoma (2.9%) were the most frequent subtypes in those countries [Citation6].

However, it is also noteworthy that information from other countries such as Ecuador, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Uruguay is unavailable, although they are part of the Latin American Continent.

This review will attempt to evaluate the different immunotherapy and chemotherapy regimens currently in use in the management of the three most common NHL subtypes in LATAM, based on the GELL data: DLBCL, FL, and PTCL-not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), and give information of the types of administered therapies, results, and survival in these three most frequent NHL subtypes.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

DLBCL is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma and is a clinically heterogeneous disease. The standard of care for DLBCL is immunochemotherapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP). For many years, investigators have sought an optimal treatment for DLBCL. The classic study by Fisher et al. compared Three Intensive Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced aggressive NHL versus CHOP as the standard of care [Citation7]. The trial registered 1138 patients and 899 were eligible, according to their inclusion criteria. The authors found no difference in Disease- Free Survival (DFS) and Overall Survival (OS) when comparing the following regimens: methotrexate, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone (m-BACOD); prednisone, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide, followed by cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, and methotrexate (ProMACE-CytaBOM); and methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin (MACOP-B) compared with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) [Citation7]. They concluded that CHOP remained the standard of care at the time since it was just as effective as the other tested regimens, and DFS and OS remained the same albeit with less evident toxicity. Subsequently, the French group led by Bertrand Coiffier showed that adding rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) to the CHOP regimen in the treatment of elderly DLBCL patients, proved superior to CHOP alone, improving OS by approximately 15% [Citation8]. Interestingly, this difference remained the same after a 10-year follow-up, which led to the extension of surveillance in this trial [Citation9]. However, R-CHOP was not only superior in elderly patients but also led to better results than CHOP. The MINT trial showed that in young patients, R-CHOP was the standard of care [Citation10]. However, when patients with DLBCL become refractory to treatment or develop an early relapse, the prognosis is dismal [Citation11,Citation12].

Thus, new drugs have begun to be tested in relapsed/refractory patients but they are only available in the USA, Europe, or Japan. Some examples include Anti-CD19 CAR T-cells, antibody-conjugated drugs (ADC: polatuzumab-vedotin, loncastuximab tesirine-lpyl, etc.), tafasitamab, and selinexor [Citation13]. Unfortunately, CAR T-cells are only available in the USA, European, and Japanese markets. In LATAM, Brazil (Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein) is in the process of creating a CART-cell program; As well as in Mexico (Hospital Universitario from Universidad Autónoma of Nuevo León) is working on an academic CART-cell program.

Normally ADC drugs must be administered with other drugs to synergize their activity because as single drug therapy, their action is moderate to poor. For example, polatuzumab-vedotin is accepted by some agencies in the Americas in combination with bendamustine and rituximab in relapsed / refractory DLBCL; Loncastuximab-tesirine is accepted by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA), European Medical Agency (EMA), and The Pharmaceuticals and Devices Agency (PMDA) in Japan. Loncastuximab-tesirine is not accepted by any health authority in Latin America yet.

How do we treat DLBCL in the Grupo de Estudio de Linfoproliferativos de América Latina (GELL)?

GELL represents a great number of countries and focuses specifically on each one. The represented countries are Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Honduras joined the group a few weeks ago.

All of these countries shared their databases and the types of treatment they administered to their patients were analyzed. Except for the National Cancer Institute of Guatemala, most countries treated their patients with rituximab plus CHOP (R-CHOP); Guatemala reported that in their public health system, it is difficult to obtain rituximab, so they only administer ∼15% treatment with monoclonal anti-CD20 antibodies to their patients.

