ABSTRACT

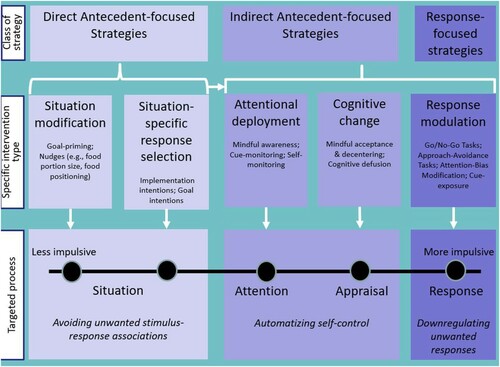

While previous frameworks to address health behaviours through targeting underlying automatic processes have stimulated an improved understanding of related interventions, deciding between intervention strategies often remains essentially arbitrary and atheoretical. Making considered decisions has likely been hampered by the lack of a framework that guides the selection of different intervention strategies targeting automatic processes to reduce unhealthy behaviours. We propose a process framework to fulfil this need, building upon the process model of emotion regulation. This framework differentiates types of intervention strategies along the timeline of the unfolding automatic response, distinguishing between three broad classes of intervention strategies – direct antecedent, indirect antecedent, and response-focused. Antecedent-focused strategies aim to prevent the exposure to or activation of automatic responses directly through the avoidance of unwanted stimulus-response associations (i.e., situation modification or situation-specific response selection), or indirectly through automatising self-control (i.e., attentional deployment or cognitive change). Response-focused strategies aim to directly downregulate automatic unwanted responses (i.e., response modulation). Three main working hypotheses derived from this process framework provide practical guidance for selecting interventions, but await direct testing in future studies.

In recent years, an increasing emphasis has been placed upon the central importance of targeting ‘automatic’Footnote1 processes for changing human health behaviours to prevent disease (Marteau et al., Citation2012). This is reflected for instance in evidence that interventions that alter environmental cues and underlying automatic processes, defined as habits, impulses, hedonic goals or stereotypic associations (Papies, Citation2017), appear to have more and broader impact on human health behaviours than do traditional educational approaches that mostly reach higher socioeconomic status populations (McGill et al., Citation2015). People are often ‘seduced’ by omnipresent palatable cues in their environment. These cues can trigger automatic responses that interfere with the enaction of healthy behaviours. For instance, seeing or smelling palatable food may result in sudden food cravings and unplanned food consumption. An important challenge lies in intervening on these substantially, even wholly, automatic processes. While previous frameworks to address health behaviours through targeting underlying automatic processes have stimulated an improved understanding of related interventions (Friese et al., Citation2011; Hollands et al., Citation2016; Papies, Citation2017), deciding between intervention strategies often remains essentially arbitrary and atheoretical. Making considered decisions has likely been hampered by the lack of a framework that guides the selection of different intervention strategies targeting automatic processes to reduce unhealthy behaviours. We propose a process framework to fulfil this need. Three main working hypotheses derived from this process framework provide practical guidance for selecting interventions, but await direct testing in future studies. The framework is in line with a ‘personalized medicine’ approach towards health (i.e., precision public health) that aims to provide ‘the right intervention to the right population at the right time’ (Khoury et al., Citation2016). As such, it offers ways to help researchers and practitioners consider when less is enough and more is not more effective for some people, whereas for others more intensive intervention is needed. This fits well with recent prominent policy perspectives (Gjødsbøl et al., Citation2019; Tarkkala et al., Citation2019). It is intended that this new framework can provide promising future avenues for selecting and testing future health intervention strategies that may bridge often reported intention-behaviour gaps, singly and in combination with one another.

A process model of intervention techniques targeting automatic processes

summarises our conceptual process framework of intervention techniques targeting automatic processes, build upon the process framework of emotion regulation (Gross, Citation1998, Citation2001). Notably, our main goal is not the specification of when interventions are automatic (Hollands et al., Citation2016), nor to contribute another framework categorising different intervention techniques. There are abundant better alternatives of well-developed frameworks to precisely categorise techniques, including the Behaviour Change Technique (BCT) Taxonomy (Michie et al., Citation2013) and the recent Typology of Interventions in Proximal Physical Micro-Environments (TIPPME) (Hollands et al., Citation2017). Compared to these frameworks, our categorisation is necessarily an oversimplification. Our goal is instead to propose a process framework that guides the selection of different intervention strategies targeting automatic processes to reduce unhealthy behaviours (i.e., discourage or decrease automatic enactment or performance of a behaviour with negative health consequences). To facilitate this goal, our framework categorises strategies according to how and for whom they target automatic processes. We also include intervention strategies that target reduction of unhealthy behaviours by encouraging healthier behaviours. If health professionals (i.e., clinicians and/or researchers) aim to help people who experience problems with translating health intentions into behaviours, our framework may provide initial guidance that helps in selecting strategies with the potential to bridge this intention-behaviour gap.

Figure 1. A process model of intervention techniques changing automatic processes, inspired by the process model of emotion regulation. Note: The exemplar antecedent and response-focused intervention strategies are not meant to be exhaustive.

This model differentiates types of intervention strategies along the timeline of the unfolding automatic response. Intervention strategies can operate at different ‘levels’ of this unfolding response. At the broadest level, we distinguish between antecedent-focused and response-focused intervention techniques. Antecedent-focused strategies aim to prevent the exposure to or activation of automatic unwanted responses. In contrast, response-focused strategies aim at directly downregulating automatic unwanted (i.e., impulsive) responses. We further distinguish between two sub-forms of antecedent-focused strategies: Direct and indirect. Direct antecedent-focused strategies aim to prevent automatic unwanted responses directly through the avoidance of specific unwanted stimulus-response associations. This can be done by modifying situations (e.g., putting a fruit bowl at the table) to facilitate goal responses or by selecting different situations, through for instance forming goal intentions (e.g., not going to the supermarket when being hungry) and/or implementation intentions (e.g., ‘If I am hungry, I am going to cook a healthy meal instead of going to a fast-food restaurant’). Moreover, indirect antecedent-focused strategies aim to (further) change these automatic responses through the reinforcement of the ability to self-control by automatising self-control and executive functioning. This can be done by attentional deployment (e.g., paying mindful attention to eating a meal) or cognitive change (e.g., using decentring techniques where people are instructed to look at the food images and think about their reactions to foods as constructions of the mind, which appear and disappear). Finally, response-focused strategies aim directly at downregulating automatic unwanted (i.e., impulsive) responses through response modulation and directly changing automatic associations, attentional biases and approach-avoidance tendencies (e.g., cognitive bias modification procedures to change reactions to cues). Importantly, strategies are not ‘limited’ to their first and main proposed working mechanism. They may eventually also change other mechanisms during the unfolding automatic response. For instance, direct antecedent-focused strategies that work principally through the avoidance of specific unwanted stimulus-response associations may eventually, when proven successful, also begin to automatise self-control and in the long term may even break old habits when new ones have been formed.

