ABSTRACT

In this essay I analyse Sergio Basso’s documentary Giallo a Milano (Made in Chinatown, 2009), which took part in a wide-ranging media debate following the April 2007 protest of the Chinese community in Via Paolo Sarpi in Milan. In particular, my focus is on the various intermedial strategies employed within it, which, on the one hand, offer an extremely multifaceted and aesthetically sophisticated counter-narrative of its subject and, on the other, allow to debunk many of the stereotypes circulating about the Chinese in dominant mass media and popular discourse, powerfully bringing to light a series of portraits of migrant and post-migrant subjectivities in contemporary Italy, in which the complex intertwining of their identities of ethnicity and race, gender, social class and sexual orientation are constructed and performed on the cinema screen.

Introduction

When compared with other migratory cultures in the country, Chinese immigration in Italy portrays some specific peculiarities. It is a rather balanced population in terms of gender distribution, but extremely diversified concerning social class composition: in fact, a small elite of former migrants with a high level of socio-economic integration has been joined by a now consolidated middle class of small entrepreneurs and traders, followed by a growing number of migrants from a low social class that left China escaping from poverty (Pedone Citation2018, 82–83). Moreover, this migratory model typically tends to be featured by a form of self-employment based on family reunification and the creation of small family businesses after an initial phase of transition and settlement of the first migrants. These are some of the characteristics that have made the Chinese migratory model particularly successful, guaranteeing this community a relatively high level of socio-economic success on one hand, but causing its scarce integration in the Italian socio-cultural fabric on the other, especially due to the language barriers and the perceived impenetrability of the Chinese communities (ibid., 82), which in Italy are largely located in the Chinatowns of major cities such as Milan, Prato, Rome and others.

It is probably the economic success of this migratory model, along with other social and cultural factors, that has caused the spread of a series of specific stereotypes in the Italian dominant mass media and popular discourse. The Chinese would eat domestic pets and serve their meat in their restaurants, refuse to learn the language and participate proactively in Italian society, never die, recycle the documents of their deceased relatives to facilitate the arrival of new migrants, be controlled by mafia organisations such as the notorious Chinese Triad and be otherwise involved in illegal activities that damage the local economy (ibid., 88). Similar stereotypes have also penetrated the recent Italian film production and critics have identified specific ‘frames’ in the cinematic representation of Chinese residents in Italy that focus specifically on the Chinese mafia, the unfair competition of their entrepreneurial activities or the role of intercultural educators played by the young generations born and raised in Italy (Zhang Citation2019a).Footnote2

The air of generalised incommunicability and mutual mistrust between Chinese and Italians burst dramatically into a protest of the Chinese community in Via Paolo Sarpi in Milan (April 12, 2007), which was the first case of an ethnically based protest in contemporary Italy: generally speaking it was triggered by the allegedly improper use of public spaces by Chinese merchants during their loading and unloading goods, but was interpreted by the latter as unquestionable evidence of the differential treatment and open racism towards them by the Italian authorities (Zhang Citation2019b).

Sergio Basso’s Citation2009 documentary Giallo a Milano, produced by La Sarraz Pictures and CSC Productions, takes its cue from this headline to investigate the causes of this conflict and to reposition the current state of existence of the Chinese living in Milan. Basso was a trained sinologist before becoming the author of documentaries and fiction films,Footnote3 and as such he takes a critical stance in the media debates that have developed since the protests in Milan’s Chinatown which, as Zhang has shown (Zhang Citation2017), were heavily influenced by an ‘ethnocultural approach’ involving processes of ‘ethnogenesis’ and ‘ethnocentrism’ (389) and often leading to overt misrepresentations of Chinese citizens living in Italy. His documentary, which subsumes within itself all the characteristics of the ‘new cinema of reality’ (Dottorini Citation2013),Footnote4 appears as an extremely complex object, rich in linguistic and stylistic hybridizations: in fact, it makes use of the most disparate modes of representation in order to complicate the public’s gaze on the migratory phenomenon and thus lay bare the ambiguity of the very notion of ‘Chinese community’ as presented by other Italian media.

The present essay has a double focus. On the one hand, I focus on the different intermedial strategies employed in the documentary. Whereas in the first section I highlight strategies of polysemy, self-reflexivity and irony used to stage the anti-Chinese stereotype, I then move on to examine some of the intermedial references that are used to debunk this stereotype, focusing on the use of animation to narrate reality, on the references to photography and theatrical performance as a means of renegotiating identity and the migratory experience, and finally on the use of archive footage and painting to create a complex temporality and express a hybrid concept of identity. The second focus is more specifically intersectional. Through my analysis, I intend to show that it is precisely through this tight network of intermedial relations that Basso succeeds in creating a complex, polyphonic and nuanced audio-visual product that is in open ‘resistance to other media-television realisms’ (Bertozzi Citation2012, 28), deconstructing the very notion of ‘community’ and offering a portrait of a complex and multiform variety of subjectivities whose constructions of race and ethnicity, gender, social class and sexual orientation emerge and are performed on the cinematic screen.

