ABSTRACT

This paper describes how critical realism was operationalized to provide an explanatory framework for a small-scale qualitative study in the field of teacher education in a sub-Saharan African context. Critical realism combines a realist ontology (there is something to find out about) with a relativistic epistemology (different people will come to know different things in different ways). An attraction of this approach is that it seeks to explain observed phenomena through processes of inference, thus providing the opportunity to make changes for the better in the situation under investigation. The stratified view of reality provided a framework for the analysis of data, which led to the identification of two underlying causal mechanisms and new understandings of teacher education in sub-Saharan Africa. The approach is not without challenges, including the potentially intrusive nature of the enquiry and the positioning of the researchers. Despite these challenges, the evidence from this study is that the approach has the potential to provide new insights which have informed on-going international development projects in teacher education in sub-Saharan Africa.

Introduction

This paper explains how critical realism was operationalized in a small-scale study in the field of teacher education. Critical Realism (CR) provides a way of thinking about the world which draws on social theory to seek explanations for social phenomena, alongside analytical tools to support data collection and data analysis. It is gaining support as a paradigm to support research in education (Cochran-Smith Citation2009, Scott Citation2010, Tao Citation2013, Tikly Citation2015), but as Scott (Citation2010) explains: ‘though the philosophy of critical realism is well developed, its application to the collection and analysis of data at an empirical level is manifestly under-developed’ (p. 9).

CR combines a realist ontology (there is something real to find out about) with a relativistic epistemology (different people will come to know different things in different ways). The appeal of CR was that it goes beyond rich descriptions in order to seek explanations and recognizes that, in the complexity of everyday life, those explanations may draw on different social theories (Tikly Citation2015). Much of the writing about CR gives the impression of a complex set of philosophical ideas, once described to me as an ‘unnecessary edifice’ (Ison, personal communication, May 2018). However, it has been used in sociology, management studies, studies in information, communication and technology, health, entrepreneurship research and education (e.g. Scott Citation2010, Priestley Citation2011b, Wynn and Williams Citation2012, Davis Citation2013, Tao Citation2013, Marks and O’Mahoney Citation2014, Bygstad et al. Citation2016, Fletcher Citation2017, Hodgkinson-Williams et al. Citation2017, Hu Citation2018) to investigate a variety of phenomena. Despite this, the confession to colleagues that I adopted a critical realist framework for my doctoral studies is often greeted by a rolling of the eyes and dis-belief.

Published accounts of critical realism tend to be rich in philosophical explanation but fail to translate this into a practical methodology for gathering empirical data. This is perhaps why colleagues were unimpressed by my choice of paradigm. This paper seeks to demonstrate how the ideas underlying critical realism can be operationalized and used productively in empirical situations. The contribution therefore is to provide a methodological framework rooted in critical realist thought which nevertheless provides a practical approach to gathering and interpreting data to generate rich causal explanations for observed social phenomena.

The doctoral study was about the professional identity of a group of teacher educators in a Kenyan university, and the prospects of this professional group as ‘agents of change’. This is highly relevant in the current time because educational outcomes in Kenya remain low and the quality of teaching is poor (Bold et al. Citation2017). Teacher education is highly theoretical and not considered to be ‘fit-for-purpose’ (Dembele and Miaro-II Citation2013, Moon and Umar Citation2013). Furthermore, it has been suggested that ‘Within the teacher educator community there is, as we have observed, a resistance to change’ (Moon and Umar Citation2013, p. 234) despite the fact that the nature of their work provides the opportunity to lead reform (Cochran-Smith Citation2006, Cochran-Smith et al. Citation2018). The purpose of this study was to investigate why this is the case and was conducted in the context of an international development programme designed to support teacher education (Teacher Education in sub-Saharan Africa, (www.tessafrica.net)).

This paper explains the main tenets of critical realism, the analytical framework that was developed and highlights the challenges and opportunities that this way of thinking about the world can bring to a small-scale study. A particular issue in CR is how we choose to define ‘social structures’. In the context of this study, Scott’s typology (Scott Citation2010) proved to be helpful and the reasons for this are explained. The details of the study are reported elsewhere (Stutchbury Citation2019) although enough detail is included here for the explanation of the methodology to make sense to the reader.

An introduction to critical realism

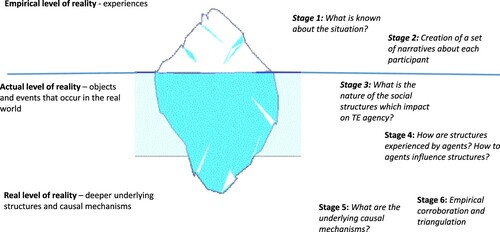

Critical realism (CR) is about looking for explanations (causal mechanisms) through a focus on what people can achieve (agency) in the social context in which they are operating (structures). It sees reality as being like an iceberg: most of reality (the iceberg) is invisible to the observer. The casual mechanisms exist below the surface and are invisible but give rise to ‘experiences’ and ‘events’. They are identified through a process of inference, based on the analysis of data collected within the context under investigation. CR assumes judgemental rationality which allows researchers to ‘evaluate and compare the explanatory power of different theoretical explanations and, finally, to select theories which most accurately represent the “domain of real” given our existing knowledge’ (Hu Citation2018, p. 130). The ‘critical’ in critical realism highlights the fact that researchers are required to be critical of the theories that they use and the explanations that they propose. The aim of CR research is to improve the world (Price and Martin Citation2018) so in that respect the term ‘critical’ also has the same emancipatory implications as critical theory. The motivation for this project was to achieve better understandings about how to improve the quality of teacher education by understanding the origins of the disconnections between what is espoused and what happens in practice, rather than impact directly on the lives of individuals, or to subvert the status quo. Critical realism focuses on structure and agency, whereas critical theorists focus on the underlying ideology in order to achieve change.

