Abstract

Currently, no systematic review exists on dance therapy studies for treatment resistant depression. We conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effects of dance therapy on the primary symptom clusters of treatment resistant depression, that is, co-morbid stress and depression PROSPERO(CRD42022309685), and identify common dance therapy practices in this population. We searched six databases between January 2001 and March 2024 using the primary key terms: ‘dance therapy’, ‘stress’, ‘depression’, ‘study’, ‘treatment resistance’, and ‘adults’. Reference list checks and citation tracking were conducted. The Downs and Black checklist was used to assess risk of bias. Our search yielded 68 records. Five articles were included (N = 613, 91.2% female), and dosage varied between 15 and 24 h over 3–12 weeks. Results indicated an increase in management strategies rather than symptom reduction. Meta-analyses revealed no statistically significant results for stress and depression. Common dance therapy practices were improvisation, shared rhythm, and structured movement.

Introduction

Stress and depression are distinct experiences with symptomatic overlap like chronic fatigue, hypervigilance, and medically unexplained pain, etc. (Gros et al., Citation2012), likely due to their shared biochemistry, such as increased cortisol levels, slower functioning of reproductive hormones, and insulin resistance (Gold et al., Citation2015). Further, stress and depression have a compounding effect on one another (Koutsimani et al., Citation2019) and activate the sympathetic nervous system in diverse ways. Acute stress can cause hyper-arousal motivation and irritation (Blechert et al., Citation2007). In contrast, chronic stress and depression can cause hypo-arousal, presenting as rumination, numbness to emotions, and disinterest in social engagements (De Mutiis et al., Citation2015).

Treatment resistant depression (TRD) is a condition where the dominant symptom clusters can be categorised under depressive and acute stress disorders (Gold et al., Citation2020). The persistence of depressive symptoms in TRD typically aggravates stress, creating a vicious cycle of comorbidity, thus creating a barrier to productivity, employability, and healthy quality of life, along with amplifying psychological burden (Rosen et al., Citation2020). Consequently, this creates the need for a regulated nervous system in TRD. Dance therapy (also synonymously used with Dance/Movement Psychotherapy and Dance/Movement in healthcare) can help ease such psychological stress by regulating the nervous system based on key neurobiological underpinnings (Grasser & Javanbakht, Citation2021) that enable its use to promote sustained aerobic activity, neuroplasticity, cardiovascular health (Wu et al., Citation2022), improvements in memory and cognition (Wu et al., Citation2021), spatial effort synchrony, and stress management (Bräuninger, Citation2014). Psychological flexibility (Ramaci et al., Citation2019), embodied self-expression, emotional resilience (Serlin, Citation2020) and self-regulation (Seoane, Citation2016) have also been identified as potential benefits of dance therapy, all of which can help support a dysregulated nervous system in TRD.

At the time of conceptualising this study, we noted a growing body of literature on dance therapy for stress and/or depression but no registered or published systematic reviews with our keyword combination. For depression, we found three unpublished reviews registered with PROSPERO and the following Cochrane reviews, indicating inconclusive effects (Goldbeck et al., Citation2014; Meekums et al., Citation2015); no effect (Bradt et al., Citation2015) and slight positive effect (Karkou et al., Citation2023) of dance therapy on depressive symptoms. Another review found no effect of dance therapy on stress (Bradt et al., Citation2015); two reviews were deemed empty due to a lack of eligible studies (Broderick & Vancampfort, Citation2019; Karkou & Meekums, 2017), and another (Goldbeck et al., Citation2014) obtained insufficient results to make any conclusions. Further, we did not find systematic reviews that specifically collated/reviewed the types of dance therapy practices relevant to the comorbidity of stress and depression but instead primarily focussed only on determining the effectiveness of dance therapy on stress and depression reduction. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on dance therapy practices with adults experiencing comorbid stress and depression (critical aspects of TRD) to answer the following research questions:

Does dance therapy reduce stress in adults experiencing depression?

Does dance therapy reduce depressive symptoms in adults experiencing depression?

What common practices are used by dance therapists while working with adults experiencing both stress and depression?