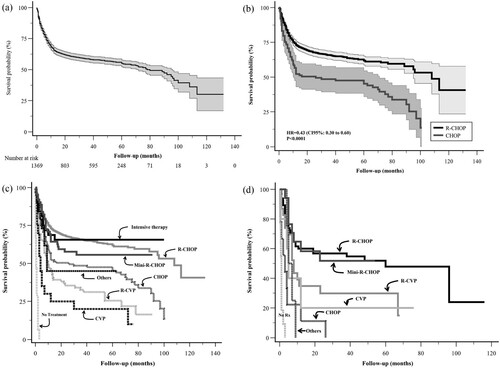

The databases were concentrated into a single one and the most frequently administered were analyzed as a Real-World Study (RWS). With a median follow-up of 33 months (range: 0–145 months), a total of 1375 DLCBCL cases were collected between 2006 and 2017; only 1369 were analyzed because 6 patients lacked complete data. We detected that 997 subjects were treated with R-CHOP (72.5%); 113 received CHOP (8.2%); 62 received R-mini-CHOP (4.5%); 32 received an intensive continuous infusion regimen (2.3%) with adjusted dose R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin), Hyper-CVAD (High doses cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone), R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, platinum-derived drugs), R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), 84 received R-CVP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone) (6.1%), 20 received CVP (1.45%), and 20 received other regimens such as R-bendamustine, R-high-dose methotrexate, radiotherapy alone, rituximab monotherapy (1.45%), but 41 (3%) subjects received no treatment at all due, in the first place, to poor functional status; second, as a result of their inability to pay for treatment, and third, if a serious infection was detected at diagnosis, treatment was delayed. (a) shows the OS of the entire cohort and the median OS was 56% at 5 years. (b) reveals that adding rituximab to CHOP has improved overall survival, with a 57% decrease in relative mortality (hazards ratio, 0.43; p < 0.0001); a similar outcome had been reported by the French group in a prospective trial [Citation8,Citation9], and by the British Columbia Group that in a retrospective analysis, both obtained a similar hazards ratio of 0.40 [Citation14]. (c) shows that the OS curves improve with the use of R-CHOP and intensive continuous infusion regimens, both appearing to be superior to the previously mentioned regimens. Nonetheless, the overall survival curve in the R-mini-CHOP group was the third best, with even superior results than in the CHOP group. We analyzed the R-CHOP group versus the other treatment regimens and found that R-CHOP vs. CHOP, vs. R-CVP, vs. CVP yielded statistical differences in terms of the calculated hazards ratio (). When compared with intensive continuous infusion regimens, Mini R-CHOP and others revealed no notable differences (). When treating very elderly patients (>80 years), one might suppose that avoiding treatment with anthracyclines would be beneficial, but our LATAM data revealed that treating very elderly patients with anthracyclines improved PFS and OS without associated high toxicity [Citation15,Citation16]. In our database of 1369 DLBCL cases, 134 patients aged 80 years or above (∼10% database) were registered. None received intensive continuous infusion chemotherapy. (d) shows how those treated with R-CHOP or R-mini-CHOP had better OS at 36 months (56.8% vs. 51.8%, respectively; p = N.S.). Thus, the use of anthracycline-based regimens at full-dose or at 50% doses might be effective in the very elderly, but 50% doses may be less toxic.

Figure 2. The overall survival (OS) Kaplan-Meier curve. (a) OS curve of 1369 patients with DLBCL, median 5-year OS survival: 56%. (b) OS comparing R-CHOP vs. CHOP (60% vs. 48%, respectively; p < 0.0001). (c) OS comparing all the different regimens: R-CHOP (n = 997), 60% OS at 5 years. Intensive Therapy (n = 32) (R-EPOCH, R-Hyper-CVAD, R-DHAP, R-ICE as first line treatment), 63% OS at 5 years. R-mini-CHOP (n = 62), 55% OS at 5 years. CHOP (n = 113), 48% OS at 5 years. Others (n = 20) (R-Bendamustine, R-High-Dose Methotrexate, radiotherapy alone, rituximab alone), 45% OS at 5 years. R-CVP (n = 84), 25% OS at 5 years. CVP (n = 20), 14% OS at 5 years. No treatment (n = 41), 0% OS at 5 years. (d) OS survival in very elderly patients (≥80 years old) based on different regimens: R-CHOP (n = 65), 56% OS at 3 years. R-mini-CHOP (n = 17), 52% OS at 3 years. R-CVP (n = 23), 30% OS at 3 years. CVP (n = 5), 20% OS at 3 years. CHOP (n = 9), 0% OS at 3 years. Others (n = 4) (R-bendamustine, radiotherapy alone and rituximab alone), 0% OS at 3 years. No treatment (n = 11), 0% OS at 3 years. Notes: R, rituximab; CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; EPOCH: Etoposide, vincristine, and doxorubicin in continuous 24 hr. infusion of cyclophosphamide one day and prednisone 5 days, all adjusted according to the absolute neutrophil count before each cycle. Hyper-CVAD: high-dose doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone. DHAP: dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, platinum-based drug. ICE: ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide. CVP: cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone. R-mini-CHOP: 50% decrease in cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin doses.