“Fifteen ingredients to make a thriller”: staging the stereotype through polysemy, self-reflexivity, and irony

The opening credits roll and a voice-over, transmitted by a loudspeaker, announces the beginning of a boxing match, while two boxers enter the arena filmed by the excited movements of the cameras and surrounded by the enthusiastic voices of the audience. Then a sign informs: ‘They say that to make a thriller you need 15 ingredients’, followed by the first of these ingredients, ‘1. Big trouble. Better off dead’. The bell gong starts the first round and an extradiegetic music with pressing jazzy sounds thickens the halo of mystery. The two boxers, one in a blue outfit (Italy) versus the other in red (China), begin to fight to the sound of punches, while in parallel montage some of the most violent moments of the protest of the Chinese residents of Via Sarpi are shown, transmitted from the stock footage of a TV news programme of the time, heavily manipulated.Footnote5 The camera shifts several times between the two scenes, before cutting, with an evocative aerial forward tracking in shot, on a busy Via Sarpi where people are strolling, each absorbed in their own occupations, while the voice-overs of two unseen women candidly spew out their prejudices about the Chinese (they never die, they always spit, the awful stench of garlic they carry with them).Footnote6 A new cut then shows a young Chinese gymnast looking straight into the camera, before a quick lateral tracking shot follows her as she performs her acrobatic jumps on the trampoline. Finally, the two boxers again, the blue man knocking the red man to the ground, the bell of the gong that decrees the end of the match and the camera that jumps back onto Via Sarpi and shows a lifeless body, covered by a white cloth and lying on the ground in front of a restaurant with a sign in Chinese characters. An overlay informs that it is 27 March 2009, allowing the spectators to trace that body back to its former owner, Zang Hidi, a young Chinese immigrant killed, it seems, for resentment of jealousy by one of his fellow citizens, in a case that has been widely reported in the national media.

This first scene perfectly shows some peculiar traits of Basso’s aesthetic and stylistic approach to his subject. First of all, the giallo in the title, which resorts to the polysemy of the term in Italian, can be interpreted in its meaning of a ‘thriller’ or ‘detective story’ investigating the reasons that led to the conflict between Chinese and Italians, but at the same time one cannot also think of its denigrating meaning – giallo as a synonym for a person with yellow skin, therefore Chinese.Footnote7 Secondly, the pronounced self-reflexivity that runs through the whole documentary, giving it new and more complex meanings. The film is indeed divided into 15 chapters representing the necessary ingredients to make a good thriller, and thus acquires an accentuated (self)reflective dimension, reflecting on itself and, in the words of Bill Nichols, ‘prod[ing] the viewer to a heightened form of consciousness about her relation to a documentary and what it represents’ (Nichols Citation2001, 128). Thus, from the ‘dead’ man of the first chapter to the ‘confession’ of the final chapter, we pass through a series of ingredients (a gang, a motive, an alibi, a chase, a coroner, etc.) that seem to allude to the very process of construction of the narrated story and, more importantly, bring into play the generic expectations of the audience who, consistently with the conventions of the thriller genre, find themselves wondering who the culprit of the staged conflict is.Footnote8 However, it soon becomes clear that the titles of the individual sections are entirely specious and, indeed, (self)ironic, because as early as chapter ‘3. Una sventola che sia disposta a cantare’ we find out that the doll (the sventola) willing to provide information (cantare) about the crime is none other than a young Chinese immigrant, Isabella, who is shown taking opera singing lessons and afterwards talking about her future while lying in bed with her boyfriend David. In this way what seems to be the main purpose of Giallo a Milano begins taking shape: to give voice, through a process of situated individuation, to a bunch of people from the Milan’s Chinese community, who armed with their words and daily lives dismantle the stereotypes circulating about themselves. It is truly a mosaic of different stories, which capture the complexity of reality and offer an authentic and diversified cross-section of this population. A variety of subjects are thus encountered: from the irregular immigrant turned collaborator of justice who recalls the events of his migration to the couple of young parents who discuss how to get their son back to themselves in Italy; from the second-generation theatre actor to the émigré painter who reflect on their identity and discuss their condition straddling two cultures; from the successful Italian-Chinese entrepreneur who recalls the beginnings of Chinese migration to Milan to the second and third-generation children who attend a school to learn standard Chinese or, again, to the women who discuss the problems of motherhood and child rearing while sitting in the waiting room of a hospital. A glance at the Chinese community that offers a complex representation and tries to resist, in the words of the director himself, the ‘tendency to simplify in the media today, to demonize complexity, which I don’t subscribe to’ (Bonsaver Citation2011, 311).

