ABSTRACT

In recent years, riding schools have opened their activities for younger children. Previous research has described the learning environment of the stable as strongly inspired by a traditional military discourse (Thorell 2017) and in strong contrast to other socialization arenas. The aim of this article is to increase the understanding of riding school activities for preschool children. Research questions concern why and how activities for young children are organized and handled, norms guiding these activities and how children and others participating are perceived. Sources consist of 452 riding schools’ websites and interviews with nine representatives from riding schools. The analytical framework derives from the sociology of childhood. The study shows that a majority of the Swedish riding schools offer activities for preschool children. The activities are framed by contrasting ideas about the competent child, the child’s biological and vulnerable body, incompetent parents, competent youth leaders, and horses.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2021.2015333 .

Introduction

One hundred years ago, equestrianism in Sweden was primarily an activity for military men, or men and women from the upper classes. Many riding clubs, organized riding activities and competitions were formed in close connection to the military facilities. After World War II, a new kind of riding club—the horse-riding school—was established, and increased rapidly in numbers (Hedenborg Citation2013). Currently, riding instructors were frequently former officers. Over time the riding schools attracted an increasing number of children and young people and the activities for these groups became, like other sport activities for these age groups within the Swedish Sports Confederation, publicly subsidized.

Today, the number of riding horses is at an all-time high in Sweden and riding is one of the most popular sports among girls and young women. Typically, riding schools offer riding lessons every week, with some riding schools holding lessons several days a week and multiple hours daily. Between 10–12 people participate in one-hour lessons on horses owned by the riding school. Riding lessons are often complemented with theoretical classes (theory) on equine care. The riding and theory lessons are often led by riding instructors (Thorell Citation2017). As part of their professional role, they conduct teaching and are usually responsible for tasks related to the daily care of horses as well, the operation of the facilities, and administration (Smith Citation2009).

Despite many changes in the activities of the riding schools, previous research has demonstrated that the riding schools’ learning environment is still strongly inspired by a traditional military discourse characterized by commands such as: ‘Forward march!’ (Thorell Citation2017). The discourse presupposes immediate obedience, sometimes penalism, that the instructor has authority and that he or she is not to be questioned (c.f. Sörensen Citation1997). It has been accepted in the riding school as it is described as ensuring safety through strict rules and procedures (Thorell Citation2017).

Up until the last decade, many riding schools in Sweden maintained a sharp age limit of seven years for riding lessons—an age limit possibly connected to the age at which children were to start school. At seven years, children in the riding school were considered receptive to instructions and—in terms of safety—ready to start riding. In recent years, however, riding schools have opened their activities for younger children, with several forms of activities being offered to preschool children. This development is likely connected to other sports offering activities for this age group. Previous research has demonstrated that when asked, riding teachers discuss economic reasons for these offers still claiming that, ‘they are too young’ (Thorell Citation2017).

The military discourse is coupled with other fostering aspects. Swedish children and youth sports have been seen as existing in tension between two fostering logics—fostering the democratic citizen and fostering for competition (SOU Citation2008:59). In equestrian sport, another type of fostering has been central—care fostering. In order to become what is perceived as a real, ‘horsey’ person, young people learn to care for horses in the stable environment (Hedenborg Citation2009).

The learning environment of the stable seems to be in strong contrast to other socialization arenas where young children participate. Modern educational theory points to that children in school are to be seen as active agents capable of developing and learning—a social construction based on an idea of the competent child (Samuelsson Pramling and Carlsson Asplund Citation2003; Brembeck, Johansson, and Kampmann Citation2008). Although previous research has questioned whether this construction has been dominant within preschool education, it has been suggested that even preschool activities (at least in some preschools) have been guided by these ideas (c.f. Månsson Citation2008).

These contrasting ideas found in different socialization arenas for children made us interested in studying why and how activities for young children are organized and handled, which norms guiding these activities have developed and how children and others participating in these activities are perceived. The aim of this article is therefore to increase the understanding of riding school activities for preschool children (defined here as children between the ages 0–6 years, independent of whether they attend preschool or not). Research questions are developed further in the section Analytical framework.

In general, there is little research on younger children compared to the number of studies of older children, adolescents, and adults (Söderlind and Engwall Citation2005). It has been suggested that the youngest children have been marginalized because of their subordinate position in society (Corsaro Citation2005; Prout and James Citation1997; Qvotrup Citation2009). This also applies to research in sports sciences (Hedenborg and Fransson Citation2011; Harlow and Fraser-Thomas Citation2019), and even though the number of preschool age participants in organized sports has increased in the last decade, research on sports activities for this age group is scant and little is known about how these activities are motivated, perceived, and organized (Solenes & Hedenborg, forthcoming).

The study is based on 9 semi structured interviews with representatives of riding schools and mapping of 462 riding schools’ websites, theoretically focusing the concepts of the competent child and being—becoming a rider.

Analytical framework

The analytical framework for this article derives from the sociology of childhood (Hedenborg Citation2006; James and James Citation2004, Citation2012; Prout Citation2005; Qvotrup Citation2009). A starting point for sociology of childhood, is that childhood is viewed as socially constructed and historically and culturally contingent. A dominant construction of childhood in child culture research and modern educational theory is that of the competent child, i.e. an active agent capable of developing and learning (Samuelsson Pramling and Carlsson Asplund Citation2003; Brembeck, Johansson, and Kampmann Citation2008; Månsson Citation2008). In the preschool arena, this construction exists in tension with the notion of the vulnerable, ignorant, and incomplete child (Brembeck, Johansson, and Kampmann Citation2008).

