ABSTRACT

Research question

According to past research, the effectiveness of athlete endorsements of advertised products is low on average and strongly depends on the context. This article extends the source attractiveness model to examine two research questions: (1) How do multiple unexplored types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness affect customer equity drivers? (2) How do these effects vary by the fit of an athlete endorser with the endorsed product and with the consumer’s gender and sports experience?

Research methods

This research uses hierarchical linear modeling of 1319 consumer evaluations of athlete-endorsed ads in Japan.

Results and finding

Among multiple types of an athlete’s attractiveness, an athlete’s success appeal, personality appeal, and athlete-product similarity, but not sex appeal, positively affect customer equity drivers. Due to gender roles, success appeal and personality appeal have stronger effects and athlete-product similarity has weaker effects for male athletes. Contrary to conventional wisdom, sex appeal is not more influential for female athletes. Reflecting sexual preferences in opposite-gender evaluations, a female athlete’s sex appeal has a stronger positive influence on male consumers, whereas a male athlete’s success appeal has a stronger positive influence on female consumers. A consumer’s sports experience enhances the influence of an athlete’s success appeal.

Implications

This research identifies a set of contextual moderators (athlete-product fit; athlete-consumer fit in gender and sports experience) of the effectiveness of different attractiveness types in athlete endorsements of advertised products. It provides guidelines on how to enhance the effectiveness of athlete endorsements by using different types of athlete attractiveness in different contexts.

Introduction

Marketing aims to enhance customer equity, which is the lifetime value of a firm’s customers and results from the customer equity drivers of value equity (i.e. consumer perceptions of product value), brand equity (i.e. consumer perceptions of brands), and retention equity (i.e. consumer intentions to (re-)purchase from a brand) (Zeithaml et al., Citation2001). Advertising is a key tool for improving these customer equity drivers. It induces beliefs about products and brands that enhance consumers’ attitudes and purchase intentions (Frank et al., Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Rust et al., Citation2004; Wimalachandra et al., Citation2014).

In sports marketing, firms use sponsorship deals and athlete endorsements of advertising products and services in order to influence these customer equity drivers. Many athletes and sports events are popular brands with a large fan base and a favorable image in society (Arai et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Carlson & Donavan, Citation2013; Chang et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2020). Through athlete endorsements and sponsorship, firms aim to benefit from public attention and to transfer the favorable image of an athlete or sports event to their advertised products and brands (Alexandris et al., Citation2012; Arai et al., Citation2013; Braunstein-Minkove et al., Citation2011; Carlson & Donavan, Citation2008; Cheong et al., Citation2019). However, athlete endorsements appear to be difficult to implement successfully. According to a meta-analysis (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017), the average athlete endorsement fails to improve customer attitudes and thus fails to pay off for the advertising firm. Rather, its success hinges on the choice of an ideal athlete endorser with the right characteristics.

In searching for an athlete endorser’s ideal characteristics, the literature draws on various theoretical frameworks, such as the source attractiveness model (McGuire, Citation1985). This model explains that a consumer feels attracted by three aspects of a communication source (e.g. an athlete endorser in an ad): likability, similarity, and familiarity. As dimensions of likability, the literature focuses on the influence of an athlete endorser’s sex appeal (i.e. likability of the body / physical attractiveness) on advertising effectiveness (Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000), but it neglects other dimensions. Moreover, in exploring types of similarity, research on the match-up hypothesis (Kahle & Homer, Citation1985; Kamins, Citation1990), which focuses on the match-up between athlete endorsers and various conditions, highlights the influence of similarity between the characteristics of an athlete endorser and an endorsed product on the effectiveness of advertising activities (Dees et al., Citation2010; Parker & Fink, Citation2012; Yoon et al., Citation2018).

Drawing on the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness (Hartz, Citation1996), we extend this source attractiveness model in order to help scholars and advertisers gain a better understanding of the distinct types of attractiveness that impact the advertising effectiveness of athlete endorsements. As dimensions of an athlete endorser’s likability, we examine not only the known effects of sex appeal, but also the hitherto unexplored effects of personality appeal (i.e. likability of personality) and success appeal (i.e. likability of sports achievements). Moreover, to help practitioners apply our insights to specific contexts, we explore how the advertising effectiveness of these distinct types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness varies by the fit (i.e. match-up) between the athlete’s and the consumer’s gender, between the athlete’s and the consumer’s sports experience, and between the athlete and the endorsed product. This choice of moderators extends research on the match-up hypothesis (Kamins, Citation1990). We examine these effects with hierarchical linear modeling of 1319 consumer evaluations of multiple athlete-endorsed ads in Japan.

Theoretical background

The advertising effectiveness of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness

The commercialization and media coverage of sports have transformed successful athletes into major brands (Arai et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Carlson & Donavan, Citation2013; Chang et al., Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2020). Since many consumers know, admire, trust, and identify with these athletes (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2013), firms seek to benefit from such favorable attitudes in order to market their products to consumers more successfully (Arai et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Frank & Enkawa, Citation2009; Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017). Firms thus sponsor athletes and involve them in their advertisements as endorsers of their products and services (Alexandris et al., Citation2012; Cheong et al., Citation2019; Dees et al., Citation2010). While the literature partially confirms the effectiveness of these activities (Braunstein-Minkove et al., Citation2011; Carlson & Donavan, Citation2008; Cheong et al., Citation2019), a meta-analysis (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017) suggests that athlete endorsements, on average, fail to achieve these advertising goals. However, athlete endorsements can be successful when selecting athletes with the right characteristics. To find these right characteristics, we extend the source attractiveness model to compare the influence of distinct types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness on the effectiveness of advertising activities.

The source attractiveness model (McGuire, Citation1985) posits that an endorser’s attractiveness enhances the effectiveness of an endorsed ad because consumers form positive stereotypes about attractive people, which consumers associate with the advertised product and brand. Rather than including overall attractiveness, this model conceptualizes different subjective perceptions of an endorser that may attract a consumer (Amos et al., Citation2008). These are likability (i.e. affection for the endorser), similarity (i.e. perceived resemblance of the endorser and the consumer), and familiarity (i.e. the consumer’s knowledge of the endorser). However, based on the match-up hypothesis about the behavioral consequences of similarity (i.e. match-up) between the endorser’s characteristics and various conditions, most research on athlete endorsements replaces athlete-consumer similarity with athlete-product similarity, which has been shown to be particularly influential (Braunstein-Minkove et al., Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011; Yoon et al., Citation2018). A major limitation of the source attractiveness model is that it does not measure any specific characteristics of an endorser. Hence, advertisers have difficulties in understanding which athlete to enlist as an endorser (Amos et al., Citation2008). Thus, studies on the effect of athlete attractiveness on advertising effectiveness directly test the effect of physical attractiveness (e.g. Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012), which is also referred to as sex appeal (Black & Morton, Citation2017) and is a sub-dimension of the likability dimension of the source attractiveness model.

summarizes the literature on the effects of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness on customer equity drivers. This literature explores only the effects of likability and its sub-dimension of sex appeal. Most studies use student samples with less than 360 participants. They find positive effects of an athlete endorser’s likability (Kim & Na, Citation2007; Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011) and sex appeal (Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Parker & Fink, Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000) on the customer equity drivers of brand attitude and purchase intent. By contrast, the only study not restricted to students fails to support an effect of sex appeal (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2017). In examining moderators of the influence of athlete attractiveness, the literature tests, but fails to support, a role of athlete expertise (Fink et al., Citation2004) and yields contradictory (positive, negative, or non-significant) findings on the role of sport-product fit (i.e. sports-related vs. other product) (Kim & Na, Citation2007; Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011; Till & Busler, Citation2000).

