ABSTRACT

Several theoretical models have described the ways that patients and partners respond to a health problem. Most of these models are faced with limitations regarding the role of cognitive/emotional appraisals and coping behaviors, and the potential interactions between individual and dyadic variables. Therefore, new theoretical approaches are needed to capture the multiple processes that take place within dyadic adaptation to illness. Here, the major aspects of the dyadic adaptation/dyadic coping models are reviewed and their limitations are outlined. Moreover, a new theoretical approach to the dyadic-regulation processes that are important for adaptation to illness is proposed. The Dyadic-Regulation Connectivity Model emphasizes the concept of system connectivity and the role of central network hubs in dyadic regulation. Network hubs represent the common ‘space’ between intra- and inter-personal processes, and are closely connected to each other. The model posits that dyadic regulation processes evolve over time, all network hubs are fully responsive to changes in any part of the mechanism, while the entire mechanism is nested within the self- and the dyadic-system, the illness, and the broader socio-cultural contexts. The theoretical and research implications of the proposed model are also discussed.

Adaptation to illness is a complex process which very often involves patients’ partners. There is long line of research regarding the impact of illness on partners, as well as their significant role in promoting patients’ well-being. Also, several theoretical models try to describe the ways that patients and partners react when dealing with a health problem. However, most of these dyadic regulation/coping models are faced with certain limitations. Thus, new theoretical approaches are needed so as to better capture the multiple processes that take place in dyadic adaptation to illness. Ιn this paper the major dyadic regulation/coping models are briefly presented, their limitations are outlined and a new perspective on dyadic adaptation to illness, which emphasizes the constant interaction between individual and dyadic factors, is proposed.

Adaptation to illness as a dyadic regulation process

For chronic patients and their partners, adaptation to illness is a dyadic phenomenon. A severe illness exposes not only patients, but also their partners to increased risk of physical and mental health problems (e.g., August et al., Citation2011; Baanders & Heijmans, Citation2007; Franks et al., Citation2010; Hickman & Douglas, Citation2010; Leonard & Cano, Citation2006) or even death (Christakis & Allison, Citation2006). This is probably a result of the stressors that accompany illness (Bowen et al., Citation2011) and the demands it imposes on the couple (Applebaum & Breitbart, Citation2013; Given et al., Citation2001). Of course, partners’ health and illness-related behavior may in turn affect patients’ well-being (Chung et al., Citation2009; Elliott & Shewchuk, Citation2005).

Partners are often involved in the management of illness and its negative consequences. For example, partners may help patients adhere to medical advice, deal with the illness symptoms or the negative side-effects of treatment, and make treatment decisions (e.g., Bertoni et al., Citation2015; Dekel et al., Citation2014; Otto et al., Citation2015). Partners also provide emotional and practical support to patients, and collaborate with them in the development of coping plans and actions (e.g., regarding necessary lifestyle changes; Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007). This in turn may affect the well-being of the couple and the quality of their relationship (e.g., Badr & Carmack Taylor, Citation2008; Badr et al., Citation2010; Ben-Zur et al., Citation2001; Berg et al., Citation2008; Fagundes et al., Citation2012; Schokker et al., Citation2010; Staff et al., Citation2017; Traa et al., Citation2015).

Patients and partners typically engage in discussions and exchange information about illness (Whitford et al., Citation2009). This results in the development of shared ways of understanding and representing illness-related stressors that in turn guide patient and partner behavior and affect their well-being (Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007; Bodenmann, Citation2005; Weinman et al., Citation2003). In fact, there is strong evidence that patient and partner representations of illness (i.e., their perceptions, beliefs, and expectations about an illness/symptom; Leventhal et al., Citation1980) are related not only to own, but also to each other’s well-being and quality of life (e.g., Benyamini et al., Citation2009; Dempster et al., Citation2011; Lingler et al., Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, unresponsiveness of partners in talking about illness has been associated with poor mental health, poor relationship functioning, and the use of less adaptive coping strategies in patients (Lepore & Helgeson, Citation1998; Manne, Citation1999).

It is possible that patients and partners use each other’s illness-related representations as a source of information in order to validate or amend their own beliefs or behavior (Karademas et al., Citation2019), which in combination with the close relationship between patient and partner affective state (e.g., Segrin et al., Citation2012) provides further evidence of the robust bond between patient and partner self-regulation mechanisms. Overall, it seems that patients and partners form a dyadic-regulation system which affects both persons’ adaptation to illness and their health.

Models of dyadic regulation

The importance of viewing adaptation to illness as a dyadic (i.e., patient and partner) regulation process has been recognized since the 1990s. A common characteristic of the first models, many of which refer not only to illness but also to other critical events, is their emphasis on a dyadic conceptualization of the stressful condition. That is, the interpersonal context in which both members of the couple respond to own but also each other’s experience. A full presentation of the theories regarding dyadic adaptation to illness or other critical situations is beyond the scope of this paper. One may find a relevant review in Falconier and Kuhn (Citation2019). Here, only the major points of these models will be presented, with an emphasis on the more recent ones, so as to highlight their evolution (see also for an overview of the similarities and differences between the models described here). Their limitations will also be discussed.

Table 1. Overview of the similarities and differences among the models of dyadic adaptation to chronic illness.

The early theoretical models

Although recent theories try to give answers to questions regarding the entire process of couples’ adaptation to illness (e.g., how couples make sense of illness, and how they cope with it), the early theoretical models were referring only to coping behaviors. Coyne and Smith (Citation1991), and DeLongis and O’Brien (Citation1990) were the first researchers to investigate adaptation to illness in the context of interpersonal relationships. Although they acknowledged the fact that the coping strategies employed by couples may not be the only or most crucial determinant of the outcomes (Coyne & Smith, Citation1991), they emphasized relationship-focused coping, a type of coping which refers to the management of each other partner’s needs and the regulation of their relationship. The emphasis was on what each member of the couple personally did to deal with the problems and emotions of the other member.

This emphasis has guided several studies which underline the importance of personal strategies employed to regulate partners’ reactions. For example, partner overprotectiveness has been related to negative outcomes for the patient, such as decreased sense of control, more distress, worse physical well-being, lower adherence to medical advice, and worse relationship satisfaction (e.g., Hagedoorn et al., Citation2000; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Kuijer et al., Citation2000; Vilchinsky et al., Citation2011). Similarly, protective buffering (i.e., the efforts to deny or hide concerns or difficulties) has been related to worse physical and psychological outcomes for both providers and receivers, as well as for their relationship (e.g., Dagan et al., Citation2011; Lyons et al., Citation2016; Schokker et al., Citation2010; Vilchinsky et al., Citation2011). On the contrary, actively engaging the patient in conversations about the situation and personal feelings has been associated with better outcomes (e.g., less distress, better relationship functioning; Hagedoorn, Dagan, et al., Citation2011; Kuijer et al., Citation2000). It should be noted, however, that the majority of relevant studies have focused far more on the relationship of coping to relationship/marital satisfaction and psychological well-being than to physical health or health-related quality of life. Also, relationship-focused coping seems to be more strongly associated with relationship or marital satisfaction and psychological well-being (r2 = .15 – .30 in most studies; e.g., Hagedoorn, Puterman, et al., Citation2011; Hinnen et al., Citation2008; Johnson et al., Citation2015; Kramer, Citation1993; Kuijer et al., Citation2000; Lyons et al., Citation2016), than with physical well-being (r2 < .15 or .10 in almost all studies; e.g., Bertoni et al., Citation2015; Joekes et al., Citation2007; Johnson et al., Citation2015).

