ABSTRACT

The numbers of publications within the field of research on approaches to address conflicts in schools is rapidly growing, and it is now important to map influential theories, methods and topics that shape this research field. In addition, student teachers, teachers and teacher educators would benefit from it being easier to find research-based knowledge of how to address conflicts in schools. Therefore, a bibliometric study was carried out on 1126 publications that were published between 1996 and 2019 in this field. The study aimed at examining publication activity, geographic spread, and dominant research topics. The findings showed a positive trend in publication output from 2006 onwards. Research output was found to be dominated by the United States. However, the results also indicated an internationalization trend expressed in an increased geographic spread of publication output. Furthermore, six research topics were identified through cluster analyses and labelled ‘peace and value education’, ‘classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building’, ‘constructive conflict resolution’, ‘classroom management programmes’, ‘restorative justices and restorative approaches’, and ‘classroom challenges for teachers’. Within each research topic, a distinct number of publications were found that defined the core research.

Introduction

A systematic bibliometric study focussing exclusively on research in the research field of approaches to address conflicts in schools (ACS) has been lacking. Scholars from different disciplines, such as education, sociology, social psychology, and political sciences, have been interested in research questions relating to conflict resolution, conflict management, conflict transformation as well as peace education and peacebuilding (Zelizer Citation2015). Several have expressed a particular interest in conflict resolution education (Deutsch Citation1973, Citation2006), or in the way conflicts are dealt with in schools (Johnson and Johnson Citation1996, Citation2014). When searching existing bibliometric studies, the references that often recur concern conflict research (Sillanpää and Koivula Citation2010) and conflict management (Caputo et al. Citation2019; Ma, Lee, and Yu Citation2008). Sillanpää and Koivula (Citation2010), however, used publications from leading political science and international relations journals, thus focussing on contexts other than educational. In addition, the keywords Caputo et al. (Citation2019) and Ma, Lee, and Yu (Citation2008) used in their search were not related to education, learners, teachers or school. Consequently, their datasets consisted of publications relating to international, business and workplace conflicts. Even though schools are workplaces for many, we argue that the task of teachers, teacher educators, pupils and school leaders in managing conflicts occurring in classrooms, school playgrounds and other parts of the school has its own challenges. Previous research has confirmed that there is a broad and global acceptance of the idea of conflict being a multifaceted concept and the importance of studying approaches to address them in order to find new ways of constructively managing conflicts in the school (Bickmore Citation2001; Johnson and Johnson Citation1996). These challenges require research questions specifically focussing on addressing conflicts in schools.

In a time when the total number of publications is growing, researchers would benefit from a review of existing literature. Researchers often need to position themselves within a research field in order to clarify their contribution to it. Furthermore, teachers, teacher educators and student teachers might benefit from a solid overview of influential literature and central topics in the field of ACS so that their practices can be grounded in scientific knowledge. A bibliometric study on ACS can strengthen the field, as well as help researchers and practitioners to find useful publications. To address these gaps, we carried out two studies using bibliometric methods. The first study focussed backwards at the intellectual roots and the second at the research fronts of ACS. In this article, we report on the second of these two bibliometric studies.

In the first study (Hakvoort, Lindahl, and Lundström Citation2019)) we examined the intellectual base, i.e. the highly cited literature, of ACS research between 1996 and 2015 with author co-citation analysis. Thus, the first study (Hakvoort, Lindahl, and Lundström Citation2019)) focused on the influential ideas, topics, theories, and methods that have shaped ACS research. The main focus of the second bibliometric study, presented in this article, is publication activity, dominating research topics, and changes over time in a dataset consisting of 1126 publications in the field of ACS between 1996 and 2019. Thus, the focus of the present study is the topics of the actual research that has been conducted within the field of ACS and how it has changed over time. As such, the present study complements the first study by examining the published research in ACS, rather than the influential literature that has shaped the field. A secondary focus of the present study is the geographical spread of publications in ACS. Examining the geographical spread of publications in ACS is motivated by earlier studies pointing out that the concept of conflict and approaches to deal with them are culture and context dependent (Biton and Salomon Citation2006; Kupermintz and Salomon Citation2005; Lewis et al. Citation2005; Weinstein, Curran, and Tomlinson-Clarke Citation2003). For example, Salomon (Citation2008) argued that it is important to dinstinguish between three sociopolitical contexts in which peace education approaches can be discussed and problematized. That is, contexts of ethnopolitical conflicts, contexts of nonviolent intergroup tensions and contexts of relative tranquility.

Objectives and purposes

The study provides a broad overview of how publication activity and research topics in studies on approaches to address conflicts in schools (ACS) have changed over time between 1996 and 2019. Two research questions were posed:

1. How has the publication activity for ACS changed over time?

(a) What is the geographic spread of publications in ACS?

(b) How has the geographic spread changed over time?

2. Which research topics have dominated ACS, and how have these research topics changed over time?

Perspectives and methods

The multidisciplinary citation database Scopus was used to identify relevant studies. Scopus is claimed to provide better coverage of publications about social science research than other citation databases, such as SCI-Expanded, SSCI, and A&HCI (Norris and Oppenheim Citation2007). Although the Scopus citation database provides good coverage of the social sciences, it has an acknowledged bias towards studies from English-speaking countries. To identify and retrieve publications about approaches to address conflicts in schools, a set of search terms was defined with a method of combining them. We constructed a Boolean lexical query consisting of two blocks of search terms, one relating to the subject and the other relating to the context. We used truncation and included relevant variations for all search terms (Appendix 1).

Data resources

The search was restricted to publications in English language journals, classified as articles, conference proceedings, letters, notes and reviews, and published between 1996 and 2019. The period started in 1996 since that is as far back as cited references are indexed in the Scopus citation database. Using these filters, 1655 documents were retrieved. After screening the 1655 documents for noise, the final dataset consisted of 1126 publications in the field of ACS, and were downloaded from Scopus in August 2020. Publications that were non-ACS publications were regarded as noise, for example when reported studies focused on Higher Education Institutes (such as universities) and not school, as well as publications in the Journal of Dental Education and the Journal of Nursing Education.

Methods of analysis

In order to examine publication activity, geographic spread, and changes over time (research questions 1, 1a, and 1b), we utilized bar charts and dual axis bar and line charts, together with descriptive statistics.

To examine different research topics used in ACS and how these research topics have changed over time (research question 2), we applied a bibliometric time line technique based on cluster analysis, as described by Morris et al. (Citation2003), and used subject experts to validate the content of the clusters, i.e. to make sure that each cluster is topically coherent and relevant (Noyons Citation1999). The time line technique consists of three steps. First, the topical similarity between all 1126 documents is calculated on the basis of bibliographic coupling, a measure of topical similarity between documents (Kessler Citation1963). If two documents have at least one reference in common, they are considered to be bibliographically coupled. More references in common indicate a higher topical similarity between the bibliographically-coupled documents. We define the number of shared references between documents as the bibliographic coupling strength. Second, all 1126 documents are clustered on the basis of the bibliographic coupling strength with the clustering technique implemented in VOSviewer (Waltman et al., Citation2010), a software developed to analyse bibliometric data. Third, each cluster (i.e. research topic) is visualized as a time line with a stacked area chart so that we can observe and interpret changes over time.

In line with best practice in the bibliometric literature two subject experts (i.e. with more than 20 years of experience in the field) analyzed and validated the content of the clusters to determine that each cluster consisted of a coherent research topic that is relevant for the field of ACS (Noyons Citation1999). To interpet and convey the content of and the changes within each cluster, the two subject experts conducted an analysis of the content in each cluster to be able to get a good understanding of the meaning and context of the papers (Noyons Citation1999; Donthu Citation2021). This validation was an iterative process, in which the two subject experts read titles, abstracts and when needed the fulltexts of articles to identify a common denominator among the papers in each cluster, i.e. a research topic, providing an overarching description of the topical content of the cluster and labelling each cluster accordingly.

The analysis procedure was conducted as follows. First the abstracts of each cluster were placed in stacks of four consecutive timeperiods (i.e. two periods of eight years 1996–2003, and 2004–2011, and two periods of four years 2012–2015 and 2016–2019) and each stack was equally divided between the two subject experts. Then they read the abstracts individually and noted specific content (here referred to as sub-topics). Aiming at identifying occurring and reoccurring sub-topics in each cluster, the noted sub-topics were orally presented to each other. When both experts mentioned a sub-topic several times, the sub-topic was recorded as reoccurring and identified as central. It was also documented when in time the sub-topic occurred. To deepen our understanding of these central sub-topics in each cluster, readings of whole publications were sometimes needed. For each cluster, a narrative was created describing the content exemplified with publications reporting on sub-topics to enable a presentation of the clusters where both content and context is taken into consideration (Donthu et al. Citation2021).