In CR, the ontological acceptance of the existence of a stratified depth reality (Fletcher Citation2017) provides a framework for analysing data. The tenet is that observable events arise as a result of activities within social structures – structures that are constantly changing as a result of those activities. These activities are going on beneath the surface and are not immediately observable but can be accessed through research. Critical realists think in terms of three relatively autonomous levels of depth reality: the empirical level (the experiences and sensed perceptions of knowing subjects), the actual level (objects and events that occur in the real world) and the ‘real’ level (deeper-lying structures and causal mechanisms) (Scott Citation2005, Tikly Citation2015, Fletcher Citation2017). The empirical level can be seen and/or measured (the visible part of the iceberg); the actual level can be investigated relatively easily through qualitative research methods (just below the surface); and the real level (the bottom of the iceberg) has to be inferred through a process of abduction (theoretical re-description) and retroduction (a focus on causal mechanisms). In this study, contradictions arose in the ‘actual’ level of reality which describe why change is difficult. Retroduction involves testing proposed explanations for the contradictions against the evidence in order to identify the underlying causal mechanisms and address the underlying social realities which are often presented as ‘barriers’ (or excuses) to change (Checkland et al. Citation2007). The purpose of critical realist research is to determine which causal mechanisms have been triggered in this situation, and what effect they are having. An attraction in the context of international development is that it also provides a way of thinking about what causal mechanisms have not been actualized and could be if things were different.

CR assumes the existence of independent structures (or social forms) that constrain and enable actors to pursue certain actions in a particular setting (agency) (Tao Citation2016) and research in this paradigm involves understanding the relationship between structure and agency (Bhaskar Citation1998, Archer Citation1998b, Scott Citation2010). In the context of this study, the relevant structures were those which impact on the ability of teacher educators (agents) to bring about pedagogic change and finding a way of conceptualizing what is meant by a social structure was a significant issue.

Structure and agency

In his development of CR, Bhaskar (Citation1994) explained the relationship between structure and agency as follows (emphasis in the original):

… all social life is embodied in a network of human relations. This may be demonstrated by the mental experiment of subtracting from society the human agency required for it to be an ongoing affair. What we are left with are dual points of articulation of structure and agency, which are differentiated and processually changing positioned practices human agents occupied, engaged, reproduced or transformed, defining the (changing) system of social relations in which human praxis is embedded. Here again, on the relational model we have a figure of a duality-with-a hiatus, preventing reductionist collapse in either direction. (p. 93)

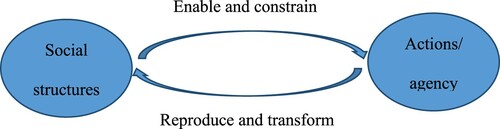

Bhaskar was a philosopher, but his ideas have been adopted and interpreted by sociologists so that they can be used to explain social phenomena. Archer (Citation1995) argues for ‘analytical dualism’ and makes two propositions: that ‘structure necessarily predates the actions which transform it’ and that ‘structural elaborations necessarily post-date those actions’ (Citation1998a, p. 202). She defines a ‘morphogenetic approach’, by which she means we can investigate how the shape of society emerges (morphs) from agents and the intended and unintended consequences of their actions. In practical terms, studying what people do and why they do it will reveal social structures, and in turn, understanding the social structures will explain why they can and cannot do certain things. CR thus seeks separate accounts of structure and praxis, but recognizes that it is the interplay between them that leads to greater understandings (Archer Citation1998a). See .

Critical realists assume that social structures exist independently of actions, but that these structures enable and constrain actions, which in turn reproduce and transform social structures.

A key concept in CR in the context of this study was that of ‘emergence’ (Tikly Citation2015). Interactions between agents, between structures and between agents and structures can give rise to new phenomena. This project saw ‘professional identity’ as emergent as the teacher educators (agents) took action within the prevailing social structures. Understanding their professional identity and how it had formed was therefore key to understanding the challenges behind implementing pedagogic change. Professional identity is a key concept in teacher education so this provided a link with the literature in the field.

Critical realism recognizes that knowledge that we do have of the social structures will be subjective, relative and constructed by individuals; that is, a reality exists that is independent of our knowledge of it (Tikly Citation2015) and the nature of the reality cannot be unproblematically understood, characterized or measured (Wynn and Williams Citation2012). For anyone who has worked in an organization or an institution, this makes sense. There will be things that we can know about (referred to as the transitive domain) and things that we can’t know about, but through research can seek to find out and explain (referred to as the intransitive domain). The aim of this research within a critical realist paradigm was to seek explanations for observed experiences and phenomena in the social world (the uptake or not of a set of ideas or teaching practices), by exploring the relationship between structure and agency and making inferences within the intransitive domain. The research draws on data and social theory to identify the underlying causal mechanisms that give rise to observed events but required the researcher to be critical of the theories they were using.

This study revealed a four significant contradictions in the teacher education provided by this university (actual level of reality), similar to those documented elsewhere (e.g. Cochran-Smith Citation2003, O’Sullivan Citation2010, Katitia Citation2015). Critical realism provided a robust framework and analytical tools to explain the contradictions. Theories about teacher learning, pedagogy and managing change were drawn on to identify, through a process of inference, underlying causal mechanisms which give rise to the contradictions. The contradictions are threatening the successful implementation of new curricula and by understanding how the contradictions arise, there is more prospect of them being challenged.

In summary, critical realists seek explanations for observed phenomena by focusing on the relationship between structure and agency. The next section explains how the agency is being conceptualized and defines what is meant by social structures.

Agency

The focus of this project was the challenge of implementing pedagogic change. An interpretivist study drawing on socio-cultural theories of learning was the initial choice, and such studies are popular in the field. In these studies, the agency is seen as something which is ‘achieved’ (e.g. Priestley et al. Citation2015) as teachers work together to ‘own’ new initiatives. In the situation in which this study took place, the participants were not particularly interested in pedagogic change – despite policy aspirations and new school curricula – and rationalized this by siting ‘barriers’ such as large classes and a lack of resources that were outside their control. This did not mean, however, that they were not agentive in many ways. The critical realist view of agency – that agency is something that human actors possess – was more helpful in this context, but was not unproblematic.

Bhaskar (Citation1994) suggests that agency concerns the capacity of humans to transform situations and themselves through reflexivity. He suggests that human beings are characterized by a ‘capacity for intentional agency and for reflexive awareness and organisation of such agency and by a thoroughly social existence’ (Bhaskar Citation1998, p. 411). Archer (Citation1995) interprets Bhasker’s philosophical ideas from a sociological perspective and proposes a theory of human agency which places powerful people, capable of bringing about transformation, at its heart. She defines ‘agency’ by reflexivity – capabilities that are developed as a consequence of reflexive deliberations on social situations – and argues that choices about how to behave are the result of reflexive deliberations on social situations. She suggests that not everyone will be in a position to become agents or actors who can develop the sort of agential powers necessary to affect transformation. This was problematic in this study, as reflection and reflexivity are not part of the culture in this institution, yet people are often highly agentive in pursuing their agendas.

