ABSTRACT

A pervasive feature of populism is the use of rescue narratives to stimulate emotional adherence with audience predicated on evoking fear versus hope for salvation. This paper argues that restricting the rhetorical appeal of rescue narratives to the affective domain obscures the argumentative function that these narratives partake in constructing political arguments. It, thus, claims that rescue narratives can perform as arguments when used to provide reasons to justify political action. The paper examines the way(s) Donald Trump employs rescue narratives as arguments to justify military interventions in Iraq and Syria. The analytical framework supplements the argumentative strategies of the Discourse-Historical Approach to Critical Discourse Studies with pragma-dialectics’ argumentation schemes. The analysis shows that the different elements of the narrative construct premises for argument schemes adduced to justify the rightness of claims. Conceptualizing Trump’s rescue narratives as arguments prompts a reflection on the possibility of narrative discourse to be associated with the domain of reason.

Introduction

In the bourgeoning wave of literature on populism, there seems to be consensus that populists are essentially anti-elitists and anti-pluralists, construing themselves as outsiders to the establishment and the most capable of solving the problems of the ‘pure people’ (Mudde & Kaltwasser, Citation2017; Weyland, Citation2001; Wodak, Citation2015, Citation2020). One example of the appeal of such rhetoric is Donald Trump’s success in mobilizing significant portions of the electoral base in 2016 presidential elections. Trump’s strategy of interpreting and framing political and social realities in terms of crises aims to instill ‘ontological insecurity among the American public and serve to transform their anxiety into confidence’ that his ‘policy agendas are the route back to “normality”’ (Homolar & Scholz, Citation2019, p. 344). Indeed, Trump’s crisis rhetoric has tapped into the broad sense of the threatened identity among white-working class voters while his mission of saving ‘the people’ encompassed the promise to ‘Make America Great Again’ (Rowland, Citation2019). By embodying the image of saviors, populist leaders seek to create an intense emotional connection with their supporters predicated on invoking moral anger and fear vis-à-vis promising them redemption under their guidance (Gounari, Citation2018; Kissas, Citation2020; Schneiker, Citation2020). This emotionally charged narrative is inherently associated with the affective domain or pathos (Clément et al., Citation2017; Homolar, Citation2021; Jasper et al., Citation2018; Rowland, Citation2019).

In this paper, however, I argue that restricting the rhetorical appeal of rescue narratives to pathos has the tendency to obscure the argumentative function that these narratives tend to serve. Ellis (Citation2014) and Kvernbekk and Bøe-Hansen (Citation2017) have convincingly argued that war narratives are often used to appeal to reason by offering evidence to justify decisions for military involvement. In fact, forceful intervention, Campbell and Jamieson observe ‘is justified through a chronicle or narrative from which argumentative claims are drawn’ (Citation1990, p. 105). Based on these views, I claim that rescue narratives can fulfill an argumentative function if they are used to provide reasons to justify or legitimize political behavior. That is, if (rescue) narratives are used to serve the pragmatic function of convincing or persuading audience of claims of truth or normative rightness, then we have to acknowledge them as arguments. As such, the persuasive appeal of rescue narratives can also be linked to the domain of reason or logos. The proposition that rescue narratives can serve as arguments is premised on the following assumptions.

First, this paper perceives political discourse as primarily argumentative in nature (Fairclough & Fairclough, Citation2012), and in some contexts, it includes texts that offer retrospective argumentation aimed at justifying past actions or decisions. Narrativised accounts embedded in these texts are most likely employed to serve the discursive event’s main function –i.e. defending or justifying past political behavior. Therefore, restricting the conceptualization of these narratives to recounts of past events with the aim, for example, to inform or construct self/ group identity obscures the pragmatic function of convincing or persuading audience of the rightness of claims (i.e. argumentative function). To give one example, Trump’s rescue narratives consist of sequences of events showing logical connections between causes and/ or failed past actions taken against villains and their consequences. These cause–consequence relations have the basic function of justifying Trump’s use of force; thus, they are more connected to argumentation (as causal argumentation schemes) rather than mere recounts of past events (see below).Footnote1

Second, text linguists perceive argumentation and narration as two distinct generic patterns with formal features and communicative functions characteristic to each. Argumentation is the act of challenging or justifying claims of truth and normative rightness with the aim to convince or persuade while narration is the process of recounting past events experienced by a protagonist with the aim to inform, represent or construct identities, among other functions (Reisigl, Citation2020) (see below). However, discourse-focused analyses show a complex interplay between narration and argumentation. Yet, few studies address the intersection of argumentation and narration or how the latter serves to achieve the former rhetorical aims; i.e. how narratives construct political arguments that aim to persuade or convince (see Forchtner, Citation2014, Citation2020; Reisigl, Citation2020; Richardson, Citation2018; van Dijk, Citation1993). In this paper, I introduce the notion narrative argument, a well-established area of research in argumentation theory, to account for the way(s) rescue narratives perform as arguments. Narrative-based argument schemes denote the possibility of the narrative structure to conform to formal argumentation schemes such as argument from analogy, argument from example, pragmatic argument, etc. (Bex & Bench-Capon, Citation2017; Govier & Ayers, Citation2012; Hoven, Citation2017; Olmos, Citation2015; Walton, Citation2012). Adopting the notion narrative argument permits mapping the different elements of (rescue) narrative onto the premises of formal argumentation schemes and facilities examining the way these arguments are linked to the main claim that the narrative is supposed to justify.