Thus, in order to account for a complex reality, Basso’s documentary presents an equally complex structure, which makes intermedial hybridism its stylistic hallmark thanks to the extensive use of different materials ranging from animated sequences, vintage photos and archive footage to home movies shot in Super8 and found footage. Moreover, a similar approach that works with intermedial references is also visible in Basso’s publication of a cross-media platform on the Corriere della Sera website, which hosts the first example of an i-doc produced in Italy, Made in Chinatown (Citation2010),Footnote9 in which the more informative aspect prevails: allowing the user to move freely through the three navigation menus of the ‘map of Milan’, the ‘characters’ and the ‘archetypes’, it takes on a pronounced ‘expository mode, [that] emphasizes verbal commentary and an argumentative logic’ (Nichols Citation2001, 33), ‘potentially offers greater narrative agency to the user’ (Chung and Luciano Citation2015, 206) and ‘give[s] a much greater impression of a “rhizomatic” journey based on “contiguity and chance”’ (ibid., 209).

Animating transnational migration to make its narration possible: the police informant

One of the most evident aspects of Basso’s intermedial approach is the use of animation in chapters ‘2. If only the dead could speak’ and ‘6. An informer’, in which the irregular migration of a young man from the Chinese province to Milan is recounted. The use of animation to narrate reality, which runs like a subterranean thread through the entire history of the documentary genre (Formenti Citation2016, 7–8), has become one of the privileged tools of expression in contemporary Italy.Footnote10 Animation, not limiting itself to a merely ‘indexical’ (Nichols Citation2001, 35) recording of reality, tends to reinvent it, highlighting not so much the ‘mimetic aspect of reproduction’ as the ‘performative aspect of creation’ (Mileto Citation2020). This is a true manipulation of the documentary image, in which what emerges is not reality itself, but rather its ‘narrative dimension that transcends reality and looks at it from above, from afar, from outside’ (ibid.). The latter stands, in its explicit artificiality, as a privileged place to ‘interrogate images’, to account for the ‘slippage between the media horizon and the experience of the world’ and, ultimately, to ‘think about the artificiality of the reality we have often called the world’ (Dottorini Citation2020).

Moreover, what emerges most strongly in contemporary animated documentary is the subjectivity of the author, ‘giving an account of an aspect of reality through the testimonies of one or more individuals who have experienced it personally’ - a way of offering the audience not so much ‘absolute truths and objective narratives, but one or more standpoints on it’ (Formenti Citation2016, 252). This subjectivity is often characterised by its overtly autobiographical dimension, in which what matters is the restitution of personal visions of the factual and the externalisation of individual memories. The animated documentary thus becomes a ‘cinema of the self’ (ibid., 253), in which the foreground is ‘the subjective and experiential, an awareness of what it feels like to live in the world in a particular way’ (Nichols, ibid.), so much so that the term ‘docu-memoir’ was coined for this type of audio-visual product (Cassady, ibid.).

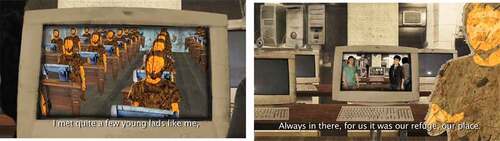

In Basso’s case, the use of animation, which provokes a strong effect of estrangement, also has a more immediately pragmatic motivation: to make possible a narrative that would otherwise be impossible. The two chapters tell indeed the story of a young Chinese man who, after having immigrated to Italy in the footsteps of his brother who had meanwhile ended up in prison, became a collaborator of justice following a murder perpetrated by some of his fellow countrymen, for which a live performance would have compromised his safety. Faced with the problem of protecting his identity, Basso opted for animation, entrusting its realization to Lorenzo Latrofa of the Roman artistic collective La Testuggine, who made use of a wide range of techniques, such as 2D animation, animated photographs, collage of fragments of newspapers and official documents and, indeed, a sort of ‘mobile’ pixelation aimed at covering the face of the collaborator of justice and making it impossible to identify him ().

However, beyond these extrinsic motivations, it is the subjective and autobiographical story of the character that emerges in the two scenes, making the audience aware of his intimate thoughts and emotions. In fact, the narration is conducted in the first person in Chinese with a voice-over that simultaneously interprets for the Italian audience. In particular, the first chapter lingers on the character’s past and on the circumstances that led him to emigrate from China to Milan via Russia. There he stayed for more than a year at the mercy of a group of Russian smugglers who, in addition to profiting heavily from the business of irregular migration, did not refrain from inflicting violence of various kinds on him and on a young girl from his country, a victim of sexual violence. The man also tells his desire to lead an honest life, a goal he finally achieved thanks to his acquaintance with a second-generation Chinese girl, born and raised in Milan, who became the entrepreneur of a small youth ‘ready-to-wear’ fashion company. In this scene, one of Basso’s frequent stylistic features stands out, i.e. the mise-en-abyme procedure, for example, when the character recalls the ‘little honest work’ he did after arriving in Milan and is seen at work seated in front of a stapler, an image that is suddenly multiplied in series, before a backwards tracking shot reveals it progressively framed by a computer screen, in turn framed by another screen and another as the camera moves backwards ().

