ABSTRACT

Purpose

: A primary breast lymphomais a rare form of extranodal lymphoma type. We aimed to analyze prognosticriskfactors and explore relapse factors in primary breast diffuse large B cell lymphoma (PB-DLBCL).

Methods

: From November 2003 to September 2020, sixty-three patients from two medical centers newly diagnosed with PB-DLBCL patients were analyzed retrospectively.

Results

: The median age was 52, and >50% of patients were post-menopausal. The international prognostics index (IPI) (0–1) was mainlyin the low-risk group (84%), and there were four patients with stage IV (6%) who had bilateral breast involvement. With a median follow-up time of 4.92 years (3.17–8.00), five-year overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were 78.9% and 67.1%, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and B symptoms were independent adverse prognostic risk factors for OS, whereas bilateral breast involvement was unfavorable for PFS. Disease recurrence and relapse occurred in 40% (25/63) patients, mainly in the breast, followed by the central nervous system (CNS) and skin/soft tissue.

Conclusion

: This is the first study to explore the prognostic risk factors and relapse factorsof PB-DLBCL in a relatively large Chinese PBL cohort. Local breast and CNS recurrence after standard R-CHOP treatment were the main issues we are facing now.

Introduction

Primary breast lymphoma (PBL) is a rare breast malignancy entity comprising 0.5% of breast malignancies, 1% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 2% of extranodal lymphomas[Citation1]. From 1975 to 2017, the overall incidence of PBL was 1.35/1,000,000 (based on the 2000 USA population scaling), showing a significant upward trend, with an annual percentage change of 2.91%[Citation2].

In 1972, Wiseman and Liao[Citation3] first defined PBL according to the following four criteria, which is the current standard definition: 1. The first pathogenic site was the breast, and the lymphoma tissue was adjacent to the anatomical structure of the breast; 2. There was no history of lymphoma orno extensive disease spread; 3. Only regional lymph nodes were involved (ipsilateral axillary and supraclavicular lymph nodes); and 4. Sufficient histological specimens were available for pathological confirmation. These criteria were too stringent to exclude diseases involving distant regional lymph nodes and other extranodal organs, and there have been no large-scale trials or studies verifying the mechanism. Usually, only patients with stage IE–IIE were included. Patients with bilateral involvement were classified as either stage II or IV. Thus, studies have confirmed that PBL has a better prognosis than secondary breast lymphoma (SBL)[Citation4].

PBL usually begins with a painless breast mass and is diagnosed usinga needle or excision biopsy. Sometimes it can be misdiagnosed as breast cancer, and a modified radical mastectomy or mammectomy isperformed to confirm the appropriate diagnosis. It is challenging to differentiate PBL from breast cancer using imaging examinations test. The primary pathological lymphoma type is diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), accounting for 60–80% of the cases, among which non-germinal center B cell (GCB) accounts for the majority of patients [Citation5]. It has also been reported that the most common type is follicular lymphoma (FL) or marginal zone lymphoma (MZL)[Citation6, Citation7].

In terms of treatment, surgery does not benefit these patients[Citation8]. Small-scale retrospective studies have shown no statistical difference in survival between patients who received rituximab and those who did not[Citation9–11]. Treatment with radiotherapy has a clear benefit in patients with stage I and II cancers. Local (lateral and contralateral) breast and central nervous system (CNS) recurrence are severe problems faced by these patients, and approximately 20–40% experience relapse or progression[Citation6, Citation12–17].

There is no consensus on the treatment and prognosis of PBL because of the minimal number of patients and lack of large-scale randomized controlled clinical trials. Currently, the first-line therapy for primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, prednisone) immunochemotherapy. Furthermore, there are few retrospective studies on PBL > 50 cases in China, and the clinical manifestations, pathological features, and prognostic risk factors of PBLrequire further clarification.

We conducted a multicenter, relatively large retrospective study to identify the clinical features and prognostic risk factors in a Chinese PBL cohort.