Three main hypotheses can be derived from our process framework that provide practical guidelines for intervention selection. First, direct antecedent-focused strategies work better for individuals who are less impulsive, while response-focused strategies work better for those who are more impulsive. Second, if direct antecedent-focused strategies are successful, it might not make sense to expose people to response-focused strategies to downregulate further responses as well (i.e., searching for interaction) because people do not need to train changes in the underlying processing of cues they are no longer (i.e., physically or mentally) affected by. Third, direct antecedent-focused strategies (i.e., situation modification and situation-specific response selection) may be used to initiate and maintain performance on indirect antecedent-focused or response-focused intervention strategies (e.g., prompting people to apply mindfulness strategies).

In the following sections we outline and discuss different types of antecedent-focused and response-focused strategies. We have used key exemplar intervention techniques of direct antecedent-focused (i.e., goal priming and implementation intentions), indirect antecedent-focused (i.e., mindfulness) and response-focused (i.e., Go/No-Go tasks) strategies to illustrate our process framework. These exemplar intervention techniques were chosen based on their potential as effective ‘stand-alone’ interventions, rather than as ‘adjunct’ interventions to established treatments (Wiers et al., Citation2018), for altering unhealthy behaviours and bridging intention-behaviour gaps through changes in automatic processes. Notably, under each class of strategies, these are presented as example approaches within a much wider range of possible strategies (see also ). The defining characteristic of these strategies is that they target automatic processes, rather than that they are necessarily designed to be engaged with automatically. For example, implementation intentions and mindfulness interventions likely initially require conscious engagement with their content, but are considered exemplar intervention techniques as they influence behaviour through substantially automatic processes. We will first discuss state-of-the art research with regard to these exemplar techniques, paying explicit attention to potential moderators and mechanisms, also referring to the first two hypotheses. Then, we provide illustrative example evidence of whether and how direct antecedent-focused interventions may activate the use and maintenance of other interventions (i.e., the third hypothesis). We end this paper with a general discussion and recommendations for future research.

Direct antecedent-focused strategies

Situation modification: goal priming

Goal priming refers to the provision of health-related cues or primes to influence automatic attention, using external situational cues to activate a health goal and to avoid unhealthy stimulus-response associations, thus shifting attention towards goal-relevant stimuli (Papies, Citation2017). With ‘goal priming’ we refer to situation modification (see ), specifically ‘labelling’ and ‘prompting’ actions activating people’s health goals, including communication of explicit textual, numeric, or pictorial information, in accordance with the TIPPME framework (Hollands et al., Citation2017). Other exemplar techniques categorised and summarised by the TIPPME framework (Hollands et al., Citation2017) that work through changes made in the environment are interventions based on sizing (e.g., food portion sizes) and placing (e.g., proximity of healthy dietary products). These interventions elicit their effects mostly outside people’s consciousness, with people often not being aware of the external stimulus (the intervention) or their resulting behaviour. As they rely less on reflective conscious engagement, they probably have a more significant potential for changing behaviour across populations (Hollands et al., Citation2016).

In line with a normative framework (Herman & Polivy, Citation2008), we propose that particularly the normative types of ‘situation modification’ techniques (e.g., portion size) may affect everyone, while the more ‘goal-dependent’ types (e.g., goal priming) have a more powerful effect on subgroups of people motivated to change health behaviours, given that a goal-dependent act is one that depends on its goal for its occurrence (Moors & De Houwer, Citation2006). Specifically, goal priming facilitates avoidance of unhealthy stimulus-response associations by increasing focus on prime-congruent goal items or cues (i.e., referring to the specific underlying working mechanism of goal-priming) (Van der Laan et al., Citation2017). It is thus not surprising that diverse studies have shown effects of goal primes on healthy eating consumption behaviours (e.g., buying more healthy snacks when primed with healthy images) specifically among subgroups of dieters, restrained eaters or people with overweight (Papies & Hamstra, Citation2010; Stämpfli et al., Citation2017; Stämpfli & Brunner, Citation2016). These findings are further supported by meta-analyses (Buckland et al., Citation2018; Weingarten et al., Citation2016), suggesting that priming effects are goal dependent and thus only work when the primes are motivationally and goal-relevant for people.

Situation-specific response selection: implementation intentions

The formation of ‘implementation intentions’ (‘if–then-plans’) is a widely used strategy to help people achieve their goals (Carrero et al., Citation2019) and to decrease their existing unwanted habits by forming new replacement plans (Adriaanse & Verhoeven, Citation2018; Adriaanse, van Oosten, et al., Citation2011). That is, people formulate specific situations (and potential cues they encounter) by way of the ‘if’ status (e.g., ‘IF I get out of bed at 8 am’), and their desired (i.e., healthier replacement) reaction by way of the ‘then’ statement (e.g., ‘THEN I will first go for a walk’). Implementation intentions have been proposed to influence behaviour in two rather ‘automatic’ ways (Gollwitzer, Citation1999): (1) increasing the accessibility of the mental representation of the anticipated environmental cue (Aarts et al., Citation1999) and (2) strengthening the link between the planned situation and the goal-directed response (Webb & Sheeran, Citation2007). These mechanisms call on automatic processes to secure goal attainment specifically (Gollwitzer, Citation1999). We include the formation of implementation intentions as a specific case of ‘situation-specific response selection’, given the focus of this strategy on cueing by situational features and increasing access to the mental representation of anticipated cues and subsequent cue-action links. By way of implementation intentions, people use relatively simple tasks that do not require repeated or intensive training of stimulus-response associations (as in response-focused tasks). Importantly, the previously existing unwanted stimulus-response associations remain (i.e., are still equally strongly related to the critical situation) and are thus not directly downregulated or changed via the formation of implementation intentions (Adriaanse, Gollwitzer, et al., Citation2011). As such, forming implementation intentions is similar to other (direct) antecedent-focused strategies (e.g., goal priming) that prevent the exposure to or activation of automatic unwanted responses by increasing focus on goal cues and goal-cue action links.

Formation of implementation intentions has yielded promising effects on diverse health behaviours, including healthy eating and alcohol consumption (Adriaanse, Vinkers, et al., Citation2011; Turton et al., Citation2016; Vila et al., Citation2017). Meta-analyses have on average reported medium effects of implementation intentions on health-related behaviours (Carrero et al., Citation2019; Gollwitzer & Sheeran, Citation2006). However, effects may vary as a function of behaviours targeted, individual characteristics and intervention conditions. To date, the use of implementation intentions has a significantly larger effect for individuals with higher than lower motivation to perform goal-directed behaviour (Hagger & Luszczynska, Citation2014; Prestwich et al., Citation2014), for individuals lower compared to higher in impulsivity (Churchill & Jessop, Citation2010; Churchill & Jessop, Citation2011; Hagger & Luszczynska, Citation2014), for healthy than unhealthy behaviours (Carrero et al., Citation2019), and for single and specific if–then plans than multiple and complex plans (Carrero et al., Citation2019; Forcano et al., Citation2018). Thus, evidence on moderating factors clearly shows that ‘healthy’ and ‘simple’ implementation intentions seem to work best among ‘highly motivated’ individuals, similar to goal priming. Moreover, the moderating effects of impulsivity are in line with the first hypothesis of our conceptual model (i.e., ‘direct antecedent-focused strategies work better for individuals who are less impulsive, while response-focused strategies work better for those who are more impulsive’).