In another early theoretical model, Revenson (Citation1994) emphasized the importance of coping congruence (see also ). Coping congruence refers to either the similarity or the complementarity of patient and partner coping styles as a predictor of personal and relationship-related outcomes. Revenson described couple’s adaptation to illness as a spiraling process in which the patient distress affects partner coping, which in turn affects patient distress and coping efforts. Through a feedback loop, the latter further affects partner reactions, and so on. Although this was a step towards a better understanding of the dynamic interplay between patient and partner behavior, the model still described couple’s adaptation to illness as a ‘dance’ of its members’ personal reactions only.

Several studies have examined the impact of coping (in)congruence, but their findings are inconsistent. There is evidence that patients and partners report better health outcomes and marital satisfaction when they hold similar or complementary coping styles (e.g., Barnoy et al., Citation2006; Norton & Manne, Citation2007). Still, there are studies which have shown that similarity in the use of certain coping strategies is related to worse functioning and well-being (e.g., in the use of emotion-focused coping, Ben-Zur et al., Citation2001; or when both partners report low use of common dyadic coping, Meier et al., Citation2019). In addition, in most studies, less than 8–10% of the illness-related outcomes (e.g., distress, psychosocial adjustment to illness, physical impairment) variance seems to be accounted for by coping (in)congruence (e.g., Ben-Zur et al., Citation2001; Fagundes et al., Citation2012; Norton & Manne, Citation2007), although coping (in)congruence seems to be more strongly related to marital quality (r2 > .10; e.g., Norton & Manne, Citation2007). Probably, the potential impact of coping (in)congruence is dependent on individual, dyadic, and illness-related factors (Falconier & Kuhn, Citation2019), while it is only one of the several ways that patient and partner coping mechanisms interact and impact adaptation to illness.

Communal coping

Building on the previous models, Lyons et al. (Citation1998) were the first to emphasize the role of cognitive appraisal as an integral part of coping and adaptation of couples, families or communities to a stressful event. They also emphasized the role of communication between partners regarding the stressor (see also ). These researchers argued that a form of cooperative problem-solving strategy, called communal coping, is salient when dealing with personal or interpersonal stressors. Communal coping refers to ‘the pooling of resources and efforts of several individuals … to confront adversity’ (Lyons et al., Citation1998, p. 580). It includes the representation of a stressor as a common one (i.e., ‘our’ problem), the communication about the stressor among the interested parties, and the estimation that cooperative action can address it.

Recently, Helgeson et al. (Citation2018) advanced this model by proposing specific pathways that link communal illness appraisals with communal coping, as well as communal coping with patient and partner psychological and physical outcomes. According to these authors, although communal appraisal and coping may be beneficial for both partners, their primary goal is patient’s health. A shared appraisal about the health problem and the communication between patients and partners facilitate collaboration and may lead to more effective interactions (i.e., the patient is more willing to ask for support and the partner readier to provide it). These interactions in turn are interpreted by the couple as a collaborative effort to deal with the situation. Communal coping is related to health outcomes through four interdependent mediators: an enhanced sense of control, the perception of illness as less stressful, enhanced relationship quality, and enhanced self-regulation.

So far, not many studies have examined communal coping and its impact, at least as far as chronic illness is concerned. Existing research has shown that indeed a representation of illness as a shared problem facilitates the use of more communal coping, which in turn is positively related to patients’ physical and psychological health (e.g., Helgeson et al., Citation2018, Citation2019; Zajdel & Helgeson, Citation2020). As with previous models, shared appraisals and supportive coping seem to be more closely related to relationship quality than patients’ physical well-being (e.g., Berg et al., Citation2008; Helgeson et al., Citation2019). In any case, the communal coping approach took a big step towards the better understanding of couples’ adaptation to illness as the interpersonal ‘dialogue’ of appraisals and coping efforts, rather than as only a person’s chain reactions to their partners’ behavior. Yet, this model did not include other possible forms of dyadic coping and focused only on the stressors that are appraised by the couple as common ones.

The Systemic Transactional Model

The Systemic Transactional Model (STM; Bodenmann, Citation1997, Citation2000, Citation2005), emphasizes the interdependence and mutuality between the two partners’ stress and coping processes. The STM builds on the models of communal and relationship-focused coping by also referring to coping strategies that are directed to self and by including several forms of dyadic coping (see ). According to the STM, both partners tend to express their distress verbally or non-verbally and ask for help and support, even if the stressor concerns only one member of the couple. Thus, the stress reactions and coping efforts of one member of the couple essentially affects both partners, and results into the origination of a dyadic adaptation process. Bodenmann (Citation1997) suggested that besides the typical primary and secondary appraisals of the stress process, as defined by Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984), each partner also evaluates the appraisals of the other partner (by examining potential discrepancies or similarities), as well as whether own appraisals have been acknowledged by the other partner. The two partners may also evaluate together the situation and make joint primary and secondary appraisals.

These appraisals guide the coping behaviors of both members of the couple, which may be individual (i.e., directed to self and own problems), dyadic (i.e., directed to the other partner or to the couple), or common. Dyadic coping may be emotion-focused (e.g., efforts to regulate partner’s emotions), problem-focused (e.g., helping partner find possible solutions), or ‘delegated’ (i.e., taking over some of the partner’s responsibilities so as to help them out with the situation). In addition, three forms of negative dyadic coping have been delineated by the STM: hostile, ambivalent, and superficial coping. Common dyadic coping refers to the complementary involvement of both partners or to joint actions, which aim in dealing with the stressor. Dyadic and common coping have two functions: reduce the stress and promote both partners’ well-being, and also protect and enhance their relationship.

Although the model refers to any (major) stressor, there is a growing number of studies which have examined several aspects of the STM in the context of chronic illness. For example, the use of open and constructive communication has been associated with less distress and more relationship satisfaction in patients and their partners (e.g., Badr & Carmack Taylor, Citation2008; Manne et al., Citation2006). But there is also some evidence that disclosure of feelings and thoughts might not always be beneficial – for example, when patients were disclosing much less than their partners (Hagedoorn, Puterman, et al., Citation2011). Regarding dyadic coping, positive dyadic and common coping have been related to better patient and partner physical and psychological outcomes, and better relationship functioning, whereas negative dyadic coping has been associated with worse outcomes (e.g., Badr et al., Citation2010; Dagan et al., Citation2011; Feldman & Broussard, Citation2006; Rottmann et al., Citation2015; Vaske et al., Citation2015; Zimmermann et al., Citation2010). Also, overall evidence suggests that delegated dyadic coping may be the least beneficial in comparison to the other forms of positive dyadic coping (Falconier & Kuhn, Citation2019).

As with previous models, most of these studies focus more on relationship functioning and psychological well-being as the outcome of dyadic coping than on physical well-being. Overall, the different forms of dyadic coping seem to be related to relationship functioning and psychological well-being in a moderate way across studies (r2 = .10 – .20), but more closely than to physical well-being (e.g., Badr & Carmack Taylor, Citation2008; Badr et al., Citation2010; Rottmann et al., Citation2015; Zimmermann et al., Citation2010). The strength of these relationships weakens after controlling for illness-related and sociodemographic variables (e.g., Badr et al., Citation2010; Dagan et al., Citation2011; Feldman & Broussard, Citation2006).

With regard to the potential interactions between individual and dyadic or common forms of coping, to our knowledge no studies have particularly examined the issue. The STM suggests that dyadic and common coping becomes significant only when individual coping is unsuccessful in reducing distress or solving the problem (Bodenmann et al., Citation2016). Also, Bodenmann (Citation2005) argued that individual and dyadic/common coping efforts are applied in sequence. At the beginning, a person engages in individual efforts to cope with a stressor. If the stressor is prolonged or severe, then the person seeks and engage in dyadic/common coping, while also using individual coping strategies (Bodenmann, Citation2005). This, however, seems to be a rather narrow perspective of the dynamic interchange between individual and dyadic/common forms of coping and thus a potential limitation of the model.