Methods

Participant selection

We retrospectively included patients diagnosed with lymphoma with breast involvement and patients who had completed at least one cycle of systemic treatment between November 2004 and October 2020 at two centers (Peking University Cancer Hospital & Institute and Peking University International Hospital). Secondary breast lymphoma was excluded, involving distant lymph nodes in non-breast drainage areas or distant organs based on the definition of PBL. Finally, 63 PB-DLBCL patients were included according to the current standard definition. The pathological diagnosis was by the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria in different periods(Version 2001, 2008,and 2016)[Citation18]performedby the pathology department of our hospital. The staging criteria were as follows: stage I, unilateral breast involvement; stage II, unilateral breast involvement with regional lymph node involvement; and stage IV, bilateral breast involvement with or without regional lymph node involvement.

All procedures involving humans followed the ethical standards of the institution and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki, including subsequent amendments or similar ethical standards. All patients signed an informed consent when they were first hospitalized at our center.

Variables and procedures for each primary and secondary objective

Demographic characteristics, pathological diagnostic information, laboratory test results, and survival and recurrence information were retrospectively collected, and followed-up using outpatient and inpatient information or over the telephone.

The cell of origin (COO) was confirmed using the Hans algorithm[Citation19]. Double expression lymphoma (DEL) was defined as BCL-2 expression of >50% and C-MYC of >40% according to immune his to chemistry (IHC), based on the WHO 2016 classification. Double-hit lymphoma (DHL) was defined as MYC and BCL2/BCL6 rearrangement according to fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH). Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of diagnosis to death by any causes, or the date of the last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from diagnosis until the first progression or last follow-up date. Progression or relapse was evaluated using computed tomography (CT) or positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). The Ches on criteria were used for data before 2014, and the Lugano criteria wereused for post-2014 data.

Analytic methods

IBM SPSS Statistics (V24.0, IBM Corp) and R (Version 4.1.2) were used to analyze the data. P-values were all tested by bilateral tests, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for data measurement, and Fisher's exact probability method or chi-squared test was performed for data analyses. Survival time was calculated in months, and the Kaplan–Meier method was used to compare survival differences among groups. Survival curves were generated and the log-rank test was used for comparison. Univariate and multivariate regression analyses were performed usingthe Cox regression model, and data with P < 0.05 were included in the multivariate analysis.

Results

Patient recruitment and characteristics

Sixty-three patients with primary-breast diffuse large B cell lymphoma (PB-DLBCL) were included in this study(). The median age of the patients was 52 years old (25-85 years). Thirty-six (57%) women patients experienced disease onset after menopause. Four patients had a previous history of breast cancer, and four had bilateral and stage IV disease (6%). Non-GCB and GCB occurred in 37/52 (73%) and 14/52 (28%) patients, respectively,based on complete IHC. MYC, BCL-2, and BCL-6 expression swere confirmed in 31 patients. DEL occurred in 13 (42%) patients, and only one patient had DHL, as demonstrated by FISH. Forty-three(84%) patients were at low risk (IPI 0–1),and 12 patients had the bulky disease (>5 cm).

Table 1. Clinical charactar of all 63 female PB-DLBCL.

Treatment and efficacy

Sixty-one (96.8%) patients had completed more than four cycles of R-CHOP or CHOP induction therapy, of which 50 (83.3%) had beentreated with rituximab (Table S1). Of the 13 patients who did not receive rituximab, ten were diagnosed with DLBCL before 2010 and not use rituximab because of its high cost in China at the time. Most patients (83%, n = 52) had completed CNS prophylaxis (50 had received intrathecal injection of cytarabine, methotrexate, and dexamethasone;and two had received intravenous high-dose methotrexate[HD-MTX]). Some patients had declined prophylaxis because of advanced age, lumbar disease, or other reasons. Only 12 patients (19%) receivedlocal radiation therapy (RT). Among the 61 patients who completed ≥ 4 cycles of frontline containing CHOP regimen treatment, only one (1.7%) had stable disease (SD), and four (6.9%)had progressive disease(PD), with the remaining patients having complete remission(CR)(76%) or partial remission(PR)(16%).

