ABSTRACT

Research question

Building on the growing demand for organisations to generate both economic and social value, this study explores the creation of shared value (CSV) by major sport events (MSEs) and their sponsors.

Research methods

Semi-structured interview data were collected from multinational, senior industry practitioners with a sponsorship remit. Template analysis was employed to generate a model of shared value creation that extends prior literature.

Results and findings

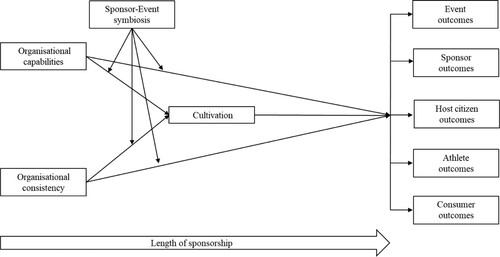

Findings indicate that sponsors and MSEs can utilise organisational capabilities, consistency and cultivation to create shared value. This process is boosted by a symbiotic relationship between MSEs and sponsor(s). The length of sponsorship also affects positive outcomes arising from CSV by a number of additional actors within the ecosystem, including host citizens, athletes, and consumers.

Implications

This study posits a model that advances the concept of CSV and its application within the context of MSEs. It contributes to developing enduring sponsor-MSE relationships aimed at creating a lasting footprint with a range of actors within their ecosystem. Also, the study provides nuanced insights for practitioners and academics about the importance of CSV.

Introduction

Sports have long attracted the interest of sponsors seeking the commercial potential of sport properties (IEG, Citation2017). Existent sponsorship studies focus predominantly on the transactional, benefit-generating relationship between sport properties and sponsors (Cornwell, Citation2008); whereby properties benefit financially and sponsors obtain desirable communication opportunities in return (Demir & Söderman, Citation2015). Despite the breadth of sponsorship studies (e.g. Biscaia et al., Citation2013; Jensen & Cobbs, Citation2014), most research is siloed across disciplines with little known about management of the sponsorship process (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2020).

Previous research has not fully appreciated how sponsors, sponsees and other actors in the sport ecosystem can co-create value for different beneficiaries (Johnston & Spais, Citation2015). This is apparent in a major sport event (MSE) context, given the multiplicity of actors involved (Horne, Citation2007) and the engagement opportunities these events represent (Storbacka, Citation2019). As noted by Vargo and Lusch (Citation2008), no single actor possesses the resources to create value in isolation. Woratschek et al. (Citation2014a, p. 18) refer that ‘traditional models of value creation in sport management fall short of capturing the true nature of value creation’, initiating the sport value framework (SVF) by building on the foundational premises (FPs) of service-based dominant logic (SDL) within sport contexts. Whilst the SVF presents a compelling rationale for evolution from value ‘chain’ to ‘network’, there is an overriding focus on consumers. On the other hand, Woratschek and colleagues note that if too many variables are analysed together, it can be difficult to gain deep insights into the value creation process. Thus, a micro-level analysis (e.g. dyadic structures such as MSEs and sponsors) can advance knowledge of CSV within sport without examining the value co-creation process involving all actors (Woratschek et al., Citation2014b). Moreover, the influence of the relevant sport ecosystem on the sponsoring process has not been examined (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2020).

Additionally, an increasing need for sustainability has led sport properties and sponsors to operate corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes (Inoue et al., Citation2017). However, these efforts have become commonplace, focusing on reputation with limited connections to businesses, making them difficult to justify (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011; Wu et al., Citation2020). As a result, CSR remains largely theoretical (Walzel et al., Citation2018), providing organisations with lessening differentiation and viability for addressing genuine societal change (Skarmeas & Leonidou, Citation2013). Furthermore, leveraging activities undertaken to maximise the long-term benefits of events (Chalip, Citation2004) should not be used purely for public relations purposes but as means to create value for different actors in a MSE network (Smith, Citation2014).

Porter and Kramer (Citation2011) advocate organisations ‘Creating Shared Value’ (CSV) by focusing on generating both economic value and value for society by addressing its needs and challenges. Whilst CSV offers societal opportunities that may extend to sport properties and sponsors, scarce empirical data exists (Corazza et al., Citation2017). Also, whilst the SVF applies SDL to the sports field, methods to capture and understand CSV remain elusive, with little known about its advantages within the sport ecosystem. Given the need for more research focusing on: sponsorship management (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2020); value-in-context at different levels of the sport ecosystem (Horbel et al., Citation2016); CSR limitations (Skarmeas & Leonidou, Citation2013); and conceptualisation of CSV (Corazza et al., Citation2017), this study’s purpose is to explore sponsor and sport property representatives’ perceptions of how the platform of MSEs can be utilised to create shared value with, and for, different actors. It provides a blueprint for further empirical work and supporting practitioners in strategic decision-making.

Theoretical background

Major sport events and CSV

Considering there is no definitive classification of sport events, this study focuses on secondary and tertiary tiers of events (Black, Citation2014; Müller, Citation2015) for several reasons. Firstly, a greater number of communities host such events (Black, Citation2014), offering more opportunities for actors to obtain benefits (Smith, Citation2009). Secondly, these events offer optimal positioning for sponsors to communicate with large audiences (O’Reilly et al., Citation2008) due to their media coverage and associated social, political, economic and ideological impacts, such as infrastructural development (Mills & Rosentraub, Citation2013). Thirdly, MSEs have received considerably less scholarly attention than mega sport events, representing a fertile area of future inquiry.

The term ‘CSV’ was first acknowledged by Porter and Kramer (Citation2011). It refers to a strategic approach summoning companies to pursue success by generating economic benefit and simultaneously addressing societal challenges (Corazza et al., Citation2017), thus creating value. Therefore, CSV demands long-term investment, driving sustainable competitiveness by addressing social and environmental goals. Such strategies may include reconceiving products and markets (unmet societal needs targeted as profitable growth opportunities); redefining productivity in value creation (seeking greater efficiencies and reinforcing stakeholder relationships); and enhancing local cluster development (nurturing of supporting organisations to encourage value creation) (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011).

Although CSV represents a managerial concept built around the missing link between CSR and competitive advantage strategies (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011), it has not escaped criticism. Crane et al. (Citation2014) intimate that CSV ignores regulatory challenges arising from business compliance, over-simplifying the role played by corporations. Corazza et al. (Citation2017) highlight a lack of standardisation regarding the approach of organisations claiming involvement in CSV. This indicates CSV requires further conceptual and empirical development to better understand how to address organisational challenges in contemporary societies (Dembek et al., Citation2016).

Indeed, the principle of CSV is not to disparage CSR, but to enable business leaders to understand better alignment between a company’s core strategy and the societal issues it can impact (Visser, Citation2013). CSV ‘expands the total pool of economic and social value’ (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011, p. 65), instead of merely restructuring value ‘already created by the firm’ (Lee et al., Citation2014, p. 461). Various organisations have employed CSV-related terminology through their corporate communications (e.g. Experian, Citation2019; Kirin, Citation2019). However, examples are sporadic within sport sponsorship (e.g. Jaguar Land Rover promoting synergies with the Invictus Games beyond traditional ROI; Cameron, Citation2019). For the concept to become more impactful, greater understanding is required. It is also important that the scope of CSV (i.e. an overarching business philosophy enabling firms to align core strategies with addressing societal issues; Lee et al., Citation2014) is broader than the concept of event leveraging (i.e. exploitation of event-related resources to achieve desired outcomes; Misener, Citation2015). Leverage activities are event-led and may form part of an overall CSV-based strategy, but CSV is a more holistic corporate outlook seeking to generate additional value between multiple actors.