Moreover, findings of three studies are rather unanimous in their conclusion that combining the use of simple and specific implementation intentions with a Go/No-Go task (i.e., response-focused strategy) did not lead to additive effects on reduction of self-selected portion size of palatable food or amount of weight loss (Van Koningsbruggen et al., Citation2013; Veling et al., Citation2014). These findings are in line with the second hypothesis of our conceptual model, suggesting that if (single, specific and healthy) implementation intentions are successful, it might not make sense to expose people to response-focused strategies to downregulate further responses as well (i.e., searching for interaction) because people do not need to train changes in the underlying processing of cues they are no longer (i.e., physically or mentally) affected by.

Indirect antecedent-focused strategies

Attentional deployment & cognitive change: mindfulness

The aim of mindfulness-based interventions is to increase a state or meta-cognitive perspective of mindfulness in which people learn to experience present moment experiences with awareness and non-judgment or acceptance (Creswell, Citation2017). Mindfulness contributes to changes in automatic responding (Kang et al., Citation2013; Lueke & Gibson, Citation2015). There are many forms of mindfulness interventions with different durations, ranging from 3-months retreats to very brief mindfulness interventions with a duration of 30 min or less on any occasion and ranging no longer than 4 weeks (Creswell et al., Citation2019; Howarth et al., Citation2019). Despite the well-known effects of mindfulness on mental health states, recent studies have shown that mindfulness can also improve physical health and health-related (addictive) behaviours, with changes in mindfulness linked to better outcomes (Alsubaie et al., Citation2017; Creswell et al., Citation2019).

Mindfulness is a multicomponent treatment. Three components that might particularly exert effects are awareness (i.e., continuously monitoring one’s momentary experiences), acceptance (i.e., letting experiences come and go without judging them) and disidentification or decentring (i.e., distinguishing oneself as separate from the experiences). Recent randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provide promising evidence that awareness (i.e., monitoring) combined with acceptance skills training may be a necessary component for particularly decreasing stress ratings, objective stress measures and boosting positive emotions in daily life compared to monitoring alone (Chin et al., Citation2019; Lindsay et al., Citation2018; Lindsay & Creswell, Citation2019). In contrast, acceptance provides limited effects as a skill to cope with cravings (Tapper, Citation2017, Citation2018). To deal with cravings (i.e., food) and resultant health behaviours disidentification (i.e., decentring) proves to be a promising strategy (Keesman et al., Citation2017; Papies et al., Citation2016; Tapper & Turner, Citation2018). While reason-based paradigms may be a ‘losing a battle with urges’, mindfulness-based strategies may be paramount to dealing with reward-based learning to change addictive health behaviours (Brewer, Citation2019).

Mindfulness-bases strategies act on both attentional deployment and cognitive change (see ). They particularly target automatic attention and cognitive flexibility (Leyland et al., Citation2019; Mak et al., Citation2018; Moore & Malinowski, Citation2009). Mindfulness seems to strengthen top-down cognitive control over attentional bias and physiological indices of cue-reactivity (Froeliger et al., Citation2017; Garland et al., Citation2017), also reflected in increased prefrontal activation to ‘regulate’ subcortical brain networks in a goal-directed manner (Froeliger et al., Citation2017; Garland & Howard, Citation2018). In line with our framework, mindfulness training may thus target automatic processes underlying health behaviours by increasing (i.e., automatising) healthy habitual responding and self-control over unhealthy stimulus-response (e.g., conditioned) associations (Brewer, Citation2019; Galla & Duckworth, Citation2015; Hanley & Garland, Citation2019).

Response-focused strategies

Cognitive bias modification (CBM) tasks are considered response-focused intervention strategies that consistently modify (i.e., downregulate) targeted biases and unwanted stimulus-response associations (Jones & Sharpe, Citation2017). They work best for people with higher impulsive addictive approach tendencies (Eberl et al., Citation2013; Weckler et al., Citation2017), in line with the first hypothesis of our conceptual model (i.e., ‘response-focused strategies work better for those who are more impulsive’). CBM tasks have small effects on cognitive bias and relapse rates in alcohol and tobacco use disorders (Boffo et al., Citation2019; Jones & Sharpe, Citation2017), but positive effects on biases do not always translate into effects on addiction outcomes (Boffo et al., Citation2019; Cristea et al., Citation2016). CBM tasks should not be regarded as effective stand-alone interventions for alcohol problems, but have potential in the clinical context as an add-on intervention to treatment for alcohol use disorder (Wiers et al., Citation2018). Go/No-Go tasks are considered one eminent exemplary type of CBM training that has shown particular promise for targeting addictive eating patterns (Aulbach et al., Citation2019).

Go/No-Go tasks

Go/No-Go tasks focus specifically on the inhibition of motor responses to pictures of palatable cues (e.g.,., smoking, alcohol or high-calorie food pictures). Participants are thus trained to withhold their response to attractive cue pictures (e.g., of palatable food). Reviews and meta-analyses have provided evidence that Go/No-Go training can positively influence addictive health behaviours (Allom et al., Citation2016; Aulbach et al., Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2016; Turton et al., Citation2016), and thus particularly eating behaviours (Aulbach et al., Citation2019). Moreover, recent field studies from the field of eating behaviours suggest that insights from laboratory Go/No-Go studies might be translated to clinical settings (Chen et al., Citation2018a; Preuss et al., Citation2017; Turton et al., Citation2018), although higher powered, longitudinal within-subjects studies are still needed (Carbine & Larson, Citation2019; Veling et al., Citation2020).

Go/No-Go training does not seem to strengthen ‘top-down’ self-control, but mainly works through bottom-up changes in stimulus-response associations (Veling et al., Citation2017). Repeatedly not responding to a cue may create bottom-up stop-associations with the trained food items (i.e., stimulus-stop contingencies), with no/go stimuli directly triggering behavioural inhibition as in a ‘learned reflex’. Moreover, the continuous withholding of responses to attractive cues may also produce conflicts and negative affect, that eventually may lead to devaluation of the initial targeted cues. To date, several studies have shown evidence for lower evaluations of trained No-Go compared to Go and/or untrained pictures, interpreted as evidence for devaluation (Chen et al., Citation2016, Citation2018a; Houben et al., Citation2012; Quandt et al., Citation2019; Scholten et al., Citation2019; Veling et al., Citation2013). However, some recent studies found that the effects of Go/No-Go training were smaller for rewarding stimuli and stronger for aversive or neutral stimuli (Chen et al., Citation2019; De Pretto et al., Citation2019), which is in apparent contrast with a cue-devaluation mechanism of rewarding cues. Thus, it is so far unknown which of the specific bottom-up ‘working’ mechanisms (i.e., stimulus-stop contingencies or cue devaluation) are important, but both clearly refer to automatic changes and downregulation in stimulus-response associations, in line with our framework (see ).