Survival analysis

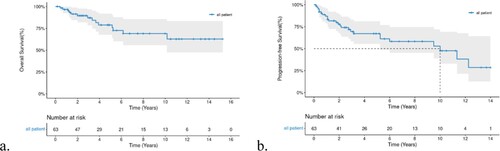

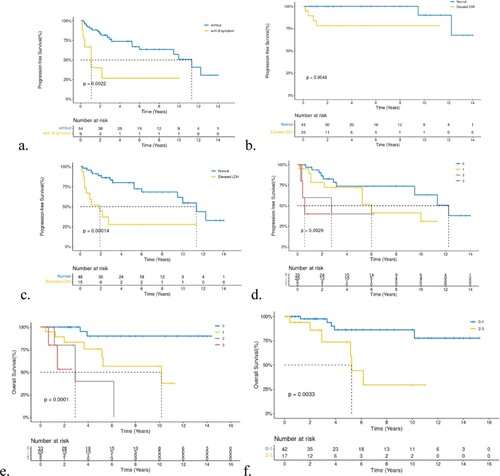

The 5-year PFS and OS of all patients were 67.1% (95%-Confidence Interval(CI) 55.4–81.1) and 78.87% (95%-CI 67.7–91.9), respectively; the median OS was not reached, and the median PFS was 120 months (a,b).

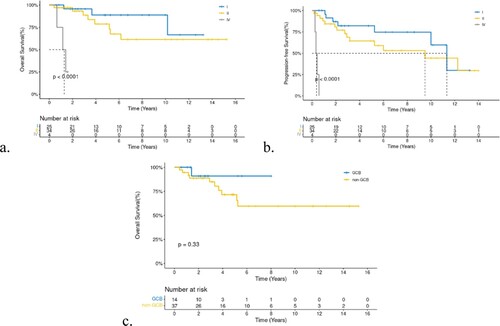

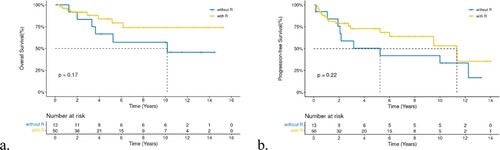

All 63 patients with PB-DLBCL were included in the survival analysis. Age and menopausal status did not affect OS and PFS. Surgery also had no positive influence on survival, regardless of the surgical procedure performed. Bilateral-involved (stage IV) patients had extremely worse six-month PFS(25%) and one-year OS(75%)than unilateral patients, who had a six-month PFS of 96.58% and one-year OS of 96.39% (a,b). While lesions on the left or right breast did not affect prognosis, the P-values of OS and PFS between left and right breast lesions were 0.64 and 0.85, respectively. Although we did not identify a statistical difference between bulky disease and cell of origin (COO), we found that patients with bulky-disease had unfavorable five-year OS and PFS rates of 59.3 and 45.7%, respectively, compared with 84.35 and 72.55%, respectively, in patients withthe non-bulky disease. In addition, patients with non-GCB had a worse five-year OS(71.5%)thanGCB(90.91%) (P = 0.33, c). Other factors such as elevated erythrocyte sedimentation (ESR),elevatedlactic dehydrogenase (LDH), and B symptoms,were all unfavorable prognosis factors for OS and PFS with a significant statistical difference (P < 0.001). Five-year OS and PFS of patients with B symptoms, elevated ESR, and elevated LDHwas25.4, 47, and 30.7%, and 26.67, 39.4, and 27.8%, respectively. Log-rank test revealed that all P-values were <0.005 for OS or PFS for the above-mentioned three unfavorable factors (B symptom, elevated ESR, elevated LDH,and high IPI, a-c). Furthermore, we found a significant survival difference between the different IPI score groups (d,e). Because most included patients had stage I-II disease, we also performed survival analyses according to stage-adjusted IPI (f). Forty-two patients were in the adjusted IPI 0–1 group, which had a better five-year OS than the IPI 2–3 group (86.2% vs 73.7%,p = 0.0033).