The Developmental-Contextual Model

In contrast to the STM, which refers to any major stressor, the Developmental-Contextual Model (DCM; Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007) was developed especially for couples coping with chronic illness. In this respect, the DCM focuses on processes that specifically refer to chronic illness. The DCM emphasizes the fact that dyadic appraisals and coping may change over the life span and across the different stages of the illness experience. Indeed, there is evidence that younger and older couples cope with illness in different ways, while illness may have a diverse impact on a couple’s quality of life depending on partners’ age (Acquati & Kayser, Citation2019). There is also some evidence that patient and partner well-being and adaptation to illness covary as illness evolves over time (Lyons et al., Citation2014).

The model suggests that dyadic appraisals about illness is the starting point for dyadic coping, but may also be affected by the forms of dyadic coping employed by the couple. The model uses the Common Sense Model (Leventhal et al., Citation1980, Citation1992) to describe dyadic cognitive illness representations (i.e., illness identity, timeline, control, and consequences), while adds two more aspects: illness ownership (who owns the illness? does the illness belong to the patient or to the couple?), and specific stressor appraisals (e.g., partners may experience their own, distinct stressors within the context of illness). Appraising the health problem as a shared one may lead to collaborative coping efforts, while a similar patient and partner appraisal of the situation may contribute to positive forms of dyadic coping. Existing research, albeit not extensive at all, has shown that dyadic appraisals are important for patient and partner behavior and well-being (Helgeson et al., Citation2019; Lingler et al., Citation2016), as well as that it is the interplay between appraisals and coping strategies that affects couple’s adaptation to illness (e.g., Johnson et al., Citation2014).

The DCM conceptualizes dyadic coping along a continuum ranging from partner uninvolvement to overinvolvement but, in contrast to the STM, does not refer to specific forms of dyadic coping (e.g., common or supportive coping). A patient may perceive their partner’s involvement in four ways (Berg et al., Citation1998): uninvolvement; support – the partner provides emotional or instrumental support; collaboration – the partner is actively involved in joint problem solving; control – the partner dominates coping efforts and actions. In contrast to the Systemic Transactional Model, Berg and Upchurch (Citation2007) suggest that dyadic coping may be used immediately after the emergence of a stressful event, in combination with individual coping, and not after individual coping efforts have been exhausted or failed. The DCM does not address the issue of the potential interactions between individual and dyadic cognitive appraisals and coping efforts.

Finally, according to the DCM, the entire dyadic appraisal and coping process is moderated by various factors that are related to the illness (e.g., the type and stage of illness), the couple (e.g., the relationship quality), and the broader context (e.g., culture, gender).

The Cognitive-Transactional and the Integration Models

Badr and Acitelli (Citation2017) recently proposed a new model which emphasizes the cognitive processes that occur throughout dyadic adaptation to illness. Their Cognitive-Transactional model (CTM) is based on the Systemic Transactional Model and the Developmental-Contextual Model and refers especially to dyadic coping with chronic illness. According to this model, the formation of an individual appraisal of the situation (i.e., the development of personal representations about illness and illness ‘ownership’), as well as the communication between patients and partners regarding the problem are necessary before a dyadic appraisal can begin.

Specifically, the CTM posits that patient appraisal of illness as a shared problem (i.e., our problem) is the starting point for the dyadic appraisals of the situation. If the patient evaluates illness as only a personal problem, then they will engage only in individual appraisals and coping efforts. In case that individual coping efforts are effective, patients stick to these. If the individual coping efforts are ineffective, then the patient communicates the problem to their partner. A responsive partner helps the development of dyadic appraisals, which in turn guide dyadic coping (conceptualized here in almost the same way as in the Systemic Transactional Model). If dyadic coping is also not effective, then new dyadic appraisals and/or new dyadic coping strategies may take place, or the patient may retreat to individual coping. In addition, Badr and Acitelli (Citation2017) emphasized the role of self-efficacy and dyadic efficacy (i.e., the confidence in the couple’s ability to work as a team) as mediators between individual and dyadic coping, respectively, and health or relationship-related outcomes.

It is interesting that this model seems to describe individual and dyadic coping as almost mutually exclusive. There are particular processes that lead to each type of coping, while a person may use a type of coping only if the other is ineffective in achieving the desired outcomes. In other words, the CTM embraces the perspective of the Systemic Transactional Model regarding the relationship between individual and dyadic coping (see ). It is also interesting that, according to this model, coping is associated with outcomes through self- or dyadic efficacy, although there is evidence that the role of self-efficacy in adaptation to illness is complex and does not always mediate the relation of perceptions or coping to health outcomes (e.g., French, Citation2015; Knowles et al., Citation2016).

Even more recently, Falconier and Kuhn (Citation2019) proposed an Integration Model regarding dyadic coping with any type of shared/dyadic stressful condition, including illness. The model attempts to integrate previous models, such as the Systemic Transactional Model and the Developmental-Contextual Model, into a single one, although it does not include concepts central to those models, such as the specific illness related appraisals and coping behaviors directed to self. The model proposes that dyadic coping starts from partners’ communication about their distress. The dyadic coping responses may be either ‘individual’ (that is, targeting the other partner’s reactions) or ‘conjoint’. In particular, dyadic coping may be ‘individual positive’ (i.e., personal responses to help the other partner cope with stress, such as active engagement), ‘individual negative’ (e.g., hostile or controlling behavior), ‘positive conjoint’ (i.e., what partners do together to cope with the stressor), and ‘negative conjoint’ (e.g., common negative coping).

As in most of the previous models, the Integrated Model also refers to several factors that may shape dyadic coping, including developmental (e.g., changes in the stressful condition), relational (e.g., mutuality, relationship quality), and contextual ones (e.g., culture, socio-economic conditions). The model does not refer to the role of individual or dyadic appraisals of the stressful situation, or to self-directed individual coping strategies.

Overall, the existing dyadic regulation models, especially the more recent ones, have similarities (e.g., regarding the importance of communication between partners), but also differences (e.g., regarding the role of individual coping and its interaction with dyadic coping, or the types of dyadic coping; see also ). So far, there is empirical evidence for several aspects of these models, such as the role of appraisals and dyadic or common coping. On the other hand, there is lack of evidence regarding other parts of the models, like the possible interactions between individual and dyadic coping (e.g., whether they function in a serial or even exclusive manner, as suggested by the STM or the CTM, or in parallel, as posited by the DCM). Also, many of the relevant studies focus predominantly on relationship functioning as the outcome of dyadic coping. Staff et al. (Citation2017) estimated that 76% of relevant studies focus on this outcome, whereas only 28% also include health-related variables (mostly psychological well-being). Furthermore, it seems that the association of dyadic coping, as described in the existing theoretical models, with physical health outcomes is significantly weaker than its association with relationship functioning. This represents a challenge for the dyadic regulation models (i.e., understand how dyadic coping may impact physical health), at least as far as adaptation to chronic illness is concerned. Therefore, longitudinal studies with repeated measures over time, where both individual and dyadic variables (e.g., appraisals, coping behaviors, characteristics) and a variety of outcomes (e.g., physical symptoms, quality of life, relationship quality) will be included, are warranted so as to examine the complex relationships between these factors and also test the predictive validity of each model.

