ABSTRACT

Group-based interventions are widely used to promote health-related behaviour change. While processes operating in groups have been extensively described, it remains unclear how behaviour change is generated in group-based health-related behaviour-change interventions. Understanding how such interventions facilitate change is important to guide intervention design and process evaluations. We employed a mixed-methods approach to identify, map and define change processes operating in group-based behaviour-change interventions. We reviewed multidisciplinary literature on group dynamics, taxonomies of change technique categories, and measures of group processes. Using weight-loss groups as an exemplar, we also reviewed qualitative studies of participants’ experiences and coded transcripts of 38 group sessions from three weight-loss interventions. Finally, we consulted group participants, facilitators and researchers about our developing synthesis of findings. The resulting ‘Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions’ (MAGI) framework comprises six overarching categories: (1) group intervention design features, (2) facilitation techniques, (3) group dynamic and development processes, (4) inter-personal change processes, (5) selective intra-personal change processes operating in groups, and (6) contextual influences. The framework provides theoretical explanations of how change occurs in group-based behaviour-change interventions and can be applied to optimise their design and delivery, and to guide evaluation, facilitator training and further research.

Introduction

Understanding mechanisms by which interventions facilitate (or impede) psychological and behaviour change are crucial to developing effective interventions. More than 80 behaviour change theories (Davis, Campbell, Hildon, Hobbs, & Michie, Citation2015; Michie, West, Campbell, Brown, & Gainforth, Citation2014) and over 100 categories of change techniques (Abraham, Citation2016; Abraham & Michie, Citation2008; Michie et al., Citation2013) have been identified, some for specific intervention types including those targeting diet and physical activity (Michie, Churchill, & West, Citation2011), weight loss (Hartmann-Boyce, Aveyard, Koshiaris, & Jebb, Citation2016), smoking cessation (West, Walia, Hyder, Shahab, & Michie, Citation2010), and gambling problems (Rodda et al., Citation2018). Moreover, evidence on which types of techniques are associated with improved intervention effectiveness is accumulating (e.g., Dombrowski et al., Citation2012; Hartmann-Boyce, Johns, Jebb, & Aveyard, Citation2014; Michie, Abraham, Whittington, McAteer, & Gupta, Citation2009; Tang, Abraham, & Greaves, Citation2016). However, to date most research into change processes and change techniques has focused on individual-level, intra-personal change.

Group-based interventions are widely used to promote health and to support health-related behaviour change. Systematic reviews show that such interventions can be effective, for example, in increasing physical activity (Hanson & Jones, Citation2015; Harden et al., Citation2015), supporting weight loss (Borek, Abraham, Greaves, & Tarrant, Citation2018) and smoking cessation (Stead, Carroll, & Lancaster, Citation2017; West et al., Citation2010), and improving self-management of type 2 diabetes (Odgers-Jewell et al., Citation2017), cancer (Smith-Turchyn, Morgan, & Richardson, Citation2016) and other chronic conditions (Foster, Taylor, Eldridge, Ramsay, & Griffiths, Citation2007). For example, a meta-analysis of 24 group-based weight-loss interventions showed a mean difference in weight loss between control and intervention groups of −3.44 kg (95% CI [−4.23, −2.85]; p < .001) at 12 months (Borek et al., Citation2018).

The use of groups to deliver behaviour-change interventions is further routinely justified on the basis of time- and resource-efficiency, the opportunity for interaction between members and provision of social support (Borek & Abraham, Citation2018; Greaves & Campbell, Citation2007). It is also assumed that group members’ interactions with each other and with facilitators can generate personal change that persists beyond the life of the group. This assumption is supported by decades of research suggesting that group membership can change members’ perceptions, cognitions and behaviours (e.g., Brown, Citation1993; Cartwright & Zander, Citation1968; Smith, Citation1980). For example, the importance of group identification (or ‘group spirit’) and social support was proposed as far back as 1905 in psychotherapy groups for tuberculosis patients (Horne & Rosenthal, Citation1997). Considerable subsequent work has focused on the role of social identification in groups and how social group membership (and group interventions specifically) may influence health outcomes (e.g., Haslam, Cruwys, Haslam, Dingle, & Chang, Citation2016; Jetten, Haslam, & Haslam, Citation2012 ; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Interpersonal change processes in health-related groups have also been described, including social comparisons and social validation (Abraham & Gardner, Citation2009), and group support and communicating group member identities (West et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, individual-level change processes that have been widely researched may be targeted in group-based interventions, for example, normative belief change, attitude change, goal setting, goal review and feedback that bolsters self-efficacy. It is unclear, however, how such individual-level change processes and techniques operate in groups and how individual change is influenced by the group context.

There is wide variation in the design and delivery of health-related group-based behaviour-change interventions (GB-BCIs), and a wide heterogeneity in their effectiveness. For example, in a meta-analysis of weight-loss groups at 12 months, some studies showed average weight loss differences (between intervention and control groups) of 0-1 kg while others showed differences of up to 9.6 kg (Borek et al., Citation2018). This pattern of effective and ineffective outcomes, following group-based interventions designed to promote the same types of behaviour change, indicates a lack of understanding of, and consensus concerning, how group-based interventions work and, consequently, how they should be designed and delivered to maximise effectiveness. Available research does not provide integrated models of change processes or a basis for guidance on GB-BCI design and implementation. An integrative framework of key group features and interpersonal change processes operating in such groups, as well as types of change techniques that can facilitate behaviour change among group members, would therefore have considerable potential to improve the design and implementation of health-related GB-BCIs.

Research questions

We aimed to develop an integrative framework of group features and interpersonal change processes operating in GB-BCIs by synthesising current knowledge about groups in the fields of group dynamics and behaviour change research. Our research question was: what elements related to the design, delivery, context and change processes in groups may help explain how changes in individual behaviour and health outcomes are generated by GB-BCIs? We defined a group-based intervention as an intervention partly or fully delivered in groups, that is, when at least three people are present, interact with each other and recognise their roles as group members (or group intervention participants), and at least one other person adopts the role of facilitator and is acknowledged to hold that role. We focused on face-to-face adult groups that target health-related behaviour changes, using the example of diet and physical activity behaviour-change interventions to promote weight loss and prevention of weight-related conditions (e.g., type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease).

Methods

We used a mixed-method approach focusing on theoretical integration of data gathered in three steps from: (1) literature reviews, (2) qualitative content analysis of audio-recorded GB-BCI sessions and intervention manuals, and (3) expert consultations. We started with identifying and defining (based on relevant literature) key terms, such as a group and mechanisms of action, and these were refined as the study progressed (). We followed methodological guidance from Carroll et al. drawing on the ‘best fit’ approach to framework synthesis (Carroll, Booth, Leaviss, & Rick, Citation2013). We began with an ‘a priori framework’ in the form of a parsimonious model of group operation from a previous conceptual overview (Borek & Abraham, Citation2018). Novel, potentially relevant categories (i.e., group characteristics, change processes, technique categories or targets) were identified in the literature reviews and qualitative coding. The study team members, drawing on their experience of GB-BCI design, delivery and evaluation, and their knowledge of social psychological research on groups, discussed all candidate categories and agreed on whether to add them to the framework or incorporate them within existing ones. Through this process we also identified higher-level, overarching categories, and defined all categories and hypothesised relationships between them. Throughout the study, we also consulted with different experts outside of the study team (including group facilitators, participants and researchers) who also made suggestions for candidate categories, helped us to describe processes and techniques already included in draft versions of the framework and provided examples of these. This was an iterative process and the framework was revised after each step, and in response to feedback from experts. Categories identified in each of these steps are listed in Supplementary Document 1. Different versions of the evolving framework, following each step of the development and expert consultations, as well as further details of the methods outlined below, are provided in the technical report (Borek et al., CitationIn Press).