Table 1. Positioning of the literature on athlete endorsements in advertising: the role of athlete attractiveness.

To help advertisers select a specific athlete as an ideal endorser, we extend the source attractiveness model by including as subdimensions of likability not only sex appeal, but also personality appeal (i.e. likability of personality) and success appeal (i.e. likability of sports achievements). We compare their yet unexplored effects on various customer equity drivers to assess their advertising effectiveness. As a contribution to the literature on the match-up hypothesis (Kamins, Citation1990), we also examine the variation of these effects by the fit (i.e. match-up) between the athlete’s and the consumer’s gender, between the athlete’s and the consumer’s sports experience, and between the athlete and the endorsed product.

Extending the source attractiveness model: a psycho-socionomic perspective

The first objective of our study is to extend the source attractiveness model in order to guide advertisers in selecting an athlete endorser with the specific types of attractiveness that are most effective in advertising. Most research on attractiveness seeks to explain partner choice, where biological explanations for attractiveness perceptions play a dominant role (Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002). However, these theories only partially explain the nature and behavioral influence of celebrity endorsers of ads because consumers do not necessarily regard these celebrities as their prospective partners. Therefore, we draw on the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness (Hartz, Citation1996), which explicates both how the culture of a society influences the criteria for judging someone as attractive and how these criteria influence the benefits (e.g. excitement, social recognition) and costs (e.g. embarrassment) of associating oneself with persons that either meet these attractiveness criteria or not. Society tends to believe that persons with the traits which its culture regards as attractive (e.g. small talk ability) also share many other desirable attributes (e.g. competence, helpfulness, or competence). Such beliefs are exaggerated and not warranted by the objective benefits of these traits (Hartz, Citation1996). For a member of society, associating oneself with a carrier of these attractive traits thus leads to the expectation of various positive consequences for oneself (Hartz, Citation1996). Extending the theoretical foundation of the source attractiveness model (McGuire, Citation1985), this mechanism can explain why consumers seek to associate themselves with attractive celebrity endorsers through positive attitudes to, and purchases of, endorsed products. While the source attractiveness model (McGuire, Citation1985) conceptualizes different subjective perceptions of a person (e.g. an endorser) that may attract a consumer (i.e. perceptions of similarity, familiarity, and liking), it does not contain any specific characteristics underlying the person’s likability (Amos et al., Citation2008). We refer to these characteristics as different types of appeal.

These types of appeal can be classified broadly into sex appeal, personality appeal, and success appeal (Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002; Hartz, Citation1996). Both sex appeal and personality appeal lead to appreciation of the person’s physical and mental characteristics and induce the expectation of enjoying the attractive person’s presence. Personality appeal can also lead to persuasion and induce the expectation of guidance (Kenton, Citation1989; Whittaker, Citation1965). A person’s success appeal evokes both inspiration for one’s own future achievements and the expectation of improving one’s own status by associating oneself with the person (Berscheid, Citation1981; Figgins et al., Citation2016; Hartz, Citation1996). So far, the literature on celebrity and athlete endorsements in advertising focuses only on sex appeal (see ; Carlson & Donavan, Citation2008; Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Parker & Fink, Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000) and overlooks the roles of personality appeal and success appeal. To address this gap and guide advertisers in selecting an athlete endorser with particular characteristics, we compare the effects of an athlete endorser’s sex appeal, personality appeal, and success appeal on customer equity drivers.

The second objective of our study is to examine how the advertising effectiveness of different types of athlete endorser attractiveness varies by context. This would help an advertiser select an athlete endorser whose types of attractiveness are effective in the advertiser’s specific context. In choosing appropriate contextual moderators, we follow and extend the literature on the match-up hypothesis. It posits that an athlete endorser’s attractiveness has stronger effects when it matches contextual conditions, such as the endorsed product (Kim & Na, Citation2007; Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011; Till & Busler, Citation2000), although the empirical evidence is mixed (see ). Regarding the effectiveness of athlete attractiveness, the literature tests the match-up hypothesis only with measures of likability (i.e. overall appeal) and sex appeal (e.g. Liu et al., Citation2007; Till & Busler, Citation2000). We extend this literature by comparing the predictive accuracy of the match-up hypothesis across different types of athlete appeal: sex appeal, success appeal, and personality appeal. In examining the contextual variation in these effects of unexplored dimensions of attractiveness, we follow the literature in using athlete-product similarity as a moderator. This is the match-up between the characteristics of an athlete endorser and the endorsed product.

Moreover, based on the match-up hypothesis, we select the additional moderators of the fit (i.e. match-up) between the athlete’s and the consumer’s gender and the fit between the athlete’s and the consumer’s sports experience. Specifically, first, we investigate the variation of the effects of athlete appeal by athlete gender and athlete-consumer gender congruence because culturally formed gender role expectations may alter the importance of different types of appeal (Black & Morton, Citation2017; Eagly & Wood, Citation1999; Hartz, Citation1996). Hence, different gender role expectations for men and women may cause consumers to attach a different importance to different types of appeal in evaluating male athletes as compared to female athletes. Moreover, sexual preferences cause men and women to have amplified gender role expectations for the opposite gender (Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002). Therefore, in evaluating athlete endorsers that belong to the opposite gender rather than their own gender, consumers may attach a stronger importance to those types of athlete appeal that match their primary sexual preferences. Second, we seek to examine how the effects of an athlete endorser’s appeal vary by a consumer’s experience in the athlete’s sport because the attractiveness dimension of athlete success has greater inspirational power for consumers involved in the sport (Figgins et al., Citation2016; Vescio et al., Citation2005).

