ABSTRACT

In this article, we consider the notion of entangled stories to account for ways that young people assemble stories in generative ways. We draw on Tim Ingold’s theorising of lines, movement, and storied knowledge to account for the visible/material and invisible/immaterial entanglements that happen when young people design multimodal storied worlds and illustrate these entanglements through three school projects in Canada, Norway, and Chile. Literacy studies and the learning sciences have made important contributions to understanding the complexities of meaning-making practices with digital technologies across formal and informal contexts. Yet, there is still work to be done to describe, extrapolate, and theorise digital-material practices and trajectories that young people engage in when they design and craft multimodal compositions.

For inhabitants walk; they thread their lines through the world

rather than across its outer surface. And their knowledge, as I shall

now show, is not built up but grows along the paths they tread.

(Ingold Citation2015, 47)

Introduction

In this article we explore ways that young people gather, assemble, and entangle stories from popular culture, media, and lived experiences to design multimodal compositions. We focus on concepts of movement and entanglement combined with narrative understandings of knowing to describe compositional practices across three school research projects in Canada, Norway, and Chile. Rather than framing learning as wedded to specific contexts like schools and curriculum-based content, we apply Tim Ingold’s work on lines to show how lines move and merge across disparate contexts and weave together texts and lived experiences in all sorts of ways. What we witnessed across our fieldwork is exciting porosity and inextricability among spaces, discourses, subjectivities, and media ecologies.

We offer three analytic cases that came together after several conversations about connections across our work and over these conversations, we came to agree on lines and specifically, entangled story lines as our conceptual lens to interpret multimodal compositional processes. We share a curiosity about the ways that younger generations interweave personal, everyday, contextual, and popular culture stories to make a statement about themselves and how they turn to the world (Rowsell Citation2021). This article is a culmination of our efforts to be more precise about the ways that young people tell and produce stories through modes, thereby hopefully adding complexity to their story-making repertoires that move across borders and boundaries. Though we talked about ways that entangled storying practices by teenagers were different in nature [i.e., a board game (case one); a 3D house (case two); and a Facebook account and memes (case three)], all three analytic cases share similar storying practices that we felt need greater framing and foregrounding in the literature. Ingold’s notion of lines gave us a window into school projects as ‘an unfolding field of relations’ (Ingold Citation2011, 160) between material and non-material entities, which are not self-contained and/or bounded. Drawing in this conceptualisation, boundaries between resources or entities are not pre-given but sustained in mobilities, flows, and assemblages. Like in a story, ‘it is precisely by this context and these relations that every element is identified and positioned’ (Ingold Citation2007, 90). Attuning and discerning flows, relations, positions, and narrative movements prompted us to recognise young people’s compositional work as critical engagements with ideas, beliefs, and knowledge claims.

Respecting more-than-human agencies

The driving force of our theorising in this article comes from Tim Ingold, but what instigated our collaboration was a common interest in feminist sociomateriality and posthuman orientations to the world (Barad Citation2007; Braidotti Citation2013; Haraway Citation1985). The article centres on ways that young people’s designs entangle media, popular culture, personal aesthetics, and lived practices (Rowsell Citationin press) and result in a series of entangled stories. Inevitably, in forming this argument, an underlying assumption is that there is agency across humans with more-than-human forces and entities (Barad Citation2007; Haraway Citation1985). Barad has been particularly helpful for the three of us to explain the agentive roles of digital and analogue texts leveraged during design work. All three of us at various points in our research have come to understand and explain how teenagers design through the intra-actions (a joining up and entangling) of themselves as humans with matter (Barad Citation2007). We witnessed an interdependence between young people and media, objects, people, memories that matter to them. From such a perspective, there is a flattened plane between humans and the more-than-human as equally agentive, meaning that young people pull on all sorts of inspirations and ruling passions to produce a multimodal text (Barton & Hamilton Citation1998; Bailey Citation2021). This is significant because human and more-than-human agents co-constitute each other through what Barad calls intra-actions. Intra-actions allow for an assembling of humans with more-than-humans that challenges an assumption that humans act on matter and preside over material worlds, but are instead co-constitutive within material and non-material entanglements. The notion of entanglements appeals to us in the sense that it allows us to reframe the creative process of young people not a bringing elements from different spaces, but putting them together in emerging and ongoing ways. ‘Entanglements’ run to the heart of our co-analysis together because the term draws attention to the interdependence of media, everyday life, memories, design preferences, feelings, thoughts and beliefs. Our methods rely on an orientation to learning and designing that is ontologically and epistemologically co-constituted across humans and matter. Such an assumption to research methods regards every event observed during fieldwork and interviews conducted with young people (all three of us took observational fieldnotes) as socio-material activities (i.e., as much about matter as people). For the rest of the article, we foreground Ingold’s theories to extrapolate young people’s weaving and entangling of stories to defy and disrupt boundaries. This brief framing of posthumanism and sociomateriality explains how and why we came together to think about a myriad of entangled stories within multimodal compositions.

Theorising entangled story

Ingold’s (Citation2011) theory of lines allows us to see school projects presented in sections that follow as ongoing activities with living and non-living entities, which are not self-contained and bounded/boundaried. The multimodal compositions presented in later sections are defined as lines, but crucially, they are unbounded lines that are in transit, always becoming, and that get (un)meshed in the process of designing multimodal texts. Lines that entangle and disentangle range from popular culture texts to social media outlets to personal memories that assemble during design processes. We asked ourselves during conversations: can material (e.g., eco-designs) and non-material resources and inspirations (e.g., characters in novels) be regarded as separate stories that join up with other stories?