The view taken in this research is that we often perform actions that are intentional and meaningful, without necessarily being aware of the decision-making process; we may act without intensive prior deliberation (Elder-Vass Citation2007). Although being human might mean that we have the capacity to be reflective and reflexive, it is not a necessary condition for acting purposefully. We can act effectively, yet instinctively, drawing on past experiences and tacit expertise in a subconscious manner. This is consistent with other scholars who have studied social processes (Vickers Citation1968, Checkland and Casar Citation1986, Checkland and Poulter Citation2006) in which the capacity to take purposeful action is seen as being fundamental to being human (rather than reflexivity), and ‘choices’ are seen to be the result of noticing, discriminating and judging – a process that might be instinctive and instantaneous, or the result of deliberation over an extended period of time (Checkland and Casar Citation1986). It is argued, therefore that ‘agency’ (choosing to act purposefully) does not necessarily have to be the result of measured prior deliberation (reflexivity), although of course it can be.

Bhaskar (Citation1994, Citation1998) links human agency to a ‘thoroughly social existence’. This is consistent with alternative views of agency which focus on interaction, discourse and participation, rather than on individual reflexivity (Lave and Wenger Citation1991, Lipponen and Kumpulainen Citation2011). In this project, therefore, the agency is seen in broader terms than Archer and something which is not confined to powerful, reflexive people. It is seen as ‘the capacity to initiate purposeful action that implies will, autonomy, freedom and choice’ (Lipponen and Kumpulainen Citation2011, p. 812). Purposeful action may be the result of reflexive deliberation, but it can also be instinctive, based on judgements which draw on past experiences and personal standards (Vickers Citation1965), or on relationships, social interactions and personal identity within a particular cultural context (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). The implication of this is that understanding why people act as they do needs to take account of their past experiences; their values, beliefs, interests and agendas; the social situation in which they are working; and their sense of self (personal identity).

Social structures

The literature on critical realism provides a variety of guidance on social structures (e.g. Elder-Vass Citation2010, Scott Citation2010, Priestley Citation2011a). The definition found to be most helpful in the context of this study was that proposed by Scott (Citation2010). Scott identifies five ‘social structures’ – aspects of a social situation which can empower or constrain actors in exercising their agency: embodied, institutional, discursive, structures of agency, and social markers. These are explained in .

Table 1. Scott’s typology of social structures.

How the actions of agents are affected by structures will depend on a number of different factors. Scott calls these ‘modes of vertexicality’. Different agents will interact with the same structures in different ways, and that interaction will depend on a number of factors including the knowledge (professional and tacit) held by the agent, the flexibility (ability to resist or support change) of the structures and the opportunities for interaction and collaboration. The modes of vertexicality are defined in , alongside an interpretation of them in the context of teacher education. This provided a basis for thinking about what data to collect and provided a framework for semi-structured interviews with the teacher educators in the study.

Table 2. Modes of vertexicality.

In this small-scale study, by a researcher from the UK, visiting a Kenyan university this framework could be operationalized, because the structures could easily be interpreted in terms of aspects of teacher education that were accessible to an outsider.

Apart from its accessibility in the context of a small-scale study, and the guidance offered for data collection by the ‘modes of vertexicality’, the strength of Scott’s framework is the concept of ‘discursive’ structures. Firstly, the word ‘discursive’ implies that the ideas are visible in social interactions (which in educational settings they often are), evolving rather than static, and not separable from the relationships, institutional and embodied structures. Secondly, in the context of international development work, engaging with the prevailing collective (or individual) discursive structures and understanding how these relate to the ideas which underpin any proposed interventions, is likely to be a fruitful way of working with groups of actors at all levels of the system to bring about change. Before considering the methodology for this study, it is perhaps worth highlighting two other ways in which social structures have been conceptualized in the literature.

Elder-Vass (Citation2010) proposes a framework for studying social structures based on the sorts of groups that people form within an organization: the norm circle (close associates or colleagues), the interaction group (people who may work together for a while), associations (members of a wider group such as department or faculty) and the organization. To understand these structures, immersion in the situation over a long period of time would be required. Scott’s typology was much more easily interpreted in the context of an outsider investigating teacher education.

In her work, Archer (Citation1998a) separates ‘culture’ from ‘structures’ and treats ideas as cultural forms. Other studies in the field use her ideas and limit the discussion of ‘structures’ to institutional structures, with ideas being part of ‘culture’ and embodied structures not separately defined. Priestley (Citation2011a), and Hodgkinson-Williams et al. (Citation2017), for example, use a CR framework to examine the aspects of a new curriculum in two secondary schools and the uptake of open educational resources, respectively. Drawing on Archer (Citation1995) they regard ideas as ‘cultural forms’ separate from social structures, the implication being that ‘culture’ can be changed from outside an organization (Mannion et al. Citation2004), for example, by presenting a new curriculum. In Priestley’s study of the way in which different schools reacted to more subject integration in the curriculum (Citation2011a), the systems, processes and expectations built around the external examination system (an embodied structure) are not foregrounded. In both studies, the separation of the ideas from the social structures seems unhelpful in the context of a profession underpinned by rich, and often conflicting ideologies which are often reflected in the institutional structures.

This study sees ‘culture’ as emergent (Ormrod Citation2003), emerging as actors take action in a social situation, recognizing that the actions they take will be affected by the discursive structures that prevail in the situation. The implication is that changing the culture of an organization is not a deliberate act and has to come from within, through a focus on structure and agency and how they interact in the context of new ideas or a new embodied structure (such as a curriculum).

The interpretation of Scott’s typology for teacher education, therefore, created a link between the concepts of critical realism and the aspects of the field that I knew to be significant – ideas about learning and teaching, professional identity and the impact of the curriculum and assessment frameworks. It also identified a set of structures which were researchable given the limitations of time and distance. The ‘modes of vertexicality’ provided a defensible framework for the construction of a semi-structured interview schedule.