In this paper, I seek to illustrate the way(s) the different elements of Trump’s rescue narratives, embedded in his national security rhetoric, provide premises for formal argumentation schemes adduced in support of military involvement in Iraq and Syria. The analysis is guided by the following questions:

What type of argumentation schemes do the different elements of the rescue narrative construct?

How do these arguments collectively serve to defend/ justify the rightness of claims?

Rescue narratives: emotional and argumentative dimensions

Narratives are cognitive tools via which ‘we come to know, understand and make sense of the social word’ (Somers, Citation1994, p. 606). The configuration of a narrative requires selecting plot, organizing events, in terms of temporality and causal connections, and ascribing roles to characters. The arrangement of these elements into an ‘intelligible whole’ with a beginning (identifies the source of disruption or problem), middle (proposes a solution) and an end (declares the outcome) conveys a sense of coherence on the unfolding events (Ricoeur, Citation1991, p. 21). During political strife and international conflicts, war narrative represents an ideological vision of why a nation should enter war; thereby, it communicates the reasons that justify such a decision to the public (De Graaf et al., Citation2015). Research on national security discourses legitimizing the use of force has shown that romantic narrative – featuring a hero/ine struggling against a villain that harms innocent civilians – is one of the favored modes of storytelling, as it mobilizes audience around a moral cause (Clément et al., Citation2017; Jasper et al., Citation2018; Ringmar, Citation2006). Lakoff (Citation1991) further asserts that the ‘just war’ is presented in the form of a fairy tale that features a battle between good and evil where the hero/ine’s quest is to annihilate evil for good to prevail.

Rescue narrative is an instantiation of the archetypal romantic narrative that features the triad villain–victim–hero. Rescue narratives, according to Lakoff (Citation2009), have specific semantic roles and structured actions: the Villain/enemy harms the Victim, the Hero/savior struggles against the Villain, and the Helpers together with the Hero defeat the Villain. Through rescue narratives, populists create the presumption that the world is divided into two antithetical and opposing sides. In domestic politics, the good, innocent, powerless and unfairly treated ‘we’/‘the people’ are/is identified as the victim whereas the bad, corrupt, powerful and unjustly privileged ‘them’/elites and/or immigrants – depending on the context – constitute the villain category. Incipient scholarship on populism has underscored the volatility of populist messages when accommodating to different social contexts in pursuit of political gains (Krzyżanowski, Citation2020). This has resulted in discursive shifts that usually operate within borderline discourses, which make it possible to pronounce inflammatory and offensive statements against ‘the other’ through a seemingly civil prose (Krzyżanowski & Ledin, Citation2017). Accordingly, it is noteworthy to see the discursive changes in framing villains through Trump’s security narratives.

Effective rescue narratives have to activate simultaneously feelings of ‘compassion – through the identification of a suffering, innocent victim – and moral anger – through the identification of an illegitimate aggressor’ (Clément et al., Citation2017, p. 994). The resonance of rescue narratives relates to mobilizing a set of shared collective emotions stimulated by the sequences of events that detail the transition from a state of disrupted equilibrium to a final state where equilibrium is restored via hero’s actions (Clément et al., Citation2017; Hoven, Citation2017). As such, the plot of rescue narratives ‘oscillates between tragedy and triumph. This “seductive” rhythm, which works to amplify emotive identification’ with the hero also ‘serves to keep the audience hooked by leaving it in suspense over the victory’ (Homolar, Citation2021, p. 9). It is clear, then, that rescue narratives are inherently linked to the emotional domain. However, as mentioned above, rescue narratives embedded in Trump’s national security discourses are employed to offer reasons and evidence to justify the use of force; i.e. are used as arguments.

In fact, McGee and Nelson contend reducing narrative to sequences of events told from a particular point of view; thus, they propose a functional approach where narrative is conceived of as a ‘moment of argument intrinsic to reason and practiced especially, but not exclusively, in politics’ (Citation1985, p. 140). Fisher further asserts that narrative discourse ‘contains structures of reason that can be identified as specific forms of argument and assessed as such’ (Citation1987, p. 139). Based on this view, argumentation scholars have proposed the term narrative argument to account for the way(s) narratives exhibit argumentative qualities (Kvernbekk, Citation2003; Kvernbekk & Bøe-Hansen, Citation2017; Olmos, Citation2014). Narrative-based argument schemes refer to the way the different elements of the narrative structure are mapped onto the premises of formal argumentation schemes such as argument from analogy, argument from example, pragmatic argument, etc. (see, Bex & Bench-Capon, Citation2017; Govier & Ayers, Citation2012; Hoven, Citation2017; Walton, Citation2012). For example, in narratives where actions are negatively or positively evaluated based on anticipated consequences, the narrative is considered an argument in as much as it exhibits similarity relations with the pragmatic argument scheme (Hoven, Citation2017). In Bex and Bench-Capon’s (Citation2017) work, the content of moral stories, such as parables and fables, are mapped onto the premises of the argument from analogy to defend action. Another example is the Norwegian government’s use of the war narrative on Afghanistan to reinforce the conclusion that Norway’s participation in war is legitimate and right (Kvernbekk & Bøe-Hansen, Citation2017).

By adopting the notion narrative argument, I attempt to show the way(s) the different elements of Trump’s rescue narratives configure in premises for formal argumentation schemes, and therefore, they are perceived as arguments.