Figure 3. a-d,Kaplan-Meier curve of B symptom, ESR, LDH, and IPI in PFS, e. IPI and stage adjusted-IPI of OS.

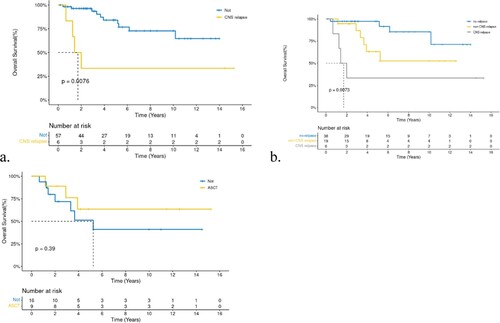

Although rituximab did not impact on OS(a), we found that the 5-year PFS of the 48 patients who had received rituximab was better than those who did not (72.81 vs. 50.3%, P = 0.22, b). RT did not have a positive effect, as expected. Furthermore, relapse/refractory(R/R) patients had short survival periods. However, we found that patients with CNS relapse had concise short survival times compared with all other patients (a,both recurrence at different sites and non-recurrence). The median survival time was 1.71 years with a two-year OS of 33.3%, while other patients had a two-year OS of 63.2% for non-CNS relapse patients and97.3% for non-relapsed patients (P = 0.0073, b). High-dose chemotherapy treatment and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HDT/ASCT) was the standard treatment for R/R DBLCL patients, with a five-year OS rate of 63.5% in R/R patientsand 51.3% in those without ASCT (p = 0.39, c).

Recurrence and relapse

Among the 63 patients with PB-DLBCLstudied, 25 patients experienced disease progression, the sites of recurrence and progression are listed in . Four patients had primary refractory disease. In the remaining 21 patients, the median time to disease progression was 26 months (range, 3–147 months). Six patients had CNS relapse, including four parenchymal lesions diagnosed by enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and two meningeal lesions diagnosed by cerebrospinal fluid testsand clinical symptoms. Two patients had brain parenchymal relapse after ten years, which was confirmed as DLBCL by re-biopsy(Table S1).

Among the baseline characteristics of patients with recurrent progression (Table S2), there were more patients with bilateral involvement; elevated ESR, and LDH levels, without rituximab use, and worse efficacy (SD or PD), with statistically significant differences between patients who relapsed and those who did not (P < 0.05). All four patients with bilateral disease progressed or regressed. Among the patients with recurrence, 10 (40%) did not receive rituximab Table S2.

Table 2. Summarize of 25 relapse/progression patients.

Cox analysis

Clinical variables associated with OS and PFS were analyzed using univariate and multivariate Cox analyses (). Univariate Cox analysis showed that bilateral disease (hazard ratio[HR] = 28.35), B symptoms (HR = 7.53), elevated ESR (HR = 9.79), elevated LDHlevel (HR = 6.18), relapse/progression (HR = 4.07), CNS relapse (HR = 4.34), and IPI 2–3(HR = 7.94) were unfavorable factors for OS (P < 0.05), where bilateral disease (HR = 51.66), B symptoms (HR = 3.97), elevated ESR (HR = 3.82), elevated LDH level (HR = 4.52), and IPI 2–3 (HR = 4.1) had a significant unfavorable effect on PFS(P < 0.05). Multivariate analysis found that B symptoms (HR = 6.89, 95% CI 1.54-30.85) and elevated ESR (HR = 6, 95% CI 1.17–30.88) were independent adverse prognostic factors for OS, whereasbilateral breast involvement (HR = 23.54, 95% CI 2.5-221.47) was unfavorable for PFS.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate analysis of OS and PFS.

