Abstract

More women are successfully combining their elite athletic careers with motherhood, however for many, pregnancy and motherhood are often one of the main reasons they end their sporting careers. While there has been some focus in recent years regarding this topic, there are limited reviews of the literature regarding the experiences of elite athletes with pregnancy and motherhood. Adopting a Scoping Review approach, we reviewed 40 studies exploring motherhood and elite sport. Overall, the studies analysed for this scoping review provide a mixed picture of the biomedical and social aspects related to female elite athletes and pregnancy. The bio-medically focused studies tended to adopt a quantitative or mixed-method perspective with a predominant focus on physical changes, injuries, and performance outcomes, whilst reviewed qualitative studies focused on a variety of social factors that can impact a female athlete’s return to elite sport including childcare and access to maternity leave.

Introduction

Historically, societal discourses and norms have influenced female athletes’ decisions regarding pregnancy and motherhood, due to concerns of interruptions to sporting careers (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022). However, in recent times, there has been a shift in media and societal discourses concerning mothering elite female athletes (McGannon et al. Citation2017). Successful postpartum comebacks to elite sports by several prominent athletes provide a timely entry point for further investigation (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022; Darroch et al. Citation2022; Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2014, 2015, Citation2017; McGannon et al. Citation2015, Citation2019, Citation2022).

Female athletes often face conflicting information regarding the safety and injury risks associated with elite sports training during pregnancy- and post-partum periods (Jackson et al. Citation2022; Bø et al. Citation2017a). Existing evidence-based physical activity guidelines are often not tailed to the specific needs and considerations of pregnant or post-partum elite athletes, leading to uncertainty and concerns among athletes (Wowdzia et al. Citation2020). The lack of specific guidelines for elite athletes during pregnancy and postpartum creates an assumed level of risk for an athlete if they train above the general recommendations. As a result, many athletes express concerns about their exercising during pregnancy, fearing it may increase their risk of having pregnancy complications (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020).

Elite-level athletes heavily rely on corporate sponsors, sporting corporations and athletic governing bodies to fund and support their athletic endeavours (Darroch et al. Citation2019). In return athletes endorse these companies and governing bodies by exclusively wearing sponsored gear, appearing in advertisements, posting on social media, and attending company-sponsored events/races as representatives (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022). However, existing literature suggests a lack of proactive measures and accommodations for female athletes transiting into motherhood (Darroch et al. Citation2019; Massey and Whitehead Citation2022).

Furthermore, mothering athletes face additional pressure from societal expectations regarding motherhood and the challenges of balancing elite athlete training with their maternal roles (Davenport et al. Citation2023). Female athletes have described a prevailing societal narrative that suggests women must choose between being an elite athlete or starting a family (Davenport et al. Citation2023).

A preliminary search of Medline and Embase identified four literature reviews related to the topic of pregnancy, parenting experiences and athletics (Kimber et al. Citation2021; L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Scott et al. Citation2022; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020). Three of the literature reviews predominately focused on a biomedical perspective surrounding elite-athletes pregnancies (Kimber et al. Citation2021, L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020) comparatively Scott et al. (Citation2022) literature review focused on the corporate sponsor’s perspectives of motherhood While these reviews provide some understanding regarding pregnancy and elite athletics, it can be argued they are also limited due to only focusing on specific areas concerning the topic. Thus, this paper will focus on a more varied summary of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method papers regarding pregnancy and motherhood experiences with elite athletes. A scoping review process was adopted due to the exploratory nature of the topic and to enable the synthesis of a wide range of literature (Cooper et al. Citation2021). The aims of this scoping review are the following:

to provide an overview of what is known regarding elite athletes experiences with pregnancy and motherhood

to highlight current knowledge gaps and potential research priorities in the pregnancy and motherhood elite athlete domain

Methods

Scoping reviews use rigorous and transparent methods to succinctly identify and analyse all the relevant literature addressing the relevant research question (Pham et al. Citation2014). Scoping reviews seek to investigate what is known about a topic within the literature (Cooper et al. Citation2021). A scoping review of a body of literature can be particularly useful when the topic has not been extensively reviewed or is an emerging topic area, as such the topic of this study (Pham et al. Citation2014). As such we the researchers, found a scoping review to be suitable due to the exploratory nature of this topic and to help to capture the diverse and unique range of perspectives and findings with regards to pregnancy and motherhood among elite athletes. As we the researchers, see pregnancy and motherhood as a diverse and unique experience for all athletes, and do not seek to generalise, but portray the diverse range of perspectives and findings of this topic.

In this review, we followed the methodological framework in accordance with the Johanna Briggs Institute Methodology (JBI) for scoping review (Peters et al. Citation2020). While not without critiques (Khalil et al. Citation2020) the JBI method of reviews has been used extensively (Parker et al. Citation2022; Garti et al. Citation2021; Oliveira et al. Citation2021) and was used as a well-accepted comprehensive approach to the conducting and reporting of scoping reviews. The scoping review began in October 2022 and took approximately seven months to complete. The core JBI seven steps were followed: (1) define a clear review objective and questions; (2) apply the PCC framework; (3) develop a protocol; (4) conduct systematic searches; (5) screen results for studies that meet your eligibility criteria. (6); extract and chart relevant data from the included studies; (7) write up the evidence to answer your question (Peters et al. Citation2020).

Review question

The PCC (Population, Concept and Context) mnemonic was used to construct a clear and meaningful title for the scoping review (Peters et al. Citation2020). The question, ‘What are the experiences [Concept] of elite female athletes [Population] concerning pregnancy and motherhood [Context]?’ guided and directed the development of specific inclusion criteria for this scoping review and provided a clear structure for the development of the scoping review report (Peters et al. Citation2020).

Participants

The participants included in this review are elite female athletes over the age of 18 years of age who must have a pregnancy or motherhood experiences either during the elite athlete career or their pregnancy or motherhood experience caused their retirement in elite sport. The participant exclusion criteria will be studies with participants under the age of 18, non-female, non-elite athletes and feature no experience of pregnancy or motherhood. For the purpose of this scoping review, we defined ‘Elite athletes’ as individuals who have competed at relevant national or international athletic competitions.

Determination of relevant studies

The databases searched were Ovid (Medline) and Scopus. Databases were searched for titles and abstracts that included at least one athletic/sports term and one pregnancy outcome term. Appropriate truncation symbols were used to account for search term variations. Common running terms were combined. Search terms and the full search syntax can be found in Appendix. This scoping review considered both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies. Systematic reviews that meet the inclusion criteria were considered, depending on the research question. Grey literature that encompassed the selection criteria and published Government reports were also considered. However no grey literature was found to encompass the selection criteria, thus we did not include any grey literature in this scoping review. Text and opinion papers were not considered for inclusion in this scoping review. indicates all inclusion and exclusion criteria adopted for this Scoping Review.

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Study selection

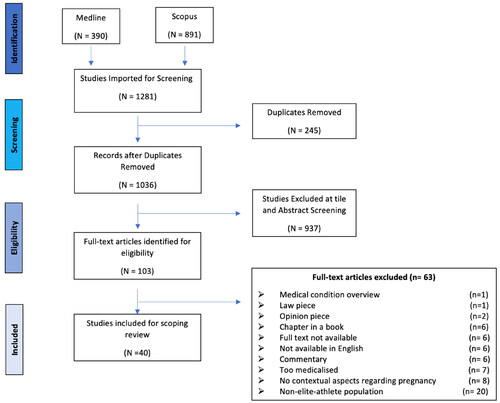

Covidence software was used to manage and streamline the process of abstract and full-text screening. Searches were conducted for papers published up to October 2022. All identified papers were uploaded to Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), and duplicates were automatically removed. Titles and abstracts were screened, with 100% cross-checked early in the process to assess agreement between authors. The full text was spilt up and reviewed by the four authors. From initial searches, 1281 articles were identified. After the removal of duplicates, 1037 were screened at the title and abstract stage, and 99 papers were retained for full-text assessment. Ultimately 40 papers met the inclusion criteria for this review. provides an overview of the study selection process. Reference lists of all included sources of evidence were screened for additional studies but no further studies were found to fit the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted from papers included in the scoping review by the team using a data extraction tool developed by the reviewers. The data extracted included author and year of publication, participants demographic information, study aim, study methodology/design, use of theory, sport, country, and key findings relevant to the research question.