Developing a methodology

Critical-realist research requires ‘an intensive study, with a limited number of cases, where the researcher systematically analyses the interplay between the ontological layers’ (Bygstad et al. Citation2016, p. 85). This is because the causal mechanisms which arise from structures and actors are not observable (although the effects of those mechanisms are) (Bygstad et al. Citation2016), so the research needs to provide the opportunity to make inferences, based on evidence, that will uncover and describe the mechanisms which produce the observed events. This qualitative study, therefore, was based on working closely with five teacher educators in the same department of education, all of whom were involved in training secondary science teachers.

In order to investigate structure and agency, and ultimately to identify the underlying causal mechanisms which impact on teacher educators’ capacity (in this university) to be agents of change, a methodology was developed which provided

access to the social structures (discursive, institutional and embodied) that prevail in this department of education (Scott Citation2010, Fletcher Citation2017);

access to the past experiences, values, beliefs, interests and agendas (Checkland and Casar Citation1986, Davey Citation2010) of the participants, and their professional identity.

Other researchers working within a CR paradigm have conceptualized their work as a case study (e.g. Easton Citation2010, Davis Citation2013, Bygstad et al. Citation2016, Fletcher Citation2017). However, a key tenet of the CR paradigm is that reality is an ‘open system’ (Bhaskar Citation1994, Scott Citation2005, Wynn and Williams Citation2012) which is beyond our ability to control directly. This is not consistent with the notion of a ‘bounded’ case (Bassey Citation1999); it is not always clear at the outset where the inspiration for the inferences which will lead to the causal mechanisms will come from, and therefore how the case should be bounded. This study was therefore conceptualized as a small-scale ethnographic study which draws on multiple qualitative methods in order to understand the participants and the context in which they work.

Five teacher educators, who were known to the researcher took part in the study. They were interviewed on two of three occasions each and were observed interacting with student teachers. Departmental documents, policy frameworks, papers and textbooks are written by the participants were analysed to identify the embodied, discursive and institutional structures. For reasons explained later, ‘structures of agency’ and ‘social markers’ were dropped from the analysis. A semi-structured interview schedule was designed which probed participants’ past experiences, values, beliefs, attitudes and agendas. It was based on Scott’s typology for social structures, the factors which affect how individuals might interact with those structures (modes of vertexicality) and ideas surrounding professional identity from the literature on teacher education.

Critical realist interviews should be theory-driven (Smith and Elgar Citation2014), with the interviewer looking for evidence to confirm or falsify the theory; and constructivist, allowing participants to construct the ‘what’ during the interview process (McLachlan and Garcia Citation2015). This means that one tactic is to provide scenarios and ask participants to comment or to reflect back to the interviewee a summary of what they seem to be saying. In this context where a teacher educator was interviewing other teacher educators, what was not said was interesting and was taken as evidence (Rosiek and Heffernan Citation2014).

Data analysis

The study generated a considerable amount of data: interview transcripts, field notes, observation notes and a wealth of documentation. Drawing on other studies taking a CR perspective (Wynn and Williams Citation2012, Davis Citation2013, Tao Citation2013, Bygstad et al. Citation2016, Fletcher Citation2017), a framework for the analysis was devised, based on critical realism’s stratified ontology. Key concepts in this framework are abduction and retroduction.

‘Abduction seeks to interpret and re-contextualise individual phenomena within a contextual framework or a set of ideas in a way that seeks to elucidate underlying structures and causal mechanisms’ (Tikly Citation2015, p. 257). It involves looking for potential explanatory patterns and is the first step in developing theory (Åsvoll Citation2014). Retroduction involves inference – identifying the mechanisms that could explain the outcomes (or in this case the prospects for pedagogic change) and testing them against the evidence, through higher-order coding and cross-case analysis (Wynn and Williams Citation2012, Bygstad et al. Citation2016). Thus it can be considered to be ‘a distinctive form of inference … which posits that events are explained through identifying and hypothesising causal powers and mechanisms that can produce them’ (Hu Citation2018, p. 122). This involved looking back through all the data in a holistic manner, in order to find evidence for the proposed causal mechanisms.

Data analysis in a critical-realist paradigm

The process of data analysis used takes a holistic view of the data; it is theory-driven and makes explicit use of the processes of abduction and retroduction in order to identify the underlying causal mechanisms which explain the observed experiences. The data was tackled assuming that reality can be conceptualized in terms of three layers: the empirical (observable and measurable); the actual (accessible through interviews and observations) and the real (the underlying causal mechanisms which give rise to the observable events) (Tikly Citation2015). A six-stage process, was devised, drawing on Bygstad et al. (Citation2016) and Wynn and Williams (Citation2012). In stages 1 and 2, what can be taken to be known about the situation (empirical level of reality) was identified. In stage 3, evidence of the nature of the embodied, discursive and institutional structures was identified. In stage 4, what was known about each participant and their relationship with the structures (abduction) was synthesized. In stage 5, inferences to identify the underlying causal mechanisms were made (retroduction), which could give rise to the observations at the empirical level of reality, and in stage 6 conclusions were checked, considering alternative explanations. This is summarized in .

Stage 1: What is known about this situation?

The first question was ‘what is known about this situation?’ (the empirical layer). In a mixed-methods study, this would include quantitative data. In a qualitative study, it is less clear what constitutes the empirical level. In a study of why teachers are absent, Tao (Citation2013), bypassed the empirical layer, pointing out that it is effectively the statement of the problem. In this analysis aspects of the context that are not contentious but were relevant to the issues were identified. This included aspects where further analysis (in the ‘actual’ layer of reality) might reveal contradictions. In this study this involved analysing Government documentation in order to understand how pedagogic change is conceptualized in Kenya and describing features of the university course that are in the public domain.

Stage 2: The creation of a set of narratives about each participant

The second question was ‘what is known about the participants?’ Data from multiple sources were brought together in a professional narrative about each participant – a detailed description, incorporating quotes from all their interviews, relevant details from field notes, observation data, documents that provided further evidence about the things they talked about, and examples of their research outputs. The starting point was the interview and, as text from the interview was used, it was highlighted in the transcript. Sections that helped to understand the nature of the social structures and the activities of the participant were chosen. When each narrative account was complete, all the data which were not highlighted were checked to ensure nothing had been missed. This had the effect of combining the data in a holistic way and reducing them to a manageable form. The narratives were long – up to 20 pages – and were purely descriptive. The concept of a ‘professional narrative’ proved to be very powerful in the context of this study, as it brought together the data presenting a rich description of each participant, their motivations, their work, their professional relationships and ideas about teaching and learning. A narrative about the department in which the participants work was also created, drawing on field notes and departmental documents. There were some documents that were not incorporated into the narratives, so these were analysed separately, drawing on theories about learner-centred pedagogy, consistent with policy aspirations.