Consequently, a more strategic and integrated framework relating ideas and illustrations from the sponsorship ecosystem is needed (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2020), shifting language from ‘responsibility’ to ‘value’ and extending MSE leverage opportunities to a broader range of actors. The notion of value has been debated extensively, with Vargo and Lusch (Citation2004, Citation2008, Citation2016) attaining pre-eminence by articulating SDL based on value co-created by numerous actors. Critically, singular parties cannot create and/or deliver value independently, therefore, actors individually offer value propositions for potential value creation but ‘value-in-context’ (Vargo, Citation2008) is co-created via resource integration between actors (A2A). Tsiotsou (Citation2016) stresses the importance of context in value creation in providing a structure for the exchange, service and capability of resources. Value creation extends beyond direct A2A exchanges, resulting in an actor’s individual value co-creation efforts being ‘a function of its simultaneous embeddedness within multiple dyads, triads, complex networks and service ecosystems’ (Chandler & Vargo, Citation2011, p. 45). Therefore, dyadic associations between sponsors and MSEs, and the array of connected actors, represent original and unique networks within which value can be created and shared.

Allied to this, the SVF urges consideration of sport events as co-creation platforms (Woratschek et al., Citation2014a). By moving beyond a singular engagement platform perspective towards a holistic understanding of service ecosystems (i.e. self-adjusting systems of actors connected by institutional arrangements and mutual value creation through service exchanges; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016) it can be clarified whether, how, and why these engagement platforms may enhance resource exchange and integration (Breidbach et al., Citation2014). Emerging literature considers service ecosystems in consumer (Tsiotsou, Citation2016) and team sport contexts (Stieler & Germelmann, Citation2018) but MSEs remain underexplored. This is surprising given their sizeable engagement platform and status as service-delivery vehicles (Kim et al., Citation2020). Thus, the event host’s principal role is to enact a ‘support mechanism rather than control mechanism’ (Erhardt et al., Citation2019, p. 4207) by facilitating the integration of value propositions of a variety of actors, including sponsors.

Based on CSV literature (e.g. Porter & Kramer, Citation2011) and the potential offered by sport ecosystems, exploring CSV in a sport context is timely. The necessitated transition towards a CSV mind-set requires actor interchange to bridge the gap between strategic governance of multinational corporations and geographically wide-ranging social impacts (Corazza et al., Citation2017). Also, an understanding of CSV can represent a roadmap for actors within MSE ecosystems, offering engagement platforms for sponsors and MSEs to produce an enduring social footprint.

Development of CSV and associated actors

CSV emphasises that firm competitiveness and the economic health of surrounding communities are mutually dependent (Porter & Kramer, Citation2011). Companies are likely to generate shared value when having the capabilities (i.e. unique competences that add value) to do so, when there is consistency between the creation of shareholder and social value (i.e. perceived congruence), and when value can be cultivated (by other parties) beyond the enterprise that created the original initiative (Maltz & Schein, Citation2012).

Corresponded with the resource-based view, a firm’s unique capabilities yield long-term returns for shareholders and society if these competences remain resistant to competitive threats and provide added value (Barney, Citation2001). Capabilities allow organisations to deploy resources to achieve strategic goals (Aaker & Joachimsthaler, Citation2000) by undertaking activities which are heavily influenced by the social actors involved (Manoli, Citation2020). Furthermore, consistency relates to the contending objectives of addressing social issues whilst aspiring to augment corporate performance (Miragaia et al., Citation2017). Adherence to stated values and careful selection of business partners with complementary social commitments validates an organisation’s consistency since failure to ‘walk the talk’ is a criticism of companies claiming social responsibility (Meehan et al., Citation2006). Shared value must also be cultivated by other entities beyond the firm (Porter & Kramer, Citation2006) through supply-chain influence, competitive response, technology transfer and NGO partnership (Maltz & Schein, Citation2012). This may be characterised within MSE settings by relationships between interconnected sport-related organisations, sustained by any mix of competition, coordination, cooperation, collaboration, and citizenship (Gerke et al., Citation2015). Given that MSEs receive significant sponsorship investment, sponsors’ capabilities, consistency, and cultivation are important assets for CSV.

The fundamental premise of sponsorship is sponsor-sponsee exchange (Crompton, Citation2014). According to Babiak (Citation2007), such ‘interorganisational relationships’ are voluntary, close, long-term, planned strategic actions between two or more organisations for serving mutually beneficial purposes in a problem domain. Global sponsorships require ongoing ‘sustentation’ (Cornwell, Citation2014), which demands commitment and trust not apparent in other promotional communications (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Also, it has been suggested that long-term relationships can positively impact business objectives due to a learning process occurring over time (Jensen & Cornwell, Citation2017) and the effect of repeated exposure on perceptions of sponsor-sponsee fit (Mazodier & Quester, Citation2014). However, there remains a need to further understand sponsor and MSE collaborations to aid development of sustainable and mutually beneficial relationships. Whilst the relationship marketing paradigm can explain the dynamics of business-to-business (B2B) interactions (Gronroos, Citation1994), its application to sponsorship has not addressed the dynamism between sport property and sponsor interactions (Jensen & Cornwell, Citation2017). Subsequently, deeper understanding of sponsor-MSE relationships would likely illuminate drivers of CSV.

Moreover, shared value may be created with, and for, other actors within the sport ecosystem. Value for MSEs may materialise in revenue generation, B2B support, or media exposure (Crompton, Citation2014). Sponsor value may relate to increased cognitive, affective and behavioural consumer responses (Cornwell et al., Citation2005). Sponsored MSEs also offer potential for value co-creation with other actors such as host regions (e.g. enhancing reputation; Horne, Citation2017), citizens (e.g. community pride; Inoue & Havard, Citation2014) and fans (e.g. favourable judgements of direct and indirect interactions across a range of touch points; Yoshida, Citation2017). Following literature on CSV (e.g. Dembek et al., Citation2016) and MSE sponsorship (e.g. O’Reilly et al., Citation2008), further research on shared value derived from sponsorships is timely and warranted. The current study aims to extend existent literature by exploring perceived approaches to creating shared value by sponsors and MSEs and how this may impact other actors within the MSE ecosystem.

Method

Pilot study

A pilot study comprising individual interviews with senior industry practitioners (n=10; sample characteristics in online Appendix 1) was conducted to provide contextual understanding of CSV within MSE settings. Contact with participants was initiated via email or LinkedIn and interviews were conducted online to provide flexibility due to their geographic dispersity (Deakin & Wakefield, Citation2014). Participants were situated within their chosen professional environment, with no third-party present.

Similar to Schönberner et al. (Citation2020), a range of participant selection criteria were used: (1) attainment of a senior managerial or director-level position within their organisation, (2) a clear remit for sponsorship within their role, evidenced by a minimum of five years’ industry experience within a sport or sponsor-related organisation. Additionally, given the global and multicultural nature of MSEs, (3) it was necessary for the sample to be multinational (both nationality and employment location). Potential participants were identified based on a convenience purposive sampling approach (Patton, Citation2002). This strategy is valuable when researchers aspire to collect data that can be used as a catalyst for future studies (Berg, Citation2004), such was the case for this pilot study. Subsequently, template analysis (e.g. King, Citation2004; Citation2012) was employed, facilitated by NVivo to examine participants’ perspectives regarding CSV.