Table 1. Definitions of key terms used in the study.

Literature reviews

We identified and reviewed the literature on change processes in groups, including (i) theoretical literature on group dynamics and personal change in groups, (ii) existing taxonomies of categories of change techniques, (iii) measures of group processes, and (iv) qualitative studies of participants’ experiences of weight-loss groups.

Theoretical literature on group processes

We built on earlier reviews, including a previous conceptual overview of change processes in GB-BCIs (Borek & Abraham, Citation2018), guidelines on reporting of GB-BCIs (Borek, Abraham, Smith, Greaves, & Tarrant, Citation2015) and an earlier framework for design and delivery of group interventions (Hoddinott, Allan, Avenell, & Britten, Citation2010). We began with five overarching categories derived from Borek and Abraham’s (Citation2018) review. These constituted our a priori framework. They were: (1) group development processes, (2) dynamic group processes and properties, (3) social change processes, (4) personal change processes, and (5) group design and operating parameters. In parallel, we tried to encompass in the framework three categories defined in the UK Medical Research Council guidance on conducting process evaluation to understand the functioning of complex interventions (Moore et al., Citation2014): implementation (i.e., delivery methods and techniques used), mechanisms of impact (i.e., group dynamics and processes of change), and context (i.e., facilitator and participant characteristics and wider contextual influences).

We then reviewed reviews of group processes and individual change in groups (e.g., Association for Specialists in Group Work, Citation2000; Brown, Citation1993; Horne & Rosenthal, Citation1997; Jaques & Salmon, Citation2007; Johnson & Johnson, Citation1991; Knowles & Knowles, Citation1972; McGrath, Arrow, & Berdahl, Citation2000; Smith, Citation1980; Yalom & Leszcz, Citation2005) and identified change techniques and facilitation strategies (related to implementation), change processes (or mechanisms of action), and elements of group design and contextual factors, and compared these with the categories in the a priori framework.

Taxonomies categorising change techniques

We selected and reviewed six widely-used taxonomies of categories of change techniques. We will, hereafter, use the term ‘change technique’ as shorthand for a defined category of potentially-effective actions or practices assumed to influence a specified change mechanism which may or may not be effective in prompting psychological and/or behaviour change (Abraham, Citation2016). They were: (i) a theoretically-linked list of 23 frequently-used change techniques (Abraham & Michie, Citation2008), (ii) the CALO-RE taxonomy for diet and physical activity interventions (Michie et al., Citation2011), (iii) the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1) (Abraham et al., Citation2015; Michie et al., Citation2013), (iv) the Intervention Mapping taxonomy (Kok et al., Citation2015), (v) the Oxford Food and Activity Behaviors (OxFAB) taxonomy of techniques used by participants for weight loss (Hartmann-Boyce et al., Citation2016), and (vi) a taxonomy of group-specific techniques used in smoking cessation programmes (West et al., Citation2010). From these, we identified change techniques that are group-specific (i.e., unique to groups or particularly suitable to group delivery due to being dependent on inter-personal interaction) and group-sensitive (i.e., which operate at an intra-personal level but may be adapted to, or affected by, group delivery). Initially, the first author identified potentially relevant change techniques. Then, the first and second authors reviewed each taxonomy together and discussed all techniques, comparing them with, and where relevant adding novel concepts to, the mechanisms identified in the developing framework.

Measures of group processes

Through electronic searches and personal communication with other researchers working on groups, we identified three reviews of measures of intra-group processes (Cahill et al., Citation2008; Delucia-Waack, Citation1997; Orfanos, Citation2015), and other reviews of potentially relevant measures (Bales, Citation1950; Beck & Lewis, Citation2000; Chapman, Baker, Porter, Thayer, & Burlingame, Citation2010; Estabrooks & Carron, Citation2000; Kiesler, Citation2004; Lee, Koopman, Hollenbeck, Wang, & Lanaj, Citation2015; Roter & Larson, Citation2002; Tate, Rivera, Conwill, Miller, & Puig, Citation2013; Wilson et al., Citation2008; Wölfer, Faber, & Hewstone, Citation2015).

From these reviews four types of measures were identified: (i) screening tools to assess participants’ suitability for, or fit with, the group; (ii) measures to assess group facilitators’ skills and behaviours; (iii) tools to analyse and assess group interaction; and (iv) questionnaires designed for group participants to assess perceptions of group characteristics, climate and processes. We listed measures (Supplementary Document 3) and added novel mechanisms and concepts identified therein to the developing framework.

Qualitative studies of participants’ experiences of groups

We reviewed qualitative studies of participants’ perceptions and experiences of group-based interventions, focusing on interventions supporting weight loss in overweight or obese adults. We searched electronic databases (Medline, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, Embase, Social Policy and Practice accessed via Ovid platform) between 2000 and June 2016 using a detailed search strategy (Supplementary Document 2) and screened over 4000 identified references. Twenty-seven studies were included and uploaded to NVivo where they were thematically coded to identify categories that were compared with and, where relevant, added to the developing framework. (For details see Supplementary Document 2). Common themes included factors related to individuals (e.g., previous experiences of weight loss), group design (e.g., contact time, venue), facilitators (e.g., personal and professional qualities), group context (e.g., group climate), change processes (e.g., accountability to the group, peer pressure), aspects of practical delivery, and content of group sessions (e.g., group activities and topics).

Qualitative content analysis of recorded group sessions and intervention manuals

We analysed group session recordings from three GB-BCIs targeting changes in diet and physical activity to support weight loss and its maintenance: (i) the ‘Living Well Taking Control’ (LWTC) programme (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN702216700; Kok et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citationunder review), (ii) the ‘Skills for weight loss Maintenance’ (SkiM) intervention (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN45134679), and (iii) the ‘Waste the Waist’ (WtW) intervention (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN10707899; Gillison et al., Citation2012, Citation2015; Greaves et al., Citation2015). The three interventions were selected as a starting point for this work because (a) they all targeted the same behaviour change objectives; (b) they were all systematically designed employing recent psychological and behavioural science evidence and, therefore, provided examples of contemporary applications of behaviour change theory and techniques to alter specified behavioural targets; and (c) pragmatically, because the authors had access to the data from these interventions. Ethics approvals were in place for these three studies, including participant consent for audio-recording and analysis of the group sessions. All three interventions were based on available intervention delivery manuals, and were delivered in small groups (up to 15 participants) in community venues by trained facilitators with backgrounds in health promotion, diet or physical activity. Each involved a range of recognised change techniques delivered using a mixture of interactive group discussions, activities, provision of information about healthy diet, physical activity and weight loss, and self-monitoring diaries. For details about the interventions see Supplementary Document 4.

Session recordings were sampled using a purposeful strategy to maximise the diversity of transcripts (see below; for details of which sessions were sampled in each stage of analysis, see Supplementary Document 5). The recordings were transcribed verbatim, including audible non-verbal behaviours, such as laughter. The transcripts were checked for accuracy with recordings and uploaded to NVivo (v10/11) where they were organised to support analysis.

In the first stage, we purposively sampled 10 audio recordings of group sessions from the three interventions to ensure diversity across intervention stages (beginning, middle and final sessions) and facilitators. The sample included four sessions from the LWTC programme (with two different facilitators), two sessions from SkiM (with one facilitator) and four sessions from WtW (with five different co-facilitators). The first author then coded the transcripts, taking as much of an inductive approach as possible (i.e., working up from the data). The coding involved applying codes (or labels) to parts of transcripts that represented different types of group interaction, or, in other words, to capture what happened in the group, including examples of group activities, group processes and facilitation techniques.