Stages 1 and 2 constitute what Bygstad et al., (Citation2016) call the ‘explication of events’. The narratives provide a ‘thick’ description (Freeman Citation2014), which describes the participant within their context. There was no interpretation at this stage, just a re-organization of the data to highlight what is known about the situation.

Stage 3: What are the social structures that impact on teacher-educator pedagogy?

Using Scott’s (Citation2010) typology of structures, the narratives and the other documents were examined for evidence about each structure type, in order to determine the nature of that structure in this context. Three types of social structure identified by Scott were relevant to the problem: discursive (the ideas that underpin the work of the individuals in this situation); embodied (aspects of the situation which restrain); and institutional (the roles, relationships, and resources), structures.

Using analysis software (Dedoose) excerpts of each narrative that provided evidence about the nature of the particular social structure were identified, with the aim of being able to describe them in this context. It was possible to ‘code’ each excerpt against more than one structure type, and to create sub-codes about the structure. All the excerpts relating to ‘discursive structures’, for example, were collected together to build up a picture of the ideas about teaching and learning which underpin the work of this group. By creating ‘sub-codes’ the analysis was driven by the theory (Scott’s typology (Citation2010) for social structures) but was allowing the data to highlight the nature of these structures. Sub-codes were influenced by the literature and inevitably, my own position as a teacher educator.

Working through the narratives, ‘memos’ were used to highlight anything else of interest. For example, building pedagogical content knowledge is an important aspect of learning to teach science (Loughran et al. Citation2004), so it was interesting to find out if and how it manifests itself, and the participants’ view of what it is and how significant it is. This was often an example of ‘coding by absence’ (Rosiek and Heffernan Citation2014), and the memo facility was a helpful way to track thoughts on such issues.

A category which emerged was ‘contradictions’. As each narrative was considered with respect to structure and agency, a number of obvious contradictions manifested themselves. The contradictions identified were:

Education policies expect new, active and learner-centred pedagogies (empirical level), but such pedagogies are not discussed or enacted (actual level).

The department has a good reputation in the area, with all the student teachers easily finding employment (empirical level), but analysis of course materials suggests that aspects of effective teaching (Hattie Citation2012) are not assessed. The focus of lesson observation is on the teacher, with little attention to learning. Success for students depends on the examination of theoretical knowledge.

Research is taken very seriously, with promotion prospects for academics depending on publications (empirical level) but the findings from research are not integrated into teaching (actual level of reality).

All participants identified strongly as scientists (empirical level) but the pedagogical content knowledge associated with teaching science (Shulman Citation1986) was absent from the course (actual level). Students did not discuss how to teach specific scientific topics that are known to be problematic.

Stage 4: How are structures experienced by agents, and how do agents influence structures?

As each narrative was analysed, a set of memos about ‘agency’ was created, identifying things that the participants felt they could and could not achieve, and evidence of how they interact with the structures. A vignette of each participant was produced. This was the abduction stage of the process, as the analysis moved beyond the thick description to interpret their behaviour with respect to the social structures, taking account of all the data. Each participant was characterized, and the terms which emerged included, for example, ‘follower’, ‘supporter’ and ‘drifter’. Each vignette highlighted how that individual interacted with the social structures. Looking across the vignettes, the causal mechanisms emerged.

Stage 5: Identifying the underlying causal mechanisms

This is the stage of the process called ‘retroduction’, where inferences are made based on the higher-order coding and cross-case analysis (Bygstad et al. Citation2016). To do this, I focused on the memos generated in stages 3 and 4. Causal mechanisms give rise to ‘events’ (in the actual layer) and ‘experiences’ (in the empirical layer). There were many possibilities at this stage, so the focus was on the research questions and causal mechanisms relevant to pedagogic change, and to my university’s international development work. I concluded that there were two possible explanations for the contradictions. The first was that knowledge about teaching was viewed as being objective, fixed and uncontested, with learning to teach involving learning a set of rules. The second was the lack of collaborative spaces – both physical and intellectual – which meant that new initiatives (just a pedagogical change) are not discussed or understood.

Stage 6: Empirical corroboration and triangulation

Having identified two important causal mechanisms, the data was re-visited, looking for evidence to substantiate the claims. CR asks us to consider alternative explanations and be highly critical of the theory we propose. In this case, the focus on professional practice limited the choice of relevant causal mechanisms. This stage involved re-examining the data, making sure that there was evidence for the chosen mechanisms across the data set and the extent to which they explained the contradictions identified in Stage 3. The aim was a clearer understanding of the causal factors and relationships, rather than repeated confirmations of an event (triangulation) (Bygstad et al. Citation2016).

The two causal mechanisms identified – the nature of knowledge about teaching, and a lack of collaborative spaces (both physical and intellectual) – explained the fact that despite a commitment to constructivist learning in science, ideas about active teaching and learning and learner-centred pedagogy cannot be accommodated in this course. Pedagogical content knowledge for example is subjective and contextual, and difficult to assess in a formal examination. The lack of collaboration about learning and teaching means that it is difficult to develop a collective understanding of new ideas and approaches. I include these at this stage, not to make a point about teacher education, but rather, to demonstrate to the reader what I understand by a causal mechanism. It is possible to explain all the contradictions identified at stage 3, in terms of these causal mechanisms. It was also possible to argue that a set of resources developed as part of an international development project (Teacher Education in sub-Saharan Africa: TESSA, www.tessafrica.net) were a causal mechanism which had not been activated. The resources are not embedded in this programme despite the involvement of this university in their development. If they were, they would challenge conceptions of knowledge about teaching and provide a route from the theory to practice to support pedagogic change. This study has provided insights that have influenced project activities and is making the work more impactful (e.g. Stutchbury et al. Citation2019).

