ABSTRACT

Documentation of learning through narration and imagery is part of everyday early childhood education. Recently, technology has generated enthusiasm for digital and mobile documentation, where mobility indicates reciprocal communication between home and school using mobile devices. The present paper asks the question of what mobile documentation is doing within the boundaries of a teacher’s personal and professional public–private timespace-materialities. By focusing on documentation of young children’s playful learning shared through social media platforms, I put to work posthuman, feminist materialist theories. What becomes illuminated is that mobile documentation performs within the porous boundaries between a teacher’s personal and professional subjectivities. These actions flow between reproduction, generation, and rupture, with hidden labours and affective costs materialised in the liveliness of timestamps, spatialities, and hashtag entanglements. Whilst mobile documentation practices raise ethical questions, they offer potentialities for accessible ways for teachers to operationalise digital doings that offer hopeful, bite-size, and accessible storytelling.

1. Introduction

Documentation of learning through narration and imagery is an everyday practice for early childhood education and care (ECEC) teachers and used for multiple purposes (Knauf Citation2016). Such practices include assessment as well as making learning processes visible. Recently, teachers have employed technological approaches through digital documentation (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2019; Cowan and Flewitt Citation2021; Flewitt and Clark Citation2020). Lim and Cho (Citation2019) ascribe the term mobile documentation to indicate reciprocal communication between home and school through mobile devices.

Teachers already communicate with families to maintain relationships through technology. Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap (Citation2014) define a ‘virtual holding environment’ through psychodynamic theories to frame the digital world as a space that fosters supportive relationships (95). Homes are part of digital networks with ‘porous boundaries that enable the very youngest children to negotiate affectively intense relationships’ (Flewitt and Clark Citation2020, 447). Yet, entangled within the digital holding environments are the teachers who create the content. Fairchild and Mikuska (Citation2021) highlight the ‘different ways that objects, spaces, material and discursive entities and bodies impact on ECEC workers’ emotions and emotional labour’ (1). For example, academics using Twitter report risks in the merging of personal and professional identities (Jordan Citation2020, 176). According to Selwyn, Nemorin, and Johnson (Citation2017), technology use needs to be recognised as a form of teacher labour.

As technology is fast becoming integrated into pedagogies to keep pace with children’s needs, understanding the place of the digital world for our youngest citizens is paramount (Marsh et al. Citation2020; Mertala Citation2019, 4). But, as digital systems become normalised, research is still catching up and impacts on educational practice remain under examined (Knauf Citation2016; Luo and Xie Citation2019; Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020). With increasing online communication, meanings become networked and changeable (Warfield, Abidin, and Cambre Citation2020, 2). Yet gaps in knowledge remain from educators’ perspectives concerning ‘content, workload burden, ethics, access and equity remain that warrant deeper critical examination, particularly as educators’ practice in increasingly marketised, technical contexts’ (Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020, 11).

By employing posthuman and feminist materialist theories (Taylor Citation2016; Fox and Alldred Citation2017), I explore the labour involved in how one nursery teacher puts mobile documentation to work in the porosity of her public–private timespace-materialities. The paper firstly scopes the position of documentation as digital, mobile and pedagogical, then as an agentic material. Secondly, I build on Lenz Taguchi’s (Citation2010) conceptual framework for thinking of documentation as agentic. Lastly, I will outline a discussion of the actions of mobile documentation between the boundaries of personal and professional subjectivities.

2. Literature review

2.1. Documentation as digital

Digital documentation describes how technology is incorporated into observation and assessment practices through combining video, audio, photography, and written notes (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2020, 4). As such practice becomes widespread, there remains a lack of research into the move from paper to digital systems (Cowan and Flewitt Citation2021). Likewise, there are gaps in knowledge about how it constructs both learning and learners (White et al. Citation2021, 7). This can add nuance to play pedagogies as they shift to more complex iterations that embrace ‘multi-modal, global-local, and traditional-digital activities’ (Edwards et al. Citation2020, 657). For instance, further research is needed into how schools support families’ digital participation (Hooker Citation2019; Kimmons et al. Citation2018).

Moreover, as digital technologies become pervasive, they enmesh into the everyday of childhood social worlds (Danby et al. Citation2018, 2) and reflect the ties between online and offline lives (Fullagar, Parry, and Johnson Citation2018). In education, creating supportive relationships through technology via a ‘virtual holding environment’ benefits doctoral students according to Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap (Citation2014, 91). In their research, Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap (Citation2014) employed Winnicot’s theory of a holding environment in the digital world. Winnicott’s (Citation2009) influential theory posits ‘the prototype of all infant care is holding’ (33) and that can extend through family, school, and social life (238). Virtual forms of the holding environment offer principles beneficial to wider groups that seek online support (Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap Citation2014, 90). Yet, recent research about online therapeutic holding spaces problematise the subversions, interruptions and risks to both privacy and safety in the home (Downing, Marriott, and Lupton Citation2021, 1).

From young children’s perspectives, home literacy practices become a ‘digitally networked space with porous boundaries’ where families make sense of meanings across ‘diverse modes and media’ (Flewitt and Clark Citation2020, 447). Land et al. (Citation2019) explore how technologies like Facetime enable the sharing of stories connected with place, but their focus shifts to children’s relationships with technology as a more environmental and political entanglement (4). Furthermore, Flewitt and Cowan (Citation2019) found gaps in knowledge about how digital documentation within observation practices contribute to theories of learning and assessment (8).

2.2. Documentation as mobile

A related concept to digital documentation is mobile documentation, where smartphones and cloud-based technology reciprocate learning events with families (Lim Citation2017; Lim and Cho Citation2019; Buchholz and Riley Citation2020). Whilst Lim (Citation2017) emphasised support to teachers’ documentation processes in Reggio inspired practices, she found the formation of communities between home and school an important benefit (315). Buchholz and Riley (Citation2020) posit that parental involvement was more heightened through the capacity to ‘leverage digital tools for pedagogical documentation, they can make largely invisible learning processes visible’ (68). Furthermore, it can enable access to family members in real time. Subsequently, parents can read in conversation with children (Lim and Cho Citation2019, 377).

