Abstract

European governments have increasingly relied on voluntary sport clubs (VSCs) to address social issues, particularly refugees’ social inclusion. Contemporarily, millions of Ukrainian refugees have fled to neighbouring countries; VSCs are thus more relevant than ever. This review synthesised the research on VSCs’ enabling and constraining features regarding refugees’ social inclusion. The review was conceptualised according to Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time framework and DeLuca’s spectrum of social inclusion. The key findings indicate that: (i) initiatives are propelled by individuals with pre-existing capital and a commitment to social justice; (ii) the interaction between the organisational culture of VSCs and these individuals plays a crucial role in achieving social inclusion; (iii) VSCs often overlook refugees’ strengths; and (iv) cross-sectoral collaborations prove beneficial for VSCs. In summary, to effectively address refugees’ social inclusion, VSCs need support, resources, intercultural education, and exposure to nuanced notions of social inclusion.

Introduction

European governments have increasingly relied on sport, specifically voluntary sport clubs (VSCs), to address social issues, including the social inclusion of refugees, henceforth called ‘newcomers’. It is imperative to acknowledge that the term ‘newcomer’ is widely used in immigration policy, particularly in the context of highly skilled migrant populations. Here, the term is used to avoid insensitive terminology, but it needs to be emphasised that the population in question is not economic migrants or necessarily highly-skilled migrants but people who are forcibly displaced.

A key notion behind this transfer of responsibility has been that ‘…communities like sport clubs have the potential to solve a series of welfare tasks more effectively and for a lower cost than the state’ (Agergaard Citation2011 346). A landmark in the history of European VSCs’ societal role occurred in conjunction with the events in the Middle East, which triggered the so-called ‘refugee crisis’Footnote1 in 2015 (Michelini Citation2021). For example, the conflict in Syria alone forced approximately 13 million Syrians out of their home, one million of whom sought asylum in European countries (UNHCR Citation2021). Consequently, European countries’ sport movements suddenly became important actors in addressing newcomers’ well-being and ‘integration’. In this sense, integration is a contested term, often referred to as a ‘two-way process’ of mutual adaptation for newcomers and host societies (Berry Citation1997). However, in reality, the expectations mainly rest upon refugees and encompass several areas, such as learning the language, entering the labour market, and learning host society norms (Agergaard Citation2018). Contrary to narratives of sport’s neutrality and colour-blindness, it is clear that sport clubs are arenas where present expectations are placed on newcomers and migrants (Agergaard Citation2011 Citation2018). Accordingly, while VSCs have historically held an important societal position, their societal and political relevance have increased during the last decade, and they can be conceived of as hubs of knowledge and experience in these matters.

Forced migration continues to be an important contemporary topic, given the events in Ukraine, where over seven million people have fled to neighbouring countries at the time of writing (UNHCR Citation2022). Given the nature of forced displacement, severe mental and physical health issues are salient factors to be addressed by the countries that receive these individuals. According to the World Health Organization (WHO Europe Citation2022), Ukrainian refugees are considered a high-risk population in terms of mental health. They are at an elevated risk for chronic and non-communicable diseases. Ioffe et al. (Citation2022) have voiced the need for receiving countries to implement appropriate evidence-based practices to accommodate any potential health issues that Ukrainian newcomers may experience. In this regard, sports are not exclusively aimed at enhancing physical health but can also provide a comforting, safe space and attend to people’s well-being in a broader sense.

Since VSCs constitute a major share of European countries’ civil society, they have an immense potential to reach many diverse individuals. However, researchers have also voiced a need to be modest in estimating how VSCs contribute toward social policy goals and newcomers’ social inclusion (Dukic, McDonald, and Spaaij Citation2017). First and foremost, this contribution is because (European) VSCs are founded by members, for members, and are not obliged to act as governmental agents (Nowy and Breuer Citation2019). VSCs are diverse in logic, capacity, and intention to implement policy, producing different results (Fahlén and Stenling Citation2016). Considering all of these factors and the dominant position of VSCs as the ‘heart’ of the European sport movement (Nagel et al. Citation2020), it is essential to systematically assess how they contribute to the social inclusion of newcomers. Accordingly, in the face of a new so-called ‘refugee wave’, this paper seeks to take stock of the research that has thus far contributed to a greater understanding of the social inclusion of newcomers in VSCs. This research seems warranted, given that VSCs will, once again, be put to the test in the near future. To the author’s knowledge, no work has thus far systematically assessed European VSCs’ ability to contribute toward newcomers’ social inclusion.

The paper proceeds as follows. First, an overview of the theoretical framings that guide the review, including Bronfenbrenner’s Process-Person-Context-Time (PPCT) model and DeLuca’s (Citation2013) definition of social inclusion, is given. Secondly, an account of the method is given before presenting the results according to the PPCT framework. The paper concludes by discussing the review’s findings, limitations, and a reminder of VSCs’ dominant position within the European sport movement, for better or worse.

Bronfenbrenner’s PPCT model and DeLuca’s continuum of social inclusion

This section introduces the PPCT model and the interpretation of social inclusion, as DeLuca (Citation2013) posited. Bronfenbrenner’s early work (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977 Citation1979) constituted the basis for the socioecological model, in which nested structures contain the individual. These structures consist of the micro-level (e.g. a child’s coach), meso-level (e.g. relationships between the coach and the child’s parents), the exo-level (e.g. overarching institutions, such as media or sport confederations), and the macro-level (e.g. societal blueprints and culture).

This model was expanded by Bronfenbrenner (Citation2005), with more conceptual attention paid to the individual’s agency, characteristics, and how the environment responds to the individual because of the individual’s characteristics (e.g. sex, age). These characteristics are analytically crucial when connected to the individual’s environment, forming what is known as the proximal process. The proximal processes are conceptualised as the interaction between a biopsychological human organism and the individuals, systems, and objects in the individual’s ecology. This interaction must occur with a certain frequency and over time. The proximal processes are considered the engine of the framework (Tudge et al. Citation2009). The context in the PPCT framework is the totality of the already developed nested structures in the early versions. Bronfenbrenner’s final addition was time. This factor can be divided into micro-, meso-, and macro-time. For brevity’s sake, the latter temporal aspect is important. Macro-time refers to history, i.e. broader segments of time that witness critical events and responses that several agents and institutions shape.

To the author’s knowledge, only one article on newcomers’ lived experiences and resettlement processes and sport utilised the PPCT framework (Truskewycz, Drummond, and Jeanes Citation2022). Truskewycz, Drummond, and Jeanes (Citation2022) discussed the implications of using the PPCT framework in this context. Notwithstanding the analytical utility of disregarding the old models, some important warnings are also given. Specifically, the PPCT framework does not adequately consider power dynamics—power issues are of immense importance in a newcomer’s context since newcomers face significant challenges and may not have access to the same resources as people without the migratory experience. In fact, Truskewycz, Drummond, and Jeanes (Citation2022) argued that the PPCT model may even reinforce existing unequal structures if applied uncritically. A more thorough understanding of social inclusion and its nuances must thus be invoked. In this regard, social inclusion is a conceptual quagmire (Schaillée, Haudenhuyse, and Bradt Citation2019). An umbrella understanding of social inclusion in the context of newcomers and sport generally refers to sport as one way for newcomers to develop and acquire access to one of the many ‘integration’ markers posited by Ager and Strang (Citation2008), such as housing, education, healthcare and language proficiency (Block and Gibbs Citation2017). As Block and Gibbs (Citation2017) further argued, sports clubs may work as mediators to one or more of these markers, and social inclusion in sport may mean that newcomers can partake in society in a meaningful way, thus attending to their overall well-being.