Participants and procedures

For the main study (n = 25; sample characteristics in online Appendix 2), participant recruitment was limited to practitioners directly involved in MSE sponsorship, either as a sponsor or MSE manager. The average interview length was 45 minutes. Identifiers were assigned to further censor participant identities and guarantee response anonymity. A semi-structured interview guide was finalised based on feedback received from a panel of seven academic subject experts, the pilot study, and key issues specified in the literature related to CSV and the MSE ecosystem.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Template analysis, facilitated by NVivo, was chosen due to its flexibility, situated between ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ styles of analysis (Brooks & King, Citation2014). Such analysis is particularly suitable for samples of 15–30 (King, Citation2012), and advocates a flexible coding structure, whereby inductive codes were added to an initial template, created using a deductive approach (Guest et al., Citation2012), utilising initial codes formed from concepts identified within the literature review.

Once coding was completed, the researchers ran a series of NVivo queries to assess generated codes. A combination of ‘text search queries’, and ‘coding stripes’ were used to investigate each element, with key quotes and findings noted throughout. Upon completion of the interviews, participants were contacted to review and comment on themes, allowing for member checking (Creswell, Citation2009). Credibility was enhanced through interviewing experienced senior managers involved in sponsorship on an international scale. Online Appendix 3 outlines this process.

Results

These findings draw on extracts from the main study interviews to illustrate CSV drivers, sponsor-MSE relationships, the length of the sponsorship relationship, and outcomes arising from CSV with actors within the ecosystem. depicts a proposed conceptual model for understanding the components of CSV and the shared value created with a range of actors, which is driven by the interview results and extends MSE and CSV literature.

The ensuing parts demonstrate how the model’s components contribute towards CSV. Firstly, context is important for value creation in providing a structure for the exchange, service and capability of resources. MSE04 acknowledged that ‘smaller environments’ do not offer lesser potential for CSV. Secondly, the ‘three Cs’ – capabilities, consistency, and cultivation – detail how CSV can be operationalised when sponsors and MSEs work together. Thirdly, the model specifies how various actors (e.g. MSEs, sponsors, host citizens, athletes, and consumers) may utilise MSEs to create shared value.

CSV drivers

The importance of CSV drivers was indicated, with all participants acknowledging at least one element driving CSV in . A summary of participants’ responses regarding these factors and the symbiosis between sponsor and MSE can be found in online Appendix 4.

Capabilities

Responses suggest that capabilities (i.e. unique competencies) of both sponsor and MSE can directly drive outcomes for CSV beneficiaries, as well as being fundamental to the cultivation process. Sponsor18 described the scope provided by the ‘scale and size’ and ‘high consumption and penetration rates’ of their organisation as integral for building actor engagement platforms. The ability to project an image of integrity and credibility was recognised by 10 participants as being particularly crucial. For instance, MSE14 acknowledged the significance of ‘integrity, honesty, and trust’ in supporting its brand positioning to ‘unite and inspire’, and MSE28 revealed their organisation benefited from regarding ‘integrity and credibility as being extremely important’ by receiving an endorsement from an independent body for being the ‘cleanest sport’ in its country. As MSE19 reflected: ‘It’s about the integrity of the game […] once you start to undermine anyone’s trust, then as a product you’re in real trouble.’

Furthermore, strong innovation credentials, flexibility, and adaptability were highlighted as key operant resources for value creation by 16 respondents. Sponsor21 emphasised the growing worth of emotional intelligence for sponsorship decision-makers in redefining productivity in value creation via reinforcement of cultivating stakeholder relationships, where ‘there’s always something more you can do with regards to dealing with a partner or prospective partner’. Relatedly, the notion of ‘design thinking’ allows managers to ‘adapt to their counterparts’, by ‘listening, relationship-building […] so you can be more upfront, open to saying things you wouldn’t otherwise, creating a bond that would open business doors’. Furthermore, MSE01 detailed its organisation’s capacity to ‘deliver excitement, anticipation, surprise’ as part of a ‘story-telling component’. This helps the MSE to be a ‘positive force for good’ in cultivating value, such as affiliations with other sport properties to deliver social benefits (e.g. dual-branded anti-bullying campaigns).

Consistency

Responses concerning consistency (i.e. perceived congruence between shareholder and social value) indicated that this element can also generate beneficial CSV outcomes, in addition to being a necessary precursor to cultivation. Nine participants discussed the role of authenticity in helping facilitate consistency for sponsors and MSEs, such as MSE20: ‘It worries me that […] we almost pay lip service to society, but I actually think there is a bigger long-term effect when you genuinely do involve society.’ Such authenticity is detailed by MSE16, who commented that many sponsors are ‘looking to a more purpose-led approach in terms of positioning and doing something that really stands out […] because people are looking and seeing’. This respondent also highlighted a sponsorship which became a ‘positive force for social change’ by focusing on ‘gender equality and empowerment’. MSE01 further emphasised ‘you can sponsor as much as you want but if you can’t do anything meaningful with it then what’s the point?’

Complementarily, 15 participants noted the importance of balancing commercial returns with producing societal benefits. As MSE14 stated; ‘One has to come with the other. Societal impact has a wider effect long-term, financial has a greater impact short-term, we constantly look at that’. MSE16 cited misalignment in consistency perspectives between senior executives and middle managers involved in the sponsorship process. They felt managers making day-to-day ROI decisions lacked empowerment with the ‘values-driven approach becoming in-vogue at board level’. When this MSE approaches prospective partners, they encounter many inexperienced marketers, who are pressured to demonstrate shareholder value, and struggle to justify ‘spending money on something relatively intangible’.

Sponsor-event symbiosis

The importance of symbiotic relationships between sponsors and sport properties for CSV was emphasised to some extent by all participants. A symbiosis between sponsor and MSE can enhance the efficacy of capabilities and consistency in generating value for other actors in the MSE ecosystem. MSE01 articulated the importance of ‘mutually beneficial partnerships’, with MSE14 describing ‘a fantastic partnership that has nothing to do with putting a logo up (but) needing something from each other. We could only achieve what we want, by working together’. This implies equal status afforded to each party and a shared philosophy. MSE16 further described the need for diversity and inclusion in its sponsors’ recruitment, implying a re-conception of products and markets by identifying and reframing unmet social needs leading to shared value:

From the beginning we have conversations with [sponsor] about their own diversity and inclusivity policies, what they do to increase diversity and inclusivity in recruitment, in the workplace, every element where there is possibility of increasing and improving the opportunities for disabled people, that’s an agenda that we push with every single one of our partners.

Furthermore, another interviewee underlined the need for partners to be aligned culturally: ‘We looked at our core values and [sport property’s] core values and we challenged people, “which are which?” No one could get them right because […] you’d struggle to know’ (Sponsor27).

Other participants discussed the mechanics of a symbiotic sponsor-MSE relationship, identifying the importance of involvement. Sponsor13 explained that their employer ‘likes to be involved in events so we can make a difference’. This level of sponsor involvement in the MSE extended to aspects such as selecting charitable activities, shaping player fields and being ‘involved in all the details […] to be proud of what we’re associated with and what makes a difference’.