Ingold’s (Citation2011) theorising of the life of lines offered a way to frame stories as having more than one life and as being reassembled into another very different designed story. Ingold’s theorising of lines has an as-yet/becoming/immanent quality to it. We have witnessed a similar becoming and immanent quality to the compositions that young people create. As multimodal composers, children and young people bring to design their own personal stories as distinct lines that cross with a multitude of interests and popular culture influences that they actively weave into multimodal compositions. Ingold talks about the unboundedness of lines as ‘a relation of correspondence between lines’ (Ingold Citation2011, 56). Lines are not thing-like and they do not function as finite entities but instead lines are malleable, and always changing. To illustrate lines, Ingold asks readers to contemplate a storm in the sky which is at once ephemeral and cosmic as much as it is affective (Citation2015, 92) and the key point here is that storms are not finite or linear. Storms pass and move somewhere else, and there is a continual sense of becoming and being in the middle of varied crossing lines that continue and iterate. Experiencing a story often invites an entangling of stories from everyday life, memories, but also eclectic influences from media, literature, and digital lives. In this way, stories are dynamic, ever-changing and emergent with each telling.

Knowledge as storied taskscapes

Ingold’s close anthropological analysis of material practices and ways of being led us to deeper thinking about the life of storylines that entangle across multimodal compositions. In contrast to other research in the field that employ Ingold’s concepts (e.g., Ehret and Hollett Citation2013; Hackett Citation2016; Hillman et al. Citation2016), we do not refer to the physical movements of young people, but to the fluidity of the projects themselves and the practices that students perform when they design stories. Ingold (Citation2011) suggests that knowing – and we can extrapolate knowing to learning and producing meaning in texts – is not about transmission, connections, or analytical separation of bounded aspects and content, but instead a holistic and ongoing experience. Taking our definition of knowing from Ingold, knowing (and by implication knowing through design and composition) does not only involve internalising abstract concepts and systems, but also it involves journeying through an environment and gradually changing an ability to perceive and act within that environment. Stories set in motion relations and perceptions to act and be in environments and stories as intersecting lines forge a path that meanders, moves, and never quite stays the same.

We are interested in young people’s repertoires of storying practices as creative and playful orchestrations of different storylines. Ingold (Citation2011) calls a mesh of related activities or practices taskscapes (Ingold Citation2011, 59). A taskscape assembles tasks and practices into embodied spaces. Meaning is gathered from the processual unfolding of tasks as they move through and about environments. However, from a perspective in which life is meshed and unmeshed in constant movement, the end of a task can be seen as a potential opening or just a stop in a continuous journey (Ingold Citation2011). And we can add that the beginning of a task can be traced back along trails of a continuous journey.

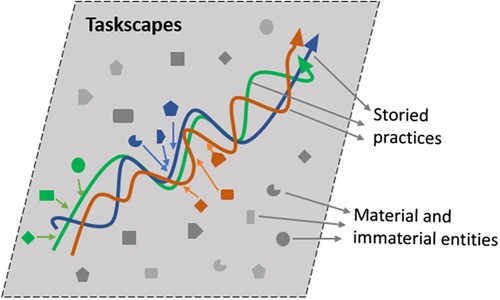

We use Ingold’s concept of taskscapes to describe how young people orchestrate and interweave lines when they craft entangled stories. Ingold describes taskscapes as a gathering ‘of mutually responsive tasks’ (Ingold Citation2017, 17). Taskscapes are not in harmony all of the time, in fact they are sometimes at odds with each other, yet they coalesce within the same time, space, and context. Ingold talks about lines that are straight or curvy (metaphorically speaking), but that can join up into meshwork (Ingold Citation2011). Using the metaphor of a path cut through a cornfield, Ingold argues that ‘lines are not only woven by human beings, for they also tangle with the lines of both non-human animals, such as birds in flight or the lumbering ox, and of plants such as tree-roots and corn-stalks’ (Ingold Citation2017, 25). We offer a figure below () to explain ways that taskscapes as repertoires of practices weave together varied entangled storied lines.

What you see in are storied practices that in Ingoldian terms are lines that criss-cross during design. The storied practices as lines are material/physical/concrete like preferring one colour over another because of cultural associations, the way a project or process unfolds, or immaterial like embedding sentiments or personal stories into a composition or design. The material and immaterial elements are as fluid as storied practices/lines and they circulate in and around the compositional/design process.

Story, for Ingold (Citation2011), can be a way of characterising knowing and knowledge (154). The reason that Ingold’s anthropological framework works so well for us is its participatory, active way of describing how stories come together through human and non-human forces. Our focus on entanglement helps us to capture what we think of as the unbounded nature of young people’s story making/designing/composing. In the article, we use the terms making/designing/composing interchangeably to describe how stories materialise into a design.

Storied practices as lines

Our point of departure from other interpretations of story development in multiple genres of stories, is an argument that the ways that designers make or craft texts involve weaving lines that entangle and move in different ways. To create a language of description for storied making and to cohere with Ingold’s theoretic frameworks, we have developed entangled storied practices.

