ABSTRACT

Constructivist grounded theory has earned a place in research worldwide and been applied in diverse fields. However, in educational research of teachers’ work in the classroom from the perspective of the teacher, it has had a lesser impact on research methodology. We argue for the benefits to educational research when using a constructivist grounded theory methodology. Our arguments focus on three concrete benefits: (1) Constructivist grounded theory focuses on participants’ perspectives, or main concerns, (2) by using an open, exploratory approach, and, (3) could involve investigating the relationships between the focused codes, preferably by using theoretical coding. We argue that constructivist grounded theory adds an analytical edge to work in classrooms, when skilfully deployed. These benefits with constructivist grounded theory differentiate the approach against other qualitative methods. Another important feature is focusing on the actions, and social processes, and thus making use of several theoretical codes. As we will outline in this paper, these features of constructivist grounded theory could help produce theoretical insights that could be valuable additions to educational research and educational practices.

Introduction

To our knowledge, there is a lack of grounded theory studies focusing on teachers’ work in the classroom. We argue for the potential of utilizing constructivist grounded theory (CGT) and engaging educational research in the primary work of teachers in classrooms as a social process, from the perspective of the teacher and with their main concern as a guide to understanding the complex nature of classroom teaching. Using grounded theory to conduct research focused on teachers’ main concerns could help spark theoretical insights of value to educational research and educational practices of crucial value in a context where numerous discourses and opinions circulate about school, education, and teachers’ work in media, society and elsewhere. Studying social processes, with a particular focus on the participants’ perspectives and main concern, are features that are included in CGT. In this paper, we argue for the constructivist version of grounded theory, as we believe that this version could best add new insights to educational research, especially teachers’ work, when skilfully deployed (cf. Bryant Citation2019).

To begin with, we acknowledge that there are several other methods that are useful and create an essential body of knowledge concerning teachers’ work. For example, phenomenology, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis, among others, have been used in empirical studies in educational research. There are also other analysis methods that focus on the participants’ perspectives, such as concept mapping (Striepe Citation2020). In addition, we do believe grounded theory has been useful in the past. Why we favour CGT in relation to both other qualitative methods and past versions of the grounded theory approach is because it offers a theory–method package that we find particularly useful when wanting to explore social processes in the classroom. In comparison with earlier versions of the grounded theory approach, CGT positions the researcher as a co-constructor of the data, something which we find crucial in contemporary research today. The Glasserian and Straussian version argues that the researcher can and should set aside earlier knowledges and let data emerge (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967, Glaser Citation1978). Another crucial difference is the emphasison symbolic interactionism. In the more classic version of grounded theory (Glaser Citation2003) it would be argued that placing grounded theory within a symbolic interactionist position is forcing a theoretical perspective on the data. While the Straussian version more recently has acknowledged both a constructivist position and the theoretical heritage of grounded theory, it is the CGT approach promoted by Charmaz (Citation2014) which has advanced these issues fully. In this way, the CGT versions offer a theory–method package combined with symbolic interactionism. According to Charmaz (Citation2014), symbolic interactionism offers CGT an open-ended theoretical perspective, creating a theory–method package incorporating curiosity, openness, and a sense of wonder about the social world and its ongoing social actions and processes. Thus, we take our starting point in the constructivist version, and we write from the standpoint that subjective meanings are co-constructed and interpreted by people in social interaction, communication, and practice. The data is considered, as a constructivist standpoint implies, to be co-constructed by the participants and in the interplay between the researchers and the participants, and coloured by the researchers’ perspectives (Charmaz Citation2014). We acknowledge that using grounded theory also involves interpretative work that is influenced by our previous knowledge and experiences (Charmaz Citation2014).