The social media microblogging platform Twitter has become a useful pedagogical tool (Luo and Xie Citation2019). But there are limitations with confidentiality (Fan and Yost Citation2019) and increased visibility with the time it can occupy (Knauf Citation2016). Using social media has presented opportunities for children and families to interlace social worlds, which extends learning value along with teacher status (Knauf Citation2016). Recently, literacy scholars Burnett and Merchant (Citation2021) have drawn attention to ‘messages such as those exchanged on Twitter aggregate to produce a complex textual Web which is multimodal, multi-authored, constantly modifiable, and hyperlinked to other online and offline texts’ (6). For instance, young people have used social media to ‘think in hashtags’, with actions that ‘develop affinities of relation’ (Gleason Citation2018, 178).

That aside, there are limitations in digital and mobile documentation practices.

From educators’ perspectives, photographs can be of poorer quality, along with a lack of social acceptance of smartphone use (Lim Citation2017). Also, there are complexities in deciding its recipients, content and purpose (Buchholz and Riley Citation2020). Along with technical problems, guidance is lacking outside of commercial software (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2020, 4). Furthermore, there are gaps in research about benefits and limitations, leaving little information about how to invest in digital tools Flewitt and Cowan Citation2019)

From families’ perspectives, there are research gaps about how contribution is encouraged (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2019). Whilst parents found digital technology to be valuable and accessible, the majority did not contribute (Flewitt and Cowan, Citation2019). There are multiple reasons for this, including work commitments, multiple households, access, economic status or a preference for traditional contact (White et al. Citation2021, 16). In contrast, Knauf and Lepold (Citation2021) discovered benefits in enabling listening to children’s voices but minor differences between paper and digital portfolios. Then again, children infrequently participate and contribute (Elfström Pettersson Citation2020) but enjoy and have associated learning gains from sharing. Furthermore, software can inhibit independent access (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2019). As teachers may embrace sharing learning within digital applications, there remain gaps in critical research (Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020, 11).

2.3. Documentation as pedagogical

The purposes of documentation practices are associated with the observation of playful engagement that captures learning processes rather than outcomes and has a long pedagogical history. Examples include the Reggio Emilia approach (Edwards et al. Citation2012), learning stories in Aotearoa New Zealand (Ministry of Education Citation2017) and pedagogical narration in Canada (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al. Citation2014). Carr, Cowie, and Mitchell (Citation2016) define pedagogical documentation as ‘material communication tools appropriated or developed by teachers/practitioners or researchers for the purpose of recalling, reflecting on, re-thinking and re-shaping learning, teaching, knowledge and understanding’ (277). Likewise, Cameron and Moss (Citation2020) reiterate the significance of process and the benefits as an ethical, democratic, and political endeavour.

Critiques of pedagogical documentation note its time-consuming nature (Knauf Citation2020, 12; Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017). There is trouble in transplanting practices across socio-political contexts (Fleet, Patterson, and Robertson Citation2017) and risks associated with neglecting complexities (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al. Citation2014). Oversimplification bypasses the democratic values associated with the Reggio Emilia approach (Giamminuti, Merewether, and Blaise Citation2021).

From a child’s perspective, engagement is a cornerstone of rights-based and listening pedagogies that enable participation (Dahlberg, Moss, and Pence Citation2013; Rinaldi Citation2011). That aside, there are perils in subjectification and surveillance (Lindgren Citation2012; Matusov, Marjanovic-Shane, and Meacham Citation2016). In effect, childhoods are defined and produced through documentation (Alasuutari, Markström, and Vallberg-Roth Citation2014). Documentation can entrench asymmetrical power relationships and normalise children being looked upon within a surveillance culture (Sparrman and Lindgren Citation2010).

2.4. Documentation as agentic

The advantage of reading documentation as agentic can open ways of thinking about the liveliness in-between the material, social, and discursive within digital spaces. Identities are shaped within and by the digital world through the ‘generative potential of intra-actions between people, materials, and spaces in their everyday lives.’ (Flewitt and Clark Citation2020, 467). Within such a framing, humans move from the centre of attention. Instead, through new materialist theories (Fox and Alldred Citation2017) the focus moves to what happens between the human and non-human. In this position, the materiality of documentation practices is framed as a ‘methodological tool for learning and change in any pedagogical practice’ (Lenz Taguchi Citation2010, 10). Barad's (Citation2007) physicist thinking has shaped this view. She theorises that agency is generated through ‘intra-action’ instead of interaction: ‘intra-action recognises that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action.’ (Barad Citation2007, 33). Lenz Taguchi (Citation2010) introduced the possibilities of an intra-active pedagogy and posits that documentation is agentic from this orientation: ‘Hence this pedagogy is inclusive of the material as a strong performative agent in learning’ (10).

Studies of agentic documentation attend to non-human affects. When sticky labels are attached, they take on different actions for children and adults (Elfström Pettersson Citation2015). Once three-year-olds had access to cameras; ‘The children and the cameras change the photographic actions through their mutual photographic agency and can then question prevailing norms of looking in preschool.’ (Magnusson Citation2018, 40). Cameras also take on a liveliness in Merewether’s research (Citation2018), and the materials involved (such as notepads, pens, cameras) are ‘agential and are active players in the research.’ (15). However, as much as materialist theories offer resources, they neglect how social structures work (Coole and Frost Citation2010). Critical studies of non-human agencies raise questions of anthropomorphism and neglect broader political, social, and ecological questions (Kraftl Citation2018).

Framing documentation as agentic brings focus to the intra-activity between the social and discursive, where the political and ecological become part of the assemblage (Blaise, Hamm, and Iorio Citation2017; Kummen Citation2014; Pacini-Ketchabaw et al. Citation2014). Documentation practices can reposition teachers’ point of view:

In the doing of pedagogical narrations, artefacts were produced that were not merely representations of our collaborative thinking. Rather, the artefacts that emerged-in between the material, the discursive and the participants, were themselves agentic. (Kummen Citation2014, 808)

The reviewed literature has pointed to the affordances of using digital and mobile documentation and where gaps remain in understanding less visible labours. Whilst documentation is socially mediated it brings new pedagogical tools, but there remains a lack of understanding about the impacts. Whilst Flewitt and Clark (Citation2020) comment on the porosity of social boundaries for young children, my enquiry plugs into the performative agency of mobile documentation between the professional and personal timespaces of teachers. Framing such an enquiry through feminist materialist theories illuminates intra-activities that can bring fresh insights about mobile documentation as an active participant.