This is about the infinity of screens of the numerous internet points of via Sarpi, that is the usual gather ground of the Chinese in Milan, especially of those who do not want to surrender to a destiny already doomed and try to work hard to build a better future for themselves. This procedure, in addition to conferring a further level of complexity and reflexivity to Basso’s documentary image, alludes to the plurality of worlds that are connected in a continuous cross-reference between the particular and the universal, the local, the national and the transnational through the use of digital technologies and documents the emergence of a new notion of community among Chinese immigrants in Milan, one in which the factors of socialisation and solidarity among individuals are no longer limited to the sharing of a physical space and a supposedly common identity as it is often theorised in popular and mainstream mass media discourse.

Respatialising (post)migrant identity through photography and theatre: The sino-Italian actor Shi Yang

The story of the second-generation, homosexual actor Shi Yang and his parents Pietro and Guendalina, told in fragments in chapters 11, 13 and 15, offers a highlight of two other aspects of Basso’s aesthetic approach which, as already mentioned, makes systematic use of intermedial references to counterpose the dominant narrative with a more truthful counter-narrative of (post-)migrant identities. In this way, the use of different linguistic and stylistic devices coincides with an attempt to resist the presumed objectivity and linearity of the mass media discourse, giving life to an aesthetically sophisticated representation with undoubted political overtones. In this specific case, photography and theatrical performance are the two languages through which the characters perform their identity and renegotiate their migratory experience, as well as, as Parati argues, ‘re-spatialise Milanese culture’ (Parati Citation2017, 115) thanks to the specific use of the spaces in which the narrative of the Shi family is set.

This last aspect becomes clear when considering the choice of the location where the audience meets the Shi family, namely the Rotonda della Besana, a highly symbolic place for Milanese and Italian national culture. The scene opens with a split screen showing Yang and his parents in long shot inside the Rotonda’s portico, where there are giant photographs of an exhibition about Chinese people living in Milan. The camera then cuts to the three, now seated under an archway of the portico, filming them in close-up as they discuss the reasons why the father would like to return to China after a 14-year migration. Pietro argues that in Italy he does not feel free and that he wants to return to China to take care of his elderly and widowed mother, thus giving expression to that value so important in Confucian culture that is filial piety. Guendalina, however, is offended by the fact that she is placed on the same level as her mother-in-law by a husband by whom she does not feel understood. She adds that she much prefers Italian culture to Chinese one, mainly because of the interpersonal relationships that she thinks would be less hypocritical, as she argues reminding her husband of their last stay in China, during which her mother-in-law had forbidden them to sleep together even though they had been married for a long time. Guendalina’s rage culminates in the ‘umbrella gesture’, by which she expresses all her disappointment by bending her left arm with her right hand resting at the level of her elbow, a gesture that her son Yang promptly corrects by teaching her the right way to do it – that is, backwards – in a scene in which the young man literally gives his mother the gestural tools to express her inner feelings ().

The most interesting aspect in this scene regarding Basso’s intermedial approach is the use of photography inside the Rotonda della Besana, which recalls the concept of ‘re-spatialization of culture’ proposed by Parati. In fact, the scholar traces the history of this symbolical building and points out how in the 19th century several attempts were made to transform it from an originally religious institution ‘into a Pantheon of the Italian Kingdom that would celebrate the royal family of Savoy and the unification of Italy’ (Parati Citation2017, 113). However, these attempts were never completed, making sure that ‘[t]he Besana escaped being reified into a post-unification monument that would be “evidence of official rather than popular memorialization” […], a celebratory monument for the ruling class’ (ibid.). Parati recalls how this space was opened to public use since the 1950s, becoming the site of numerous temporary art exhibitions. In this way the choice of setting the conversation of the Shi family in this place evidently alludes to the claim of the Chinese community of Milan to get out of the narrow spaces of the Chinatown around Via Sarpi and to take possession of a public space that has a strong symbolic value in the cultural geography of the city. Moreover, Parati points out how Basso ‘uses the architectural structures [of the Besana] to multiply the visibility of the Chinese’ through the ‘mise-en-abyme of identities’ (ibid., 114) represented by the photographs that stand out in the arcade – a procedure that adds a further level of self-reflexivity and induces the audience to reflect on the very process of construction of the documentary discourse. In this regard, it is significant to note a very brief shot edited into the scene in which a presumably Italian woman is shown wandering around the portico and observing the photographs on display while the Shi family continues its conversation in voice-over.

If, on the one hand, the insert seems to allude to the fact that ethnic otherness is often presented as a mere spectacle to be ‘possessed’ with the gaze or, extending the concept proposed in the feminist field by Laura Mulvey, as something that has the mere status of ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’ (Mulvey Citation1975, 11), on the other it can be interpreted as Basso’s explicit attempt to make his audience aware of the constructed nature of the photographic image, encouraging them to assume a critical stance towards what is placed in front of their eyes ().