In discussing differences among versions of grounded theory, in the constructivist version of grounded theory the context in which actions take place is relevant. Even though a theory might be decontextualized, researchers should be aware of the forcing that may be undertaken to fit a theory from one context into another field. Charmaz (Citation2014) argues that decontextualization might ‘reduce opportunities to create theoretical complexity because decontextualization fosters oversimplification and can abbreviate the comparative process’ (p. 243). This is important to consider when trying to understand teachers’ work and doing educational research. In addition, in CGT, the researcher is not positioned as being able to put their own knowledge aside and view themselves as a ‘tabula rasa’. Rather, we focus on staying open and curious in the research process and apply the notion of having an open mind, rather than an empty page (Dey Citation1993). This is also relevant in relation to how we viewed the research process and data. In the constructivist version, we assume that the researchers construct the codes used to create a coherent analytical story (Charmaz Citation2014). This could end up being problematic, since all grounded theories constructed then must rely on a certain set of quality criteria that rely on the usefulness of the theory (Charmaz Citation2014), but in fact the theory might seldom come to be tested either by practising teachers or researchers. Furthermore, the theories constructed might sometimes be limited in suggested implications, and seldom explore what should be done as a result of the study. We believe that research of classroom practices, therefore, is particularly suitable since it could generate a theory that could be tested in practice. To illustrate and problematize the value of grounded theory, we exemplify with our studies about the social and psychological processes of coping with emotionally challenging episodes when starting to teach and in teacher education (for example Lindqvist Citation2019a), and in relation to bullying (for example Forsberg Citation2016).

Constant resolving of main concerns

When using a grounded theory approach, researchers aim to gain a significant level of understanding. Being attentive to, and grounding the iterative analysis in, the perspectives of the participants is connected to focusing on the participants’ main concern(s) in relation to a phenomenon. This involves staying attentive to the participant, which is true for most qualitative methods. However, a prominent feature in the grounded theory approach is its constant focus on how the participants resolvetheir main concerns . This is apparent in how data is constructed and analysed where there is a back-and-forth movement between analysis and data collection. As we begin to code and analyse our data to try to construct the main concern of the participants, we also encounter new questions and analytical leads that we follow up by collecting more data to stay attentive to the participants’ perspectives, so as not to attribute their concern to something they do not recognize. In summarizing a group of participants’ main concern, the level of precision must be accurate in order for the following analytical work to bear any meaning. Is that possible to achieve? We argue that it is, and this is apparent when grounded theory is described by Charmaz (Citation2011) in contrast to other qualitative analytical methods.

While reading the analysis, I felt that my words and their meaning were being carefully considered, even felt, by the researcher, who felt more like a concerned friend than an inquisitive scientific explorer. Moreover, she was a concerned friend who was really listening. In the end, the main theme of ‘losing and regaining a valued self’ struck me as very much on the mark with how I see things now, in hindsight, when reflecting on what I went through then. (Charmaz Citation2011, p. 344–345)

This quote comes from a participant who was interviewed, and the interview data later analysed, by five different researchers using different methods of qualitative analysis to approach the material. When asked to reflect on the five different interpretations of her interview, this is how the participant experienced the grounded theory analysis. The categories must fit the data, be relevant for understanding the actions of the area being researched, and explain what is going on in the area investigated. One might conclude, with reference to the participant’s experience above, that the theory constructed met these criteria, even though we do not know if it met the pragmatist’s criterion of being a theory that ‘works’. Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) found it important to start an inquiry from the participants’ perspectives, as they, and not the researchers, are the experts on their context. To assume otherwise would be insulting to the knowledgeable participant. Commonly, participants’ perspectives are investigated through intensive interviewing, where the researcher and participants co-construct the data (Charmaz Citation2014). Being the subject of intensive interviewing holds frustrations as well as rewards (Taber and Student Citation2003). However, the researcher can contribute important theoretical understandings and perspectives on the data (Glaser Citation1978). Taking these issues seriously means starting an inquiry by trying to grasp and explore what is going on in the area or data – what seems to be crucial for the participants, what is/are their main concern/s? As Charmaz (Citation2011) puts it, she strives to start from the participants’ perspectives and begins the analysis from their views and perspectives, involving an ‘empathetic understanding to discover how people construct their lives and why they act as they do’ (Charmaz Citation2011, p. 292). In this way, the researcher does not force their own theories or understandings on the context. When Lindqvist and colleagues (Citation2017) worked with analyses in their study of student teachers’ emotionally challenging episodes in teacher education, the student teachers’ main concern was described as ‘how to retain positive professional identity development by managing threatening feelings of professional inadequacy’. When analysing the data, and engaging in the iterative construction of a theory, it was apparent that the feeling of professional inadequacy was a main concern of the student teachers, and their feelings, and anticipated feelings of professional inadequacy threatened their identity as a teacher. This also requires some caution: researchers must stay attentive to the participants, and thus, there might be a risk of depicting this as an affirmative conclusion. Instead, here we try to focus on the processes that, according to the analysis, lead to feelings of professional inadequacy. Establishing the main concern in the analysis might take away all the focus from a variation of main concerns (cf. Charmaz Citation2014).