Table 2. Comparison of Cox hazards ratio between the different treatment regimens in the DLBCL cohort.

When we analyzed salvage regimens in GELL, relapsed /refractory patients (45%), we observed that three regimens were most frequently administered: R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide), R-DHAP (high-dose cytarabine, dexamethasone, and a platinum-derived drug), and R-ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin), all in very similar percentages (unpublished data). These patients’ outcomes were complete remission (CR) 35%, partial remission (PR) 15%, and treatment failure 50%. Less than 16% of patients were consolidated with autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) (unpublished data). LATAM is currently conducting some of the clinical trials studying this subtype of lymphoma and comparing results with other countries such as the USA, Europe, and Japan.

Follicular lymphoma (FL)

Follicular lymphoma is the second most common subtype of lymphoproliferative disorder, accounting for 35% of NHL, and approximately 70% of indolent NHL in western countries [Citation17]. However, data on FL in the LATAM databases are scarce. Thus, our colleague Torre-Viera et al. led and presented our preliminary data of 763 patients with FL [Citation18]. Over half of patients were above the age of 60, the disease was slightly more frequent in women, almost a third had extranodal involvement, and almost 70% were diagnosed in advanced stages. According to the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI), 56% were in the intermediate and high-risk groups. With the FLIPI-2 that evaluates PFS, we established that the intermediate and high-risk groups accounted for 81% of cases.

In terms of FL therapy, we must analyze the initiation of first-line treatment. The question remains: should we follow the current ‘watch and wait’ paradigm in patients with advanced disease but that remain asymptomatic? This is a very relevant point in LATAM countries due to the necessary expenses required to obtain immunotherapeutic options. For many years, it appeared that the median survival of patients with low-grade FL was approximately 10 years and that it might not be greatly modified by therapy [Citation19,Citation20].

We must emphasize that FL is far more complex than previously thought, especially in terms of morphology (large cell clusters, FL degrees), and microenvironment, among other features. The Nebraska Lymphoma Study reported that survival improved significantly after the year 2000 when rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) was introduced to the market [Citation21]. Nonetheless, FL remains incurable to date, so a ‘watch and wait’ approach in asymptomatic patients appears to be a good strategy in countries where resources are scarce, while also preventing early toxicity in these cases. Our group (GELL) observed that our colleagues initiate immediate treatment (median treatment initiation: 0.08 years, 95% CI 0.08–0.09), and 88% of patients began therapy within 1 year of diagnosis [Citation18]. We have no explanation for this, but we believe that it is multifactorial and that it would be most relevant to study this approach in LATAM. Perhaps, three factors influence this decision: advanced stages at diagnosis, delayed access to specialized cancer care in our region which increases the patients’ burden of disease, and the patient's wish to initiate timely treatment despite clear explanations of the ‘watch and wait’ approach.

In our FL database, we have 647 agreements (of 763) on the type of regimen selected: 70% received CHOP ± rituximab (R), 16% CVP ± R, 6% bendamustine ± R, 4% R only, and 4% were administered other treatments (R-fludarabine + mitoxantrone; only CHOP; only CVP).