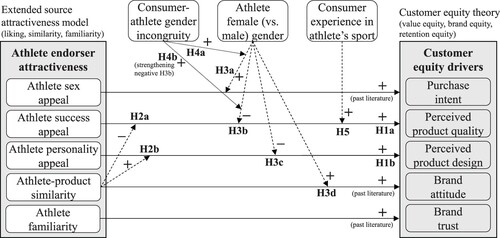

Our conceptual model (see ) summarizes our study about the effects of different types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness on multiple customer equity drivers (purchase intent, perceived product quality, perceived product design, brand attitude, and brand trust: Abulaiti et al., Citation2011; Ball et al., Citation2004; Frank & Enkawa, Citation2009; Herbas Torrico & Frank, Citation2019; Homburg et al., Citation2015; Kamolsook et al., Citation2019) and about the variation in these effects by the match-up in multiple contextual conditions.

Hypotheses

The influence of an athlete endorser’s appeal on customer equity drivers

Advertising endorsements of ads work by transferring a celebrity’s attractive image to an advertised product or brand, which improves the consumer’s attitudes toward the advertised product or brand (Erdogan, Citation1999; McCracken, Citation1989). This attractive image derives from the celebrity’s sex appeal, success appeal, and personality appeal (Bjelica et al., Citation2016; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002; Hartz, Citation1996).

Athlete sex appeal

An athlete’s sex appeal refers to the perception that looking at the athlete’s body leads to sensual gratification (Bjelica et al., Citation2016; Black & Morton, Citation2017; Fink et al., Citation2004; Ohanian, Citation1990). Using student samples, several studies confirm a positive effect of athlete sex appeal on customer equity drivers (Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Parker & Fink, Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000), whereas one study using a more general sample fails to confirm such an effect (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2017). Drawing on the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness (Hartz, Citation1996), we explain this predominantly positive effect by presuming that consumers associate themselves with an athlete having an attractive body to obtain sensual gratification and to signal to others a sensually gratifying self-image. Consumers form such associations with an athlete endorser by forming favorable attitudes and intentions toward endorsed products and brands (McCracken, Citation1989), which enhance a firm’s customer equity drivers (Zeithaml et al., Citation2001). Compared to the abundance of research on sex appeal, no study so far explores the effects of success appeal and personality appeal on customer equity drivers.

Athlete success appeal

An athlete’s success appeal represents the sports achievements that form the basis of the athlete’s fame, inspirational power, and status in society (Figgins et al., Citation2016). In particular, the athlete’s ability to inspire others to engage in hard work and the athlete’s discipline in pursuing success differentiate an athlete endorser from other types of celebrity endorsers (Braunstein & Zhang, Citation2005). According to the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness, consumers would wish to associate themselves with an athlete as a carrier of attractive traits in expectation of positive consequences that result from these attractive traits (Hartz, Citation1996; McGuire, Citation1985). Such an association can operate through the formation of favorable attitudes and purchase intentions toward an endorsed product or brand (McCracken, Citation1989). For consumers, a positive consequence of associating themselves with a successful athlete may be inspiration, which motivates them to work hard, maintain hope, and abstain from giving up in the pursuit of their own goals (Figgins et al., Citation2016). Another positive consequence may be to transfer the athlete’s status in society to themselves in order to feel, and signal to others, status-related superiority (McCracken, Citation1989). Thus, we posit that an athlete endorser’s success appeal causes consumers to associate themselves with the athlete by forming favorable attitudes and intentions toward the endorsed product or brand, which reflects improved customer equity drivers (Zeithaml et al., Citation2001).

H1a: An athlete endorser’s success appeal has a positive effect on customer equity drivers.

Athlete personality appeal

An athlete’s personality appeal refers to a favorable image caused by the athlete’s various personality traits matching societal ideals (Amos et al., Citation2008; Braunstein & Zhang, Citation2005; Erdogan, Citation1999). Our focus on personality appeal differs from the focus of many studies on a celebrity endorser’s credibility, which is merely one out of many traits of an attractive personality and influences endorsement outcomes through a different mechanism (Amos et al., Citation2008; Ohanian, Citation1990). Like sex appeal, personality appeal causes consumers to enjoy the presence of the athlete, whereas athlete success induces inspiration and status. Based on the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness (Hartz, Citation1996), we posit that consumers associate themselves with an athlete having an attractive personality in order to obtain enjoyment and signal to others an enjoyable and sociable self-image. Moreover, consumers may identify with attractive personality traits, seek to develop such personality traits themselves, and intend to signal an association with such personality traits to others. Since consumers pursue such associations through favorable reactions to athlete endorsements (McCracken, Citation1989), we posit that an athlete endorser’s personality appeal improves consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward the endorsed product or brand, which reflects improved customer equity drivers (Zeithaml et al., Citation2001).

H1b: An athlete endorser’s personality appeal has a positive effect on customer equity drivers.

Effects of athlete appeal on customer equity drivers: variation by athlete-product similarity

Research on the match-up hypothesis provides evidence for a moderating role of the product context on the effect of an athlete endorser’s appeal on customer equity drivers. Specifically, studies show that a match-up between the purpose of the endorsed product and either the athlete’s sport (Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011) or the athlete’s sex appeal (Till & Busler, Citation2000) has a positive effect on customer equity drivers. A different version of the match-up hypothesis shows that a match-up between the athlete’s credibility, which derives from an athlete’s personality appeal (Kenton, Citation1989), and athlete-product similarity, which refers to the similarity between the athlete’s image and product characteristics, enhances customer equity drivers (Lee & Koo, Citation2015). Building on this latter type of match-up and the psycho-socionomic theory of attractiveness (Hartz, Citation1996), we argue that consumers who are attracted by, and may thus identify with, an athlete’s personality are more likely to pursue an association with a product that the athlete can credibly represent through similar characteristics such as shared values or a similar image. Therefore, we posit that athlete-product similarity enhances the effect of an athlete endorser’s personality appeal on customer equity drivers (H2b). While the credibility of personality traits differs by context (Lee & Koo, Citation2015), the credibility of success is more universal because success signals competence and more success is always preferable to low success (Kouzes & Posner, Citation1990). Success appeal may thus bridge the lack of credibility associated with an athlete endorser’s other types of appeal when athlete-product similarity is low. Hence, when athlete-product similarity is low, an athlete endorser’s success appeal may play a primary role in encouraging consumers to seek associations with the athlete through products (H2a).

H2a: When athlete-product similarity is lower, an athlete endorser’s success appeal has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers.

H2b: When athlete-product similarity is higher, an athlete endorser’s personality appeal has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers.

Effects of athlete appeal on customer equity drivers: variation by athlete gender

Due to the gender roles ingrained in the culture of a society, the society’s members regard distinct types of appeal as important in evaluating men and women (Bjelica et al., Citation2016; Black & Morton, Citation2017; Eagly & Wood, Citation1999; Hartz, Citation1996). This difference might extend to the evaluation of male and female athlete endorsers, which studies focusing purely on female athletes assume without testing it (Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012). According to the gender roles prevalent in most countries, men tend to be evaluated more based on their career success and personality, whereas women tend to be evaluated more based on the pleasant appearance of their body (Bjelica et al., Citation2016; Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Eagly & Wood, Citation1999). As argued by Kenton (Citation1989) and Whittaker (Citation1965), this greater focus on a man’s success and personality may also cause men to be considered more persuasive and credible than women. Moreover, gender roles tend to include a certain expectation for men to stand out and challenge rules, whereas women tend to be more expected to fit in and comply with rules (Holmes, Citation2013).