Discussion

Critical realism has provided an analytical framework which yielded a contribution to knowledge about teacher education. The impenetrability of much of the literature surrounding critical realism, and the apparent philosophical complexity make it an unpopular choice as a paradigm for a small-scale study. Also, many interpretivists are uncomfortable with the concept of a ‘social reality’. I empathize with this view, but nevertheless would argue that there is something ‘real’ about a school ethos, for example – something that different people, with different experiences might agree about. Once the possibility of a ‘social reality’ is accepted, it becomes feasible to seek explanations. Much educational research exposes contradictions such as practices that do not reflect espoused beliefs or stated policy aspirations. Within a CR framework it is legitimate to seek explanations for this, although care is required as the explanations might be painful for individuals. In this study, I found a way of interpreting the tenets of critical realism which proved to be productive and highlighted explanations which have informed subsequent work in the field.

I was attracted by: the emphasis on seeking explanations; the recognition of the contribution that social theory can make to understanding complex situations, whilst recognizing that those theories are fallible; the central importance of context which fits in with my own experience of working as a teacher and teacher educator in many different settings; the concept of ‘emergence’, which recognizes that social phenomena cannot be reduced to the sum of the parts; the acceptance that reality is an ‘open system’ which is beyond our ability to control directly; and finally the stratified depth reality which provided a framework for the analysis of data.

The field of ‘critical realism’ spans many disciplines and authors within these fields do not seem to be learning from each other. In this study, the work of Scott (Citation2005, Citation2010) was found to be particularly helpful in operationalizing CR. However, although he writes from an Education perspective, his contribution is at a theoretical level and there are no practical accounts of how his concepts can be used. Practical studies in other fields which draw on CR (e.g. Davis Citation2013, Bygstad et al. Citation2016, Fletcher Citation2017) make no reference to the work of Scott. This provides the opportunity to examine the implications of his theoretical contributions and two points have emerged.

Firstly, the concept of ‘discursive structures’ is particularly helpful. This is the set of ideas which underpin the work of a group of professionals. In implementing any sort of educational change, I have come to the view that accessing the existing discursive structures and understanding how they align with the ideas underpinning the new, desired behaviours is hugely important, and could provide insights to inform professional development activities. It is the failure of policy makers to take sufficient account of existing discursive structures which is perhaps most likely to limit the successful implementation of new curricula or new pedagogy. In this study, it was the absence of explicit collective discussion around teacher learning that mitigated against the uptake of new pedagogy in teacher education, and the use of resources to support these new ideas. It also means that the embodied structures (such as the examination system and course outlines) that constrain agency with respect to new pedagogy, go unchallenged. Surfacing the discursive structures, produced new understandings.

The second strength of Scott’s analysis is his consideration of the factors affecting the ways in which actors will interact with existing structures. He lists four ‘modes of vertexicality’ which can all be interpreted for teacher education, as:

professional knowledge for teaching and of teaching;

the impact of embodied and institutional structures;

the possibilities for introducing new ideas or new practices;

how TEs interact with each other and the extent to which ideas spread within the group.

In this study, they provided a defensible basis for a semi-structured interview. However, as a result of working closely with these five individuals, ‘individual intention’ emerges as a key factor which determines how an actor will interact with, and change, the prevailing social structures. Individual intention covers attitudes, values and beliefs developed as a result of taking part in the social world, and determines what an individual will notice, how they discriminate and how they make judgements about how to act (Checkland and Casar Citation1986). In this study, the literature review involved a discussion of professional identity (which also informed the interview schedule) as this is important in the context of teacher education, so ‘individual intention’ was covered. The inclusion of a fifth ‘mode of vertexicality’ which recognizes the importance of individual intentions and motivations for change would strengthen Scott’s theory for use in other fields.

Scott’s typology conceptualized the social structures in a researchable form; in a way which could easily be interpreted in terms of the ideas underpinning teacher education; and was realistic in the context of international development. Archer’s (Citation1995) suggestion that ‘culture’ is a ‘thing’ that is separate from the social structures is not helpful for outsiders. We are under no illusion that introducing new ideas will change the culture of a university department of education. However, over time as people make small changes in practice, it is possible that the discursive structures may evolve, leading to circumstances in which the embodied structures (those that resist change) might be challenged. This study provided insights which have changed how we talk about the ideas that underpin TESSA resources, leading to new interest in what they have to offer.

The implications of CR for small-scale qualitative studies

One of the reasons given for choosing CR is that it enables the researcher to go beyond the thick descriptions of interpretivism and seek explanations (Tikly Citation2015). An interpretative study designed to understand the work of a professional group would have probably identified the four contradictions that emerged at stage 3 and stage 4 of the analysis. But in order to seek explanations, we have to assume that there is ‘something’ to find out: the realist ontology enables us to make inferences. However, this approach is not without difficulties, and produced some significant ethical dilemmas.

Research like this – an ethnographic study – has the potential to be quite intrusive. It became apparent during the interviews that ‘structures of agency’ should be dropped from the analysis and that the focus should be the ways in which embodied, discursive and institutional structures enable and constrain agency. There is no doubt that some of the ‘causal mechanisms’ constraining or enabling change in any institution will involve the actions or characteristics of specific individuals (structures of agency), but it is not the place of outsiders to investigate those, unless specifically invited to do so. Nor was knowledge of ‘structures of agency’ helpful in the context of the research dilemma – the slow uptake of ideas that are consistent with policy aspirations – as the project team have no direct influence over the roles and individuals in an institution.

It would be difficult to carry out a study like this as a complete outsider, as it takes time to establish the sort of trust that enabled these participants to be open and honest, and to tolerate lengthy, in-depth interviews. In this case, I occupied a curious position moving between an insider and outsider (Dwyer and Buckle Citation2009, Savvides et al. Citation2014, Milligan Citation2016). As a UK citizen visiting Africa, I was an outsider. However, having worked with colleagues in this university over a number of years, and as a teacher educator myself I could be considered to be an insider. Two participants had worked with the TESSA project in the past and had achieved recognition and promotion in their setting as a result of this work. It is unusual to be in this position and is something that researchers undertaking a small-scale study like this should consider carefully. Obtaining the depth required by this framework could be challenging in an unfamiliar situation or in one which relationships did not already exist.

Maintaining anonymity was also difficult given the need to provide a detailed description of the context. The heavy reliance on documents means that references to the work of the participants had to be removed from accounts of the project.