Still, not only a more extensive examination of the existing dyadic models is needed in order to push forward our understanding of the processes that take place within dyadic regulation. Although existing models have greatly contributed to the conceptualization and understanding of the dyadic processes and substantially prompted and guided relevant research, they also seem to be faced with certain theoretical limitations. Overcoming these limitations is essential so as to further our comprehension of the dyadic regulation mechanism. The following section discusses these limitations in relation to the weak associations between dyadic regulation variables and patient health outcomes.

Limitations of the existing dyadic regulation models

Limitations regarding illness-related appraisals

Although several dyadic models emphasize the role of cognitive appraisal in shaping coping behaviors, these may not adequate describe the ways that individual and dyadic appraisals interact. The Systemic Transactional Model (STM) argues that each partner evaluates and takes into consideration the appraisals of the other partner, examining potential incongruence (Bodenmann, Citation2000), while other models strongly stress the importance of congruence (e.g., Revenson, Citation1994). Yet, there is evidence that the degree of appraisals (dis)similarity is just one aspect of the interaction between patient and partner appraisals (e.g., partner appraisal may moderate the relation of patient appraisals to well-being; Giannousi et al., Citation2016).

Even the distinction between individual patient and individual partner (which may be similar or dissimilar), and joint appraisals may not be able to actually depict the complex ways that patient and partner appraisals interact and determine behavior. For instance, it is possible for individual patient and partner appraisals to determine each other in a mutually interactive and direct way. It is also possible for a patient or a partner to change (automatically or after consideration) their initial ‘individual’ appraisals as a reflection on what the other member of the couple says, believes (to the extent that they reveal their thoughts), or does (e.g., their emotional responses, even when they do not reveal their actual thoughts). After all, personal perceptions and behaviors often conform to the perceptions and behaviors of other persons (Bandura & Walters, Citation1963; Deutsch & Gerard, Citation1955), while according to the Common Sense Model (e.g., Leventhal et al., Citation2005), patients’ social environment significantly affects their thoughts, emotions, and behavior. In other words, patient and partner individual appraisals may constantly interact and mutually shape each other, as well as dyadic appraisals, in several ways.

Only the Developmental-Contextual Model (DCM) specifies the type of illness-related appraisals that are relevant to dyadic adaptation to illness, by adopting the suggestions of the Common Sense Model (CSM) regarding the cognitive representations of illness (Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007). The DCM refers only to representations regarding illness, although representations about each treatment option and its effects, or about each coping behavior may also be important for adaptation to illness and illness-related behavior (Leventhal et al., Citation2005). All other recent models (e.g., the STM), generally refer to primary and secondary (individual or joint) appraisals, as well appraisals regarding illness ownership. Yet, illness-related cognitive and emotional representations, as outlined by the CSM, have proven to be a valid way of describing the ways that patients and their partners understand illness (Leventhal et al., Citation1997, Citation2016; Weinman et al., Citation2003). Moreover, there is ample evidence that these illness representations are strongly related and may predict coping behaviors and health-related outcomes (e.g., Hagger et al., Citation2017; Leventhal et al., Citation2016). Therefore, they should probably be used also in the context of a chronic illness-related dyadic regulation model.

Finally, although several models put a special emphasis on the ownership of the condition, it is possible for most couples dealing with a health problem to (sooner or later) translate it into a common one (a ‘we’-approach; Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007). A diagnosis of a severe health problem, a significant deterioration in health, or the consequences of a chronic condition can cause the generation of personal illness representations also to partners (Weinman et al., Citation2003), at least to the extent that they are aware of the problem. Patients typically expect their partners to help them (Lepore & Helgeson, Citation1998; Whitford et al., Citation2009), while the effects of a chronic or severe illness are significant for partners as well (e.g., August et al., Citation2011; Bowen et al., Citation2011; Hickman & Douglas, Citation2010), thus forcing them to deal with illness and transform the problem into a common one.

Limitations regarding coping

Another limitation of most dyadic regulation/coping models refers to the anticipated associations between individual (patient or partner) and dyadic/common coping. Some models, like the Integration Model (Falconier & Kuhn, Citation2019), do not refer to ‘individual/personal’ coping at all, while for most other models (e.g., the Systemic Transactional Model – STM and the Cognitive-Transactional Model – CTM), individual and dyadic coping are either employed in a sequential (e.g., dyadic coping after individual efforts) or in a ‘restrictive’ way (e.g., patients employ dyadic processes only if individual coping is ineffective, or may retreat to individual coping, if dyadic coping fails). Only the Developmental-Contextual Model suggests that dyadic coping may be used together with individual coping. However, the relations between individual and dyadic coping, as well as their relations to outcomes and adaptation to illness are probably more complex than the existing models suggest.

First, individual coping is strongly related not only to own outcomes (e.g., Hagger et al., Citation2017), but also to partner outcomes. There is evidence that partner ‘individual’ (self-directed) behavior is related to patient health outcomes, while patient coping is associated with partner well-being (Bertoni et al., Citation2015; Fagundes et al., Citation2012; Karademas & Thomadakis, Citation2020; Keller et al., Citation2017).

Second, there is probably a very close relationship between individual and dyadic coping behaviors, while their ‘boundaries’ or even their end goals may not always be clear. Individual coping behaviors may sometimes have a parallel ‘dyadic’ purpose as well. For example, a patient may cope with the possibility of a future illness relapse by changing their lifestyle (e.g., quitting smoking). But, at the same time, they may also hope that, by their example, they will help their smoker partners quit smoking as well. Also, dyadic coping may sometimes serve a parallel ‘individualistic’ goal. For instance, a partner may actively support and assist a patient in their decision to change their diet, according to the physician’s advice, but may also acknowledge that such a change is beneficial for own health as well. It is also possible for individual coping to have an (originally) unintended impact on the behavior of other member of the couple (i.e., a dyadic effect). For example, a patient’s successful or unsuccessful efforts to regulate own negative emotions are likely to be reflected on partner emotions, as there is a strong link between patient and partner affective state (e.g., Segrin et al., Citation2012). In this regard, and as result of the mutual and constant interactions between patients and partners, the relationships between individual and dyadic coping behaviors are probably more multifaceted than suggested so far by existing models.

Proposing a new dyadic regulation model: the dyadic-regulation connectivity model

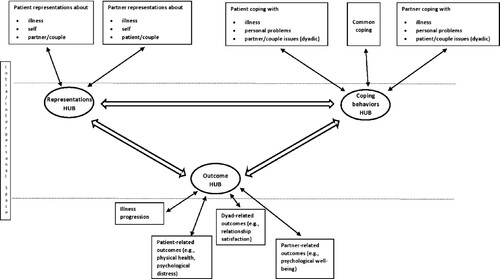

A major shortcoming of the dyadic regulation/coping models, besides those already discussed, is their persistence in designating a number of very specific pathways through which the main aspects of the dyadic regulation mechanism (e.g., appraisals, coping behaviors) are connected to each other. Yet, as argued above, the links between individual and dyadic appraisals, coping, and outcomes, may be more complex than a series of simple direct or even mediated relationships, or box-and-arrow scripts. It is more likely that these links function in a highly interactive mode and that they serve multiple causes (individual or dyadic) at the same time. In other words, it is possible for all these parameters and factors to cooperate as a network of elements which guide transactions with the environment. Dyadic regulation is more than just the sum or the combination of the individual responses of the members of the couple. In this regard, we should probably employ a different theoretical paradigm in order to better describe the multiple connections between the various aspects of the dyadic regulation network, as well as the several interactions between the individual and the dyadic levels of functioning. To this end, we are proposing a new model several aspects of which are based on previous theoretical models (especially, the Developmental Contextual Model, the Systemic Transactional Model, and the Common Sense Model), but also employs a novel connectivity paradigm that emphasizes the continuous interplay between personal and interpersonal processes as well as the organization of the various parts of the dyadic regulation mechanism into network hubs (see also, ).