The study drew upon Schaillée, Haudenhuyse, and Bradt (Citation2019) suggestion to use DeLuca’s (Citation2013) spectrum of social inclusion, including (i) normalising, (ii) integrative, (iii) dialogical, and (iv) transgressive. Normative inclusion refers to the process of assimilation in which non-dominant groups are recognised but not legitimised. Adaptation is a unidirectional process whereby newcomers strive for social inclusion by acquiring the host society’s norms. Integrative inclusion refers to how minority groups are recognised and legitimised. However, there still is a ‘cultural standard’, meaning minorities are implicitly expected to learn and adapt to such a standard (DeLuca, Citation2013 330). In this way, integrative inclusion takes form through targeted interventions and segregated activities and can reinforce divides and structures based on class and ethnicity. However, within the dialogical conception, the dominant group is present but welcomes cultural complexity (DeLuca, Citation2013 332). Accordingly, minorities are not segregated or targeted individually, but attempts are made to transform structural features that enable equal social participation. In the transgressive concept, inclusion takes a more radical form, whereby diversity is used to generate new knowledge and cultural complexity is seen as contributing to new insights. Accordingly, no dominant group exists. It should be clear that the PPCT framework can elucidate the processes that enable social inclusion; however, DeLuca’s (Citation2013) continuum of inclusion allows the analysis to consider which type of inclusion is at stake.

Method

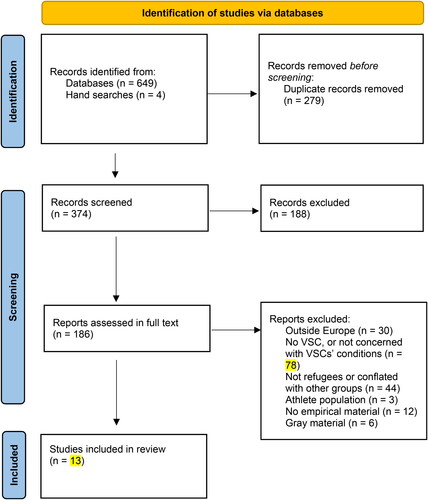

The study was conducted as an integrative review according to the framework provided by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005). Upon initial literature reviews, it became apparent that the scope of the literature was broad, covering diverse perspectives and methodologies. Because of this diversity, we chose to deploy an integrative review according to the standards of Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005). The final review was conducted in April 2022. The review further followed the recommendations by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005). Firstly, the procedure included multiple ways of conducting literature searches (databases, manual searches, back and forward searches, and contact with experts). Secondly, an assessment of the rigour of the selected studies was performed. Finally, data was collected, stored, and formatted so that subsequent data analysis was characterised by ‘…some logical system to facilitate analysis’ (p.550). Regarding the latter, the data analysis was structured according to the PPCT framework, allowing an intuitive understanding of the subject matter’s multifaceted layers.

Inclusion and exclusion

The articles included had to be peer-reviewed and present empirical material in English. Second, the research had to be carried out within a European VSC. Third, the search was delimited to publications in and after 2015, given this year’s role as the major starting point of newcomers’ entry into Europe. This delimitation ensured that the research contained insights informing us of the current state of VSCs’ ability to address such matters of inclusion and integration. Fourth, the included articles had to be concerned with refugees. The included articles thus had to be explicit in their labelling of this group. A key limitation was that ‘refugees’ were often not described further, neither in their characteristics nor the authors’ understanding of ‘refugees’. Given the dominance of UNHCR’s definition of refugees (forcibly displaced across international borders due to war, persecution, and conflict), a rough assumption was made here, assuming that authors utilising the term ‘refugee’ were referring to at least a definition similar to the UNHCR’s. Fifth, the articles had to be concerned with the managerial perspectives and not contain newcomers’ narratives of sport’s contribution (although these play a crucial part) because this exclusion was that a range of reviews have already considered migrants and newcomers’ experiences in sport (e.g. Middleton et al. Citation2020; Smith, Spaaij, and McDonald Citation2019; Spaaij et al. Citation2019).

The excluded articles contained at least one of the following points: (1) did not contain empirical material, (2) were conducted in a non-English language, (3) were conducted outside of the EU (an exception was made to include the UK because of historical and proximity reasons), (4) were carried out outside of a VSC, such as community- or research-driven initiatives (e.g. Kataria and De Martini Ugolotti Citation2022; Mohammadi Citation2019), (5) did not specify refugees as their population of interest but used labels such as ‘immigrants’, ‘migrants’ or ‘ethnic minorities’ without specifying the motive of migration, or conflated refugee populations with other migrant populations so that separate results for refugees were indistinguishable. How sport is experienced across vulnerable groups differs due to the heterogeneity within such groups (Fernández-Gavira, Huete-García, and Velez-Colón Citation2017). Researchers have even made distinctions based on the time intervals of first-generation migrants’ arrival and how this factor affects integration (Dollmann, Jacob, and Kalter Citation2014). In short, we can assume that the realities are different for refugees who flee due to humanitarian crises compared to, e.g. labour migrants. When these criteria were unclear, the author was contacted. It is worth mentioning that the paper’s definition of ‘refugees’ may also have included different policy categories (e.g. asylum-seekers and unaccompanied minors), which could have implications for study results. Finally, articles that did not centre on the managerial aspects of VSCs were excluded. The managerial perspectives could be highlighted through staff or newcomers if the organisational factors of the VSCs were central.

Six databases were searched: ERIC, Scopus, SportDISCUS, PsycINFO, Web of Science (including Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index and Emerging Sources Citation Index) and PubMed. Moreover, back and forward searches on relevant articles were performed. Back and forward searches were also performed concerning four recent reviews on the subject matter of sport and newcomers (Hudson et al. Citation2022; Middleton et al. Citation2020; Smith, Spaaij, and McDonald Citation2019; Spaaij et al. Citation2019) were scanned for additional articles. Finally, hand searches were performed in selected journals (European Journal for Sport and Society, European Journal of Sport Management, Journal of Sport Management, International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, Sport Management Review and Sport in Society). These search phrases, as copied from Scopus, were used:

refugee* OR migrant* OR newcomer* OR “asylum seeker” OR immigrant*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (sport* OR recreation* OR leisure* OR “physical activity”) AND (“Social Inclusion” OR “social integration” OR integration* OR assimilation* OR segregation* OR exclusion* OR “social exclusion”

The included articles are displayed below in .