A sponsor-MSE symbiosis can intensify the effectiveness of both capabilities and consistency in creating shared value outcomes. Regarding capabilities, eight participants acknowledged the expertise provided by counterparts. MSE14 referenced marketing knowledge and technological proficiencies contributed by sponsor partners ‘who become our marketers’. In this case, sponsor selection criteria were based around ‘choosing partners that will go and do great work for us’. The same participant emphasised a halo effect imparted from MSE to sponsor:

We articulate your message quicker because we have one of the most recognisable symbols in the world. When people see (our logo) they think of key terminology (inclusiveness, participation, dedication) and by association, people articulate your message instantly and we make your money work a lot harder for you.

The importance of a sponsor-MSE symbiotic relationship to increase the impact of consistency on CSV was acknowledged in six further interviews. Sponsor13 mentioned its collaboration with a sport property enabled strategy adaptation in response to ‘legislative restrictions’ related to its products, influencing the implementation of a long-term, mission-driven approach focused on contributing towards the local community. In this case, the sponsor utilised its association with both the men’s and women’s format of the MSE to host a gender summit at the event:

It started in a [temporary building near the MSE]. We had about 30 people and it was hosted by our CEO, with [newsreader] and [sports professional] and we had a panel session. It was a lunch and then an hour and a half of content but the feedback we got was tremendous. The year after it was slightly bigger and grew to about 80 people. Then last year it was in [major events venue] which is quite a big venue and we had 150 people. So, it’s grown every year and it’s something that I’m personally proud of, I worked on it every year and did the opening and closing remarks. It definitely sits outside the normal boundaries of sponsorship – we want to celebrate diversity, inclusion and equality.

Similarly, Sponsor27 declared it’s ‘diversity values and investment in future leadership’ were heightened by a long-standing and successful relationship with a MSE. Here, societal principles were integrated into business strategies as a ‘by-product’ of an allegiance that ‘financially makes sense’ rather than being the driving factor forming a relationship. Contrastingly, MSE15 acknowledged willingness to ‘provide additional mutual value for […] essentially getting things outside the contract […] which helps with renewal of a longer-term deal’.

Cultivation

The interviews also indicate cultivation (i.e. value cultivated beyond the firm’s boundaries by other parties) can occur after the application of capabilities and consistency. Sixteen interviewees referenced examples of collaboration with different organisations positively impacting CSV.

The importance of the media was highlighted in helping cultivate shared value within the ecosystem, such as being accessible to wider audiences via increased exposure. In the case of the UK’s national broadcaster, this was notable as paid-for advertising is not permitted, but certain sponsorship arrangements are acceptable (BBC, Citation2019). From MSE23’s perspective, delivering ‘15 hours of live television on the BBC […] as a brand opportunity we’re quite valuable’. In this case, the broadcast engagement platform provided value-in-context opportunities for the MSE to drive revenue generation, allowed greater scope to ‘engage in fundraising activities’ and to partner with a sponsor to ‘get people into living healthier lifestyles’. As Sponsor18 remarked, ‘You need to have broadcasters on your side’ to cultivate exposure opportunities.

The significance of NGO actors ‘for the greater good’ (MSE14) of the cultivation process was also recognised. MSE01 disclosed; ‘We go out of our way to offer our platforms. We don’t charge [NGOs], we talk to them and say, “how can we help you?” because it helps us ultimately.’ MSE14 referred to a cultivation network between its event and several NGOs, harnessing the capabilities of each actor within the cluster:

[NGO #1] are in with every national governing body and club in the country, we don’t have that access but [NGO #1]’s brand doesn’t mean as much to somebody as ours so we work together to say, ‘Our sponsors want to talk to every sports club in the country. [NGO #1; NGO #2; NGO #3], can you help us get there and similarly, how do we get more people into sports clubs?’ Our brand and athletes can help inspire those.

In this case, the prominence of the MSE brand was harmonised operationally by the embeddedness of NGOs with deep-rooted links to sport governing bodies and sport clubs. MSE14 also referenced another instance of cultivation helping to extend the impact of a CSV initiative:

We ran [sport event] in 2016, where we get over a million people to get active on a single day. The [NGO] were a key stakeholder for that, a drive for volunteers and a talent ID programme – how do we get more people to understand that they have the potential to be a sportsperson even though they might not have thought of it?

Other respondents acknowledged the pivotal role of the MSE or sponsor in expediting cultivation. Sponsor09 noted ‘staff getting involved’ in supporting organisations focused on providing training to disadvantaged young people, and MSE22 referenced the importance of their organisation contributing ‘physically’ to good causes, such as by ‘actually going into the hospitals and installing computers’.

Our results also suggest that to be successful, shared value initiatives cultivate the social component of the initiative beyond the firm’s boundaries, often occurring after the application of capabilities and consistency. One illustration is the co-creation of an online platform to assist disabled people, initially by the sponsor and MSE: ‘We (sponsor) are developing it alongside [MSE]. It is essentially their owned asset but we are helping with the funding and development’ (Sponsor08). Whilst the sponsor is the lead partner, it is essential for other organisations to ‘come on-board […] because it lives or dies by awareness and traffic going to that site, helping that community. The more people pulling in the same direction, the better’ (Sponsor08). The MSE involved (MSE16) added: ‘We’re in need of a media partner […] and then [sponsor] will speak to other partners to bring in their expertise.’ There remains scope for optimisation as collaboration between fellow sponsors is rare due to contractual ‘red tape’. However, ‘the opportunity is there, it’s just finding that project which would benefit from both parties’ involvement’ (Sponsor08).

Length of sponsorship

The length of sponsorship deal (i.e. how the duration influences success) can be crucial to the impact of the aforementioned CSV drivers. Ten participants discussed ancillary benefits resulting from longer-term involvement. MSE23 explained their event ‘would not exist’ but for the security and commitment provided by a long-term sponsor. This allowed the MSE to reconceive its product and market as an opportunity to ‘enable people to get fit and active and change their lifestyle’ and ‘save lives’, ultimately providing support to its consistency-related endeavours.

From a sponsor viewpoint, the reassurance provided by a long-term attachment to a MSE property can uplift capabilities in helping to provide a more credible ‘storytelling platform’ as ‘being able to speak to people across that journey of time is very important’ (Sponsor08). This participant further explained how the trust derived from a longer-term arrangement allowed for a greater degree of experimentation with activation:

We wouldn’t be able to do something so brave and on any sort of scale without their collaboration. We’d probably end up doing something a lot safer, which probably didn’t deliver for us at the level we wanted and would be much more labour-intensive.

Linked to this, commitment to regular activation over a considerable period is particularly important for MSEs running over bi-annual or four-yearly cycles: ‘[Sponsor] are marketing us, putting us at the forefront of their activity and most importantly they’re talking about the [MSE] every day, they’re incredible marketers for us’ (MSE14).

CSV with multiple actors

Responses about the manifestations of CSV indicated a range of outcomes associated with multiple actors within the MSE ecosystem (see ). A summary of these responses can be found in online Appendix 5. A key MSE outcome outlined by five respondents is increasing sport participation. As MSE04 commented, ‘if people don’t play [sport], it doesn’t become relevant’ and therefore it is important CSV helps ‘safeguard the long-term equity of the competitions that sit within (MSE’s) control’ (Sponsor10). Another key outcome for MSEs is improving the perception of a particular sport: ‘We are fighting for a world where [sport] would be a life pursuit people could be proud of. Parents would put on their fridge that their son passed gold in [sport] the same way they would for fencing’ (MSE22).