Findings

General study characteristics

Although our search parameters had no time limits, no papers were identified before 2001. A total of 40 publications were identified between 2001 and 2022 Between 2001 and 2014 only thirteen papers were identified, while from 2014 to 2022 twenty-seven out of forty publications were found. Research publications came from thirteen different countries, with Canada (n = 14), USA (n = 6) and Norway (n = 5) being the most popular Some other countries appear more frequently than others, including Australia (n = 3), Spain (n = 3), and France (n = 2). There are 6 single-country publications (New Zealand, Denmark, Slovenia, Germany, Austria, and Iceland). The majority of the publications use a qualitative approach (n = 20), while the rest use either a mixed-method approach (n = 12) or a quantitative approach (n = 8).

Sixteen papers did not explicitly mention the sports in which the athletes being studied were involved. Among the remaining papers, fourteen focused on athletes from a singular sport, with distance running being the most featured sport in eight publications, followed by football which was discussed in two publications. Five papers focused on individual sports including rowing, cross-country skiing, track and field, tennis, and figure skating. In contrast, ten studies included participants from a variety of sports, which can be seen in . Overall, this study featured athletes with parenting experiences from 26 different sports were encompassed.

Table 2. Study Characteristics of the Reviewed Mixed Methods Studies.

Table 3. Study Characteristics of the Reviewed Quantitative Studies.

Table 4. Study Characteristics of the Reviewed Qualitative Studies.

Category 1: mixed-method studies

Mixed-method study characteristics

This scoping review identified twelve mixed-method studies. Of these twelve studies, three were conducted in Canada, two in the United Kingdom and one in the United States. Studies included were from 2011 to 2022. Bø et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018), produced a multi-part evidence statement, which was conducted by an international expert panel commissioned by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and published in the British Medicine Sport Journal. Bø et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018), has been cited separately in this section as each part of the evidence statement focused on different topics related to physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum. provides a summary overview of the mixed-method studies.

Mixed-method approach papers

The sample of all twelve studies (100%) included the experiences of pregnant or mothering elite athletes. The total number of participants for the mixed-method studies was 2866. Less than 1% of the sample was male. Forsyth et al. (Citation2023) had males in their sample, as the authors sought to understand the perceptions of players, coaches, and managers regarding the menstrual cycle, hormonal contraception, and pregnancy in women’s football.

A section of mixed-method designs (33%) were reviews of the literature predominantly related to recommendations for exercise training during pregnancy and outcomes of pregnancy for elite athletes (n = 3) and one explored how corporate sponsors frame the parenting experience of elite athletes (n = 1).

Two authors adopted a systematic review approach (n = 2) (Kimber et al. Citation2021; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020) and while two other authors adopted a review of the literature (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Scott et al. Citation2022). Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001) utilised a mix of qualitative descriptive and retrospective questionnaire methodology to explore the training patterns of athletes during pregnancy. Whilst Jackson et al. (Citation2022) did not explicitly state their research methodology. Bø et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018) were headed by the IOC, and they formed an international expert committee to review existing evidence on physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum. The committee released a five-part evidence statement that provided a review of the pertinent literature on pregnancy and physical activity for elite female athletes with a mixture of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods methodology papers (Bø et al. 2016). None of the reviewed papers identified a theoretical positioning for their study.

Mixed-method sports mentioned

Among the included mixed-method studies, nine out of twelve did not mention the sport/s being studied. For instance, Bø et al. (Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018) conducted a systematic review consisting of multiple parts but did not specify the sports featured in their reviews. Similarly, Jackson et al. (Citation2022), Kimber et al. (Citation2021) and L’Heveder et al. (Citation2022) and Scott et al. (Citation2022) included studies on various sports in their literature reviews, yet authors did not explicitly mention the specific sport/s they analysed.

In contrast to the previously mentioned studies, Wowdzia et al. (Citation2020) did specify the sports included in their systematic review. The authors mentioned that their study encompassed participants from athletics sports including 400-m sprint, football, handball, marathons, long-distance running, race walking, duathlon, cross-country skiing, CrossFit, ballroom dancing, swimming, track and field, and volleyball (Wowdzia et al. Citation2020). Likewise, Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001) focused on athletes participating in specific sports such as swimming, track and field, and running. Similarly, Forsyth et al. (Citation2023) centred their research on players, coaches and managers involved in football.

Mixed-method results

A total of 12 studies covered topics related to pregnancy and athletic performance. Themes related to the risk of injury in the postpartum period for elite athletes and the impact of pregnancy on post-pregnancy athletic performance. Three papers (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik Citation2001; Forsyth et al. Citation2023) explored social factors that can impact mothering athletes’ return to elite sports. Finally, authors Kimber et al. (Citation2021), Bø et al. (2016), Jackson et al. (Citation2022) and L’Heveder et al. (Citation2022) suggested elite athletes face a lack of quality evidence concerning training during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

Injury risk in the postpartum period for elite athletes

A key theme across the mixed-methods papers (Bø et al. Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2018; Kimber et al. Citation2021; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020) was related to the bio-medical risk factors and common injuries related to the return to sport in the postpartum period.

Wowdzia et al. (Citation2020) synthesised the current literature at the time in their meta and systematic review and concluded that elite athletes have a lower likelihood of experiencing pregnancy-related lower back pain compared to non-athletes. Similarly, Kimber et al. (Citation2021), conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis and reported there is extremely low evidence in the summarised literature suggesting that elite athletes who resume physical activity after the postpartum period may have an increased risk of injury compared to non-elite athletes.

However, it is worth noting the same authors Kimber et al. (Citation2021) also found a disproportionately high rate of sacral stress fracture in postpartum female elite athletes compared to the non-postpartum population. This finding was supported by Bø et al. (Citation2016a b; Citation2017a Citationb & Citation2018) who identified a potential increased risk for stress fractures in elite athletes during the postpartum period. Bø et al. (Citation2016a Citationb Citation2017a Citationb & Citation2018) suggested that this increased risk may be attributed to the reduction in bone marrow density due to calcium loss through breastfeeding.

Social factors impacting return to sport

Three of the reviewed papers (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik Citation2001; Forsyth et al. Citation2023) investigated social factors that could impact an elite athlete’s return to elite sport. These factors include access to childcare, loss of financial earnings and lack of sleep in the postpartum period, which can impact an elite athlete’s ability to train and recover (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001); Forsyth et al. Citation2023).

Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001) identified that 76% of their elite athlete participants who participated in swimming, track and field and running conveyed that lack of childcare was the biggest barrier to training in the postpartum period. Equally, Forsyth et al. (Citation2023) discovered that finances were a common barrier across countries for elite football players when returning to elite sports after pregnancy, primarily due to a lack of child support.

In the context of elite football, Forsyth et al. (Citation2023) highlighted childcare issues posed problems for team coaches’ during player selection. Coaches expressed uncertainty about players with children being able to find suitable childcare for games, which led them to be less likely to select these players (Forsyth et al. Citation2023).