Results and discussion

In the following sections, we present the results on publication activity () and geographic spread () through bar charts and dual axis bar and line charts, together with descriptive statistics. In the sections that follow, the six research topics found in the cluster analysis (through a bibliometric time line technique) will be presented by their labels and sizes (), in a two-dimensional space () and through cluster narratives of topical similarities.

Table 1. An overview of the six clusters, their size and labels.

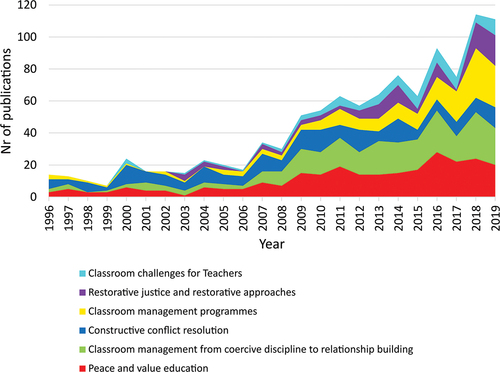

Figure 1. Longitudinal changes in publication activity in research on approaches to address conflicts in schools (ACS). The Y-axis denotes the number of publications and the x-axis denotes publication year.

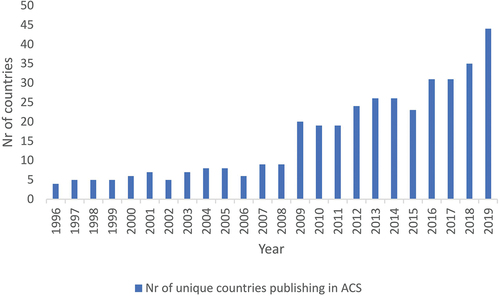

Figure 2. Longitudinal changes in the number of countries publishing research on ACS over time. The Y-axis denotes the number of unique countries that have published at least one publication and the x-axis denotes the year.

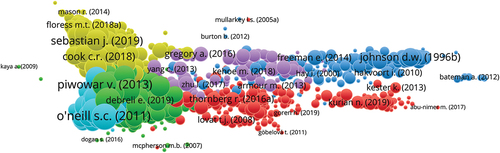

Figure 3. Bibliographic coupling map showing ASC research between 1996 and 2019 based on 1062 documents.

Publication activity

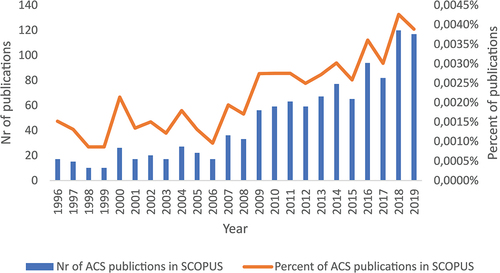

shows the publication activity for research in the field of ACS between 1996 and 2019. The publication activity remained more or less constant between 1996 and 2005 with no obvious trend. However, from 2006, we can see a positive trend in publication activity. On average, the volume of publications increased by approximately 6.6 publications each year between 2006 and 2019. To find whether the observed trend in ACS reflects a real change in publication activity, and is not a consequence of indexing effects (i.e. changes in the volume of literature indexed in the Scopus database), both absolute publication count and the percentage of publications relative to the total number of publications in the Scopus database were plotted (Danell and Danell Citation2009). The absolute number of articles and the percentage of articles correspond moderately well, indicating that the observed increase from 2006 onwards is real and not a consequence of indexing effects.

Geographic spread and internationalization

Research into ACS was started, and had its early development, in the United States by researchers such as Johnson and Johnson (Citation1989, Citation1996) and Deutsch (Citation1949, Citation1973). Regarded as founders of the field, publications during early developments came from scholars from the United States. This dominance turned out somewhat problematic since earlier studies have shown that discussing and dealing with conflict is culture and context dependent (Weinstein, Curran, and Tomlinson-Clarke Citation2003; Lewis et al. Citation2005). What works well in one context may not work in another. In this section, we examine (1) to what degree there is a geographic spread in the field and (2) how a geographic spread have changed over time. With geographic spread we mean how authorship of the publications in the field of ACS is distributed over countries. Remember that the dataset consists of publications in English language journals and proceedings. We are examining research that is often intended for an international audience, though some studies might have a national focus.

A country is defined as a producer of research if at least one author of the publication is affiliated with the country. This means that one publication can be counted more than once if researchers from at least two different countries have co-authored it. Among the 1126 documents, we identified output from 71 different countries. The initial list of countries was manually inspected for country name variations and changes were made accordingly to eliminate, for example, country name synonyms and country names not referring to actual countries. Further, 24 documents lacked metadata in the address-fields and were excluded from the analyses. The fifteen countries producing the highest number of publications about ACS were (1) United States (38.4%); (2) Turkey (9.9%); (3) Australia (7,5%); (4) United Kingdom (6.3%); (5) Canada (3.2%); (6) Israel (2.6%); (7) Germany (2.5%); (8) Norway (1.75%); (9) Spain (1.7%); (10) Netherlands (1.6%); (11) Sweden (1.5%); (12) Indonesia (1.4%); (13) Malaysia (1.4%); (14) Cyprus (1.3%); and (15) South Africa (1.0%). The distribution of publications from specific countries was greatly skewed with a few highly productive countries and many countries with a small number of publications credited to them. The mean publication output per country was 17.5 and the median was 4.

To find how publication activity has changed over time with regard to geographic spread, we plotted the number of countries publishing research in ACS against time (). shows a growth in the number of countries producing research between 1996 and 2019. Notably, we can see a positive trend from about 2008 onwards, with an average increase of 3.6 new countries each year publishing research in this field. This indicates that even though research in this field is dominated by researchers from the United States, we can observe an internationalization trend where the number of countries producing research into ACS has been increasing.

Research topics

A bibliometric time line technique based on cluster analysis was carried out to examine the research topics of the 1126 publications. To avoid very small clusters, we restricted the cluster size to a minimum of at least 10 publications, as described by Morris et al. (Citation2003). Sixty-four documents were not bibliographically coupled with any other documents in the dataset and therefore excluded from the analysis (Morris et al. Citation2003). The cluster analysis resulted in six clusters comprising 1062 of the 1126 publications. As such, each cluster consisted of topically similar publications that were published between 1996 and 2019, and represented coherent research topics in the field of ACS. See for an overview of the six clusters, their sizes and labels. See for an overview of the clusters in a two-dimensional space, i.e. a bibliometric map of ACS.

provides a broad overview of how the six clusters (denoted by color), i.e. the six main research topics in the field of ACS, are topically related. Each cluster consists of nodes and each node represents a published paper in ACS. Nodes with the same color belong to the same cluster:

Red nodes belong to cluster 1: Peace and value education.

Green nodes belong to cluster 2: Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building.

Blue nodes belong to cluster 3: Constructive conflict resolution.

Yellow nodes belong to cluster 4: Classroom management programmes.

Purple nodes belong to cluster 5: Restorative justice and restorative approaches.

Turqouise nodes belong to cluster 6: Classroom challenges for Teachers.

The distance between nodes indicates topical similarity (nodes that are closer have a higher bibliographic coupling strength). Nodes that are closer to each other can be considered more topically similar than nodes that are further apart (Waltman et al. Citation2010). The distance between clusters can be given a similar interpretation. Clusters that are closer to each other can be interpreted as more topically similar to each other than clusters that are further apart. As can be observed in , cluster 2 (green), 4 (yellow), and 6 (turqouise) are positioned in close proximity to each other on the left side of the map. While these are three distinct topics (i.e. clusters) in the field of ACS they all focus on different aspects of classroom management and have a strong interest in behavioural aspects with roots in behaviourism. The nodes in these three clusters seem to be positioned in tight and cohesive formations. That indicates homogeneous topics where researchers in these respective topics share a common knowledge base. On the upper center and right side of the map we have cluster 3 (blue) and 5 (purple). These two clusters are overlapping to a large extent, i.e. nodes of cluster 3 can be found in cluster 5 and vice versa. This indicates that researchers in these topics are building their research on similar sources and that they might be focusing on similar research problems. At the lower center to the right side of the map we find cluster 1 (red) partly overlapping with cluster 2 (green), 3 (blue), and 5 (purple). The shape of cluster 1 is similar with the shape of cluster 3 and 5. These three clusters are less homogeneous and more spread out compared with cluster 2, 4 and 6, at the left side of the map. This suggest that research in these topics, i.e. Peace and value education, Constructive conflict resolution, and Restorative justice and restorative approaches, is more topically heterogeneous than research in the topics Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building, Classroom management programmes, and Classroom challenges for Teachers.