Probing causality has the potential to uncover aspects of a situation that could make members of the community uncomfortable. However, understanding the reasons behind apparent contradictions between policy and practice, has potential to contribute to the common good. A careful balance needs to be struck, with care and concern for the participants at every stage of the research. The relationship with the participants is such that I could feed back my findings in full. I provided a detailed written summary of the study with some recommendations for practice, which they greatly appreciated. I would want to provide some sort of mediation, however, before they read my thesis.

The other circumstances in which this sort of study could make a valuable contribution is one in which an institution or organization decide from within that they want explanations that will help them to improve what they do. ‘Insiders’ might decide to invite in co-researchers, or consultants, but in those circumstances would genuinely own the ‘problem’ and the findings. Increasingly, educational researchers are keen to involve children as co-researchers (e.g. Kellet Citation2011). Children are in a position to contribute rich descriptive data which goes beyond the formal accounts provided by teachers but are unlikely to be able to make inferences as their knowledge of the underlying structures and the factors affecting teachers’ agency will be limited. CR sees reality as an ‘open system’ which in educational research implies that making inferences requires knowledge of the wider context.

Conclusion

Despite the complexity of the literature surrounding critical realism, it has proved to be a helpful explanatory framework in this small-scale study. This study demonstrated that it can provide a set of analytical tools to support every stage of an investigation. Finding a definition of social structures that works for an ‘outsider’ researcher in the field of Education was particularly helpful. The use of Scott’s typology for social structures was productive, especially as it highlights the ideas that underpin the activities of a social group (discursive structures) as a social structure with causal powers. Much activity in the field of Education, is underpinned by well-documented and enthusiastically held ideas about learning, teaching and knowledge. Surfacing these ideas and interrogating how they might constrain or empower individuals in the face of new initiatives is likely to be productive for educational researchers. Likewise, the notion of fixed (embodied) structures which resist change, such as the curriculum and examination system – will be recognizable to those trying to understand as aspects of the field.

Over time, I have come to see critical realism as ‘common sense’ rather than an ‘unnecessary edifice’. This is perhaps because the notion of a ‘stratified reality’ is recognizable in many social situations. Particularly in politics and in organizational life, there is often a hidden agenda and invisible forces that impact on what is apparently happening. Well-intentioned and apparently sensible initiatives sometimes fail for reasons that no-one quite understands or have consequences that were not anticipated (emergence). CR therefore formalizes something that I recognize and gives it a strong theoretical underpinning.

However, this sort of research can potentially be intrusive. Asking ‘why’ questions can expose participants and making inferences might be considered to be judgemental in situations where researchers are not previously known to participants. In research of this nature, it is likely that the unintended consequences of policy initiatives, or interventions will emerge, which could be difficult or contentious for those concerned. If these initiatives rely on public funds, or charitable donations, it could be argued, however, that there is a moral justification for this kind of work. Despite the potential benefits, it is a paradigm that needs to be implemented cautiously and reflexively. This study demonstrates that it is certainly not an ‘unhelpful edifice’.

Acknowledgements

The field work for this study was funded by a travel grant from the University Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET). I would like to thank the participants in this study who welcomed me into their institution and the reviewers for their helpful feedback on the first draft of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Archer, M., 1995. Realist social theory: the morphogenetic approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Archer, M., 1998a. Realism and morphogenesis. In: M. Archer, R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawson, and A. Norrie, eds. Critical realism: essential readings. Abingdon: Routledge, 356–381.

- Archer, M., 1998b. Realism in the social sciences. In: M. Archer, R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawson, and A. Norrie, eds. Critical realism: essential readings. Abingdon: Routledge, 189–205.

- Åsvoll, H., 2014. Abduction, deduction and induction: can these concepts be used for an understanding of methodological processes in interpretative case studies? International journal of qualitative studies in education (QSE), 27 (3), 289–307. a9h. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.759296 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Bassey, M., 1999. Case study research in educational settings. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Bhaskar, R., 1994. Plato etc: the problems of philosophy and their resolution. New York: Verso.

- Bhaskar, R., 1998. Facts and values: theory and practice. In: M. Archer, R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawson, and A. Norrie, eds. Critical realism: essential readings. Abingdon: Routledge, 409–417.

- Bold, T., et al., 2017. What do teachers know and do? Does it matter? Evidence from primary schools in Africa (Policy Research Working Paper No. 7956). World Bank Group. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/882091485440895147/pdf/WPS7956.pdf [Accessed 14 Jul 2021].

- Bygstad, B., Munkvold, B.E., and Volkoff, O., 2016. Identifying generative mechanisms through affordances: a framework for critical realist data analysis. Journal of information technology 31, 83–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.13.

- Checkland, P. and Casar, A., 1986. Vickers’ Concept of an Appreciative System: A Systemic Account. Journal of allied systems analysis 13, 3–17.

- Checkland, K., Harrison, S., and Marshall, M., 2007. Is the metaphor of ‘barriers to change’ useful in understanding implementation? Evidence from general medical practice. Journal of health services research & policy, 12 (2), 95–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1258/135581907780279657 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Checkland, P. and Poulter, J., 2006. Learning for action. Chichester: Wiley.

- Cochran-Smith, M., 2003. Learning and unlearning: the education of teacher educators. Teaching and teacher education, 19, 5–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00091-4 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Cochran-Smith, M., 2006. Teacher education and the need for public intellectuals. The new educator 2 (3), 181–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15476880600820136 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Cochran-Smith, M. and Boston College Evidence Team, 2009. ‘Re-culturing’ teacher education: inquiry, evidence and action. Journal of teacher education, 60 (5), 458–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109347206.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Stringer Keefe, E., and Carney, M.C., 2018. Teacher educators as reformers: competing agendas. European journal of teacher education, 41 (5), 572–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2018.1523391 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Davey, R.L., 2010. Career on the cusp? The professional identity of teacher educators. Available from: http://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10092/4146/thesis_fulltext.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 24 May 2018].

- Davis, S., 2013. Workers’ educational association: a crisis of identity? Personal perspectives on changing professional identities. PhD, Leeds Beckett. Available from: http://eprints.leedsbeckett.ac.uk/581/1/PhD%20Thesis%202014.pdf [Accessed 24 May 2018].

- Dembele, M. and Miaro-II, B.-R., 2013. Pedagogical renewal and teacher development in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and promising paths. In: B. Moon, ed. Teacher education and the challenge of development: a global analysis. Abingdon: Routledge, 183–196.