The concepts of network hubs and connectivity have successfully been used in scientific fields such as cognitive neuroscience (e.g., Bertolero et al., Citation2018). Modern approaches in neuroscience describe the central nervous system as a complex system of continually changing networks that interactively process information in a dynamic way (Duffau, Citation2015). These networks contain communities of basic elements (e.g., neurons) that are closely connected to each other (Palva, Citation2018). Within these communities of basic elements, there are regions with a large number of connections, called ‘hubs’. These hubs have a central position and are especially significant for the overall organization of the network (van den Heuvel & Sporns, Citation2013). Hubs also connect and continuously interact with other hubs, permitting the integration of information and the formation of behavior (Bertolero et al., Citation2018). Thus, connectivity and interaction are the key aspects of the entire system (van den Heuvel & Sporns, Citation2013).

As with the dynamicity of the central nervous system, humans construct and reconstruct their experience in an endless way, so as to be able to effectively behave and adapt to challenges (Mlodinow, Citation2013). Of course, this is also true for patients and their partners, who base their reactions regarding illness on the integration and dynamic processing of all available information about illness and its symptoms and consequences, about the role of others, information coming from previous personal experience and cultural knowledge, as well as information regarding the broader personal goals, attitudes, beliefs, and expectations (Leventhal et al., Citation2005). In this context, we believe that the basic concepts of system connectivity and central network hubs can be used in novel models regarding the self- and dyadic-regulation mechanisms, so as to more accurately capture and describe their dynamicity, flexibility, and complexity. presents the key elements of the proposed Dyadic-Regulation Connectivity Model (DR-CM). In this model, hubs represent the conjunction points between the intra- and the inter-personal (i.e., dyadic) levels of regulation.

Figure 1. A schematic representation of the dyadic regulation connectivity model.

Note: The entire process is nested within and regulated by the self- and the dyadic-systems, and the broader socio-cultural context. Network hubs represent connections between the intra- and the interpersonal space.

The key elements of the DR-CM

The representations hub

According to the proposed model, patient representations of the entire illness experience, and of the role of self and others (e.g., partner) in illness, as well as partner corresponding representations are closely connected and in constant interaction. As suggested by the Common Sense Model (CSM), illness representations include cognitive beliefs about the illness (i.e., about its causes, identity, course, control, and consequences) as well as emotional reactions to illness (e.g., fear, guilt, sadness; Leventhal et al., Citation1980) while, not only illness-related representations are important aspects of the dyadic adaptation to illness and dyadic regulation. Representations regarding treatment and coping options, as well as expectations about self and the others, perceptions and evaluations of the broader environment, thoughts about current and future challenges and difficulties, evaluations of the couple’s relationship, assessment of available resources, etc., are all significant (and interacting) aspects of the appraisal part of the dyadic regulation mechanism.

To the extent that couples communicate, the overt or covert exchange of information and thoughts about their experience greatly affects everyone (Leventhal et al., Citation2005) and may result in the development, confirmation or modification of individual and joint representations. This is probably true, even when the members of the couple do not reveal their actual beliefs and emotions. After all, non-verbal communication (such as cues from voice and face) may convey more information than verbal, while individuals constantly try to infer other persons’ thoughts and intentions by examining their reactions and behavior (e.g., Apperly, Citation2010; Noller & Gallois, Citation1986). According to the proposed model, the interaction between patient and partner representations is continuous. Therefore, significant changes in personal or joint beliefs and emotions are expected as the outcome of the ‘dialogue’ between patient and partner self-regulation systems, especially during critical times over the illness trajectory. The shaping and reshaping of personal and joint representations, in combination with each person’s tendency to take into consideration the appraisals of their partner (Bodenmann, Citation1997), form a cognitive and emotional ‘representations hub’ which denotes the active discourse of patient and partner personal and shared representations, and it is this discourse which often guides behavior.

The coping behaviors hub

The representations hub is closely connected to a ‘coping behaviors hub’, which represents the active connections and constant interactions between patient and partner individual (i.e., directed to self), dyadic (i.e., couple or partner oriented), and common coping behaviors (i.e., the involvement of both partners in common actions). As in the case of representations, the DR-CM posits that all forms of individual, dyadic and common coping behaviors are interdependent. Specifically, the individual coping behaviors of a person are associated with their partner’s coping behaviors; individual coping shapes dyadic and common coping, and vice versa; individual coping behaviors may have a parallel dyadic purpose, while dyadic coping may also include a parallel individualistic goal. In this respect, individual, dyadic and common coping behaviors are mutually determined, and it’s probably their many interactions that impact outcomes at both the personal and the interpersonal level.

The ways persons and couples use coping strategies probably vary extensively. Depending on the particular situation, personal characteristics and the broader context, a person may first use some forms of individual coping (e.g., methods to regulate own emotions), and later ask their partner for help and assistance. Another person, or the same person in a different situation, may use both individual and common coping strategies at the same time (e.g., try to regulate own emotions, and also communicate their distress to their partner, asking for help). Yet, even these reactions are likely to depend on the particular interactions between individual and dyadic coping styles (such as the tendency to rely more on personal or on dyadic resources, or the impact of denial/avoidance which may prevent a person to ask for, use or provide support). It is more likely, however, that patients at times of crisis use every possible (and promising) source of coping available, personal and interpersonal, in order to better deal with the practical and emotional burden of an illness and its effects. The same is also likely to apply to partners in their effort to help patients and also deal with their own feelings and the impact of illness on themselves.

We believe that the complex relationships between representations and coping behaviors are better reflected as a connection between the two corresponding hubs, instead of a series of multiple direct or indirect associations between particular individual or dyadic representations and individual, dyadic or common coping behaviors. This may indeed be the case, to the extent that coping behaviors (e.g., the ways to manage illness symptoms) are related not only to the corresponding illness representations but also to other types of representations (e.g., regarding the impact of a given behavior on other persons), and given that a person’s coping behaviors are related not only to own but also to partner appraisals (e.g., Karademas et al., Citation2019).

The outcomes hub

The coping behaviors hub is also connected to an ‘outcomes hub’, which refers to the progress of illness, patient and partner adaptation to illness, and the impact of illness on their relationship. This hub may contain both perceived and actual outcomes. These is plenty of evidence about the significant relations of individual and dyadic coping to patient and partner outcomes and the quality of their relationship (e.g., Badr et al., Citation2010; Bertoni et al., Citation2015; Otto et al., Citation2015; Staff et al., Citation2017; Traa et al., Citation2015). In addition, all these outcomes are closely related to each other. For example, patients’ quality of life and illness prognosis is strongly associated with their partners’ health (e.g., Chung et al., Citation2009), while relationship quality is significantly related to patients’ well-being (e.g., Lepore & Helgeson, Citation1998; Manne, Citation1999).

In a feedback process, the outcome hub may affect the representations and the coping behaviors hubs. The content and/or the strength of the connections within the representations and coping behaviors hubs may also change as a result of the perceived or actual outcomes and the effectiveness of the coping behaviors to achieve the expected goals. As the CSM suggests, a positive outcome may reinforce existing representations and coping behaviors, whereas a less positive outcome may lead to a revision of these variables (Leventhal et al., Citation1980, Citation1992). Still, the entire process is complex as there is a multiplicity of outcomes that weigh on a person’s evaluation, while this may vary over time. For instance, in the early phases of a chronic condition, a patient or a partner may evaluate their illness representations and coping actions only against the effectiveness of their efforts to manage illness symptoms. In the later phases of the illness trajectory, the same persons may evaluate their representations and behavior against how their relationship is affected.

