ABSTRACT

Schools, teaching, and learning environments have long been understood and idealised as places of care. Within feminist studies and Science and Technology Studies (STS), scholars have proposed a shift to include non-humans in what we propose to conceive as care arrangements. Drawing on Tronto's feminist ethics of care [1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Routledge], we investigate educational technologies as ‘matters of care’, facilitating and enabling different modes of care. We pay particular attention to the role that educational technologies assume in schools’ care arrangements. The paper is based on a study of four school information systems in Germany. We identify how these systems can be conceived of as antagonists, intermediaries, recipients of care or means to receive care and critically reflect on how this allows us to imagine modes of care with technology in order to create good educational futures.

Introduction

Schools, teaching, and learning environments have long been understood and idealised as places of care pursuing ‘visions of education that emphasize the value of education for humanistic and liberal purposes’ (Livingstone and Sefton-Green Citation2016, 30). In contrast, standardised testing (Mills et al. Citation2002) and educational governance by numbers (Hartong and Förschler Citation2019) are understood to be in conflict with this ideal.

The tension between schools as places of care and the increasing ‘datafication of education’ (Jarke and Breiter Citation2019) has been beautifully illustrated by Bernadine Evaristo (Citation2019) in her novel Girl, Woman, Other. In one of the stories, Evaristo gives an insightful account of the life of a first-generation black school teacher – Shirley – who embarked on her teaching career in a comprehensive school in a deprived, multi-ethnic London neighbourhood with lots of enthusiasm and the aim to ‘raise these children up’. Shirley's early career was characterised by her caring relationship with her pupils. Even after several years of teaching, Shirley ‘remained committed to giving the kids a fighting chance […] realizing everything else was against them with such large classes and lack of resources and parents who didn't have a clue how to help them with their homework’ (234). However, years later ‘a whole raft of computerized data entry, form-filling, stats, inspections and pointless, mandatory after-school staff meetings’ did not leave Shirley ‘room for responding to the fluctuating needs of a classroom of living, breathing, individualized children’ (Evaristo Citation2019, 234).

The increasing importance of educational technologies (edtech) and digital data can be seen as the continuation of the tension between the ideal of teaching as care work and the necessity of accountable educational standards. To examine this tension, education scholars have so far paid attention to digital infrastructures and the ways in which they reconfigure educational practices, hinder or suppress teachers to care for their students (Bradbury Citation2019; Pluim and Gard Citation2018). To counter this narrative, educational technology providers and proponents of data-driven solutions to (what they call) ‘educational problems’ encourage a discourse that conceives an extensive use of technology and data as a successful future mode of care work in education (see, e.g., Perrotta and Williamson Citation2018; Pluim and Gard Citation2018 for critical analysis). However, as Bayne et al. (Citation2020) note, edtech research should avoid drawing on ‘the instrumental framing of digital technology in education – the technology-as-tool rhetoric that so regularly blocks attempts to understand digital education as social and complex’ (XXVI). And indeed, a number of critical education scholars go beyond such instrumental framings equally attending to both negative and generative aspects of datafied education. For example, Macgilchrist (Citation2019) reflects on the roles and intentions of edtech providers in the pursuit of educational equity. Leander and Burriss (Citation2020) explore posthumanist approaches to critical data literacy and Gorur and Dey (Citation2021) investigate how information systems in education refigure power relations. Selwyn et al. (Citation2020) call to imagine educational technologies that ‘can foreground concerns of care rather than competition; cooperation rather than rivalry; imagination rather than corporatized creativity’ (4).

In line with this scholarship, we view educational technologies as sociotechnical systems, implemented across different levels of organising schooling and teaching. Digital data that are produced and used through these systems are not mere representations of educational realities, but assemblages of social, political, technological, and economic elements inscribed in their design (Kitchin and Lauriault Citation2014). To account for the relationality of edtech in schooling, we build on feminist and posthumanist perspectives of care (Mol Citation2008; Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017; Tronto Citation1993) which have enriched early approaches to actor-network theory (ANT) (López-Gómez Citation2019). This feminist ANT considers multiplicities, power asymmetries, invisible labours, and exclusions that are enacted through care arrangements (Lindén and Lydahl Citation2021; Martin, Myers, and Viseu Citation2015).

In this paper, we understand ‘matters of care’ as both a bodily practice and the configuration of care arrangements ‘where care-work appears as distributed amongst people and things and where “delegations” […] of tasks to things are also noted’ (Criado and Rodríguez-Giralt Citation2016, 212–213). Following this line of thought, we conceive of schools as sociomaterial care arrangements that include edtech, data, and ‘others’ other than human actors able to communicate their needs. We explore to what extent educational technologies may be conceived as ‘matters of care’ that enable and facilitate different modes of care work and caring relations for people, schools, infrastructures, and data.

The paper is based on a case study about edtech used for school organisation and management – school information systems (SIS) – which are deployed in public schools in four federal states (Länder) in Germany. We investigate how different school actors such as principals, secretaries, teachers, and edtech developers or support personnel engage in care work through and in opposition to these educational technologies in order to maintain, continue, and repair their datafied schools as places of care. We foreground four roles SIS play in schools as care arrangements: (1) as antagonists, (2) as intermediaries, (3) as recipients of care, and (4) as means to receive care from actors external to a school. Subsequently, we explore how edtech can co-produce and mediate different modes of care. Attending to edtech as ‘matters of care’, we describe nuanced ways in which human and ‘other’ non-human actors negotiate and reconfigure schools as care arrangements through data practices. We conclude with implications for critical edtech research and critical data studies of our conception of educational technologies and data that enable different modes of care work.

Related work

Two strands of research are important for our paper: (1) feminist concepts of care, including those that aim to expand care epistemologies to also include non-human actors and (2) different understandings of education as care work, which so far do not cover non-human actors (such as technologies).

Feminist concepts of care

The starting point for this paper is based on Tronto’s (Citation1993) feminist, political ethics of care which understands care as both a disposition and a practice. Only when both aspects are present, should any work be acknowledged as care. Care practices include the maintaining, continuing and repairing of the ‘world’ to make it as good to live in as possible. Overall, care work is performed in four phases:

caring about as recognition that care is necessary;

taking care of as assuming responsibility and determining ways to provide care;

care-giving as the ‘meeting of needs for care’ (Citation1993, 107) that often implies a direct contact between care-givers and care-receivers;

care-receiving as a response acknowledging the (successful) reception of care.

The distinction between the phases of care is not exclusively analytical for Tronto, but also appears in the (unequal) division of practices and responsibilities in the world, (often) resulting in care that is not provided (well enough). Care should answer the needs expressed by actors (Noddings Citation2015) with resources that usually have limited availability, resulting in conflicts between different care dispositions. A care disposition is directed at creating a good (or better) world establishing the actors (better for whom?) and the teleo-affectivities (better why?) of caring. For example, Bayne et al. (Citation2020) in their manifesto argue ‘we are the campus’ and list openness and respect of distance as some of the values for developing a caring online campus. However, actors can hold multiple, at times competing, care dispositions related to their roles and (limited) resources available to them. In her later work, Tronto (Citation2016) added a fifth element of care – caring with – that ‘imagines the entire polity of citizens engaged in a lifetime of commitment to and benefiting from these principles’ (14). This broad political, societal commitment of care ethics can be translated to care for other ‘others’ than humans, as Bozalek, Zembylas, and Tronto (Citation2020) illustrate in the introduction to their recent book. According to the editors, the political ethics of care allow for ‘moving beyond an emphasis on the human to include more-than-human relationships with environmental and other material entities’ (2).

While their account of care work and its unequal distribution in education does not yet specifically refer to technology as a particular kind of non-human other, the ongoing digitalisation and datafication processes considerably change schools as care arrangements, with edtech and data mediating (and potentially disturbing) a variety of (caring) relationships that, therefore, require consideration from the ethics of care perspective. Bozalek, Zembylas, and Tronto (Citation2020) suggest a turn to new materialist and posthumanist concepts to care-fully account for what counts as important ‘mattering’ in educational context.

The interest in the relation between humans and technology is a central analytical concern in feminist ethics of care in design research (e.g., human–computer interaction). Here, (digital) technologies are understood to be embedded into and configuring sociomaterial ‘care arrangements’ (Criado and Rodríguez-Giralt Citation2016). Once designed, digital technologies are not rigid scripts or stable entities, but continue to be the subject of change and transformation. Some changes take place through the intervention of technology designers, e.g., updates or new political or legal requirements that must be introduced into the software (Baker and Karasti Citation2018). Other changes take place locally through different modes of experimenting and tinkering (Mol Citation2008). Understanding technologies as a part of care arrangements, all these changes can be understood as ‘careful responses’ (Criado and Rodríguez-Giralt Citation2016) and care work. Mol (Citation2008) addresses this by suggesting how ‘[p]otentially helpful technologies should be locally fine-tuned’ (85). According to Mol, local adjustments pave a way of how to balance good care (and, in our case, enabling of good schooling) with attending to the needs of a variety of actors, including both humans and non-humans. Winance (Citation2010, 111) similarly states that

[Care] revolves around assembling and arranging the entities of a collective so that they fit together. To care is to tinker, i.e. to meticulously explore, ‘quibble’, test, touch, adapt, adjust, pay attention to details and change them, until a suitable arrangement (material, emotional, relational) is achieved.

Overall, this view on schools as care arrangements of and relations between heterogeneous entities is grounded in ANT, ‘that treat[s] everything in the social and natural worlds as a continuously generated effect of the webs of relations within which they are located. It assumes that nothing has reality or form outside the enactment of those relations’ (Law Citation2009, 141). ANT subscribes to a generalised symmetry in which social relations may shape technologies or technology relations may shape social worlds. However, as feminist scholar of technoscience Suchman reminds us, although humans and non-humans constitute each other, they do it in different ways: ‘Differences include the fact that, in the case of technological assemblages, persons just are those actants who configure material-semiotic networks, however much we may be simultaneously incorporated into and through them’ (Citation2007, 270).

This article makes a conceptual contribution to critical edtech research by treating schools as empirical, sociomaterial care arrangements, paying attention to local fine-tuning and tinkering. Building upon the concept of non-human agency in relation to Tronto's account of care, this paper expands the conceptualisations of care ethics by identifying the various modes of care work that emerge through the incorporation of digital technologies in education.

Education as care work

Matters of care are a long-standing research interest in educational research (Beck and Cassidy Citation2019; Damarin Citation1994; Noddings Citation2015). One of the first to ask how an ethics of care can inform educational technology was Suzanne K. Damarin (Citation1994). In her account, care is reciprocal: the caring person and the person cared for share the ‘obligation of care’. She argues that non-human objects – e.g., text documents – cannot exert caring relationships; a human interlocutor is always required, able to adjust the care work according to the preferences and needs of the person cared for.

Schools as care arrangements do not only include care work of teachers but also extend their care dispositions to school leadership, administration and management (Smylie, Murphy, and Louis Citation2016; van der Vyver, van der Westhuizen, and Meyer Citation2014). For example, Beck and Cassidy (Citation2019) discuss the perspectives on and conceptions of caring for different educational roles, including teachers and administrators. Green and Tucker (Citation2011) consider policies, practices, and arrangements that create a caring work environment for school employees. Similarly, van der Vyver, van der Westhuizen, and Meyer (Citation2014) examine how school administrators may care for teachers. Smylie, Murphy, and Louis (Citation2016) investigate the conditions for a caring school leadership. The authors consider caring as both a personal and organisational relationship by examining possibilities and constraints for care work, competencies (e.g., understanding of others and their situations), positive virtues and mindsets (moral good), aims and purpose of caring (3).

Hence, care in education is not simply understood in terms of a relation between teachers (as care-givers) and students (as care-receivers), but scholars have argued that

organizational and contextual factors, collective practices amongst school adults, and peer relationships are important to students’ experiences of being cared for and engaged in school and influence their sense of social and emotional safety and school connectedness. (Walls et al. Citation2019, 4)

Research design

This study is based on an empirical analysis of different educational technologies employed in nine K-12 schools from four German federal states – Länder. Each of the Länder is responsible for its own educational system and governance structure; they differ amongst others in their school forms, curricula, and with respect to the technical infrastructure and information systems they deploy. The Ministries of education of the Länder are responsible for design, development, support, and maintenance of SIS; however, some support and maintenance tasks are outsourced to other companies. The four analysed federal states differ in regard to the size of SIS development teams, availability of resources, and frequency of system rollouts (updates). As a result, schools are provided with Länder-specific SIS, adherent to the requirements of educational systems of the Länder such as kinds, transparency, and frequency of reporting duties, or issues of staff affiliation and professional training. SIS are a kind of edtech used for the organisation and management of schooling and teaching. Typical SIS functions include data management (students, staff data), resource management (personnel, finance, space), or classroom management (e.g., timetable planning) (Breiter and Lange Citation2019). In each of the Länder, we identified the variety of SIS according to publicly available documentation. In each school, located both in cities of different sizes and in rural regions, we conducted semi-structured interviews with the users of the Länder-specific SIS. SIS users are school management, school secretaries, persons responsible for school IT, and teachers with administrative duties. We were interested in their accounts of practices related to the use of SIS, and their understanding of good schooling and good education. In addition to the interviews with SIS users, we also conducted interviews with the Ministries’ representatives responsible for SIS design and maintenance (e.g., project and area managers). The scope of care work and dispositions filling the tasks of developers in the Ministry differs significantly from the positions immediately involved in policy-making and governance or in school monitoring. Hence, drawing on the interviews we conducted, we recognise the heterogeneous dispositions, practices, goals, and interests related to the positions held by various actors within the Ministries.

Dealing with the heterogeneity of dispositions and practices within the researched organisations, we faced an analytical challenge. On one hand, following Tronto (Citation1993), dealing with conflicting modes of care presents a fruitful ground for analysis. On the other hand, these conflicting practices arise from sensitive issues such as internal conflicts, challenging circumstances or personal reasons. To conform to the trust placed in us by our interviewees, we present the following anonymised accounts from our empirical study.

For the analysis, we apply the analytical framework of ethics of care (Tronto Citation1993) and posthuman, feminist research approaches to care in technoscience (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017) and in education (Bozalek, Zembylas, and Tronto Citation2020), in order to include both human and non-human actors in our exploration. While the four-fold framework of care that Tronto developed sheds light on care work already taking place at a broader societal level, zooming in to caring activities within at least one phase of care also allows us to notice the emergent challenges faced by individual care-givers (Lindén Citation2021). Hence, in our initial analysis, we investigate all data practices mentioned by our interviewees and relate these to one of the four phases of care according to Tronto. All the research presented here has been conducted before or at the very beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Roles of technologies in school care arrangements

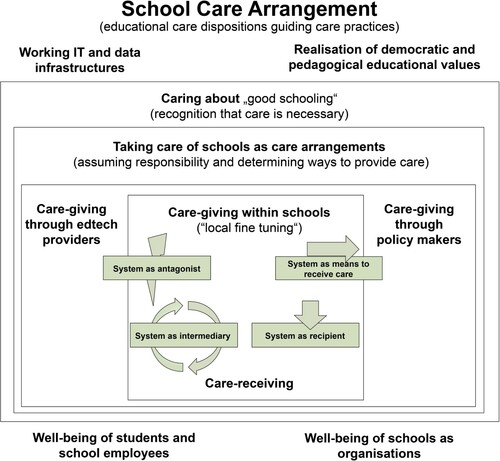

Following Tronto, we conceive the care arrangement of a school as a way to identify what a good school is and does. Hence, we understand care work and dispositions as an answer to the question of what makes a school good. In particular, dispositions here illustrate the directionality and teleo-affectivity of care work and introduce some human and non-human actors (and their relations), for whom school should be good and who partake in maintenance and continuation of good schooling. The range of dispositions we provide here is not exhaustive, nor do the single dispositions exclude one another. Rather, depending on the educational actors, their formal and informal roles in schools, as well as particular practices mentioned, different combinations of dispositions become relevant and may overlap. Through our interviews with employees in schools and Ministries, we identified four dispositions (see also )Footnote1:

the well-being of pupils and school employees,

the reliable and smooth operation of the technical infrastructure (including hardware, software and data),

the well-being of schools as organisations (e.g., a school's public representation, culture and working environment),

the realisation of educational values (pedagogical, didactic, and democratic).

Figure 1. Different roles of educational technologies in a school care arrangement.

The figure depicts the four roles of educational technologies embedded in Tronto’s (1993. Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. Routledge) four-fold concept of care. The four roles of technologies are: system as antagonist, system as intermediary, system as means to receive care, system as recipient. The visualised four roles of technologies are positioned between the care-giving and care-receiving phases of care. Care-giving phase is divided between edtech providers, schools, and policy makers. Recipients of care are located in schools. These and further two phases of care (taking care of and caring about), alongside with four care dispositions, form a school care arrangement.

Those care dispositions allow actors to recognise that care is necessary. Dispositions (1) and (4) emerge on a broader societal level from the schools’ legal obligation and responsibility to empower children to become responsible citizens, while also enabling space for well-being and growth (also in the German understanding of Bildung). Dispositions (2) and (3) emerge from and zoom in on the everyday practices of educational data care-workers. Following Tronto, they care about good schooling and subsequently take care of (their) schools as care arrangements. Our analysis identifies different modes of care-giving through and in opposition to educational technologies, some of which render activities and dispositions visible, while at the same time leaving emotional and moral work invisible. Overall, we identify four different roles SIS play in the care arrangements of schools:

SIS as an antagonist to care,

SIS as an intermediary,

SIS as a recipient of care, and

SIS as a means to receive care.

In the following, we use the care dispositions to investigate how educational technologies are involved in the various modes of care work that we observed in schools. We elaborate on each of the identified roles and reflect on whether and how these roles facilitate care.

A school information system as an antagonist

Similar to the introductory example of Shirley's teaching experiences described by Evaristo, we identified a number of data practices in which SIS assume the role of an antagonist to care work. Such practices are directed at continuing and repairing an organisation of good schooling, while at the same time the systems hinder these endeavours by creating obstacles or additional work for school employees. Most often SIS occupy the role of an antagonist with respect to practices of data input, for example, data input required for new students’ enrolment.

Despite minor differences between the Länder, most SIS require a significant number of data points to be entered into the system in order to create a new student account in the enrolment process. These data points may include the formal information about the student (e.g., name, birthday, nationality), information about the family situation (e.g., parents’ or legal guardians’ names and addresses), the types of previously attended schools (and if applicable, special needs or requirements of special assistance). Depending on when and where a student changes school, some of the required data may be transferred from the previous school automatically. Some data (e.g., special assistance needs) cannot be transferred automatically between the schools (even within the same city) due to data protection regulations. The missing data must be inquired individually and entered into the system manually.

In all schools in our sample, secretaries are responsible for data input. They usually do not have immediate access to the students or their parents and must rely on teachers’ help if questions about any missing data points arise. The interviewed school secretaries often mentioned how the systems do not represent the current realities of students’ lives – for example, according to SIS a student might be too young for the assigned grade (secretary, school 4G), leading to the creation of missing data points. When data points are missing (such as the birthday in the following quote), a student account cannot be created, a student cannot be assigned to their class, and, essentially, be enrolled in the school:

And it is especially difficult if we have children from abroad, for example from Syria […], because they do not even know their birthday and then [we make an entry that] all the children were born January 1st. Not to speak about if they cannot tell us which grade they attended and [the system] wants all of that. It wants everything to be like in Germany, first grade […] whatever, it has to be correct. (Secretary, school 3S)

Though the case described by the secretary is rather extreme, ‘local tinkering’ (Mol Citation2008) of making ‘tentative’ data entries is widely applied to fulfil the disposition of caring for these students. Another secretary in the school 4G explains: ‘so it happens, for example, that one puts a dot after the first name, or some other symbols, so that the student['s account] can be saved and assigned to a class’. In school 1B, data about gifted primary schoolchildren eligible for early enrolment in secondary schools can only be transferred to the secondary school after the latter created a tentative student account, forcing secretaries to make placeholder data entries. Here, the secretaries’ dispositions of caring for students’ well-being in the school (especially those in marginalised positions) stand in conflict with the disposition (and obligation) of ‘not make[ing] any mistakes’ (secretary, school 2D) and maintaining high-quality datasets required to care for the school as an organisation as represented through these datasets.

Since most of the practices described here are interactions between a secretary and a system's user interface, that conflict and redistribution of care often stays invisible even for other school employees or management. The provisional data entries and tinkering only become visible at moments of breakdown – for example, when the school is obliged to provide monitoring agencies with yearly statistics for which the impeccable quality of a school's dataset is required. That breakdown is connected to a change (and conflict) in care dispositions, when caring for students’ well-being becomes part of caring for a school as an organisation that has to be presented to the monitoring agencies through ‘good’ data. Usually, school secretaries are in charge of the school data and responsible for the quality of the datasets. However, they have limited access to the resources they require to provide proper care (cannot take care of), in terms of access to both the data and the system. This includes, for example, the ability to override the system's mechanisms to block the creation of an account due to seemingly invalid or missing information. As a secretary from school 1A sums it up: ‘I am not an IT administrator, neither am I paid for that.’ Hence, feminist ethics of care direct our attention to the redistribution of agency and resources required to provide care: the secretaries are the ones caring about both the students and their data, they perform the act of caring through data entry, and receive immediate feedback from the system about whether the input was valid or not.

A school information system (and related data) as intermediary

Every school in each of the Länder must provide yearly statistics including a variety of data: for example: number of students and teachers, number of provided classes, the results of final examinations. Educational monitoring agencies make planning predictions about the coming school years according to these statistics, and financial as well as human resources are (re-)distributed accordingly. In schools, different staff members are responsible for data entry and data quality management for the statistical data. School secretaries are usually in charge of the data about pupils, the school management is in most cases responsible for data about teachers and school finances, sometimes other actors (e.g., teachers with administrative duties or heads of departments in bigger schools) are responsible for particular data entries. As many different human actors are involved, SIS provide several quality management features such as data plausibility checks and error messages that support their users. Many interviewees perceive such features as helpful:

without these aids and without these tools it would not have been possible to accomplish anything. (Secretary, school 2D)

as soon as we become careless with data input, we directly become aware of it, we have a bunch of kids who do not know where to [go for their classes]. A teacher who runs through the school building looking for the children. And the solution to go back to the old ways, one teacher, one class, the kids left with nothing to wish for; for me it is not an option.

Although the data input here resembles our analysis of SIS as antagonists to care work, an adherence to the disposition of caring for schools as organisations brings forth other modes of care work in data practices. A system as an intermediary supports and makes the tedious work of data input and data quality control easier, providing us with a generative example of datafication of schooling. The identification of needs that must be fulfilled by the intermediary (caring about) takes place in various departments of the Ministries of education long before a particular school is confronted with the obligation to transfer its statistical data. When statistics are required, the systems take on the position of care-givers, performing acts of care. The values and features inscribed in the systems and data infrastructures during their design and development equip these non-human actors with some resources required to perform the care work. Schools and employees responsible for the data are care-recipients, even though, as analysis from the previous section shows, they often lack the opportunity to give a detailed response to this mediated care.

Our analysis illustrates that SIS and their data are an inherent part of schools as care arrangements including all four phases of care as defined by Tronto. For example, maintaining a coherent and gapless dataset about school life is part of a manifold of educational care dispositions regarding the well-being of students, teachers, school as an organisation, and a school's ability to pursue and actualise educational values.

A school information system (and related data) as means to receive care

Sometimes, however, school employees face situations when ‘[a] computer does not understand what happens here in real life’, as school 2D's vice principal puts it when referring to difficulties posed by the requirement to provide certain kinds of data to the Ministries. Depending on the dispositions guiding the school staff, in such situations, systems can be seen as either antagonists or as means to receive care. In the latter case, those responsible for data input in schools may deliberately choose to not care, to not make use of the possibilities to locally tinker and fine-tune the data before passing it on for further processing. For example, a secretary in 3S explains:

So, I must say, when we enter statistical data and errors pop up, then I expect that it would strike [the Ministry's] attention.

While the secretary deliberately neglects the disposition of caring for the quality of the dataset, she simultaneously takes care of the mismatches between school reality and its (expected) statistical representations. We assume that the differences between what school actors conceive as ‘their’ reality and what is expected to be statistically represented create a breakdown, leading to a change of dispositions of data keepers such as secretaries. Even though the SIS developers in the Ministries establish means for user support, the secretary from our example considers these resources to be insufficient to meet the needs of a good school. Using an SIS as means to receive care resembles a distress signal through which school actors oppose the prevailing redistribution of the phases of care. An analysis from the feminist ethics of care perspective hence renders these practices visible and points our attention to the at times conflicting matters that school actors (come to) care about.

A school information system (and related data) as care-recipient

Educational statistics, particularly those about lesson cancellation, are an illustrative example of care work guided by the disposition of caring for SIS and data. In three of the four Länder in which we conducted our empirical research, schools must communicate lesson cancellation statistics to the monitoring agencies on a regular basis, however, with different frequencies (weekly, monthly, and bi-annually). To enable this, most of the analysed SIS have a module about class cancellation that includes the respective Länder’s criteria, defining whether a class was cancelled or not (e.g., in case a substitute teacher delivered the class). However, all the schools we visited use an additional system – a timetable planning software UNTIS – that also provides a feature for documenting class cancellation. Since the timetable is initially planned and organised in UNTIS, all the changes in the timetable including missing classes are initially recorded there: most schools have either a second, ‘shadow’ timetable which documents alternative ways to deliver a particular class or lists of teachers who can serve as a substitute. To transfer the statistics to the school monitoring agencies, in most cases (we encountered), the data must be exported from UNTIS into the respective SIS. However, the Länder and UNTIS use partially different criteria for the documentation of cancelled classes and additional work is required to adjust the different classifications (e.g., what counts as ‘cancellation’ means different things in the different Länder). Importantly, although school management members manually control and adjust their statistics, we did not uncover any fraudulent cases. Instead, as the one teacher and department head in school 2D put it:

[the school's vice principal] is quite scrupulous, so he said: we send nothing that is not correct, so we had to [correct the data] manually.

In a case like this, we understand the data about class cancellation as one of the care-recipients in the complex care arrangement of a school. Similarly, a department head in 2C tells us how he spends much time by tending to the dataset from his department before submitting it to the Ministry.

Focusing on practices concerning class cancellation, we distinguish between a number of dispositions, leading to our understanding of data as recipients of care. In the everyday school routine, documenting and communicating changes in the timetable and lesson cancellation are required to provide timely information to and care for the students. Transferring data about class cancellation statistics to monitoring agencies requires care for schools as accountable organisations: the ‘correct’, interoperable statistical data that provides appropriate accounts about schools ‘representative of school reality’. Even though the Länder publish only aggregated data in their reports, class cancellation statistics can be used by school management at parent-teacher conferences or in further communication with parents. School principal from 3F provides ‘these statistics, not weekly but bi-annually, to […] the parents’ spokespersons’.

Educational technologies as matters of care

With our empirical analysis of SIS, we expand on Tronto's concept of care by identifying four roles that technologies occupy in the data practices of schools’ care arrangements. Depending on the care dispositions and care work, educational technologies can be conceived as antagonists, intermediaries, recipients of care or means to receive care. In the following, we discuss how in negotiations between human actors and ‘others’ assuming each of these roles, schools as care arrangements are being reconfigured. We also discuss how some of the identified roles and relations render visible the ways in which care work is redistributed between actors within and outside schools and what implications this bears for the everyday care work of school employees, as well as for critical education research.

Ethics of care as a political, feminist approach allowed us to showcase different power relations that emerge within different modes of care and from an unequal distribution of resources and agency. These modes of care relate to various combinations of data practices and care dispositions. As these dispositions change, intersect, and overlap, they produce different subject and object positions, which both humans and other actors assume at certain points.

The described conflicts between some dispositions (e.g., students’ well-being or caring for school as organisation by maintaining high-quality datasets) co-exist in the everyday care practices of school and Ministry employees, opening up spaces for ‘antagonist’ modes of care and configuring the role of technologies as antagonists. For example, many features of SIS are inscriptions of modes of care prevailing in the Ministries. Sometimes these modes of care (e.g., directed at creation and maintenance of specific data points about pupils) are in conflict with school secretaries’ modes of care, guided by the disposition of students’ well-being and a smooth operation of school organisation. So, school secretaries are active subjects of the datafication of education as they oppose systems as their antagonists or as they use systems as means to receive care. Local tinkering practices illustrate the (care) work of resistance emerging through conflicts in caring dispositions.

In the moments of breakdown in which actors shift their caring dispositions to fulfil their professional obligations, technologies may assume the role of an intermediary, passing on care across its different phases, resources, and actors. Examples from our study are warning messages or statistical plausibility checks that aim to find and point out possible errors in the data sets. The system’s functionalities directed at finding and ‘fixing’ errors can be conceived of as enabling practices of repair inscribed in SIS by their designers. Essentially, this kind of repair aims to assist quality control. However, when speaking about the role of technologies in care arrangements, considering ‘repair’ may lead us to dangerous ground, where systems are meant to ‘fix’ the complex, messy, and often not digitalised educational processes regardless of whether that ‘fix’ meets the needs of potential care-receivers or not.

It is, thus, helpful to take into account the care dispositions guiding such practices. An example of statistical data quality management illustrates how the processes of estimating the needs can be separated from the act of care over time and space. That may possibly lead to mismatches between the actual needs of schools and those that are being taken care of. The lack of feedback mechanisms required in the phase of care reception sometimes leads to a deliberate neglect of certain care dispositions and puts (human) school actors in an object position. Through local tinkering, secretaries exercise their agency and reconfigure technologies into means to receive care that oppose the prevailing ways of care relations and care work. In our case, both systems as antagonists and as means to receive care hold positions of in-betweenness both analytically and spatially, passing on care work between Ministries and schools.

Considering technologies as recipients of care is arguably the most radical understanding of their role. Feminist ethics of care scholars including Tronto and Mol recognise the possibility of such a relationship. To acknowledge edtech as recipients of care we need to turn to posthumanist approaches. Reviewing ‘what is edtech’ Williamson (Citation2021, 1) shows how educational technologies, both as a concept and as an empirical, material, and digital phenomenon, conflate into

a variety of actors (human and nonhuman), organizations (public, private or multisector), material and technical forms (hardware, software, supporting documents), modes of practice (of teachers, designers, promoters), and framing discourses.

Posthuman approaches teach us how to work with such concepts that exceed the dualities of society/technology, human/non-human, and subject/object. As sociotechnical systems, edtech and the data it produces require a care-ful analysis that attends to the ways in which human and ‘other’ actors shape schools as care arrangements through data practices. Even though it is widely recognised that data (and software, for that matter) do not represent the reality (of schooling) or particular (educational) actors per se (Kitchin and Lauriault Citation2014), they are meant to represent them. Thus, in some contexts data come to matter as meaningful objects that require continuation, maintenance, and repair in order for them to persist and uphold mattering.

Conclusion

On the final pages of Girl, Women, Other, Evaristo (Citation2019) lets Shirley respond to her former student, Carole – now a successful lawyer – that it was her ‘duty as a conscientious teacher’ to support and elevate Carole. Shirley states that she was ‘just doing my job’ (422) and tells Carole that ‘I’m still mentoring the most able children […] still rescuing those who have potential […], those who need my dedicated help over many years to set them on the road to success’ (421). In this account, Shirley reiterates the tension and conflict that her disposition invokes: to care for those students whose ‘road to success’ would otherwise be blocked vis-à-vis an increasingly datafied education system.

With our analysis of educational technologies and data as an inherent part of schools’ contemporary care arrangements, this paper makes a conceptual and an empirical revision of the popular opinion of educators as articulated by Evaristo. In so doing, the paper contributes to critical edtech research and critical data studies in two ways: (1) it draws on feminist ANT scholarship in an emerging domain, educational technologies, and (2) puts forth new concepts and methods for what Lindén and Lydahl (Citation2021, 8) call a ‘double vision of care’ by acknowledging the politics of care and data both as norm and practice. Building on a relational understanding of agency, we explored how edtech distributes and ‘passes on’ (Puig de la Bellacasa Citation2017, 121) care and power asymmetrically between various actors. Care-fully attending to individual, situated accounts of schools’ care-workers allowed us to identify the ‘dark sides’ (Martin, Myers, and Viseu Citation2015) of care in education, such as attempts to ‘fix’ and fit multiplicities into a single account, reliance on automation in favour of improving conditions of data work, and reliance on individual tinkering instead of addressing structural inequalities and invisibilities.

With our analysis, we join critical scholars who are interested in providing a generative critique beyond negative evaluation of edtech and educational data. Empirically, we detailed practices of local tinkering to create accounts about quality of education and good schooling. Building on that, different modes of more care-ful, technologically mediated, data-driven accountability can be imagined. By tending to questions about what a good school and good education might mean, our attention should switch to the actors that have the power to decide on the answers and to locating their accountabilities (Suchman Citation2002) within schools’ as care arrangements. By outlining different forms of care with, through, and against edtech, we shift attention from the tensions different caring dispositions in education evoke to the analysis of distributed agency, power, and resources that enact these tensions in the first place. Thus, even though our analysis shows how non-humans are being meaningfully involved in care work, we align with Noddings (Citation2015, 78) as we imagine futures of schools and Ministries of education as care arrangements that ‘provide the conditions under which on-site workers can engage in caring-for’.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the DATAFIED team members. We also thank Kenneth Horvath, the special issue editors, and the anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and valuable feedback on earlier drafts of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As we did not conduct any interviews with pupils or their guardians, does not present their dispositions.

References

- Baker, K. S., and H. Karasti. 2018. “Data Care and Its Politics: Designing for Local Collective Data Management as a Neglected Thing.” In Proceedings of the 15th Participatory Design Conference: Full Papers – Volume 1 (PDC’18), 1–12. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Bayne, S., P. Evans, R. Ewins, J. Knox, and J. Lamb. 2020. The Manifesto for Teaching Online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Beck, K., and W. Cassidy. 2019. “Teaching in Difficult Times: The Promise of Care Ethics.” In The Compassionate Educator: Understanding Social Issues and the Ethics of Care in Canadian Schools, edited by A. Jule, 31–50. Toronto, ON: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

- Bozalek, V., M. Zembylas, and J. C. Tronto. 2020. “Introduction.” In Posthuman and Political Care Ethics for Reconfiguring Higher Education Pedagogies, edited by V. Bozalek, M. Zembylas, and J.C. Tronto, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Bradbury, A. 2019. “Datafied at Four: The Role of Data in the ‘Schoolification’ of Early Childhood Education in England.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (1): 7–21.

- Breiter, A., and A. Lange. 2019. “Die digitale Schule und Schulverwaltung.” In Handbuch Digitale Verwaltung, edited by H. H. Lühr, R. Jabkowski, and S. Smentek, 330–342. Wiesbaden: Kommunal- und Schulverlag.

- Criado, T. S., and I. Rodríguez-Giralt. 2016. “Caring Through Design?: En torno a la silla and the ‘Joint Problem-Making’ of Technical Aids.” In Care and Design, edited by C. Bates, R. Imrie, and K. Kullman, 198–218. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Damarin, S. K. 1994. “Equity, Caring, and Beyond: Can Feminist Ethics Inform Educational Technology?” Educational Technology 34 (2): 34–39.

- Evaristo, B. 2019. Girl, Woman, Other. London. Hamish Hamilton an imprint of Penguin Books.

- Gorur, R., and J. Dey. 2021. “Making the User Friendly: The Ontological Politics of Digital Data Platforms.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (1): 67–81.

- Green, M. G., and J. L. Tucker. 2011. “Tumultuous Times of Education Reform: A Critical Reflection on Caring in Policy and Practice.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 14 (1): 1–19.

- Hartong, S., and A. Förschler. 2019. “Opening the Black Box of Data-Based School Monitoring: Data Infrastructures, Flows and Practices in State Education Agencies.” Big Data & Society 6 (1): 1–12.

- Jarke, J., and A. Breiter. 2019. “Editorial: The Datafication of Education.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (1): 1–6.

- Kitchin, R., and T. P. Lauriault. 2014. Towards Critical Data Studies: Charting and Unpacking Data Assemblages and Their Work. The Programmable City Working Paper 2. The Programmable City.

- Law, J. 2009. “Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics.” In The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, 1st ed., edited by B. S. Turner, 141–158. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Leander, K. M., and S. K. Burriss. 2020. “Critical Literacy for a Posthuman World: When People Read, and Become, with Machines.” British Journal of Educational Technology 51 (4): 1262–1276.

- Lindén, L. 2021. “Moving Evidence: Patients’ Groups, Biomedical Research, and Affects.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 46 (4): 815–838. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243920948126.

- Lindén, L., and D. Lydahl. 2021. “Editorial: Care in STS.” Nordic Journal of Science and Technology Studies, 3–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.5324/njsts.v9i1.4000.

- Livingstone, S., and J. Sefton-Green. 2016. The Class: Living and Learning in the Digital Age. New York: New York University Press.

- López-Gómez, D. 2019. “What If ANT Wouldn’t Pursue Agnosticism but Care?” In The Routledge Companion to Actor-Network Theory, edited by A. Blok, I. Farias, and C. Roberts, 4–13. London: Routledge.

- Macgilchrist, F. 2019. “Cruel Optimism in Edtech: When the Digital Data Practices of Educational Technology Providers Inadvertently Hinder Educational Equity.” Learning, Media and Technology 44 (1): 77–86.

- Martin, A., N. Myers, and A. Viseu. 2015. “The Politics of Care in Technoscience.” Social Studies of Science 45 (5): 625–641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312715602073.

- Mills, C. N., M. T. Potenza, J. J. Fremer, and W. C. Ward. 2002. Computer-Based Testing. Building the Foundation for Future Assessments. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Mol, A. 2008. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. London: Routledge.

- Noddings, N. 2015. “Care Ethics and “Caring” Organizations.” In Care Ethics and Political Theory, edited by D. Engster and M. Hamington, 72–84. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Perrotta, C., and B. Williamson. 2018. “The Social Life of Learning Analytics: Cluster Analysis and the ‘Performance’ of Algorithmic Education.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (1): 3–16.

- Pluim, C., and M. Gard. 2018. “Physical Education’s Grand Convergence: Fitnessgram®, Big-Data and the Digital Commerce of Children’s Health.” Critical Studies in Education 59 (3): 261–278.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Selwyn, N., T. Hillman, R. Eynon, G. Ferreira, J. Knox, F. Macgilchrist, and J. M. Sancho-Gil. 2020. “What’s Next for Ed-Tech? Critical Hopes and Concerns for the 2020s.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (1): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1694945.

- Smylie, M. A., J. Murphy, and K. S. Louis. 2016. “Caring School Leadership: A Multidisciplinary, Cross-occupational Model.” American Journal of Education 123 (1): 1–35.

- Suchman, L. 2002. “Located Accountabilities in Technology Production.” Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 14 (2): 16.

- Suchman, L. 2007. Human-Machine Reconfigurations: Plans and Situated Actions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tronto, J. C. 1993. Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York: Routledge.

- Tronto, J. C. 2016. Who Cares?: How to Reshape a Democratic Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Selects, an imprint of Cornell University Press.

- van der Vyver, C. P., P. C. van der Westhuizen, and L. W. Meyer. 2014. “Caring School Leadership: A South African Study.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 42 (1): 61–74.

- Walls, J., J. Ryu, L. Fairchild, and J. Johnson. 2019. “Contexts of Belonging: Toward a Multilevel Understanding of Caring and Engagement in Schools.” Educational Policy 35 (5): 748–780.

- Williamson, B. 2021. “Meta-edtech.” Learning, Media and Technology 46 (1): 1–5.

- Winance, M. 2010. “Care and Disability Practices of Experimenting, Tinkering with, and Arranging People and Technical Aids.” In Care in Practice. On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms, edited by A. Mol, I. Moser, and J. Pols, 93–118. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.