Conceptualizing rescue narratives as arguments

As mentioned above, rescue narratives frame crises in terms of clear cut-boundaries between what constitutes ‘good’ versus ‘evil’. The discursive construction of such Manichean opposition is one of the main aims of the DHA. In the DHA, the macro-strategy of positive Self-presentation and negative Other-presentation is realized through strategies of nomination (e.g. personal deixis, metonymies, synecdoche, etc.), predication (e.g. stereotypes and evaluative adjectives, etc.), argumentation (a fund of topoi/ argument schemes and fallacies), perspectivization (e.g. narrating, reporting, etc.) and mitigation/intensification (e.g. hyperbole, euphemisms, vague expressions, etc.) (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2009, p. 94). In the DHA, the analysis of argumentation focuses on identifying topoi defined as ‘formal or content-related warrants or “conclusion rules” which connect the argument with the conclusion, the claim’ (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2009, p. 110). This conceptualization of topoi as both formal and content-related warrants has been subject to criticism, primarily for not conforming to the Aristotelian tradition (see Boukala, Citation2016; Fairclough & Fairclough, Citation2012; Žagar, Citation2009). As I mentioned earlier, the aim of this paper is to examine the way(s) elements of rescue narrative construct premises for formal argumentation schemes; therefore, I draw on one of the main reference frameworks for normative critique of argumentation in the DHA, namely, pragma-dialectics.

In pragma-dialectics, argumentation schemes belong to one of three generic forms. First, symptomatic argumentation is based on a relation of concomitance, association or connection in which the argument presents a sign, characteristic or is symptomatic of what is mentioned in the standpoint (e.g. argument from authority). Second, comparison argumentation is based on a relation of similarity that links the premises of the argument to the standpoint (e.g. argument from analogy). Finally, causal argumentation refers to a relation of causality between the argument and the standpoint by referring to the consequences or outcomes (e.g. argument from negative consequences) (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014, pp. 547–548). In pragma-dialectics, argumentation is a means of ‘convincing a reasonable critic of the acceptability of a standpoint by putting forward a constellation of propositions for justifying or refuting the proposition expressed in the standpoint’ (van Eemeren & Grootendorst, Citation2004, p. 1). This exchange of propositions aims to resolve a difference of opinion on the merits where arguers are expected to commit to standards of reasonableness stipulated by the ideal model of critical discussion.

In actual argumentative practice, arguers’ pursuit to have their claims accepted may override their observance of the 10 rules of critical discussion, which signals that the respective move is fallacious.Footnote2 Any discussion move that violates a rule for critical discussion is fallacious, as it obstructs the resolution of disagreement on the merits (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014). A fallacious move also indicates that the arguer has made an expedient choice from the set of possibilities available to her at a certain point in the exchange to steer the discussion rhetorically to her advantage; i.e. the rhetorical effectiveness of the move.Footnote3 Normative evaluation of argumentative discourse is a critical endeavor and clearly pertains to the critical analysis of political discourse that aims to demystify the ideological underpinnings of discourses that have been naturalized (Reisigl & Wodak, Citation2001). Indeed, critical studies of ethnic, racist, sexist, etc., discourses have shown the fallaciousness of the arguments deployed in the justification of preferential treatment of minorities, yet their effectiveness in appealing to and persuading audience suggest that they can be strategically exploited to achieve political aims.

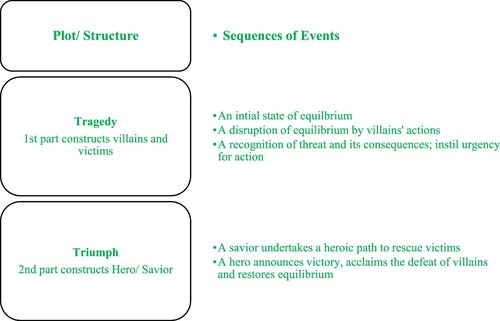

Meanwhile, narration is ‘a representation of a possible world (–) at the center of which there are one or more protagonists (–) who are existentially anchored in a temporal or spatial sense and who (mostly) perform goal directed actions’ (Fludernik, Citation2009, p. 6). Herman (Citation2009) maintains that situatedness of the narrated events, events sequencing, the experience of living through the created story world, and world-disruption are the defining criteria of narrative texts. From a structural perspective to narrative analysis, narrative structure consists of five stages or sequences of events (Georgakopoulou & Goutsos, Citation1997). The story starts with a state of equilibrium, then a disruption is caused by some agents or actions, afterwards a recognition to this disruption leads to assigning a protagonist the task to respond to the disruption, and finally, the story ends with reinstating equilibrium (Kafalenos, Citation2006; Lacey, Citation2000). As previously mentioned, the plot of ‘hero-villain narratives – the sequence of causally related events from the story’s beginning to its resolution – oscillates between tragedy and triumph’ (Homolar, Citation2021, p. 9). By integrating the above-mentioned views, the structure of rescue narrative is formulated as presented in .

The proposed narrative structure in acts as a template where the content of Trump’s narratives is divided into sequences of events. Each sequence is then mapped onto the respective argument schemes. It is worth mentioning that narratives do not always follow the exact order of events presented in . Hoven (Citation2017) emphasizes that storytellers can start the narrative at any stage and reorder its elements. In fact, as the analysis below shows, Trump opens his three speeches by celebrating his success in carrying out the mission of defeating villains, and then reasons backwards to provide evidence to justify the rightness of his actions. Consequently, Trump’s rescue narratives cannot only be seen as narratives. These narratives have to be acknowledged as arguments; otherwise, we neglect their pragmatic function of convincing or persuading audience that the use of force was right. As mentioned earlier, the aim of the study is to show the ways in which (rescue) narratives perform as arguments. Thus, the analysis focuses on the way the narrative structure, and more specifically, the way the sequences of events presented in construct premises for formal argumentation schemes.