What started to happen as we applied lines that coalesce and entangle across our specific research are patterns that we identified and that helped us to create a language for entangled story in multimodal compositions. The six entangled storytelling practices are: (1) building/scaffolding existing storied lines; (2) remixed entangled storied lines; (3) relational entangled stories; (4) intramodal/transmodal entangled stories; (5) identity-laden entangled story; and, (6) fractal entangled stories.

Stories are lines in our analytic framing that are embedded and materialise in multimodal compositions. Some lines are anchored in student stories (e.g., memories, events, experiences) materialised in designs whilst others are anchored in relationships between students (i.e., that unfold during design processes and sharing). Other lines derive from media, popular culture, and classical stories that materialise in designs. During our respective studies, we overheard young people move from discussing Pixar movies to characters in novels to stories about when they were children and when these colourful, motley woven lines intersect, they become entangled. Taskscape gives us a language for the common space of this practice. Taskscape as a notion helps us to visualise the weaving together of lines. Taskscape gave us ways to capture multiple story lines woven together into one common space–time. Throughout this article, there are visuals that depict each analytic case and what these do for our thinking to capture each entanglement (as seen in ).

Six storied design practices

There are six storytelling practices that we identified across our research studies. Each practice involves lines intersecting and entangling and each one represents what we think of as new ways of telling stories through multimodal designs. The first storytelling practice is building/scaffolding existing storied lines which describes ways that young people merge and mediate existing bounded storylines from popular culture and media (e.g., Xmen or Marvel characters) and merge and entangle them with more personal, relational story lines. One example might be applying the special skill of an Xmen character or taking the physique of a Marvel character and using it for a character in a short film composition. Jennifer witnessed this storying practice during a research study with 5- and 6-year-olds who produced short, animated films embedding Xmen and Marvel characters into their animated film compositions (Rowsell et al. Citation2018). The children in the study incorporated aspects of Xmen characters and included quotes or references to them and their uniforms in a Toontastic video composition that they produced.

The second storytelling practice is remixed entangled stories evident in Paulina's research with young people creating memes of characters in Isabel Allende’s novel, Of Love and Shadows. To remix, young people in Paulina's research designed a Facebook profile of characters in Allende’s novel and the profile entangled stories in Allende’s novel interfaced with their own ideas, interpretations, and design flair. Character stories are entangled with personal memories, experiences, and thoughts and this entanglement holds material and immaterial qualities within the final Facebook profile.

The third storied line is relationally entangled storytelling to represent moments when participants work in groups to mediate stories based on their own lived experiences and interests. In Hans Christian's analytic case, two teenagers designed an eco-friendly house using a 3D-design programme, and in designing it, their interests and aesthetic preferences merged within the taskscape of the assignment. This example illustrates how relational material storied lines become layered into designed texts.

The fourth story-making practice is intramodal/transmodal entangled storytelling because the practice entails entangling, knotting, and weaving modes (e.g., sound with moving image or words and pictures) while designing a multimodal composition. Jennifer noted this practice during a mixed media research study when a year 11 student constructed a sculpture based on tarot cards that combined a sculpture installation with a written composition (Rowsell Citation2021). This installation is intramodal and transmodal because illustration style, colours, and physical aspects of the sculpture cohere and they are interdependent; for instance, the classic taro illustration style applies a particular palette of colours, textures, and iconography that clearly match Taro visuals and rhetorical tropes.

A fifth pattern is identity-laden entangled storytelling which is design moments when subjectivities are actively and playfully embedded in story lines. During fieldwork, Hans Christian noticed ways that secondary school students mediated their own aesthetic and design choices within their architectural design school project. Identity-laden storylines were evident in the look and feel of student designs and specifically could be seen in the colour palette, shapes, and contours that Han Christian overheard students discuss during his fieldwork.

Finally, a sixth pattern is fractal entangled storytelling. This practice explores ways that pieces or fractals of student stories entangle within a design. For example, in Paulina’s analytic case when a group of students designed a Facebook meme of the character ‘bad luck Brian’ and they merged story fractals or pieces from Allende’s story with their own thoughts into one multimodal composition. Once we began to tease out and apply these six story practices within our analytic cases, we were able to think across our research studies.

The above six storytelling practices run across the three analytic cases presented in the next sections of the article and they serve as our language of description.

Analytic case #1: materialising taskscapes and relational transmodal entangled stories in a board game

The first analytic case explores a SSHRC-fundedFootnote1 research study on game design that was part of a larger study called Maker Literacies. The research involved a year 10 classroom in the Niagara region, Canada. Working with two secondary teachers at the school in a Civics and Career class, we had hoped that students would design a videogame based on the concept of future careers and work trajectories, but we soon realised that our project idea was far too ambitious, so we adjusted the assignment to designing board games. The research study took place over 6 weeks and moved from planning in consultation with video game designers to designing, prototyping, testing and then to final designs and a marketing plan. Jennifer and Amélie Lemieux conducted the research with digital humanities scholar Jason Hawreliak who spent the first two weeks of the research explaining the central tenets of game design and moved from story development to different game genres to gaming practices. Then, three video game designers visited the class twice to share their perspectives and expertise across a wide range of videogames. The designers’ lived perspectives brought to life not only the process of game design, but also ways that we design games for, in their words, how they make you feel and the stories that they tell (Ehret and Hollett Citation2013; Ehret, Hollett, and Jocius Citation2016). During their second visit to the class, students played board games against game designers enacting gaming practices and experiencing the feeling of playing the game. Although there were longer discussions about video game design, their experiences and anecdotes largely focused on designing and marketing board games. Everyone involved trialled different types of board games such as Clue, Battleship, Risk, Monopoly, and Ticket to Ride to have a deeper understanding of the logic, pace, goals, and game’s design. Playing board games together gave us a window into the materialities and affective intensities of games and having game designers with us gave us a behind-the-scenes perspective on what designing different games involved (though they were not involved in the actual design of the games). Through gameplay, researchers, teachers, and students engaged with a board game’s underpinning ideas, beliefs, tensions, and narratives and many students shared their personal reflections such as one student who noted gender stereotypes in Clue. For example, she noticed females in Clue are characterised by their looks, clothing styles and physique whereas men are characterised in terms of their intelligence, successes, and wealth.