Direct antecedent-focused strategies support other intervention strategies

Diverse studies have shown consistent effects of forming implementation intentions on Go/No-Go trainings (Brandstätter et al., Citation2001; Burkard et al., Citation2013; De Pretto et al., Citation2017; Gawrilow & Gollwitzer, Citation2008; Lengfelder & Gollwitzer, Citation2001; Scholz et al., Citation2009). For instance, one study found that children with ADHD who formed an inhibition goal with implementation intentions improved inhibition of an unwanted response on a Go/No-Go training (Gawrilow & Gollwitzer, Citation2008). Similarly, another study found that performance on Go/No-Go trainings could be improved after forming implementation intentions among general adult participants among whom stress was being experimentally manipulated: Stress impaired go no-go performance only in the group not instructed to use implementation intentions (Scholz et al., Citation2009). Moreover, primes of smoking-related backgrounds might also help smokers to be more accurate (i.e., making fewer mistakes) on Go/No-Go trainings (Detandt et al., Citation2017). These findings suggest that direct antecedent-focused strategies (e.g., implementation intentions or priming) may support performance on response-focused intervention strategies (e.g., Go/No-Go trainings), in line with the third hypothesis of our conceptual model.

Moreover, direct antecedent-focused intervention strategies might also facilitate the initiation of indirect antecedent-focused or response-focused intervention strategies. In one illustrative study, self-compassion priming resulted in higher willingness to engage in mindfulness training through increased state mindfulness (Rowe et al., Citation2016). Formation of implementation intentions has also shown to increase attendance for psychotherapy (Sheeran et al., Citation2007) and can help patients achieve their goals (Duhne et al., Citation2020). The need to examine whether and how direct antecedent-focused strategies might engage initial use of response-focused intervention strategies is warranted and forms an important avenue for future research.

General discussion

The choice for deciding between different intervention strategies targeting automatic processes underlying health behaviours is still often arbitrary and has been hampered by the lack of a practical framework categorising such strategies according to how they target automatic processes. We propose a process framework to fulfil this need that distinguishes between three classes of intervention strategies. Although previous frameworks have stimulated improved understanding, development and evaluation of interventions that target automatic processes (Friese et al., Citation2011; Hollands et al., Citation2016; Papies, Citation2017), our model is the first to propose a process model of intervention techniques that specifies differential mechanisms along the unfolding automatic response. Given the focus on intervention strategies targeting automatic processes to change unhealthy behaviours and related intention-behaviour health gaps, our conceptual model may particularly be important for disadvantaged (e.g., lower educated) groups that often experience more problems with translating intentions into behaviours (Schüz et al., Citation2017; Schüz et al., Citation2020).

The model builds upon the process model of emotion regulation (Gross, Citation1998, Citation2001). It distinguishes between the following three types of strategies: (i) direct antecedent-focused interventions that focus on the avoidance of unwanted stimulus-response associations (ii) indirect antecedent-focused interventions that also focus on the avoidance of unwanted stimulus-response associations but do so through automatising self-control, given promising effects of effortless self-control (Gillebaart & de Ridder, Citation2015); and (iii) response-focused interventions that focus directly on changing (i.e., downregulating) automatic associations, attentional biases, and approach–avoidance tendencies. We used four exemplary, principal and seemingly effective, types of intervention strategies (i.e., goal priming, implementation intentions, mindfulness and Go/No-Go tasks) that illustrate these three different types of strategies. Notably, similar type of strategies have been used in the mental health domain. For example, forming implementation intentions (i.e., direct antecedent-focused strategies) may prevent mental health problems by focusing on goals (Toli et al., Citation2016). Mindfulness-based strategies (i.e., indirect antecedent-focused strategies) improve mental health and prevent depressive relapse by automatising self-control (Kuyken et al., Citation2016; Spijkerman et al., Citation2016). Finally, CBM techniques (i.e., response-focused strategies) are used to change perception of stimuli in depression and anxiety disorder (Fodor et al., Citation2020; Loijen et al., Citation2020). Thus, our process framework might also be readily translatable to mental health intervention domains.

Our process model proposes strategies that operate at some point during the unfolding automatic response, and, we present the three classes of intervention strategies (i.e., direct antecedent, indirect antecedent and response-focused) as distinct approaches. However, as mentioned, this does not mean that strategies are limited by their first and main working mechanism within the unfolding automatic response. This might particularly apply to the different forms of antecedent-focused strategies (i.e., direct or indirect) that both aim to prevent the exposure to or activation of automatic unwanted responses. For instance, forming implementation intentions may directly assist in the avoidance of unwanted stimulus-response associations, but may also do so indirectly by automatising self-control (Friese et al., Citation2011; Gillebaart & de Ridder, Citation2015). In the end, when the use of implementation intentions is successful and new habits have been formed, then the old unwanted habits and underlying stimulus-response associations may theoretically even change. Thus, we placed intervention strategies by reference to their key proposed mechanism of effect (i.e., similar to the first mechanism arising during the unfolding automatic response). The conceptual process model () distinguishing between these three broad classes of interventions is thus necessarily an oversimplification, but provides a general framework for deepening our understanding of the automatic mechanisms involved.

Reflection on the three main hypotheses

Our process model resulted in the formulation of three main hypotheses that provide practical guidelines for intervention selection. In line with our first hypothesis (i.e., direct antecedent-focused strategies work better for individuals who are less impulsive, while response-focused strategies work better for those who are more impulsive), direct antecedent-focused strategies (i.e., implementation intentions) were indeed found to be more successful for motivated individuals lower in impulsivity (Churchill & Jessop, Citation2010; Churchill & Jessop, Citation2011; Hagger & Luszczynska, Citation2014), whereas response-focused strategies were more effective for more impulsive and approach-biased individuals (Eberl et al., Citation2013; Weckler et al., Citation2017). Moreover, a recent study among individuals with eating disorders (i.e., bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder) – who are commonly more impulsive than non-eating disordered individuals (Waxman, Citation2009) – evaluated individuals’ feedback and experiences with both implementation intentions and Go/No-Go tasks, finding that ‘implementation intentions’ were less acceptable than Go/No-Go tasks (Chami et al., Citation2020). This accords with the idea that simpler forms of ‘direct antecedent-focused’ strategies are insufficient for individuals with more impulsive, and probably also more addictive and disordered, characteristics. Although more research testing (other) individual moderating characteristics of (additional) techniques is needed, these findings provide some useful suggestions for tailoring different intervention types to individual ‘impulsivity’ traits, impulsivity being a characteristic feature of addiction (Kotov et al., Citation2010). This first hypothesis may thus stimulate further research examining how tailoring of intervention strategies to individual ‘impulsivity’ and ‘impulsivity-related’ characteristics can be optimised.