In the second stage, we selected (sampling to ensure diversity of groups, session numbers and facilitators) an additional 28 transcripts from LWTC (n = 12) and SkiM (n = 16). Remaining recordings of WtW sessions were of insufficient quality and could not be included. In this stage we deductively coded the transcripts using a draft MAGI framework. To enable more reliable coding and double-coding, based on the evolving definitions of concepts included in the framework, we drafted coding instructions for all framework categories. The first author coded all the transcripts, and six transcripts were independently double-coded by four co-authors and one external researcher using the draft coding instructions. After the double-coding, the instructions and draft framework were revised to capture any new categories identified, improve the definitions and make the coding instructions more precise. The final coding instructions are available in Supplementary Document 6 and more details of these qualitative analyses are provided in the technical study report (Borek et al., CitationIn Press).

In addition to analysing transcripts of recordings of group sessions, we selected the primary intervention manual used to deliver group sessions from each of the three interventions and uploaded them to NVivo (v10/11). We coded the content of the manuals, identifying sections of text related to group delivery, such as instructions for group facilitation (e.g., facilitation style, group activities), and change techniques (e.g., goal setting). The codes were then compared to our developing framework.

To supplement the qualitative analyses of session transcripts and delivery manuals, the first author observed eight LWTC sessions from three different groups and the third author observed three SkiM sessions (all delivered around Exeter, UK). Field notes were kept and referred to but not formally analysed. These observations shaped our interpretation of how participants interacted with each other and the facilitator and highlighted potentially-important GB-BCI characteristics and processes that cannot be identified in audio recordings of group sessions (e.g., room set-up, non-verbal behaviour).

Expert consultations

Throughout the research, we sought expert input and feedback on the evolving framework from other researchers working with GB-BCIs, group facilitators and group participants. In the early stages, we consulted with two group participants from the LWTC programme and with two group facilitators from the LWTC and SkiM interventions. In the final stage of the research, we consulted with four LWTC participants and four group facilitators (LWTC and SkiM). Throughout the research, we sought feedback from researchers and practitioners at relevant conferences, a departmental seminar and by running a workshop at a national conference. We also sought feedback from 12 researchers and practitioners external to the research team with backgrounds in health behaviour change and group interventions who had agreed to be contacted, of whom seven provided detailed written comments on the near-final version of the framework. We asked these experts how groups might facilitate or impede behaviour changes and health outcomes, what the important processes and facilitation strategies in groups might be, and about benefits and challenges of delivering interventions in groups. We also asked them to comment on, and suggest improvements to, the framework. Feedback informed extension, revision and refinement of the developing framework.

Results

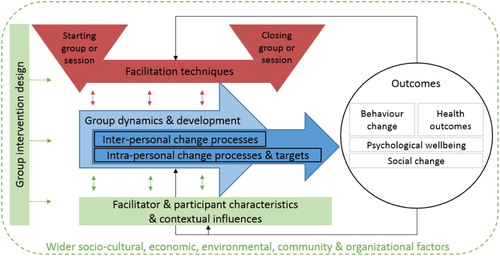

Concepts identified as important to the operation of groups were grouped into six overarching categories: (1) group intervention design, (2) facilitation techniques, (3) group dynamics and development, (4) inter-personal change processes, (5) intra-personal change processes and targets, and (6) facilitator and participant characteristics and wider contextual influences. The definitions of the key terms are reported in . The structure of the framework, and relationships between the categories, are illustrated in and specific elements in the six categories are presented in . Supplementary Document 7 includes detailed definitions and examples of the framework categories, and hypothesised processes by which they may influence each other. Each of the categories, and key elements within them are described in turn below.

Table 2. Mechanisms of action in group-based interventions (MAGI) framework.

Group intervention design

These are features of GB-BCI design that may affect the functioning of the group and the delivery and receipt of intended change processes. Group intervention design features identified included (1.1) intended processes and outcomes of the intervention (as would be specified in an intervention logic model), and the (1.2) purpose and benefits of using a group format. For example, if peer support is deemed an important basis for using a group format, facilitation techniques that promote peer support processes could be planned, rather than expecting such support to occur spontaneously.

Pre-specified (1.3) group characteristics (e.g., group size) and (1.4) participant selection and group composition, including participants’ demographic (e.g., age, gender) and condition-related (e.g., risk of diabetes) characteristics and attendance of any accompanying persons (e.g., partners), may affect interactions, and so alter operating change processes. For example, group size may affect patterns of interaction between members, whereas sharing certain characteristics may promote social identification and social comparison processes.

(1.5) Facilitator selection, especially facilitators’ professional and personal skills, and training, may affect fidelity and quality of delivery and interaction patterns in the group so determining which change processes operate. For example, facilitators whom participants consider to be credible sources, with whom they identify (e.g., peers), and who have good inter-personal skills may be more able to instigate group identification and social influence processes.

(1.6) Intervention content, including participant and facilitator materials, session content, group activities, between-session tasks and any additional resources (e.g., extra classes, access to facilities), as well as contacts outside the group (e.g., additional one-to-one counselling) were identified as part of intervention design. The (1.7) setting and venue (e.g., room size, comfort, accessibility; community versus hospital settings) are also likely to shape participants’ expectations and experiences of the program. Finally, (1.8) group set-up and delivery design elements include decisions about the contact time, and the intended facilitation style that will be used to generate planned change processes. Considering and planning these elements during intervention design is likely to optimise group dynamics and development that are conducive to the pursuit of group goals, and nurture planned change processes.

Facilitation techniques

These are used by group facilitators to deliver sessions, facilitate group dynamics, and initiate planned change processes. (2.1) Setting up the group or starting the sessions (emphasised by the triangles in ) may help establish an interpersonal context conducive to inducing inter- and intra-personal change processes. Starting sessions in on-going, open groups may differ to starting sessions in time-bound, closed groups, which has implications for the design of group activities and content. For example, in open groups personal introductions may be repeated at the beginning of every session, whereas in closed groups they may be completed at the start of the first session only.

Throughout the lifespan of the group, facilitators may have different tasks requiring different types of facilitation techniques. For example, they shape group interaction and activities, deliver intervention content and facilitate positive, while managing any negative, group processes. We identified a range of facilitation techniques to fulfil these tasks, which we categorised as: (2.2) generic techniques to facilitate group interaction and engagement; (2.3) techniques to facilitate positive group dynamics and development; (2.4) techniques to facilitate inter-personal change processes; and (2.5) techniques to prompt intra-personal change processes. These facilitation techniques might change or be adapted over time depending on emerging group dynamics and change processes, the needs and characteristics of the group and participants and their progress in achieving goals and intervention outcomes (hence two-way arrows in ).

Finally, we also identified (2.6) techniques for closing the group or session. These may help reinforce participants’ commitment to change and to return to the next session. Although some of these ‘closing’ techniques might be delivered throughout the intervention, the use of such techniques at the end of the group or session may be useful in reinforcing messages about the initiation and maintenance of change. Examples of these different types of facilitation techniques are in .

Table 3. Examples of different types of facilitation techniques.