Changes over time

To see the changes over time, we plotted all clusters in a stacked area chart where the y-axis denotes the number of publications and the x-axis denotes publication year ().

In , the number of publications in the six clusters are plotted against time to show longitudinal change by research topics in research into ACS between 1996 and 2019. Each cluster is represented by a color. A decrease in the height of the area in a cluster from one year to the next indicates a reduction in the numbers of publications and vice versa. The topical similarities in each cluster will now be discussed.

Cluster narratives of topical similarities

For each cluster, a cluster narrative was written. These narratives follow a similar structure. Every narrative starts with information about the total number of publications, the year of the first publication, and a short note about when the number of publications showed an increase or decrease. Then a description is provided of the reoccurring sub-topics exemplified with publications reporting on these sub-topics in order to present the content and context of the cluster (Donthu et al. Citation2021). Cluster narratives conclude with references to geographic spread.

Cluster 1 Peace and value education

Cluster 1 consisted of 263 publications. During the first eight years (1996–2003), there were only 29 publications in cluster 1. The first publication was dated 1996 (Solomon et al. Citation1996). After 2003, a slow but clear increase in publication activity can be seen.

In this cluster, sub-topics such as pro-social behaviour, socio-emotional learning, social and moral skills and values, collaborative learning and community building were addressed. For example, Adalbjarnardottir and Selman (Citation1997) carried out a series of studies on perspective-taking in interpersonal relationships. The development of perspective-taking has been seen as a valuable social skill for constructive conflict resolution. Other scholars explored the competences and skills that teachers and student teachers need in relation to peace and value education (Lovat and Clement Citation2008; Revell and Arthur Citation2007) in order to help them prevent and manage violent incidences in schools (Jenkins, Citation2007; Williams, Citation2017).

The authors of this cluster acknowledged the start and growth of peace and value education (Jenkins Citation2013; Saripudin and Komalasari Citation2015; Wintersteiner Citation2013) and conflict resolution graduate programmes all around the world (Zelizer Citation2015). Zelizer (Citation2015) found that an important goal for students was to learn how to manage diversity in order to prevent potential violence. Fundamental elements that could be included in such training were described and discussed. Comprehensive peace education was discussed as a generalized approach to all social learning and formal education. Several studies shared their vision of the development of peace education programmes, their core elements, theories and focus.

Kupermintz and Salomon (Citation2005) claimed that peace education in contexts like Northern Ireland, Kosovo and Israel differs from peace education in regions of relative peace. It was argued that longlasting conflicts within protracted wars can be viewed as collective and not interpersonal. In collective conflicts, the participants’ knowledge of the adversary’s collective narrative can grow when opposite parties express their views (Kupermintz and Salomon Citation2005; Biton and Salomon Citation2006). Zembylas, Charalambous, and Charalambous (Citation2012) addressed the unease with which Greek-Cypriot teachers worked with one another and their efforts at peace building in a post-conflict context. During recent years, a continuing interest in the contribution of teachers to peace building processes in post-conflict countries has been apparent (Lauritzen Citation2016). In , it can be noted that cluster 1 seems to consist of two sub-groups with the publications on research in countries with longlasting conflicts (e.g. Kurian and Kester Citation2019) grouped together at the right side of the figure.

Furthermore, studies were carried out in an increasing number of different countries (Abu-Nimer, Nasser, and Ouboulahcen Citation2016; Saripudin and Komalasari Citation2015; Lauritzen Citation2016).

Cluster 2 Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building

Cluster 2 consisted of 257 publications. It can be seen that the earliest publications are from 1996 (). During the first eight years (1996–2003), there were only 19 publications in cluster 2. A clear increase in the number of publications each year occurred from 2006.

How teachers manage the classroom is assumed to be strongly associated with student achievement. Research also found other variables that influence student achievement, such as subject teaching skills, teachers’ views on classroom management and students’ views on their responsibilities (Wilks Citation1996). In early publications, a clear interest in defining classroom management was shown (Lewis et al. Citation2005). Even though definitions vary, ‘they usually included actions taken by the teacher to establish order, engage students, or elicit their cooperation’ (Emmer and Stough Citation2001). Behavioural aspects, such as disruptive classroom behaviour and behaviour management, were given a central role and relate to an interest in discipline. Researchers concluded that training in teacher education resulted in an increased sense of self-confidence and greater preparedness for the teacher profession (Emmer and Stough Citation2001).

Students’ lack of discipline is considered a serious concern by both teachers and students in different contexts and thus needs to be addressed (Lewis et al. Citation2005). Teachers were, for example, found to be concerned about students’ distractibility in relation to subject teaching, student on-task behaviour, and adherence to classroom rules (Arbuckle and Little Citation2004; Clunies-Ross et al., Citation2008; Ding et al. Citation2008).

A continuing interest can be seen in teachers’ classroom discipline strategies. Lewis et al. (Citation2005) described two discipline styles used by teachers, the so-called ‘coercive’ discipline related to punishment and aggression, and the ‘relationship-based discipline’ focussing on the relationship with students. Teachers’ predominant disciplinary techniques and the impact of these techniques have been studied. Some findings reported on newly examined teachers who used punishment more than experienced teachers (Durcharme and Shecter, Citation2011). Discipline was often used after students were perceived as misbehaving, though we observed a growing interest in early intervention and prevention over time, alongside a shift towards teachers’ actions that create optimal educational climates (Jennings and Greenberg Citation2009).

Reupert and Woodcock (Citation2010) studied student teachers’ use of reward, corrective (initial and later) and preventive classroom management strategies, and to what extent they found these strategies effective. Other scholars investigated the strategies teachers used that had been very successful in creating a positive classroom climate (Van Tartwijk et al. Citation2009). They discussed the importance of differentiating between care, external control (related to rewards) and behaviour control (related to social rules and regulations) with regard to effective teaching and reduction of misbehaviour (Nie and Lau Citation2009). The relational supportive teacher has been put forward in favour of the authoritarian teacher who uses external control and corrective strategies. Caring teacher behaviour, constructive feedback and a focus on the teacher-student relationship are all regarded as important aspects of a supportive climate for all pupils’ learning that increases their engagement. Some studies reported that student misbehaviour was found to increase when teachers used coercive disciplinary and aggressive strategies (Lewis et al. Citation2005; Reupert and Woodcock Citation2010). In order to turn aggressive strategies into the building of sustainable relationships with students, teachers need space to reflect together, to be supported during this change and expand their professional work as teachers (Lewis et al. Citation2005).

Classroom management is continually regarded as vital for student achievement and effective learning as well as for teachers’ self-efficacy. New teachers need to be prepared for classroom management and the gap between pre-service and in-service teacher education needs to be closed (Farrell Citation2012; Haggarty and Postlethwaite Citation2012). Piwowar, Thiel, and Ophardt (Citation2013) concluded that the participants in their studies had more knowledge about classroom management after training and felt better prepared for the type of minor disturbances and distractions that could occur in the classroom.

Several studies used questionnaires with descriptions of classroom management strategies drawn from the literature (O’Neill and Stephenson Citation2012; Reupert and Woodcock Citation2010). Participants were asked whether they used these strategies and, if so, whether they felt confident using them and whether they were effective. Others used semi-structured interviews to increase their insight into teachers’ perceptions of student misbehaviour and management strategies (Sun and Shek Citation2012), or observations from video-filming (Van den Bogert et al. Citation2014). The studies in this cluster produced interesting lists of classroom management strategies. Reoccurring strategies were punishment, rewards, during-class and after-class dialogues including students’ voices in working out the rules, aggression, and hinting. Classroom misbehaviour, as the name suggests, is mostly assumed to have a negative impact on teaching and learning.

The rapid development of the internet has motivated scholars to use video and virtual reality technology to investigate teachers’ classroom management expertise (Arvola et al. Citation2018; König, Citation2015; Lugrin et al. Citation2016; Weber et al. Citation2018). Classroom management and classroom management education continue to be regarded as playing a central role in a successful teaching career.

Furthermore, publications contributed to the described internationalisation process by studying the influence of cultural differences (Lewis et al. Citation2005; Romi et al. Citation2011) and presenting studies from different parts of the world (Fauth et al. Citation2014; Sun and Shek Citation2012).

Cluster 3 Constructive conflict resolution

Cluster three consisted of 201 publications. shows that publications were available from 1996 and, at the beginning of the period studied, this was the largest cluster in terms of number of publications when compared to the same years for clusters 1 and 2. The number of publications found in this cluster has been quite stable over the whole period 1996–2019.