Basic features of the dyadic regulation connectivity model

The model tries to capture the complex interactions that take place at the interpersonal level, as well as between the personal and the interpersonal levels. As shown in , the new model has several similarities with the other models. For example, it puts emphasis on the role of communication between partners and illness-related and shared appraisals, within a developmental perspective, as the Systemic Transactional Model and the Developmental Contextual Model do as well. It also refers to individual, dyadic and common coping, employing the distinction made by the Systemic Transactional Model and the Cognitive-Transactional Model. On the other hand, the new model differs from the previous models in several ways, especially regarding its perspective on the complexity of the relationships between appraisals, coping behaviors and outcomes, the introduction of new concepts (e.g., hubs, dyadic coherence), and the ways of depicting the potential transactions between individual and dyadic factors.

In accordance with several other models (e.g., the DCM; Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007), the DR-CM also suggests that dyadic regulation is a dynamic process which changes over time and across the illness trajectory. Also, changes in any of its elements (e.g., the outcomes) and/or changes in the broader context (e.g., in the illness, the relationship) lead to changes in the entire system and the connections between its aspects.

The DR-CM posits that any network hub is fully responsive to changes in all other hubs. For example, partner representations affect own behavior, which in turn may affect patient representations and behavior which, through a feedback loop, may affect partner initial representations and so on (e.g., Karademas et al., Citation2019). Also, difficulties in performing a coping behavior may cause changes in patient and/or partner corresponding representations, sometimes regardless of the potential impact of this behavior on outcomes, while individual or dyadic/common coping behaviors may change relevant representations or even generate new ones. In the same way, it is possible that the coping behaviors hub does not always mediate the relationship between the representations hub and the outcomes hub. For example, changes in patient illness representations (e.g., about illness severity), as a result of new information coming from a medical examination, may have a direct impact on certain outcomes (e.g., self-rated health) which, in turn, may also impact other outcomes (e.g., partner’s well-being). Outcomes may also directly impact behavior. For instance, negative changes in the relationship quality may affect the implementation of certain dyadic coping behaviors (e.g., preparing healthy meals for the family) without any changes in the ways that the partner or the patient evaluates the actual significance of this particular behavior. (Changes in the corresponding representations may be noticed later as a result of the changes in the implementation of this behavior – e.g., as an excuse for not preparing healthy meals anymore.) In other words, the entire system is a ‘living’ mechanism which is continuously constructed and reconstructed in the mind and the behaviors of the individuals and the couples. Thus, significant changes in any aspect or connection may trigger immediate and synchronized changes throughout the mechanism.

The model posits that the entire dyadic regulation mechanism is nested within the self- (e.g., personal goals and roles) and the dyadic-system (or family system; e.g., the developmental stage of the family), as well as the broader context. As suggested by several other models (e.g., Acitelly & Badr, Citation2005; Falconier et al., Citation2016; Staff et al., Citation2017), this model also suggests that patient and partner personal variables (e.g., gender and age; attitudes and beliefs; health status; traits and personal characteristics; such as optimism or self-efficacy), their personal habits, experience, and biological characteristics, dyadic/family characteristics (e.g., relationship satisfaction or differences in coping styles), the special characteristics of and demands imposed by the disease, the broader cultural/ecological background (e.g., the impact of individualistic vs. collectivistic values on the communication style and the ways of appraising and coping with stressful conditions), and the social environment (e.g., daily life demands, health-related stimuli) all can affect the entire process and have an impact on the connections between the different parts of the dyadic regulation mechanism.

These factors may not be equally important at all times. It is possible for different factors to be crucial at different times across the trajectory of illness (as also suggested by Berg & Upchurch, Citation2007), or with respect to the different aspects of the dyadic regulation mechanism. For instance, personal old habits may exert more influence on coping behaviors at the later phases of illness than soon after diagnosis. In the same vein, the relationship quality may be less influential at the early stages of illness, when partners focus on helping the patients overcome the immediate threat, than later, when the danger is considered as more controllable.

A significant aspect of the illness-related self-regulation is coherence. According to the Common Sense Model (CSM), coherence refers to the consistency among the various parts of the self-regulation mechanism (e.g., illness representations and coping plans) and the patient perception that their behavior succeeds in managing the symptoms of illness or getting better (Leventhal et al., Citation2005; Phillips et al., Citation2013). Thus, coherence corresponds to a positive feedback between the several parts of self-regulation and the expected outcomes or goals (Phillips et al., Citation2013). The CSM suggests that coherence is a critical factor for adaptation, since a coherent system secures the continuation of a specific behavior, which is perceived as successful, whereas a non-coherent system may lead to changes in representations or behavior (Tanenbaum et al., Citation2015). In this sense, coherence is probably important for dyadic regulation as well, as it may function as a special feedback mechanism ensuring its effectiveness. A negative or undesired outcome related to patient or partner health condition, or to their relationship, may cause changes in either or both persons’ representations and/or coping behaviors. On the contrary, a coherent dyadic regulation may conduce to the prolongation of the existing representations and behaviors, which are evaluated by the couple as ‘correct’ in achieving the expected goals.

Coherence at the dyadic level does not mean the absence of any incongruence in patient and partner representations or behaviors. It is likely that some dissimilarities may even be beneficial in the long run. Differences in patient and partner understanding of and dealing with illness, to the extent that they are not associated with conflicting or incompatible behaviors (e.g., when a patient tries to improve their diet, but the spouse opposes such a change), might be useful (a) as an important source of information that offers both partners with the opportunity to cross-examine the accuracy of own representations or the effectiveness of their behavior and probably change them, (b) as a way of counterbalancing negative and ineffective approaches to the stressful condition, like a person’s erroneous representation of illness as uncontrollable (e.g., Giannousi et al., Citation2016). In this respect, even incongruence may sometimes contribute to the overall effectiveness and the long-term coherent function of the dyadic regulation mechanism.

Finally, it should be noted that not only conscious or rational processes take place within the dyadic regulation mechanism. As in self-regulation (e.g., Breland et al., Citation2012), automatic processes are also important. Biases and ‘errors’ in information processing and decision making, and unrealistic appraisals or expectations, which may lead to maladaptive behaviors, are common in everyday life, including health (Sjöberg, Citation2003; St Claire et al., Citation1996; Weinstein, Citation1984). There is substantial evidence regarding the significant role of such automatic processes in self-regulation (Orbell & Phillips, Citation2019) but, given their great impact on perceptions, emotions and behavior (Mlodinow, Citation2013), it is possible that automatic processes also guide several aspects of the dyadic regulation system as well (e.g., implicit attitudes; spontaneous cognitive, affective and behavioral responses to each other’s expressions of emotion). Hence, a systematic examination of this issue is warranted.

Implications for research

The proposed model bears a number of implications for research. First, it urges researchers to closely examine the multiple pathways and interactions that take place in the dyadic regulation mechanism as it evolves over time. Second, it calls for the examination of the relationships between the proposed network hubs in diverse and novel ways, beyond the typical ‘representations – coping – outcomes – revised representations etc.’ axis, as the model suggests the existence of multiple and parallel relations and interactions, and even synchronized changes across the different elements of the mechanism.

Third, the connectivity model implies that the changes in the dyadic regulation processes may not always be easily observable. For example, these changes may not refer only to alterations in representations and coping behaviors, but also to changes in the ways that the different aspects and elements of the regulation mechanism are connected to each other or in the strength of these connections. Finally, the model posits that there is a multiplicity of effects (e.g., on patient and partner health, the relationship between partners, etc.) which are strongly interrelated and, therefore, should be considered and examined together.