3. Method

The methodology for this paper is informed by posthuman and feminist material theories in the ECEC field (Chesworth Citation2019; Fairchild Citation2018; Murris Citation2016; Osgood and Robinson Citation2019). Such theories enable focus on the boundaries of the self, the researcher and the researched (Ringrose, Warfield, and Zarabadi Citation2019, 3). They are useful because ‘digital technologies are not only tools but rather active participants’ (Pischetola et al. Citation2021, 391). Specifically, studies of documentation’s materiality bring focus to the discourses that shape it (Gannon and Davies Citation2012; Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). As documentation has been put to work through the micro-blogging site of Twitter, feminist materialist theories can highlight functions like the hashtag, thereby offering some insight ‘for approaching the entanglement of such emerging and distributed materialities, and the affectivity they produce and induce’ (Edwards and Lang Citation2018, 120).

In this paper, I return to data generated between 2016 and 2017. I collaborated with one participant, Michelle (pseudonym) a nursery teacher who had used Twitter for her documentation practices (Albin-Clark Citation2021). Recruited from professional networks, Michelle taught in a school in North-West England, within an area of high social disadvantage that served a largely monocultural population. In employing post-human ontoepistemological methodologies, I went with sense-making that unfolded and emerged (Taylor Citation2016). As Michelle shared her mobile documentation, I generated data by reframing the interview as an intraview (Kuntz and Presnall Citation2012; Petersen Citation2014). Intraviews take account of more than the transcript of written dialogue, and instead comprise of a ‘co-creation among (not between) multiple bodies and forces’ (Kuntz and Presnell, 2012, 733). This means I was attentive to the visual, sensory, and spoken language (Pink Citation2021). Scholars such as Lemieux (Citation2021) have employed similar approaches in mapping tacit affective states to understand relationality. From young children’s perspectives, embodiment, and space all contribute to meaning making (Pacheco-Costa and Guzmán-Simón Citation2021). This means I took account of embodiment, movement, materials, spaces, location, and temporalities, and used these as data bricolages to enmesh meaning (Barad Citation2007; Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2017).

Ethical processes involved national (British Educational Research Association Citation2018) and institutional requirements. Repurposed social media posts need a reflexive ethics, as the public nature of Twitter creates the illusion of agreed consent (Williams, Burnap, and Sloan Citation2017). To counter this, material was member checked by the participant and identities were further anonymised than presented publicly.

To present the findings, I employed the Baradian term ‘agential cut’ (Citation2007, 140), to map the intra-actions (Elfström Pettersson Citation2017). When pedagogical documentation is made of specific text and image, it becomes an apparatus of knowing (Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). I applied a diffractive analysis by working with data bricolages (Barad Citation2007; Haraway Citation1997). Thus, I looked at notions of relation and pattern (Hultman and Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). Bricolage research also informed my approaches, as layering avoids one story dominating (Kincheloe Citation2001; Odegard Citation2019). Bricolage has commonalities with diffractive analysis as ideas are read with each another and framed as an assemblage (Fox and Alldred Citation2017; Taylor Citation2013, Citation2016).

4. Thinking with data bricolages of mobile documentation

I worked with a series of three tweets made by a nursery teacher, Michelle. The first series traced Michelle’s setting up of a sensory learning enhancement termed ‘Rainbow Spaghetti’ (Figure 2). The second outlined an outdoor family orientated event called ‘Denday’ (Figure 3) and lastly, documentation created on Michelle’s family holiday (Figure 4).

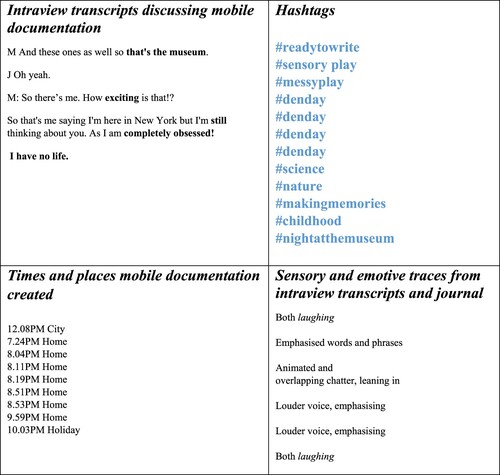

Using the metaphor of a light box, I visualised the bricolage being rearranged and overlaid. I imagined each part illuminated, whilst diffractively reading insights from and through other parts to consider entwined affects (Barad Citation2007). The data bricolages are mapped in . Along with the tweets themselves (), I included audio transcripts with sensory and emotive traces. In addition, the data bricolages included hashtags, the times and places the documentation was produced and encompassed things and words in relation (Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2017; Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). This meant I took account of mobile documentation, intraview transcripts where Michelle and I talked about them, along with journal entries paying attention to notes of sensory and emotional embodiments. Burnett and Merchant (Citation2021) describe similar approaches as; ‘social-material-textual affects’ (6).

4.1. Documentation of Rainbow Spaghetti

Firstly, I lifted samples that Michelle termed ‘Rainbow Spaghetti’ that traced the before and after of learning experiences (). The images and text draw attention to exploratory play, with unconventional materials as a component of playful pedagogy. Cold, cooked, brightly coloured spaghetti sat in bags on Michelle’s kitchen countertop, alongside images from the day after of the sociable squelch and squeeze of fast-moving fingers in an overspilling spaghetti filled tray.

Through attending to the actions of the hashtags (#readytowrite, #sensory play, #messy play), the presence of policy narratives become enmeshed into the assemblage (). Play is positioned as instrumental to curricula progress rather than with children’s interests and intentions. Furthermore, playful pedagogies are not separate from standards agendas but positioned as a mechanism for achievement.

Secondly, from the lightbox I bring the intraview transcript to the foreground:

I would tweet about what we had done in school that day. And I always try to get a little bit of learning into it, a little hashtag to indicate what I think the important things that are going on here … that's me thinking about parents in the first instance that might be looking, ‘oh okay I didn’t realise that was maths. (Michelle)

Additionally, the sensory, embodied traces in intraview transcripts and journals map affect, intra-activity, and the agency of documentation (Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). The tilde punctuation (shared laughter∼paper being lifted∼excited bodies leaning in) indicate the sensory and embodied more-than-human in data bricolages (Barad Citation2007; Bozalek and Zembylas Citation2017). This pointed to embodied actions, sounds, voices, emotions, and senses that relate, layer, and overlap through the research event. Consequently, there is more at work than the visual and written.