Group dynamic and development processes

Group dynamics are emerging and changeable processes and properties used to describe how small groups work (i.e., how individuals function as a group), and group development describes how groups change over time (i.e., represented by the arrow in ). These processes are unique to a group setting and are relevant to different types of groups, regardless of whether they target personal change. Successful development of positive group dynamics and progression into a cohesive, collaborative group working towards common goals may help create a social environment that promotes change processes. Conversely, negative group dynamics or impeded development may inhibit change processes and negatively affect participants’ experiences of the group, increasing the likelihood of low attendance and drop out. Therefore, group dynamics and development may be conceptualised as underpinning change processes in groups. Group dynamics can be influenced by facilitation techniques, facilitator and participant characteristics (and the relationship and interaction between them), and by contextual influences (e.g., wider social norms). These influences on group dynamics can be planned (e.g., selection of facilitation techniques) or unplanned and specific to the group (e.g., personalities of group members).

lists the types of group dynamic processes and properties identified in this study. For a group of individuals to become a ‘group’, they may need to develop or identify (3.1) group goal(s). This might involve a common purpose or task for the group (e.g., organising a health-related event), or individual goals that group members have in common and work towards (e.g., losing weight). (3.2) Identification with or as a group, that is developing a perception that a number of people constitute a group and are group members (i.e., self-defining as a group), is another process that underlies forming a group. Group goals and identification may contribute to development of (3.3) group cohesion and attractiveness (i.e., bonds that members have with the group and each other). Stronger cohesion and perception of attractiveness of the group to its members (e.g., that it fulfils their needs and goals) can affect members wanting to belong to, and remain in, the group.

Moreover, group dynamics include: (3.4) group climate (i.e., a socio-emotional context or group atmosphere); (3.5) group engagement (how actively members participate in the group); (3.6) communication patterns (how participants communicate with each other and with the facilitators, and how co-facilitators interact); (3.7) group norms which include explicit and implicit rules about acceptable and unacceptable behaviour in the group; (3.8) group roles which refer to members’ formal and informal functions and responsibilities within the group (e.g., formal – a facilitator, a treasurer; informal – a joker, debater). Finally, (3.9) group development refers to how a group itself may change over time. Among many models and theories on how groups change, commonly groups are thought to move through the stages of forming, storming (insecurities, tensions), norming (establishing patters and relations), performing (working towards group goals) and (often) adjourning (Tuckman & Jensen, Citation1977).

These group dynamic and development properties and processes are interactive and may have reciprocal effects. For example, identifying with the group may help identify a common group goal and create a sense of group cohesion, whereas group cohesion may be measured through a sense of identification with the group and perceptions of common group goals. Such group dynamics occur in any types of groups and they emerge regardless of the facilitator’s actions. However, facilitators can actively promote positive group dynamics, for example, through identifying and agreeing on group rules for working together, and helping resolve any conflicts or tensions.

Inter-personal change processes

These are change processes that are instigated and operate in social contexts and through social (or group) interactions. They are unique to, or reinforced by, the group context. They can be influenced by group dynamics, such as establishment of a common goal, a sense of group identification and cohesion, and confidential and supportive group climate.

Many behaviour-change groups are interactive groups, in which participants (4.1) share experiences and have an opportunity to learn from each other (4.2. social learning) by exchanging information, advice and ideas (through group discussions), and by modelling or vicarious learning (e.g., through group activities). Group interaction can also be a source of (4.3) social influence whereby participants influence each other’s beliefs or behaviours, for example, by referring to personal experiences and expertise, using health-promoting or ‘resistant’ talk, exerting persuasion or providing encouragement or pressure. Participants may also influence each other directly through (4.4) agreeing or disagreeing with, or challenging, each other.

Many health-related groups offer opportunities for (4.5) social support in the group, which can involve informational (e.g., exchange of information), emotional (e.g., encouragement) or practical support (e.g., buddying up to do something together). As part of social support processes, groups may also provide opportunities for making new social connections (thus, they may help reduce isolation and develop a support network) and for providing support to others (thus, capitalising on benefits of reciprocity). Groups can also provide opportunities for (4.6) social validation of, or normalising, participants’ experiences, and helping them realise that they are not alone with a problem or challenge, which can reinforce self-efficacy and self-esteem.

Change may be facilitated through (4.7) social identification with others who are perceived as belonging to similar social groups or categories. This may involve recognition of pre-established shared identities (from outside the group) and/or development of a new group identity among members. Change might be particularly reinforced if group member identities promote health-related social norms and behaviours. Conversely, health-impeding identities may need to be explored and re-defined in the group in ways that can bolster behaviour change. Being in a group may also create opportunities for upward and downward (4.8) social comparisons (including identifying or becoming role models) and for feeling (4.9) accountable to the group for achieving individual or group goals, which might motivate participants to take action. Similarly, (4.10) competition might be a source of motivation to improve performance, either compared to others in a group (intra-group competition) or to other groups (inter-group competition). Participants may equally (4.11) cooperate by working together to achieve group or individual goals.

Change can also be instigated and reinforced by collaborative (4.12) group problem solving (i.e., involving group members discussing common ‘problems’ or challenges and identifying possible solutions), and by providing (4.13) feedback to the group on the group performance (which may reinforce common group goals and cooperation). Finally, being in a group might prompt (4.14) social facilitation, whereby people’s performance on simple or well-trained tasks may improve, whereas the performance of less established, complex skills may be undermined, by being in the presence of others.

Intra-personal change processes and targets

Intra-personal change processes and psychological targets (e.g., beliefs) operate within individuals and can be instigated without a group. When generated in a group, intra-personal change processes may be affected or prompted by inter-personal processes, or they may occur simultaneously. Both these types of change processes may be also affected by the group dynamics and development, facilitator techniques, facilitator and participant characteristics, and the wider socio-cultural context within which the group operates (as illustrated in ). Moreover, intra-personal change processes may, and should for longer-term effects, extend beyond the group (as represented by the darker arrow extending beyond the lighter ‘group dynamics’ arrow in ). Here we report selected examples of intra-personal change processes that are particularly common in, and adaptable to, group-based delivery.

Group sessions require considerable time and effort so participants need to (5.1) commit to attend the group. In the group, participants can (5.2) develop and express understanding (or lack of understanding), which can be facilitated by social learning processes. Interacting in a group, participants may (5.3) self-present themselves in an intentional way (e.g., as health-oriented) and express their health-related (5.4) normative beliefs, (5.5) attitudes, (5.6) attributions, (5.8) expectations of interventions outcomes, (5.9) motivation, or (5.10) self-efficacy and sense of personal control (or lack thereof). They may express, discuss and acknowledge changes in these targets, which, in turn, can be affected by the group and others’ expressions. Moreover, if the expressed beliefs or attitudes are different from participants’ behaviour patterns, the resultant (5.7) cognitive dissonance could prompt change in motivation and behaviour to reduce the inconsistency. Group interaction and sharing can also help develop (5.17) self-insight and a better self-understanding, and might affect (5.18) changes in self-identity (e.g., becoming a ‘new’, healthy person).

Many behaviour-change groups involve participants (5.11) setting goals, (5.12) reviewing goals or progress, (5.14) identifying individual barriers and solutions to them, and (5.16) feedback on individual performance. These techniques, intra-personal in nature, can be facilitated in groups collaboratively by engaging group participants, discussing their goals, progress or barriers, and thus facilitating inter-personal change processes, such as sharing experiences, social learning, or accountability. Groups can also provide a context for (5.13) developing and practising new skills and behaviours that can prompt modelling. They can be good platforms for discussing and sharing ideas for (5.15) self-monitoring, and may provide opportunities for (5.20) learning through association (e.g., using rewards or incentives) and encouraging (5.19) using self-talk, (5.21) changing or forming habits and (5.22) stress and emotional management. This is not an exhaustive list; many more intra-personal processes involved in behaviour change have been identified in other studies. Here we have highlighted intra-personal change processes commonly targeted in GB-BCIs and especially those that may be particularly sensitive to group delivery (i.e., those that may be enhanced or impeded by group dynamics, inter-personal change processes and facilitation techniques).