To achieve the above described research goals, more advanced dyadic study methods and statistical analyses are required. The use of longitudinal study designs with multiple assessment points of individual and dyadic variables (appraisals, coping, characteristics, etc.) and outcomes will serve as the starting point for the examination of the complex relationships suggested by the DR-CM. Additionally, the use of observational and physiological measures will allow the investigation of the processes that may be difficult to observe (e.g., subtle interactions between partners). For instance, new methods for the analysis of real-time interactions between partners, which have been developed within the context of Ecological Momentary Assessment and analyze the language used (such as pronouns, emotion words) by both partners in videotaped interviews (e.g., Lau et al., Citation2019; Rentscher, Citation2019), could be used to better define dyadic regulation processes at the micro-level. Also, the joint use of well-established methods for designing dyadic studies and analyzing relevant data (such as the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model; Kenny, Citation1996; Kenny & Cook, Citation1999) and elaborated algorithms for the identification of the complicated connections between dyadic variables (e.g., in a machine-learning context) will facilitate the examination of the predictive validity of the DR-CM.

The use of more elaborated studies and data analysis methods will permit the examination of the theoretical accuracy of the new model in ‘contrast’ to the existing ones. Topics that may serve as the first evaluation points for the new model may include: (a) the examination of the diverse perspectives on the role of individual coping (e.g., serial/sequential use of individual and dyadic coping vs. parallel use and interaction); (b) the potential interactions between individual appraisals, dyadic appraisals, and dyadic coping; (c) the role of the dyadic regulation coherence as defined in the new model.

A conclusion note

Existing dyadic coping/dyadic regulation models have promoted the understanding of the dyadic regulation processes in the context of chronic illness. Yet, these models are also faced with certain research-related (e.g., relevant studies have focused far more on relationship functioning than physical well-being) and theoretical limitations especially regarding the interplay between individual and dyadic factors. Thus, here we propose a new model regarding the connections among the patient and partner variables that are important for dyadic regulation and adaptation to illness. The Dyadic Regulation Connectivity Model (DR-CM) underlines the significance of the network connectivity between individual and dyadic appraisals, coping, and outcomes, which guides the transactions with the environment and the specific situation (i.e., the illness). The DR-CM adopts several points of the previous models (especially, the Developmental Contextual Model, the Systemic Transactional Model, and the Common Sense Model), but it also takes a big step forward. By emphasizing the importance of both individual and dyadic factors, it aims to depict the complex and continuous interchange between the personal and interpersonal levels of dyadic regulation and adaptation to illness.

The model introduces central network ‘hubs’ as a concept more able to accurately describe the dialog between the patient and the partner regulation systems, as well as the ‘space’ in which constant and dynamic interpersonal (i.e., patient and partner) interactions take place. The model describes three main network hubs. The representations hub refers to the interactions between the patient and partner cognitive and emotional representations of illness, treatment, and coping options, and each person’s perceptions about self and the other. The coping behaviors hub refers to the connections between patient and partner individual and dyadic (couple or partner oriented) and common coping behaviors. The outcomes hub refers to patient and partner health, well-being and adaptation to illness, illness progression, and the impact of the condition on the couple’s relationship. The DR-CM suggests that dyadic regulation processes evolves over time, while all network hubs are fully responsive to changes in any part of the mechanism. It also suggests that the entire dyadic regulation mechanism is nested within the self- and the dyadic-system, the illness and the broader socio-cultural context.

Much more theoretical work and, of course, research efforts are warranted to refine and further develop the concepts included in the model; to better describe the many connections between the several factors of the model; to examine the relationships and test the processes delineated in it. Βy using a novel perspective, we hope that this model will contribute to the better understanding of the complex processes that take place in dyadic adaptation to chronic illness, as well as to a more accurate theoretical and research approach to dyadic regulation. Finally, we believe that the proposed connectivity model may also be useful in order to achieve a more accurate understanding of the processes that take place within self-regulation as well.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acitelly, L. K., & Badr, H. J. (2005). My illness or our illness? Attending to the relationship when one partner is ill. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress. Emerging perspective on dyadic coping (pp. 121–136). American Psychological Society.

- Acquati, C., & Kayser, K. (2019). Dyadic coping across the lifespan: A comparison between younger and middle-aged couples with breast cancer. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00404

- Apperly, I. (2010). Mindreaders: The cognitive basis of “theory of mind”. Psychology Press.

- Applebaum, A., & Breitbart, W. (2013). Care for the cancer caregiver: A systematic review. Palliative and Supportive Care, 11(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951512000594

- August, K. J., Rook, K. S., Parris Stephens, M. A., & Franks, M. M. (2011). Are spouses of chronically ill partners burdened by exerting health-related social control? Journal of Health Psychology, 16(7), 1109–1119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311401670

- Baanders, A., & Heijmans, M. (2007). The impact of chronic diseases. The partner’s perspective. Family & Community Health, 30(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.FCH.0000290543.48576.cf

- Badr, H., & Acitelli, L. K. (2017). Re-thinking dyadic coping in the context of chronic illness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 44–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.03.001

- Badr, H., & Carmack Taylor, C. L. (2008). Effects of relationship maintenance on psychological distress and dyadic adjustment among couples coping with lung cancer. Health Psychology, 27(5), 616–627. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.616

- Badr, H., Carmack Taylor, C. L., Kashy, D. A., Cristofanilli, M., & Revenson, T. A. (2010). Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychology, 29(2), 169–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018165

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. (1963). Social learning and personality development. Holt.

- Barnoy, S., Bar-Tal, Y., & Zisser, B. (2006). Correspondence in informational coping styles: How important is it for cancer patients and their spouses? Personality and Individual Differences, 41(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.12.013

- Ben-Zur, H., Gilbar, O., & Lev, S. (2001). Coping with breast cancer: Patient, spouse, and dyad models. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200101000-00004

- Benyamini, Y., Gozlan, M., & Kokia, E. (2009). Women’s and men’s perceptions of infertility and their associations with psychological adjustment: A dyadic approach. British Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708X279288

- Berg, C. A., Meegan, S. P., & Deviney, F. P. (1998). A social contextual model of coping with everyday problems across the life span. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 22(2), 239–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/016502598384360

- Berg, C. A., & Upchurch, R. (2007). A developmental-contextual model of couples coping with chronic illness across the adult life span. Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), 920–954. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.6.920

- Berg, C. A., Wiebe, D. J., Hayes, J., Butner, J., Bloor, L., Bradstrees, C., & Upchurch, R. (2008). Collaborative coping and daily mood in couples dealing with prostate cancer. Psychology & Aging, 23(3), 505–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012687

- Bertolero, M. A., Yeo, B. T. T., Bassett, D. S., & D’Esposito, M. (2018). A mechanistic model of connector hubs, modularity and cognition. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(10), 765–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0420-6

- Bertoni, A., Donato, S., Graffigna, G., Barello, G., & Parise, M. (2015). Engaged patients, engaged partnerships: Singles and partners dealing with an acute cardiac event. Psychology, Health, and Medicine, 20(5), 505–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.969746

- Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping – A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. European Review of Applied Psychology, 47, 137–140.

- Bodenmann, G. (2000). Stress and coping in couples. Hogrefe [in German].

- Bodenmann, G. (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In T. A. Revenson, K. Kayser, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–50). American Psychological Association.

- Bodenmann, G., Randall, A. K., & Falconier, M. K. (2016). Coping in couples. The systemic transactional model (STM). In M. K. Falconier, A. K. Randall, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress. A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 5–22). Routledge.