Next, I call attention to the temporal–spatial at play when documentation becomes mobile. The data uncovers that Michelle operationalised practices from her family home in the evening, as social media platforms make timestamps and locations noticeable. As mobile documentation spills beyond the working day (7.24PM 8.19PM 9.59PM 10.03PM), the liminal spaces where labours and workload are revealed (Knauf Citation2020; Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017). Not only does this bring visibility, (Knauf Citation2016) as the private space of family life becomes public, it suggests implications for more complex timespace-materialities. Burdens and vulnerabilities become observable when teachers operate in digital contexts (Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020).

The rationale for sending at certain times and places is explained as Michelle wanting families to know she is thinking of them outside of the school day: ‘I think it's that kind of holding in mind thing. It's me saying that you're always in my head … I’m thinking about you now and I'm doing this’ (Michelle). Here, mobile documentation practices act more than a pedagogical tracing, they are informal and emotive, and act in anticipation and reflection. Michelle described this as ‘holding in mind’ and alluded to Winnicott’s theory (Citation2009). Furthermore, documentation exists online, drawing comparisons to Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap’s (Citation2014) ‘the virtual holding environment’ (90). As such, the reaching out to connect a three-way relationship between parent, children and teacher revealed the porous boundaries beyond that of the child (Flewitt and Clark Citation2020). What is illuminated is the teacher and the associated affect within personal and professional timespaces.

Within the porosity of timespace materialities when mobile documentation was created, sent, and rebounded there were other social-material-textual affects at work (Burnett and Merchant Citation2021, 10). To make sense of this, a second sample is illuminated on the imaginary lightbox. This series traced a family focused charity fundraising event that involved denmaking and park rangers in local woodland ().

4.2. Documentation of Denday

Over the course of nine days, the Denday mobile documentation was anticipated, promoted, celebrated, and shared with a wide range of actors. Images and text bounced in-between the charity, parents, park rangers and school in a vibrant network made possible by social media (Burnett and Merchant Citation2021). At the centre, Michelle paints pictures of rich pedagogical and playful practice 'Look at us doing this subject this way’ is a bit of a recurring theme through my twitter’ (Michelle). Again, hashtags have a dynamism, a digital doing (Thompson Citation2016) that gestured toward a conflation of playful learning and curricula subjects; ‘But with the added little tantalisation of the hashtag to try and encourage people to try and find out more about it’ (Michelle). Moreover, more esoteric aspirations are entangled (#denday #science #nature #makingmemories #childhood). As such, Denday accounted for the liveliness between humans and the more-than-human world but also gestured towards multiple learning provocations. Here, digital storytelling draws attention to natural habitats through community engagement of local ecologies, like ‘digital lively place stories’ (Land et al. Citation2019, 1).

The pedagogical materiality is capacious. Michelle’s car boot is packed with fabric and poles for denmaking. Young children explore ponds and small creatures with park rangers and parents delightedly smile at the camera held by Michelle crouched in dens they co-constructed.

And I always try to get a little bit of learning into it a little hashtag to indicate what I think the important things that are going on here. So, I suppose that's me thinking about parents in the first instance that might be looking, might be saying ‘oh okay I didn’t realise that was maths.’ (Michelle)

4.3. Documentation of New York

Further exemplification of pervasiveness is seen in a third tweet from a family holiday. Here we see a museum interior with a large-scale dinosaur model with Michelle’s enacted role play fright that entwines the popular film through the hashtag (#nightatthemuseum). Subsequently, the timespace is stretched far beyond the professional into yet more personal territory, a family holiday on another continent altogether (So that's me saying I'm here in New York but I'm still thinking about you) ().

In the following discussion I consider what affects the continual blurring, collision and rupturing of the porosity between personal and professional timespaces might be doing for Michelle. The speed of online communication brings further complexities to bear in an already challenging teacher subjectivity (Warfield, Abidin, and Cambre Citation2020).

5. Discussion

My research enquiry posed the question about what mobile documentation was doing within a teacher’s personal and professional timespaces. The following discussion presents three overlapping positions of the ‘digital-material-sensory-affective-spatial assemblage’ (Ringrose and Renold Citation2016, 238). Firstly, I offer the view that mobile documentation is generative in its capacity to build communities and affective digital holding environments. Secondly, I problematise the costs involved that rupture public–private timespace-materialities. Thirdly, I illuminate what is reproduced in the policy-pedagogy-performativity assemblage and affect with hashtags seen as sedimentation of policies.

5.1. Position 1 mobile documentation generates

I propose that mobile documentation acts within the timespace-materiality of social media to generate new methodological tools (Lenz Taguchi Citation2010). This offers exemplification of how learning is valued, made visible and shared (Flewitt and Cowan Citation2019; Rintakorpi and Reunamo Citation2017). My findings concur that mobile documentation enables the growth of communities along with the benefits of communicating with a wider range of family members (Knauf Citation2016; Lim Citation2017; Buchholz and Riley Citation2020).

A further affordance is the apparatus of a virtual holding environment (Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap Citation2014). My findings add to Fletcher, Comer, and Dunlap (Citation2014) theorisations as a way for adult learners to connect by extending this to the social materialisation of teacher-family-child relationships in ECEC. Michelle puts to work mobile documentation as a mechanism for ‘holding in mind’ outside of professional timespaces as a core part of her role. In foregrounding community relationships, she is entwining education and care putting it to work in the digital era through mobile documentation.

Moreover, such practices are attuned to technological childhoods (Magnusson Citation2021). Here, pedagogies conflate binary constructions between traditional and digital manifestations (Edwards et al. Citation2020; Lim Citation2017). Mobile documentation in this frame is a material-discursive phenomenom and part of the digital landscape. This could influence how identities and social relations are enacted between online and offline lives (Fullagar, Parry, and Johnson Citation2018).