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO on 15 March 2022 [CRD42022309685] with two amendments. Our methodology followed Popay et al. (Citation2006)’s five key steps: (i) identifying the review focus, (ii) specifying the research questions, (iii) data extraction and quality appraisal, (iv) narrative synthesis, and (v) reporting on the results obtained, closely following the PRISMA checklist (see below).

Only material published in English between January 2001 and March 2024 was considered for inclusion. We conducted a systematic, advanced literature search on six databases: (i) MEDLINE, (ii) PsycINFO, (iii) the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, (iv) the World Health Organization’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform, (v) Google Scholar, and (vi) ProQuest (for grey literature). The following journals were manually searched: Arts and Health, The Arts in Psychotherapy, and the American Journal of Dance Therapy.

Search terms

The Boolean search terms included six primary keywords and their variations: (i) ‘dance therap*’ or ‘dance movement therap*’, AND (ii) ‘stress*’, AND (iii) ‘depress*’, AND (iv) ‘study’ or ‘studies’, AND (v) ‘treat* resist*, AND (vi) ‘adult*’. See supplementary document I for the full search strategy. Supplementary hand searches (through citation tracking and reference checks) were also carried out. A complete list of search key terms and criteria filters can be seen in supplementary document I.

Eligibility

A summary of the eligibility criteria established for this review has been displayed below.

Selection process

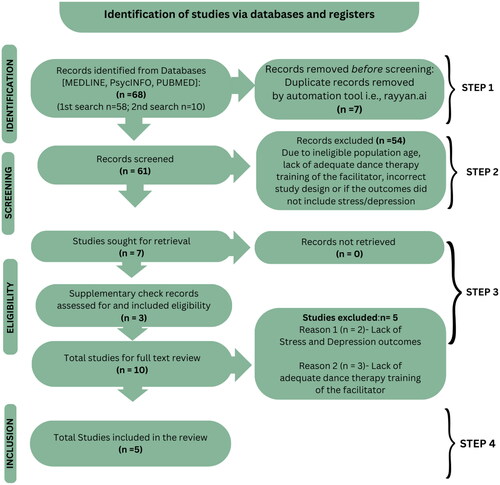

A total of 61 records were identified across three search time points after removing duplicates. Titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two authors using Rayyan.ai (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016), and disagreements were resolved via discussion. In total, 54 studies were excluded (see Table B & C in supplementary document I), and ten studies proceeded to full-text review (independently by two authors) ().

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

Full-text & quality review

Five studies were excluded at this stage. Quality assessment of the remaining included studies (five) was conducted (by two reviewers) using the Downs and Black (Citation1998) checklist (supplementary Table A). Varied measurements of stress were noted in the included studies: perceived stress, biochemical stress, and global stress.

We made one exception to our criteria and included the study by Ho et al. (2020) despite some sessions being led by a dance therapy trainee. Since the study reported appropriate direct supervision with a university-trained dance therapist and obtained a high-quality rating score (10 out of 11), this study was included.

Data extraction

We developed a form to extract the following data: author and year, population, sample size, recruitment, description of the intervention, dance therapy theory or approach, design, comparator, and outcomes (primary and secondary).

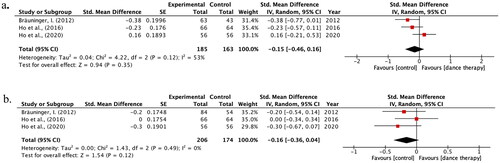

Meta-analysis

We conducted a meta-analysis of data from the three studies that used a randomised control trial design using RevMan (Review Manager v 5.4.1). Two studies were excluded from the meta-analysis due to being a secondary analysis of an included data set (Ho et al., Citation2016) and for not following an RCT design (Pylvänäinen et al. Citation2015). We used mean change scores and pooled SD to calculate group effect sizes (d = (M1−M2)/pooled SD). We then calculated standardised mean differences (SMD) with a random effects model to combine results from varied measures. No subgroup analyses/meta-regression was done.

Results

(below) is a graphic presentation of the results obtained from this systematic review as per the PICO format (McInnes et al., Citation2018). A tabular version of , including the quality assessment scores, can be seen in supplementary Table A.