Discussion

Although PBL is a rare entity, further studies are still necessary because of the specificity of its onset site, stage, treatment, and high risk of recurrence. The median age of onset was 52 years old in patients in the present study, while that in the Western population is approximately 60 years old. The beginning of PBL in Asian individuals is earlier[Citation5, Citation20]. The strict definition of PBL focused on early-stage disease and low-risk groups, which was supported by our study, in which 89% of patients had stage I–II disease and 84% had IPI scores of 0–1. However, with stage-adjusted IPI, patients with local lymphnode involvement had worse overall survival. Six-month PFS of patients with bilateral lesions was 25%, and four patients with bilateral breast involvement progressed. Thus, it confirmedmore appropriately to classify these patients as stage IV. Multivariate studiesalso showed that bilateral lesions were an independent prognostic risk factor of PFS.

The five-year PFSand OS of patients with PB-DLBCLwere 67.1% and 78.87%, respectively, per those reported in the literature[Citation2, Citation13, Citation15]. Highly aggressive lymphomas,such as lymphoblastic lymphoma and Burkitt's lymphoma progress rapidly,whichwasnot the case in our cohort.

Regarding the pathological types and molecular biology of DLBCL, we found that non-GCB(73%) were predominant in PB-DLBCL according to the Hans algorithm, with an unfavorable prognosis. This was consistent with previous reports[Citation19] on nodal and extranodal lymphomas. Non-GCB is associated with mutations inMYD88L256P, CD79B, NOTCH1, and other genes associated with poor prognosis[Citation21]. In our study, DEL and DHL lymphoma proportions in PBL were remarkable (14/31). However, DEL and DHL were classifiedaccording to WHO classification in 2016. Hence, most of our patients did not undergo detection tests for MYC/BCL2/BCL6 expression, and FISH tests were not conducted in more than half of the patients. No survival differences were identified in our study, and follow-up and observation need to be continued. DEL and DHL are subtypes with poor prognoses independent of the COO classification[Citation22]. Some researchers have proposed the use of high-intensity induction chemotherapy for patients, including DA-EPOCH-R/MA(rituximab, dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, alternating with high-dose methotrexate and cytarabine)[Citation17, Citation23] and R-Hyper-CVAD(rituximab, hypofractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, alternating with cytarabine plus methotrexate). Our center also recommends sequential ASCT for DHL patients after remission with induction chemotherapy.

Blood test reports were comprehensively collected to explore better this small group of patients’ adverse prognostic factors. Elevated ESR has previously been suggested as a poor prognostic factor for Hodgkin's lymphoma[Citation24]. In our cohort, other general prognostic risk factors, such as ESR, LDH level, B symptoms, and IPI scores, were equally applicable in PB-DLBCL, showing poor prognostic factors for both OS and PFS (P < 0.05). The stage-adjusted IPI can also identify patients with a survival benefit, even if the disease is confined to an early stage. Although B symptoms in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma are frequently neither recorded nor accurate, as mentioned in the Lugano classification[Citation25], they are still crucialin lymphoma patients, especially those with weight loss.

Surgery did not improve the regarding OS or PFS in our cohort. Current studies have led to the consensus that surgical treatment of PBL is not recommended. Biopsy and surgery could be performed only for diagnostic purposes. The cornerstone of systemic chemotherapy for PB-DLBCL is an anthracycline-based regimen. A previous study reported that no survival benefit was identified with the addition of rituximab in PBL; however, the advent of rituximab significantly improved the survival of DLBCL patients[Citation23]. Moreover, the five-year PFS of patients who receivedrituximab in our cohort was better than those without uesd. Considering the small sample size of both our study and previous studies [Citation9–11, Citation26], most of which were retrospective studies, and the fact that the heterogeneity of patients was too large to verify the true effect of rituximab, we suggest that R-CHOP should still be adopted frontline. Hu also found that rituximab significantly reduced the cumulative risk of progression or relapse[Citation27]. Other regimens can be attempted for special subtypes such as DEL or DHL.DA-EPOCH/MA regimens may be better for DHL[Citation17], with a 5-year OS of 57.1%, which is significantly better than the conventional R-CHOP regimen, but it conferred more substantial myelocytic toxicity. Sequential ASCT in DHL-PBL patients can obtain dual benefits of OS and PFS[Citation17].