I argue my findings offer fresh insights about how hashtags operate as a lively matter, as they activate complexities in accessible performativities. I build on Gleason’s (Citation2018) study of young people’s use of hashtags as actions that have agentic capacities and exemplified how a teacher has put them to work. In the Denday examples, the hashtags (#denday #science #nature #makingmemories #childhood) are positioned along with narration and imagery to act as ‘digital lively place stories’ (Land et al. Citation2019, 1). This entangles place, learning, the more-than-human and digital documentation. Furthermore, this finding contributes a contemporaneous reading of Lenz Taguchi’s (Citation2010) theorisation that documentation is a performative agent. I found that hashtags act with an intriguing doing and liveliness across multiple spatialities, that offers exemplification of how Twitter can be used as a pedagogical tool (Luo and Xie Citation2019).

5.2. Position 2 mobile documentation ruptures

The porosity of public–private-timespace-materialities comes with costs that are sensed as affects. Thus, the second position I propose is that mobile documentation ruptures Michelle’s subjectivities. Like Knauf’s findings (Citation2020, 12), Michelle makes documentation outside of professional timespaces, exacerbated by the school internet connection that blocks access. As mobile documentation slips beyond the professional, affective costs materialise (‘I had forgotten how it infiltrates every part of your mind’) (Michelle). Hence, my findings add to the literature of how social media impacts teacher practices (Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020).

Whilst Flewitt and Clark (Citation2020) draw attention to the intra-active agentic experiences of young children using digital media and the dynamic web of social networks in the domestic space, they do not explicitly comment on educators’ documentation practices. Therefore, my findings broaden the gaze to the implications for the teacher who created similar kinds of content. If the home learning environment is ‘a digitally networked space, with porous boundaries that enable negotiation of affectively intense relationships’ (Flewitt and Clark Citation2020), my findings stretch those ‘porous boundaries.’ From that position, I scope the costs entangled into such ‘affectively intense relationships’ (447) of the teacher at the far end of that digital network.

Moreover, I extend recent research by proposing that the boundary rupturing offers a digital exemplification of how objects, spaces, material, and discursive entities impact on ECEC workers emotions and emotional labour (Fairchild and Mikuska Citation2021, 1). Amongst the enthusiasm, (Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020), I suggest boundaries rupture through the weight of maintaining a virtual holding environment ‘I’m obsessed’, ‘I have no life’ ‘It's all in my own time.’ (Michelle). As Magnusson (Citation2021) found, children can extend the boundaries of digital technology by being both users and producers (11), but my research illuminates what affective costs are entwined for teachers as they become users and producers.

Furthermore, with greater visibility there are costs from the investment of time entwined ‘that do not come for free’ (Knauf Citation2016, 268). My findings build on Knauf’s (Citation2016) concept of social media as an interlacing of social worlds yet ‘only possible if the teacher is prepared to be transparent and to invest a great deal of time.’ (254). My findings exemplify that which is not free and the nature of the costs entwined (Knauf Citation2016; Stratigos and Fenech Citation2020).

5.3. Position 3 mobile documentation reproduces

The third position I propose is that mobile documentation acts within assemblages of policy-pedagogy-performativity and affect that reproduces the status quo of curricula narratives. Such narratives associate play with achievement and position the child as ‘measureable’ (Wood Citation2020). Beneath all the documentation activity is the penetration of the neoliberal agenda, governed by ‘explicit standards and measures of performance’ (Moss and Roberts-Holmes Citation2021, 2). Michelle’s values are born from an assemblage that entangles policy narratives. Policy narratives are enmeshed into pedagogy in England, as standards driven regimes direct how quality is defined (Wood Citation2020).

However, as policy is sedimented into hashtags (#readytowrite, #sensory play, #messy play) they have a vibrancy in the assemblage (Ringrose and Renold Citation2016, 238). Whilst they materialise values foregrounding playful pedagogies, they suggest a disruption to dominant discourse by conflating learning as both playful and achieving (Albin-Clark Citation2021). Hashtags are part of this connectivity and ‘digital doing’ (Thompson Citation2016, 484). White et al. (Citation2021) posit there is a lack of knowledge about how learning is positioned through digital platforms (7). These exemplifications of the circulations of hashtags can illuminate what is invisible (Edwards and Lang Citation2018, 132).

My discussion contributes a conflicted exemplification of how learning is constructed through technology where pedagogies are forged in pervasive instrumental policy agendas. As such, my findings point to overlapping actions of generation, rupture, and reproduction at work within a teacher’s public–private timespace-materialities of socially mediated spaces.

6. Conclusion

In summary, I found that for Michelle, mobile documentation had multiple performativities within a reproduction of dominant narratives. Now more than ever, teachers need to tell stories about what is important to them that could open fractures to resist neo-liberal narratives (Moss Citation2015; Moss and Roberts-Holmes Citation2021). Mobile documentation can quickly operationalise hopeful storytelling through lively and accessible ways with hashtags. Additionally, my research exemplifies novel applications of feminist materialisms with the study of the assemblage as a lively vital entanglement (Pischetola et al. Citation2021).

Yet, ethical tensions remain about the suitability of documentation practices through social media that warrants more attention. For teachers such as Michelle, the costs involved were glimpsed through more-than-human elements; including kitchen counter tops, car boots of scrapstore materials and stretched across continents. The timestamps, spatialities, and hashtags were all at work in digital doing (Thompson Citation2016) yet did something more. They materialised labours, costs, and ruptures that bound the digital and everyday (Ringrose and Renold Citation2016, 238). Consequently, teachers need to sense tipping points in the slip from affordance to labour. When boundaries are ruptured, it runs the risk of more damage to personal subjectivities in multiple other personal roles. As this present study is limited to one teacher, there are future enquiries needed into what else ruptures are doing. In the enthusiasm for mobile documentation, we cannot lose sight of the consequences for the lives of women and children (Lenz Taguchi, Semenec, and Diaz-Diaz Citation2020, 39).

Moreover, ethical tensions remain for children documented in digital forms with associated surveillance. When documentation multiplies it becomes accessible, networked, datafied, commodified, visible and ever shifting, and will require more fluid research enquiries. Further research could investigate creating, sending, hashtagging, reading, liking, commenting, datafying and much more besides. As the present research relates to one teacher, there are implications for wider teacher dialogue and professional development. Such enquiries could include how widespread practices are and how social media have infiltrated other pedagogical practices. More importantly, there are broader questions about the ethical suitability of social media and in what ways it is evolving documentation practices.