Trump speeches and context

The data for this study comprises three speeches given by Trump regarding military actions carried out in Iraq and Syria between 2018 and 2020. These speeches were retrieved from the Archived Trump White House website (https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/). In each speech, Trump attempts to defend and justify an already taken military action that has spurred controversy. Trump’s rhetorical aim is, therefore, not to deliberate over possible courses of action or policy choices. Rather, his aim is to defend already taken military actions by orientating to topics related to justice and to what is morally right.

Speech 1 which was delivered on 14 April 2018 discusses the military attack against the Syrian regime in retaliation to the use of chemical weapons in a rebel-held town outside Damascus. The retaliatory strike on Syria’s chemical weapons capabilities was a joint operation with France and Britain. In this speech, Trump explicitly mentions that he is addressing the American people to tell them ‘why we have taken this action’; thus, Trump attempts to defend the retaliatory strike by providing evidence in support of the claim that the military attack on Syria’s chemical capabilities is right. Speech 2 which was given on 27 October 2019 concerns the death of ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, after a US raid in Syria. In this speech, Trump employs a rescue narrative to justify the standpoint that attacking the leader of the ‘most ruthless and violent terror organization anywhere in the world’ is right. Speech 3 which was relayed on 3 January 2020 focuses on the killing of Qasem Soleimani by a US raid on Baghdad International Airport. Soleimani led the Quds Force, one of the branches of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, which is designated by the US as a foreign terrorist organization. Therefore, the rescue narrative employed in this speech attempts to prove that the military attack on the second most important general in Iran is right.

The argumentative function of Trump’s rescue narratives

Tragedy: first part of the rescue narrative structure

The first part of the narrative structure encompasses three sequences of events that have a dual function (see ). These events construct the first two elements of the triad villain–victim–hero and provide the first set of reasons that prompted the use of force. As mentioned above, Trump opens his three speeches with statements that specify the nature of the armed attacks, introduce the audience to the targeted entity or enemy, and revere his leadership skills. As such, Trump starts his speeches announcing the defeat of villains, and then he proceeds to justify the rightness of the military attacks.

Text 1: I ordered the United States Armed Forces to launch precision strikes on targets associated with the chemical weapons capabilities of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad.

Text 2: Last night, the United States brought the world’s number-one terrorist leader to justice. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is dead. He was the founder and leader of ISIS, the most ruthless and violent terror organization anywhere in the world.

Text 3: Last night, at my direction, the United States military successfully executed a flawless precision strike that killed the number-one terrorist anywhere in the world, Qasem Soleimani.

Tragedy: disruption of equilibrium and recognition of threat sequences

In these two sequences (see ), narrators assign a blameworthy entity responsible for the disruption of order, specify the nature of villains’ actions, elaborate on the magnitude of the damage caused, identify victims and magnify the intensity of their suffering. The goal is to make audience feel fear at the threat. Moreover, this part of the narrative structure presents evidence that not only feeds into justifying the negative attributions of villains, but also offer reasons to induce action.

In Text 1, Bashar al-Assad (the Syrian president) is presented as the evil ‘Other’ whereas Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi (ISIS leader) and Qasem Soleimani (leader of Iranian-backed Quds Force) are depicted as culprits in Text 2 and 3, respectively. The construction of enemies is achieved via the use of value-laden words (Assad: dictator and criminal; Baghdadi: terrorist leader, thug and depraved man; Soleimani: terrorist), dehumanizing metaphors (Assad: monster; Baghdadi and ISIS members: savage monsters) and violent imagery (e.g. terrorist warlords who plunder their nation to finance bloodshed abroad, anguish that can be unleashed, etc.). Moreover, the use of negatively charged terms and hyperbolic expressions, such as massacre, barbarism, genocidal mass murder, hardcore killers, beheadings, number-one terrorist anywhere in the world, etc. hints at the moral attributes of perpetrators that run contrary to widely accepted social norms and values (see below).

The opening statements also communicate the first standpoint that underscores the negative characterization of villains. To support each standpoint, Trump provides evidence in the form of argument from example –a subtype of symptomatic argumentation. In Text 1, Trump reminds the audience that Assad launched a ‘savage chemical weapons attack against his own innocent people’ almost a year ago. He also refers to the US-Russian agreement in 2013, during Obama’s administration, which stipulated the removal of Syria’s chemical weapons arsenal.Footnote4 Reference to this agreement alludes to several instances of large-scale use of nerve gas by the Syrian regime in its crackdown on the 2011 revolution. The third example is Assad’s latest chemical weapons attack, which ‘left mothers and fathers, infants and children, thrashing in pain and gasping for air’. These illustrative examples are cited as evidence to support the claim that Assad is a dictator and monster.

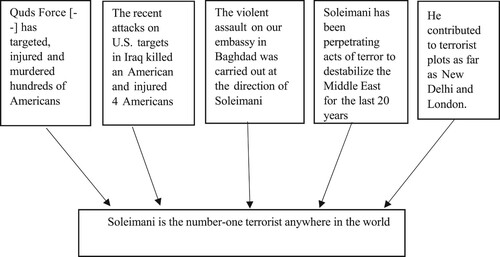

Similarly, in Text 2 and 3, Trump enumerates examples of al-Baghdadi and Soleimani’s actions to justify the depiction of each one of them as the world’s number-one terrorist. In Text 2, Trump refers to American victims, the ‘execution of Christians’, the ‘genocidal mass murder of Yazidis’, the ‘orange suits prior to so many beheadings’ and the ‘publicized murder of the Jordanian pilot’ as evidence of al-Baghdadi’s actions that would qualify him to be the world’s number-one terrorist. In Text 3, Trump supports the standpoint that villainizes Soleimani by narrating facts, which configure as premises for the argument from example. A reconstruction of the argument from example for Text 3 is presented in .