These findings underscore the importance of addressing social factors such as childcare, and financial support to facilitate the successful return of elite athletes to their respective sports after pregnancy.

Impact of pregnancy on post-pregnancy athletic performance

Three mixed-method papers (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik Citation2001; Bø et al. Citation2018) contained findings related to the impact of pregnancy on post-pregnancy athletic performance.

L’Heveder et al. (Citation2022) discovered that women can maintain elevated levels of performance during pregnancy and can return to pre-pregnancy fitness levels after delivery. Similarly, Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001) discovered athletes who maintained moderate-to-high intensity exercise throughout pregnancy, saw a significant increase in maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max) at 12-20 wk postpartum, which was sustained until 36-40 wk after pregnancy Vo2max is a key determinant of elite performance in endurance sports (Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik Citation2001), making this significant improvement in vo2max post-pregnancy highly- promising for athletes.

Similarly, Bø et al. (2016e) found that women who consistently exercised at a moderate level during pregnancy can expect to see their vo2max to return to pre-pregnancy levels or even surpass them after delivery. Therefore, the literature suggests that elite athletes who sustain a level of activity throughout pregnancy can anticipate returning to their pre-pregnancy performance level or even experiencing improvement in their athletic performance after childbirth (Bø et al. 2016e; L’Heveder et al. Citation2022).

Lack of evidence

The mixed methods papers consistently highlight the lack of high-quality evidence regarding athletes’ return to elite sports during and after pregnancy. Kimber et al. (Citation2021), Bø et al. (Citation2016a Citationb; Citation2017a Citationb & Citation2018), Jackson et al. (Citation2022) and L’Heveder et al. (Citation2022) have all noted the insufficient high-quality evidence necessary to guide athletes safely during the postpartum period and with their return to sport.

Jackson et al. (Citation2022) further emphasized that the management of pregnant and postpartum elite athletes relies heavily on the experiences and input of support staff and athletes’ wider support team of medical professionals. This lack of a standardized approach to managing postpartum athletes contributes to the challenge of providing appropriate guidance (Jackson et al. Citation2022).

Similarly, women have not been encouraged to exercise in the postpartum (birth-6 wk) period due to concerns of injury (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Bø et al. Citation2016a Citationb, Citation2017a Citationb and Citation2018), however, the IOC recognised this is an arbitrary time point and that many elite athletes have successfully exercised within the first 6 wk and had no negative impacts related to injuries (Bø et al. 2016).

Moreover, L’Heveder et al. (Citation2022) highlighted the limited guidance available for healthcare professionals regarding the obstetric management of athletes, resulting in a conservative approach to postpartum management for elite athletes postpartum. Therefore, it can be concluded that the field of postpartum return to sports is a developing research area and requires further investigation to provide the necessary support and guidance for athletes to return to sports postpartum period safely and successfully.

Category 2: quantitative approach papers

Quantitative study characteristics

This scoping review identified eight quantitative studies related to the topic of elite female sportspeople and pregnancy. Of these eight studies, four were conducted in Norway, with one in Canada, Iceland, France, Australia, and the United States. The selected quantitative studies were published between 2007 and 2022. provides a summary overview of the quantitative studies.

Quantitative methodologies and sampling strategies

The total number of participants for the quantitative studies was 850. There were 652 elite athletes with pregnancy experiences (77%) and 198 participants were included as part of the control group (33%). All participants in the quantitative papers were female.

A case-control design was used by three studies (Franklin et al. Citation2017; Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019; Solli and Sandbakk Citation2018), while three studies applied a retrospective methodology (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007; Darroch et al. Citation2022; Forstmann et al. Citation2023). One study employed a controlled clinical trial methodology (Kardel Citation2005) and one utilized a cross-sectional design (Sundgot-Borgen et al. Citation2019).

Quantitative data collection tools

Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007), Darroch et al. (Citation2022), Franklin et al. (Citation2017), Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) and Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) employed a retrospective questionnaire as their chosen method for data collection. Forstmann et al. (Citation2023) conducted a retrospective analysis of previously published and publicly accessible data. Kardel (Citation2005) carried out a controlled clinical trial, and utilised various data collection tools such as physical tests, body weight and skin folds, bicycle ergometer and blood sampling, medical control, and heart rate registration. Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) and Franklin et al. (Citation2017) employed a retrospective case-control as the data collection tool. Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) utilized athlete’s training diaries and physiological testing as their data collection tool.

In the case of Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019), authors developed a questionnaire specifically related to pregnancy and return to training in the post-partum period, since no validated questionnaire was available at the time. Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) used the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire–Urinary Incontinence Short Form, which is a validated questionnaire, as one of their forms of data collection. Conversely, the questionnaires employed by Darroch et al. (Citation2022), Franklin et al. (Citation2017) and Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) were created by the authors and not undergone external validation.

Quantitative sports

All quantitative studies explicitly mention the sport/s being studied. Franklin et al. (Citation2017) focused on rowing athletes. Kardel (Citation2005) investigated the sports of biathlon, running and cycling. Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) examined athletes played football and handball. Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) provided a general distinction between high-impact and low-impact sports without specifying the sports. Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) centred their study around a single cross-country skier. Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) included a variety of sports such as endurance sports, ball-sports, aesthetic sports, weight class sports and technical sports. Finally. Darroch et al. (Citation2022) and Forstmann et al. (Citation2023) focused on distance running athletes. Overall, the quantitative studies encompassed a diverse range of sports.

Quantitative results

The eight quantitative studies covered topics related to pregnancy including physical changes and injury prevalence, birth outcomes for elite female athletes, post-pregnancy sports performance and information sources of exercise prescription.

Pregnancy physical changes and injury prevalence

A total of four studies discussed themes related to the physical changes and injury prevalence of elite athletes during pregnancy and postpartum periods (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007; Sundgot-Borgen et al. Citation2019; Darroch et al. Citation2022; Solli and Sandbakk Citation2018). The primary focus of these studies resolved around issues such as urinary incontinence, back pain, and injuries.

Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) conducted a retrospective analysis to investigate common conditions with elite athletes who played football and handball and matched controls. The findings suggest that elite athletes may experience urinary incontinence at various stages of pregnancy (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007). However, it is noteworthy that urinary incontinence is not exclusive to elite athlete, as the control in the study had a higher prevalence of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and at the 6-week postpartum period when compared to the elite athletes (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007). Surprisingly, only 15% of these elite athletes in the study engaged in pelvic floor muscles exercising during pregnancy, and 50% of them exercised the pelvic floor muscles in the 6-week postpartum period (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007).

In addition to investigating urinary incontinence, Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) also examined the prevalence of lower back pain amongst elite mothering athletes. Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) found that elite athletes had a lower prevalence of back pain (15%), compared to 28% of the control sample during their pregnancy.

Similarly, Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) compared elite athletes (EA) from a range of sports such as endurance sports, ball-sports, aesthetic sports, weight class sports and technical sports with active controls (C), with back-pain during different stages of pregnancy. In the first trimester, the prevalence of back pain was 0% among elite athletes, and 12% among controls. In the second trimester, back pain was prevalent amongst 12% of elite athletes, and 21% of the controls. Finally, in the third trimester, back pain was prevalent in 12% of elite athletes and 28% in the control group. Overall back pain was more prevalent in all three trimesters amongst the control group when compared to elite athletes.

Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) concluded acute injuries were not found to be a problem among elite athletes during pregnancy or postpartum. However, they did report that four out of thirty-four athletes reported stress fractures during the postpartum period. Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) proposed that these fractures might be attributed to several factors, such as a sudden increase in training load in early postpartum, insufficient strength training during pregnancy and early postpartum, histories of relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-s) or eating disorders (reported by two of these four athletes) and/or possible inadequate intake of calcium and vitamin D35 during pregnancy and the breastfeeding period.