One socialization arena of importance for children seems to contradict the idea of the competent child—sports. Previous research on children and youth sports has focused on the socialization aspects of sports associations, indicating the dual, and conflicting, missions of fostering children to democratic citizens as well as elite athletes (SOU Citation2008:59). It has been observed that a narrow focus on results and performance may alienate some children and young people, causing them to lose interest in sports and physical activity (Redelius Citation2011; Norberg and Redelius Citation2013; Thedin Jakobsson Citation2013). Furthermore, sports activities have been claimed to be socially, psychologically, and physiologically harmful for some children and young people (Fasting, Brackenridge, and Kjölberg Citation2013). The idea of the competent child seems absent in this research, which instead appears to hinge on the notion of the vulnerable child in need of protection. In the military tradition of the riding school, neither the competent child, nor the vulnerable child seems to be present. The first research question is therefore whether the idea of the competent child is present in the design of young children’s riding activities, or if these activities instead are guided by other perceptions of childhood. The construction of childhood influences ideas about learning. Above, this was discussed in relation to the military tradition of authority and obedience. In other pedagogical traditions, experiences of coping, and to some extent mastering a body, are seen as important for children’s involvement, learning, and motivation (Jensen and Osnes Citation2009). Excitement is viewed as a driving force in all games and is considered a feeling and experience that lies somewhere between fear and lust (Flemmen Citation1987). These contrasting ideas have led us to the second research question: How is the learning environment constructed in the activities for young children in the riding school?

A small number of previous studies illustrate children’s decision-making opportunities in sports (for Sweden, see SOU Citation2008:59; Trondman Citation2011). However, this research has not discussed or problematized age-related power relations. The importance of children’s agency and of making children’s voices heard, as well as how different groups of children have or have not been given agency, has been extensively theorized within the sociology of childhood (James Citation2007; Spyrou Citation2011, Citation2016; Lancy Citation2012). Furthermore, sociologist Leena Alanen underlines that ‘child’ is a relational concept (Alanen Citation2001, c.f. Hendrick Citation1997; Hedenborg Citation2007, Citation2012). She has coined the notion ‘generationing’ to denote the practices through which one becomes constructed as a child in relation to others. Generationing is a process, in which power relations are contested and re-established. The third research question is: How is the young rider socially constructed in in relation to other relevant groups in the horse-riding school.

Studies guided by the sociology of childhood, have pointed to that children often have been constructed as human ‘becomings’ rather than human ‘beings’ (James and Prout Citation2014). The becoming child has been seen as a human, lacking competencies of the adult person (Kingdon Citation2018; Lee Citation2001). This has, however, been questioned and Lee (Citation2001) has argued that the sociology of childhood needs to recognize childhood as both being and becoming. The fourth question for this study is if, and in that case how, perceptions of being and becoming have influenced the social construction of the young rider and other groups.

In order to understand the social construction of the young rider, we also draw on insights from human-animal studies. An analysis of Swedish riding manuals from the twentieth century indicates a shift away from a relationship based on the notion of the horse as a tool expected to obey the rider. Based on this understanding, riding was seen as the one-way transmission of orders from rider to horse, where specific signals were expected consistently to produce specific movements. Consequently, it was expected that all horses could be trained in the same way. More recently, another way of interpreting the horse–human relationship has become evident in Swedish riding manuals, in which horses are now seen as individuals and as thinking and feeling subjects (Zetterqvist Blokhuis Citation2019). The fifth question for our study is: How are horses perceived in the activities for young children?

The swedish riding school

In a public report from 1948, horse riding was described as a ‘sport for all’ and a physical activity of importance for a sedentary population. These rationales, coupled with arguments connected to that it was important for Sweden to be self-sufficient in terms of horses (in case of a new war outbreak), spurred the increase of riding schools.

Today riding school ownership and management forms vary. In some cases, an association owns the horses, facilities, and land, while in others a private owner or the municipality co-owns the business with an equestrian association (Smith Citation2009). Although organizational forms differ, most riding school activities have a ‘sports for all’ orientation, rather than being geared towards the elite (Hedenborg Citation2013; Thorell and Hedenborg Citation2015). Like other Swedish sports associations for children and young people, contemporary horse-riding associations receive municipal and government subsidies for their activities in horse riding schools.

In 1988, the author Ulla Ståhlberg published the book Att lära barn rida (Eng., ‘Teaching Children How to Ride’). She had been appointed this task by the Swedish Equestrian Federation, which in 1986 received a grant from the Ministry of Social Affairs aimed at developing an equestrian training guide for children (Ståhlberg Citation1996). This can be seen as an indication that the federation wanted the riding instructors to learn more about how to adapt their pedagogy and teaching methodology to a new age group in the riding school. Nevertheless, the riding schools’ learning environment continued to be strongly inspired by a traditional military discourse characterized by commands such as: ‘Forward march!’ (Thorell Citation2017).

Sources and methods

Both quantitative and qualitative data have been used for the analysis (c.f. Gorard and Makopoulou Citation2012). The quantitative data derive from a mapping of horse-riding schools’ websites and their activities for young children, whereas the qualitative data were gathered in interviews with representatives from nine different riding schools.

Websites

In this article we focus on riding schools that are members of the Swedish Equestrian Federation. In Sweden the majority of riding activities for children are offered within the frame of the Swedish Equestrian Federation (SEF), as being a member is a condition for receiving subsidies. In this article, the websites of all riding schools (462) in SEF have been studied. The websites were examined in relation to whether they advertised activities for preschool children and what these activities entailed. Footnote1 The latter question could not be answered by studying the websites. In order to understand whether activities were aiming at younger children, the riding schools’ presentations of age limits were examined. The study of the Swedish riding schools’ websites took place in the spring of 2018.

Complicating our survey, about 7% of the riding schools had inactive websites or websites with outdated information. This was especially the case for smaller riding schools in rural areas. Riding schools whose websites presented incomplete information were examined on Facebook, where further information could be obtained. This means that 93% of all riding schools had relevant data on their websites, and these websites we used to answer the questions posed.