In PB-DLBCL, involved site of radiotherapy (ISRT)is administered for the breast tissue on the lesion side and lymph nodes in the drainage area, and the dose is generally between 30-50Gy. However, because of the small proportion of patients who underwent RTin our study, we got no conclusion. RThad survival and PFS benefits in IE and IIE stage patients[Citation16], andsome patients underwent radiotherapy alone, whereby the control effect on local lymph node recurrence was also good. In summary, systemic treatment based on chemotherapy should be determined based on the patient’s clinical conditions.

In total, 92% of the patients in our study achieved CR/PR after the induction of therapy, indicating that breast lymphoma was also very sensitive to frontline chemotherapy. However, 25/63(39.7%) patients relapsed and progressed. Breast and CNS recurrence were the main recurrence sites in our patients, consistent with an earlier report[Citation27]. The 5-year OS of patients with recurrence decreased significantly, especially in patients with CNS relapse, and the median survival time was only 20 months. However, in the multivariate analysis, CNS relapse was not an independent factor for poor prognosis, and we believe that the reasons were as follows: first, the sample size of this study was minor. Second, the treatment after relapse was inconsistent, and some patients had concurrent recurrence atother sites. Therefore,there were too many confounding factors. The probability of breast recurrence in PBL patients was earlier found to be between 23% and 62%[Citation7]. In contrast, the probability of breast recurrence (ipsilateral and contralateral breast) in our PB-DLBCL patients was 17.74%. Several studies have reported that radiotherapy is a protective factor for lateral breast recurrence. However,the proportion of radiotherapy in our patients was relatively low, which requires further confirmation.

In our study, 84% of patients with PB-DLBCL received CNS prophylaxis. However, 9.5% still experienced central nervous system recurrence. All patients with CNS progression were administereda preventive intrathecal injection along with chemotherapy, indicating that better prevention strategies are needed, such as novel target drugs. BTK inhibitor had shown good efficacy in central nervous system lymphoma. Two patients with long-term CNS recurrence of >10 years, indicated that patients with PBL faced not only short-term recurrence but also the risk of long-term recurrence. In a prospective study of DLBCL, standard R-CHOP combined with HD-MTX was found to have a 2-year OS benefit. However, the 2-year risk of CNS recurrence was still 12.4%[Citation28]. CNS-IPI[Citation29] had no specificity in PBL, and this score added renal and adrenal involvement based on IPI, while PBL excluded such patients by this definition. The high CNS recurrence rate in such primary extranodal organs is worth exploring, including whether there are molecular biological differences and whether the prevention methods, intensity, and dose can be changed. Our group aims to rearrange and analyze the biopsyspecimens in near further.

Several patients underwent ASCT after relapse (63.5% in the 5-year OS ASCT group vs 51.3% in the non-ASCT group) and achieved a relatively good survival. Currently, ASCT is the primary choice for eligible R/R patients with CR/PR. It is also the only treatment that has the potential for cure [Citation17].

Our study had several limitations. First, because of the rarity of the disease, this was a small retrospective study, which reduced the statistical powerand accuracy of the conclusions. Second, the heterogeneity of the patients was high because of the long-time span of the study. Most data were internally stratified, and the level of evidence was insufficient, with factors beyond lymphoma, such as comorbidities and treatment-related adverse effects, being given less importance. However, considering the scarcity of this type of global study and the low feasibility of conducting prospective cohort studies, this retrospective study still has great significance for clinical guidance.