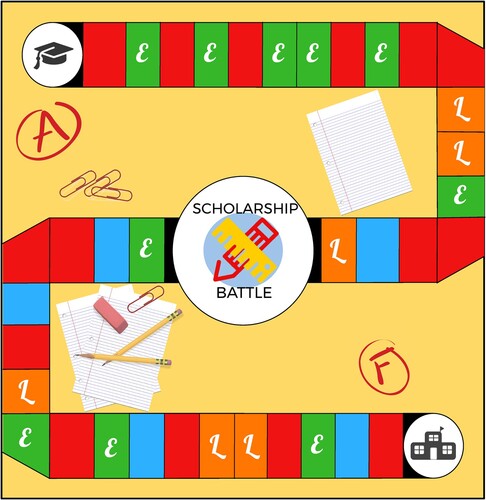

For this analytic case, Jennifer focuses on the design of a game called Scholarship Battle developed by a group of four students. Scholarship Battle is a game for 3–5 players who move into a school-like setting with three players and a narrator. The game mimics and simulates the anxiety and stress that come with the end of high school and applying for college and university scholarships. Each player moves her or his way toward earning a scholarship and the game’s narrative has an omniscient role giving out directions and deciding who gets stress cards. Scholarship Battle begins by randomly selecting a character card. and show the board design and the playing cards.

Figure 3. Scholarship Battle playing cards.

Group members who designed Scholarship Battle were open about their own aspirations to go to college for a trade or profession or to study a discipline at university or college and they all talked about needing a scholarship in order to attend post-secondary education. Jennifer spent the most time with this group and listened as they talked through their ideas, fears, and beliefs. The group was particularly animated and detailed about entangled stories that they wanted to incorporate into the game’s content and design. Their descriptions and debates about story lines were wide-ranging from their favourite game to media that absorbs their attention to their own personal experiences and thoughts. Each group member shared specific scenarios that they could apply to a Life or Event card (see for game cards). Two group members talked about a need to disrupt white, middle to upper class depictions of what futures should be and/or look like. They discussed how their own families struggled financially and the steep road they had to climb to secure a scholarship and attend university. Their own backgrounds and stories found their way into designs and their stories materialised in game card character cards as well as ‘Life’ and ‘Event’ cards. The Life and Event cards are particularly pertinent to the storytelling practice of identity-laden entangled stories because what Jennifer realised sharing and listening to group members is that their own experiences became a life or event card. An event such as sleeping in and being late for work which led to losing a job which limited possibilities (an actual Event card in the game) was a stated fear by one of the group members. Also, there were relational entangled storying practices that group members shared and they agreed about such as anxiety over getting entrance into a particular university. Jennifer remembers two group members debating/arguing about design choices and storying practices such as what should be featured in the marketing pitch and stories shared on Life cards. What was interesting to Jason, Amélie, and Jennifer was the level of attention paid to design choices such as colour palettes and geometric shapes on the board seen in and . In terms of intramodal and transmodal storytelling choices, the group agreed on bold reds, oranges, blues, and greens and the design combined a Monopoly meets Candyland board game feel to its look.

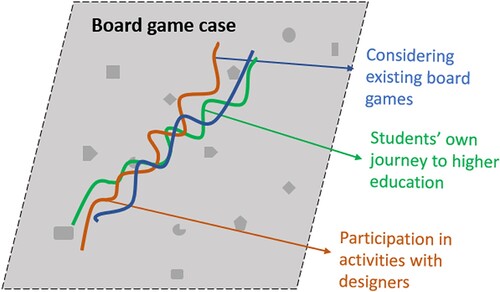

Ingold’s theorising is helpful here to explain and extrapolate the nature of Scholarship Battle and to interpret the practices of game play as players navigated across the game board. After discussing and debating the design, the four group members wanted a dynamic board that combined the stressful game practices of Monopoly (e.g., buying real estate and building properties and thereby wealth) with the movements, design properties, and game trajectories of Candyland or Snakes and Ladders like moving up and down the game board with the roll of a die. Quite deliberately, Scholarship Battle induces anxiety and stress as part of the game play. The practice of playing Scholarship Battle therefore demands navigating through stresses and milestones to win your scholarship. Returning to Ingold’s words, the game invites a story world of movement and becoming that invites not only crossing of story lines, but also affective intensities that accompany these lines (see below).

Figure 4. Entangled lines within board game design.