Interviews

The second source material for this article consists of nine semi-structured interviews with representatives (4 managers, 4 head instructors, and 1 administrative staff member) of nine Swedish riding schools. In this article the riding schools have been given pseudonyms as Riding school Hoof. The riding schools belonged to different districts and represented both urban and rural areas. In order to understand preschool children’s riding sport activities the interviewees were asked 15 questions about how activities for preschool children were organized, the age of the child, the educational level of the instructor, safety equipment, the horses used and about their personal opinions of these activities in relation to the human participants (parents and children) as well as the horses. Interviews were mainly conducted over the phone, one face-to-face and due to time limitation one interview was conducted in written form answering the same questions. All interviews followed an interview guide with 15 fixed questions. The interviews had an average length of 30 minutes, and the oral interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Method of analysis

Information and data from 462 riding schools’ website texts were organized in an excel sheet in categories. These categories were; if the riding school had activities for preschool children; age; name of the activity; content of activity/class, riding and or grooming; information about instructor; price; length of activity/class.

The interviews were conducted based on an interview guide with 15 questions concerning arrangement and content of the activity, age, education of the instructors, safety arrangement and equipment, horses used in the activity, learning methods, what groups facilitate and enables preschool children to ride. The excel sheet with data and the transcribed interviews were read and re-read by the authors of this article. All three authors are experienced riders and have practiced riding at riding schools and therefore have developed an interpretation and a pre-understanding of what riding at riding school can be. This has shaped our understanding of, and reflections on, the activities for preschool children, the horse, and the process of being and becoming a rider. Based on the empirical data, our preconceptions and the analytical framework we identified and organized the data in themes. The following themes were identified: the competent child, learning through play, the biological body and mind as restrictions, the vulnerable body, the incompetent adult, the competent youth leader, and the competent horse.

Preschool children and the horse-riding school

The competent child

The examination of the riding schools’ websites demonstrated that just over half of all riding schools within the Swedish Equestrian Federation offer activities for preschool children (54%, see ). The riding schools used various terms to advertise these activities, including ‘riding kindergarten’, ‘play and learn’, ‘horsey mates’, ‘tiny tots riding’ and ponyfun’. In the analysis, we have distinguished between riding-only activities and activities that included riding as well as activities in the stable (such as grooming horses, saddling, and bridling).

Table 1. Number and proportion (%) of riding schools who offer activities for preschool children. Riding schools within the Swedish Equestrian Federation.

In , the two main categories are called ‘tiny tots riding and ‘riding kindergarten respectively. The first category, tiny tots riding, indicates that the content is adapted mainly to fit very young children. The second category, riding kindergarten, instead uses terminology from the preschool world. The word ‘kindergarten’ combined with the word ‘riding’ suggests that the content offers learning in a wider perspective. Tiny tots riding made up almost half of the activities offered to preschool children, while riding kindergarten made up just over half of these activities. In some cases, it was difficult to determine what was included in the activities and whether they were only aiming at younger children. We have called this category ‘other’. It is likely that the category ‘other’ consists of activities partly aiming at preschool children but without a sharp limit or distinction between preschool and primary school children. About a third of the riding school websites examined did not provide information about whether they offered activities for younger children.

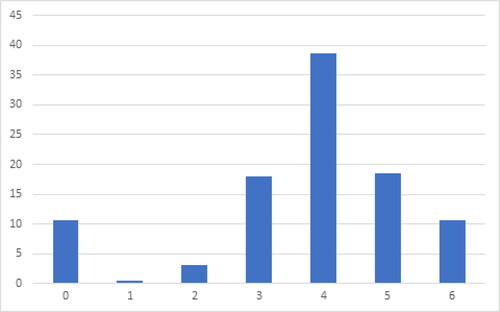

In contrast to what previous research has demonstrated (c.f. Thorell Citation2017), our interpretation of the activities offered points to that preschool children are considered to be competent to participate in riding activities from a very young age. The exploration of the websites demonstrated that some riding schools offered activities to children from birth (0 years) (). However, it is most common for riding schools to offer activities for children between the ages of three and five (75% of the riding schools with activities for preschool children were aiming their activities at that age group).

Figure 1. Proportion (%) of riding schools offering activities from a specific age between 0–6 years. Riding schools within the Swedish Equestrian Federation (N = 198).

Source: See . *Riding schools offering activities for all ages are included in this category. **Riding schools offering activities from” when they can walk” are included in this category.

Learning through play

The learning environment in the horse-riding school in the activities for young children is not primarily framed by a military discourse in which orders are given. Instead it is framed by ideas about how young children learn in different ways from older children or adults. The interviewees indicate that the activities are both important and fun. According to them, participating in preschool riding activities brings joy and satisfaction to the preschool child, who also develops the ability to concentrate and perform multiple tasks such as riding, grooming, and communicating.Footnote2 One of them emphasizes that:

…the most valuable thing about this activity is the joy of the children, that they think it is fun and that it gives them a lot. (Riding school Horse)

Riding schools, with some exceptions, use fairy tales and stories to engage and involve the children as well as to encourage learning and enjoyment. The instructor uses show-jumping equipment, water mats, and flowerpots as props and tells stories about the jungle and the forest. For example, the children may be allowed to ride across an imagined bridge over a river with crocodiles. This exercise requires the child to draw their feet up, thus training their balance. In another exercise, the children ride over fallen ‘palm trees’ (bars), again training their balance. Other instructors use a mascot that shows up in both the riding and theory lessons giving the children tasks to solve. Themes, such as using magic (tricks, forests, or paths among animals and trolls), imagined settings (zoos, amusement parks, carousels), or children’s literature are used in the activities and these are meant to integrate play and learning. One of the interviewees expresses it thus:

The riding lessons are based on steering exercises using bars and cones. The children also perform WE (working equitation, authors’ note) exercises moving mugs and lifting water pitchers. The instructor uses show jumping equipment, water mats and flowerpots, to create stories about a jungle. At the same time, she asks the children about which animals they can find in the jungle. They do the same thing with the forest. They ride over a bridge and there are crocodiles in the river, so you have to pull your feet up. Sometimes they ride over ‘fallen trees’. Most of the lessons are based on balance exercises. (Riding school Horse)

Evidently, play is seen as a tool for education. In addition to riding, the preschool children are offered ‘theory classes’. Theory is considered important and conveys horse and stable knowledge to the children in a playful format. The interviewees underline that children should learn how to socialize with horses in a positive, relaxed, and playful way. The classes can include drawing horses or learning about coat colors and equipment through crafts or drawing, and arrangement of treasure hunts or quiz walks with questions about equine feed, equipment, and behavior. Some interviewees mention that they use a ‘magic theme’ during theory classes. They conjure equipment such as grooming brushes from ‘magic’ bags, while teaching the children the names of the brushes. These brushes are then placed in the riding hall or paddock on cones and the children are taught riding patterns in the hall by remembering the names of the brushes. Others let the children run the riding patterns on foot and play horse during theory classes.

Children’s bodies and minds as restrictions for the activities

The social construction the competent child is conditional. The interviewees state that teaching the younger children can be problematic, noting that the biological body and mind of the preschool child poses a challenge. One interviewee contends:

It is a challenge to have lessons with six-year-olds as they quickly lose focus. Therefore, we have decided not to welcome the younger ones as it is simply not possible to prepare the activities in a good way for the six-year-olds. (Riding school Hoof)

The interviewees describe how they adapt the activities, underlining that each exercise is shorter than for older age groups (as the preschool children must be able to concentrate) and that they use images instead of letters when marking positions in the riding hall or paddock.

The interviewees are somewhat critical of the activities for preschool children. They stress that it is important for activities to be organized properly. One of our interviewees observes:

We think that children who are under seven years often do not have the ability to follow instructions and especially not in a group. As a result, group instruction works poorly and can even be dangerous. Therefore, it is important for us to offer an alternative for the younger children that is more adapted to that age category. (Riding school Stable)

According to the interviewees, the activities for preschool children mainly entail riding at a walk or trot. The children practice steering, and balance exercises are emphasized. Some interviewees observe that children of two to three years lack sufficient motor skills, coordination, and balance to be able to ride at a trot without slipping off the horse, requiring someone on the ground to hold the child in place while the horse is trotting. The children ride both outside and inside, but the interviewees state that it is difficult to keep the content indoors sufficiently varied so that the children are not bored. However, interviewees emphasize that the children do not jump or canter because small children’s heads are too heavy in relation to their bodies.

Even though the activities for the preschool children are problematized, the interviewees consider the activities for preschool children a good preparation for participating in regular stable and riding activities from the age of seven. The interviewees claim that regular activities function better when the children are already familiar with the routines and the horses. In other words, learning to handle the horses—rather than riding itself—is stressed as important for preschoolers. One of the interviewees says:

There is a huge difference between those who have participated in the preschool riding activities and those who come as beginners (when they are older) to a regular riding group. Those who have participated before are much more prepared and learn how to ride in a completely different way and they are well aware of the (stable) environment and know the routines. (Riding school Hoof)

Put differently, the young (preschool) riders are seen as becoming riders while their bodies seem to hinder them from being riders in the same way as children of seven years and older. The interviewees’ perceptions of the biological body and mind of the (preschool) child sets a frame for the activities. They seem to suggest that these children require different treatment than older children and adults, possibly indicating that the younger children are not (as) capable of following instructions as the older age groups. The bodies of these groups are not described as hindering activities. This is interesting as an older body could—potentially—be conceived as stiffer or regarded as problematic when it comes to learning certain movements in other areas. It is, however, specifically the body and mind of the preschool child that are seen as restrictions.

The vulnerable body

The construction of the competent child is questioned in relation to the safety discourse too. Safety aspects were seen as central to the activities for preschool children and covered aspects such as safe horses, a safe environment, safety equipment, safe behavior in the equestrian context, and the fact that parents or other adults accompany and help the child. The interviewees underline that they rely on the military tradition for safety rules and procedures. This may be seen as a contradiction to how they organize riding lessons and learning through play. The contradicting ideas point to a complex construction of the riding child. Nevertheless, the emphasis on safety indicates another aspect of the preschool rider as socially constructed—the vulnerable body.

All interviewees emphasize that the children must wear a helmet when riding as well as in the stable. Some also require that siblings wear helmets when they are in the stable (i.e. even if they are not riding). Most of the riding schools have helmets and the children can borrow one during the activity. In other rare cases, the children have to bring their own helmets. The interviewees observe that it is a challenge to find enough helmets to fit the smallest children. Once again, this exemplifies how the biological body of the preschool child is seen as a hindrance to the activities.

In terms of safety vest usage, experiences and opinions differ. Vests are available at many riding schools but are not compulsory, although several riding schools recommend them. Interviewees note problems with the safety vests and state that:

…(safety) vests are a problem and there are no vests for the small riders (Riding school manager at Riding school Canter)

The vest is also considered a challenge as it causes the small riders to bounce in the saddle. Another problem is that the children find the vests uncomfortable and do not want to wear them. In other cases, interviewees have observed that the vest provides a false sense of security and that the children believe that they will fall off if they do not have the vest. Some of the interviewees believe that the children develop a more natural sense of balance without a vest.