Summary/conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has explored the prognostic risk and relapse factorsof PB-DLBCL in a relatively large Chinese PBL cohort. The onset of PBLoccurred at a younger age, and a combined modality of treatmentwas recommended. Local breast and CNS recurrence after standard frontline treatment are the main issues experienced by these patients and require further study. More studies are needed to determine whether patients with PB-DLBCL need to be strengthened or find new CNS prophylaxis and prevention of local recurrences, such as prophylactic breast irradiation.

Ethics statement

All patients signed informed consent forms when they were first hospitalized at our center. No patient’ tissue or blood samples were studied.

yhem_a_2150389_sm6967.docx

Download MS Word (22.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank all the doctorsin the Lymphoma Department at Peking University Cancer Hospital and all the patients included in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aviv A, Tadmor T, Polliack A. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: looking at pathogenesis, clinical issues and therapeutic options. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(9):2236–2244. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt192. Epub 2013/05/29. PubMed PMID: 23712546.

- Peng F, Li J, Mu S, et al. Epidemiological features of primary breast lymphoma patients and development of a nomogram to predict survival. The Breast. 2021;57:49–61. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2021.03.006. PubMed PMID: 33774459; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8027901.

- Wiseman C, Liao KT. Primary lymphoma of the breast. Cancer. 1972;29(6):1705–1712. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197206)29:6 < 1705::aid-cncr2820290640 > 3.0.co;2-i. Epub 1972/06/01. PubMed PMID: 4555557.

- Takahashi H, Sakai R, Sakuma T, et al. Comparison of clinical features between primary and secondary breast diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a yokohama cooperative study group for hematology multicenter retrospective study. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfusion. 2021;37(1):60–66. doi:10.1007/s12288-020-01307-7. PubMed PMID: 33707836; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7900317.

- Zhang T, Zhao H, Cui Z, et al. A multicentre retrospective study of primary breast diffuse large B-cell and high-grade B-cell lymphoma treatment strategies and survival. Hematology (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2020;25(1):203–210. doi:10.1080/16078454.2020.1769419. Epub 2020/06/02. PubMed PMID: 32476626.

- Martinelli G, Ryan G, Seymour JF, et al. Primary follicular and marginal-zone lymphoma of the breast: clinical features, prognostic factors and outcome: a study by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(12):1993–1999. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp238. Epub 2009/07/03. PubMed PMID: 19570964.

- Lalani N, Winkfield KM, Soto DE, et al. Management and outcomes of women diagnosed with primary breast lymphoma: a multi-institution experience. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169(1):197–202. doi:10.1007/s10549-018-4671-8. Epub 2018/01/23. PubMed PMID: 29356916.

- Uesato M, Miyazawa Y, Gunji Y, et al. Primary non-hodgkin’s lymphoma of the breast: Report of a case with special reference to 380 cases in the Japanese literature (Tokyo, Japan). Breast Cance. 2005;12(2):154–158. doi:10.2325/jbcs.12.154. Epub 2005/04/29. PubMed PMID: 15858449.

- Zhang N, Cao C, Zhu Y, et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the era of rituximab. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6093–6097. doi:10.2147/OTT.S108839. PubMed PMID: 27785056; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5065257.

- Ou CW, Shih LY, Wang PN, et al. Primary breast lymphoma: a single-institute experience in Taiwan. Biomed J. 2014;37(5):321–325. doi:10.4103/2319-4170.132889. Epub 2014/09/03. PubMed PMID: 25179707.

- Aviles A, Neri N, Nambo MJ. The role of genotype in 104 cases of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma primary of breast. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012;35(2):126–129. doi:10.1097/COC.0b013e318209aa12. Epub 2011/02/18. PubMed PMID: 21325938.