In line with the second hypothesis of our conceptual model (if direct antecedent-focused strategies are successful, it might not make sense to expose people to response-focused strategies to downregulate further responses as well), findings of three studies are rather unanimous in their conclusion that combining the formation of simple and specific implementation intentions (i.e., direct antecedent-focused strategies) with Go/No-Go tasks (i.e., response-focused strategies) did not lead to additive effects on reduction of self-selected portion size of palatable food or amount of weight loss (Van Koningsbruggen et al., Citation2013; Veling et al., Citation2014). People probably do not need to train changes in the underlying processing of cues they are no longer (i.e., physically or mentally) affected by. It should be noted, however, that studies all refer to one similar exemplary combination of strategies (i.e., implementation intentions and Go/No-Go tasks). Given the scarcity of studies evaluating such combined intervention techniques, these findings should be seen as working hypotheses to further test in future randomised controlled trials.

Finally, we hypothesised that direct antecedent-focused strategies may be used to initiate and maintain performance on other intervention strategies (i.e., the third hypothesis of our conceptual model). In line with this hypothesis, forming implementation intentions consistently supported performance on Go/No-Go tasks (Brandstätter et al., Citation2001; Burkard et al., Citation2013; De Pretto et al., Citation2017; Gawrilow & Gollwitzer, Citation2008; Lengfelder & Gollwitzer, Citation2001; Scholz et al., Citation2009) and similar effects for priming have been reported (Detandt et al., Citation2017). Notably, a promising theory-based view of CBM (i.e., ABC training) involves repeated training of stimulus-response downregulation away from addictive cues towards personalised goal-relevant ‘approach’ behaviours (Wiers et al., Citation2020). We suggest that antecedent-focused strategies might be used to assist the initial choice for and support of goal-relevant ‘approach’ behaviours in ‘response-focused’ CBM trainings. Another promising area of future research is to examine whether direct antecedent-focused strategies also facilitate the initiation of other interventions in real-life contexts. There is some preliminary support for this suggestion (Duhne et al., Citation2020; Rowe et al., Citation2016; Sheeran et al., Citation2007). Future research should further examine whether and how direct antecedent-focused strategies (e.g., implementation intentions or goal priming) may support the initiation of other intervention strategies, particularly in reaction to feelings of craving (e.g., ‘If I experience craving, then I will perform the Go/No-Go task’). We suggest that this is an important future research avenue as it may break the automatic link between the cue (e.g., smelling a cigarette or experiencing craving or stress) and the behaviour (e.g., smoking) through the development of new stimulus-response associations (Larsen, Kremers, & Vink, Citationmanuscript submitted for publication), in addition to further response-focused specific intervention effects.

Further future directions

Notably, in contrast to the absence of interaction effects when combining direct-antecedent and response-focused strategies, interaction effects have been reported when combining other types of techniques. For instance, a systematic review suggests that a combination of ‘priming’ and ‘salience’ nudges (i.e., both direct-antecedent focused strategies) influences healthier choices (Wilson et al., Citation2016). We suggest that future research requires more specific and precise demarcation of the conditions under which techniques might have combined effects. Our categorisation may offer guidance on the most likely mechanisms involved in (combining) different types of techniques, facilitating further thinking on the existence or absence of interaction effects between specific types of techniques.

Moreover, some recent theoretical accounts propose that propositional processes (e.g., ‘appraisals’) play a role in (further) stimulus-response downregulation (De Houwer et al., Citation2020; Van Dessel et al., Citation2018, Citation2019), supported by studies showing that the awareness of stimulus-action contingencies moderates effects of cognitive bias modification (CBM) trainings (i.e., more aware – more effects) (Hofmann et al., Citation2010; Van Dessel et al., Citation2016). As such, interventions that stimulate awareness may thus further increase effects of response-focused strategies. Mindfulness strategies might increase momentary awareness and engender less effortful response inhibition (Andreu et al., Citation2018). There appears to be some preliminary synergistic support from studies combining mindfulness and response-focused strategies (Fisher et al., Citation2016; Forman et al., Citation2016) and there is more research underway testing similar combined effects (Chen et al., Citation2018b). Future research may further examine these theoretically promising additive effects between response-focused and indirect-antecedent focused strategies.

Conclusion

We propose a new process framework for categorising intervention techniques targeting wholly automatic processes that may help clinicians and researchers decide which types of intervention strategies are most promising given individual’s characteristics. For researchers specifically, when no former information is given about individual characteristics (e.g., impulsivity), one may start with direct antecedent-focused strategies for all participants and randomise participants to further strategies based on the effectiveness of former outcomes (i.e., sequential intervention allocation), given that direct-focused strategies are often less resource intensive compared to the other types of strategies. Notably, interventions that combine strategies targeting more reflective (e.g., attitudes or self-efficacy) and automatic processes show promise for changing health behaviours (Friese et al., Citation2011). Nevertheless, given the abundant amount of socio-cognitive models, our conceptual model focuses on automatic processes and offers a way to help researchers decide about when less is enough (i.e., when direct antecedent-focused strategies are effective) and more is not more effective here (i.e., counter the tendency to throw the kitchen sink into every intervention). The purpose of this piece is to contribute to a solid, theoretically-grounded foundation for generating further understanding for how (combined) intervention techniques might most effectively target automatic processes to improve health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Esther Papies, Paschal Sheeran and Denise de Ridder for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Although automaticity is an umbrella term encompassing many different facets and conceptualisations, it can function usefully if researchers specify in what sense they believe a process to be automatic (Moors & De Houwer, Citation2006).

References

- Aarts, H., Dijksterhuis, A., & Midden, C. (1999). To plan or not to plan? Goal achievement or interrupting the performance of mundane behaviors. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(8), 971–979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199912)29:8

- Adriaanse, M. A., Gollwitzer, P. M., De Ridder, D. T., De Wit, J. B., & Kroese, F. M. (2011). Breaking habits with implementation intentions: A test of underlying processes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(4), 502–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211399102

- Adriaanse, M. A., van Oosten, J. M., de Ridder, D. T., de Wit, J. B., & Evers, C. (2011). Planning what not to eat: Ironic effects of implementation intentions negating unhealthy habits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210390523

- Adriaanse, M. A., & Verhoeven, A. (2018). Breaking habits using implementation intentions. In The psychology of habit (pp. 169–188). Springer.