Such gender differences may equally apply to evaluations of athlete endorsers because consumers likely adopt these culturally ingrained gender roles in forming their own expectations of the psychological and social benefits of associating themselves with male and female athletes. Therefore, we predict that an athlete endorser’s sex appeal has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers for female athletes than for male athletes (H3a), whereas an athlete endorser’s success appeal (H3b) and personality appeal (H3c) have stronger effects on customer equity drivers for male athletes than for female athletes. Moreover, men tend to be under a certain expectation to stand out, go against conventions, and challenge rules (Holmes, Citation2013). We thus posit that male endorsers are more effective than female endorsers in situations of low athlete-product similarity (H3d), where athlete endorsements (Lee & Koo, Citation2015), and celebrity endorsements in general (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017), are usually less effective. By contrast, fitting in with all conventions may take away some of a male endorser’s appeal and may thus weaken the benefits of high athlete-product similarity.

H3a: An athlete endorser’s sex appeal has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers for female athletes than for male athletes.

H3b: An athlete endorser’s success appeal has a weaker effect on customer equity drivers for female athletes than for male athletes.

H3c: An athlete endorser’s personality appeal has a weaker effect on customer equity drivers for female athletes than for male athletes.

H3d: Athlete-product similarity has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers for female athlete endorsers than for male athlete endorsers.

Effects of athlete appeal on customer equity drivers: variation by consumer-athlete gender incongruity

Sexual preferences amplify certain gender role expectations regarding members, and potentially also athlete endorsers, of the opposite gender (Buss, Citation1989; Eagly & Wood, Citation1999). In evaluations of the opposite gender, women tend to attach a greater importance to career success, whereas men tend to attach a greater importance to sex appeal (Bjelica et al., Citation2016; Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002; Eagly & Wood, Citation1999). In same-gender evaluations, these gender role expectations are strongly attenuated (Leaper, Citation1995). Thus, we posit that consumer-athlete gender incongruity (i.e. evaluations of athletes with the opposite gender) inflates the hypothesized gender difference between a male athlete and a female athlete in the advertising effectiveness of this athlete endorser’s sex appeal (H3a) and success appeal (H3b).

H4a: Consumer-athlete gender incongruity enhances the hypothesized gender difference (H3a) between male and female athlete endorsers in the effect of this athlete’s sex appeal on customer equity drivers.

H4b: Consumer-athlete gender incongruity enhances the hypothesized gender difference (H3b) between male and female athlete endorsers in the effect of this athlete’s success appeal on customer equity drivers.

Effects of athlete appeal on customer equity drivers: variation by athlete-consumer sport congruity

Athletes can have a different meaning and relevance to consumers involved in sports as opposed to others (Beaton et al., Citation2011; Vescio et al., Citation2005). Consequently, a consumer’s experience in an athlete endorser’s sport may alter the degree to which the athlete’s characteristics influence the consumer’s formation of attitudes and intentions. We posit that sports experience causes a consumer to consider the sports-internal status and inspirational power that arise from athlete success (Figgins et al., Citation2016; Vescio et al., Citation2005) more important for two reasons. First, the consumer is more likely to have accepted the athlete as a role model in practicing the athlete’s sport (Beaton et al., Citation2011; Vescio et al., Citation2005). Second, experience in a sport increases the consumer’s knowledge of the difficulty in achieving success in this sport (Beaton et al., Citation2011). This may strengthen the consumer’s perception of the athlete’s status and inspirational power, which would affect the consumer’s behavior. By contrast, sports experience is not likely to moderate the effects of an athlete endorser’s sex appeal and personality appeal, which are not relevant to the consumer’s sport-related goals, except for particular sports aimed at enhancing one’s sex appeal (e.g. aerobics, bodybuilding) or personality appeal (e.g. chess, skydiving).

H5: An athlete endorser’s success appeal has a stronger effect on customer equity drivers for consumers with experience in the athlete’s sport than for consumers without such experience.

Methodology

Survey on perceptions of athlete-endorsed commercials

To test our hypotheses, we conducted an online survey in Japan during December 2019. We chose Japan because of its large economic relevance to sports marketing and because its culture has a clear division of gender roles (Abulaiti et al., Citation2011; Hofstede et al., Citation2010), which provides fertile ground for testing our gender-related hypotheses (H3a/b/c/d, H4a/b). In order to minimize any context-specific bias and to generalize the results, the participants were shown four commercials. To enhance the realism and external validity of our study, we used commercials that are actually aired on television and on video platforms. Two commercials featured a famous female athlete, and two featured a famous male one. To minimize affordability and familiarity biases, we chose commercials that advertised relatively low-priced, and thus affordable, products for daily use (detergent, a polo shirt, beer, and vegetables) from well-known, and thus familiar, brands. We collected data only from consumers that confirmed their knowledge of the featured athletes and products. Directly after watching each of these commercials, the participants were asked to respond to questions that measured the constructs of our conceptual framework on reflective, 5-point Likert-type scales. Online Appendix A summarizes our measures and their literature sources.

Data collection and sample

We collected data by posting a link to the online survey in different mailing groups, online forums, and social networks across the country in order to reach a broadly diversified sample representative of online-affine Japanese consumers who realistically may have watched the chosen commercials on online media platforms themselves. Our final sample consists of 1319 consumer evaluations of athlete-endorsed commercials, provided by 331 consumers, who each evaluated up to four commercials. The sample has a relatively even distribution across men and women and has an age range from the 20s to 70s. presents the descriptive statistics and correlations of our constructs for the sample pooled across the four commercials. Corresponding to our choice of famous athletes, these statistics indicate high levels of athlete familiarity and athlete success appeal.

Table 2. Correlations, descriptive statistics, and validity statistics of constructs.

Tests of data validity

Response bias

A comparison of early and late respondents’ characteristics, using the time stamp of our online survey, does not indicate any systematic differences in sample structure or attitudes. Thus, non-response bias may not be a major problem in our study (Armstrong & Overton, Citation1977).

