ABSTRACT

This study investigates how the owner identity of media organisations affects their response to competing professional and market logics. To this end, a qualitative comparative multiple case study was conducted in the European news media sector. Our findings suggest that not only owner identity, but also the field position of the organisation is associated with particular market choices and the priority that is given to one market over another. This in turn has consequences for the degree of tension between coalitions with competing logics. Additionally, we find that the best owner-market fit for prioritising the democratic role of the press is a journalist employee cooperative that mainly serves a subscription market. Previous research on logics has addressed the role of ownership but did not include customer and employee cooperatives. Therefore, our findings provide important new insights.

Introduction

News media firms typically combine a for-profit mission with the societal mission of the press. Inside these organisations, this duality results in a daily struggle between editors and marketers that deeply affects the prospects for company survival (Achtenhagen & Raviola, Citation2009; Raviola, Citation2012; Raviola & Norbäck, Citation2013). On the one hand, the newsroom adheres to a professional (editorial) logic to serve the subscriber or paying audience market, while on the other hand, the advertising department adheres to a market logic. These institutional logics are “ways of ordering reality” (Friedland & Alford, Citation1991, p. 243) that may be at odds with one another. In response to this, a decoupling of institutional logics may occur inside media organisations. This happens when practices prescribed by one logic (e.g. the approval of journalistic codes of conduct) are only symbolically endorsed by the organisation, while practices prescribed by another logic (e.g. the publication of sponsored content to increase organisational profit) are actually implemented (Pache & Santos, Citation2013).

It has been found that ownership affects the organisation’s response to incompatible or competing logics (Greenwood et al., Citation2011). Yet, a systematic and controlled comparison of various forms of ownership in the media field is lacking (Achtenhagen et al., Citation2018; Picard & Van Weezel, Citation2008). To date, research has focused in large part on private and publicly owned corporations and non-profits, while ignoring alternative types of ownership, such as customer or employee cooperatives. Cooperative ownership has, however, been found to assuage the tensions that are present in media enterprises (Siapera & Papadopoulou, Citation2016). We address this lacuna in the literature by exploring a wide range of ownership types in the news media sector through the lens of institutional logics. To that end, this paper answers the following research question: how do media organizations with diverging owner identities respond to competing logics in their institutional field?

To answer this research question, we conducted a qualitative comparative multiple case study in 20 incumbent and entrant European news media organisations with employee and customer cooperative, non-profit, public and private investor owner identities. To analyse responses to conflicting professional and market logics, three elements of these logics were compared: 1) organisational goals; 2) corporate governance practices; and 3) markets served.

Our analysis reveals that diverging prescriptions coming from the advertising and subscription markets have different effects inside the media organisation depending on the (institutional) fit between owners and markets. We find that not only the owner identity, but also the field position of the organisation (either incumbent or entrant) is associated with particular market choices and the priority that is given to one market over the other. This has consequences for the degree of tension that arises among coalitions with competing market and professional logics, as is reflected in corporate governance practices inside the organisation.

We find that this degree of tension inside the organisation (institutional complexity) is highest in profit maximising (public) investor-owned incumbents that serve both subscribers and advertisers equally, which results in a decoupling response. A medium level of institutional complexity was found in non-profit and customer owned organisations where a third logic (state, community or religious) is selectively coupled. This third logic is less at odds with the professional (editorial) logic than it is with the market logic. Finally, the least institutional complexity is found in employee-owned cooperatives and entrants that predominantly serve a subscription market (i.e. little or no advertising revenues). Here, there are hardly any tensions between opposing coalitions, which makes a decoupling response unnecessary. This owner-market fit seems most conducive to prioritising the democratic function of the press.

Our findings contribute to the literature in three main ways. First, we contribute to the theory of the firm and the (media) management literature on ownership and logics (Achtenhagen et al., Citation2018; Benson et al., Citation2018; Pallas et al., Citation2016; Picard & Van Weezel, Citation2008). Based on their theoretical analysis, Picard and Van Weezel (Citation2008) conclude that there is no ideal form of ownership for newspapers. Our empirical study, however, indicates that some owners and markets have a better “fit” when it comes to emphasising the societal goal and democratic role of news media. We find that the assumptions of the theory of the firm are not applicable to all ownership types. Some owners may empower other (non-investor) stakeholders in the firm, such as employees or customers. We demonstrate that this has consequences in terms of which logic is dominant inside the organisation and the response to competing logics that results from this.

Second, this study explains how an organisation’s market choice (and the priority that is given to either the primary or secondary market) is linked to the identity, mission and logic of its owner and its field position (Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Hannan, Citation2010; Lounsbury, Citation2001). We shed new light on why the co-existence of multiple logics in a field (pluralism) does not have the same consequences in all organisations (Besharov & Smith, Citation2014; Greenwood et al., Citation2011).

Third, we provide a market-based explanation for why incumbent organisations are more exposed to tensions from multiple logics than entrants at the periphery (Ansari & Phillips, Citation2011; Hoffman, Citation1999; Leblebici et al., Citation1991; Phillips & Zuckerman, Citation2001; Zuckerman, Citation1999). We find that institutional complexity not only increases because incumbents become more “visible” at the centre of an institutional field, but that this also occurs because there is revenue dependence on a market that is part of a conflicting logic.

Theoretical background

Many studies of media ownership rely on the theory of the firm (Picard & Van Weezel, Citation2008). This theory argues that firms operate with perfect knowledge and seek to maximise profits (Cyert & March, Citation1963; Demsetz, Citation1997). It views the firm as a “black box” in which input is transformed into output as dictated by price mechanisms and technology in a situation of perfect competition. The theory of the firm has been criticised because it does not explain how this transformation comes about inside the organisation. In addition, this theory neglects agency problems that occur when the profit maximisation goal of owners (principals) is not aligned with the goals of management (agents) (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The separation of ownership and control may aggravate this agency problem (Berle & Means, Citation1932).

The basic assumptions of the theory of the firm seem applicable to only one type of ownership: that of investors. It ignores non-profit organisations and alternative forms of ownership. In response, Cyert and March (Citation1963) developed the “behavioral” theory of the firm in which the firm is viewed as a coalition of stakeholders that may have goals other than profit maximisation. Non-investor stakeholders in the firm, such as employees or customers, may be empowered via producer, customer, and non-profit owned enterprise (Hansmann, Citation1996). Determining which of these three types of ownership is most suitable can be done by weighing the (agency) costs of ownership and market contracting costs (Hansmann, Citation1996). The information asymmetries for customers and employees and the costs of monitoring managers, for instance, are relatively low in the context of customer and employee ownership, but relatively high in investor-owned firms (Hansmann, Citation1996). Picard and Van Weezel (Citation2008) apply a similar economic reasoning to private, public, non-profit and employee ownership of media firms and conclude that none of these are perfect. Their theoretical analysis, however, excludes customer and employee cooperatives and does not consider the effects of two-sided markets with competing logics.