Facilitator and participant characteristics, and other contextual influences

These are factors external to the group that may influence, and be influenced by, what happens in the groups (i.e., by group dynamics and inter- and intra-personal change processes). The identified (6.1) facilitator characteristics, that may influence the group and participants, include facilitators’ personality and inter-personal skills (e.g., warmth, relatedness), cognitive and emotional factors influencing their role (e.g., knowledge, experiences, passion), professional skills and experience (e.g., in presentation, group management), or demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, related health conditions). Similarly, we identified (6.2) participant characteristics including, for example, their personality, cognitive and emotional factors, physical or mental health issues, values and beliefs, initial motivation, personal agenda or reasons to attend, readiness to change, type of locus of control, level of knowledge, or previous experiences. These facilitator and participant characteristics are ‘brought’ to the group, may influence group interaction and relationships (e.g., rapport with others in the group), and may change over time as a result of participating in, or facilitating, the groups (e.g., increased assertiveness, confidence, skills). Some of these characteristics may be controlled at the GB-BCI design stage by a selection of facilitators or members. Others might be more difficult or impractical to control but, to some extent, may be managed in the group through facilitation techniques. (6.3) Other contextual influences may also affect the group and individual change, including, for example, available support networks and social connectedness, positive or negative influences of other people, social situations (e.g., celebrations, eating out) or wider social norms. All of these factors may be present and affect participants outside the group but may be also brought into, and discussed in, the group, thus providing opportunities for inter-personal change processes (e.g., sharing experiences, group problem solving).

Outcomes and wider influencing factors

Outcomes of GB-BCIs include a range of intended and unintended outcomes, such as changes in psychological processes underpinning individual behaviour change, physical health outcomes targeted in interventions (e.g., weight loss), and changes in psychological wellbeing (e.g., self-esteem, self-efficacy, social connectedness, mental health), all of which may improve overall health-related quality of life. They may also include social change (e.g., in norms or practices) across groups of individuals. Outcomes may be affected, directly or indirectly, by inter- and intra-personal change processes and the underlying group dynamics. Feedback on outcomes, or perception of progress towards them (or its lack), can affect all other elements of GB-BCIs, i.e., group dynamics, change processes, facilitation techniques used by the facilitators, and individual characteristics and contextual factors (as represented in by the black arrows going from Outcomes). As outcomes are specific to each intervention, they are not discussed further here.

Finally, wider influencing factors, such as socio-cultural, economic, environmental, community and organisational factors, may influence all aspects of GB-BCIs, including their design, implementation, processes, facilitators and participants, and outcomes. For example, economic factors may affect participants’ behaviours (e.g., cost of healthy food) or intervention design and implementation (e.g., pre-specified requirements, available resources). We acknowledge the importance of these wider determinants of health, and recognise their impact on group functioning, but these are beyond the focus of this study.

Discussion

This research identified a range of concepts related to group design, delivery, context and change processes that together explain mechanisms of action capable of generating behaviour change in group-based behaviour-change interventions (GB-BCIs). These were integrated into a framework, comprising six overarching categories and 62 more specific sub-categories, derived from Borek and Abraham (Citation2018), reviews of relevant literatures, qualitative coding and expert consultations. By highlighting how GB-BCIs may influence individual psychological and behaviour change, the framework can be used to guide design, delivery and evaluation of GB-BCIs, and can also inform training for group facilitators.

Many of the change processes identified in the framework likely co-occur and interact dynamically. For example, the process of sharing experiences may prompt social learning and social validation. Inter-personal change processes can occur between individuals (e.g., group members engage in group problem solving) as well as within individuals (e.g., group members identify solutions to personal barriers in response to group interaction). To optimise effectiveness, these may need to be planned in advance and facilitated in situ during GB-BCIs. Intra-personal change processes also occur within, and are affected by, the inter-personal, group context. For example, goal setting might be specified and refined by sharing and discussing one’s goals with the group, or impeded by not having the time or opportunity to sufficiently focus and reflect on individual needs. Moreover, for any behaviour change to occur, inter-personal change processes will need to prompt intra-personal change, and intra-personal change processes may need to extend outside or beyond the duration of the group to lead to sustained individual behaviour change. Importantly, some of these processes may also negatively affect psychological or behaviour change; for example, identifying with stigmatised social groups (e.g., Crabtree, Haslam, Postmes, & Haslam, Citation2010) or making social comparisons with those performing much better than oneself may decrease the motivation, self-efficacy and self-esteem (Abraham & Gardner, Citation2009). Our framework provides a menu from which to select targeted processes that then need to be carefully designed-into GB-BCIs, actively facilitated, and checked for feasibility, acceptability and their correct functioning.

GB-BCIs vary greatly in their design, implementation, targeted change mechanisms and outcomes. The framework offers a set of categories all of which are more or less important in different GB-BCIs. Practical limitations can make it difficult to control all of these processes in intervention design and implementation. This may, in turn, curtail investigations of change processes during subsequent process evaluations. Nonetheless, the extent of specificity is likely to enhance GB-BCI design, delivery and evaluation. Striving for design precision is crucial to enable robust evaluation and to optimise intervention effectiveness. The MAGI framework provides a categorical system to facilitate design precision and specification of change processes in logic models. Not all concepts, processes and techniques included in the MAGI framework will be relevant to all interventions. Designers and evaluators of GB-BCIs will need to select those categories from the MAGI framework most pertinent to their intervention depending on the intended change processes, outcomes and delivery context. Use of the framework in this way would provide a structured basis for further research to empirically establish the relevance and importance of the specific concepts, processes and techniques across different interventions.

Implications

Implications for GB-BCI design: The framework highlights elements that should be considered when designing GB-BCIs. Social interaction in GB-BCIs should not be considered as a default and potentially time-saving ‘delivery method’ but a critical ‘active ingredient’ of behaviour-change interventions. Therefore, intervention designers need to consider how group dynamics and inter-personal change processes can generate change and be designed-into, and facilitated during GB-BCIs. For example, an intervention might target social identification processes by facilitating the emergence of a shared social identity in the group (e.g., by ensuring homogeneous group composition and small group size) and facilitation methods (e.g., by encouraging member interactions, different types of participation and allowing breaks) (Tarrant et al., Citation2016). Alternatively, the design may specify changing health-related normative beliefs through changing group norms, facilitated by specific group activities, such as group discussions about relevant social norms and normative beliefs and role plays in which participants critique norms and beliefs that may lead to unhealthy behaviours or thought patterns (e.g., Cruwys, Haslam, Fox, & McMahon, Citation2015) – or both social identification and normative belief changes may be targeted. Moreover, it is important to design and adapt GB-BCIs to take account of the specific characteristics and needs of targeted participants and wider contextual influences. This may include making relevant (e.g., cultural) adaptations, or ensuring that the selection of participants provides a degree of homogeneity in relation to health needs, socio-economic challenges and cultural commonalities. This can render group activities more relevant to participants, facilitate better group identification and cohesion, facilitate social validation between members and minimise the risk of widening health inequalities. The (highly effective) Football Fans in Training intervention is a good example of selecting participants with things in common (being male, overweight football fans) to enhance intra-group cohesion (Gray et al., Citation2013; Hunt et al., Citation2014). By providing an overview of key change processes operating in groups, the MAGI framework extends existing guidance on designing health behaviour-change interventions and we envisage that it will be used in conjunction with such guidance (e.g., Bartholomew, Parcel, Kok, Gottlieb, & Fernandez, Citation2016; Craig et al., Citation2008; Hoddinott et al., Citation2010; Wight, Wimbush, Jepson, & Doi, Citation2016).