Common method variance (CMV)

To prevent problems of CMV, we combined different types of data for testing hypotheses H3 to H5. Specifically, we measured our independent variables with Likert-type scales, but our moderating variables with objective attributes of the athlete (experimental manipulation) and consumer (determined in the past). In order to estimate the degree of CMV in our tests of the remaining hypotheses (H1-H2), we followed the guidelines by Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001). They argue that the smallest positive correlation among theoretically unrelated constructs is an upper bound on CMV and that the degree of CMV among theoretically positively related constructs tends to be even lower. The smallest item-to-item correlation in our dataset is .06 for two theoretically positively related constructs (item 1 of athlete familiarity, item 2 of purchase intent), indicating that the upper bound on CMV would be even lower. Hence, CMV is unlikely to bias the conclusions to be drawn from our study.

Convergent and discriminant validity

The results of a confirmatory factor analysis satisfy the acceptance thresholds of χ2/df < 5, CFI ≥ .95, RMSEA ≤ .07, and upper bound of 90% RMSEA confidence interval ≤ .1 (Hair et al., Citation2010): χ2/df = 4.90 (df = 360), CFI = .96, RMSEA = .05, upper bound of 90% RMSEA confidence interval = .06. In addition, our multi-item measures fulfill the criteria of convergent and discriminant validity of Cronbach’s α > .7, composite reliability > .7, average variance extracted (AVE) > .5, and AVE > shared variance with other constructs (see , Hair et al., Citation2010).

Results

Hypothesis tests

Type of analysis

Since each respondent evaluated multiple ads, we analyzed our data using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) with 1319 consumer evaluations of ads at level 1 and 331 consumers at level 2. We repeated the same analysis for different customer equity drivers as the dependent variable: purchase intent, perceived product quality, perceived product design, brand attitude, and brand trust. As control variables, we included athlete female (vs. male) gender (1: female; 0: male), consumer-athlete gender incongruity (1: consumer gender ≠ athlete gender; 0: consumer gender = athlete gender), the two-way interaction of these variables, consumer age, and consumer experience in the athlete’s sport (1: yes; 0: no). As independent effect variables, we included the dimensions of our extended source attractiveness model: athlete sex appeal, athlete success appeal (H1a), athlete personality appeal (H1b), athlete-product similarity, and athlete familiarity. To test our hypotheses on moderating effects, we included the two-way interactions of athlete attractiveness types (athlete sex appeal, athlete success appeal, athlete personality appeal, and athlete-product similarity) with athlete gender (H3a-d) and consumer sports experience (H5). We also included the two-way interactions of an athlete’s success appeal and personality appeal with athlete-product similarity (H2a-b). Moreover, we included three-way interactions between athlete attractiveness types (athlete sex appeal, athlete success appeal), athlete gender, and athlete-consumer gender incongruity (H4a-b). We calculated the interaction terms after standardizing all variables. In addition, the HLM models include an intercept and level-specific error terms. For each dependent variable, we conducted an HLM analysis with all independent variables (full model), followed by another analysis after backward selection, where we iteratively removed non-significant effects one-by-one except for the control variables, which we kept in the model to ensure comparability across sample segments. We also did not remove non-significant main effects of variables involved in significant interaction effects. Since all variance inflation factors are well below 5, multi-collinearity is not an issue (Mason & Perreault, Citation1991).

Results

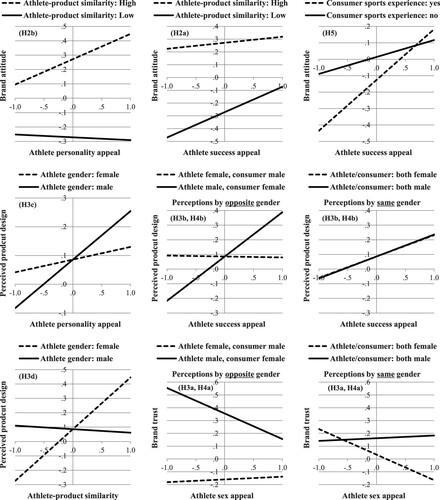

presents the results of our hypothesis tests, and visualizes the moderating effects, whereas Online Appendix B describes the results of robustness tests and additional analyses. The pseudo R2 values (Kreft & de Leeuw, Citation1998) range between 36% and 44%, which indicates a large effect of athlete endorser attractiveness on customer equity drivers. Our results vary slightly by the type of customer equity driver, but they show common tendencies. Regarding the control variables, consumer age negatively affects almost all customer equity drivers (except for perceived product design), which may imply a weaker susceptibility to athlete endorsements for elderly consumers. Using a female athlete endorser translates into stronger purchase intent (i.e. retention equity), whereas using a male athlete endorser improves perceived product quality, brand attitude, and brand trust (i.e. value equity; brand equity: Zeithaml et al., Citation2001). Consumer experience in the athlete’s sport exerts inconsistent and marginally significant (two-sided p < .1) or non-significant effects on customer equity drivers.

Table 3. The influence of the dimensions of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness on customer equity.

Regarding the main effects of athlete attractiveness types, athlete sex appeal has a negative influence on brand trust and no influence on the other types of customer equity drivers. Athlete success appeal (supporting H1a), athlete personality appeal (supporting H1b), and athlete-product similarity have positive effects on all customer equity drivers. Athlete familiarity has positive effects only on perceived product quality (marginally significant at two-sided p < .1, not retained in the final model after backward selection), perceived product design, and brand trust. Among these variables, athlete-product similarity has the strongest effect on customer equity drivers, followed by success appeal and personality appeal.

Testing our extended match-up hypothesis, we find that athlete personality appeal has stronger effects on customer equity drivers when athlete-product similarity is higher (supporting H2b). In partial support of H2a, athlete success appeal has stronger effects on the customer equity drivers of purchase intent, perceived product quality (marginally significant at two-sided p < .1; i.e. one-sided p < .05 for our one-sided hypothesis), and brand attitude when athlete-product similarity is lower (see ).

Regarding the influence of gender roles on the effects of athlete attractiveness, we find that the effects of athlete success appeal on customer equity drivers are weaker (supporting H3b) and the effects of athlete-product similarity (supporting H3d) are stronger for female athletes than for male athletes. In partial support of H3c, athlete personality appeal has a stronger effect on perceived product design for male athletes than for female athletes. The effect of sex appeal does not differ by athlete gender (not supporting H3a). We even find that sex appeal has a more negative effect (two-sided p < .1) on brand trust for female athletes, but this gender difference is not retained after backward selection.

Furthermore, we explore whether gender role perceptions tied to the sexual preferences of the opposite gender enhance the gender differences in the effects of athlete attractiveness. We find that the hypothesized gender difference in the effects of athlete sex appeal (H3a) on the customer equity drivers of perceived product design and brand trust is stronger when judged by consumers whose gender is opposite to the athlete’s gender (partially supporting H4a). Likewise, the hypothesized gender difference in the effects of athlete success appeal (H3b) on purchase intent, perceived product design, and brand trust (two-sided p < .1, one-sided p < .05) is stronger when judged by consumers whose gender is opposite to the athlete’s gender (partially supporting H4b).