Here, I should also note that communicating the premises of arguments from example, especially in Texts 1 and 2, using sympathy-laden language and violent imagery in describing victims and their suffering (e.g. burnt alive in a cage, thrashing in pain, gasping for air, ghastly specter, etc.) intend to evoke the audience’s compassion and fear. As for the former, a pathetic appeal is fallacious (i.e. an ad misericordiam) if it attempts to sway the audience by appealing to emotions at the expense of using relevant argumentation, which represents a violation of Rule 4 of critical discussion (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014). However, Walton (Citation1997) and Kienpointner (Citation2009) have convincingly argued that appeals to pity and compassion are not inherently fallacious, and that in certain contexts they can be legitimate arguments. To test the plausibility of an ad misericordiam, Walton (Citation1997, p. 155) proposes a set of critical questions aimed at assessing whether: (1) victims are really in need of help; (2) the action can be brought about; (3) the action really helps or relieves the distress; and finally, if the action results in negative side effects. Interestingly, the three military actions that Trump is defending have significantly minimized the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime, reduced the killing of civilians after al-Baghdadi’s death, and decreased the targeting of American civilians after attacking Soleimani. Moreover, the negative side effects that would undermine these military actions, and thus, rebut Trump’s claims have not yet materialized. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that emotional appeals to pity, in counterterrorism and violations of human rights’ contexts, seem to be legitimate arguments that support Trump’s villainization of perpetrators.

Text 1: I also have a message tonight for the two governments (Iran and Russia) most responsible for supporting, equipping and financing the criminal Assad regime.

So today, the nations of Britain, France and the United States of America have marshaled their righteous power against barbarism and brutality.

Text 2: Their (ISIS) murder of innocent Americans – James Foley, Steven Sotloff, Peter Kassig, and Kayla Mueller – were especially heinous.

Text 3: Soleimani was plotting imminent and sinister attacks on American diplomats and military personnel, but we caught him in the act and terminated him.

Premise 1: If we did not kill al-Baghdadi, then American civilians will be targeted

Premise 2: Attacking American civilians is bad

Premise 3: Therefore, al-Baghdadi ought to be prevented from targeting Americans

Premise 4: But the only way to prevent this is by killing al-Baghdadi

Conclusion: Therefore, we had to kill al-Baghdadi

Fear from imminent threat is further augmented via flashbacks to series of wrongdoings and to failed attempts that contribute to ‘an arc-of-suspense whose apogee is reached in the present-day’, and as such, it further legitimizes Trump’s use of force (Clément et al., Citation2017, p. 1002). In other words, past responses did not deter villains, as evidenced by their latest actions; thus, an action of some sort should be taken to eliminate the possibility of harm. Trump narrates this sequence of events in the form of cause–effect relations that suggest ‘a minimum of disputable connections’ (van Eemeren & Houtlosser, Citation1999, p. 491).

Text 1: One year ago, Assad launched a savage chemical weapons attack against his own innocent people. The United States responded with 58 missile strikes that destroyed 20 percent of the Syrian Air Force.

In 2013, President Putin and his government promised the world that they would guarantee the elimination of Syria’s chemical weapons. Assad’s recent attack – and today’s response – are the direct result of Russia’s failure to keep that promise.

The first cause–effect relation explicitly contradicts this implication, as it suggests that previous military attacks had also failed. This contradiction amounts to the fallacy of denying an unexpressed premise by failing to commit to elements that are implied earlier on in the defense, which represents a violation of Rule 5 of critical discussion (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014). That is, if previous strikes did not deter Assad from using chemical weapons, why Trump ordered the retaliatory strike. In fact, Trump might have anticipated that sections of the audience and/ or opponents to exercise vigilance; and a result, they might challenge the decision for the retaliatory strike. Therefore, he justifies the retaliatory strike by claiming that Assad’s latest chemical attack represents ‘a significant escalation in a pattern of chemical weapons use’. In this sense, Trump is not only stating the reason that prompted the retributive strike, but he also attempts to silence opponents who might argue for the use of non-coercive means.

Triumph: second part of the rescue narrative structure

This section of the plot consists of two sequences of events that narrate the different steps of the route to victory (see ) and capitalize on the positive consequences exemplified in the defeat of villains and restoration of order. It sketches out a model of a virtuous, moral and benevolent leader/ hero who appeals to core American values that are presented as timeless and shared by western citizens as well. The objective is to invoke morality as a motive or reason for action.

Text 2: Baghdadi has been on the run for many years, long before I took office. But at my direction, as Commander-in-Chief of the United States, we obliterated his caliphate, 100 percent, in March of this year.

Triumph: heroic path to victory and restoration of order sequences

In these two sequences of events (see ), Trump casts himself as the ultimate authority and savior of the nation. These sequences also aim to confer different levels of normativity on the military actions taken against villains. Invoking morals, shared values, constitutional authority and international laws are types of evidence that aim to facilitate the endorsement of Trump’s valorous deeds. In the last sequence, Trump unequivocally states how the reinstatement of order is maintained.