- Kuper-Hommel MJ, Snijder S, Janssen-Heijnen ML, et al. Treatment and survival of 38 female breast lymphomas: a population-based study with clinical and pathological reviews. Ann Hematol. 2003;82(7):397–404. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0664-7. Epub 2003/05/24. PubMed PMID: 12764549.

- Kewan T, Covut F, Ahmed R, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of primary breast lymphoma: The Cleveland clinic experience. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8611, doi:10.7759/cureus.8611. PubMed PMID: 32676248; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7362621.

- Pérez F F, Lavernia J, Aguiar-Bujanda D, et al. Primary breast lymphoma: analysis of 55 cases of the spanish lymphoma oncology group. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leukemia. 2017;17(3):186–191. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2016.09.004. Epub 2016/11/17. PubMed PMID: 27847267.

- Ryan G, Martinelli G, Kuper-Hommel M, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the breast: prognostic factors and outcomes of a study by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(2):233–241. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm471. Epub 2007/10/13. PubMed PMID: 17932394.

- Jennings WC, Baker RS, Murray SS, et al. Primary breast lymphoma. Ann Surg 2007;245(5):784–789. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000254418.90192.59. PubMed PMID: 17457172; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1877073.

- Zhang T, Zhang Y, Fei H, et al. Primary breast double-hit lymphoma management and outcomes: a real-world multicentre experience. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):498, doi:10.1186/s12935-021-02198-y. PubMed PMID: 34535141; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8447786.

- Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–2390. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569. PubMed PMID: 26980727; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4874220.

- Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 2004;103(1):275–282. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545. Epub 2003/09/25. PubMed PMID: 14504078.

- Yhim HY, Kang HJ, Choi YH, et al. Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with breast diffuse large B cell lymphoma; Consortium for Improving Survival of Lymphoma (CISL) study. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:321, doi:10.1186/1471-2407-10-321. PubMed PMID: 20569446; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2927999.

- Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, et al. Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(15):1396–1407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1801445. PubMed PMID: 29641966; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6010183.

- Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Tzankov A, et al. MYC/BCL2 protein coexpression contributes to the inferior survival of activated B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and demonstrates high-risk gene expression signatures: a report from The International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program. Blood. 2013;121(20):4021–4031. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-10-460063. quiz 250. PubMed PMID: 23449635; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3709650.

- Feugier P, Van Hoof A, Sebban C, et al. Long-term results of the R-CHOP study in the treatment of elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a study by the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(18):4117–4126. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.09.131. Epub 2005/05/04. PubMed PMID: 15867204.

- Henry-Amar M, Friedman S, Hayat M, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate predicts early relapse and survival in early-stage Hodgkin disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(5):361–365. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-114-5-361. Epub 1991/03/01. PubMed PMID: 1992877.

- Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3068. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. PubMed PMID: 25113753; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4979083 are found at the end of this article.

- Luo B, Huang J, Yan Z, et al. Clinical and prognostic analysis of 21 cases of primary breast lymphoma. Zhonghua xue ye xue za zhi = Zhonghua xueyexue zazhi. 2015;36(4):277–281. doi:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2015.04.003. Epub 2015/04/29. PubMed PMID: 25916285; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7342608.

- Hu S, Song Y, Sun X, et al. Primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: Therapeutic strategies and patterns of failure. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(12):3943–3952. doi:10.1111/cas.13828. PubMed PMID: 30302857; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6272095.

- Jeong H, Cho H, Kim H, et al. Efficacy and safety of prophylactic high-dose MTX in high-risk DLBCL: a treatment intent-based analysis. Blood Adv. 2021;5(8):2142–2152. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003947. PubMed PMID: 33881464; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8095148 interests.

- Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, et al. Cns international prognostic index: A risk model for CNS relapse in patients With diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated With R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3150–3156. doi:10.1200/JCO.2015.65.6520. Epub 2016/07/07. PubMed PMID: 27382100.