Figure 2. Graphic overview of results [a tabular representation of results is in the supplementary document].

![Figure 2. Graphic overview of results [a tabular representation of results is in the supplementary document].](/cms/asset/a28a2cb9-105d-4711-9a7f-13de3ae04e3f/tbmd_a_2377389_f0002_c.jpg)

The descriptive statistics of all studies have been presented in below.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for the outcome variables pre- and post-intervention for all groups in the included studies.

The total sample comprised 613 adult participants presenting with symptoms of depression and stress (303 in the dance therapy group and 310 in the control or comparator group). Clinical populations included women receiving breast cancer treatment (n = 139), adults living with dementia/neurodegenerative disorder (n = 166), adults with depression (n = 25), and adults living with self-perceived stress (n = 162). Three studies were carried out in public hospitals in Hong Kong (Ho et al., Citation2016, 2020); one was implemented across 12 private practice centres in Germany (Bräuninger, Citation2012), and another was carried out in an outpatient clinic in Finland (Pylvänäinen et al., Citation2015). The mean age across the sample was 52 years (15.24), with 91.2% of whom were female. No further information about nuances of gender or ethnicity was reported.

All but one study used a randomised controlled trial design. Pylvänäinen et al. (Citation2015), invited participants (n = 44) to self-select between the intervention (n = 21) or treatment as usual (n = 12) to increase participant retention. Despite this attempt, the study had ‘fairly high’ dropout rates (intervention group, 16% and treatment as usual, 33%) with no specific reasons reported. While the Bräuninger (Citation2012) study was designed to be a randomised control trial, low recruitment in three (of 12) cities affected randomisation at those specific sites. From the total sample of 162 participants, 97 were allocated to the intervention group and 65 to the waitlist control groups. This study reported no dropouts, and nine cities maintained a randomised control trial study design.

Ho et al. (Citation2016) recruited 147 participants, with a dropout rate of only 5.4% (8 participants), resulting in a total analysed sample of 139; treatment (n = 69) and waitlist control (n = 70). The reasons for dropout were logistical. Since Ho et al. (2020) was a secondary analysis of Ho et al. (Citation2016), the original sample size was the same, i.e., n = 139. Eighteen participants dropped out (12.9%), leaving 121 participants for analysis, of whom 26 participated partially (18.7%). Reasons for dropouts were not specified. Ho et al. (2020) recruited 204 participants with a 21.4% dropout rate (n = 38) due to hospitalisation, refusal to continue, death, logistical challenges, and evenly distributed dropouts between groups. Analysed participant numbers were dance therapy (n = 56), exercise (n = 56), and standard care (n = 55).

All studies measured the intervention effect by comparing standardised self-report outcome measures pre-and-post-intervention (see ). In addition, Ho et al. (2020) also collected saliva samples to calculate diurnal cortisol slopes, which helped determine dance therapy’s effect on biochemical stress levels. The total dosage of dance therapy ranged from 15 to 24 h with varied frequencies. Two studies offered a 12-week intervention (Bräuninger, Citation2012; Pylvänäinen et al., Citation2015), and three studies offered a 3-week intervention (Ho et al., Citation2016, 2020). Four of the five studies offered 90-min sessions (Bräuninger, Citation2012; Ho et al., Citation2016, 2020; Pylvänäinen et al., Citation2015), and one offered 60-min sessions (Ho et al., 2020).

Meta-analysis results

The meta-analyses of the three studies did not provide evidence for a reduction in stress (p = 0.12) or depression (p = 0.49) due to dance therapy compared to standard care in our selected studies. However, dance therapy may still have clinical/experiential benefits as the diamonds in the forest plots cross the line of null effect, as seen in .

Narrative results

We adapted our narrative synthesis from Impellizzeri and Bizzini (Citation2012) as shown in supplementary Figure B.