Table 1. Included studies’ purpose, setting, theory, methodology, and sample.

Results

The results section is structured according to the PPCT framework. First, however, I outline descriptions of the studies and the extent to which VSCs attempt to include newcomers. Subsequently, I account for the individual factors (person) for newcomers and significant individuals within the VSC. Then, the contextual (context) settings are presented, followed by the proximal processes. I will finish by presenting the temporal aspects (time).

Study characteristics

Most studies were conducted in Germany (n = 6), followed by Sweden (n = 2), Denmark (n = 2), the UK (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), and one study conducted in both the Netherlands and Germany (n = 1). These results reflect the migratory movements after 2015, when most newcomers sought respite in Germany, followed by Sweden. Methodologically, ten studies used qualitative methods, two engaged with quantitative assessments, and one study can be considered a mixed-methods study (Anderson et al. Citation2019). In the qualitative studies, a range of methods were applied. The most common were semi-structured interviews (n = 4), a combination of interviews, document analysis, and participant observation (n = 3), interviews complemented with participant observation (n = 2), and one study utilised action research through workshops, preparatory talks, and interviews (n = 1). The quantitative studies (Fingerle et al. Citation2021; Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020) used cross-sectional surveys. The remaining study (Anderson et al. Citation2019) utilised a Delphi design whereby experts filled a questionnaire with open-ended semi-structured questions. After coding, the generated statements were transformed into a quantitative Likert scale and rated by the experts.

The studies were theoretically homogenous, and no study utilised the same theoretical underpinnings as the others. System theories were used, including Luhmann’s theory (Michelini et al. Citation2018) and Bronfenbrenner’s socioecological model (Anderson et al. Citation2019). Meta-theoretical perspectives were also present, including critical realism (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022) and realist evaluations (Michelini and Burrmann Citation2021). Other studies used concepts from the migration literature, including Berry’s acculturation typology (Stura Citation2019) and Essen’s concept of integration (Michelini and Burrmann Citation2021). Other studies analysed the organisation’s logic (Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020) or ‘interests’ (Tuchel et al. Citation2021). Fingerle et al. (Citation2021) referenced the self-determination theory, while Agergaard et al. (Citation2022) used a more critical post-colonial- and transnationalism perspective. Finally, some studies’ theories were fused with their methodological procedures, including discourse analysis (Dowling Citation2020). To summarise this section, most of the research has been conducted in Germany, with qualitative methods, and is theoretically heterogeneous.

To what extent are VSCs making sport accessible for newcomers?

This section reviews if and to what extent VSCs are attempting to include newcomers. Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) found that, out of 5170 German VSCs, 28% perceived themselves to be highly concerned with newcomers’ integration; however, only 14% of the total sample implemented any initiative (e.g. reduced fee or specific activity directed at newcomers). Similarly, the results of Fingerle et al. (Citation2021) support Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020). Fingerle et al. (Citation2021) were concerned with how the newcomers’ needs and preferences corresponded to what the VSCs offered. That is, Fingerle et al. (Citation2021) analysed whether the VSCs were suited to the needs of the newcomers. In this regard, few respondents reported implementing initiatives to ease newcomers’ sporting participation. Only a small minority, 11 out of 84 VSC representatives, indicated that integrative measures are necessary in the current context (such as reduced fees; Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020). In this regard, a palpable discrepancy was found concerning the answers provided by the newcomers; financial and material resources were cited as the top reasons for not participating (Fingerle et al. Citation2021). Although sport for newcomers is frequently mentioned as part of the European government’s agenda, most VSCs do not engage with newcomers.

Person: the significance of the individual(s)

As the forthcoming sections imply, a unified and coherent program delivery seemed critical for VSCs in delivering sports for newcomers. However, this point differs from saying that all members are equally engaged in such initiatives. As Michelini et al. (Citation2018) noted, VSCs are generally formally inclusive, but most do not have an official statute that explicates their aims concerning underrepresented groups. What usually follows is that handling such initiatives becomes the responsibility of a few or even a single ambitious individual (Michelini et al. Citation2018; Tuchel et al. Citation2021). Tuchel et al. (Citation2021) noted that VSCs can often respond with quick turnarounds and creative solutions through these single individuals. One explanation is the need for more directives in statutes and the autonomy of VSCs that enable individuals to pursue things quickly. The spontaneous, individual-based, and at times unorganised and affectional nature of sport delivery for newcomers in VSCs is illustrated well in Blomqvist Mickelsson (Citation2022) study when the sport manager for a VSC met personally with a newcomer and was spurred by an emotional response to the newcomer’s situation. Struck by the vulnerability of this newcomer, the sport manager started a joint initiative between the sport club and a refugee reception centre, offering free training and transport.

Some other examples that reinforce the importance of specific persons are derived from Tuchel et al. (Citation2021), who explored the various forms of sports delivery for newcomers. Specifically, Tuchel et al. (Citation2021) constructed four categories of different sport initiatives, with different actors and settings from their material. Three of the four categories emerging from their work are mainly driven by the VSCs’ individuals, which can, for instance, include initiatives focusing on delivering activities outside of VSCs, where these individuals construct activities at the reception centre. Other activities occur within the VSC, in separated newcomer groups, or are integrated into the existing training structure. These forms have different implications for collaborations and contact between newcomers and VSC members, but all share that individuals drive them.

The individuals who constitute these initiatives’ core are often emotionally affected and driven by a sense of justice (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022; Doidge, Keech, and Sandri Citation2020; Tuchel et al. Citation2021). However, this point is not to say that the outcomes of these actors’ doings are socially just or correspond to their intentions, as other sections will show. Moreover, Michelini et al. (Citation2018, p.28-29) findings led them to conclude that most of these individuals are ‘…already active in the sport club and disposed to social engagement beyond the expectation implied by their positions.’ These individuals’ pre-existing capital and predisposition were further corroborated in Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021) article, as they discovered that all contact persons of these initiatives already had experience and enjoyed support from extensive networks. These findings indicate that the individuals within VSCs generally have a pre-existing sense of social justice and usually have experience with social issues. Accordingly, these ambitious individuals are more likely to have a pre-existing interest in social justice rather than humanitarian crises being a trigger for such interests. As Michelini et al. (Citation2018, 30) state, the ‘…results thus underscore how the individuals behind VSCs are the most powerful engines for the creation of sport offers for refugees.’

Person: VSCs’ ‘othering’ of the newcomers based on sporting capital

The inclusiveness of VSCs was not only reliant on the characteristics of the VSC’s staff but often contingent on the characteristics of the newcomers. In this regard, some authors (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022; Dowling Citation2020; Michelini and Burrmann Citation2021; Stura Citation2019) uncovered how different types of sporting capital excluded newcomers from the VSCs. As Stura (Citation2019) noted, a consistent finding across VSCs was that major challenges arose when the newcomers lacked the sport skill level required by VSCs. This factor had severe implications for how newcomers were supposed to be integrated into the existing structure and, as noted by some respondents in Hertting and Karlefors (Citation2021), most newcomers were excluded from the VSC because of these lacking sport skills. In their analysis of sport programmes, Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021) explored one programme that targeted newcomers. However, one partial reason was to identify talented newcomers that could be integrated into existing teams later.