The randomized, open-label PRIMA (Primary RItuximab and Maintenance) study was conducted in 223 centers in 25 countries, and the main induction regimen in FL was R-CHOP in 73% of cases, followed by R-CVP (∼23%), and R-FCM (∼4%) [Citation22]. This reflects a global preference for R-CHOP over other regimens.

Response data were available in 628 patients whereby 72% had a complete response, 21% had a partial response, and 7% had no response, for an overall response rate of 93%. In most cases, our evaluations were based on clinical findings, and laboratory and imaging studies; few patients underwent PET/CT imaging, since its use was restricted.

Interestingly, when we evaluated prognostic scores such as POD24 (Progression of Disease before 24 months), our cohort showed a POD24 score of 12% (median OS at 7.3 years, 95% CI 4.8-not reached), while in the study in which this biomarker was suggested by Casulo et al, it was 19% [Citation23]. The POD24 was designed based on the most frequently used regimen, R-CHOP, so the POD24 may be slightly lower in our cohort than in Casulo’s original study, and this is also reflected in PFS and OS (10.5 years, 95% CI 7.3-not reached; 21.1 years, 95% CI 13-not reached; respectively) [Citation18]. However, we still lack information on the use of rituximab as maintenance treatment of FL but expect to soon present our data.

We also lack information on patients with relapsed or refractory FL, and we are currently analyzing this specific sub-group. Again, some clinical trials are beginning to evaluate patients with FL in LATAM, but they remain insufficient.

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS)

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is a very heterogeneous disease and accounts for approximately 15% of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases in the world. PTCL is divided into several subtypes, and PTCL-NOS is the most frequent, representing 26% of all PTCL cases [Citation24]. In Mexico, Hernández-Ruiz et al published data on NHL and reported that 6.3% of total cases were PTCL-NOS [Citation25], a very similar percentage to that reported by Laurini et al. in Central and South America [Citation6]. The RWS obtained by GELL showed a total of 200 patients with a diagnosis of PTCL-NOS. Fifty percent of patients were ≥60 years, 57% were male, 50% had an ECOG ≥2, 40% had elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, 37% had bone marrow involvement, > 60% were diagnosed in advanced stages (Stage III/IV), and had developed B symptoms (sweats, weight loss, nocturnal diaphoresis). When divided into risk groups, we observed that The International Prognostic Index (IPI) score was high-intermediate and high in 47% of cases. The Prognostic Index in the PTCL-U (PIT) risk score was high-intermediate and high in 58% of cases.

The GELL group treated these patients with CHOP/ CHOP-like (60%), CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, prednisone; 20%), and the remaining cases received CVP (15%) or other less common regimens (5%) (unpublished data). The treatment offered to GELL patients, which may be an X-ray of the LATAM approach, was similar in other groups [Citation26].

The outcome remains dire, with a median OS of the entire cohort of 0.83 years (95% CI 0.58–1.75) and a 5-year OS rate of 31% (95% CI 23–40%). Multivariate analysis found that serum albumin <3.5 g/dL (HR 1.83, 95% CI 1.10–3.05; p = 0.02) and ECOG ≥2 (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.15–3.30; p = 0,01) were associated with worse OS; these results were published as an abstract at a recent ASH meeting [Citation27]. In general, our data are similar to those obtained by other large groups such as the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project which reported a 5-year OS of 32%. They also reported that only bulky disease >10 cm was a predictor of survival, with a multivariate analysis hazards ratio (HR) of 2.1 for OS (p = 0.019) [Citation28].

We have no information on salvage treatment in refractory / relapsed patients nor on consolidation with ASCT or allogeneic stem cell transplantation. The leaders are analyzing this data.