On a final note, as feminist materialist readings need a political or social justice backbone (Osgood, Diaz-Diaz, and Semenec Citation2020, 49) then mobile documentation needs disentangling from devices in teacher pockets. For now, it is more a case of shoring up boundaries and telling hopeful stories of what matters to teachers. Stories that trouble dominant discourses matter more than ever in a socially mediated educational world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alasuutari, M., A. Markström, and A. Vallberg-Roth. 2014. Assessment and Documentation in Early Childhood Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Albin-Clark, J. 2021. “What is Documentation Doing? Early Childhood Education Teachers Shifting from and between the Meanings and Actions of Documentation Practices.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 22 (2): 140–155. doi:10.1177/1463949120917157.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- BERA (British Educational Research Association). 2018. “Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research.” BERA. Accessed June. https://www.bera.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/BERA-Ethical-Guidelines-for-Educational-Research_4thEdn_2018.pdf?noredirect=1.

- Blaise, M., C. Hamm, and J. Iorio. 2017. “Modest Witness(ing) and Lively Stories: Paying Attention to Matters of Concern in Early Childhood.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 25 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1080/14681366.2016.1208265.

- Bozalek, V., and M. Zembylas. 2017. “Diffraction or Reflection? Sketching the Contours of Two Methodologies in Educational Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30 (2): 111–127. doi:10.1080/09518398.2016.1201166.

- Buchholz, B., and S. Riley. 2020. “Mobile Documentation: Making the Learning Process Visible to Families.” The Reading Teacher 74 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1002/trtr.1908.

- Burnett, C., and G. Merchant. 2021. “Returning to Text: Affect, Meaning Making, and Literacies.” Reading Research Quarterly 56 (2): 355–367. doi:10.1002/rrq.303.

- Cameron, C., and P. Moss. 2020. Transforming Early Childhood in England. London: University College London.

- Carr, M., B. Cowie, and L. Mitchell. 2016. “Documentation in Early Childhood Research: Practice and Research Informing Each Other.” In The SAGE Handbook of Early Childhood Research, edited by A. Farrell, S. Kagan, and K. Tisdall, 277–291. London: Sage.

- Chesworth, L. 2019. “Theorising Young Children's Interests: Making Connections and in-the-Moment Happenings.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 23: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.11.010.

- Coole, D., and S. Frost. 2010. New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics. London: Duke University Press.

- Cowan, K., and R. Flewitt. 2021. “Moving from Paper-Based to Digital Documentation in Early Childhood Education: Democratic Potentials and Challenges.” International Journal of Early Years Education. doi:10.1080/09669760.2021.2013171.

- Dahlberg, G., P. Moss, and A. Pence. 2013. Beyond Quality in Early Childhood Education and Care. London: Routledge.

- Danby, S., M. Fleer, C. Davidson, and M. Hatzigianni. 2018. Digital Childhoods: International Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Development. Vol. 22. Singapore: Springer.

- Downing, L., H. Marriott, and D. Lupton. 2021. “Ninja’ Levels of Focus: Therapeutic Holding Environments and the Affective Atmospheres of Telepsychology during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Emotion, Space and Society 40: 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100824.

- Edwards, C., L. Gandini, G. Forman, and Reggio Children. 2012. The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Experience in Transformation. 3rd ed. Oxford: Praeger.

- Edwards, D., and H. Lang. 2018. “Entanglements That Matter.” In Circulation, Writing, and Rhetoric, edited by Laurie Gries and Collin Gifford Brooke, 118. Utah: Utah State University Press.

- Edwards, S., A. Mantilla, S. Grieshaber, J. Nuttall, and E. Wood. 2020. “Converged Play Characteristics for Early Childhood Education: Multi-Modal, Global-Local, and Traditional-Digital.” Oxford Review of Education 46 (5): 637–660. doi:10.1080/03054985.2020.1750358.

- Elfström Pettersson, K. 2015. “Sticky Dots and Lion Adventures Playing a Part in Preschool Documentation Practices.” International Journal of Early Childhood 47 (3): 443–460. doi:10.1007/s13158-015-0146-9.

- Elfström Pettersson, K. 2017. “Teachers’ Actions and Children’s Interests. Quality Becomings in Preschool Documentation.” Tidsskrift for Nordisk Barnehageforskning 14 (2): 1–17. doi:10.7577/nbf.1756.

- Elfström Pettersson, K. 2019. “How a Template for Documentation in Swedish Preschool Systematic Quality Work Produces Qualities.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 20 (2): 194–206. doi:10.1177/1463949118758714.

- Elfström Pettersson, K. 2020. “Children's Participation in ECE Documentation- Creating New Stories.” In Documentation in Institutional Contexts of Early Childhood, edited by M. Alasuutari, H. Kelle, and H. Knauf, 127–146. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Fairchild, N. 2018. “The Micropolitics of Posthuman Early Years Leadership Assemblages: Exploring More-Than-Human Relationality.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 20 (1): 53–64. doi:10.1177/1463949118793332.

- Fairchild, N., and E. Mikuska. 2021. “Emotional Labour, Ordinary Affects and the Early Childhood Education and Care Worker.” Gender, Work and Organization, 1–14. doi:10.1111/gwao.12663.

- Fan, S., and H. Yost. 2019. “Keeping Connected: Exploring the Potential of Social Media as a New Avenue for Communication and Collaboration in Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Years Education 27 (2): 132–142. doi:10.1080/09669760.2018.1454301.

- Fleet, A., C. Patterson, and J. Robertson. 2017. Pedagogical Documentation in Early Years Practice: Seeing through Multiple Perspectives. London: SAGE Publications.

- Fletcher, K., S. Comer, and A. Dunlap. 2014. “Getting Connected: The Virtual Holding Environment.” Psychoanalytic Social Work 21 (1-2): 90–106. doi:10.1080/15228878.2013.865246.

- Flewitt, R., and A. Clark. 2020. “Porous Boundaries: Reconceptualising the Home Literacy Environment as a Digitally Networked Space for 0–3 Year Olds.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 20 (3): 447–471. doi:10.1177/1468798420938116.