In addition to helmets and vests that are available at nearly all riding schools, children can according to some interviewees, borrow gloves, shoes, boots, and half chaps. The respondents underline that wearing the right kind of boots, or shoes and half chaps, is important for safety reasons, and they emphasize that they lend such equipment to reduce the risk of the children getting caught in the stirrups if they fall off.

All interviewees recommend which also are underlined at many websites, that the children wear heeled shoes, noting at the same time that the youngest children (especially in cold weather) often wear shoes without adequate heels. The children are still allowed to ride, but the person who leads the class will then pay closer attention trying to prevent the children to get caught in the stirrups.

The incompetent adult

In order to understand the activities for preschool children offered at the riding schools it is important to study how other relevant groups in the stable are perceived and how these groups are seen in relation to the young rider (c.f. Alanen Citation2001). Help from parents or accompanying adults is essential for the activities and for ensuring safety. Accompanying adults hold the horses, lift the children into the saddle, assist with grooming the horse in places where the children cannot reach, and help the children to find their balance while riding. The riding schools cannot afford to keep staff for this purpose and cannot rely on older pupils at the riding school to do it unpaid. They therefore depend on others to enable and facilitate the activity. The dependence on parents or other accompanying adults is, however, not unproblematic. One of the interviewees states:

It is required that a relative accompany the child and hold the horse. We also offer an introduction to the parents when the children begin. It is a challenge with those parents who are not horse-skilled they require more help than those who already know a little. It can take a lot of the instructors’ time. (Riding school Helmet)

The interviewees express that it can be risky to rely on parents and our interpretation suggests that newcomers to the stable are perceived as incompetent (in this context)—regardless of age. According to the interviewees, the riding children as well as parents and siblings need to learn the rules of the stable. As described above, the military tradition provides the stable and riding context with safety rules and procedures such as not running in the stable, how to enter the horse’s box, that children are not allowed to enter stalls or boxes without a riding instructor in sight, as well as how to sidewalk the horse safely with a leading rope, keep a safe distance in the stable and when side walking to and from the riding hall or riding lesson, put the horses in the designated place in the stable, walk in a particular order, not start riding before being called by the riding instructor, and mount with a safe distance between horses on the central line in the hall. Therefore, the riding instructor must carefully supervise the children so that, for example, no one disappears behind a horse.

The interviewees stress the importance of accompanying siblings and parents learning safe behavior at an early stage. One example of this, already mentioned above, is that accompanying siblings must wear helmets in the stable. Several interviewees state that they have experienced problems with siblings and parents not knowing how to behave in a stable—running in the stable behind the horses and slamming doors. Other examples of acts that may scare the horses (and make an activity unsafe) are parents who come to watch the riding lesson and stomp their feet in the stands to get the snow off their shoes, or who bring strollers into the stable or riding hall. One interviewee indicates another safety problem related to parents pushing their children, stating that:

Unfortunately, parents often push their children and want them to perform even if they just started riding and are very young, they want them to canter after two months. (Riding school Tail)

The competent youth leader

Existing research has suggested that experience and knowledge matter more than age for the construction of positions of power in the stable. A previous study demonstrates that beginners—both children and adults—are seen as in need of help (incompetent) (Forsberg Citation2012). In contrast to many other contexts where adults are ascribed positions of power, the horse-riding school offers such positions to young people. A similar pattern can be seen in our source material. The interviewees express that they are dependent on so-called youth leaders in the activities for young children since, as described above, it is not enough with only one instructor in a group with preschool riders. The importance of the youth leader can also be seen more generally in the horse-riding school system. The Swedish Equestrian Federation has developed an educational program for non-salaried leaders in equestrian sports that starts from an early age. The Youth Leader course is a leadership training course offered to young equestrians from the age of 15 (SvRF Citation2019). The course aims to convey basic knowledge of pedagogy, methodology, and leadership. Young people at riding schools are often engaged in leading theory classes for younger children or organizing club competitions and other activities (SvRF Citation2019).

The interviewees affirm the importance of the younger children learning from teenagers. A young person can be assigned as a horse-riding school host and assist in activities with preschool children. One of the interviewees stated:

There are usually two or three youth leaders leading the classes. They help each other and it has worked well since even scared parents or parents who are not used (to horses) can get more help than if there had been a lone instructor. All the instructors at the riding school, including these youth leaders, work on a voluntary basis and do not get paid. (Riding school Hoof)

However, the answers are complex. Some interviewees emphasize that riding instructors with educational training are used in activities for younger children. Some riding schools even hire preschool teachers with an equestrian background and educational developers for these activities and observe that the new riding instructors lack competence in instructing children.

There is a need for more ‘child competence’ in equine studies education and there is also a need for further education in ‘child competence’ for existing instructors and equestrian teachers. (Riding school Helmet)

The interviewees emphasize that preschoolers are a difficult group to teach as they impose requirements on the equestrian teacher’s skills and that it is not enough to use equestrian instructors with level 1 and 2 or persons with a youth leader educationFootnote3:

Riding teachers educated in the equine studies program are not enough, trained educators are needed. (Riding school Stable)

The competence of the youth leader is highlighted. However, the youth leader’s capabilities are problematized also, and it is stressed that this group needs further training. Nonetheless, the youth leaders are most often socially constructed as sufficiently competent to lead the younger children. According to Forsberg, young women develop competencies in the stable that are not only useful within equestrian sports. The girls exert power over the horses and other young people and their drive to act and lead in the stable creates meaning (Forsberg Citation2012).