Conclusion

Three of the most common lymphomas in each of the NHL subtypes were analyzed. The therapeutic approach to the management of DLBCL is the same as that used by other groups in the USA and Europe. First-line treatments are the same as in the rest of the world that has access to rituximab. The Guatemala group in the GELL reported results obtained in a public hospital, where access to rituximab is scarce. OS is likewise, similar to that reported throughout the world, approximately 60% at 5 years and 40% at 10 years.

The characteristics of FL are also similar to those reported by other groups. The treatment we use for induction is R-CHOP, while the Europeans use fludarabine-based regimens. Curiously, our group initiates treatment immediately after diagnosis, and we rarely follow the ‘watch and wait’ approach. We must rethink this policy and delve into the causes that have led to immediate treatment initiation, to modify this modality. In the PTLC-NOS group, our collected data on its general characteristics are the same as in other multicenter groups (T-Cell Project), and our results with anthracycline-based regimens are practically the same in terms of 5-year OS.

The GELL is beginning to become consolidated and we are building our retrospective databases; however, we have also begun to develop a prospective patient platform that will include their clinical characteristics, laboratory and imaging results (in some cases with a higher percentage of PET/CT images), and their immunohistochemistry and molecular features. We have established an alliance with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and Dr. Luis Malpica (Peruvian), who will be our link between LATAM and that institution. The project has been named Epidemiology of Lymphomas in Latin America (ELLA).

Finally, we are most grateful to our patients and their families, and to all the GELL member countries, since without them, this group would be untenable and further research on the intricacies of these diseases that affect all LATAM would not be possible.

Acknowledgements

GELL: Argentina. Nancy Cristaldo, Lorena Fiad (Hospital Italiano La Plata); Victoria Otero (Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires). Bolivia. Rosio Baena (Hospital Los Olivos de Cochabamba): Juan Choque (Hospital de la caja nacional de salud, La Paz). Brazil. Guillherme Perini (Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein). Chile. Camila Peña (Hospital del Salvador); Pilar León (Hospital Carlos Van Buren. Concón). Colombia. Henry Idrobo (Universidad del Valle); Juan Ospina, Rolando Martínez (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología de Colombia); Iván Perdomo (Clínica Los Nogales). Cuba. Rosa Ríos-Jiménez (Hospital Clínico Quirúrgico Hermanos Ameijeiras). Ecuador. Marco Di Stefano (Universidad San Francisco de Quito). Guatemala. Fabiola Valvert (Instituto Nacional de Cancerologia de Guatemala). Mexico. Melani Otañez (Hospital General del Estado, Hermosillo), Perla Colunga (Hospital Universitario de UANL), Myrna Candelaria (Instituto Nacional de Cancerología), Ana Florencia Ramírez-Ibargüen (Hospital Centenario Miguel Hidalgo). José Ascención Hernández (Tecnológico de Monterrey), David Gómez-Almaguer (Hospital Universitario de UANL); Guillermo Ruiz-Argüelles (Clínica Ruiz de Puebla), Fernando Pérez-Jacobo (Hospital PEMEX Norte), Luis Villela (Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa-Facultad de Medicina, Hospital Fernando Ocaranza-ISSSTE, Centro Médico Dr. Ignacio Chávez ISSSTESON, Hermosillo). Paraguay. Lidiane Andino, Alana Von Glassenap, Cristobal Frutos (Hospital Central del Instituto de Previsión Social en HCIPS). Peru. Denisse Castro, Sally Paredes, Thanya Katherine Runciman-Gozzer, Brady Beltrán (Hospital Nacional Edgardo Rebagliati Martins); Anais Camara (Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Neoplásicas). Uruguay. Carolina Oliver (Hospital Británico de Montevideo y CASMU). Venezuela. María Alejandra Torres-Viera (Universidad Central de Venezuela). External Partners: Luis Malpica-Castillo, MD. Department of Lymphoma – Myeloma, Division of Cancer Medicine, MD Anderson Cancer Center. Jorge Castillo, MD. Clinical Director, Bing Center for Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luis Villela