- Bowen, C., Maclehose, A., & Beaumont, J. G. (2011). Advanced multiple sclerosis and the psychosocial impact on families. Psychology and Health, 26(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903287934

- Breland, J. Y., Fox, A. M., Horowitz, C. R., & Leventhal, H. (2012). Applying a common-sense approach to fighting obesity. Journal of Obesity, 2012, 710427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/710427

- Christakis, N. A., & Allison, P. D. (2006). Mortality afterthe hospitalization of a spouse. The New England Journal of Medicine, 354(7), 719–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa050196

- Chung, M. L., Moser, D. K., Lennie, T. A., & Kay Rayens, M. (2009). The effects of depressive symptoms and anxiety on quality of life in patients with heart failure and their spouses: Testing dyadic dynamics using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 67(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.01.009

- Coyne, J. C., & Smith, D. A. F. (1991). Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: A contextual perspective on wives’ distress. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 404–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.3.404

- Dagan, M., Sanderman, R., Schokker, M. C., Wiggers, T., Baas, P. C., van Haastert, M., & Hagedoorn, M. (2011). Spousal support and changes in distress over time in couples coping with cancer: The role of personal control. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(2), 310–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022887

- Dekel, R., Vilchinsky, N., Liberman, G., Leibowitz, M., Khaskia, A., & Mosseri, M. (2014). Marital satisfaction and depression among couples following men’s acute coronary syndrome: Testing dyadic dynamics in a longitudinal design. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19(2), 347–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12042

- DeLongis, A., & O’Brien, T. B. (1990). An interpersonal framework for stress and coping: An application to the families of Alzheimer’s patients. In M. A. P. Stephens, J. H. Growther, S. E. Hobfoll, & D. L. Tennenbaum (Eds.), Stress and coping in later-life families (pp. 221–239). Hemisphere.

- Dempster, M., McCorry, N. K., Brennan, E., Donnelly, M., Murray, L. J., & Johnston, B. T. (2011). Illness perceptions among carer-survivor dyads are related to psychological distress among oesophageal cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70(5), 432–439. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.07.007

- Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046408

- Duffau, H. (2015). Stimulation mapping of white matter tracts to study brain functional connectivity. Nature Reviews Neurology, 11(5), 255–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.51

- Elliott, T. R., & Shewchuk, R. M. (2005). Family adaptation in illness, disease, and disability. In T. Boll, J. M. Raczynski, & L. C. Leviton (Eds.), Handbook of clinical health psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 379–403). American Psychological Association.

- Fagundes, C. P., Berg, C. A., & Wiebe, D. J. (2012). Intrusion, avoidance, and daily negative affect among couples coping with prostate cancer: A dyadic investigation. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(2), 246–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027332

- Falconier, M. K., & Kuhn, R. (2019). Dyadic coping in couples: A conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00571

- Falconier, M. K., Randall, A. K., & Bodenmann, G. (2016). Cultural considerations in understanding dyadic coping across cultures. In M. K. Falconier, A. K. Randall, & G. Bodenmann (Eds.), Couples coping with stress. A cross-cultural perspective (pp. 23–34). Routledge.

- Feldman, B. N., & Broussard, C. A. (2006). Men’s adjustment to their partners’ breast cancer: A dyadic coping perspective. Health & Social Work, 31(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/31.2.117

- Franks, M. M., Lucas, T., Stephens, M. A. P., Rook, K. S., & Gonzalez, R. (2010). Diabetes distress and depressive symptoms: A dyadic investigation of older patients and their spouses. Family Relations, 59(5), 599–610. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00626.x

- French, D. P. (2015). Self-efficacy and health. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 509–514). Elsevier.

- Giannousi, Z., Karademas, E. C., & Dimitraki, G. (2016). Illness representation and psychological adjustment of Greek couples dealing with a recently diagnosed cancer: Dyadic, interaction and perception-dissimilarity effects. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(1), 85–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-015-9664-z

- Given, B., Kozachik, S., Collins, C., Devoss, D., & Given, C. W. (2001). Caregiver role strain. In M. Maas, K. Buckwalter, M. Hardy, T. Tripp-Reimer, & M. Titler (Eds.), Nursing care of older adults diagnosis: Outcome and interventions (pp. 679–695). Mosby.

- Hagedoorn, M., Dagan, M., Puterman, E., Hoff, C., Meijerink, W. J. H. J., Delongis, A., & Sanderman, R. (2011). Relationship satisfaction in couples confronted with colorectal cancer: The interplay of past and current spousal support. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 34(4), 288–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-010-9311-7

- Hagedoorn, M., Kuijer, R. G., Buunk, B. P., DeJong, G. M., Wobbes, T., & Sanderman, R. (2000). Marital satisfaction in patients with cancer: Does support from intimate partners benefit those who need it most? Health Psychology, 19(3), 274–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.274

- Hagedoorn, M., Puterman, E., Sanderman, R., Wiggers, T., Baas, P. C., van Haastert, M., & DeLongis, A. (2011). Is self-disclosure in couples coping with cancer associated with improvement in depressive symptoms? Health Psychology, 30(6), 753–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024374

- Hagger, M. S., Koch, S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., & Orbell, S. (2017). The common-sense model of self-regulation: Meta-analysis and test of a process model. Psychological Bulletin, 143(11), 1117–1154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000118

- Helgeson, V. S., Berg, C. A., Kelly, C. S., Van Vleet, M., Zajdel, M., Tracy, E. L., & Litchman, M. L. (2019). Patient and partner illness appraisals and health among adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42(3), 480–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-0001-1

- Helgeson, V. S., Jakubiak, B., Van Vleet, M., & Zajdel, M. (2018). Communal coping and adjustment to chronic illness: Theory update and evidence. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(2), 170–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317735767

- Hickman, R. L., Jr., & Douglas, S. L. (2010). Impact of chronic critical illness on the psychological outcomes of family members. AACN Advanced Critical Care, 21, 80–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NCI.0b013e3181c930a3

- Hinnen, C., Hagedoorn, M., Ranchor, A. V., & Sanderman, R. (2008). Relationship satisfaction in women: A longitudinal case-control study about the role of breast cancer, personal assertiveness, and partners’ relationship-focused coping. British Journal of Health Psychology, 13(4), 737–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910707X252431

- Joekes, K., Maes, S., & Warrens, M. (2007). Predicting quality of life and self-management from dyadic support and overprotection after myocardial infarction. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(4), 473–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910706X118585

- Johnson, M. D., Anderson, J. R., Walker, A., Wilcox, A., Lewis, V. L., & Robbins, D. C. (2014). Spousal protective buffering and type 2 diabetes outcomes. Health Psychology, 33(8), 841–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000054

- Johnson, M. D., Anderson, J. R., Walker, A., Wilcox, A., Lewis, V. L., & Robbins, D. C. (2015). Spousal overprotection is indirectly associated with poorer dietary adherence for patients with type 2 diabetes via diabetes distress when active engagement is low. British Journal of Health Psychology, 20(2), 360–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12105

- Karademas, E. C., Dimitraki, G., Thomadakis, C., & Giannousi, Z. (2019). The relation of spouse illness representations to patient representations and coping behavior: A study in couples dealing with a newly diagnosed cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 37(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2018.1508534

- Karademas, E. C., & Thomadakis, C. (2020). The interpersonal impact of partner emotion regulation on chronic cardiac patients’ functioning through affect. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 43(2), 262–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00105-5

- Keller, J., Wiedemann, A. U., Hohl, D. H., Scholz, U., Burkert, S., Scrader, M., & Knoll, N. (2017). Predictors of dyadic planning: Perspectives of prostate cancer survivors and their partners. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12216

- Kenny, D. A. (1996). Models of non-independence in dyadic research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(2), 279–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407596132007

- Kenny, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (1999). Partner effects in relationship research: Conceptual issues, analytic difficulties, and illustrations. Personal Relationships, 6(4), 433–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00202.x