The competent horse

Horses are central to the riding school activities, and are seen as competent co-workers. However, not all horses can work with the young children. The interviewees talked about their experiences of using of horses. Riding schools use different kinds of horses and reason differently regarding horse suitability. Shetland ponies, as well as ponies of other sizes, Icelandic horses, Fjord horses, and small warm-blooded horses are used in the activities. The size of the horse was claimed to have no direct significance, with some exceptions. Instead, the horse’s experience, stability of temperament, safety, and ability to carry young children were seen as crucial. The horse’s age seems to matter more than size and breed. Older horses, ‘faithful servants’, are used. According to the respondents, the horses need years of training to take part in the activities and newer horses learn from the old ones (the average age of horses used in these activities is 20 to 28 years). Some of the interviewees underline that Shetland ponies are more patient and suitable for repetitive movements. At the same time, they are seen as stubborn or willful. Others claimed that Welsh ponies are suitable as their backs are narrower, and they are therefore easier for a small child to straddle.

Furthermore, the interviewees emphasized the importance of the horses being allowed to engage in ‘natural behavior’, including a lot of time spent outside and in a herd. Many of the riding schools in this study use free-range stabling and the interviewees believe that the horses are more harmonious, less stressed, and have less excess energy as a result. In addition, the horses are presented as liking being groomed and ridden after coming inside. The interviewees stressed that the horses needed varied training. All of them told us that they long-rein the horses and, if possible, let the older riders train the horses in various ways. The supply of suitable horses is described as good, with some exceptions, but the riding schools employees must train, school, and adapt the horses to suit the activities. It is possible to buy horses who already have the requisite schooling, but the price is often too high for riding schools, which have limited finances to buy them.

Conclusion: competent child and (in)competent others

The aim of this article is to increase the understanding of riding school activities for preschool children. The analysis indicates that the activities are framed by ideas about the preschool child, parents, youth leaders, and horses. Our first research question concerned whether the idea of the competent child was present in the design of young children’s riding activities and the study demonstrates that this is the case. The social construction of the preschool rider can be related to the discourse of the competent child (Samuelsson Pramling and Carlsson Asplund Citation2003; Brembeck, Johansson, and Kampmann Citation2008; Månsson Citation2008). A majority of the Swedish riding schools (under the umbrella of the Swedish Equestrian Federation) offer activities for preschool children and perceive them as sufficiently competent to participate (Riding kindergarten and Tiny trots riding 54% and other 10% in all 64%). Children are welcomed to the riding school from a very young age and are perceived as active agents who can explore equestrian activities in different ways. Notions of the preschool rider include their ability and opportunity to learn and that preschool children should learn through play (in contrast to other groups in the horse-riding school). The learning environment is not guided by the military discourse of giving orders. The military order is, however, present in the safety precautions; rules and procedures.

However, the idea of the competent child is complex and contradicting, and the child is seen as both competent and as incompetent in the sense of being restricted by the biological body and mind. The smallness of the body is seen as a challenge, as is the size of the head in relation to the rest of the body. In addition, the children’s ability to balance their bodies on horseback is questioned. Perceptions about the biological body of the preschool child have consequences for how riding is taught and contrast with what appear to be underlying ideas about the contents of regular riding school activities. Riding lessons for preschool children are shorter, more varied, and include a stronger element of play—far from the military discipline showed in riding lessons for other groups (c.f. Thorell Citation2017). Furthermore, it is incompatible with the fostering for competition or the fostering of democratic values seen in other sports activities (SOU Citation2008:59). It is, however, worth noting that the person leading the activity still seems to decide what to include.

Ideas about the preschool rider also include perceptions of the vulnerable body. In other words, small children are seen as in need of special protection. Riding with helmets is compulsory at the riding schools, and young children are supposed to wear helmets in the stable. Sometimes accompanying adults and siblings are advised to wear helmets as well. Another piece of safety equipment is the safety vest. The interviewees’ opinions of vests diverge—some like them, some do not. According to the interviewees, vests provide a false sense of safety, hinder the children’s development of their balance, and cause the children to bounce in the saddle. Regardless of opinion, the arguments presented are based on perceptions of the biological and vulnerable body. The young rider is socially constructed in in relation to other relevant groups in the horse-riding school. The preschool children need help from accompanying adults when riding or taking care of the horse. The discourse on the accompanying adults is complex and suggests that this group is perceived as problematic and possibly incompetent. In most children’s sports, accompanying adults play an important role as leaders, coaches, financial guarantees, and in transporting their children to and from the activities. In the riding school, the accompanying adults are expected to be active by helping to take care of the horse before and after riding, lifting the child into the saddle and, sometimes, holding the child in the saddle and leading the horse during the riding lesson. The interviewees, however, observe that many parents are not sufficiently competent to perform these chores in the stable. Some of them lack knowledge of horses and endanger the activities through their behaviour. Other parents are perceived as pushing their children too hard, striving to make them skilled riders too quickly.

The incompetent adult is constructed in contrast to competent horses and youth leaders in the stable. The latter have a unique role in that they are perceived as more competent than adults. The horses are perceived as competent (together with the youth leaders). They are not seen as machines or tools (Zetterqvist Blokhuis Citation2019), and there are several prerequisites for becoming a horse that is suitable for preschool riders, such as high age, level of schooling and smallness. Yet, the size is not considered to be of primary importance. Instead, these horses are described as faithful servants, a description that indicates the importance of understanding the horses as co-workers in the riding school (c.f. Coulter Citation2016).

At the beginning of this article, we posed questions about whether the preschool children were perceived as (human) beings or becomings. The answer is multifaceted. A central idea is that the activities prepare the younger children for what they will do later at the riding school. The age of seven appears to be seen as transitional; at this point, the children are seen as different from the younger children and are perceived as big or old enough to partake in regular riding activities (which are, supposedly, organized differently). However, the younger children are competent in the given context. They can ride horses and the activities are organized so that they can participate. In the adapted activities, the preschool children are perceived as riding beings. However, it is debatable whether they are ascribed agency and the possibility to negotiate in the way a fully competent child has (Brembeck, Johansson, and Kampmann Citation2008). Riding school managers and instructors form educational plans for the activities based on their perceptions of the preschool child. There are many ‘childified’ equestrian activities adapted to perceptions of the preschool children. Nonetheless, the social construction of the young rider seems more strongly connected to a becoming rider than a being rider. The interviewees underline that these activities prepare the young children for regular riding. Riding activities for preschool children are primarily about shaping, nurturing, and ensuring that children understand the stable culture, and preparing and enabling the child to ‘become’ a rider who will fit into regular riding lessons when the time comes.