Luis Villela is Medical Doctor graduated at Universidad La Salle, American British Cowdray Hospital, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico. Studied Hematology at Hospital Clinic de Barcelona, Universidad de Barcelona and Bone Marrow Transplantation at Hospital Satnta Creu I Sant Pau, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona. He is Hematologist in Hospital Fernando Ocaranza of ISSSTE and Head of Blood Bank at Centro Medico Dr. Ignacio Chavez of ISSSTESON and Leader of Grupo Mexicano para el Estudio del Linfoma, Founder Member of GELL, Chief Editor Revista Mexicana de Hematologia. He published 48 papers published in national and international peer-review journals, 77 abstracts in national and international meetings, 10 chapters book related to hematology. He is Reviewer of different international journals and Part of de council research of Mexico (Sistema Nacional de investigadores Level 2). Citations index: 621, H-index: 11, iH-Index 13.

María Torre-Viera

María Torre-Viera is Medical Doctor graduated at Central University of Venezuela in Internal Medicine in the Hospital Del oeste Caracas, Venezuela. Hematology Specialist, UCV with Sub-specialization in Lymphomas at the Institute of Oncology and Hematology. She is Medical Director at the Hematology Oncology 360 Oncology Day Hospital in Caracas Venezuela, Private outpatient chemotherapy center, handling an average of 1500 patients a year. She is Head of the National Lymphoma Committee in Venezuela. Participate in more than 68 papers communicated and/or published nationally and internationally. She participated in chapters for 8 hematology-oncology books. She spent 10 years as editor-in-chief of the magazine HEMOS, (informative organ of the SVH). Maria is Vice President of Latin American Lymphoproliferative Study Group (GELL), Active member of Venezuelan Hematology Society, the European Hematology Association, International Myeloma Foundation (IMF), International Society Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Master in clinical and oncological nutrition, Valencia University. Actual member for the COVID 19 Special Venezuelan Committee.

Henry Idrobo-Quintero

Henry Idrobo-Quintero, Internist, Hematologist and Clinical Oncologist, trained at the Universidad Libre Seccional Cali thanks to multiple scholarships received throughout his training. Professor at the Universidad del Valle, one of the best universities in the country, since 2011 and now Coordinator of Hematology and Clinical Oncology of this University. Member of the Board of Directors and Scientific Committee of the Colombian Association of Internal Medicine ACMI since 2011, and the same positions in the Colombian Association of Hematology and Oncology ACHO, since 2019. Focus of interest on Lymphoproliferative Disorders, currently being also a Board Member and of the Scientific Committee of the Latin American Study Group for Lymphoproliferative GELL and within the ACHO shares the coordination of the Lymphomas area in the National Scientific Committee. Professionally, his performance is as National Scientific Director of Hematology-Oncology of the National Institute of Oncology of the Ospedale Guorp SAS (INOOS), and also providing services for the San Jorge University Hospital, Oncologists of the West, San Rafael Clinic, Julián Coronel Medical Center, leading in this last Research Center in the area of Hematology-Oncology. The short-term purpose is to consolidate Latin American research products and the region's participation in international studies.

Brady E. Beltran

Brady E. Beltran is 50 years old. He was born in Arequipa, Peru. He studied medicine in San Agustin University from Arequipa (1989–1997). He studied a speciality in Medical Oncology in Edgardo Rebagliati Martins (1998–2001). He has the following grades: master’s in molecular biology in cancer (2006–2008). Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas CNIO. Madrid, Spain. Master in Medicine (2017–2018) San Martin de Porras University. He has the following positions: Medical oncology assistant in Oncology–Radiotherapy department in Edgardo Rebagliati hospital, Lima, Perú (2002–until now). Currently is: Chief of Lymphoma Unit of Oncology–Radiotherapy department in Edgardo Rebagliati hospital, Lima, Perú (2008–until now). Chief of Service of Medical Oncology – Edgardo Rebagliati Martins, Lima, Peru 2020 until now. President of GELL. Publications: He is author of more than 100 publications in indexed journals, abstracts and posters. He is a recognized investigator that has a category Carlos Medrano II according Concytec. He has H index 17. He is winner of different research awards (Kaelin award 2004, 2018, 2020).