Institutional theory differs from the theory of the firm in that it accounts for how pluralism in the field and conflicting prescriptions from logics play out inside the organisation. While the theory of the firm is based on the assumption of a situation with a single product and market (Cyert & March, Citation1963) institutional theory takes a wider view. It better accommodates the pluralism found in the media sector with its multiple markets and varied ownership. Institutional theory accounts for different types of owner identity, including family, cooperative, state, public equity and/or private investor ownership, that are each associated with distinct logics (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010; Chung & Luo, Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2011; Pache & Santos, Citation2013; Teixeira et al., Citation2017; Thornton, Citation2002; Thornton et al., Citation2012). In this paper, we respond to a call for an institutional approach in media management studies (Brès et al., Citation2018; Kosterich, Citation2020; Lischka, Citation2020) and use this institutional logics perspective to build on the theory of the (media) firm (Napoli, Citation1997; Tjernström, Citation2002).

Institutional pluralism and media markets

Institutional logics are “frames of reference that condition actors’ choices for sense making, the vocabulary used to motivate action, and their sense of self and identity” (Thornton et al., Citation2012, p. 2). Logics prescribe the goals and means that are appropriate for organisations and the kind of behaviour that is legitimate. Organisations comply with logics to gain legitimacy from other actors in the field in which they operate. Organisations that abide by the rules of one logic may break the rules of another logic, thereby losing legitimacy in the eyes of some constituents (Kraatz & Block, Citation2008; Purdy & Gray, Citation2009). Logics exist not only at the micro (individual) and meso (organisational) levels, but also at the macro (societal or field) level (Thornton et al., Citation2012). At the organisational level, logics manifest themselves in the organisational goal (Thornton, Citation2002), corporate governance, and managerial practices (Greenwood et al., Citation2009; Pache & Santos, Citation2013). A few studies also include the organisation’s target groups, like clients or markets (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010) as an element of logics at the organisational level.

At the field level, institutional “pluralism” exists when organisations operate in more than one institutional field (Kraatz & Block, Citation2008). As organisations have multiple resource dependencies, this pluralism is present in all institutional fields to a certain degree. Institutional “complexity” exists when an organisation experiences the incompatible or conflicting logics resulting from pluralism in a field. Complexity is thus latent, and does not always manifest itself in pluralistic fields (Ocasio & Radoynovska, Citation2016). At the field or societal level, multiple logics may prescribe competing or even incompatible goals and means in terms of legitimate organisational behaviour (Greenwood et al., Citation2011). At universities, and in law and accounting firms, for instance, the two logics of the profession and market may conflict (Lander et al., Citation2013, Citation2017). Similarly, a professional editorial and market logic co-exist in the field of publishing (Thornton, Citation2002, Citation2004; Thornton & Ocasio, Citation1999).

Media scholars have published on institutional logics in media fields (Benson et al., Citation2018; Bourdieu, Citation2005; Brants, Citation2015; Kosterich, Citation2020; Lischka, Citation2020; Van Dijck & Poell, Citation2013), but have dealt less explicitly with the way in which prescriptions stemming from two-sided markets play out inside the organisation. Most media scholars focus on the media logic defined as a set of principles that guides news journalism in promoting certain ways of “seeing and interpreting social affairs” (Altheide & Snow, Citation1979). The media logic endorses what the media will portray, who it will portray, how actors will be portrayed and how these components are put together (Pallas et al., Citation2016). Media scholars rarely include ownership, corporate governance practices and markets in their investigations of logics, as scholars of general (non-media) management and organisations do. Few logics studies account for the bottom-up processes of (market) audiences because most assume that the properties of audiences are more homogenous than they actually are (Durand & Thornton, Citation2018). The multiple markets that media organisations serve deserve more attention in the study of logics, as strategic change within organisations is strongly bounded by the interests of external entities, including customers (C. M. Christensen & Bower, Citation1996).

Responses to competing logics

In the general (non-media) management literature on logics, several responses to multiple logics in the field (pluralism) and institutional complexity are described. Three well-known responses of the organisation are decoupling, compromising and selective coupling of logics (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010; Pache & Santos, Citation2013). A decoupling of logics occurs when practices prescribed by one logic are only symbolically endorsed, while another logic – one that is more aligned with organisational goals – is actually implemented (Pache & Santos, Citation2013). A ceremonial conformity to institutional rules can, for instance, be “decoupled” from the organisation’s technical core, which may dictate efficiency (Greenwood et al., Citation2009). This type of “surface isomorphism” occurs when the prescriptions of the institutional context are contradictory (Zucker, Citation1987). A compromising of logics occurs when a new common organisational identity is created that strikes a balance between conflicting logics or expectations of external constituents (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010). For example, a new identity can be created through socialisation policies or by hiring new staff. This, however, does not work for fully competing goals or incompatible practices. The “selective” coupling of logics is not a compromise of logics resulting in a new identity, but rather a combination of activities drawn from each logic in an attempt to secure endorsement from a wide range of field-level actors (Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Pache & Santos, Citation2013). This strategy is often deployed by hybrid organisations or social enterprises that selectively couple intact elements from a certain logic. In contrast to decoupling, which is a ceremonial faking of compliance, selective decoupling entails the actual purposeful enactment of selected practices (Pache & Santos, Citation2013, p. 994).

Owner identity & logics

How organisations deal with conflicting logics and prescriptions from the markets they serve, is expected to diverge depending on the type of ownership a firm has (Greenwood et al., Citation2011). Previous research has shown that responses to institutional complexity and pluralism are aligned with the interests of third parties that fund those organisations (Lounsbury, Citation2001). Those with power, such as shareholders, will influence the appreciation and recognition of logics and the choice of which logic to prioritise; this in turn shapes the receptivity of organisations to multiple logics (Greenwood et al., Citation2011). The research on ownership and institutional logics has focused mainly on publicly traded corporations (Hillman & Dalziel, Citation2003), partnerships (Greenwood & Empson, Citation2003) and non-profits (Hwang & Powell, Citation2009; Malhotra & Morris, Citation2009). There is a lack of research on the effects of rare forms of ownership, such as customer and employee cooperatives. Generally, it is taken for granted that all enterprises are investor owned and most corporate governance research also only considers publicly listed firms (Van Oosterhout, Citation2008). However, non-investor ownership plays a prominent role in many important industries (Hansmann, Citation1996). Research on the general effects of ownership, has indicated that different owner identities are associated with different objectives, market contracting costs, profit destinations and governance practices (Hansmann, Citation1996; Thomsen & Pedersen, Citation2000). Owner “identities” (such as family, cooperative, state, public or private equity) determine the goals and capabilities of the owner. As such, they are a potential source of variance in corporate values and practices. The owner often selects members of the board of directors and stakeholder representatives to whom they delegate decision rights that relate to corporate values (Cannella et al., Citation2015; Greve & Zhang, Citation2017; Thomsen, Citation2004).

Financial investor ownership is, for example, associated with higher shareholder value and profitability, while other types of owners have other goals, like control (family owners) (Duran et al., Citation2016; Thomsen & Pedersen, Citation2000). It has been found that publicly traded firms find responding to institutional complexity more difficult than non-profits or private partnerships, which enjoy more inclusive decision-making processes (Greenwood et al., Citation2011). Family owned and managed firms are influenced by community norms and values and not simply market values alone (Chung & Luo, Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2011). In their review of the literature on ownership in the context of news media firms, Picard and Van Weezel (Citation2008) conclude that a more systematic and controlled comparison of the ownership types of media firms is needed. More recently, Achtenhagen et al. (Citation2018) signalled a lack of research on non-profit ownership of news media. There is an even greater lack of logic studies on customer and employee cooperatives in the media sector. This leads us to the following research question: how do media organizations with diverging owner identities respond to competing logics in their institutional field?

Method

To answer this research question, we conducted a comparative case study (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). Qualitative data enable explanations of complex social processes such as those studied here (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007, p. 26). Our contribution is to intermediate theory for which the comparative case study, based on the Eisenhardt-template, provides a good methodological fit (Edmondson & McManus, Citation2007). In the Eisenhardt-template, theoretically useful cases are selected through theoretical non-random sampling. These cases replicate or extend theory by filling conceptual categories. Some features of the comparative case study method (problem definition and construct validation) resemble hypothesis-testing research, while other features (within-case analysis and replication logic) are inductive (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). We study variance between cases that represent theoretical constructs (ownership identity and organisational age). Our study yields tentative findings of which more quantitative testing is warranted, as qualitative research is always limited in its transferability and generalisability (Guest et al., Citation2014; Tracy, Citation2010).

Case selection

Non-probability or non-random sampling with a “most- different-systems” sampling design was chosen to maximise the variation of theoretically relevant attributes (Przeworski & Teune, Citation1970). The cases in this study were selected because they provide unusually extreme or revelatory examples (Yin, Citation1994). They represent the organisational age (field position) and owner identities that allowed us to approach the data from different dimensions (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). Cases were added and removed to probe new themes that came up during the data collection and analysis process. This “controlled” opportunistic data collection method is a key feature of the multiple case study method (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). Out of a population of hundreds of European media organisations, the cases with the purest form of five owner identities, based on the categorisation by Hansmann (Citation1996), were selected. These categories are: 1) employee owners; 2) customer owners; 3) non-profit owners; 4) private equity investor owners; and 5) public equity investor owners. Some of these cases have a central field position (incumbents), while others have a periphery field position (entrants). The field position of the cases was defined according to the age, size and activities of the organisation. All news media organisations founded before 1999 were categorised as “incumbents”, as they all offer both paper and digital publications. The pure players, ones that largely offer digital-only publications and were founded after 1999, were categorised as “entrants”. All twenty cases included in this study are European enterprises of different sizes, ranging from less than ten to thousands of employees. Only the investor-owned incumbents and the public investor-owned entrants have more than one hundred employees. What all cases share is that they all have an editorial team of professional journalists that produce unique content.

Data sources

For all 20 cases, data was collected to map three elements of logics: 1) organisational goal(s); 2) corporate governance practices; and 3) markets served. We did not seek to take a temporal snapshot but intended to spread our research out over a longer period of time to allow for iterative cycles in the analysis. We chose to study the period between 2012–2016, at which point the crisis among legacy news publishers reached a peak due to declining revenues from advertising. This was partly the result of the financial crisis in 2008 and partly the result of the growth of platforms like Facebook and Google that became serious competitors due to the rise of the mobile phone and the widespread use of social media. In the period between 2012 and 2016, newsrooms were not yet as much exposed to (or forced to) adopt the emerging technology logic as they are now. Most of the cases we studied still received most of their revenues from non-digital products, making the effect of technology less influential inside these organisations. At the time of our data collection technological innovation was actively ignored and resisted by editorial staff (Lischka, Citation2020; Tameling, Citation2015).

In the period between 2012 and 2016, many new European start-ups emerged that had a focus on “advertising-free” business models. Some of these start-ups were founded by former newspaper editors in reaction to the increasing pressure on editorial autonomy they experienced. These start-ups also consciously adopted alternative forms of ownership (cooperatives, partnerships, non-profits) that are still an important part of their value proposition today (Sanders, Citation2018). Between 2012 and 2016, there was a remarkable wave of innovation in European journalism with start-ups with membership models (Membership Puzzle Project, Citation2017) that created new brands that are still relevant market leaders in their own small, advertising-free segment today.

At the 20 case organisations, a total of 28 semi-structured interviews of 60 to 90 minutes were conducted (see Appendix A). This resulted in a total of 2,146 minutes of recording and 896 pages of transcript. For each case, we also collected secondary data: approximately 13 editorial statute documents, 51 financial annual reports and newspaper articles from LexisNexis, as well as the organisations’ websites (see Appendix A). The editors-in-chief, publishers or owners at these organisations were interviewed using two basic interview protocols (or topic list) for each round (see Appendix B). We interviewed shareholders and media tycoons that rarely give interviews on this topic. The exact order and number of questions used varied, as these were semi-structured interviews.

The annual financial reports and editorial statutes were gathered in two subsequent rounds of data analysis before the interviews. In the first round, we used the annual financial reports of 2012 for most cases. If that report was not available, we used the 2011 version. For the cases in the second round, we used the 2015 financial report. As not all cases had publicly available statutes and financial reports, we relied on the interviews and other sources to fill in any missing gaps in the secondary data.

Editorial codes of conduct, statutes and councils are the products of governance practices that are typical in the news media field. These are manifestations and indicators of responses to conflicting logics and incompatible prescriptions that these firms experience. The statute and council are traditional governance practices that protect the newsroom from commercial pressures exerted by advertisers and the sales departments of the same news media firms. Statutes describe the mission and identity of a publication and stipulate how the editorial council and the editor-in-chief should be appointed or sometimes even democratically elected by the newsroom. Many of the editorial statutes we studied are not publicly available and, as far as we know, have remained largely unchanged over the past several decades. Most of the organisations we studied as cases still exist today.

Data analysis

In this comparative case-study, we first investigated unique patterns observed within each case on its own; then, in a second step, patterns across cases were explored (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). To this end, summary “construct” tables were used that are closely tied to the data (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). These tables allowed for comparison between cases, drawing of inferences from the data, finding relationships and recognising patterns of relationships among constructs within and across cases. The data were collected and analysed in two consecutive rounds: the first between 2012 and 2014 and the second between 2015 and 2016. This allowed for deeper understanding and insights because it permitted several iterative cycles in which we moved from the data back to the literature and from the literature back to the data. We analysed all datasets using the same method, transcribing and coding them using NVivo software.

Round one

During the first analysis round, we conducted 23 interviews that were then transcribed and coded. As a next step, the secondary data from the editorial statutes and financial annual reports were placed in comparative tables (See ) in which the governance practices (ombudsman, advisory council, editorial statute, editorial council, appointment procedure of editor-in-chief) were listed for each case. The financial details from the annual reports were also compared for each case. We studied the percentages of revenues coming from advertising and subscriptions, numbers of newsrooms and titles; numbers of full-time employees (fte) newsroom staff and total staff; revenues per fte newsroom and total staff; solvability; liquidity, net results and dividends paid. In this first round of analysis, we discovered that a relatively high dependence on revenues from the reader market strengthened the position of the editor-in-chief and publisher of titles in portfolios. A relatively high dependence on revenues from advertising, in contrast, had the opposite effect and was indicative of pressure on editorial autonomy that required specific contracts and governance practices to safeguard editorial autonomy. We found that some owners preferred to prioritise one market over the other.

Round two

During the second round of data collection and analysis, five new cases with purer owner identities (majority shares) were added. As many of the cases in the first round were incumbents with mixed owner identities (mainly a mix of non-profit and investor ownership), we felt that a new sampling round was needed. As in the first round, interviews held at these organisations were also transcribed, coded and triangulated with secondary data from LexisNexis articles, information from the case organisations’ websites, financial reports and editorial statutes or codes, where available.

The interview data was used again to check if the support of owners for editorial governance practices (e.g. editorial codes, statutes, and boards) varied with different owner identities and market dependencies. In the second analysis round, new comparative tables with interview and secondary data were created that included all 20 cases (See and in findings section). Two cases were selected and compared for each of the five categories of owner identity: 1) employee cooperatives; 2) customer cooperatives; 3) non-profit owners; 4) private equity investor owners; and 5) public equity investor owners. We assigned letters to the cases to avoid the identification of respondents who were guaranteed anonymity.

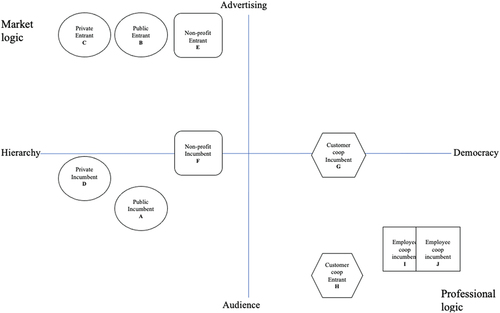

Based on the percentages of revenues coming from either the subscribers (or members) and advertisers, we mapped the ten purest owner identity cases in a scatterplot along the vertical Y-axis (see ). If 100% of an organisation’s revenues came from subscriptions, it was plotted at the bottom end of the vertical axis. If 100% of revenues came from advertising, we plotted the case at the top end of the vertical axis. If there was a near 50–50 split of revenues the case was plotted near the X-axis. The shapes of the cases (circle, oval, square and hexagon) represent the four different types of owner identity: employee, customer, non-profit and investor (private and public).

Based on the primary and secondary data on governance practices (also see Comparative ), we determined if decision making was either “democratic”, “semi-democratic” or “top-down” for each case. Democratic decision-making would fit the professional logic of the press as the fourth estate, public debate, and representation of all voices, while top-down decision-making with the aim of an increase in efficiency and profit would fit better with the market logic. On the horizontal axis, the cases are plotted according to the extent to which decision making is democratic or hierarchical (top-down). The position for each case on this dimension was determined by analysing three variables: 1) presence of democratic or hierarchical decision-making practices; 2) (editorial or financial) board composition; and 3) presence of editorial statutes and codes.

A case was plotted at the extreme lefthand side of the X-axis (100% hierarchy) if it had no editorial councils, no codes, no statutes, no elections to appoint editors-in chief (or other democratic forms of decision making), no editors in the top management team (board of directors). If the complete opposite was true, the case was plotted at the extreme righthand side of the X-axis (100% democracy). Cases with mixed results on the three variables were plotted towards the middle (vertical axis).

Findings

We find that the five owner identities of the cases studied here have different missions and logics that fit better with either the advertising or subscription market. This has consequences for the degree of institutional complexity that is experienced inside these organisations (see below) and the response to this. As we shall now explain, the different prescriptions that stem from distinct markets have different effects inside the organisation depending on the owner identity and on how dependent the organisation is on each market for its revenues. We find that institutional complexity is greater (and a decoupling response more likely) when there is about an even split between revenues coming from subscribers and advertisers. A decoupling response was found in investor-owned cases, a selective decoupling response in the customer and non-profit owned cases, and no decoupling response in the employee-owned cases.

Table 1. Summary of Results.

Our data confirm that the prescriptions that emerge from the two markets that news media organisations serve (subscribers and advertisers) are often incompatible. On the one hand, the advertiser typically pays a news media organisation to reach an audience with the aim to increase sales of the advertiser’s product or service, and this may be done via banners or other types of advertising. On the other hand, subscribers pay for content produced by autonomous professional journalists who fact check, separate fact from opinion and abide to the “audi alteram partem” principle. These subscribers may be annoyed by advertising in disguise or lose trust when content appears to be sponsored (particularly when this is not clearly stated). It is the audience of subscribers that is the primary market that attracts the secondary market of advertisers, not vice versa. As the following quote illustrates:

You can only sell ads when you have the reach [of an audience] that you can market. The basis is always content, the basis is always circulation. After that comes sales because that is selling the reach. Another order is impossible. (Case D)

Some news consumers want to be informed about socially relevant topics that advertisers do not want to be associated with:

Well, no one will ever admit it entirely, but of course an advertiser wants an environment that is nice or positive for its advertisement … . If you – let’s say – sell trips to an exotic destination, then you do not want your ad to be next to horrible articles about torture in the countries that are the destinations of those tips you sell. (Case H)

In addition, the prescriptions that emerge from the advertising market can also collide with the professional editorial logic of the newsroom, as is described in the following quotes from Case B:

We have what we call “rich media statements”, which are large homepage takeover, big things … There we test the boundaries, because that’s where lots of money can be made … . There is a tension; if you advertise more, you earn more, but you might irritate [website] visitors …

Reaching an audience occupies us, but it is not the only thing we steer on, because I feel that a journalistic organization has the duty to inform people about what happens in the world; Syria for example. We see very clearly that no one clicks on that news, nobody is really interested.

Moreover, we find that not only the owner identity of the organisation is associated with the reliance on one market, but the field position (age of firm) also. On the one extreme end (lower right quadrant) of are the reader cooperative (an entrant) and employee-owned cooperative owned cases (both incumbents). These have the highest dependence on revenues coming from the market of paying audiences (subscribers, members, etc.); the professional editorial logic is dominant here and governance practices are highly democratic (also see quotes on decision-making in ). On the other extreme end (upper left quadrant) of are the entrant investor-owned cases, that enjoy no revenues from subscribers and focus entirely on online advertisers or sponsors. Here the market logic is dominant and governance practices are less democratic.

Most incumbent cases, regardless of their owner identity, serve both the market of a paying audience and advertisers of both paper and digital publications. As can be seen in , most of these incumbents – except for employee cooperatives – are near the line of a 50–50 revenue mix. Unlike the incumbents, entrants focus predominantly on one type of market: either the online advertiser or the online paying audience. Whether or not both markets are served simultaneously seems to be correlated with the field position of the organisation. We shall now discuss the variance in the degree of complexity and responses to it in more detail for each owner identity.

Investor owner: decoupling response

Institutional pluralism was experienced as most complex inside the investor-owned cases. Here, the conflict between two opposing coalitions with a market and professional logic, respectively, was found to be strongest. The governance practices and symbolic support for these practices by the owner indicate a decoupling response. All cases with public and private investor owners have a for-profit mission that varies in its degree. As can be deduced from , the “profit extraction” or percentage of residual earnings that is paid to shareholders is highest in the publicly listed cases. The for-profit mission of investor owners often results in cost cuts, which reduce the quality of contentFootnote1 that is sold to subscribers.

Table 2. Comparative table data cases.

For example, the search for synergy effects may result in the creation of portfolios of titles that all share one central newsroom (instead of each title having its own newsroom), which in turn leads to the firing of newsroom staff. This not only reduces the quality of the content produced, but the threat of losing jobs may also put the autonomy of the newsroom under pressure. The following quotes illustrate how profit-maximising investor owners are perceived very negatively by professionals in the newsroom:

We achieved profit margins of 10 percent and were perfectly happy with that, but it was not enough, so we had to economize … then we heard on the news that our CEO and his small team of managers had received XXX million euros as their yearly bonuses … . I know several people then decided to quit their job due to idealistic motives. They no longer wanted to work there. (Case A)

Newspaper publishers owned by public investors demand 20 percent ROI per year. And if that doesn’t happen, another 300 employees will be fired. Well, that is the scenario of demolition. (Case F)

The public investor owners are more distant, single-minded and have a more financial and short-term focus than the private equity investors as described below.

The valuation of the firm is harsh because it is made public via the listing on the stock exchange … repeatedly the shareholder is reminded; dammit, my shares are not worth a dime, I need to take action towards the guys on the supervisory board. It is very short term, not quarterly, but a few years maximum. (Case A)

Well, in our case the owner is pretty much an abstract concept. I would not really know who the owner is, to be honest. (Case B)

Just to summarize it briefly: all private equity owners are the same … When they come in they make agreements about their exit. So, you know that if you have this owner for maximum 5 years, there’s no real commitment. (Case D)

The private investor owners of the entrant Case C have a more strategic mission and no profit is extracted because losses are incurred, as is reflected in the following quote:

So, their strategic interest might be more towards gaining know-how in that and gaining access to technology. Things like that to help them evolve as a regional product. (Case C)

Table 3. Examplary quotes from interviews.

There is no ideological or social mission in any of the investor-owned cases, which distinguishes them from the other cases. This difference is well described in the following quote:

One part of journalism started as truth-finding within a particular socio-political group and they were very rigid. Other orientations picked up the challenging task of filling the back of pages with advertising. That is something completely different and you still notice the difference a lot. In the governance, but also in the whole culture there is an enormous difference between those backgrounds. So, that’s why “dual” comes in different gradations. For [Case D] the commercial goal is very clear. (Case D)

As a result of their for-profit mission, the investor-owned cases tend to prefer serving markets with high profit margins. In publishing, the highest profits can be made with ads in print publications. The profit margins for online advertising are much lower. Out of every 10 euro that is lost from advertising revenue in print, only 1 euro maximum is regained in the digital domain at Case D, for instance. To make up for this loss in advertising revenue, investor-owned firms have started to offer branded or sponsored content. This new type of advertising, where ads are disguised as journalistic content, is very lucrative. If approximately 1% of all content is branded, this generates a third of the total revenue of Case C, for instance.

In terms of maximising profits, branded content is very effective. However, it negatively affects editorial autonomy, the quality of the content and trustworthiness as seen by subscribers who pay for objective reporting. The market logic here strongly conflicts with the professional editorial logic and interests of the paying audience. Publishing sponsored and branded content could be considered a decoupling response, as this practice only symbolically embraces the editorial logic in an effort to realise a profit goal. One respondent indicates that this type of sponsored content leads to very different interactions and checks-and-balances in the realm of governance as well. It is much more complex than traditional advertising.

When investor owners give priority to the advertising market over the other market side, this also has consequences for editorial autonomy in a different way. The editor-in-chief has a much weaker bargaining position when it comes to protecting the newsroom from commercial pressures when most revenues come from advertising.

I remember that I felt it was more relaxed when the readers’ market gave us more revenue than the advertising market – while I of course thought, well… in that situation you are more in control…. When commercial success is the course that is sailed, this is not necessarily what is best for journalism. (Case B)

The boards of the investor-owned cases have no or very few journalists on them as compared to the cases with other owner identities whose boards have a much less commercial identity. As a result, the editors-in-chief feel torn between two opposing coalitions: the newsroom and management:

In our statutory board of directors there is no journalistic blood and that’s difficult… It is very nice to be part of a board of directors that understands what excites the newsroom or what upsets it… One cannot do without an editor-in-chief who unites both the commercial and ideological function – in one type of medium more so than in another. It has been a hybrid position for centuries. And this changes; in some periods the commercial pressure may be higher, but its essence doesn’t change. (Case D)

In the investor-owned cases, the governance practices that should protect the interests of the paying audience and journalistic professionals are only symbolically endorsed. Respondents indicate that the investor owners are not wholly in support of editorial statutes. These statutes often date from a pre-internet era with non-profit owners and are unpopular with managers of investor-owned organisations, who prefer hierarchical decision making, as is reflected in the following quote:

The statute can lead to an access of democratization slowing things down … The reality is, however, that employees - and editors are also employees – never are able to block the strategic goals of the owners nor the boards of directors. Editorial statutes, but also the employees or other participatory councils, can eventually never block the strategic policy and goal of the board. If they think that they can, it is an illusion. (Case A)

In the publicly listed investor-owned entrant (Case B), the newsroom very much wants an editorial statute, but the publisher simply does not implement it, as the following quote illustrates:

I must say that it [statute] is something that I am very enthusiastic about, but not my superiors. We did make a compromise, but somehow every time something comes up which delays it. I am not sure if this is on purpose or that … Well, to me this statute is something to guarantee we have this agreement, and for now this is fine, but as soon as we get a new publisher, it is not certain if our agreement will still hold. (Case B)

One editor-in-chief at a publicly listed investor-owned incumbent Case A describes what would happen if the editorial statute were to disappear: “I would not be in favour of that because the societal role will immediately be endangered. Many directors and power managers push for it and say it’s time to abandon this practice”.

In sum, investor-owned incumbent organisations that serve multiple markets operate in conditions of high institutional complexity. This leads to a response in which the editorial and market logic are decoupled. In other words, a symbolic conformity to the institutional prescriptions of the field to protect editorial autonomy is “decoupled” from the organisation’s technical core, which is geared towards the for-profit mission.

This decoupling response is, however, less visible in the investor-owned entrants (in the upper-left quadrant ) where advertisers or sponsors are the only market served. Traditional governance practices, like the establishment of statutes or voting to elect the editor-in-chief, are lacking here. The full dominance of the market logic in the entrants is well illustrated in the following quote from an editor-in-chief at the private investor owned entrant case:

And that is something we are trying to do […] when a client has a content marketing need, we don’t want the client to go to say an ad or branding agency and then to a creative agency and then to a whatever agency and then to us. We want to do the whole process with the client directly. (Case C)

Non-profit & customer owners: selective decoupling

A medium level of institutional complexity is experienced in the non-profit and customer owned cases in which the owner and customer share a similar third logic. Here community, religion, state, and academic professional logics are coupled selectively with the editorial logic. This third logic, however, is not as much at odds with the editorial logic as the market logic in the investor-owned cases is. As the market logic is not prominent in both the non-profit and customer-owned cases, there is no profit maximisation mission that may put the newsroom under pressure. Profits are not paid out as dividends but are rather reinvested in the organisation (see ). Some respondents even describe the owner identity of their organisation as being protective against the influence of investor owners:

It’s very important to keep the actual organization and publication safe from outside interest as well, so if you are worried about outside interests coming inside your media organization then I certainly recommend looking at the cooperative business model. (Case G)

The two customer cooperative cases (G & H) each have a different mission that is strongly linked to the particular market they serve. The mission of the customer-owned cooperative entrant (Case H) is “to provide quality journalism and to create an environment and publication in which journalism can flourish.” The majority owners of this cooperative are individual subscribers who represent the paying audience market.

I think that the cooperative is an interesting [ownership] form, precisely because it is not geared towards profit maximization, but nevertheless it is indeed an enterprise model. That is also what we aim for: we do not want to make a profit, that is not our intention. We want to grow into a cost-effective enterprise that eventually makes a profit and reinvests that. (Case H)

Case H’s revenue comes mainly from paid online subscriptions and some subsidies. It is a conscious choice not to serve any advertisers at all.

The incumbent customer cooperative (Case G) is not owned by individuals, but by other cooperatives, political parties and labour unions. These shareholding organisations are also its customers in both markets for print and online advertising and subscriptions. The mission of this very old cooperative is to be “the glue” that binds the cooperative movement; there are no dividend payments, as the owners are more interested in ensuring the sustainable survival of this social enterprise.

The non-profit cases’ mission is also strongly linked to the identity of their customers. Two incumbent cases (F & Q) are owned by foundations with a religious mission and serve subscribers and advertisers that are part of the religious community:

Well, the objective of the foundation, its vision and mission states very clearly that we are on earth to bring Christian journalism to the people in an appropriate style. We have no return-on-investment demands. (Case F)

Another non-profit incumbent is state-owned (Case P) and its state logic dictates that it serves an audience that includes all Dutch citizens. The owner of the non-profit entrant Case E is a trust that “seeks to further the dissemination of academic knowledge to the general public” and it does not want “to make money.” It has a new type of customer: universities that sponsor content about academic research indirectly via membership fees. No paid subscriptions are offered at Case E, so most content is, in effect, subsidised by universities plus some initial government subsidies in the start-up phase.

Governance practices in all customer and non-profit cases are semi-democratic, as there are no elections for the editor-in-chief (see ). A respondent at Case F describes it as follows: “I think that [the election of editor-in-chief and council] is more a remnant of the period of employee self-governance… the seventies, yes… not our thing… let me just be clear about that.” At the non-profits, special advisory boards give advice on editorial matters, which somewhat conflicts with the professional logic of editors who do not want any outside interference in editorial decision-making in the newsroom. These extra boards must ensure that the mission of the non-profit owner is lived up to by the newsroom and because this detracts from editorial autonomy, it is considered a semi-hierarchical decision-making practice.

That board much guarantees or seeks to guarantee the academic rigor aspect of that. We can talk about the journalistic flair as well, but the academic rigor – you know- they know what that is – these are senior academics … (Case E)

The supervisory board oversees the business side … and we have an advisory council that more so spars with the editors-in-chief about the content of the newspaper. (Case F)

Like the investor-owned cases, many of the customer and non-profit incumbent cases (O, F, Q and G) also have a near 50–50 advertising and audience revenue split. The community, religious or academic professional mission of the owner ensures that the market logic of advertiser market does not take precedence over the logic of the subscriber market. At times, for instance, particular ads are banned because they are not in line with the norms and values of the reader community. In some of the customer and non-profit owned cases, sponsored or branded content is offered, but the owner’s mission ensures that only sponsors or advertisers that match the identity of the audience are served. The following quote illustrates how selective decoupling of the religious logic occurs because advertisers are excluded from business because they do not have a matching mission:

Out of responsibility for the look and feel of our product, the advertising department said – also to the advertiser – “I think it is better that you do not advertise with us, because no one is to gain because our readers will not be fooled”. (Case F)

Employee cooperatives: no decoupling

Institutional pluralism was experienced as least complex in the employee cooperative cases and entrants. The professional editorial logic was found to be most dominant in the employee-owned cases. The cases that have the purest form of employee ownership are T, I and J, with the ideological mission of their journalist owners. Their primary aim is to improve society or help citizens improve their lives and to create editorial jobs with a high degree of professional autonomy. As a result of these missions, all residual earnings are reinvested in the organisation, no or little dividend is paid to the journalist owners (see ). This low “profit extraction” makes the employee cooperatives less dependent on revenues from the advertising market, thus reducing complexity.

Cases T, I and J get most of their revenue from the paying audience market and they explicitly do not offer branded nor sponsored content, as this would conflict with the editorial logic. For professional reasons, employee cooperatives will never serve advertisers at the expense of the reader or subscriber communities. On the contrary: opportunities to sell ads are even lost because of the editorial mission of the organisation:

We lost advertising because of our articles. So we lose advertising, because of our identity and work – and our mission. Not we are … it’s contrary to that we are influenced … So we influence them [the advertisers] to cut. (Case J)

The employee-owned cases draw on their very low dependency on advertising revenues to increase their perceived legitimacy in the field. This is also essential to ensuring that the organisation receives support in the form of donations or (equity) crowdfunding and subsidies, as this respondent describes:

There is no advertising on the website. The important part is that we just fund it with subscriptions. That’s why when we crowdfund something, usually we get good results because we are transparent about our objectives…. We used to say that [Case J] is made for readers because without them we are nothing… We don’t have any political party or economic entity behind us. Just these fifty or so workers making a newspaper. (Case J)

In the employee-owned cases, a relatively high number of board members has a background in journalism. Although this may seem counterintuitive, a lack of editorial codes or statutes indicates that a conflict between the market and professional editorial logic is hardly present. The owner identity itself constitutes the governance practice that protects editorial autonomy and democracy, as the following quote illustrates:

We decide together almost everything – even to buy the computers. If you have to do a newspaper in black-white or in colour. If you have to launch a different supplement, there is always an assembly going on. If we decide to vote in majority. On the people, we always vote with secret ballot – so it’s a true vote…it’s better to work here, because here you can work on what you like, on what you think and what you know – what you want other people to know. It’s not so in every other newspaper, where you have to convince, to persuade the editor or the publisher that your story is well-grounded. You are free here. (Case I)

The respondents at the employee-owned organisations indicate that this owner identity guarantees editorial autonomy, making editorial statutes unnecessary: “no, we don’t have that [editorial statutes] because I don’t think we need that; there is nobody who would say, now you now have to work together with commercial [departments].” (Case I). The protection of editorial autonomy, guaranteed by the owners’ mission, is much more than a symbolic ritual, so there is no decoupling response. The employee cooperatives enjoy highly democratic governance practices, such as majority voting by all staff for the election of the editor-in-chief and voting on many other decisions. Wages are egalitarian and in one of the employee cooperatives there is not even a leader, director or CEO;

It [voting] is for the … no, it’s for the real important things – if we choose to make a new layout for example or how high our salaries are. That’s something that everybody together we vote about it…We have … our wages are not so high as in other newspapers, but we are quite attractive because we have … we can offer a lot of freedom – that’s because of how we are organized, our ownership … the newspaper … (Case J)

In sum, institutional complexity is lowest in the employee cooperatives because these organisations predominantly serve a market that is compatible with the professional editorial logic of the owners. The primary customers of these organisations are readers who want to pay for content that is produced by autonomous professional editors. The market logic of the advertisers can be ignored by the newsroom.

Discussion

In this study, we explored how media organisations with diverging owners respond to competing logics in their institutional field. Although previous research on logics has addressed the role of ownership, it has not systematically nor empirically compared the effects of a wide range of owner identities in the media context (Achtenhagen et al., Citation2018; Benson et al., Citation2018; Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Picard & Van Weezel, Citation2008). Most studies of logics and (media) ownership usually exclude customer and employee cooperatives, two forms of ownership that provide new insights in this study.

The key finding of this study is that different prescriptions emerging from distinct markets have different effects inside the organisation, depending on the (institutional) fit between owners and markets. We find that not only the owner identity, but also the field position of the organisation is associated with certain market choices and with the priority that is given to one market over the other. This, in turn, has consequences in terms of the degree of tension between coalitions with competing logics (institutional complexity), as reflected by corporate governance practices inside the organisation.

We find that institutional complexity is greatest in profit maximising (public) investor-owned incumbents that serve both paying audiences and advertisers equally, resulting in a decoupling response. A lower complexity is found at the pure playing entrants in the advertising market, that have no subscription revenues nor any governance practices to safeguard editorial autonomy. These entrants are, however, still subject to the conflict of market and professional logics. A medium level of institutional complexity was found in non-profit and customer owned organisations where a third logic (state, academic, community or religious) is selectively coupled. This third logic which is the same as the logic of the editors and their audience, seems less at odds with the professional (editorial) logic than the market logic. Finally, the least institutional complexity is found in employee-owned cooperatives and entrants that predominantly serve a paying audience market (i.e. little or no advertising revenues). As there are hardly any tensions between opposing coalitions here, a decoupling response is not necessary. This owner-market fit seems to be best suited to prioritising the societal role of the press in a democracy.

In media firms, a decoupling response manifests itself in commercial pressure on editorial autonomy, reflected in the offer of branded content and the presence of certain governance practices, such as the establishment of editorial statutes and councils. Some owners (investors) only support these practices symbolically (as the branded content proves), while others (employee cooperatives) make them unnecessary. We also find that the audience for news content is the primary market that attracts a secondary market of advertisers. Serving this primary market, however, is not the main priority of owners with the goal of profit maximisation (investor owners) that favour the more profitable advertising market. The editor-in-chief has a much weaker bargaining position when it comes to protecting the newsroom from commercial pressures when most revenues come from advertising.

We make three main contributions. First, with our findings, we contribute to the theory of the firm and the (media) management literature on ownership and logics (Achtenhagen et al., Citation2018; Benson et al., Citation2018; Pallas et al., Citation2016; Picard & Van Weezel, Citation2008). Based on their theoretical analysis, Picard and Van Weezel (Citation2008) conclude that there is no ideal form of ownership for newspapers. Our empirical study, however, does indicate that some owners and markets have a better “fit” in terms of the societal goal and democratic role of the news media than others. We find that the assumptions of the theory of the firm are not applicable to all ownership types. Some owners may empower other (non-investor) stakeholders in the firm, such as employees or customers. We demonstrate that this has consequences in terms of which logic is dominant inside the organisation and in terms of the response to competing logics that results from this.

Second, we explain how an organisation’s market choice (and the priority that is given to either the primary or secondary market) is linked to the identity, mission and logic of its owner and its field position (Greenwood et al., Citation2011; Hannan, Citation2010; Lounsbury, Citation2001). The degree of complexity experienced in organisations with public versus private investors was found to differ less in our study than in other previous studies (Greenwood et al., Citation2011), especially when compared to owner identities with non-market logics. However, we do find that less inclusive decision-making processes (Chung & Luo, Citation2008; Miller et al., Citation2011) are not the only reason why (both public and private) investor owners have more trouble responding to competing logics. Our findings indicate that this also becomes more difficult when the primary market that the organisation serves does not share the same logic as the majority owner. For instance, full dependence on revenue from the paying audience market becomes more troublesome when there is a private equity fund owner with market logics. This situation is more likely to result in internal conflicts that may negatively affect the organisational performance.

Third, we shed new light on why the co-existence of multiple logics in a field (pluralism) does not have the same consequences in all organisations (Besharov & Smith, Citation2014; Greenwood et al., Citation2011). We provide a market-based explanation for why incumbent organisations are exposed more to tensions from multiple logics than entrants at the periphery (Ansari & Phillips, Citation2011; Hoffman, Citation1999; Leblebici et al., Citation1991; Phillips & Zuckerman, Citation2001; Zuckerman, Citation1999). We find that institutional complexity not only increases as incumbents become more “visible” at the centre of an institutional field, but that this also occurs because there is revenue dependence on a market that is part of a conflicting logic.

Our findings also have practical implications. For example, the dependence on high profit margins of old technology markets is an important explanation of why incumbents fail in new markets (C. Christensen, Citation1997; C. M. Christensen et al., Citation2018, p. 1048). This paper provides an explanation for why entrants may be more successful at serving new technology markets (C. M. Christensen & Bower, Citation1996; C. M. Christensen et al., Citation2018). We find that entrants operate in lower complexity because they can focus on a single market instead of several. However, we find this may also apply to incumbents with non-investor owner identities that have more organisational room to focus on low profit margin market categories, thereby enhancing their innovative capacity.

In addition, a decoupling response signals a conflict between editorial and commercial goals that may affect content production or alienate subscribers, causing paralysis or lowering organisational performance. The ownership of the organisation and its dependence on advertising are known to influence content production (Baker, Citation2007; Mosco, Citation2009; Shoemaker & Reese, Citation2014; Winseck & Jin, Citation2011). This also applies to new players in the advertising market that struggle with issues pertaining to the dispersal of fake news, conspiracy theories and other harmful content (Rathenau Instituut et al., Citation2022). Revelations by Facebook’s whistle-blower Frances Haugen (Wall Street Journal, Citation2022), for instance, seem to indicate that social media platforms struggle with a similar type of internal tension caused by conflicting goals and logics. Our study shows that choices with regard to a particular market, governance practices and ownership may offer solutions here.

As with any study, ours is not without limitations, which in turn opens up avenues for future research. In the entrant cases, for instance, it could further be explored how a new technology logic affects responses to institutional complexity. Lischka (Citation2020) mentions compartmentalisation, deletion, fusion and aggregation of additional logics such as the managerial and technology logic by journalists in media organisations. For instance, following the tech logic (Coates Nee, Citation2014; Kosterich, Citation2020) newsroom technologists try to achieve the fourth-estate mission via fusion of professional and tech solutionism. Belair-Gagnon et al. (Citation2020)also analyse how intrapreneurs (who develop chatbots in the newsroom) adopt logics of experimentation, audience orientation, and efficiency-seeking that may conflict with the professional journalistic logic. Future research could further explore these types of logics and content related to it (Sanders, Citation2021; Sanders & van de Vrande, Citation2024).

Another limitation of our study is that our European cases are positioned in several national fields. By studying organisations in just one country, we could have controlled for any effects of national differences, such as those that have been found among liberal market economies and coordinated market economies (Sauerwald et al., Citation2016). Future research could also include cases that we could not find in the European news media sector: entrant employee cooperatives and fully independent investor-owned entrants that are not owned by incumbent media organisations.

Finally, our study yields tentative findings for which more quantitative testing is warranted. Future research therefore could study a sample that is more representative of the whole field and all owner identities in it. Cases with highly democratic governance practices and full dependence on advertising revenues were not found in the population that was used for this study. It is expected that these cases are very rare. As such, exploring why complete dependence on revenues from advertising is rarely associated with highly democratic governance practices could be an interesting direction for future research. Furthermore, this study now only maps two types of markets (paying audiences and advertising), but it does not subdivide these into online and print markets. A next step could be to map the prescriptions that stem from these four distinct markets in more detail. To this aim, a content analysis of the content offered by pure players and hybrid players in the analogue and digital advertising and audience markets (also see: Sanders & van de Vrande, Citation2024) could be considered. It could also be interesting to compare non-subscription content funded by members, (institutional) donors or governments and public organisations (licence fee, general taxes, or subsidies).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Mathilde Sanders

Mathilde Sanders holds a PhD in Strategic Management and Entrepreneurship (Erasmus University Rotterdam) and a Master in Political Science (University of Amsterdam). Before moving to Utrecht University Mathilde was a researcher at Rathenau Instituut, the Erasmus University Rotterdam (RSM) and the Journalism school of Utrecht (HU).

Vareska van de Vrande

Vareska van de Vrande is Professor of Collaborative Innovation and Business Venturing at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University. Vareska joined RSM in 2007 after completing a PhD in Industrial Engineering and Management Science at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Notes

1. The definition of “quality content” is always subjective and may differ depending on the perspective that is taken. What we refer to here when we speak of content quality is the strength of the editorial logic in content selection and the number of sources used and research done to produce it.

References

- Achtenhagen, L., Melesko, S., & Ots, M. (2018). Upholding the 4th estate—exploring the corporate governance of the media ownership form of business foundations. The International Journal on Media Management, 20(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2018.1482302

- Achtenhagen, L., & Raviola, E. (2009). Balancing tensions during convergence: Duality management in a newspaper company. The International Journal on Media Management, 11(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241270802518505

- Altheide, D. L., & Snow, R. P. (1979). Media logic. SAGE.

- Ansari, S., & Phillips, N. (2011). Text me! New consumer practices and change in organizational fields. Organization Science, 22(6), 1579–1599. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0595

- Baker, C. E. (2007). Media concentration and democracy: Why ownership matters. Cambridge University Press.

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Belair-Gagnon, V., Lewis, S. C., & Agur, C. (2020). Failure to launch: Competing institutional logics, intrapreneurship, and the case of chatbots. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 25(4), 291–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmaa008

- Benson, R., Neff, T., & Hessérus, M. (2018). Media ownership and public service news: How strong are institutional logics? The International Journal of Press/politics, 23(3), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161218782740

- Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. Macmillan.

- Besharov, M. L., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 364–381. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0431

- Bourdieu, P. (2005). “The political field, the social science field, and the journalistic field.” In Benson Rodney and Erik Neveu (ed.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field (pp. 29–48). Cambridge: Polity.

- Brants, K. (2015). Van medialogica naar publiekslogica? In J. Bardoel & H. Wijfjes (Eds.), Journalistieke cultuur in Nederland (pp. 237–255). Amsterdam University Press.

- Brès, L., Raufflet, E., & Boghossian, J. (2018). Pluralism in organizations: Learning from unconventional forms of organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(2), 364–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12136

- Cannella, A. A., Jones, C. D., & Withers, M. C. (2015). Family-versus lone-founder-controlled public corporations: Social identity theory and boards of directors. Academy of Management Journal, 58(2), 436–459. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0045

- Christensen, C. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail. Harvard Business School Press.

- Christensen, C. M., & Bower, J. L. (1996). Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms. Strategic Management Journal, 17(3), 197–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199603)17:3<197:AID-SMJ804>3.0.CO;2-U

- Christensen, C. M., McDonald, R., Altman, E. J., & Palmer, J. E. (2018). Disruptive innovation: An intellectual history and directions for future research. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1043–1078. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12349

- Chung, C. N., & Luo, X. (2008). Institutional logics or agency costs: The influence of corporate governance models on business group restructuring in emerging economies. Organization Science, 19(5), 766–784. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0342

- Coates Nee, R. (2014). Social responsibility theory and the digital nonprofits: Should the government aid online news startups? Journalism, 15(3), 326–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913482553

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm. Prentice Hall.

- Demsetz, H. (1997). The firm in economic theory: A quiet revolution. The American Economic Review, 87(2), 426–429.

- Durand, R., & Thornton, P. H. (2018). Categorizing institutional logics, institutionalizing categories: A review of two literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 631–658. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0089

- Duran, P., Kammerlander, N., Van Essen, M., & Zellweger, T. (2016). Doing more with less: Innovation input and output in family firms. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1224–1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0424

- Edmondson, A. C., & McManus, S. E. (2007). Methodological fit in management field research. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1246–1264. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586086

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Friedland, R., & Alford, R. R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices and institutional contradictions. In W. W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). University of Chicago Press.

- Greenwood, R., Díaz, A. M., Li, S. X., & Lorente, J. C. (2009). The multiplicity of institutional logics and the heterogeneity of organizational responses. Organization Science, 21(2), 521–539. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0453

- Greenwood, R., & Empson, L. (2003). The professional partnership: Relic or exemplary form of governance? Organization Studies, 24(6), 909–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840603024006005

- Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.590299

- Greve, H. R., & Zhang, C. M. (2017). Institutional logics and power sources: Merger and acquisition decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 60(2), 671–694. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0698

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., & Namey, E. E. (2014). Applied thematic analysis. Sage.

- Hannan, M. T. (2010). Partiality of memberships in categories and audiences. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 159–181. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-021610-092336

- Hansmann, H. (1996). The ownership of enterprise. Harvard University Press.

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2003.10196729

- Hoffman, A. J. (1999). Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the US chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4), 351–371. https://doi.org/10.2307/257008

- Hwang, H., & Powell, W. W. (2009). The rationalization of charity: The influences of professionalism in the nonprofit sector. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54(2), 268–298. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2009.54.2.268

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kosterich, A. (2020). Managing news nerds: Strategizing about institutional change in the news industry. Journal of Media Business Studies, 17(1), 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1639890

- Kraatz, M. S., & Block, E. S. (2008). Organizational implications of institutional pluralism. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin (ed.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (Vol. 840, pp. 243–275). London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Lander, M. W., Heugens, P. P., & van Oosterhout, J. (2017). Drift or alignment? A configurational analysis of law firms’ ability to combine profitability with professionalism. Journal of Professions and Organization, 4(1), 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpo/jow011

- Lander, M. W., Koene, B. A., & Linssen, S. N. (2013). Committed to professionalism: Organizational responses of mid-tier accounting firms to conflicting institutional logics. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 38(2), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2012.11.001

- Leblebici, H., Salancik, G. R., Copay, A., & King, T. (1991). Institutional change and the transformation of inter-organizational fields: An organizational history of the US radio broadcasting industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 333–363. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393200

- Lischka, J. A. (2020). Fluid institutional logics in digital journalism. Journal of Media Business Studies, 17(2), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1699764

- Lounsbury, M. (2001). Institutional sources of practice variation: Staffing college and university recycling programs. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(1), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667124