As illustrates, the board game invites personal, identity-laden storying practice (#1 building/scaffolding existing stories) by showing how four group members gradually relate to each other through planning, debating, storyboarding, and designing from an idea to a designed game to a marketing and sales pitch. The creation of Scholarship Battle also demonstrates the second storying practice of relational entangled stories by merging and weaving together each group members’ hoped-for future trajectory for education and training. As well, there is evidence of the third storying practice of intramodal/transmodal entangled stories by building on other board games and building their designs, aesthetics, rules, and practices into the final design. Such an orientation to game play adds an important level of sophistication and creative flair to the design work that young people engage in that is alive and well in the next two analytic cases.

Analytic case #2: aesthetic taskscapes with environmental storylines within relational entangled eco-designs

The second analytic case emerges from a small research project supported by a regional funding scheme in the Norwegian research council emphasising research based innovation and partnerships between ed-tech businesses and researchers.Footnote2 For this particular project, Hans Christian and two colleagues from his department, together with a small ed-tech start up firm, received funding for doing a small case study where the aim was to test a particular digital 3D-design program called Ludenso Create in an upper secondary school in Oslo. Ludenso Create is a digital tool where you can design various three-dimensional shapes and combine them into larger structures such as houses and environments. It is also possible to add different types of surfaces and textures to the designed environments. The school was located in the eastern part of the city, and comprised a very multicultural student population. The school had a history of antisocial behaviour, but we also experienced that the school took these problems very seriously and tried to create a safe and engaging learning environment for students. The class we observed had a diverse socioeconomic background. We found that the science teacher we worked with was very open to experimenting with pedagogy and technology in her science class. It is our experience, and it is also emphasised in our national curriculum, that students should actively engage in inquiry and exploration in science education. Thus, there is a tradition for pursuing more constructivist pedagogies where design oriented tasks are blended with doing science inquiry.

We did a small intervention together with one science teacher lasting for about 3–4 hours with one class of students, and we videotaped two dyads working together to solve their task. The teacher was a recently graduated young woman with an engineering background. In this analytic case, we focus on particularly interesting features and episodes in the design activity of one of these dyads consisting of Elina and Sara, two 15 year old girls using the 3D-design program to design a model of a sustainable house. Since we did not spend that much time with the students in the classroom, we did not really get to know the girls that are the focus for this analysis. We do not know much about their background or whether they were particularly interested in design. From observing the girls doing their task and from examining the videorecords, we did however notice that they clearly expressed an interest in making something beautiful and not just functional. This emerged as an important concern for them in their activities.

The design software provided students with the opportunity to use and combine three-dimensional geometrical figures into more elaborate and comprehensive designs. They could also add different types of surfaces with different characteristics onto their designs, such as solar panels and brick walls. The taskscape was a rather open design task where multiple narrative lines could emerge aligning with or disrupting the storied knowing made relevant by the task. The design program offered many possibilities for narration and students had a lot of freedom in deciding on what kind of house they wanted to design. What we are particularly interested in showing here concerns how the emerging narrative that provided the design with some form of coherence and meaning involves complex human/material/digital entanglements, and that a narrative line emerges in and through this entanglement between the discursive and the material.

Overall, when Sara and Elina talk about the house they are making, they primarily focus on what the house should look like, and not so much about the functionality in terms of its energy efficiency. They do however include energy efficient features into their design such as solar panels and hydroelectric power turbines, but their main concern is about the architectural qualities of the house. From our observations, we could see how Sara and Elina’s design was very different from the other groups, who designed more traditional physical structures. They were also very concerned about how the house fitted with the natural environment and how they merged into one another, that is to say, how features of the environment such as a stream or grass naturally flowed into and through the house blurring the boundaries between the natural and the designed world. Instead of systematically orienting themselves to their task, they immediately started to tell stories about what the house should look like, and while they were coming up with design stories they started to design their environment and utilise the opportunities afforded by the design program. To paraphrase they talked about how they wanted a river flowing through the digital space and that the river should run through the house and that they should use hydroelectric turbines to generate electricity.

The following short extract illustrates in more detail the dynamics between the features of the program, its functionality, and the girls’ actions with and around the program. The tensions and opportunities happening along multiple intersecting lines, creates an emerging innovative design story. Here we want to emphasise how creative designs may occur rather accidentally because of tensions between students’ abilities, the functionality of the design program, and students’ ability to change the narrative. The students made a very aesthetically advanced design with a clear functionalist design language (see below). They designed a cubic design placed on poles and where there is a river running underneath the house, the river which through a small power plant provides electricity.

Figure 5. Picture of Elina and Sara’s architectural design.

The immediate context for the extract is that the students have been working with designing a window into the floor, so that the inhabitants can look at the stream running below the house. They are not entirely familiar with using 3D objects so instead of making a 3D window, which would be the ‘correct’ thing to do, they draw a rectangular flat shape on the floor instead. When they find it difficult to make it into a window, they try to erase it, but end up making it into something else. The text in bold and square brackets are observations made by the researchers.

Extract 1:

I want grass over there, i am not quite sure exactly where

Wait, try,

Maybe there is, yes there are solar panels on the whole roof

It is because it is red, pink I mean

yes but it is because [they realize that they cannot cover the whole roof with solar panels]

I am trying that stupid shape over there [a shape that has been accidentally copied from somewhere else]

No but wait, we cover that with solar panels and then we make a smaller square of grass right next to it, (…)

That is very nice

Are they solar panels

No it is grass

A particularly interesting feature of this extract concerns how the design emerges through the entanglements of their actions and features of the design program. It is precisely because of their lack of mastery of the program and the tensions that occur in their intra-action that the creative design emerges. Instead of trying to make their designs right, they recreate what we might call an entangled story and new ideas and innovative solutions emerge. We might claim that the features of the design become material/digital anchors for emerging creative storied designs (Skåland, Arnseth, and Pierroux Citation2020). With the language of Ingold (Citation2011), we see how creative designs emerge through threads becoming meshed together, in that the model of the house and their talk together become entangled into storied matter – a digital model with a temporary existence.