In this regard, newcomers are usually constructed as ‘…being “in need of” of being taught the “right” skills…’ (Dowling, Citation2020 1159), which seems to serve as a boundary between host society members and newcomers in terms of inclusion. Specifically, Dowling (Citation2020) illustrated, in the Norwegian context, how boundary-making took form through both overt racism and more subtle practices. In this critical interrogation of a VSC with a newcomer initiative, Dowling (Citation2020) explored how newcomers were frequently positioned as ‘others’ both on ethnic and racial features but also regarding their lack of various types of cultural capital. As an illustrative example, Dowling (Citation2020) found that newcomers were often associated with fear-inspired narratives about rape, and a potential threat against the existing youth sport division. In other cases, respondents in Michelini et al. (Citation2018) referenced the perceived temperament of specific newcomers, arguing that bad temperament made them less inclined to play under pressure, and they generally lacked experience in organised sport. In turn, the lack of experience in organised sport was assumed to be related to clumsy motor coordination and flawed skills. The emphasis on not playing ‘right’ or lacking the skills necessary to join a VSC indicates that these informants rejected dialogical concepts of inclusion, in which the structure is altered, instead of focusing on the individual level. In this sense, when sport’s competitive logic remains unaddressed and unaltered, it may obscure the goals of VSCs’ social inclusion initiatives.

Context: human and financial resources

Human resources

The second most robust predictor of supporting newcomers’ inclusion into German VSCs in Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) was human resources. This factor included, for example, the number of volunteers and whether VSCs had a paid board member (Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020). In addition to Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) quantitative findings, Michelini et al. (Citation2018) respondents also confirmed the significance of this particular factor. This factor emerged as the most crucial and gained the highest consensus score among sport-and-integration experts in Anderson et al. (Citation2019, 86) study. The identified factor is expressed in the statement, ‘More facilitators with skills, e.g. sport, culture, language’. This alignment across multiple studies underscores the importance of this factor in the context of sports and integration efforts. This finding is not surprising, as previous sections illuminate the burden of a few individuals in this line of work.

Financial resources

Financial resources became a crucial element in the delivery of sports for newcomers since a range of measurements are necessary to involve newcomers in VSCs. These can include reduced or eliminated membership fees (Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer Citation2020), but the problem is also pertinent regarding newcomers’ lack of material resources. Specifically, a range of authors have reported that the newcomers often lacked the appropriate equipment to partake adequately, which needed to be addressed through financial means (Michelini and Burrmann Citation2021; Stura Citation2019; Tuchel et al. Citation2021). VSCs, in response, are urged to allocate sufficient financial resources to address these challenges effectively. By doing so, VSCs not only contribute to fostering equity in access but also enhance the overall success of sports programs in integrating newcomers into the community.

Proximal processes: linking institutional logics and organisational culture to the practices

The proximal processes in this context link the individuals (notably the VSC staff) to the contextual factors that enable them to work satisfactorily. Accordingly, this section should be read while keeping in mind that the culture and logic within VSCs are ‘carried’ by their individuals. The reciprocal nature of this relationship is further discussed here.

Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) concluded their comprehensive analysis by offering a clear takeaway from their paper in the form of the two most powerful predictors of VSCs’ engagement with newcomers: institutional logic and human resources capacity. The one variable with the most power to explain VSCs’ inclination toward newcomers is their logic. These logics have undergone different operationalisations but converge in whether the VSCs conceive of themselves as actors in addressing social issues or if conventional and well-established logics, such as competition, guide them. In all proposed models, institutional logic constitutes over 40% of the relative variance explained and over 6% in absolute variance. Naturally, the institutional logic can be viewed as an umbrella concept that encapsulates and permeates the practices within the VSC.

In this regard, organisational culture was also a prominent theme in various articles (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022; Doidge, Keech, and Sandri Citation2020; Dowling Citation2020; Michelini et al. Citation2018; Stura Citation2019). Connected with Nowy, Feiler, and Breuer (Citation2020) typology of logics, Doidge, Keech, and Sandri (Citation2020) found that VSCs need to be unified in a common vision that is foregrounded in a social justice and social inclusion agenda if sport delivery for newcomers seeks to be successful in fostering a sense of belonging for newcomers with their newly found community. This philosophy entailed downplaying competitive elements and constructing a pleasant and socialising atmosphere. These philosophies permeated the practices of the VSC, which ensured a high quality of sport delivery. At its core, these practices and philosophies allowed diverse individuals to interact and co-exist in the sport environment because diversity was embraced. In this regard, the case of Doidge, Keech, and Sandri (Citation2020) aligns better with a dialogical concept of inclusion, as cultural diversity was actively recognised as something positive. Importantly, the synergy between the significant individuals in the context (VSC staff) and the organisational culture and logic constitutes the proximal process that enables the VSC to achieve social inclusion.

Relatedly, a minority of Stura’s (Citation2019) sample highlighted how the newcomers taught the VSCs important things and made them more aware, tolerant, and open to other peoples’ perspectives. However, most respondents emphasised the newcomers’ adaptation along the lines of norms and traditions and reciprocal trust between both sides. A minority of the respondents said they had not learned anything from the newcomers. In summary, Doidge, Keech, and Sandri (Citation2020) and partially Stura’s (Citation2019) work illuminated how some VSCs adopt a more nuanced concept of social inclusion but that most fluctuate between the normative and the integrative concepts.

Interestingly, in Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021) study, trainers displayed frustration and irritation with newcomers’ late arrival and unpredictability, which was addressed by arranging set expectations, fixed groups, and ensuring commitment from newcomers. These arrangements ensured that the VSCs ‘… achieve the corresponding goals as conceived (e.g. conflict and aggression reduction)’ from the VSCs’ perspective (Michelini and Burrmann,Citation2021 271). In this sense, social inclusion is conceived of as an outcome that can be achieved through steering newcomers into fixed commitments and ensuring that undesirable characteristics are combated so that further integration can be made into VSCs. The trainers’ ambition and consistency, combined with their effort to ensure a high-quality sport delivery, has the potential to achieve social inclusion; however, it is not the same type as achieved by Doidge, Keech, and Sandri (Citation2020). In this regard, Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021) drew from Essen’s concept of integration, postulating that integration is multidimensional (social, cultural, structural, and emotional). Thus, some VSCs could perceive combating any assumed and existing antisocial behaviour as a starting point to achieve social integration and feelings of belonging. Although briefly illustrated, this point somewhat indicates a displacement of scope, where structural issues are conceived of as the root of the cause, but where VSCs usually encourage disregarding the structural issues and encouraging individuals to adapt (Ekholm Citation2017).