Finally, we explore whether athlete-consumer sport fit alters the importance of athlete attractiveness types. In partial support of H5, we find that the effect of athlete success appeal on brand attitude is stronger for consumers experienced in the athlete’s sport than for consumers without such experience.

Mediation of supported effects

Across the customer equity drivers, we find consistent support for H1a/b, H2b, and H3b/d; less consistent support for H2a, H3c, H4a/b, and H5; and no support for H3a. At the same time, the customer equity drivers of value equity (perceived product/design quality) and brand equity (brand attitude/trust) all influence retention equity (purchase intent) directly (all effects significant except for the effect of brand trust) and indirectly via brand attitude (all effects significant). Thus, value equity and brand equity mediate the hypothesized main and moderating effects, which we confirmed with analyses of mediation and moderated mediation (Muller et al., Citation2005). Hence, all supported effects of eventually influence the final outcome variable of purchase intent, either directly or through mediation by its antecedents. Consequently, all hypotheses except H3a find support in our data.

Discussion

Short summary

Athlete endorsements in advertising are ineffective unless the athletes have certain ideal characteristics (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017). Our study searches for these ideal characteristics by comparing the effects of multiple types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness. To identify the contingencies of these effects, we also examine their variation by the athlete’s fit with the product and with the consumer’s gender and sports experience. Our analyses of 1319 consumer evaluations of athlete-endorsed ads confirm all hypotheses but H3a. An athlete endorser’s success appeal (H1a), personality appeal (H1b), and athlete-product similarity, but not sex appeal, positively affect customer equity drivers. As the result of gender roles, personality appeal (H3c) and success appeal (H3b) have stronger effects for male athletes, whereas athlete-product similarity (H3d), but not sex appeal (H3a not supported), is more influential for female athletes. Reflecting sexual preferences in opposite-gender evaluations, a female athlete’s sex appeal has a stronger positive influence on male consumers (H4a), whereas a male athlete’s success appeal has a stronger positive influence on female consumers (H4b). Consumer sports experience enhances the influence of an athlete’s success appeal (H5).

Theoretical implications

Our research extends the source attractiveness model (McGuire, Citation1985) in the context of athlete endorsements in advertising. This model captures only whether, but not why (i.e. based on what characteristics), consumers like an information source (e.g. an athlete endorser), which makes it difficult for advertisers to understand which athlete to enlist as an endorser. To overcome this limitation, we replace the liking construct of this model by three types of attractiveness: sex appeal, personality appeal, and success appeal. We find that only personality appeal and success appeal, but not sex appeal, influence an average consumer’s attitudes and intentions. While most (Fink et al., Citation2004, Citation2012; Parker & Fink, Citation2012; Till & Busler, Citation2000), but not all (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2008), studies find positive effects of an athlete endorser’s sex appeal on consumer attitudes and intentions (see ), our study implies that such affirmatory findings may result from an omitted variable bias. When including only sex appeal as a predictor, such as in our correlation matrix (see ), sex appeal appears to have a positive effect on customer equity drivers. However, when adding personality appeal and success appeal, the effect of sex appeal turns non-significant. Therefore, the results of past research might attribute a greater importance to sex appeal than is justified. Especially for female consumers, we even find that an athlete endorser’s sex appeal negatively affects brand trust, which corresponds to a hypothesis developed, but not supported, by Bower and Landreth (Citation2001). Other studies prematurely discount the effectiveness of an endorser’s attractiveness, based on only a measure of sex appeal (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2017), although the omitted types of personality appeal and success appeal might be effective.

Moreover, we extend the literature on the match-up hypothesis, which posits that an athlete-product match-up enhances the effects of an athlete endorser’s appeal on customer equity drivers (Till & Busler, Citation2000). To this end, we examine how the effects of different types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness vary by the athlete’s match-up or fit with the endorsed product and with the consumer’s gender and sports experience.

Regarding the athlete-product match-up, the literature reports that an athlete endorser’s sex appeal is more effective for beauty products (Till & Busler, Citation2000) and that an athlete’s overall appeal (i.e. likability) is more effective for sports-related products (Liu et al., Citation2007; Liu & Brock, Citation2011; no support: Kim & Na, Citation2007). As an extension, we show that athlete personality appeal is more effective even for non-sports and non-beauty products when the consumer perceives a similarity between product characteristics and the athlete’s image. Moreover, while scholars argue that athlete-product similarity is always beneficial for leveraging the appeal of an athlete endorser, we find that it reduces the effects of an athlete endorser’s success appeal, which is more effective when athlete-product similarity is low. Our finding thus implies that advertisers can use athlete endorsements in both match-up and non-match-up situations, but they may need to choose athletes with a different type of primary attractiveness.

Regarding the athlete-consumer gender match-up, we find that sexual preferences (Black & Morton, Citation2017; Buss, Citation1989; Buunk et al., Citation2002) in evaluations of opposite-gender athletes cause male consumers to be slightly influenced by a female athlete’s sex appeal and cause female consumers to be influenced more strongly by a male athlete’s success appeal. Moreover, regarding athlete gender in general, we find that the effects of success appeal and personality appeal are higher for male athletes than for female athletes and that athlete-product similarity is less important for male athletes than for female athletes, likely since gender roles permit, or somewhat expect, men to stand out and challenge conventions (Holmes, Citation2013).

Regarding the athlete-consumer sport match-up, we find that a consumer’s experience in the athlete endorser’s sport enhances the effect of this endorser’s athletic success appeal, which likely becomes more inspiring, on customer equity drivers. By contrast, such experience does not alter the importance of appeal types unrelated to sport (i.e. sex and personality appeal). At the same time, the cumulative number of years of practicing any sport weakens the effect of athlete success appeal on customer equity drivers. It may raise a consumer’s standard of comparison by making athletic performance appear more normal and less impressive.

Practical implications

Many firms use athletes as endorsers of advertised products because they believe that such endorsements help them achieve their advertising goals. However, a meta-analysis (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017) of the past literature shows that most athlete endorsements are ineffective unless firms choose certain athlete endorsers with the right characteristics for a specific purpose. Our article aims to inform advertisers on which types of an athlete endorser’s attractiveness are effective in different situations.

First, our research suggests that the widespread choice of a sexually attractive athlete endorser is ineffective, and is even harmful in building brand credibility among female consumers. Rather, we advise firms to choose athlete endorsers who are particularly successful and have an attractive personality.

Second, many firms use an athlete endorser whose image matches the characteristics of the endorsed product. While our study confirms the effectiveness of this choice, it also shows that this choice changes the type of athlete attractiveness most effective for advertising. For athlete endorsers that fit the endorsed product closely (e.g. a basketball player endorsing basketball shoes), we advise firms to choose an athlete endorser with an attractive personality, whereas the benefits of choosing a particularly successful athlete are limited. By contrast, for athlete endorsers that do not fit the endorsed product closely (e.g. a basketball player endorsing health insurance), we advise firms to choose a particularly successful athlete, whereas choosing an athlete endorser with an attractive personality has almost no marketing benefits.