Darroch et al. (Citation2022) found that fifty per cent of their elite female distance runners who experienced pregnancy reported an injury postpartum that delayed their return to running/competition. Darroch et al. (Citation2022) also found that higher-intensity running, compared with lower-intensity running, causes significantly greater mechanical strain and increased injury risk early in the postpartum period.

In a case study conducted by Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) on the most successful Winter Olympian competitor of all time, it was observed that the participant had a quick return to training after pregnancy and progressively increased training volume. However, during the 13–18-week period postpartum, a fracture in the sacrum was detected coinciding with a rapid increase in training load. Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) suggest this injury cause was likely too-rapid progression and a decrease in bone marrow density after delivery. Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) hypothesised that during the third trimester of pregnancy, there is a significant transfer of calcium to the foetal skeleton, along with a loss of calcium in breast milk (Sanz-Salvador et al. Citation2015). Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) suggest the mechanisms behind calcium transfer and bone turnover during pregnancy and lactating are only partially understood and there is a lack of knowledge regarding the effects of exercise on these factors. Consequently, Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) emphasize that pregnancy is likely a vulnerable period for the mother’s bones, which elite athletes should be mindful of.

Birth outcomes

Two studies conducted by Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) and Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) explored themes related to birth outcomes, including delivery outcomes and complications during childbirth. Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) conducted a retrospective case-control study to investigate delivery outcomes in first-time pregnant athletes participating in low-impact and high-impact sports, comparing them with non-athletes. The high-impact athletic group was defined as sporting activities that featured above-the-ground activities such as running and jumping and the low-impact athletic group was sports with one or both feet on the ground, for example, golf, weightlifting or swimming (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019). The authors examined previous research by (Kruger et al. Citation2007), in which authors suggested that high-impact sports might lead to the hypertrophy of the pelvic floor muscles, potentially prolonging the second stage of labour. Based on this finding, Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) hypothesised that high-impact sports could be associated with adverse labour outcomes, such as serve perineal tears and higher rates of emergency caesarean sections. Perineal tears refer to tears in the area between the vagina and anus, that can occur childbirth, and they are classified from 1 to 4 based on their severity (Goh and Ellepola Citation2018). Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) defined serve perennial tears as third to fourth-degree.

Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) reported there was no association between participation in high-impact of low-impact sports and the length of the first and second stages of labour or the incidence of emergency caesarean section. In fact, high-impact elite athletes had a lower occurrence of third-degree to fourth-degree perineal tears than the low-impact group (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019). This suggests that participating in high-impact sports did not have a negative effect on the severe perineal tears (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019). Authors also found that the frequency of exercise training before and during the first pregnancy did not have a significant relationship to any subsequent delivery outcome (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019). Interestingly, this research revealed that regular, more frequent, and high-impact exercise during pregnancy was shown to reduce the need for emergency caesarean delivery in women having their first baby (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019). This may suggest that engaging in exercise during pregnancy, particularly high-impact activities, may have a beneficial impact on the mode of delivery.

In their cross-section design Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) examined pregnancy outcomes including birth, delivery and return to sport, in both elite athletes and active control (non-athletes). Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) found no significant differences between the two groups in terms of in complications during pregnancy and delivery, but athletes reported fewer common complaints, when compared to non-athletes.

Post-pregnancy athletic performances

Four research papers namely Darroch et al. (Citation2022), Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007), Kardel (Citation2005) and Forstmann et al. (Citation2023) focused on post-pregnancy athletic performance. Darroch et al. (Citation2022) conducted a study on elite athlete and found that participates who aimed to return to pre-pregnancy performance levels, did not experience a decrease in performance within the 1 to 3 year-post-pregnancy. In fact, approximately 56% of the running athletes actually improved their athletic performances after pregnancy. Darroch et al. (Citation2022) suggest that this may reflect a shift in the broader athletics culture and wider acceptance that individuals can continue to compete at an elite level, and even perform at a better level than before pregnancy. Darroch et al. (Citation2022) proposed that the forced break imposed by childbirth can have both mental and physical benefits contributing to the positive outcomes observed.

Similarly, in Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007) retrospective case study of 40 Norwegian elite athletes, 77% of the elite handball and football participants were able to maintain the same competitive level after giving birth, further supporting the notion that childbirth does not necessarily hinder an athlete carer progression.

In addition, Kardel (Citation2005) conducted a controlled clinical trial, where pregnant elite athletes from sports including biathlon, running and cycling were divided into two groups: one following a high-volume exercise program and the other following a medium-volume exercise program. The objective was to examine the effects of difference exercise volumes on post-pregnancy performance outcomes (Kardel Citation2005). Kardel (Citation2005) concluded that maintaining either a high- or medium-volume of exercise training during pregnancy contributed to a higher post-pregnancy fitness levels.

Finally, Forstmann et al. (Citation2023) investigated the impact of pregnancy amongst elite marathoners. The authors analysed the top 100 female marathon times of all time and specifically examined the thirty-seven runners who were also mothers. The findings revealed that 30% of these athletes ran their fastest marathon performance before their first pregnancy, whereas 70% achieved their best time after giving birth.

Indeed, Forstmann et al. (Citation2023) emphasized that maternity does not have a significant negative impact on the overall progression of high-level runners, who choose to return to elite running. The authors found that the ability to return and surpass previous performance level was influenced by the timing of the pregnancy in relation to the athletes age at the peak performance (Forstmann et al. Citation2023). The study revealed there is a is a large variability in the maternity break durations, spanning from 9 months to 94 months. This variability indicates that the decision to take a break and the duration of that break are highlight individualised, with some athletes achieving international-level performance after a longer break (Forstmann et al. Citation2023). Whereas the return to international competitions after nine months demonstrated that some athletes can quickly recover up to a highly competitive level (Forstmann et al. Citation2023). Overall, these findings suggest that with proper support and training, elite athlete can successfully resume and excel in their athletic careers after becoming mothers.

Information sources on exercise prescription whilst pregnant

Two research papers looked at information sources on exercise prescription whilst pregnant (Franklin et al. Citation2017; Pivarnik et al. Citation2016). Franklin et al. (Citation2017) conducted a survey among American female masters’ rowers to explore their perceptions about pregnancy. The study found that the primary information sources for the pregnant rowers were healthcare providers (60%) such as physicians and midwifes. The internet (31%), and friend(s) (26%) were also mentioned as a secondary source of information. Surprisingly, only a small percentage of participants (2%) relied on peer-reviewed research sources as their premier sources. Rowers cited healthcare providers as the most reliable source of information when it came to questions regarding exercise during pregnancy (Franklin et al. Citation2017).

On the other hand, Pivarnik et al. (Citation2016) investigated pregnancy exercise counselling practises among healthcare provides. The study revealed that providers often recommend reducing exercise intensity and/or duration during pregnancy or advise pregnant women to maintain a heart rate below an arbitrary maternal heart rate (e.g. 140 bpm) based on outdated guidelines. Providers also admitted a lack of sufficient knowledge regarding pregnancy exercise guidelines (Pivarnik et al. Citation2016). This study highlighted the need for incorporating education on exercise during pregnancy in medical education programs for healthcare professional, both at the undergraduate and graduate level (Pivarnik et al. Citation2016). This emphasizes the importance of ensuring that healthcare providers are well-informed about the latest guidelines and recommendations regarding exercise during pregnancy.