We recognized several well-known scholars such as Johnson and Johnson (Citation1996, Citation2001), and Bickmore (Citation1998, Citation1999, Citation2001), as well as scholars associated with them (Stevahn et al. Citation1996; Dudley, Johnson, and Johnson Citation1996). These publications shared a concern about the way discipline was discussed in society and by scholars, as well as about the existing violence in schools. There is great interest in providing new ways of managing conflicts by training both teachers and students in constructive conflict resolution. The promotion of constructive conflict resolution in the form of programmes or models and its effects are often the aim of the studies. In 1996, the first publications reported on evaluations of conflict resolution programmes, in which students were trained to negotiate and mediate to manage conflicts constructively (Garibaldi, Blanchard, and Brooks Citation1996; Stevahn et al. Citation1996; Dudley, Johnson, and Johnson Citation1996). In the same year, Johnson and Johnson (Citation1996) published a review of conflict resolution and mediation programmes. They looked at the 1960s, during which interest in developing programmes started. By 1996, already thousands of different programmes for conflict resolution existed in the United States. Besides examining methodological and conceptual problems with the research on conflict resolution and mediation programmes, Johnson and Johnson (Citation1996, abstract) also concluded that ‘(a) conflicts among students do occur frequently in schools; (b) untrained students by and large use conflict strategies that create destructive outcomes by ignoring the importance of their ongoing relationships; (c) conflict resolution and peer mediation programs do seem to be effective in teaching students cooperative problem-solving approaches such as integrative negotiation and mediation procedures; (d) after training, students tend to use these conflict strategies, which generally leads to constructive outcomes; and (e) students’ success in resolving their conflicts constructively tends to result in reducing the numbers of student-student conflicts referred to teachers and administrators, which, in turn, tends to reduce suspensions.’

Publications about programme evaluations continued in the following years (Stevahn et al. Citation1997; Cunningham et al. Citation1998) and several reviews have been published since with descriptions and evaluations of various conflict resolution programmes for schools (Bodine and Crawford Citation1998; Jones Citation2004; Sandy and Cochran Citation2000). Formal training in conflict resolution for teachers, students and student teachers was regarded necessary in order to come to an understanding of how to manage conflicts constructively – life experience was not enough.

The publications describe an interest in school-wide implementation of programmes or models for managing conflicts constructively and studying its effects (Daunic et al. Citation2000; Davidson and Wood Citation2004; Flecknoe Citation2005; Garrard and Lipsey Citation2007; Tjosvold, Citation2004; Stevahn Citation2004; Stevahn, Munger, and Kealey Citation2005). For example, Stevahn (Citation2004) studied a curriculum-integrated approach to the Teaching Students To Be Peacemakers (TSP) programme for teaching conflict resolution and peer mediation, and reported on its effectiveness. Davidson and Wood (Citation2004) developed the Conflict Resolution Model to train pupils. As well as constructive conflict resolution at school, Vestal and Jones (Citation2004) also investigated the training programmes for student teachers offered during teacher education. Studies emphasized the importance of conflict partners recognizing underlying issues (Davidson and Wood Citation2004) as well as developing perspective-taking (Gehlbach Citation2004). Johnson and Johnson (Citation2001) found that in peer mediation there were mainly two strategies used, ‘avoidance’ and ‘saying I am sorry’. The integrated way of addressing conflicts where motives, feelings and thoughts were shared was not used among peers. In general, trained teachers and students were found to be more able to use a variety of strategies in conflict situations and showed a greater conceptual understanding of conflicts, disagreements, different perspectives and opinions (Akgun and Araz, Citation2014). There appears to have been increased interest in the idea that a deeper understanding of conflicts can be developed by combining cognitive knowledge with experience, learning by doing, exercises and drama in the form of role play. There seems to have been a change from teacher-centred to learner-centred approaches, with scholars investigating the effect of this change on conflict resolution. It is regarded as important for teachers to solve conflicts with students effectively without damaging their relationship with the student, losing the cooperation of students or disrupting the educational process. With regard to studying the strategies teachers use to manage conflicts, the dual concern theory (Blake and Mouton, Citation1964), with its five strategies ‘avoiding’, ‘accommodating’, ‘compromising’, ‘competing’ and ‘collaborating’ is often used in empirical analyses (Balay Citation2007).

The increased use and development of the internet resulted in a number of publications reporting on the construction of large-scale questionnaires such as the Conflict Resolution Questionnaire (CRQ) (Henning Citation2004). Furthermore, the possibility of offering online conflict resolution programmes and training has been studied (Mauricio, Citation2005).

In cluster 3, we observed an increase in context diversity as several countries contributed research to this cluster (e.g. Turkey, China, Colombia, Israel, Palestine, Sweden, and Tanzania). In other words, knowledge has been consolidated and nuanced with new examples and data from different cultural contexts and different school infrastructures (Ndijuye Citation2019; Okada and Matsuda Citation2019; Sánchez and Chamucero Citation2017; Wang et al. Citation2014).

Cluster 4 Classroom management programmes

The total number of publications in cluster 4 was 167, with publication activity following a similar pattern to that in cluster 2, with a few publications available during the first eight years from 1996 (11 publications) followed by a clear increase occurring in 2010.

The studies in this cluster investigated the implementation of different classroom management programmes. For example, programmes such as the Incredible Years (IY) Teacher Classroom management training (TCM) (Reinke et al. Citation2014; Webster‐Stratton, Jamila Reid, and Stoolmiller Citation2008), Multi-Tiered Support (MTS) (Simonsen et al. Citation2014), Effective Behavioral Support (EBS) and a School-Wide Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support programme (SWPBIS) (Nelson et al., Citation2002) were implemented and tested for their effect. Korpershoek et al. (Citation2016) published a meta-analysis that included 54 controlled classroom management interventions. Results showed that providing teachers with positive classroom strategies resulted in greater social competence and self-regulation of their students. The researchers concluded that students’ learning benefited from these strategies. In a few computer-based studies, online classroom management problems were offered as practical training for students teachers (Hummel et al. Citation2015). In cluster 4, there were also international, i.e. non-United States, publications, for example Hummel et al. (Citation2015) and Korpershoek (Citation2016) (both Dutch).

Cluster 5 Restorative justice and restorative approaches

Cluster 5 contains a total of 95 publications. During the first seven years of the studied period, no publications relating to this topic were found. The first publication was dated 2003. Restorative justice and restorative approaches developed as an answer to the traditional punitive justice system and provide a chance to reflect on existing practices of behaviour management (Morrison, Blood, and Thorsborne Citation2005). Several studies discussed the concepts of ‘justice’ and ‘restorative’ in relation to school practices. While the concept of restorative justice is often used in the judicial context, restorative approaches or practices have become commonly used in relation to schools to avoid associations with crime and the judicial system (Sellman, Cremin, and McCluskey Citation2013; Vaandering Citation2011). However, Vaandering (Citation2011) argued that a broader understanding of justice is justified. She reiterated that justice relates to the recognition ‘that all humans are worthy and to be honoured because they are human’ (Vaandering Citation2011, 320). Therefore, it is important to pair the term ‘restorative’ with the word ‘justice’ instead of replacing ‘justice’ with ‘practice’ or ‘approach’. Restorative justice and restorative practice are based on strengthening the social capital of a community, the maintenance of relationships and the belief that people are able to consider how their behaviour affects themselves and others. Misconduct is not regarded as violating school rules but rather as violating and harming people and their relationships. Scholars, concerned about the harm done and the damage to relationships, felt obliged to develop an approach that would focus on healing harm, repairing relationships, finding meaningful forms of justice for both victim and offender, and improving social conditions (Selman et al., Citation2013). Most restorative justice programmes or restorative approaches adopted whole classroom or whole school approaches as they were found to result in more effective implementation. In several cases, even communities around the school were involved. Scholars have underlined the importance of a wide perspective that includes periods before, during and after the conflict and criminal activities. A variety of different educational designs such as dialogue circles, collaborative learning, and student participation were discussed as fundamental elements that could be used both as reactive or proactive instruments.

Restorative justice and practices can be understood partly as an answer to the traditional punitive justice system (Ryan and Ruddy, Citation2015) and partly as taking inspiration from aboriginal practices with healing circles and a focus on maintaining peace in an equal world (Britto and Reimund, Citation2013).