Although perceived stress levels did not reduce in all studies, dance therapy enabled better stress management through illness acceptance, motor learning, and increased recognition of functional skills and strengths (Ho et al., 2020). Pylvänäinen et al. (Citation2015)’s study demonstrated a medium effect on stress reduction in the study, measured through the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (d = 0.76) and the Symptom Checklist-90 (d = 0.57) (Pylvänäinen et al., Citation2015). Self-report measures considered different manifestations of stress, such as activities of daily living, somatisation, interpersonal sensitivity, and better stress management, with a parallel increase in capacity to engage in activities of daily living. Similarly, a small effect of dance therapy on reducing perceived stress was seen in the 2016 study by Ho et al. (d = 0.33). A lesser, non-significant effect was found in the secondary analysis by Ho et al. (2020), where cortisol slope regression estimates were used. In the latter study, the treatment group demonstrated steeper cortical slopes than the waitlist control group, indicating a healthier hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, typically correlated with emotional resilience (Mikolajczak et al., Citation2008). The study by Bräuninger (Citation2012) reinforced this, suggesting emotional resilience and problem-oriented coping after dance therapy sessions.

Comparator

Only one study used a comparator (exercise) and found that exercise did not alleviate any psycho-social symptoms of dementia (Ho et al., 2020). In this study, mean cortisol levels reduced across the study period, revealing an initial reduction in depression. Still, these effects dissipated by the end of the study. The exercise and dance therapy sessions were equal in frequency, duration and structure (containing four 15-minute sections for warming up, stretching, exercising with towels, and cooling down) and were led by a qualified professional. Portable heart rate monitors were used to help maintain a similar exercise exertion level across the dance therapy and waitlist-control groups.

Longevity

Two studies indicated a lasting effect of dance therapy sessions at three weeks (Bräuninger, Citation2012) and three months (Ho et al., Citation2016) post-intervention. Pylvänäinen et al. (Citation2015) found benefits to isolated aspects of depression (low mood, arousal of the autonomous nervous system, and reduced social interaction) sustained until the 3-month follow-up timepoint. Only one of the studies (Ho et al., 2020) included a 1-year follow-up post-intervention and found the positive effects of dance therapy on depression in adults with dementia to have dissipated by this time point. Hence, the answer to our second research question is ‘no’. Further evidence is needed to determine if dance therapy can enable a direct reduction in stress and depression symptoms; however, the results indicate increased management strategies.

To answer our third research question about common practices used by dance therapists with adults experiencing stress and depression, we analysed each study’s theoretical approach. Pylvänäinen et al. (Citation2015) identified five principles guiding their intervention: (i) supporting safety in the body, (ii) supporting a sense of agency, (iii) supporting mindfulness skills, (iv) being attentive to interaction, (v) fostering interaction from the therapist (Pylvänäinen et al., Citation2015, p. 5). Evidently, their intervention was rooted in Chace’s (1896–1970) and Whitehouse’s (1911–1979) relational approaches to therapy. The authors’ language indicated partnership and collaboration between the facilitator and participants. This prompts consideration of a correlation between a relational approach in dance therapy and positive outcomes in treatment (Lykou, Citation2018; Young, Citation2017). The study by Bräuninger (Citation2012) did not specify an overarching approach, instead highlighting the importance of responding to the emergent movement needs of their group, indicating the active use of attunement and Chace’s (1896–1970) method of ‘feeding off’ of the group’s movement patterns (Levy, Citation2014) Improvisation, as seen in the work of Blanche Evans (1982–1974) and Trudy Schoop (1904–1999) was also used.

Three studies conducted in Hong Kong (Ho et al., Citation2016, 2020) reported adapting dance therapy to the values of Chinese culture (‘modesty’ and ‘respect’), however, did not elaborate on how this adaptation was actualised. In addition, authors described sessions as ‘specially tailored’ to alleviate stress by incorporating a predictable session outline and structured movements, like stretching, relaxation exercises, movement games, improvisational dance, and free movement of body extremities. The authors emphasised adapting dance therapy based on participants’ capacity, energy, and needs, including offering choices to sit or stand in sessions, reinforcing the importance of agency in treating comorbid stress and depression (Ho et al., Citation2016, 2020).

Ho et al. (Citation2016, 2020) described using props to invite and expand participants’ movement pathways. Scarves, ribbons, elastic bands, and small musical instruments were used to help create expansive and non-restrictive movement. Here, the value of props is contextualised by the participants’ diagnosis and physical capacity. In a way, the props offered to create movements that may not be possible due to illness or otherwise.