Category 3: qualitative methodology

Qualitative study characteristics

This scoping review identified twenty qualitative studies in relation to the topic of elite female sportspeople and pregnancy. Of these twenty studies eight were conducted in Canada, three in both the United States and Spain, two in both the United Kingdom and Australia and one in Denmark, Germany, Austria, Slovenia and New Zealand. These qualitative papers were published from 2001 to 2023. provides a summary overview of the qualitative studies.

Qualitative study sampling strategies and methodologies

The total number of participants for the qualitative studies was 236. 98% of the participants in the qualitative studies were elite athletes with pregnancy experiences. 2% of the athletes were elite athletes who retired due to becoming pregnant (Pedersen Citation2001).

The most popular qualitative methodology employed by five studies was a phenomenological design (Darroch et al. Citation2019; Dietz et al. Citation2022; Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017). Two studies indicated they employed an interpretive qualitative design (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Culvin and Bowes Citation2021), two studies utilized a qualitative descriptive (Davenport et al. (Citation2022, Citation2023), two adopted an ethnographic content analysis approach (McGannon et al. Citation2015, Citation2017) and two were located within a symbolic interactionism paradigm (Palmer and Leberman Citation2009; Pedersen Citation2001). Other methodological approaches adopted included discourse analysis (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017), a relativist ontological perspective (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022), textual/narrative analysis (McGannon et al. Citation2012, 2019, Citation2022), a case study approach (Giles et al. Citation2016), and finally post-positivism (Tekavc, Wylleman, and Cecić Erpič Citation2020)

Theoretical frameworks

In relation to theoretical frameworks, three authors drew from critical feminist theory (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Giles et al. Citation2016; Darroch et al. Citation2019), Massey and Whitehead (Citation2022) used identify theory and two papers were positioned within social constructionism theory (McGannon et al. Citation2012, Citation2017). All three papers Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017) were located with a phenomenological theoretical position advocated by Husserl. Palmer and Leberman (Citation2009) utilised an identity theory, whilst Tekavc, Wylleman, and Cecić Erpič (Citation2020) were aligned to the theoretical assumptions of the holistic athletic career model (HAC). Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) used poststructuralism, Dietz et al. (Citation2022) indicated the use of deductive theory, and Culvin and Bowes (Citation2021) drew from Bourdieu theory concerning Habitus and McGannon, Graper, and McMahon (Citation2022) used a narrative theory. Six papers (Davenport et al. Citation2022; Davenport et al. Citation2023; McGannon et al. Citation2015, 2019; Pedersen Citation2001; did not explicitly indicate a specific theoretical framework for their studies.

Qualitative sports mentioned

Of the twenty included qualitative studies analysed, eighteen explicitly mentioned the sport(s) under investigation. Among these studies, seven studies included participants from various sports. Davenport et al. (Citation2023) conducted their research with athletes engaged in a diverse range of sports, including weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing sprint and endurance sports, technical sports, ball-game sports, and power sports. Similarly, Dietz et al. (Citation2022) examined participants involved in endurance sports, ball and backstroke sports, dance, and CrossFit. Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2017) included participants from a diverse range of sports such as track and field, triathlon, archery, distance running, handball, rugby, tennis, canoeing, basketball, taekwondo, and judo. Likewise, Palmer and Leberman (Citation2009) included participants from netball, rugby, rugby league and shooting. Tekavc, Wylleman and Cecić Erpič (Citation2020) involved athletes from badminton, track and field, judo, gymnastics, canoeing, triathlon, and taekwondo.

Ten studies focused on participants from a single sport, with running being the most popular individual sport (6/10). Appleby and Fisher (Citation2009), Darroch et al. (Citation2019) Giles et al. (Citation2016), Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) and McGannon et al. (Citation2012, 2019), examined individuals involved in distance running. Massey and Whitehead (Citation2022) concentrated on participants from the sport of track and field. Culvin and Bowes (Citation2021), investigated the experiences of women who were professional footballers. McGannon et al. (Citation2017) focused on a single professional tennis player, while McGannon, Graper, and McMahon (Citation2022) studied figure skaters experience.

Three studies did not explicitly state the sports under investigation. In the case of Davenport et al. (Citation2022) this omission was intentional to ensure participant anonymity. Similarly, McGannon et al. (Citation2015) and Pedersen (Citation2001) did not explicitly mention the sports in which the athletes participated in.

Qualitative results

The twenty qualitative studies covered a range of topics. These were grouped into main themes: Societal expectations; Return to training; Support systems; New feelings during the motherhood experience; Maternity leave, sponsorship, and governing bodies.

Societal expectations

Four studies explored themes related to the social expectation of motherhood for elite female athletes (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Davenport et al. Citation2023, Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2016; McGannon et al. Citation2012).

Appleby and Fisher (Citation2009) found their participants perceived varying expectations from the running community after they had children (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009). Some participants felt that the running community expected them to quickly return to competition, as if nothing in their lives had changed. On the other hand, there were contrasting expectations for participants, that they would never compete again after giving birth (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009). The participants expressed that they sensed that others in the running community believed that their competitive days were over once they became pregnant (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009).

Similarly, Davenport et al. (Citation2023) interviewed participants from various sports such as weight-bearing, non-weight-bearing, sprint and endurance sports, technical sports, ballgame, and power sports. These participants shared their experience and described a common societal narrative that implies female athletes must choose between being an elite athlete or starting a family. When these athletes became pregnant while training at an elite level, they received messages such as ‘Happy retirement’ or ‘Congratulations you’re done (competing) now’. Consequently, the athletes found themselves questioning what was truly possible for them in terms of combining motherhood with their athletic endeavours (Davenport et al. Citation2023).

Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2016) conducted a study involving female athletes from various sports such as track and field, triathlon, archery, distance running, handball, rugby, tennis, canoeing, basketball, taekwondo, and judo. Their findings revealed that these sportswomen perceived maternity as a transformation process. In which initially, they held both the roles of ‘woman’ and the role ‘sportswoman’ but as the pregnancy progressed, they ultimately identified themselves primarily as ‘mother’.

Similarly, McGannon et al. (Citation2012) conducted a textual analysis and discovered the media portrayed pregnancy and motherhood as redemption narrative, particularly in the context of Paula Radcliffe’s elite athlete identity. The media framed Radcliffe’s transition into motherhood as a means of redemption, whereby she embraced an additional identify as a mother merging it with her elite athlete identity. In essence, the idea of pregnancy and motherhood as a form of redemption emerged from the analysis conducted by McGannon et al. (Citation2012) with the media suggesting that solely being an elite athlete was not considered fulfilling enough for Radcliffe (McGannon et al. Citation2012).

Return to training

Six authors explored the experience of elite women’s return to training postpartum (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017; Tekavc, Wylleman, and Cecić Erpič Citation2020; Davenport et al. Citation2022; Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2016; Massey and Whitehead Citation2022).

Appleby and Fisher (Citation2009) summarised that their distance running participants felt they had a reduction in time to train, due to having children. However, participants felt this lack of time benefited them as athletes, as they were more likely to get in ‘quality’ miles versus ‘quantity’ miles (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009). Therefore, this reduction in training increased their performance, due to restricting overtraining and making them more centred on their actual performance goals.

Correspondingly Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) found that many female athletes felt that returning to elite-level running made them ‘better mothers’. Additionally, some participants felt that having children also improved their athletic performance (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017). In general, participants perceived that motherhood had a positive effect on their general well-being by giving them a ‘more positive outlook on life’. (Tekavc, Wylleman, and Cecić Erpič Citation2020)

Indeed, Davenport et al. (Citation2022) conveyed that their participants experienced significant pressure and unrealistic expectations regarding returning to sport after giving birth. The participants expressed feeling pressure, particularly by their sponsors, to quickly resume and return to their involvement in elite sport. This pressure stemmed from the financial obligations and expectations associated with sponsorship agreements. As a result, there were financial pressures to return to elite sport after childbirth (Davenport et al. Citation2022).

Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2016) explored themes related to physical changes in the body and how these women felt with these changes. Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2016) included women from various range of sports such as track and field, triathlon, archery, distance running, handball, rugby, tennis, canoeing, basketball, taekwondo, and judo The findings indicate that most of the sportswomen felt that their pregnant bodies were a different one and was a substitute for their usual bodies. The participants expressed a sense of unfamiliarity and a lack of control over this new body during the pregnancy experience (Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2016).

Similarly, Massey and Whitehead (Citation2022) found that participants who were at an early stage of motherhood, had concerns related to the change in their bodies and a shift in physical identity. Throughout pregnancy and early postpartum period, the participants encountered to new bodily experiences (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022). These experiences were characterised by a loss of control, reduced performance, and changes to how their body functions, therefore, resulting in a shift in physical identity (Massey and Whitehead Citation2022).

Support systems

Two reviewed papers also explored the effect of the support systems on athletes’ return to elite sport postpartum (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017; Dietz et al. Citation2022) In Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017), every participant from a distance running background emphasized the importance of having support networks in making meaningful decisions regarding motherhood and continuing their career in elite sport. The authors concluded that support in various capacities is essential for elite female distance runners to return to training and competition following pregnancy (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017).

Similarly, Davenport et al. (Citation2022) summarised that their athletes (from undisclosed sports) highlighted the importance of support provided for parents by sporting organizations for parents, which is instrumental to athletes’ successful return to sports postpartum.

Additionally, Dietz et al. (Citation2022) included female mothering athletes, who played a number of elite sports such as endurance sports, ball and backstroke sports, dance and cross fit. The participants in their study expressed that environmental support was a main condition to successfully combine a sporting career with planning or having a family.

Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) participants communicated challenges with childcare issues and the need to develop alternative strategies in order to continue competing in elite sport. One participant mentioned ‘I always actually picked races that are close, within like a hometown. Because it’s always been a problem trying to get a babysitter and getting to the race. I think the biggest issue is having a support system with childcare and the whole lot’ (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017). Therefore, emphasizing the importance of having a strong support system that can provide assistance with childcare in essential in continued participation in competitive sport after giving birth.

New feelings during the motherhood experience

Four studies identified similar themes related to new feelings that arose after becoming mothers in relation to their athletic pursuits. (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Palmer and Leberman Citation2009; Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017; Martinez-Pascual et al. Citation2016). Appleby and Fisher (Citation2009) distance running participants communicated a decrease in performance-related pressure due to motherhood. Participants attributed this decline to gaining a unique perspective on running, feeling less included to prove themselves to other and finding a sense of self-satisfaction and enjoyment to running and competing after pregnancy (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009). Palmer and Leberman (Citation2009) had participants from diverse range of sports such as netball, rugby, rugby league and shooting. Participants expressed that motherhood had a positive impact on their resilience and adaptability. Participants communicated that they felt becoming mother made them better equipped to deal with the challenges that come with elite-level sports (Palmer and Leberman Citation2009).

Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) conveyed their athletes perceived a conflict between the inherently selfish nature of being an elite athlete, which demands time for training, rest, physiotherapy/massage, and sponsorship commitments, were at odd of the selfless nature of motherhood. Many of Darroch and Hillsburg (Citation2017) participants reported feeling selfish when they prioritized their own needs over those of their children and spouses above their own. This conflict between the selfish nature of elite sport and their responsibilities as mother harvested feelings of guilt for the participants (Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017).

Similarly, Martinez-Pascual et al. (Citation2016) found that sportswomen, returning to their roles as athletes after pregnancy experienced feeling of guilt. Likewise, Palmer and Leberman (Citation2009), also communicated that their female participants mentioned feelings of guilt. This guilt manifested in feeling like they were missing on important events in their children’s lives due to their sporting commitments (Palmer and Leberman Citation2009).

McGannon et al. (Citation2015) conducted an ethnographic content analysis of media representation during the 2012 Olympic year, focusing on how athlete mothers were portrayed. One of the key themes identified in their analysis was the conflict between the athlete and mother identifies, described as where the demands of athletics and motherhood were depicted as opposing forces (McGannon et al. Citation2015). The media often presented a narrative that forced women to choose between pursing their athletic careers and fulfilling their societal roles as mothers. Athlete mothers were depicted as experiencing psychological distress and feeling of guilt when they had to take time away from their children to train or travel for competing (McGannon et al. Citation2015).

Maternity leave, sponsorship, and governing bodies

Four studies explored themes related to sponsorships, maternity leave, and governing bodies (Culvin and Bowes Citation2021; Darroch et al. Citation2022; Davenport et al. Citation2023). In their study, Culvin and Bowes (Citation2021) focus on gender-specific issues faced by professional women footballers. Authors highlighted the clear omissions and inadequacies in the employment policies and contracts of these athletes particularly concerning pregnancy and maternity rights. Despite the legal obligation for policies to support women in their maternity rights (in the UK where the study was conducted), the short-term contracts that these players operate under were found to be insufficient in meeting their needs (Culvin and Bowes Citation2021). Culvin and Bowes (Citation2021) express that their professional women footballers expressed a lack of trust in clubs when it came to providing a contractual support including maternity leave and related benefit for their family endeavour which leads to a mistrust of their clubs.

Darroch et al. (Citation2019) communicated that their elite female runner participants strategically plan their pregnancies in order to be as financially stable as possible. The timing of pregnancies is carefully considered to avoid missing major championship and races, and in turn minimized the financial impact of losing their sponsorship. Darroch et al. (Citation2019) summarized that elite mothering distance runners experience a lack of support, especially during the period around pregnancy and postpartum return to training and competition.

Darroch et al. (Citation2019) highlighted the complexity of sexism in sports, stating that is often goes unnoticed despite bring overtly present. The participants in the study provided evidence of well-known but unchallenged practise by corporations and sport’s governing bodies that constrain a woman’s choices regarding when to children (Darroch et al. Citation2019). The athletes discussed how they planned their pregnancies around sporting competitions, carding applications, and key contractual obligations in order to alleviate financial strain during pregnancy (Darroch et al. Citation2019).

However, participants offered suggestions on how the sponsor can better market and include mothering athletes in their campaigns. They proposed that pregnant and postpartum elite women distance runners have the potential to appeal to a new and potentially larger audience of sports fans and mothers (Darroch et al. Citation2019). They suggest that there is an untapped market and potential for sponsors to engage with their specific demographic (Darroch et al. Citation2019).

Finally in Davenport et al. (Citation2023) participants from various sports categories including weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing sprint and endurance sports, technical sports, ball-game sports and power sports, highlighted the importance of financial support during pregnancy and postpartum periods to maintain their status as an elite athlete. The participants acknowledged that government funding system had recently made some positive changes to support pregnant athletes, but further improvements were still needed. The study indicated that athletes experienced challenges in navigating the rules and regulation surrounding funding during pregnancy and postpartum, as they were often unclear and inconsistent across different national sports organisations.

Discussion and future research

This paper took a comprehensive approach by combining qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method papers that examine pregnancy and motherhood experiences among elite athletes. Through the synthesis of literature, a nuanced understanding emerged, encompassing both biomedical and sociological aspects related to female elite athletes’ experience of pregnancy and motherhood.

The research findings from Sigurdardottir et al. (Citation2019) and Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) indicate that there were no significant differences in the occurrence of complications during pregnancy and delivery between elite athletes and non-athletes. Athletes often reported fewer common complaints compared to non-athletes with pregnancy and delivery experiences (Sigurdardottir et al. Citation2019; Sundgot-Borgen et al. Citation2019). These findings are noteworthy, because they address concerns expressed by some athletes that exercising during pregnancy may lead to complication for both the child and the birthing process (L’Heveder et al. Citation2022; Wowdzia et al. Citation2020).