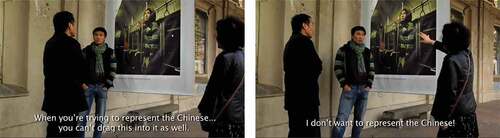

The complexity of the role that photography plays in the renegotiation of Yang’s identity is explicitly thematized in a subsequent sequence, in which the three characters comment on an image that portrays the young man inside a train of the Milanese subway, relating it to what is considered the ‘yin side’ of the boy, i.e. his declared homosexuality. Yang is proud of his performance, while his father appears rather disappointed, as ‘he focuses on his son’s rather androgynous features and hooded head that gives him a gender-neutral appearance’ (Parati Citation2017, 116). The father criticizes his son for openly displaying his sexuality and argues that he should avoid addressing the subject at a time when, through the photograph in which he is portrayed, he is called upon to represent their community of belonging ().

However, Yang’s response in front of his father’s objection is significant of his approach to his identity that, similarly to what Parati does to define Yang’s use of public spaces (ibid.), can be defined as ‘transitive’: in fact, he replies that according to his mother he would look more like a Filipino than a Chinese in that image and that in any case he has no desire to represent the ‘Chinese community’, claiming the right to perform his individual subjectivity and refusing the presumed duty to become the vehicle of others’ representation. In doing so, Yang firmly rejects that ‘burden of representation’ often affixed to people who are considered representatives of a minority ethnic or social group and who are presumed to lack control over their own representation (Shohat and Stam Citation1994, 184).

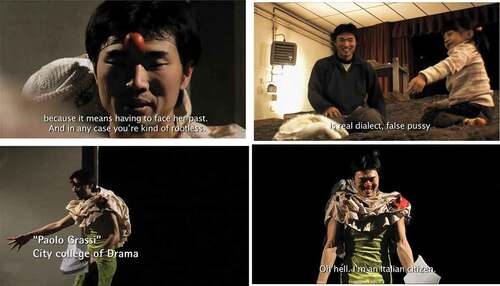

Finally, the other language through which Yang’s story is mediated cannot go unmentioned, that is his performance as a theatrical actor, which creates a ‘representation within a representtation’ or a representation of the second order, a typical way in which ‘the film interrupts the logical course of the narrative and addresses the viewer directly’ (Piemontese Citation2003). In fact, the scenes at the Besana are alternated with others that portray the young man, now disguised as an old Chinese peasant woman, performing some fragments of his migratory memory on the stage of the Milanese Scuola civica d’Arte drammatica ‘Paolo Grassi’. These are the most openly intersectional sections of his story, in which his multiple identities of social class, nationality, gender and sexual orientation are performed on stage and in front of the camera. It is also a performativity that closely reminds of Judith Butler’s theorizing on parody and drag as a means of subverting binary categories of gender, according to which ‘[t]he task is not whether to repeat, but how to repeat, or, indeed to repeat and, through a radical proliferation of gender, to displace the very gender norms that enable the repetition itself’ (Butler Citation1990, 148).

In the first of these sections, we see Yang telling an off-screen female voice interviewing him – in one of those rare moments of the documentary that Nichols would frame as ‘participatory mode’ (Nichols Citation2001, 115–124) – about the enormous economic developments that China has gone through in recent years, a situation that has led many Chinese who had emigrated abroad to consider the possibility of a return migration, unlike his mother Guendalina, who would now feel ‘uprooted’ in China; later on, the young man tries to sing the Chinese national anthem, but fails because he has forgotten the lyrics, thus ending up wondering whether he should consider himself a Chinese or rather an Italian citizen, as he finally seems to conclude without much conviction; then he is shown recalling on stage the abuses that he and his mother had to suffer during the first years of their migration to Italy, in particular when he recounts how, as a 12-years-old kid, he used to work in a restaurant in Calabria pretending to be 16; finally, while playing with a little girl in the theatre, his voice-over recalls the offensive words that were addressed to him as a child because of his habit of dressing up as a fairy using a white sheet () – a scene, the latter, to which the aforementioned scene in which Yang and his parents talk about his homosexuality at the Besana is edited, in such a way that a thematic continuum is established from two different narrative fragments.

All these fragments of life, which Yang performs on stage in the form of an interview, a real performance or even just an oral story, besides testifying to the extreme diversification pursued by Basso in dealing with his subject, contribute to making the figure of the character extremely multifaceted, letting the audience guess the complexity and conflictual condition in which post-migrant identities find themselves and, in a broader sense, the constructed aspect of the identity categories with which people define and identify themselves.

Painting migration with the brush: The painter Ho Kan and the intermedial ekphrasis

Finally, I would like to focus on the scenes staging the conceptual art painter Ho Kan, one of the most important painters of the Chinese independent art scene, and his student Chen Gong, narrated in chapters 12 and 13, (‘An old man who knew too much’ and ‘His young accomplice’) in order to highlight two further stylistic processes through which Basso mediates the migratory and existential experience of his subjects, namely the extensive use of archival material and home movies on the one hand and painting on the other. Once again, Basso’s main objective lies in the complexification of an overly simplistic and linear narrative, which is once again broken down, fragmented, and multiplied to make the public’s perspective more critical and conscious.

In the first chapter, archival materials and home movies are used to create what has been called ‘“varied” time: an altered flow, in an attempt to escape the supposed naturalness of the images’ (Bertozzi Citation2013, 122). In the scene, Ho Kan is initially surrounded by a group of Chinese art students from the Brera Academy of Fine Arts as he recalls the events of his emigration from Taiwan, where he took refuge at the time of the Cultural Revolution in China, first to Paris and then to Milan. The story is supported by multiple images introduced with the technique of the split screen, which in this case seem to support the words of the man. Immediately afterwards, Basso edits a scene taken from a Taiwanese television report of 1984, where a journalist interviews the painter about his activity as an artist in Milan. A temporal shift brings us back to the present, where Ho Kan, back at the Brera Academy, completes the story of his migration by recalling episodes related to his childhood, his escape to Taiwan in 1949 and finally the circumstances that led him to move from Paris to Milan. All these phases of the story are punctuated by archive footage of the civil war in China and his journey to Europe, inserted to make his narrative more vivid and easily understood to the Italian audience, as well as by home movies of Ho Kan himself as a young man walking through the streets of Milan (). This creates an alienating vision, in which editing is no longer used to construct ‘a single, unitary, linear sense, [but] now works on the disappearance of that sense through the collision of different times, invisible in ordinary perception’ (ibid.), but made visible by the inclusion of these intermedial formats through the split screen and multiple screens within the same frame.

The next chapter, on the other hand, opens with a lateral tracking shot detailing the first work created by the young Chen Gong after his arrival in Italy. The description of his painting, which depicts the Chinese flag with five question marks instead of the original five stars, becomes an opportunity to express his innermost thoughts and to negotiate the meaning of his own migration experience, through an interesting example of intermedial ekphrasis, or ‘literary description of works of art, [or] cinematic citation of pictorial works’ (Fusillo and Terrosi Citation2015), which, once again, is focused on the theme of identity. Indeed, the young artist explains his refusal to be identified as a Chinese by virtue of his mere physiognomic characteristics and motivates his emigration to Italy with the need to ‘let himself be watered by new water’.

His discourse then develops on broader horizons: shot from behind in full-length with his work in the background, the boy wonders what it means to be Chinese today, what the hidden meaning of the flag is, and whether the five stars it originally depicted simply signify the aspiration for material wealth, to which so many of his compatriots seem to yearn, or whether the aspirations that the Chinese ruling class must guarantee to its people should be of a very different nature. Thus, the description of his work serves as a pretext to talk about his intimate thoughts and political convictions and to give the Italian public tangible proof of the young migrant’s hybrid and floating identity, as his last words confirm: ‘I don’t belong to one country in China: I’m leaving China, but my destination is unknown’. And this is indeed the political message Basso addresses to the audience of his documentary, the invitation to embrace fluidity and not to cling to a rigid and unchangeable notion of identity.

Conclusion

To resume what has been discussed so far, Giallo a Milano can be considered an excellent example of the hybrid aesthetic that characterizes contemporary Italian documentaries. Furthermore, it shows with great clarity how the transmission of ‘objective’ information – or, to put it in Nichols’ words, the ‘epistephilia’ (Nichols Citation2001, 40) that characterize the documentary genre – can be achieved through a multiplicity of approaches that openly eschew the assumed objectivity often touted by dominant mass media discourses. As we have seen, Basso’s documentary draws extensively from and exhausts almost all modes of intermedial representation of the documentary genre, with the explicit intention of offering an alternative, frankly ‘constructed’ vision of reality, knowing that there is no im-mediated access to reality, just as there is no unique and universal notion of reality itself.

Basso achieves this through an outspokenly intermedial approach, in which intermedial combinations and references play a central role. As we have seen, his formal and aesthetic research makes wide use of different linguistic and stylistic codes that, if in some cases they make otherwise impossible narratives possible (as in the two animated sequences), in other cases they provide the tool through which one can better illustrate one’s own view of a particular subject (photography and theatre in Shi Yang’s episodes) or connect personal data to broader and general issues (as in Chen Gong’s ekphrasis). In doing so, Basso draws extensively from the most disparate media, such as animation, photography, painting and archival materials, but he never does so in a trivial way, rather in order to create a real surplus of signification of what is displayed on the screen.

The goal of his way of talking about the Chinese community in Milan seems to lie in the deconstruction of the very idea of ‘community’ itself. His documentary, which in the words of Stella Bruzzi (Citation2000, 99), revolves around encounters, presenting multiple subjective perspectives in a continuous narrative journey in search of people and voices, thus adopts a strategy aimed at providing a ‘voice to the voiceless’, allowing the audience to ‘hear people tell their stories and observe their lives instead of being told what they think and the meaning of their behaviour’ (Ruby Citation1991, 51). The thick aura of mystery that surrounds the Chinese community in Milan is thus resolved: there is no such thing as a single or homogeneous Chinese community in Milan, but – in the director’s own words – only ‘a myriad of people just like us. And every human being is a thread of history, you only need to pull it’ (Turrini Citation2011, IV).