Third, when aiming to enhance the consumer’s trust in the brand and in product quality and thus to weaken the consumer’s perception of risk, firms are advised to choose a male, rather than female, athlete endorser. By contrast, when seeking to improve consumer perceptions unrelated to credibility, such as product design perceptions, male and female athletes appear to have the same benefits. We advise firms to choose a female, rather than male, athlete when aiming to increase consumers’ purchase intentions.

Fourth, when choosing a male athlete endorser, firms are advised to choose a particularly successful athlete with an attractive personality, whereas the choice of a sexually attractive male athlete is ineffective, and may even harm female consumers’ trust in the brand. When choosing a female athlete endorser, the most important choice criterion is that these female athletes closely fit the characteristics of the endorsed product. Success and an attractive personality are also beneficial, but secondary in importance. While many firms appear to enlist sexually attractive female athlete endorsers or portray them as sexually attractive in their ads (Fink, Citation2015), we discourage this choice as it appears to be ineffective and may even reduce female consumers’ trust in the brand.

These practical implications for advertisers are equally important for athletes and athlete agencies eyeing endorsement deals because their revenues from advertisers depend on these athletes’ prospective advertising effectiveness as endorsers. In particular, we recommend that athletes strategically plan the intended societal perception of their attractiveness and build this perception in interviews and social media. Male athletes are advised to leave an impression of having an attractive personality in line with societal ideals and to emphasize their athletic success. Contrary to conventional wisdom, female athletes do not seem to benefit much from emphasizing their sex appeal, except slightly when targeting a male audience. Rather, female athletes appear to benefit strongly from conformity with expectations and thus both from focusing their choice of endorsement deals on those that match their own image and from adapting their appearance and behavior to the expected image that matches an advertised product.

Limitations and directions for future research

Our study has several limitations. It does not use data from multiple countries, which may limit the ability to generalize its results to cultures with different gender roles and different standards for judging an athlete’s attractiveness. Future research may seek to examine whether other cultures more tolerant to sexualized portrayals of women detect stronger effects of female sex appeal on customer equity drivers.

We find a stronger effect on consumer purchase intentions for female athlete endorsers than for male ones. This contradicts the dominant opinion in the field (Knoll & Matthes, Citation2017). Thus, we recommend that future research controls for athlete attractiveness when comparing the effectiveness of female and male athlete endorsers to avoid uneven comparisons and to identify contexts where female athletes are more effective. Since female athletes continue to represent a major share of product endorsements in advertising, advertisers’ assumptions about female athletes’ effectiveness might not be all wrong. Moreover, our study finds a negative effect of an endorser’s sex appeal on brand trust, which Bower and Landreth (Citation2001) hypothesize, but fail to confirm for fashion models as endorsers. Hence, we recommend that future research examines in detail how sex appeal affects credibility and how this effect varies by context.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (341.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors extend their gratitude to all survey respondents, and to three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abulaiti, G., Frank, B., Enkawa, T., & Schvaneveldt, S. J. (2011). How should foreign retailers deal with Chinese consumers? A cross-national comparison of the formation of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Channels, 18(4), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046669X.2011.613323

- Alexandris, K., Tsiotsou, R. H., & James, J. D. (2012). Testing a hierarchy of effects model of sponsorship effectiveness. Journal of Sport Management, 26(5), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.5.363

- Amos, C., Holmes, G., & Strutton, D. (2008). Exploring the relationship between celebrity endorser effects and advertising effectiveness. International Journal of Advertising, 27(2), 209–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2008.11073052

- Arai, A., Ko, Y. J., & Kaplanidou, K. (2013). Athlete brand image: Scale development and model test. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(4), 383–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.811609

- Arai, A., Ko, Y. J., & Ross, S. (2014). Branding athletes: Exploration and conceptualization of athlete brand image. Sport Management Review, 17(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.04.003

- Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14(3), 396–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377701400320

- Ball, D., Coelho, P. S., & Machás, A. (2004). The role of communication and trust in explaining customer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 38(9/10), 1272–1293. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560410548979

- Beaton, A. A., Funk, D. C., Ridinger, L., & Jordan, J. (2011). Sport involvement: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport Management Review, 14(2), 126–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.07.002

- Berscheid, E. (1981). An overview of the psychological effects of physical attractiveness and some comments upon the psychological effects of knowledge of the effects of physical attractiveness. In G. W. Lucker, K. Ribbens, & J. A. McNamara (Eds.), Psychological aspects of facial form (Monograph #11, Craniofacial Growth Series, pp. 1–23). Center for Human Growth and Development.

- Bjelica, D., Gardašević, J., Vasiljević, I., & Popović, S. (2016). Ethical dilemmas of sport advertising. Sport Mont, 14(3), 41–43.

- Black, I. R., & Morton, P. (2017). Appealing to men and women using sexual appeals in advertising: In the battle of the sexes, is a truce possible? Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(4), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2015.1015108

- Bower, A. B., & Landreth, S. (2001). Is beauty best? Highly versus normally attractive models in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2001.10673627

- Braunstein, J. R., & Zhang, J. J. (2005). Dimensions of athletic star power associated with Generation Y sports consumption. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 6(4), 37–62. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-06-04-2005-B006

- Braunstein-Minkove, J. R., Zhang, J. J., & Trail, G. T. (2011). Athlete endorser effectiveness: Model development and analysis. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 1(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1108/20426781111107199

- Buss, D. M. (1989). Toward an evolutionary psychology of human mating. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00024274

- Buunk, B. P., Dijkstra, P., Fetchenhauer, D., & Kenrick, D. T. (2002). Age and gender differences in mate selection criteria for various involvement levels. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00018

- Carlson, B. D., & Donavan, D. T. (2008). Concerning the effect of athlete endorsements on brand and team related intentions. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 17(3), 154–162.

- Carlson, B. D., & Donavan, D. T. (2013). Human brands in sport: Athlete brand personality and identification. Journal of Sport Management, 27(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.3.193

- Carlson, B. D., & Donavan, D. T. (2017). Be like Mike: The role of social identification in athlete endorsements. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 26(3), 176–191.

- Chang, Y., Ko, Y. J., & Carlson, B. D. (2018). Implicit and explicit affective evaluations of athlete brands: The associative evaluation–emotional appraisal–intention model of athlete endorsements. Journal of Sport Management, 32(6), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2017-0271

- Cheong, C., Pyun, D. Y., & Leng, H. K. (2019). Sponsorship and advertising in sport: A study of consumers’ attitude. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(3), 287–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1517271

- Dees, W., Bennett, G., & Ferreira, M. (2010). Personality fit in NASCAR: An evaluation of driver-sponsor congruence and its impact on sponsorship effectiveness outcomes. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 19(1), 25–35.