- Dwyer, S.C. and Buckle, J.L., 2009. The space between: on being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International journal of qualitative methods, 8 (1), 54–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Easton, G., 2010. Critical realism in case study research. Industrial marketing management, 39, 118–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.06.004.

- Elder-Vass, D., 2007. Reconciling Archer and Bourdieu in an emergent theory of action. Sociological theory, 25 (4), 325–346. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20453087 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Elder-Vass, D., 2010. The causal power of social structures: emergence, structure and agency. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fletcher, A.J., 2017. Applying critical realism in qualitative research: methodology meets method. International journal of social research methodology, 20 (2), 181–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2008.06.004.

- Freeman, M., 2014. The hermeneutical aesthetics of thick description. Qualitative inquiry, 20 (6), 827–833. a9h. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530267.

- Hattie, J., 2012. Visible learning for teachers: maximising impact on learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C., et al., 2017. Factors influencing open educational practices and OER in the global south: meta-synthesis of the ROER4D project. In: C. Hodgkinson-Williams and P. Arinto, eds. Adoption and impact of OER in the global south. Cape Town: African Minds, International Development Research Centre & Research on Open Educational Resources, 27–68.

- Hu, X., 2018. Methodological implications of critical realism for entrepreneurship research. Journal of critical realism, 17 (2), 118–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1454705.

- Katitia, D.M.O., 2015. Teacher education preparation program for 21st century. Which way forward for Kenya? Journal of education and practice, 6 (24), 57–64.

- Kellet, M., 2011. Empowering children and young people as researchers: overcoming barriers and building capacity. Child indicators research, 4 (2), doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-010-9103-1.

- Lave, J. and Wenger, E., 1991. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lipponen, L. and Kumpulainen, K., 2011. Acting as accountable authors: creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and teacher education, 27, 812–819. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.001.

- Loughran, J., Mulhall, P., and Berry, A., 2004. In search of pedagogical content knowledge in science: developing ways of articulating and documenting professional practice. Journal of research in science teaching, 41 (4), 370–391. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20007.

- Mannion, R., Davies, H.T.O., and Marshall, M.N., 2004. Cultures for performance in healthcare. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Marks, A. and O’Mahoney, J., 2014. Researching identity: a critical realist approach. In: P. Edwards, J. O’Mahoney, and S. Vincent, eds. Putting critical realism into practice: a guide to research methods in organization studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 66–85.

- McLachlan, C.J. and Garcia, R.J., 2015. Philosophy in practice? Doctoral struggles with ontology and subjectivity in qualitative interviewing. Management learning, 46 (2), 195–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507615574634.

- Milligan, L., 2016. Insider-outsider-inbetweener? Researcher positioning, participative methods and cross-cultural educational research. Compare: a journal of comparative and international education, 46 (2), 235–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2014.928510 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Moon, B. and Umar, A., 2013. Reorientating the agenda. In: B. Moon, ed. Teacher education and the challenge of development. Abingdon: Routledge, 227–238.

- Ormrod, S., 2003. Organisational culture in health service policy and research: ‘third way’ political fad or policy development? Policy and politics, 31 (2), 227–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1332/030557303765371717 [Accessed 27 Jul 2021].

- O’Sullivan, M., 2010. Educating the teacher educator—a Ugandan case study. International journal of educational development, 30, 377–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.12.005 [Accessed 27/07/21].

- Price, L. and Martin, L., 2018. Introduction to the special issue: applied critical realism in the social sciences. Journal of critical realism, 17 (2), 89–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2018.1468148 [Accessed 27 Jul 2021].

- Priestley, M., 2011a. Schools, teachers and curriculum change: a balancing act? Journal of educational change, 12 (1), 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-010-9140-z [Accessed 27 Jul 2021].

- Priestley, M., 2011b. Whatever happened to curriculum theory? Critical realism and curriculum change. Pedagogy, culture & society, 19 (2), 221–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2011.582258 [Accessed 12 Jul 2021].

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S., 2015. Teacher agency: what it is and why does it matter? In: J. Evers and R. Kneyber, eds. Flip the system: changing education from the ground up. Abingdon: Routledge, 134–148.

- Rosiek, J.L. and Heffernan, J., 2014. Can’t code what the community can’t see: a case of the erasure of heteronormative harassment. Qualitative inquiry, 20 (6), 726–733. a9h. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530255.

- Savvides, N., et al., 2014. Journeys into inner/outer space: reflections on the methodological challengers of negotiating insider/outsider status in international educational research. Research in comparative and international education, 9 (4), 412–425. doi:https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2014.9.4.412 [Accessed 27 Jul 2021].

- Scott, D., 2005. Critical realism and empirical research methods in education. Journal of the philosophy of education, 39 (4), 633–646.

- Scott, D., 2010. Education, epistemology and critical realism. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shulman, L.S., 1986. Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educational researcher, 15, 4–14.

- Smith, C. and Elgar, T., 2014. Critical realism and interviewing subjects. In: P.K. Edwards, J. O’Mahoney, and S. Vincent, eds. Studying organizations using critical realism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 109–131.

- Stutchbury, K., 2019. Teacher educators as agents of change? A critical realist study of a group of teacher educators in a Kenyan university. Doctorate in Education, The Open University. Available from: http://oro.open.ac.uk/67021/.

- Stutchbury, K., Amos, S., and Chamberlain, L., 2019. Supporting professional development through MOOCs: the TESSA experience. Pan Commonwealth Forum 9, Edinburgh. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/11599/3340 [Accessed 23 May 2019].

- Tao, S., 2013. Why are teachers absent? Utilising the capability approach and critical realism to explain teacher performance in Tanzania. International journal of educational development, 33, 2–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.01.003 [Accessed 12/07/21.

- Tao, S., 2016. Transforming teacher quality in the global south: using capabilities and causality to re-examine teacher performance. Basingstoke: Palgrave, MacMillan.

- Tikly, L., 2015. What works, for whom, and in what circumstances? Towards a critical realist understanding of learning in international and comparative education. International journal of educational development, 40, 237–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.11.008 [Accessed 27 Jul 2021].

- Vickers, G., 1965. The art of judgement. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Vickers, G., 1968. Value systems and social process. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Wynn, D. and Williams, C.K., 2012. Principles for constructing critical realist case study research in information systems. MIS quarterly, 36 (3), 787–810. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/41703481.