Cluster 6 Classroom challenges for Teachers

In cluster 6, a total of 79 publications were found over the whole period of study (1996–2019). The scholars in this cluster were concerned with the declining levels of teachers’ job satisfaction and the increase in levels of burnout among teachers. They all agreed that the teaching profession is stressful with many demands, including emotional management and work overload. Issues that were studied included teachers’ motivation to leave the teaching profession (Skaalvik and Skaalvik Citation2011), classroom challenges for new teachers (Dicke et al., Citation2014), self-efficacy as a protective factor against burnout (Aloe at al., Citation2014) and teachers’ stress management and wellbeing (Harris et al., Citation2016). Teachers’ emotions were assumed to be associated with their wellbeing and the quality of their teaching practice (Hagenauer, Hascher, and Volet Citation2015). Students’ behaviour and classroom management skills were often viewed as influencing factors.

Conclusion

In this study, we examined how much research is published (publication activity), where research is carried out (geographic spread), and research fronts (dominant and leading research topics and sub-topics) in ACS over a period between 1996 and 2019. The results showed no obvious trend in publication activity between 1996 and 2005. However, between 2006 and 2019 we saw a positive trend in publication output, with an average increase in publication numbers to 6.6 publications per year in the field of ACS.

Examining the geographic spread and how this geographic spread has changed between 1996 and 2019, we found that the United States are dominating the research output in the field of ACS. However, at the same time, our analyses of changes over time indicated an internationalization trend where the number of countries producing ACS research is increasing. We found that the number of countries producing research in ACS showed a positive trend from about 2008 onwards, with an average increase of 3.6 new countries each year producing research in this field. We conclude that there may be an internationalization trend expressed as an increase in geographic spread in ACS.

Finding six different clusters, representing dominant and leading research topics, strengthens the common view of scholars in this field that conflict is a multifaceted concept and can be approached from many different angles. Some topics discovered have been stable with regard to numbers of publications over the time period (cluster 3 ‘Constructive conflict resolution’), while others have seen an increase in numbers of publications (cluster 1 ‘Peace and value education’, cluster 2‘Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building’ and cluster 4 ‘Classroom management programmes’), with new topics appearing too, later in the studied period (cluster 5 ‘Restorative justice and restorative approaches’ and cluster 6 ‘Classroom challenges for teachers’). Research into, and practise of, ACS has been a response to the increasing violence in schools as well as an answer to the many challenges teachers in different contexts face when leading a group of pupils (collective) in which every pupils’ needs and voice matters.

The publications in the four largest clusters (‘Peace and value education’, ‘Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building’, ‘Constructive conflict resolution’ and ‘Classroom management programmes’) clearly contributed to the geographic spread with an increasing number of studies from other countries than the United States. The authors of publications found in cluster 5 (‘Restorative justice and restorative approaches’) referred, in their explanations of the roots of this upcoming practice, to the practices within aboriginal communities.

The increasing geographic spread of ACS research is very encouraging. As various scholars have already pointed out, dealing with and discussing conflict is culture and context dependent (Kupermintz and Salomon Citation2005; Lewis et al. Citation2005; Salomon Citation2008; Weinstein, Curran, and Tomlinson-Clarke Citation2003). What works well in one context may not work in another. To further illustrate this, we choose to raise some educational policy changes in two different cultural contexts that have influenced how conflicts and conflict resolution was addressed in schools and teacher education. The examples from these two contexts are described in Appendix 2 and are intend to inspire. They describe how specific challenges in schools have urged policy makers to act by implementing educational policy changes. Unfortunately these changes led to unintended negative consequences which were subject for research on the effects of the changes. With thourough descriptions of context, scholars in different parts of the world can convert what others learned from these unintended consequences to their own context. In addition, conceptions do have different meanings in different contexts and need to be problematized by those involved. Measures that could lead to a significant contribution to this field are a) researchers including a description of the context in which they are carrying out their research, b) an increase of collaborations between scholars from different countries, and c) an increase of discussions between researchers and practitioners concerning lived situated-experiences.

With regard to the contents of the six discovered research topics (clusters), sub-topics could be observed. In some of them, there were clear changes in sub-topics over time showing a shift in research fronts within a research topic. The sub-topics are expressed through the research questions as well as the theoretical and methodological choices of the researcher. In cluster 1, we noticed two clear sub-topics in research on peace and value education, that 1) define and determine peace and value education, and 2) position peace education in the context of intractable conflicts. In cluster 2 (‘Classroom management from coercive discipline to relationship building’), a shift over time could be observed from studying coercive discipline towards relationship building. With this change, theoretical frameworks also shifted from behaviourism to social constructivism. In cluster 3 (‘Constructive conflict resolution’), the narrative was stable and consistent over the whole period. Issues on various ways of managing conflicts and training both teachers and students in constructive conflict resolution skills were central. Scholars agreed that, without training, it is almost impossible to address conflicts that have intensified as they require advanced conflict resolution skills. Students need educated teachers to guide them through a constructive conflict management process. During the most recent years of the time period, it could be noticed that the internet stimulated the use of online questionnaire and programme development. The focus of research in cluster 4 (‘Classroom management programmes’) has been the development and evaluation of different classroom management programmes. With the growth of the internet, online programmes have been developed and tested. Both cluster 5 (‘Restorative justice and restorative approaches’) and 6 (‘Classroom challenges for teachers’) are small clusters, and the research published during the later years in this period mainly confirmed and strengthened the findings of earlier studies in the cluster. It should also be emphasized that the first publication in cluster 5 was indexed 2003 and the publication activity in this cluster stadily increased from 2010. Restorative justice programmes and restorative approaches adopt a whole school approach, and in some cases even engage the surrounded community, for their work with addressing conflicts in school. They underline the importance of using a wide perspective with attention for what happens before, during and after conflicts. Both proactive and reactive means are included to build, maintain and repair relationships between actors in school and the community as well as to encourage responsibility for own actions.

Methodological Reflections

In this bibliometric study, we used the Scopus database, which is the largest citation database providing good coverage of the social sciences. In any publication search it is, however, possible to miss relevant publications. It takes time for a publication to be indexed, and there might be keywords used that are not covered by our search terms. Nevertheless, we believe that our dataset provides a representative picture of English language research on approaches to address conflicts in schools, for two reasons. First, the Scopus database is large and has substantial coverage of publications. Second, we used a recall-oriented Boolean query in combination with subject experts who manually screened the retrieved documents, which strengthened the dataset. We assume that potentially relevant publications that were missed would not radically change the findings but rather strengthen them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ilse Hakvoort

Ilse Hakvoort, Ph.D., is Associate Professor in education at the Department of Education and Special education at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research interest is constructive conflict resolution education in schools. Central in her work is how conflict situations can become learning experiences for pupils and teachers. She is currently involved in a research project on escalated conflicts, threats and violence against teachers

Jonas Lindahl

Jonas Lindahl, Ph.D., is Associate Professor in library and information science at the Department of Sociology at Umeå University, Sweden. In his research, Jonas Lindahl examines factors that affect academic socialization and career development. In addition, he is interested in the information value of bibliometric indicators, e.g., citation rates and publication volume, in contexts of predicting scientific achievements.

Agneta Lundström

Agneta Lundström is a senior lecturer in education at the Department of Applied Educational Sciences at the University of Umeå. Her research and teaching focus has been conflict resolution in the teacher education, and professional meetings with students in socio-emotional difficulties. She lectures university teachers in how to create an open democratic atmosphere among students to promote learning from experiences.

References

- Abu-Nimer, M., I. Nasser, and S. Ouboulahcen. 2016. “Introducing Values of Peace Education in Quranic Schools in Western Africa: Advantages and Challenges of the Islamic peace-building Model.” Religious Education. 111 (5): 537–554. doi:10.1080/00344087.2016.1108098.

- Adalbjarnardottir, S., and R.L. Selman. 1997. ““I Feel I Have Received a New Vision:” an Analysis of Teachers’ Professional Development as They Work with Students on Interpersonal Issues.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 13 (4): 409–428. doi:10.1016/s0742-051x(96)00036-4.

- Akgun, S., and A. Araz. 2014. “The Effects of Conflict Resolution Education on Conflict Resolution Skills, Social Competence, and Aggression in Turkish Elementary School Students.” Journal of Peace Education. 11 (1): 30–45. doi:10.1080/17400201.2013.777898.

- Aloe, A M., L C. Amo, and M E. Shanahan. 2014. “Classroom Management Self-Efficacy and Burnout: A Multivariate Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 26 (1): 101–126. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9244-0.

- Arbuckle, C., and E. Little. 2004. “Teachers’ Perceptions and Management of Disruptive Classroom Behaviour during the Middle Years (Years Five to Nine).” Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology. 4: 59–70.