In data collection, such as intensive interviewing (Charmaz Citation2014), this includes listening carefully to the participant, and using open and probing questions to try to grasp their perspectives. Interviews are one of several possible data sources that can be used in grounded theory studies, but the approach is similar whatever the data source. Constantly trying to understand the main concerns of the participants in practice means following up on new questions that arise from data collection and analyses, trying to grasp as much as possible of what is going on and what seems to be the emergent problem that participants face, and constantly asking questions of the data and exploring categories constructed from the data. Moreover, it means analysing the data, and later presenting the analysis in a way that places attention on the main concerns of the participant and incorporating theoretical concepts that fit with the data. Researchers performing grounded theory analysis do not uncritically report the participants’ perspectives, as we act on and interpret data (Charmaz Citation2014).

In this way, the participants’ understanding of their main concern is what drives and motivates their actions. To resolve the things that matter in their work lives, the aim is to be able to describe how the participants engage in action that could be seen as a way of resolving their main concern. We do acknowledge the constraints of using a narrative of grounded theory as linear – it is a messy process – and we also acknowledge the need for a pragmatic view of using several methodologies (Clarke and Visser Citation2019). For example, weakness of CGT might be the narrow focus that sometimes might be the result, when researchers choose what to focus on. Using another method when analysing might involve a wider representation of categories, themes, or views. In CGT there is an emphasis on the flexible use of theories and analytical tools (Charmaz Citation2014). For example, Lindqvist et al. (Citation2017) describe how student teachers grapple with understanding their future professional identity through experiencing professional inadequacy. The main concern of the student teachers was to make sense of and resolve their main concern of experiencing inadequacy. To do that, the student teachers used two strategies to resolve feelings of inadequacy: the acceptance and the postponing strategies. This is an example of how the participants’ actions and how their perspectives and actions are considered, and it also illuminates how this process of resolving feelings of inadequacy has an impact on their professional identity. All this is possible due to the grounded theory methodology, and using another method theory package would most likely not explore this distinction, as it also involves trying to explore the relationships among and between codes.

A symbolic interactionist perspective

When investigating the participants’ main concern, and as such trying to be sensitive to the perspective of the insider, there is relevance in considering symbolic interactionism as an overarching theoretical framework. Charmazet al (Citation2019) describe symbolic interactionism as offering ‘a lens for looking at ourselves, everyday life, and the world, not an explanatory theory that specifies variables and predicts outcomes’ (p. 19). In addition, it is relevant because symbolic interactionism is usable when looking at everyday life and main concerns, as people always see and make sense of reality through their perspectives and according to what value people, places, and objects have for them (Blumer Citation1969, Charon Citation2006, Charmaz et al. Citation2019). In symbolic interactionism, the focus is on subjective meanings and actions, and as such the theoretical framework rests on the notion of the ongoing process of negotiating positions through constructing meaning from interactional practices. In accordance with the Thomas theorem (Thomas and Thomas Citation1928), participants’ perspectives are not considered to be objectively true, but will have actual consequences for their actions. It is therefore sensible to include the perspectives of the participants when trying to establish a main concern of the participants, and their efforts to resolve their main concern.

Furthermore, Charon (Citation2006) states that a perspective is ‘an angle on reality, a place where the individual stands as he or she looks at and tries to understand reality’ (p. 3). In addition, we must assume that a person knows and can give accounts of their perspective, with a focus on what type of action this would enable. When a person interprets their existence, they need to categorize and make meaning of things, situations, meetings, daily hassles, and major events. We argue that symbolic interactionism is a sensible overarching theory for CGT, and not forced on the participants’ perspectives. The focus on examining the insider perspective in social situations to better understand peoples’ actions and social interactions also resonates with the ambitions of CGT (Charon Citation2006, Charmaz Citation2014). Symbolic interactionism is suitable because we are interested in analysing and conceptualizing the social processes and actions of the participants (Charmaz Citation2014). However, this does not mean that symbolic interactionism will be an analytical perspective when constructing our theory of the data. In line with a pragmatist’s views, extant theories of varied origin could be used to do this. For example, Lindqvist (Citation2019a) states that when ‘viewing an educational experience through the intersection of different perspectives. These perspectives involve social presence, teaching presence and cognitive presence, all of which help us to understand the educational experience’ (p. 96). Leaving a perspective out of the analysis might render a less varied understanding of a phenomenon. Here, CGT offers a way of connecting pragmatism and symbolic interactionism with a method (Charmaz Citation2017). A critique might then involve the lack of precision, and how the abductive logic of CGT might give way to ‘anything-goes analysis’. Therefore, the researcher/s/ has/have to be able to show that the analysis is grounded in the data through the use of extensive coding. With the constant attention on the main concern of the participants, and trying to dig deeper into their perspectives, this requires an open and exploratory analytical process.

An open and exploratory analytical approach

Despite the differences between different versions of the grounded theory approach previously outlined, they do share common ground when it comes to building a theory from meticulously paying attention to the data and the participants’ perspective or main concern (Thornberg Citation2017). In all versions of grounded theory, coding is the primary tool used to work with data analysis. Other similarities among different versions of grounded theory involve using several levels of coding, engaging in constant comparison (Hallberg Citation2006) and establishing a theory that is grounded in the analysis of the data. All versions of grounded theory use a first, initial, or open coding to work through the data material. In later phases of coding the researcher is being more selective and focused (as shown in ).

Table 1. Three phases of coding in grounded theory.

The phases of coding are pathways in understanding the data, and the coding procedure is a messy process. It is far from a linear process or performed in stages, as commonly depicted when describing methods (cf. Forsberg Citation2016, Lindqvist Citation2019a). CGT could be viewed as a way of staying close to the data, and in a flexible manner using tools to put the participants’ perspectives in focus. The use of tools such as coding, constant comparison between codes, writing analytical reflections about codes through memo writing, and sorting these memos are important tools in the research process but can also be used in a flexible manner (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967, Citation1978, Charmaz Citation2014). The three stages of initial, focused, and theoretical coding do not happen in a strictly linear fashion. To be able to be sensitive to the data, the stages of coding are, in fact, often flexible and intertwined, with theoretical and focused coding performed, more or less in parallel. During the analytical work, it is common to write memos to elaborate on the focused coding, and in order to try out theoretical codes (cf. Charmaz Citation2014).

The first set of codes given to the data material are to be constructed in a swift manner. In the first coding of text, or the data material, codes are constructed using gerunds, focusing on the actions of the participants (Charmaz Citation2014). In this word-by-word, line-by-line, or segment-by-segment coding the focus is on staying close to the data, being attentive and curious about the participants’ actions. In this coding it is important to carry on and not get stuck with formulations of the codes. Sometimes these codes are constructed words or combinations of words (for example, explanation-bias-developing). The initial coding ‘guides our learning. Through it we begin to make sense of our data’ (Charmaz Citation2014, p. 114). The coding is exemplified in .

Table 2. Example of initial coding using gerunds.

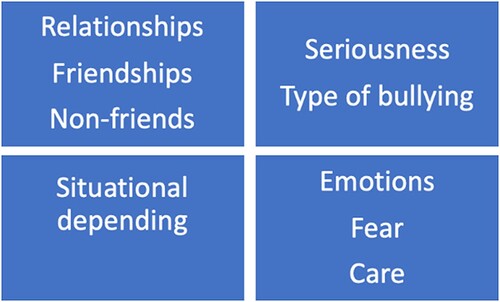

As can be seen from this example, the codes stay close to the data and put attention on the actions and on what they depend on according to the participant. We get a lot of ideas on what processes might be of importance when being a bystander to bullying (e.g. social relationships, friendships, views of seriousness, and situational caring). However, as illustrated in this small example of initial coding, it can sometimes yield many codes so it will be of crucial concern for the further analysis to select codes based on what appears to be the most telling or most comprehensive codes according to the participants’ main concern(s) in the studied area. With that said, initial codes are also provisional, as they may later be reworded to make a better fit with the data and analysis. Initial codes can also be influenced with concepts from symbolic interactionism if they fit your data and help the researcher to identify on what aspects further data collection is needed (Charmaz Citation2014). When having selected codes, it is time for the next set of coding-focused coding. In focused coding, the initial codes are further conceptualized through clusters of codes that are created as focused codes. As there are usually a lot of initial codes, not all of them are used. This might be a critique against CGT; a lot of the energy of the researcher is used in a way that does not directly align with the result. In addition, it might be difficult for some to choose which initial codes to bring to focused coding, whereas for others it is more obvious. There are some guidelines for how to proceed with these matters (cf. Charmaz Citation2014). Focused coding contributes with an exploration of your initial codes, how much they capture, and what patterns can be seen at this stage. It helps to organize the data and the analysis and engages in comparisons that sharpen your conceptualizations. To exemplify focused coding, let’s return to the initial coding in . This initial coding was part of a study focusing on students’ perspectives on bullying and being bystanders to bullying (Forsberget al. Citation2014). Throughout initial coding the students were recurrently referring to how their reactions as bystanders were informed by relationships, definitions of seriousness, and a form of situational caring. These and a few other codes were used as focused codes (see ) to check against the data and each other to explore what patterns could be conceptualized.

The analytical work of CGT also sometimes involves theoretical coding, using the theoretical code families that Glaser (Citation1978, Citation1998, Citation2003) published to further develop a theory and explore the relationships among the codes. Therefore, the analytical work is time-consuming and extensive, and some researchers might consider this to be unnecessary, but in the grounded theory methodology we consider it necessary to retain our analysis as grounded in the data. Returning to , the next step here would be to explore the relationships between codes and theoretical coding. Relationships between focused codes and theoretical coding is further discussed below.

Relationships among and between focused codes

Focused codes are raised to categories by constructing working definitions. In theoretical coding, possible relationships between categories are examined in order to integrate them into a story with coherence (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2012). With focused coding and theoretical coding commonly being done in parallel, the relationship among codes and possible connections to code families have the possibility to enhance educational research. Theoretical coding is an antecedent from Glaser (Citation1978, Citation1998, Citation2003), who published code families that refer to a set of theoretical concepts that are commonly used in the analysis of possible relations between the focused codes or categories. Theoretical coding illustrates the relationship among codes and refers to using ‘underlying logics that can be found in other theories’ (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014, p. 159). Theoretical coding could be used in CGT to enhance the theories constructed in the analysis. Despite this possibility, using theoretical codes could mean an over-reliance on a certain code family, as for example the code family strategy, which could be applied widely. Charmaz (Citation2014, p. 153) argues that

the chosen concept may prelude attending to emergence of other possible theoretical codes. Theoretical codes focused on strategizing, for example, can prelude attending to actions that do not aim to control other people and also leave out spontaneity, whimsy, and happenchance.

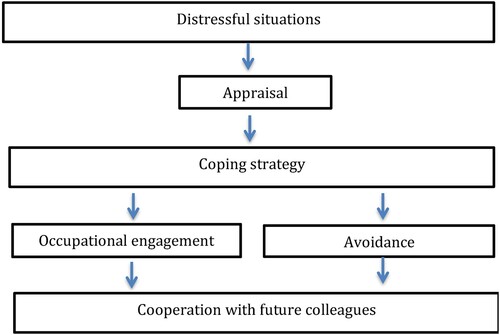

In further analytical work, Lindqvist (Citation2019b) concluded that the model did not fit the data, and the focused codes used in theoretical coding had to be given more attention. In the end, the theoretical model of depicting how student teachers cope with challenges was seen as a set of strategies. In the process, being attentive to data, initial codes, and focused codes also included staying open to new possibilities. The first model here used to exemplify had several challenges, not uncommon among qualitative methods. For example, the iterative figure was concluded to have a logical gap that concluded that an avoidance strategy would lead to cooperation with future colleagues. Nonetheless, there was evidence in the data and in the codes that student teachers used coping strategies that could be characterized as avoidance, and they talked of relying on future colleagues. Even so, this model failed in depicting these relations between these codes in a way that was evidently grounded in the data. Another example of how the model failed to exemplify the process is that it starts with a theoretical assumption that was not grounded in the data, and that is that the act of appraisal leads to the use of a coping strategy. This was not in the material and could not be said to be grounded in the data and was therefore refuted as an alternative. Therefore, the process started over, focusing on strategies as a theoretical code. In the end, the strategies concluded were change advocacy, collective sharing, and responsibility assessment. All these strategies were grounded in the data and all involved a strategy to resolve the main concern of the student teachers. This exemplifies theoretical pluralism and theoretical agnosticism; as researchers we try to stay open to our material. When assuming that a researcher forces a theory on their analyses, the researcher is discredited by not having the ability to avoid forcing theories upon the data or to recognize links between data and theories (Thornberg Citation2012).

We consider theoretical coding to be a strength, and an argument for furthering the use of CGT in research of teachers’ work. In other qualitative methods, the relation among themes, the variation of experiences, or exploring participants’ experiences often end with describing the results as categories and themes. After that, extant theories are used to further enhance the understanding, but CGT brings a clear focus of exploring the relations among the categories or themes, and trying out different theoretical lenses that fit with the data. The theoretical codes can be used in combination, and Thornberg and Charmaz (Citation2012) argue that:

By possessing a broad repertoire of theoretical codes, researchers can view their data and categories from as many different relevant theoretical perspectives as they can envision in order to explore and evaluate the usefulness of a lot of theoretical codes for relating, organizing, and integrating the categories and codes into a grounded theory. (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2012, 53)

Having a broad repertoire of theoretical perspectives could also involve new theoretical insights, using a theoretical pluralistic approach (Thornberg Citation2012), or with an informed guessing approach (Chew Citation2020) to abductively explore new innovative ideas and insights. Here, the critique of grounded theory mainly producing everyday theories and without adding anything new into the understanding (due to the naïve inductive stance attributed to grounded theory; Thomas and James Citation2006) falls short. This means that studies could make use of theoretical perspectives that are otherwise unusual, but fit with the data, to not let important contributions be lost as a consequence of postponing reading literature (Thornberg Citation2012). Thus, when recognizing the relationship among codes, this could also be in relation to extant theories that work and fit with the analysis and constructed theory.

Extant theories could be used to enhance the analysis and are sometimes used because of their fit to the data (Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2012, Citation2014). For example, Lindqvist et al. (Citation2019) used a micropolitical perspective to explore the coping of beginning teachers. The micropolitical perspective was not adopted beforehand to be a possible lens for understanding the process and actions of beginning teachers. Instead, the micropolitical perspective earned its way into the analysis late in the process. This enhanced the conceptualizing of the analysis, helped describe some of the challenges beginning teachers experienced, and offered a way to build a grounded theory. This was a product of staying open to the data, using theories of possible lenses, being agnostic to theories, and trying new theories in a playful manner.

Conclusion

CGT is not a superior method, but we argue it could add value in research of classrooms and teachers’ work, especially because of the uncommon use of CGT in classroom research of teachers’ work, but mostly because it offers a theory–method package that we find particularly useful when wanting to explore social processes in the classroom. CGT involves using an open, exploratory approach (Dey Citation1993) in order to focus on participants’ perspectives or main concern(s) (Charmaz Citation2014), and CGT could involve investigating the relationships among and between the focused codes, preferably by using theoretical coding (Charmaz Citation2014, Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014). Here, these concrete benefits help researchers, practising teachers, and leaders in schools to develop an understanding of teachers’ and student teachers’ perspectives on teachers’ work. In the text we argue that (1) CGT focuses on participants’ perspectives, or main concern, (2) by using an open, exploratory approach, and, (3) could involve investigating the relationships between the focused codes, preferably by using theoretical coding. We suggest that in order to further develop the relations among codes, and to develop CGT, the phase of theoretical coding could be practised more, since the theoretical code families are useful in order to construct working theories (Glaser Citation1978, Charmaz Citation2014, Thornberg and Charmaz Citation2014). This is a concrete and distinct feature that can be utilized in CGT, and sets the method apart from other qualitative methods.

In educational research using grounded theory, the flexible usage of grounded theory methods is commonly described (cf. Bell et al. Citation2018, Holloway Citation2021). CGT is also commonly used to describe how the researcher influenced the data collection and is part of the interpretative actions of studies (Holloway Citation2021). However, it is more uncommon in published CGT studies that the relation to the participants’ perspective and main concern(s), or the theoretical coding process, is described. Hence, we would suggest that also focusing on developing the relationships among codes and relating this to a main concern could involve adding an interpretative layer to CGT that is not particularly visible to date within educational research. Furthermore, staying informed within the field is essential so as not to lose possible connections, or replicate what we already know (Thornberg Citation2012). We would suggest that the pragmatist connection of CGT (Charmaz Citation2017) also serves well in constructing working descriptions and actionable knowledge. To be able to accomplish this, researchers need to stay close to the perspectives of the participants, as could also be argued from the study by) McChesney and Aldridge (Citation2019), in order for teachers to feel the relevance of the constructed theories. This is a salient point of departure for CGT to come, in order to increase the relevance, and bridge the theory and practice gap of educational research. We need to critically scrutinize how the grounded theories developed can be used in practice and feel relevant for the people that should use them. Here CGT could make use of the pragmatist theoretical base, and

we need to stay open to a theory that might be open for changes, to know if it is a theory that ‘works’.

Implications for educational researchers

For research to impact on teachers’ work, we need to know more about teachers’ work from the perspectives of teachers, not least their main concerns. Today, there is a lack of CGT studies of classroom actions. If we could be precise in constructing working theories, this would mean we could assist teachers to resolve their main concerns, and establish theories to test in larger studies, or further distinguish through theoretical sampling (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967). We therefore suggest that qualitative educational research using a CGT approach could be applied to a greater extent when investigating teachers’ work in classrooms, or in relation to teachers’ leadership or teaching of different subjects. In order for this to be a reality, we wish to invite scholars and educational researchers not only to CGT as an open toolbox to choose from (even though this is also welcome). We wish scholars to also consider CGT as a way of developing theories, by investigating the relations among codes and categories. We wish to further build the grounded theory methodology as a viable and accessible choice in order to develop educational research in new, innovative ways.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bell, D., et al., 2018. STEM Education in the Twenty-first Century: Learning at Work—an Exploration of Design and Technology Teacher Perceptions and Practices. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 28 (3), 721–737. doi:10.1007/s10798-017-9414-3.

- Blumer, H., 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Bryant, A., 2019. The Varieties of Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Charmaz, K., 2011. A Constructivist Grounded Theory Analysis of Losing and Regaining a Valued Self, edited by FJ Wertz, K Charmaz, LM McMullen, R Josselson, R Anderson, and E McSpadden, eds. Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry, 165–204. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Charmaz, K., 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Charmaz, K., 2017. The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23, 34–45. doi:10.1177/1077800416657105.

- Charmaz, K., Harris, S.R., and Irvine, L., 2019. The Social Self and Everyday Life: Understanding the World Through Symbolic Interactionism. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Charon, J.M., 2006. Symbolic Interactionism: An Introduction, an Interpretation, and Integration. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Chew, A.W., 2020. Informed Guessing: Enacting Abductively-Driven Research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 43, 189–200. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2019.1626818.

- Clarke, E., and Visser, J., 2019. Pragmatic Research Methodology in Education: Possibilities and Pitfalls. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 42, 455–469. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2018.1524866.

- Dey, I., 1993. Qualitative Data Analysis. London: Routledge.

- Forsberg, C. 2016. Students’ perspectives on bullying. PhD diss. Linköping University.

- Forsberg, C., Thornberg, R., and Samuelsson, M., 2014. Bystanders to Bullying: Fourth-to Seventh-grade Students’ Perspectives on Their Reactions. Research Papers in Education, 29 (5), 557–576. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2013.878375.

- Glaser, B.G., 1978. Theoretical Sensitivity: Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B.G., 1998. Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B.G., 2003. The Grounded Theory Perspective II: Description’ s Remodelling of Grounded Theory Methodology. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B.G., and Strauss, A.L., 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Hallberg, L.R., 2006. The “Core Category” of Grounded Theory: Making Constant Comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 1, 141–148. doi:10.1080/17482620600858399.

- Holloway, S.M., 2021. The Multiliteracies Project: Preservice and Inservice Teachers Learning by Design in Diverse Content Areas. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 16 (3), 307–325. doi:10.1080/1554480X.2020.1787172.

- Lindqvist, H., et al., 2017. Resolving Feelings of Professional Inadequacy: Student Teachers’ Coping with Distressful Situations. Teaching and Teacher Education, 64, 270–279. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2017.02.019.

- Lindqvist, H. 2019a. Student teachers’ and beginning teachers’ coping with emotionally challenging situations. PhD diss. Linköping University.

- Lindqvist, H., 2019b. Student Teachers’ Use of Strategies to Cope with Emotionally Challenging Situations in Teacher Education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 45, 540–552. doi:10.1080/02607476.2019.1674565.

- Lindqvist, H., et al., 2019. Conflicts Viewed Through the Micro-political Lens: Beginning Teachers’ Coping Strategies for Emotionally Challenging Situations. Research Papers in Education, 35, 46–765. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1633559.

- McChesney, K., and Aldridge, J.M., 2019. What Gets in the Way? A New Conceptual Model for the Trajectory from Teacher Professional Development to Impact. Professional Development in Education, 47(5), 834–852. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1667412.

- Striepe, M., 2020. Combining Concept Mapping with Semi-structured Interviews: Adding Another Dimension to the Research Process. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 44(5), 519–532. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2020.1841746.

- Taber, K.S., and Student, T.A., 2003. How was it for you?: The Dialogue Between Researcher and Colearner. Westminster Studies in Education, 26, 33–44. doi:10.1080/0140672030260104.

- Thomas, G., and James, D., 2006. Reinventing Grounded Theory: Some Questions About Theory, Ground and Discovery. British Educational Research Journal, 32, 767–795. doi:10.1080/01411920600989412.

- Thomas, W.I., and Thomas, D.S., 1928. The Child in America. New York, NY: Alfred A.

- Thornberg, R., 2012. Informed Grounded Theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56, 243–259. doi:10.1080/00313831.2011.581686.

- Thornberg, R., 2017. Grounded Theory. In: D. Wyse, N. Selwyn, E. Smith, and L. E Suter, eds. The BERA/SAGE Handbook of Educational Research, Vol. 1. London: Sage, 355–375.

- Thornberg, R., and Charmaz, K., 2012. “Grounded Theory”. In: S. D. Lapan, M. Quartaroli, and F. Reimer, eds. Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods and Designs. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley/Jossey-Bass, 41–67.

- Thornberg, R., and Charmaz, K., 2014. Grounded Theory and Theoretical Coding. In: U. Flick, ed. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage, 153–169.