Regarding sponsor outcomes, responses from 12 respondents suggested conventional benefits such as increased brand awareness. Other outcomes include changing attitudes towards the brand, for example evolving from being regarded purely as a B2B organisation by being ‘more humane to consumers’ (MSE04) or ‘encouraging recruitment from the disabled community […] to be an organisation with greater purpose’ (MSE16). Sponsor13 discussed a more specific outcome related with helping a business to ‘integrate people, policies, values and beliefs’ after a merger. ‘The [other business] operated in quite a different way and sponsorship helps bridge that gap.’

Thirteen participants signalled that CSV generates host citizen outcomes, with acknowledgement that MSEs can facilitate local cluster development to ‘inspire people in the community’ (MSE14). One participant noted the importance of ‘removing barriers to getting active’ (Sponsor08), such as ‘not knowing what activities are available […], needing more inspiration […] and making people feel more comfortable’. Another recalled the benefits of situating elements of the MSE in public areas, outside the stadium, enabling host citizens ‘to get the ambience of the event and the experience, […] they are part of this big thing without having to buy a ticket’ (MSE12). Other viewpoints related to alleviating some of the pressures facing local communities in helping to reconceive the scope of the organisation’s products and markets. For instance, ‘the National Health Service will be a massive beneficiary of more people being inspired to get up and move […] a positive impact on people’s health or mental well-being’ (MSE14). Additionally, ‘if people feel more trust in institutions, in the country, and more advocacy for it – that will make them hopefully work harder, be less reticent to pay their taxes and so forth’ (MSE14).

The creation of value for professional athletes was mentioned by seven participants. One sponsor ‘supports athletes by getting them to open stores, by giving them food vouchers’ (MSE14) and MSE22 mentioned ‘players will be recognised and even more engaged’ as a result of a sponsorship campaign linked to healthy lifestyles (i.e. actor engagement also being important for shared value creation). Another tangible benefit for athletes is technological improvements associated with training. MSE14 reflected that an alliance with a ‘sleep partner’ resulted in ‘product innovations that we could use going forward. If an athlete gets a bad night’s sleep because the mattress at home is different to the mattress while they’re away that will have huge performance disadvantages’. Athletes can also benefit from increased earnings arising from CSV; ‘We pay £15 m a year in prize money. It’s a good number, showing players can earn a living from playing [sport]’ (MSE28).

Finally, CSV outcomes for consumers were noted by nine participants. Sponsor21 discussed the importance of a company’s purpose and how evolving consumer demographics may necessitate a greater focus on CSV:

Gen Z will represent one-third of the planet’s purchasing power by 2030. […] they want to deal in a world where companies and brands have purpose. If you don’t have a purpose they can understand and relate to, they won’t buy into you conceptually and won’t buy your products and services.

You need to create something that engages and inspires spectators […] getting people active through fun. We invite anyone [to the activation area at the stadium] to come and run a little bit of the hurdles, jump, throw or push. We have grandparents coming with their kids […] obviously they push the children to go, but we’re like, ‘no, you’re going to do it as well, do it with your grandchild!’ I think that’s what counts, getting them active a little bit through fun, and maybe encouraging them to go for a longer walk or something in future.

Demonstrating tangible examples arising from CSV can assist sponsors and sport properties in meeting growing societal obligations. These results contribute to a better understanding of the constituent, operational components of CSV, and their worth within the context of MSEs, whilst adding palpability to the CSV concept and demonstrating its growing significance to practitioners, academics, and society.

Discussion

By exploring viewpoints of how sponsors and MSEs can utilise the event platform to create shared value, our framework assists practitioners in providing a roadmap to better understand the actions they should focus on to create shared value for various actors. Theoretically, it contributes by conceptualising and clarifying how shared value can be created within MSE contexts. This addresses gaps in the literature relating to management of sponsorship (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2020), micro structures within the ecosystem to gain insights on the value creation process (Woratschek et al., Citation2014b), CSR limitations (Skarmeas & Leonidou, Citation2013), and clarification of the CSV concept (Dembek et al., Citation2016) by substantiating its operationalisation within a sport ecosystem with the provision of tangible examples.

For instance, findings related to value creation between a sponsor and MSE of an online platform to assist disabled people demonstrates evidence of reconceiving products and markets (an unmet social need for disabled people becoming more active); redefining productivity in the value chain (reinforcing relationships with disabled communities and optimising efficiency by seeking other organisations with the expertise to join the venture); and enabling cluster development (e.g. addition of a media partner, TV broadcaster, and other sponsors).

Within our framework, capabilities, consistency, sponsor-event symbiosis, cultivation, and length of sponsorship assume a vital role in driving CSV. These findings extend the resource-based view (Barney, Citation2001) and suggest that sponsors and MSEs can succeed in creating shared value by building on three, interconnected ‘Cs’. Our findings also add to event leverage literature (e.g. Chalip, Citation2004) by helping to extend opportunities to a broader range of related actors within the ecosystem. Jensen et al. (Citation2016) reference three sources of competitive advantage arising from capabilities. Firstly, regarding sponsorship exclusivity and its role in enforcing brand protection. Our findings indicate this is not critical for CSV, particularly for sponsors in B2B markets. One MSE rights holder (MSE16) ‘observed from the previous event cycle it wasn’t necessary for everybody to have absolutely all sets of rights’. The same participant explained the difference between its ‘tier 1’ and ‘tier 2’ partnerships is the restriction of IP rights in tier 2. Lower tier packages are therefore advantageous to B2B sponsors for whom securing the full range of rights is not necessarily essential. Secondly, wide ranging events offer greater scope to impact more people but less opportunity to engage with a specific consumer profile. However, sponsors increasingly demand flexibility to meet their goals, with a growing reluctance to accept asset packages that do not fit their requirements (Cornwell, Citation2017). Flexibility emerged within our interviews as a key capability for CSV, with MSE23 recognising the need for adaptation to their title partner, such as sending a key staff member to regularly work from their offices and desiring their organisation ‘to be almost part of the sponsoring organisation’. A sponsor participant (Sponsor27) also explained that had there been a greater degree of flexibility shown by a MSE partner during their relationship, it may have lasted longer. Finally, Jensen et al. (Citation2016) referred to image as being related to the value of opportunity. This links with our results and includes being progressive (e.g. investing in mobility-related technologies and online platforms to encourage mobility through sport; Sponsor08), fun (e.g. sponsor activations encouraging people to become more active; Sponsor18), and team-orientated (e.g. the organisation striving to treat its partners as ‘brothers and sisters’; MSE04). It is plausible that the essence of team-sport more closely aligns to CSV, but sponsors of individual-sport MSEs could emphasise within their activation the importance of a team for individual athletes (e.g. a tennis player requires a coaching team, fitness/physio team, support from friends/family to be successful).