An interesting finding of the study is that there is no simple connection between adults and being. As Lee has suggested, there are no complete, autonomous, and independent individuals (Lee Citation2001). Adults (as well as children) are becomings in the horse-riding school—and they have an opportunity to develop into horsey people—if they follow the instructions for the riding school activities. In the riding school there are two groups that are perceived as beings—the youth leaders and the horses. Youth leaders and horses cooperate and are given agency in these activities in contrast to the young rider and the accompanying adult. Furthermore, the child—the becoming rider—is not constructed in terms of generationing in opposition to the adult as Alanen suggests (Alanen Citation2001), but rather in opposition to the competent youth leader and the competent horse.

The_Competent_Child_Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (18.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The length of the activities and cost was also noted, but these results will not be presented in this article.

2 One of the interviewees underlines that riding activities bring joy to all children, but are especially important for children with disabilities. These children gain a sense of security when riding, feeling satisfaction when they are challenged and find they are able to partake in the group, handle the required tasks, and be brave.

3 There are three degrees of equestrian instructor competence, Level 1 to 3, and are passed through vocational exams after training or through professional experience. The "Level" system is founded on an international system developed by the International Group for Equestrian Qualifications (IGEQ), an organization that works for an international standard of education levels in equestrian sports. https://igeq.org/

References

- Alanen, Leena. 2001. “Explorations in Generational Analysis.” In Conceptualizing Child-Adult Relations, edited by Leena Alanen and Berry Mayall. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Brembeck, Helene, Barbro Johansson, and Jan Kampmann. 2008. “Beyond the Competent Child.” In Beyond the Competent Child. Exploring Contemporary Childhoods in the Nordic Welfare Societies, edited by Helene Brembeck, Barbro Johansson and Jan Kampmann. Roskilde: Roskilde University Press.

- Corsaro, William A. 2005. The Sociology of Childhood. London: Pine Forge Press.

- Coulter, Kendra. 2016. Animals, Work, and the Promise of Interspecies Solidarity. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fasting, Kari, Celia Brackenridge, and Gustav Kjölberg. 2013. “Using Court Reports to Enhance Knowledge of Sexual Abuse in Sport: A Norweigan Case Study.” Scandinavian Sport Studies Forum 4: 49–67.

- Flemmen, Asbjörn. 1987. Skileik [Play on Skis]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Forsberg, Lena. 2012. “Manegen är krattad – Om flickors och kvinnors företagsamhet i hästrelaterade verksamheter [The Stage is set – On Girls’ and Women’s Enterprising in Horse-Related Activities].” Doctoral Thesis. Luleå tekniska universitet, Institutionen för ekonomi, teknik och samhälle, Innovation och Design.

- Gorard, Stephen, and Kyriaki Makopoulou. 2012. “Is Mixed Methods the Natural Approach to Research?” In Research Methods in Physical Education and Sporty, edited by Kathleen Armour and Doune Macdonald. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harlow, Meghan, and Jessica Fraser-Thomas. 2019. “Toddler and Preschooler Sport Participation: Take-up, Pathways, and Patterns of Engagement.” Sport Psychology 51 (1).

- Hedenborg, Susanna. 2006. “Barnarbete, barns arbete eller hobby? Stallarbete i [Child Labor, Children’s Work or a Hobby? Stable Work in a Generational Perspective].” Historisk Tidskrift 126 (1): 47–68.

- Hedenborg, Susanna. 2009. “Till vad fostrar ridsporten? En studie av ridsportens utbildningar med utgångspunkt i begreppen tävlingsfostran, föreningsfostran och omvårdnadsfostran [A Study of Equestrian Education in Sweden].” Educare 1: 61–78.

- Hedenborg, Susanna. 2012. “Den som i leken går…. Barnperspektiv på idrotten med fokus på arbete.” In För barnets bästa: En antologi om idrott ur ett barnrättsperspektiv [for the Best Interests of the Child: An Anthology about Sports from a Children’s Rights Perspective], edited by Johan Norberg. Centrum för Idrottsforskning. Stockholm: SISU Idrottsböcker.

- Hedenborg, Susanna. 2013. Hästkarlar, hästtjejer, hästälskare: 100 år med Svenska ridsportförbundet [Horsemen, Horsegirls and Horse Lovers: The Swedish Equestrian Federation 100 Years]. Strömsholm: Svenska Ridsportförbundet.

- Hedenborg, Susanna, and Kristin Fransson. 2011. “Barn och idrott.” In Utbildningsvetenskap för grundskolans tidiga år [Educational Science for the Early Years of Compulsory School], edited by Sven Persson and Bim Riddersporre. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Hedenborg, Susanna. 2007. “The Popular Horse: From Army and Agriculture to Leisure.” www.idrottsforum.org.

- Hendrick, Harry. 1997. Children, Childhood and English Society, 1880-1990. Vol. 32 of New Studies in Economic and Social History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- James, Allison. 2007. “Giving Voice to Children´s Voices: practices and Problems, Pitfalls and Potentials.” American Anthropologist 109 (2): 261–272. doi:10.1525/aa.2007.109.2.261.

- James, Allison, and Adrian James. 2004. Constructing Childhood: Theory, Policy and Social Practice. New York: Palgrave.

- James, Allison, and Adrian James. 2012. Key Concepts in Childhood Studies, 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage.