Implications for GB-BCI delivery: The framework highlights the role of facilitators, their characteristics and skills in using facilitation techniques, and how these might affect the operation and maintenance of change processes critical to intervention outcomes. Consequently, facilitator training and competencies are critical to optimising GB-BCI effectiveness (e.g., Avery, Whitehead, & Halliday, Citation2016; Dixon & Johnston, Citation2010; Michie et al., Citation2011; Reddy, Vaughan, & Dunbar, Citation2010). This can be informed by examination of facilitators’ experiences of delivering GB-BCIs (e.g., Barlow, Citation2005; Catalano, Kendall, Vandenberg, & Hunter, Citation2009; Hipwell, Turner, & Barlow, Citation2008). Facilitators of GB-BCIs have three main tasks: to facilitate group dynamics, to ensure delivery of intervention content, and to promote targeted change processes. Identifying and using effective techniques to facilitate group dynamics, including managing counter-productive interaction, is critical, as is expertise in the targeted behaviours and selected change techniques. The MAGI framework can be used as a resource for group facilitators, improving their understanding of the group processes that are sensitive or unique to group delivery and in designing facilitator training. It is also relevant, for example, to shared consultation groups in general practice for patients with long-term illnesses (Egger, Stevens, Ganora, & Morgan, Citation2018).

Implications for GB-BCI evaluation: The framework can also be a guide to process evaluations of GB-BCIs. It could help structure group session observations, analyses of session recordings, guide participant and facilitator interviews or design of questionnaires evaluating participant and/or facilitator perceptions and experiences of GB-BCIs. Investigating the role and impact of specific design elements and group processes, either pre-designed or unintended, can explain how outcomes were affected. For example, investigating characteristics of the venue and setting (e.g., organisational culture and its impact on facilitators and participants) (e.g., Hoddinott, Britten, & Pill, Citation2010), group dynamics (e.g., group conflicts) (e.g., Nackers et al., Citation2015) or communication patterns (e.g., facilitator–participant talk ratios) (e.g., Stenov, Henriksen, Folker, Skinner, & Willaing, Citation2016) can explain variations in intervention outcomes. The MAGI study report (Borek et al., CitationIn Press) provides examples of how the framework can be used to identify facilitation techniques and change processes from transcripts of group sessions, and suggestions for mixed-methods approaches to exploring links between group processes and outcomes.

Implications for research: Our study suggests also numerous directions for future research on GB-BCIs. Firstly, the framework could improve specification of the GB-BCI content and intended change processes, both in design and reporting. This could facilitate further research and development of evidence on which of the GB-BCI design features and change processes included in the framework may improve intervention outcomes. Secondly, systematic reviews that (1) appraise evidence underpinning each framework concept to justify its inclusion in our framework or estimate its importance, and (2) that synthesise qualitative studies on people’s experiences of other types of groups, could usefully extend and refine our framework. Further research needs to verify generalisability of the framework, and refine it to be applicable, to other types of groups, contexts and populations (e.g., groups for addictions, management of chronic illness, in education settings, involving participants in different cultural/ethnic backgrounds, children, and delivered one-to-one or virtually/online). Thirdly, it would be useful to formally map available quantitative measures of group dynamics and processes to framework concepts to aid selection for use in future research and identify areas for further development. Our qualitative methods for coding and analysing group sessions, more sophisticated quantitative group-level analyses and further mixed-methods and other approaches (e.g., systems-based, realist) could then be developed and applied to facilitate more detailed examination of mechanisms in GB-BCIs. Linking findings on mechanisms to data on engagement and outcomes in particular would help build an evidence base on what group features, facilitation techniques and group processes are important, when and for whom in GB-BCIs, and how group dynamics and processes are influenced by the participant and wider contextual characteristics. Such evidence would help validate, refute or extend aspects of our framework and be used to improve delivery or inform design. Finally, developing and evaluating facilitator training toolkits to help facilitators competently employ specific techniques for participant engagement, group dynamics and change processes, and identifying new facilitation and change techniques would further help to optimise the delivery of GB-BCIs.

Strengths and limitations

The MAGI framework is, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive theoretical synthesis of change processes operating in GB-BCIs. It bridges a gap between the extensive literature on group dynamics in social psychology and the growing literature on individual change processes and techniques in health psychology. We drew upon multiple different methods and sources to identify relevant concepts and processes, including literature, qualitative data, and consultations with group participants, facilitators, researchers and practitioners. By combining and triangulating results from the different steps of the study, we have created a more comprehensive and integrated review than previous studies (e.g., Davis et al., Citation2015; Grant, Treweek, Dreischulte, Foy, & Guthrie, Citation2013; Pound & Campbell, Citation2015). We kept records of decisions involved in the framework development and its refinements and where the included concepts and processes were identified, ensuring that the framework development process was as transparent as possible (see Borek et al., CitationIn Press).

Due to the extensiveness of the relevant research literature published over decades and across disciplines, it was not feasible to systematically search and review all potentially relevant literature on each of the change processes and concepts included in the framework. We focused primarily on weight-loss interventions, and on face-to-face groups for adults. Consequently, we might have missed some characteristics, processes and techniques relevant to GB-BCIs, and generalisability of the framework to other types of GB-BCIs is yet unclear, especially in groups targeting different behaviours, in other types of groups (e.g., online) or in other populations (e.g., children or families).

Our secondary qualitative analyses included data from three interventions that some co-authors (but not the primary researcher conducting the qualitative analyses) were involved in designing and/or evaluating. This may have increased familiarity with the data and created expectations regarding targeted change processes and techniques. We also consulted with 35 experts outside the project team, including 27 researchers and practitioners, four group facilitators and four group participants, and incorporated their diverse range of suggestions and advice into the final iterations of the framework. Of course, the framework is not an exhaustive list of all processes and techniques. Instead, it provides the most up-to-date and comprehensive synthesis available that can be further developed, revised and validated by other researchers.

We also note the limitations inherent in mapping the framework categories to the steps in which they were identified (as reported in the Supplementary Material 1). Different studies might define and operationalise concepts or processes differently, despite using similar terminology. There is also a variable quantity and quality of evidence supporting the processes and hypotheses included in our framework, some of which still need to be empirically tested. The categories included in the framework are, therefore, specified and operationalised to differing extents and there is variation in the theoretical detail and empirical evidence underpinning them, which should be taken into account when using the framework to design GB-BCIs. While the framework aims to provide a ‘menu’ of options, it does not provide recommendations on which change processes should be targeted or which facilitation techniques should be used and how they should be delivered in practice. All such categorisation systems evolve as empirical evidence accumulates, and the MAGI framework is likely to evolve as further research is conducted and evidence accumulates on change processes in a wider range of group interventions.