References

- Globocan. Data source from international agency for research on cancer. 2020. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr.

- Chihara D, Ito H, Matsuda T, et al. Differences in incidence and trends of haematological malignancies in Japan and the United States. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:536–45.

- Perry AM, Jacque D, Nathwani BN, et al. Classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in seven geographic regions around the world: review of 4539 cases from the International non-Hodgkin lymphoma classification project, ASH abst#1484. Blood. 2015;126:1484 (abstr).

- World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- Tietsche de Moraes Hungria V, Chiattone C, Pavlovsky M, et al. Epidemiology of hematologic malignancies in real-world settings: findings from the Hemato-Oncology Latin America observational registry study. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–19.

- Laurini JA, Perry AM, Boilesen E, et al. Classification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Central and South America: a review of 1028 cases. Blood. 2012;120:4795–801.

- Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(14):1002–6.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–42.

- Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste E, et al. Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5 trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 2010 Sep 23;116(12):2040–5.

- Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial by the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:379–91.

- Villela L, López-Guillermo A, Montoto S, et al. Prognostic features, and outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who do not achieve a complete response to first-line regimens. Cancer. 2001;91:1557–1562.

- Rovira J, Valera A, Colomo L, et al. Prognosis of patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma not reaching complete response or relapsing after frontline chemotherapy or immunochemotherapy. Ann Hematol. 2015;94:803–812.

- Cheson BD, Nowakowski G, Salles G. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: new targets and novel therapies. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:68–78.

- Sehn LH, Donaldson J, Chhanabhai M, et al. Introduction of combined CHOP plus rituximab therapy dramatically improved outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in British Columbia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5027–5033.

- Asklid A, Eketorp Sylvan S, Mattsson A, et al. A real-world study of first-line therapy in 280 consecutive Swedish patients ≥80 years with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: very elderly (≥85 years) do well on curative intended therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020 Sep;61(9):2136–2144.

- Sonnevi K, Wästerlid T, Melén CM, et al. Survival of very elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma according to treatment intensity in the immunochemotherapy era: a Swedish Lymphoma Register study. Br J Haematol. 2021 Jan;192(1):75–81.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016 May 19;127(20):2375–90.

- Torres-Viera M, Beltran B, Villela L, et al. Follicular Lymphoma in Latin America: real-world experience from 763 patients. Blood. 2020;136(Supplement 1):12–13.

- Johnson PW, Rohatiner AZ, Whelan JS, et al. Patterns of survival in patients with recurrent follicular lymphoma: a 20-year study from a single center. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:140–147.

- Brandt L, Kimby E, Nygren P, et al. A systematic overview of chemotherapy effects in indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Acta Oncol. 2001;40:213–23.

- Armitage JO, Longo DL. Is watch and wait still acceptable for patients with low-grade follicular lymphoma? Blood. 2016;127:2804–2808.

- Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:42–51.

- Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early relapse of follicular lymphoma after rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone defines patients at high risk for death: an analysis from the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2516–22. Erratum in: J Clin Oncol. 2016; 34:1430.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008.

- Hernandez-Ruiz E, Alvarado-Ibarra M, Juan Lien-Chang LE, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in Mexico. World J Oncol. 2021;12:28–33.

- Schmitz N, de Leval L. How I manage peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: current practice and a glimpse into the future. Br J Haematol. 2017;176:851–866.

- Idrobo H, Beltrán BE, Villela L, et al. Serum albumin is an independent factor predicting survival in patients with peripheral T cell lymphoma: a multi-institutional study from the Latin American working group for lymphomas (GELL). Blood. 2019;134(Supplement_1):4047.

- Weisenburger DD, Savage KJ, Harris NL, et al. Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: a report of 340 cases from the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. Blood. 2011;117:3402–3408.