- James, Allison, and Alan Prout. 2014. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood – Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Jensen, Maybritt, and Heid Osnes. 2009. Kroppen i lek og learing [The Body in Play and Learning]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Kingdon, Zenna. 2018. “Young Children as Beings, Becomings, Having Beens: An Integrated Approach to Role-Play.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (4): 354–368. doi:10.1080/09669760.2018.1524325.

- Lancy, David F. 2012. “Unmasking Children´s Agency.” AnthropoChildren 2: 1–20.

- Lee, Nick. 2001. Childhood and Society: Growing up in a an Age of Uncertainty. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

- Månsson, Annika. 2008. “ The Construction of ‘the Competent Child’ and Early Childhood Care: Values Education among the Youngest Children in a Nursery School.” Educare 3: 21–41.

- Norberg, Johan, and Karin Redelius. 2013. “Idrotten och kommersen: marknaden som hot eller möjlighet? [Sports and the Commerce: The Market as a Threat or an Opportunity?].” In Civilsamhället i samhällskontraktet : en antologi om vad som står på spel [Civil Society in the Social Contract: An Anthology on What is at Stake], edited by Filip Wijkström, 175–194. Stockholm: European Civil Society Press.

- Prout, Alan. 2005. The Future of Childhood: Towards the Interdisciplinary Study of Children. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Prout, Alan, and Allison James. 1997. “A New Paradigm for the Sociology of Childhood? Provenance, Promise and Problems.” In Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood, edited by Allison James and Alan Prout, 7–32, 2nd ed. London: Falmer Press.

- Qvotrup, Jens. 2009. “Childhood as a Structural Form.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies edited by Jens Qvotrup, William F. Corsaro, Michael-Sebastian Honig. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Redelius, Karin. 2011. “Idrottens barn – fria från kränkningar? En internationell utblick om idrott och FN:s barnkonvention.” In För barnets bästa: En antologi om idrott ur ett barnrättsperspektiv [for the Best Interests of the Child: An Anthology about Sports from a Children’s Rights Perspective]. Centrum för Idrottsforskning. Stockholm: SISU Idrottsböcker.

- Samuelsson Pramling, Ingrid, and Maj Carlsson Asplund. 2003. Det lekande lärande barnet i en utvecklingspedagogisk teori [the Playful Learning Child in a Developmental Pedagogical Theory]. Stockholm: Liber.

- Smith, Elin. 2009. “The Sport of Governance – A Study Comparing Swedish Riding Schools.” European Sport Management Quarterly 9 (2): 163–186. doi:10.1080/16184740802571435.

- Söderlind, Ingrid, and Kristina Engwall. 2005. ““Var kommer barnen in?” Barn i politik, vetenskap och dagspress [Children in Politics, Science and Daily Press].” Institutet för Framtidsstudiers skriftserie: Framtidsstudier nr 15.

- Solenes, Oskar, and Susanna Hedenborg. Forthcoming.

- Sörensen, Thomas. 1997. “Det blänkande eländet: en bok om Kronprinsens husarer i sekelskiftets Malmö [The Glittering Misery: A Book about the Crown Prince’s Hussars in Turn-of-the-Century Malmö].” Doctoral thesis. Lunds Universitet.

- SOU. 2008:59. “Föreningsfostran och tävlingsfostran – En utvärdering av statens stöd till idrotten [Association Education and Competition Education – An Evaluation of State Support for Sports].” Socialdepartementet, Stockholm.

- Spyrou, Spyros. 2011. “The Limits of Children’s Voices: From Authenticity to Critical, Reflexive Representation.” Childhood 18 (2): 151–165. doi:10.1177/0907568210387834.

- Spyrou, Spyros. 2016. “Researching Children´s Silences: Exploring the Fullness of Voice in Childhood Research.” Childhood – A Global Journal in Child Research 23 (1): 7–21. doi:10.1177/0907568215571618.

- Ståhlberg, Ulla. 1996. Att lära barn rida [Teaching Children how to Ride]. Svenska Ridsportförbundet.

- SvRF. 2019. “Youth Leader Course. Swedish Equestrian Federation.” www.ridsport.se/Utbildning/Ledarutbildning/Ungdomsledare/.

- Thedin Jakobsson, Britta. 2013. “Därför vill vi fortsätta” om glädje, tävling och idrottsidentitet. Spela vidare – En antologi om vad som får unga att fortsätta idrotta [Keep playing – An Anthology about What Gets Young People to Continue with Sports.” Centrum för idrottsforskning 2013(2).

- Thorell, Gabriella. 2017. “Framåt marsch! Ridlärarrollen från dåtid till samtid med perspektiv på framtid [Forward March! the Role of the Riding Instructor – Past, Present, Future]” Gothenburg Studies in Educational Sciences 397. Doctoral thesis. Göteborgs universitet.

- Thorell, Gabriella, Christian Augustsson, Owe Stråhlman, and Karin Morgan. 2017. “The Swedish Riding School: A Social Arena for Young Riders.” Sport in Society – Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 21 (2): 1–16.

- Thorell, Gabriella, and Susanna Hedenborg. 2015. “Riding Instructors, Gender, Militarism, and Stable Culture in Sweden: Continuity and Change in the Twentieth Century.” The International Journal of the History of Sport 32 (5): 650–666. doi:10.1080/09523367.2015.1021337.

- Trondman, Mats. 2011. “Ett idrottspolitiskt dilemma – unga, föreningsidrotten och delaktigheten [A sports political dilemma – young people, association sport and participation].” Centrum För Idrottsforskning 2011:3.

- Zetterqvist Blokhuis, Mari. 2019. “Interaction between Rider, Horse and Equestrian Trainer: A Challenging Puzzle.” Södertörns högskola, Doctoral thesis. Huddinge: Södertörns högskola, 39–40.