- Arvola, M., M. Samuelsson, M. Nordvall, and E.L. Ragnemalm. 2018. “Simulated Provocations: A Hypermedia Radio Theatre for Reflection on Classroom Management.” Simulation & Gaming. 49 (2): 98–114. doi:10.1177/1046878118765594.

- Balay, R. 2007. “Predicting Conflict Management Based on Organizational Commitment and Selected Demographic Variables.” Asia Pacific Education Review. 8 (2): 321–336. doi:10.1007/bf03029266.

- Bickmore, K. 1998. “Teacher Development for Conflict Resolution [Maple Elementary School].” Alberta Journal of Educational Research. 44 (1): 53.

- Bickmore, K. 1999. “Elementary Curriculum about Conflict Resolution: Can Children Handle Global Politics?” Theory & Research in Social Education. 27 (1): 45–69. 1999.1050586. doi:10.1080/00933104

- Bickmore, K. 2001. “Student Conflict Resolution, Power “Sharing” in Schools, and Citizenship Education.” Curriculum Inquiry. 31 (2): 137–162. doi:10.1111/0362-6784.00189.

- Biton, Y., and G. Salomon. 2006. “Peace in the Eyes of Israeli and Palestinian Youths: Effects of Collective Narratives and Peace Education Program.” Journal of Peace Research. 43 (2): 167–180. doi:10.1177/0022343306061888.

- Blake, R., and J. Mouton. 1964. The managerial grid: The key to leadership excellence, 350. Houston: Gulf Publishing Co.

- Bodine, R.J., and D.K. Crawford. 1998. The Handbook of Conflict Resolution Education. A Guide to Building Quality Programs in Schools. Jossey-Bass Inc. Publishers.

- Britto, S, and M E. Reimund. 2013. “Making Space for Restorative Justice in Criminal Justice and Criminology Curricula and Courses.” Contemporary Justice Review 16 (1): 150–170. doi:10.1080/10282580.2013.769301.

- Caputo, A., G. Marzi, J. Maley, and M. Silic. 2019. “Ten Years of Conflict Management Research 2007-2017.” International Journal of Conflict Management. 30: 87–110. doi:10.1108/IJCMA-06-2018-0078.

- Clunies‐Ross, P., E. Little, and M. Kienhuis. 2008. “Self‐reported and Actual Use of Proactive and Reactive Classroom Management Strategies and Their Relationship with Teacher Stress and Student Behaviour.” Educational Psychology. 28 (6): 693–710. doi:10.1080/01443410802206700.

- Cunningham, C.E., L.J. Cunningham, V. Martorelli, A. Tran, J. Young, and R. Zacharias. 1998. “The Effects of Primary Division, Student‐mediated Conflict Resolution Programs on Playground Aggression.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 39 (5): 653–662.

- Danell, J.A., and R. Danell. 2009. “Publication Activity in Complementary and Alternative Medicine.” Scientometrics. 80 (2): 539–551. doi:10.1007/s11192-008-2078-8.

- Daunic, A.P., S.W. Smith, T. Rowand Robinson, M.D. Miller, and K.L. Landry. 2000. “School-wide Conflict Resolution and Peer Mediation Programs: Experiences in Three Middle Schools.” Intervention in School and Clinic. 36 (2): 94–100. doi:10.1177/105345120003600204.

- Davidson, J., and C. Wood. 2004. “A Conflict Resolution Model.” Theory into Practice. 43 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4301_2.

- Deutsch, M. 1949. “A Theory of Cooperation and Competition.” Human Relations. 2: 129–151. doi:10.1177/001872674900200204.

- Deutsch, M. 1973. The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes. Yale University Press.

- Deutsch, M. 2006. Cooperation and Competition. In M. Deutsch and P.T. Coleman and

- Dicke, T, et al. 2014. ”Self-Efficacy in Classroom Management, Classroom Disturbances, and Emotional Exhaustion: A Moderated Mediation Analysis of Teacher Candidates.” Journal of Educational Psychology 106 (2): 569.

- Ding, M., Y. Li, X. Li, and G. Kulm. 2008. “Chinese Teachers’ Perceptions of Students’ Classroom Misbehaviour.” Educational Psychology. 28 (3): 305–324. doi:10.1080/01443410701537866.

- Donthu, N., S. Kumar, D. Mukherjee, N. Pandey, and W. M. Lim. 2021. “How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research. 133: 285–296. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070.

- Ducharme, J M., and C Shecter. 2011. “Bridging the Gap Between Clinical and Classroom Intervention: Keystone Approaches for Students with Challenging Behavior.” School Psychology Review 40 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1080/02796015.2011.12087716.

- Dudley, B.S., D.W. Johnson, and R.T. Johnson. 1996. “Conflict‐resolution Training and Middle School Students’ Integrative Negotiation Behavior.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 26 (22): 2038–2052. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01786.x.

- Emmer, E.T., and L.M. Stough. 2001. “Classroom Management: A Critical Part of Educational Psychology, with Implications for Teacher Education.” Educational Psychologist. 36 (2): 103–112. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3602_5.

- Farrell, T.S. 2012. “Novice‐service Language Teacher Development: Bridging the Gap between Preservice and In‐service Education and Development.” Tesol Quarterly. 46 (3): 435–449. doi:10.1002/tesq.36.

- Fauth, B., J. Decristan, S. Rieser, E. Klieme, and G. Büttner. 2014. “Student Ratings of Teaching Quality in Primary School: Dimensions and Prediction of Student Outcomes.” Learning and Instruction. 29: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2013.07.001.

- Flecknoe, M. 2005. “What Does Anyone Know about Peer Mediation?” Improving Schools. 8 (3): 221–235. doi:10.1177/1365480205060437.

- Garibaldi, A., L. Blanchard, and S. Brooks. 1996. “Conflict Resolution Training, Teacher Effectiveness, and Student Suspension: The Impact of a Health and Safety Initiative in the New Orleans Public Schools.” Journal of Negro Education. 65: 408–413. doi:10.2307/2967143.

- Garrard, W.M., and M.W. Lipsey. 2007. “Conflict Resolution Education and Antisocial Behavior in US Schools: A Meta‐analysis.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly. 25 (1): 9–38. doi:10.1002/crq.188.

- Gehlbach, H. 2004. “Social Perspective Taking: A Facilitating Aptitude for Conflict Resolution, Historical Empathy, and Social Studies Achievement.” Theory & Research in Social Education. 32 (1): 39–55. doi:10.1080/00933104.2004.10473242.

- Hagenauer, G., T. Hascher, and S.E. Volet. 2015. “Teacher Emotions in the Classroom: Associations with Students’ Engagement, Classroom Discipline and the Interpersonal teacher-student Relationship.” European Journal of Psychology of Education. 30 (4): 385–403. doi:10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0.

- Haggarty, L., and K. Postlethwaite. 2012. “An Exploration of Changes in Thinking in the Transition from Student Teacher to Newly Qualified Teacher.” Research Papers in Education. 27 (2): 241–262. doi:10.1080/02671520903281609.

- Hakvoort, I. , Lindahl, J. , and Lundström, A. Author (2019) “A bibliometric review of Approaches to Address conflicts in Schools: Exploring the Intellectual base.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 37(2) 123–145 doi:10.1002/crq.21266)

- Harris, A R., et al.$3$2 2016. ”Promoting Stress Management and Wellbeing in Educators: Feasibility and Efficacy of a School-Based Yoga and Mindfulness Intervention.” Mindfulness 7 (1): 143–154. doi:10.1007/s12671-015-0451-2.

- Henning, M. 2004. “Reliability of the Conflict Resolution Questionnaire: Considerations for Using and Developing Internet-based Questionnaires.” The Internet and Higher Education. 7 (3): 247–258. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.06.005.

- Hummel, H., W. Geerts, A. Slootmaker, D. Kuipers, and W. Westera. 2015. “Collaboration Scripts for Mastership Skills: Online Game about Classroom Dilemmas in Teacher Education.” Interactive Learning Environments. 23 (6): 670–682. doi:10.1080/10494820.2013.789063.

- Jenkins, T. 2007. “Rethinking the Unimaginable: The Need for Teacher Education in Peace Education.” Harvard Educational Review 77 (3): 366–369. doi:10.17763/haer.77.3.m457gn127kp87882.

- Jenkins, T. 2013. “The Transformative Imperative: The National Peace Academy as an Emergent Framework for Comprehensive Peace Education.” Journal of Peace Education. 10 (2): 172–196. doi:10.1080/17400201.2013.790251.

- Jennings, P.A., and M.T. Greenberg. 2009. “The Prosocial Classroom: Teacher Social and Emotional Competence in Relation to Student and Classroom Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research. 79 (1): 491–525. doi:10.3102/0034654308325693.