Instead of designing a sustainable house in a more ‘engineering’ type of fashion, Elina and Sara acted more like architects creating an aesthetically advanced model of a house. Their design emerged as an entangled story through intra-actions between materials, and human actions. Their design ideas did not precede their actual 3D-design, but their design idea – the storied digital matter of a temporarily stabilized representation of a house – emerged through the intra-action of their talk, design actions and the virtual model. The emerging design and features of the software participated in creating their story about what the house became. This is in contrast to much design thinking research who sees models of the design process as going from problem definitions, to developing design ideas, to developing concepts that represent a solution to the problem (Tassoul Citation2009).

As we mentioned previously, according to Ingold humans do not live in discrete spaces, but rather live along lines and experience and meaning is always emerging and changing. We see this clearly also in this example how their design continues along a path of interested making and creating. The girls’ interest in design contributes to their emerging and creative storytelling. The case is methodologically important in that the material-discursive entanglement produces creative design practices. Boundaries between school and everyday life (interests and skills) are therefore fluid and intertwined.

The analytic example makes visible how storytelling emerges through the intra-action of human and non-human materialities, in the sense that the story draws together the elements into storied knowledge (Ingold Citation2011). In studies of creative making and design work, it is crucial to study in some detail how students solve ill-defined and open design challenges, and how their designs become materialised entering into dialogue with their thinking and design processes. Through analysis that pays close attention to mattering, we can see how the material/digital became entangled with the students’ talk and action in emerging creative design processes.

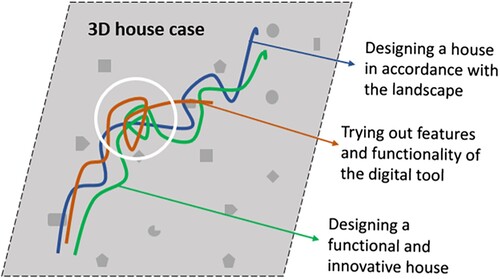

Students are continuously negotiating what can be done with shapes made available in the 3D design program, creating designs that work as anchors or conversational partners that respond and invite further reflection and action. Designs and design mistakes open up new pathways for new designs. The creative design emerges through entangled stories involving material and semiotic features of the computer program and the students’ talk and action. It is not primarily the tool or the materials that carry the story, even though the story so to speak becomes materialised. Still, it is primarily the students that create entangled stories. This also represents an interesting conceptualization of how design thinking develops ().

Figure 6. Interweaving storylines in 3D-design case.

Revisiting the typology of entangled stories introduced above, it is particularly relational entangled stories and identity-laden stories as conceptualizations of young people's digital practices that are particularly relevant in this particular case. These concepts make visible and help us understand important features of their design work, for instance how the two girls storied design choices, that is to say, how they talk about and make design choices and through that process merge the designed natural environment and the architecture. Their design choices become entangled with their emerging designs framed within an open taskscape that allows for multiple and intertwining lines of activity. Furthermore, their work is also characterised by identity laden entangled stories. Their emerging interests in making something interesting and beautiful become lines in the story that connect their emerging design to their pasts, present and future.

Analytical case #3: schooling, digital resources, and literary narrative storylines – relational boundaries and storied practices in the production of memes

The third case comes from an ethnographic study funded by the Chilean research councilFootnote3 examining the use and negotiation of teenagers’ digital practices in two segundo medio classes (15–16 years old) in Chile (Ruiz Cabello Citation2019). This analytical case focuses on a language school project called ‘the meme project’ undertaken in one of the classes and draws on informal conversations, reflective field notes, observations of final submissions, and interviews with students and class teacher.

Students worked in groups out of school hours for several weeks to create a Facebook profile of one of the protagonists of the novel ‘Of love and shadows’ by Isabel Allende. In the profile, each group had to create and post eight memes that represented key events the chosen protagonist went through, showing an understanding of the novel's plot and the character's story. ‘We had to create an account, post the memes but … adding a statement, you know, by the book protagonist (…) like a post … . as if the protagonist was talking about him/herself’ (student interview). Each group had room to decide how to design the account and produce the memes. This analytical case focuses on one of the groups’ work.

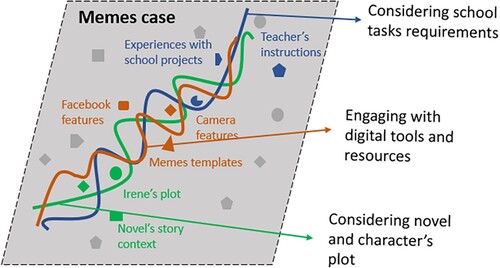

Drawing on Ingold’s concepts of lines and storied knowledge, we examine the meme production’s taskscape and the entanglements of the students’ actions and material entities. By doing so, we show how immaterial-material storylines of school instructions and expectations, engagement with digital tools and resources, and the storied practice based on the novel weave their way to composing a multimodal output (). In this process, skills, interests, tool-based decisions, expectations, and affect (dis)entangle these storylines in remixing, relational, and fractal ways, creating transitory and relational boundaries – as opportunities and limitations – for students to create the memes.