Conclusion

The mechanisms of action in group-based interventions (MAGI) framework is a synthesis of group characteristics, change processes and categories of change techniques that can explain individual behaviour change arising from group-based interventions. The framework summarises group design features, dynamics, development processes, inter- and intra-personal change processes in groups, and how they interact with each other. It identifies facilitation techniques used to instigate and facilitate behaviour change in groups, and acknowledges facilitator and participant characteristics as well as contextual influences that affect the processes and outcomes in group-based interventions. It is a comprehensive resource for designers, facilitators and evaluators of GB-BCIs. It can be used to select characteristics and processes important to a particular intervention and so guide intervention design and facilitator selection and training.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.2 MB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (927.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.1 MB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all facilitators and participants in the three group-based interventions from which we used data (Waste the Waist, Skills in weight loss Maintenance, Living Well Taking Control). We thank A/Prof Matthew Jones and Dr Leon Poltawski for their helpful insights and advice, Mrs Jaine Keable from Westbank for access to their Living Well Taking Control programme, and the members of the advisory groups, including group facilitators (Miss Amy Clarke, Miss Sian Derrick, Mrs Ruby Entwistle and Mrs Anna Murch), representatives from the public and patients involvement group (Mrs Sue Sedgman, Mr Douglas Osman, Mrs Jackie Morant and Mr Andrew Wilkie) and researchers (Dr Amanda Avery, Dr Yael Bar-Zeev, Dr Enzo Di Battista, Dr Tegan Cruwys, Dr Liz Glidewell, Dr Cindy Gray, Dr Marta Moreira Marques, and Dr James Nobles) for feedback on the framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Aleksandra J. Borek http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6029-5291

Charles Abraham http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0901-1975

Colin J. Greaves http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4425-2691

Fiona Gillison http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6461-7638

Sarah Morgan-Trimmer http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5226-9595

Rose McCabe http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2041-7383

Jane R. Smith http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5658-9334

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abraham, C. (2016). Charting variability to ensure conceptual and design precision: A comment on Ogden (2016). Health Psychology Review, 10, 260–264. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2016.1190293

- Abraham, C., & Gardner, B. (2009). What psychological and behaviour changes are initiated by ‘Expert Patient’ training and what techniques are most helpful? Psychology & Health, 24(10), 1153–1165. doi: 10.1080/08870440802521110

- Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27(3), 379–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379

- Abraham, C., Wood, C. E., Johnston, M., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Richardson, M., & Michie, S. (2015). Reliability of identification of behaviour change techniques in intervention descriptions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-015-9727-y

- Association for Specialists in Group Work. (2000). Association for specialists in group work professional standards for the training of group workers. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 25(4), 327–342. doi: 10.1080/01933920008411677

- Avery, A., Whitehead, K., & Halliday, V. (2016). How to facilitate lifestyle change: Applying group education in healthcare. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: A method for the study of small groups (Vol. Xi). Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley.

- Barlow, J. H. (2005). Volunteer, lay tutors’ experiences of the chronic disease self-management course: Being valued and adding value. Health Education Research, 20(2), 128–136. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg112

- Bartholomew, L. K., Parcel, G. S., Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., & Fernandez, M. E. (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach (4th ed). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Beck, A. P., & Lewis, C. M. (2000). The process of group psychotherapy: Systems for analyzing change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Borek, A. J., & Abraham, C. (2018). How do small groups promote behaviour change? An integrative conceptual review of explanatory mechanisms. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 30–61. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12120

- Borek, A. J., Abraham, C., Greaves, C., & Tarrant, M. (2018). Group-based diet and physical activity weight-loss interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(1), 62–86. doi:10.1111/aphw.12121

- Borek, A. J., Abraham, C., Smith, J. R., Greaves, C. J., & Tarrant, M. (2015). A checklist to improve reporting of group-based behaviour-change interventions. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 963. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2300-6

- Borek, A. J., Smith, J. R., Greaves, C. J., Gillison, F., Tarrant, M., Morgan-Trimmer, S., … Abraham, C. (In Press). Developing and applying a framework to identify and understand ‘Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions’ (MAGI): A mixed-methods study. NIHR Efficacy & Mechanism Evaluation. Retrieved from www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/eme/1420203/#

- Brown, R. (1993). Group processes: Dynamics within and between groups. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Cahill, J., Barkham, M., Hardy, G., Gilbody, S., Richards, D., Bower, P., … Connell, J. (2008). A review and critical appraisal of measures of therapist-patient interactions in mental health settings. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 12(24), iii, ix–47.

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., Leaviss, J., & Rick, J. (2013). ‘Best fit’ framework synthesis: Refining the method. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37

- Cartwright, D., & Zander, A. (1968). Group dynamics: Research and theory (3rd ed). London: Tavistock.

- Catalano, T., Kendall, E., Vandenberg, A., & Hunter, B. (2009). The experiences of leaders of self-management courses in Queensland: Exploring health professional and peer leaders’ perceptions of working together. Health & Social Care in the Community, 17(2), 105–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00801.x

- Chapman, C. L., Baker, E. L., Porter, G., Thayer, S. D., & Burlingame, G. M. (2010). Rating group therapist interventions: The validation of the group psychotherapy intervention rating scale. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 14(1), 15.

- Crabtree, J. W., Haslam, S. A., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2010). Mental health support groups, stigma, and self-esteem: Positive and negative implications of group identification. Journal of Social Issues, 66(3), 553–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01662.x

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655–a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Fox, N. E., & McMahon, H. (2015). ‘That’s not what we do’: evidence that normative change is a mechanism of action in group interventions. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 65, 11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.003

- Davis, R., Campbell, R., Hildon, Z., Hobbs, L., & Michie, S. (2015). Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review, 9(3), 323–344. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722

- Delucia-Waack, J. L. (1997). Measuring the effectiveness of group work: A review and analysis of process and outcome measures. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22(4), 277–293. doi: 10.1080/01933929708415531

- Dixon, D., & Johnston, M. (2010). Health behaviour change Competency framework: Competencies to deliver interventions to change lifestyle behaviours that affect health. NHS Health Scotland. Retrieved from http://www.healthscotland.com/documents/4877.aspx.

- Dombrowski, S. U., Sniehotta, F. F., Avenell, A., Johnston, M., MacLennan, G., & Araújo-Soares, V. (2012). Identifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity-related co-morbidities or additional risk factors for co-morbidities: A systematic review. Health Psychology Review, 6(1), 7–32. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2010.513298

- Egger, G., Stevens, J., Ganora, C., & Morgan, B. (2018). Programmed shared medical appointments: A novel procedure for chronic disease management. Australian Journal of General Practice, 47(1/2), 71.

- Estabrooks, P. A., & Carron, A. V. (2000). The physical activity group environment Questionnaire: An instrument for the assessment of cohesion in exercise classes. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(3), 230–243. doi: 10.1037//1089-2699.4.3.230

- Foster, G., Taylor, S. J., Eldridge, S., Ramsay, J., & Griffiths, C. J. (2007). Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD005108. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005108.pub2

- Gillison, F., Greaves, C., Stathi, A., Ramsay, R., Bennett, P., Taylor, G., … Chandler, R. (2012). ‘Waste the waist’: The development of an intervention to promote changes in diet and physical activity for people with high cardiovascular risk. British Journal of Health Psychology, 17(2), 327–345. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02040.x

- Gillison, F., Stathi, A., Reddy, P., Perry, R., Taylor, G., Bennett, P., … Greaves, C. (2015). Processes of behavior change and weight loss in a theory-based weight loss intervention program: A test of the process model for lifestyle behaviour change. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0160-6

- Grant, A., Treweek, S., Dreischulte, T., Foy, R., & Guthrie, B. (2013). Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: A proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials, 14, 15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-15

- Gray, C. M., Hunt, K., Mutrie, N., Anderson, A. S., Leishman, J., Dalgarno, L., & Wyke, S. (2013). Football fans in training: The development and optimization of an intervention delivered through professional sports clubs to help men lose weight, become more active and adopt healthier eating habits. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-232

- Greaves, C. J., & Campbell, J. L. (2007). Supporting self-care in general practice. The British Journal of General Practice, 57(543), 814–821.

- Greaves, C., Gillison, F., Stathi, A., Bennett, P., Reddy, P., Dunbar, J., … Taylor, G. (2015). Waste the waist: A pilot randomised controlled trial of a primary care based intervention to support lifestyle change in people with high cardiovascular risk. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), 1. doi: 10.1186/s12966-014-0159-z

- Hanson, S., & Jones, A. (2015). Is there evidence that walking groups have health benefits? A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(11), 710–715.