- Johnson, D.W., and R.T. Johnson. 1989. Cooperation and Competition: Theory and Research. Interaction Book Company.

- Johnson, D.W., and R.T. Johnson. 1996. “Conflict Resolution and Peer Mediation Programs in Elementary and Secondary Schools. A Review of the Research.” Review of Educational Research. 66 (4): 459–506. doi:10.3102/00346543066004459.

- Johnson, D.W., and R.T. Johnson. 2001. “Peer Mediation in an inner-city Elementary School.” Urban Education. 36 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1177/0042085901362002.

- Johnson, D.W., and R.T. Johnson. 2014. “Conflict Resolution in Schools.” P. Coleman, M. Deutsch, and E.C. Marcus, edited by. Handbook of Conflict Resolution. Chapter 47. Jossey-Bass. https://media.wiley.com/assets/7241/03/c47-ConflictResolutioninSchools.pdfandgiventheirownpagenumbersfrom1-28

- Jones, T.S. 2004. “Conflict Resolution Education: The Field, the Findings and the Future.” Conflict Resolution Quarterly 22: 233–267. doi:10.1002/crq.100.

- Kessler, M.M. 1963. “Bibliographic Coupling between Scientific Papers.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology. 14 (1): 10–25.

- König, J. 2015. “Measuring Classroom Management Expertise (CME) of Teachers: A video-based Assessment Approach and Statistical Results.” Cogent Education. 2 (1): 991178. doi:10.1080/2331186x.2014.991178.

- Korpershoek, H., T. Harms, H. de Boer, M. van Kuijk, and S. Doolaard. 2016. “A meta-analysis of the Effects of Classroom Management Strategies and Classroom Management Programs on Students’ Academic, Behavioral, Emotional, and Motivational Outcomes.” Review of Educational Research. 86 (3): 643–680. doi:10.3102/0034654315626799.

- Kupermintz, H., and G. Salomon. 2005. “Lessons to Be Learned from Research on Peace Education in the Context of Intractable Conflict.” Theory into Practice. 44 (4): 293–302. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4404_3.

- Kurian, N., and K. Kester. 2019. “Southern Voices in Peace Education: Interrogating Race, Marginalisation and Cultural Violence in the Field.” Journal of Peace Education. 16 (1): 21–48. doi:10.1080/17400201.2018.1546677.

- Lauritzen, S.M. 2016. “Educational Change following Conflict: Challenges Related to the Implementation of a Peace Education Programme in Kenya.” Journal of Educational Change. 17 (3): 319–336. doi:10.1007/s10833-015-9268-y.

- Lewis, R., S. Romu, X. Qou, and Y.J. Katz. 2005. “Teachers’ Classroom Discipline and Student Misbehavior in Australia, China and Israel.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 21 (6): 729–741. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.008.

- Lovat, T., and N. Clement. 2008. “Quality Teaching and Values Education: Coalescing for Effective Learning.” Journal of Moral Education. 37 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1080/03057240701803643.

- Lugrin, J. L., M.E. Latoschik, M. Habel, D. Roth, C. Seufert, and S. Grafe. 2016. “Breaking Bad Behaviors: A New Tool for Learning Classroom Management Using Virtual Reality.” Frontiers in ICT. 3: 26. doi:10.3389/fict.2016.00026.

- Ma, Z., Y. Lee, and K. Yu. 2008. “Ten Years of Conflict Management Studies: Themes, Concepts and Realtionships.” International Journal of Conflict Management. 19 (3): 234–248. doi:10.1108/10444060810875796.

- Morris, S.A., G. Yen, Z. Wu, and B. Asnake. 2003. “Time Line Visualization of Research Fronts.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 54 (5): 413–422. doi:10.1002/asi.10227.

- Morrison, B., P. Blood, and M. Thorsborne. 2005. “Practicing Restorative Justice in School Communities: Addressing the Challenge of Culture Change.” Public Organization Review. 5 (4): 335–357. doi:10.1007/s11115-005-5095-6.

- Ndijuye, L.G. 2019. “Developing Conflict Resolution Skills among pre-primary Children: Views and Practices of Naturalized Refugee Parents and Teachers in Tanzania.” Global Studies of Childhood. doi:10.1177/2043610619832895.

- Nelson, J R., R M. Martella, and N Marchand-Martella. 2002. “Maximizing Student Learning: The Effects of a Comprehensive School-Based Program for Preventing Problem Behaviors.” Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 10 (3): 136. doi:10.1177/10634266020100030201.

- Nie, Y., and S. Lau. 2009. “Complementary Roles of Care and Behavioral Control in Classroom Management: The self-determination Theory Perspective.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 34 (3): 185–194. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.03.001.

- Norris, M., and C. Oppenheim. 2007. “Comparing Alternatives to the Web of Science for Coverage of the Social Sciences’ Literature.” Journal of Informetrics. 1 (2): 161–169. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2006.12.001.

- Noyons, E.C.M. 1999. Bibliometric Mapping as a Science Policy and Research Management Tool. Lleiden: DSWO Press.

- O’Neill, S., and J. Stephenson. 2012. “Does Classroom Management Coursework Influence pre-service Teachers’ Perceived Preparedness or Confidence?” Teaching and Teacher Education. 28 (8): 1131–1143. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.06.008.

- Okada, Y., and T. Matsuda. 2019. “Development of a Social Skills Education Game for Elementary School Students.” Simulation and Gaming. 50 (5): 598–620. doi:10.1177/1046878119880228.

- Piwowar, V., F. Thiel, and D. Ophardt. 2013. ““Training Inservice Teachers’ Competencies in Classroom Management. A quasi-experimental Study with Teachers of Secondary Schools.” “Teaching and Teacher Education. 30: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.09.007.

- Pritchard, J. 1969. “Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics?” Journal of Documentation. 25 (4): 348–349.

- Reinke, W.M., M. Stormont, K.C. Herman, Z. Wang, L. Newcomer, and K. King. 2014. “Use of Coaching and Behavior Support Planning for Students with Disruptive Behavior within a Universal Classroom Management Program.” Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 22 (2): 74–82. doi:10.1177/1063426613519820.

- Reupert, A., and S. Woodcock. 2010. “Success and near Misses: Pre-service Teachers’ Use, Confidence and Success in Various Classroom Management Strategies.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 26 (6): 1261–1268. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2010.03.003.

- Revell, L., and J. Arthur. 2007. “Character Education in Schools and the Education of Teachers.” Journal of Moral Education. 36 (1): 79–92. doi:10.1080/03057240701194738.

- Romi, S., R. Lewis, J. Roache, and P. Riley. 2011. “The Impact of Teachers’ Aggressive Management Techniques on Students’ Attitudes to Schoolwork.” The Journal of Educational Research. 104 (4): 231–240. doi:10.1080/00220671003719004.

- Ryan, T G., and S Ruddy. 2015. “Restorative Justice: A Changing Community Response.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 7 (2): 253–262.

- Salomon, G. 2008. “Peace Education: Its Nature. Nurture and the Challenges It Faces.” In Handbook for Building Cultures of Peace, edited by J. De Rivera, 168–186. New York: Springer Publishing.

- Sánchez, A.D.V., and L.E.V. Chamucero. 2017. “Education in Conflict Resolution Using ICT: A Case Study in Colombia.” Journal of Cases on Information Technology. 19 (2): 29–43. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000199.

- Sandy, S.V., and K.M. Cochran. 2000. “The Development of Conflict Resolution Skills in Children: Preschool to Adolescence.” In The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice, edited by M. Deutsch and P.T. Coleman, 316–342, Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Saripudin, D., and K. Komalasari. 2015. “Living Values Education in School’s Habituation Program and Its Effect on Student’s Character Development.” The New Educational Review. 39 (1): 51–62. doi:10.15804/tner.2015.39.1.04.

- Sellman, E., H. Cremin, and G. McCluskey, Eds. 2013. Restorative Approaches to Conflict in Schools: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Whole School Approaches to Managing Relationships. Routledge.

- Shepler, S., and J.H. Williams. 2017. “Understanding Sierra Leonean and Liberian Teachers’ Views on Discussing past Wars in Their Classrooms.” Comparative Education. 53 (3): 418–441. doi:10.1080/03050068.2017.1338641.

- Sillanpää, A., and T. Koivula. 2010. “Mapping Conflict Research: A Bibliometric Study of Contemporary Scientific Discourses.” International Studies Perspectives. 11 (2): 148–171. doi:10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00399.x.