In each speech, Trump asserts that the military actions were carried out based on his directions, thereby emphasizing the superiority of his position: ‘I ordered the United States Armed Forces to launch precision strikes’, ‘at my direction, the United States military successfully executed a flawless precision strike’. According to McDonough, Trump’s rhetoric is marked by the use of first-person language when describing how problems can be solved to present himself as the ‘sole salvation’ (Citation2018, p. 148). Moreover, Trump emphasizes that his directions are in conformity with his constitutional duties as a president. Here, Trump alludes to the US constitution that assigns the role of commander-in-chief to presidents who are entitled to authorize overseas military operations to safeguard the nation. On the one hand, the argument from authority invokes the constitutional powers vested in Trump to confer a level of normativity on the already taken military actions, and attempts to silence opponents, especially in Text 3, who questioned the legality of the unprecedented move by the US against Iran, on the other.

Text 1: The purpose of our actions tonight is to establish a strong deterrent against the production, spread and use of chemical weapons. Establishing this deterrent is a vital national security interest of the United States.

In Syria, the United States [–] is doing what is necessary to protect the American people.

Text 2: The United States has been searching for Baghdadi for many years. Capturing or killing Baghdadi has been the top national security priority of my administration.

Text 3: As President, my highest and most solemn duty is the defense of our nation and its citizen.

Text 1: Following the horrors of World War I a century ago, civilized nations joined together to ban chemical warfare.

So today, the nations of Britain, France and the United States of America have marshaled their righteous power against barbarism and brutality.

Text 2: Baghdadi was vicious and violent, and he died in a vicious and violent way, as a coward, running and crying.

The thug who tried so hard to intimidate others spent his last moments in utter fear, in total panic and dread, terrified of the American forces bearing down on him.

After invoking the image of the savior, Trump highlights the positive consequences of the already taken military actions, which further support the rightness of the military actions. In Text 3, one of the positive consequences of killing Soleimani is that the ‘imminent and sinister attacks’ can no longer be carried out because ‘we caught him in the act and terminated him’. Similarly, in Text 2, Trump emphasizes that by killing al-Baghdadi he ‘will never again harm another innocent man, woman, or child’. In Text 1, the retaliatory strike on Syrian regime aims ‘to establish a strong deterrent against the production, spread and use of chemical weapons’. However, the arguments from positive consequences are fallacious because the combination of an (implicit) descriptive standpoint (e.g. killing of Soleimani is right) and a normative argument (e.g. saving innocent lives is favorable/desirable) leads to an inappropriate use of causal argumentation; namely, an ad consequentiam, which violates Rule 7 of critical discussion (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014).

Text 1: In Syria, the United States [–] is doing what is necessary to protect the American people. Over the last year, nearly 100 percent of the territory once controlled by the so-called ISIS caliphate in Syria and Iraq has been liberated and eliminated.

Text 2: As you know, last month, we announced that we recently killed Hamza bin Laden, the very violent son of Osama bin Laden, who was saying very bad things about people, about our country, about the world. He was the heir apparent to al Qaeda.

Text 3: Under my leadership, we have destroyed the ISIS territorial caliphate, and recently, American Special Operations Forces killed the terrorist leader known as al-Baghdadi. The world is a safer place without these monsters.

Text 1: We are prepared to sustain this response until the Syrian regime stops its use of prohibited chemical agents.

Text 2: Today’s events are another reminder that we will continue to pursue the remaining ISIS terrorists to their brutal end. That also goes for other terrorist organizations. They are, likewise, in our sights.

Text 3: Under my leadership, America’s policy is unambiguous: To terrorists who harm or intend to harm any American, we will find you; we will eliminate you. We will always protect our diplomats, service members, all Americans, and our allies.

Conclusion

In this paper, I argued against restricting the rhetorical appeal of rescue narratives to the emotional domain and proposed that, in context of national security, these narratives pertain to logos in as much as the different elements of the narrative structure provide premises for formal argumentation schemes. Conceptualizing (rescue) narratives –and by extension narratives in general– only as recounts of past events experienced by agents obscures the pragmatic function of convincing or persuading audience of claims of truth and normative rightness. From an analytical perspective, this restricted view neglects elaborating on the argumentation advanced via narratives, and more importantly, from a critical perspective, ignores a normative evaluation of argumentation vis-à-vis counterarguments and rebuttals. The proposition to conceptualize narratives as argument takes the recognition that political discourse in fundamentally argumentative in nature as its starting point. Then, it weaves insights from critical discourse scholarship and argumentation theory. From the former, empirical analyses of discourse recognize the potential overlap between narration and argumentation, yet current analytical tools fall short of accounting for argumentatively oriented narratives. From the latter, I adopt the notion narrative argument, which accounts for the way(s) narratives exhibit argumentative qualities or perform as arguments. The analyses illustrated that narrative-based argument schemes made it possible to elaborate on the argumentation put forward through rescue narratives by mapping the different elements of the narrative structure onto premises for formal argument schemes. From a normative perspective, the analysis also involved assessing the fallaciousness of argumentative moves that failed to commit to standards of reasonableness but, indeed, served a rhetorical effect. Nonetheless, Trump’s speeches are attempts to justify and legitimize the rightness of using military force in overseas interventions by offering reasons that weigh in favor of the actions. This endeavor is necessarily an argumentative activity; hence, its association with the domain of logos. It follows that the resonance or rhetorical/ persuasive appeal of rescue narratives is not only linked to stimulating audiences’ emotions, but is also related to inducing changes in their cognitive environment.