These feeling of uncertainty are combated by insufficient high-quality evidence necessary to guide athletes safely during the postpartum period and with their return to sport. Many coaches’ and relevant support staff express feelings of uncertainty due to the lack of standardized approaches in managing pregnant and postpartum period athletes (Jackson et al. Citation2022). The insufficient evidence and lack of standardized approach contributes to the difficulties faced in providing athlete with the necessary support and guidelines during pregnancy and in the postpartum period.

Additionally, it has been found that non-athletes tended to experience higher rates of urinary incontinence during pregnancy and in the post-partum period when compared elite athletes (Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007). This finding is noteworthy because previous research suggests that female athletes who experience urinary incontinence during sporting activity may feel embarrassed and frustrated, making them more likely to drop out of their respective sports (Whitney et al. Citation2021; Dakic et al. Citation2023). However, only a small percentage (15%) of elite athletes in one study engaged in pelvic floor muscles training (PMFT) during pregnancy, and only half of them (50%) exercised the pelvic floor muscles in the 6-week postpartum period (Bø and Backe-Hansen (Citation2007). A meta-analysis conducted by Nie et al. (Citation2017) demonstrated that regular use of PMFT can provide symptom relief for urinary incontinence. Therefore, further research investigating the use of PMFT specifically among the elite athlete population and its effect on urinary incontinence would be valuable to promote continued participation in sport in the post-partum period.

The current literature on injury risk during pregnancy and the postpartum period in elite athletes is still limited and presented conflicting findings. Kimber et al. (Citation2021) conducted a systematic and meta-analysis which identified that that there was extremely low evidence in the summarised literature that elite athletes who return to physical activity after the postpartum period may have an increased risk of injury, when compared to non-elite athletes. However, it is worth noting the same authors Kimber et al. (Citation2021) also identified a disproportionately high rate of sacral stress fracture in postpartum female elite athletes compared to the non-postpartum population.

It is crucial to consider the limitations of the studies that contribute to the findings of a disproportionately high rate of sacral stress fractures amongst elite postpartum athletes. Kimber et al. (Citation2021) based their conclusion on three studies, with one study having a sample of 110 individuals long distance running athletes, including 35 nationally ranked athletes, where nine females sustained an injury, however communicated that none of these injuries were stress fractures and there was no information on how many of the injured individual were elite athletes, limiting the validity of the findings (Tenforde et al. Citation2015). Another literature source by Solli and Sandbakk (Citation2018) which was a case study of single athlete, which limits the generalisability of the findings. Finally, Sundgot-Borgen et al. (Citation2019) did communicate a risk of sacral stress fracture with 3 out of 34 (11%) of their elite athlete populations from ball and endurances sports getting a sacral stress fracture during post-partum period. Overall, these studies suggest there is mixed range of findings and not a clear consensus of the risk of sacral stress fracture in postpartum elite athlete population.

Nevertheless, sacral stress fractures are not exclusive to postpartum elite athletes, as a systematic review conducted by Beit Ner et al. (Citation2022) found that young female athletes are the most frequent sufferers of sacral stress fracture, when compared to both athletes and general populations. Sacral stress fracture diagnosis is a developing research area and causation factors are poorly understood (Beit Ner et al. Citation2022). Therefore, further research exploring the injury risk and prevention strategies of sacral-stress fractures in female elite athletes’ cohorts, including pregnant and mothering athletes would be beneficial to athletes and there surrounding health team. By gaining a better understanding of specific risk factors and mechanisms involved, appropriate prevention and management strategies can be developed to mitigate injuries in this population.

Research findings suggest that women who return to elite sport after pregnancy can expect to return to a similar pre-pregnancy level or even see improvements in their athletic performance (Darroch et al. Citation2022). Specifically in the sports of handball and football, and distance running have clearly communicated athletes are likely to see improvement post-partum (Darroch et al. Citation2022; Bø and Backe-Hansen Citation2007; Kardel Citation2005; Forstmann et al. Citation2023).

Qualitative studies in the literature may provide reasoning for the improvements observed in athletic performance after giving birth. Some participants in these studies conveyed that having children improved their athletic performance. Participants expressed that these constraints imposed by motherhood, such as reduced training time, forced them to prioritize quality of quantity (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009; Darroch and Hillsburg Citation2017). These participants hypothesised that this shift in training quality over quantity, led to improved performance by preventing overtraining and keeping them more centred on their actual performance goals (Appleby and Fisher Citation2009). Overall, these findings suggest that with proper support and training, elite athletes can successfully resume and excel in their athletic careers after becoming mothers.

The reviewed qualitative studies focused on a variety of social factors that can impact a female athlete’s return to elite sport. Female participants emphasized the important roles played by significant others, particularly their partner, family, and coach(es), in supporting their athletic pursuits and allowing them to make meaningful decisions about elite sports and motherhood (Davenport et al. Citation2023). Childcare emerged as a significant barrier to training and competing in elite sport in several qualitative studies examining the experiences of female elite athletes during the postpartum period. This finding is supported by authors Beilock, Feltz, and Pivarnik (Citation2001), in which 76% of elite athlete participants identified that lack of childcare was the biggest barrier to training in the postpartum period. Childcare also posed challenges within team systems, as coaches expressed uncertainty about players with children being able to find suitable childcare for games, which led them to be less likely to select these players (Forsyth et al. Citation2023). To address these issues, further research is necessary to examine the extent to which childcare poses a significant barrier in various sport context. Understanding the specific challenges and identifying potential solutions to support elite women successfully competing in elite sport.

The research team have identified several limitations of this scoping review which are important to acknowledge in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the research conducted.

One such limitation was that the majority of participants in the reviewed studies were married and had financial support from their partners, which may not reflect the experience of single athletes or those without spousal financial support. Additionally, there was limited literature from perspectives of LGBTQIA+ athletes and para-athletes. The literature of elite female athletes and pregnancy tends to be dominated by athletes from Western, Anglo-Saxon nations. The perspectives of athletes from non-Western backgrounds are underrepresented and there is a need for studies that include diverse cultural perspectives.

Many of the mixed-method studies (75%) did not explicitly mention the sports in which the athlete competed, making it difficult to compare findings across different experiences. Furthermore, despite efforts to conduct a comprehensive scoping review, there is a possibility that relevant studies were not identified by the search terms used and screening of reference list of included evidence of additional studies.

We recommend that future research explores the perspectives of athletes from non-western, non-heteronormative and para-athlete backgrounds and examining the impact of pelvic floor muscle training and its impact on urinary incontinence in elite athlete population. Overall, the findings of this scoping review contribute to the understanding of female athlete’s transition to motherhood and can inform coaches, managers, physiotherapists, and governing bodies in better understanding and supporting athletes during this transitional process. Finally, we recognise and encourage the uniqueness of each athlete’s pregnancy experience and encourage avoiding generalizations when interpreting our research findings and using them in practise.

Acknowledgements

This review is to contribute towards a Master by Research (BM)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Appleby, Karen M., and Leslie A. Fisher. 2009. “Running in and out of Motherhood”: Elite Distance Runners’ Experiences of Returning to Competition after Pregnancy.” Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal 18 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1123/wspaj.18.1.3.

- Beilock, Sian L., Deborah L. Feltz, and James M. Pivarnik. 2001. “Training Patterns of Athletes during Pregnancy and Postpartum.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 72 (1): 39–46. doi:10.1080/02701367.2001.10608930.