Moreover, a lack of a coherent vision within VSCs or an exclusionary culture showed several detrimental outcomes. One salient exclusionary mechanism was how VSC members engaged in ‘boundary-making’ (Michelini et al. Citation2018). This practice entailed how members drew symbolic divides between host society members and newcomers, suggesting that several critical differences inhibit their inclusion into the VSCs. For example, when talking about the newcomers, Michelini et al. (Citation2018, 31) respondents drew from evolutionary perspectives, arguing that, for example, in the context of conflicts in the VSC, that ‘…if you haven’t developed certain competencies at the top, you go back to primitive measures. Then you think like in the animal world’. These sentiments suggest that newcomers have not developed the same social competencies, which hinders their inclusion. Other findings revealed a rather static idea of newcomers ‘ adaptation. Blomqvist Mickelsson (Citation2022) found that the VSC expected the newcomers to adapt to the VSC culture, but VSC staff contended that they seemed disinclined. When the original fees were introduced after a period of reduced fees, the VSC staff argued that the newcomers who ‘really’ wanted to stay stayed. Considering Fingerle et al. (Citation2021) findings regarding the lack of financial resources, it is unsurprising that only one newcomer remained in the VSC after the financial assistance was removed. The main takeaway from Blomqvist Mickelsson (Citation2022) is that very little consideration was given to the newcomers’ perspective on inclusion into VSCs.

Collaborative efforts

Collaborative efforts were often made between VSCs and external actors in the public and voluntary sectors. This point is logical considering the VSCs’ unpredictable qualifications to recruit and navigate newcomer initiatives.

In terms of recruiting newcomers, one mechanism that facilitated participation in Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021) study was the contact with reception centres and the transportation arrangement, corroborated by Anderson et al. (Citation2019) experts. Other fruitful collaborations were initiated with the Red Cross, which could provide material resources to the newcomers to facilitate sport participation (Tuchel et al. Citation2021). Moreover, since the newcomers were unfamiliar with the VSCs and the people there, questions remained about developing relationships characterised by trust. As Tuchel et al. (Citation2021) noted, one key factor was the social worker who accompanied newcomers to their activities in a systematic manner and worked as a confidante. Accordingly, such officials may serve as a temporal bridge between newcomers and VSCs in transition.

While intersectoral collaborations are intuitively beneficial to VSCs, which may lack resources and knowledge, this finding is perhaps not the most novel or interesting. In this sense, ‘collaborative efforts’ took on another meaning in the study by Simonsen and Ryom (Citation2021), who engaged in a participatory action research project with a local VSC, the municipality, and female Syrian newcomers. Simonsen and Ryom’s study illuminates the importance of engaging with the target group—for instance, facilitating preparatory talks and workshops and having a dialogue about sports proposals. Simonsen and Ryom (Citation2021) found that VSCs (and municipalities) have historically experienced a discrepancy in expectations when engaged with newcomers. The VSC representative argued that these discrepancies arose because of different ideas about sport, which can hamper newcomers’ inclusion. This point could, for example, include punctuality, which was deemed a ‘German virtue’ that newcomers preferably acquired in Stura’s (Citation2019) study. By probing the terrain and engaging directly with the female newcomers, the VSC was more prepared to deliver sport in the desired way. This point resonates well with Michelini and Burrmann (Citation2021, 227) conclusions in the analysis of several sport programmes, that VSCs too rarely involve newcomers in the construction of activities, which is probably due to the ‘…difficulty of surrendering control, responsibility and, consequently, power’. In summary, while collaborations with external actors are necessary to ensure that VSCs can deliver and maintain initiatives, there is a pertinent need and practical utility to engage collaboratively with the target group directly.

Proximal processes: newcomers’ volunteering engagement as a further mechanism of inclusion or exclusion

Due to the unstable nature of forced migration, e.g. unstable housing situations, permits to stay, working conditions, and much more (Ager and Strang Citation2008), many articles touched upon the possibility but the difficulty of having newcomers as volunteers. Many VSC representatives conceived of this issue as rooted in newcomers’ perceived lack of cultural capital, linguistic skills, and inexperience in volunteering. This ‘othering’ framing of newcomers seemed to be foregrounded in VSC representatives’ belief in the newcomers’ unwillingness to adapt to a more collectivistic ‘me-for-all’ culture. This point was, in turn, framed as a self-exclusionary mechanism by many VSC representatives (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2022; Michelini et al. Citation2018). Both Blomqvist Mickelsson (Citation2022) and Michelini et al. (Citation2018) noted that these sentiments are rarely coupled with deeper insights into how difficult it might be to attain volunteering positions and, in general, how little thought is given to the newcomers’ perspective on the subject matter.

Other VSCs have a slightly different perspective, as they wish newcomers to partake in ‘simple’ volunteer engagements but deem more advanced volunteering tasks inappropriate. For example, in Stura (Citation2019), the main issue cited was the need for more linguistic knowledge. VSC representatives feel that it would not be possible for newcomers to do an efficient job in certain positions. Accordingly, this point tells of stratification within VSCs where ‘lower-bound’ positions are encouraged as appropriate for newcomers, whereas the traditional members operate in higher positions. In this regard, apart from the somewhat exclusionary nature of this stratification, some VSCs understand that ‘… inclusive engagement for refugees is not only a challenge or burden for VSCs but can also provide fruitful impulses for new developments …’ including an increased volunteer base (Tuchel et al. Citation2021, 687). In this regard, VSCs that recruit newcomers as sport coaches, which was the case occasionally (Tuchel et al. Citation2021), can solve the puzzle of working with newcomers’ social inclusion in parallel with addressing a lack of human resources.

However, other examples also elucidate how the transfer of responsibility within certain tasks can induce agency and empowerment. Regarding newcomers’ preference for cricket, a relatively unknown sport in Germany, Michelini et al. (Citation2018) found that certain VSCs encouraged newcomers to share their own sports offerings. Michelini et al. (Citation2018) suggested that leveraging such offers for and by newcomers indicates that this transfer of responsibility is greatly useful for newcomers’ engagement in voluntary work and further engagement with the VSC. In this sense, Agergaard et al. (Citation2022) offered a critical perspective on volunteering, showing that the newcomer women in their study utilised volunteering partially to become part of the Danish system, but also to some extent implicitly challenging ‘… volunteering as a particularly “Danish thing”’ (629). These women held their own interpretation of volunteering, went beyond volunteering for the VSC, and helped refugees in other areas. One conclusion put forth by Agergaard et al. (Citation2022) is that if newcomers can help in any way they can, barriers between ‘us’ and ‘them’ are more likely to diminish significantly.

The above findings resonate well with the previous section that elucidates the need to engage directly with newcomers, and it challenges the dominant stratification of volunteering positions within VSCs, showing that newcomers can make unique and culturally specific contributions to the VSCs (e.g. knowledge of cricket or understanding of other newcomers’ experiences). To this extent, it is more valuable to adopt a structural approach, realising that VSCs must be the main drivers in offering suitable opportunities for newcomers.