- Flewitt, R., and K. Cowan. 2019. Valuing Signs of Learning: Observation and Digital Documentation of Play in Early Years Classrooms the Froebel Trust Final Research Report. Edinburgh: Froebel Trust. https://www.froebel.org.uk/uploads/documents/guidance-for-practitioners-on-digital-documentation.pdf.

- Flewitt, R., and K. Cowan. 2020. Guidance for Practitioners on Digital Documentation. London: Froebel Trust. https://www.froebel.org.uk/uploads/documents/guidance-for-practitioners-on-digital-documentation.pdf.

- Fox, N., and P. Alldred. 2017. Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action. London: Sage Publications.

- Fullagar, S., D. Parry, and C. Johnson. 2018. “Digital Dilemmas through Networked Assemblages: Reshaping the Gendered Contours of our Future.” In Digital Dilemmas, edited by D. Parry, C. Johnson, and S. Fullagar, 225–243. New York: Springer.

- Gannon, S., and B. Davies. 2012. “Postmodern, Post-Structural, and Critical Theories.” In Handbook of Feminist Research: Theory and Praxis, edited by S. Nagy Hesse-Biber, 2nd ed., 65–91. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Giamminuti, S., J. Merewether, and M. Blaise. 2021. “Aesthetic-Ethical-Political Movements in Professional Learning: Encounters with Feminist New Materialisms and Reggio Emilia in Early Childhood Research.” Professional Development in Education 47 (2-3): 436–448. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1862277.

- Gleason, B. 2018. “Thinking in Hashtags: Exploring Teenagers’ New Literacies Practices on Twitter.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (2): 165–180. doi:10.1080/17439884.2018.1462207.

- Haraway, D. 1997. Modest_Witness@Second_Millenium. Female-Man©_Meets_OncoMouse. New York: Routledge.

- Hooker, T. 2019. “Using ePortfolios in Early Childhood Education: Recalling, Reconnecting, Restarting and Learning.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 17 (4): 376–391. doi:10.1177/1476718X19875778.

- Hultman, K., and H. Lenz Taguchi. 2010. “Challenging Anthropocentric Analysis of Visual Data: A Relational Materialist Methodological Approach to Educational Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 23 (5): 525–542. doi:10.1080/09518398.2010.500628.

- Jordan, K. 2020. “Imagined Audiences, Acceptable Identity Fragments and Merging the Personal and Professional: How Academic Online Identity is Expressed through Different Social Media Platforms.” Learning, Media and Technology 45 (2): 165–178. doi:10.1080/17439884.2020.1707222.

- Kimmons, R., J. Carpenter, G. Veletsianos, and D. Krutka. 2018. “Mining Social Media Divides: An Analysis of K-12 U.S. School Uses of Twitter.” Learning, Media and Technology 43 (3): 307–325. doi:10.1080/17439884.2018.1504791.

- Kincheloe, J. 2001. “Describing the Bricolage: Conceptualizing a New Rigor in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 7 (6): 679–692. doi:10.1177/107780040100700601.

- Knauf, H. 2016. “Interlaced Social Worlds: Exploring the Use of Social Media in the Kindergarten.” Early Years 36 (3): 254–270. doi:10.1080/09575146.2016.1147424.

- Knauf, H. 2020. “Documentation Strategies: Pedagogical Documentation from the Perspective of Early Childhood Teachers in New Zealand and Germany.” Early Childhood Education Journal 48 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1007/s10643-019-00979-9.

- Knauf, H., and M. Lepold. 2021. “The Children's Voice - How Do Children Participate in Analog and Digital Portfolios?” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (5): 669–682.

- Kraftl, P. 2018. “A Double-Bind? Taking New Materialisms Elsewhere in Studies of Education and Childhood.” Research in Education 101 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1177/0034523718791880.

- Kummen, K. 2014. “Making Space for Disruption in the Education of Early Childhood Educators.” The University of Victoria, British Columbia. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e0c2/f6a84ef3d666971a3214b5e0caaf154c1bcb.pdf.

- Kuntz, A., and M. Presnall. 2012. “Wandering the Tactical: From Interview to Intraview.” Qualitative Inquiry 18 (9): 732–744. doi:10.1177/1077800412453016.

- Land, N., C. Hamm, S. Yazbeck, I. Danis, M. Brown, and N. Nelson. 2019. “Facetiming Common Worlds: Exchanging Digital Place Stories and Crafting Pedagogical Contact Zones.” Children's Geographies, 1–14. doi:10.1080/14733285.2019.1574339.

- Lemieux, A. 2021. “What Does Making Produce? Posthuman Insights into Documenting Relationalities in Maker Education for Teachers.” Professional Development in Education 47 (2-3): 493–509. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1886155.

- Lenz Taguchi, H. 2010. Going Beyond the Theory, Practice Divide in Early Childhood Education. London: Routledge.

- Lenz Taguchi, H., P. Semenec, and C. Diaz-Diaz. 2020. “Interview with Hillevi Lenz Taguchi.” In Posthumanist and New Materialist Methodologies, edited by P. Semenec and C. Diaz-Diaz, 33–46. Singapore: Springer Singapore. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2708-1_4.

- Lim, S. 2017. “Mobile Documentation with Smartphone and Cloud in an Emergent Curriculum.” Computers in the Schools 34 (4): 304–317. doi:10.1080/07380569.2017.1387469.

- Lim, S., and M. Cho. 2019. “Parents’ Use of Mobile Documentation in a Reggio Emilia-Inspired School.” Early Childhood Education Journal 47 (4): 367–379. doi:10.1007/s10643-019-00945-5.

- Lindgren, A. 2012. “Ethical Issues in Pedagogical Documentation: Representations of Children through Digital Technology.” International Journal of Early Childhood 44 (3): 327–340. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01517.x.

- Luo, T., and Q. Xie. 2019. “Using Twitter as a Pedagogical Tool in Two Classrooms: A Comparative Case Study between an Education and a Communication Class.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 31 (1): 81–104. doi:10.1007/s12528-018-9192-2.

- Magnusson, L. 2018. “Photographic Agency and Agency of Photographs: Three-Year-Olds and Digital Cameras.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 43 (3): 34–42. doi:10.23965/AJEC.43.3.04.

- Magnusson, L. 2021. “Digital Technology and the Subjects of Literacy and Mathematics in the Preschool Atelier.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 1–13. doi:10.1177/1463949120983485.

- Marsh, J., J. Lahmar, L. Plowman, D. Yamada-Rice, J. Bishop, and F. Scott. 2020. “Under Threes’ Play with Tablets.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 19 (3): 283–297. doi:10.1177/1476718X20966688.

- Matusov, E., A. Marjanovic-Shane, and S. Meacham. 2016. “Pedagogical Voyeurism: Dialogic Critique of Documentation and Assessment of Learning.” International Journal of Educational Psychology 5 (1): 1–26. doi:10.17583/ijep.2016.1886.

- Merewether, J. 2018. “Listening to Young Children Outdoors with Pedagogical Documentation.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (3): 259–277. doi:10.1080/09669760.2017.1421525.

- Mertala, P. 2019. “Digital Technologies in Early Childhood Education - a Frame Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions.” Early Child Development and Care 189 (8): 1228–1241. doi:10.1080/03004430.2017.1372756.

- Ministry of Education. 2017. “Te Whāriki.” New Zealand Government. http://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/ELS-Te-Whariki-Early-Childhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf.

- Moss, P. 2015. “Time for More Storytelling.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2014.991092.

- Moss, P., and G. Roberts-Holmes. 2021. “Now is the Time! Confronting Neo-Liberalism in Early Childhood.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. doi:10.1177/1463949121995917.

- Murris, K. 2016. The Posthuman Child: Educational Transformation through Philosophy with Picturebooks Contesting Early Childhood. London: Routledge.

- Odegard, N. 2019. “Making a Bricolage: An Immanent Process of Experimentation.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. doi:10.1177/1463949119859370.

- Osgood, J., C. Diaz-Diaz, and P. Semenec. 2020. Posthumanist and New Materialist Methodologies: Research After the Child. Singapore: Springer.

- Osgood, J., and K. Robinson. 2019. Feminists Researching Gendered Childhoods: Feminist Thought in Childhood Research. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Pacheco-Costa, A., and F. Guzmán-Simón. 2021. “The (Im)Materiality of Literacy in Early Childhood: A Socio-Material Approach to Online and Offline Events.” Journal of Early Childhood Research. doi:10.1177/1476718X20983852.

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., F. Nxumalo, L. Kocher, E. Elliot, and A. Sanchez. 2014. Journeys. Toronto: University of Toronto Press Higher Education.

- Petersen, K. 2014. “Interviews as Intraviews: A Hand Puppet Approach to Studying Processes of Inclusion and Exclusion among Children in Kindergarten.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 5 (1): 32–45. doi:10.7577/rerm.995.

- Pink, S. 2021. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: SAGE Publications.

- Pischetola, M., L. de Miranda, V. Thédiga, and P. Albuquerque. 2021. “The Invisible Made Visible Through Technologies’ Agency: A Sociomaterial Inquiry on Emergency Remote Teaching in Higher Education.” Learning, Media and Technology 46 (4): 390–403. doi:10.1080/17439884.2021.1936547.

- Rinaldi, Carlina. 2011. “Documentation and Assessment.” In In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia, edited by Carlina Rinaldi, 61–73. London: Routledge.

- Ringrose, J., and E. Renold. 2016. “Cows, Cabins and Tweets: Posthuman Intra-Active Affect and Feminist Fire in Secondary School.” In Posthuman Research Practices in Education, edited by C. Taylor and C. Hughes, 220–241. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137453082_14.

- Ringrose, J., K. Warfield, and S. Zarabadi. 2019. Feminist Posthumanisms, New Materialisms and Education. London: Routledge, Taylor, and Franics Group.

- Rintakorpi, K., and J. Reunamo. 2017. “Pedagogical Documentation and its Relation to Everyday Activities in Early Years.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (11): 1611–1622. doi:10.1080/03004430.2016.1178637.

- Selwyn, N., S. Nemorin, and N. Johnson. 2017. “High-Tech, Hard Work: An Investigation of Teachers’ Work in the Digital Age.” Learning, Media and Technology 42 (4): 390–405.

- Sparrman, A., and A. Lindgren. 2010. “Visual Documentation as a Normalizing Practice: A New Discourse of Visibility in Preschool.” Surveillance & Society 7 (3-4): 248–261. doi:10.24908/ss.v7i3/4.4154.

- Stratigos, T., and M. Fenech. 2020. “Early Childhood Education and Care in the App Generation: Digital Documentation, Assessment for Learning and Parent Communication.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 46 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/1836939120979062.

- Taylor, C. 2013. “Objects, Bodies and Space: Gender and Embodied Practices of Mattering in the Classroom.” Gender and Education 25 (6): 688–703. doi:10.1080/09540253.2013.83486.

- Taylor, C. 2016. “Edu-Crafting a Cacophonous Ecology: Posthumanist Research Practices for Education.” In Posthuman Research Practices in Education, edited by C. Taylor and C. Hughes, 5–24. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Thompson, T. 2016. “Digital Doings: Curating Work-Learning Practices and Ecologies.” Learning, Media and Technology 41 (3): 480–500. doi:10.1080/17439884.2015.1064957.

- Warfield, K., C. Abidin, and C. Cambre. 2020. Mediated Interfaces. New York: Bloomsbury Academic and Professional.

- White, E. J., T. Rooney, A. Gunn, and J. Nuttall. 2021. “Understanding how Early Childhood Educators ‘See’ Learning through Digitally Cast Eyes: Some Preliminary Concepts Concerning the Use of Digital Documentation Platforms.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 46 (1): 6–18. doi:10.1177/1836939120979066.

- Williams, M. L., P. Burnap, and L. Sloan. 2017. “Towards an Ethical Framework for Publishing Twitter Data in Social Research.” Sociology (Oxford) 51 (6): 1149–1168.

- Winnicott, D. 2009. Winnicott on the Child. Boston: Da Capo Press.

- Wood, E. 2020. “Learning, Development and the Early Childhood Curriculum: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Early Years Foundation Stage in England.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 18 (3): 321–336. doi:10.1177/1476718X20927726.