Disclosure statement

I confirm that there are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mario Vincenzo Casale

Mario V. Casale is researcher within the FWF project Cinema of Migration in Italy since 1990 and senior lecturer at the Department of Romance Studies, University of Innsbruck.

Notes

1. This article is part of the research project “Cinema of migration in Italy since 1990” (P 30537) of the Austrian Science Fund.

2. Regarding the myth of the immortality of the Chinese see, for example, Gomorrah (Garrone (2008) and Gorbaciof (Incerti 2010) for a treatment of illegal activities such as gambling and the exploitation of prostitution.

3. Among his fiction films see for example Elementary Loves (2014), while among his documentaries at least the recent Sarita (2019), the latter being the subject of Sabine Schrader’s article in this volume (see below).

4. Dottorini (2013) identifies the following four characteristics: the ‘montage of the real’, that is, ‘[its] capacity […] to create forms that call into question the concept and practice of montage, proposing new declinations, new perspectives’ (19); the ‘profanation as a political form’, understood in the Agambenian sense as ‘restoring to public use what is sacred, separate’, with the camera showing ‘spaces closed to collective vision in order to restore them to visibility’ (ibid.); what is defined, using an expression by Benjamin, as ‘working with rags’, that is, the practice of cinema that uses home movies and found footage to ‘rethink the archive and the images that have been forgotten or too quickly archived’, thus becoming ‘a place of interrogation of the image, of its memory and its possibility of (re)activation’ (20); and finally the ‘hybridizations’ of the modes of cinematic storytelling, which can be achieved in the ‘work of mixing and matching languages and codes’ (21), as demonstrated by the emergence of the animation documentary.

5. The audio track of the television report was re-created from scratch and inserted a posteriori with obvious parodic purposes of the alarmist tone with which the Italian mainstream media report news about migration. This parodistic intent is also manifested in the logo of the news programme (TGX), which closely resembles the graphics of the well-known TG5 news programme of the Berlusconi-owned Mediaset group, where the X seems to refer, ironically and critically, to the qualunquismo of much of the TV reporting. I would like to thank Sergio Basso for providing me with this and other valuable information during our virtual conversation.

6. The choice of staging the anti-Chinese stereotype through the voice-over of two unseen women cannot help but recall, in an ironic way, the notion of ‘disembodied voices’ discussed by Kaja Silverman (1994). According to her, the voice-over – a voice detached from one’s body whose source remains invisible – is a procedure that classical cinema has traditionally reserved for male characters to give them an authority superior to that of diegetic characters. In other words, the over-voice used here to give substance to the anti-Chinese stereotype contributes to giving it a universal authority and validity and to connoting it as something that everyone professes without daring to put their face on.

7. It is worth remembering that polysemy is, according to Roland Barthes (1970), the characteristic through which to distinguish between open and closed texts, where an open text is characterised by the fact that it invites the reader/viewer to actively appreciate and benefit from its polysemic potential.

8. Zhang (2013, 31–32) argues that the use of such a narrative structure not only allows the film to broaden the spectrum of possible topics used to represent the Chinese in Italy and the audience to experience Chinese immigration to Milan through the perspective of migrants, but also alludes to the question of what can be known about the Chinese and what to do with this knowledge.

9. Accessible at: https://www.corriere.it/spettacoli/speciali/2010/giallo-a-milano/.

10. It would be very interesting to make a comparison with other Italian productions that make use of the animation technique, which I unfortunately cannot do here for reasons of space. For some examples of Italian animation documentary see, for example, Samouni Road (2018) by Stefano Savona, We want roses too (2007) and Tutto parla di te [Everything Speaks of You] (2012) by Alina Marazzi, as well as The Years (2018) by Sara Fgaier.

References

- Amori elementari [Elementary Loves]. 2014. Directed by Sergio Basso. Italy/Russia: CSC Production/Sharoncinema Production.

- Barthes, R. 1970. S/Z. Paris: Seuil.

- Bertozzi, M. 2012. Di alcune tendenze del documentario italiano nel terzo millennio. In Il reale allo specchio. Il documentario italiano contemporaneo, ed. G. Spagnoletti, 17–32. Venezia: Marsilio.

- Bertozzi, M. 2013. Cinema, memoria e pratiche dell’archivio. In Per un cinema del reale. Forme e pratiche del documentario italiano contemporaneo, ed. D. Dottorini, 117–23. Udine: Forum.

- Bonsaver, G. 2011. The aesthetics of documentary filmmaking and Giallo a Milano: An interview with film director Sergio Basso and sociologist Daniele Cologna. The Italianist 31, no. 2: 304–18. doi:10.1179/026143411X13051090964974.