Figure 7. Interweaving storylines in the meme project case.

The group members were Mario, Tito, Cristian, and Manuela. They chose to create the memes based on the protagonist Irene Beltran () from scratch, producing and taking pictures inspired by existing memes, such as ‘success kid’ and ‘bad luck Brian’. This group's strategy differed from that of the other groups within the class, who chose to download existing memes and modify the original text on them. In the process of creating the memes, group members would remix Allende’s character with their own interpretation, their own aesthetic decisions of the pictures, and material possibilities into the clothing chosen and lighting available, for example. The selection of memes, which would serve as the basis for the composition of the pictures and then their own created memes, translated into a fractal product that combined linguistic and visual materialisation of the novel.

Figure 8. Group Facebook Account for the Protagonist Irene Beltran. Source: screenshot retrieved in 2022 through link provided in informal conversation during fieldwork. First photo: novel's author Isabel Allende second photo: character from a Chilean TV series called ‘Los 80s’ (the 80's).

Cristian and Tito mentioned various times throughout fieldwork – as many other classmates – that school projects were generally dull, not like this one. Mario, who refers to himself as a ‘youtuber’, expressed this project was an opportunity to produce something more elaborate, and Cristian and Tito expressed being excited about this. Finally, Manuela and Cristian were comfortable with taking pictures for the memes, and Manuela posing as Irene. Early on, each of the group members had clarity about how they would organise the work, the materials needed, and when they would meet. However, by weaving through storied practices of the novel, the materiality of digital tools and resources, and the teacher’s requirements, it was not predictable how the process would unfold, as examined below. It would be through the relationality of storylines in the project taskscape (Ingold Citation2011) that is possible to explore this emerging process.

How they worked together could be described as lines moving, intersecting and weaving in (Ingold Citation2011). In one interview, Mario explained that most of the group’s work and discussion about what to do and how to recreate Irene's story took place on WhatsApp. He showed Paulina some of the WhatsApp dialogues involving the other group members around their decision-making process. Various texts referred to how the team members felt about Irene's story, what she should or should not have done, and how some thought her story could have gone differently. They briefly discussed the possibility of changing her story slightly for fun and because Cristian figured it would be more coherent. However, the rest kept reminding each other of the teacher's instructions and project requirements. These instructions and requirements could be interpreted as lines used to settle disagreements.

During one participant observation in break time, Tito and Mario described how the photo session went. They spent a great deal of time discussing how Irene would dress for the photo of the only meme that included her. In their deliberations, they considered that the novel was set in the seventies, that Irene was described in the novel as somebody who did not care about her appearance, and that Manuela was not doing the face right based on the meme that was the inspiration for this shoot (‘success kid’). ‘It didn't matter!’, said Tito emphatically to make the point that nobody would pay attention to those details, and the teacher probably did not know about the memes anyway. Mario was moving his head, showing disagreement.

Cristian was taking the pictures and he mentioned the light was ‘horrible’ that day, and he wished to have a ‘proper’ camera, not the one on his phone. It took him and the rest a while to be satisfied with where to take the pictures. Tito and Cristian agreed that Mario was taking things too seriously, and they were all exhausted when they came to shoot Manuela as Irene. Tito said that they had had fun, but in the end, he thought the teacher would not give special consideration to the fact they took their own pictures. Mario added that using Facebook was not very exciting as it was not the platform they were using the most at that time (Snapchat and YouTube for them) and it was not interesting to create an account that was not meant to be shared with their classmates nor used as a ‘real’ account.

This analytical case can be seen as a window to entangled and relational storied practices emerging in the taskscape of producing the memes, which included material and immaterial entities such as the novel, teacher’s instructions, the textures and look of the clothing, the Facebook account, the light and affordances of the phone camera, their interpretations, and feelings towards the whole project. The diverse entities were pondered differently in remixing, fractal and relational ways the project to create photos and memes, or in other words, weaved in and through differently at varying stages of the design process. For example, the clothing was not an issue until the students had to take a picture of Manuela as Irene; the light and the camera were a problem for those memes taken indoors; and decisions were constantly contrasted against the teachers’ instructions, and their self-defined requirements, such as the group's decision to use real memes and the original memes used as inspiration for the photos.

The weaving of lines also shows up in that the Facebook account, as a required feature, did not appear in this process as intended by the teacher. The teacher expressed in an interview his expectation that this project will allow students to use social media in a familiar way for them, which was not the case. Moreover, the students’ affects on the project changed along the way: from initially being excited about this project and thinking of ideas to make it fun to then expressing in the end that the outcome was more important than the process. Moreover, this perception does not only relate to this project but can be traced back to their previous experiences and involvement in past projects. In this way, the different lines, as entities involved in the process, cannot be clearly classified in one way throughout the project, such as curricular and everyday knowledge or interests. Even the teacher's instructions became possibilities to think beyond what was required at the beginning, later becoming a background for students’ decisions and ending up being mainly a checklist to comply with.

These constant movements within storied practices point out to what Ingold calls the ‘generative potential of the lines’ (Ingold Citation2007, 198; plural added). Students in this case, created the memes not as separate actors from the entities described above but along them and as part of in-movement and woven practices. In the intra-action (Barad Citation2007) of human and non-human entities, either as obstacles or possibilities, their entanglements allow moving towards the production of memes as storied knowledge. Thus, the notion of entangled storied lines contributes with a focus on the lines that become meshed in the creative process in diverse and entangled ways and how their role does not pertain to stable categories within emerging human/non-human entanglements.