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (1999). The origins of sex differences in human behavior: Evolved dispositions versus social roles. American Psychologist, 54(6), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.6.408

- Erdogan, B. Z. (1999). Celebrity endorsement: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(4), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725799784870379

- Figgins, S. G., Smith, M. J., Sellars, C. N., Greenlees, I. A., & Knight, C. J. (2016). “You really could be something quite special”: A qualitative exploration of athletes’ experiences of being inspired in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 24, 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.01.011

- Fink, J. S. (2015). Female athletes, women’s sport, and the sport media commercial complex: Have we really “come a long way, baby”? Sport Management Review, 18(3), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.05.001

- Fink, J. S., Cunningham, G. B., & Kensicki, L. J. (2004). Using athletes as endorsers to sell women’s sport: Attractiveness vs. expertise. Journal of Sport Management, 18(4), 350–367. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.18.4.350

- Fink, J. S., Parker, H. M., Cunningham, G. B., & Cuneen, J. (2012). Female athlete endorsers: Determinants of effectiveness. Sport Management Review, 15(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.01.003

- Frank, B., & Enkawa, T. (2009). Economic influences on customer satisfaction: An international comparison. International Journal of Business Environment, 2(3), 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2009.023795

- Frank, B., Enkawa, T., & Schvaneveldt, S. J. (2014a). How do the success factors driving repurchase intent differ between male and female customers? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-013-0344-7

- Frank, B., Herbas Torrico, B., Enkawa, T., & Schvaneveldt, S. J. (2014b). Affect versus cognition in the chain from perceived quality to customer loyalty: The roles of product beliefs and experience. Journal of Retailing, 90(4), 567–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.08.001

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

- Hartz, A. J. (1996). Psycho-socionomics: Attractiveness research from a societal perspective. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 11(4), 683–694.

- Herbas Torrico, B., & Frank, B. (2019). Consumer desire for personalisation of products and services: Cultural antecedents and consequences for customer evaluations. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 30(3-4), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1304819

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Holmes, J. (2013). Women, men and politeness. Routledge.

- Homburg, C., Schwemmle, M., & Kuehnl, C. (2015). New product design: Concept, measurement, and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 79(3), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.14.0199

- Kahle, L. R., & Homer, P. M. (1985). Physical attractiveness of the celebrity endorser: A social adaptation perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(4), 954–961. https://doi.org/10.1086/209029

- Kamins, M. A. (1990). An investigation into the “match-up” hypothesis in celebrity advertising: When beauty may be only skin deep. Journal of Advertising, 19(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673175

- Kamolsook, A., Badir, Y. F., & Frank, B. (2019). Consumers’ switching to disruptive technology products: The roles of comparative economic value and technology type. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 140, 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.12.023

- Kenton, S. B. (1989). Speaker credibility in persuasive business communication: A model which explains gender differences. Journal of Business Communication, 26(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194368902600204

- Kim, Y.-J., & Na, J.-H. (2007). Effects of celebrity athlete endorsement on attitude towards the product: The role of credibility, attractiveness and the concept of congruence. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 8(4), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-08-04-2007-B004

- Knoll, J., & Matthes, J. (2017). The effectiveness of celebrity endorsements: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0503-8

- Kouzes, J. M., & Posner, B. Z. (1990). The credibility factor: What followers expect from their leaders. Management Review, 79(1), 29–33.

- Kreft, I., & de Leeuw, J. (1998). Introducing multilevel modeling. Sage.

- Leaper, C. (1995). The use of masculine and feminine to describe women’s and men’s behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 135(3), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1995.9713965

- Lee, Y., & Koo, J. (2015). Athlete endorsement, attitudes, and purchase intention: The interaction effect between athlete endorser-product congruence and endorser credibility. Journal of Sport Management, 29(5), 523–538. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0195

- Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.114

- Liu, M. T., & Brock, J. L. (2011). Selecting a female athlete endorser in China. European Journal of Marketing, 45(7/8), 1214–1235. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111137688

- Liu, M. T., Huang, Y. Y., & Minghua, J. (2007). Relations among attractiveness of endorsers, match-up, and purchase intention in sport marketing in China. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 24(6), 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760710822945

- Mason, C. H., & Perreault Jr, W. D. (1991). Collinearity, power, and interpretation of multiple regression analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379102800302

- McCracken, G. (1989). Who is the celebrity endorser? Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(3), 310–321. https://doi.org/10.1086/209217

- McGuire, W. J. (1985). Attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey, & E. Aronson (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 233–346). Random House.

- Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 852–863. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.852

- Ohanian, R. (1990). Construction and validation of a scale to measure celebrity endorsers’ perceived expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness. Journal of Advertising, 19(3), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1990.10673191

- Parker, H. M., & Fink, J. S. (2012). Arrest record or openly gay: The impact of athletes’ personal lives on endorser effectiveness. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21(2), 70–79.

- Peetz, T. B., Parks, J. B., & Spencer, N. E. (2004). Sport heroes as sport product endorsers: The role of gender in the transfer of meaning process for selected undergraduate students. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(3), 141–150.

- Rust, R. T., Lemon, K. N., & Zeithaml, V. A. (2004). Return on marketing: Using customer equity to focus marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.109.24030

- Su, Y., Baker, B., Doyle, J. P., & Kunkel, T. (2020). The rise of an athlete brand: Factors influencing the social media following of athletes. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.291.302020.03

- Till, B. D., & Busler, M. (2000). The match-up hypothesis: Physical attractiveness, expertise, and the role of fit on brand attitude, purchase intent and brand beliefs. Journal of Advertising, 29(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2000.10673613

- Vescio, J., Wilde, K., & Crosswhite, J. J. (2005). Profiling sport role models to enhance initiatives for adolescent girls in physical education and sport. European Physical Education Review, 11(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336X05052894

- Whittaker, J. O. (1965). Sex differences and susceptibility to interpersonal persuasion. The Journal of Social Psychology, 66(1), 91–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1965.9919624

- Wimalachandra, D. C., Frank, B., & Enkawa, T. (2014). Leveraging customer orientation to build customer value in industrial relationships. Journal of Japanese Operations Management and Strategy, 4(2), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.20586/joms.4.2_46

- Yoon, Y., Kim, J. W., Magnusen, M., & Sagas, M. (2018). Fine-tuning brand endorsements: Exploring race-sport fit with athlete endorsers. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 10(3), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.18666/JASM-2018-V10-I3-8964

- Zeithaml, V. A., Lemon, K. N., & Rust, R. T. (2001). Driving customer equity: How customer lifetime value is reshaping corporate strategy. Free Press.