- Adriaanse, M. A., Vinkers, C. D., De Ridder, D. T., Hox, J. J., & De Wit, J. B. (2011). Do implementation intentions help to eat a healthy diet? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Appetite, 56(1), 183–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.10.012

- Allom, V., Mullan, B., & Hagger, M. (2016). Does inhibitory control training improve health behaviour? A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 10(2), 168–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1051078

- Alsubaie, M., Abbott, R., Dunn, B., Dickens, C., Keil, T. F., Henley, W., & Kuyken, W. J. C. P. R. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 74–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.008

- Andreu, C. I., Cosmelli, D., Slagter, H. A., Franken, I. H., & Verdejo-García, A. (2018). Effects of a brief mindfulness-meditation intervention on neural measures of response inhibition in cigarette smokers. Plos One, 13(1), e0191661. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191661

- Aulbach, M. B., Knittle, K., & Haukkala, A. (2019). Implicit process interventions in eating behaviour: A meta-analysis examining mediators and moderators. Health Psychology Review, 13(2), 179–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1571933

- Boffo, M., Zerhouni, O., Gronau, Q. F., van Beek, R. J., Nikolaou, K., Marsman, M., & Wiers, R. W. (2019). Cognitive bias modification for behavior change in alcohol and smoking addiction: Bayesian meta-analysis of individual participant data. Neuropsychology Review, 29(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-018-9386-4

- Brandstätter, V., Lengfelder, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2001). Implementation intentions and efficient action initiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(5), 946–960. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.946

- Brewer, J. (2019). Mindfulness training for addictions: Has neuroscience revealed a brain hack by which awareness subverts the addictive process? Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 198–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.01.014

- Buckland, N. J., Er, V., Redpath, I., & Beaulieu, K. J. (2018). Priming food intake with weight control cues: Systematic review with a meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15(1), 66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0698-9

- Burkard, C., Rochat, L., & Van der Linden, M. (2013). Enhancing inhibition: How impulsivity and emotional activation interact with different implementation intentions. Acta Psychologica, 144(2), 291–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2013.07.008

- Carbine, K. A., & Larson, M. J. (2019). Quantifying the presence of evidential value and selective reporting in food-related inhibitory control training: Ap-curve analysis. Health Psychology Review, 1–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1622144

- Carrero, I., Vilà, I., & Redondo, R. (2019). What makes implementation intention interventions effective for promoting healthy eating behaviours? A meta-regression. Appetite, 1, 140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.05.024

- Chami, R., Cardi, V., Lawrence, N., MacDonald, P., Rowlands, K., Hodsoll, J., & Treasure, J. (2020). Targeting binge eating in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder using inhibitory control training and implementation intentions: A feasibility trial. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291720002494

- Chen, Z., Holland, R. W., Quandt, J., Dijksterhuis, A., & Veling, H. (2019). When mere action versus inaction leads to robust preference change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000158

- Chen, Z., Veling, H., de Vries, S. P., Bijvank, B. O., Janssen, I. M. C., Dijksterhuis, A., & Holland, R. W. (2018a). Go/no-go training changes food evaluation in both morbidly obese and normal-weight individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(12), 980–990. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000320

- Chen, Z., Veling, H., Dijksterhuis, A., & Holland, R. W. (2016). How does not responding to appetitive stimuli cause devaluation: Evaluative conditioning or response inhibition? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 145(12), 1687–1701. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000236

- Chen, X. J., Wang, D. M., Zhou, L. D., Winkler, M., Pauli, P., Sui, N., & Li, Y. H. (2018b). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention combined with virtual reality cue exposure for methamphetamine use disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 70, 99–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2018.04.006

- Chin, B., Lindsay, E. K., Greco, C. M., Brown, K. W., Smyth, J. M., Wright, A. G., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Psychological mechanisms driving stress resilience in mindfulness training: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology, 38(8), 759.

- Churchill, S., & Jessop, D. (2010). Spontaneous implementation intentions and impulsivity: Can impulsivity moderate the effectiveness of planning strategies? British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(3), 529–541. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910709X475423

- Churchill, S., & Jessop, D. C. (2011). Too impulsive for implementation intentions? Evidence that impulsivity moderates the effectiveness of an implementation intention intervention. Psychology and Health, 26(5), 517–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870441003611536

- Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68(1), 491–516. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139

- Creswell, J. D., Lindsay, E. K., Villalba, D. K., & Chin, B. (2019). Mindfulness training and physical health: Mechanisms and outcomes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(3), 224–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000675

- Cristea, I. A., Kok, R. N., & Cuijpers, P., & van den Bos, R. (2016). The effectiveness of cognitive bias modification interventions for substance addictions: A meta-analysis. Plos One, 11(9), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone

- De Houwer, J., Van Dessel, P., & Moran, T. (2020). Attitudes beyond associations: On the role of propositional representations in stimulus evaluation. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 61, pp. 127–183). Academic Press.

- De Pretto, M., Hartmann, L., Garcia-Burgos, D., Sallard, E., & Spierer, L. (2019). Stimulus reward value interacts with training-induced plasticity in inhibitory control. Neuroscience, 421, 82–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.10.010

- De Pretto, M., Rochat, L., & Spierer, L. (2017). Spatiotemporal brain dynamics supporting the immediate automatization of inhibitory control by implementation intentions. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10832-x

- Detandt, S., Bazan, A., Schröder, E., Olyff, G., Kajosch, H., Verbanck, P., & Campanella, S. (2017). A smoking-related background helps moderate smokers to focus: An event-related potential study using a Go-NoGo task. Clinical Neurophysiology, 128(10), 1872–1885. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2017.07.416

- Duhne, P. G. S., Horan, A. J., Ross, C., Webb, T. L., & Hardy, G. E. (2020). Assessing and promoting the use of implementation intentions in clinical practice. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113490

- Eberl, C., Wiers, R. W., Pawelczack, S., Rinck, M., Becker, E. S., & Lindenmeyer, J. (2013). Approach bias modification in alcohol dependence: Do clinical effects replicate and for whom does it work best? Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 4, 38–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2012.11.002

- Fisher, N., Lattimore, P., & Malinowski, P. J. A. (2016). Attention with a mindful attitude attenuates subjective appetitive reactions and food intake following food-cue exposure. Appetite, 99, 10–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.12.009

- Fodor, L. A., Georgescu, R., Cuijpers, P., Szamoskozi, Ş, David, D., Furukawa, T. A., & Cristea, I. A. (2020). Efficacy of cognitive bias modification interventions in anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(6), 506–514. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30130-9

- Forcano, L., Mata, F., de la Torre, R., & Verdejo-Garcia, A. (2018). Cognitive and neuromodulation strategies for unhealthy eating and obesity: Systematic review and discussion of neurocognitive mechanisms. Journal of Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 87, 161–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.003

- Forman, E. M., Shaw, J. A., Goldstein, S. P., Butryn, M. L., Martin, L. M., Meiran, N., Crosby, R. D., & Manasse, S. M. (2016). Mindful decision making and inhibitory control training as complementary means to decrease snack consumption. Appetite, 103, 176–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.04.014

- Friese, M., Hofmann, W., & Wiers, R. W. (2011). On taming horses and strengthening riders: Recent developments in research on interventions to improve self-control in health behaviors. Self and Identity, 10(3), 336–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2010.536417

- Froeliger, B., Mathew, A. R., McConnell, P. A., Eichberg, C., Saladin, M. E., Carpenter, M. J., & Garland, E. L. (2017). Restructuring reward mechanisms in nicotine addiction: A pilot fMRI study of mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for cigarette smokers. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2017, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/7018014

- Galla, B. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 508–525. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000026

- Garland, E. L., Baker, A. K., & Howard, M. O. (2017). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement reduces opioid attentional bias among prescription opioid-treated chronic pain patients. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 8(4), 493–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/694324