Moreover, to analyze narratives as arguments, I proposed a structure for rescue narratives that consists of five sequences of events. Thus, Trump’s narratives were divided into sequences of events, and each sequence of events was then mapped onto the respective argument schemes. For example, the disruption of order and recognition of threat sequences of events configured in premises for arguments such as argument from example, argument from fear appeal and cause–effect arguments. Similarly, the hero’s path sequence and the reinstatement of order sequences of events featured in premises for different sub-types of causal argumentation, e.g. argument from the nobility of goal and ad consequentiam. These sequences of events also appeared in premises for argument from analogy and pragmatic argumentation. Finally, the mission of saving ‘the people’ highlighted the volatility of populist discourses and the ability of populist politicians to accommodate to different social contexts in pursuit of their political aims. Keeping in mind that the majority of research on ‘savior politicians’ relates to domestic politics; it was noteworthy to see the discursive shifts in framing villains, for example, Trump’s portrayal of the Syrian president as monster and criminal. These unmitigated and blatant statements are voiced within a moral and quasi-religious mission of saving ‘the people’. Finally, the merits of analyzing Trump’s rescue narratives as arguments prompt a reflection on the possibility of narrative discourse to be a mode for arguing for or against a claim.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rania Elnakkouzi

Rania Elnakkouzi is lecturer of English language in the department of English Literature and Linguistics at Qatar University. She received her PhD in Linguistics from Lancaster University. Her research interests include critical discourse studies, argumentation, rhetoric and cognitive pragmatics. Her recent publications include Strategic Maneouvering in Arab Spring Political Cartoons (Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

Notes

1 It is also possible that arguments are incorporated into narratives. However, the view taken here is that narratives are used as parts of arguments. That is, the narrative structure and the sequences of events related to each section of the plot (see ) construct premises for arguments.

2 The 10 rules for critical discussion are: Rule 1 (Freedom Rule), Rule 2 (Obligation to Defend Rule), Rule 3 (Standpoint Rule), Rule 4 (Relevance Rule), Rule 5 (Unexpressed Premise Rule), Rule 6 (Starting Point Rule), Rule 7 (Validity Rule), Rule 8 (Argument Scheme Rule), Rule 9 (Concluding Rule) and Rule 10 (Language Use Rule) (van Eemeren et al., Citation2014, pp. 542–544).

3 Pragma-dialecticians prefer the term effectiveness rather than persuasiveness because the later only pertains to the rhetorical effectiveness of argumentative moves advanced in the argumentation stage while the former encompasses the rhetorical effect of all the stages of critical discussion.

4 The UN Resolution 2118 ratified the US-Russian agreement in 2013, which prevented Assad from using sarin and other chemical agents to attack innocent civilians.

References

- Bex, F., & Bench-Capon, T. (2017). Arguing with stories. In P. Olmas (Ed.), Narration as argument (pp. 31–46). Springer.

- Boukala, S. (2016). Rethinking Topos in the discourse historical approach: Endoxon seeking and argumentation in Greek media discourse on ‘Islamist terrorism’. Discourse Studies, 8(3), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445616634550

- Campbell, K., & Jamieson, K. (1990). Presidents creating presidency: Deeds done in words. UCP.

- Clément, M., Lindemann, T., & Sangar, E. (2017). The ‘Hero-protector narrative’: Manufacturing emotional consent for the use of force. Political Psychology, 38(6), 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12385

- De Graaf, B., Dimitriu, G., & Ringsmose, J. (2015). Strategic narratives, public opinion, and war. Routledge.

- Ellis, D. (2014). Narrative as deliberative argument. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict, 7(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2014.915337

- Fairclough, I., & Fairclough, N. (2012). Political discourse analysis: A method for advanced students. Routledge.

- Fisher, W. (1987). Technical logic, rhetorical logic, and narrative rationality. Argumentation, 1(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00127116

- Fludernik, M. (2009). An introduction to narratology. Routledge.

- Forchtner, B. (2014). Historia Magistra Vitae: The Topos of history as a teacher in public struggles of self and other representation. In C. Hart & P. Cap (Eds.), Contemporary critical discourse studies (pp. 19–43). Bloomsbury.

- Forchtner, B. (2020). Critique, Habermas and narrative (genre): The discourse-historical approach in critical discourse studies. Critical Discourse Studies, 18(3), 314–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1803093

- Georgakopoulou, A., & Goutsos, D. (1997). Discourse analysis. An introduction. EUP.

- Gounari, P. (2018). Authoritarianism, discourse and social media: Trump as the ‘American Agitator’. In M. Jeremiah (Ed.), Critical theory and authoritarian populism (pp. 207–227). UWP.

- Govier, T., & Ayers, L. (2012). Logic, parables, and argument. Informal Logic, 32(2), 161–189. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v32i2.3457

- Herman, D. (2009). Basic elements of narrative. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Homolar, A. (2021). A call to arms: Hero-villain narratives in US security discourse. Security Dialogue, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/09670106211005897

- Homolar, A., & Scholz, R. (2019). The power of Trump-speak: Populist crisis narratives and ontological security. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(3), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1575796

- Hoven, P. (2017). Narratives and pragmatic arguments: Ivens’ The 400 million. In P. Olmas (Ed.), Narration as argument (pp. 103–122). Springer.

- Jakobsen, P., & Ringsmose, J. (2015). For our own security and for the sake of the Afghans: How the Danish public was persuaded to support an unprecedented costly military endeavour in Afghanistan. In D. G. Beatrice, G. Dimitriu, & J. Ringsmose (Eds.), Strategic narratives, public opinion, and War (pp. 138–156). Routledge.

