ABSTRACT

Few studies have examined the impact of resilience training on youth in lower/middle income countries (LMICs). This study assessed feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of GROW, a 24-week character-based resilience curriculum rooted in positive psychology and spirituality and taught via storytelling. Our pilot design – a mixed method, cluster-randomized controlled trial – was conducted with 28 classes of 643 Zambian youth ages 10–13 (M = 11.39, SD = 0.95, 55.4% female). Classes were divided into initial-start and delayed-start intervention phases. In 17 focus groups, parents, teachers, GROW leaders, and children affirmed the program’s excellent cultural fit. Adult stakeholders observed positive impacts on school attendance, academic performance, and students’ character and behavior. Initial-start students showed a pre-post increase in psychological resilience (p < .05). Together, these findings suggest GROW has promise for improving early adolescents’ positive development. This strengthens the evidence base for the potential impact of culturally appropriate, spiritually-oriented programs delivered by lay providers for LMIC youth.

Introduction

Character strengths correlate with well-being, positive relationships, health, and resilience (Niemiec, Citation2019; Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004). Training in character strengths is theorized to contribute to resilience by aligning decision-making with core values, helping reinterpret problems in constructive ways, and supporting bounce-back from life’s setbacks (Niemiec, Citation2020). Positive psychology interventions with adolescents have been mainly focused in literate Western populations (e.g. Reivich et al., Citation2005; Seligman et al., Citation2009), yet 90% of all adolescents live in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Resilience training interventions in such settings are few (Kieling et al., Citation2011) and often limited in scope (Adler et al., Citation2016; Leventhal et al., Citation2015). Recent systematic reviews of youth development and mental health programs in LMICs (Barry et al., Citation2013; Catalano et al., Citation2019) identified several programs with positive effects on students’ self-esteem, motivation and self-efficacy, but only one documented increased resilience (Leventhal et al., Citation2015). Evaluation of programs in these settings is challenging, necessitating testing and modification of traditional outcome measures (Panter-Brick et al., Citation2020; Van Ommeren, Citation2003) and generating recommendations that future studies include objective measures that go beyond self-report (Leventhal et al., Citation2015).

Potential exists to integrate novel evidence-based resilience training components into after-school youth programs. Traditionally, positive psychology interventions have been secular in nature, yet spirituality is associated with greater well-being, life meaning, and resilience (Barton & Miller, Citation2015; Southwick & Charney, Citation2012) and plays an important role in many cultures around the world. Major spiritual development occurs during adolescence (Good & Willoughby, Citation2008), making this a potentially important time for spiritually based interventions. Spirituality is believed to enhance resilience through development of attachment relationships, creation of sources of social support, guiding conduct and moral values, and/or exposing participants to a range of character strengths (Crawford et al., Citation2006). Masten (Citation2004) suggests that ‘a sense that a divine power can work through one’s prayers or prayers of others adds a unique element of comfort [and] can provide a sense of protection and hope in otherwise helpless environments.’

Similarly, storytelling has been found to contribute to psychological resilience (East et al., Citation2010). It is a safe, non-threatening approach to learning and is believed to impact resilience by offering insights into how others have overcome adversity. Listening to stories about others encourages self-reflection as one learns how to incorporate these insights to enhance one’s own personal experiences. Storytelling reframes adversity as a normal part of the human experience that contributes to a sense of purpose and meaning (East et al., Citation2010; Nguyen et al., Citation2015).

Global Resilience Oral Workshops (GROW), is a reproducible, culturally adaptable, spiritually based character strengths resilience program that is taught through storytelling. It was created as a capstone project at the University of Pennsylvania (Seale, Citation2014). Field studies were conducted in the U.S., Uganda, and South Africa from 2014–2017, with positive anecdotal results. A request for adolescent resilience training from Expanded Church Response (ECR), a Zambian non-governmental organization, provided the opportunity to conduct an evaluation of GROW in an LMIC setting. Zambian culture lends itself well to a spiritually oriented intervention. Zambia’s constitution establishes it as a Christian nation that guarantees religious freedom for all. Religious education is taught in all Zambian schools and, in recent years, has included a greater emphasis on teaching values (Carmody, Citation2003; Simuchimba et al., Citation2019).

The population of Zambia is predominantly Christian (96%) and skewed in age, with 46% of the population under the age of 15. Nearly half (45.4%) of children live in extreme poverty (UNICEF, Citation2020). A mixed-methods evaluation approach was designed to capture program impacts. Herein we report quantitative and qualitative findings from a pilot cluster-randomized controlled trial evaluating feasibility, acceptability, and effects of GROW Zambia on youth character strengths and psychological resilience.

Materials and methods

Study design

GROW Zambia was conducted through a two-year partnership between investigators based in the United States, Ireland, and Zambia. The study utilized a pre-/post-test cluster-randomized, waitlist-control group design with clusters of Zambian schools located in Lusaka. Study assessments were conducted at three time points: baseline [Time 1], after the initial group completed the curriculum [Time 2], and after the delayed group completed the curriculum [Time 3]) (). This trial was registered with the Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (PACTR202009845194666).

Participants and recruitment in Lusaka

School administrators and representatives from 30 communities in the ECR network were invited to an information session that explained the concept of resilience, the value of character training, the curriculum and the rationale for utilizing a spiritual foundation to promote positive adolescent development. Schools were eligible if they had at least 25 children ages 11–12 in grades 5–6 who were able to read and write in English, an after-school space which could accommodate a ninety-minute GROW class, and one teacher who could participate as co-leader. The decision to teach and evaluate GROW in English was made jointly by researchers and ECR leadership. While at least 73 languages are spoken across Zambia, English is the formal language of education. In Lusaka, students learn to read and write in English beginning in Grade 4, though teachers may use one of the seven official Zambian languages to explain concepts that do not translate well in English (Nkolola-Wakumel & Simwinga, Citation2008). GROW was taught in English, with concepts explained in Zambian languages as needed, and students completed questionnaire evaluations and simple goal-setting exercises in English. In some participating schools, most students in Grades 5 and 6 met English fluency criteria, while in other schools the percentage of eligible students was lower. Twenty-three schools elected to participate, including one private school, two government schools, and 20 community schools (schools created for students who were financially unable to attend public schools). Two schools dropped out before GROW classes started. One school could not find a teacher to volunteer to be trained for GROW, and the other determined that their afternoons were already overloaded with other extracurricular activities.

Parents of eligible students were invited to information sessions at each school which explained the specifics of the curriculum. Recruitment forms, program flyers and consent forms welcomed all parents and students to participate, regardless of religious background and described GROW as a 24-week ‘after-school character building program that uses Bible stories to teach pathways to greater resilience.’ The GROW program was taught through weekly 90-minute sessions that included storytelling, drama, prayer, snacks, creative activities, and games. Information sessions and consent/assent forms collected from each parent or care provider and each student before beginning the program repeatedly reassured participants that all GROW exercises were voluntary, and that students were free to refuse to participate in any activities that made them uncomfortable and free to withdraw from the program at any point. No monetary incentive was provided. Participating students were grouped into 28 classes of 20–24 students each. Seven larger schools had multiple classes (six schools had two classes, and one school had three classes). Classes were stratified by type of school (government vs. other) and, using a web-based computerized randomization program, randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to either an initial-start (Phase 1 GROW implementation) or delayed-start (Phase 2 GROW implementation) arm (see CONSORT flow diagram, ). Study procedures were approved by human ethics boards in Zambia (ERES Converge, Ref. 2018-Mar-026) and the U.S. (Boston Children’s Hospital, Protocol P00026996).

After 85 students in the delayed-start group were lost to follow-up prior to beginning Phase 2 GROW classes, ECR recruited 98 additional students who met eligibility criteria, allowing as many children as possible to access the program ().

Curriculum

GROW is a novel 24-week resilience curriculum rooted in positive psychology. Instruction centers around 24 character strengths, which were identified through a study of worldwide cultures and religious traditions (Peterson & Seligman, Citation2004), then field-tested and found to have widespread cultural relevance (Biswas-Diener, Citation2006). GROW teaches these character strengths using a broad base of archetypal Bible stories. The teachers and students read the Bible stories, students act them out, and the class discusses the stories in an open-ended fashion focusing on the value of the character strengths, such as honesty, bravery, forgiveness, or perseverance. Content is taught through local music, cultural dance, drama, art, goal setting, meditation, games, and other interactive exercises.

Each GROW club was led by two trained leaders (usually one female and one male) who addressed one character strength per session using 15 evidence-based activities (see for activity list and Table S1 for evidence base). Leaders were given a printed copy of the curriculum, a laminated copy of the Lesson Plan Training Card, 2 flip charts, markers paper and crayons. At the request of the GROW leaders, a notebook in which students could record weekly personal goals was created and given to those in Phase 2.

Table 1. GROW curriculum components, with rankings of importance by students and GROW leaders.

Cultural adaptation: The final GROW Zambia curriculum was drafted after extensive discussion of project components by investigators and ECR’s Zambian cultural informants, a three-week pilot project in a community school, and a final analysis of project components with the on-site implementation team. Modifications resulting from this process included adding a program motto, ‘Never give up, never surrender!’; integration of the ‘kilo,’ a local method for demonstrating active constructive response for something positive by applauding three times and blowing a kiss; shortening of weekly Bible verses; adding an object lesson to demonstrate resilience (submerging a soccer ball in a bucket of water, then releasing it to watch it bounce back); and creating a leaders’ WhatsApp list for communication and networking. The proposed assessment was shortened by 50% to make implementation more feasible for students and teachers.

Additional modifications were made after completing Phase 1. In response to requests from students and school administrators to lengthen the program, and in light of a review of research indicating that effective youth mentoring relationships require at least 12 months of ongoing contact (Grossman & Rhodes, Citation2002; Rhodes & DuBois, Citation2008), a ‘GROW WINGS’ curriculum component was added to extend student-leader mentoring for Phase 1 students for an additional six months (Table S2). GROW WINGS goals included monthly meetings, student leadership opportunities to volunteer in Phase 2 clubs, and ongoing participation in service projects. GROW graduates received T-shirts and GROW Wings participants received badges to increase program identification. Graduation events were held after each intervention phase and a sports event tournament involving students from all GROW groups was held after Phase 2.

Leader selection, training, and supervision: Forty-five GROW leader candidates were recruited from the program’s target communities. Community health program officers from ECR were asked to nominate individuals of high moral character with teaching experience, a love for children, no history of sexual impropriety, three character references, a high school education, and who felt comfortable leading children in prayer. Most candidates were teachers, pastors, and community care providers. Candidates attended a two-day interactive GROW training workshop that included practice teaching exercises, after which 30 GROW group leaders were chosen. Leaders were paired with a partner of the opposite gender and assigned to specific schools. Leaders attended weekly two-hour training sessions prior to teaching each week’s lesson, plus one-day booster trainings between Phase 1 and Phase 2 and at the midpoint of each intervention phase. Additional coaching and training were provided through a WhatsApp text list. Leaders received cell phones to facilitate communication and audio recording of classes, plus a modest monthly allowance for transportation and cell phone data usage. Fidelity was monitored through uploading of weekly audio recordings and frequent drop-in visits by the trainer/coaches. One co-leader completed and submitted a checklist of all GROW steps completed after each weekly session. Leaders were also asked to post pictures and videos of their group activities each week on the WhatsApp list.

Measures and data collection

Evaluation of program feasibility, perceived acceptability and impact, and pilot efficacy for primary and secondary character strength outcomes utilized a mixed-methods assessment approach.

Program feasibility: We evaluated program feasibility by examining students’ class attendance rates and GROW leaders’ attendance at weekly trainings. GROW leaders recorded student attendance at GROW classes. ECR staff recorded GROW leader attendance at weekly meetings.

Feasibility of GROW WINGS was assessed by adding questions about participation in GROW WINGS activities to the final student questionnaire at the end of Phase 2.

Perceived acceptability and impact: We assessed perceptions about, and experiences with, the GROW program by conducting focus group (FG) discussions with individuals (6–8 participants per FG) representing four key stakeholder groups: parents (3 groups, n = 24 participants), school staff (headmasters and teachers) (5 groups, n = 31), GROW leaders (3 groups, n = 24) and students (6 groups, n = 40). ECR asked school officials to send one teacher or administrator who had significant contact with GROW students and up to four students who were able to express themselves in English to participate in FGs at ECR headquarters. A convenience sample of parents of GROW students who attended each of the two GROW graduation ceremonies were invited to participate in a FG while their children completed the study questionnaire in a separate room. Trained Zambian facilitators not affiliated with the GROW program conducted one parent FG in Nyanja, the most common local language, and the remaining FGs in English. GROW leader FGs were conducted during a booster training session between Phase 1 and 2. GROW students from 11 schools (~4 students per school) participated in FGs. All FGs were semi-structured and included discussions of the cultural fit of the GROW program, its positive aspects, challenges, areas for improvement, most and least preferred program features, and the impact of GROW on participants. To identify the most or least preferred program features, student and GROW leader FG participants completed a worksheet in which they individually ranked their favorite GROW activities (for students), or those felt to be most useful (by GROW leaders).

Participants were informed that discussions would be audio-recorded and that no information provided would be linked to an individual. Each FG lasted 60–75 minutes. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the non-English focus group discussion was translated.

Pilot efficacy: All student participants completed a paper questionnaire at baseline (July 2018), completion of Time 2 (February 2019), and completion of Time 3 (November 2019). Questionnaires were administered in school classrooms by trained ECR Monitoring and Evaluation team members who read each question and its response choices aloud and, if needed, explained the meaning of questionnaire items in English or Nyanja in response to student queries. Questionnaires were labelled with a unique student alphanumeric ID rather than names to ensure student confidentiality.

Our primary outcome measure was the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), a measure of psychological resilience (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). Items include ‘I am able to adapt when changes occur,’ ‘I tend to bounce back after illness, injury or other hardships,’ and ‘Under pressure, I stay focused and think clearly.’ Responses range from ‘not true at all’ (0) to ‘true nearly all the time’ (4); higher scores indicate greater psychological resilience. The scale showed good reliability in this sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.81).

The following secondary outcomes were assessed: hope (Children’s Hope Scale, Snyder et al., Citation1997, α = 0.69), meaning in life (Meaning in Life Questionnaire, Steger et al., Citation2006), grit (Grit-S Questionnaire, Duckworth & Quinn, Citation2009, α = 0.75), gratitude (Gratitude Questionnaire 6, McCullough et al., Citation2002, α = 0.58), gratitude to God (Krause et al., Citation2014, α = 0.83), spirituality (Daily Spiritual Experiences, Underwood & Teresi, Citation2002, α = 0.75), and forgiveness (Harris et al., Citation2008, α = 0.54). Given that we hypothesized that a mechanism of program effect would occur through increased connection to a caring adult, we also assessed students’ feeling of connectedness to their GROW leader at Times 2 and 3 (after students had worked with their GROW leaders), using an adapted version of the Youth Connectedness to Provider scale (Harris et al., Citation2009, α = 0.65), consisting of 8 items with a response scale of 0 = Not at all, 1 = A little, 2 = Somewhat, 3 = Quite a bit, and 4 = Very much.

While these measures have been validated for use with youth in the U.S. and elsewhere (e.g. Harris et al., Citation2008), they have not been validated among Zambian youth. In addition, with English being a second language, and some participants being as young as 10-years-old, some students may have found it challenging to fully understand all of the concepts – particularly those that assess more abstract concepts, such as spirituality. For these reasons, we are concerned about the reliability and validity of these measures in our sample; results related to these measures should be viewed with caution.

Sample size

We calculated that a total of 540 students would be needed to detect a difference between groups in our primary outcome measure, psychological resilience, at a power of 0.80, assuming three measurements, an effect size of 0.30, and a variability of the levels of 0.40. Recruitment of 600 participants at baseline would allow for an attrition rate of about ~10% across the three waves.

Data analyses

Qualitative data: A content analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) of each FG discussion was carried out in which data were inductively analysed by two investigators individually, then together. Using an iterative process, statements considered to represent the same concept were clustered together on a spreadsheet and assigned codes, then related codes were clustered to identify major themes. Codes and themes were modified and refined until the most ‘reasonable’ reconstruction of the data had been developed (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). Differences of opinion regarding coding were resolved by discussion and consensus. Data tables were prepared to communicate themes that emerged, along with representative quotes.

Quantitative data: All statistical analyses compared intent-to-treat groups, and accounted for the longitudinal and cluster-sampling study design, with data nested within students and schools. Analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 26. We were unable to correctly link all questionnaires across time points due to errors in ID assignment for some students at baseline ( shows the numbers of questionnaires linked across time points). We conducted generalized linear mixed effects modelling to compare character strength measures between study arms across time. Mixed effects modelling uses all available data, allowing for retention of all participants in analyses, even when there are missing data at some time points (Diggle et al., Citation2002). All models controlled for child age, grade, sex, type of school (government school vs. other), and the single variable that differed between groups at baseline, number of meals per day (dichotomized as ≤2 vs. 3+).

Results

Sample characteristics

displays recruitment and retention of schools and students at key study time points. After 30 classes from the 23 initially recruited schools were randomly assigned to the two study arms, two schools withdrew, as previously noted. Both withdrawn schools had been assigned to the delayed-start group, leaving 13 classes in the delayed group and 15 in the initial group. Of the 687 students enrolled in the study, 643 (88.6%) (343 in initial group [median cluster size (MCS) = 23], 300 in delayed group [MCS = 24]) completed baseline questionnaires. Average age was 11.4 years old (SD = 0.9 years), 55.4% were female, 68.0% lived with two parents/caregivers, 38.6% lived in <3-room homes, and 12.5% had ≤2 meals/day. Although groups were allocated randomly, the delayed group had a significantly higher proportion reporting eating ≤2 meals/day (15.7% vs. 9.6%, p = .020) ().

Table 2. Sample sociodemographic characteristics across all data collection time points.

Program feasibility and fidelity

GROW class attendance: The percent of enrolled students at baseline who attended at least one GROW session was 90.4% for the initial group and 71.3% for the delayed group (p < 0.001), representing an attrition rate prior to initiation of classes of 9.3% for the initial-start group and 28.7% for the delayed-start group. Of students attending at least one GROW class, the overall median number of classes attended was 23 of 24 (IQR = 20–24) for both initial and delayed groups. Overall, 78.5% of students who attended at least one class completed ≥20 of 24 classes, with no significant difference between groups.

Attendance levels varied widely across schools, with the school median number of classes attended ranging from 16 to 24 (mean of the medians = 22.2, SD of mean = 1.6). Percentages attending at least 20 classes ranged from 19% to 100% across schools/classes, with a mean of 79% (SD = 16.4).

GROW WINGS involvement: GROW WINGS was successful in engaging students in GROW relationships and activities during Phase 2: 92.1% of students reported some involvement and more than half participated three or more times (Table S2). Most common activities were helping in another GROW class, participating in a GROW WINGS meeting at school, and helping lead a GROW assembly or lesson. Students reported continuing GROW practices learned in Phase 1, especially forgiving others, enjoying learning new things, praying more often, and reflecting on what they were grateful for each day. Ongoing habits practiced at least weekly included looking forward to the future, saying ‘no’ to temptation, and setting personal goals. Ongoing positive engagement with others included complimenting others when they did a good job and brainstorming together to solve a problem.

GROW leader weekly training attendance: Average attendance at weekly training sessions was 95.3% (28.6/30 leaders) in Phase 1 and 80.0% (22.4/28) in Phase 2.

Program fidelity. Periodic review of checklists of GROW steps completed in each student session by GROW leaders, as well as leader performance during drop-in supervision visits, showed high adherence to GROW program protocols.

Perceived acceptability and impact

Cultural fit: Adults in all FGs affirmed GROW’s strong cultural fit, with four administrators from two FGs independently referring to it as ‘100% fitting.’ Participants repeatedly mentioned that GROW ‘conforms to cultural norms and Christian values’ and reinforces the values that parents teach at home. Some parents had enrolled their children because of their desire that their children learn more about the Bible. All adult FG participants asked for the continuation of the GROW program, suggesting that it be taught to all students (both younger and older), expanded to schools across Zambia, taught to adults (especially parents) and to out-of-school youth.

Impact of GROW participation: The following are the major themes derived from the FGs, organized under key topics (see Table S3 for quotations):

Positive changes others observed in the students: Adult FG participants indicated that GROW students were more confident and resilient, speaking out more in class, showing initiative, and leading others. They observed students teaching GROW lessons to students in school and family members at home. School staff often described improved student behavior, attendance, and academic performance. Parents also noted improved school attendance and most often mentioned that participating youth demonstrated greater respect towards adults. Other changes in students noted by school staff and parents included greater honesty and self-control, less fighting, more kindness toward others, showing civic responsibility by voluntarily cleaning up classrooms and schoolyards, and serving as role models for other youth.

Positive changes noted by students themselves: Students reported being excited and energized by GROW participation, with several students remarking, ‘GROW changed my life!’ They described instances of practicing GROW character strengths and teaching them to other students and family members, including parents. Students described practicing goal-setting as they identified future career goals such as becoming a doctor, lawyer, soldier, or aircraft mechanic, and defined shorter term goals such as passing their exams, refusing alcohol and tobacco, and finishing their schooling to help reach long-term goals. They noted how character strengths such as perseverance, love of learning, and fairness supported their ability to fulfil their life goals. When asked to identify their favorite character strengths, they mentioned all 24, with perseverance, honesty, self-control, forgiveness, and leadership being most commonly mentioned (Table S4).

Preferred program features: Students’ rankings of their favorite GROW activities are displayed in alongside GROW leaders’ rankings of their assessment of the program’s most important components. Activities ranked among the top 7 for both students and GROW leaders were: listening to and acting out the Bible stories, reciting the personal spiritual affirmation, practicing forgiveness, and participating in the group gratitude prayers. Lowest ranked components included measuring themselves in relation to the character strength of the week, memorizing the character strength definition, Bible verse, and principle, and doing daily homework.

Positive impact of spirituality interventions: The spiritual impact of the program was a frequent theme across all the FGs. Students talked about actively engaging in meditation, learning the Bible, and learning about God. Adults observed that GROW students increased their church attendance and demonstrated leadership at church. They learned and increased their love of the Bible, and taught that love to others. They also made prayer a more regular part of their life, and deepened their relationships with God.

Positive changes in leaders: GROW leaders indicated positive changes for themselves as well. As they taught students traits such as forgiveness and honesty, they became more diligent in practicing these in their own lives. They practiced goal setting and perseverance and became more confident in public speaking. They reported feeling energized by positive feedback from parents and felt closer to God. Some developed deep bonds of affection with their students, describing students running and hugging them when they reached the schoolyard, visiting them, and helping them with chores in their homes. One came to feel that expressing love to her students, who at times received little love at home, was a part of her role as a teacher that she had not previously embraced.

Challenges/suggested changes: One of the challenges of GROW was the selection of students whose English fluency and reading proficiency was advanced enough to take the questionnaire. This caused some students to feel excluded. Offering GROW to certain students and not others was considered unfair. The primary suggested change was widespread expansion of the program.

Pilot efficacy

Follow-up questionnaire completion: Among students with baseline questionnaires, 79.8% completed questionnaires at Time 2, with retention in the initial-start group (87.2%) significantly higher compared to the delayed-start group (71.3%) (2 = 7.20, p = 0.007) (). Of the 611 Time 2 questionnaires collected, 441 (251 in initial group, 190 in delayed group) were matched by student ID to baseline questionnaires. At Time 2, compared to participants without matched Time 1 and 2 questionnaires, those with matched questionnaires were more likely to be girls (73.0% vs. 63.2%, χ2 = 7.04, p = 0.008), report 3+ meals per day (70.0% vs. 58.8%, χ2 = 4.10, p = 0.043), and attend non-government schools (71.3% vs. 52.2%, χ2 = 13.4, p < 0.001). There were no differences in character strengths measures. We are not able to report an overall sample retention rate for Time 3 due to the addition of new students to the delayed group at Time 2. Time 3 retention in the initial-start group was 70.3% relative to baseline (241/343), and 80.6% relative to Time 2 (241/299); for the delayed group, it was 88.8% relative to Time 2.

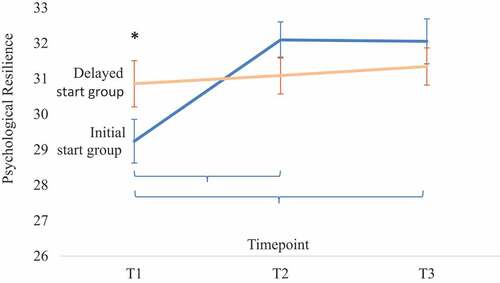

Psychological resilience: There was a significant difference between study arms in baseline CD-RISC scores, with lower scores in the initial-start group (). There was a significant increase in psychological resilience from Time 1 to 2 in the initial-start group, but not in the delayed-start group (, ). Higher psychological resilience was sustained in the initial-start group to Time 3. There was no change in psychological resilience in the delayed-start group pre- to post-intervention (between Times 2 and 3).

Table 3. Psychological resilience measures: Results from mixed effects modelling comparing the initial start and delayed start groups across three time points.

Figure 2. Changes in psychological resilience.

Secondary outcomes: The results of mixed-effects modelling of the program effect on our secondary outcomes are presented in Tables S5 and S6. There were few significant effects found for the secondary outcomes. While hope scores were similar between groups at baseline, there was a marginally significant increase in hope scores in the initial-start group (p = 0.07), resulting in a higher mean hope score in the initial-start compared to the delayed-start group at Time 2 (p < 0.01). Thereafter, hope scores changed little between Times 2 and 3 in either group.

Unexpectedly, we found significant declines in scores for the Meaning in Life and Daily Spiritual Experiences measures between Times 1 and 2 in the initial-start group (both p < 0.01); no such differences were found in the delayed-start group. We found no other Time 1 to 2 differences in the secondary outcome measures for either group. Between Times 2 and 3, there were no significant differences in secondary outcome measures for the delayed-start group. There were increases in Meaning, Gratitude, and Gratitude to God scores between Times 2 and 3 in the initial-start group.

Connectedness to GROW teacher: After each GROW phase, students’ connectedness to their GROW teachers was high. Because the data distribution for youth connectedness scores was highly skewed, we present medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Students in both groups had a median score of 28 (IQR 28–32; maximum possible score 32).

Discussion

This study adds to the growing evidence that positive psychology-based interventions can increase psychological resilience and positive outcomes among youth in LMICs. Collective data from the FGs suggests positive impacts in multiple areas of children’s lives. This is mirrored by quantitative data indicating increased psychological resilience in the initial start group which was sustained over time. This mixed-methods, multi-informant evaluation provides rich data allowing for triangulation across outcomes (Tirrell et al., Citation2020). Our results suggest that this low-cost intervention – delivered by lay providers – has significant potential for scalability; indeed, FG participants affirmed GROW’S high cultural acceptability and called for program expansion throughout Zambia. Since GROW ended, 35 additional groups have been started by GROW leaders without outside funding, primarily within leaders’ churches or local neighborhoods to limit transportation costs.

One confusing finding was a lack of change in psychological resilience in the delayed start group, in contrast with increase resilience noted in the initial start group. While it is possible that the positive finding in the initial start group is spurious and no intervention effect occurred, resilience may have increased in this group due to their younger age, their lower baseline scores, and/or greater enthusiasm related to the launch of the program. It is also possible that several factors may have negatively impacted the delayed start group. The delayed group had a significantly higher proportion reporting eating ≤2 meals/day (15.7% vs. 9.6%, p = .020) (). Though each GROW session included a snack, greater levels of poverty and hunger could have limited some students’ capacity to concentrate and profit from the program. Cross contamination of the control group during Phase 1 could have occurred, as seven of 13 delayed start classes were in schools that also had initial start GROW groups. Age difference may have contributed: Phase 2 students were seven months older on average. Leaders’ attendance at coaching sessions was lower during this phase, leader fatigue may have occurred, and six of 24 leaders were reassigned due to health and personal reasons. Students who were enrolled prior to baseline data collection may have lost interest and enthusiasm after waiting nine months for their groups to begin, as reflected by the 28.3% dropout rate of delayed intervention students before their GROW classes began.

Inconsistent quantitative findings contrast with the consistent positive findings of the qualitative data from all four stakeholder groups of FG participants (GROW leaders, school officials, parents and students) in both intervention phases. Both social desirability bias and selection bias of students may have impacted these results. School officials selected student participants based on English proficiency, and students with higher English proficiency may have grasped GROW concepts more readily and benefited more from participation. However, parent FGs were conducted in both English and Nyanja, and both reported similar positive changes in attitudes and behaviors of students. It is also notable that the call for widespread expansion of the program to other age groups and schools was virtually universal.

Previous research suggests possible reasons for this program’s success among initial start students. Participating youth likely benefited from the ‘big three’ components of effective youth development programs: positive sustained adult-youth relationships of at least 12 months’ duration, life-skill-building activities, and opportunities for youth contribution and leadership (Lerner, Citation2004). Similarly, the intervention integrated eight of nine components shown by Southwick et al. (Citation2015) to have strong correlations with resilience: positive emotions/optimism, active problem-focused coping, moral courage and altruism, capacity to regulate emotions, cognitive flexibility, religiosity/spirituality, high level of positive social support and commitment to a meaningful purpose. Program impact also may be due in part to the integration of three evidence-based program aspects which have thus far had limited application in resilience trials: storytelling, character strength education, and training in spiritual practices. During GROW Zambia’s implementation, major attention was also given to cultural adaptability, which has been shown to enhance the efficacy of minimally guided psychological interventions (Harper Shehadeh et al., Citation2016).

Limitations

Questionnaire results should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. Completion of the lengthy English questionnaire was noted to be challenging during the limited pilot testing we conducted. This resulted in elimination of half the proposed items and the provision of a proctor who could explain unclear items in the vernacular. Even so, analysis of responses to reverse worded items indicated that many students struggled with comprehension. As mentioned previously, none of the measurement instruments had been validated with Zambian adolescents. Despite good Cronbach’s alphas for many of the scales, there is no information on the test-retest reliability of these measures with Zambian adolescents. Further, we find that the scales are not correlated with each other in expected fashion, suggesting poor convergent validity. Perhaps unsurprisingly, analyses showed inconsistent intervention impact on the study’s seven secondary outcomes (Tables S5, S6). Findings could have been limited by ceiling effects – participants scored near the top of the range for most measures (Table S7). High scores may also reflect social desirability bias (Tirrell et al., Citation2020).

Delivery and assessment of the program primarily in English, as opposed to the mother tongue of the participants, is another limitation. Despite intensive English instruction in Lusaka schools by Grade 4, English literacy varied widely among GROW students, which clearly impacted quantitative assessment and may have affected the program’s impact – those fluent in English may have benefited more from GROW. While GROW leaders answered students questions about program content in a local language (usually Nyanja or Bemba) and proctors did the same for both qualitative and quantitative assessments, it is difficult to know how much meaning was lost.

We regret that this program’s English literacy requirement appears to have inadvertently excluded some of Lusaka’s most underprivileged children. Poorer students, whose parents were not fluent in English, were less likely to be fluent in English by Grade 5 or 6 and were thus ineligible to participate. Since not all students in Lusaka speak the same Zambian language at home, finding an equitable solution that meets all students’ needs is challenging. Efforts to meet this need must be balanced with the instructional benefit of increased English fluency noted by some parents, who felt that their children were more likely to pass their comprehensive seventh grade exams and continue their education in secondary school as a result of the participating in the GROW program. One option for future GROW programs could be to teach some GROW groups in the regional Zambian language of the host area (Nkolola-Wakumel & Simwinga, Citation2008) in order to offer resilience training to children who are not in school or who have lower levels of English literacy.

Another limitation was the inability to include both older and younger students who wanted to participate. GROW Zambia focused on children ages 11–12 because of the unique opportunity for character and spiritual growth at this developmental stage. However, with age-appropriate adaptations, it is possible that GROW could also be effective with older and younger youth. Our program design included involving one teacher at each school as a co-trainer to facilitate program continuity and dissemination within the school. Future projects could focus on providing limited coaching support for these teachers to facilitate such dissemination.

A final limitation is the lack of religious diversity in the target population. This pilot occurred in a predominantly Christian country. Further testing is needed to assess GROW’s effectiveness in enhancing character growth among in populations of other faiths or societies with a more secular orientation.

Future directions

We anticipate that GROW could be even more effective if taught in the primary language of the learners. We strongly recommend that future GROW projects translate the leader training card and curriculum, which were designed to be simple and reproducible, as well as the assessment instruments, into the area’s most widely spoken local language, and that research teams first validate instruments with the population to be evaluated (Tirrell et al., Citation2020). Assessment also could be enriched by inclusion of additional objective measures such as school grades, attendance records, dropout and matriculation rates, rates of teen pregnancy, measures of leadership and acts of service. Based on our study and others confirming the value of ongoing adult mentoring (Grossman & Rhodes, Citation2002; Rhodes & DuBois, Citation2008), we encourage continuing GROW activities for a minimum of one year. GROW was designed for oral learners and thus could be taught to children of low literacy. It can be offered through after school programs, churches, civic organizations, and in schools that might desire to use it as part of their religious instruction. Because the GROW curriculum, leader training card, training video and train the trainer materials are available online at http://growglobalresilience.com, scaling of the program appears feasible with the addition of basic school supplies (pencils, paper, and blackboard). Leaders must invest the time needed to participate in a two-day training and dedicate four hours per week to preparing and leading GROW sessions. Smartphones, if available, can help GROW leaders network for communication and mutual support.

Conclusion

This pilot evaluation study tentatively suggests the potential of a low-cost, spiritually-based, youth character strengths intervention taught through storytelling to enhance psychological resilience among young people living in LMICs. Our experiences highlight the need for careful attention to adaptation of programs and evaluation methods to local cultural contexts.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (45.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of John Rogers Knight, Jr., MD; Himani Byregowda, MPH; Maddie O’Connell, MPH; Jordan Levinson, BA; Megan Cooper; and Marissa Carty to this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Data availability statement

Study data available at https://osf.io/57ft2/ may be accessed by researchers in adolescent resilience, positive youth development, positive psychology, or religiousness/spirituality who work at an institution with a Federal Wide Assurance (U.S.) or equivalent accreditation, and who wish to conduct secondary analysis of the data. Investigators should send an inquiry describing their qualifications, research objectives, and planned analysis of the data to the corresponding author. Requests will be reviewed and approved by an independent third party.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, A., Seligman, M. E., Tetlock, P. E., & Duckworth, A. L. (2016). Teaching well-being increases academic performance: Evidence from Bhutan, Mexico, and Peru. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania]. University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3358&context=edissertations

- Barry, M. M., Clarke, A. M., Jenkins, R., & Patel, V. (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 835. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-835

- Barton, Y. A., & Miller, L. (2015). Spirituality and positive psychology go hand in hand: An investigation of multiple empirically derived profiles and related protective benefits. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(3), 829–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0045-2

- Biswas-Diener, R. (2006). From the equator to the North Pole: A study of character strengths. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 7(3), 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-3646-8

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carmody, B. (2003). Religious education and pluralism in Zambia. Religious Education, 98(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344080308289

- Catalano, R. F., Skinner, M. L., Alvarado, G., Kapungu, C., Reavley, N., Patton, G. C., Jessee, C., Plaut, D., Moss, C., Bennett, K., Sawyer, S. M., Sebany, M., Sexton, M., Olenik, C., & Petroni, S. (2019). Positive youth development programs in low- and middle-income countries: A conceptual framework and systematic review of efficacy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.024

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

- Crawford, E., Dougherty Wright, M. O., & Masten, A. S. (2006). Resilience and spirituality in youth. In E. C. Roehlkepartain, P. E. King, L. Wagener, & P. L. Benson (Eds.), The handbook of spiritual development in childhood and adolescence (pp. 355–370). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976657.n25

- Diggle, P. J., Heagerty, P., Liang, K., & Zeger, S. L. (2002). Oxford statistical science series: Vol. 25. Analysis of longitudinal data (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

- East, L., Jackson, D., O’Brien, L., & Peters, K. (2010). Storytelling: An approach that can help to develop resilience. Nurse Researcher, 17(3), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2010.04.17.3.17.c7742

- Good, M., & Willoughby, T. (2008). Adolescence as a Sensitive Period for Spiritual Development. Child Development Perspectives, 2(1), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00038.x

- Grossman, J. B., & Rhodes, J. E. (2002). The test of time: Predictors and effects of duration in youth mentoring relationships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014680827552

- Harper Shehadeh, M., Heim, E., Chowdhary, N., Maercker, A., & Albanese, E. (2016). Cultural adaptation of minimally guided interventions for common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 3(3), e44. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5776

- Harris, S. K., Sherritt, L. R., Holder, D. W., Kulig, J., Shrier, L. A., & Knight, J. R. (2008). Reliability and validity of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality among adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health, 47(4), 438–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-007-9154-x

- Harris, S. K., Woods, E. R., Sherritt, L., Van Hook, S., Boulter, S., Brooks, T., Carey, P., Kossack, R., Kulig, J., & Knight, J. R. (2009). A youth-provider connectedness measure for use in clinical intervention studies [Abstract]. Journal of Adolescent Health, 4(Suppl. 2), S35–S36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.10.099

- Kieling, C., Baker-Henningham, H., Belfer, M., Conti, G., Ertem, I., Omigbodun, O., Rohde, L. A., Srinath, S., Ulkuer, N., & Rahman, A. (2011). Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: Evidence for action. The Lancet, 378(9801), 1515–1525. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1

- Krause, N., Bruce, D., Hayward, R. D., & Woolever, C. (2014). Gratitude to God, self‐rated health, and depressive symptoms. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(2), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12110

- Lerner, R. M. (2004). Liberty: Thriving and civic engagement among America’s youth. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452233581

- Leventhal, K. S., Gillham, J., DeMaria, L., Andrew, G., Peabody, J., & Leventhal, S. (2015). Building psychosocial assets and wellbeing among adolescent girls: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 45, 284–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.09.011

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Masten, A. S. (2004). Regulatory processes, risk and resilience in adolescent development. In R. E. Dahl & L. P. Spears (Eds.), Annals of the NY Academy of Sciences: Vol. 1021. Adolescent brain development: Vulnerabilities and opportunities (pp. 310–319). NY Academy of Sciences.

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112

- Nguyen, K., Stanley, N., Stanley, L., & Wang, Y. (2015). Resilience in language learners and the relationship to storytelling. Cogent Education, 2(1), 991160. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2014.991160

- Niemiec, R. M. (2019). Finding the golden mean: The overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 32(3–4), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674

- Niemiec, R. M. (2020). Six functions of character strengths for thriving at times of adversity and opportunity: A theoretical perspective. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 551–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9692-2

- Nkolola-Wakumel, M., & Simwinga, J. (2008). Barriers to the use of Zambian languages in education. Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, 22(2), 143-162. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334658076_Barriers_to_the_Use_of_Zambian_Languages_in_Education

- Panter-Brick, C., Eggerman, M., Ager, A., Hadfield, K., & Dajani, R. (2020). Measuring the psychosocial, biological, and cognitive signatures of profound stress in humanitarian settings: Impacts, challenges, and strategies in the field. Conflict and Health, 14(40), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-020-00286-w

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

- Reivich, K., Gillham, J. E., Chaplin, T. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). From helplessness to optimism: The role of resilience in treating and preventing depression in youth. S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks Eds. Handbook of Resilience in Children (pp. 223-237. Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-48572-9_14

- Rhodes, J. E., & DuBois, D. L. (2008). Mentoring relationships and programs for youth. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00585.x

- Seale, D. M. (2014). Strengths building, resilience, and the Bible: A story-based curriculum for adolescents around the world [Master’s capstone project, University of Pennsylvania]. University of Pennsylvania Scholarly Commons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&context=mapp_capstone

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563

- Simuchimba, M., Cheyeka, A., & Hambulo, F. (2019). Religious education in Zambia at 50 years of independence and beyond: Achievemet and challenges. In edited by Masaiti, G., Education in Zambia at fifty years of independence and beyond: History, current status and contemporary issues. (3d. ed., pp. 227–242). UNZA Press.

- Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., Highberger, L., Rubinstein, H., & Stahl, K. J. (1997). The development and validation of the Children’s hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399

- Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2012). Resilience: The science of mastering life’s greatest challenges. Cambridge University Press.

- Southwick, S. M., Pietrzak, R. H., Tsai, J., Krystal, J. H., & Charney, D. (2015). Resilience: An update. PTSD Research Quarterly, 25(4), 1–10. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V25N4.pdf

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80

- Tirrell, J. M., Dowling, E. M., Gansert, P., Buckingham, M., Wong, C. A., Suzuki, S., Naliaka, C., Kibbedi, P., Namurinda, E., Williams, K., Geldhof, G. J., Lerner, J. V., King, P. E., Sim, A. T. R., & Lerner, R. M. (2020). Toward a measure for assessing features of effective youth development programs: Contextual safety and the ‘big three’ components of positive youth development programs in Rwanda. Child & Youth Care Forum, 49(2), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-019-09524-6

- Underwood, L. G., & Teresi, J. A. (2002). The daily spiritual experience scale: Development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 24(1), 22–33. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_04

- UNICEF. (2020, September 30). Children in Zambia. UNICEF Zambia. https://www.unicef.org/zambia/children-zambia

- Van Ommeren, M. (2003). Validity issues in transcultural epidemiology. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182(5), 376–378. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.182.5.376