Time

One assumption that underpins previous findings is that the relationships between VSCs, newcomers, and external actors are nurtured over time. In other words, newcomers’ one-time participation in activities does not achieve social inclusion, and collaborations are rarely successful if they do not consider the sustainability of such collaborations. For instance, asylum waiting processes and being transferred between different housing may severely impact newcomers’ long-term sporting participation since such procedures imply uncertainty and geographical mobility. Tuchel et al. (Citation2021) found that VSCs were inclined to construct activities close to reception centres, but a critical issue emerged when newcomers were re-located as part of their settlement process (Anderson et al. Citation2019; Tuchel et al. Citation2021).

Moreover, the historical feature of time was revealed as important to certain VSCs’ practices and impact. Since most of the included research in this review was based in Germany, there is much reference to the inception of Willkommenskultur (‘welcome culture’) and how this culture may have been partially disrupted as part of events in Germany after the reception of newcomers during the so-called refugee crisis. First, Willkommenskultur refers to the culture and atmosphere that arose as newcomers entered Germany when a rather philanthropic sentiment permeated many parts of Germany, including (some) VSCs. For instance, under the banner of the project ‘Willkommen im Sport’ (Welcome to Sport) by the Germany Olympic Sports Confederation, 200 clubs were funded and participated in working with newcomers (Tuchel et al. Citation2021). Initially, many VSCs reported an enthusiastic atmosphere, and a sense of solidarity spurred this culture (Michelini et al. Citation2018). However, one significant event occurred on New Year’s Eve (2015/2016), when women were sexually assaulted by attackers who included asylum-seekers. The media narratives of newcomers generally changed across Europe after this event (Michelini et al. Citation2018), and it also seemed to impact the VSCs. For example, Michelini et al. (Citation2018) found that there were decreases in funding for initiatives, and some VSCs experienced elevated member concerns. Michelini et al. (Citation2018) further stated that awareness-raising was carried out in some VSCs to prevent relationships between newly arrived newcomers and host society (VSC) members from being characterised by fear and prejudice.

Discussion

European VSCs have a strong societal position and an immense potential to address social issues. However, this review has synthesised and shown that various issues impede VSCs’ ability to facilitate newcomers’ social inclusion. These issues are interrelated and include VSCs’ (lacking) understanding of social inclusion, their organisational culture, and the consequences of the practices and outcomes of those mentioned above.

Notably, most VSCs understand inclusion according to a normative or integrative concept in which the dominant group sets the standard. Many VSCs understand that, for example, psychological safety and trust are imperative to building relationships; however, the intended outcomes are often entangled in the newcomers’ acquisition of language, norms, etc. Such acquisition is not bad per se and can most likely mediate newcomers’ inclusion and well-being; however, when these concepts start to mimic complete assimilation (i.e. go from integrative to normative), they may threaten newcomers’ identity and create imagined divides. In this sense, the dominant frameworks on migrants’ integration have often linked complete assimilation, especially under the circumstances pertinent to newcomers (e.g. poverty), to suboptimal well-being (Portes and Zhou Citation1993). Portes and Zhou’s argument here is that a complete rejection of ethnic and cultural identity may cause ruptures between migrants and ‘their’ communities, which may be harmful to their psychological and social health.

Moreover, such approaches fail to consider newcomers’ strengths and the learning opportunities that exist on behalf of the host society. Schaillée, Haudenhuyse, and Bradt (Citation2019) noted that few sport actors seem aware of how newcomers can contribute with their strengths. This factor points to a broader feature of civil society’s involvement—the lack of intercultural education and qualifications and the, perhaps, overreliance on ambitious but unqualified individuals to address social issues. Since volunteering is indeed linked to higher degrees of migrants’ social integration (Adler Zwahlen, Nagel, and Schlesinger Citation2018), there is a pertinent need to explore this dimension further. Such exploration can be done vis-à-vis adopting a more strength-based approach to newcomers’ volunteering. As illuminated by Michelini et al. (Citation2018), newcomers may have unique contributions, such as understanding preferences for sports that are not necessarily exercised overly much in the host country’s context (for instance, see the example of cricket in Germany). Other important works are Agergaard et al. (Citation2022) and Block and Gibbs (Citation2017), which show that volunteering newcomers and migrants are better positioned to establish trust with other newcomers outside the VSCs because these individuals understand other newcomers’ situations differently. In short, if VSCs do not conceive of newcomers as ‘problems to be solved’ and instead draw from their strengths, a sense of empowerment can be induced on behalf of the newcomers in parallel to the increased functioning of VSCs. In most cases, this point will require a general re-orientation in the perception of newcomers and that VSCs can ‘give up’ some of their power.

Secondly, the foundation of understanding newcomers’ ‘social inclusion’ shapes the practices and plausibly which organisational culture encapsulates the practices. One salient finding in the reviewed materials is that while financial resources are important, they are secondary to the individuals who run the initiatives. A coherent vision and a welcoming atmosphere, in which little attention is paid to competition, seem crucial for newcomers’ inclusion. The scope of the VSCs is indeed a crucial factor and is not only limited to whether they centre on competition or inclusion. In this regard, Koopmans and Doidge (Citation2022) offered some valuable insights, arguing that sport actors should be less concerned with instrumental goals (e.g. health) and more interested in the joy that sport can bring. This point also resonates with recent findings on target populations’ perspectives on the outcomes and meanings of sport initiatives, where fun seems to foreground the experience (Ekholm and Dahlstedt Citation2022). This review also suggests that few VSCs adopt a more relaxed vision of ‘fun’ but focus on means and markers of inclusion and integration, such as language, health, and norms (Ager and Strang Citation2008). In this regard, ethno-specific sports clubs and initiatives are usually ‘safe havens’ with little focus on instrumental social policy goals—however, such initiatives are also often subject to negative political attention, assuming that such spaces are ‘parallel societies’ (Lenneis and Agergaard Citation2018). In light of such broader political sentiments, it is not surprising that most VSCs adopt a normative or integrative approach to social inclusion.

While this paper has systematically reviewed VSCs specifically, it should be noted that VSCs should not necessarily be regarded as how newcomers partake in sport. Recently, informal sport settings outside of the mainstream sport sphere have been raised as a potential and valuable alternative (Alemu, Vehmas, and Nagel Citation2021). A more critical assessment of VSCs, as evident in this review, reveals a range of assimilatory and potentially problematic practices that impede newcomers’ inclusion. In this regard, it is imperative not only to assess how ‘successful’ VSCs operate but also to understand that VSCs should not represent a definitive status quo. Newcomers’ non-attendance can be a sign of social closure within VSCs, but it can also signal newcomers’ agency, i.e. their choice to not partake in mainstream society sport. Moreover, since many sport federations and larger authorities decide upon the value and direction that VSCs should proceed in, it is an issue that needs to be addressed at levels above the VSC (Blomqvist Citation2022). To this end, VSCs can be limited in their capacity to address structural issues, but they are still autonomous and within their rights to decide as they see fit within their own space.