Regarding consistency, whilst consumers generally recognise the contribution of sponsors towards the event functioning (Grohs & Reisinger, Citation2014), MSE practitioners perceive a polarisation between short-term revenue generation and longer-term shared value creation. For example, Sponsor27 acknowledged increasing need for sophistication in sponsorship strategy as today’s consumers are more educated about the commercial relationship between brands and sport. An MSE participant (MSE16) recognised ‘two almost irreconcilable forces at work in sponsorships’ with ‘everybody talking about values-driven sponsorship’ at one end of the spectrum and the ‘need for marketers to create instant results’ at the other. According to Müller (Citation2017), MSEs reflect many of the complex paradoxes of modern life, which should be embraced to make use of their unique ability to rally and unite. Therefore, it remains essential for organisations to strike a balance between economics-first and mission-driven approaches to CSV (Maltz & Schein, Citation2012). One MSE representative (MSE12) expressed frustration with evaluation of CSV-related activity due to difficulties in securing the funding and data to do so. An apparent misalignment between CSV principles and sponsorship evaluation was evident in several interviews, suggesting a measurement deficit in sponsorship metrics (Meenaghan & O'Sullivan, Citation2013). This may be operationalised via refined business KPIs, reflecting the growing need to balance financial and societal obligations. Whilst regarded as ‘doing good’, CSR-related endeavours typically sacrifice profitability (Reinhardt et al., Citation2008) and thus have an indirect association with economic value (Wu et al., Citation2020). As a result, Walker et al. (Citation2017) question whether CSR permits ‘win-win’ outcomes, by identifying opportunities to create economic value (one win) and social value (two wins), as is possible with CSV (de los Reyes et al., Citation2017).

The sponsor-MSE symbiosis is also a key element in the framework. Although organisational features such as capabilities and consistency are important for CSV, these effects are heightened by a strategic alliance between sponsor and MSE. This is exemplified by MSE14, expressing ‘our partners become our marketers’, and aligns with previous studies suggesting that sponsors should create a symbiotic relationship with sport properties to legitimise their role (Biscaia et al., Citation2013) across different stakeholders. Strategic alliance formations are subject to internal and external constraints (Lin et al., Citation2007) and thus, relationships with external actors (i.e. sponsors and MSEs) represent intangible, peripheral assets (Ivens et al., Citation2009).

To this end, a fit in business, mission, target audience, geographic location, image, and/or values (Biscaia et al., Citation2017) should be integral for any agreement between sponsor and MSE as this will likely contribute to the perceived relationship authenticity and mutuality (Charlton & Cornwell, Citation2019). That said, there remains an ongoing challenge for firms to be realistic when entering sponsor partnerships. One MSE respondent (MSE28) discussed a pragmatic philosophy whereby ‘what they want and what they get aren’t necessarily the same things’. This is supported by another MSE participant (MSE14), who conceded, ‘Often it is a case of whether our partners choose us than the opposite way around.’

Our framework also highlights cultivation of value by other entities beyond the firm for CSV to be optimised. Responses from participants suggest that regardless of how well sponsors and sport properties work together, the cultivation of relationships with other actors is paramount (Parent et al., Citation2012). A purely dyadic functioning between sponsor and MSE disregards the resources of other actors embedded within social networks resulting in myopia (Storbacka & Nenonen, Citation2011), inhibiting scope for CSV. Therefore, cultivation represents a key element in shared value creation. For instance, interviews indicated that broadcasters and the wider media are important in facilitating cultivation. One sponsor (Sponsor18) mentioned the ‘golden triangle’ created by the addition of media exposure to the MSEs-sponsor partnership, like a fire triangle requiring oxygen in addition to heat and fuel to function. Debate around exposure continues to surround many sports, such as cricket, where despite the victory of the host nation, England, at the 2019 ICC Cricket World Cup, there was significant criticism of the tournament for taking place behind a ‘paywall’ of subscription television and thus missing opportunities for CSV (New Statesman, Citation2019). However, event outcomes depend not only on an event occurring, but rather the way it is leveraged and other related resources are exploited (O'Brien & Chalip, Citation2007) to broaden the value for different actors. Thus, cultivation represents an opportunity for an intermingling of resources to be activated and CSV optimisation.

Linked to this is the length of MSE-sponsor relationships, which can influence success (Crompton, Citation2014) and longer duration partnerships may provide increased possibilities to better understand each other’s abilities. This may lead to both sides learning ways to strengthen the relationship (Mazodier & Quester, Citation2014). Many interviewees articulated how sponsorships evolve over time and lead to greater trust and experimentation. For instance, MSE22 discussed an association with a national blood bank in a European country, where recreational eSport players were incentivised to donate blood by receiving an in-game incentive linked to a congruent phase of the game. This generated 7,000 new blood donors within a month, and subsequently developed into a more enduring association. As health service provider financial constraints will likely intensify in future (Robertson et al., Citation2017), shared value creation involving new and heightened forms of collaboration that cut across profit/non-profit and private/public boundaries can help alleviate these effects. In this sense, our findings empirically align with the foundational premises (FP) of the SVF, and extend FP10 (i.e. firms, customers and other stakeholders can integrate their network resources to co-create value; Woratschek et al., Citation2014a) by demonstrating that actors from other sectors can play pivotal roles in creating shared value in a sport context.

Shared value creation can be substantiated by a range of positive outcomes apportioned between different actors within the MSE ecosystem. It is important for MSEs and sponsors to strive for increasingly innovative solutions. One example emanating from our interviews involved a sports net post manufacturer exploring the possibility of producing equipment made from discarded fishing nets (FIVB, Citation2019). Findings also indicate a close association between host locations and their citizens, with benefits related to improved health and rehabilitation, boosts to the local economy, and greater levels of empowerment facilitated by MSEs and sponsors. Another example involved a sponsor’s MSE-related on-pack promotion where consumers were offered the opportunity to win £2000 worth of sports equipment and an athlete visit for the winners’ chosen schools. Concurrently, the product’s promotion was one of the most successful ever recorded, helping arrest a seven-year sales decline. It also benefited the recipient schools and wider community by providing resources and helping facilitate active lifestyles, which aligns with recent calls to explore the educational benefits of sport events (Ribeiro et al., Citation2020). The athletes involved also received increased recognition and a boost to their profiles. This contributes to generalise Arai et al.’s (Citation2014) findings that athletes’ marketable lifestyles can enhance their overall brand image. Likewise, the facilitation of customer-to-customer interaction is important for increasing satisfaction with the event and highlighting social benefits of event attendance (Koenig-Lewis et al., Citation2018) as well as serving as a potential factor for value co-creation (Rihova et al., Citation2018). A further example related to a sponsor educating MSE consumers about the dangers of drink-driving whilst promoting a zero-alcohol beer, which was supported by other media channels, and is attaining unprecedented growth in its sector. Activations that support these principles are likely to become increasingly important for CSV.

In summary, this study presents a basis to understand CSV in a MSE ecosystem. Results indicate that organisational capabilities, consistency, and cultivation are critical CSV drivers. Furthermore, CSV has the potential to be enhanced through a sponsor-MSE symbiosis. The creation of shared value can lead to outcomes for various target audiences, including the MSE, sponsors, host citizens, athletes, and consumers. Understanding how sport properties and sponsors can work together to create shared value is paramount, and this study represents an initial roadmap to comprehend CSV and assist managers of sponsors and MSEs to reach strategic decisions and provides a more viable outlet for addressing and facilitating societal change.