Ho et al. (Citation2016, 2020) also described creating simple group dances as part of the intervention, alluding to choreography in sessions to enhance communication and connection among participants. These group dances can be perceived as a way of storytelling through movement. Specific to this study’s cultural context, storytelling and meaning making aligned with Chinese culture’s social norms and folkways (Shepherd, Citation2007). The use of group dance in the studies by Ho et al (Citation2016, 2020) is consistent with previous research on the favourable effects of creative engagement and meaning making (Kaimal et al., Citation2020; Nilsen et al., Citation2021).

Therefore, the answer to our third research question regarding common practices reported by dance therapists working with adults experiencing stress and depression included improvisation, mirroring, shared group rhythms, structured movement, structured sessions, and storytelling through movement.

Discussion

Our meta-analysis of depression outcomes supports previous Cochrane reviews indicating inconclusive effects of dance therapy on depression (Bradt et al., Citation2015; Goldbeck et al., Citation2014; Karkou & Meekums, 2017; Meekums et al., Citation2015). Hence, the optimal dosage of dance therapy sessions required to achieve a decrease in depressive symptoms for this population is, therefore, yet to be determined. The studies in our review do not report comprehensive details about how the interventions were carried out. However, available data has been summarised and presented in and Supplementary Table A. Other factors, such as the choice of outcome measures, are also worth further exploring. Specifically, assessment tools need to be sensitive and specific enough to measure dance therapy’s potential effects adequately.

Language and semantics can influence cognition (Goddard & Wierzbicka, Citation2011), self-perception, and outcomes of self-report measures (Carroll et al., Citation2020). The use of pathologising language and negative phrasing such as ‘poor appetite’, ‘loss of sexual interest’, past failure’, and ‘unwanted thoughts’ from the Becks Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) can influence the outcome of self-report measures (Carroll et al., Citation2020). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-OM) use language that is comparatively less pathologising but not entirely strengths-based. Such language may cause reluctance to complete measures and challenge self-report accuracy (Jeong et al., Citation2018). The study by Pylvänäinen et al. (Citation2015) demonstrates the importance of using a sensitive measure as they used four and gained varied results based on the sensitivity of each measure.

Our meta-analysis results on dance therapy’s effect on stress contrast with a recent review by Tomaszewski et al. (Citation2023), in which authors ascertain that dance therapy is beneficial in reducing stress for adults with psychological trauma. The authors attribute group quality and intervention stability as essential structures for an optimal outcome. This propels further questions on ‘how’ the intervention was carried out and what moderators caused different outcomes across the studies in Tomaszewski et al. (Citation2023)’s and our review. Likewise, our review supports the emotional benefits of dance therapy sessions in better managing depression treatment. As mentioned by Hyvönen et al., (Citation2020) dance therapy can be an effective way to support ongoing or standard treatment by increasing meaning-making and motivation in treatment (Karkou et al., Citation2019).

Finally, these findings are yet to be contextualised within treatment resistant depression (TRD). Future dance therapy studies could use these insights to adapt and tailor these practice-based findings to TRD populations.

Practice implications

Individuals with TRD can experience compromised body awareness and limited movements. This may manifest as stiff, rigid, and limited movements (Dieterich-Hartwell, Citation2017). Hence, a vital practice implication is encouraging diverse and expansive movement patterns to increase psychological flexibility and stress management (Sampath, Citation2019). Here, props may be used to facilitate this due to their projective quality ‘surrogate movement expression’ as a possible movement pathway with this population. Ho et al. (Citation2016) suggest that the psychotherapeutic component of dance therapy is one reason for its beneficial effect on reduced stress. Thus, including techniques such as verbalisation and verbal metaphors (Koch, Citation2020; Levy, Citation2014) may be useful as a clear therapeutic choice with this population. Beyond movement, props may also propel sensory exposure and identification in adults. These skills could be foundational in helping individuals get familiar with different sensory experiences both outside and within their body, serving as a step towards recognising one’s sensorial cues of dysregulation. This is specifically relevant in adults with TRD, where dysregulation can be a presenting concern.