Moreover, this paper is framed in light of the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine. How the European sport movement will respond, but the included articles are primarily based on non-Ukrainian newcomer populations. A critical debate has emerged in Europe, as it seems that Ukrainian newcomers are received differently and better than other newcomer populations. De Coninck (Citation2022) recently suggested that ethnicity and geographical proximity could factor in this differentiated treatment. There is no reason to believe sport clubs are spared from this double standard; exploring the lived experiences of African and Polish migrants in the UK, Long, Hylton, and Spracklen (Citation2014) found that Polish migrants, being a non-visible ethnic minority, seemed to experience less stigmatisation than African migrants. Sport clubs are also arenas where race, ethnicity, class, and sex intersect in the broader making of internal hierarchies that impinge upon newcomers’ reception. Recent research into the subject matter also shows that Ukrainian newcomers may be better received because they may have extensive experience in organised sport, which is at the core of European sport movements (Blomqvist Mickelsson Citation2023). Such intersections must be further explored in light of the ongoing differentiated treatment of Ukrainian newcomers.

This review has several limitations. One limitation is the use of English literature—this point effectively excludes all works produced in the German language, where more research on the subject matter may exist. Secondly, another limitation is the omission of a large body of research that did not clearly define what ‘migrant’ entailed. For instance, a large body of impressive research has emerged from the SIVSCE project (Elmose-Østerlund et al. Citation2017). However, the SIVSCE project makes no mention of reasons for migration. Third, and related to the above, even when newcomers (i.e. refugees) are distinguished from migrants, newcomers are also heterogeneous. Refugee background is only one part of an individual’s identity; other factors we know condition sport participation and inclusion are gender. By invoking a more intersectional lens, we may be better positioned to understand the vividly differing experiences of newcomers. This factor was, however, outside of the review’s scope. Relatedly, it finally emphasises that this review centred on the VSCs’ perspective and omitted newcomers’ experiences. However, since many prior reviews have already done this, narrowing the scope seemed appropriate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The refugee crisis is a problematic definition, but given the lack of other established terms for this event, it will be referred to as above.

References

- Adler Zwahlen, J., S. Nagel, and T. Schlesinger. 2018. “Analysing Social Integration of Young Immigrants in Sports Clubs.” European Journal for Sport and Society 15 (1): 22–42. doi:10.1080/16138171.2018.1440950.

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191. doi:10.1093/jrs/fen016.

- Agergaard, S. 2011. “Development and Appropriation of an Integration Policy for Sport: How Danish Sports Clubs Have Become Arenas for Ethnic Integration.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 3 (3): 341–353. doi:10.1080/19406940.2011.596158.

- Agergaard, S. 2018. “Rethinking Sports and Integration: Developing a Transnational Perspective on Migrants and Descendants in Sports.” Rethinking Sports and Integration: Developing a Transnational Perspective on Migrants and Descendants in Sports 2 (1): 1–116. doi:10.4324/9781315266084.

- Agergaard, S., J. K. Hansen, J. S. Serritzlew, J. T. Olesen, and V. Lenneis. 2022. “Escaping the Position as ‘Other’: A Postcolonial Perspective on Refugees’ Trajectories into Volunteering in Danish Sports Clubs.” Sport in Society 25 (3): 619–635. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2017822.

- Alemu, B. B., H. Vehmas, and S. Nagel. 2021. “Social Integration of Ethiopian and Eritrean Women in Switzerland through Informal Sport Settings.” European Journal for Sport and Society 18 (4): 365–384. doi:10.1080/16138171.2021.1878435.

- Anderson, A., M. A. Dixon, K. F. Oshiro, P. Wicker, G. B. Cunningham, and B. Heere. 2019. “Managerial Perceptions of Factors Affecting the Design and Delivery of Sport for Health Programs for Refugee Populations.” Sport Management Review 22 (1): 80–95. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.015.

- Berry, J. W. 1997. “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology 46 (1): 5–34. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

- Block, K., and L. Gibbs. 2017. “Promoting Social Inclusion through Sport for Refugee-Background Youth in Australia: Analysing Different Participation Models.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 91–100. doi:10.17645/si.v5i2.903.

- Blomqvist, T. M. 2022. “The role of the Swedish Sports Confederation in delivering sport in socioeconomically deprived areas.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 14 (4): 589–606.

- Blomqvist Mickelsson, T. 2022. “A Morphogenetic Approach to Sport and Social Inclusion: A Case Study of Good Will’s Reproductive Power.” Sport in Society 26 (5): 837–853. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2069013.

- Blomqvist Mickelsson, T. 2023. “Ukrainian refugees’ reception in Swedish sports clubs: ‘deservingness’ and ‘promising victimhood’.” European Journal of Social Work 27 (2): 267–280. doi:10.1080/13691457.2023.2196375.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–531. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard university press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- De Coninck, D. 2022. “The Refugee Paradox During Wartime in Europe: How Ukrainian and Afghan Refugees Are (Not) Alike.” International Migration Review 57 (2): 578–586.

- DeLuca, C. 2013. “Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Educational Inclusivity.” Canadian Journal of Education 36 (1): 305–347.

- Doidge, M., M. Keech, and E. Sandri. 2020. “Active Integration’: sport Clubs Taking an Active Role in the Integration of Refugees.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 12 (2): 305–319. doi:10.1080/19406940.2020.1717580.

- Dollmann, J., K. Jacob, and F. Kalter. 2014. Examining the Diversity of Youth in Europe. A Classification of Generations and Ethnic Origins Using CILS4EU Data (Technical Report ) (No. 156). Mannheim: Mannheimer Zentrum für Europäische Sozialforschung.

- Dowling, F. 2020. “A Critical Discourse Analysis of a Local Enactment of Sport for Integration Policy: Helping Young Refugees or Self-Help for Voluntary Sports Clubs?” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 55 (8): 1152–1166. doi:10.1177/1012690219874437.

- Dukic, D., B. McDonald, and R. Spaaij. 2017. “Being Able to Play: Experiences of Social Inclusion and Exclusion Within a Football Team of People Seeking Asylum.” Social Inclusion 5 (2): 101–110. doi:10.17645/si.v5i2.892.

- Ekholm, D. 2017. “Mobilising the sport-based community: The construction of social work through rationales of advanced liberalism.” Nordic Social Work Research 7 (2): 155–167.

- Ekholm, D., and M. Dahlstedt. 2022. “Conflicting Rationalities of Participation: Constructing and Resisting ‘Midnight Football’as an Instrument of Social Policy.” Sport in Society 25 (6): 1142–1159. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2064098.

- Elmose-Østerlund, K., B. Ibsen, S. Nagel, and J. Scheerder. 2017. Explaining Similarities and Differences Between European Sports Clubs: An Overview of The Main Similarities and Differences Between Sports Clubs in Ten European Countries and the Potential Explanations. Odense: University of Southern Denmark.

- Fahlén, J., and C. Stenling. 2016. “Sport policy in Sweden.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 8 (3): 515–531. doi:10.1080/19406940.2015.1063530.