- Simonsen, B., A.S. MacSuga-Gage, J. Freeman D.E. Briere III, T.M. Scott, T.M. Scott, G. Sugai, and G. Sugai. 2014. “Multitiered Support Framework for Teachers’ classroom-management Practices: Overview and Case Study of Building the Triangle for Teachers.” Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 16 (3): 179–190. doi:10.1177/1098300713484062.

- Skaalvik, E.M., and S. Skaalvik. 2011. “Teachers’ Feeling of Belonging, exhaustion, and Job Satisfaction: The Role of School Goal Structure and Value Consonance.” Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 24 (4): 369–385. doi:10.1080/10615806.2010.544300.

- Skiba, R J. 2000. ”Zero Tolerance, Zero Evidence: An Analysis of School Disciplinary Practice.“ Policy Research Report.

- Skiba, RJ., et al. 2000. “The Color of Discipline: Sources of Racial and Gender Disproportionality in School Punishment.” Policy Research Report.

- Solomon, D., M. Watson, V. Battistich, E. Schaps, and K. Delucchi. 1996. “Creating Classrooms that Students Experience as Communities.” American Journal of Community Psychology. 24 (6): 719–748. doi:10.1007/BF02511032.

- Stevahn, L., D.W. Johnson, R.T. Johnson, and D. Real. 1996. ““The Impact of a Cooperative or Individualistic Context on the Effectiveness of Conflict Resolution Training.” “American Educational Research Journal. 33 (4): 801–823. doi:10.3102/00028312033004801.

- Stevahn, L., D.W. Johnson, R.T. Johnson, K. Green, and A.M. Laginski. 1997. “Effects on High School Students of Conflict Resolution Training Integrated into English Literature.” The Journal of Social Psychology. 137 (3): 302–315. doi:10.1080/00224549709595442.

- Stevahn, L. 2004. “Integrating Conflict Resolution Training into the Curriculum.” Theory into Practice. 43 (1): 50–58. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4301_7.

- Stevahn, L., L. Munger, and K. Kealey. 2005. “Conflict Resolution in a French Immersion Elementary School.” The Journal of Educational Research. 99 (1): 3–18. doi:10.3200/joer.99.1.3-18.

- Sun, R.C., and D.T. Shek. 2012. “Classroom Misbehavior in the Eyes of Students: A Qualitative Study.” The Scientific World Journal. 2012. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.11.005.

- Tjosvold, D., and S.S. Fang. 2004. “Cooperative Conflict Management as a Basis for Training Students in China.” Theory Into Practice. 43 (1): 80–86. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4301_10.

- Vaandering, D. 2011. “A Faithful Compass: Rethinking the Term Restorative Justice to Find Clarity.” Contemporary Justice Review. 14 (3): 307–328. doi:10.1080/10282580.2011.589668.

- Van den Bogert, N., J. van Bruggen, D. Kostons, and W. Jochems. 2014. “First Steps into Understanding Teachers’ Visual Perception of Classroom Events.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 37: 208–216. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.09.001.

- Van Tartwijk, J., P. den Brok, I. Veldman, and T. Wubbels. 2009. “Teachers’ Practical Knowledge about Classroom Management in Multicultural Classrooms.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 25 (3): 453–460. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.005.

- Vestal, A., and N.A. Jones. 2004. “Peace Building and Conflict Resolution in Preschool Children.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 19 (2): 131–142. doi:10.1080/02568540409595060.

- Waltman, Van Eck, van Eck, N J. Noyons, and Ed C.M. Noyons. 2010. “A Unified Approach to Mapping and Clustering of Bibliometric Networks.” Journal of Informetrics. 4 (4): 629–635. doi:10.1016/j.joi.2010.07.002.

- Wang, L.J., W.C. Wang, H.G. Gu, P.D. Zhan, X.X. Yang, and J. Barnard. 2014. “Relationships among Teacher Support, Peer Conflict Resolution, and School Emotional Experiences in Adolescents from Shanghai.” Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal. 42 (1): 99–113. doi:10.2224/sbp.2014.42.1.99.

- Weber, K.E., B. Gold, C.N. Prilop, and M. Kleinknecht. 2018. “Promoting pre-service Teachers’ Professional Vision of Classroom Management during Practical School Training: Effects of a Structured online-and video-based self-reflection and Feedback Intervention.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 76: 39–49. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.008.

- Webster‐Stratton, C., M. Jamila Reid, and M. Stoolmiller. 2008. “Preventing Conduct Problems and Improving School Readiness: Evaluation of the Incredible Years Teacher and Child Training Programs in High‐risk Schools.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 49 (5): 471–488. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01861.x.

- Weinstein, C., M. Curran, and S. Tomlinson-Clarke. 2003. “Culturally Responsive Classroom Management: Awareness into Action.” Theory into Practice. 42 (4): 269–276. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4204_2.

- Wilks, R. 1996. “Classroom Management in Primary Schools: A Review of the Literature.” Behaviour Change 13 (1): 20–32. doi:10.1017/S0813483900003922.

- Wintersteiner, W. 2013. “Building a Global Community for a Culture of Peace: The Hague Appeal for Peace Global Campaign for Peace Education (1999–2006).” Journal of Peace Education. 10 (2): 138–156. doi:10.1080/17400201.2013.790250.

- Zelizer, C. 2015. “The Role of Conflict Resolution Graduate Education in Training the Next Generation of Practitioners and Scholars.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology. 21 (4): 589. doi:10.1037/pac0000135.

- Zembylas, M., P. Charalambous, and C. Charalambous. 2012. “Manifestations of Greek-Cypriot Teachers’ Discomfort toward a Peace Education Initiative: Engaging with Discomfort Pedagogically.” Teaching and Teacher Education. 28 (8): 1071–1082. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.06.001.

Appendix 1

The Lexical Query

(TITLE(‘dispute’ OR ‘classroom management’ OR ‘class room management’ OR ‘conflict management’ OR ‘conflict resolution’ OR ‘conflict transformation’ OR ‘nonviolen* communication’ OR ‘peace education’ OR ‘peer mediation’ OR ‘restorative justice’ OR ‘restorative practice’ OR ‘school mediation’ OR ‘student* mediation’ OR ‘value* based education’ OR ‘value* education’) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY((*school* AND teacher*) OR (education* AND teacher*) OR (*school* AND student*) OR (education* AND student*) OR (*school* AND educator*) OR (education* AND educator*) OR (*school* AND pupil*) OR (education* AND pupil*) OR (classroom* AND student*) OR (classroom* AND pupil*) OR (classroom* AND teacher*) OR (classroom* AND educator*) OR (‘class room*’ AND student*) OR (‘class room*’ AND pupil*) OR (‘class room*’ AND teacher*) OR (‘class room*’ AND educator*) OR (student* AND teacher*) OR (pupil* AND teacher*) OR (student* AND educator*) OR (pupil* AND educator*) OR (*school* AND learner*) OR (education* AND learner*) OR (classroom* AND learner*) OR (‘class‐room*’ AND learner*) OR (teacher* AND learner*) OR (educator* AND learner*)) AND (LANGUAGE(english) AND (PUBYEAR > 1995 AND PUBYEAR < 2020) AND DOCTYPE(ar OR cp OR le OR no OR re))) OR (TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘dispute’ OR ‘classroom management’ OR ‘class room management’ OR ‘conflict management’ OR ‘conflict resolution’ OR ‘conflict transformation’ OR ‘nonviolen* communication’ OR ‘peace education’ OR ‘peer mediation’ OR ‘restorative justice’ OR ‘restorative practice’ OR ‘school mediation’ OR ‘student* mediation’ OR ‘value* based education’ OR ‘value* education’) AND TITLE((*school* AND teacher*) OR (education* AND teacher*) OR (*school* AND student*) OR (education* AND student*) OR (*school* AND educator*) OR (education* AND educator*) OR (*school* AND pupil*) OR (education* AND pupil*) OR (classroom* AND student*) OR (classroom* AND pupil*) OR (classroom* AND teacher*) OR (classroom* AND educator*) OR (‘class room*’ AND student*) OR (‘class room*’ AND pupil*) OR (‘class room*’ AND teacher*) OR (‘classroom*’ AND educator*) OR (student* AND teacher*) OR (pupil* AND teacher*) OR (student* AND educator*) OR (pupil* AND educator*) OR (*school* AND learner*) OR (education* AND learner*) OR (classroom* AND learner*) OR (‘class‐room*’ AND learner*) OR (teacher* AND learner*) OR (educator* AND learner*)) AND (LANGUAGE(english) AND (PUBYEAR > 1995 AND PUBYEAR < 2020) AND DOCTYPE(ar OR cp OR le OR no OR re)))

Appendix 2

Context matters – Examples from two countries

Specific contextual challenges in the USA