Limitations and future research

This study has limitations that invite further research. Firstly, although the proposed framework may apply to secondary and tertiary events, such as the Commonwealth Games, due to MSEs’ variety and their cross-cultural nature (Taks, 2015), it may have to be adjusted in future research to accommodate the specific features and diversity of each event. Secondly, external perceptions of sponsors and sport properties were not considered. Public opinion often impacts how brands are perceived by stakeholders (Bies & Greenberg, Citation2017), and most participants expressed concern regarding how their organisation might be perceived regarding CSV-related matters.

Linked to this, whilst this study focuses on the perceptions of two central actors, there are multiple stakeholders in the ecosystem and future studies could explore the CSV perspectives of actors such as tourism boards, professional athletes, consumers, and the media. Additional research opportunities relate to potential misinterpretation of practitioners regarding CSV, given that one participant mentioned ‘there was not enough money in the profit pool to afford to do this’ (Sponsor05). There remains a need for practitioners to become further educated about CSV, and a more coherent narrative compiled by the academic community (Dembek et al., Citation2016). The creation of an instrument based on the proposed model to objectively measure impacts of CSV with a wider sample of actors also represents an important next step to solidify our understanding and application of CSV.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (156.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aaker, D., & Joachimsthaler, E. (2000). Brand leadership. The Free Press.

- Arai, A., Ko, Y. J., & Ross, S. (2014). Branding athletes: Exploration and conceptualization of athlete brand image. Sport Management Review, 17(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.04.003

- Babiak, K. (2007). Determinants of interorganizational relationships: The case of a Canadian nonprofit sport organization. Journal of Sport Management, 21(3), 338–376. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.21.3.338

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4011938

- BBC. (2019). Advertising and sponsorship guidelines for BBC commercial services. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/editorialguidelines/commercial-services

- Berg, B. L. (2004). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Bies, R. J., & Greenberg, J. (2017). Justice, culture, and corporate image: The swoosh, the sweatshops, and the sway of public opinion. In M. J. Gannon & K. L. Newman (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of cross-cultural management (pp. 320–334). Blackwell Business.

- Biscaia, R., Correia, A., Rosado, A. F., Ross, S. D., & Maroco, J. (2013). Sport sponsorship: The relationship between team loyalty, sponsorship awareness, attitude toward the sponsor, and purchase intentions. Journal of Sport Management, 27(4), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.4.288

- Biscaia, R., Trail, G., Ross, S., & Yoshida, M. (2017). A model bridging team brand experience and sponsorship brand experience. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 18(4), 380–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-07-2016-0038

- Black, D. (2014). Megas for strivers: The politics of second-order events. In J. Grix (Ed.), Leveraging legacies from sports mega-events: Concepts and cases (pp. 13–23). Palgrave.

- Breidbach, C., Brodie, R., & Hollebeek, L. (2014). Beyond virtuality: From engagement platforms to engagement ecosystems. Managing Service Quality, 24(6), 592–611. https://doi.org/10.1108/MSQ-08-2013-0158

- Brooks, J., & King, N. (2014). Doing template analysis: evaluating an end of life care service. Sage Research Methods Cases.

- Cameron, M. (2019, February 27). Jaguar Land Rover and the Invictus Games – more than just a sports sponsorship. Paper presented at the Future of Brands Conference: Sydney.

- Chalip, L. (2004). Beyond impact: A generalised model for host community event leverage. In B. Ritchie & S. Adair (Eds.), Sports tourism: Interrelationships, impacts and issues (pp. 226–252). Channel View.

- Chandler, J. D., & Vargo, S. L. (2011). Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory, 11(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593110393713

- Charlton, A. B., & Cornwell, T. B. (2019). Authenticity in horizontal marketing partnerships: A better measure of brand compatibility. Journal of Business Research, 100, 279–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.054

- Corazza, L., Scagnelli, S. D., & Mio, C. (2017). Simulacra and sustainability disclosure: Analysis of the interpretative models of creating shared value. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(5), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1417

- Cornwell, T. B. (2008). State of the art and science in sponsorship-linked marketing. Journal of Advertising, 37(3), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367370304

- Cornwell, T. B. (2014). Sponsorship in marketing: Effective communication through sports, arts and events. Routledge.

- Cornwell, T. B. (2017). Soliciting sport sponsorship. In T. Bradbury & I. O’Boyle (Eds.), Understanding sport management (pp. 172–183). Routledge.

- Cornwell, T. B., & Kwon, Y. (2020). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Research surpluses and shortages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(4), 607–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00654-w

- Cornwell, T. B., Weeks, C. S., & Roy, D. P. (2005). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Opening the Black Box. Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2005.10639194

- Crane, A., Palazzo, G., Spence, L. J., & Matten, D. (2014). Contesting the value of “creating shared value”. California Management Review, 56(2), 130–153. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.2.130

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Crompton, J. L. (2014). Sponsorship for sport managers. FIT.

- Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113488126

- Dembek, K., Singh, P., & Bhakoo, V. (2016). Literature review of shared value: A theoretical concept or a management buzzword? Journal of Business Ethics, 137(2), 231–267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2554-z

- Demir, R., & Söderman, S. (2015). Strategic sponsoring in professional sport: A review and conceptualization. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(3), 271–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1042000

- Erhardt, N., Martin-Rios, C., & Chan, E. (2019). Value co-creation in sport entertainment between internal and external stakeholders. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(11), 4192–4210. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2018-0244

- Experian. (2019). Powering opportunities – Experian Annual Report 2019. http://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReports/PDF/LSE_EXPN_2019.pdf

- FIVB. (2019). Good Net Volleyball Sustainability Project launched on Copacabana Beach. http://www.fivb.org/en/FIVB/viewPressRelease.asp?No=80603&Language=en

- Gerke, A., Desbordes, M., & Dickson, G. (2015). Towards a sport cluster model: The ocean racing cluster in Brittany. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(3), 343–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1019535

- Grohs, R., & Reisinger, H. (2014). Sponsorship effects on brand image: The role of exposure and activity involvement. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 1018–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.008

- Gronroos, C. (1994). From marketing mix to relationship marketing: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Asia-Australia Marketing Journal, 2(1), 9–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1320-1646(94)70275-6

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis (1st Ed.). Sage.

- Horbel, C., Popp, B., Woratschek, H., & Wilson, B. (2016). How context shapes value co-creation: Spectator experience of sport events. The Service Industries Journal, 36(11-12), 510–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2016.1255730

- Horne, J. (2007). The four ‘knowns’ of sports mega-events. Leisure Studies, 26(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360500504628

- Horne, J. (2017). Sports mega-events–three sites of contemporary political contestation. Sport in Society, 20(3), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2015.1088721

- IEG. (2017). Sponsor survey reveals dissatisfaction with property partners. http://www.sponsorship.com/Report/2017/12/18/Sponsor-Survey-Reveals-Dissatisfaction-With-Proper.aspx

- Inoue, Y., Funk, D. C., & McDonald, H. (2017). Predicting behavioral loyalty through corporate social responsibility: The mediating role of involvement and commitment. Journal of Business Research, 75, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.02.005

- Inoue, Y., & Havard, C. T. (2014). Determinants and consequences of the perceived social impact of a sport event. Journal of Sport Management, 28(3), 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0136

- Ivens, B. S., Pardo, C., Salle, R., & Cova, B. (2009). Relationship keyness: The underlying concept for different forms of key relationship management. Industrial Marketing Management, 38(5), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2009.05.002

- Jensen, J. A., & Cobbs, J. B. (2014). Predicting return on investment in sport sponsorship: Modeling brand exposure, price, and ROI in Formula One automotive competition. Journal of Advertising Research, 54(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-54-4-435-447