Limitations

The included studies varied in population characteristics, intervention duration, and outcome measures, introducing heterogeneity into the analysis and decreasing the generalisability of our review findings. We could not obtain and report further details about the individual dance therapy intervention in Bräuninger (Citation2012)’s study nor the specific intervention adaptations to Chinese culture in the studies by Ho et al. (Citation2016, 2020).

Research recommendations

We recommend more detailed reporting on ‘how’ dance therapy sessions are carried out to enable replication. We also recommend further exploration of in-depth neuro-biochemical changes (such as the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis). Longitudinal studies should be conducted to determine any lasting effects of dance therapy and determining the optimal ‘dose’ of dance therapy for sustained improvements when working with persons with complex conditions will be invaluable. Further, it may be valuable to investigate the cultural adaptations of dance therapy interventions and co-occurring interdisciplinary treatments as potential moderators of dance therapy treatment effects. Finally, we recommend the use of self-report measures that avoid pathologising language.

Conclusion

Efficacy reviews for TRD predominantly study pharmacological (Bavaresco et al., Citation2020) and neuro-modulatory interventions (Liu et al., Citation2023). Despite this bio-medical focus, the prevalence of TRD has increased in the last two decades (Sousa et al., Citation2022). There is thus a need for research to consider a biopsychosocial or holistic treatment focus, such as dance therapy. In this review, we examined the effects of dance therapy on the primary symptom clusters in TRD. We found beneficial effects of dance therapy on developing emotional resilience, problem-oriented coping, and stress management in adults with both, stress and depression. Specifically, storytelling, meaning making, and a predictable session structure were possible intervention elements that obtained these experiential outcomes. Interventional examples most frequently referenced were participant-led improvisation and exploring shared rhythm. Our synthesised findings on dance therapy practices can be a formative guide while working with these populations. Despite the lack of significant results from the meta-analysis of three studies, there is an emerging body of literature supporting the need for further research on dance therapy to enhance standard care practices in stress and depression treatment (Hyvönen et al., Citation2020; Karkou et al., Citation2019); these must be considered while treating resistant depression, where both conditions are comorbid.

Supplementary Table A and Figure B.docx

Download MS Word (145.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Neha Christopher

Neha Christopher: Graduate Researcher and part-time Dance/Movement Therapy tutor at the University of Melbourne. Neha is a board-certified Dance/Movement Therapist (ADTA) and a Registered Creative Arts Therapist (ANZACATA). Neha is among the founding board members of the Indian Association of Dance/Movement Therapy.

Ella Dumaresq

Ella Dumaresq: Lecturer in Dance/Movement Therapy at the University of Melbourne. Ella is a Registered Dance/Movement Therapist and researcher specializing in arts-based and qualitative research in community settings.

Jeanette Tamplin

Jeanette Tamplin is Associate Professor in Music Therapy at The University of Melbourne. A/Prof Tamplin is a Registered Music Therapist and researcher specialising in neurorehabilitation for people neurological injuries or conditions (including traumatic brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, Parkinson's, and dementia).

References

- Bavaresco, D.V., Uggioni, M.L.R., Ferraz, S.D., Marques, R.M.M., Simon, C.S., Dagostin, V.S., Grande, A.J., & da Rosa, M.I. (2020). Efficacy of infliximab in treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior, 188, 172838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2019.172838

- Blechert, J., Michael, T., Grossman, P., Lajtman, M., & Wilhelm, F.H. (2007). Autonomic and respiratory characteristics of posttraumatic stress disorder and panic disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(9), 935–943. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815a8f6b

- Bradt, J., Shim, M., & Goodill, S.W. (2015). Dance/movement therapy for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007103.pub3

- Bräuninger, I. (2012). Dance movement therapy group intervention in stress treatment: A randomized controlled trial (RCT). The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(5), 443–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.07.002

- Bräuninger, I. (2014). Specific dance movement therapy interventions—which are successful? An intervention and correlation study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.08.002

- Broderick, J., & Vancampfort, D. (2019). Yoga as part of a package of care versus non‐standard care for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2019(8). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012807.pub2