- Garland, E. L., & Howard, M. O. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatment of addiction: Current state of the field and envisioning the next wave of research. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 13(1), 14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0115-3

- Gawrilow, C., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2008). Implementation intentions facilitate response inhibition in children with ADHD. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(2), 261–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-007-9150-1

- Gillebaart, M., & de Ridder, D. T. (2015). Effortless self-control: A novel perspective on response conflict strategies in trait self-control. Social & Personality Psychology Compass, 9(2), 88–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12160

- Gjødsbøl, I. M., Winkel, B. G., & Bundgaard, H. (2019). Personalized medicine and preventive health care: Juxtaposing health policy and clinical practice. Critical Public Health, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2019.1685077

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans.. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493–503. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.493

- Gollwitzer, P. M., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta-analysis of effects and processes. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 69–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38002-1

- Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

- Gross, J. J. (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 214–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00152

- Hagger, M. S., & Luszczynska, A. (2014). Implementation intention and action planning interventions in health contexts: State of the research and proposals for the way forward. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 6(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12017

- Hanley, A. W., & Garland, E. L. (2019). Mindfulness training disrupts Pavlovian conditioning. Physiology & Behavior, 204, 151–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.02.028

- Herman, C. P., & Polivy, J. (2008). External cues in the control of food intake in humans: The sensory-normative distinction. Physiology & Behavior, 94(5), 722–728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.04.014

- Hofmann, W., De Houwer, J., Perugini, M., Baeyens, F., & Crombez, G. (2010). Evaluative conditioning in humans: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 390–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018916

- Hollands, G. J., Bignardi, G., Johnston, M., Kelly, M. P., Ogilvie, D., Petticrew, M., Prestwich, A., Shemilt, I., Sutton, S., & Marteau, T. M. (2017). The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(8), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0140

- Hollands, G. J., Marteau, T. M., & Fletcher, P. C. (2016). Non-conscious processes in changing health-related behaviour: A conceptual analysis and framework. Health Psychology Review, 10(4), 381–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2015.1138093

- Houben, K., Havermans, R. C., Nederkoorn, C., & Jansen, A. (2012). Beer à No-Go: Learning to stop responding to alcohol cues reduces alcohol intake via reduced affective associations rather than increased response inhibition. Addiction, 107(7), 1280–1287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03827

- Howarth, A., Smith, J. G., Perkins-Porras, L., & Ussher, M. (2019). Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.02.007

- Jones, A., Di Lemma, L. C., Robinson, E., Christiansen, P., Nolan, S., Tudur-Smith, C., & Field, M. (2016). Inhibitory control training for appetitive behaviour change: A meta-analytic investigation of mechanisms of action and moderators of effectiveness. Appetite, 97, 16–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2015.11.013

- Jones, E. B., & Sharpe, L. (2017). Cognitive bias modification: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 223, 175–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.034

- Kang, Y., Gruber, J., & Gray, J. R. (2013). Mindfulness and de-automatization. Emotion Review, 5(2), 192–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912451629

- Keesman, M., Aarts, H., Häfner, M., & Papies, E. K. (2017). Mindfulness reduces reactivity to food cues: Underlying mechanisms and applications in daily life. Current Addiction Reports, 4(2), 151–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0134-2

- Khoury, M. J., Iademarco, M. F., & Riley, W. T. (2016). Precision public health for the era of precision medicine. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(3), 398–401. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.031

- Kotov, R., Gamez, W., Schmidt, F., & Watson, D. (2010). Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 768–821. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020327

- Kuyken, W., Warren, F. C., Taylor, R. S., Whalley, B., Crane, C., Bondolfi, G., Hayes, R., Huijbers, M., Ma, H., Schweizer, S., Segal, Z., Speckens, A., Teasdale, J. D., Van Heeringen, K., Williams, M., Byford, S., Byng, R., & Dalgleish, T. (2016). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse: An individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(6), 565–574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076

- Larsen, J. K., Kremers, S. P. J., & Vink, J. M. (manuscript submitted for publication). Be clean, be active: Why acute exercise may benefit substance use treatment.

- Lengfelder, A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (2001). Reflective and reflexive action control in patients with frontal brain lesions. Neuropsychology, 15(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.15.1.80

- Leyland, A., Rowse, G., & Emerson, L.-M. (2019). Experimental effects of mindfulness inductions on self-regulation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Emotion, 19(1), 108–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000425

- Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2019). Mindfulness, acceptance, and emotion regulation: Perspectives from Monitor and Acceptance Theory (MAT). Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 120–125.

- Lindsay, E. K., Young, S., Smyth, J. M., Brown, K. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Acceptance lowers stress reactivity: Dismantling mindfulness training in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 87, 63–73.

- Loijen, A., Vrijsen, J. N., Egger, J. I., Becker, E. S., & Rinck, M. (2020). Biased approach-avoidance tendencies in psychopathology: A systematic review of their assessment and modification. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101825. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101825

- Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2015). Mindfulness meditation reduces implicit age and race bias: The role of reduced automaticity of responding. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 284–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614559651

- Mak, C., Whittingham, K., Cunnington, R., & Boyd, R. N. (2018). Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for attention and executive function in children and adolescents—A systematic review. Mindfulness, 9(1), 59–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0770-6

- Marteau, T. M., Hollands, G. J., & Fletcher, P. C. (2012). Changing human behavior to prevent disease: The importance of targeting automatic processes. Science, 337(6101), 1492–1495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1226918

- McGill, R., Anwar, E., Orton, L., Bromley, H., Lloyd-Williams, F., O'Flaherty, M., Taylor-Robinson, D., Guzman-Castillo, M., Gillespie, D., Moreira, D., Allen, K., Hyseni, L., Calder, N., Petticrew, M., White, M., Whitehead, M., & Capewell, S. (2015). Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact (vol 15, 457, 2015). BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1781-7

- Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., Eccles, M. P., Cane, J., & Wood, C. E. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- Moore, A., & Malinowski, P. (2009). Meditation, mindfulness and cognitive flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition, 18(1), 176–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2008.12.008

- Moors, A., & De Houwer, J. (2006). Automaticity: A theoretical and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 297–326. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.297

- Papies, E. K. (2017). Situating interventions to bridge the intention-behaviour gap: A framework for recruiting nonconscious processes for behaviour change. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(7), e12323. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12323

- Papies, E. K., & Hamstra, P. (2010). Goal priming and eating behavior: Enhancing self-regulation by environmental cues. Health Psychology, 29(4), 384–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019877

- Papies, E. K., van Winckel, M., & Keesman, M. (2016). Food-specific decentering experiences are associated with reduced food cravings in meditators: A preliminary investigation. Mindfulness, 7(5), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0554-4

- Prestwich, A., Kellar, I., Parker, R., MacRae, S., Learmonth, M., Sykes, B., Taylor, N., & Castle, H. (2014). How can self-efficacy be increased? Meta-analysis of dietary interventions. Health Psychology Review, 8(3), 270–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2013.813729