Finally, we would like to argue for the need for further examination of how different lines are woven and entangled differently in school-initiated students’ multimodal production. In this case, the teacher's instructions, in Ingoldian terms, provide the key task around how the meme taskscape is organised, which – in this sense – becomes a generative line. However, it can also be seen as a restrictive line, a thicker or more tightly tied line in the story of producing the memes than others. These issues speak of stabilisation of how things are done in classes and its role in multimodal production in school-based projects. Posthuman approaches may be limited in capturing stabilisation, as suggested in the previous case. Nonetheless, they can allow us to explore how different lines entangle and relate to others in ongoing and emergent production or design stories, potentially showing some patterns. In this sense, these approaches can allow us to rethink how multimodal composition and design can be reframed in schools. They have allowed us to explore in more detail how these processes turn into storied matter, how students live it as storied knowledge, and what lines and meshes emerge.

Concluding entangled thoughts

Ingold helped us think through the possibilities of unsettling boundaries around stories to reveal and indeed celebrate different repertoires for building and designing multimodal compositions. These sorts of repertoires are often hidden, rendered opaque and need more foregrounding in formal learning and the ways that we teach and frame modern composition. Boundaries between self and the world need collapsing so that we find ways to get closer to the potential of a ‘mind immanent in the living currents of world formation, which derives its creativity from the very same source’ (Ingold Citation2022, 4). If we hope to explore ways of nurturing this creative potential, it feels important to think for a moment about what the properties of a situation are.

To even begin to devise policy and curricula that speaks to the seismically different kinds of compositional practices that people – young and old – engage in, research must get so much closer into the logic, orchestrations, actions, and planning that goes into multimodal compositions. Considering the underside of composition as in the backstory and lead up to actual design and composition is as important as considering the final product and its substantive and aesthetic shape. We argue in this paper for greater sensitivity to the stories that get hidden or less visible in compositions and the ways that they change and entangle with others. Multimodal compositions are a canvas populated by different voices, histories, and yes stories that require respect and reclaiming so that the sophisticated and often complicated work of designers and composers can have greater prominence in schools. We appreciate in writing this paper together that we too are entangled within the overall story of it which started back a few years ago when Jennifer and Hans Christian met with a children’s media producer about the properties and processes of media production. Therefore, we are as enmeshed and entangled in the narrative as well and as well as the forces of academia.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) through the Insight program (grant number 435-2017-0097).

2 This research was funded by the National Research Council under the FORREGION program (grant number ES654077).

3 This research was funded by the National Agency of Research and Development (ANID for its acronym in Spanish), grant number 72140125, Becas Chile programme.

References

- Bailey, C. 2021. Researching Virtual Play Experiences: Visual Methods in Education Research. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Barton, D., and M. Hamilton. 1998. Local Literacies: Reading and Writing in Onecommunity. London: Routledge.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Ehret, C., and T. Hollett. 2013. “(Re) Placing School: Middle School Students’ Countermobilities While Composing with IPods.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 57 (2): 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.224.

- Ehret, C., T. Hollett, and R. Jocius. 2016. “The Matter of New Media Making: An Intra-Action Analysis of Adolescents Making a Digital Book Trailer.” Journal of Literacy Research 48 (3): 346–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X16665323.

- Hackett, A. 2016. “Young Children as Wayfarers: Learning About Place by Moving Through It.” Children & Society 30 (3): 169–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12130.

- Haraway, D. 1985. A Cyborg Manifesto. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hillman, T., A. Weilenmann, B. Jungselius, and T. L. Lindell. 2016. “Traces of Engagement: Narrative-Making Practices with Smartphones on a Museum Field Trip.” Learning, Media and Technology 41 (2): 351–370. http://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064443.

- Ingold, T. 2007. “Materials Against Materiality.” Archaeological Dialogues 14 (1): 1–16. http://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203807002127.

- Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2015. The Life of Lines. London, UK: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2017. Forms of Dwelling: 20 Years of Taskscapes in Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Ingold, T. 2022. Imagining for Real: Essays on Creation, Attention and Correspondence. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Rowsell, J. 2021. “Storied Matter: Research on Young People’s Felt, Sensed and Storied Designs.” In Visual and Cultural Identity Constructs of Global Youth and Young Adults: Situated, Embodied and Performed Ways of Being, Engaging and Belonging, edited by F. Blaikie, 158–177. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

- Rowsell, J. in press. The Comfort of Screens: Literacy in Post-Digital Times. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rowsell, J., A. Lemieux, L. Swartz, M. Turcotte, and J. Burkitt. 2018. “The Stuff That Heroes Are Made Of: Elastic, Sticky, Messy Literacies in Children’s.” Transmedial Cultures”. Language Arts 96 (1): 7–20.

- Ruiz Cabello, P. A. 2019. “I'd Die Without It”: A Study of Chilean Teenagers' Mobile Phone Use in School [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Bristol.

- Skåland, G., H. C. Arnseth, and P. Pierroux. 2020. “Doing Inventing in the Library. Analyzing the Narrative Framing of Making in a Public Library Context.” Education Sciences 10 (6): 158. http://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10060158.

- Tassoul, M. 2009. Creative Facilitation. Delft University of Technology Press: Delft.