- Carroll, H.A., Hook, K., Perez, O.F.R., Denckla, C., Vince, C.C., Ghebrehiwet, S., Ando, K., Touma, M., Borba, C.P.C., Fricchione, G.L., & Henderson, D.C. (2020). Establishing reliability and validity for mental health screening instruments in resource-constrained settings: Systematic review of the PHQ-9 and key recommendations. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113236

- De Mutiis, C., Pasini, A., La Scola, C., Pugliese, F., & Montini, G. (2015). Nephrotic-range albuminuria as the presenting symptom of Dent-2 disease. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 41(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-015-0152-4

- Dieterich-Hartwell, R. (2017). Dance/movement therapy in the treatment of post traumatic stress: A reference model. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.02.010

- Downs, S. H., & Black, N. (1998). The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomized and non-randomized studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health, 52, 377–384.

- Goddard, C., & Wierzbicka, A. (2011). Semantics and cognition. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science, 2(2), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.101

- Gold, P.W., Machado-Vieira, R., & Pavlatou, M.G. (2015). Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression: relation to the neurobiology of stress. Neural Plasticity, 2015, 581976–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/581976

- Gold, S.M., Köhler-Forsberg, O., Moss-Morris, R., Mehnert, A., Miranda, J.J., Bullinger, M., Steptoe, A., Whooley, M.A., & Otte, C. (2020). Comorbid depression in medical diseases. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 6(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-0200-2

- Goldbeck, L., Fidika, A., Herle, M., & Quittner, A.L. (2014). Psychological interventions for individuals with cystic fibrosis and their families. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014(6), CD003148. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003148.pub3

- Grasser, L.R., & Javanbakht, A. (2021). Virtual arts and movement therapies for youth in the era of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(11), 1334–1336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.017

- Gros, D.F., Price, M., Magruder, K.M., & Frueh, B.C. (2012). Symptom overlap in posttraumatic stress disorder and major depression. Psychiatry Research, 196(2–3), 267–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.022

- Ho, R.T., Fong, T.C., Cheung, I.K., Yip, P.S., & Luk, M.Y. (2016). Effects of a short-term dance movement therapy program on symptoms and stress in patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy: A randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(5), 824–831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.12.332

- Ho, R.T.H., Fong, T.C.T., Chan, W.C., Kwan, J.S.K., Chiu, P.K.C., Yau, J.C.Y., & Lam, L.C.W. (2018). Psychophysiological effects of dance movement therapy and physical exercise on older adults with mild dementia: A randomized controlled trial. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 75(3), 560–570. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby145

- Hyvönen, K., Pylvänäinen, P., Muotka, J., & Lappalainen, R. (2020). The effects of dance movement therapy in the treatment of depression: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial in Finland. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01687

- Impellizzeri, F.M., & Bizzini, M. (2012). Systematic review and meta‐analysis: A primer. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 7(5), 493–503.

- Jeong, H., Yim, H.W., Lee, S.-Y., Lee, H.K., Potenza, M.N., Kwon, J.-H., Koo, H.J., Kweon, Y.-S., Bhang, S-y., & Choi, J.-S. (2018). Discordance between self-report and clinical diagnosis of Internet gaming disorder in adolescents. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 10084. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28478-8

- Kaimal, G., Carroll-Haskins, K., Mensinger, J.L., Dieterich-Hartwell, R., Biondo, J., & Levin, W.P. (2020). Outcomes of therapeutic artmaking in patients undergoing radiation oncology treatment: a mixed-methods pilot study. Integrative Cancer Therapies, 19, 1534735420912835. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534735420912835

- Karkou, V., Aithal, S., Richards, M., Hiley, E., & Meekums, B. (2023). Dance movement therapy for dementia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 8(8), Cd011022. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011022.pub3

- Karkou, V., Aithal, S., Zubala, A., & Meekums, B. (2019). Effectiveness of dance movement therapy in the treatment of adults with depression: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 936. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00936

- Koch, S. (2020). Indications and contraindications in dance movement therapy: Learning from practitioners’ experience. GMS Journal of Arts Therapies, 2, 1–13.

- Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Georganta, K. (2019). The relationship between burnout, depression, and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 284. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284

- Levy, F.J. (2014). Dance and other expressive art therapies: When words are not enough. Routledge.

- Liu, C., Li, L., Zhu, K., Liu, Z., Xing, W., Li, B., Jin, W., Lin, S., Tan, W., & Pan, W. (2023). Efficacy and safety of theta burst versus repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Research Square. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-2627598/v1

- Lykou, S. (2018). Relational dance movement psychotherapy: A new old idea. In H. L. Payne (Ed.), Essentials of dance movement psychotherapy (pp. 21–36). Routledge.

- McInnes, M.D.F., Moher, D., Thombs, B.D., McGrath, T.A., Bossuyt, P.M., Clifford, T., Cohen, J.F., Deeks, J.J., Gatsonis, C., Hooft, L., Hunt, H.A., Hyde, C.J., Korevaar, D.A., Leeflang, M.M.G., Macaskill, P., Reitsma, J.B., Rodin, R., Rutjes, A.W.S., Salameh, J.-P., … Willis, B.H, . (2018). Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies: The PRISMA-DTA statement. JAMA, 319(4), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.19163

- Meekums, B., Karkou, V., & Nelson, E.A. (2015). Dance movement therapy for depression. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(2), CD009895. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009895.pub2

- Mikolajczak, M., Roy, E., Luminet, O., & de Timary, P. (2008). Resilience and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity under acute stress in young men. Stress (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 11(6), 477–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890701850262

- Nilsen, M., Stalsberg, R., Sand, K., Haugan, G., & Reidunsdatter, R.J. (2021). Meaning making for psychological adjustment and quality of life in older long-term breast cancer survivors. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 734198. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.734198

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

- Pylvänäinen, P.M., Muotka, J.S., & Lappalainen, R. (2015). A dance movement therapy group for depressed adult patients in a psychiatric outpatient clinic: Effects of the treatment. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 980–980. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00980

- Ramaci, T., Bellini, D., Presti, G., & Santisi, G. (2019). Psychological flexibility and mindfulness as predictors of individual outcomes in hospital health workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1302. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01302

- Rosen, V., Ortiz, N.F., & Nemeroff, C.B. (2020). Double trouble: treatment considerations for patients with comorbid PTSD and depression. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7(3), 258–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-020-00213-z

- Sampath, D. (2019). Props in dance/movement therapy movement therapy: A journey of personal and professional exploration (Masters thesis). Pratt Institute.

- Seoane, K.J. (2016). Parenting the self with self-applied touch: A dance/movement therapy approach to self-regulation. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 38(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-016-9207-3

- Serlin, I.A. (2020). Dance/movement therapy: A whole person approach to working with trauma and building resilience. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 42(2), 176–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-020-09335-6

- Shepherd, E.T. (2007). A pedagogy of culture based on Chinese storytelling traditions [A Doctorate Thesis]. The Ohio State University.

- Sousa, R.D., Gouveia, M., Nunes da Silva, C., Rodrigues, A.M., Cardoso, G., Antunes, A.F., Canhao, H., & de Almeida, J.M.C. (2022). Treatment-resistant depression and major depression with suicide risk—The cost of illness and burden of disease. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 898491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.898491

- Tomaszewski, C., Belot, R.-A., Essadek, A., Onumba-Bessonnet, H., & Clesse, C. (2023). Impact of dance therapy on adults with psychological trauma: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2225152. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2023.2225152

- Wu, C.-C., Xiong, H.-Y., Zheng, J.-J., & Wang, X.-Q. (2022). Dance movement therapy for neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 14, 975711. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2022.975711

- Wu, V.X., Chi, Y., Lee, J.K., Goh, H. S., Chen, D.Y.M., Haugan, G., Chao, F.F.T., & Klainin-Yobas, P. (2021). The effect of dance interventions on cognition, neuroplasticity, physical function, depression, and quality of life for older adults with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 122, 104025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104025

- Young, J. (2017). The therapeutic movement relationship in dance/movement therapy: A phenomenological study. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 39(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-017-9241-9