- Preuss, H., Pinnow, M., Schnicker, K., & Legenbauer, T. (2017). Improving inhibitory control abilities (ImpulsE)—A promising approach to treat impulsive eating? European Eating Disorders Review, 25(6), 533–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2544

- Quandt, J., Holland, R. W., Chen, Z., & Veling, H. (2019). The role of attention in explaining the no-go devaluation effect: Effects on appetitive food items. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xhp0000659

- Rowe, A. C., Shepstone, L., Carnelley, K. B., Cavanagh, K., & Millings, A. (2016). Attachment security and self-compassion priming increase the likelihood that first-time engagers in mindfulness meditation will continue with mindfulness training. Mindfulness, 7(3), 642–650. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0499-7

- Scholten, H., Granic, I., Chen, Z., Veling, H., & Luijten, M. (2019). Do smokers devaluate smoking cues after go/no-go training? Psychology & Health, 34(5), 609–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2018.1554184

- Scholz, U., La Marca, R., Nater, U. M., Aberle, I., Ehlert, U., Hornung, R., Martin, M., & Kliegel, M. (2009). Go no-go performance under psychosocial stress: Beneficial effects of implementation intentions. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 91(1), 89–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nlm.2008.09.002

- Schüz, B., Brick, C., Wilding, S., & Conner, M. (2020). Socioeconomic status moderates the effects of health cognitions on health behaviors within participants: Two multibehavior studies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 54(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/abm/kaz023

- Schüz, B., Li, A. S.-W., Hardinge, A., McEachan, R. R., & Conner, M. (2017). Socioeconomic status as a moderator between social cognitions and physical activity: Systematic review and meta-analysis based on the theory of planned Behavior. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 30, 186–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.03.004

- Sheeran, P., Aubrey, R., & Kellett, S. (2007). Increasing attendance for psychotherapy: Implementation intentions and the self-regulation of attendance-related negative affect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 853–863. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.853

- Spijkerman, M., Pots, W. T. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 102–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009

- Stämpfli, A. E., & Brunner, T. A. (2016). The art of dieting: Exposure to thin sculptures effortlessly reduces the intake of unhealthy food in motivated eaters. Food Quality and Preference, 50, 88–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.01.012

- Stämpfli, A. E., Stöckli, S., & Brunner, T. A. (2017). A nudge in a healthier direction: How environmental cues help restrained eaters pursue their weight-control goal. Appetite, 110, 94–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.037

- Tapper, K. (2017). Can mindfulness influence weight management related eating behaviors? If so, how?. Clinical psychology review, 53, 122–134.

- Tapper, K. (2018). Mindfulness and craving: Effects and mechanisms. Clinical psychology review, 59, 101–117.

- Tapper, K., & Turner, A. (2018). The effect of a mindfulness-based decentering strategy on chocolate craving. Appetite, 130, 157–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.08.011

- Tarkkala, H., Helén, I., & Snell, K. (2019). From health to wealth: The future of personalized medicine in the making. Futures, 109, 142–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.06.004

- Toli, A., Webb, T. L., & Hardy, G. E. (2016). Does forming implementation intentions help people with mental health problems to achieve goals? A meta-analysis of experimental studies with clinical and analogue samples. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12086

- Turton, R., Bruidegom, K., Cardi, V., Hirsch, C. R., & Treasure, J. (2016). Novel methods to help develop healthier eating habits for eating and weight disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 61, 132–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.12.008

- Turton, R., Nazar, B. P., Burgess, E. E., Lawrence, N. S., Cardi, V., Treasure, J., & Hirsch, C. R. (2018). To go or not to go: A proof of concept study testing food-specific inhibition training for women with eating and weight disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 26(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2566

- Van der Laan, L. N., Papies, E. K., Hooge, I. T. C., & Smeets, P. A. M. (2017). Goal-directed visual attention drives health goal priming: An eye-tracking experiment. Health Psychology, 36(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000410

- Van Dessel, P., De Houwer, J., & Gast, A. (2016). Approach–avoidance training effects are moderated by awareness of stimulus–action contingencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 81–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215615335

- Van Dessel, P., Hughes, S., & De Houwer, J. (2018). Consequence-based approach-avoidance training: A new and improved method for changing behavior. Psychological Science, 29(12), 1899–1910. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618796478

- Van Dessel, P., Hughes, S., & De Houwer, J. (2019). How do actions influence attitudes? An inferential account of the impact of action performance on stimulus evaluation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(3), 267–284. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318795730

- Van Koningsbruggen, G., Veling, H., Stroebe, W., & Aarts, H. (2013). Comparing two psychological interventions in reducing impulsive processes of eating behavior: Effects on self-selected portion size. British Journal of Health Psychology, 19, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12075

- Veling, H., Aarts, H., & Stroebe, W. (2013). Stop signals decrease choices for palatable foods through decreased food evaluation. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 875. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00875

- Veling, H., Chen, Z., Liu, H., Quandt, J., & Holland, R. W. (2020). Updating the p-curve analysis of carbine and Larson with results from preregistered experiments. Health Psychology Review, 14(2), 215–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1669482

- Veling, H., Lawrence, N. S., Chen, Z., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Holland, R. W. (2017). What is trained during food go/no-go training? A review focusing on mechanisms and a research agenda. Current Addiction Reports, 4(1), 35–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0131-5

- Veling, H., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Aarts, H., & Stroebe, W. (2014). Targeting impulsive processes of eating behavior via the internet. Effects on body weight. Appetite, 78, 102–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.014

- Vila, I., Carrero, I., & Redondo, R. (2017). Reducing fat intake using implementation intentions: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(2), 281–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12230

- Waxman, S. E. (2009). A systematic review of impulsivity in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(6), 408–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.952

- Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2007). How do implementation intentions promote goal attainment? A test of component processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(2), 295–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.02.001

- Weckler, H., Kong, G., Larsen, H., Cousijn, J., Wiers, R. W., & Krishnan-Sarin, S. (2017). Impulsivity and approach tendencies towards cigarette stimuli: Implications for cigarette smoking and cessation behaviors among youth. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(5), 363–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000139

- Weingarten, E., Chen, Q. J., McAdams, M., Yi, J., Hepler, J., & Albarracin, D. (2016). From primed concepts to action: A meta-analysis of the behavioral effects of incidentally presented words. Psychological Bulletin, 142(5), 472–497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000030

- Wiers, R. W., Boffo, M., & Field, M. (2018). What’s in a trial? On the importance of distinguishing between experimental lab studies and randomized controlled trials: The case of cognitive bias modification and alcohol use disorders. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 79(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2018.79.333

- Wiers, R. W., Van Dessel, P., & Köpetz, C. (2020). ABC training: A new theory-based form of cognitive-bias modification to Foster automatization of alternative choices in the treatment of addiction and related disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(5), 499–505. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420949500

- Wilson, A. L., Buckley, E., Buckley, J. D., & Bogomolova, S. (2016). Nudging healthier food and beverage choices through salience and priming. Evidence from a systematic review. Food Quality and Preference, 51, 47–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.02.009