- Jasper, J., Young, M., & Zuern, E. (2018). Character work in social movements. Theory and Society, 47(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-018-9310-1

- Jentleson, B., & Britton, R. (1998). Still pretty prudent. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(4), 395–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002798042004001

- Kafalenos, E. (2006). Narrative causalities. Ohio State University Press.

- Kienpointner, M. (2009). Plausible and fallacious strategies to silence one’s opponent. In F. van Eemeren (Ed.), Examining argumentation in context: Fifteen studies on strategic maneuvering (pp. 61–76). John Benjamins.

- Kissas, A. (2020). Performative and ideological populism: The case of charismatic leaders in Twitter. Discourse & Society, 31(3), 26–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926519889127

- Krzyżanowski, M. (2020). Discursive shifts and the normalisation of racism: Imaginaries of immigration, moral panics and the discourse of contemporary right-wing populism. Social Semiotics, 30(4), 503–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2020.1766199

- Krzyżanowski, M., & Ledin, P. (2017). Uncivility on the web populism in/and the borderline discourses of exclusion. Journal of Language and Politics, 16(4), 566–581. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.17028.krz

- Kvernbekk, T. (2003). On The argumentative quality of explanatory narrative. In F. van Eemeren, A. Blair, & C. Willard (Eds.), Anyone who has a view: Theoretical contributions to the study of argumentation (pp. 269–282). Springer.

- Kvernbekk, T., & Bøe-Hansen, O. (2017). How to win wars: The role of the war narrative. In P. Olmas (Ed.), Narration as argument (pp. 216–234). Springer.

- Lacey, N. (2000). Narrative and genre: Key concepts in media studies. Macmillan.

- Lakoff, G. (1991). Metaphor and war: The metaphor system used to justify war in the Gulf. The Canadian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, 23(2/3), 25–32. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23609916

- Lakoff, G. (2009). The political mind: A cognitive scientist’s guide to your brain and its politics. Penguin.

- McDonough, M. (2018). The evolution of demagogic rhetoric as interactive and ongoing. Communication Quarterly, 66(2), 138–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/014663373.2018.1438486

- McGee, M., & Nelson, J. (1985). Narrative reason in public argument. Journal of Communication, 35(4), 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1985.tb02978.x

- Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. OUP.

- Olmos, P. (2014). Classical fables as arguments: Narration and analogy. In H. Ribeiro (Ed.), Systematic approaches to argument by analogy (pp. 189–208). Springer.

- Olmos, P. (2015). Story credibility in narrative arguments. In F. van Eemeren & B. Garssen (Eds.), Reflections on theoretical issues in argumentation theory (pp. 155–167). Springer.

- Reisigl, M. (2020). “Narrative!” I can’t hear that anymore. A linguistic critique of an overstretched umbrella term in cultural and social science studies, discussed with the example of the discourse on climate change. Critical Discourse Studies, 18(3), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2020.1822897

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2001). Discourse and discrimination: Rhetorics of racism and antisemitism. Routledge.

- Reisigl, M., & Wodak, R. (2009). The discourse historical approach. In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 87–121). Sage.

- Richardson, J. E. (2018). Sharing values to safeguard the future: British Holocaust Memorial Day commemoration as epideictic rhetoric. Discourse & Communication, 12(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481317745743

- Ricoeur, P. (1991). Life in quest of narrative. In D. Wood (Ed.), On Paul Ricoeur: Narrative and interpretation (pp. 20–33). Routledge.

- Ringmar, E. (2006). Inter-textual relations: The quarrel over the Iraq war as a conflict between narrative types. Cooperation and Conflict: Journal of the Nordic International Studies Association, 41(4), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836706069611

- Rowland, R. (2019). The populist and nationalist roots of Trump’s rhetoric. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 22(3), 343–388. https://doi.org/10.14321/rhetpublaffa.22.3.0343

- Schauer, F. (1987). Precedent. Stanford Law Review, 39(3), 571–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/1228760

- Schneiker, A. (2020). Populist leadership: The superhero Donald Trump as savior in times of crisis. Political Studies, 68(4), 857–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720916604

- Somers, R. (1994). The narrative constitution of identity: A relational and network approach. Theory and Society, 23(5), 605–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992905

- van Dijk, T. (1993). Stories and racism. In D. Mumby (Ed.), Narrative and social control: Critical perspectives (pp. 121–142). Sage.

- van Eemeren, F., Garssen, B., & Erik, K. (2014). Handbook of argumentation theory. Springer.

- van Eemeren, F., & Grootendorst, R. (1992). Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: A pragma-dialectical perspective. Routledge.

- van Eemeren, F., & Grootendorst, R. (2004). A systematic theory of argumentation: The pragma-dialectical approach. CUP.

- van Eemeren, F., & Houtlosser, P. (1999). Strategic manoeuvring in argumentative discourse. Discourse Studies, 1(4), 479–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445699001004005

- Walton, D. (1997). Appeal to pity: Argumentum ad misericordiam. SUNYP.

- Walton, D. (2012). Story similarity in arguments from analogy. Informal Logic, 32(2), 190–221. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v32i2.3159

- Walton, D., Reed, C., & Macagno, F. (2008). Argumentation schemes. CUP.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. UCP.

- Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: Populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative Politics, 34(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/422412

- Wodak, R. (2015). The politics of fear: What right-wing populist discourses mean. Sage.

- Wodak, R. (2020). The trajectory of far-right populism: A discourse-analytical perspective. In B. Forchtner (Ed.), The far right and the environment: Politics, discourse and communication (pp. 29–42). Routledge.

- Žagar, I. (2009). Topoi in critical discourse analysis. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, 6(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10016-010-0002-1