- Jensen, J. A., Cobbs, J. B., & Turner, B. A. (2016). Evaluating sponsorship through the lens of the resource-based view: The potential for sustained competitive advantage. Business Horizons, 59(2), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2015.11.001

- Jensen, J. A., & Cornwell, T. B. (2017). Why do marketing relationships end? Findings from an integrated model of sport sponsorship decision-making. Journal of Sport Management, 31(4), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0232

- Johnston, M. A., & Spais, G. S. (2015). Conceptual foundations of sponsorship research. Journal of Promotion Management, 21(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2015.1021504

- de los Reyes, Jr. G., Scholz, M., & Smith, N. C. (2017). Beyond the “Win-Win” creating shared value requires ethical frameworks. California Management Review, 59(2), 142–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125617695286

- Kim, K., Byon, K. K., & Baek, W. (2020). Customer-to-customer value co-creation and co-destruction in sporting events. The Service Industries Journal, 40(9–10), 633–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1586887

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 256–270). Sage

- King, N. (2012). Doing template analysis. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges (pp. 426–450). Sage.

- Kirin. (2019). Our CSV committment. https://www.kirinholdings.co.jp/english/csv/commitment/

- Koenig-Lewis, N., Asaad, Y., & Palmer, A. (2018). Sports events and interaction among spectators: Examining antecedents of spectators’ value creation. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(2), 193–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1361459

- Lee, D., Moon, J., Cho, J., Kang, H. G., & Jeong, J. (2014). From corporate social responsibility to creating shared value with suppliers through mutual firm foundation in the Korean bakery industry: A case study of the SPC group. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(3), 461–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2014.929301

- Lin, Z., Yang, H., & Demirkan, I. (2007). The performance consequences of ambidexterity in strategic alliance formations: Empirical investigation and computational theorizing. Management Science, 53(10), 1645–1658. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1070.0712

- Maltz, E., & Schein, S. (2012). Cultivating shared value initiatives: A three Cs approach. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, (47), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2012.au.00005

- Manoli, A. E. (2020). Brand capabilities in English Premier League clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(1), 30–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1693607

- Mazodier, M., & Quester, P. (2014). The role of sponsorship fit for changing brand affect: A latent growth modeling approach. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2013.08.004

- Meehan, J., Meehan, K., & Richards, A. (2006). Corporate social responsibility: The 3C-SR model. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5/6), 386–398. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290610660661

- Meenaghan, T., & O’Sullivan, P. (2013). Metrics in sponsorship research – is credibility an issue? Psychology & Marketing, 30(5), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20615

- Mills, B. M., & Rosentraub, M. S. (2013). Hosting mega-events: A guide to the evaluation of development effects in integrated metropolitan regions. Tourism Management, 34, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.03.011

- Miragaia, D. A., Ferreira, J., & Ratten, V. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and social entrepreneurship: Drivers of sports sponsorship policy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 9(4), 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1374297

- Misener, L. (2015). Leveraging parasport events for community participation: Development of a theoretical framework. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(1), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2014.997773

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800302

- Müller, M. (2015). What makes an event a mega-event? Definitions and sizes. Leisure Studies, 34(6), 627–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.993333

- Müller, M. (2017). Approaching paradox: Loving and hating mega-events. Tourism Management, 63, 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.06.003

- New Statesman. (2019). English cricket only has itself to blame for the forgotten World Cup. https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/sport/2019/07/english-cricket-only-has-itself-blame-forgotten-world-cup

- O’Brien, D., & Chalip, L. (2007). Executive training exercise in sport event leverage. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 1(4), 296–304. https://doi.org/10.1108/17506180710824181

- O’Reilly, N., Lyberger, M., McCarthy, L., Séguin, B., & Nadeau, J. (2008). Mega-special-event promotions and intent to purchase: A longitudinal analysis of the Super Bowl. Journal of Sport Management, 22(4), 392–409. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.22.4.392

- Parent, M. M., Eskerud, L., & Hanstad, D. V. (2012). Brand creation in international recurring sports events. Sport Management Review, 15(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.08.005

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Two decades of developments in qualitative inquiry: A personal, experiential perspective. Qualitative Social Work, 1(3), 261–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325002001003636

- Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

- Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1/2), 62–77.

- Reinhardt, F., Stavins, R., & Vietor, R. (2008). Corporate social responsibility through an economic lens. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/ren008

- Ribeiro, T., Correia, A., Figueiredo, C., & Biscaia, R. (2020). The Olympic Games’ impact on the development of teachers: The case of Rio 2016 Official Olympic Education Programme. Educational Review, doi:10.1080/00131911.2020.1837739

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Gouthro, M. B., & Moital, M. (2018). Customer-to-customer co-creation practices in tourism: Lessons from customer-dominant logic. Tourism Management, 67, 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.02.010

- Robertson, R., Wenzel, L., Thompson, J., & Charles, A. (2017). Understanding NHS financial pressures. How are they affecting patient care? The King’s Fund, March 2017.

- Schönberner, J., Woratschek, H., & Buser, M. (2020). Understanding sport sponsorship decision-making – an exploration of the roles and power bases in the sponsors’ buying center. European Sport Management Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1780459

- Skarmeas, D., & Leonidou, C. N. (2013). When consumers doubt, watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1831–1838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.004

- Smith, A. (2009). Spreading the positive effects of major events to peripheral areas. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407960903204372

- Smith, A. (2014). Leveraging sport mega-events: New model or convenient justification? Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 6(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2013.823976

- Stieler, M., & Germelmann, C. C. (2018). Actor engagement practices and triadic value co-creation in the Team Sports Ecosystem. Marketing ZFP, 40(4), 30–43. https://doi.org/10.15358/0344-1369-2018-4-30

- Storbacka, K. (2019). Actor engagement, value creation and market innovation. Industrial Marketing Management, 80, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.04.007

- Storbacka, K., & Nenonen, S. (2011). Scripting markets: From value propositions to market propositions. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.06.038

- Tsiotsou, R. H. (2016). A service ecosystem experience-based framework for sport marketing. The Service Industries Journal, 36(11–12), 478–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2016.1255731

- Vargo, S. L. (2008). Customer integration and value creation: Paradigmatic traps and perspectives. Journal of Service Research, 11(2), 211–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670508324260

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0069-6

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

- Visser, W. (2013). Creating shared value: Revolution or clever con? Wayne Visser Blog Series, 17 June 2013.

- Walker, M., Hills, S., & Heere, B. (2017). Evaluating a socially responsible employment program: Beneficiary impacts and stakeholder perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 143(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2801-3

- Walzel, S., Robertson, J., & Anagnostopoulos, C. (2018). Corporate social responsibility in professional team sports organizations: An integrative review. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 511–530. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0227

- Woratschek, H., Horbel, C., & Popp, B. (2014a). The sport value framework – a new fundamental logic for analyses in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.865776

- Woratschek, H., Horbel, C., & Popp, B. (2014b). Value co-creation in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.866302

- Wu, J., Inoue, Y., Filo, K., & Sato, M. (2020). Creating shared value and sport employees’ job performance: The mediating effect of work engagement. European Sport Management Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1779327

- Yoshida, M. (2017). Consumer experience quality: A review and extension of the sport management literature. Sport Management Review, 20(5), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.01.002