- Fernández-Gavira, J., Á. Huete-García, and L. Velez-Colón. 2017. “Vulnerable Groups at Risk for Sport and Social Exclusion.” Journal of Physical Education and Sport 17 (1): 312–326. doi:10.7752/jpes.2017.01047.

- Fingerle, M., M. Röder, K. Olmesdahl, and J. Haut. 2021. “Matching Perspectives of Refugees and Voluntary Sports Clubs in Germany.” Italian Sociological Review 11: 715–735.

- Hertting, K., and I. Karlefors. 2021. “‘We Can’t Get Stuck in Old Ways’: Swedish Sports Club’s Integration Efforts with Children and Youth in Migration.” Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research 92 (1): 32–42. doi:10.2478/pcssr-2021-0023.

- Hudson, C., C. Luguetti, R. Spaaij, and C. Hudson. 2022. “Pedagogies Implemented with Young People with Refugee Backgrounds in Physical Education and Sport : A Critical Review of the Literature of the Literature.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 14 (1): 21–40. doi:10.1080/25742981.2022.2052330.

- Ioffe, Y., I. Abubakar, R. Issa, P. Spiegel, and B. N. Kumar. 2022. “Meeting the Health Challenges of Displaced Populations from Ukraine.” Lancet (London, England) 399 (10331): 1206–1208. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00477-9.

- Kataria, M., and N. De Martini Ugolotti. 2022. “Running for Inclusion: Responsibility, (Un)Deservingness and the Spectacle of Integration in a Sport-for-Refugees Intervention in Geneva, Switzerland.” Sport in Society 25 (3): 602–618. doi:10.1080/17430437.2022.2017820.

- Koopmans, B., and M. Doidge. 2022. “They Play Together, They Laugh Together’: Sport, Play and Fun in Refugee Sport Projects.” Sport in Society 25 (3): 537–550. 10.1080/17430437.2022.2017816.

- Lenneis, V., and S. Agergaard. 2018. “Enacting and Resisting the Politics of Belonging through Leisure. The Debate About Gender-Segregated Swimming Sessions Targeting Muslim Women in Denmark.” Leisure Studies 37 (6): 706–720. doi:10.1080/02614367.2018.1497682.

- Long, J., K. Hylton, and K. Spracklen. 2014. “Whiteness, Blackness and Settlement: Leisure and the Integration of New Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (11): 1779–1797. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2014.893189.

- Michelini, E. 2021. “The Representation of the ‘Refugee Crisis’ and ‘Sport’in the German Press: An Analysis of Newspaper Discourse.” European Journal for Sport and Society 18 (3): 265–282. 10.1080/16138171.2021.1930945.

- Michelini, E., and U. Burrmann. 2021. “A Preliminary Impact Model for the Integration of Young Refugees through Sports Programmes.” Culture e Studi Del Sociale 6 (2): 265–281.

- Michelini, E., U. Burrmann, T. Nobis, J. Tuchel, and T. Schlesinger. 2018. “Sport Offers for Refugees in Germany. Promoting and Hindering Conditions in Voluntary Sport Clubs.” Society Register 2 (1): 19–38. doi:10.14746/sr.2018.2.1.02.

- Middleton, T. R. F., B. Petersen, R. J. Schinke, S. F. Kao, and C. Giffin. 2020. “Community Sport and Physical Activity Programs as Sites of Integration: A Meta-Synthesis of Qualitative Research Conducted with Forced Migrants.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 51: 101769. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101769.

- Mohammadi, S. 2019. “Social Inclusion of Newly Arrived Female Asylum Seekers and Refugees through a Community Sport Initiative: The Case of Bike Bridge.” Sport in Society 22 (6): 1082–1099. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1565391.

- Nagel, S., K. Elmose-Østerlund, B. Ibsen, and J. Scheerder. 2020. Functions of Sports Clubs in European Societies. Springer.

- Nowy, T., and C. Breuer. 2019. “Facilitators and Constraints for a Wider Societal Role of Voluntary Sports Clubs–Evidence from European Grassroots Football.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 11 (4): 727–746. doi:10.1080/19406940.2019.1630469.

- Nowy, T., S. Feiler, and C. Breuer. 2020. “Investigating Grassroots Sports’ Engagement for Refugees: Evidence From Voluntary Sports Clubs in Germany.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 44 (1): 22–46. 10.1177/0193723519875889.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96. doi:10.1177/0002716293530001006.

- Schaillée, H., R. Haudenhuyse, and L. Bradt. 2019. “Community Sport and Social Inclusion: International Perspectives.” Sport in Society 22 (6): 885–896. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1565380.

- Simonsen, C. B., and K. Ryom. 2021. “Building Bridges: A Co-Creation Intervention Preparatory Project Based on Female Syrian Refugees’ Experiences with Physical Activity.” Action Research 21 (4): 382–401. doi:10.1177/14767503211009571.

- Smith, R., R. Spaaij, and B. McDonald. 2019. “Migrant Integration and Cultural Capital in the Context of Sport and Physical Activity: A Systematic Review.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 20 (3): 851–868. doi:10.1007/s12134-018-0634-5.

- Spaaij, R., J. Broerse, S. Oxford, C. Luguetti, F. McLachlan, B. McDonald, B. Klepac, L. Lymbery, J. Bishara, and A. Pankowiak. 2019. “Sport, Refugees, and Forced Migration: A Critical Review of the Literature.” Frontiers in Sports and Active Living 1: 47. doi:10.3389/fspor.2019.00047.

- Stura, C. 2019. “What Makes Us Strong”–the Role of Sports Clubs in Facilitating Integration of Refugees.” European Journal for Sport and Society 16 (2): 128–145. doi:10.1080/16138171.2019.1625584.

- Truskewycz, H., M. Drummond, and R. Jeanes. 2022. “Negotiating Participation: African Refugee and Migrant Women’s Experiences of Football.” Sport in Society 25 (3): 582–601. doi: 10.1080/17430437.2022.2017819.

- Tuchel, J., U. Burrmann, T. Nobis, E. Michelini, and T. Schlesinger. 2021. “Practices of German Voluntary Sports Clubs to Include Refugees.” Sport in Society 24 (4): 670–692. doi:10.1080/17430437.2019.1706491.

- Tudge, J. R. H., I. Mokrova, B. E. Hatfield, and R. B. Karnik. 2009. “Uses and Misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory of Human Development.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 1 (4): 198–210. doi:10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x.

- UNHCR. 2021. “Syria Refugee Crisis – Globally, in Europe and in Cyprus – UNHCR Cyprus.” https://www.unhcr.org/cy/2021/03/18/syria-refugee-crisis-globally-in-europe-and-in-cyprus-meet-some-syrian-refugees-in-cyprus/

- UNHCR. 2022. “Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation.” https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

- Whittemore, R., and K. Knafl. 2005. “The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 52 (5): 546–553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x.

- WHO Europe. 2022. Ukraine Crisis. Public Health Situation Analysis - Refugee-Hosting Countries (17 March 2022). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.