- Beit Ner, Eran, Oded Rabau, Sad Dosani, Uri Hazan, Yoram Anekstein, and Yossi Smorick. 2022. “Sacral Stress Fractures in Athletes.” European Spine Journal 21 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s00586-021-07043-.

- Bø, K., and K. L. Backe-Hansen. 2007. “Do Elite Athletes Experience Low Back, Pelvic Girdle and Pelvic Floor Complaints during and after Pregnancy?” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 17 (5): 480–487. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00599.x.

- Bø, Kari, Raul Artal, Ruben Barakat, Wendy Brown, Gregory A. L. Davies, Michael Dooley, Kelly R. Evenson, et al. 2016a. “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016 Evidence Summary from the Ioc Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 1—Exercise in Women Planning Pregnancy and Those Who Are Pregnant.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 50 (10): 571–589. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096218.

- Bø, Kari, Raul Artal, Ruben Barakat, Wendy Brown, Michael Dooley, Kelly R. Evenson, Lene A. H. Haakstad, et al. 2016b. “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016 Evidence Summary from the Ioc Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 2—The Effect of Exercise on the Fetus, Labour and Birth.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 50 (21): 1297–1305. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096810.

- Bø, Kari, Raul Artal, Ruben Barakat, Wendy J. Brown, Gregory A. L. Davies, Michael Dooley, Kelly R. Evenson, et al. 2018. “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016/2017 Evidence Summary from the Ioc Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 5. Recommendations for Health Professionals and Active Women.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 52 (17): 1080–1085. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2018-099351.

- Bø, Kari, Raul Artal, Ruben Barakat, Wendy J. Brown, Gregory A. L. Davies, Michael Dooley, Kelly R. Evenson, et al. 2017a. “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016/17 Evidence Summary from the Ioc Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3—Exercise in the Postpartum Period.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 51 (21): 1516–1525. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097964.

- Bø, Kari, Raul Artal, Ruben Barakat, Wendy J. Brown, Gregory A. L. Davies, Mike Dooley, Kelly R. Evenson, et al. 2017b. “Exercise and Pregnancy in Recreational and Elite Athletes: 2016/17 Evidence Summary from the Ioc Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 4—Recommendations for Future Research.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 51 (24): 1724–1726. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098387.

- Cooper, Simon, Robin Cant Michelle Kelly, Tracy Levett-Jones, Lisa McKenna, Philippa Seaton, and Fiona Bogossian. 2021. “An evidence-based checklist for improving scoping review quality.” Clinical Nursing Research doi:10.1177/1054773819846024.

- Culvin, Alex, and Ali Bowes. 2021. “The Incompatibility of Motherhood and Professional Women’s Football in England.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 3: 730151–730151. doi:10.3389/fspor.2021.730151.

- Dakic, Jodie G., Jean Hay-Smith, Kuan-Yin Lin, Jill Cook, and Helena C. Frawley. 2023. “Experience of Playing Sport or Exercising for Women with Pelvic Floor Symptoms: A Qualitative Study.” Sports Medicine - Open 9 (1): 25–12. doi:10.1186/s40798-023-00565-9.

- Darroch, Francine E., Audrey R. Giles, Heather Hillsburg, and Roisin McGettigan-Dumas. 2019. “Running from Responsibility: Athletic Governing Bodies, Corporate Sponsors, and the Failure to Support Pregnant and Postpartum Elite Female Distance Runners.” Sport in Society 22 (12): 2141–2160. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1567495.

- Darroch, Francine, Amy Schneeberg, Ryan Brodie, Zachary M. Ferraro, Dylan Wykes, Sarita Hira, Audrey Giles, Kristi B. Adamo, and Trent Stellingwerff. 2022. “Impact of Pregnancy in 42 Elite to World-Class Runners on Training and Performance Outcomes.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 55 (1): 93–100. doi:10.1249/MSS.0000000000003025.

- Darroch, Francine, and Heather Hillsburg. 2017. “Keeping Pace: Mother versus Athlete Identity among Elite Long Distance Runners.” Women’s Studies International Forum 62: 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2017.03.005.

- Davenport, Margie H., Autumn Nesdoly, Lauren Ray, Jane S. Thornton, Rshmi Khurana, and Tara-Leigh F. McHugh. 2022. “Pushing for Change: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Elite Athletes during Pregnancy.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 56 (8): 452–457. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2021-104755.

- Davenport, Margie H., Lauren Ray, Autumn Nesdoly, Jane Thornton, Rshmi Khurana, and Tara-Leigh F. McHugh. 2023. “We’re Not Superhuman, We’re Human: A Qualitative Description of Elite Athletes’ Experiences of Return to Sport after Childbirth.” Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 53 (1): 269–279. doi:10.1007/s40279-022-01730-y.

- Dietz, Pavel, Larissa Legat, Matteo C. Sattler, and Mireille N. M. van Poppel. 2022. “Triple Careers of Athletes: Exploring the Challenges of Planning a Pregnancy among Female Elite Athletes Using Semi-Structured Interviews.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 22 (1): 643. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-04967-7.

- Forstmann, Nicolas, Alice Meignié, Quentin De Larochelambert, Stephanie Duncombe, Karine Schaal, Carole Maître, Jean-François Toussaint, and Juliana Antero. 2023. “Does Maternity during Sports Career Jeopardize Future Athletic Success in Elite Marathon Runners?” European Journal of Sport Science 23 (6): 896–903. doi:10.1080/17461391.2022.2089054.

- Forsyth, J. J., L. Sams, A. D. Blackett, N. Ellis, and M. S. Abouna. 2023. “Menstrual Cycle, Hormonal Contraception and Pregnancy in Women’s Football: Perceptions of Players, Coaches and Managers.” Sport in Society 26 (7): 1280–1295. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2125385.

- Franklin, Ashley, Joanna Mishtal, Teresa Johnson, and Judith Simms-Cendan. 2017. “Rowers’ Self-Reported Behaviors, Attitudes, and Safety Concerns Related to Exercise, Training, and Competition during Pregnancy.” Cureus 9 (8): e1534. doi:10.7759/cureus.1534.

- Garti, Isabella, Michelle Gray, Jing-Yu Tan, and Angela Bromley. 2021. “Midwives’ Knowledge of Pre-Eclampsia Management: A Scoping Review.” Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives 34 (1): 87–104. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2020.08.010.

- Giles, Audrey R., Breanna Phillipps, Francine E. Darroch, and Roisin McGettigan-Dumas. 2016. “Elite Distance Runners and Breastfeeding: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Human Lactation: Official Journal of International Lactation Consultant Association 32 (4): 627–632. doi:10.1177/0890334416661507.

- Goh, Ryan,Daryl Goh, andHasthika Ellepola. 2018. “Perineal Tears- A Review.” Australian Journal of General Practice 47 (1-2): 35–38. doi:10.31128/AFP-09-17-433329429318.

- Jackson, Thea, Emma L. Bostock, Amal Hassan, Julie P. Greeves, Craig Sale, and Kirsty J. Elliott-Sale. 2022. “The Legacy of Pregnancy: Elite Athletes and Women in Arduous Occupations.” Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews 50 (1): 14–24. doi:10.1249/JES.0000000000000274.

- Kardel, Kristin Reimers. 2005. “Effects of Intense Training during and after Pregnancy in Top-Level Athletes.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 15 (2): 79–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00426.x.

- Khalil, Hanan, Marsha Bennett, Christina Godfrey, Patricia McInerney, Zac Munn, and Micah Peters. 2020. “Evaluation of the JBI Scoping Reviews Methodology by Current Users.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 18 (1): 95–100. doi:10.1097/XEB.0000000000000202.