- Harden, S. M., McEwan, D., Sylvester, B. D., Kaulius, M., Ruissen, G., Burke, S. M., … Beauchamp, M. R. (2015). Understanding for whom, under what conditions, and how group-based physical activity interventions are successful: A realist review. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 958. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2270-8

- Hartmann-Boyce, J., Aveyard, P., Koshiaris, C., & Jebb, S. A. (2016). Development of tools to study personal weight control strategies: OxFAB taxonomy. Obesity, 24(2), 314–320. doi: 10.1002/oby.21341

- Hartmann-Boyce, J., Johns, D. J., Jebb, S. A., Aveyard, P., & Behavioural Weight Management Review Group. (2014). Effect of behavioural techniques and delivery mode on effectiveness of weight management: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Obesity Reviews, 15(7), 598–609. doi: 10.1111/obr.12165

- Haslam, C., Cruwys, T., Haslam, S. A., Dingle, G., & Chang, M. X.-L. (2016). Groups 4 health: Evidence that a social-identity intervention that builds and strengthens social group membership improves mental health. Journal of Affective Disorders, 194, 188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.010

- Hipwell, A., Turner, A., & Barlow, J. (2008). ‘We’re not fully aware of their cultural needs’: tutors’ experiences of delivering the expert patients programme to South Asian attendees. Diversity in Health and Social Care, 5(4), 281–290.

- Hoddinott, P., Allan, K., Avenell, A., & Britten, J. (2010). Group interventions to improve health outcomes: A framework for their design and delivery. BMC Public Health, 10(1), 800. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-800

- Hoddinott, P., Britten, J., & Pill, R. (2010). Why do interventions work in some places and not others: A breastfeeding support group trial. Social Science & Medicine, 70(5), 769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.067

- Horne, A. M., & Rosenthal, R. (1997). Research in group work: How did we get where we are? The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22(4), 228–240. doi: 10.1080/01933929708415527

- Hunt, K., Wyke, S., Gray, C. M., Anderson, A. S., Brady, A., Bunn, C., … Miller, E. (2014). A gender-sensitised weight loss and healthy living programme for overweight and obese men delivered by Scottish Premier League football clubs (FFIT): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383(9924), 1211–1221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62420-4

- Jaques, D., & Salmon, G. (2007). Learning in groups: A handbook for face-to-face and online environments (4th ed). London: Routledge.

- Jetten, J., Haslam, C., & Haslam, S. H. (eds.). (2012). The social cure: Identity, health and well-being. Hove: Psychology Press.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. P. (1991). Joining together: Group theory and group skills (4th ed). London: Prentice-Hall.

- Kiesler, D. J. (2004). Manual for the checklist of interpersonal transactions-revised (CLOIT-R) and checklist of psychotherapy transactions-revised (CLOPT-R): A 2004 update. Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University. http://www.vcu.edu/sitar/CLOITManualUpdate2004.pdf

- Knowles, M. S., & Knowles, H. (1972). Introduction to group dynamics. New York, NY: Association Press.

- Kok, G., Gottlieb, N. H., Peters, G.-J. Y., Mullen, P. D., Parcel, G. S., Ruiter, R. A. C., … Bartholomew, L. K. (2015). A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: An intervention mapping approach. Health Psychology Review, 10(3), 297–312. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155

- Kok, M., Solomon-Moore, E., Greaves, C., Smith, J. R., Kimberlee, R., & Jones, M. (2016). Evaluation of living well, Taking control: A community-based diabetes prevention and management programme. Bristol: University of the West of England. Retrieved from http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/30234/.

- Lee, S. M., Koopman, J., Hollenbeck, J. R., Wang, L. C., & Lanaj, K. (2015). The Team Descriptive Index (TDI): A multidimensional scaling approach for team description. Academy of Management Discoveries, 1(1), 91–116. doi: 10.5465/amd.2013.0001

- McGrath, J., Arrow, H., & Berdahl, J. (2000). The study of groups: Past, present, and future. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 95–105. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_8

- Michie, S., Abraham, C., Whittington, C., McAteer, J., & Gupta, S. (2009). Effective techniques in healthy eating and physical activity interventions: A meta-regression. Health Psychology, 28(6), 690–701. doi: 10.1037/a0016136

- Michie, S., Ashford, S., Sniehotta, F. F., Dombrowski, S. U., Bishop, A., & French, D. P. (2011). A refined taxonomy of behaviour change techniques to help people change their physical activity and healthy eating behaviours: The CALO-RE taxonomy. Psychology & Health, 26(11), 1479–1498. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2010.540664

- Michie, S., Churchill, S., & West, R. (2011). Identifying evidence-based competences required to deliver behavioural support for smoking cessation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 41(1), 59–70. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9235-z

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., … Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Michie, S., West, R., Campbell, R., Brown, J., & Gainforth, H. (2014). ABC of behaviour change theories: An essential resource for researchers, Policy makers and practitioners. Silverback.

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., … Baird, J. (2014). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. London: MRC Population Health Science Research Network. Retrieved from http://www.populationhealthsciences.org/MRC-PHSRN-Process-evaluation-guidance-final-2-.pdf

- Nackers, L. M., Dubyak, P. J., Lu, X., Anton, S. D., Dutton, G. R., & Perri, M. G. (2015). Group dynamics are associated with weight loss in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Obesity, 23(8), 1563–1569. doi: 10.1002/oby.21148

- Odgers-Jewell, K., Ball, L. E., Kelly, J. T., Isenring, E. A., Reidlinger, D. P., & Thomas, R. (2017). Effectiveness of group-based self-management education for individuals with Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analyses and meta-regression. Diabetic Medicine, 34(8), 1027–1039. doi: 10.1111/dme.13340

- Orfanos, S. (2015). Measures of group processes: A review of questionnaire-based, interactional-analysis and qualitative approaches. In: Group therapies for schizophrenia: identifying and linking group interactions and group experiences with outcomes. PhD Thesis. Unit for Social Community Psychiatry, Queen Mary University of London; London.

- Pound, P., & Campbell, R. (2015). Exploring the feasibility of theory synthesis: A worked example in the field of health related risk-taking. Social Science & Medicine, 124, 57–65.

- Reddy, P., Vaughan, C., & Dunbar, J. (2010). Training facilitators of group-based diabetes prevention programs : Recommendations from a public health intervention in Australia. In P. Schwarz, P. Reddy, C. Greaves, J. Dunbar, & J. Schwarz (Eds.), Diabetes prevention in practice (pp. 57–67). Retrieved from http://dro.deakin.edu.au/view/DU:30029458

- Rodda, S., Merkouris, S. S., Abraham, C., Hodgins, D. C., Cowlishaw, S., & Dowling, N. A. (2018). Therapist-delivered and self-help interventions for gambling problems: A review of contents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(2), 211–226. doi: 10.1556/2006.7.2018.44

- Roter, D., & Larson, S. (2002). The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Education and Counseling, 46(4), 243–251.

- Smith, P. B. (1980). Group processes and personal change. London: Harper and Row.

- Smith, J. R., Greaves, C. J., Thompson, J., Taylor, R., Jones, M., Armstrong, R., Moorlock, S., Griffin, A., Kok, M., Solomon-Moore, E., Price, L., & Abraham, C. (under review). The community-based prevention of diabetes (ComPoD) study: A randomised, waiting list controlled trial of a voluntary sector-led diabetes prevention programme.

- Smith-Turchyn, J., Morgan, A., & Richardson, J. (2016). The effectiveness of group-based self-management programmes to improve physical and psychological outcomes in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Oncology, 28(5), 292–305. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2015.10.003

- Stead, L. F., Carroll, A. J., & Lancaster, T. (2017). Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub3