ABSTRACT

Previous studies show that spending money on others makes people happier than spending it on themselves. The present study tested and extended this idea by examining the role of active versus passive choice and default choices. Here, 788 participants played and won money in a game, from which some of the earnings could be donated to charity. Participants were randomized to five conditions (control, passive or active choice, default to self or charity). Three measures of subjective well-being (SWB) were used. The results show that people who donated money were happier than people who kept money for themselves, and that active choices elicited significantly more negative affects than passive choices. Also, more people chose to keep the money when this was the default. Last, the greatest effect on happiness was to change from the set default. The results are in line with previous findings in positive psychology and decision making.

What makes people happy? Research has shown that behaviors aimed to benefit someone else has a significant positive effect on happiness (e.g., Geenen et al., Citation2014; Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). Prosocial behavior refers to behavior aimed to protect or benefit other people’s welfare or, simply put, to do good for others (Nelson et al., Citation2014; Weinstein & Ryan, Citation2010). Both correlational studies (Borgonovi, Citation2008) and experimental studies (e.g., Aknin et al., Citation2012a; Geenen et al., Citation2014) show that prosocial behavior has positive effects on happiness and well-being. This is also confirmed in two recent meta-analyses which both found a low-to-moderate significant effect of prosociality on happiness (Curry et al., Citation2018; Hui et al., Citation2020). However, both meta-analyses mentioned that the mechanisms behind this relationship are still unclear and needs further investigation.

Prosocial behaviors involve several different actions ranging from kind gestures to large money donations (Erlandsson et al., Citation2018). One type of prosocial behavior of interest here involves spending money to help others, termed ‘prosocial spending’. Like other prosocial behavior, prosocial spending improves happiness (Aknin et al., Citation2013b, Citation2012b; Dunn et al., Citation2008, Citation2011). For example, Aknin et al. (Citation2013b) found a positive correlation between prosocial spending, well-being, and life satisfaction – even after controlling for income differences, across many different countries. Experimental studies have also found a causal effect of prosocial spending on happiness (Dunn et al., Citation2008; Geenen et al., Citation2014), which was confirmed in a recent meta-analysis examining experimental studies for prosocial behavior (Curry et al., Citation2018). The effect of prosocial spending on happiness has often been compared to, and found superior to, spending money on oneself, termed ‘personal spending’ (Aknin et al., Citation2015). Despite intensive research on the relation between prosocial spending and happiness, the underlying mechanisms driving this effect is not well documented. In the present study, we examine how the choice behind prosocial spending influence happiness.

Choice and happiness

One determinant of how we feel about an outcome is how we made that decision. For example, different emotions can arise whether people make an active or a passive choice (Carroll et al., Citation2011). Active decisions are explicit and voluntarily made decisions that implies that a person has considered pros and cons of the choices before making their decision (Walsch et al., Citation2011), whereas passive decisions are situations where a person does not need to make an explicit choice. Further, having too many choices can sometimes have a negative effect on well-being (Schwartz, Citation2000), as people tend to feel less satisfied and experience lower well-being with their choice when they have many options (Roets et al., Citation2012).

Moreover, research in the behavioral economics of ‘nudging’ has shown that alterations in how choices are presented (i.e., the choice architecture) influence what decisions people make and how people feel about the outcome (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). Nudges are attempts to change a person’s decisions or/and behavior in a predictable way without removing other options or significantly change the person’s economic motives while also being non-costly to avoid (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008).

One of the most common nudge techniques is a ‘default’ (Jachimowicz et al., Citation2019). A default is the pre-selected option that will be chosen when an active decision is not made (Dinner et al., Citation2011; Johnson & Goldstein, Citation2003). Defaults have been shown to be effective in several domains, such as changing people’s decision about whether to donate organs or not (Johnson & Goldstein, Citation2003) and how much money people choose to donate to charity (Altmann et al., Citation2019; Zarghamee et al., Citation2017). Three reasons to why defaults work have been put forth; 1) defaults are perceived as the choice that policy makers recommend (i.e., endorsement), 2) sticking with the default does not require any effort (i.e., inertia), and 3) defaults work like points of reference that other options are compared to, so changing from the defaults requires some trade-off (i.e., status quo; Dhingra et al., Citation2012; Johnson & Goldstein, Citation2003). A meta-analysis investigating the effect of defaults showed that defaults are most effective through the mechanisms of endorsement and status quo (Jachimowicz et al., Citation2019). Although much work is done on the effectiveness of defaults, little is known about how default-nudges affect people’s well-being. This will be investigated in this study.

The current study

In summary, although previous research shows that prosocial spending and happiness are positively related (Aknin et al., Citation2013b), the process behind this is not fully understood. To shed light on this, we will examine how the process of deciding to spend on other people and how alterations in the choice architecture will affect people’s well-being.

The overall aim of this study is to replicate the finding that prosocial spending makes people happier than personal spending, and to extend this by examining how people’s happiness levels are affected by active and passive choices, as well as default choices. Thus, we will examine if there are any differences in happiness levels 1) between prosocial spending and personal spending, 2) when the prosocial spending is the result of an active decision compared to a passive decision, and 3) when there is a default set to either prosocial spending or personal spending. Last, in line with recommendations from Curry et al. (Citation2018), we aim to do this with a larger sample size than many previous studies as well as with a representative sample.

Hypotheses

We formulated three hypotheses.

First, we predict that we will replicate the finding that prosocial spending makes people happier than personal spending (Aknin et al., Citation2013b; Dunn et al., Citation2008; Geenen et al., Citation2014).

Second, whether an active or a passive choice will make people happier in a prosocial domain is hard to predict a priori. People making an active decision might be happier than people making a passive decision, but it is also possible that simply being assigned to a choice (i.e., passive decision) makes people happier, since they will not experience any regret with the choice afterwards (Roets et al., Citation2012).

Third, the effect of either follow or change a set default on happiness levels has not yet been tested. Given the adverse effect of choice on happiness (Schwartz, Citation2000), it is possible that people become happier by simply following a default than they will by making the choice to change from the set default option.

Method

Participants

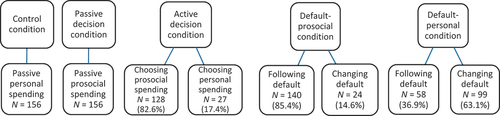

Seven hundred and eighty-eight (N= 788) people (51.0% women, Mage = 54.8) were recruited through CMA Research (now called Origo Group), an independent survey company with a roughly representative sample of the Swedish adult population. There were no significant differences in age or number of participants in the conditions. shows descriptive information about participants in the experiment.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for each condition and in total.

Design

The experiment was conducted online. Participants were randomized to one of five conditions in a between-subject design. The five conditions were control condition, passive choice condition, active choice condition, default-prosocial condition, and default-personal condition (described in detail below).

Prosocial spending was operationalized as charity donations in this study. Previous studies have instructed participants to spend money on whoever they want (e.g., Dunn et al., Citation2008). Here, we enhanced the control of the prosocial behavior by only offering two choices to participants; to either keep money for themselves or donate to a specific charity organization (Médecins Sans Frontières [MSF]). This charity was chosen because it is one of the organizations that Swedish people view as most trustworthy (Erlandsson et al., Citation2018).

Happiness was conceptualized as subjective well-being (SWB) in this study. SWB is a hedonic construct of happiness, that is defined as the experience of frequent positive emotions, infrequent negative affects, as well as the experience of high life-satisfaction (Lambert et al., Citation2015; Ryan & Deci, Citation2001).

Measures

Along with participants’ choice to donate (or not), three measures of SWB were the main dependent variables. Each participant answered the three SWB measures twice: before and after the manipulation.

SWB measures

We used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988) as one measure of subjective well-being. It consists of 20 items, which measures 10 positive affects (i.e., PA; e.g., happy, inspired, strong) and 10 negative affects (i.e., NA; e.g., afraid, hostile, frightened). Participants rated how each affect was experienced at the present moment on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much).

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) measures the overall life satisfaction and consists of five items (Diener et al., Citation1985). Life satisfaction is conceptualized as the cognitive, judgmental part of subjective well-being. Because changes in current life satisfaction were of interest, the phrase ‘right now’ were added to all five items, for example, ‘Right now, if I could live my life over again, I would change almost nothing’. Participants rated how well they agreed with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much; Kobau et al., Citation2010).

The Implicit Positive and Negative Affect Test (IPANAT) is an implicit test measuring positive and negative affect using word associations. Implicit affects are defined as cognitive concepts of emotional states that automatically activates (Quirin & Bode, Citation2014; Quirin et al., Citation2009). Participants read six artificial words (Safme, Vikes, Tunba, Talep, Belni and Sukov) that were presented together with three positive feelings (i.e., IPA; happy, cheerful and energetic) and three negative feelings (i.e., INA; helpless, tense and inhibited). They rated how well the artificial words sounded like the feelings on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Doesn’t fit at all, 5 = Fits very well). In this study, two versions of the test were used – the original and a new one – to minimize demand characteristics. In the new version, which was presented before the manipulations, the letters of each original word were scrambled into six new artificial words (Fesma, Sekvi, Nubat, Etlap, Nebli and Kovsu).

Last, we also included two measures of individual differences for exploratory reasons: The Unified Scale to Assess Individual Differences in Intuition and Deliberation (Pachur & Spaar, Citation2015) and Cognitive Reflection Task 7 (Toplak et al., Citation2014). However, as we found no systematic effects of these measures on happiness or choice, these will not be discussed further.

Procedure

First, participants answered demographic variables, read information about the study, and responded to three pre-measures: PANAS, SWLS and IPANAT. After this, participants played a game where they saw five doors and read that a certain amount of money was hidden behind each door. Participants were asked to indicate which door they thought hid the largest amount of money. After choosing a door, they read that they had won 60 SEK (approximately 6.5 USD) and also, received an extra bonus of 20 SEK (app. 2.2 USD). All participants received the same amount, regardless of which door they chose.

After this, participants received different information depending on which condition they had been randomized to. Participants in the control condition read that the money were theirs to spend as they wished. Participants in the passive choice condition read that the bonus of 20 SEK would be donated to MSF, which would use the money in the best way to help people in need (this information was always presented when MSF was part of the manipulation). Participants in the active choice condition got two choices; to either donate the bonus to MSF (prosocial spending choice) or to keep the bonus for themselves (personal spending choice). Participants in the default-prosocial condition read that the bonus was set to go to MSF, but that they could change this if they wanted to keep the money for themselves. If participants wanted to change the default, they were instructed to press a button labeled ‘I want to change’ which then would take them to another page where they could change direction of the bonus. If they instead wanted to follow the choice of the default, they were instructed to press a button labeled ’I am satisfied’. Participants in the default-personal condition read that the bonus was set to go to themselves but that they could change it, so the bonus would be donated to MSF. The procedure for changing or following the set default was identical to the one described for the default-prosocial condition.

Following this phase of the experiments, all participants then rated the following post-measures: PANAS, SWLS, IPANAT, along with the individual difference measures. After this, participants were thanked for their participation and dismissed.

Psychometric properties and exploratory data analysis for the measures

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for all measures. For the main measures, Cronbach’s alfa showed high internal consistency for PANAS (pre-manipulation: α = .88, post-manipulation: α = .89), SWLS (pre-manipulation: α = .91, post-manipulation: α = .92), and IPANAT (pre-manipulation: α = .91, post-manipulation: α = .93).

The correlations were weak for the measures between PA and NA (in PANAS; pre-manipulation: r = .14, post-manipulation: r = .06) respectively IPA and INA (in IPANAT; pre-manipulation: r = .10, post-manipulation: r = .16). Thus, this indicate that the constructs should be separated, rather than combining them to an overall PANAS or IPANAT measure.

Construct validity was also examined. For the explicit and implicit measures, they correlated from r = .29 for INA and NA (both pre- and post-manipulation) to r= .39 for IPA and PA (post-manipulation, pre-manipulation: r= .29). Therefore, implicit and explicit measures will be reported separately. Construct validity for SWLS and IPA was r= .18 (both pre- and post-manipulation), whereas it for SWLS and INA was r= −.10 (pre-manipulation) and r= −.09 (post-manipulation). For SWLS and PA, construct validity was r= .39 (pre-manipulation) and r= .35 (post-manipulation), whereas it for SWLS and NA was r= −.28 (pre-manipulation) and r= −.23 (post-manipulation). Therefore, results of SWLS will also be reported separately.

Normal distribution and outliers were examined, showing that the NA-measure had a bimodal distribution with around 75% of the participants clustered around the lowest value while participants with high values emerged as outliers and extreme values. For the pre-manipulation measure of NA, the skewness value was 1.84 and kurtosis was 4.27. For the post-manipulation measure, skewness was 2.88 and kurtosis was 10.1. Thus, the post-manipulation measure of NA will be excluded in the results, which also strengthens the use of separate constructs instead of using a combined PANAS measure.

Prediction study

As an extra feature to the study, we conducted a small prediction study prior to the main study. Thirty-one (N =31) people were recruited through social media and were asked to predict how happy an average person would be if confronted with eight possible outcomes, derived from the five conditions (the three latter conditions had two possible outcomes, see ), on a scale from 1 to 10 (1 = Not happy at all, 10 = Very happy). A mean score for each scenario was then calculated (see ). The results show that people predicted that choosing prosocial spending in the active decision condition would elicit the greatest happiness (M = 7.27, SD = 1.76), and that opting out in the default-prosocial condition would elicit the least happiness (M = 4.55, SD = 2.11).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for each outcome in the prediction study.

Results

The results of the three hypotheses will be presented separately. shows the eight possible outcomes of participants’ choices and the number of participants (percentage) that chose the two possible outcomes in condition 3–5.Footnote1 When analyzing the results for each hypothesis, the outcomes will be paired differently. The different tests for each hypothesis are described in along with an overview of the results. shows the means for each measure, before and after the manipulations, for each of the eight possible outcomes. All four dependent variables (PA, IPA, INA and SWLS) were examined in all tests, but mainly significant findings will be presented hereafter. For each hypothesis, we obtained both significant and non-significant results in the different measures. These can be seen in .

Table 3. Description and results of each test conducted for the three hypotheses in the study.

Table 4. Means and standard deviations for each measure and each possible outcome from conditions.

Prosocial and voluntary spending

Our first hypothesis stated that prosocial spending would make people happier than personal spending. This was tested in three ways using one-way ANOVAs. Initial differences in the pre-measures of PA, IPA, INA and SWLS were tested, but no significant results emerged. Therefore, only the post measures of these were examined in each test.

In the first test, prosocial spending was compared to personal spending by comparing the ratings of participants in control condition with participants in passive choice condition. Here, a significant result for PA emerged, F(1, 310) = 4.02, p= .046, ηp2 = .013, showing that participants who donated the money experienced significantly more positive affects (M= 29.0, SD = 8.47) than participants who kept the money (M= 26.9, SD = 9.46). show the mean and standard deviations for this test.

Figure 2. Mean and standard deviations for positive affects (PA) for test 1 and 2 when comparing prosocial spending to personal spending.

In the second test, prosocial spending was again compared to personal spending by including participants from all five conditions to either prosocial or personal spending (see for description of how participants were assigned). Again, this yielded a significant result for PA, F(1, 786) = 6.46, p = .011, ηp2 = .008, showing that participants who donated the money experienced significantly more positive affects (M= 29.3, SD = 8.83) than those who kept the money (M= 27.6, SD = 9.08; see ).

In the third test, only participants in the active choice condition were included and tested based on their choice to either donate or keep the money for themselves. No significant results emerged here.

Active and passive choices

The second hypothesis tested the difference in happiness levels between doing an active versus passive choice for prosocial or personal spending in three ways using one-way ANOVAs. Again, no initial differences existed in the pre-measures, so the four post-measures were dependent variables in each test.

In the first test, active choice constituted of all participants in active choice condition whereas passive choice constituted of all participants in both control condition and passive choice condition. The analyses showed a significant result for INA, F(1, 465) = 6.13, p = .014, ηp2 = 0.013, showing that participants who made an active choice experienced more implicit, negative affects (M= 31.5, SD = 11.1) than participants who made a passive choice (M= 29.2, SD = 8.94). show the mean and standard deviations for this.

Figure 3. Mean and standard deviation for implicit negative affects (INA) for test 1 when comparing active and passive choice.

Next, we tested the differences in active versus passive choice for prosocial respective personal spending separately. In the second test, we compared active and passive choices for prosocial spending (see for description of which groups were compared). Again, there was a significant result for INA, F (1, 282) = 4.84, p= .029, ηp2 = 0.017, showing that participants who made a passive choice experienced significantly less implicit, negative affects (M = 28.8, SD = 9.31) than participants who made an active choice (M = 31.4, SD = 10.8). In the third test, we compared active and passive choices for personal spending (see for description). There was a significant result for SWLS, F (1, 181) = 4.08, p = .045, ηp2 = 0.022, showing that participants who made an active choice to take money had significantly higher current life satisfaction (M = 17.8, SD = 5.35) than those who passively received the money (M = 15.8, SD = 4.75).

Defaults

The third hypothesis tested the effect of defaults on happiness, in either following a default or changing from the default. This hypothesis was tested in six different ways using one-way ANOVAs, divided by prosocial and proself spending (three tests each). The active choice condition was included in some tests, since this condition also required making a choice, but without a set default to the choice.

First, before describing the results of the main hypothesis, we found a default effect. As seen in , there was an increase of almost 20% in participants choosing to keep the money for themselves when there was a default than when there was no default (17.4% in active choice condition versus 36.9% in default-personal condition). A slight increase in prosocial spending was also evident when this was the default (about 3% increase, from 82.6% to 85.4%).

Again, initial differences in the pre-measures were tested for PA, IPA, INA, and SWLS for all six tests. There was a significant difference in the first test for PA, F(1, 224) = 3.97, p = 0.05, ηp2 = 0.02. Therefore, an ANCOVA was conducted when examining the first test, with the pre-measure of PA as the covariate. For the other tests and measures, there were no initial differences, so the four post-measures were again dependent variables in the tests.

First, we compared prosocial spending with and without a default. Participants in default-personal condition who chose to donate instead (i.e., opted in) were compared to participants in active choice condition who chose prosocial spending. There was a significant difference in INA, F(1, 224) = 9.54, p = 0.02, ηp2 = 0.041, showing that participants who chose to take the money in the active choice condition experienced more negative, implicit affects (M= 31.4, SD = 10.8) than those who opted in (M= 27.3, SD = 8.82). Further, an ANCOVA was conducted for the post measure of PA, with the pre-measure of PA as a covariate. This yielded a significant result, F(1, 223) = 4.30, p = 0.39, ηp2 = 0.019, showing that participants opting in in the default-personal condition experienced significantly more positive affects (M= 31.2, SD = 8.71) than participants choosing to donate in the active choice condition (M= 27.8, SD = 9.11).

In the second test, prosocial spending was examined by comparing participants in default-prosocial condition who followed the default and participants in the active choice condition who chose prosocial spending. No significant results emerged here.

For the third test, prosocial spending was examined by comparing participants who chose to follow the default in the default-prosocial condition with participants in default-personal condition who changed from the default (i.e., opted in). The results showed a significant difference for INA, F(1, 235) = 5.02, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.021, showing that participants who followed the prosocial default experienced more implicit negative affects (M= 30.1, SD = 10.1) than those who opted in (M= 27.3, SD = 8.82).

In the fourth test, examining proself spending, participants in default-personal condition who followed the default were compared to participants in active choice condition who chose personal spending. There was a significant difference for SWLS, F(1, 84) = 5.79, p = 0.018, ηp2 = 0.064, showing that participants who chose proself spending in the active choice condition had significantly higher life satisfaction (M= 17.8, SD = 5.35) than participants who followed the personal spending default (M= 14.9, SD = 5.11).

In the fifth test, participants in default-prosocial condition who chose to take the money instead (i.e., opted out) were compared to participants in active choice condition who chose to take the money for themselves. The results showed a significant difference for PA, F(1, 49) = 4.99, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.092, showing that participants who opted out experienced significantly more positive affects (M= 31.1, SD = 7.89) than participants who actively chose to take the money for themselves (M= 26.4, SD = 7.30).

Last, in the sixth test, participants in the default-prosocial condition who opted out were compared to participants in default-personal condition who chose to follow the default. No significant results emerged here.

Discussion

This study has investigated how happiness levels are affected by prosocial versus personal spending and by two types of decisions and defaults. The first aim of this study was to replicate the finding showing that prosocial spending makes people happier than personal spending (Dunn et al., Citation2008). The results of this study support this. Second, this study extended this by investigating the role of active and passive choices on prosocial spending and happiness. Our results suggest that people become less happy when they make an active decision than when they make a passive decision. Third, this study is the first to investigate how defaults affect happiness levels. The results show that changing from a set default has the biggest positive effect on happiness compared to making an active choice or following the default, especially when people opt in to prosocial spending.

Growing support for the positive effect on happiness by prosocial spending, in comparison to personal spending, has emerged (Aknin et al., Citation2013a; Dunn et al., Citation2008). The present study adds to this body of research by finding a similar effect in a Swedish sample. Previous studies have also shown that people get significantly happier even when they act prosocial to someone that they will never meet or interact with (Aknin et al., Citation2013b). The results of the current study are in line with this finding since the participants donated to a charitable cause with anonymous targets. This suggests that happiness derived from prosocial spending is not dependent on who the receiver is. This is consistent with the notion of ‘impure altruism’, meaning that people are willing to forego personal economic benefits to help other individuals – even anonymous ones (Andreoni, Citation1990). This is also consistent with findings from neuroscience suggesting that helping others is personally rewarding, and that the same reward centers in the brain are activated when a person receives a personal reward as when a person acts to benefit others (Harbaugh et al., Citation2007).

Further, we found a positive effect on happiness although the prosocial act was small. All participants in the study gained money and only a small portion of the total sum could be donated. Thus, even a rather small prosocial act may increase happiness levels. This is in line with Hui et al. (Citation2020) that argues that even a small-to-moderate effect of prosocial behavior on happiness can be vital. However, this feature of the study design can also have affected our findings. It is possible that the positive effect on happiness was a combination of receiving a larger amount of money and donating a smaller amount of money. Had the whole profit been donated instead, resulting in participants in prosocial conditions not receiving anything for themselves, this positive effect might have diminished or disappeared. This is something future research should examine. Last, it should be noted that out of four measures, the difference in prosocial and personal spending was only found for positive affects. This means that there was no significant difference between prosocial and personal spending for implicit affects (either positive or negative) or life satisfaction.

A second finding of this study is that an active choice evokes significantly more negative affects than a passive choice. This is in line with the idea of ‘tyranny of choice’, suggesting that having to make a choice can have a negative effect on well-being (Schwartz, Citation2000). People can feel overwhelmed and less satisfied with their decision when they are offered several alternatives because they might regret their choice (Roets et al., Citation2012). Although this study only offered participants two alternatives – to donate or to keep the money for themselves – the results are in line with this research. Further, the theory of ‘tyranny of choice’ might also explain why the significant difference between active and passive choice was found only for negative affects, but not for positive affects or life satisfaction. Lessened satisfaction as a cause of having made an active decision is likely to produce negative affects. Theoretically, it is possible that positive affects would also decrease when going from a passive to an active choice. However, positive and negative affects were weakly correlated in the present study, suggesting that they are distinct constructs that may pick up slightly different aspects of the decision process.

Related, we found that people who actively chose to keep the money for themselves had significantly higher life satisfaction than people who passively received money for themselves. A possible explanation for this finding comes from research on opportunity cost (Moche et al., Citation2020), showing that increased awareness of alternative uses of money may act as a reference point for comparison (Greenberg & Spiller, Citation2016). Participants who passively received the money did not know about the prosocial option, whereas participants who made an active decision knew of both options. Thus, when the latter chose to keep the money, they experienced higher overall satisfaction, possibly because they were convinced that this was the right choice of the two possible alternatives for them. However, only life satisfaction, but not the affective measures, yielded a significant difference here. A possible explanation for this could be that the SWLS includes stronger evaluative and cognitive aspects than the affective measures, and that these components may better capture opportunity cost thinking.

The third aim of this study was to test how defaults affect happiness. To our knowledge, no prior study has tested this. The results showed that changing from a default had the greatest effect on happiness, especially when opting in from a default set to personal spending. Further, for people who wanted to keep the money for themselves, the greatest effect on happiness was when they opted out from a prosocial spending-default, and the smallest effect was when they followed the personal spending default. One explanation for this can be that people feel that changing from a default is perceived as more meaningful and sacrificial than following a default (Davidai et al., Citation2012). This suggests that changing from a default is perceived as a more significant decision, especially when opting in for a good cause, which in turn evokes more positive and less negative emotions. However, it should be noted that we found no significant effects on life satisfaction and implicit affects for prosocial spending defaults, and no significant effects on implicit affects for personal spending defaults.

Also, defaults not only affect happiness but also have a direct effect on decisions. Consistent with a large literature on nudging, we found that more people chose personal spending when this was the default than when this was one of two options (Altmann et al., Citation2019; Johnson & Goldstein, Citation2003). However, this effect was rather small since most participants still chose to opt out from the personal spending default.

Related, we found somewhat contradicting results of active decisions on happiness. In some cases, making an active decision increased happiness levels (when changing from a default) and in other cases, it decreased happiness levels (when making an active choice without a set default). One explanation could lie in the effect defaults have on people. Defaults are often viewed as the status quo or an indication of what the policy makers consider to be the better choice (i.e., endorsement; Davidai et al., Citation2012; Jachimowicz et al., Citation2019; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). Thus, when people are given a choice without a set default, they are left to their own devices to figure out what they should do. This increased effort or mental processing may, in turn, decrease their well-being. However, when given a default, people might follow their intuition more easily, viewing the default as a guideline. It is arguably easier to depart, or follow, the default than to make a choice without any guidelines or aid (Dinner et al., Citation2011). Thus, this suggests that defaults evoke less negative affect than active choices.

Last, our prediction study indicates that people are bad at knowing what will make them most happy. Participants thought that making an active choice to spend money on others would yield the greatest happiness, whereas opting out from the prosocial default would yield the least happiness. However, the results from the main study indicate that these predictions were incorrect. This is in line with findings showing that people in general are bad at predicting how outcomes or events will affect their well-being (i.e., affective forecasting; Dunn & Ashton-James, Citation2008; Gilbert, Citation2006; Kahneman & Schkade, Citation1998; Kurtz, Citation2015). This finding also replicates the study by Dunn et al. (Citation2008), where people predicted that personal spending would elicit more happiness than prosocial spending, when it in fact was the other way around.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. For example, participant’s prosocial act was restricted since it always went to one, experimenter-selected, charity organization. This could affect how ‘voluntary’ the prosocial act was and therefore dampen the effect on happiness. Another way would be to offer participants a range of organization to donate to and then compare it to being assigned a specific organization. Likewise, what constituted an active or passive choice was pre-determined, since participants either got a choice with two options or were assigned to one option. Another possibility would have been to ask participants to rate how much control they felt they had when choosing, and by it categorize choices as active and passive. Further, individual characteristics such as how conservative or reactant people are, or how they view nudges and defaults, can affect the response to defaults (Hagman et al., Citation2015; Jung & Mellers, Citation2016). Future research should extend the current results by examining this. Finally, as this study was conducted only in Sweden, cross-cultural generalization becomes impossible. Therefore, future studies should examine if these results hold up in other cultures.

Conclusion

This study adds to a growing body of research showing that prosocial spending makes people happier than personal spending. We add to this literature by showing that the choice itself has hedonic consequences – actively choosing prosocial spending makes people more unhappy than passively choosing it. Last, we show that defaults options affect decisions and that changing from a set default has the greatest effect on happiness, compared to following a default or making an active decision without a set default.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In total, the participants’ choices to donate resulted in 10,440 SEK (roughly 1050 USD) being donated to MSF.

References

- Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., Nyende, P., Ashton-James, C. E., & Norton, M. I. (2013b). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031578

- Aknin, L. B., Broesch, T., Hamlin, J. K., & Van De Vondervoort, J. W. (2015). Prosocial behavior leads to happiness in a small-scale rural society. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 144(4), 788–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000082

- Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., & Norton, M. I. (2012a). Happiness runs in a circular motion: Evidence for a positive feedback loop between prosocial spending and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(2), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9267-5

- Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., Whillans, A. V., Grant, A. M., & Norton, M. I. (2013a). Making a difference matters: Impact unlocks the emotional benefits of prosocial spending. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 88, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2013.01.008

- Aknin, L. B., Hamlin, J. K., & Dunn, E. W. (2012b). Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS ONE, 7(6), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039211

- Altmann, S., Falk, A., Heidhues, P., Jayaraman, R., & Teirlinck, M. (2019). Defaults and donations: Evidence from a field experiment. The Review of Economics and Statistics,101(5), 808–826. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00774

- Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

- Borgonovi, F. (2008). Doing well by doing good. The relationship between formal volunteering and self-reported health and happiness. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11), 2321–2334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.011

- Carroll, L. S., White, M. P., & Pahl, S. (2011). The impact of excess choice on deferment of decisions to volunteer. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(7), 629–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.011

- Curry, O. S., Rowland, L. A., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.014

- Davidai, S., Gilovich, T., & Ross, L. D. (2012). The meaning of default options for potential organ donors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(38), 15201–15205. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211695109

- Dhingra, N., Gorn, Z., Kener, A., & Dana, J. (2012). The default pull: An experimental demonstration of subtle default effects on preferences. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(1), 69–76. http://journal.sjdm.org/10/10831a/jdm10831a.html

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dinner, I., Johnson, E. J., Goldstein, D. G., & Liu, K. (2011). Partitioning default effects: Why people choose not to choose. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 17(4), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024354

- Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., & Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687–1688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150952

- Dunn, E. W., & Ashton-James, C. (2008). On emotional innumeracy: Predicted and actual affective responses to grand-scale tragedies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(3), 692–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2007.04.011

- Dunn, E. W., Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2011). If money doesn’t make you happy, then you probably aren’t spending it right. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.02.002

- Erlandsson, A., Västfjäll, D., Tinghög, G., & Nilsson, A. (2018). Donations to outgroup-charities, but not ingroup-charities, predict helping intentions towards street-beggars in Sweden. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 48(4), 814–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764018819872

- Geenen, N. Y. R., Hohelüchter, M., Langholf, V., & Walther, E. (2014). The beneficial effects of prosocial spending on happiness: Work hard, make money, and spend it on others? The Journal of Positive Psychology, 9(3), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.891154

- Gilbert, D. T. (2006). Stumbling on happiness. Harper press.

- Greenberg, A. E., & Spiller, S. A. (2016). Opportunity cost neglect attenuates the effect of choices on preferences. Psychological Science, 27(1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615608267

- Hagman, W., Andersson, D., Västfjäll, D., & Tinghög, G. (2015). Public views on policies involving nudges. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 6(3), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-015-0263-2

- Harbaugh, W. T., Mayr, U., & Burghart, D. R. (2007). Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations. Science, 316(5831), 1622–1625. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1140738

- Hui, B. P. H., Ng, J. C. K., Berzaghi, E., Cunningham-Amos, L. A., & Kogan, A. (2020). Rewards of kindness? A meta-analysis of the link between prosociality and well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 146(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000298

- Jachimowicz, J., Duncan, S., Weber, E., & Johnson, E. (2019). When and why defaults influence decisions: A meta-analysis of default effects. Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2018.43

- Johnson, E., & Goldstein, D. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338–1339. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091721

- Jung, J. Y., & Mellers, B. A. (2016). American attitudes toward nudges. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(1), 62–74. http://journal.sjdm.org/15/15824a/jdm15824a.pdf

- Kahneman, D., & Schkade, D. (1998). Does living in california make people happy? A focusing illusion in judgments of life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 9(5), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00066

- Kobau, R., Sniezek, J., Zack, M. M., Lucas, R. E., & Burns, A. (2010). Well-being assessment: An evaluation of well-being scales for public health and population estimates of well-being among US adults. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-being, 2(3), 272–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01035.x

- Kurtz, J. L. (2015). Affective forecasting: Teaching a useful, accessible, and humbling area of research. Teaching of Psychology, 43(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628315620952

- Lambert, L., Passmore, H. A., & Holder, M. D. (2015). Foundational frameworks of positive psychology: Mapping well-being orientations. Canadian Psychology, 56(3), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000033

- Moche, H., Erlandsson, A., Andersson, D., & Västfjäll, D. (2020). Opportunity cost in monetary donation decisions to non-identified and identified victims. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(January), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03035

- Nelson, S. K., Della Porta, M. D., Jacobs Bao, K., Lee, H. C., Choi, I., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). “It’s up to you’: Experimentally manipulated autonomy support for prosocial behavior improves well-being in two cultures over six weeks. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(5), 463–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.983959

- Pachur, T., & Spaar, M. (2015). Domain-specific preferences for intuition and deliberation in decision making. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 4(3), 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2015.07.006

- Quirin, M., & Bode, R. C. (2014). An alternative to self-reports of trait and state affect. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000190

- Quirin, M., Kazén, M., & Kuhl, J. (2009). When nonsense sounds happy or helpless: The implicit positive and negative affect test (IPANAT). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(3), 500–516. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016063

- Roets, A., Schwartz, B., & Guan, Y. (2012). The tyranny of choice: A cross-cultural investigation of maximizing-satisficing effects on well-being. Judgment and Decision Making, 7(6), 689–704. http://journal.sjdm.org/12/12815/jdm12815.html

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

- Schwartz, B. (2000). Self-determination. The tyranny of freedom. American Psychologist, 55(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.79

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- Toplak, M. E., West, R. F., & Stanovich, K. E. (2014). Assessing miserly information processing: An expansion of the Cognitive Reflection Test. Thinking & Reasoning, 20(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2013.844729

- Walsh, M., Fitzgerald, M. P.,Gurley-Calvez, T.&Pellillo, A. (2011). Active versus passive choice: Evidence from a public health care redesign. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 30(2), 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1509/jppm.30.2.191

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016984

- Zarghamee, H. S., Messer, K. D.,Fooks, J. R.&Schulze, W. D.Wu, S.&Yan, J. (2017). Nudging charitable giving: Three field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 66, 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2016.04.008