- Bruzzi, S. 2000. New documentary: A critical edition. London: Routledge.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

- Chung, H., and B. Luciano 2015. Autonomous navigation? Multiplicity and Self-reflexive Aesthetics in Sergio Basso’s Documentary Film Giallo a Milano and Web Documentary Made in Chinatown. In Post-1990 documentary: Reconfiguring indipendence, ed. C. Deprez and J. Pernin. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 203–16.

- Dimmi chi sono [Sarita]. 2019. Directed by Sergio Basso. Italy/Germany: La Sarraz Pictures/National Media Production.

- Dottorini, D. 2013. Per un cinema del reale. Forme e pratiche del documentario italiano contemporaneo. Udine: Forum.

- Dottorini, D. 2020. Il mondo (ri)animato. https://www.fatamorganaweb.it/speciale-animazione/.

- Formenti, C. 2016. Il documentario animato: storia, teoria ed estetica di una forma audiovisiva PhD Thesis, University of Milan.

- Fusillo, M., and R. Terrosi 2015. “Intermedialità”. In Enciclopedia Treccani online. https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/intermedialita_%28Enciclopedia-Italiana%29/.

- Giallo a Milano [Made in Chinatown]. 2009. Directed by Sergio Basso. Italy: La Sarraz Pictures/CSC Production.

- Gli anni [The Years]. 2018. Directed by Sara Fgaier. Italy/France: Grand Huit/Dugong Films.

- Gomorra [Gomorrah]. 2008. Directed by Matteo Garrone. Italy: Fandango/Rai Cinema.

- Gorbaciof. 2010. Directed by Stefano Incerti, Italy: Devon Cinematografica/Surf Film/The Bottom Line/Immagine e Cinema/Teatri Uniti.

- La strada dei Samouni [Samouni Road]. 2018. Directed by Stefano Savona. Italy/France: Dugong Production/Picofilms/Alter Ego Production/Rai Cinema/Arte France Cinéma.

- Made in Chinatown. 2010. Directed by Sergio Basso. Italy: La Sarraz Pictures/RCS Quotidiani. https://www.corriere.it/spettacoli/speciali/2010/giallo-a-milano/.

- Mileto, A. 2020. Il monologo animato. https://www.fatamorganaweb.it/speciale-animazione-documentario-contemporaneo/.

- Mulvey, L. 1975. Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen 16, no. 3: 6–18. doi:10.1093/screen/16.3.6.

- Nichols, B. 2001. Introduction to documentary. Bloomington-Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Parati, G. 2017. Migrant writers and urban space in Italy. proximities and affect in literature and film. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pedone, V. 2018. In the eye of the beholder: The orientalist representation of Chinese migrants in Italian documentaries. Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies 6, no. 1: 81–95. doi:10.1386/jicms.6.1.81_1.

- Piemontese, P. 2003. Cinema nel cinema, Enciclopedia del cinema Treccani, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/cinema-nel-cinema_%28Enciclopedia-del-Cinema%29/.

- Ruby, J. 1991. Speaking for, speaking about, speaking with or speaking alongside. Visual Anthropology Review 7, no. 2: 50–67. doi:10.1525/var.1991.7.2.50.

- Shohat, E., and R. Stam. 1994. Unthinking eurocentrism. multiculturalism and the media. London/New York: Routledge.

- Silverman, K. 1994. The acoustic mirror: The female voice in psychoanalysis and cinema. Bloomington, Ind: Indiana University Press.

- Turrini, D. 2011. Ecco il «dragone» milanese tra prima e seconda generazione. Liberazione M.R.C. Rome: January, 9th, IV.

- Tutto parla di te [Everything Speaks of You]. 2012. Directed by Alina Marazzi. Italy/Switzerland: MIR Cinematografica/Film Investment Piedmont/Intesa Sanpaolo.

- Vogliamo anche le rose [We Want Roses too] (2007). Directed by Alina Marazzi, Italy/Switzerland: Mir Cinematografica/Ventura Film/Rai Cinema/RTSI/CULT - Fox Channels Italy/Aamod/Yle Teema Ateljee.

- Zhang, G. 2013. The protest in Milan’s Chinatown and the Chinese Immigrants in Italy in the Media (2007-2009). Journal of Italian Cinema & Media Studies 1, no. 1: 21–37. doi:10.1386/jicms.1.1.21_1.

- Zhang, G. 2017. Chinese migrants, morality and ethics in Italian cinema. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 22, no. 3: 385–405. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2017.1321935.

- Zhang, G. 2019a. Migration and the Media. Debating Chinese Migration to Italy, 1992-2012. Toronto: Toronto University Press.

- Zhang, G. 2019b. “Frames and agendas in italian films about Chinese migrants.” In LEA – Lingue e letterature d’Oriente e d’Occidente, vol. 8 Natali, Ilaria. 124–37. Firenze: Firenze University Press.